User login

Managing menopause symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

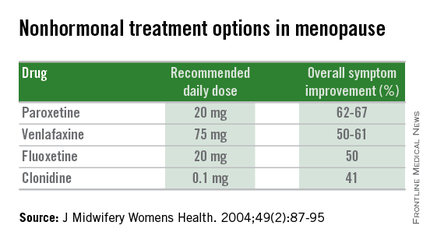

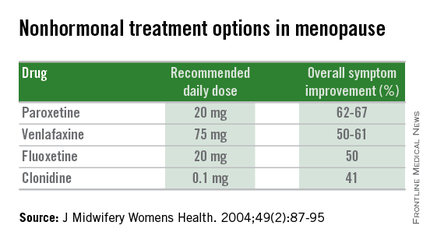

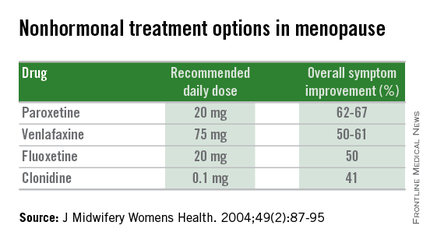

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Naloxone to revive an addict

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are in the midst of an epidemic of heroin and prescription opioid abuse. While the two do not completely explain each other, they are tragically and irrevocably linked.

From 2001 to 2013, we have observed a threefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from opioid pain relievers (about 16,000 in 2013) and a fivefold increase in the total number of overdose deaths from heroin (about 8,000 in 2013).

Heroin initiation is almost 20 times higher among individuals reporting nonmedical prescription pain reliever use. Among opioid-treatment seekers, the majority of individuals who initiated opioid use in the 1960s were first exposed to heroin. This is in contrast to those who initiated in the 2000s, among whom the majority were exposed to prescription opioids. For young adults, the main sources of opioids are family, friends … and clinicians.

Opioids are powerfully addictive and can be snorted, swallowed, smoked, or shot. Data from the START (Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies) trial suggest that individuals who inject opioids are less likely to remain in treatment than noninjectors. This necessarily increases the risk for injectors to inject again and be at risk for overdose.

Opioid overdose can be reversed with the use of naloxone. But naloxone has to be immediately or quickly available for it to be effective. Take-home naloxone programs are located in 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1996, home naloxone programs have reported more than 26,000 drug overdose reversals with naloxone.

On Nov. 18, the Food and Drug Administration announced the approval of a naloxone nasal spray. Prior to this approval, naloxone was only available in the injectable form (syringe or auto-injector), and needle management likely posed a barrier to first responders. The nasal spray can be administered easily without medical training. Naloxone nasal spray administered in one nostril delivered approximately the same levels or higher of naloxone as a single dose of an FDA-approved naloxone intramuscular injection in approximately the same time frame.

It is one thing to save a heroin addict who has just overdosed with nasal naloxone followed by appropriate medical attention. It is entirely another to engage them in an effective drug treatment program.

If naloxone revives them, it is treatment that can save them.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

Polymyxin resistance is bad news

The finding of British and Chinese colleagues of a new plasmid-borne resistance, MCR-1, encoding for resistance to colistin/polymyxin in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is, as many have pointed out, very bad news (Lancet Infec Dis. 2015 Nov 18. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00424-7).

The fact that it may have infiltrated large areas of East and Southeast Asia forebodes an era where no antibiotic will be available to treat some of our patients. It is not the end of mankind, and it will not bring us back to the Middle Ages, after all we managed to rather successfully experience the end of the Second World War without having experienced extinction as a species.

BUT, here is the crunch of the matter – we have since then developed what is today ‘modern medicine’ and modern medicine as we know it with successful treatment of malignant blood disorders, cancer, transplantations, intensive care, neonatal care, and foreign body surgery is very much dependent on managing to prevent and treat complications in the form of infections. If panresistance becomes common we may have to reevaluate our strategies when dealing with these disorders and procedures.

What did we do to deserve this? We have behaved the way we behave with most natural resources available to us. We have abused antibiotics since we discovered them, and we continue to squander them for economical gain in areas where antibiotics have no place at all. We look for evidence that using 600 tons of antibiotics to successfully rear pigs is not harmful instead of saying ‘why take the risk?’

In the latest case, that of the new gene MCR-1 encoding resistance to colistin/polymyxin, it is now believed that the frequent use of colistin in animal husbandry in China and other East Asian countries may be behind the catastrophe.

Evolution is a harsh but fair task master. We deserve everything we get. But again we have squandered the resources of our children and grandchildren.

Dr. Gunnar Kahlmeter is communications officer at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and practices in the department of clinical microbiology at Central Hospital in Växjö, Sweden.

The finding of British and Chinese colleagues of a new plasmid-borne resistance, MCR-1, encoding for resistance to colistin/polymyxin in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is, as many have pointed out, very bad news (Lancet Infec Dis. 2015 Nov 18. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00424-7).

The fact that it may have infiltrated large areas of East and Southeast Asia forebodes an era where no antibiotic will be available to treat some of our patients. It is not the end of mankind, and it will not bring us back to the Middle Ages, after all we managed to rather successfully experience the end of the Second World War without having experienced extinction as a species.

BUT, here is the crunch of the matter – we have since then developed what is today ‘modern medicine’ and modern medicine as we know it with successful treatment of malignant blood disorders, cancer, transplantations, intensive care, neonatal care, and foreign body surgery is very much dependent on managing to prevent and treat complications in the form of infections. If panresistance becomes common we may have to reevaluate our strategies when dealing with these disorders and procedures.

What did we do to deserve this? We have behaved the way we behave with most natural resources available to us. We have abused antibiotics since we discovered them, and we continue to squander them for economical gain in areas where antibiotics have no place at all. We look for evidence that using 600 tons of antibiotics to successfully rear pigs is not harmful instead of saying ‘why take the risk?’

In the latest case, that of the new gene MCR-1 encoding resistance to colistin/polymyxin, it is now believed that the frequent use of colistin in animal husbandry in China and other East Asian countries may be behind the catastrophe.

Evolution is a harsh but fair task master. We deserve everything we get. But again we have squandered the resources of our children and grandchildren.

Dr. Gunnar Kahlmeter is communications officer at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and practices in the department of clinical microbiology at Central Hospital in Växjö, Sweden.

The finding of British and Chinese colleagues of a new plasmid-borne resistance, MCR-1, encoding for resistance to colistin/polymyxin in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is, as many have pointed out, very bad news (Lancet Infec Dis. 2015 Nov 18. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00424-7).

The fact that it may have infiltrated large areas of East and Southeast Asia forebodes an era where no antibiotic will be available to treat some of our patients. It is not the end of mankind, and it will not bring us back to the Middle Ages, after all we managed to rather successfully experience the end of the Second World War without having experienced extinction as a species.

BUT, here is the crunch of the matter – we have since then developed what is today ‘modern medicine’ and modern medicine as we know it with successful treatment of malignant blood disorders, cancer, transplantations, intensive care, neonatal care, and foreign body surgery is very much dependent on managing to prevent and treat complications in the form of infections. If panresistance becomes common we may have to reevaluate our strategies when dealing with these disorders and procedures.

What did we do to deserve this? We have behaved the way we behave with most natural resources available to us. We have abused antibiotics since we discovered them, and we continue to squander them for economical gain in areas where antibiotics have no place at all. We look for evidence that using 600 tons of antibiotics to successfully rear pigs is not harmful instead of saying ‘why take the risk?’

In the latest case, that of the new gene MCR-1 encoding resistance to colistin/polymyxin, it is now believed that the frequent use of colistin in animal husbandry in China and other East Asian countries may be behind the catastrophe.

Evolution is a harsh but fair task master. We deserve everything we get. But again we have squandered the resources of our children and grandchildren.

Dr. Gunnar Kahlmeter is communications officer at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and practices in the department of clinical microbiology at Central Hospital in Växjö, Sweden.

Relationship-Based Care: A novel approach for patients and providers

When I think of the word “relationship,” I imagine gazing into the loving eyes of my husband, playing hide and seek with my children, or texting my best friend for no good reason other than to just say hello.

There is a special comfort zone we expect from people who are close to us; a feeling of love and acceptance that we can’t find elsewhere.

But in a much broader sense, our important relationships extend far beyond our inner circle to include every single person who is involved with our health care team. Our team includes the hospital executives who create new safety initiatives, develop budgets, and oversee a host of other patient care and fiscal functions. The physical therapists who evaluate our patients and make recommendations on how to safely transition them out of the hospital are on our team. The housekeepers who scrub the toilets and wash the linens to prevent nosocomial infections are on our team. They, along with many others, play a pivotal role in our patients’ care, although many important players make their impact behind the scenes.

Yet, of course, our most important professional relationships are not with the CEO, the pharmacist, or even the nursing staff. Our most important relationships are with our patients and their families. I recently attended an all-day conference on a little-known gem called Relationship-Based Care (RBC), a culture transformation and operational model that is gaining steam globally. The RBC model focuses not only on well-known metrics, such as patient safety, quality care, and patient satisfaction; it also emphasizes staff satisfaction by improving each and every relationship. Specifically, it creates therapeutic relationships between caregivers and the patients and families they serve, strengthens relationships between members of the health care team, and last, but certainly not least, it nurtures each caregiver’s relationship with himself or herself. What a novel, and much needed concept!

Numerous hospitals that have implemented this training model have achieved impressive outcomes, including significant improvement in HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, and staff satisfaction survey scores so high that one hospital gained national recognition as one of the best places to work in America.

I look forward to future training on RBC and am glad to see that addressing the needs of caregivers, not just care receivers, is starting to take center stage, as it rightfully should. After all, how can we give our all to our patients when we are not whole?

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

When I think of the word “relationship,” I imagine gazing into the loving eyes of my husband, playing hide and seek with my children, or texting my best friend for no good reason other than to just say hello.

There is a special comfort zone we expect from people who are close to us; a feeling of love and acceptance that we can’t find elsewhere.

But in a much broader sense, our important relationships extend far beyond our inner circle to include every single person who is involved with our health care team. Our team includes the hospital executives who create new safety initiatives, develop budgets, and oversee a host of other patient care and fiscal functions. The physical therapists who evaluate our patients and make recommendations on how to safely transition them out of the hospital are on our team. The housekeepers who scrub the toilets and wash the linens to prevent nosocomial infections are on our team. They, along with many others, play a pivotal role in our patients’ care, although many important players make their impact behind the scenes.

Yet, of course, our most important professional relationships are not with the CEO, the pharmacist, or even the nursing staff. Our most important relationships are with our patients and their families. I recently attended an all-day conference on a little-known gem called Relationship-Based Care (RBC), a culture transformation and operational model that is gaining steam globally. The RBC model focuses not only on well-known metrics, such as patient safety, quality care, and patient satisfaction; it also emphasizes staff satisfaction by improving each and every relationship. Specifically, it creates therapeutic relationships between caregivers and the patients and families they serve, strengthens relationships between members of the health care team, and last, but certainly not least, it nurtures each caregiver’s relationship with himself or herself. What a novel, and much needed concept!

Numerous hospitals that have implemented this training model have achieved impressive outcomes, including significant improvement in HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, and staff satisfaction survey scores so high that one hospital gained national recognition as one of the best places to work in America.

I look forward to future training on RBC and am glad to see that addressing the needs of caregivers, not just care receivers, is starting to take center stage, as it rightfully should. After all, how can we give our all to our patients when we are not whole?

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

When I think of the word “relationship,” I imagine gazing into the loving eyes of my husband, playing hide and seek with my children, or texting my best friend for no good reason other than to just say hello.

There is a special comfort zone we expect from people who are close to us; a feeling of love and acceptance that we can’t find elsewhere.

But in a much broader sense, our important relationships extend far beyond our inner circle to include every single person who is involved with our health care team. Our team includes the hospital executives who create new safety initiatives, develop budgets, and oversee a host of other patient care and fiscal functions. The physical therapists who evaluate our patients and make recommendations on how to safely transition them out of the hospital are on our team. The housekeepers who scrub the toilets and wash the linens to prevent nosocomial infections are on our team. They, along with many others, play a pivotal role in our patients’ care, although many important players make their impact behind the scenes.

Yet, of course, our most important professional relationships are not with the CEO, the pharmacist, or even the nursing staff. Our most important relationships are with our patients and their families. I recently attended an all-day conference on a little-known gem called Relationship-Based Care (RBC), a culture transformation and operational model that is gaining steam globally. The RBC model focuses not only on well-known metrics, such as patient safety, quality care, and patient satisfaction; it also emphasizes staff satisfaction by improving each and every relationship. Specifically, it creates therapeutic relationships between caregivers and the patients and families they serve, strengthens relationships between members of the health care team, and last, but certainly not least, it nurtures each caregiver’s relationship with himself or herself. What a novel, and much needed concept!

Numerous hospitals that have implemented this training model have achieved impressive outcomes, including significant improvement in HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) scores, and staff satisfaction survey scores so high that one hospital gained national recognition as one of the best places to work in America.

I look forward to future training on RBC and am glad to see that addressing the needs of caregivers, not just care receivers, is starting to take center stage, as it rightfully should. After all, how can we give our all to our patients when we are not whole?

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist at Baltimore-Washington Medical Center in Glen Burnie, Md. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS. Reach her at [email protected].

An open letter to the FDA regarding the use of morcellation procedures for women having surgery for presumed uterine fibroids

In November 2014, the FDA ruled that power morcellation was contraindicated in "the majority of women" having surgery for uterine fibroids due to the potential risk of spreading occult uterine sarcoma.1 Although problems with this ruling were immediately apparent, the passage of time has allowed for more clarity on the related medical issues.

Prevalence of leiomyosarcoma among women having surgery for presumed uterine fibroids

The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma among women with fibroids is critical for every patient. All medical procedures have potential risk and the patient's understanding of risk is the foundation of medical decision making.

The FDA estimated that for every 458 women having surgery for fibroids, one woman would be found to have an occult leiomyosarcoma (LMS). We challenge this calculation. To estimate this risk, the FDA searched medical databases using the terms “uterine cancer” AND “hysterectomy or myomectomy.” Because “uterine cancer” was required, studies where cancer was not found or discussed were not identified. Nine studies, all but one of which were retrospective, were analyzed including a non–peer-reviewed Letter to the Editor and an abstract from an unpublished study.2,3

Additionally, 3 leiomyosarcoma cases identified by the FDA do not meet current pathologic criteria for cancer and would now be classified as benign "atypical" leiomyomas. If atypical leiomyomas and non–peer-reviewed data are excluded, the FDA identified 8 cases of LMS among 12,402 women having surgery for presumed leiomyomas, a prevalence of 1 in 1,550 (0.064%).

Pritts and colleagues4 recently published a more rigorous meta-analysis of 133 studies and determined that the prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for presumed fibroids was 1 in 1,960, or 0.051%. All peer-reviewed reports in which surgery was performed for presumed fibroids were analyzed, including reports where cancer was not found. Inclusion criteria required that histopathology results be explicitly provided and available for interpretation. Among the 26 randomized controlled trials analyzed, 1,582 women had surgery for fibroids and none were found to have LMS.

Bojahr and colleagues5 recently published a large population-based prospective registry study and reported 2 occult LMS among 8,720 women having surgery for fibroids (0.023%).

In summary: The re-analyzed FDA dataset yields a prevalence of 1 in 1,550 (0.064%); the Pritts study reports a prevalence of 1 in 1,960 (0.051%), with the RCTs having a prevalence of 0; and the Bojahr study reports a prevalence of 2 of 8,720 (0.023%). We acknowledge that with rare events statistical analysis may be uncertain and confidence intervals may be wide. However, these numbers do not support the FDA's estimated prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for presumed fibroids and those at risk for morcellation of an LMS.

Prognosis for women with morcellated LMS

Women with LMS, removed intact without morcellation, have a poor prognosis. Based on SEER data, the 5-year survival of stage I and II LMS is only 61%.6 Whether morcellation influences the prognosis of women with LMS is not known, and the biology of this tumor has not been well studied. Distant metastases occur early in the disease process, primarily hematogenous dissemination. Four frequently quoted published studies examine survival following power morcellation. Surprisingly, virtually none of the women in these studies had power morcellation. Furthermore, the data presented in these reports are poorly analyzed and patient numbers are very small.

Park and colleagues7 reported only one of the 25 morcellated cases had laparoscopic surgery with power morcellation. Eighteen women had a laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with scalpel morcellation performed through the vagina, one had a vaginal hysterectomy with scalpel-morcellation, and 5 had mini-laparotomy with scalpel morcellation through small lower abdominal incisions. Seventeen of the 25 patients plotted in the published survival curve were referred to the hospital after initial diagnosis or the discovery of a recurrence at another institution. Since the number of nonreferred women with less aggressive disease or without recurrence is not known, it is not possible to determine differences in survival between patients with and without morcellation.

In a study by Perri and colleagues,8 none of the patients had power morcellation: 4 women had abdominal myomectomy; 4 had hysteroscopic myomectomy with tissue confined within the uterine cavity; 2 had laparoscopic hysterectomy with scalpel morcellation; 4 had supracervical abdominal hysterectomy with cut-through at the cervix; and 2 had abdominal hysterectomy with injury to the uterus with a sharp instrument.

When comparing the outcomes for women with morcellated and nonmorcellated LMS, Morice and colleagues9 found no difference in recurrence rates or overall and disease-free survival at 6 months.

In the only study to compare use of power with scalpel morcellation in women with LMS, Oduyebo and colleagues10 found no difference in outcomes for the 10 women with power morcellation and 5 with scalpel morcellation followed for a median of 27 months (range, 2–93 months). Notably, a life table analysis of the above studies showed no difference in survival between morcellation methods.11

Of note, laparoscopic-aided morcellation allows the surgeon to inspect the pelvic and abdominal cavities and irrigate and remove tissue fragments under visual control. In contrast, the surgeon cannot visually inspect the peritoneal cavity during vaginal or mini-laparotomy procedures. Morcellation within containment bags has recently been utilized in an attempt to avoid spread of tissue. This method has not yet been proven effective or safe, and there is concern that bags may make morcellation more cumbersome and less safe.

What the FDA restrictions mean for women

The FDA communication states, "the FDA is warning against the use of laparoscopic power morcellators in the majority of women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids."1 This statement is not consistent with current evidence.

Moreover, a severe restriction of morcellation, including vaginal and mini-laparotomy morcellation, would limit women with symptomatic leiomyomas to one option: total abdominal hysterectomy. For women with fibroids larger than a 10-week pregnancy size, which most often require either scalpel or power morcellation in order to remove tissue, a ban on morcellation would eliminate the following procedures:

- vaginal hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- mini-laparotomy hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- laparoscopic hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (cervix cut-through)

- open supracervical hysterectomy (cervix cut-through)

- laparoscopic myomectomy (power morcellation)

- mini-laparotomy myomectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- hysteroscopic myomectomy (intrauterine morcellation)

- uterine artery embolization (no specimen and will delay diagnosis)

- high-intensity focused ultrasound (no specimen and will delay diagnosis)

If abdominal hysterectomy is recommended to women with fibroids, will women be better off?

By focusing exclusively on the risk of LMS, the FDA failed to take into account other risks associated with surgery. Laparoscopic surgery uses small incisions, is performed as an outpatient procedure (or overnight stay), has a faster recovery (2 weeks vs 4–6 weeks for open surgery), and is associated with lower mortality and fewer complications. These benefits of minimally invasive surgery are now well established in gynecologic and general surgery.

Using published best-evidence data, a recent decision analysis12 showed that, comparing 100,000 women undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with 100,000 undergoing open hysterectomy, the group undergoing laparoscopic surgery would experience 20 fewer perioperative deaths, 150 fewer pulmonary or venous embolus, and 4,800 fewer wound infections. Importantly, women having open surgery would have 8,000 fewer quality-of-life years.

A recently published study13 found that, in the 8 months following the FDA safety communication, utilization of laparoscopic hysterectomies decreased by 4.1% (P = .005), and abdominal and vaginal hysterectomies increased by 1.7% (P = .112) and 2.4% (P = .012), respectively. Major surgical complications (not including blood transfusions) increased from 2.2% to 2.8% (P = .015), and the rate of hospital readmission within 30 days also increased from 3.4% to 4.2% (P = .025). These observations merit consideration as women weigh the pros and cons of minimally invasive surgery with morcellation versus open surgery. These observations merit consideration as women weigh the pros and cons of minimally invasive surgery with possible morcellation versus open surgery.

Clinical recommendations

Recent attention to surgical options for women with uterine leiomyomas and the risk of an occult leiomyosarcoma are positive developments in that the gynecologic community is re-examining relevant issues. We respectfully suggest that the following clinical recommendations be considered:

- The risk of LMS is higher in older postmenopausal women; greater caution should be exercised prior to recommending morcellation procedures for these women.

- Preoperative consideration of LMS is important. Women aged 35 years and older with irregular uterine bleeding and presumed fibroids should have an endometrial biopsy, which occasionally may detect LMS prior to surgery. Women should have normal results of cervical cancer screening.

- Ultrasound or MRI findings of a large irregular vascular mass, often with irregular anechoic (cystic) areas reflecting necrosis, may cause suspicion of LMS.

- Women wishing minimally invasive procedures with morcellation, including scalpel morcellation via the vagina or mini-laparotomy, or power morcellation using laparoscopic guidance, should understand the potential risk of decreased survival should LMS be present. Open procedures should be offered to all women who are considering minimally invasive procedures for "fibroids."

- Following morcellation, careful inspection for tissue fragments should be undertaken and copious irrigation of the pelvic and abdominal cavities should be performed to minimize the risk of retained tissue.

- Further investigations of a means to identify LMS preoperatively should be supported. Likewise, investigation into the biology of LMS should be funded to better understand the propensity of tissue fragments or cells to implant and grow. With that knowledge, minimally invasive procedures could be avoided for women with LMS and women choosing minimally invasive surgery could be reassured that they do not have LMS.

Respecting women who suffer from leiomyosarcoma, we conclude that the FDA directive was based on a misleading analysis. Consequently, more accurate estimates regarding the prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for fibroids should be issued. Women have a right to self determination. Modification of the FDA's current restrictive guidance regarding power morcellation would empower each woman to consider the pertinent issues and have the freedom to undertake shared decision making with her surgeon in order to select the procedure that is most appropriate for her.

William Parker, MD

Clinical Professor, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine, Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center, Santa Monica, California

Jonathan S. Berek, MD, MMS

Laurie Kraus Lacob Professor and Director, Stanford Women's Cancer Center, Director, Stanford Health Care Communication Program, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Elizabeth Pritts, MD

Wisconsin Fertility Institute, Middleton, Wisconsin

David Olive, MD

Wisconsin Fertility Institute, Middleton, Wisconsin

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville; Director, Menopause and Gynecologic Ultrasound Services, UF Women’s Health Specialists at Emerson, Jacksonville, Florida.

Eva Chalas, MD

Chief, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Director, Clinical Cancer Services, Vice-Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, New York

Daniel Clarke-Pearson, MD

Professor and Chair, Clinical Research, Gynecologic Oncology Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Barbara Goff, MD

Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Robert E. Bristow, MD, MBA

Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, California

Hugh S. Taylor, MD

Anita O'Keeffe Young Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicin; Chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut

Robin Farias-Eisner, MD

Chief, Gynecology and Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD

Director, Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service, Associate Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Director, FJ Montz Fellowship in Gynecologic Oncology, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland

G. Larry Maxwell, MD, COL (ret) US Army

Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; Co-Investigator and Deputy Director of Science, Department of Defense Gynecologic Cancer Translational Research Center of Excellence, Bethesda, Maryland; Professor of Virginia Commonwealth School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia; and Executive Director of Globeathon to End Women’s Cancer

Scott C. Goodwin, MD

Hasso Brothers Professor and Chairman, Radiological Sciences, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California

Susan Love, MD, MBA

Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation, Encino, California

William E. Gibbons, MD

Professor and Director, Division of Reproductive Medicine, Director of Fellowship Training, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine; Chief of Reproductive Medicine at the Pavilion For Women at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas

Leland J. Foshag, MD

Surgical Oncology, Melanoma and Sarcoma, John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica, California

Phyllis C. Leppert, MD, PhD

Emerita Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University School of Medicine; President of The Campion Fund, Phyllis and Mark Leppert Foundation for Fertility Research, Durham, North Carolina

Judy Norsigian

Co-founder of Our Bodies, Ourselves, Boston, Massachusetts

Charles W. Nager, MD

Professor and Chairman, Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of California San Diego Health System

Timothy Robert B. Johnson, MD

Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Professor of Women’s Studies, and Research Professor in the Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

David S. Guzick, MD, PhD

Senior Vice President of Health Affairs, President of UF Health, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

Sawsan As-Sanie, MD, MPH

Assistant Professor and Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Fellowship Director of Endometriosis Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Richard J. Paulson, MD

Alia Tutor Chair in Reproductive Medicine, Professor and Vice-Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chief, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Cindy Farquhar

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and National Women's Health, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Linda Bradley, MD

Vice Chair of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Women’s Health Institute, Director of the Fibroid and Menstrual Disorders Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Stacey A. Scheib, MD

Assistant Professor and Director, Hopkins Multidisciplinary Fibroid Center, Director of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland

Anton J. Bilchik, MD, PhD

Professor of Surgery, Chief of Medicine at John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica, California

Laurel W. Rice, MD

Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Professor, Division of Gynecology Oncology, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin

Carla Dionne

Founder of National Uterine Fibroid Foundation, Colorado Springs, Colorado

Alison Jacoby, MD

Director, University of California-San Francisco Comprehensive Fibroid Center, Interim Chief, Division of Gynecology, University of California San Francisco

Charles Ascher-Walsh, MD

Director of Gynecology, Urogynecology, and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York

Sarah J. Kilpatrick, MD, PhD

Chair of Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Associate Dean of Faculty Development, Helping Hand of Los Angeles Chair in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California

G. David Adamson, MD

Clinical Professor, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California; Past President of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine

Matthew Siedhoff, MD, MSCR

Assistant Professor and Division Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Robert Israel, MD

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chair, Quality Improvement, Director, Women's Health Clinics and Referrals, LAC+USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California

Marie Fidela Paraiso, MD

Head, Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Michael M. Frumovitz, MD, MPH

Fellowship Program Director, Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas

John R. Lurain, MD

Marcia Stenn Professor of Gynecologic Oncology, Program Director, Fellowship in Gynecologic Oncology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois

Ayman Al-Hendy, MD, PhD

Georgia Regents University Director of Interdisciplinary Translational Research; Medical College of Georgia Assistant Dean for Global Translational Research; Professor and Director, Division of Translational Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Georgia Regents Health, Augusta, Georgia

Guy I. Benrubi, MD

Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs, Robert J. Thompson Professor and Chair of Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine – Jacksonville

Steven S. Raman, MD

Professor, Radiology, Urology, and Surgery, Co-director, Fibroid Treatment Program, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Associate Professor and Head, Section of Urogynecology and Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery; Co-Director of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery Fellowship Program, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD

Betty and Lonnie S. Burnett Professor and Chair, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division Director of Gynecology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee

R. Kevin Reynolds, MD

The George W. Morley Professor and Chief, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

John DeLancey, MD

Norman F. Miller Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- US Food and Drug Administration. Medical Devices Safety Communications. UPDATED Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy: FDA Safety Communication. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm424443.htm. Published November 24, 2014. Accessed December 7, 2015.

- Leung F, Terzibachian JJ. Re: "The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma” [letter]. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(1):172–173.

- Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, et al. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1):S29.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek J, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bojahr B, De Wilde R, Tchartchian G. Malignancy rate of 10,731 uteri morcellated during laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LASH). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:665–672.

- Kosary CL. SEER survival monograph: Cancer survival among adults: U.S. SEER program, 1988-2001, patient and tumor characteristics. In: Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, et al, eds. Cancer of the corpus uteri. Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program, NIH; 2007:123–132.

- Park JY, Park SK, Kim DY, et al. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(2):255–259.

- Perri T, Korach J, Sadetzki S, Oberman B, Fridman E, Ben-Baruch G. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: does the primary surgical procedure matter? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(2):257–260.

- Morice P, Rodriguez A, Rey A, et al. Prognostic value of initial surgical procedure for patients with uterine sarcoma: analysis of 123 patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24(3–4):237–240.

- Oduyebo T, Rauh-Hain AJ, Meserve EE, et al. The value of re-exploration in patients with inadvertently morcellated uterine sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(2):360–365.

- Pritts E, Parker W, Brown J, Olive D. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(1):26–33.

- Siedhoff MT, Wheeler SB, Rutstein SE, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation vs abdominal hysterectomy for presumed fibroid tumors in premenopausal women: a decision analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):591.e1–e8.

- Harris JA, Swenson CW, Uppal S, et al. Practice patterns and postoperative complications before and after Food and Drug Administration Safety Communication on power morcellation [published online ahead of print August 24, 2015]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.047.

In November 2014, the FDA ruled that power morcellation was contraindicated in "the majority of women" having surgery for uterine fibroids due to the potential risk of spreading occult uterine sarcoma.1 Although problems with this ruling were immediately apparent, the passage of time has allowed for more clarity on the related medical issues.

Prevalence of leiomyosarcoma among women having surgery for presumed uterine fibroids

The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma among women with fibroids is critical for every patient. All medical procedures have potential risk and the patient's understanding of risk is the foundation of medical decision making.

The FDA estimated that for every 458 women having surgery for fibroids, one woman would be found to have an occult leiomyosarcoma (LMS). We challenge this calculation. To estimate this risk, the FDA searched medical databases using the terms “uterine cancer” AND “hysterectomy or myomectomy.” Because “uterine cancer” was required, studies where cancer was not found or discussed were not identified. Nine studies, all but one of which were retrospective, were analyzed including a non–peer-reviewed Letter to the Editor and an abstract from an unpublished study.2,3

Additionally, 3 leiomyosarcoma cases identified by the FDA do not meet current pathologic criteria for cancer and would now be classified as benign "atypical" leiomyomas. If atypical leiomyomas and non–peer-reviewed data are excluded, the FDA identified 8 cases of LMS among 12,402 women having surgery for presumed leiomyomas, a prevalence of 1 in 1,550 (0.064%).

Pritts and colleagues4 recently published a more rigorous meta-analysis of 133 studies and determined that the prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for presumed fibroids was 1 in 1,960, or 0.051%. All peer-reviewed reports in which surgery was performed for presumed fibroids were analyzed, including reports where cancer was not found. Inclusion criteria required that histopathology results be explicitly provided and available for interpretation. Among the 26 randomized controlled trials analyzed, 1,582 women had surgery for fibroids and none were found to have LMS.

Bojahr and colleagues5 recently published a large population-based prospective registry study and reported 2 occult LMS among 8,720 women having surgery for fibroids (0.023%).

In summary: The re-analyzed FDA dataset yields a prevalence of 1 in 1,550 (0.064%); the Pritts study reports a prevalence of 1 in 1,960 (0.051%), with the RCTs having a prevalence of 0; and the Bojahr study reports a prevalence of 2 of 8,720 (0.023%). We acknowledge that with rare events statistical analysis may be uncertain and confidence intervals may be wide. However, these numbers do not support the FDA's estimated prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for presumed fibroids and those at risk for morcellation of an LMS.

Prognosis for women with morcellated LMS

Women with LMS, removed intact without morcellation, have a poor prognosis. Based on SEER data, the 5-year survival of stage I and II LMS is only 61%.6 Whether morcellation influences the prognosis of women with LMS is not known, and the biology of this tumor has not been well studied. Distant metastases occur early in the disease process, primarily hematogenous dissemination. Four frequently quoted published studies examine survival following power morcellation. Surprisingly, virtually none of the women in these studies had power morcellation. Furthermore, the data presented in these reports are poorly analyzed and patient numbers are very small.

Park and colleagues7 reported only one of the 25 morcellated cases had laparoscopic surgery with power morcellation. Eighteen women had a laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with scalpel morcellation performed through the vagina, one had a vaginal hysterectomy with scalpel-morcellation, and 5 had mini-laparotomy with scalpel morcellation through small lower abdominal incisions. Seventeen of the 25 patients plotted in the published survival curve were referred to the hospital after initial diagnosis or the discovery of a recurrence at another institution. Since the number of nonreferred women with less aggressive disease or without recurrence is not known, it is not possible to determine differences in survival between patients with and without morcellation.

In a study by Perri and colleagues,8 none of the patients had power morcellation: 4 women had abdominal myomectomy; 4 had hysteroscopic myomectomy with tissue confined within the uterine cavity; 2 had laparoscopic hysterectomy with scalpel morcellation; 4 had supracervical abdominal hysterectomy with cut-through at the cervix; and 2 had abdominal hysterectomy with injury to the uterus with a sharp instrument.

When comparing the outcomes for women with morcellated and nonmorcellated LMS, Morice and colleagues9 found no difference in recurrence rates or overall and disease-free survival at 6 months.

In the only study to compare use of power with scalpel morcellation in women with LMS, Oduyebo and colleagues10 found no difference in outcomes for the 10 women with power morcellation and 5 with scalpel morcellation followed for a median of 27 months (range, 2–93 months). Notably, a life table analysis of the above studies showed no difference in survival between morcellation methods.11

Of note, laparoscopic-aided morcellation allows the surgeon to inspect the pelvic and abdominal cavities and irrigate and remove tissue fragments under visual control. In contrast, the surgeon cannot visually inspect the peritoneal cavity during vaginal or mini-laparotomy procedures. Morcellation within containment bags has recently been utilized in an attempt to avoid spread of tissue. This method has not yet been proven effective or safe, and there is concern that bags may make morcellation more cumbersome and less safe.

What the FDA restrictions mean for women

The FDA communication states, "the FDA is warning against the use of laparoscopic power morcellators in the majority of women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids."1 This statement is not consistent with current evidence.

Moreover, a severe restriction of morcellation, including vaginal and mini-laparotomy morcellation, would limit women with symptomatic leiomyomas to one option: total abdominal hysterectomy. For women with fibroids larger than a 10-week pregnancy size, which most often require either scalpel or power morcellation in order to remove tissue, a ban on morcellation would eliminate the following procedures:

- vaginal hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- mini-laparotomy hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- laparoscopic hysterectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (cervix cut-through)

- open supracervical hysterectomy (cervix cut-through)

- laparoscopic myomectomy (power morcellation)

- mini-laparotomy myomectomy (scalpel morcellation)

- hysteroscopic myomectomy (intrauterine morcellation)

- uterine artery embolization (no specimen and will delay diagnosis)

- high-intensity focused ultrasound (no specimen and will delay diagnosis)

If abdominal hysterectomy is recommended to women with fibroids, will women be better off?

By focusing exclusively on the risk of LMS, the FDA failed to take into account other risks associated with surgery. Laparoscopic surgery uses small incisions, is performed as an outpatient procedure (or overnight stay), has a faster recovery (2 weeks vs 4–6 weeks for open surgery), and is associated with lower mortality and fewer complications. These benefits of minimally invasive surgery are now well established in gynecologic and general surgery.

Using published best-evidence data, a recent decision analysis12 showed that, comparing 100,000 women undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with 100,000 undergoing open hysterectomy, the group undergoing laparoscopic surgery would experience 20 fewer perioperative deaths, 150 fewer pulmonary or venous embolus, and 4,800 fewer wound infections. Importantly, women having open surgery would have 8,000 fewer quality-of-life years.

A recently published study13 found that, in the 8 months following the FDA safety communication, utilization of laparoscopic hysterectomies decreased by 4.1% (P = .005), and abdominal and vaginal hysterectomies increased by 1.7% (P = .112) and 2.4% (P = .012), respectively. Major surgical complications (not including blood transfusions) increased from 2.2% to 2.8% (P = .015), and the rate of hospital readmission within 30 days also increased from 3.4% to 4.2% (P = .025). These observations merit consideration as women weigh the pros and cons of minimally invasive surgery with morcellation versus open surgery. These observations merit consideration as women weigh the pros and cons of minimally invasive surgery with possible morcellation versus open surgery.

Clinical recommendations

Recent attention to surgical options for women with uterine leiomyomas and the risk of an occult leiomyosarcoma are positive developments in that the gynecologic community is re-examining relevant issues. We respectfully suggest that the following clinical recommendations be considered:

- The risk of LMS is higher in older postmenopausal women; greater caution should be exercised prior to recommending morcellation procedures for these women.

- Preoperative consideration of LMS is important. Women aged 35 years and older with irregular uterine bleeding and presumed fibroids should have an endometrial biopsy, which occasionally may detect LMS prior to surgery. Women should have normal results of cervical cancer screening.

- Ultrasound or MRI findings of a large irregular vascular mass, often with irregular anechoic (cystic) areas reflecting necrosis, may cause suspicion of LMS.

- Women wishing minimally invasive procedures with morcellation, including scalpel morcellation via the vagina or mini-laparotomy, or power morcellation using laparoscopic guidance, should understand the potential risk of decreased survival should LMS be present. Open procedures should be offered to all women who are considering minimally invasive procedures for "fibroids."

- Following morcellation, careful inspection for tissue fragments should be undertaken and copious irrigation of the pelvic and abdominal cavities should be performed to minimize the risk of retained tissue.

- Further investigations of a means to identify LMS preoperatively should be supported. Likewise, investigation into the biology of LMS should be funded to better understand the propensity of tissue fragments or cells to implant and grow. With that knowledge, minimally invasive procedures could be avoided for women with LMS and women choosing minimally invasive surgery could be reassured that they do not have LMS.

Respecting women who suffer from leiomyosarcoma, we conclude that the FDA directive was based on a misleading analysis. Consequently, more accurate estimates regarding the prevalence of LMS among women having surgery for fibroids should be issued. Women have a right to self determination. Modification of the FDA's current restrictive guidance regarding power morcellation would empower each woman to consider the pertinent issues and have the freedom to undertake shared decision making with her surgeon in order to select the procedure that is most appropriate for her.

William Parker, MD

Clinical Professor, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine, Director, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center, Santa Monica, California

Jonathan S. Berek, MD, MMS

Laurie Kraus Lacob Professor and Director, Stanford Women's Cancer Center, Director, Stanford Health Care Communication Program, Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Elizabeth Pritts, MD

Wisconsin Fertility Institute, Middleton, Wisconsin

David Olive, MD

Wisconsin Fertility Institute, Middleton, Wisconsin

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville; Director, Menopause and Gynecologic Ultrasound Services, UF Women’s Health Specialists at Emerson, Jacksonville, Florida.

Eva Chalas, MD

Chief, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Director, Clinical Cancer Services, Vice-Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Winthrop-University Hospital, Mineola, New York

Daniel Clarke-Pearson, MD

Professor and Chair, Clinical Research, Gynecologic Oncology Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Barbara Goff, MD

Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Robert E. Bristow, MD, MBA

Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Orange, California

Hugh S. Taylor, MD

Anita O'Keeffe Young Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicin; Chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut

Robin Farias-Eisner, MD

Chief, Gynecology and Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD

Director, Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service, Associate Professor of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Director, FJ Montz Fellowship in Gynecologic Oncology, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland

G. Larry Maxwell, MD, COL (ret) US Army

Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; Co-Investigator and Deputy Director of Science, Department of Defense Gynecologic Cancer Translational Research Center of Excellence, Bethesda, Maryland; Professor of Virginia Commonwealth School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia; and Executive Director of Globeathon to End Women’s Cancer

Scott C. Goodwin, MD

Hasso Brothers Professor and Chairman, Radiological Sciences, University of California Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California

Susan Love, MD, MBA

Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation, Encino, California

William E. Gibbons, MD

Professor and Director, Division of Reproductive Medicine, Director of Fellowship Training, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine; Chief of Reproductive Medicine at the Pavilion For Women at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas

Leland J. Foshag, MD

Surgical Oncology, Melanoma and Sarcoma, John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica, California

Phyllis C. Leppert, MD, PhD

Emerita Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University School of Medicine; President of The Campion Fund, Phyllis and Mark Leppert Foundation for Fertility Research, Durham, North Carolina

Judy Norsigian

Co-founder of Our Bodies, Ourselves, Boston, Massachusetts

Charles W. Nager, MD

Professor and Chairman, Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of California San Diego Health System

Timothy Robert B. Johnson, MD

Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Professor of Women’s Studies, and Research Professor in the Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

David S. Guzick, MD, PhD