User login

Insulin pumps: Great devices, but you still have to press the button

In this issue of the Journal, Millstein et al provide an elegant, practical, and up-to-date review of insulin pump therapy (also known as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion), emphasizing its benefits and comparing it with multiple daily insulin injections.1

NOT FOR EVERYONE

While insulin pumps make the lives of many patients much easier, we should be careful when generalizing their indications. These devices have been with us for 4 decades, during which they have progressively been made more precise and more intelligent—and smaller. The technology may be attractive to some patients but undesirable to others (Table 1).

Many healthcare providers are unfamiliar with pump technology, and some are intimidated by it because it involves a dynamic device-user interface that is more complex than that of other concealed programmed devices such as pacemakers. Inadequate glycemic management is complex and may result from factors such as fear of hypoglycemia, difficulty with insulin dose adjustment, and poor math skills.2

Unfortunately, some patients are given a pump without proper screening and education, and they tend to call the pump manufacturer’s help line or their provider often for help with technical problems. Selecting the right patient for this technology is more important than the converse.

Indications for an insulin pump vary by country. In some countries, a pump is started as soon as type 1 diabetes is diagnosed. In the United States, the indications are very rigorous and restrictive, especially for patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom a lack of endogenous insulin production must first be proved.

There is no question that a pump should be offered to every patient with type 1 diabetes who demonstrates good motivation to improve his or her glucose control, but only after a rigorous education program. This option is too costly to be tried just to see if the patient likes it.

ADVERSE EVENTS WITH INSULIN PUMPS: MORE DATA NEEDED

A worrisome aspect of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion at a population level is a lack of information on the root causes of adverse events (diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia) in patients who use it. These events may be serious and sometimes even fatal.

Outside of a controlled environment, it is difficult to ascertain whether an adverse event represents device error or user error, since pumps contain different components (electronic, mechanical, and pharmacologic) that interface with the human user.3 How adverse events are tracked or categorized is unclear, and given the risks associated with this technology, better postmarketing evaluation is needed. Furthermore, we do not know if the precision of insulin delivery decreases over the life of a pump.

While most pump manufacturers have good customer service and make every effort to provide the patient with a replacement pump in case of failure, we do not know if anyone maintains a database of such failures or adverse events, and if those failures can be analyzed to improve safety.3

INTERFACES ARE NOT STANDARD

When one buys a new car, little time is needed to learn how to operate it because most cars use the same basic features.

The situation is different with insulin pumps. To compete with each other, pump manufacturers create different looks, different insulin delivery methods, and different ways of administering a bolus. Switching from one pump to another is difficult without detailed education on the “bells and whistles” of the new pump.

Most patients use just a few features of the pump. They look at it as more of a convenience. They sometimes forget they are wearing it, and even forget to take a bolus before a meal.

PATIENT SATISFACTION DEPENDS ON THE PATIENT

For years, we thought insulin pumps were better at improving hypoglycemia awareness. But in a prospective study, multiple daily injections with frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose provided identical outcomes without worsening hemoglobin A1c compared with continuous infusion with real-time continuous glucose monitoring, although satisfaction with treatment was better in the latter group.4

Patients’ satisfaction with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion depends on their baseline hemoglobin A1c level. Patients with relatively low hemoglobin A1c tend to take an active approach to self-care, describe the pump as a tool for meeting glycemic goals, and say the pump makes them feel more normal. Patients with high hemoglobin A1c tend to have a more passive approach to their self-care and have more negative experiences with the pump. Women are more concerned than men with the effect of the pump on body image and social acceptance.5

DOLLARS AND CENTS

According to 2012 estimates, 29 million Americans had diabetes mellitus, of whom 1.25 million had type 1. The direct medical costs of diabetes are estimated at $176 billion, of which 12% covers overall pharmacy costs.6 About 31% of adults with diabetes use insulin.7

For a device that costs $6,000, has a life span of only 4 years, and requires supplies that cost $300 per month, rigorous interpretation of superiority data would be needed to confirm that this technology would have a positive impact on public health if every insulin-using patient with diabetes were to say yes to it. It is true that switching from multiple daily injections to a pump leads to a significant reduction in insulin expenditures in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to a retrospective analysis of claims data.8

However, not all studies comparing pumps and multiple daily injections in type 2 diabetes have shown an advantage of one over the other in terms of a reduction in fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or incidence of hypoglycemia.9 A meta-analysis10 found that the two therapies had similar effects on glycemic control and hypoglycemia. Continuous infusion had a more favorable effect in adults with type 1 diabetes.10

Neither continuous infusion nor multiple daily injections can mimic physiologic endogenous insulin secretion. Endogenous insulin is secreted into the portal system, and its main site of action is the liver. As a result, there is more hepatic glucose uptake and thus a lower peripheral plasma insulin concentration with endogenous secretion than with systemic administration. Endogenous insulin secretion also suppresses hepatic glucose production and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia.11

PROGRESS, BUT NOT PERFECTION

Diabetes mellitus constitutes a big burden on patients and on society. The discovery of insulin was a giant leap forward; the insulin pump was another great advance. We are getting closer to an integrated bionic pancreas. We are far from achieving a perfect system, but we are much better off than we were 50 or 80 years ago. And although insulin pump technology is sophisticated and precise, it still interfaces with a human user, and the human user still must press its buttons.

- Millstein R, Mora Becerra N, Shubrook JH. Insulin pumps: beyond basal-bolus. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:835–842.

- Cavan DA, Ziegler R, Cranston I, et al. Automated bolus advisor control and usability study (ABACUS): does use of an insulin bolus advisor improve glycaemic control in patients failing multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy? [NCT01460446]. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13:102.

- Heinemann L, Fleming GA, Petrie JR, Holl RW, Bergenstal RM, Peters AL. Insulin pump risks and benefits: a clinical appraisal of pump safety standards, adverse event reporting, and research needs: a joint statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:716–722.

- Little SA, Leelarathna L, Walkinshaw E, et al. Recovery of hypoglycemia awareness in long-standing type 1 diabetes: a multicenter 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled trial comparing insulin pump with multiple daily injections and continuous with conventional glucose self-monitoring (HypoCOMPaSS). Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2114–2122.

- Ritholz MD, Smaldone A, Lee J, Castillo A, Wolpert H, Weinger K. Perceptions of psychosocial factors and the insulin pump. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:549–554.

- American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes. Overall numbers, diabetes and prediabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Age-adjusted percentage of adults with diabetes using diabetes medication, by type of medication, United States, 1997–2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig2.htm. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- David G, Gill M, Gunnarsson C, Shafiroff J, Edelman S. Switching from multiple daily injections to CSII pump therapy: insulin expenditures in type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care; 20:e490–e497.

- Gao GQ, Heng XY, Wang YL, et al. Comparison of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and insulin glargine-based multiple daily insulin aspart injections with preferential adjustment of basal insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8:1191–1196.

- Yeh HC, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:336–347.

- Logtenberg SJ, van Ballegooie E, Israêl-Bultman H, van Linde A, Bilo HJ. Glycaemic control, health status and treatment satisfaction with continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion. Neth J Med 2007; 65:65–70.

In this issue of the Journal, Millstein et al provide an elegant, practical, and up-to-date review of insulin pump therapy (also known as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion), emphasizing its benefits and comparing it with multiple daily insulin injections.1

NOT FOR EVERYONE

While insulin pumps make the lives of many patients much easier, we should be careful when generalizing their indications. These devices have been with us for 4 decades, during which they have progressively been made more precise and more intelligent—and smaller. The technology may be attractive to some patients but undesirable to others (Table 1).

Many healthcare providers are unfamiliar with pump technology, and some are intimidated by it because it involves a dynamic device-user interface that is more complex than that of other concealed programmed devices such as pacemakers. Inadequate glycemic management is complex and may result from factors such as fear of hypoglycemia, difficulty with insulin dose adjustment, and poor math skills.2

Unfortunately, some patients are given a pump without proper screening and education, and they tend to call the pump manufacturer’s help line or their provider often for help with technical problems. Selecting the right patient for this technology is more important than the converse.

Indications for an insulin pump vary by country. In some countries, a pump is started as soon as type 1 diabetes is diagnosed. In the United States, the indications are very rigorous and restrictive, especially for patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom a lack of endogenous insulin production must first be proved.

There is no question that a pump should be offered to every patient with type 1 diabetes who demonstrates good motivation to improve his or her glucose control, but only after a rigorous education program. This option is too costly to be tried just to see if the patient likes it.

ADVERSE EVENTS WITH INSULIN PUMPS: MORE DATA NEEDED

A worrisome aspect of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion at a population level is a lack of information on the root causes of adverse events (diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia) in patients who use it. These events may be serious and sometimes even fatal.

Outside of a controlled environment, it is difficult to ascertain whether an adverse event represents device error or user error, since pumps contain different components (electronic, mechanical, and pharmacologic) that interface with the human user.3 How adverse events are tracked or categorized is unclear, and given the risks associated with this technology, better postmarketing evaluation is needed. Furthermore, we do not know if the precision of insulin delivery decreases over the life of a pump.

While most pump manufacturers have good customer service and make every effort to provide the patient with a replacement pump in case of failure, we do not know if anyone maintains a database of such failures or adverse events, and if those failures can be analyzed to improve safety.3

INTERFACES ARE NOT STANDARD

When one buys a new car, little time is needed to learn how to operate it because most cars use the same basic features.

The situation is different with insulin pumps. To compete with each other, pump manufacturers create different looks, different insulin delivery methods, and different ways of administering a bolus. Switching from one pump to another is difficult without detailed education on the “bells and whistles” of the new pump.

Most patients use just a few features of the pump. They look at it as more of a convenience. They sometimes forget they are wearing it, and even forget to take a bolus before a meal.

PATIENT SATISFACTION DEPENDS ON THE PATIENT

For years, we thought insulin pumps were better at improving hypoglycemia awareness. But in a prospective study, multiple daily injections with frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose provided identical outcomes without worsening hemoglobin A1c compared with continuous infusion with real-time continuous glucose monitoring, although satisfaction with treatment was better in the latter group.4

Patients’ satisfaction with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion depends on their baseline hemoglobin A1c level. Patients with relatively low hemoglobin A1c tend to take an active approach to self-care, describe the pump as a tool for meeting glycemic goals, and say the pump makes them feel more normal. Patients with high hemoglobin A1c tend to have a more passive approach to their self-care and have more negative experiences with the pump. Women are more concerned than men with the effect of the pump on body image and social acceptance.5

DOLLARS AND CENTS

According to 2012 estimates, 29 million Americans had diabetes mellitus, of whom 1.25 million had type 1. The direct medical costs of diabetes are estimated at $176 billion, of which 12% covers overall pharmacy costs.6 About 31% of adults with diabetes use insulin.7

For a device that costs $6,000, has a life span of only 4 years, and requires supplies that cost $300 per month, rigorous interpretation of superiority data would be needed to confirm that this technology would have a positive impact on public health if every insulin-using patient with diabetes were to say yes to it. It is true that switching from multiple daily injections to a pump leads to a significant reduction in insulin expenditures in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to a retrospective analysis of claims data.8

However, not all studies comparing pumps and multiple daily injections in type 2 diabetes have shown an advantage of one over the other in terms of a reduction in fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or incidence of hypoglycemia.9 A meta-analysis10 found that the two therapies had similar effects on glycemic control and hypoglycemia. Continuous infusion had a more favorable effect in adults with type 1 diabetes.10

Neither continuous infusion nor multiple daily injections can mimic physiologic endogenous insulin secretion. Endogenous insulin is secreted into the portal system, and its main site of action is the liver. As a result, there is more hepatic glucose uptake and thus a lower peripheral plasma insulin concentration with endogenous secretion than with systemic administration. Endogenous insulin secretion also suppresses hepatic glucose production and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia.11

PROGRESS, BUT NOT PERFECTION

Diabetes mellitus constitutes a big burden on patients and on society. The discovery of insulin was a giant leap forward; the insulin pump was another great advance. We are getting closer to an integrated bionic pancreas. We are far from achieving a perfect system, but we are much better off than we were 50 or 80 years ago. And although insulin pump technology is sophisticated and precise, it still interfaces with a human user, and the human user still must press its buttons.

In this issue of the Journal, Millstein et al provide an elegant, practical, and up-to-date review of insulin pump therapy (also known as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion), emphasizing its benefits and comparing it with multiple daily insulin injections.1

NOT FOR EVERYONE

While insulin pumps make the lives of many patients much easier, we should be careful when generalizing their indications. These devices have been with us for 4 decades, during which they have progressively been made more precise and more intelligent—and smaller. The technology may be attractive to some patients but undesirable to others (Table 1).

Many healthcare providers are unfamiliar with pump technology, and some are intimidated by it because it involves a dynamic device-user interface that is more complex than that of other concealed programmed devices such as pacemakers. Inadequate glycemic management is complex and may result from factors such as fear of hypoglycemia, difficulty with insulin dose adjustment, and poor math skills.2

Unfortunately, some patients are given a pump without proper screening and education, and they tend to call the pump manufacturer’s help line or their provider often for help with technical problems. Selecting the right patient for this technology is more important than the converse.

Indications for an insulin pump vary by country. In some countries, a pump is started as soon as type 1 diabetes is diagnosed. In the United States, the indications are very rigorous and restrictive, especially for patients with type 2 diabetes, in whom a lack of endogenous insulin production must first be proved.

There is no question that a pump should be offered to every patient with type 1 diabetes who demonstrates good motivation to improve his or her glucose control, but only after a rigorous education program. This option is too costly to be tried just to see if the patient likes it.

ADVERSE EVENTS WITH INSULIN PUMPS: MORE DATA NEEDED

A worrisome aspect of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion at a population level is a lack of information on the root causes of adverse events (diabetic ketoacidosis or severe hypoglycemia) in patients who use it. These events may be serious and sometimes even fatal.

Outside of a controlled environment, it is difficult to ascertain whether an adverse event represents device error or user error, since pumps contain different components (electronic, mechanical, and pharmacologic) that interface with the human user.3 How adverse events are tracked or categorized is unclear, and given the risks associated with this technology, better postmarketing evaluation is needed. Furthermore, we do not know if the precision of insulin delivery decreases over the life of a pump.

While most pump manufacturers have good customer service and make every effort to provide the patient with a replacement pump in case of failure, we do not know if anyone maintains a database of such failures or adverse events, and if those failures can be analyzed to improve safety.3

INTERFACES ARE NOT STANDARD

When one buys a new car, little time is needed to learn how to operate it because most cars use the same basic features.

The situation is different with insulin pumps. To compete with each other, pump manufacturers create different looks, different insulin delivery methods, and different ways of administering a bolus. Switching from one pump to another is difficult without detailed education on the “bells and whistles” of the new pump.

Most patients use just a few features of the pump. They look at it as more of a convenience. They sometimes forget they are wearing it, and even forget to take a bolus before a meal.

PATIENT SATISFACTION DEPENDS ON THE PATIENT

For years, we thought insulin pumps were better at improving hypoglycemia awareness. But in a prospective study, multiple daily injections with frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose provided identical outcomes without worsening hemoglobin A1c compared with continuous infusion with real-time continuous glucose monitoring, although satisfaction with treatment was better in the latter group.4

Patients’ satisfaction with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion depends on their baseline hemoglobin A1c level. Patients with relatively low hemoglobin A1c tend to take an active approach to self-care, describe the pump as a tool for meeting glycemic goals, and say the pump makes them feel more normal. Patients with high hemoglobin A1c tend to have a more passive approach to their self-care and have more negative experiences with the pump. Women are more concerned than men with the effect of the pump on body image and social acceptance.5

DOLLARS AND CENTS

According to 2012 estimates, 29 million Americans had diabetes mellitus, of whom 1.25 million had type 1. The direct medical costs of diabetes are estimated at $176 billion, of which 12% covers overall pharmacy costs.6 About 31% of adults with diabetes use insulin.7

For a device that costs $6,000, has a life span of only 4 years, and requires supplies that cost $300 per month, rigorous interpretation of superiority data would be needed to confirm that this technology would have a positive impact on public health if every insulin-using patient with diabetes were to say yes to it. It is true that switching from multiple daily injections to a pump leads to a significant reduction in insulin expenditures in patients with type 2 diabetes, according to a retrospective analysis of claims data.8

However, not all studies comparing pumps and multiple daily injections in type 2 diabetes have shown an advantage of one over the other in terms of a reduction in fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or incidence of hypoglycemia.9 A meta-analysis10 found that the two therapies had similar effects on glycemic control and hypoglycemia. Continuous infusion had a more favorable effect in adults with type 1 diabetes.10

Neither continuous infusion nor multiple daily injections can mimic physiologic endogenous insulin secretion. Endogenous insulin is secreted into the portal system, and its main site of action is the liver. As a result, there is more hepatic glucose uptake and thus a lower peripheral plasma insulin concentration with endogenous secretion than with systemic administration. Endogenous insulin secretion also suppresses hepatic glucose production and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia.11

PROGRESS, BUT NOT PERFECTION

Diabetes mellitus constitutes a big burden on patients and on society. The discovery of insulin was a giant leap forward; the insulin pump was another great advance. We are getting closer to an integrated bionic pancreas. We are far from achieving a perfect system, but we are much better off than we were 50 or 80 years ago. And although insulin pump technology is sophisticated and precise, it still interfaces with a human user, and the human user still must press its buttons.

- Millstein R, Mora Becerra N, Shubrook JH. Insulin pumps: beyond basal-bolus. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:835–842.

- Cavan DA, Ziegler R, Cranston I, et al. Automated bolus advisor control and usability study (ABACUS): does use of an insulin bolus advisor improve glycaemic control in patients failing multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy? [NCT01460446]. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13:102.

- Heinemann L, Fleming GA, Petrie JR, Holl RW, Bergenstal RM, Peters AL. Insulin pump risks and benefits: a clinical appraisal of pump safety standards, adverse event reporting, and research needs: a joint statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:716–722.

- Little SA, Leelarathna L, Walkinshaw E, et al. Recovery of hypoglycemia awareness in long-standing type 1 diabetes: a multicenter 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled trial comparing insulin pump with multiple daily injections and continuous with conventional glucose self-monitoring (HypoCOMPaSS). Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2114–2122.

- Ritholz MD, Smaldone A, Lee J, Castillo A, Wolpert H, Weinger K. Perceptions of psychosocial factors and the insulin pump. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:549–554.

- American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes. Overall numbers, diabetes and prediabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Age-adjusted percentage of adults with diabetes using diabetes medication, by type of medication, United States, 1997–2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig2.htm. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- David G, Gill M, Gunnarsson C, Shafiroff J, Edelman S. Switching from multiple daily injections to CSII pump therapy: insulin expenditures in type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care; 20:e490–e497.

- Gao GQ, Heng XY, Wang YL, et al. Comparison of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and insulin glargine-based multiple daily insulin aspart injections with preferential adjustment of basal insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8:1191–1196.

- Yeh HC, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:336–347.

- Logtenberg SJ, van Ballegooie E, Israêl-Bultman H, van Linde A, Bilo HJ. Glycaemic control, health status and treatment satisfaction with continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion. Neth J Med 2007; 65:65–70.

- Millstein R, Mora Becerra N, Shubrook JH. Insulin pumps: beyond basal-bolus. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:835–842.

- Cavan DA, Ziegler R, Cranston I, et al. Automated bolus advisor control and usability study (ABACUS): does use of an insulin bolus advisor improve glycaemic control in patients failing multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy? [NCT01460446]. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13:102.

- Heinemann L, Fleming GA, Petrie JR, Holl RW, Bergenstal RM, Peters AL. Insulin pump risks and benefits: a clinical appraisal of pump safety standards, adverse event reporting, and research needs: a joint statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association Diabetes Technology Working Group. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:716–722.

- Little SA, Leelarathna L, Walkinshaw E, et al. Recovery of hypoglycemia awareness in long-standing type 1 diabetes: a multicenter 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled trial comparing insulin pump with multiple daily injections and continuous with conventional glucose self-monitoring (HypoCOMPaSS). Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2114–2122.

- Ritholz MD, Smaldone A, Lee J, Castillo A, Wolpert H, Weinger K. Perceptions of psychosocial factors and the insulin pump. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:549–554.

- American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes. Overall numbers, diabetes and prediabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Age-adjusted percentage of adults with diabetes using diabetes medication, by type of medication, United States, 1997–2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig2.htm. Accessed November 4, 2015.

- David G, Gill M, Gunnarsson C, Shafiroff J, Edelman S. Switching from multiple daily injections to CSII pump therapy: insulin expenditures in type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care; 20:e490–e497.

- Gao GQ, Heng XY, Wang YL, et al. Comparison of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and insulin glargine-based multiple daily insulin aspart injections with preferential adjustment of basal insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med 2014; 8:1191–1196.

- Yeh HC, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:336–347.

- Logtenberg SJ, van Ballegooie E, Israêl-Bultman H, van Linde A, Bilo HJ. Glycaemic control, health status and treatment satisfaction with continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion. Neth J Med 2007; 65:65–70.

Breast milk: Good? Better? Best?

When you finish reading this column … on second thought, stop now and read the Oct. 17, 2015, opinion piece titled “Overselling Breast-Feeding.” You will discover a well-researched and thoughtfully crafted article by Courtney Jung, a political science professor at the University of Toronto, in which she dares to carefully dissect one of our most revered sacred cows. The result is a convincing argument for rethinking how we present and promote breastfeeding. I won’t attempt to reconstruct her rationale. You can read it for yourself. But, I suspect that if you spend any part of your day trying to help new parents navigate the choppy waters of those first 6 months, you will find what she has to say strikes more than a few familiar chords.

Like most of you, what I learned about breastfeeding came as on the job training. Marilyn and I started our family while I was still in medical school, giving me the advantage of having watched the process bump along twice before I found myself on the frontline of private practice. I had been taught in school about all the advantages breast milk, but it didn’t take long in the real world to discover that breastfeeding could have a dark side.

I had to become a chameleon. I needed to be strong advocate for the advantages of breast milk and support new mothers as they tried to match the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines. However, there were situations in which despite everyone’s best efforts, the handwriting on the wall said, “This isn’t working.” Then it was time to change my colors and convincingly convey the new truth that even a baby that isn’t breastfed is going to be fine. That a woman who doesn’t breastfeed can and will be a mother every bit as good as one who doesn’t breastfed her baby for 6 months or a year.

The tension between the party line and reality became so great that in frustration I decided to write my third book about breastfeeding. The result was “The Maternity Leave Breastfeeding Plan” (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002). The watered-down title was chosen by the publisher. The subtitle, “How to Enjoy Nursing for 3 Months and Go Back to Work Guilt-Free,” was a better reflection of my message that there can be some serious challenges to breastfeeding and not to worry if it doesn’t work. Surprisingly, it found itself on a La Leche League list of recommended books – that is until someone in the organization actually read it.

Although I had always harbored doubts that many of the studies purporting to show the advantages of breastfeeding were poorly controlled, in 2002, I couldn’t find any data to support my concerns. But over the last decade those studies have begun to emerge and Professor Jung has found them and included them in her new book, “Lactivism: How Feminists and Fundamentalists, Hippies and Yuppies, and Physicians and Politicians Made Breastfeeding Big Business and Bad Policy” (New York: Basic Books, 2015).

It will be interesting to see how her observations play to the wider audience it deserves. The discussions may be lively and heated, and public opinion may shift a bit. But what won’t change is that those of us who deal with mothers and babies in a very personal way will still have to struggle with promoting a good product that isn’t always easy to obtain.

Breast milk is good … but it isn’t always better or best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When you finish reading this column … on second thought, stop now and read the Oct. 17, 2015, opinion piece titled “Overselling Breast-Feeding.” You will discover a well-researched and thoughtfully crafted article by Courtney Jung, a political science professor at the University of Toronto, in which she dares to carefully dissect one of our most revered sacred cows. The result is a convincing argument for rethinking how we present and promote breastfeeding. I won’t attempt to reconstruct her rationale. You can read it for yourself. But, I suspect that if you spend any part of your day trying to help new parents navigate the choppy waters of those first 6 months, you will find what she has to say strikes more than a few familiar chords.

Like most of you, what I learned about breastfeeding came as on the job training. Marilyn and I started our family while I was still in medical school, giving me the advantage of having watched the process bump along twice before I found myself on the frontline of private practice. I had been taught in school about all the advantages breast milk, but it didn’t take long in the real world to discover that breastfeeding could have a dark side.

I had to become a chameleon. I needed to be strong advocate for the advantages of breast milk and support new mothers as they tried to match the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines. However, there were situations in which despite everyone’s best efforts, the handwriting on the wall said, “This isn’t working.” Then it was time to change my colors and convincingly convey the new truth that even a baby that isn’t breastfed is going to be fine. That a woman who doesn’t breastfeed can and will be a mother every bit as good as one who doesn’t breastfed her baby for 6 months or a year.

The tension between the party line and reality became so great that in frustration I decided to write my third book about breastfeeding. The result was “The Maternity Leave Breastfeeding Plan” (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002). The watered-down title was chosen by the publisher. The subtitle, “How to Enjoy Nursing for 3 Months and Go Back to Work Guilt-Free,” was a better reflection of my message that there can be some serious challenges to breastfeeding and not to worry if it doesn’t work. Surprisingly, it found itself on a La Leche League list of recommended books – that is until someone in the organization actually read it.

Although I had always harbored doubts that many of the studies purporting to show the advantages of breastfeeding were poorly controlled, in 2002, I couldn’t find any data to support my concerns. But over the last decade those studies have begun to emerge and Professor Jung has found them and included them in her new book, “Lactivism: How Feminists and Fundamentalists, Hippies and Yuppies, and Physicians and Politicians Made Breastfeeding Big Business and Bad Policy” (New York: Basic Books, 2015).

It will be interesting to see how her observations play to the wider audience it deserves. The discussions may be lively and heated, and public opinion may shift a bit. But what won’t change is that those of us who deal with mothers and babies in a very personal way will still have to struggle with promoting a good product that isn’t always easy to obtain.

Breast milk is good … but it isn’t always better or best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

When you finish reading this column … on second thought, stop now and read the Oct. 17, 2015, opinion piece titled “Overselling Breast-Feeding.” You will discover a well-researched and thoughtfully crafted article by Courtney Jung, a political science professor at the University of Toronto, in which she dares to carefully dissect one of our most revered sacred cows. The result is a convincing argument for rethinking how we present and promote breastfeeding. I won’t attempt to reconstruct her rationale. You can read it for yourself. But, I suspect that if you spend any part of your day trying to help new parents navigate the choppy waters of those first 6 months, you will find what she has to say strikes more than a few familiar chords.

Like most of you, what I learned about breastfeeding came as on the job training. Marilyn and I started our family while I was still in medical school, giving me the advantage of having watched the process bump along twice before I found myself on the frontline of private practice. I had been taught in school about all the advantages breast milk, but it didn’t take long in the real world to discover that breastfeeding could have a dark side.

I had to become a chameleon. I needed to be strong advocate for the advantages of breast milk and support new mothers as they tried to match the American Academy of Pediatrics’ guidelines. However, there were situations in which despite everyone’s best efforts, the handwriting on the wall said, “This isn’t working.” Then it was time to change my colors and convincingly convey the new truth that even a baby that isn’t breastfed is going to be fine. That a woman who doesn’t breastfeed can and will be a mother every bit as good as one who doesn’t breastfed her baby for 6 months or a year.

The tension between the party line and reality became so great that in frustration I decided to write my third book about breastfeeding. The result was “The Maternity Leave Breastfeeding Plan” (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002). The watered-down title was chosen by the publisher. The subtitle, “How to Enjoy Nursing for 3 Months and Go Back to Work Guilt-Free,” was a better reflection of my message that there can be some serious challenges to breastfeeding and not to worry if it doesn’t work. Surprisingly, it found itself on a La Leche League list of recommended books – that is until someone in the organization actually read it.

Although I had always harbored doubts that many of the studies purporting to show the advantages of breastfeeding were poorly controlled, in 2002, I couldn’t find any data to support my concerns. But over the last decade those studies have begun to emerge and Professor Jung has found them and included them in her new book, “Lactivism: How Feminists and Fundamentalists, Hippies and Yuppies, and Physicians and Politicians Made Breastfeeding Big Business and Bad Policy” (New York: Basic Books, 2015).

It will be interesting to see how her observations play to the wider audience it deserves. The discussions may be lively and heated, and public opinion may shift a bit. But what won’t change is that those of us who deal with mothers and babies in a very personal way will still have to struggle with promoting a good product that isn’t always easy to obtain.

Breast milk is good … but it isn’t always better or best.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Let’s roll!

Imagine yourself in a small community hospital standing at the bedside of a tiny preemie waiting for the neonatal transport team to return your call for help.

With one eye shifting between the clock and the oximeter, you have the other one looking out the window hoping that the predicted snow and freezing rain will hold out for another hour. You have done everything you can do, but clearly it’s not going to be enough to rescue this little person who had the misfortune of exiting the birth canal several months too early.

You have been able to insert an umbilical vein catheter and miraculously have threaded an endotracheal tube into a trachea that looked no bigger than a piece of spaghetti, or maybe you have failed and the nurses are taking turns bagging. The transport team returns your call for help and with apologies reports that they are tied up with a similar scenario further south; they predict that it may be an hour and a half before they will be able to get back to their hospital, which is a half hour down the road from you.

They suggest some things that you have already done. Should you wait for more skilled hands and their equipment or transport the patient yourself and get on the road before it becomes a skating rink? There is an antique transport isolette gathering dust in the storage room down the hall, and the local fire department ambulance crew with whom you are on a first-name basis is always ready to help. Is it time to gather the troops and tell them, “Let’s roll!” ?

If you have ever lived through a similar scenario, you may find a recent study interesting (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163[9]:681-90). What these investigators found was that for adults who had suffered major trauma, stroke, respiratory failure, and acute myocardial infarction, those who were transported by crews with basic life support (BLS) skills had significantly better long-term survival and neurologic outcomes than did those victims transported by crews with advanced life support (ALS) skills.

In the flurry of comments that circulated following the release of the study were a few questions about the methodology, but most commentators were searching for an explanation. Was critical time lost by the ALS crews doing stuff when the better course of action would have been to get the ambulance rolling to the hospital and more definitive care? Does the temptation to do things because you can do them sometimes cloud the decision-making process?

Although I have lived the scenario I described, it is less likely to happen now. Backup teams from other institutions may be activated. The teams are so well equipped and trained that the gaps between their capabilities and the neonatal intensive care unit have narrowed, but there is no question that they remain and are significant.

The other thing that hasn’t changed is the weather here in Maine. While we have beautiful summers that prompt us to put “Vacationland” on our license plates, our winters are a challenge. In addition to the patient’s condition and the availability of resources, the decision of whether to invest time in stabilization or get moving toward the referral center also must include the risk to the patient and staff who will be traveling on weather-threatened roads.

On the other hand, we can’t ignore the elephant that occasionally finds its way into the room when decisions are made about how thoroughly a critically ill patient is stabilized and how speedily he is transferred. And, that ponderous pachyderm is the hot potato factor and sometimes answers to its acronym, NIMBY (“not in my back yard”). You know as well as I do that despite the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) regulations, there are cases when a patient is hustled out the door without being appropriately stabilized primarily to avoid having that patient die in the referring hospital. We must continue to ask ourselves if we have done everything that we can do to stabilize the patient before we say, “Let’s roll!”

William G. Wilkoff, M.D., practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Imagine yourself in a small community hospital standing at the bedside of a tiny preemie waiting for the neonatal transport team to return your call for help.

With one eye shifting between the clock and the oximeter, you have the other one looking out the window hoping that the predicted snow and freezing rain will hold out for another hour. You have done everything you can do, but clearly it’s not going to be enough to rescue this little person who had the misfortune of exiting the birth canal several months too early.

You have been able to insert an umbilical vein catheter and miraculously have threaded an endotracheal tube into a trachea that looked no bigger than a piece of spaghetti, or maybe you have failed and the nurses are taking turns bagging. The transport team returns your call for help and with apologies reports that they are tied up with a similar scenario further south; they predict that it may be an hour and a half before they will be able to get back to their hospital, which is a half hour down the road from you.

They suggest some things that you have already done. Should you wait for more skilled hands and their equipment or transport the patient yourself and get on the road before it becomes a skating rink? There is an antique transport isolette gathering dust in the storage room down the hall, and the local fire department ambulance crew with whom you are on a first-name basis is always ready to help. Is it time to gather the troops and tell them, “Let’s roll!” ?

If you have ever lived through a similar scenario, you may find a recent study interesting (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163[9]:681-90). What these investigators found was that for adults who had suffered major trauma, stroke, respiratory failure, and acute myocardial infarction, those who were transported by crews with basic life support (BLS) skills had significantly better long-term survival and neurologic outcomes than did those victims transported by crews with advanced life support (ALS) skills.

In the flurry of comments that circulated following the release of the study were a few questions about the methodology, but most commentators were searching for an explanation. Was critical time lost by the ALS crews doing stuff when the better course of action would have been to get the ambulance rolling to the hospital and more definitive care? Does the temptation to do things because you can do them sometimes cloud the decision-making process?

Although I have lived the scenario I described, it is less likely to happen now. Backup teams from other institutions may be activated. The teams are so well equipped and trained that the gaps between their capabilities and the neonatal intensive care unit have narrowed, but there is no question that they remain and are significant.

The other thing that hasn’t changed is the weather here in Maine. While we have beautiful summers that prompt us to put “Vacationland” on our license plates, our winters are a challenge. In addition to the patient’s condition and the availability of resources, the decision of whether to invest time in stabilization or get moving toward the referral center also must include the risk to the patient and staff who will be traveling on weather-threatened roads.

On the other hand, we can’t ignore the elephant that occasionally finds its way into the room when decisions are made about how thoroughly a critically ill patient is stabilized and how speedily he is transferred. And, that ponderous pachyderm is the hot potato factor and sometimes answers to its acronym, NIMBY (“not in my back yard”). You know as well as I do that despite the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) regulations, there are cases when a patient is hustled out the door without being appropriately stabilized primarily to avoid having that patient die in the referring hospital. We must continue to ask ourselves if we have done everything that we can do to stabilize the patient before we say, “Let’s roll!”

William G. Wilkoff, M.D., practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Imagine yourself in a small community hospital standing at the bedside of a tiny preemie waiting for the neonatal transport team to return your call for help.

With one eye shifting between the clock and the oximeter, you have the other one looking out the window hoping that the predicted snow and freezing rain will hold out for another hour. You have done everything you can do, but clearly it’s not going to be enough to rescue this little person who had the misfortune of exiting the birth canal several months too early.

You have been able to insert an umbilical vein catheter and miraculously have threaded an endotracheal tube into a trachea that looked no bigger than a piece of spaghetti, or maybe you have failed and the nurses are taking turns bagging. The transport team returns your call for help and with apologies reports that they are tied up with a similar scenario further south; they predict that it may be an hour and a half before they will be able to get back to their hospital, which is a half hour down the road from you.

They suggest some things that you have already done. Should you wait for more skilled hands and their equipment or transport the patient yourself and get on the road before it becomes a skating rink? There is an antique transport isolette gathering dust in the storage room down the hall, and the local fire department ambulance crew with whom you are on a first-name basis is always ready to help. Is it time to gather the troops and tell them, “Let’s roll!” ?

If you have ever lived through a similar scenario, you may find a recent study interesting (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163[9]:681-90). What these investigators found was that for adults who had suffered major trauma, stroke, respiratory failure, and acute myocardial infarction, those who were transported by crews with basic life support (BLS) skills had significantly better long-term survival and neurologic outcomes than did those victims transported by crews with advanced life support (ALS) skills.

In the flurry of comments that circulated following the release of the study were a few questions about the methodology, but most commentators were searching for an explanation. Was critical time lost by the ALS crews doing stuff when the better course of action would have been to get the ambulance rolling to the hospital and more definitive care? Does the temptation to do things because you can do them sometimes cloud the decision-making process?

Although I have lived the scenario I described, it is less likely to happen now. Backup teams from other institutions may be activated. The teams are so well equipped and trained that the gaps between their capabilities and the neonatal intensive care unit have narrowed, but there is no question that they remain and are significant.

The other thing that hasn’t changed is the weather here in Maine. While we have beautiful summers that prompt us to put “Vacationland” on our license plates, our winters are a challenge. In addition to the patient’s condition and the availability of resources, the decision of whether to invest time in stabilization or get moving toward the referral center also must include the risk to the patient and staff who will be traveling on weather-threatened roads.

On the other hand, we can’t ignore the elephant that occasionally finds its way into the room when decisions are made about how thoroughly a critically ill patient is stabilized and how speedily he is transferred. And, that ponderous pachyderm is the hot potato factor and sometimes answers to its acronym, NIMBY (“not in my back yard”). You know as well as I do that despite the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) regulations, there are cases when a patient is hustled out the door without being appropriately stabilized primarily to avoid having that patient die in the referring hospital. We must continue to ask ourselves if we have done everything that we can do to stabilize the patient before we say, “Let’s roll!”

William G. Wilkoff, M.D., practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Rising death rates of white midlife Americans

Princeton University Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Anne Case, Ph.D., and 2015 Nobel Prize winner in economics Angus Deaton, Ph.D., recently made headlines with an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that showed a remarkable anomaly in global death rates.

The steady decline in death rates seen across the world for age-specific cohorts held true in the United States with one exception: White men and women aged 45-54 years and only in the period of 1999 to 2013. The rising death rates in this cohort were concentrated most intensely among those with less than a high school education and among men. This finding was not seen in cohorts from other countries or in this age group in the United States before 1999.

Many explanations have been given for this focused finding, from income inequality to the stubbornly slow recovery from the recent economic recession. But none of these speculations explains why the upturn in death rates was not seen among Hispanics or blacks in this age cohort – or why it was not seen in the decade before 2000.

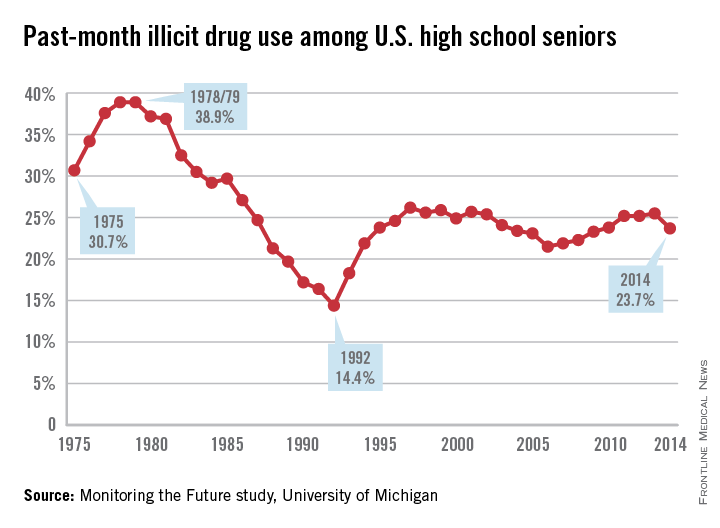

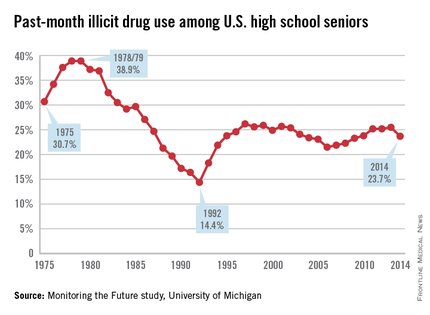

Several clues provide insight. The first is that the increase in deaths was mostly the result of rising rates of drug overdose, suicide, and chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver. In 1978, the peak of the modern drug epidemic, this cohort was aged 10-24 years. This sharp drug abuse epidemic was distinctly American and more prevalent among white males than among white females or other males. The annual Monitoring the Future study, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has chronicled the patterns of substance use for American 12th graders from 1975 to the present. It provides a snapshot of the patterns of adolescent drug use in this cohort. During the peak of the national drug epidemic, this cohort was at the most vulnerable age for starting drug use.

The second clue to this puzzle is that in recent decades, there has been a breakdown in the health and social capital of whites having lower educations, as author and political scientist author Charles Murray, Ph.D., recounted in a recent book (“Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010,” [New York: Crown Forum, 2012]). This might have resulted in an increased vulnerability in midlife within this cohort to adverse health effects and in less resiliency in mitigating those effects.

A third relevant clue is that the adverse health effects of adolescent drug use are not limited to adolescence. Substance use disorders most commonly begin in the teenage years (Nature. 2015 Jun;[522]:S46-7). Early drug use is a predictor of lifelong serious co-occurring health problems, including addiction to alcohol and other drugs.

Thus, in addition to the explanations already put forth in response to the Case-Deaton findings, an additional factor has significance. The leading edge of the Baby Boom generation not only sparked the modern drug abuse epidemic in their teen years but also carries with it a substantially heightened lifelong health risk for overdose death, suicide, and chronic liver disease.

This finding is significant not only for the health of this aging cohort but also for young people today. The delayed consequences of adolescent drug and alcohol use provide another good reason to refocus public health efforts to encourage youth to grow up without using alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs.

Dr. DuPont is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, Rockville, Md., and was the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1973-1978).

Princeton University Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Anne Case, Ph.D., and 2015 Nobel Prize winner in economics Angus Deaton, Ph.D., recently made headlines with an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that showed a remarkable anomaly in global death rates.

The steady decline in death rates seen across the world for age-specific cohorts held true in the United States with one exception: White men and women aged 45-54 years and only in the period of 1999 to 2013. The rising death rates in this cohort were concentrated most intensely among those with less than a high school education and among men. This finding was not seen in cohorts from other countries or in this age group in the United States before 1999.

Many explanations have been given for this focused finding, from income inequality to the stubbornly slow recovery from the recent economic recession. But none of these speculations explains why the upturn in death rates was not seen among Hispanics or blacks in this age cohort – or why it was not seen in the decade before 2000.

Several clues provide insight. The first is that the increase in deaths was mostly the result of rising rates of drug overdose, suicide, and chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver. In 1978, the peak of the modern drug epidemic, this cohort was aged 10-24 years. This sharp drug abuse epidemic was distinctly American and more prevalent among white males than among white females or other males. The annual Monitoring the Future study, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has chronicled the patterns of substance use for American 12th graders from 1975 to the present. It provides a snapshot of the patterns of adolescent drug use in this cohort. During the peak of the national drug epidemic, this cohort was at the most vulnerable age for starting drug use.

The second clue to this puzzle is that in recent decades, there has been a breakdown in the health and social capital of whites having lower educations, as author and political scientist author Charles Murray, Ph.D., recounted in a recent book (“Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010,” [New York: Crown Forum, 2012]). This might have resulted in an increased vulnerability in midlife within this cohort to adverse health effects and in less resiliency in mitigating those effects.

A third relevant clue is that the adverse health effects of adolescent drug use are not limited to adolescence. Substance use disorders most commonly begin in the teenage years (Nature. 2015 Jun;[522]:S46-7). Early drug use is a predictor of lifelong serious co-occurring health problems, including addiction to alcohol and other drugs.

Thus, in addition to the explanations already put forth in response to the Case-Deaton findings, an additional factor has significance. The leading edge of the Baby Boom generation not only sparked the modern drug abuse epidemic in their teen years but also carries with it a substantially heightened lifelong health risk for overdose death, suicide, and chronic liver disease.

This finding is significant not only for the health of this aging cohort but also for young people today. The delayed consequences of adolescent drug and alcohol use provide another good reason to refocus public health efforts to encourage youth to grow up without using alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs.

Dr. DuPont is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, Rockville, Md., and was the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1973-1978).

Princeton University Professor of Economics and Public Affairs Anne Case, Ph.D., and 2015 Nobel Prize winner in economics Angus Deaton, Ph.D., recently made headlines with an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that showed a remarkable anomaly in global death rates.

The steady decline in death rates seen across the world for age-specific cohorts held true in the United States with one exception: White men and women aged 45-54 years and only in the period of 1999 to 2013. The rising death rates in this cohort were concentrated most intensely among those with less than a high school education and among men. This finding was not seen in cohorts from other countries or in this age group in the United States before 1999.

Many explanations have been given for this focused finding, from income inequality to the stubbornly slow recovery from the recent economic recession. But none of these speculations explains why the upturn in death rates was not seen among Hispanics or blacks in this age cohort – or why it was not seen in the decade before 2000.

Several clues provide insight. The first is that the increase in deaths was mostly the result of rising rates of drug overdose, suicide, and chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver. In 1978, the peak of the modern drug epidemic, this cohort was aged 10-24 years. This sharp drug abuse epidemic was distinctly American and more prevalent among white males than among white females or other males. The annual Monitoring the Future study, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, has chronicled the patterns of substance use for American 12th graders from 1975 to the present. It provides a snapshot of the patterns of adolescent drug use in this cohort. During the peak of the national drug epidemic, this cohort was at the most vulnerable age for starting drug use.

The second clue to this puzzle is that in recent decades, there has been a breakdown in the health and social capital of whites having lower educations, as author and political scientist author Charles Murray, Ph.D., recounted in a recent book (“Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010,” [New York: Crown Forum, 2012]). This might have resulted in an increased vulnerability in midlife within this cohort to adverse health effects and in less resiliency in mitigating those effects.

A third relevant clue is that the adverse health effects of adolescent drug use are not limited to adolescence. Substance use disorders most commonly begin in the teenage years (Nature. 2015 Jun;[522]:S46-7). Early drug use is a predictor of lifelong serious co-occurring health problems, including addiction to alcohol and other drugs.

Thus, in addition to the explanations already put forth in response to the Case-Deaton findings, an additional factor has significance. The leading edge of the Baby Boom generation not only sparked the modern drug abuse epidemic in their teen years but also carries with it a substantially heightened lifelong health risk for overdose death, suicide, and chronic liver disease.

This finding is significant not only for the health of this aging cohort but also for young people today. The delayed consequences of adolescent drug and alcohol use provide another good reason to refocus public health efforts to encourage youth to grow up without using alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs.

Dr. DuPont is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health, Rockville, Md., and was the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1973-1978).

Defying Gravity

Last week, I fell in the driveway. I was taking the trash to the curb when I tripped and fell into the large blue recycling bin. Although it was 6 AM, I jumped up and looked around, horrified that someone may have seen my episode of gracelessness. I did bump my head and spent the rest of the day feeling stupid while rubbing the sore spot.

This incident, though more ego-bruising than anything, really conveyed to me the concerns of falling—not only for the elderly, but for all of us. So, not to be confused with the signature song from the musical Wicked sung by Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) who has a desire to live without limits, my editorial this month discusses sobering limits in our everyday lives. And it does implicate gravity!

According to the National Council on Aging, about 1 in 3 adults ages 65 and older fall each year.1 Unintentional falls are the leading cause of nonfatal and fatal injuries (eg, hip fractures, head trauma) for older adults and result in about 57 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year.1,2 In 2013, more than 25,000 elderly individuals in the United States died from unintentional fall injuries.3

Who falls? Who doesn’t? But data indicate that among community-dwelling individuals older than 65, women fall more frequently than their male counterparts.4 But while injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both sexes, regardless of race, after age 85, men in this age-group are more likely to die from a fall than are women.5

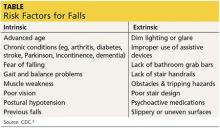

There are many risk factors that contribute to falling (see the table6), with gait and balance problems reported as the most significant contributor to falls among older adults.7 In addition, researchers report an increase in diseases linked to falls: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and Parkinson disease. In many cases, the medication used to treat the disease increases the risk for falling.8 It behooves every clinician to assess for and address any modifiable risk factors at each patient visit; one valuable resource is the CDC’s Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.9

The issue of falling must be addressed on a larger scale, though. In response to the sobering statistics about falls, retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes are trying to balance safety with their residents’ desire to live as they choose. They are hiring architects, interior designers, and engineers to find better ways to create safe living spaces, including installing floor lighting (similar to that on airplanes) that automatically illuminates a pathway to the bathroom when a resident gets out of bed.10

Continue for fall prevention in the community >>

But what about fall prevention in the community? A cost-benefit analysis revealed that community-based fall interventions are feasible and effective and provide a positive return on investment—no small consideration, given our current circumstances: Every 13 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency department for a fall, and every 29 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall-related injury.4,5 These estimates will likely rise as the population ages. The financial repercussions of falls and resultant morbidity and mortality may exceed $59 billion by 2020, according to the National Council on Aging.1 However, a 2013 report to Congress by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services indicated that older adults’ participation in a falls prevention program has resulted in reduced health care costs.11

Over the decades, many different approaches have been used to enhance older adults’ participation in such programs. I am proud to report that my university is among the many organizations to address this issue. A.T. Still University of Health Sciences (ATSU) was recently awarded a $95,000 grant by the Baptist Hospitals and Health Systems (BHHS) to support the university’s Fall Prevention Outreach program—the largest university-based fall-prevention initiative in the country.12

Since the program began in 2008, more than 2,000 Arizonans have completed the eight-week curriculum, which gives older adults the tools they need to prevent falls and manage the often-paralyzing fear of falling that comes with growing older. Since injuries sustained from falls are the leading cause of accidental injury deaths in Arizonans ages 65 and older, according to the state’s Department of Health Services, this program gives us an opportunity to have a direct impact on our community.

ATSU uses A Matter of Balance, a nationally recognized fall-prevention curriculum developed by Boston University.13 After receiving special training, teams of ATSU physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, athletic training, and audiology students offer the curriculum, at no cost, to older citizens at 41 community sites in the Greater Phoenix area. Collaborations with partners ranging from local municipalities to assisted-living communities make the program possible.

Part of the BHHS grant funded the certification of 15 master trainers who teach the two-day A Matter of Balance curriculum to the ATSU students and the community volunteers who will, in turn, lead the sessions. The grant also funded the expansion of the program to an additional 24 sites, for a total of 65.12

For those who wish to identify appropriate evidence-based fall prevention programs in their community, the CDC developed a new guide, Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs.14 This “how-to” outlines how community-based organizations initiate and maintain effective programs. It focuses on implementation of fall prevention programs and offers strategies on program planning, development, implementation, and evaluation. This resource provides a solid starting point for those seeking to address this increasingly prevalent issue.

How do you investigate the risk for falls with your patients? I would be interested in hearing from you what resources are available in your community. You can contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Cameron K, Schneider E, Childress D, Gilchrist C. (2015). National Council on Aging Falls Free® National Action Plan (2015). www.ncoa.org/FallsFreeNAP. Accessed November 5, 2015.

2. CDC. Important Facts about Falls. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics (WISQARSTM). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed August 15, 2013.

4. Carande-Kulis I, Stevens JA, Florence CS, et al. Special Report from the CDC: a cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res. 2015;52:65-70.

5. CDC. WISQARS leading causes of nonfatal injury reports: 2006. Accessed November 13, 2006.

6. CDC. Risk factors for falls. http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/risk_factors_for_falls-a.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2015.

7. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

8. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61.

9. CDC. Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/Falls/compendium.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

10. Hafner K. Bracing for the falls of an aging nation. New York Times. November 2, 2014. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/11/03/health/bracing-for-the-falls-of-an-aging-nation.html?emc=edit_na_20141102&_r=0. Accessed November 4, 2015.

11. Houry D. The White House Conference on Aging and keeping older adults STEADI and free from falls. www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/blog/post/the-white-house-conference-on-aging-and-keeping-older-adults-steadi-and-free-from-falls1.aspx. Accessed November 4, 2015.

12. Scott K. ATSU receives $95,000 grant to expand Fall Prevention Outreach program [news release]. October 1, 2015. http://news.atsu.edu/index.php/archives/category/arizona-campus. Accessed November 4, 2015.

13. MaineHealth Partnership for Healthy Aging. A Matter of Balance: Managing Concerns About Falls. www.mainehealth.org/AMatterofBalanceFrequentlyAskedQuestions#mob. Accessed November 4, 2015.

14. CDC. Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs. www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafetyFalls/community_preventfalls.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

Last week, I fell in the driveway. I was taking the trash to the curb when I tripped and fell into the large blue recycling bin. Although it was 6 AM, I jumped up and looked around, horrified that someone may have seen my episode of gracelessness. I did bump my head and spent the rest of the day feeling stupid while rubbing the sore spot.

This incident, though more ego-bruising than anything, really conveyed to me the concerns of falling—not only for the elderly, but for all of us. So, not to be confused with the signature song from the musical Wicked sung by Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) who has a desire to live without limits, my editorial this month discusses sobering limits in our everyday lives. And it does implicate gravity!

According to the National Council on Aging, about 1 in 3 adults ages 65 and older fall each year.1 Unintentional falls are the leading cause of nonfatal and fatal injuries (eg, hip fractures, head trauma) for older adults and result in about 57 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year.1,2 In 2013, more than 25,000 elderly individuals in the United States died from unintentional fall injuries.3

Who falls? Who doesn’t? But data indicate that among community-dwelling individuals older than 65, women fall more frequently than their male counterparts.4 But while injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both sexes, regardless of race, after age 85, men in this age-group are more likely to die from a fall than are women.5

There are many risk factors that contribute to falling (see the table6), with gait and balance problems reported as the most significant contributor to falls among older adults.7 In addition, researchers report an increase in diseases linked to falls: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and Parkinson disease. In many cases, the medication used to treat the disease increases the risk for falling.8 It behooves every clinician to assess for and address any modifiable risk factors at each patient visit; one valuable resource is the CDC’s Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.9

The issue of falling must be addressed on a larger scale, though. In response to the sobering statistics about falls, retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes are trying to balance safety with their residents’ desire to live as they choose. They are hiring architects, interior designers, and engineers to find better ways to create safe living spaces, including installing floor lighting (similar to that on airplanes) that automatically illuminates a pathway to the bathroom when a resident gets out of bed.10

Continue for fall prevention in the community >>

But what about fall prevention in the community? A cost-benefit analysis revealed that community-based fall interventions are feasible and effective and provide a positive return on investment—no small consideration, given our current circumstances: Every 13 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency department for a fall, and every 29 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall-related injury.4,5 These estimates will likely rise as the population ages. The financial repercussions of falls and resultant morbidity and mortality may exceed $59 billion by 2020, according to the National Council on Aging.1 However, a 2013 report to Congress by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services indicated that older adults’ participation in a falls prevention program has resulted in reduced health care costs.11

Over the decades, many different approaches have been used to enhance older adults’ participation in such programs. I am proud to report that my university is among the many organizations to address this issue. A.T. Still University of Health Sciences (ATSU) was recently awarded a $95,000 grant by the Baptist Hospitals and Health Systems (BHHS) to support the university’s Fall Prevention Outreach program—the largest university-based fall-prevention initiative in the country.12

Since the program began in 2008, more than 2,000 Arizonans have completed the eight-week curriculum, which gives older adults the tools they need to prevent falls and manage the often-paralyzing fear of falling that comes with growing older. Since injuries sustained from falls are the leading cause of accidental injury deaths in Arizonans ages 65 and older, according to the state’s Department of Health Services, this program gives us an opportunity to have a direct impact on our community.

ATSU uses A Matter of Balance, a nationally recognized fall-prevention curriculum developed by Boston University.13 After receiving special training, teams of ATSU physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, athletic training, and audiology students offer the curriculum, at no cost, to older citizens at 41 community sites in the Greater Phoenix area. Collaborations with partners ranging from local municipalities to assisted-living communities make the program possible.

Part of the BHHS grant funded the certification of 15 master trainers who teach the two-day A Matter of Balance curriculum to the ATSU students and the community volunteers who will, in turn, lead the sessions. The grant also funded the expansion of the program to an additional 24 sites, for a total of 65.12

For those who wish to identify appropriate evidence-based fall prevention programs in their community, the CDC developed a new guide, Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs.14 This “how-to” outlines how community-based organizations initiate and maintain effective programs. It focuses on implementation of fall prevention programs and offers strategies on program planning, development, implementation, and evaluation. This resource provides a solid starting point for those seeking to address this increasingly prevalent issue.

How do you investigate the risk for falls with your patients? I would be interested in hearing from you what resources are available in your community. You can contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Cameron K, Schneider E, Childress D, Gilchrist C. (2015). National Council on Aging Falls Free® National Action Plan (2015). www.ncoa.org/FallsFreeNAP. Accessed November 5, 2015.

2. CDC. Important Facts about Falls. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics (WISQARSTM). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed August 15, 2013.

4. Carande-Kulis I, Stevens JA, Florence CS, et al. Special Report from the CDC: a cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res. 2015;52:65-70.

5. CDC. WISQARS leading causes of nonfatal injury reports: 2006. Accessed November 13, 2006.

6. CDC. Risk factors for falls. http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/risk_factors_for_falls-a.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2015.

7. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

8. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61.