User login

Getting past bad drug outcomes

In my first year of fellowship, I met a delightful old man who had temporal arteritis. We naturally treated him with steroids, but he consequently suffered a vertebral fracture. He passed away soon after that from pneumonia that was probably aggravated by his inability to breathe deeply and cough appropriately.

An elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed with lymphoma. For want of something to blame, his children blamed it on the methotrexate.

A woman with lupus nephritis got pregnant while on mycophenolate despite being on contraception. Her baby was born with malformed ears and eyes, and by all accounts will probably be deaf and blind.

We have been gifted with this mind-blowing ability to make our patients’ lives much better. That sense of accomplishment can be intoxicating. After all, how many of your polymyalgia rheumatica patients worship you because you made the diagnosis and made them 100% better by putting them on prednisone? Yet we forget that although bad things rarely happen, that does not mean that they won’t happen.

In a beautiful book called "Where’d You Go, Bernadette?" the husband of the title character says that the brain is a discounting mechanism: "Let’s say you get a crack in your windshield and you’re really upset. Oh no, my windshield, it’s ruined, I can hardly see out of it, this is a tragedy! But you don’t have enough money to fix it, so you drive with it. In a month, someone asks you what happened to your windshield, and you say, What do you mean? Because your brain has discounted it. ... It’s for survival. You need to be prepared for novel experiences because often they signal danger."

The book is about an artist who we are led to believe has completed her downward spiral, going from genius to wacko. In the above passage, the artist’s husband is explaining to their daughter why they loved their family home so much, despite its state of extreme disrepair. They loved the house so much that they couldn’t see that it was a safety hazard.

As a fresh graduate I insisted on weaning everyone off prednisone, terrified of the potential side effects. Five years later and with the benefit of the collected wisdom of hundreds of rheumatologists before me, I have accepted that some people need a low dose of steroid to keep their disease quiet. I have used this and other, more toxic drugs to such great effects – taking for granted their ability to make people better – that I forget sometimes that they can cause serious problems.

Bad outcomes can and do happen in spite of our best intentions. In my case, my default is to blame myself. In my more melodramatic moments, I wonder if I deserve to be a doctor. But when I am done feeling angry or sad, or, frankly, feeling sorry for myself, then I need that discounting mechanism to kick in, to remind myself that this is one bad outcome out of many good outcomes. There are things beyond my control, and I cannot let a bad outcome keep me from doing the good work that I am still able to do.

There is a scene from the TV series "The West Wing" where the president asks one of his staffers if he thought the president was being kept from doing a great job because his demons were "shouting down the better angels" in his brain. Thankfully, my brain’s discounting mechanism helps keep the demons at bay.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

In my first year of fellowship, I met a delightful old man who had temporal arteritis. We naturally treated him with steroids, but he consequently suffered a vertebral fracture. He passed away soon after that from pneumonia that was probably aggravated by his inability to breathe deeply and cough appropriately.

An elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed with lymphoma. For want of something to blame, his children blamed it on the methotrexate.

A woman with lupus nephritis got pregnant while on mycophenolate despite being on contraception. Her baby was born with malformed ears and eyes, and by all accounts will probably be deaf and blind.

We have been gifted with this mind-blowing ability to make our patients’ lives much better. That sense of accomplishment can be intoxicating. After all, how many of your polymyalgia rheumatica patients worship you because you made the diagnosis and made them 100% better by putting them on prednisone? Yet we forget that although bad things rarely happen, that does not mean that they won’t happen.

In a beautiful book called "Where’d You Go, Bernadette?" the husband of the title character says that the brain is a discounting mechanism: "Let’s say you get a crack in your windshield and you’re really upset. Oh no, my windshield, it’s ruined, I can hardly see out of it, this is a tragedy! But you don’t have enough money to fix it, so you drive with it. In a month, someone asks you what happened to your windshield, and you say, What do you mean? Because your brain has discounted it. ... It’s for survival. You need to be prepared for novel experiences because often they signal danger."

The book is about an artist who we are led to believe has completed her downward spiral, going from genius to wacko. In the above passage, the artist’s husband is explaining to their daughter why they loved their family home so much, despite its state of extreme disrepair. They loved the house so much that they couldn’t see that it was a safety hazard.

As a fresh graduate I insisted on weaning everyone off prednisone, terrified of the potential side effects. Five years later and with the benefit of the collected wisdom of hundreds of rheumatologists before me, I have accepted that some people need a low dose of steroid to keep their disease quiet. I have used this and other, more toxic drugs to such great effects – taking for granted their ability to make people better – that I forget sometimes that they can cause serious problems.

Bad outcomes can and do happen in spite of our best intentions. In my case, my default is to blame myself. In my more melodramatic moments, I wonder if I deserve to be a doctor. But when I am done feeling angry or sad, or, frankly, feeling sorry for myself, then I need that discounting mechanism to kick in, to remind myself that this is one bad outcome out of many good outcomes. There are things beyond my control, and I cannot let a bad outcome keep me from doing the good work that I am still able to do.

There is a scene from the TV series "The West Wing" where the president asks one of his staffers if he thought the president was being kept from doing a great job because his demons were "shouting down the better angels" in his brain. Thankfully, my brain’s discounting mechanism helps keep the demons at bay.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

In my first year of fellowship, I met a delightful old man who had temporal arteritis. We naturally treated him with steroids, but he consequently suffered a vertebral fracture. He passed away soon after that from pneumonia that was probably aggravated by his inability to breathe deeply and cough appropriately.

An elderly patient with rheumatoid arthritis was diagnosed with lymphoma. For want of something to blame, his children blamed it on the methotrexate.

A woman with lupus nephritis got pregnant while on mycophenolate despite being on contraception. Her baby was born with malformed ears and eyes, and by all accounts will probably be deaf and blind.

We have been gifted with this mind-blowing ability to make our patients’ lives much better. That sense of accomplishment can be intoxicating. After all, how many of your polymyalgia rheumatica patients worship you because you made the diagnosis and made them 100% better by putting them on prednisone? Yet we forget that although bad things rarely happen, that does not mean that they won’t happen.

In a beautiful book called "Where’d You Go, Bernadette?" the husband of the title character says that the brain is a discounting mechanism: "Let’s say you get a crack in your windshield and you’re really upset. Oh no, my windshield, it’s ruined, I can hardly see out of it, this is a tragedy! But you don’t have enough money to fix it, so you drive with it. In a month, someone asks you what happened to your windshield, and you say, What do you mean? Because your brain has discounted it. ... It’s for survival. You need to be prepared for novel experiences because often they signal danger."

The book is about an artist who we are led to believe has completed her downward spiral, going from genius to wacko. In the above passage, the artist’s husband is explaining to their daughter why they loved their family home so much, despite its state of extreme disrepair. They loved the house so much that they couldn’t see that it was a safety hazard.

As a fresh graduate I insisted on weaning everyone off prednisone, terrified of the potential side effects. Five years later and with the benefit of the collected wisdom of hundreds of rheumatologists before me, I have accepted that some people need a low dose of steroid to keep their disease quiet. I have used this and other, more toxic drugs to such great effects – taking for granted their ability to make people better – that I forget sometimes that they can cause serious problems.

Bad outcomes can and do happen in spite of our best intentions. In my case, my default is to blame myself. In my more melodramatic moments, I wonder if I deserve to be a doctor. But when I am done feeling angry or sad, or, frankly, feeling sorry for myself, then I need that discounting mechanism to kick in, to remind myself that this is one bad outcome out of many good outcomes. There are things beyond my control, and I cannot let a bad outcome keep me from doing the good work that I am still able to do.

There is a scene from the TV series "The West Wing" where the president asks one of his staffers if he thought the president was being kept from doing a great job because his demons were "shouting down the better angels" in his brain. Thankfully, my brain’s discounting mechanism helps keep the demons at bay.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

Firing your patient

How often do you fire patients? I do it here and there, maybe a few times a year, but certainly not as often as patients fire me.

Contrary to popular belief, I don’t get some sort of perverse thrill out of it. I am maybe relieved, knowing that I’m (hopefully) done with a difficult relationship. But it’s a pain, always requiring a trip to the post office to send the registered letter. There’s also the fear that they’ll report me to the board for it, and I’ll have to defend my actions. And I certainly can’t guard against the one-sided Yelp reviews.

What tips you over the edge? I consider myself pretty tolerant. In long-standing patients, I’ll generally let the occasional no-show slide. For drug abusers, I’m actually willing to continue with many of them, but will let them know that I’m not going to give them controlled substances anymore. Most of them leave at that point anyway.

I have zero tolerance for malicious behavior. Abuse my staff, and you’re out of here. I’m more willing to put up with someone who’s nasty to me than one who treats my staff the same way.

What other things do I fire them for? Occasionally noncompliance, especially if it’s putting their own safety in danger. Only once have I fired someone for refusing to have tests done. That was after, literally, 5 years of him repeatedly showing up annually to ask me to order them for his symptoms, then never following through and showing up a year later to start over again. At some point, my patience for that type of thing runs out, and I consider myself fairly patient.

Like most doctors, I’ve had more patients fire me than I’ve fired patients. For most, you don’t realize they’re gone. They just never come back. Occasionally, you get a release from another doctor, but more often you don’t.

Rarely, someone sends a nasty letter telling me why they went elsewhere and what they think of my medical skills/fashion sense/office décor ... whatever. The first time I got one of those, it hurt. Nowadays, I just don’t care.

Part of growing up as a doctor is realizing you’ll never make everyone happy or be able to help them all. Trying to do so will only lessen your sanity, so it’s a message best learned early.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How often do you fire patients? I do it here and there, maybe a few times a year, but certainly not as often as patients fire me.

Contrary to popular belief, I don’t get some sort of perverse thrill out of it. I am maybe relieved, knowing that I’m (hopefully) done with a difficult relationship. But it’s a pain, always requiring a trip to the post office to send the registered letter. There’s also the fear that they’ll report me to the board for it, and I’ll have to defend my actions. And I certainly can’t guard against the one-sided Yelp reviews.

What tips you over the edge? I consider myself pretty tolerant. In long-standing patients, I’ll generally let the occasional no-show slide. For drug abusers, I’m actually willing to continue with many of them, but will let them know that I’m not going to give them controlled substances anymore. Most of them leave at that point anyway.

I have zero tolerance for malicious behavior. Abuse my staff, and you’re out of here. I’m more willing to put up with someone who’s nasty to me than one who treats my staff the same way.

What other things do I fire them for? Occasionally noncompliance, especially if it’s putting their own safety in danger. Only once have I fired someone for refusing to have tests done. That was after, literally, 5 years of him repeatedly showing up annually to ask me to order them for his symptoms, then never following through and showing up a year later to start over again. At some point, my patience for that type of thing runs out, and I consider myself fairly patient.

Like most doctors, I’ve had more patients fire me than I’ve fired patients. For most, you don’t realize they’re gone. They just never come back. Occasionally, you get a release from another doctor, but more often you don’t.

Rarely, someone sends a nasty letter telling me why they went elsewhere and what they think of my medical skills/fashion sense/office décor ... whatever. The first time I got one of those, it hurt. Nowadays, I just don’t care.

Part of growing up as a doctor is realizing you’ll never make everyone happy or be able to help them all. Trying to do so will only lessen your sanity, so it’s a message best learned early.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How often do you fire patients? I do it here and there, maybe a few times a year, but certainly not as often as patients fire me.

Contrary to popular belief, I don’t get some sort of perverse thrill out of it. I am maybe relieved, knowing that I’m (hopefully) done with a difficult relationship. But it’s a pain, always requiring a trip to the post office to send the registered letter. There’s also the fear that they’ll report me to the board for it, and I’ll have to defend my actions. And I certainly can’t guard against the one-sided Yelp reviews.

What tips you over the edge? I consider myself pretty tolerant. In long-standing patients, I’ll generally let the occasional no-show slide. For drug abusers, I’m actually willing to continue with many of them, but will let them know that I’m not going to give them controlled substances anymore. Most of them leave at that point anyway.

I have zero tolerance for malicious behavior. Abuse my staff, and you’re out of here. I’m more willing to put up with someone who’s nasty to me than one who treats my staff the same way.

What other things do I fire them for? Occasionally noncompliance, especially if it’s putting their own safety in danger. Only once have I fired someone for refusing to have tests done. That was after, literally, 5 years of him repeatedly showing up annually to ask me to order them for his symptoms, then never following through and showing up a year later to start over again. At some point, my patience for that type of thing runs out, and I consider myself fairly patient.

Like most doctors, I’ve had more patients fire me than I’ve fired patients. For most, you don’t realize they’re gone. They just never come back. Occasionally, you get a release from another doctor, but more often you don’t.

Rarely, someone sends a nasty letter telling me why they went elsewhere and what they think of my medical skills/fashion sense/office décor ... whatever. The first time I got one of those, it hurt. Nowadays, I just don’t care.

Part of growing up as a doctor is realizing you’ll never make everyone happy or be able to help them all. Trying to do so will only lessen your sanity, so it’s a message best learned early.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation

Supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids – or omega-3 fatty acids – during pregnancy is an important topic because of unproven claims that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) improve fetal brain and eye development if taken during pregnancy, resulting in unnecessary expense for many women who buy these products. In Canada, there are prenatal vitamins available that contain omega-3 fatty acids with a statement that the product "helps support cognitive health and/or brain function" or that omega-3 fatty acids "support "healthy fetal brain and eye development." These are misleading, inappropriate statements, considering that there is no compelling evidence to support these claims.

Claims about the benefits of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy, which have circulated for about a decade, originate from studies that show that when PUFAs are restricted during pregnancy, fetal brain development can be adversely affected, particularly in animals. Other data include several human studies that have linked high cognitive scores to a high seafood content of the maternal diet. The highest levels of PUFAs are measured in the retina, which is part of the visual acuity claim.

My colleagues and I addressed the uncertainties about the benefits of PUFA supplementation in a systematic review of nine randomized controlled trials comparing visual and neurobehavioral outcomes in infants whose mothers received PUFA supplements during gestation with control women who received placebos. Three studies evaluated retinal development and six evaluated neurodevelopment; most ended the supplement at delivery, and evaluations were conducted during the first year, or up to age 2.5, 4, and 7 years in different studies.

Overall, there was no evidence of a beneficial effect of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy on neurodevelopment (IQ, language behaviors) or on visual acuity. As we concluded, there were "very limited, if any" benefits identified, and in the studies with statistically significant differences between the two groups, "the differences were small and of little potential clinical importance" (Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012 [doi:10.1155/2012/591531]).

A study published in May 2014 also found no beneficial effect of prenatal supplementation with 800 mg/day of omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on neurodevelopmental outcomes in children followed to age 4 years, and the authors concluded that the data "do not support prenatal DHA supplementation to enhance early childhood development." The randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated about 650 children at age 4 years, whose mothers had received the supplement or 333 who received placebo. The mean cognitive scores were not different between the two groups, and the proportion of children with delayed or advanced scores also did not differ between the two groups, nor did other objective assessments of cognition, language, and executive functioning (JAMA 2014;311:1802-4).

Based on the lack of evidence to date, there is no reason to add PUFAs to prenatal vitamins or recommend that women take a PUFA supplement during pregnancy.

The bottom line for clinicians/health care providers is that although the available evidence today has found no detrimental effects of even high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (up to 3.7 g/day), with the present state of knowledge, there is no evidence that prenatal supplementation with PUFAs improves brain development or acuity of vision in children. Instead of supplementation with PUFA during pregnancy, women should consume a diet with adequate PUFAs, with food that includes eggs and fish, with caution about the mercury content of fish.

Dr. Koren is professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program. He also holds the Ivey Chair in Molecular Toxicology at the department of medicine, University of Western Ontario, London. He had no disclosures relevant to this topic. E-mail him at [email protected].

Supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids – or omega-3 fatty acids – during pregnancy is an important topic because of unproven claims that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) improve fetal brain and eye development if taken during pregnancy, resulting in unnecessary expense for many women who buy these products. In Canada, there are prenatal vitamins available that contain omega-3 fatty acids with a statement that the product "helps support cognitive health and/or brain function" or that omega-3 fatty acids "support "healthy fetal brain and eye development." These are misleading, inappropriate statements, considering that there is no compelling evidence to support these claims.

Claims about the benefits of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy, which have circulated for about a decade, originate from studies that show that when PUFAs are restricted during pregnancy, fetal brain development can be adversely affected, particularly in animals. Other data include several human studies that have linked high cognitive scores to a high seafood content of the maternal diet. The highest levels of PUFAs are measured in the retina, which is part of the visual acuity claim.

My colleagues and I addressed the uncertainties about the benefits of PUFA supplementation in a systematic review of nine randomized controlled trials comparing visual and neurobehavioral outcomes in infants whose mothers received PUFA supplements during gestation with control women who received placebos. Three studies evaluated retinal development and six evaluated neurodevelopment; most ended the supplement at delivery, and evaluations were conducted during the first year, or up to age 2.5, 4, and 7 years in different studies.

Overall, there was no evidence of a beneficial effect of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy on neurodevelopment (IQ, language behaviors) or on visual acuity. As we concluded, there were "very limited, if any" benefits identified, and in the studies with statistically significant differences between the two groups, "the differences were small and of little potential clinical importance" (Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012 [doi:10.1155/2012/591531]).

A study published in May 2014 also found no beneficial effect of prenatal supplementation with 800 mg/day of omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on neurodevelopmental outcomes in children followed to age 4 years, and the authors concluded that the data "do not support prenatal DHA supplementation to enhance early childhood development." The randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated about 650 children at age 4 years, whose mothers had received the supplement or 333 who received placebo. The mean cognitive scores were not different between the two groups, and the proportion of children with delayed or advanced scores also did not differ between the two groups, nor did other objective assessments of cognition, language, and executive functioning (JAMA 2014;311:1802-4).

Based on the lack of evidence to date, there is no reason to add PUFAs to prenatal vitamins or recommend that women take a PUFA supplement during pregnancy.

The bottom line for clinicians/health care providers is that although the available evidence today has found no detrimental effects of even high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (up to 3.7 g/day), with the present state of knowledge, there is no evidence that prenatal supplementation with PUFAs improves brain development or acuity of vision in children. Instead of supplementation with PUFA during pregnancy, women should consume a diet with adequate PUFAs, with food that includes eggs and fish, with caution about the mercury content of fish.

Dr. Koren is professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program. He also holds the Ivey Chair in Molecular Toxicology at the department of medicine, University of Western Ontario, London. He had no disclosures relevant to this topic. E-mail him at [email protected].

Supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids – or omega-3 fatty acids – during pregnancy is an important topic because of unproven claims that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) improve fetal brain and eye development if taken during pregnancy, resulting in unnecessary expense for many women who buy these products. In Canada, there are prenatal vitamins available that contain omega-3 fatty acids with a statement that the product "helps support cognitive health and/or brain function" or that omega-3 fatty acids "support "healthy fetal brain and eye development." These are misleading, inappropriate statements, considering that there is no compelling evidence to support these claims.

Claims about the benefits of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy, which have circulated for about a decade, originate from studies that show that when PUFAs are restricted during pregnancy, fetal brain development can be adversely affected, particularly in animals. Other data include several human studies that have linked high cognitive scores to a high seafood content of the maternal diet. The highest levels of PUFAs are measured in the retina, which is part of the visual acuity claim.

My colleagues and I addressed the uncertainties about the benefits of PUFA supplementation in a systematic review of nine randomized controlled trials comparing visual and neurobehavioral outcomes in infants whose mothers received PUFA supplements during gestation with control women who received placebos. Three studies evaluated retinal development and six evaluated neurodevelopment; most ended the supplement at delivery, and evaluations were conducted during the first year, or up to age 2.5, 4, and 7 years in different studies.

Overall, there was no evidence of a beneficial effect of PUFA supplementation during pregnancy on neurodevelopment (IQ, language behaviors) or on visual acuity. As we concluded, there were "very limited, if any" benefits identified, and in the studies with statistically significant differences between the two groups, "the differences were small and of little potential clinical importance" (Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012 [doi:10.1155/2012/591531]).

A study published in May 2014 also found no beneficial effect of prenatal supplementation with 800 mg/day of omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on neurodevelopmental outcomes in children followed to age 4 years, and the authors concluded that the data "do not support prenatal DHA supplementation to enhance early childhood development." The randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated about 650 children at age 4 years, whose mothers had received the supplement or 333 who received placebo. The mean cognitive scores were not different between the two groups, and the proportion of children with delayed or advanced scores also did not differ between the two groups, nor did other objective assessments of cognition, language, and executive functioning (JAMA 2014;311:1802-4).

Based on the lack of evidence to date, there is no reason to add PUFAs to prenatal vitamins or recommend that women take a PUFA supplement during pregnancy.

The bottom line for clinicians/health care providers is that although the available evidence today has found no detrimental effects of even high doses of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation (up to 3.7 g/day), with the present state of knowledge, there is no evidence that prenatal supplementation with PUFAs improves brain development or acuity of vision in children. Instead of supplementation with PUFA during pregnancy, women should consume a diet with adequate PUFAs, with food that includes eggs and fish, with caution about the mercury content of fish.

Dr. Koren is professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program. He also holds the Ivey Chair in Molecular Toxicology at the department of medicine, University of Western Ontario, London. He had no disclosures relevant to this topic. E-mail him at [email protected].

Hormone therapy for menopausal vasomotor symptoms

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

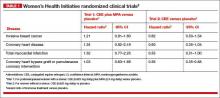

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

New Agents for the Treatment of Erythematotelangiectatic Rosacea

Rosacea is a common chronic disorder that predominantly manifests as facial erythema, telangiectasia, and flushing.1 Other primary clinical features include inflammatory lesions (eg, papules, pustules) and occasionally edema and rhinophyma. Ocular involvement also may occur. Rosacea patients routinely report sensitive skin with symptoms such as stinging, burning, and intolerance to topical agents (eg, medications, moisturizers, cosmetics).2,3

Rosacea affects facial appearance and can impair a patient’s emotional well-being. It may limit social and professional activities. Many patients and nonpatients alike presume the appearance of facial redness suggests alcohol overuse or emotional distress.4-6 A reduction in facial erythema as well as improvements in other clinical signs of rosacea have been shown to reduce patient self-consciousness and lead to increased socialization.7 Facial erythema is a major factor that adversely affects quality of life in rosacea patients.8

Although a number of options are available to successfully treat inflammatory lesions of rosacea, facial erythema has been the most difficult manifestation of the disease to medically treat.2,9 Chronic erythema and episodic flushing may be at least partially related to cutaneous vasomotor responses causing both transient and persistent dilation of facial blood vessels.10-12 The agents used for treating the inflammatory components of rosacea reduce erythema associated with papules and pustules but have little effect on the background erythema that is so noticeable. Oxymetazoline and brimonidine tartrate have been evaluated as potential rapid treatments of facial erythema. Daily application of oxymetazoline solution 0.05% has been shown to reduce facial erythema in rosacea patients.13