User login

Painful Mouth Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

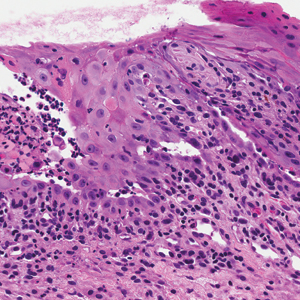

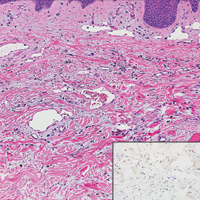

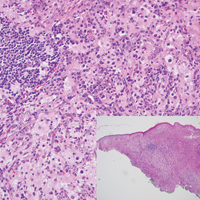

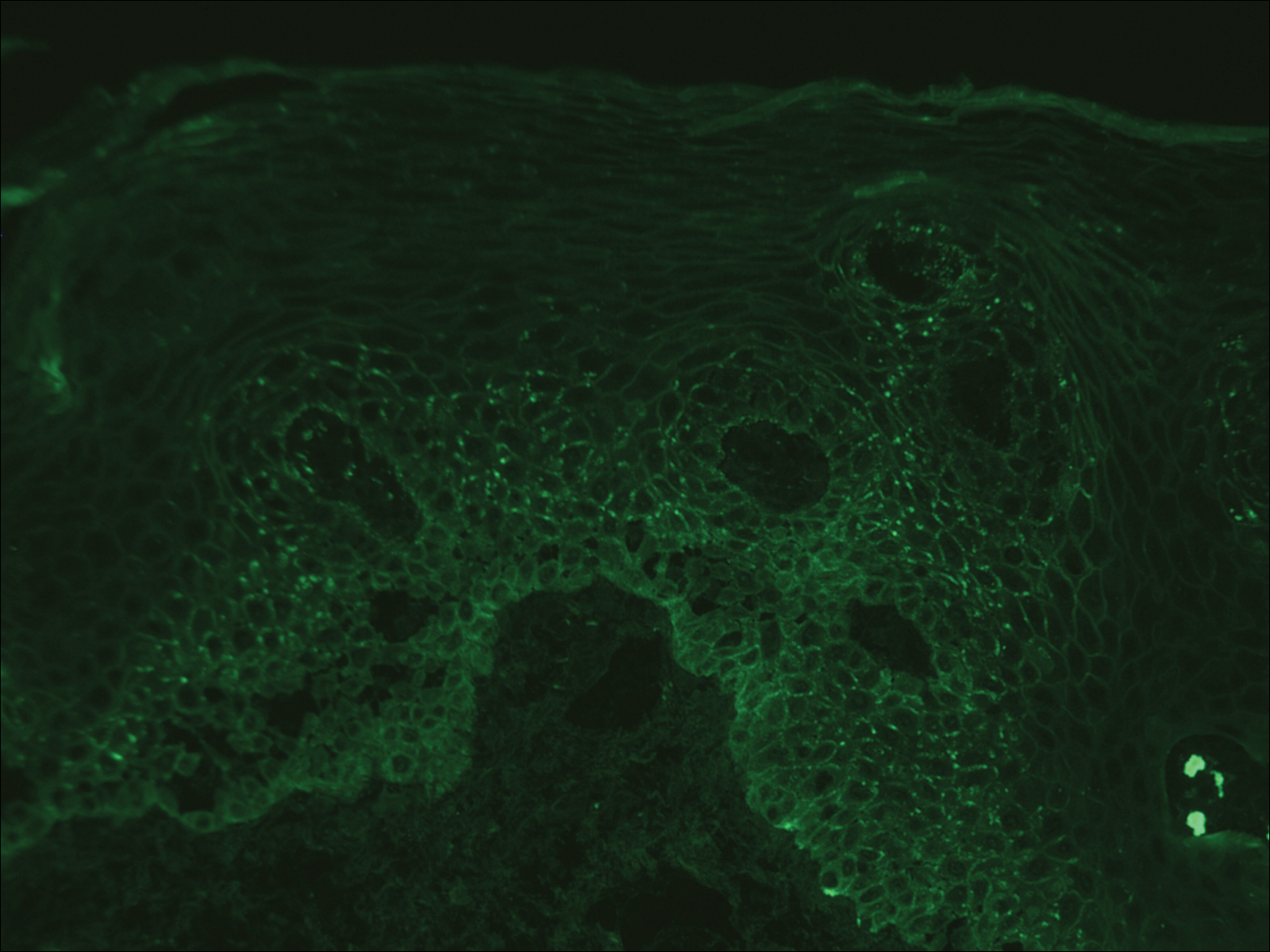

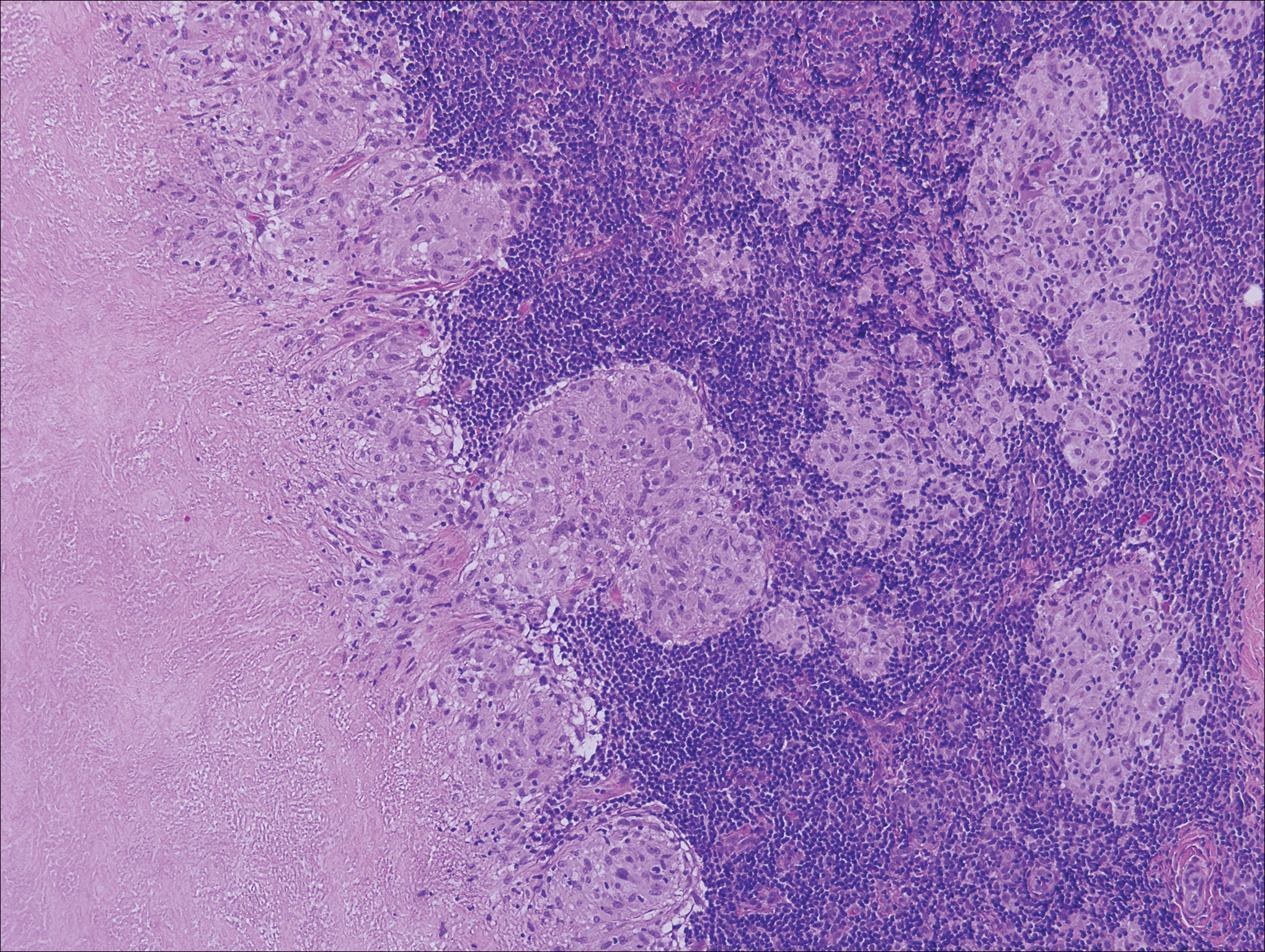

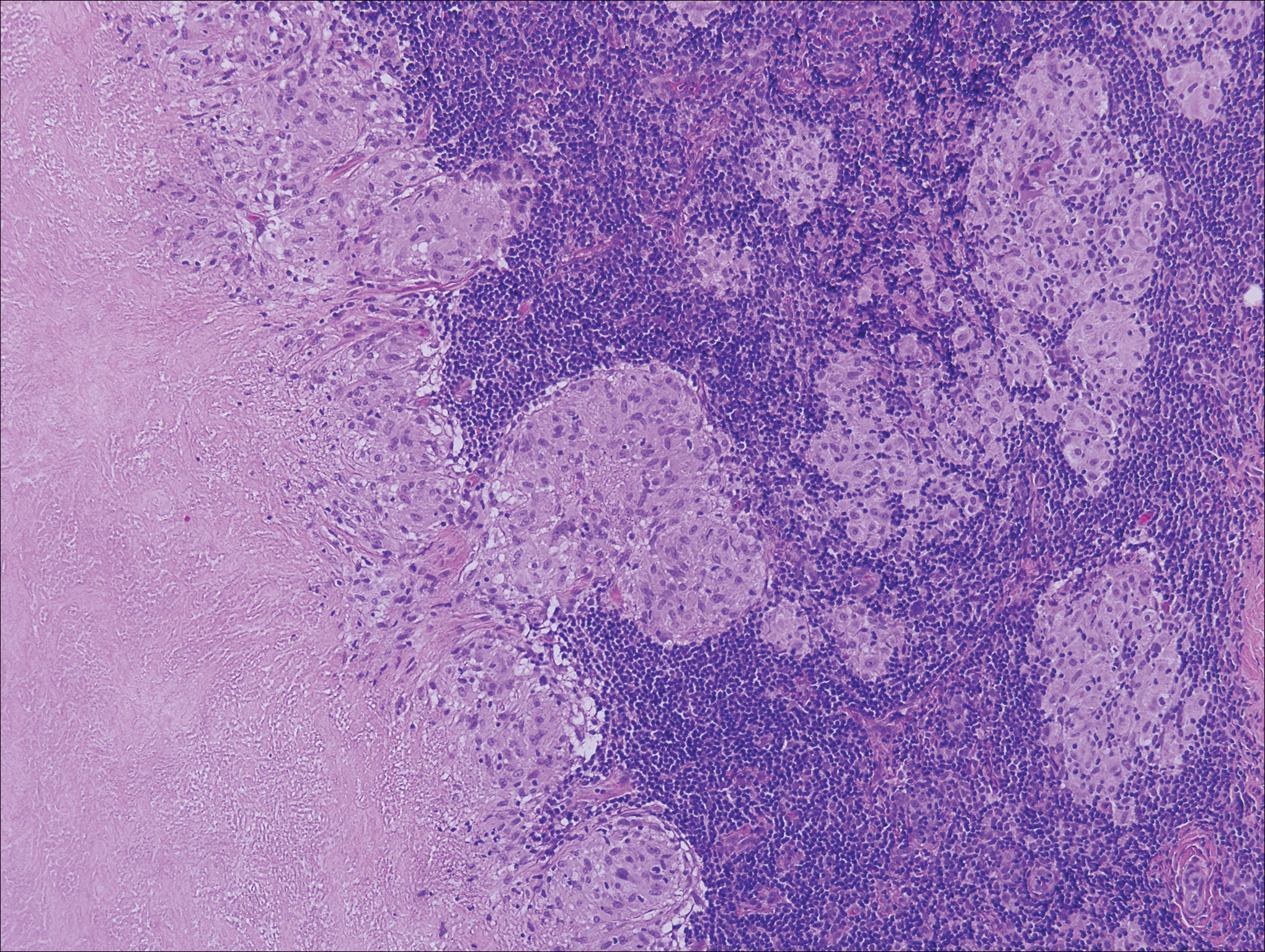

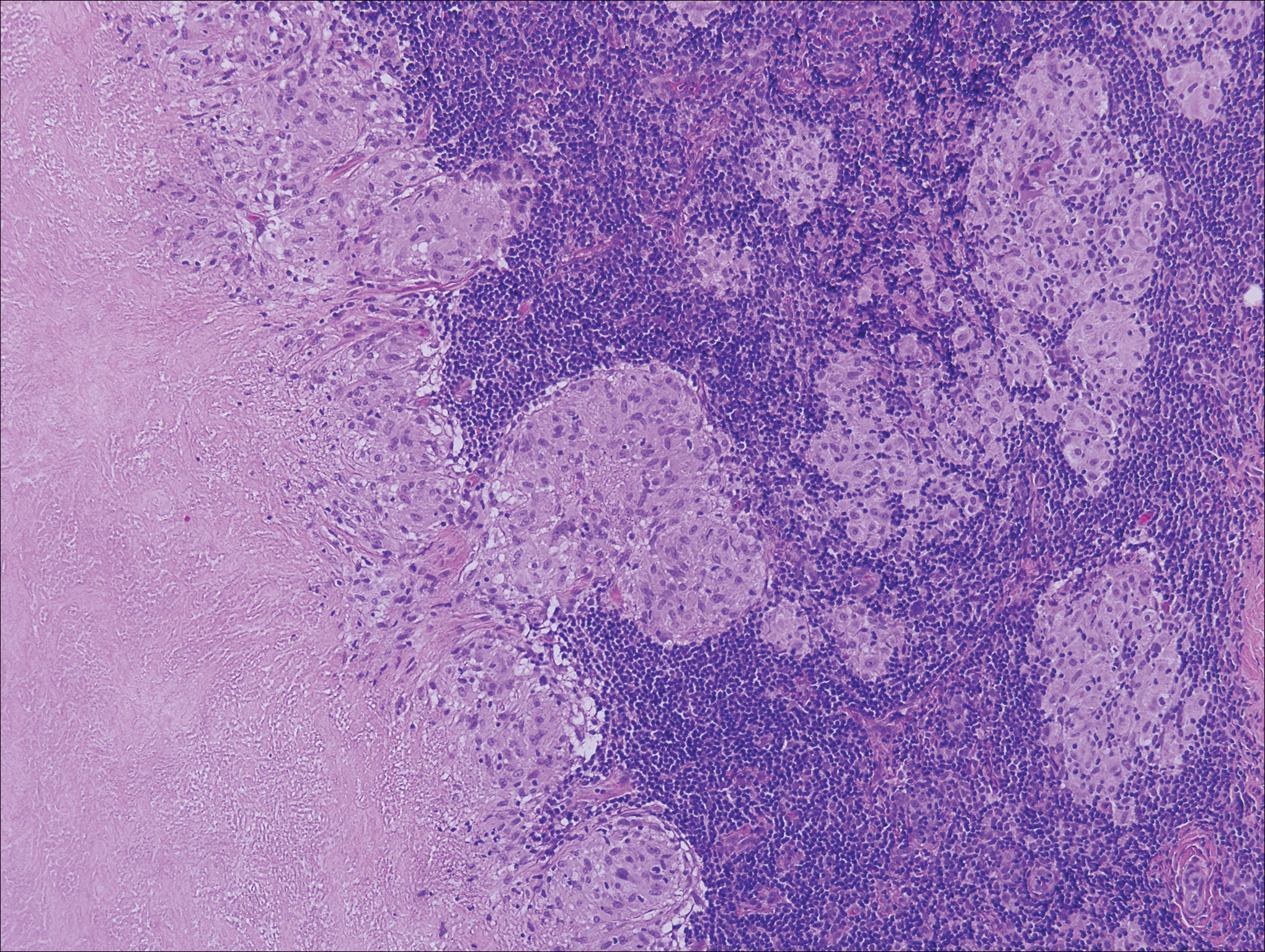

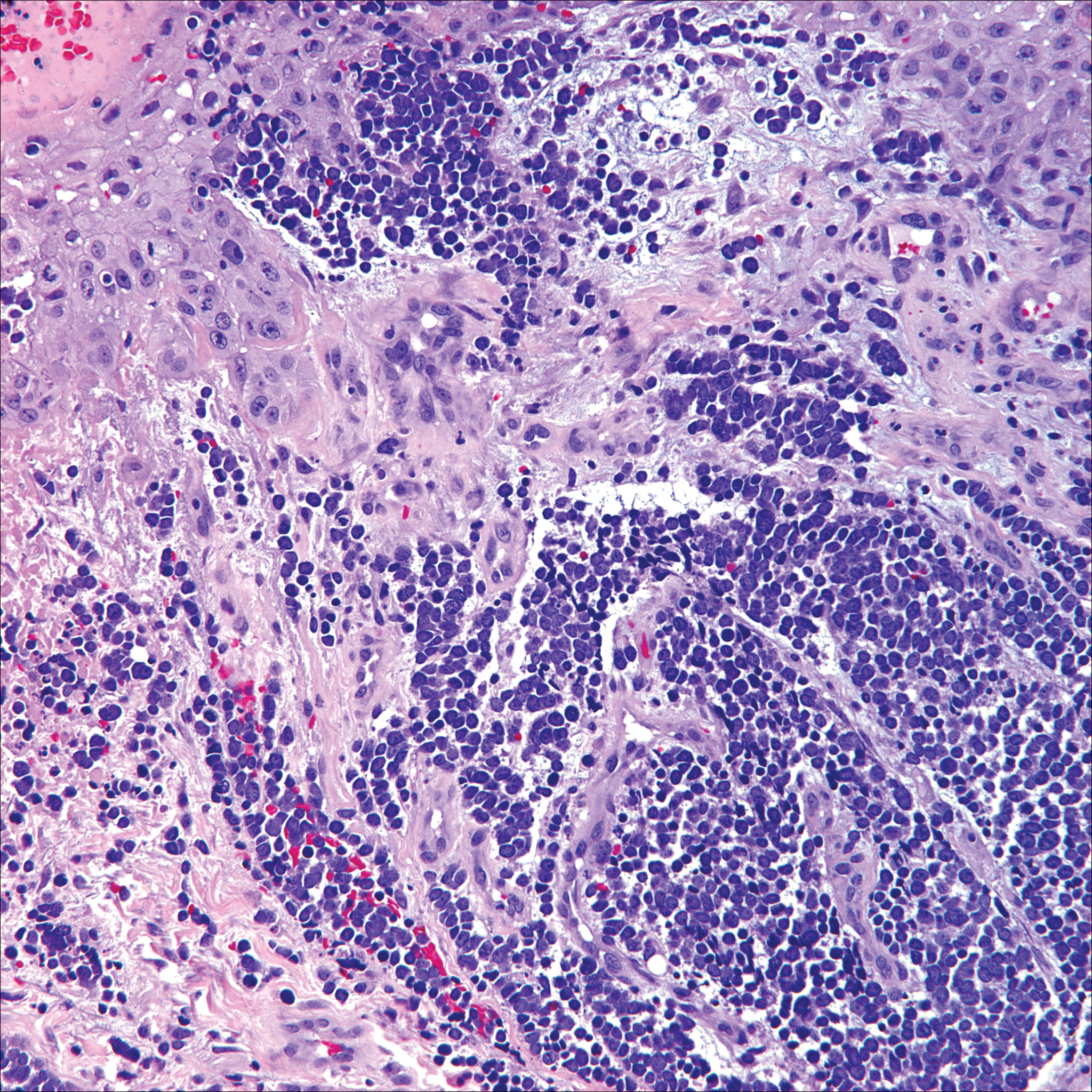

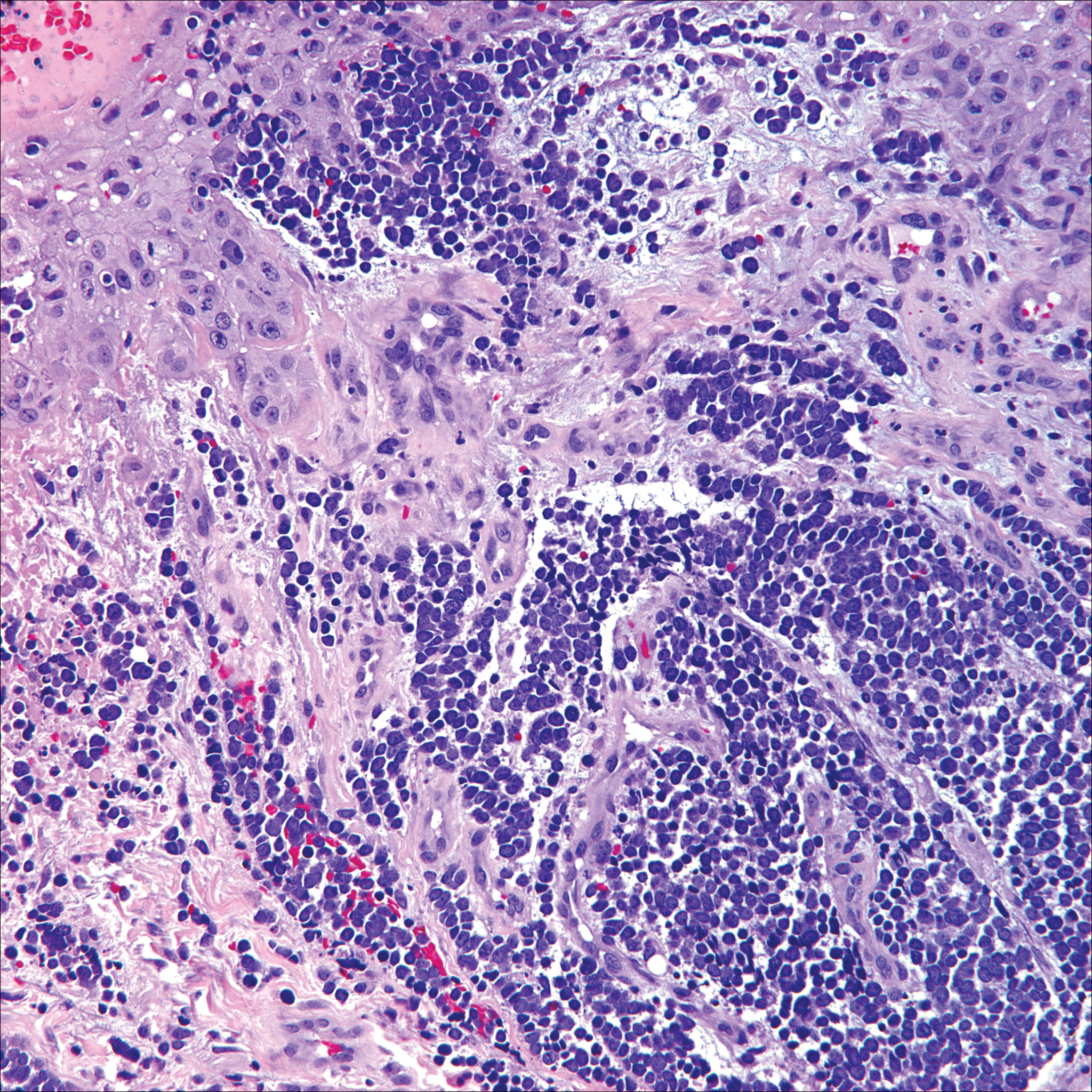

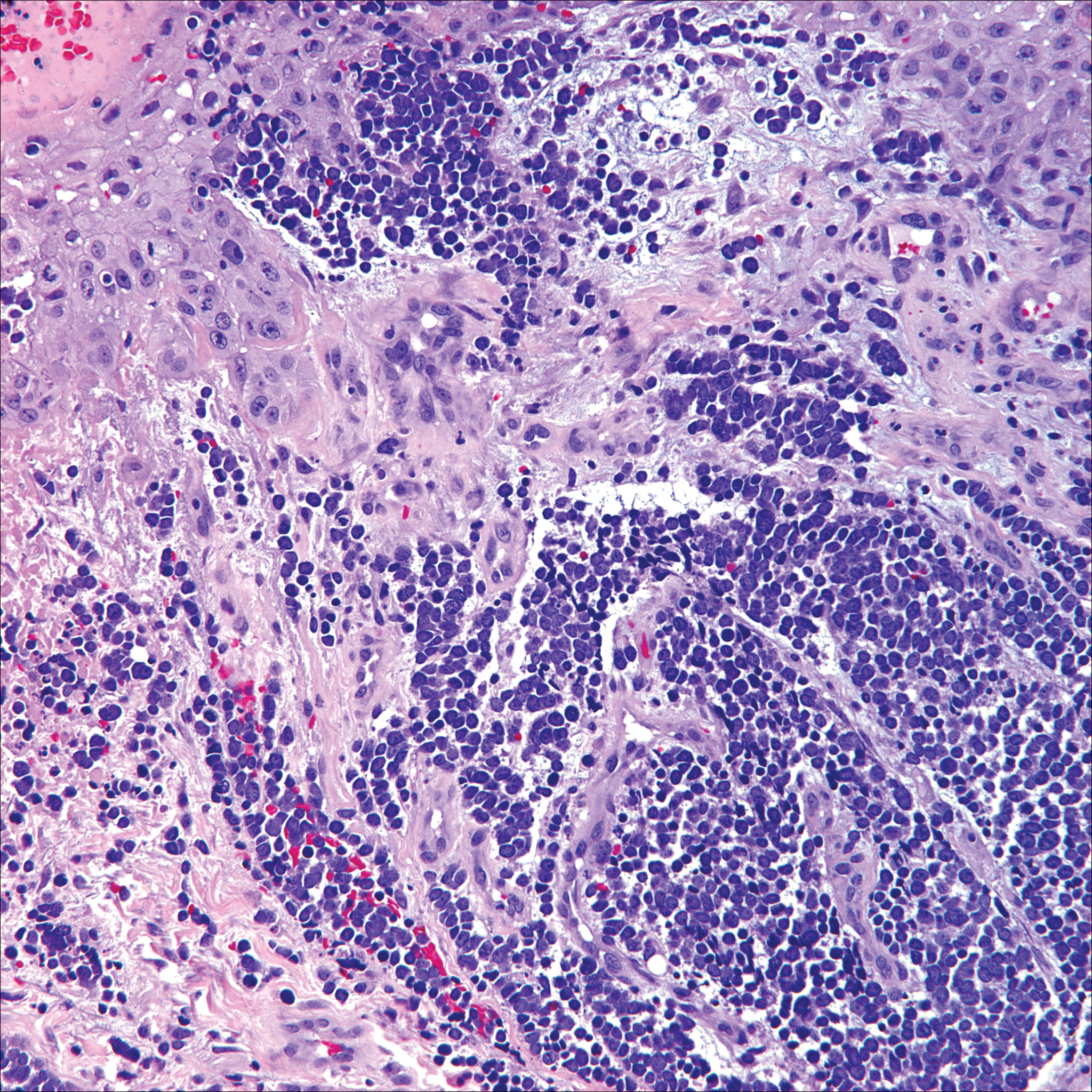

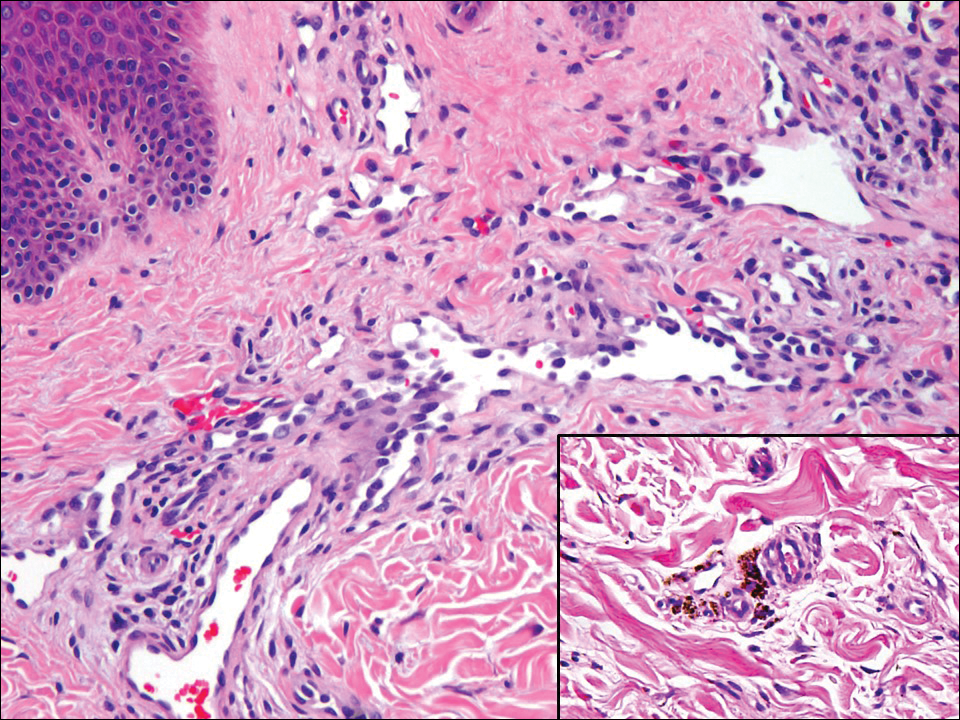

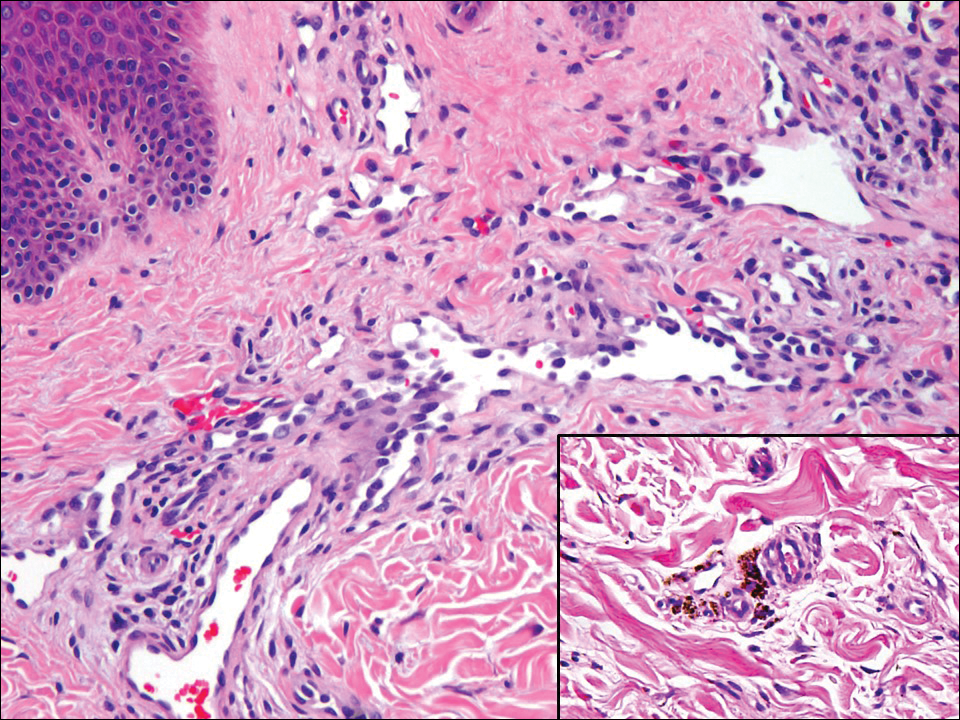

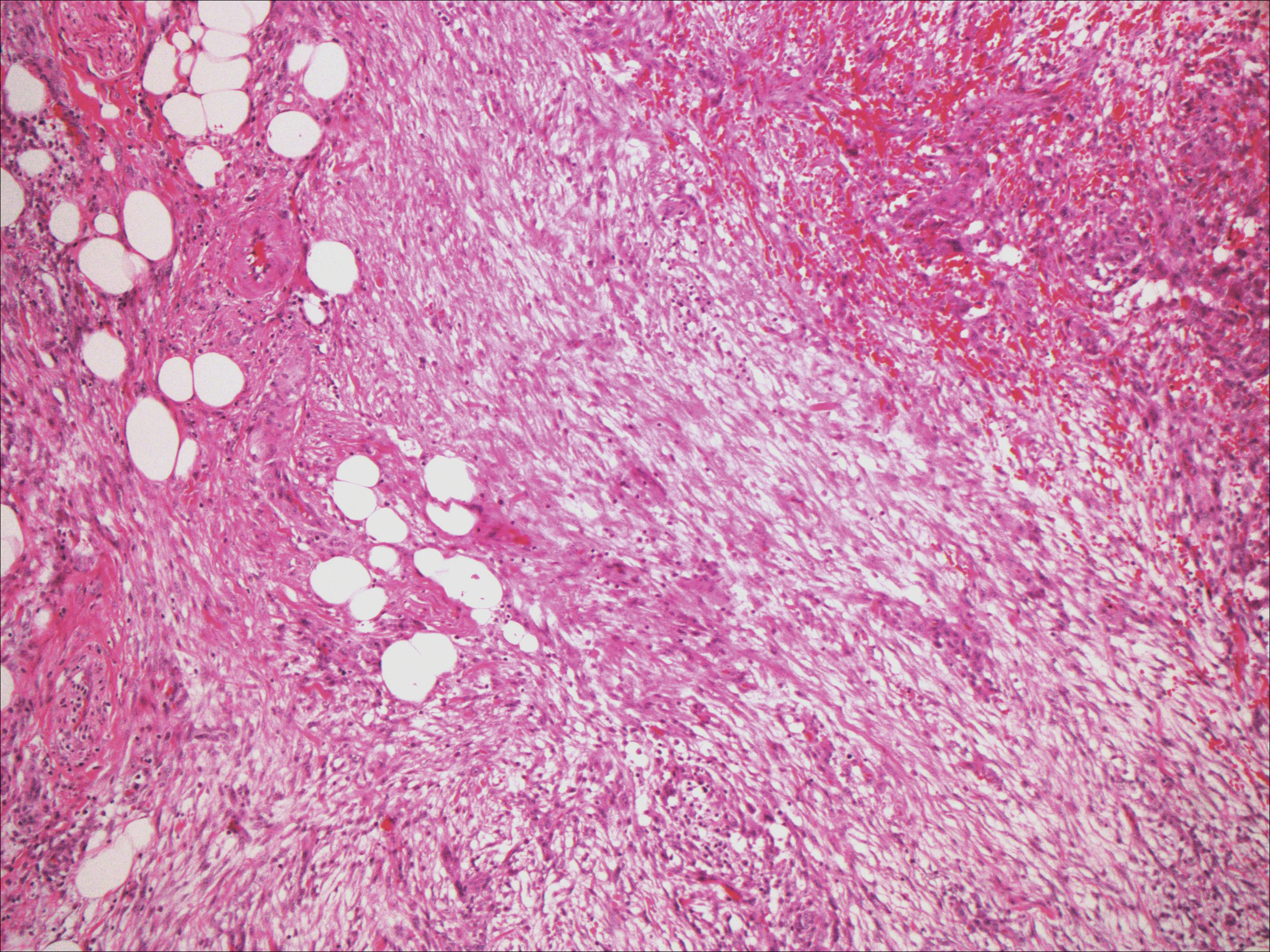

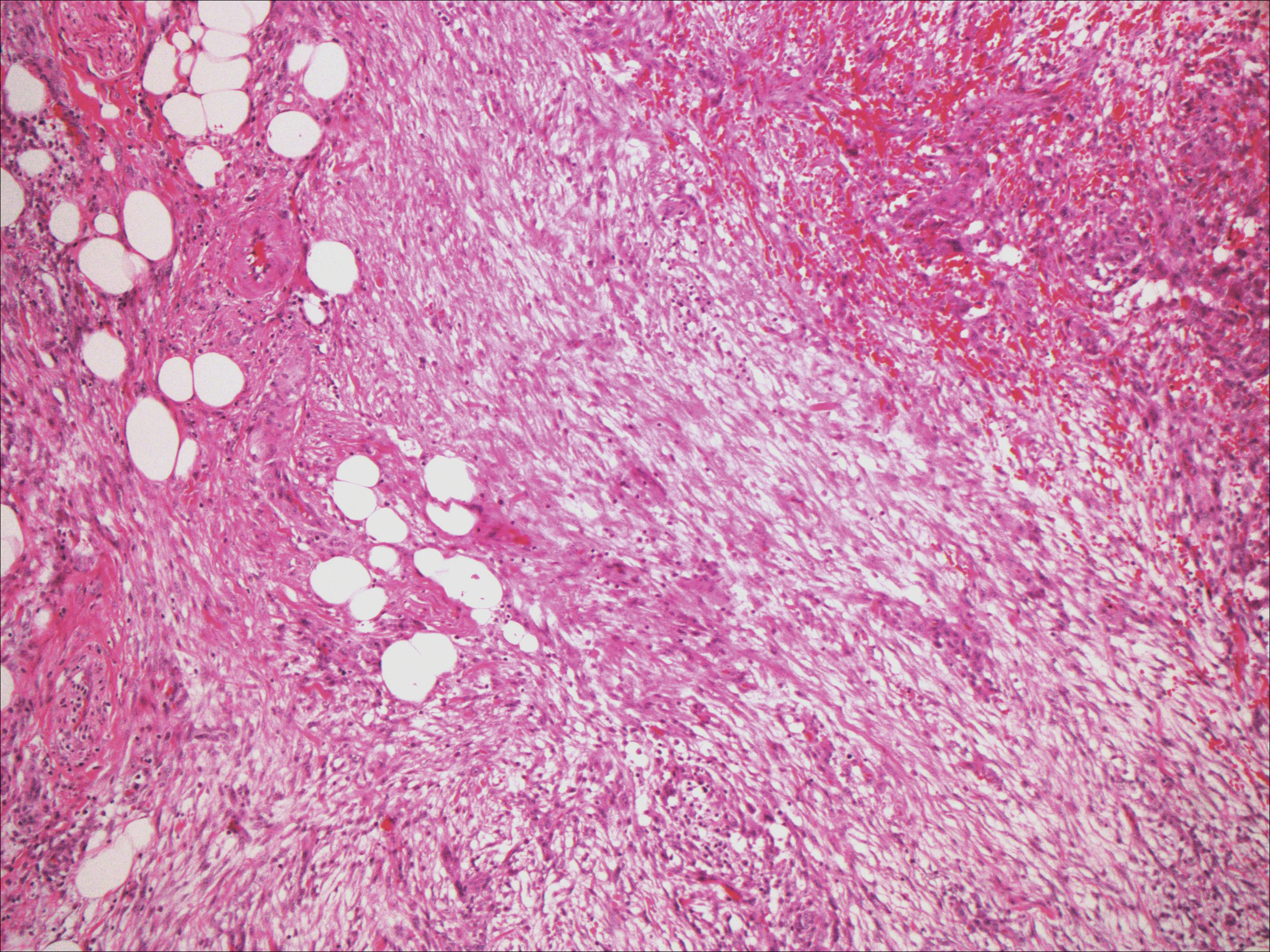

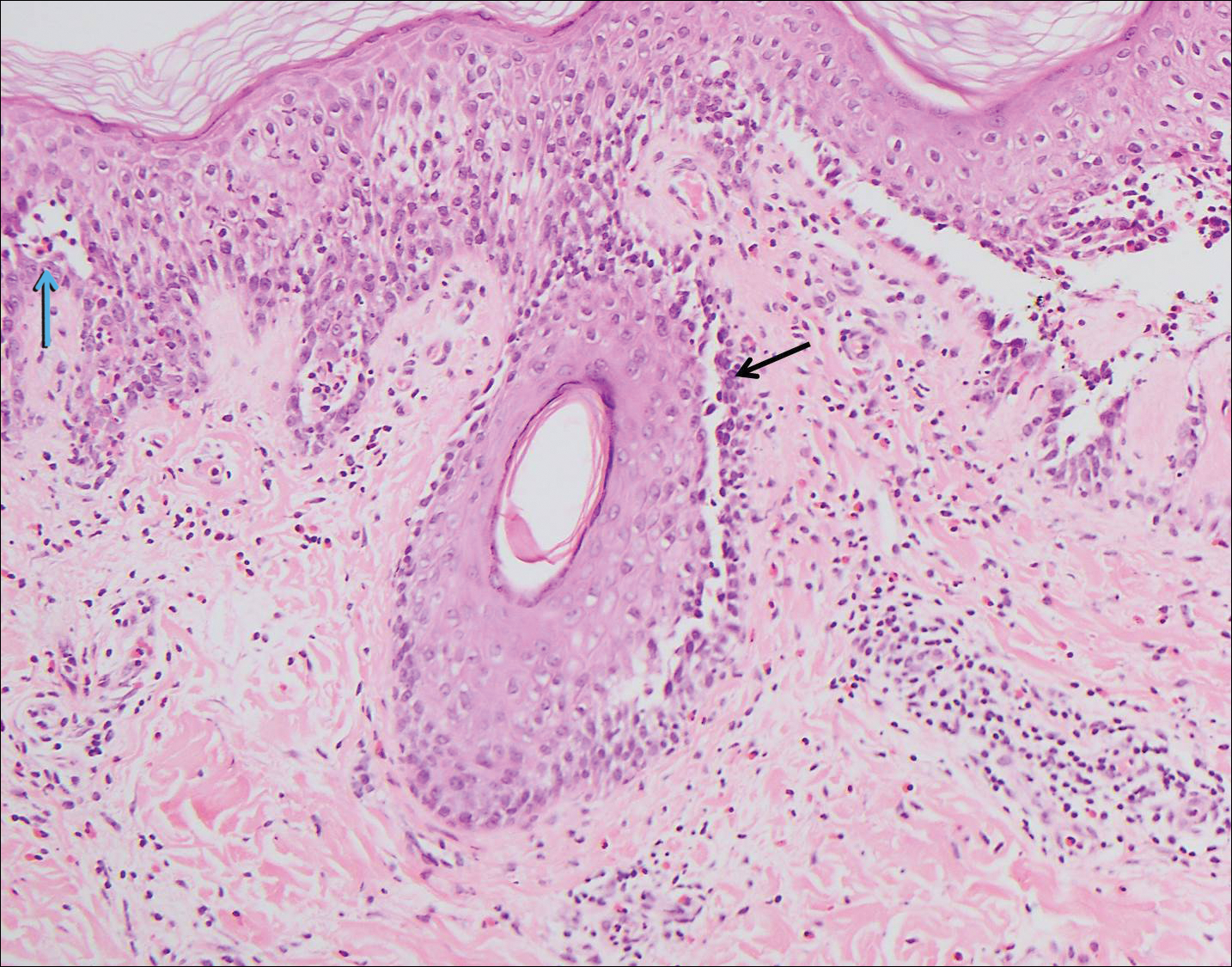

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

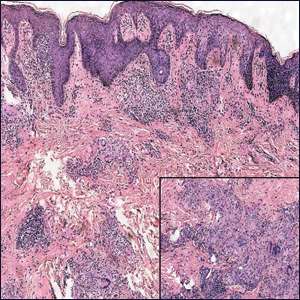

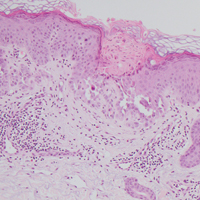

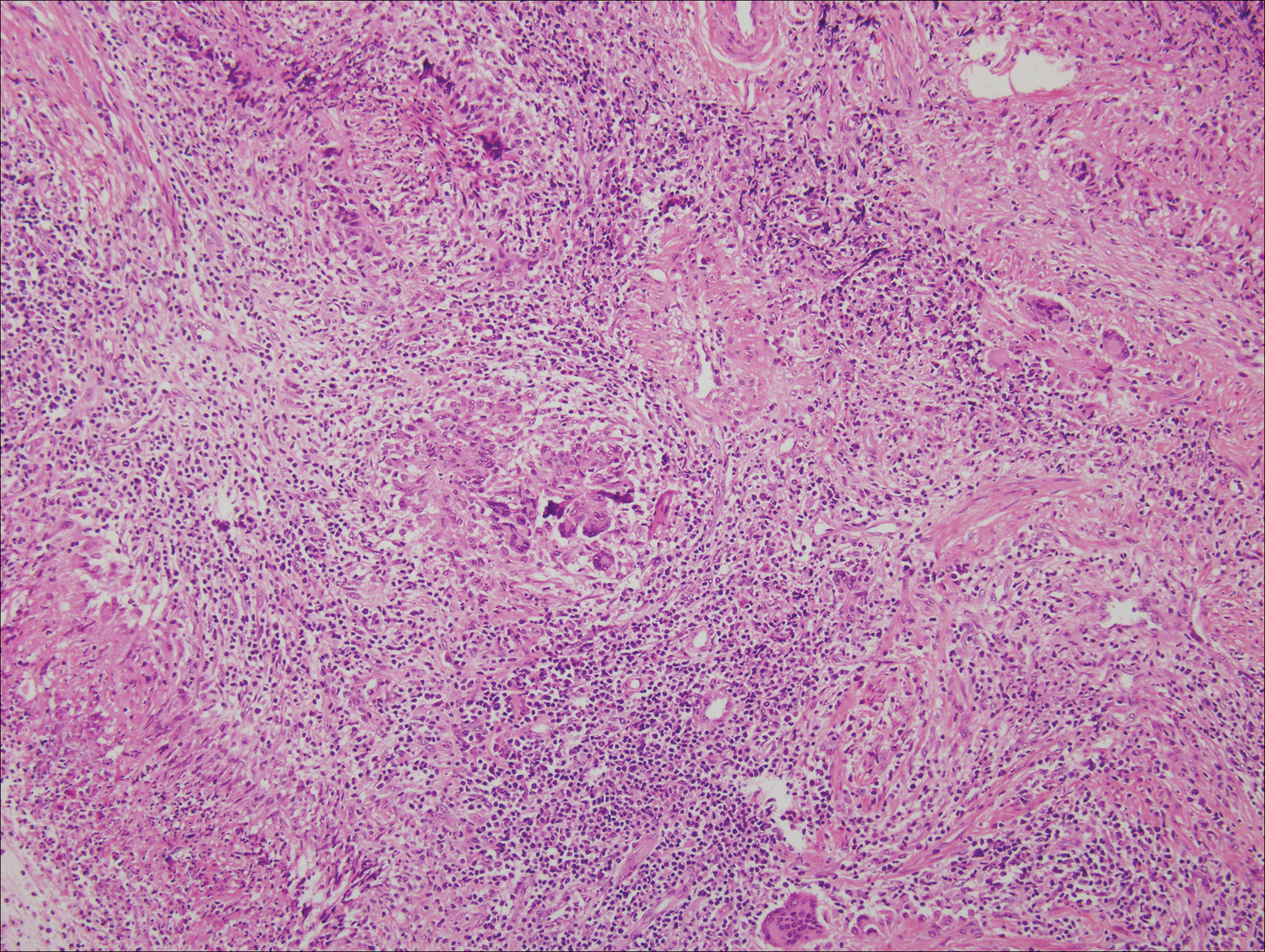

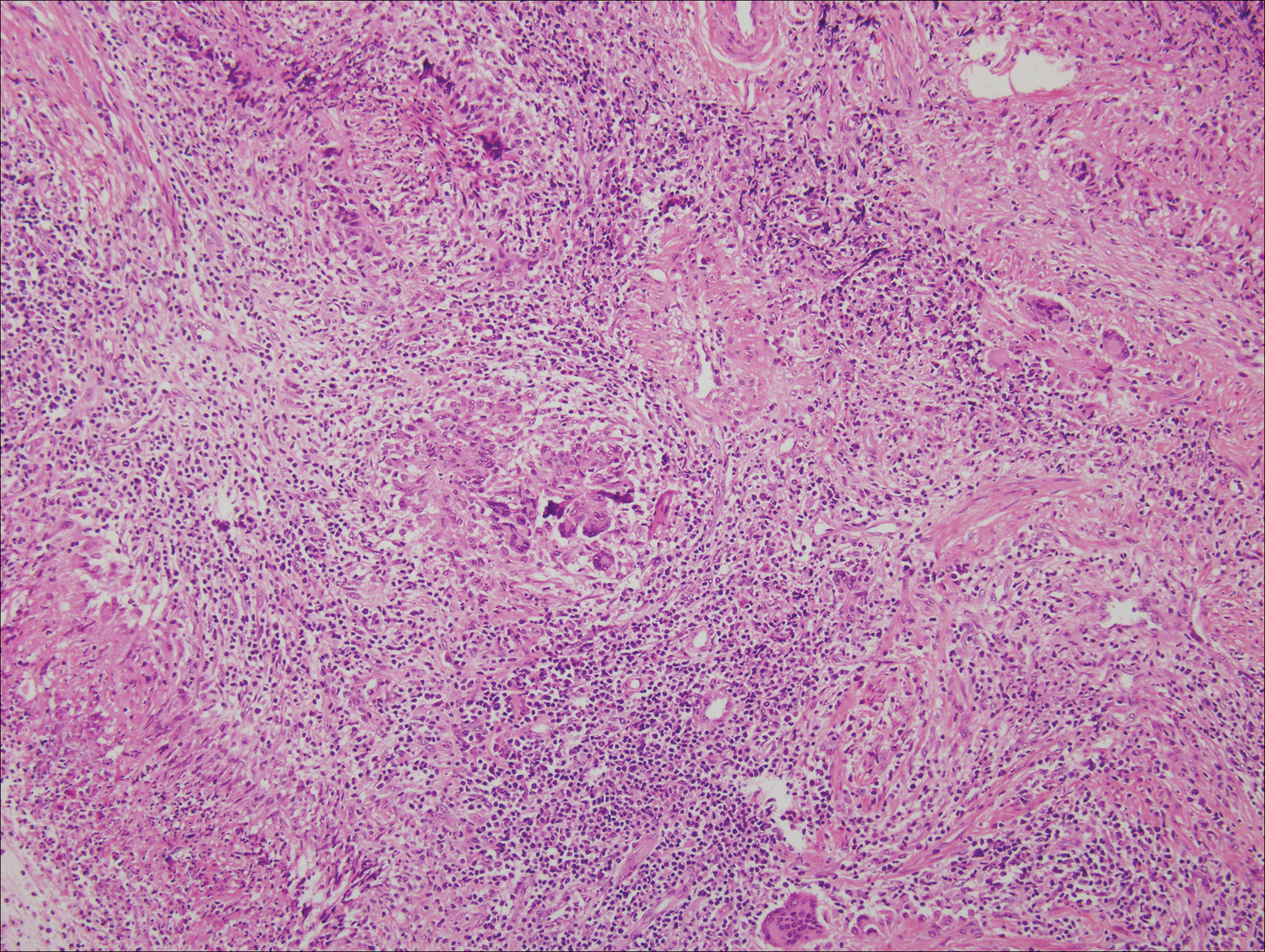

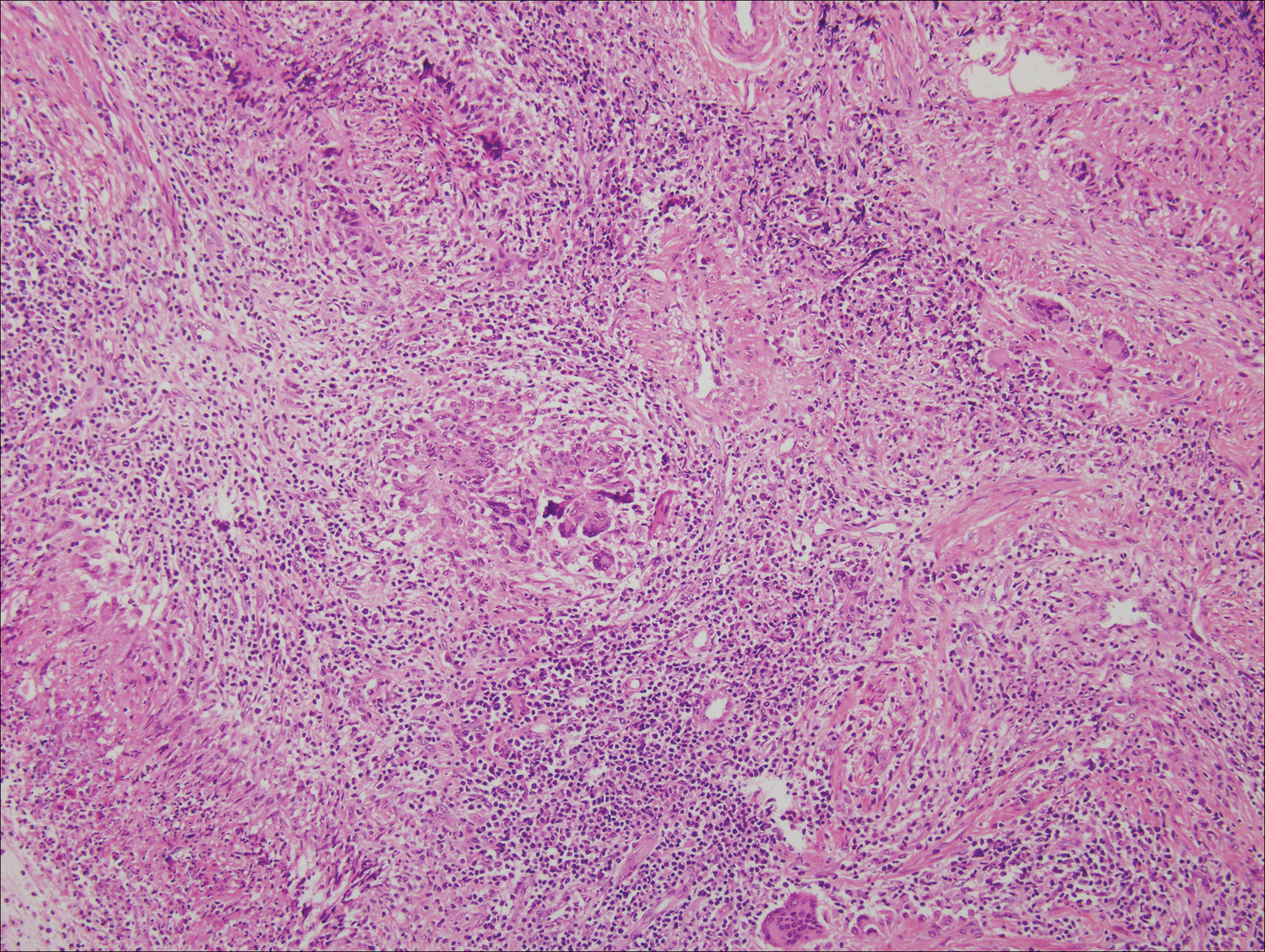

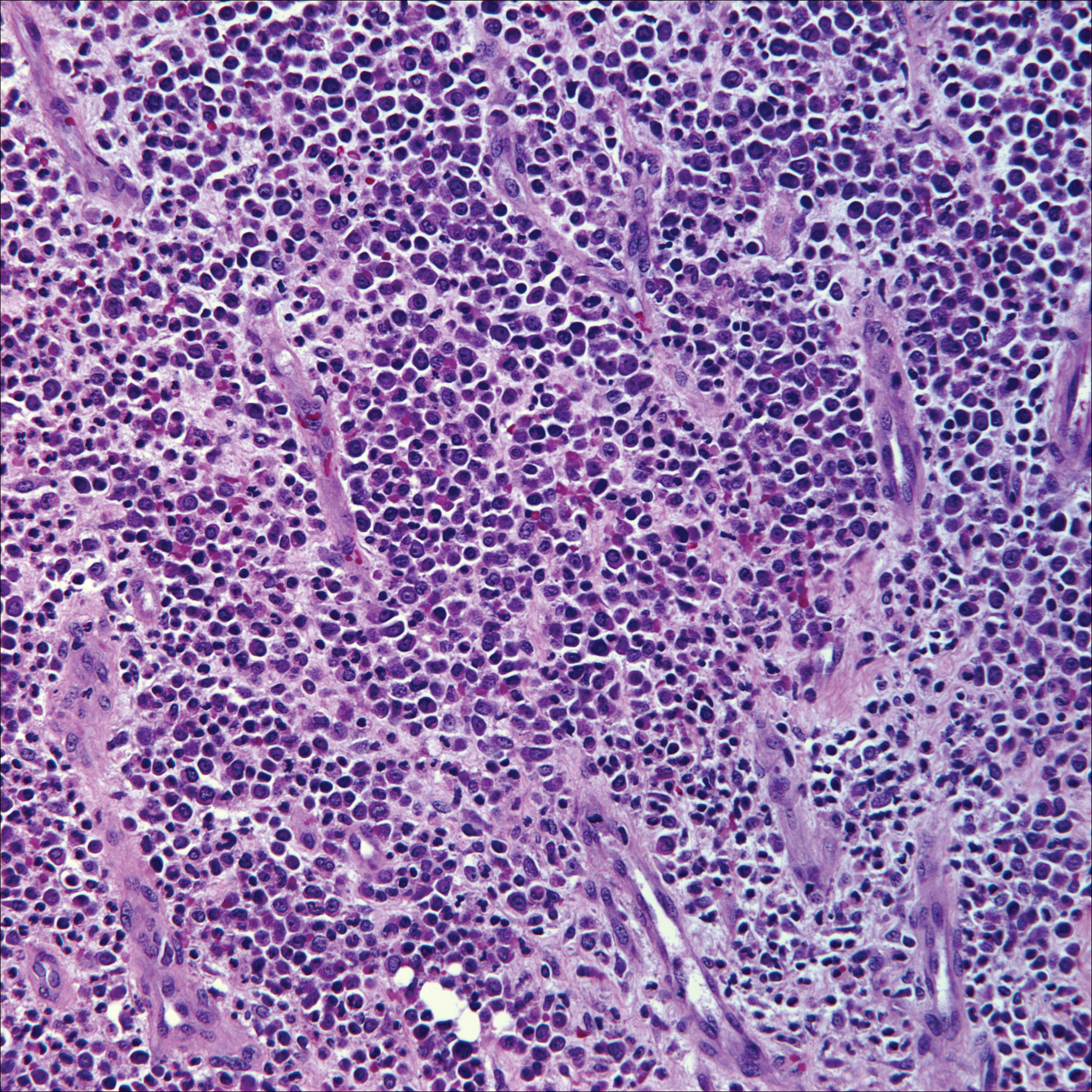

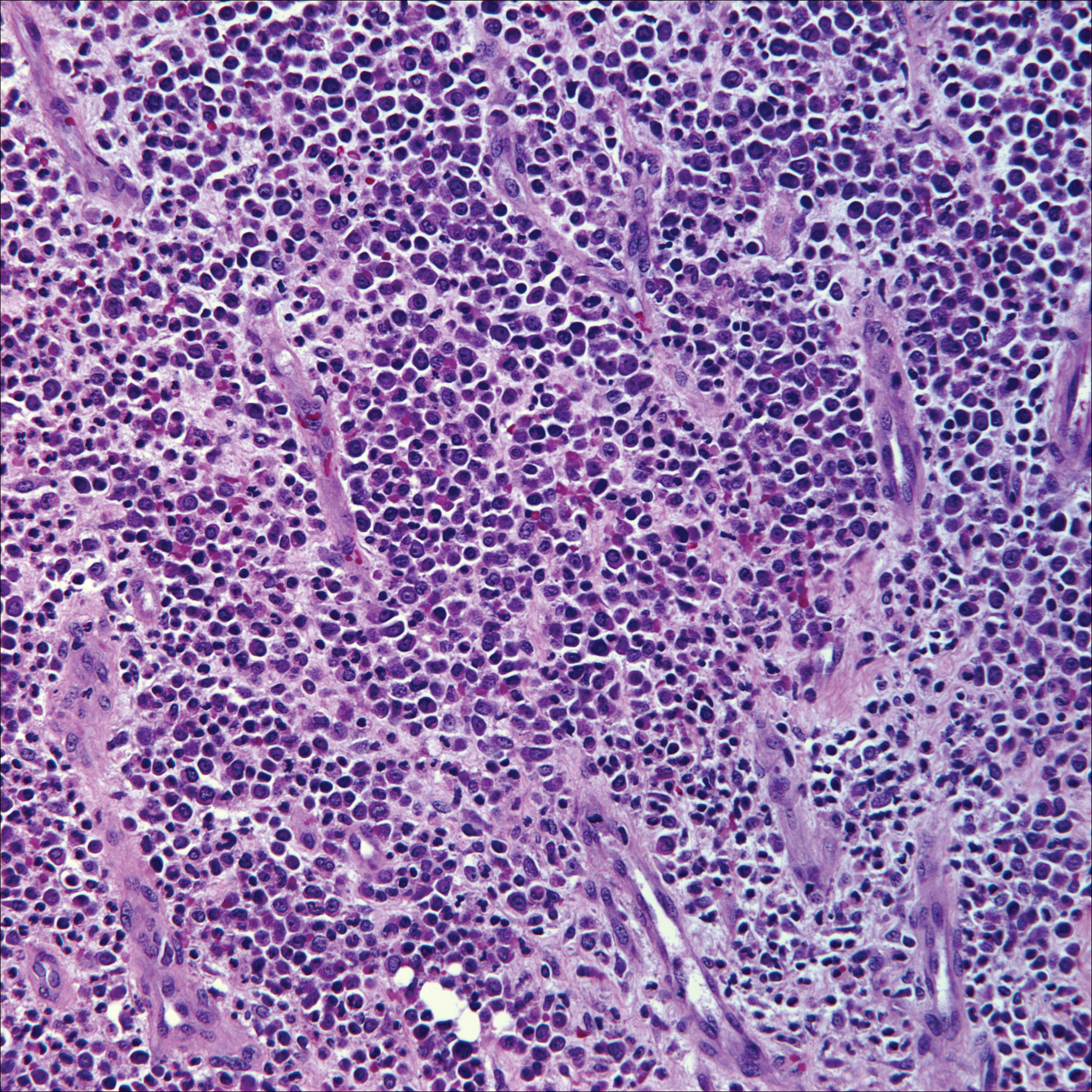

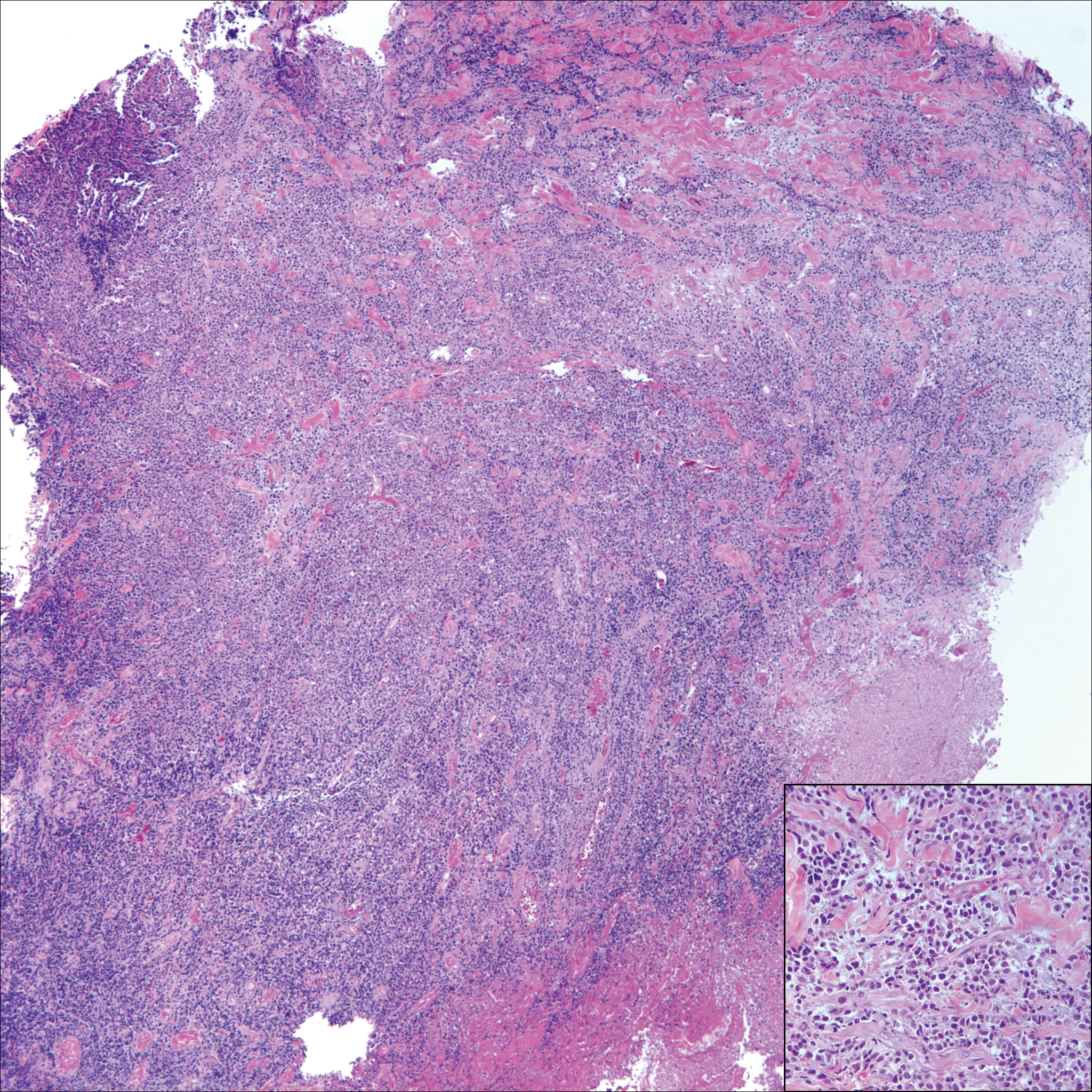

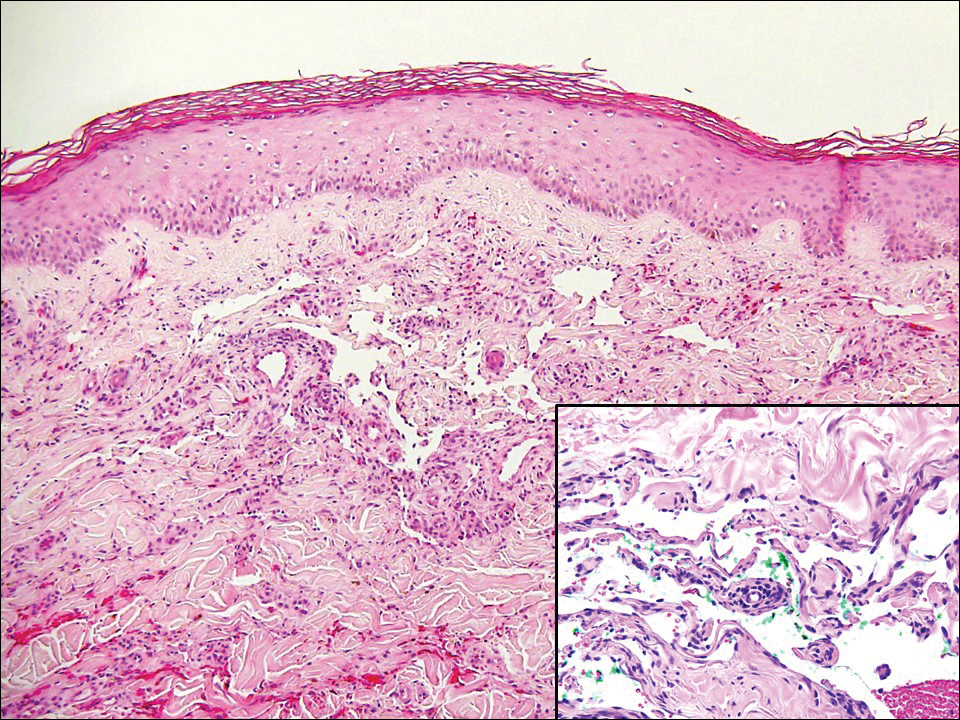

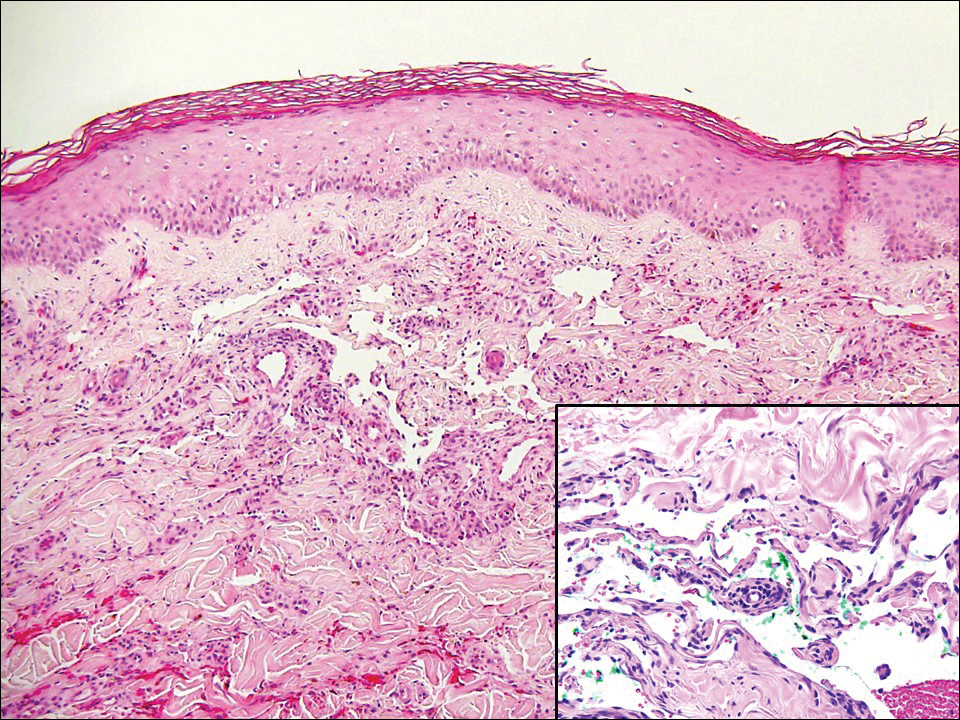

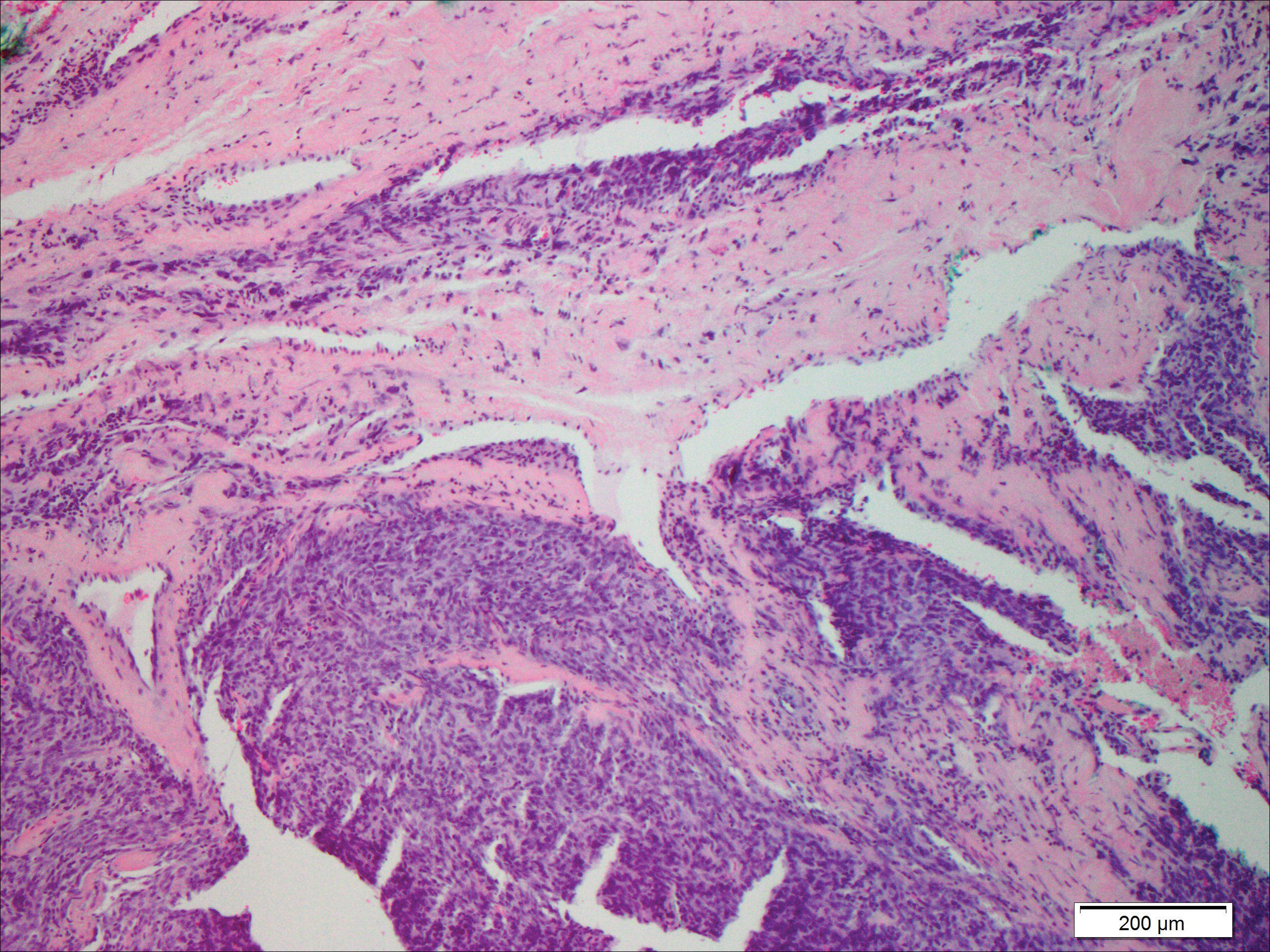

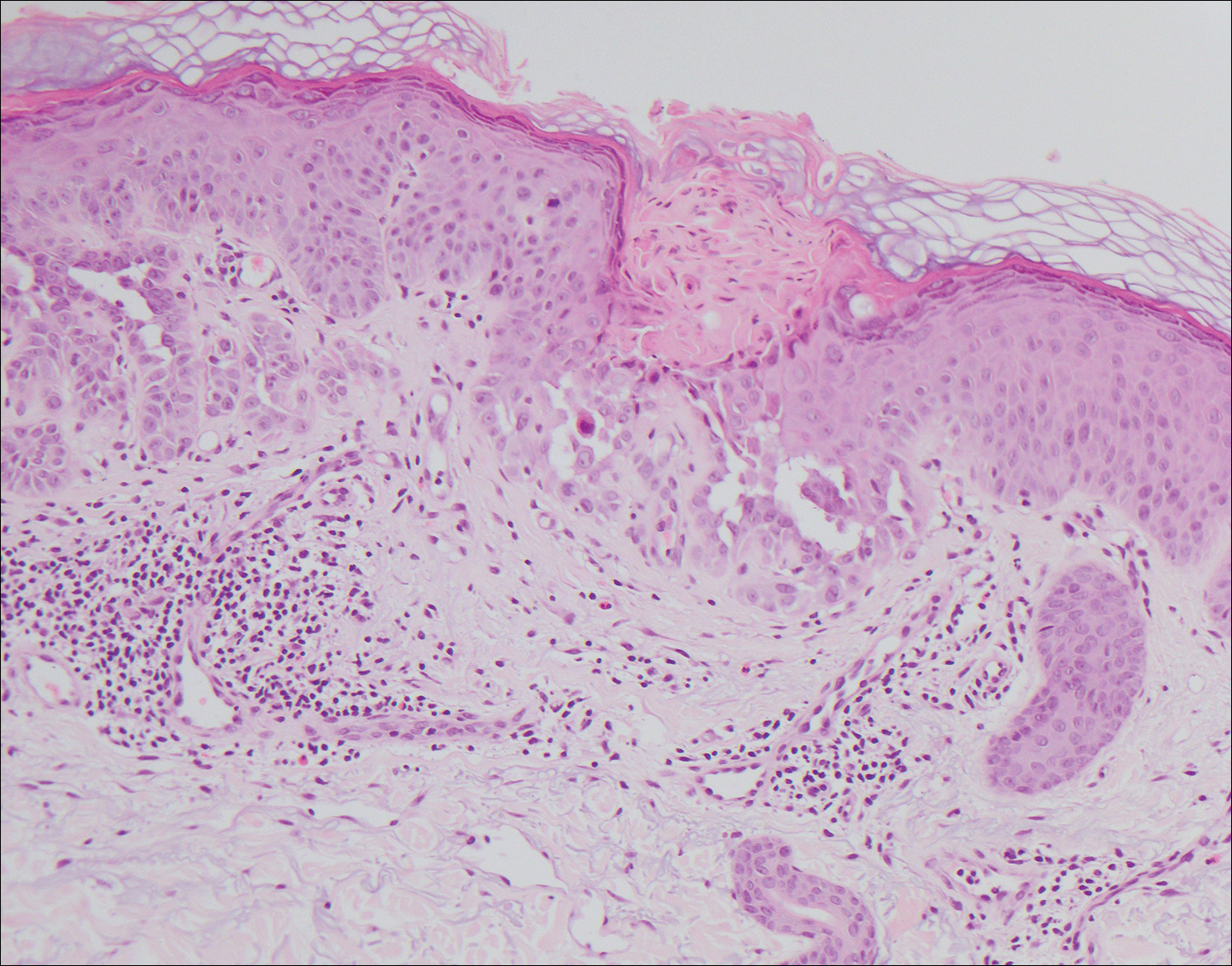

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

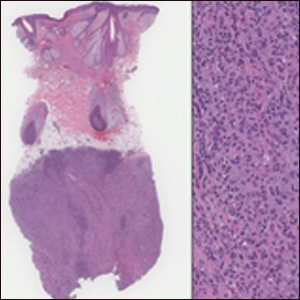

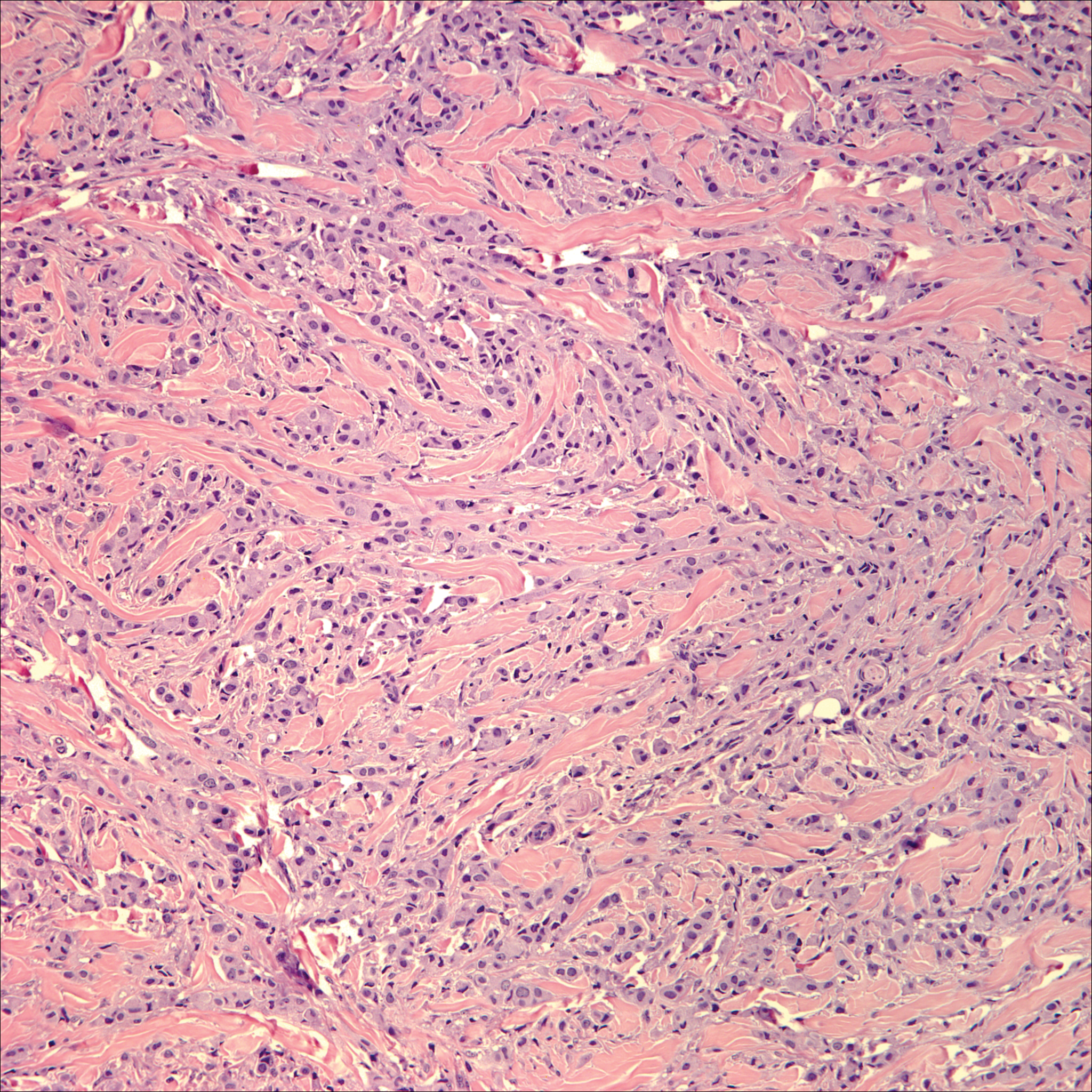

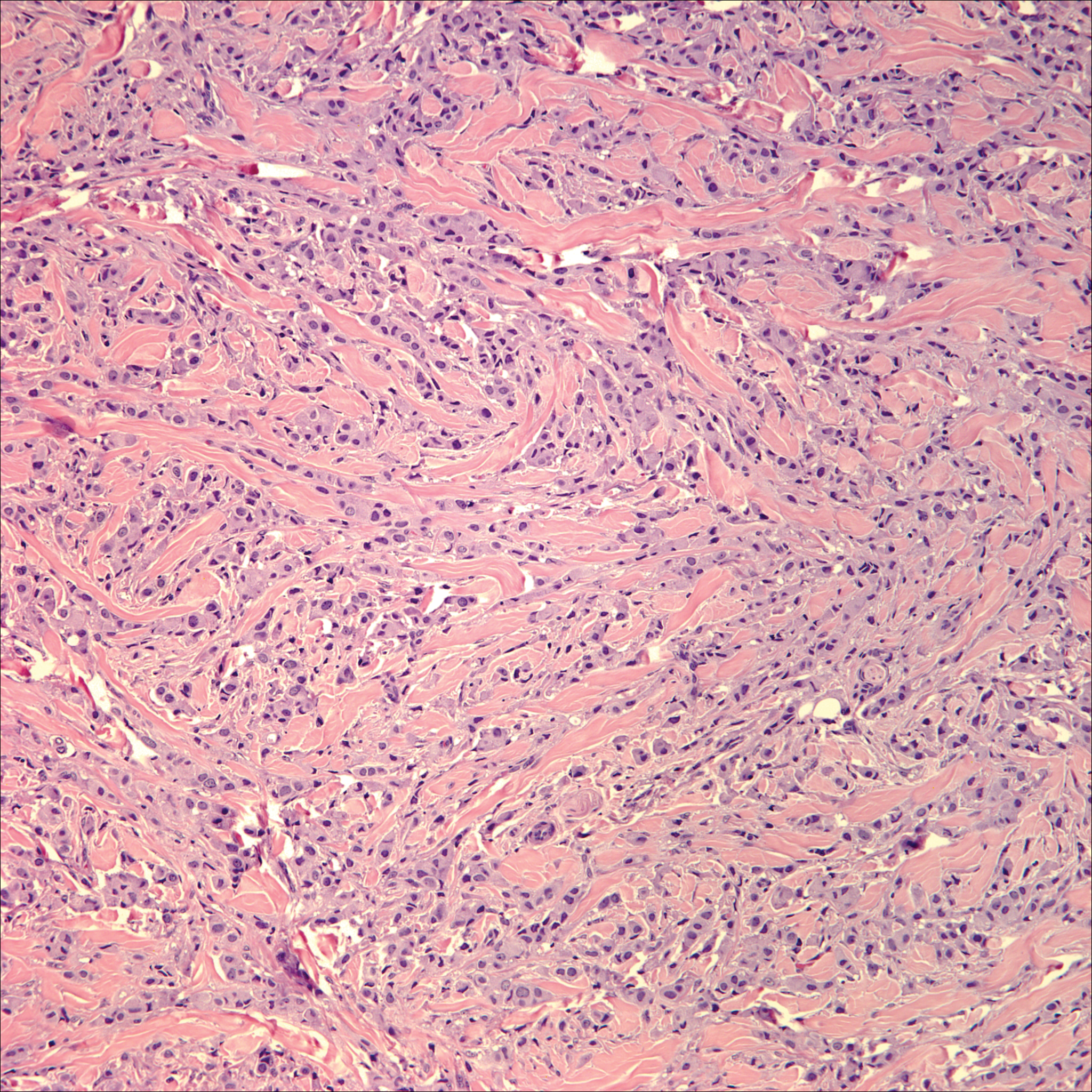

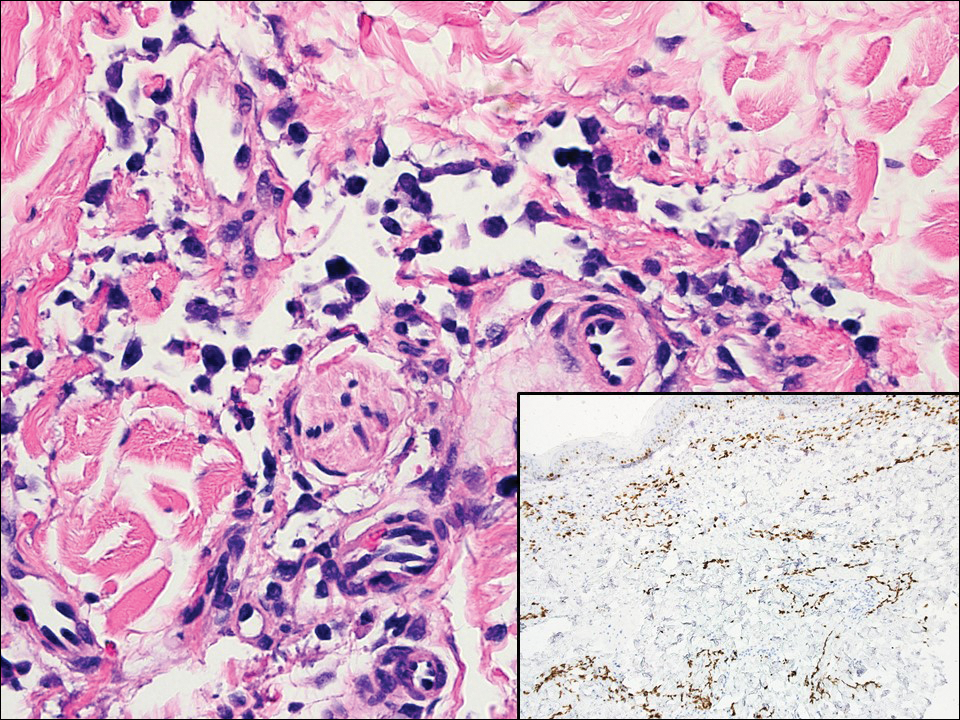

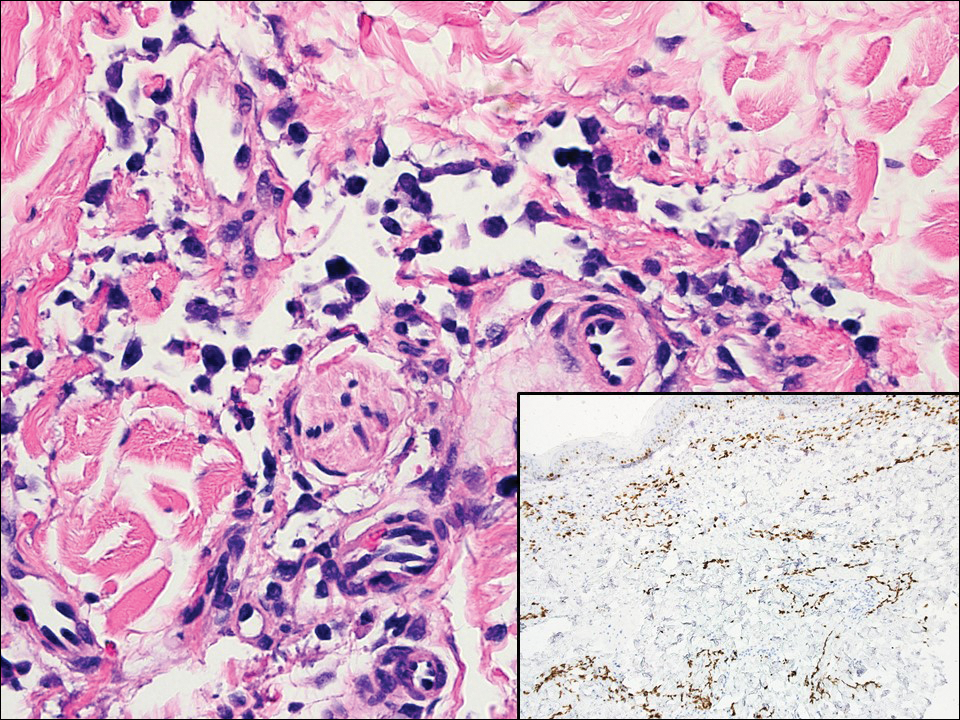

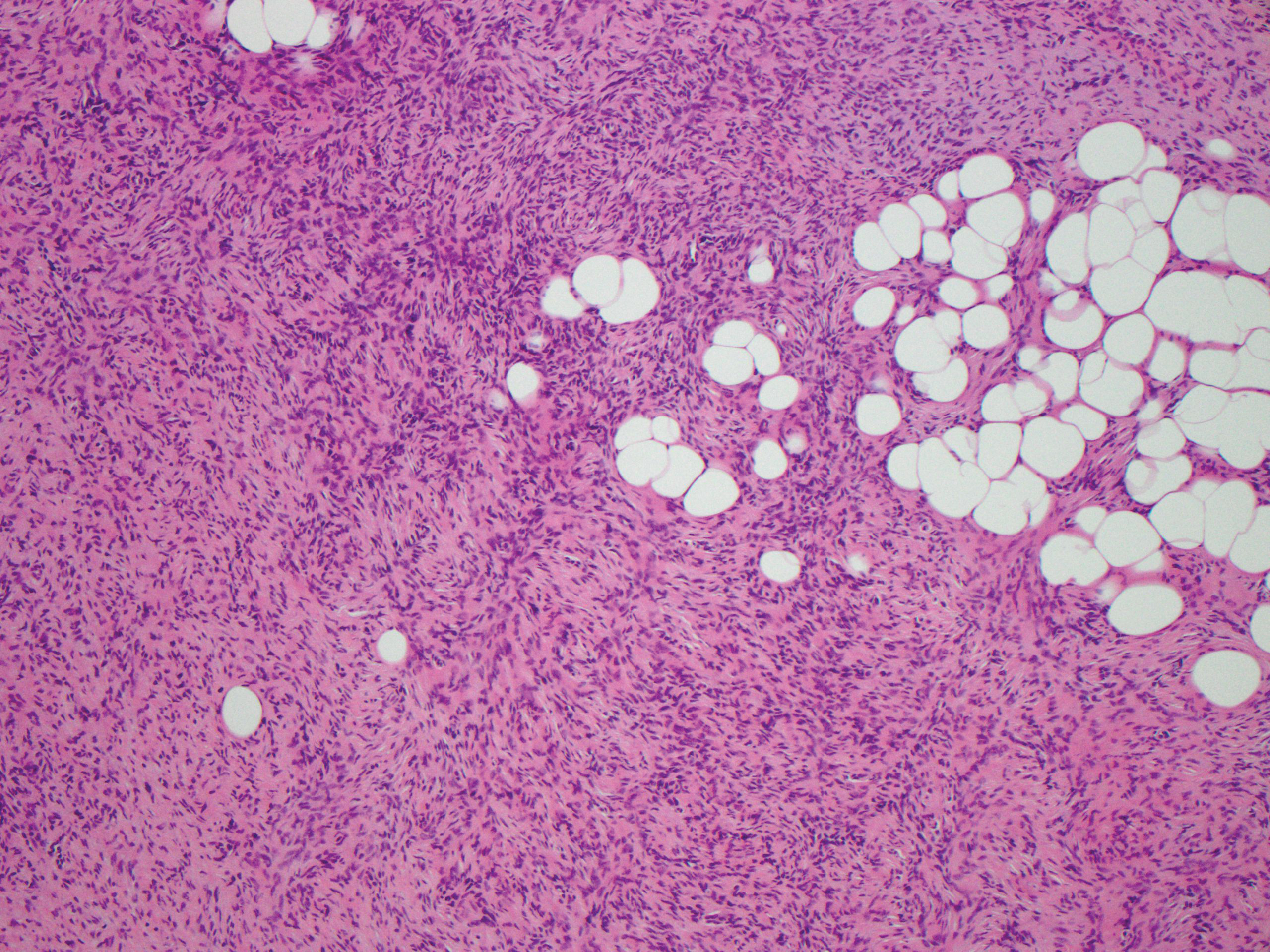

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

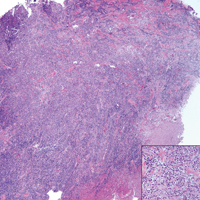

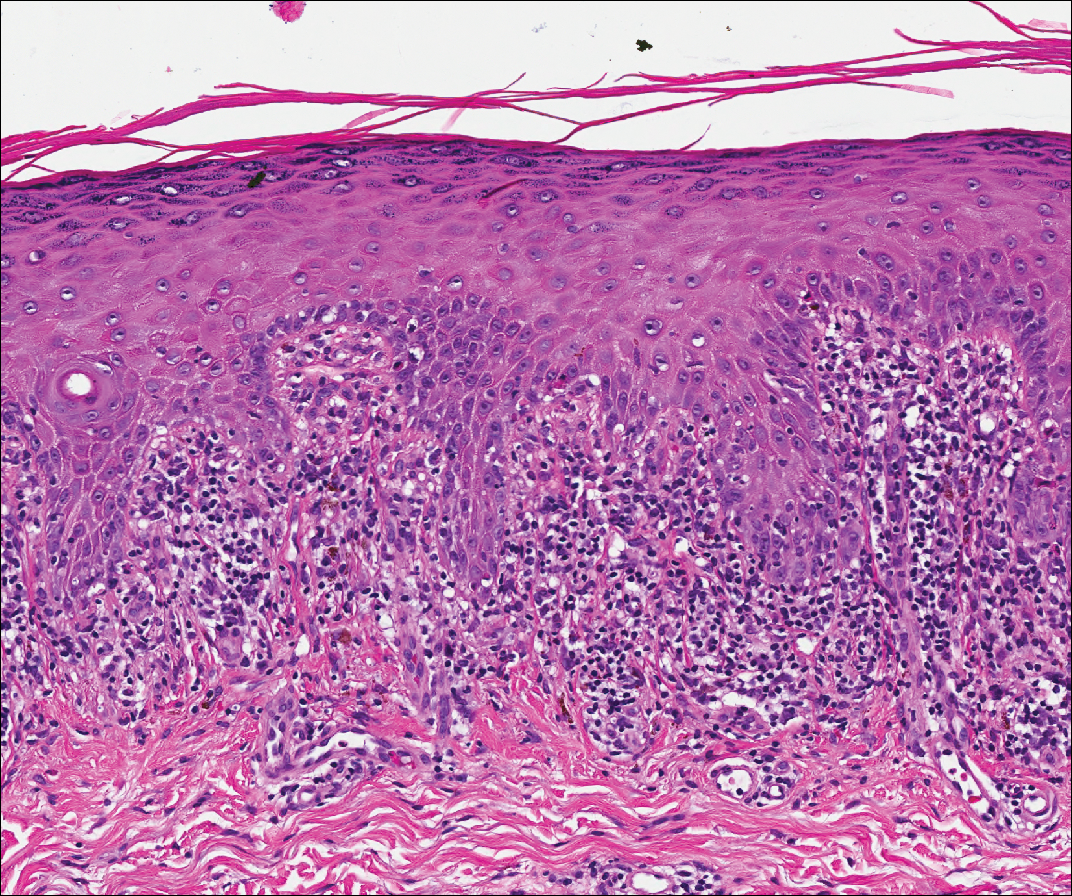

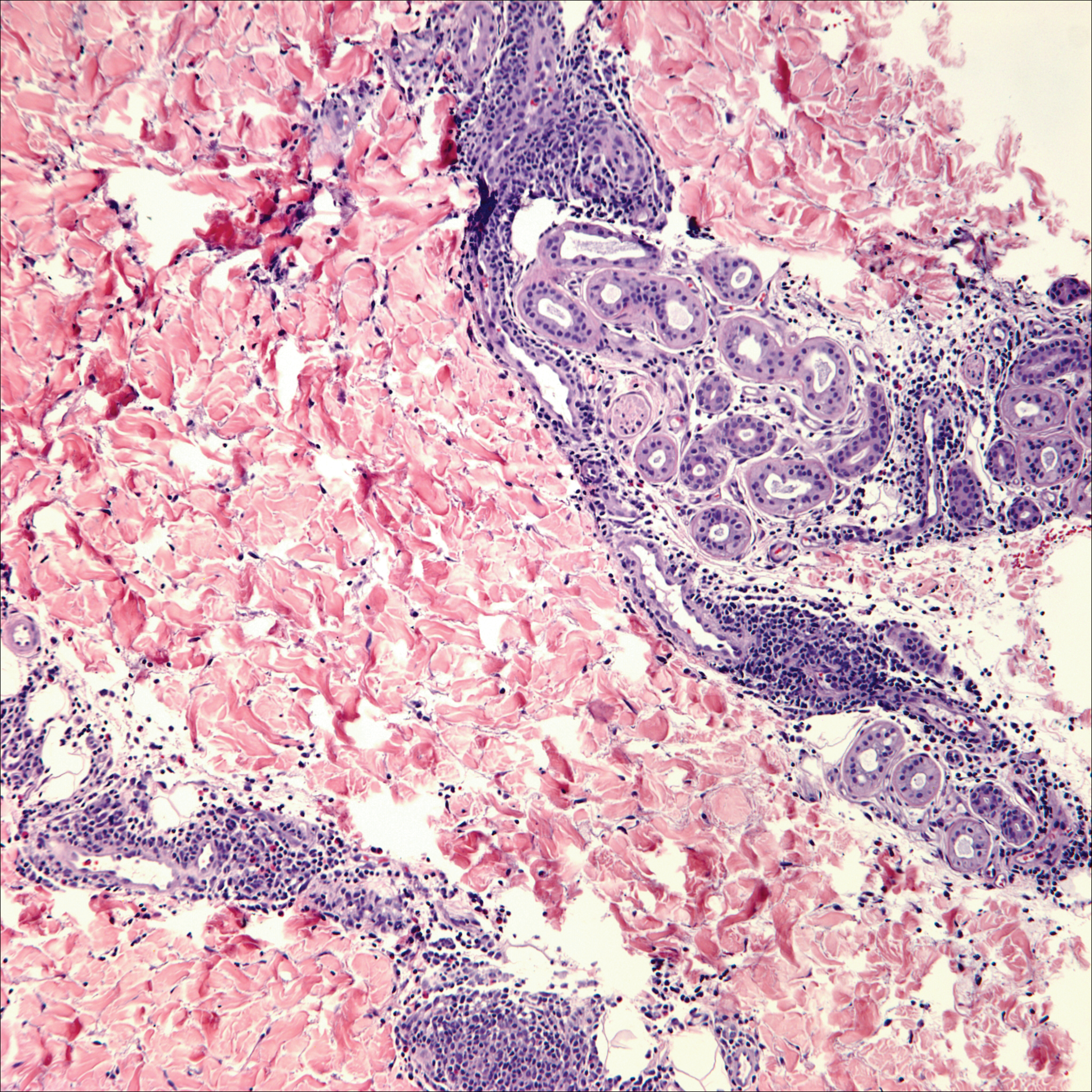

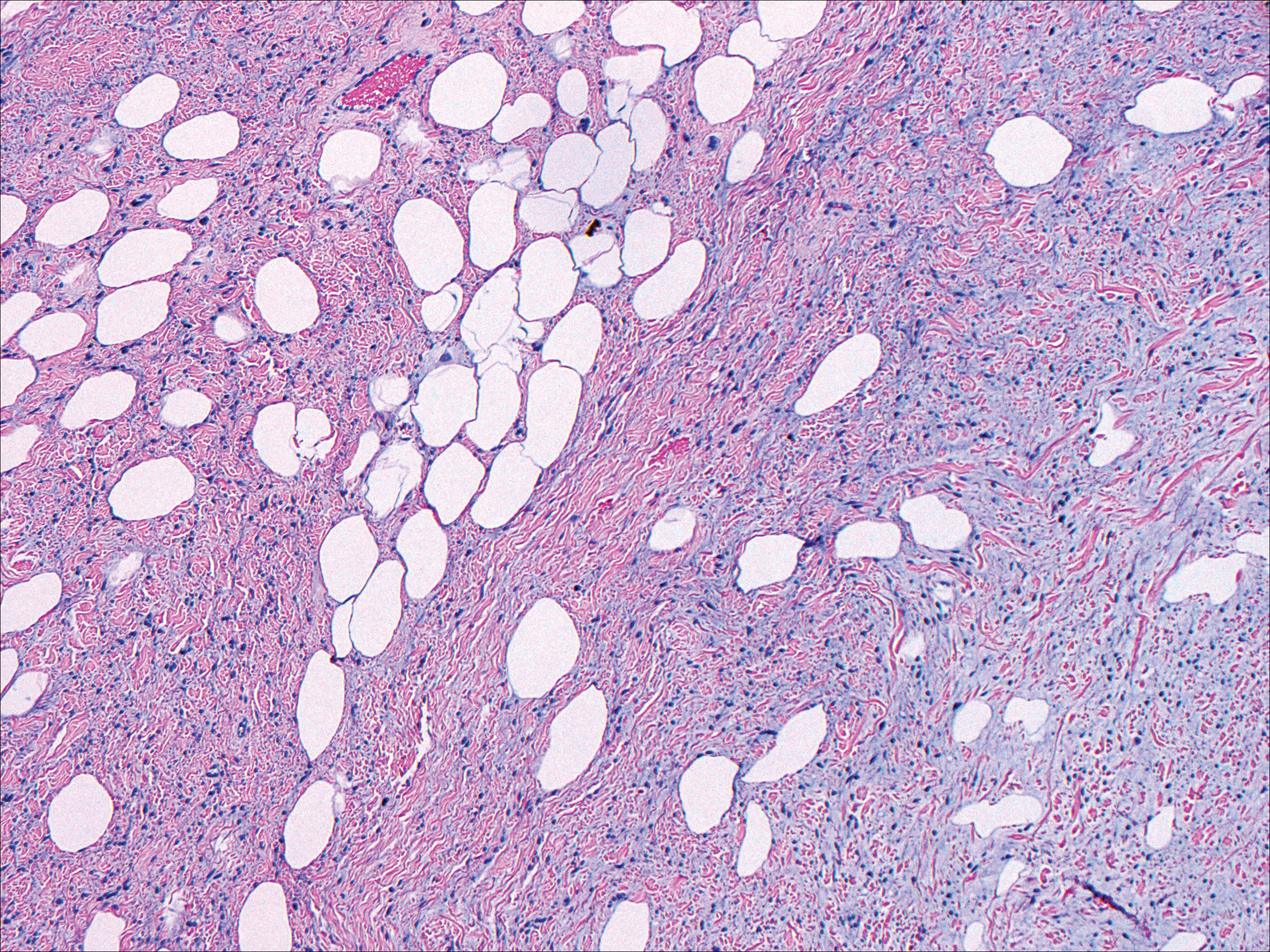

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

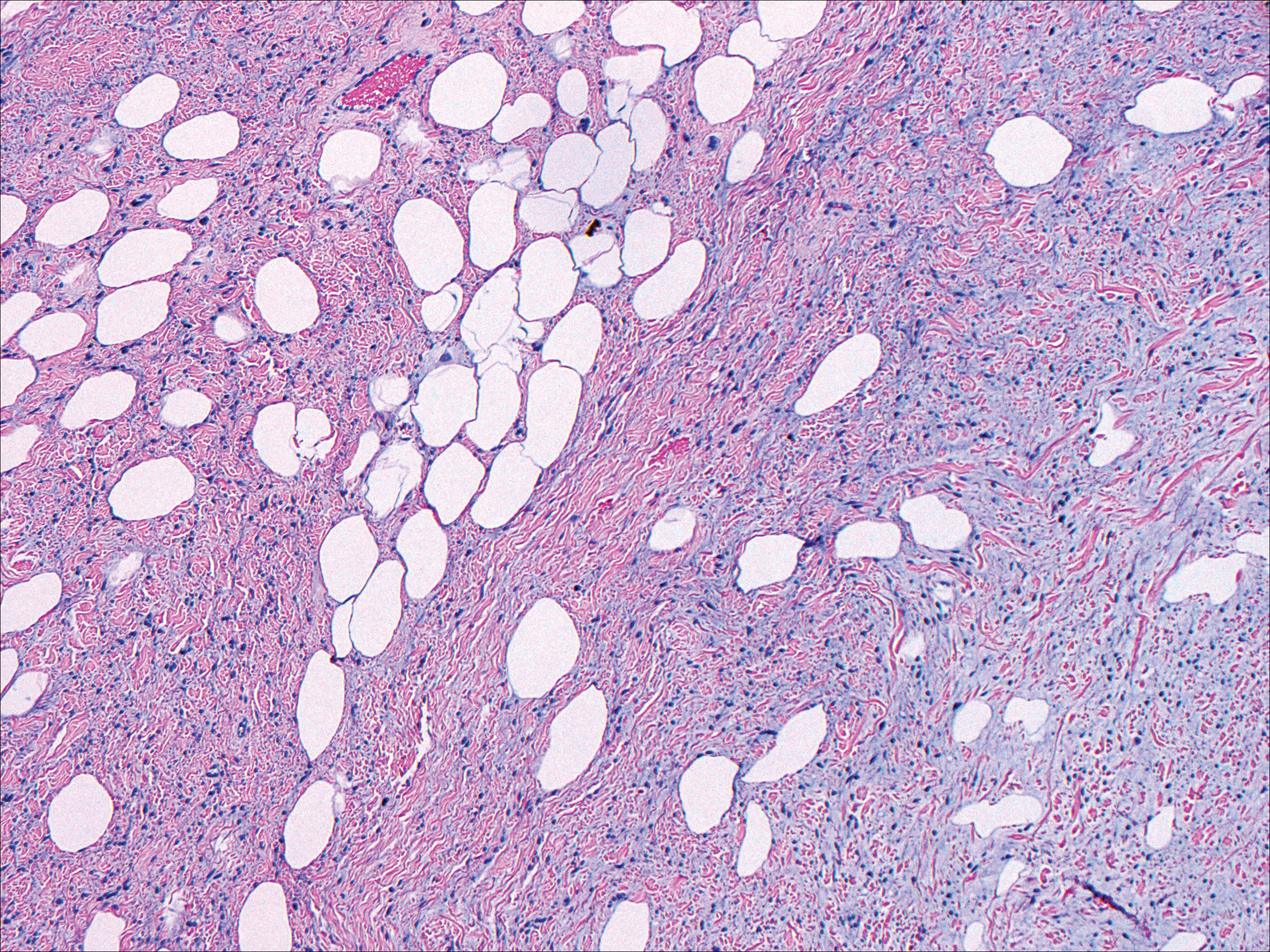

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

A 41-year-old woman presented with painful ulcers on the oral mucosa of 2 months' duration that were unresponsive to treatment with acyclovir. She had been diagnosed with a pelvic tumor a few weeks prior to the development of the mouth ulcers. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed positive IgG and complement C3 with an intercellular distribution. A biopsy of an oral lesion was performed.

Perianal Condyloma Acuminatum-like Plaque

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

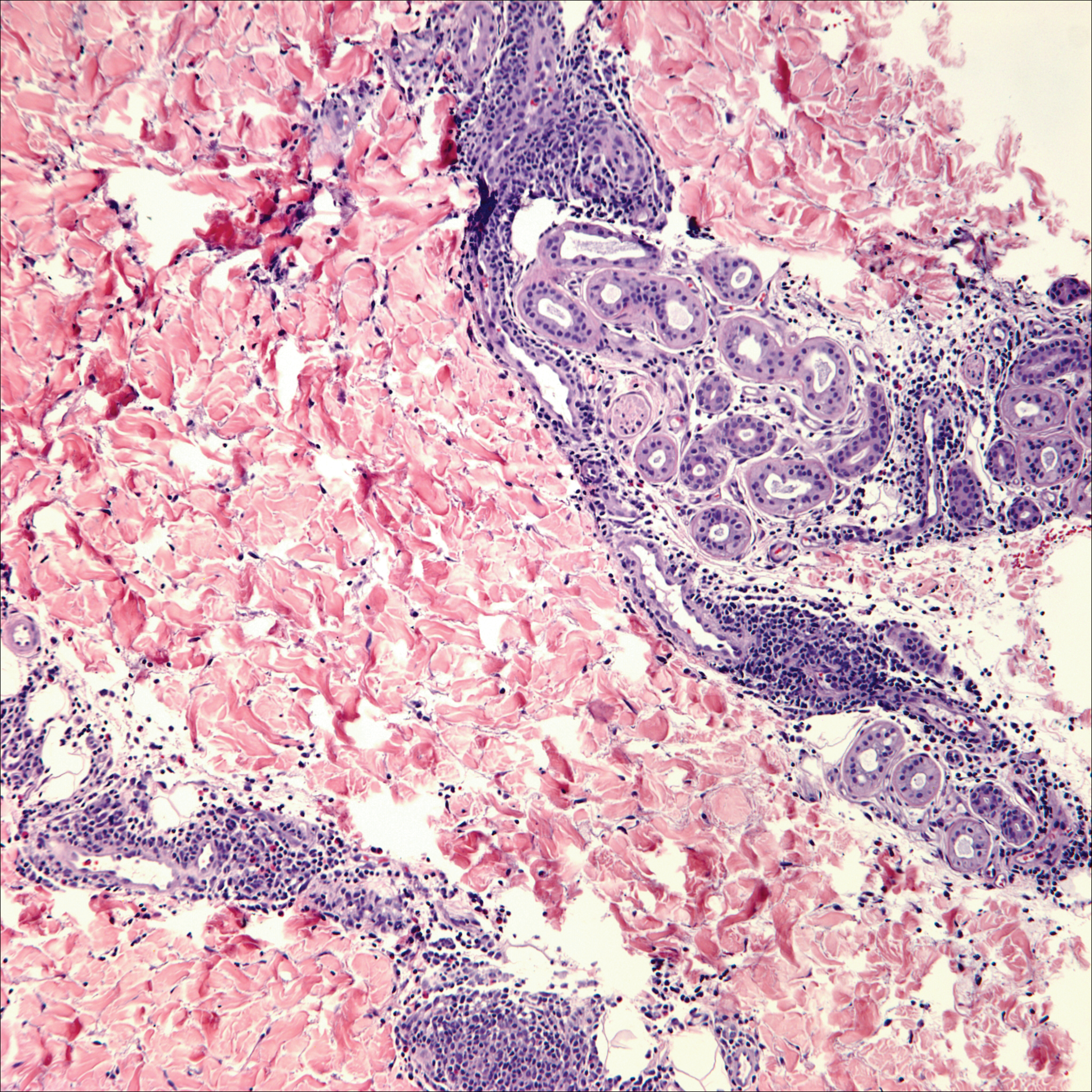

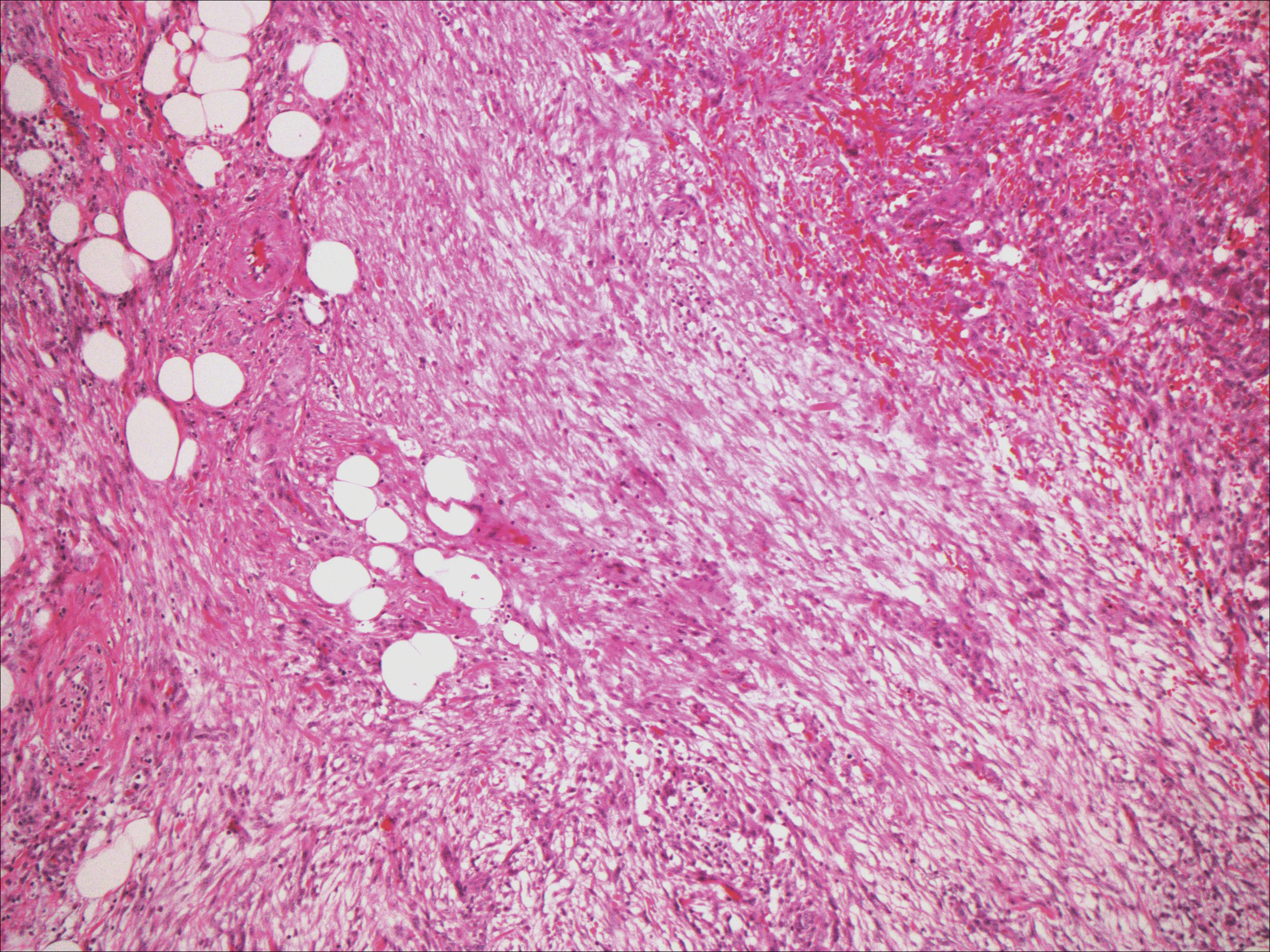

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

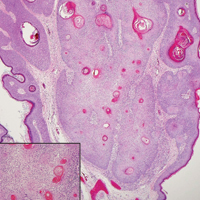

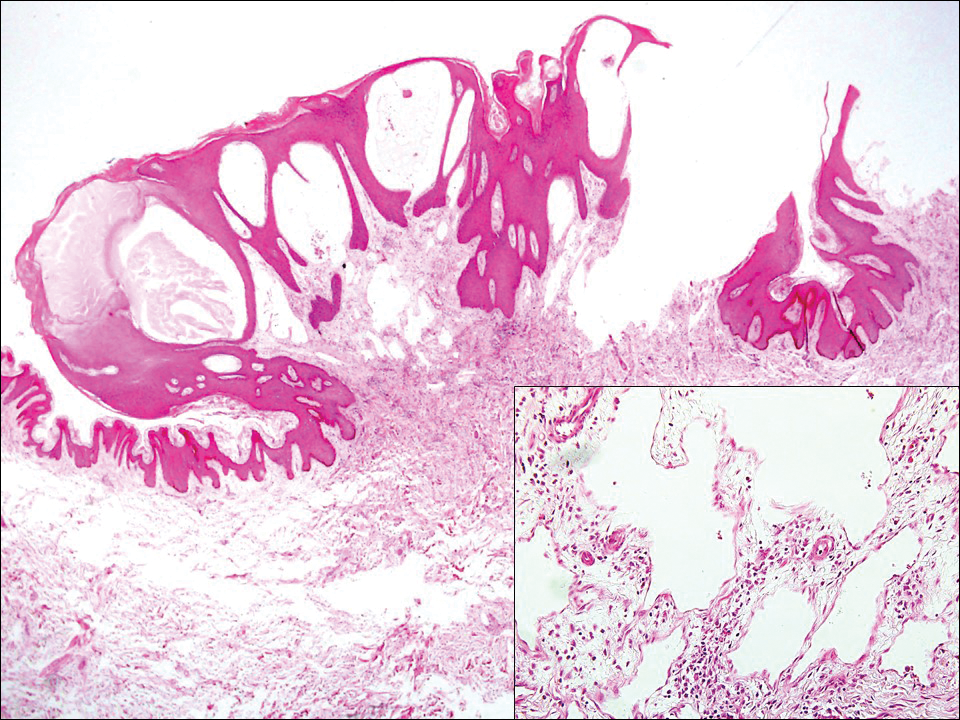

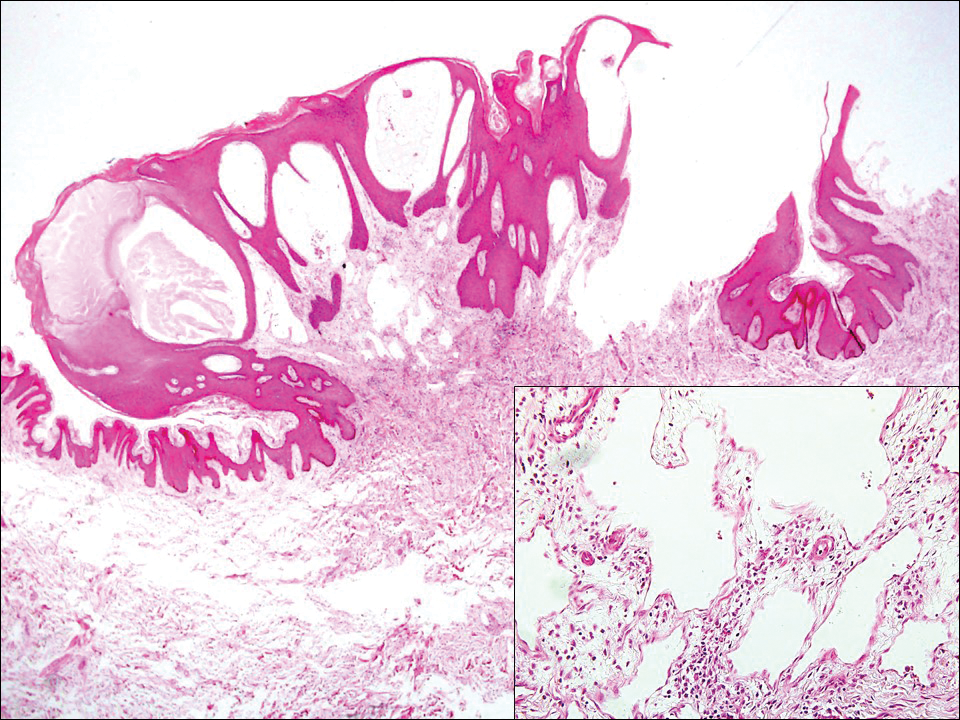

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

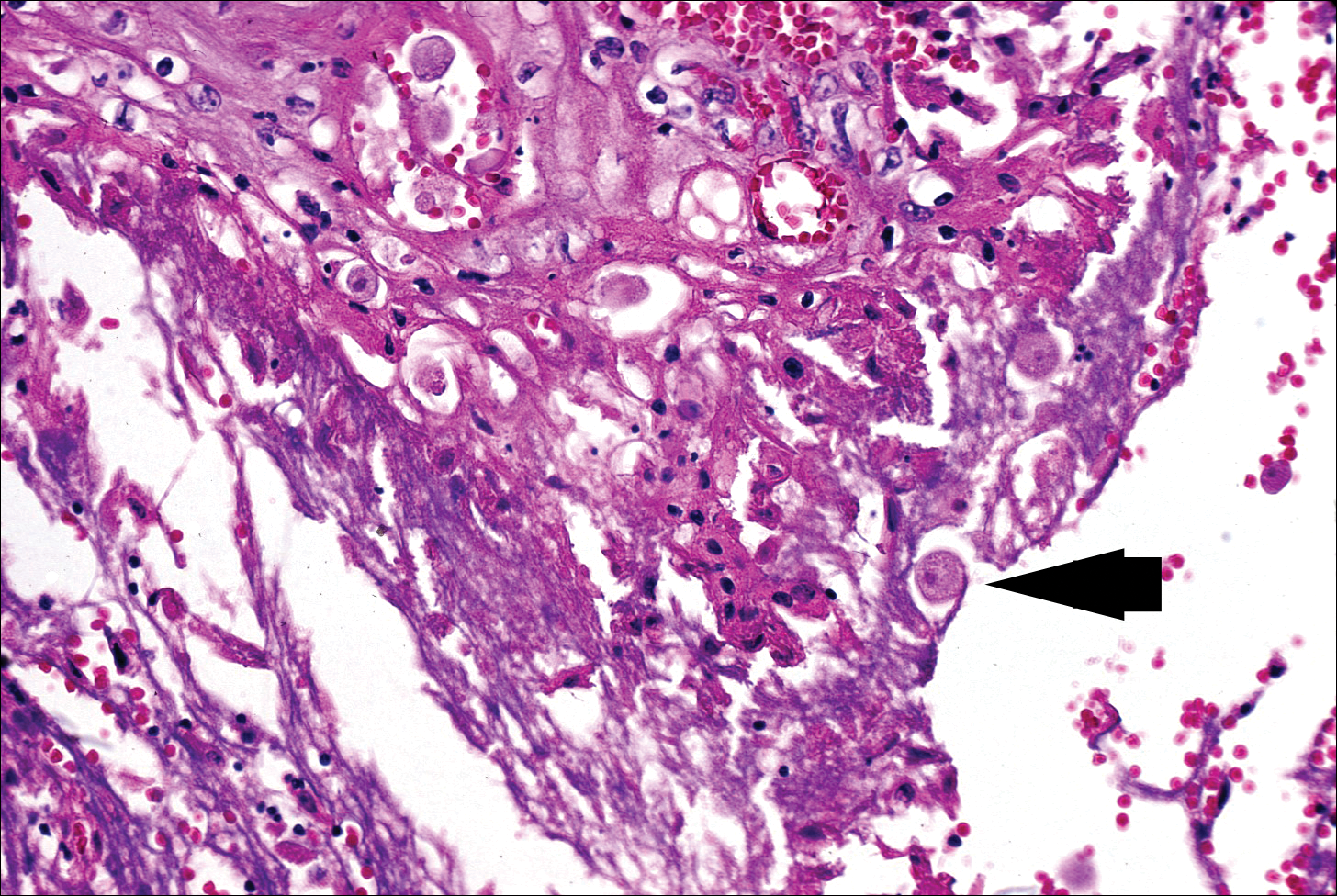

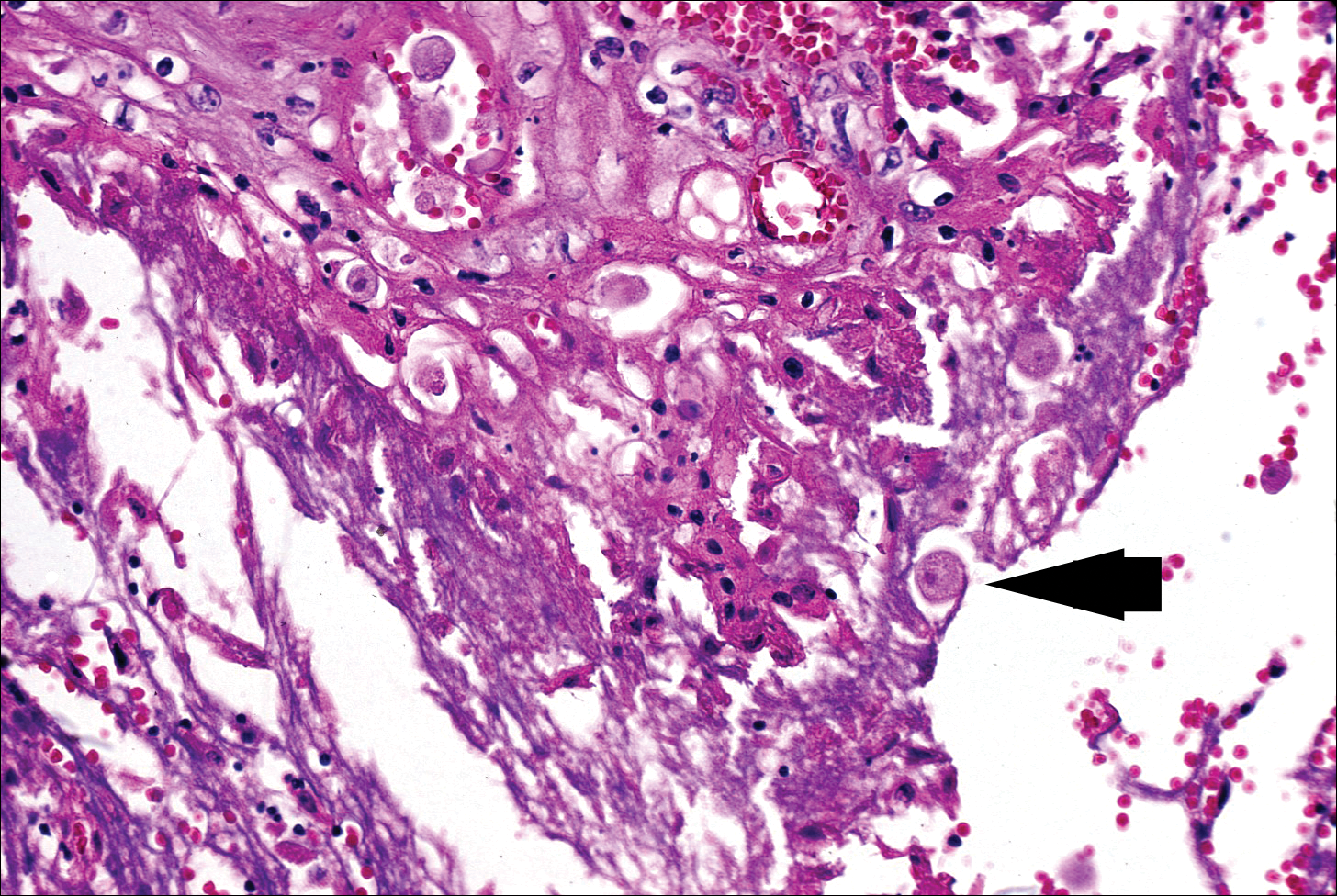

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

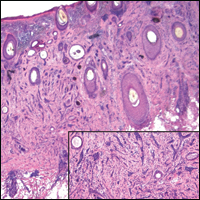

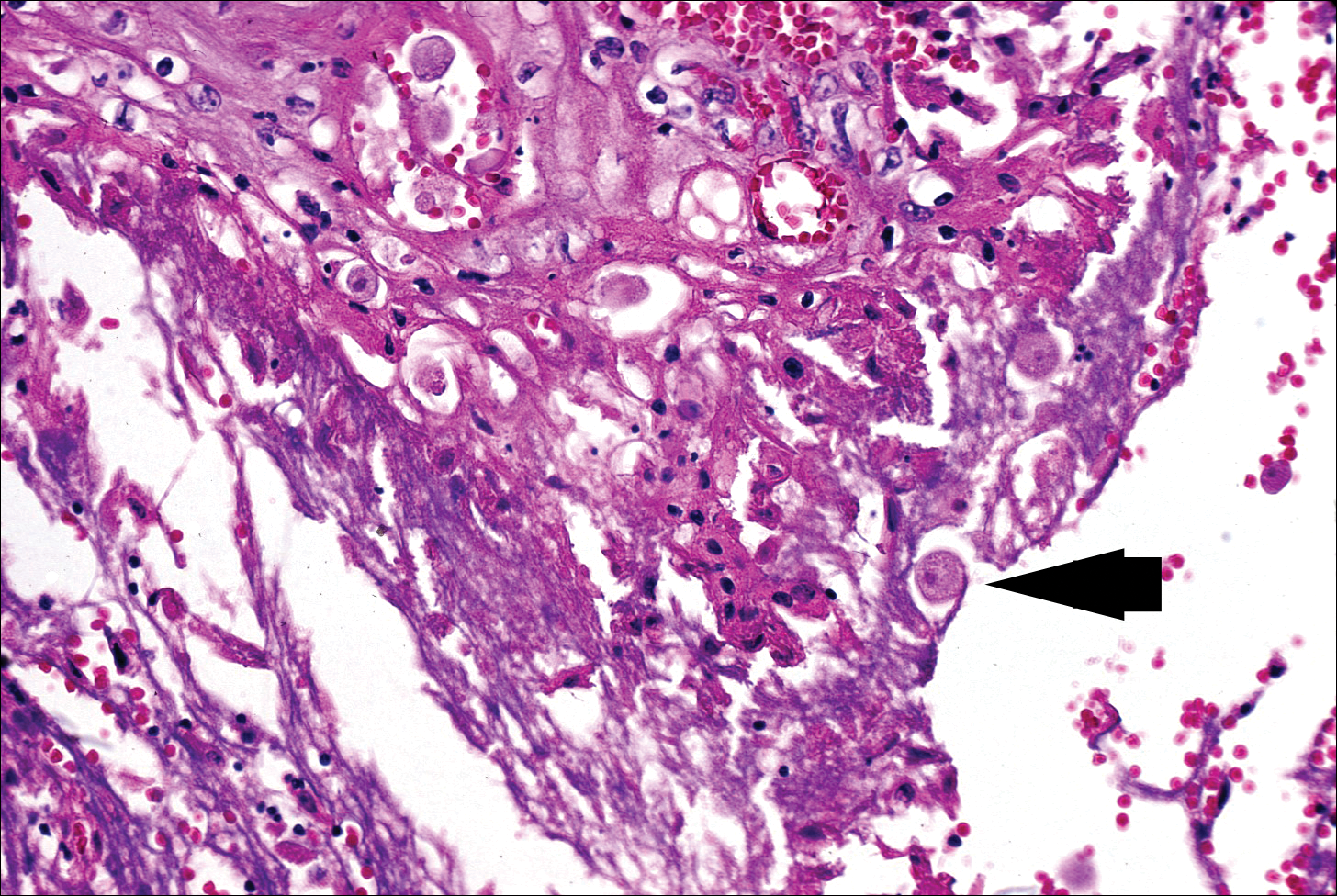

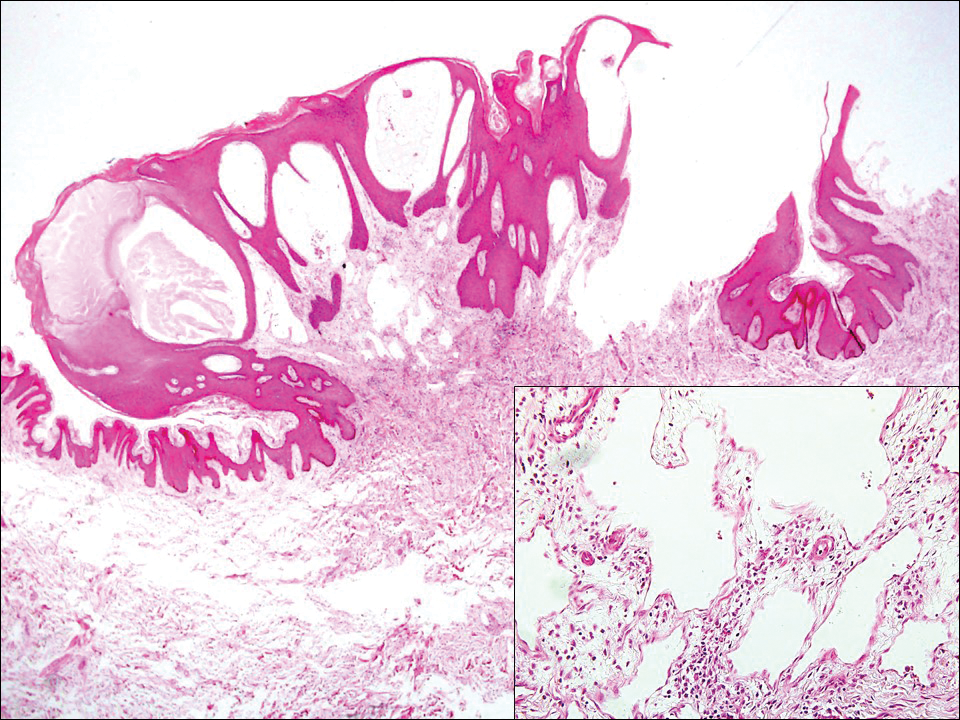

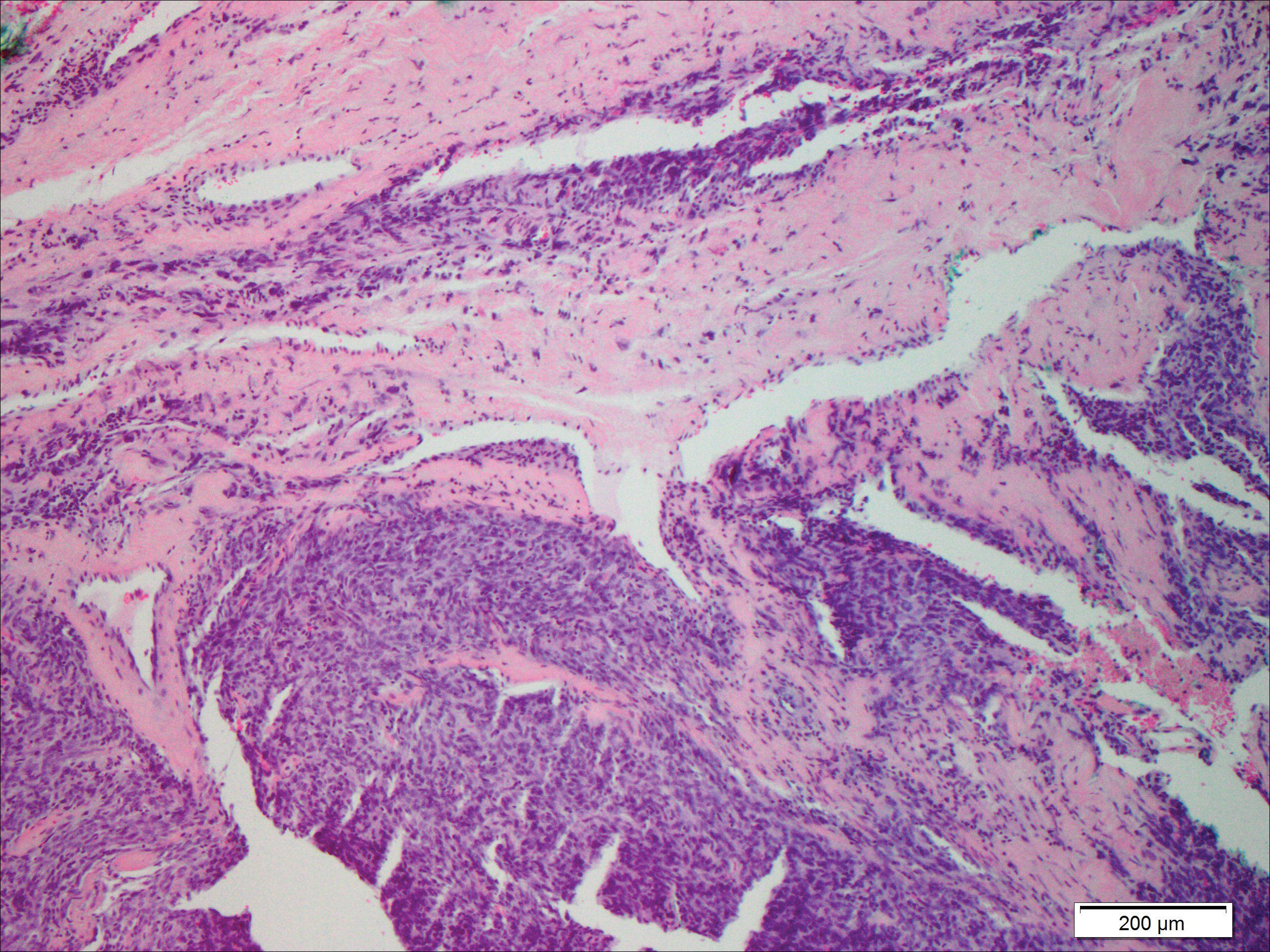

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

A 19-year-old man presented with a perianal condyloma acuminatum-like plaque of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea.

Asymptomatic Subcutaneous Nodule on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

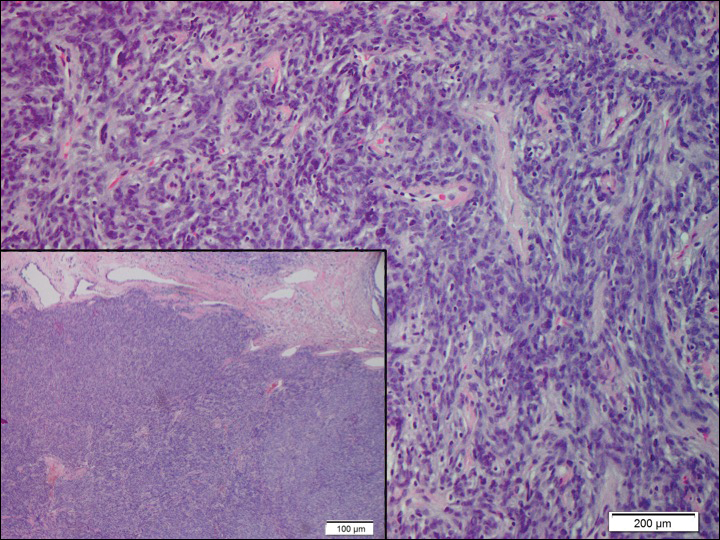

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

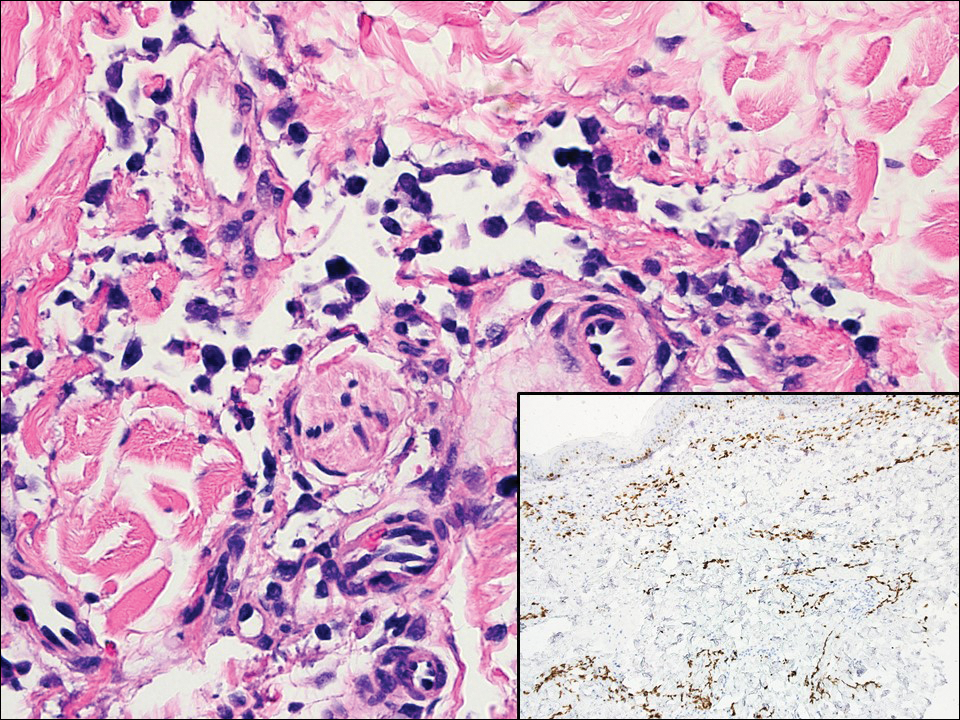

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

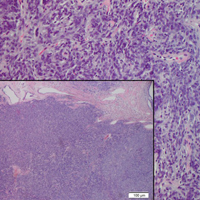

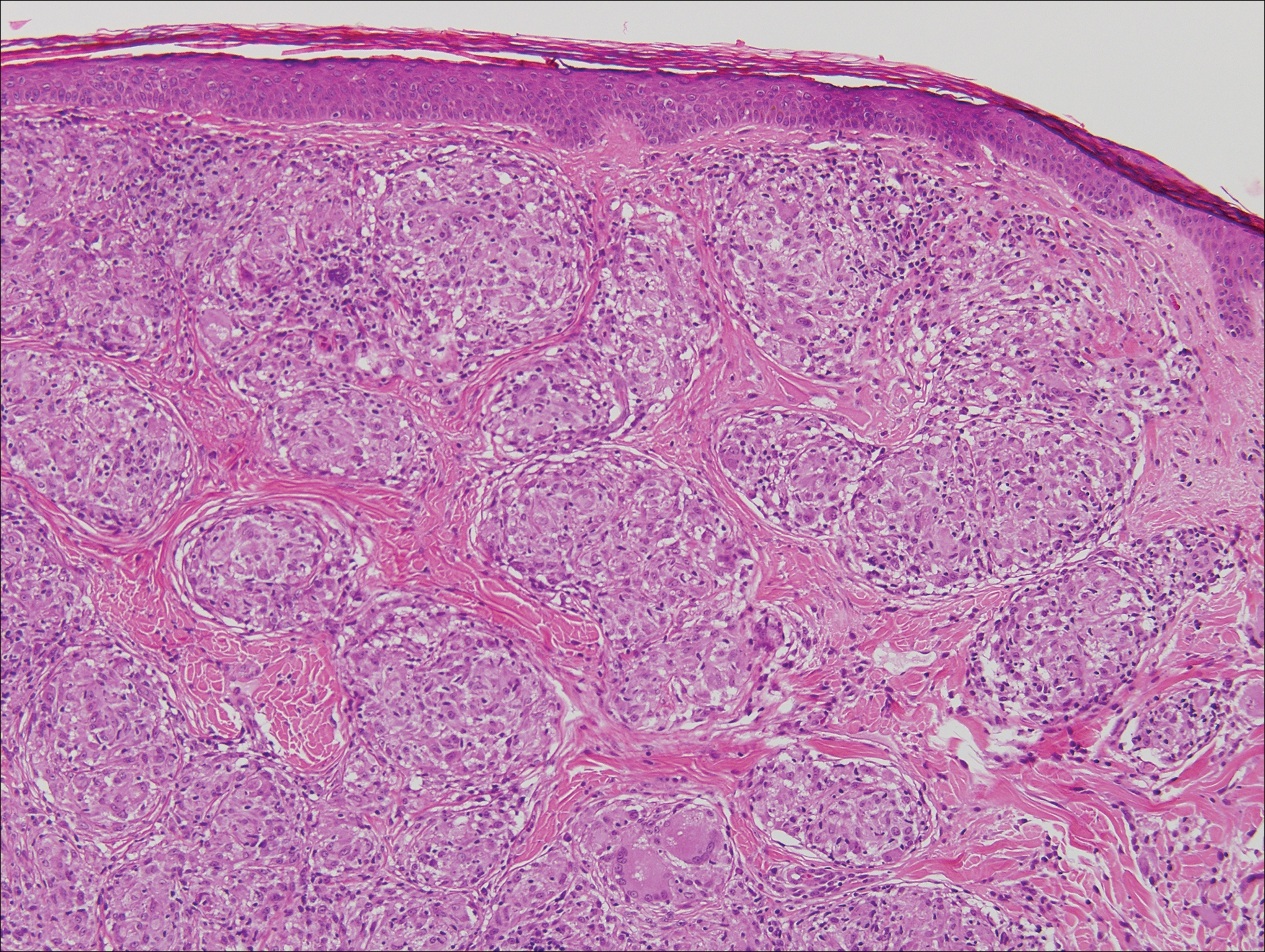

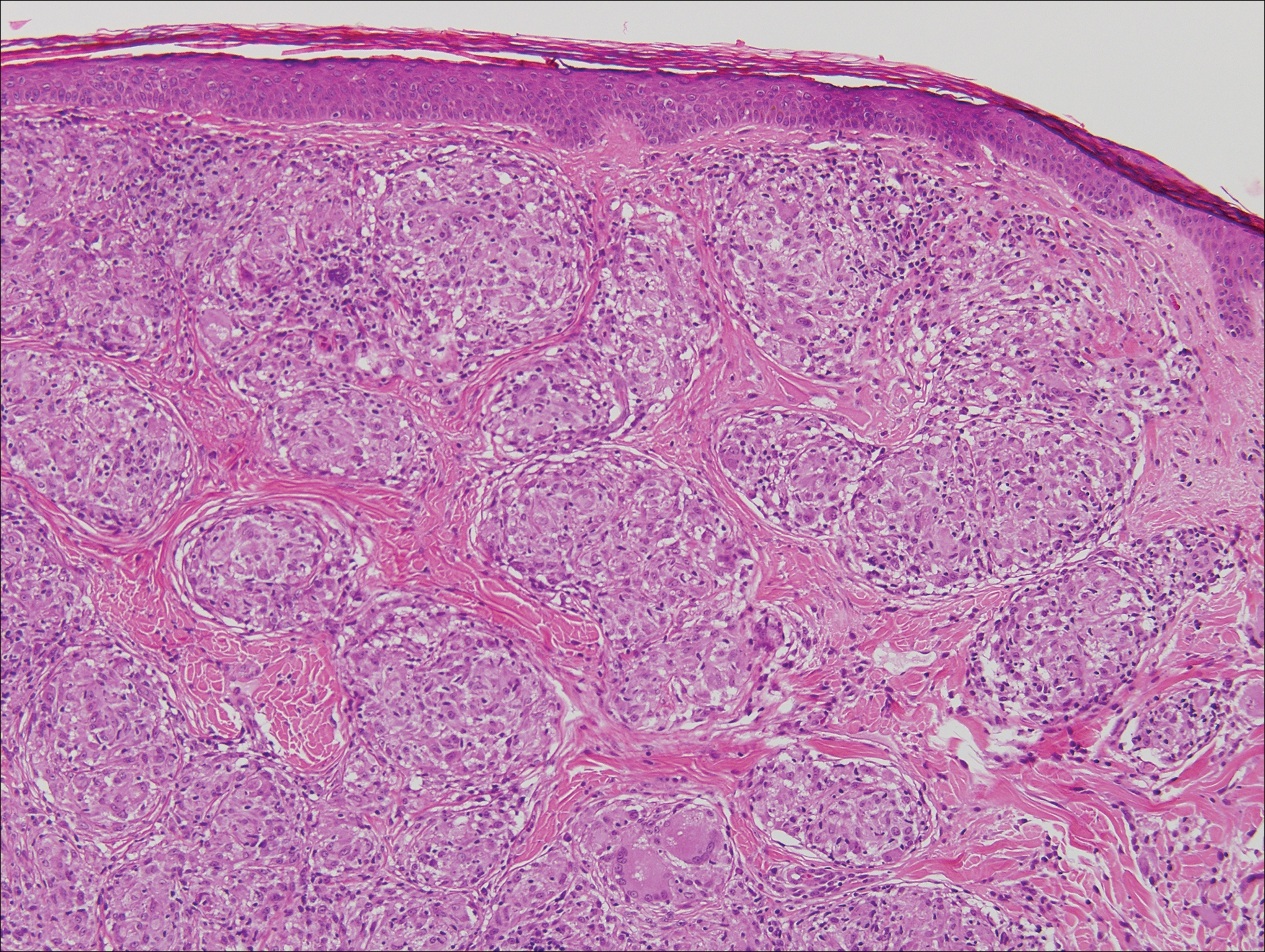

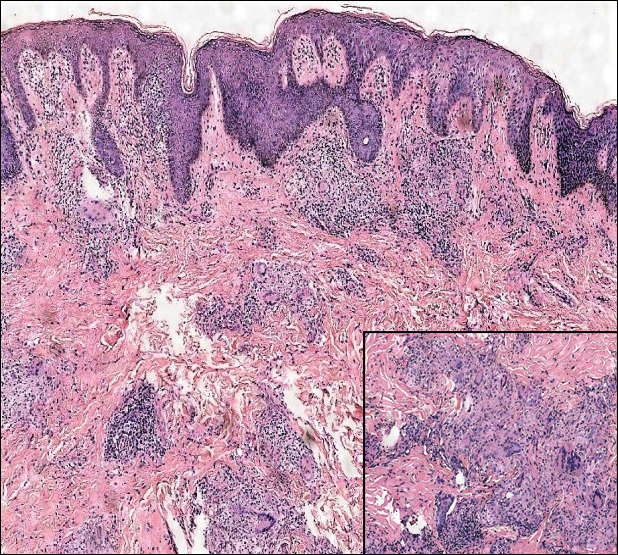

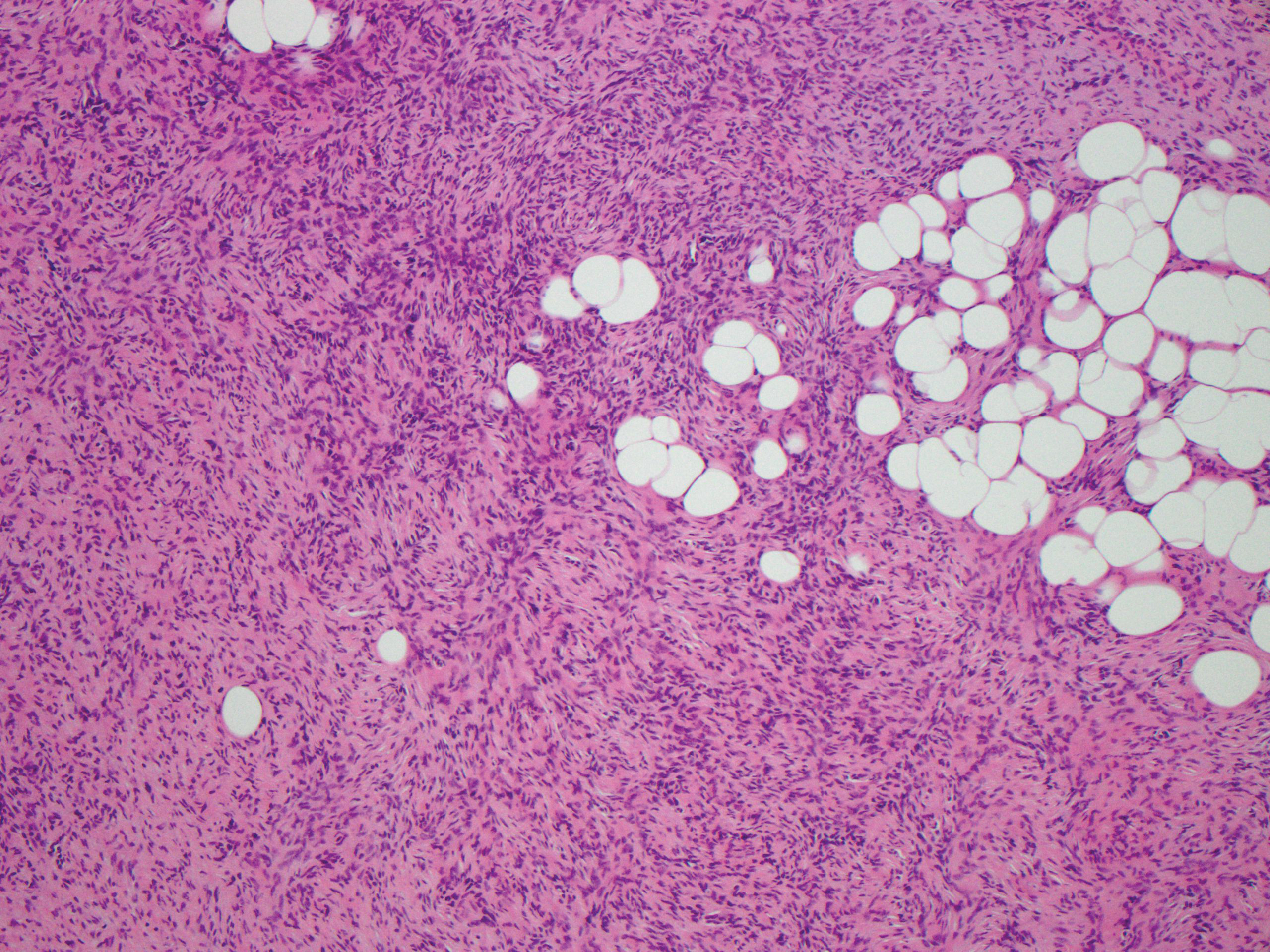

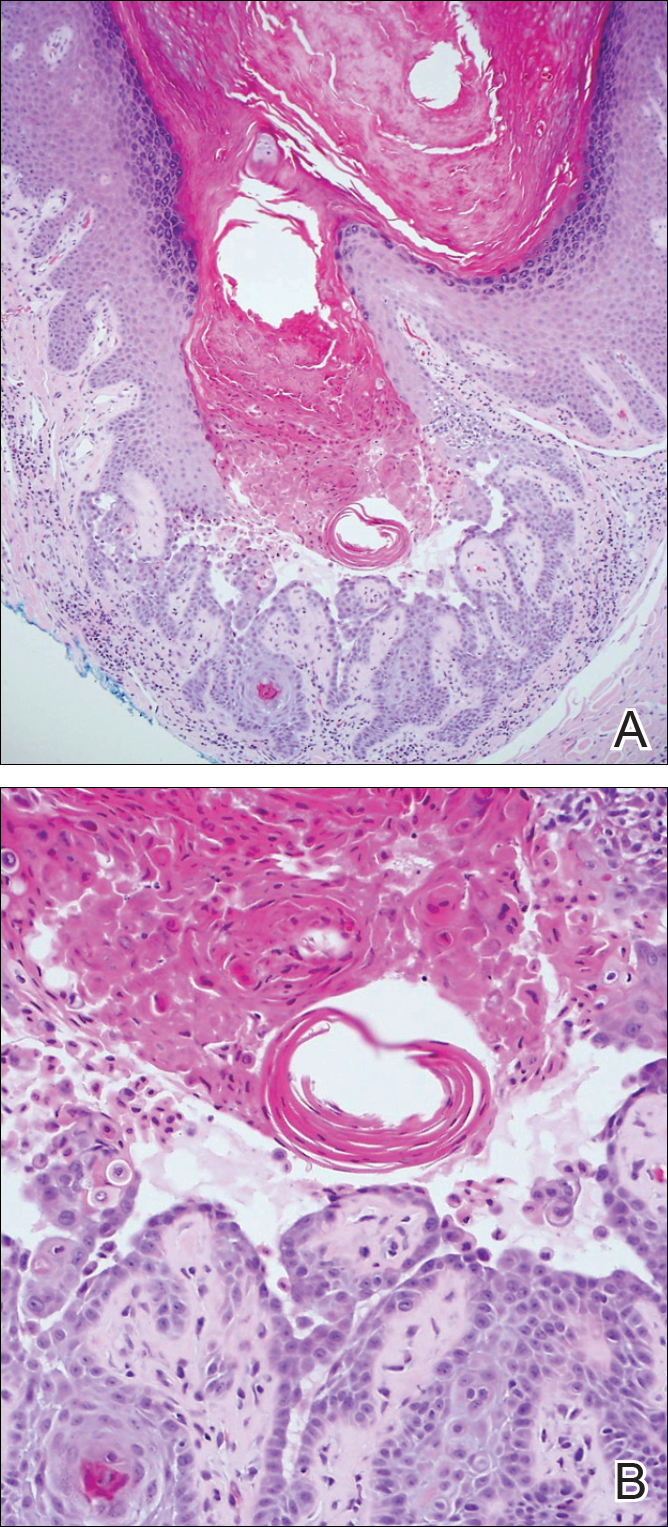

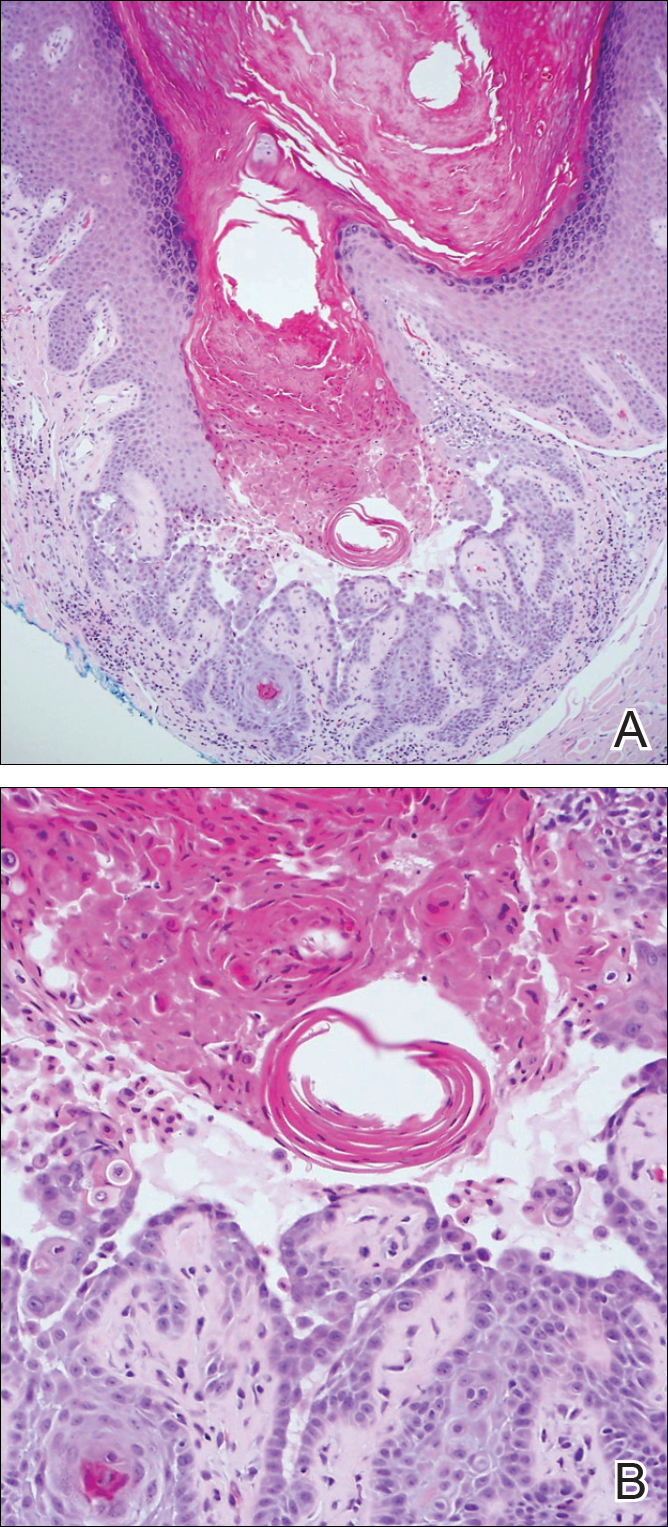

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

An 81-year-old man with history of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented with a subcutaneous nodule on the left cheek of 3 months' duration. The lesion was reportedly asymptomatic and measured 2.6×2.9 cm. A punch biopsy of the lesion was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Growing Nodule on the Arm

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma