User login

Much Ado about Hospital Quality

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

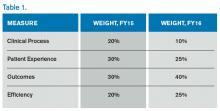

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

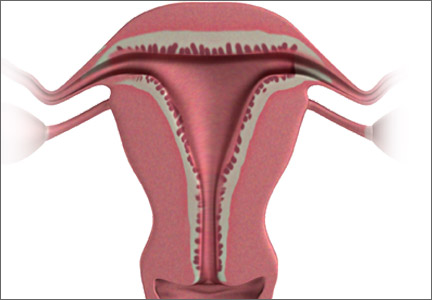

Why I prefer the vaginal route for hysterectomy

Dr. Mark Walters characterizes the vaginal approach to hysterectomy as a "solid, reliable way to do a hysterectomy." He feels that every gynecologist should know how to perform the vaginal approach and use it with properly selected patients. He explains:

- why so few hysterectomies are performed vaginally, despite this approach’s record as the safest and cheapest option

- why we should not abandon vaginal hysterectomy but “incorporate it into our practices as a best option in certain patients, as well as the most cost-effective option”

- how to decide which hysterectomy route is best for a particular patient

- what to do when the vaginal approach may not be the optimal option in a specific case

- how the need for oophorectomy or salpingectomy influences the hysterectomy decision.

Be sure to read When is the robot truly the best option for gynecologic surgery? by Tommaso Falcone, MD, and Javier Magrina, MD (Commentary, February 2015)

Dr. Mark Walters characterizes the vaginal approach to hysterectomy as a "solid, reliable way to do a hysterectomy." He feels that every gynecologist should know how to perform the vaginal approach and use it with properly selected patients. He explains:

- why so few hysterectomies are performed vaginally, despite this approach’s record as the safest and cheapest option

- why we should not abandon vaginal hysterectomy but “incorporate it into our practices as a best option in certain patients, as well as the most cost-effective option”

- how to decide which hysterectomy route is best for a particular patient

- what to do when the vaginal approach may not be the optimal option in a specific case

- how the need for oophorectomy or salpingectomy influences the hysterectomy decision.

Be sure to read When is the robot truly the best option for gynecologic surgery? by Tommaso Falcone, MD, and Javier Magrina, MD (Commentary, February 2015)

Dr. Mark Walters characterizes the vaginal approach to hysterectomy as a "solid, reliable way to do a hysterectomy." He feels that every gynecologist should know how to perform the vaginal approach and use it with properly selected patients. He explains:

- why so few hysterectomies are performed vaginally, despite this approach’s record as the safest and cheapest option

- why we should not abandon vaginal hysterectomy but “incorporate it into our practices as a best option in certain patients, as well as the most cost-effective option”

- how to decide which hysterectomy route is best for a particular patient

- what to do when the vaginal approach may not be the optimal option in a specific case

- how the need for oophorectomy or salpingectomy influences the hysterectomy decision.

Be sure to read When is the robot truly the best option for gynecologic surgery? by Tommaso Falcone, MD, and Javier Magrina, MD (Commentary, February 2015)

Detailed history, nonsedating antihistamines improve management of pediatric urticaria

ORLANDO – Acute urticaria in children is most often caused by infection, food, or medication, and a detailed history is imperative for improving the likelihood of identifying the culprit, according to Dr. Adam Friedman.

Mycoplasma is a particularly common infectious cause in children, but adenovirus, enterovirus, rotavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus also have been implicated in urticaria cases, Dr. Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

With respect to foods, ask about intake of milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, and soy. When it comes to prescription medications, antibiotics are an especially common cause.

“Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are also a very important one. If you have a patient with a history of urticaria or a pediatric patient who has a history of urticaria of the mucosa, definitely educate the parents not to give them NSAIDs,” Dr. Friedman said.

Nonimmunologic direct mast cell activation also can be a source of acute urticaria, resulting from exposure to numerous products. These include, but are not limited to, polymyxin B, radiocontrast media, opiates, muscle relaxants, salicylates, and NSAIDs, all of which can “potentially induce urticaria in almost anyone,” he said.

Identifying the cause is more likely in acute case than in chronic cases, for which the etiology is unknown about 70% of time. Regardless, the good news is that about two-thirds of cases are self-limiting; it’s the other third that poses the greatest challenge, he said.

The best bet for nailing down a diagnosis and identifying the cause is an extensive history and physical evaluation.

“Ask a million and one questions to really get to the root of it. In some cases, chronic urticaria is really a diagnosis of exclusion,” he said.

Asking the patient to keep a diary to help identify any unusual exposures just prior to the episode, and having the patient or parent take pictures of the skin are shortcuts that can help.

Extensive laboratory testing is rarely helpful, but certain tests may be warranted. New European guidelines call for erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein and blood differential testing for chronic spontaneous urticaria, but others – like liver function tests, hepatitis B, antinuclear antibody, stool, urinalysis, thyroid function, and antithyroid antibodies – should be directed by the history. A complement panel may be useful in cases involving angioedema, and allergy skin testing may be warranted if a specific trigger can be implicated, but “don’t just order for the sake of ordering,” he said.

Biopsies are not typically useful except in suspected neutrophilic urticaria, which may indicate an association with autoimmune disease, as well as offer some insight into whether dapsone treatment would be helpful over other third-line therapies. Persistent cases of urticaria (lasting over 24-48 hours in one location) may suggest urticarial vasculitis, which would warrant a biopsy.

The therapeutic approach to urticaria involves educating patients about avoiding triggers and identifying and addressing underlying conditions, and using medications that address the pathophysiology of the disease (mast cells, histamine, etc).

In children, the guidelines are generally similar to those in adults, but there is a real push to avoid systemic steroids, Dr. Friedman said, noting that the only time he uses systemic steroids is as a bridge to get to the point where other therapies are beginning to take effect.

Other key concepts for managing urticaria in children, as published in 2013 (Acta. Derm. Venereol. 2013;93:500-8), include using second-generation histamine1 antihistamines for symptom relief, avoiding first-generation H1 antihistamines (due mainly to sedation), and using other therapeutic interventions only after carefully weighing risks and benefits, as evidence in children is lacking.

Nonsedating antihistamines are preferable, as sending kids to school on sedating medications can impact learning as well as social interaction, ultimately resulting in developmental delay.

Keep in mind that standard doses of such medications often are inadequate, and it is acceptable to work up to four times the dose, even in children, he said.

Triple-drug therapy, including H1 and H2 antagonists plus leukotriene blockers may be necessary.

“This is a very complicated and still important disease. The key is history – sometimes – and climbing the therapeutic ladder. These patients are really uncomfortable, and they will love you if you get this disease under control,” Dr. Friedman said.

One thing that might provide some comfort to the patients and their parents is the fact that urticaria in children does seem to have a point of remission. Parents often fear that their children will be plagued with urticaria for life, but a recent study of 92 patients showed that the remission rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 18.5%, 54%, and 67.7% (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;71:663-8).

The median duration of chronic urticaria was 4.3 years.

“That doesn’t sound great, but in considering one’s entire lifetime, it keeps things in perspective,” he said.

Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

ORLANDO – Acute urticaria in children is most often caused by infection, food, or medication, and a detailed history is imperative for improving the likelihood of identifying the culprit, according to Dr. Adam Friedman.

Mycoplasma is a particularly common infectious cause in children, but adenovirus, enterovirus, rotavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus also have been implicated in urticaria cases, Dr. Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

With respect to foods, ask about intake of milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, and soy. When it comes to prescription medications, antibiotics are an especially common cause.

“Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are also a very important one. If you have a patient with a history of urticaria or a pediatric patient who has a history of urticaria of the mucosa, definitely educate the parents not to give them NSAIDs,” Dr. Friedman said.

Nonimmunologic direct mast cell activation also can be a source of acute urticaria, resulting from exposure to numerous products. These include, but are not limited to, polymyxin B, radiocontrast media, opiates, muscle relaxants, salicylates, and NSAIDs, all of which can “potentially induce urticaria in almost anyone,” he said.

Identifying the cause is more likely in acute case than in chronic cases, for which the etiology is unknown about 70% of time. Regardless, the good news is that about two-thirds of cases are self-limiting; it’s the other third that poses the greatest challenge, he said.

The best bet for nailing down a diagnosis and identifying the cause is an extensive history and physical evaluation.

“Ask a million and one questions to really get to the root of it. In some cases, chronic urticaria is really a diagnosis of exclusion,” he said.

Asking the patient to keep a diary to help identify any unusual exposures just prior to the episode, and having the patient or parent take pictures of the skin are shortcuts that can help.

Extensive laboratory testing is rarely helpful, but certain tests may be warranted. New European guidelines call for erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein and blood differential testing for chronic spontaneous urticaria, but others – like liver function tests, hepatitis B, antinuclear antibody, stool, urinalysis, thyroid function, and antithyroid antibodies – should be directed by the history. A complement panel may be useful in cases involving angioedema, and allergy skin testing may be warranted if a specific trigger can be implicated, but “don’t just order for the sake of ordering,” he said.

Biopsies are not typically useful except in suspected neutrophilic urticaria, which may indicate an association with autoimmune disease, as well as offer some insight into whether dapsone treatment would be helpful over other third-line therapies. Persistent cases of urticaria (lasting over 24-48 hours in one location) may suggest urticarial vasculitis, which would warrant a biopsy.

The therapeutic approach to urticaria involves educating patients about avoiding triggers and identifying and addressing underlying conditions, and using medications that address the pathophysiology of the disease (mast cells, histamine, etc).

In children, the guidelines are generally similar to those in adults, but there is a real push to avoid systemic steroids, Dr. Friedman said, noting that the only time he uses systemic steroids is as a bridge to get to the point where other therapies are beginning to take effect.

Other key concepts for managing urticaria in children, as published in 2013 (Acta. Derm. Venereol. 2013;93:500-8), include using second-generation histamine1 antihistamines for symptom relief, avoiding first-generation H1 antihistamines (due mainly to sedation), and using other therapeutic interventions only after carefully weighing risks and benefits, as evidence in children is lacking.

Nonsedating antihistamines are preferable, as sending kids to school on sedating medications can impact learning as well as social interaction, ultimately resulting in developmental delay.

Keep in mind that standard doses of such medications often are inadequate, and it is acceptable to work up to four times the dose, even in children, he said.

Triple-drug therapy, including H1 and H2 antagonists plus leukotriene blockers may be necessary.

“This is a very complicated and still important disease. The key is history – sometimes – and climbing the therapeutic ladder. These patients are really uncomfortable, and they will love you if you get this disease under control,” Dr. Friedman said.

One thing that might provide some comfort to the patients and their parents is the fact that urticaria in children does seem to have a point of remission. Parents often fear that their children will be plagued with urticaria for life, but a recent study of 92 patients showed that the remission rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 18.5%, 54%, and 67.7% (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;71:663-8).

The median duration of chronic urticaria was 4.3 years.

“That doesn’t sound great, but in considering one’s entire lifetime, it keeps things in perspective,” he said.

Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

ORLANDO – Acute urticaria in children is most often caused by infection, food, or medication, and a detailed history is imperative for improving the likelihood of identifying the culprit, according to Dr. Adam Friedman.

Mycoplasma is a particularly common infectious cause in children, but adenovirus, enterovirus, rotavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus also have been implicated in urticaria cases, Dr. Friedman, director of dermatologic research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, said at the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

With respect to foods, ask about intake of milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, and soy. When it comes to prescription medications, antibiotics are an especially common cause.

“Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are also a very important one. If you have a patient with a history of urticaria or a pediatric patient who has a history of urticaria of the mucosa, definitely educate the parents not to give them NSAIDs,” Dr. Friedman said.

Nonimmunologic direct mast cell activation also can be a source of acute urticaria, resulting from exposure to numerous products. These include, but are not limited to, polymyxin B, radiocontrast media, opiates, muscle relaxants, salicylates, and NSAIDs, all of which can “potentially induce urticaria in almost anyone,” he said.

Identifying the cause is more likely in acute case than in chronic cases, for which the etiology is unknown about 70% of time. Regardless, the good news is that about two-thirds of cases are self-limiting; it’s the other third that poses the greatest challenge, he said.

The best bet for nailing down a diagnosis and identifying the cause is an extensive history and physical evaluation.

“Ask a million and one questions to really get to the root of it. In some cases, chronic urticaria is really a diagnosis of exclusion,” he said.

Asking the patient to keep a diary to help identify any unusual exposures just prior to the episode, and having the patient or parent take pictures of the skin are shortcuts that can help.

Extensive laboratory testing is rarely helpful, but certain tests may be warranted. New European guidelines call for erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein and blood differential testing for chronic spontaneous urticaria, but others – like liver function tests, hepatitis B, antinuclear antibody, stool, urinalysis, thyroid function, and antithyroid antibodies – should be directed by the history. A complement panel may be useful in cases involving angioedema, and allergy skin testing may be warranted if a specific trigger can be implicated, but “don’t just order for the sake of ordering,” he said.

Biopsies are not typically useful except in suspected neutrophilic urticaria, which may indicate an association with autoimmune disease, as well as offer some insight into whether dapsone treatment would be helpful over other third-line therapies. Persistent cases of urticaria (lasting over 24-48 hours in one location) may suggest urticarial vasculitis, which would warrant a biopsy.

The therapeutic approach to urticaria involves educating patients about avoiding triggers and identifying and addressing underlying conditions, and using medications that address the pathophysiology of the disease (mast cells, histamine, etc).

In children, the guidelines are generally similar to those in adults, but there is a real push to avoid systemic steroids, Dr. Friedman said, noting that the only time he uses systemic steroids is as a bridge to get to the point where other therapies are beginning to take effect.

Other key concepts for managing urticaria in children, as published in 2013 (Acta. Derm. Venereol. 2013;93:500-8), include using second-generation histamine1 antihistamines for symptom relief, avoiding first-generation H1 antihistamines (due mainly to sedation), and using other therapeutic interventions only after carefully weighing risks and benefits, as evidence in children is lacking.

Nonsedating antihistamines are preferable, as sending kids to school on sedating medications can impact learning as well as social interaction, ultimately resulting in developmental delay.

Keep in mind that standard doses of such medications often are inadequate, and it is acceptable to work up to four times the dose, even in children, he said.

Triple-drug therapy, including H1 and H2 antagonists plus leukotriene blockers may be necessary.

“This is a very complicated and still important disease. The key is history – sometimes – and climbing the therapeutic ladder. These patients are really uncomfortable, and they will love you if you get this disease under control,” Dr. Friedman said.

One thing that might provide some comfort to the patients and their parents is the fact that urticaria in children does seem to have a point of remission. Parents often fear that their children will be plagued with urticaria for life, but a recent study of 92 patients showed that the remission rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 18.5%, 54%, and 67.7% (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014;71:663-8).

The median duration of chronic urticaria was 4.3 years.

“That doesn’t sound great, but in considering one’s entire lifetime, it keeps things in perspective,” he said.

Dr. Friedman reported having no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ODAC CONFERENCE

Editorial: The Changing Landscape of Emergency Medicine II: Free-Standing EDs

If an emergency department is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Until recently, FSEDs were most commonly located in rural areas lacking hospitals and primary care providers. But fueled by recent hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now appearing in previously well-served urban areas, too. In the past 6 months, three new FSEDs have opened in New York City on the sites of recently closed hospitals. What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine and emergency physicians, and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital based EDs?

Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems (see last month’s editorial, “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care”). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDS with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and RNs, provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7 – a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized emergency medicine has enthusiastically embraced, and recently endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCC’s has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I Trauma Center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Although many hospitals are less interested in offsite convenient care centers than they are in FSEDs that can supply more inpatients, EM cannot afford to ignore any of the alternatives being offered to hospital-based ED care, and should immediately embrace all of them before other specialties begin helping themselves to slices of a pie that EM has worked hard to bake to perfection for almost half a century.

If an emergency department is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Until recently, FSEDs were most commonly located in rural areas lacking hospitals and primary care providers. But fueled by recent hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now appearing in previously well-served urban areas, too. In the past 6 months, three new FSEDs have opened in New York City on the sites of recently closed hospitals. What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine and emergency physicians, and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital based EDs?

Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems (see last month’s editorial, “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care”). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDS with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and RNs, provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7 – a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized emergency medicine has enthusiastically embraced, and recently endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCC’s has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I Trauma Center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Although many hospitals are less interested in offsite convenient care centers than they are in FSEDs that can supply more inpatients, EM cannot afford to ignore any of the alternatives being offered to hospital-based ED care, and should immediately embrace all of them before other specialties begin helping themselves to slices of a pie that EM has worked hard to bake to perfection for almost half a century.

If an emergency department is considered the “front door” to the hospital, how do we regard a free-standing emergency department (FSED) with no hospital attached to it? Until recently, FSEDs were most commonly located in rural areas lacking hospitals and primary care providers. But fueled by recent hospital closures in the face of steadily increasing demands for emergency care, FSEDs are now appearing in previously well-served urban areas, too. In the past 6 months, three new FSEDs have opened in New York City on the sites of recently closed hospitals. What do FSEDs mean for emergency medicine and emergency physicians, and are they safe alternatives to traditional hospital based EDs?

Newer technologies and treatments, coupled with steadily increasing pressures to reduce inpatient stays, razor-thin hospital operating margins, and the refusal of state and local governments to bail out financially failing hospitals, have created a disconnect between the increasing need for emergency care and the decreasing number of inpatient beds.

On one end of the EM patient care spectrum, urgent care centers and retail pharmacy clinics—collectively referred to as “convenient care” centers—are rapidly proliferating to offer care to those with urgent, episodic, and relatively minor medical and surgical problems (see last month’s editorial, “Urgent Care and the Urgent Need for Care”). With little or no regulatory oversight, convenient care centers staffed by EPs, family practitioners, internists, NPs, and PAs, offer extended hour care—but not 24/7 care—to anyone with adequate health insurance or the ability to pay for the care.

On the other end of the EM patient care spectrum are the FSEDs, now divided into two types: satellite EDs of nearby hospitals, and “FS”-FSEDS with no direct hospital connections. Almost all FSEDs receive 911 ambulances, are staffed at all times by trained and certified EPs and RNs, provide acute care and stabilization consistent with the standards for hospital-based EDs, and are open 24/7 – a hallmark that distinguishes EDs from UCCs. FSEDs code and bill both for facility and provider services in the same way hospital-based EDs do. Although organized emergency medicine has enthusiastically embraced, and recently endorsed FSEDs, its position on UCC’s has been decidedly mixed.

Are FSEDs safe for patients requiring emergency care? The lack of uniform definitions and federal and state regulatory requirements make it difficult to gather and interpret meaningful clinical data on FSEDs and convenient care centers. But a well-equipped FSED, served by state-of-the-art pre- and inter-facility ambulances, and staffed by qualified EPs and RNs, should provide a safe alternative to hospital-based EDs for almost all patients in need of emergency care—especially when no hospital-based ED is available.

Specialty designations of qualifying area hospitals such as “Level I Trauma Center” will minimize but not completely eliminate bad outcomes of cases where even seconds may make the difference between life and death. In the end though, the real question may be is an FSED better than no ED at all?

Ideally, a hospital-based ED should be the epicenter of a network of both satellite convenient care centers and FSEDs, coordinating services, providing management and staffing for all parts of the network, and arranging safe, appropriate intranetwork ambulance transport.

Although many hospitals are less interested in offsite convenient care centers than they are in FSEDs that can supply more inpatients, EM cannot afford to ignore any of the alternatives being offered to hospital-based ED care, and should immediately embrace all of them before other specialties begin helping themselves to slices of a pie that EM has worked hard to bake to perfection for almost half a century.

Does a second course of antenatal corticosteroids offer benefit in the setting of preterm PROM?

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son report their secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The aim of the parent RCT was to determine whether antenatal administration of magnesium sulfate decreases the rate of cerebral palsy or death in children delivered preterm. More than 80% of the women enrolled in this RCT had preterm PROM. Of these women, 98% were given antenatal corticosteroids for fetal maturation, and 9% received two courses. This aspect of the RCT provided an opportunity for Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son to study the comparative effects of one course versus two courses of ACS in the setting of preterm PROM.

Background of the study

Concern about the declining efficacy of ACS when the interval between administration and delivery exceeds 7 days prompted several randomized trials exploring the safety and efficacy of multiple ACS courses. Multiple courses were ultimately deemed to be inadvisable because of an association with reduced birth weight and neonatal head circumference.1,2 However, the unfavorable effects of ACS on anthropometrics was observed when more than three courses were administered, leaving open the possibility of giving only one additional course when needed as a “rescue” dose. Indeed, the use of a single rescue course of ACS in women with intact membranes had a favorable impact on neonatal respiratory function in two RCTs.3,4

The best available evidence (Level 1) demonstrates that the use of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM does not increase the risk of neonatal or maternal infection even in the setting of prolonged rupture of membranes.5 However, pregnant women with preterm PROM were excluded from trials of repetitive ACS dosing because earlier observational studies had suggested that they would experience a substantially increased risk of infectious morbidity when three or more courses of ACS are given.6–8 What remained debatable on a scientific level was whether a single rescue dose of ACS in women with preterm PROM would be safe and beneficial.

Findings of the analysis

Compared with a single course of ACS, exposure to two courses did not influence the rate of neonatal sepsis or chorioamnionitis. As reassuring as that finding may be, the study found no benefit for the additional course, although it was powered to do so. There was no difference in the rates of respiratory distress syndrome between the study groups.

The findings of Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son replicate those of a subgroup analysis of women in an RCT comparing weekly and single-course ACS.9 In that study, weekly courses of ACS in women with preterm PROM did not improve neonatal outcomes beyond what was achieved with single-course therapy. Similar findings have been reported by the Cochrane database.10

Ruptured versus intact membranes: When is the benefit of ACS greater?

The improvement in neonatal outcomes observed with ACS in pregnancies complicated by preterm PROM is not as pronounced as it is in gestations with intact membranes. In preterm PROM, fetuses reportedly are stressed by the presence of intrauterine inflammation or infection, or both, which accelerates lung maturity by encouraging the secretion of endogenous corticosteroids, resulting in the production of surfactant and eliminating the potential benefit of exogenous ACS.11 This theoretical consideration has not been verified in a systematic analysis of accumulated data,5 and the administration of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM now has been shown clearly to improve neonatal outcomes.12 As Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son demonstrate, the same cannot be said about the administration of a rescue dose of ACS.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son did not address the same interaction as the parent study. The exposure of interest was ACS, an event that occurred in a manner unrelated to the randomization for magnesium sulfate administration. Therefore, the outcome data are no longer randomized in nature, and the study becomes a retrospective cohort analysis.

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son recognize the limitations of such a study, especially the lack of standardization in the intervention (exact timing of intervention or type of formulation). As with any nonrandomized experiment, the potential for unintended systematic bias is present.

This study, in particular, was subject to “survivor bias,” as reflected in the significantly different intervals between membrane rupture and delivery in the two groups.

What this evidence means for practice

We must always remain cautious about basing policy or clinical decisions on cohort studies. It has been argued that basing a change in clinical practice on the findings of subgroup analyses is a deviation from fundamental scientific truth.13 Such findings should be regarded as hypothesis testing only and considered exploratory in nature.

This study’s abstract conclusion that there is a lack of association between a second dose of ACS and neonatal sepsis should not be regarded as justification to use a rescue course of ACS in women with preterm PROM. We recommend that such a practice be avoided outside the context of an approved research protocol.

— Kathleen M. Antony, MD, and Alex C. Vidaeff, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Thom EA, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids: evaluation of safety and efficacy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(3):633–642.

2. Murphy KE, Hannah ME, Willan AR, et al; MACS Collaborative Group. Multiple Courses of Antenatal Corticosteroids for Preterm Birth (MACS): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9656):2143–2151.

3. Garite TJ, Kurtzman, Maurel K, et al. Impact of a “rescue course” of antenatal corticosteroids: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):248.e1–e9.

4. McEvoy C, Schilling D, Peters D, et al. Respiratory compliance in preterm infants after a single rescue course of antenatal steroids: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):544.e1–e9.

5. Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004454.

6. Rotmensch S, Vishne TH, Celentano C, et al. Maternal infectious morbidity following multiple courses of betamethasone. J Infect. 1999;39(1):49–54.

7. Vermillion ST, Soper DE, Chasedunn-Roark J. Neonatal sepsis after betamethasone administration to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):320–327.

8. Yang SH, Choi SJ, Roh CR, et al. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Perinat Med. 2004;32(1):42–48.

9. Lee MJ, Davies J, Guinn D, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):274–281.

10. Crowther CA, McKinlay CJ, Middleton P, Harding JE. Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD003935.

11. Lyon A. Chronic lung disease of prematurity. The role of intrauterine infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(11):798–802.

12. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM. Antenatal corticosteroids after preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(2):337–343.

13. Bailar JC. How to distort the scientific record without actually lying: truth, and the arts of science. Eur J Oncol. 2006;11(4):217–224.

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son report their secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The aim of the parent RCT was to determine whether antenatal administration of magnesium sulfate decreases the rate of cerebral palsy or death in children delivered preterm. More than 80% of the women enrolled in this RCT had preterm PROM. Of these women, 98% were given antenatal corticosteroids for fetal maturation, and 9% received two courses. This aspect of the RCT provided an opportunity for Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son to study the comparative effects of one course versus two courses of ACS in the setting of preterm PROM.

Background of the study

Concern about the declining efficacy of ACS when the interval between administration and delivery exceeds 7 days prompted several randomized trials exploring the safety and efficacy of multiple ACS courses. Multiple courses were ultimately deemed to be inadvisable because of an association with reduced birth weight and neonatal head circumference.1,2 However, the unfavorable effects of ACS on anthropometrics was observed when more than three courses were administered, leaving open the possibility of giving only one additional course when needed as a “rescue” dose. Indeed, the use of a single rescue course of ACS in women with intact membranes had a favorable impact on neonatal respiratory function in two RCTs.3,4

The best available evidence (Level 1) demonstrates that the use of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM does not increase the risk of neonatal or maternal infection even in the setting of prolonged rupture of membranes.5 However, pregnant women with preterm PROM were excluded from trials of repetitive ACS dosing because earlier observational studies had suggested that they would experience a substantially increased risk of infectious morbidity when three or more courses of ACS are given.6–8 What remained debatable on a scientific level was whether a single rescue dose of ACS in women with preterm PROM would be safe and beneficial.

Findings of the analysis

Compared with a single course of ACS, exposure to two courses did not influence the rate of neonatal sepsis or chorioamnionitis. As reassuring as that finding may be, the study found no benefit for the additional course, although it was powered to do so. There was no difference in the rates of respiratory distress syndrome between the study groups.

The findings of Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son replicate those of a subgroup analysis of women in an RCT comparing weekly and single-course ACS.9 In that study, weekly courses of ACS in women with preterm PROM did not improve neonatal outcomes beyond what was achieved with single-course therapy. Similar findings have been reported by the Cochrane database.10

Ruptured versus intact membranes: When is the benefit of ACS greater?

The improvement in neonatal outcomes observed with ACS in pregnancies complicated by preterm PROM is not as pronounced as it is in gestations with intact membranes. In preterm PROM, fetuses reportedly are stressed by the presence of intrauterine inflammation or infection, or both, which accelerates lung maturity by encouraging the secretion of endogenous corticosteroids, resulting in the production of surfactant and eliminating the potential benefit of exogenous ACS.11 This theoretical consideration has not been verified in a systematic analysis of accumulated data,5 and the administration of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM now has been shown clearly to improve neonatal outcomes.12 As Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son demonstrate, the same cannot be said about the administration of a rescue dose of ACS.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son did not address the same interaction as the parent study. The exposure of interest was ACS, an event that occurred in a manner unrelated to the randomization for magnesium sulfate administration. Therefore, the outcome data are no longer randomized in nature, and the study becomes a retrospective cohort analysis.

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son recognize the limitations of such a study, especially the lack of standardization in the intervention (exact timing of intervention or type of formulation). As with any nonrandomized experiment, the potential for unintended systematic bias is present.

This study, in particular, was subject to “survivor bias,” as reflected in the significantly different intervals between membrane rupture and delivery in the two groups.

What this evidence means for practice

We must always remain cautious about basing policy or clinical decisions on cohort studies. It has been argued that basing a change in clinical practice on the findings of subgroup analyses is a deviation from fundamental scientific truth.13 Such findings should be regarded as hypothesis testing only and considered exploratory in nature.

This study’s abstract conclusion that there is a lack of association between a second dose of ACS and neonatal sepsis should not be regarded as justification to use a rescue course of ACS in women with preterm PROM. We recommend that such a practice be avoided outside the context of an approved research protocol.

— Kathleen M. Antony, MD, and Alex C. Vidaeff, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son report their secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted through the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. The aim of the parent RCT was to determine whether antenatal administration of magnesium sulfate decreases the rate of cerebral palsy or death in children delivered preterm. More than 80% of the women enrolled in this RCT had preterm PROM. Of these women, 98% were given antenatal corticosteroids for fetal maturation, and 9% received two courses. This aspect of the RCT provided an opportunity for Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son to study the comparative effects of one course versus two courses of ACS in the setting of preterm PROM.

Background of the study

Concern about the declining efficacy of ACS when the interval between administration and delivery exceeds 7 days prompted several randomized trials exploring the safety and efficacy of multiple ACS courses. Multiple courses were ultimately deemed to be inadvisable because of an association with reduced birth weight and neonatal head circumference.1,2 However, the unfavorable effects of ACS on anthropometrics was observed when more than three courses were administered, leaving open the possibility of giving only one additional course when needed as a “rescue” dose. Indeed, the use of a single rescue course of ACS in women with intact membranes had a favorable impact on neonatal respiratory function in two RCTs.3,4

The best available evidence (Level 1) demonstrates that the use of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM does not increase the risk of neonatal or maternal infection even in the setting of prolonged rupture of membranes.5 However, pregnant women with preterm PROM were excluded from trials of repetitive ACS dosing because earlier observational studies had suggested that they would experience a substantially increased risk of infectious morbidity when three or more courses of ACS are given.6–8 What remained debatable on a scientific level was whether a single rescue dose of ACS in women with preterm PROM would be safe and beneficial.

Findings of the analysis

Compared with a single course of ACS, exposure to two courses did not influence the rate of neonatal sepsis or chorioamnionitis. As reassuring as that finding may be, the study found no benefit for the additional course, although it was powered to do so. There was no difference in the rates of respiratory distress syndrome between the study groups.

The findings of Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son replicate those of a subgroup analysis of women in an RCT comparing weekly and single-course ACS.9 In that study, weekly courses of ACS in women with preterm PROM did not improve neonatal outcomes beyond what was achieved with single-course therapy. Similar findings have been reported by the Cochrane database.10

Ruptured versus intact membranes: When is the benefit of ACS greater?

The improvement in neonatal outcomes observed with ACS in pregnancies complicated by preterm PROM is not as pronounced as it is in gestations with intact membranes. In preterm PROM, fetuses reportedly are stressed by the presence of intrauterine inflammation or infection, or both, which accelerates lung maturity by encouraging the secretion of endogenous corticosteroids, resulting in the production of surfactant and eliminating the potential benefit of exogenous ACS.11 This theoretical consideration has not been verified in a systematic analysis of accumulated data,5 and the administration of a single course of ACS in preterm PROM now has been shown clearly to improve neonatal outcomes.12 As Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son demonstrate, the same cannot be said about the administration of a rescue dose of ACS.

Strengths and limitations of the trial

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son did not address the same interaction as the parent study. The exposure of interest was ACS, an event that occurred in a manner unrelated to the randomization for magnesium sulfate administration. Therefore, the outcome data are no longer randomized in nature, and the study becomes a retrospective cohort analysis.

Gyamfi-Bannerman and Son recognize the limitations of such a study, especially the lack of standardization in the intervention (exact timing of intervention or type of formulation). As with any nonrandomized experiment, the potential for unintended systematic bias is present.

This study, in particular, was subject to “survivor bias,” as reflected in the significantly different intervals between membrane rupture and delivery in the two groups.

What this evidence means for practice

We must always remain cautious about basing policy or clinical decisions on cohort studies. It has been argued that basing a change in clinical practice on the findings of subgroup analyses is a deviation from fundamental scientific truth.13 Such findings should be regarded as hypothesis testing only and considered exploratory in nature.

This study’s abstract conclusion that there is a lack of association between a second dose of ACS and neonatal sepsis should not be regarded as justification to use a rescue course of ACS in women with preterm PROM. We recommend that such a practice be avoided outside the context of an approved research protocol.

— Kathleen M. Antony, MD, and Alex C. Vidaeff, MD, MPH

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Thom EA, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids: evaluation of safety and efficacy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(3):633–642.

2. Murphy KE, Hannah ME, Willan AR, et al; MACS Collaborative Group. Multiple Courses of Antenatal Corticosteroids for Preterm Birth (MACS): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9656):2143–2151.

3. Garite TJ, Kurtzman, Maurel K, et al. Impact of a “rescue course” of antenatal corticosteroids: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):248.e1–e9.

4. McEvoy C, Schilling D, Peters D, et al. Respiratory compliance in preterm infants after a single rescue course of antenatal steroids: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):544.e1–e9.

5. Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004454.

6. Rotmensch S, Vishne TH, Celentano C, et al. Maternal infectious morbidity following multiple courses of betamethasone. J Infect. 1999;39(1):49–54.

7. Vermillion ST, Soper DE, Chasedunn-Roark J. Neonatal sepsis after betamethasone administration to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):320–327.

8. Yang SH, Choi SJ, Roh CR, et al. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Perinat Med. 2004;32(1):42–48.

9. Lee MJ, Davies J, Guinn D, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):274–281.

10. Crowther CA, McKinlay CJ, Middleton P, Harding JE. Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD003935.

11. Lyon A. Chronic lung disease of prematurity. The role of intrauterine infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(11):798–802.

12. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM. Antenatal corticosteroids after preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(2):337–343.

13. Bailar JC. How to distort the scientific record without actually lying: truth, and the arts of science. Eur J Oncol. 2006;11(4):217–224.

1. Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Thom EA, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids: evaluation of safety and efficacy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(3):633–642.

2. Murphy KE, Hannah ME, Willan AR, et al; MACS Collaborative Group. Multiple Courses of Antenatal Corticosteroids for Preterm Birth (MACS): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9656):2143–2151.

3. Garite TJ, Kurtzman, Maurel K, et al. Impact of a “rescue course” of antenatal corticosteroids: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(3):248.e1–e9.

4. McEvoy C, Schilling D, Peters D, et al. Respiratory compliance in preterm infants after a single rescue course of antenatal steroids: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(6):544.e1–e9.

5. Roberts D, Dalziel S. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004454.

6. Rotmensch S, Vishne TH, Celentano C, et al. Maternal infectious morbidity following multiple courses of betamethasone. J Infect. 1999;39(1):49–54.

7. Vermillion ST, Soper DE, Chasedunn-Roark J. Neonatal sepsis after betamethasone administration to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):320–327.

8. Yang SH, Choi SJ, Roh CR, et al. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroid therapy in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Perinat Med. 2004;32(1):42–48.

9. Lee MJ, Davies J, Guinn D, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):274–281.

10. Crowther CA, McKinlay CJ, Middleton P, Harding JE. Repeat doses of prenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm birth for improving neonatal health outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD003935.

11. Lyon A. Chronic lung disease of prematurity. The role of intrauterine infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(11):798–802.

12. Vidaeff AC, Ramin SM. Antenatal corticosteroids after preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(2):337–343.

13. Bailar JC. How to distort the scientific record without actually lying: truth, and the arts of science. Eur J Oncol. 2006;11(4):217–224.

When is the robot truly the best option for gynecologic surgery?

When laparoscopic hysterectomy was pioneered in the late 1980s, uptake among the gynecologic surgical community was slow—despite the fact that the benefits of laparoscopy soon were evident. Compared with abdominal hysterectomy, the laparoscopic approach offered less blood loss, shorter length of hospitalization, less pain, an earlier return to activity, and improved cosmesis.

Contrast this slow start with the rapid introduction of robotic assistance in gynecologic surgery. Soon after the robot was approved for gynecology in 2005, adoption of the new technology surged. In recent years, in fact, use of the robot has grown faster than use of laparoscopy for benign hysterectomy.

At the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery (PAGS) Symposium in December 2014, Tommaso Falcone, MD, and Javier Magrina, MD, discussed the rapid adoption of the robot, its role in gynecologic surgery, and how it compares with traditional laparoscopy in a key domain—cost. When OBG Management asked these experts to defend their preferred route of hysterectomy, a lively discussion ensued.

Advantages of laparoscopy

OBG Management: What is your preferred approach for hysterectomy, and why do you consider it superior to other options?

Dr. Falcone: I’m a reproductive endocrinologist by training. In my practice at the Cleveland Clinic, I treat only benign disease—no cancer. For hysterectomy, I favor conventional laparoscopy for several reasons. First, it’s time-proven, with a long history of efficacy over the past 20 years. Second, apart from vaginal hysterectomy, it’s the most cost-effective approach to removal of the uterus in patients with benign disease.

Dr. Magrina: I have practiced as a gynecologic oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, Arizona, for the past 27 years, but I also do surgical procedures for benign disease. During my initial training, there were only two ways to perform a hysterectomy—either you made an incision in the abdomen, or you went through the vagina, which is a NOTES (natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery) procedure. Of the two, the vaginal approach is the most effective. It also is cheapest and offers the fastest recovery, but it never surpassed the abdominal approach in practice. The reason: The vaginal approach requires you to work through a small opening using specialized instruments, so it’s more difficult for the surgeon and has reduced visualization.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy—or, more specifically, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy—arrived in 1989. This approach never gained popularity, but even pure laparoscopy, which came along shortly afterward, took a long time for surgeons to adopt. A main problem was that the technology made it counterintuitive for the surgeon. With the abdominal approach, the surgeon can work with his or her hands in the abdomen, with direct visualization and tactile feedback. In laparoscopy, however, the surgeon uses instruments inside of the abdomen with visualization via a camera. As a result, laparoscopy has a much steeperlearning curve, so it never replaced abdominal hysterectomy in the way that we expected.

When robotic surgery came along, in contrast, it quickly became an enabling technology for surgeons who could not perform conventional laparoscopy, and it has overtaken laparoscopy for that reason.

Today there are four options for hysterectomy: the abdominal approach, the vaginal approach, the laparoscopic approach, and robotic assistance. I prefer robotics for complicated surgeries—primarily gynecologic cancer and advanced endometriosis. I also prefer robotics when the patient is obese.

In our practice at Mayo Clinic, Arizona, the abdominal open option essentially doesn’t exist for benign disease. If the patient has a simple problem, such as menorrhagia, which can be corrected by removing the uterus, I would choose a vaginal approach. However, if she has pain in addition to menorrhagia—particularly if it is not cyclic pain—I would prefer a laparoscopic approach.

|

|

How cost comes into play

Dr. Falcone: I think that what has influenced this discussion in recent years is the cost of medicine. Both Dr. Magrina and I trained in an era when we taught ourselves laparoscopy—as no one else was using it—and then began to try to teach others. And Dr. Magrina is correct when he describes the very slow process of absorption of the new technology. Laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed at a low frequency for a long time, and then robotic technology came along—an enabling technology, to be sure—and minimally invasive surgery took off.

Now, however, cost pressures are increasing. Let’s say the robot is the “Lamborghini” of surgical technology, as it is the most expensive of all the approaches. Until a couple of years ago, we could say, “OK, you need a Lamborghini to cross the finish line, fine. We are so wealthy, you can buy that Lamborghini. I prefer the ‘Honda’ (laparoscopy) but as long as we both cross the finish line, there’s no problem.” Now we can no longer afford the Lamborghini.

The aim is not to eliminate the robot entirely. It definitely has a role in minimally invasive surgery. But doctors who need a sophisticated enabling device to perform minimally invasive surgery now may be discouraged from using the robot, owing to its higher cost. In the future, robotics cases are more likely to be performed by surgeons who can do complex procedures at a high volume. That’s already the model at the Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic. More and more, we’re going to say, “You don’t do enough hysterectomies. Although you are performing the ones you do satisfactorily with the robot, you simply aren’t doing enough. So we’re going to move them into the hands of someone who can do them more cost-effectively.”

It’s the cost variable that has changed the game.

Dr. Magrina: I fully agree that we are in an era in which cost-effectiveness is imperative. At our institution, we have four gynecologic surgeons performing robotic, laparoscopic, and vaginal procedures. I happen to be in the low expensive end of the four, particularly in robotics, largely because I limit the number of robotic instruments—two or three, one assistant, and no manipulator. I utilize a reusable probe, and I look for ways to minimize costs. For example, instead of using an additional needle holder to suture the vaginal cuff, I use one of the robotic graspers already used in the hysterectomy part.

When surgeons begin performing robotic hysterectomy, they try multiple instruments, making the approach very expensive. As surgeons gain experience and begin to watch their costs, however, the expense comes down somewhat.

Why the robot should be reserved for high-volume surgeons

Dr. Magrina: In my opinion, if you have a basic “bread and butter” practice, I don’t think you need to have a robot. The robot should be reserved for advanced surgery. And because of fixed costs with the robot, such as maintenance, you need to perform a sufficient number of cases per year to cover those expenses. At my institution, the minimum number of robotic cases per year is about 200. Our cost for robotic surgery is 8% higher than it is for laparoscopy. If we perform fewer than 200 robotic surgeries, the difference is even greater.

Dr. Falcone: I agree with everything you’ve said, Dr. Magrina. But if you consider that about 120,000 of the 500,000 hysterectomies performed each year are done for abnormal uterine bleeding in women who have a normal uterus and no other complexity, there’s no need for the robot for these cases. A lot of places—certainly not the Cleveland Clinic or the Mayo Clinic, but other places—use the robot to remove that little uterus. That’s when conventional laparoscopy should be the preferred route.

When it comes to endometriosis, which accounts for another 20% of cases, the robot might break even because it’s the length of surgery that is important. Still, although the robot might allow most community surgeons to perform routine endometriosis cases, complex cases are another matter. The robot is an enabling device for simple cases for the average gynecologist but not for complex cases. For those cases, it requires a different skill set—sophisticated skills of retroperitoneal anatomy, which the robot doesn’t teach you. It requires experience working in a different space, which the robot doesn’t give you.