User login

Tide turns in favor of multivessel PCI in STEMI

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Recent data seem to refute the 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology class III recommendation to avoid multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention at the time of primary PCI for ST-elevation MI, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The current AHA/ACC guidelines for STEMI should be and are being reevaluated regarding clarifications for the indications and timing of non–infarct artery revascularization,” according to Dr. Holmes, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and an ACC past president.

Indeed, the ACC has already withdrawn from its ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign its former recommendation discouraging multivessel revascularization at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. The college cited “new science showing that complete revascularization of all significant blocked arteries leads to better outcomes in some heart attack patients.”

Dr. Holmes was coauthor of a meta-analysis of 4 prospective and 14 retrospective studies involving more than 40,000 patients that concluded multivessel PCI for STEMI should be discouraged, and that significant nonculprit lesions should only be treated during staged procedures (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:692-703). This meta-analysis was influential in the creation of the class III ‘don’t do it’ recommendation in the AHA/ACC guidelines. But Dr. Holmes said that in hindsight, the data included in the meta-analysis were something of a mishmash and “wound up being very hard to interpret.”

Greater clarity has been brought by two more recent randomized trials: PRAMI and CvLPRIT. Both were relatively small by cardiology standards, but they ended up showing similarly striking advantages in favor of using the STEMI hospitalization to perform preventive PCI of both the infarct-related artery and non–infarct arteries with major stenoses.

PRAMI included 465 acute STEMI patients who underwent infarct artery PCI and were then randomized to preventive PCI or infarct artery–only PCI. At a mean follow-up of 23 months, the preventive multivessel PCI group had a 65% reduction in the relative risk of the primary outcome, a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal MI, or refractory angina (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

The yet-to-be-published CvLPRIT study was presented at the 2014 European Society of Cardiology meeting in Barcelona. The multicenter study included 296 STEMI patients with angiographically established significant multivessel disease who were randomized to primary PCI of the culprit vessel only or to complete revascularization. The primary outcome, the 12-month composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, heart failure, or ischemia-driven revascularization, occurred in 10% of the complete revascularization group, compared with 21.2% of patients assigned to culprit artery–only PCI.

Also at the ESC conference, CvLPRIT investigator Dr. Anthony Gershlick of the University of Leicester (England) presented a meta-analysis combining the weighted results of PRAMI, CvLPRIT, and two earlier randomized trials: HELP AMI (Int. J. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 2004;6:128-33) and an Italian trial (Heart 2010;96:662-7). The results strongly favored multivessel PCI, with a 45% reduction in mortality and a 61% decrease in recurrent MI, compared with culprit vessel–only PCI at the time of admission for STEMI.

“Maybe there aren’t any innocent bystanders,” commented Dr. Holmes. “Maybe if you have somebody who has multivessel disease and you see something you think might be an innocent bystander but is a significant lesion, maybe it’s not so innocent. Maybe by treating them all at the time of the initial intervention the patient is going to do better.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Recent data seem to refute the 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology class III recommendation to avoid multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention at the time of primary PCI for ST-elevation MI, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The current AHA/ACC guidelines for STEMI should be and are being reevaluated regarding clarifications for the indications and timing of non–infarct artery revascularization,” according to Dr. Holmes, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and an ACC past president.

Indeed, the ACC has already withdrawn from its ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign its former recommendation discouraging multivessel revascularization at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. The college cited “new science showing that complete revascularization of all significant blocked arteries leads to better outcomes in some heart attack patients.”

Dr. Holmes was coauthor of a meta-analysis of 4 prospective and 14 retrospective studies involving more than 40,000 patients that concluded multivessel PCI for STEMI should be discouraged, and that significant nonculprit lesions should only be treated during staged procedures (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:692-703). This meta-analysis was influential in the creation of the class III ‘don’t do it’ recommendation in the AHA/ACC guidelines. But Dr. Holmes said that in hindsight, the data included in the meta-analysis were something of a mishmash and “wound up being very hard to interpret.”

Greater clarity has been brought by two more recent randomized trials: PRAMI and CvLPRIT. Both were relatively small by cardiology standards, but they ended up showing similarly striking advantages in favor of using the STEMI hospitalization to perform preventive PCI of both the infarct-related artery and non–infarct arteries with major stenoses.

PRAMI included 465 acute STEMI patients who underwent infarct artery PCI and were then randomized to preventive PCI or infarct artery–only PCI. At a mean follow-up of 23 months, the preventive multivessel PCI group had a 65% reduction in the relative risk of the primary outcome, a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal MI, or refractory angina (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

The yet-to-be-published CvLPRIT study was presented at the 2014 European Society of Cardiology meeting in Barcelona. The multicenter study included 296 STEMI patients with angiographically established significant multivessel disease who were randomized to primary PCI of the culprit vessel only or to complete revascularization. The primary outcome, the 12-month composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, heart failure, or ischemia-driven revascularization, occurred in 10% of the complete revascularization group, compared with 21.2% of patients assigned to culprit artery–only PCI.

Also at the ESC conference, CvLPRIT investigator Dr. Anthony Gershlick of the University of Leicester (England) presented a meta-analysis combining the weighted results of PRAMI, CvLPRIT, and two earlier randomized trials: HELP AMI (Int. J. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 2004;6:128-33) and an Italian trial (Heart 2010;96:662-7). The results strongly favored multivessel PCI, with a 45% reduction in mortality and a 61% decrease in recurrent MI, compared with culprit vessel–only PCI at the time of admission for STEMI.

“Maybe there aren’t any innocent bystanders,” commented Dr. Holmes. “Maybe if you have somebody who has multivessel disease and you see something you think might be an innocent bystander but is a significant lesion, maybe it’s not so innocent. Maybe by treating them all at the time of the initial intervention the patient is going to do better.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Recent data seem to refute the 2013 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology class III recommendation to avoid multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention at the time of primary PCI for ST-elevation MI, Dr. David R. Holmes Jr. observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The current AHA/ACC guidelines for STEMI should be and are being reevaluated regarding clarifications for the indications and timing of non–infarct artery revascularization,” according to Dr. Holmes, a cardiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and an ACC past president.

Indeed, the ACC has already withdrawn from its ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign its former recommendation discouraging multivessel revascularization at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. The college cited “new science showing that complete revascularization of all significant blocked arteries leads to better outcomes in some heart attack patients.”

Dr. Holmes was coauthor of a meta-analysis of 4 prospective and 14 retrospective studies involving more than 40,000 patients that concluded multivessel PCI for STEMI should be discouraged, and that significant nonculprit lesions should only be treated during staged procedures (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:692-703). This meta-analysis was influential in the creation of the class III ‘don’t do it’ recommendation in the AHA/ACC guidelines. But Dr. Holmes said that in hindsight, the data included in the meta-analysis were something of a mishmash and “wound up being very hard to interpret.”

Greater clarity has been brought by two more recent randomized trials: PRAMI and CvLPRIT. Both were relatively small by cardiology standards, but they ended up showing similarly striking advantages in favor of using the STEMI hospitalization to perform preventive PCI of both the infarct-related artery and non–infarct arteries with major stenoses.

PRAMI included 465 acute STEMI patients who underwent infarct artery PCI and were then randomized to preventive PCI or infarct artery–only PCI. At a mean follow-up of 23 months, the preventive multivessel PCI group had a 65% reduction in the relative risk of the primary outcome, a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal MI, or refractory angina (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1115-23).

The yet-to-be-published CvLPRIT study was presented at the 2014 European Society of Cardiology meeting in Barcelona. The multicenter study included 296 STEMI patients with angiographically established significant multivessel disease who were randomized to primary PCI of the culprit vessel only or to complete revascularization. The primary outcome, the 12-month composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, heart failure, or ischemia-driven revascularization, occurred in 10% of the complete revascularization group, compared with 21.2% of patients assigned to culprit artery–only PCI.

Also at the ESC conference, CvLPRIT investigator Dr. Anthony Gershlick of the University of Leicester (England) presented a meta-analysis combining the weighted results of PRAMI, CvLPRIT, and two earlier randomized trials: HELP AMI (Int. J. Cardiovasc. Intervent. 2004;6:128-33) and an Italian trial (Heart 2010;96:662-7). The results strongly favored multivessel PCI, with a 45% reduction in mortality and a 61% decrease in recurrent MI, compared with culprit vessel–only PCI at the time of admission for STEMI.

“Maybe there aren’t any innocent bystanders,” commented Dr. Holmes. “Maybe if you have somebody who has multivessel disease and you see something you think might be an innocent bystander but is a significant lesion, maybe it’s not so innocent. Maybe by treating them all at the time of the initial intervention the patient is going to do better.”

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Emergency department holds key to early readmissions for heart failure

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Under intense fiscal pressure to curb early hospital readmissions for heart failure, cardiologists and hospital administrators are taking a hard look at the traditional role of the emergency department as the point of triage for patients with decompensated heart failure.

“Alternatives to the emergency department for ambulatory triage and intervention are essential,” Dr. Akshay Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“Traditionally, when our patients become decompensated, we send them from our office or clinic to the ED. And 80%-90% of those who present to the ED with the diagnosis of heart failure are admitted to the hospital. So this means that the ED is a pretty ineffective triage point for heart failure patients. Most ED staff are concerned about ambulatory follow-up and feel it’s safer to follow patients in the hospital. The message here is we need a more robust ambulatory framework to manage patients with milder decompensation so they don’t all need to come into the hospital,” said Dr. Desai of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Hospital admission is of questionable value for a large fraction of decompensating heart failure patients. After all, not that much happens to them in the hospital that couldn’t take place in a less costly setting.

“For the most part, our patients in the hospital for decompensated heart failure get IV diuretics, with an average weight loss of about 4 kg. Surveillance is typically once- or twice-daily laboratory tests and a bedside clinical visit by a physician at 7:30 in the morning. Few patients get much else. There’s little diagnostic testing, few other therapies that require intensive monitoring, and most patients feel a little better by their first day in the hospital,” he said.

This suggests the need for what he called “an evolved model of heart failure care” in which the ED is replaced as the point of service by some form of ambulatory center that can serve as a buffer limiting the number of patients who need to come into the hospital.

“It could be a home-based strategy of IV diuretic administration, a clinic-based strategy of outpatient diuretic administration, or an observation unit based in the ED. All of these are now being tested in various models across the country as alternatives to help manage the readmission problem, and also to make life better for our patients, who’d prefer not to be in the hospital if they could be managed in other ways,” Dr. Desai continued.

Reducing 30-day readmission rates after a hospitalization for heart failure is seen by health policy makers as an opportunity to simultaneously improve care and reduce costs. But studies show only about half of readmissions in patients with heart failure are cardiovascular related, just half of those cardiovascular readmissions are heart failure related, and only about 30% of heart failure readmissions are truly preventable. However, wide variation exists across the country in risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rates, suggesting there is an opportunity for improvement in outlier hospitals.

Numerous factors have been linked to high heart failure readmission rates, including patient sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and serum markers of heart failure severity. One underappreciated factor, in Dr. Desai’s view, is that readmission rates are significantly higher in hospitals that are financially and clinically resource poor, as shown in a Harvard School of Public Health analysis of Medicare claims data for more than 900,000 heart failure discharges. These resource-poor hospitals provide care for underserved populations, and they are experiencing a disproportionate burden of the financial penalties imposed for early readmission.

“As we seek to improve care for patients with heart failure, we should ensure that penalties for poor performance do not worsen disparities in quality of care,” according to the Harvard investigators (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2011;4:53-9).

Dr. Desai reported serving as a consultant to 5AM Ventures, AtCor Medical, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Under intense fiscal pressure to curb early hospital readmissions for heart failure, cardiologists and hospital administrators are taking a hard look at the traditional role of the emergency department as the point of triage for patients with decompensated heart failure.

“Alternatives to the emergency department for ambulatory triage and intervention are essential,” Dr. Akshay Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“Traditionally, when our patients become decompensated, we send them from our office or clinic to the ED. And 80%-90% of those who present to the ED with the diagnosis of heart failure are admitted to the hospital. So this means that the ED is a pretty ineffective triage point for heart failure patients. Most ED staff are concerned about ambulatory follow-up and feel it’s safer to follow patients in the hospital. The message here is we need a more robust ambulatory framework to manage patients with milder decompensation so they don’t all need to come into the hospital,” said Dr. Desai of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Hospital admission is of questionable value for a large fraction of decompensating heart failure patients. After all, not that much happens to them in the hospital that couldn’t take place in a less costly setting.

“For the most part, our patients in the hospital for decompensated heart failure get IV diuretics, with an average weight loss of about 4 kg. Surveillance is typically once- or twice-daily laboratory tests and a bedside clinical visit by a physician at 7:30 in the morning. Few patients get much else. There’s little diagnostic testing, few other therapies that require intensive monitoring, and most patients feel a little better by their first day in the hospital,” he said.

This suggests the need for what he called “an evolved model of heart failure care” in which the ED is replaced as the point of service by some form of ambulatory center that can serve as a buffer limiting the number of patients who need to come into the hospital.

“It could be a home-based strategy of IV diuretic administration, a clinic-based strategy of outpatient diuretic administration, or an observation unit based in the ED. All of these are now being tested in various models across the country as alternatives to help manage the readmission problem, and also to make life better for our patients, who’d prefer not to be in the hospital if they could be managed in other ways,” Dr. Desai continued.

Reducing 30-day readmission rates after a hospitalization for heart failure is seen by health policy makers as an opportunity to simultaneously improve care and reduce costs. But studies show only about half of readmissions in patients with heart failure are cardiovascular related, just half of those cardiovascular readmissions are heart failure related, and only about 30% of heart failure readmissions are truly preventable. However, wide variation exists across the country in risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rates, suggesting there is an opportunity for improvement in outlier hospitals.

Numerous factors have been linked to high heart failure readmission rates, including patient sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and serum markers of heart failure severity. One underappreciated factor, in Dr. Desai’s view, is that readmission rates are significantly higher in hospitals that are financially and clinically resource poor, as shown in a Harvard School of Public Health analysis of Medicare claims data for more than 900,000 heart failure discharges. These resource-poor hospitals provide care for underserved populations, and they are experiencing a disproportionate burden of the financial penalties imposed for early readmission.

“As we seek to improve care for patients with heart failure, we should ensure that penalties for poor performance do not worsen disparities in quality of care,” according to the Harvard investigators (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2011;4:53-9).

Dr. Desai reported serving as a consultant to 5AM Ventures, AtCor Medical, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Under intense fiscal pressure to curb early hospital readmissions for heart failure, cardiologists and hospital administrators are taking a hard look at the traditional role of the emergency department as the point of triage for patients with decompensated heart failure.

“Alternatives to the emergency department for ambulatory triage and intervention are essential,” Dr. Akshay Desai said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“Traditionally, when our patients become decompensated, we send them from our office or clinic to the ED. And 80%-90% of those who present to the ED with the diagnosis of heart failure are admitted to the hospital. So this means that the ED is a pretty ineffective triage point for heart failure patients. Most ED staff are concerned about ambulatory follow-up and feel it’s safer to follow patients in the hospital. The message here is we need a more robust ambulatory framework to manage patients with milder decompensation so they don’t all need to come into the hospital,” said Dr. Desai of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Hospital admission is of questionable value for a large fraction of decompensating heart failure patients. After all, not that much happens to them in the hospital that couldn’t take place in a less costly setting.

“For the most part, our patients in the hospital for decompensated heart failure get IV diuretics, with an average weight loss of about 4 kg. Surveillance is typically once- or twice-daily laboratory tests and a bedside clinical visit by a physician at 7:30 in the morning. Few patients get much else. There’s little diagnostic testing, few other therapies that require intensive monitoring, and most patients feel a little better by their first day in the hospital,” he said.

This suggests the need for what he called “an evolved model of heart failure care” in which the ED is replaced as the point of service by some form of ambulatory center that can serve as a buffer limiting the number of patients who need to come into the hospital.

“It could be a home-based strategy of IV diuretic administration, a clinic-based strategy of outpatient diuretic administration, or an observation unit based in the ED. All of these are now being tested in various models across the country as alternatives to help manage the readmission problem, and also to make life better for our patients, who’d prefer not to be in the hospital if they could be managed in other ways,” Dr. Desai continued.

Reducing 30-day readmission rates after a hospitalization for heart failure is seen by health policy makers as an opportunity to simultaneously improve care and reduce costs. But studies show only about half of readmissions in patients with heart failure are cardiovascular related, just half of those cardiovascular readmissions are heart failure related, and only about 30% of heart failure readmissions are truly preventable. However, wide variation exists across the country in risk-adjusted 30-day readmission rates, suggesting there is an opportunity for improvement in outlier hospitals.

Numerous factors have been linked to high heart failure readmission rates, including patient sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and serum markers of heart failure severity. One underappreciated factor, in Dr. Desai’s view, is that readmission rates are significantly higher in hospitals that are financially and clinically resource poor, as shown in a Harvard School of Public Health analysis of Medicare claims data for more than 900,000 heart failure discharges. These resource-poor hospitals provide care for underserved populations, and they are experiencing a disproportionate burden of the financial penalties imposed for early readmission.

“As we seek to improve care for patients with heart failure, we should ensure that penalties for poor performance do not worsen disparities in quality of care,” according to the Harvard investigators (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2011;4:53-9).

Dr. Desai reported serving as a consultant to 5AM Ventures, AtCor Medical, Novartis, and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Environmental factors could increase U.S. anthrax cases

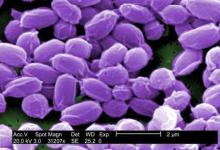

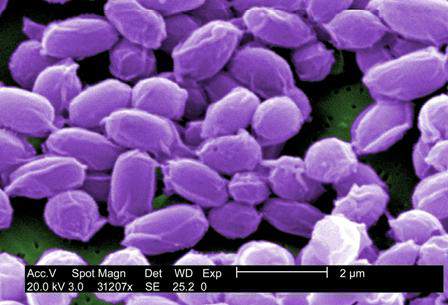

WASHINGTON– Recent isolated cases of anthrax in Minnesota and elsewhere, along with the disease’s relative ease of transmission from animals or plants to humans, should heighten U.S. physicians’ awareness of anthrax’s symptoms and treatments, warned Dr. Jason K. Blackburn.

“[Anthrax] is something that our international partners deal with on an annual basis [as] we can see the disease reemerging, or at least increasing, in annual reports on humans in a number of countries,” explained Dr. Blackburn of the University of Florida in Gainesville, at a meeting on biodefense and emerging diseases sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. “Here in the United States, we’re seeing it shift from a livestock disease [to] a wildlife disease, where we have these populations that we can’t reach with vaccines, and where surveillance is very logistically challenging.”

Environmental factors can drive higher incidences of anthrax cases. Temperature, precipitation, and vegetation indices are key variables that facilitate anthrax transmission and spread of the disease. Geographically, lowland areas also have higher prevalences of the disease.

For example, Dr. Blackburn and his colleagues used predictive models to quantify the theory that anthrax case rates increase during years that have wet springs followed by hot, dry summers in the region of western Texas.

Using these data would allow scientists and health care providers to predict which years would have an increased risk for anthrax cases in humans, Dr. Blackburn said, and could help hospitals and clinics effectively prepare to treat a higher influx of these cases and prevent possible outbreaks.

Although relatively large numbers of human anthrax cases persist in parts of world – particularly in Africa and central Asia – cases in the United States have been primarily relegated to livestock.

However, during the last decade, there has been a noticeable shift in cases from livestock to wildlife, particularly in western Texas and Montana, where local populations of elk, bison, and white-tailed deer have been affected. The newfound prevalence in wildlife species, along with continued presence in domestic animals such as cattle and sheep, mean that transmission to humans could become even easier.

“Human cases are usually driven by direct human interaction with mammalian hosts,” said Dr. Blackburn, citing farms and meat factories as prime examples of where the Bacillus anthracis organism would easily spread. In addition, Dr. Blackburn specifically noted a scenario in which flies can transmit the disease from sheep to humans, and have also been found to carry anthrax from carcasses to wildlife and vegetation.

From 2010 to 2012, anthrax cases in Europe, particularly Georgia and Turkey, increased, compared with numbers over a similar time frame between 2000 and 2009. While case reporting can be partly attributed to this increase, Dr. Blackburn indicated that it was most likely evidence of an associative trend between livestock and human anthrax cases.

Dr. Blackburn did not report any disclosures.

WASHINGTON– Recent isolated cases of anthrax in Minnesota and elsewhere, along with the disease’s relative ease of transmission from animals or plants to humans, should heighten U.S. physicians’ awareness of anthrax’s symptoms and treatments, warned Dr. Jason K. Blackburn.

“[Anthrax] is something that our international partners deal with on an annual basis [as] we can see the disease reemerging, or at least increasing, in annual reports on humans in a number of countries,” explained Dr. Blackburn of the University of Florida in Gainesville, at a meeting on biodefense and emerging diseases sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. “Here in the United States, we’re seeing it shift from a livestock disease [to] a wildlife disease, where we have these populations that we can’t reach with vaccines, and where surveillance is very logistically challenging.”

Environmental factors can drive higher incidences of anthrax cases. Temperature, precipitation, and vegetation indices are key variables that facilitate anthrax transmission and spread of the disease. Geographically, lowland areas also have higher prevalences of the disease.

For example, Dr. Blackburn and his colleagues used predictive models to quantify the theory that anthrax case rates increase during years that have wet springs followed by hot, dry summers in the region of western Texas.

Using these data would allow scientists and health care providers to predict which years would have an increased risk for anthrax cases in humans, Dr. Blackburn said, and could help hospitals and clinics effectively prepare to treat a higher influx of these cases and prevent possible outbreaks.

Although relatively large numbers of human anthrax cases persist in parts of world – particularly in Africa and central Asia – cases in the United States have been primarily relegated to livestock.

However, during the last decade, there has been a noticeable shift in cases from livestock to wildlife, particularly in western Texas and Montana, where local populations of elk, bison, and white-tailed deer have been affected. The newfound prevalence in wildlife species, along with continued presence in domestic animals such as cattle and sheep, mean that transmission to humans could become even easier.

“Human cases are usually driven by direct human interaction with mammalian hosts,” said Dr. Blackburn, citing farms and meat factories as prime examples of where the Bacillus anthracis organism would easily spread. In addition, Dr. Blackburn specifically noted a scenario in which flies can transmit the disease from sheep to humans, and have also been found to carry anthrax from carcasses to wildlife and vegetation.

From 2010 to 2012, anthrax cases in Europe, particularly Georgia and Turkey, increased, compared with numbers over a similar time frame between 2000 and 2009. While case reporting can be partly attributed to this increase, Dr. Blackburn indicated that it was most likely evidence of an associative trend between livestock and human anthrax cases.

Dr. Blackburn did not report any disclosures.

WASHINGTON– Recent isolated cases of anthrax in Minnesota and elsewhere, along with the disease’s relative ease of transmission from animals or plants to humans, should heighten U.S. physicians’ awareness of anthrax’s symptoms and treatments, warned Dr. Jason K. Blackburn.

“[Anthrax] is something that our international partners deal with on an annual basis [as] we can see the disease reemerging, or at least increasing, in annual reports on humans in a number of countries,” explained Dr. Blackburn of the University of Florida in Gainesville, at a meeting on biodefense and emerging diseases sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. “Here in the United States, we’re seeing it shift from a livestock disease [to] a wildlife disease, where we have these populations that we can’t reach with vaccines, and where surveillance is very logistically challenging.”

Environmental factors can drive higher incidences of anthrax cases. Temperature, precipitation, and vegetation indices are key variables that facilitate anthrax transmission and spread of the disease. Geographically, lowland areas also have higher prevalences of the disease.

For example, Dr. Blackburn and his colleagues used predictive models to quantify the theory that anthrax case rates increase during years that have wet springs followed by hot, dry summers in the region of western Texas.

Using these data would allow scientists and health care providers to predict which years would have an increased risk for anthrax cases in humans, Dr. Blackburn said, and could help hospitals and clinics effectively prepare to treat a higher influx of these cases and prevent possible outbreaks.

Although relatively large numbers of human anthrax cases persist in parts of world – particularly in Africa and central Asia – cases in the United States have been primarily relegated to livestock.

However, during the last decade, there has been a noticeable shift in cases from livestock to wildlife, particularly in western Texas and Montana, where local populations of elk, bison, and white-tailed deer have been affected. The newfound prevalence in wildlife species, along with continued presence in domestic animals such as cattle and sheep, mean that transmission to humans could become even easier.

“Human cases are usually driven by direct human interaction with mammalian hosts,” said Dr. Blackburn, citing farms and meat factories as prime examples of where the Bacillus anthracis organism would easily spread. In addition, Dr. Blackburn specifically noted a scenario in which flies can transmit the disease from sheep to humans, and have also been found to carry anthrax from carcasses to wildlife and vegetation.

From 2010 to 2012, anthrax cases in Europe, particularly Georgia and Turkey, increased, compared with numbers over a similar time frame between 2000 and 2009. While case reporting can be partly attributed to this increase, Dr. Blackburn indicated that it was most likely evidence of an associative trend between livestock and human anthrax cases.

Dr. Blackburn did not report any disclosures.

AT THE ASM BIODEFENSE MEETING

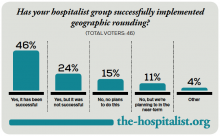

Geographic Rounding of Hospital Nurses Challenges Unit-Based Theory

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Nurses, of course, have always been assigned by unit—that is, geographically. So it should come as no surprise that searching “unit-based” at the-hospitalist.org returns many articles about assigning hospitalists geographically, but not nurses, partly because few would consider it a new idea. But this article is about a new wrinkle in assigning nurses.

Although there likely are a number of hospitals doing something similar, I’ll describe a place I was lucky enough to see up close.

Bassett Medical Center

On a cold day last December, I was part of a team that spent a few days in Cooperstown, N.Y. This is a place that is so pretty that I didn’t immediately recognize we had arrived at the Bassett Medical Center Campus, since the entrance we used looked more like a library topped by a pretty cupola and warmly decorated for the holidays. We met so many nice people, including Kai Mebust, MD, FHM, who I’m convinced works full-time for the local Chamber of Commerce and tourism industry. If he doesn’t, then they should put him on their payroll.

Not long after our arrival, Dr. Mebust led us outside in the winter air without our coats to see the very beautiful view from the patio adjacent to the hospital cafeteria. And before we left for home he climbed in our car to direct us on a tour of the town. I’m sold. What a beautiful place. So much more than the Baseball Hall of Fame for which Cooperstown is known.

When not promoting his town’s tourism or enthusiastically describing his eighth-grade son playing with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band in New Orleans, he seems to find time to serve as the chief of this academic hospital’s hospital medicine practice. He was the principal engineer of the geographic assignment of nurses and describes it with an enthusiasm that matches his service as tour guide.

Geographic Care: Single RN Caring for Five Adjacent Patients

The idea is simple and best described using an illustration. A single nurse cares for five patients in adjacent rooms referred to as a “pod.” A second nurse is responsible for the next pod of five consecutive patients, and a single hospitalist cares for all 10 in both pods. There are currently four pods on a single floor of 36 beds; however, they hope to expand this system to most of the medical-surgical beds in the hospital.

The nurses eligible to care for patients in these pods are all trained to be able to provide “step down” level of care, meaning patients don’t need to transfer to a different location for more frequent monitoring and such therapies as vasopressors, mask ventilation, and the like.

Each hospitalist caring for two pods of 10 adjacent patients will typically have additional patients in other locations. This is the hospital’s way of finding the sweet spot between the competing interests of “load leveling” patient volume across hospitalists and rigidly assigning each doctor to a single location, though if they succeed in expanding the model through most of the hospital, the hospitalists will likely need to figure out how to assign themselves more rigidly to three or four pods.

Additional Components

Each morning, the hospitalist meets with the two pod nurses. They briefly discuss overnight events and plans for the day.

Much later in the morning, they also conduct daily multidisciplinary rounds involving nurse, case manager, pharmacist, dietician, social worker, respiratory therapist, and hospitalist. These follow a standard format, which is posted on the wall, and are done in a workroom that allows most participants to be in front of a computer, so they can enter notes and orders into the electronic health record (EHR) as they discuss patients.

What Is the Big Deal Here?

A lot of smart people have developed and written about systems that assign hospitalists geographically, but in most cases this has not been accompanied by adjustments in the way nurses are assigned. On nursing units at most hospitals, this means that even if a hospitalist has all of her patients on the same floor, she is still interacting with five to seven nurses caring for her patients. That usually means the hospitalist and nurse have less awareness of each other’s thinking and doing than if the ratio is reduced to no more than three or four nurses for a single hospitalist.

Dr. Mebust provided a document enumerating the goals for the program:

- Improve communication;

- Reduce patient bed moves;

- Improve patient and staff satisfaction; and

- Provide more efficient care as measured in time-of-discharge, decreased physician time-per-patient, and possibly length of stay.

Because of a number of problems teasing out the effects of this program and its limited duration to this point, Dr. Mebust and staff can’t provide robust statistics to document success in these goals. But anecdotal information is very encouraging, and clearly the nurses love it.

A major barrier to assigning nurses based rigidly on patients in adjacent rooms is the inability to ensure that each nurse has a workload of roughly equivalent complexity, but they’ve found this is a much less significant problem than feared. The nurse I spoke with said any risk of ending up with unusually complex and time-consuming patients is essentially offset by the efficiency gained by having the same attending hospitalist for all of her patients.

In fact, the nurses love it so much that they much prefer being assigned to a pod rather than a traditional assortment of patients with different attending physicians, even if the latter offers a chance to address uneven acuity.

The Big Picture

I’ve often wished that I could incorporate into hospitalist work some of the efficient ways a doctor and nurse can work together seeing scheduled patients in an outpatient setting. Surely assigning hospitalists geographically does this to some degree and has a number of advantages that others have written about. But it comes at the cost of difficult tradeoffs for hospitalists, and I know of many groups that have abandoned it after concluding that the challenges of the system exceeded its benefits.

But when it is coupled with assigning nurses geographically, I think the benefits are even greater, not only for the hospitalists, but also for patients, nurses, and other hospital staff.

Next time you’re in Cooperstown, be sure you don’t just visit the Baseball Hall of Fame. Look up Dr. Mebust, Komron Ostovar, MD, and their colleagues at Bassett Medical Center. I betcha you’ll be persuaded to see the value of their geographic model.

And maybe you’ll even fall so far under the spell of how they all talk about where they work and live that you’ll be ready to move there and join them.

Does tight control of hypertension in pregnancy produce better perinatal outcomes?

The question of degree of control of hypertension during pregnancy has been debated for many years. The primary concern, which is mainly theoretical, is that tight control of hypertension may lead to underperfusion of the uterus, ultimately resulting in fetal growth restriction. This study adds to the available body of literature on this subject.

Details of the trial

In this pragmatic randomized clinical trial, 987 women with office diastolic BP of 90 to 105 mm Hg (or 85 to 105 mm Hg if they were taking a hypertensive medication) between 14 weeks, zero days of gestation and 33 weeks, 6 days of gestation were randomized to tight (n = 488) versus less-tight control of hypertension (n = 493).

Practitioners were encouraged to use labetalol for treatment. The primary outcome was pregnancy loss (miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy termination, stillbirth, or neonatal death) or the need for high-level neonatal care (defined as greater than normal newborn care for more than 48 hours until 28 days of life or discharge home). Secondary outcomes included serious maternal morbidity as late as 6 weeks postpartum. Statistical analysis was based on the intent-to-treat principle.

Adherence to assigned treatment was good, at approximately 75% in each arm. As stated above, the study found no differences in the combined primary endpoint between the two groups. It also found no differences in other perinatal outcomes, including small size for gestational age or other adverse neonatal outcomes. Maternal complications generally were similar as well, with the exception of severe hypertension, which was more common in the less-tight control group.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This trial has several important strengths, including its pragmatic design, making it more applicable to everyday practice. Other strengths include rigorous methods and a large sample size.

Two main weaknesses hamper the study, however:

- the inclusion of both chronic hypertension and gestational hypertension. In my opinion, the much more clinically relevant question concerns women with chronic hypertension, who have a long duration of treatment.

- the choice of high-level neonatal care as part of the composite endpoint. This aspect of the composite outcome drove the endpoint in terms of numbers, but it is unclear to me what its clinical relevance is. In my opinion, it is a poor surrogate for the neonatal outcomes we really care about.

What this evidence means for practice

This study does not establish a foundation for a change in clinical practice. At best, it supports the maternal safety of less-tight control of hypertension in pregnancy. That aspect of the trial may find its way into counseling of the patient.

–George Macones, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The question of degree of control of hypertension during pregnancy has been debated for many years. The primary concern, which is mainly theoretical, is that tight control of hypertension may lead to underperfusion of the uterus, ultimately resulting in fetal growth restriction. This study adds to the available body of literature on this subject.

Details of the trial

In this pragmatic randomized clinical trial, 987 women with office diastolic BP of 90 to 105 mm Hg (or 85 to 105 mm Hg if they were taking a hypertensive medication) between 14 weeks, zero days of gestation and 33 weeks, 6 days of gestation were randomized to tight (n = 488) versus less-tight control of hypertension (n = 493).

Practitioners were encouraged to use labetalol for treatment. The primary outcome was pregnancy loss (miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy termination, stillbirth, or neonatal death) or the need for high-level neonatal care (defined as greater than normal newborn care for more than 48 hours until 28 days of life or discharge home). Secondary outcomes included serious maternal morbidity as late as 6 weeks postpartum. Statistical analysis was based on the intent-to-treat principle.

Adherence to assigned treatment was good, at approximately 75% in each arm. As stated above, the study found no differences in the combined primary endpoint between the two groups. It also found no differences in other perinatal outcomes, including small size for gestational age or other adverse neonatal outcomes. Maternal complications generally were similar as well, with the exception of severe hypertension, which was more common in the less-tight control group.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This trial has several important strengths, including its pragmatic design, making it more applicable to everyday practice. Other strengths include rigorous methods and a large sample size.

Two main weaknesses hamper the study, however:

- the inclusion of both chronic hypertension and gestational hypertension. In my opinion, the much more clinically relevant question concerns women with chronic hypertension, who have a long duration of treatment.

- the choice of high-level neonatal care as part of the composite endpoint. This aspect of the composite outcome drove the endpoint in terms of numbers, but it is unclear to me what its clinical relevance is. In my opinion, it is a poor surrogate for the neonatal outcomes we really care about.

What this evidence means for practice

This study does not establish a foundation for a change in clinical practice. At best, it supports the maternal safety of less-tight control of hypertension in pregnancy. That aspect of the trial may find its way into counseling of the patient.

–George Macones, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The question of degree of control of hypertension during pregnancy has been debated for many years. The primary concern, which is mainly theoretical, is that tight control of hypertension may lead to underperfusion of the uterus, ultimately resulting in fetal growth restriction. This study adds to the available body of literature on this subject.

Details of the trial

In this pragmatic randomized clinical trial, 987 women with office diastolic BP of 90 to 105 mm Hg (or 85 to 105 mm Hg if they were taking a hypertensive medication) between 14 weeks, zero days of gestation and 33 weeks, 6 days of gestation were randomized to tight (n = 488) versus less-tight control of hypertension (n = 493).

Practitioners were encouraged to use labetalol for treatment. The primary outcome was pregnancy loss (miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy termination, stillbirth, or neonatal death) or the need for high-level neonatal care (defined as greater than normal newborn care for more than 48 hours until 28 days of life or discharge home). Secondary outcomes included serious maternal morbidity as late as 6 weeks postpartum. Statistical analysis was based on the intent-to-treat principle.

Adherence to assigned treatment was good, at approximately 75% in each arm. As stated above, the study found no differences in the combined primary endpoint between the two groups. It also found no differences in other perinatal outcomes, including small size for gestational age or other adverse neonatal outcomes. Maternal complications generally were similar as well, with the exception of severe hypertension, which was more common in the less-tight control group.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This trial has several important strengths, including its pragmatic design, making it more applicable to everyday practice. Other strengths include rigorous methods and a large sample size.

Two main weaknesses hamper the study, however:

- the inclusion of both chronic hypertension and gestational hypertension. In my opinion, the much more clinically relevant question concerns women with chronic hypertension, who have a long duration of treatment.

- the choice of high-level neonatal care as part of the composite endpoint. This aspect of the composite outcome drove the endpoint in terms of numbers, but it is unclear to me what its clinical relevance is. In my opinion, it is a poor surrogate for the neonatal outcomes we really care about.

What this evidence means for practice

This study does not establish a foundation for a change in clinical practice. At best, it supports the maternal safety of less-tight control of hypertension in pregnancy. That aspect of the trial may find its way into counseling of the patient.

–George Macones, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Is supplemental ultrasonography a valuable addition to breast cancer screening for women with dense breasts?

Screening mammography in women with dense breasts (ie, containing more than 50% fibroglandular tissue) is challenging for two reasons:

- Compared with women with less breast density, there is decreased cancer detection (sensitivity) with screening mammography.

- Women with dense breasts have an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer.1

Because nearly half of women in the United States undergoing screening mammography have dense breasts, it is vital that we provide them with accurate and useful counseling.

The challenge of managing women with dense breasts has become complicated by the fact that 21 states have passed laws requiring that women with dense breasts be informed through scripted messages of the decreased sensitivity of screening and increased risk of cancer and advised to

discuss with their provider whether additional testing (eg, with supplemental ultrasound) should be ordered. These laws may be well-intentioned, but they are problematic.

Although there are data documenting increased cancer detection with screening ultrasonography, there are no data currently available demonstrating that this increased detection adds value by improving important outcomes like disease-specific mortality. Further, the value proposition (improved outcomes/cost) of screening ultrasonography is unknown.

In this article, Sprague and colleagues attempt to fill this void by assessing the potential benefits, harms, and cost-effectivenessof supplemental ultrasonography following a negative screening mammogram for women with dense breasts.

Through the use of validated micro-simulation modeling, they calculate that the routine use of supplemental ultrasonography in women with dense breasts might result in 0.36 fewer deaths per 1,000 women screened. Compare this to 6 fewer deaths per 1,000 women undergoing screening mammography.

Moreover, the specificity of supplemental ultrasonography in this setting is poor, with 94% of recommended biopsies yielding benign findings (ie, positive predictive value of 6%).2

What this evidence means for practice

At present, there is little evidence that routine supplemental ultrasonography improves important outcomes such as disease-specific mortality at a rational cost. However, there may be hope on the horizon: Emerging data suggest that digital tomosynthesis as a primary screening modality may improve both specificity and sensitivity, compared with mammography, in women with dense breasts.

Initial experience with tomosynthesis demonstrates both fewer callbacks and improved cancer detection in women, compared with screening mammography.3,4 However, the value proposition of this new technology will ultimately depend on a careful analysis of its effect on mortality and cost.

–Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography. Committee Opinion No. 625. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750–751.

2. Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM, Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE. Screening US in patients with mammographically dense breasts: initial experience with Connecticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology. 2012;265(1):59–69.

3. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

4. Skaane PA, Bandos EB, Eben IN, et al. Two-view digital breast tomosynthesis screening with synthetically reconstructed projection images: comparison with digital breast tomosynthesis with full-field digital mammographic images. Radiology. 2014;271(3):655–663.

Screening mammography in women with dense breasts (ie, containing more than 50% fibroglandular tissue) is challenging for two reasons:

- Compared with women with less breast density, there is decreased cancer detection (sensitivity) with screening mammography.

- Women with dense breasts have an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer.1

Because nearly half of women in the United States undergoing screening mammography have dense breasts, it is vital that we provide them with accurate and useful counseling.

The challenge of managing women with dense breasts has become complicated by the fact that 21 states have passed laws requiring that women with dense breasts be informed through scripted messages of the decreased sensitivity of screening and increased risk of cancer and advised to

discuss with their provider whether additional testing (eg, with supplemental ultrasound) should be ordered. These laws may be well-intentioned, but they are problematic.

Although there are data documenting increased cancer detection with screening ultrasonography, there are no data currently available demonstrating that this increased detection adds value by improving important outcomes like disease-specific mortality. Further, the value proposition (improved outcomes/cost) of screening ultrasonography is unknown.

In this article, Sprague and colleagues attempt to fill this void by assessing the potential benefits, harms, and cost-effectivenessof supplemental ultrasonography following a negative screening mammogram for women with dense breasts.

Through the use of validated micro-simulation modeling, they calculate that the routine use of supplemental ultrasonography in women with dense breasts might result in 0.36 fewer deaths per 1,000 women screened. Compare this to 6 fewer deaths per 1,000 women undergoing screening mammography.

Moreover, the specificity of supplemental ultrasonography in this setting is poor, with 94% of recommended biopsies yielding benign findings (ie, positive predictive value of 6%).2

What this evidence means for practice

At present, there is little evidence that routine supplemental ultrasonography improves important outcomes such as disease-specific mortality at a rational cost. However, there may be hope on the horizon: Emerging data suggest that digital tomosynthesis as a primary screening modality may improve both specificity and sensitivity, compared with mammography, in women with dense breasts.

Initial experience with tomosynthesis demonstrates both fewer callbacks and improved cancer detection in women, compared with screening mammography.3,4 However, the value proposition of this new technology will ultimately depend on a careful analysis of its effect on mortality and cost.

–Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Screening mammography in women with dense breasts (ie, containing more than 50% fibroglandular tissue) is challenging for two reasons:

- Compared with women with less breast density, there is decreased cancer detection (sensitivity) with screening mammography.

- Women with dense breasts have an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer.1

Because nearly half of women in the United States undergoing screening mammography have dense breasts, it is vital that we provide them with accurate and useful counseling.

The challenge of managing women with dense breasts has become complicated by the fact that 21 states have passed laws requiring that women with dense breasts be informed through scripted messages of the decreased sensitivity of screening and increased risk of cancer and advised to

discuss with their provider whether additional testing (eg, with supplemental ultrasound) should be ordered. These laws may be well-intentioned, but they are problematic.

Although there are data documenting increased cancer detection with screening ultrasonography, there are no data currently available demonstrating that this increased detection adds value by improving important outcomes like disease-specific mortality. Further, the value proposition (improved outcomes/cost) of screening ultrasonography is unknown.

In this article, Sprague and colleagues attempt to fill this void by assessing the potential benefits, harms, and cost-effectivenessof supplemental ultrasonography following a negative screening mammogram for women with dense breasts.

Through the use of validated micro-simulation modeling, they calculate that the routine use of supplemental ultrasonography in women with dense breasts might result in 0.36 fewer deaths per 1,000 women screened. Compare this to 6 fewer deaths per 1,000 women undergoing screening mammography.

Moreover, the specificity of supplemental ultrasonography in this setting is poor, with 94% of recommended biopsies yielding benign findings (ie, positive predictive value of 6%).2

What this evidence means for practice

At present, there is little evidence that routine supplemental ultrasonography improves important outcomes such as disease-specific mortality at a rational cost. However, there may be hope on the horizon: Emerging data suggest that digital tomosynthesis as a primary screening modality may improve both specificity and sensitivity, compared with mammography, in women with dense breasts.

Initial experience with tomosynthesis demonstrates both fewer callbacks and improved cancer detection in women, compared with screening mammography.3,4 However, the value proposition of this new technology will ultimately depend on a careful analysis of its effect on mortality and cost.

–Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography. Committee Opinion No. 625. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750–751.

2. Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM, Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE. Screening US in patients with mammographically dense breasts: initial experience with Connecticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology. 2012;265(1):59–69.

3. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

4. Skaane PA, Bandos EB, Eben IN, et al. Two-view digital breast tomosynthesis screening with synthetically reconstructed projection images: comparison with digital breast tomosynthesis with full-field digital mammographic images. Radiology. 2014;271(3):655–663.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of women with dense breasts diagnosed by mammography. Committee Opinion No. 625. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):750–751.

2. Hooley RJ, Greenberg KL, Stackhouse RM, Geisel JL, Butler RS, Philpotts LE. Screening US in patients with mammographically dense breasts: initial experience with Connecticut Public Act 09-41. Radiology. 2012;265(1):59–69.

3. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

4. Skaane PA, Bandos EB, Eben IN, et al. Two-view digital breast tomosynthesis screening with synthetically reconstructed projection images: comparison with digital breast tomosynthesis with full-field digital mammographic images. Radiology. 2014;271(3):655–663.

Dr. Andrew M. Kaunitz on prescribing systemic HT to older women

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Broadly implementing stroke embolectomy faces hurdles

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Results from three randomized controlled trials presented at the International Stroke Conference, plus the outcomes from a fourth trial first reported last fall, immediately established embolectomy as standard-of-care treatment for selected patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Stroke experts interviewed during the conference, however, said that making embolectomy routinely available to most U.S. stroke patients who would be candidates for the intervention will take months, if not years.

They envision challenges involving the availability of trained interventionalists, triage of patients to the right centers, and reimbursement issues as some of the obstacles to be dealt with before endovascular embolectomy aimed at removing intracerebral-artery occlusions in acute ischemic stroke patients becomes uniformly available.

Yet another challenge will arise when stroke-treatment groups that did not participate in the trials strive to replicate the success their colleagues reported by implementing the highly streamlined systems that were used in the trials for identifying appropriate stroke patients and for delivering treatment. Those systems were cited as an important reason why those studies succeeded in producing positive outcomes when similar embolectomy trials without the same efficiencies reported just a year or two ago failed to show benefit.

“The evidence makes it standard of care, but the challenge is that our systems are not set up. This is the big thing we will all go home to work on,” said Dr. Pooja Khatri, professor of neurology and director of acute stroke at the University of Cincinnati.

“You talk to everyone at this meeting, and what they want to go home and figure out is how can we deliver this care. It’s really challenging, at a myriad of levels,” said Dr. Colin P. Derdeyn, professor of neurology and director of the Center for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease at Washington University in St. Louis.

Growing endovascular availability

Arguably the most critical issue in rolling out endovascular stroke interventions more broadly is scaling up the number of centers that have the staff and systems in place to perform them. Clearly, the scope of providers able to deliver this treatment currently falls substantially short of what will be needed. “It’s kind of daunting to think about the [workforce] needs,” Dr. Khatri said in a talk at the conference, which was sponsored by the American Heart Association.

“In the United States, we’ve been building out a two-tier system, with comprehensive stroke centers capable of delivering this [endovascular embolectomy] treatment” and primary stroke centers capable of administering intravenous treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), the first treatment that patients eligible for embolectomy should receive, said Dr. Jeffrey L. Saver, professor of neurology and director of the stroke center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and lead investigator for one of the new embolectomy studies.

“Work groups have suggested about 60,000 U.S. stroke patients could potentially be treated with endovascular therapy, and we’d need about 300 comprehensive stroke centers to do this.” Dr. Saver estimated the current total of U.S. comprehensive stroke centers to be 75, a number that several others at the meeting pegged as more like 80, and they also noted that some centers are endovascular ready but have not received official comprehensive stroke center certification from the Joint Commission.