User login

How a cheap liver drug may be the key to preventing COVID

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

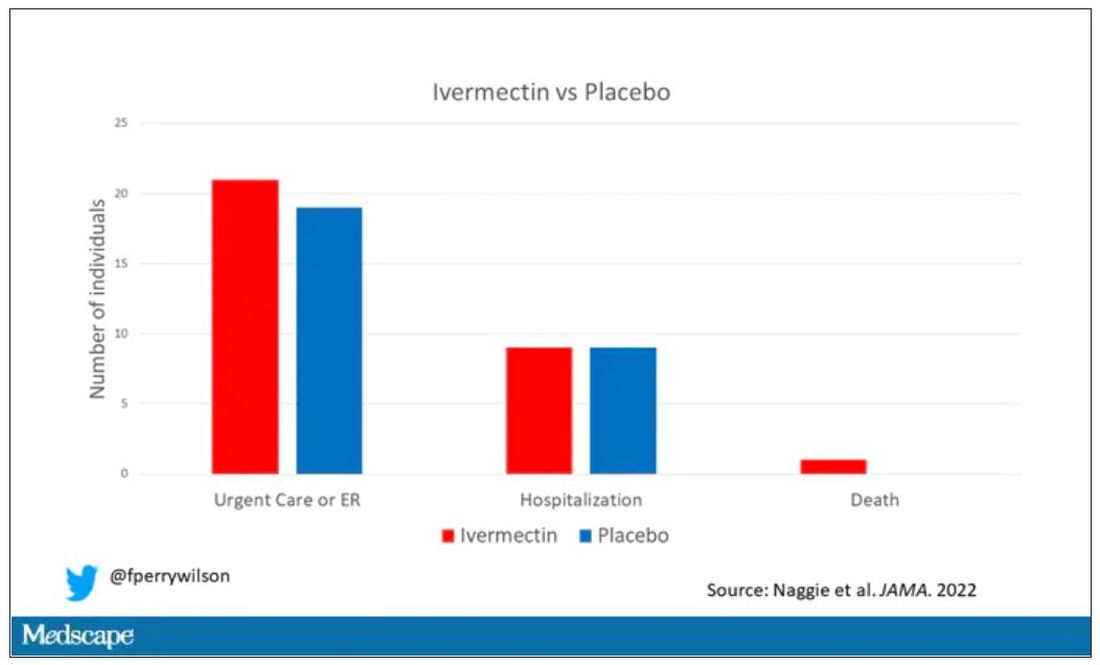

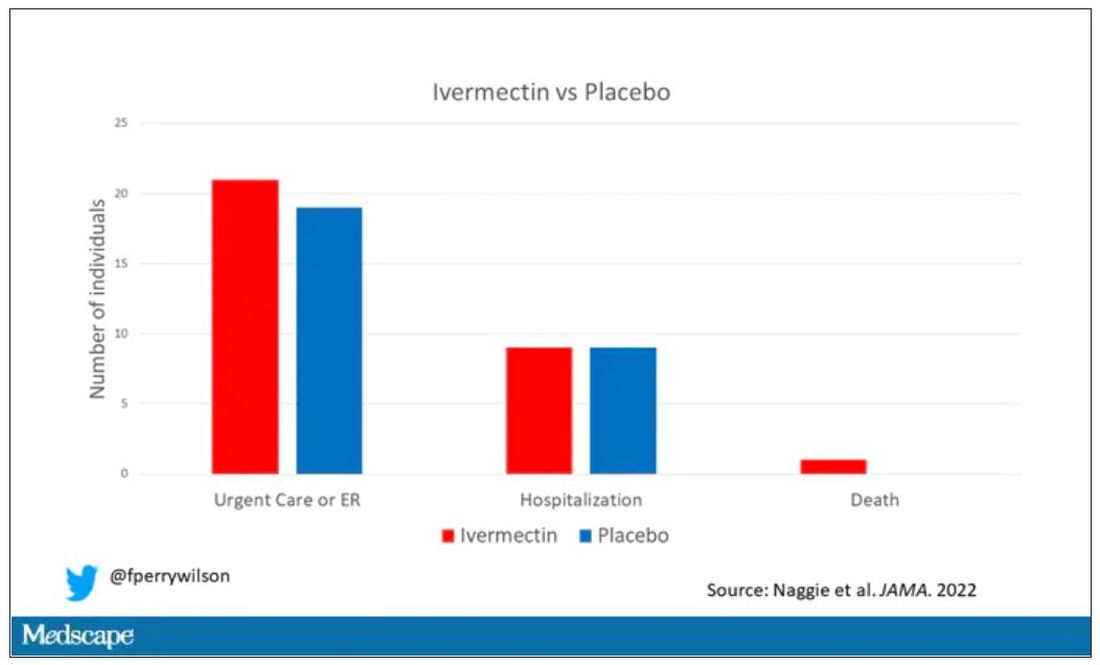

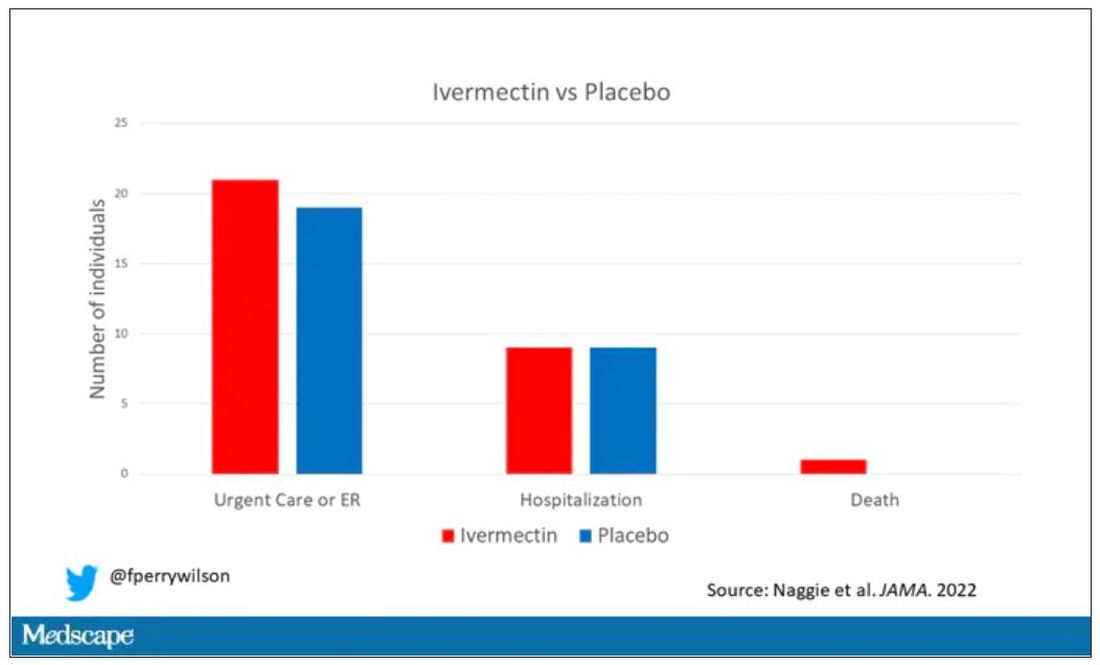

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Migraine in children and teens: managing the pain

By the time Mira Halker started high school, hardly a day passed that she wasn’t either getting a migraine attack or recovering from one. She missed volleyball team practice. She missed classes. She missed social events. And few people understood. After all, she looked healthy.

“A lot of times, people think I’m faking it,” said Mira, now 16, who lives in Phoenix. Friends called her flaky; her volleyball coaches questioned her dedication to the team. “I’m like, ‘I’m not trying to get out of this. This is not what this is about,’ ” she said.

Her mother, Rashmi B. Halker Singh, MD, is a neurologist at Mayo Clinic who happens to specialize in migraine. Even so, finding a solution was not easy. Neither ibuprofen nor triptans, nor various preventive measures such as a daily prescription for topiramate controlled the pain and associated symptoms. Mira was barely making it through her school day and had to quit volleyball. Then, in the spring of 10th grade, Mira told her mother that she couldn’t go to prom because the loud noises and lights could give her a migraine attack.

Mother and daughter decided it was time to get even more aggressive. “There are these key moments in life that you can’t get back,” Dr. Singh said. “Migraine steals so much from you.”

Diagnosis

One of the challenges Mira’s physicians faced was deciding which medications and other therapies to prescribe to a teenager. Drug companies have been releasing a steady stream of new treatments for migraine headaches, and researchers promise more are on the way soon. Here’s what works for children, what hasn’t yet been approved for use with minors, and how to diagnose migraines in the first place, from experts at some of the nation’s leading pediatric headache centers.

Migraine affects about 10% of children, according to the American Migraine Foundation. The headaches can strike children as early as age 3 or 4 years, said Robert Little, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Before puberty, boys report more migraine attacks than girls, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. But that reverses in adolescence: By age 17, as many as 8% of boys and 23% of girls have had migraine. To diagnose migraine, Juliana H. VanderPluym, MD, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, said she uses the criteria published in the latest edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD): A patient must have had at least five attacks in their life; and in children and adolescents, the attacks must last no less than 2 hours.

In addition, the headaches should exhibit at least two out of four features:

1. Occur more on one side of the head than the other (although Dr. VanderPluym said in children and adolescents headaches often are bilateral).

2. Be of moderate to severe intensity.

3. Have a pounding or throbbing quality.

4. Grow worse with activity or cause an avoidance of activity.

If the attacks meet those criteria, clinicians should check to see if they meet at least one out of the two following:

1. Are sensitive to light and sounds.

2. Are associated with nausea and/or vomiting.

A clinician should consider whether the headaches are not better accounted for by another diagnosis, according to the ICHD criteria. But, Dr. VanderPluym warned that does not necessarily mean running a slew of tests.

“In the absence of red flag features, it is more than likely going to be migraine headache,” she said. That’s especially true if a child has a family history of migraine, as the condition is often passed down from parent to child.

Ultimately, the diagnosis is fairly simple and can be made in a minute or less, said Jack Gladstein, MD, a pediatrician at the University of Maryland whose research focuses on the clinical care of children and adolescents with headache.

“Migraine is acute,” Dr. Gladstein said. “It’s really bad. And it’s recurrent.”

First line of treatment

Whatever a patient takes to treat a migraine, they should hit it early and hard, Dr. Gladstein said.

“The first thing you say, as a primary care physician, is treat your migraine at first twinge, whatever you use. Don’t wait, don’t wish it away,” he said. “The longer you wait, the less chance anything will work.”

The second piece of advice, Dr. Gladstein said, is that whatever drug a patient is taking, they should be on the highest feasible dose. “Work as fast as you can to treat them. You want the brain to reset as quickly as you can,” he said.

Patients should begin with over-the-counter pain relievers, Dr. Little said. If those prove insufficient, they can try a triptan. Rizatriptan is the only such agent that the Food and Drug Administration has approved for children aged 6-17 years. Other drugs in the class – sumatriptan/naproxen, almotriptan, and zolmitriptan – are approved for children 12 and older.

Another migraine therapy recently approved for children aged 12 and older is the use of neurostimulators. “It’s helpful to be aware of them,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

However, if neurostimulators and acute medications prove insufficient, clinicians should warn patients not to up their doses of triptans. Rebound headaches can occur if patients take triptans more than twice a week, or a maximum 10 days per month.

Another possibility is to add a preventive therapy. One mild, first option is nutraceuticals, like riboflavin (vitamin B2) or magnesium, said Anisa F. Kelley, MD, a neurologist and associate director of the headache program at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“We don’t have definitive evidence, but they’re probably doing more benefit than they are harm,” Dr. Kelley said of these therapies. “In patients who have anywhere from 4 to 8 migraine days a month, where you’re in that in-between period where you don’t necessarily need a [prescription] prophylactic, I will often start with a nutraceutical,” Dr. Kelley said.

For those patients who don’t respond to nutraceuticals, or who need more support, clinicians can prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate. Dr. VanderPluym said.

A 2017 study found such prophylactics to be no more effective than placebo in pediatric migraine patients, but experts caution the results should not be considered definitive.

For one thing, the study enrolled a highly selective group of participants, with milder forms of migraine who may have improved anyway, Dr. VanderPluym said. All participants also received lifestyle counseling.

Every time participants came in for a follow-up, they were asked questions such as how much water were they drinking and how much sleep were they getting, Dr. Kelley noted. The takeaway, she said: “Pediatric and adolescent migraine [management] is very, very much reliant on lifestyle factors.”

Lifestyle triggers

Clinicians should counsel their migraine patients about lifestyle changes, experts said. Getting adequate sleep, staying hydrated, and managing stress can help reduce the intensity and frequency of attacks.

Migraine patients should also be mindful of their screen time, Dr. Kelley added.

“I’ve had lots and lots of patients who find excessive screen time will trigger or worsen migraine,” she said.

As for other potential triggers of attacks, the evidence is mixed.

“There’s clearly an association with disrupted sleep and migraine, and that has been very well established,” Dr. Little said. “And there is some modest amount of evidence that regular exercise can be helpful.” But for reported food triggers, he said, there have been very inconclusive results.

Commonly reported triggers include MSG, red wine, chocolate, and aged cheese. When Dr. Little’s patients keep headache diaries, tracking their meals alongside when they got migraine attacks, they often discover individualized triggers – strawberries, for instance, in one case, he said.

Scientists believe migraines result from the inappropriate activation of the trigeminal ganglion. “The question is, what causes it to get triggered? And how does it get triggered?” Dr. Gladstein said. “And that’s where there’s a lot of difference of opinion and no conclusive evidence.” Clinicians also should make sure that something else – usually depression, anxiety, insomnia, and dizziness – is not hindering effective migraine management. “If someone has terrible insomnia, until you treat the insomnia, the headaches aren’t going to get better,” he said.

As for Mira, her migraine attacks did not significantly improve, despite trying triptans, prophylactics, lifestyle changes, and shots to block nerve pain. When the headaches threatened Mira’s chance to go to her prom, her neurologist suggested trying something different. The physician persuaded the family’s insurance to cover a calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonist, an injectable monoclonal antibody treatment for migraine that the FDA has currently approved only for use in adults.

The difference for Mira has been extraordinary.

“I can do so much more than I was able to do,” said Mira, who attended the dance migraine free. “I feel liberated.”

It’s only migraine

One of the greatest challenges in diagnosing migraine can be reassuring the patient, the parents, even clinicians themselves that migraine really is the cause of all this pain and discomfort, experts said.

“A lot of migraine treatment actually comes down to migraine education,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

Patients and their parents often wonder how they can be sure that this pain is not resulting from something more dangerous than migraine, Dr. Little said. In these cases, he cites practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Neurology.

“The gist of those guidelines is that most pediatric patients do not need further workup,” he said. “But I think that there’s always a fear that you’re missing something because we don’t have a test that we can do” for migraine.

Some warning signs that further tests might be warranted, Dr. Kelley said, include:

- Headaches that wake a patient up in the middle of the night.

- Headaches that start first thing in the morning, especially those that include vomiting.

- A headache pattern that suddenly gets much worse.

- Certain symptoms that accompany the headache, such as tingling, numbness or double vision.

Although all of these signs can still stem from migraines – tingling or numbness, for instance, can be signs of migraine aura – running additional tests can rule out more serious concerns, she said.

By the time Mira Halker started high school, hardly a day passed that she wasn’t either getting a migraine attack or recovering from one. She missed volleyball team practice. She missed classes. She missed social events. And few people understood. After all, she looked healthy.

“A lot of times, people think I’m faking it,” said Mira, now 16, who lives in Phoenix. Friends called her flaky; her volleyball coaches questioned her dedication to the team. “I’m like, ‘I’m not trying to get out of this. This is not what this is about,’ ” she said.

Her mother, Rashmi B. Halker Singh, MD, is a neurologist at Mayo Clinic who happens to specialize in migraine. Even so, finding a solution was not easy. Neither ibuprofen nor triptans, nor various preventive measures such as a daily prescription for topiramate controlled the pain and associated symptoms. Mira was barely making it through her school day and had to quit volleyball. Then, in the spring of 10th grade, Mira told her mother that she couldn’t go to prom because the loud noises and lights could give her a migraine attack.

Mother and daughter decided it was time to get even more aggressive. “There are these key moments in life that you can’t get back,” Dr. Singh said. “Migraine steals so much from you.”

Diagnosis

One of the challenges Mira’s physicians faced was deciding which medications and other therapies to prescribe to a teenager. Drug companies have been releasing a steady stream of new treatments for migraine headaches, and researchers promise more are on the way soon. Here’s what works for children, what hasn’t yet been approved for use with minors, and how to diagnose migraines in the first place, from experts at some of the nation’s leading pediatric headache centers.

Migraine affects about 10% of children, according to the American Migraine Foundation. The headaches can strike children as early as age 3 or 4 years, said Robert Little, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Before puberty, boys report more migraine attacks than girls, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. But that reverses in adolescence: By age 17, as many as 8% of boys and 23% of girls have had migraine. To diagnose migraine, Juliana H. VanderPluym, MD, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, said she uses the criteria published in the latest edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD): A patient must have had at least five attacks in their life; and in children and adolescents, the attacks must last no less than 2 hours.

In addition, the headaches should exhibit at least two out of four features:

1. Occur more on one side of the head than the other (although Dr. VanderPluym said in children and adolescents headaches often are bilateral).

2. Be of moderate to severe intensity.

3. Have a pounding or throbbing quality.

4. Grow worse with activity or cause an avoidance of activity.

If the attacks meet those criteria, clinicians should check to see if they meet at least one out of the two following:

1. Are sensitive to light and sounds.

2. Are associated with nausea and/or vomiting.

A clinician should consider whether the headaches are not better accounted for by another diagnosis, according to the ICHD criteria. But, Dr. VanderPluym warned that does not necessarily mean running a slew of tests.

“In the absence of red flag features, it is more than likely going to be migraine headache,” she said. That’s especially true if a child has a family history of migraine, as the condition is often passed down from parent to child.

Ultimately, the diagnosis is fairly simple and can be made in a minute or less, said Jack Gladstein, MD, a pediatrician at the University of Maryland whose research focuses on the clinical care of children and adolescents with headache.

“Migraine is acute,” Dr. Gladstein said. “It’s really bad. And it’s recurrent.”

First line of treatment

Whatever a patient takes to treat a migraine, they should hit it early and hard, Dr. Gladstein said.

“The first thing you say, as a primary care physician, is treat your migraine at first twinge, whatever you use. Don’t wait, don’t wish it away,” he said. “The longer you wait, the less chance anything will work.”

The second piece of advice, Dr. Gladstein said, is that whatever drug a patient is taking, they should be on the highest feasible dose. “Work as fast as you can to treat them. You want the brain to reset as quickly as you can,” he said.

Patients should begin with over-the-counter pain relievers, Dr. Little said. If those prove insufficient, they can try a triptan. Rizatriptan is the only such agent that the Food and Drug Administration has approved for children aged 6-17 years. Other drugs in the class – sumatriptan/naproxen, almotriptan, and zolmitriptan – are approved for children 12 and older.

Another migraine therapy recently approved for children aged 12 and older is the use of neurostimulators. “It’s helpful to be aware of them,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

However, if neurostimulators and acute medications prove insufficient, clinicians should warn patients not to up their doses of triptans. Rebound headaches can occur if patients take triptans more than twice a week, or a maximum 10 days per month.

Another possibility is to add a preventive therapy. One mild, first option is nutraceuticals, like riboflavin (vitamin B2) or magnesium, said Anisa F. Kelley, MD, a neurologist and associate director of the headache program at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“We don’t have definitive evidence, but they’re probably doing more benefit than they are harm,” Dr. Kelley said of these therapies. “In patients who have anywhere from 4 to 8 migraine days a month, where you’re in that in-between period where you don’t necessarily need a [prescription] prophylactic, I will often start with a nutraceutical,” Dr. Kelley said.

For those patients who don’t respond to nutraceuticals, or who need more support, clinicians can prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate. Dr. VanderPluym said.

A 2017 study found such prophylactics to be no more effective than placebo in pediatric migraine patients, but experts caution the results should not be considered definitive.

For one thing, the study enrolled a highly selective group of participants, with milder forms of migraine who may have improved anyway, Dr. VanderPluym said. All participants also received lifestyle counseling.

Every time participants came in for a follow-up, they were asked questions such as how much water were they drinking and how much sleep were they getting, Dr. Kelley noted. The takeaway, she said: “Pediatric and adolescent migraine [management] is very, very much reliant on lifestyle factors.”

Lifestyle triggers

Clinicians should counsel their migraine patients about lifestyle changes, experts said. Getting adequate sleep, staying hydrated, and managing stress can help reduce the intensity and frequency of attacks.

Migraine patients should also be mindful of their screen time, Dr. Kelley added.

“I’ve had lots and lots of patients who find excessive screen time will trigger or worsen migraine,” she said.

As for other potential triggers of attacks, the evidence is mixed.

“There’s clearly an association with disrupted sleep and migraine, and that has been very well established,” Dr. Little said. “And there is some modest amount of evidence that regular exercise can be helpful.” But for reported food triggers, he said, there have been very inconclusive results.

Commonly reported triggers include MSG, red wine, chocolate, and aged cheese. When Dr. Little’s patients keep headache diaries, tracking their meals alongside when they got migraine attacks, they often discover individualized triggers – strawberries, for instance, in one case, he said.

Scientists believe migraines result from the inappropriate activation of the trigeminal ganglion. “The question is, what causes it to get triggered? And how does it get triggered?” Dr. Gladstein said. “And that’s where there’s a lot of difference of opinion and no conclusive evidence.” Clinicians also should make sure that something else – usually depression, anxiety, insomnia, and dizziness – is not hindering effective migraine management. “If someone has terrible insomnia, until you treat the insomnia, the headaches aren’t going to get better,” he said.

As for Mira, her migraine attacks did not significantly improve, despite trying triptans, prophylactics, lifestyle changes, and shots to block nerve pain. When the headaches threatened Mira’s chance to go to her prom, her neurologist suggested trying something different. The physician persuaded the family’s insurance to cover a calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonist, an injectable monoclonal antibody treatment for migraine that the FDA has currently approved only for use in adults.

The difference for Mira has been extraordinary.

“I can do so much more than I was able to do,” said Mira, who attended the dance migraine free. “I feel liberated.”

It’s only migraine

One of the greatest challenges in diagnosing migraine can be reassuring the patient, the parents, even clinicians themselves that migraine really is the cause of all this pain and discomfort, experts said.

“A lot of migraine treatment actually comes down to migraine education,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

Patients and their parents often wonder how they can be sure that this pain is not resulting from something more dangerous than migraine, Dr. Little said. In these cases, he cites practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Neurology.

“The gist of those guidelines is that most pediatric patients do not need further workup,” he said. “But I think that there’s always a fear that you’re missing something because we don’t have a test that we can do” for migraine.

Some warning signs that further tests might be warranted, Dr. Kelley said, include:

- Headaches that wake a patient up in the middle of the night.

- Headaches that start first thing in the morning, especially those that include vomiting.

- A headache pattern that suddenly gets much worse.

- Certain symptoms that accompany the headache, such as tingling, numbness or double vision.

Although all of these signs can still stem from migraines – tingling or numbness, for instance, can be signs of migraine aura – running additional tests can rule out more serious concerns, she said.

By the time Mira Halker started high school, hardly a day passed that she wasn’t either getting a migraine attack or recovering from one. She missed volleyball team practice. She missed classes. She missed social events. And few people understood. After all, she looked healthy.

“A lot of times, people think I’m faking it,” said Mira, now 16, who lives in Phoenix. Friends called her flaky; her volleyball coaches questioned her dedication to the team. “I’m like, ‘I’m not trying to get out of this. This is not what this is about,’ ” she said.

Her mother, Rashmi B. Halker Singh, MD, is a neurologist at Mayo Clinic who happens to specialize in migraine. Even so, finding a solution was not easy. Neither ibuprofen nor triptans, nor various preventive measures such as a daily prescription for topiramate controlled the pain and associated symptoms. Mira was barely making it through her school day and had to quit volleyball. Then, in the spring of 10th grade, Mira told her mother that she couldn’t go to prom because the loud noises and lights could give her a migraine attack.

Mother and daughter decided it was time to get even more aggressive. “There are these key moments in life that you can’t get back,” Dr. Singh said. “Migraine steals so much from you.”

Diagnosis

One of the challenges Mira’s physicians faced was deciding which medications and other therapies to prescribe to a teenager. Drug companies have been releasing a steady stream of new treatments for migraine headaches, and researchers promise more are on the way soon. Here’s what works for children, what hasn’t yet been approved for use with minors, and how to diagnose migraines in the first place, from experts at some of the nation’s leading pediatric headache centers.

Migraine affects about 10% of children, according to the American Migraine Foundation. The headaches can strike children as early as age 3 or 4 years, said Robert Little, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Before puberty, boys report more migraine attacks than girls, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. But that reverses in adolescence: By age 17, as many as 8% of boys and 23% of girls have had migraine. To diagnose migraine, Juliana H. VanderPluym, MD, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, said she uses the criteria published in the latest edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD): A patient must have had at least five attacks in their life; and in children and adolescents, the attacks must last no less than 2 hours.

In addition, the headaches should exhibit at least two out of four features:

1. Occur more on one side of the head than the other (although Dr. VanderPluym said in children and adolescents headaches often are bilateral).

2. Be of moderate to severe intensity.

3. Have a pounding or throbbing quality.

4. Grow worse with activity or cause an avoidance of activity.

If the attacks meet those criteria, clinicians should check to see if they meet at least one out of the two following:

1. Are sensitive to light and sounds.

2. Are associated with nausea and/or vomiting.

A clinician should consider whether the headaches are not better accounted for by another diagnosis, according to the ICHD criteria. But, Dr. VanderPluym warned that does not necessarily mean running a slew of tests.

“In the absence of red flag features, it is more than likely going to be migraine headache,” she said. That’s especially true if a child has a family history of migraine, as the condition is often passed down from parent to child.

Ultimately, the diagnosis is fairly simple and can be made in a minute or less, said Jack Gladstein, MD, a pediatrician at the University of Maryland whose research focuses on the clinical care of children and adolescents with headache.

“Migraine is acute,” Dr. Gladstein said. “It’s really bad. And it’s recurrent.”

First line of treatment

Whatever a patient takes to treat a migraine, they should hit it early and hard, Dr. Gladstein said.

“The first thing you say, as a primary care physician, is treat your migraine at first twinge, whatever you use. Don’t wait, don’t wish it away,” he said. “The longer you wait, the less chance anything will work.”

The second piece of advice, Dr. Gladstein said, is that whatever drug a patient is taking, they should be on the highest feasible dose. “Work as fast as you can to treat them. You want the brain to reset as quickly as you can,” he said.

Patients should begin with over-the-counter pain relievers, Dr. Little said. If those prove insufficient, they can try a triptan. Rizatriptan is the only such agent that the Food and Drug Administration has approved for children aged 6-17 years. Other drugs in the class – sumatriptan/naproxen, almotriptan, and zolmitriptan – are approved for children 12 and older.

Another migraine therapy recently approved for children aged 12 and older is the use of neurostimulators. “It’s helpful to be aware of them,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

However, if neurostimulators and acute medications prove insufficient, clinicians should warn patients not to up their doses of triptans. Rebound headaches can occur if patients take triptans more than twice a week, or a maximum 10 days per month.

Another possibility is to add a preventive therapy. One mild, first option is nutraceuticals, like riboflavin (vitamin B2) or magnesium, said Anisa F. Kelley, MD, a neurologist and associate director of the headache program at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“We don’t have definitive evidence, but they’re probably doing more benefit than they are harm,” Dr. Kelley said of these therapies. “In patients who have anywhere from 4 to 8 migraine days a month, where you’re in that in-between period where you don’t necessarily need a [prescription] prophylactic, I will often start with a nutraceutical,” Dr. Kelley said.

For those patients who don’t respond to nutraceuticals, or who need more support, clinicians can prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate. Dr. VanderPluym said.

A 2017 study found such prophylactics to be no more effective than placebo in pediatric migraine patients, but experts caution the results should not be considered definitive.

For one thing, the study enrolled a highly selective group of participants, with milder forms of migraine who may have improved anyway, Dr. VanderPluym said. All participants also received lifestyle counseling.

Every time participants came in for a follow-up, they were asked questions such as how much water were they drinking and how much sleep were they getting, Dr. Kelley noted. The takeaway, she said: “Pediatric and adolescent migraine [management] is very, very much reliant on lifestyle factors.”

Lifestyle triggers

Clinicians should counsel their migraine patients about lifestyle changes, experts said. Getting adequate sleep, staying hydrated, and managing stress can help reduce the intensity and frequency of attacks.

Migraine patients should also be mindful of their screen time, Dr. Kelley added.

“I’ve had lots and lots of patients who find excessive screen time will trigger or worsen migraine,” she said.

As for other potential triggers of attacks, the evidence is mixed.

“There’s clearly an association with disrupted sleep and migraine, and that has been very well established,” Dr. Little said. “And there is some modest amount of evidence that regular exercise can be helpful.” But for reported food triggers, he said, there have been very inconclusive results.

Commonly reported triggers include MSG, red wine, chocolate, and aged cheese. When Dr. Little’s patients keep headache diaries, tracking their meals alongside when they got migraine attacks, they often discover individualized triggers – strawberries, for instance, in one case, he said.

Scientists believe migraines result from the inappropriate activation of the trigeminal ganglion. “The question is, what causes it to get triggered? And how does it get triggered?” Dr. Gladstein said. “And that’s where there’s a lot of difference of opinion and no conclusive evidence.” Clinicians also should make sure that something else – usually depression, anxiety, insomnia, and dizziness – is not hindering effective migraine management. “If someone has terrible insomnia, until you treat the insomnia, the headaches aren’t going to get better,” he said.

As for Mira, her migraine attacks did not significantly improve, despite trying triptans, prophylactics, lifestyle changes, and shots to block nerve pain. When the headaches threatened Mira’s chance to go to her prom, her neurologist suggested trying something different. The physician persuaded the family’s insurance to cover a calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonist, an injectable monoclonal antibody treatment for migraine that the FDA has currently approved only for use in adults.

The difference for Mira has been extraordinary.

“I can do so much more than I was able to do,” said Mira, who attended the dance migraine free. “I feel liberated.”

It’s only migraine

One of the greatest challenges in diagnosing migraine can be reassuring the patient, the parents, even clinicians themselves that migraine really is the cause of all this pain and discomfort, experts said.

“A lot of migraine treatment actually comes down to migraine education,” Dr. VanderPluym said.

Patients and their parents often wonder how they can be sure that this pain is not resulting from something more dangerous than migraine, Dr. Little said. In these cases, he cites practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Neurology.

“The gist of those guidelines is that most pediatric patients do not need further workup,” he said. “But I think that there’s always a fear that you’re missing something because we don’t have a test that we can do” for migraine.

Some warning signs that further tests might be warranted, Dr. Kelley said, include:

- Headaches that wake a patient up in the middle of the night.

- Headaches that start first thing in the morning, especially those that include vomiting.

- A headache pattern that suddenly gets much worse.

- Certain symptoms that accompany the headache, such as tingling, numbness or double vision.

Although all of these signs can still stem from migraines – tingling or numbness, for instance, can be signs of migraine aura – running additional tests can rule out more serious concerns, she said.

New and Improved Devices Add More Therapeutic Options for Treatment of Migraine

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.

One chronic cluster patient has relied on subcutaneous sumatriptan and breathing 100% oxygen at 12 liters per minute through a mask over his nose and mouth for acute relief from his headaches. His headache pain can climb from a 3 to a 10 in a matter of minutes. It starts behind and a bit above the right eye where he feels a tremendous pressure building up. He says that at times it feels like a screwdriver has been thrust into his eye and is being turned. Along with the pain, the eye becomes red, the pupil constricts, and the eyelid droops. He also has dripping from the right nostril, which stuffs up when the pain abates. The pain lasts for 1 to 2 hours, then returns 3 to 5 times a day for 5 days a week, on average. The pain never goes away for more than 3 weeks in a year’s time, hence the reason for his chronic cluster headache diagnosis. He is now using nVNS as soon as he feels the pain coming on. If the device does not provide sufficient relief, he uses oxygen or takes the sumatriptan injection.

Some patients who get cluster headaches think of suicide if the pain cannot be stopped; but in my experience, most can become pain free, or at least realize some partial relief from a variety of treatments (sometimes given at the same time).

Doctors often do not think of devices as options, and some doctors think devices do not work even though they have no experience with using them. Devices can give good relief on their own, and when a severe headache needs stronger treatment, medications added to a device usually work better than either treatment alone.

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.

One chronic cluster patient has relied on subcutaneous sumatriptan and breathing 100% oxygen at 12 liters per minute through a mask over his nose and mouth for acute relief from his headaches. His headache pain can climb from a 3 to a 10 in a matter of minutes. It starts behind and a bit above the right eye where he feels a tremendous pressure building up. He says that at times it feels like a screwdriver has been thrust into his eye and is being turned. Along with the pain, the eye becomes red, the pupil constricts, and the eyelid droops. He also has dripping from the right nostril, which stuffs up when the pain abates. The pain lasts for 1 to 2 hours, then returns 3 to 5 times a day for 5 days a week, on average. The pain never goes away for more than 3 weeks in a year’s time, hence the reason for his chronic cluster headache diagnosis. He is now using nVNS as soon as he feels the pain coming on. If the device does not provide sufficient relief, he uses oxygen or takes the sumatriptan injection.

Some patients who get cluster headaches think of suicide if the pain cannot be stopped; but in my experience, most can become pain free, or at least realize some partial relief from a variety of treatments (sometimes given at the same time).

Doctors often do not think of devices as options, and some doctors think devices do not work even though they have no experience with using them. Devices can give good relief on their own, and when a severe headache needs stronger treatment, medications added to a device usually work better than either treatment alone.

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE