User login

USPSTF: Screen all pregnant women for syphilis

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a draft recommendation that all pregnant women be screened for syphilis infection.

The recommendation, released Feb. 6, follows an evidence review of studies conducted since the task force’s most recent recommendation in 2009, which also called for universal screening of pregnant women.

“Despite consistent recommendations and legal mandates, screening for syphilis in pregnancy continues to be suboptimal in certain populations,” the evidence review noted. The rate of congenital syphilis in the United States nearly doubled from 2012 to 2016.

“Because the early stages of syphilis often don’t cause any symptoms, screening helps identify the infection in pregnant women who may not realize they have the disease,” task force member Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, of the University of Hawaii, said in a statement.

Treatment is most effective early in pregnancy, and can reduce the chances of congenital syphilis. The draft recommendation calls for pregnant women to be tested at the first prenatal visit or at delivery, if the woman has not received prenatal care.

Comments can be submitted until March 5 at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

[email protected]

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a draft recommendation that all pregnant women be screened for syphilis infection.

The recommendation, released Feb. 6, follows an evidence review of studies conducted since the task force’s most recent recommendation in 2009, which also called for universal screening of pregnant women.

“Despite consistent recommendations and legal mandates, screening for syphilis in pregnancy continues to be suboptimal in certain populations,” the evidence review noted. The rate of congenital syphilis in the United States nearly doubled from 2012 to 2016.

“Because the early stages of syphilis often don’t cause any symptoms, screening helps identify the infection in pregnant women who may not realize they have the disease,” task force member Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, of the University of Hawaii, said in a statement.

Treatment is most effective early in pregnancy, and can reduce the chances of congenital syphilis. The draft recommendation calls for pregnant women to be tested at the first prenatal visit or at delivery, if the woman has not received prenatal care.

Comments can be submitted until March 5 at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

[email protected]

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a draft recommendation that all pregnant women be screened for syphilis infection.

The recommendation, released Feb. 6, follows an evidence review of studies conducted since the task force’s most recent recommendation in 2009, which also called for universal screening of pregnant women.

“Despite consistent recommendations and legal mandates, screening for syphilis in pregnancy continues to be suboptimal in certain populations,” the evidence review noted. The rate of congenital syphilis in the United States nearly doubled from 2012 to 2016.

“Because the early stages of syphilis often don’t cause any symptoms, screening helps identify the infection in pregnant women who may not realize they have the disease,” task force member Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, of the University of Hawaii, said in a statement.

Treatment is most effective early in pregnancy, and can reduce the chances of congenital syphilis. The draft recommendation calls for pregnant women to be tested at the first prenatal visit or at delivery, if the woman has not received prenatal care.

Comments can be submitted until March 5 at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

[email protected]

ASCO expands recommendations on bone-modifying agents in myeloma

Bisphosphonates should be prescribed for any patient receiving treatment for active multiple myeloma, regardless of whether or not there is evidence of lytic bone destruction or spinal compression fracture, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Previous guidelines from the society, last updated in 2007, recommended the use of intravenous bisphosphonates for patients with myeloma with evidence of bone disease, according to the expert panel that drafted the update.

“Fewer adverse events related to renal toxicity have been noted with denosumab, compared with zoledronic acid,” and “this may be preferred in patients with compromised renal function,” wrote the expert panel, led by cochairs Kenneth C. Anderson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Robert A. Kyle, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

ASCO guidelines on bisphosphonates in myeloma were first drafted in 2002 and then updated in 2007. The new recommendations on bone-modifying therapy in myeloma are based on review of an additional 35 publications. The new guidelines are “consistent with the previous recommendations” while updating indications for therapy and information on denosumab, according to the expert panel.

Evidence that myeloma patients without lytic bone disease will benefit from intravenous bisphosphonates comes from the randomized MRC IX trial, in which patients who received zoledronic acid had reduced skeletal-related events at relapse and improved progression-free survival.

Denosumab, a receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) inhibitor, was noninferior to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events in a randomized phase 3 clinical trial; however, it is “more expensive than zoledronic acid or pamidronate and must be considered in treatment decisions,” the guidelines authors wrote.

The total price in the United States for a 1-year treatment cycle of denosumab is just under $26,000, according to data included in the ASCO guideline. By comparison, the 1-year treatment cycle price for the bisphosphonates ranges from $214 to $697, depending on the regimen.

When intravenous bisphosphonate therapy is warranted, the guideline-recommended schedule is infusion of zoledronic acid 4 mg over at least 15 minutes, or pamidronate 90 mg over 2 hours, every 3-4 weeks.

The guidelines also address osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a major complication observed not only with the potent bisphosphonates pamidronate and zoledronic acid, but also with denosumab.

The panel said they were in agreement with revised labels from the Food and Drug Administration for zoledronic acid and pamidronate, among other papers or statements addressing ONJ and noted that patients need a comprehensive dental exam and preventive dentistry as appropriate before starting bone-modifying therapy.

“The risk of ONJ has prompted the use of less-frequent dosing of zoledronic acid, which may be an option for patients,” they said in their report.

Guideline authors reported ties to Amgen, Celgene, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Anderson K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17:JCO2017766402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6402.

Bisphosphonates should be prescribed for any patient receiving treatment for active multiple myeloma, regardless of whether or not there is evidence of lytic bone destruction or spinal compression fracture, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Previous guidelines from the society, last updated in 2007, recommended the use of intravenous bisphosphonates for patients with myeloma with evidence of bone disease, according to the expert panel that drafted the update.

“Fewer adverse events related to renal toxicity have been noted with denosumab, compared with zoledronic acid,” and “this may be preferred in patients with compromised renal function,” wrote the expert panel, led by cochairs Kenneth C. Anderson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Robert A. Kyle, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

ASCO guidelines on bisphosphonates in myeloma were first drafted in 2002 and then updated in 2007. The new recommendations on bone-modifying therapy in myeloma are based on review of an additional 35 publications. The new guidelines are “consistent with the previous recommendations” while updating indications for therapy and information on denosumab, according to the expert panel.

Evidence that myeloma patients without lytic bone disease will benefit from intravenous bisphosphonates comes from the randomized MRC IX trial, in which patients who received zoledronic acid had reduced skeletal-related events at relapse and improved progression-free survival.

Denosumab, a receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) inhibitor, was noninferior to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events in a randomized phase 3 clinical trial; however, it is “more expensive than zoledronic acid or pamidronate and must be considered in treatment decisions,” the guidelines authors wrote.

The total price in the United States for a 1-year treatment cycle of denosumab is just under $26,000, according to data included in the ASCO guideline. By comparison, the 1-year treatment cycle price for the bisphosphonates ranges from $214 to $697, depending on the regimen.

When intravenous bisphosphonate therapy is warranted, the guideline-recommended schedule is infusion of zoledronic acid 4 mg over at least 15 minutes, or pamidronate 90 mg over 2 hours, every 3-4 weeks.

The guidelines also address osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a major complication observed not only with the potent bisphosphonates pamidronate and zoledronic acid, but also with denosumab.

The panel said they were in agreement with revised labels from the Food and Drug Administration for zoledronic acid and pamidronate, among other papers or statements addressing ONJ and noted that patients need a comprehensive dental exam and preventive dentistry as appropriate before starting bone-modifying therapy.

“The risk of ONJ has prompted the use of less-frequent dosing of zoledronic acid, which may be an option for patients,” they said in their report.

Guideline authors reported ties to Amgen, Celgene, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Anderson K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17:JCO2017766402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6402.

Bisphosphonates should be prescribed for any patient receiving treatment for active multiple myeloma, regardless of whether or not there is evidence of lytic bone destruction or spinal compression fracture, according to updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Previous guidelines from the society, last updated in 2007, recommended the use of intravenous bisphosphonates for patients with myeloma with evidence of bone disease, according to the expert panel that drafted the update.

“Fewer adverse events related to renal toxicity have been noted with denosumab, compared with zoledronic acid,” and “this may be preferred in patients with compromised renal function,” wrote the expert panel, led by cochairs Kenneth C. Anderson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and Robert A. Kyle, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

ASCO guidelines on bisphosphonates in myeloma were first drafted in 2002 and then updated in 2007. The new recommendations on bone-modifying therapy in myeloma are based on review of an additional 35 publications. The new guidelines are “consistent with the previous recommendations” while updating indications for therapy and information on denosumab, according to the expert panel.

Evidence that myeloma patients without lytic bone disease will benefit from intravenous bisphosphonates comes from the randomized MRC IX trial, in which patients who received zoledronic acid had reduced skeletal-related events at relapse and improved progression-free survival.

Denosumab, a receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) inhibitor, was noninferior to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events in a randomized phase 3 clinical trial; however, it is “more expensive than zoledronic acid or pamidronate and must be considered in treatment decisions,” the guidelines authors wrote.

The total price in the United States for a 1-year treatment cycle of denosumab is just under $26,000, according to data included in the ASCO guideline. By comparison, the 1-year treatment cycle price for the bisphosphonates ranges from $214 to $697, depending on the regimen.

When intravenous bisphosphonate therapy is warranted, the guideline-recommended schedule is infusion of zoledronic acid 4 mg over at least 15 minutes, or pamidronate 90 mg over 2 hours, every 3-4 weeks.

The guidelines also address osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a major complication observed not only with the potent bisphosphonates pamidronate and zoledronic acid, but also with denosumab.

The panel said they were in agreement with revised labels from the Food and Drug Administration for zoledronic acid and pamidronate, among other papers or statements addressing ONJ and noted that patients need a comprehensive dental exam and preventive dentistry as appropriate before starting bone-modifying therapy.

“The risk of ONJ has prompted the use of less-frequent dosing of zoledronic acid, which may be an option for patients,” they said in their report.

Guideline authors reported ties to Amgen, Celgene, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Anderson K et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17:JCO2017766402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6402.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

nPEP for HIV: Updated CDC guidelines available for primary care physicians

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

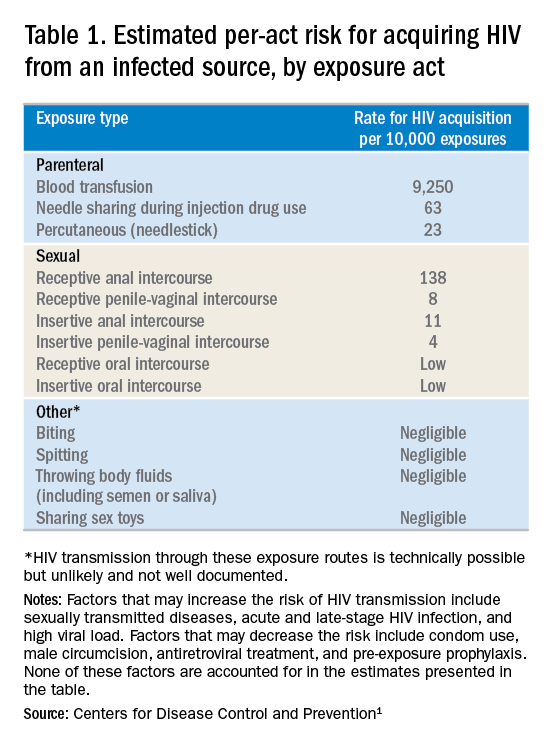

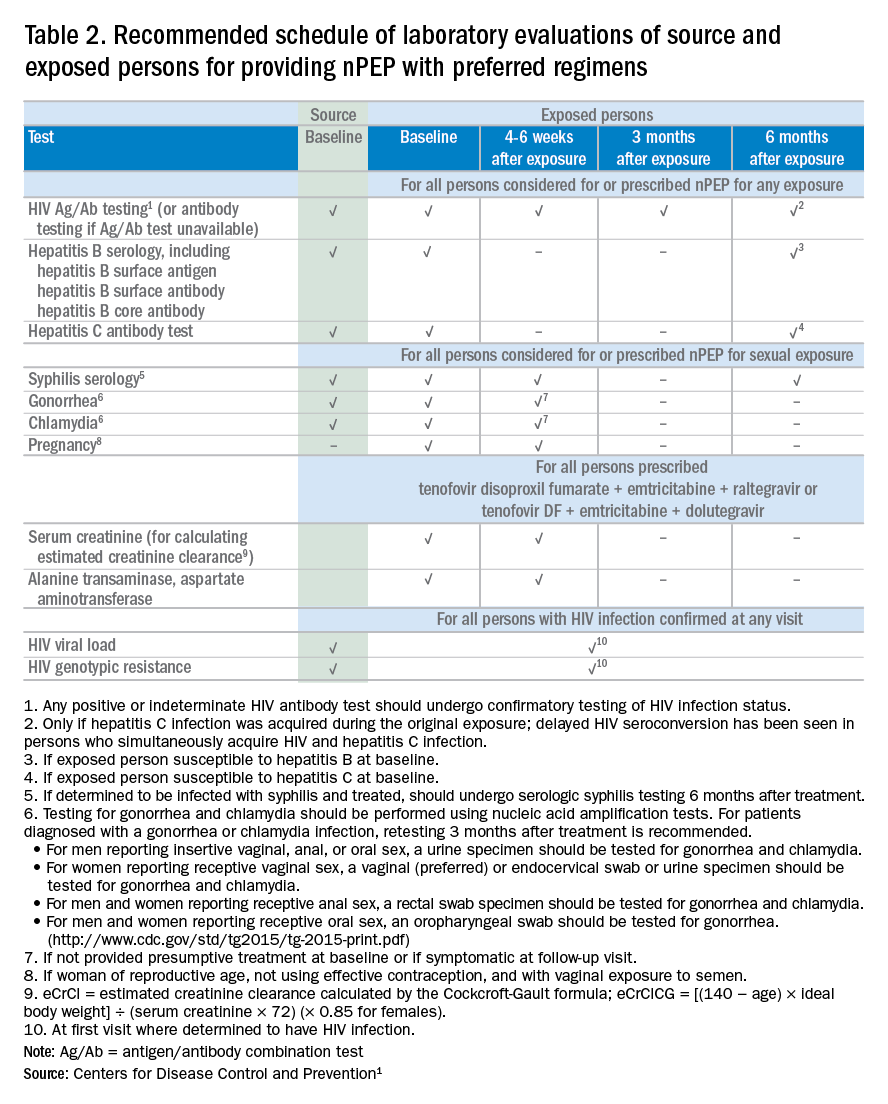

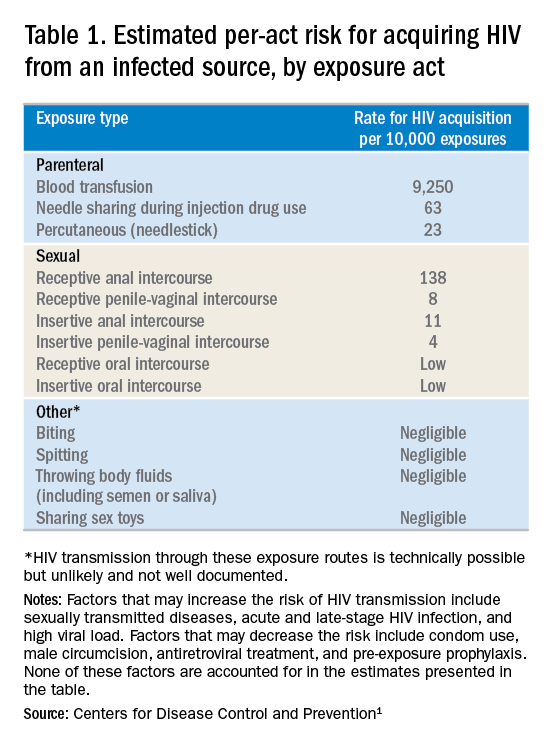

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

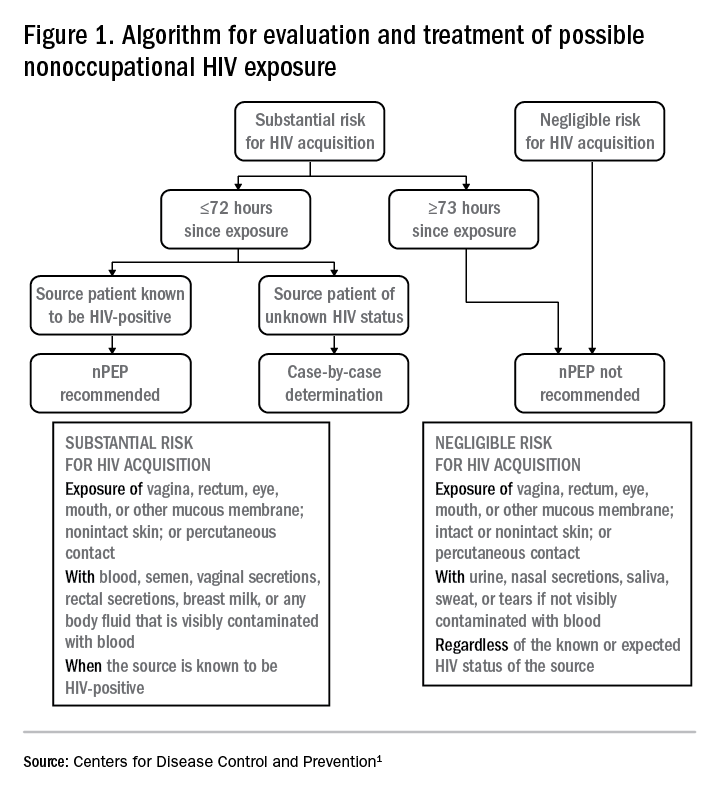

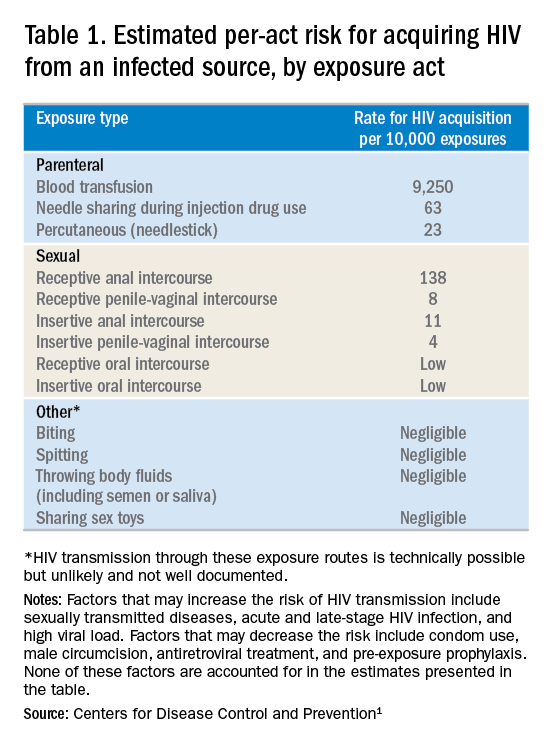

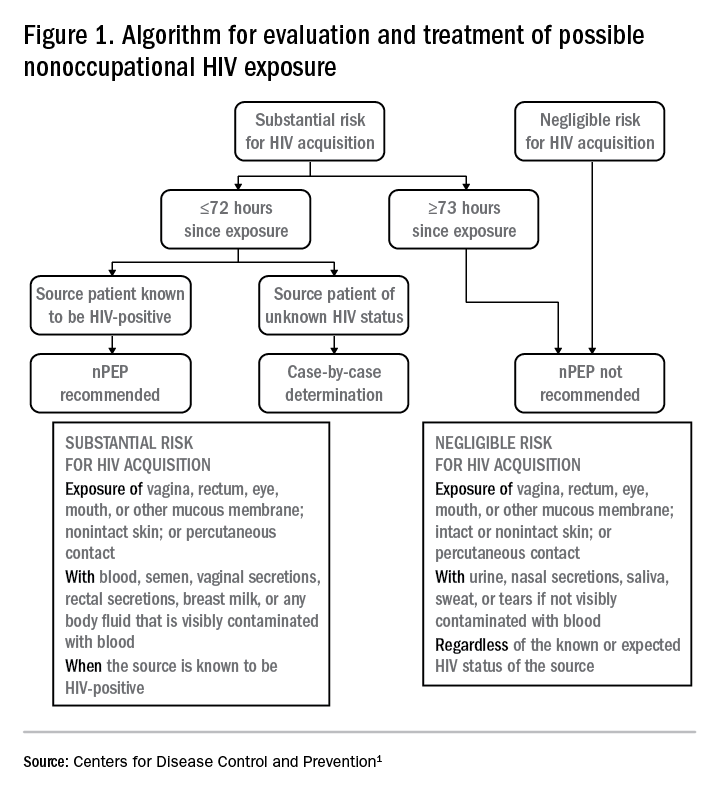

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

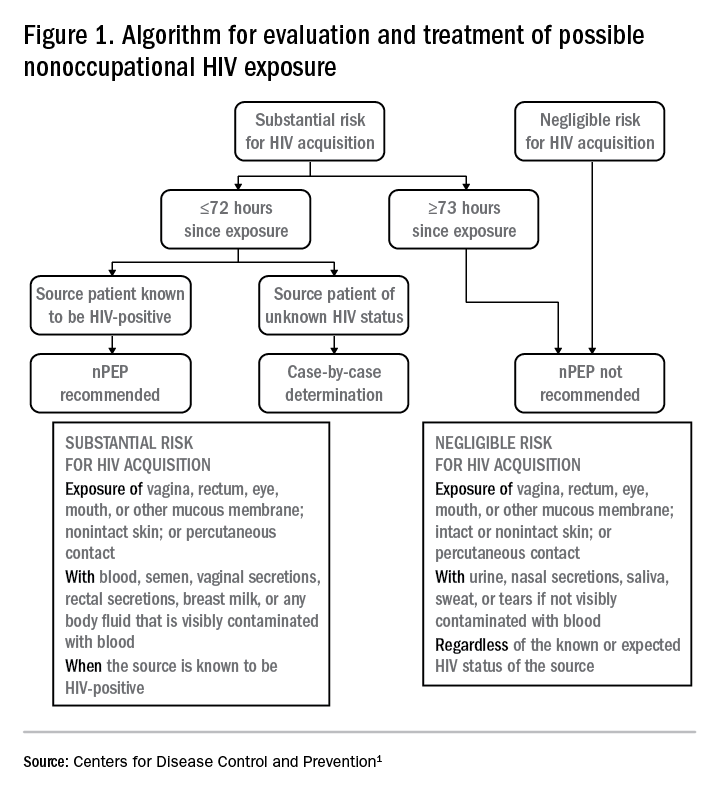

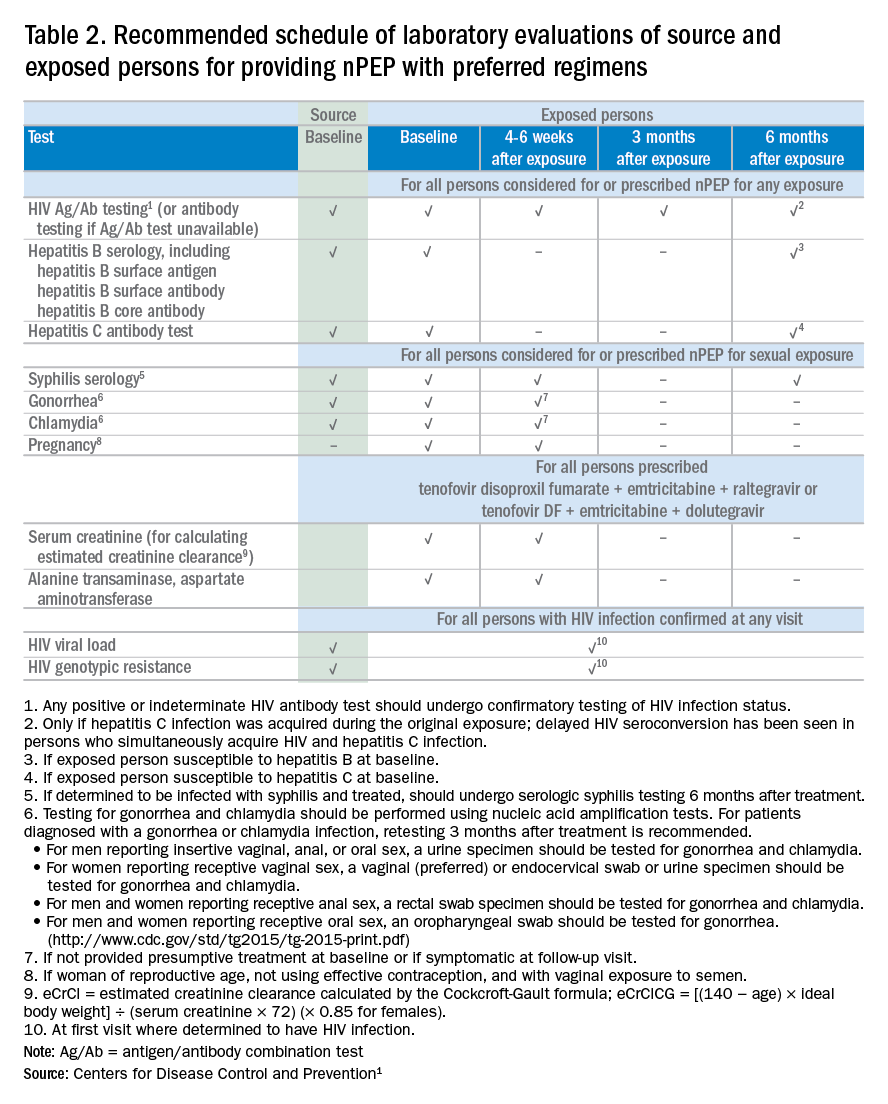

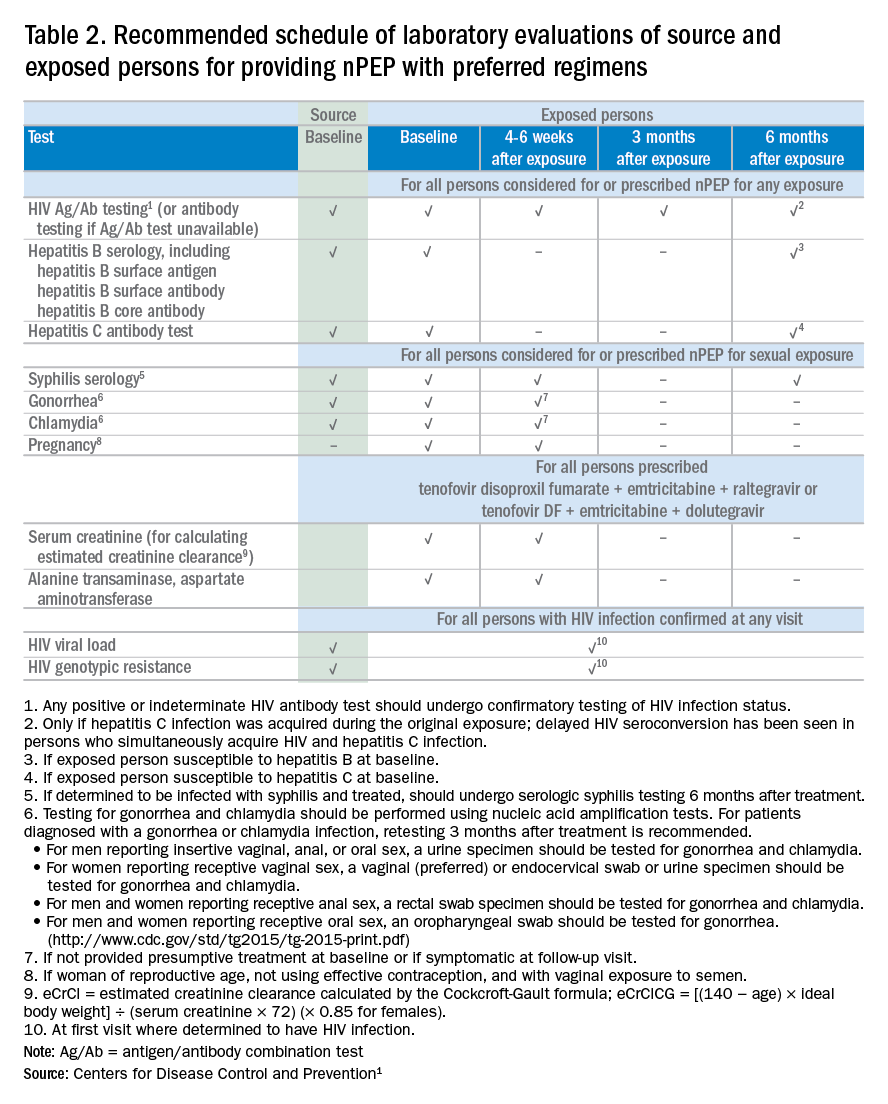

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

AHA: Heart health helps optimize breast cancer outcomes

Breast cancer outcomes rely on “coexisting cardiovascular health” at every step in the patient journey, the American Heart Association has said in its first-ever scientific statement on the matter.

The statement, published in Circulation provides a comprehensive overview of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer prevalence and shared risk factors, as well as current recommendations on avoiding the cardiotoxic effects of some cancer treatments and strategies to prevent or treat CVD in breast cancer patients.

Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer are two entities that are frequently intertwined, Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, chair of the statement writing group, said in an interview.

“For any oncologic patient, it’s important to also consider their heart in the risk assessment because that also affects survival from the cancer,” said Dr. Mehta, the director of the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Program and an associate professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Mortality risk attributable to CVD is higher in breast cancer survivors than in women who have no history of breast cancer, according to evidence Dr. Mehta and her colleagues cite in the statement.

Breast cancer and CVD share a number of common and sometimes modifiable risk factors, including dietary patterns, physical activity, and being overweight or obese, and tobacco use. There is “growing awareness” that modifying those risk factors may help prevent some cases of breast cancer.

Even in patients who have a breast cancer diagnosis, “from a cardiology standpoint, lifestyle is going to be key,” said Dr. Mehta. She said breast cancer patients can be encouraged to follow AHA recommendations to aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly and to follow an “overall healthy dietary pattern” that limits saturated and trans fats, sodium, red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Although left ventricular systolic dysfunction is the most common cardiovascular side effect associated with chemotherapy, other manifestations of early or delayed cardiotoxicity can include heart failure, hypertension, thromboembolic disease, pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocardial ischemia, according to the AHA scientific statement.

A wide range of standard breast cancer treatments cause cardiovascular adverse effects, including taxanes such as paclitaxel, anthracyclines such as doxorubicin, and alkylating agents such as cisplatin and cyclophosphamide, as outlined in the statement.

Targeted HER-2–directed therapies, including trastuzumab and pertuzumab, are associated with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure, while emerging therapies, such as the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors palbociclib and ribociclib, are associated with QTc prolongation, the statement also notes.

Current strategies for monitoring for cardiovascular toxicity, which typically involve myocardial strain imaging, assessing cardiac biomarkers, or a combination of imaging and biomarkers, are outlined in the report.

To mitigate the impact of cancer treatments on cardiovascular health, several oncologic strategies are useful, according to Dr. Mehta and colleagues.

In multiple clinical trials of breast cancer patients receiving doxorubicin or epirubicin, the iron-binding agent dexrazoxane reduced the combined endpoint of decreased left ventricular ejection fraction or development of heart failure, the authors said.

Likewise, clinical trial evidence has suggested cardiotoxicity associated with doxorubicin can be mitigated through administration via infusion as opposed to bolus and with longer versus shorter infusion durations, they continued.

Extreme cases or difficult-to-manage patients can be referred to a center that has an active program in cardio-oncology, a newer and rapidly expanding field, according to Dr. Mehta.

“That’s where there’s tight collaboration in terms of understanding the current treatments, and that’s also where research on how to best take care of these patients will be conducted,” she said.

Dr. Mehta reported no disclosures. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Roche, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Mehta LS et al. Circulation. 2017 Jan 22. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000556.

Breast cancer outcomes rely on “coexisting cardiovascular health” at every step in the patient journey, the American Heart Association has said in its first-ever scientific statement on the matter.

The statement, published in Circulation provides a comprehensive overview of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer prevalence and shared risk factors, as well as current recommendations on avoiding the cardiotoxic effects of some cancer treatments and strategies to prevent or treat CVD in breast cancer patients.

Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer are two entities that are frequently intertwined, Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, chair of the statement writing group, said in an interview.

“For any oncologic patient, it’s important to also consider their heart in the risk assessment because that also affects survival from the cancer,” said Dr. Mehta, the director of the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Program and an associate professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Mortality risk attributable to CVD is higher in breast cancer survivors than in women who have no history of breast cancer, according to evidence Dr. Mehta and her colleagues cite in the statement.

Breast cancer and CVD share a number of common and sometimes modifiable risk factors, including dietary patterns, physical activity, and being overweight or obese, and tobacco use. There is “growing awareness” that modifying those risk factors may help prevent some cases of breast cancer.

Even in patients who have a breast cancer diagnosis, “from a cardiology standpoint, lifestyle is going to be key,” said Dr. Mehta. She said breast cancer patients can be encouraged to follow AHA recommendations to aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly and to follow an “overall healthy dietary pattern” that limits saturated and trans fats, sodium, red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Although left ventricular systolic dysfunction is the most common cardiovascular side effect associated with chemotherapy, other manifestations of early or delayed cardiotoxicity can include heart failure, hypertension, thromboembolic disease, pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocardial ischemia, according to the AHA scientific statement.

A wide range of standard breast cancer treatments cause cardiovascular adverse effects, including taxanes such as paclitaxel, anthracyclines such as doxorubicin, and alkylating agents such as cisplatin and cyclophosphamide, as outlined in the statement.

Targeted HER-2–directed therapies, including trastuzumab and pertuzumab, are associated with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure, while emerging therapies, such as the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors palbociclib and ribociclib, are associated with QTc prolongation, the statement also notes.

Current strategies for monitoring for cardiovascular toxicity, which typically involve myocardial strain imaging, assessing cardiac biomarkers, or a combination of imaging and biomarkers, are outlined in the report.

To mitigate the impact of cancer treatments on cardiovascular health, several oncologic strategies are useful, according to Dr. Mehta and colleagues.

In multiple clinical trials of breast cancer patients receiving doxorubicin or epirubicin, the iron-binding agent dexrazoxane reduced the combined endpoint of decreased left ventricular ejection fraction or development of heart failure, the authors said.

Likewise, clinical trial evidence has suggested cardiotoxicity associated with doxorubicin can be mitigated through administration via infusion as opposed to bolus and with longer versus shorter infusion durations, they continued.

Extreme cases or difficult-to-manage patients can be referred to a center that has an active program in cardio-oncology, a newer and rapidly expanding field, according to Dr. Mehta.

“That’s where there’s tight collaboration in terms of understanding the current treatments, and that’s also where research on how to best take care of these patients will be conducted,” she said.

Dr. Mehta reported no disclosures. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Roche, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Mehta LS et al. Circulation. 2017 Jan 22. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000556.

Breast cancer outcomes rely on “coexisting cardiovascular health” at every step in the patient journey, the American Heart Association has said in its first-ever scientific statement on the matter.

The statement, published in Circulation provides a comprehensive overview of cardiovascular disease and breast cancer prevalence and shared risk factors, as well as current recommendations on avoiding the cardiotoxic effects of some cancer treatments and strategies to prevent or treat CVD in breast cancer patients.

Cardiovascular disease and breast cancer are two entities that are frequently intertwined, Laxmi S. Mehta, MD, chair of the statement writing group, said in an interview.

“For any oncologic patient, it’s important to also consider their heart in the risk assessment because that also affects survival from the cancer,” said Dr. Mehta, the director of the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Program and an associate professor of medicine at the Ohio State University, Columbus.

Mortality risk attributable to CVD is higher in breast cancer survivors than in women who have no history of breast cancer, according to evidence Dr. Mehta and her colleagues cite in the statement.

Breast cancer and CVD share a number of common and sometimes modifiable risk factors, including dietary patterns, physical activity, and being overweight or obese, and tobacco use. There is “growing awareness” that modifying those risk factors may help prevent some cases of breast cancer.

Even in patients who have a breast cancer diagnosis, “from a cardiology standpoint, lifestyle is going to be key,” said Dr. Mehta. She said breast cancer patients can be encouraged to follow AHA recommendations to aim for 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly and to follow an “overall healthy dietary pattern” that limits saturated and trans fats, sodium, red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

Although left ventricular systolic dysfunction is the most common cardiovascular side effect associated with chemotherapy, other manifestations of early or delayed cardiotoxicity can include heart failure, hypertension, thromboembolic disease, pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocardial ischemia, according to the AHA scientific statement.

A wide range of standard breast cancer treatments cause cardiovascular adverse effects, including taxanes such as paclitaxel, anthracyclines such as doxorubicin, and alkylating agents such as cisplatin and cyclophosphamide, as outlined in the statement.

Targeted HER-2–directed therapies, including trastuzumab and pertuzumab, are associated with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure, while emerging therapies, such as the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors palbociclib and ribociclib, are associated with QTc prolongation, the statement also notes.

Current strategies for monitoring for cardiovascular toxicity, which typically involve myocardial strain imaging, assessing cardiac biomarkers, or a combination of imaging and biomarkers, are outlined in the report.

To mitigate the impact of cancer treatments on cardiovascular health, several oncologic strategies are useful, according to Dr. Mehta and colleagues.

In multiple clinical trials of breast cancer patients receiving doxorubicin or epirubicin, the iron-binding agent dexrazoxane reduced the combined endpoint of decreased left ventricular ejection fraction or development of heart failure, the authors said.

Likewise, clinical trial evidence has suggested cardiotoxicity associated with doxorubicin can be mitigated through administration via infusion as opposed to bolus and with longer versus shorter infusion durations, they continued.

Extreme cases or difficult-to-manage patients can be referred to a center that has an active program in cardio-oncology, a newer and rapidly expanding field, according to Dr. Mehta.

“That’s where there’s tight collaboration in terms of understanding the current treatments, and that’s also where research on how to best take care of these patients will be conducted,” she said.

Dr. Mehta reported no disclosures. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Roche, Novartis, and others.

SOURCE: Mehta LS et al. Circulation. 2017 Jan 22. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000556.

FROM CIRCULATION

VIDEO: New stroke guideline embraces imaging-guided thrombectomy

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ISC 2018

AAD guidelines favor surgery for nonmelanoma skin cancers

, according to new practice guidelines issued by the American Academy of Dermatology.

Nonsurgical approaches such as cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and radiation may be considered for low-risk cancers if surgery is contraindicated, but these methods have lower cure rates, according to the guidelines. Christopher K. Bichakjian, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, cochaired the work groups that developed the guidelines.

The guidelines for BCC and cSCC, published online in two separate papers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.006; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.007), also discuss biopsy techniques, tumor staging, and prevention of recurrence of nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The most suitable stratification for localized BCC and cSCC is the framework provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the authors said in the guidelines.

For suspected BCC and cSCC, recommended biopsy techniques are punch biopsy, shave biopsy, and excisional biopsy. Biopsy technique is “contingent on the clinical characteristics of the suspected tumor, including morphology, expected histologic subtype and depth, natural history, and anatomic location; patient-specific factors, such as bleeding and wound healing diatheses; and patient preference and physician judgment,” the guidelines state. If the initial biopsy proves insufficient for diagnosis, a repeat biopsy may be considered.

For surgical treatment of BCC, curettage and electrodessication may be considered for low-risk tumors in nonterminal hair-bearing locations. Surgical excision with 4-mm clinical margins and histologic margin assessment is recommended for low-risk primary BCC. For high-risk BCC, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended, the authors said.

Surgical options for cSCC also include curettage and electrodessication and standard excision for low-risk disease, and Mohs micrographic surgery for high-risk cSCC. In both BCC and cSCC, standard excision may be considered for high-risk tumors in some cases, but “strong caution is advised when selecting a treatment modality” for high-risk tumors “without complete margin assessment,” the guidelines state.

Nonsurgical therapies are generally not recommended as first-line treatment, especially in cSCC because of possible recurrence and metastasis. In cases where nonsurgical therapies are preferred, options may include cryosurgery, topical therapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation, or laser therapy, “with the understanding that the cure rate may be lower,” the authors wrote.

Patients with diagnosed nonmelanoma skin cancer should continue to undergo screening for new primary skin cancers (including BCC, cSCC, and melanoma) at least once per year, the guideline states. They should also be counseled on sun protection, tanning bed avoidance, and regular use of broad-spectrum sunscreen.

Although the new guidelines mainly “reaffirm common knowledge and current practice,” they offer a reminder of “alternative therapeutic or preventive options when insufficient evidence is available to support new therapies or previously dogmatic practice patterns,” the authors said.

These are the first guidelines of care for BCC and cSCC published by the AAD. Commonly used guidelines for the management of BCC and cSCC are published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which are frequently referenced throughout the new AAD guidelines, Dr. Bichakjian said in an interview. While the aim of the cancer network is to develop multidisciplinary guidelines, reflected by the composition of the panel members, “AAD guidelines of care are established primarily by dermatologists for dermatologists,” he pointed out. “However, the work group recognizes that a variety of health care providers outside of dermatology take care of patients with BCC and cSCC, and acknowledges the importance of multidisciplinary care,” he added. “With these considerations in mind, reviewers from specialties outside of dermatology, including plastic surgery, otolaryngology/head and neck surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and family medicine, were invited to critically review the current guidelines.”

The guidelines do not cover the management of actinic keratosis and cSCC in situ, he said. “The work group acknowledges the importance of appropriate management of premalignant and in situ lesions in the prevention of their potential progression to cSCC. However, additional data to provide comprehensive evidence-based recommendations were deemed too extensive to include in the current guidelines and will need to addressed separately.”

In an interview, David J. Leffell, MD, who was not an author of the guidelines, said that the new guidelines do an effective job of “highlighting where valid outcomes data exist and areas where they do not” for a wide range of therapies. They also “attempt to standardize approaches to diagnosis and care of nonmelanoma skin cancer and in general are consistent with established practice patterns,” he added. “Those contemporary approaches have developed in largely empirical fashion over many decades, but bear clarification and reinforcement,” said Dr. Leffell, professor of dermatology and surgery and chief of the section of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The guidelines “thoroughly summarize evidence-based recommendations for the entire spectrum of disease management,” Daniel D. Bennett, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, said in an interview. “While surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for BCC and cutaneous SCC, these guidelines include excellent reviews of nonsurgical management options,” he said.

Dr. Bichakjian, who is also chief of the division of cutaneous surgery and oncology at the University of Michigan, had no relevant financial disclosures to report. Dr. Alam, who is also chief of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery in the department of dermatology at Northwestern, disclosed relationships with Amway, OptMed, and 3M. Dr. Bennett and Dr. Leffell had no relevant disclosures.

, according to new practice guidelines issued by the American Academy of Dermatology.

Nonsurgical approaches such as cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and radiation may be considered for low-risk cancers if surgery is contraindicated, but these methods have lower cure rates, according to the guidelines. Christopher K. Bichakjian, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, cochaired the work groups that developed the guidelines.

The guidelines for BCC and cSCC, published online in two separate papers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.006; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.007), also discuss biopsy techniques, tumor staging, and prevention of recurrence of nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The most suitable stratification for localized BCC and cSCC is the framework provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the authors said in the guidelines.

For suspected BCC and cSCC, recommended biopsy techniques are punch biopsy, shave biopsy, and excisional biopsy. Biopsy technique is “contingent on the clinical characteristics of the suspected tumor, including morphology, expected histologic subtype and depth, natural history, and anatomic location; patient-specific factors, such as bleeding and wound healing diatheses; and patient preference and physician judgment,” the guidelines state. If the initial biopsy proves insufficient for diagnosis, a repeat biopsy may be considered.

For surgical treatment of BCC, curettage and electrodessication may be considered for low-risk tumors in nonterminal hair-bearing locations. Surgical excision with 4-mm clinical margins and histologic margin assessment is recommended for low-risk primary BCC. For high-risk BCC, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended, the authors said.

Surgical options for cSCC also include curettage and electrodessication and standard excision for low-risk disease, and Mohs micrographic surgery for high-risk cSCC. In both BCC and cSCC, standard excision may be considered for high-risk tumors in some cases, but “strong caution is advised when selecting a treatment modality” for high-risk tumors “without complete margin assessment,” the guidelines state.

Nonsurgical therapies are generally not recommended as first-line treatment, especially in cSCC because of possible recurrence and metastasis. In cases where nonsurgical therapies are preferred, options may include cryosurgery, topical therapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation, or laser therapy, “with the understanding that the cure rate may be lower,” the authors wrote.

Patients with diagnosed nonmelanoma skin cancer should continue to undergo screening for new primary skin cancers (including BCC, cSCC, and melanoma) at least once per year, the guideline states. They should also be counseled on sun protection, tanning bed avoidance, and regular use of broad-spectrum sunscreen.

Although the new guidelines mainly “reaffirm common knowledge and current practice,” they offer a reminder of “alternative therapeutic or preventive options when insufficient evidence is available to support new therapies or previously dogmatic practice patterns,” the authors said.

These are the first guidelines of care for BCC and cSCC published by the AAD. Commonly used guidelines for the management of BCC and cSCC are published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which are frequently referenced throughout the new AAD guidelines, Dr. Bichakjian said in an interview. While the aim of the cancer network is to develop multidisciplinary guidelines, reflected by the composition of the panel members, “AAD guidelines of care are established primarily by dermatologists for dermatologists,” he pointed out. “However, the work group recognizes that a variety of health care providers outside of dermatology take care of patients with BCC and cSCC, and acknowledges the importance of multidisciplinary care,” he added. “With these considerations in mind, reviewers from specialties outside of dermatology, including plastic surgery, otolaryngology/head and neck surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and family medicine, were invited to critically review the current guidelines.”

The guidelines do not cover the management of actinic keratosis and cSCC in situ, he said. “The work group acknowledges the importance of appropriate management of premalignant and in situ lesions in the prevention of their potential progression to cSCC. However, additional data to provide comprehensive evidence-based recommendations were deemed too extensive to include in the current guidelines and will need to addressed separately.”

In an interview, David J. Leffell, MD, who was not an author of the guidelines, said that the new guidelines do an effective job of “highlighting where valid outcomes data exist and areas where they do not” for a wide range of therapies. They also “attempt to standardize approaches to diagnosis and care of nonmelanoma skin cancer and in general are consistent with established practice patterns,” he added. “Those contemporary approaches have developed in largely empirical fashion over many decades, but bear clarification and reinforcement,” said Dr. Leffell, professor of dermatology and surgery and chief of the section of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The guidelines “thoroughly summarize evidence-based recommendations for the entire spectrum of disease management,” Daniel D. Bennett, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison, said in an interview. “While surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for BCC and cutaneous SCC, these guidelines include excellent reviews of nonsurgical management options,” he said.

Dr. Bichakjian, who is also chief of the division of cutaneous surgery and oncology at the University of Michigan, had no relevant financial disclosures to report. Dr. Alam, who is also chief of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery in the department of dermatology at Northwestern, disclosed relationships with Amway, OptMed, and 3M. Dr. Bennett and Dr. Leffell had no relevant disclosures.

, according to new practice guidelines issued by the American Academy of Dermatology.

Nonsurgical approaches such as cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and radiation may be considered for low-risk cancers if surgery is contraindicated, but these methods have lower cure rates, according to the guidelines. Christopher K. Bichakjian, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Murad Alam, MD, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, cochaired the work groups that developed the guidelines.

The guidelines for BCC and cSCC, published online in two separate papers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.006; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan. 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.007), also discuss biopsy techniques, tumor staging, and prevention of recurrence of nonmelanoma skin cancers.

The most suitable stratification for localized BCC and cSCC is the framework provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the authors said in the guidelines.

For suspected BCC and cSCC, recommended biopsy techniques are punch biopsy, shave biopsy, and excisional biopsy. Biopsy technique is “contingent on the clinical characteristics of the suspected tumor, including morphology, expected histologic subtype and depth, natural history, and anatomic location; patient-specific factors, such as bleeding and wound healing diatheses; and patient preference and physician judgment,” the guidelines state. If the initial biopsy proves insufficient for diagnosis, a repeat biopsy may be considered.

For surgical treatment of BCC, curettage and electrodessication may be considered for low-risk tumors in nonterminal hair-bearing locations. Surgical excision with 4-mm clinical margins and histologic margin assessment is recommended for low-risk primary BCC. For high-risk BCC, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended, the authors said.

Surgical options for cSCC also include curettage and electrodessication and standard excision for low-risk disease, and Mohs micrographic surgery for high-risk cSCC. In both BCC and cSCC, standard excision may be considered for high-risk tumors in some cases, but “strong caution is advised when selecting a treatment modality” for high-risk tumors “without complete margin assessment,” the guidelines state.

Nonsurgical therapies are generally not recommended as first-line treatment, especially in cSCC because of possible recurrence and metastasis. In cases where nonsurgical therapies are preferred, options may include cryosurgery, topical therapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation, or laser therapy, “with the understanding that the cure rate may be lower,” the authors wrote.

Patients with diagnosed nonmelanoma skin cancer should continue to undergo screening for new primary skin cancers (including BCC, cSCC, and melanoma) at least once per year, the guideline states. They should also be counseled on sun protection, tanning bed avoidance, and regular use of broad-spectrum sunscreen.

Although the new guidelines mainly “reaffirm common knowledge and current practice,” they offer a reminder of “alternative therapeutic or preventive options when insufficient evidence is available to support new therapies or previously dogmatic practice patterns,” the authors said.

These are the first guidelines of care for BCC and cSCC published by the AAD. Commonly used guidelines for the management of BCC and cSCC are published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which are frequently referenced throughout the new AAD guidelines, Dr. Bichakjian said in an interview. While the aim of the cancer network is to develop multidisciplinary guidelines, reflected by the composition of the panel members, “AAD guidelines of care are established primarily by dermatologists for dermatologists,” he pointed out. “However, the work group recognizes that a variety of health care providers outside of dermatology take care of patients with BCC and cSCC, and acknowledges the importance of multidisciplinary care,” he added. “With these considerations in mind, reviewers from specialties outside of dermatology, including plastic surgery, otolaryngology/head and neck surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and family medicine, were invited to critically review the current guidelines.”