User login

Labor & Delivery: An overlooked entry point for the spread of viral infection

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.

4. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(3):199-213.

5. Kwon JY, Romero R, Mor G. New insights into the relationship between viral infection and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:387-390.

6. BBC. Coronavirus: Newborn becomes youngest person diagnosed with virus. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

7. FDA press release. FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic. Feb 4, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Persons Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

9. STAT First Opinion. Two-thirds of pregnant women aren’t getting the flu vaccine. That needs to change. Jan 18, 2018.

10. CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, Key Updates for Week 5, ending February 1, 2020.

11. CDC. Vaccinating Pregnant Women Protects Moms and Babies. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

OB hospitalists have a key role to play

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.

4. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(3):199-213.

5. Kwon JY, Romero R, Mor G. New insights into the relationship between viral infection and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:387-390.

6. BBC. Coronavirus: Newborn becomes youngest person diagnosed with virus. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

7. FDA press release. FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic. Feb 4, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Persons Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

9. STAT First Opinion. Two-thirds of pregnant women aren’t getting the flu vaccine. That needs to change. Jan 18, 2018.

10. CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, Key Updates for Week 5, ending February 1, 2020.

11. CDC. Vaccinating Pregnant Women Protects Moms and Babies. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

A novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China, has killed more than 2,800 people and infected more than 81,000 individuals globally. Public health officials around the world and in the United States are working together to contain the outbreak.

There are 57 confirmed cases in the United States, including 18 people evacuated from the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan.1 But the focus on coronavirus, even in early months of the epidemic, serves as an opportunity to revisit the spread of viral disease in hospital settings.

Multiple points of viral entry

In truth, most hospitals are well prepared for the coronavirus, starting with the same place they prepare for most infectious disease epidemics – the emergency department. Patients who seek treatment for early onset symptoms may start with their primary care physicians, but increasing numbers of patients with respiratory concerns and/or infection-related symptoms will first seek medical attention in an emergency care setting.2

Many experts have acknowledged the ED as a viral point of entry, including the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), which produced an excellent guide for management of influenza that details prevention, diagnoses, and treatment protocols in an ED setting.3

But another important, and often forgotten, point of entry in a hospital setting is the obstetrical (OB) Labor & Delivery (L&D) department. Although triage for most patients begins in the main ED, in almost every hospital in the United States, women who present with pregnancy-related issues are sent directly to and triaged in L&D, where – when the proper protocols are not in place – they may transmit viral infection to others.

Pregnancy imparts higher risk

“High risk” is often associated with older, immune-compromised adults. But pregnant women who may appear “healthy” are actually in a state that a 2015 study calls “immunosuppressed” whereby the “… pregnant woman actually undergoes an immunological transformation, where the immune system is necessary to promote and support the pregnancy and growing fetus.”4 Pregnant women, or women with newborns or babies, are at higher risk when exposed to viral infection, with a higher mortality risk than the general population.5 In the best cases, women who contract viral infections are treated carefully and recover fully. In the worst cases, they end up on ventilators and can even die as a result.

Although we are still learning about the Wuhan coronavirus, we already know it is a respiratory illness with a lot of the same characteristics as the influenza virus, and that it is transmitted through droplets (such as a sneeze) or via bodily secretions. Given the extreme vulnerability and physician exposure of women giving birth – in which not one, but two lives are involved – viruses like coronavirus can pose extreme risk. What’s more, public health researchers are still learning about potential transmission of coronavirus from mothers to babies. In the international cases of infant exposure to coronavirus, the newborn showed symptoms within 36 hours of being born, but it is unclear if exposure happened in utero or was vertical transmission after birth.6

Role of OB hospitalists in identifying risk and treating viral infection

Regardless of the type of virus, OB hospitalists are key to screening for viral exposure and care for women, fetuses, and newborns. Given their 24/7 presence and experience with women in L&D, they must champion protocols and precautions that align with those in an ED.

For coronavirus, if a woman presents in L&D with a cough, difficulty breathing, or signs of pneumonia, clinicians should be accustomed to asking about travel to China within the last 14 days and whether the patient has been around someone who has recently traveled to China. If the answer to either question is yes, the woman needs to be immediately placed in a single patient room at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas, with a minimum of six air changes per hour.

Diagnostic testing should immediately follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration just issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the first commercially-available coronavirus diagnostic test, allowing the use of the test at any lab across the country qualified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.7

If exposure is suspected, containment is paramount until definitive results of diagnostic testing are received. The CDC recommends “Standard Precautions,” which assume that every person is potentially infected or colonized with a pathogen that could be transmitted in the health care setting. These precautions include hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure health care workers are not exposed.8

In short, protocols in L&D should mirror those of the ED. But in L&D, clinicians and staff haven’t necessarily been trained to look for or ask for these conditions. Hospitalists can educate their peers and colleagues and advocate for changes at the administrative level.

Biggest current threat: The flu

The coronavirus may eventually present a threat in the United States, but as yet, it is a largely unrealized one. From the perspective of an obstetrician, more immediately concerning is the risk of other viral infections. Although viruses like Ebola and Zika capture headlines, influenza remains the most serious threat to pregnant women in the United States.

According to an article by my colleague, Dr. Mark Simon, “pregnant women and their unborn babies are especially vulnerable to influenza and are more likely to develop serious complications from it … pregnant women who develop the flu are more likely to give birth to children with birth defects of the brain and spine.”9

As of Feb. 1, 2020, the CDC estimates there have been at least 22 million flu illnesses, 210,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000 deaths from flu in the 2019-2020 flu season.10 But the CDC data also suggest that only 54% of pregnant women were vaccinated for influenza in 2019 before or during their pregnancy.11 Hospitalists should ensure that patients diagnosed with flu are quickly and safely treated with antivirals at all stages of their pregnancy to keep them and their babies safe, as well as keep others safe from infection.

Hospitalists can also advocate for across-the-board protocols for the spread of viral illness. The same protocols that protect us from the flu will also protect against coronavirus and viruses that will emerge in the future. Foremost, pregnant women, regardless of trimester, need to receive a flu shot. Women who are pregnant and receive a flu shot can pass on immunity in vitro, and nursing mothers can deliver immunizing agents in their breast milk to their newborn.

Given that hospitalists serve in roles as patient-facing physicians, we should be doing more to protect the public from viral spread, whether coronavirus, influenza, or whatever new viruses the future may hold.

Dr. Dimino is a board-certified ob.gyn. and a Houston-based OB hospitalist with Ob Hospitalist Group. She serves as a faculty member of the TexasAIM Plus Obstetric Hemorrhage Learning Collaborative and currently serves on the Texas Medical Association Council of Science and Public Health.

References

1. The New York Times. Tracking the Coronavirus Map: Tracking the Spread of the Outbreak. Accessed Feb 24, 2020.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

3. Influenza Emergency Department Best Practices. ACEP Public Health & Injury Prevention Committee, Epidemic Expert Panel, https://www.acep.org/globalassets/uploads/uploaded-files/acep/by-medical-focus/influenza-emergency-department-best-practices.pdf.

4. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(3):199-213.

5. Kwon JY, Romero R, Mor G. New insights into the relationship between viral infection and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:387-390.

6. BBC. Coronavirus: Newborn becomes youngest person diagnosed with virus. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

7. FDA press release. FDA Takes Significant Step in Coronavirus Response Efforts, Issues Emergency Use Authorization for the First 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic. Feb 4, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Confirmed 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or Persons Under Investigation for 2019-nCoV in Healthcare Settings. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

9. STAT First Opinion. Two-thirds of pregnant women aren’t getting the flu vaccine. That needs to change. Jan 18, 2018.

10. CDC. Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, Key Updates for Week 5, ending February 1, 2020.

11. CDC. Vaccinating Pregnant Women Protects Moms and Babies. Accessed Feb 10, 2020.

Opioid use disorder up in sepsis hospitalizations

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

ORLANDO –

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) has significantly increased over the past 15 years, the analysis further shows.

Results of the study, presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, further suggested that OUD disproportionately contributes to sepsis deaths in younger, healthier patients.

Together, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing efforts to address the opioid epidemic in the United States, according to researcher Mohammad Alrawashdeh, PhD, MSN, a postdoctoral research fellow with Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

“In addition to ongoing efforts to combat the opioid crisis, future public health interventions should focus on increasing awareness, recognition, and aggressive treatment of sepsis in this population,” Dr. Alrawashdeh said in an oral presentation of the study.

This study fills an important knowledge gap regarding the connection between OUD and sepsis, according to Greg S. Martin, MD, MS, FCCM, professor of medicine in pulmonary critical care at Emory University, Atlanta, and secretary for the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

“We’ve not really ever been able to piece together the relationship between opioid use disorders and sepsis,” Dr. Martin said in an interview. “It’s not that people wouldn’t suspect that there’s a connection – it’s more that we have simply not been able to get the kind of data that you can use, like they’ve done here, that really helps you to answer that question.”

The study suggests not only that OUD and sepsis are linked, Dr. Martin added, but that health care providers need to be prepared to potentially see further increases in the number of patients with OUD seen in the intensive care unit.

“Both of those are things that we certainly need to be aware of, both from the individual practitioner perspective and also the public health planning perspective,” he said.

The retrospective study by Dr. Alrawashdeh and coinvestigators focused on electronic health record data for adults admitted to 373 hospitals in the United States between 2009 and 2015, including 375,479 who had sepsis.

Over time, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of OUD among those hospitalized for sepsis, from less than 2.0% in 2009 to more than 3% in 2015, representing a significant 77.3% increase. In general, the prevalence of sepsis was significantly higher among hospitalized patients with OUD compared with patients without the disorder, at 7.2% and 5.6%, respectively.

The sepsis patients with OUD tended to be younger, healthier, and more likely to be white compared with patients without OUD, according to the report. Moreover, the sepsis patients with OUD more often had endocarditis and gram-positive and fungal bloodstream infections. They also required more mechanical ventilation and had more ICU admissions, with longer stays in both the ICU and hospital.

The OUD patients accounted for 2.1% of sepsis-associated deaths overall, but 3.3% of those deaths in healthy patients, and 7.1% of deaths among younger patients, according to the report.

Those findings provide some clues that could help guide clinical practice, according to Dr. Martin. For example, the data show a nearly fivefold increased risk of endocarditis with OUD (3.9% versus 0.7%), which may inform screening practices.

“While we don’t necessarily screen every sepsis patient for endocarditis, if it’s an opioid use disorder patient – particularly one with a bloodstream infection – then that’s almost certainly something you should be doing,” Dr. Martin said.

The data suggest gram-positive bacterial and fungal infections will more likely be encountered among these patients, which could guide empiric treatment, he said.

Providers specializing in OUD should have a heightened awareness of the potential for infection and sepsis among those patients, and perhaps be more attuned to fever and other signs of infection that might warrant a referral or additional care, Dr. Martin added.

Dr. Alrawashdeh reported no disclosures related to the study.

SOURCE: Alrawashdeh M et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan;48(1):28. Abstract 56.

REPORTING FROM CCC49

Dr. Eric Howell selected as next CEO of SHM

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that Eric Howell, MD, MHM, will become its next CEO effective July 1, 2020. Dr. Howell will replace Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, who helped to found the society, and has been its first and only CEO since 2000.

“On behalf of the SHM board of directors, we welcome Dr. Howell as the incoming CEO for our organization who, with the mission-driven commitment and dedication of SHM staff, will take SHM into the future,” said Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, president-elect of SHM and chair of the CEO search committee. “With his broad knowledge of hospital medicine and extensive volunteer leadership at SHM, Dr. Howell’s experience is a natural complement to SHM’s core mission.”

Dr. Howell has a long history with SHM and has a wealth of expertise in hospital medicine. Since July 2018, he has served as chief operating officer of SHM, leading senior management’s planning and defining organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. Dr. Howell has also served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, the society’s arm that conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams, since 2015. He is a past president of SHM’s board of directors and currently serves as the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies.

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am truly honored to become SHM’s CEO,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In addition to serving in various capacities at SHM, Dr. Howell has been a professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He has held multiple titles within the Johns Hopkins medical institutions, including chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, section chief of hospital medicine for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, deputy director of hospital operations for the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and chief medical officer of operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and oversaw nearly 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

Dr. Howell received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which has proven instrumental in his mastery of managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

The search process was led by a CEO search committee, comprised of members of the SHM board of directors and assisted by the executive search firm Spencer Stuart. Launching a nationwide search, the firm identified candidates with the values and leadership qualities necessary to ensure the future growth of the organization.

“After a thorough search process, Dr. Eric Howell emerged as the right person to lead SHM,” said SHM board president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, “His experience in hospital medicine and his servant leadership style make him an ideal fit to lead SHM to even greater future success.”

In the coming weeks, the SHM board of directors will work with Dr. Howell and Dr. Wellikson on a smooth transition plan to have Dr. Howell assume the role on July 1, 2020.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that Eric Howell, MD, MHM, will become its next CEO effective July 1, 2020. Dr. Howell will replace Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, who helped to found the society, and has been its first and only CEO since 2000.

“On behalf of the SHM board of directors, we welcome Dr. Howell as the incoming CEO for our organization who, with the mission-driven commitment and dedication of SHM staff, will take SHM into the future,” said Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, president-elect of SHM and chair of the CEO search committee. “With his broad knowledge of hospital medicine and extensive volunteer leadership at SHM, Dr. Howell’s experience is a natural complement to SHM’s core mission.”

Dr. Howell has a long history with SHM and has a wealth of expertise in hospital medicine. Since July 2018, he has served as chief operating officer of SHM, leading senior management’s planning and defining organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. Dr. Howell has also served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, the society’s arm that conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams, since 2015. He is a past president of SHM’s board of directors and currently serves as the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies.

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am truly honored to become SHM’s CEO,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In addition to serving in various capacities at SHM, Dr. Howell has been a professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He has held multiple titles within the Johns Hopkins medical institutions, including chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, section chief of hospital medicine for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, deputy director of hospital operations for the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and chief medical officer of operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and oversaw nearly 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

Dr. Howell received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which has proven instrumental in his mastery of managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

The search process was led by a CEO search committee, comprised of members of the SHM board of directors and assisted by the executive search firm Spencer Stuart. Launching a nationwide search, the firm identified candidates with the values and leadership qualities necessary to ensure the future growth of the organization.

“After a thorough search process, Dr. Eric Howell emerged as the right person to lead SHM,” said SHM board president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, “His experience in hospital medicine and his servant leadership style make him an ideal fit to lead SHM to even greater future success.”

In the coming weeks, the SHM board of directors will work with Dr. Howell and Dr. Wellikson on a smooth transition plan to have Dr. Howell assume the role on July 1, 2020.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that Eric Howell, MD, MHM, will become its next CEO effective July 1, 2020. Dr. Howell will replace Laurence Wellikson, MD, MHM, who helped to found the society, and has been its first and only CEO since 2000.

“On behalf of the SHM board of directors, we welcome Dr. Howell as the incoming CEO for our organization who, with the mission-driven commitment and dedication of SHM staff, will take SHM into the future,” said Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSRC, SFHM, president-elect of SHM and chair of the CEO search committee. “With his broad knowledge of hospital medicine and extensive volunteer leadership at SHM, Dr. Howell’s experience is a natural complement to SHM’s core mission.”

Dr. Howell has a long history with SHM and has a wealth of expertise in hospital medicine. Since July 2018, he has served as chief operating officer of SHM, leading senior management’s planning and defining organizational goals to drive extensive, sustainable growth. Dr. Howell has also served as the senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, the society’s arm that conducts quality improvement programs for hospitalist teams, since 2015. He is a past president of SHM’s board of directors and currently serves as the course director for the SHM Leadership Academies.

“Having been involved with SHM in many capacities since first joining, I am truly honored to become SHM’s CEO,” Dr. Howell said. “I always tell everyone that my goal is to make the world a better place, and I know that SHM’s staff will be able to do just that through the development and deployment of a variety of products, tools, and services to help hospitalists improve patient care.”

In addition to serving in various capacities at SHM, Dr. Howell has been a professor of medicine in the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He has held multiple titles within the Johns Hopkins medical institutions, including chief of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, section chief of hospital medicine for Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, deputy director of hospital operations for the department of medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview, and chief medical officer of operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview. Dr. Howell joined the Johns Hopkins Bayview hospitalist program in 2000, began the Howard County (Md.) General Hospital hospitalist program in 2010, and oversaw nearly 200 physicians and clinical staff providing patient care in three hospitals.

Dr. Howell received his electrical engineering degree from the University of Maryland, which has proven instrumental in his mastery of managing and implementing change in the hospital. His research has focused on the relationship between the emergency department and medicine floors, improving communication, throughput, and patient outcomes.

The search process was led by a CEO search committee, comprised of members of the SHM board of directors and assisted by the executive search firm Spencer Stuart. Launching a nationwide search, the firm identified candidates with the values and leadership qualities necessary to ensure the future growth of the organization.

“After a thorough search process, Dr. Eric Howell emerged as the right person to lead SHM,” said SHM board president Christopher Frost, MD, SFHM, “His experience in hospital medicine and his servant leadership style make him an ideal fit to lead SHM to even greater future success.”

In the coming weeks, the SHM board of directors will work with Dr. Howell and Dr. Wellikson on a smooth transition plan to have Dr. Howell assume the role on July 1, 2020.

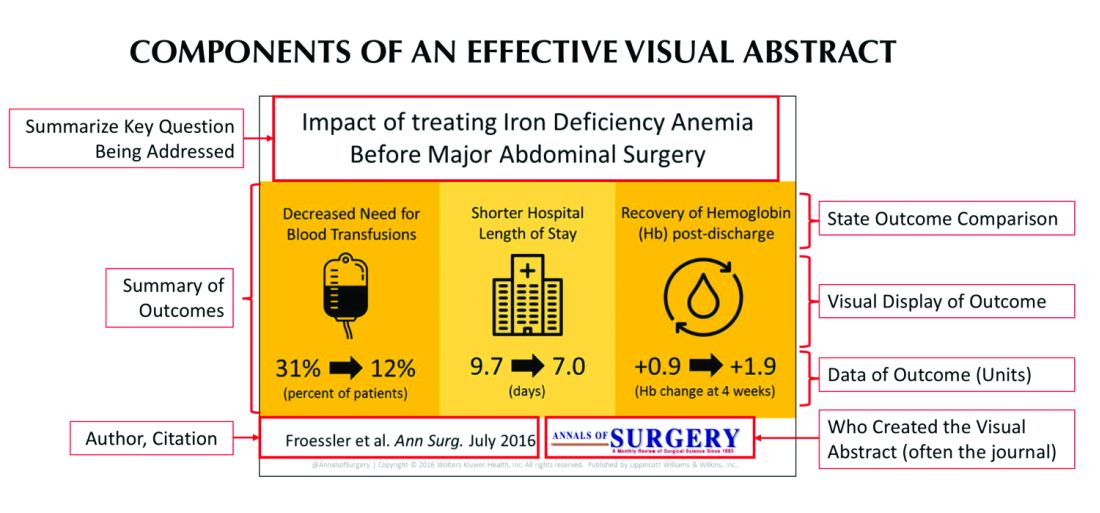

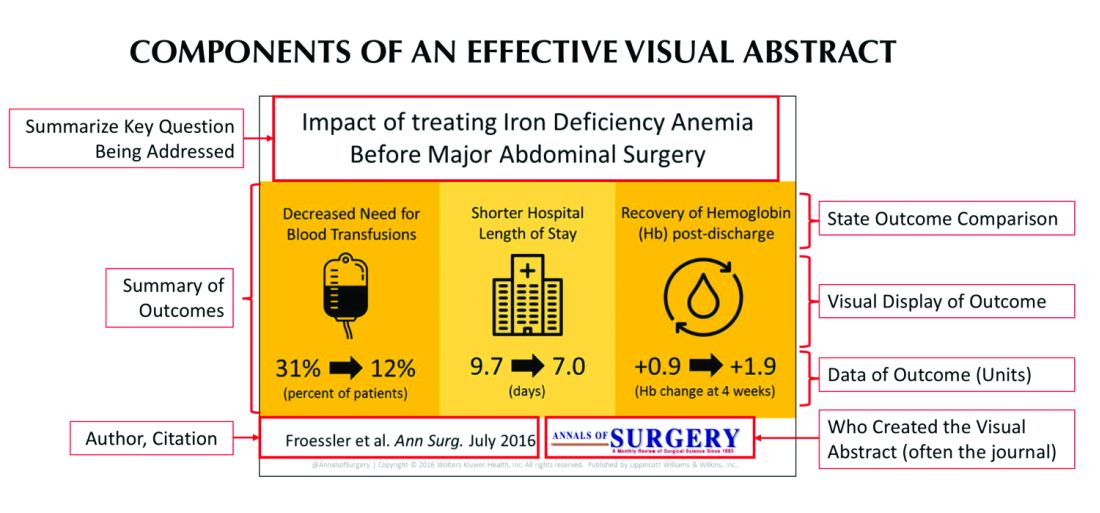

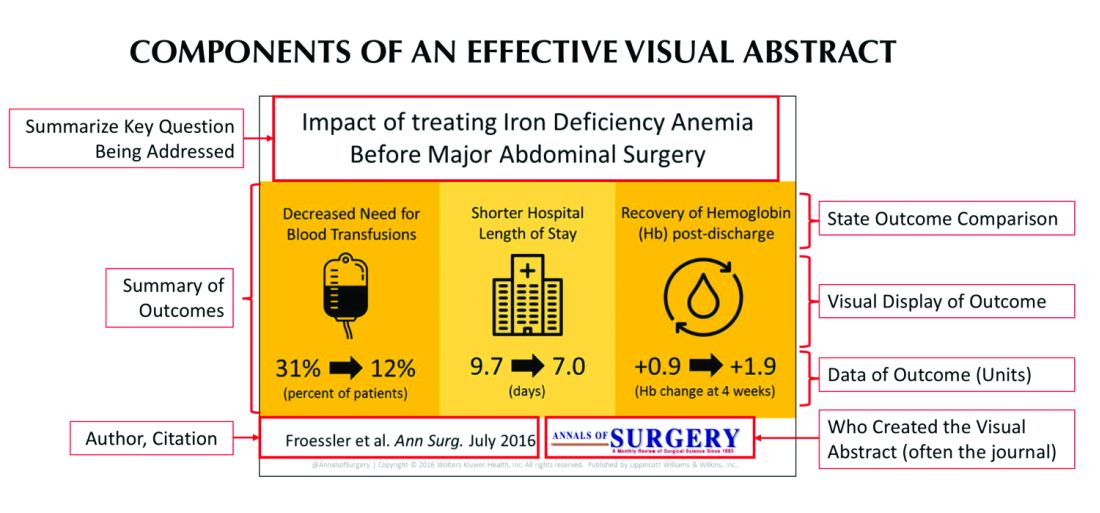

The evolution of social media and visual abstracts in hospital medicine

In recent years, social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have become popular gathering spots for clinicians to connect, engage, and share medical content. Medical journals, which often act as purveyors of this content, have recognized social media’s growing power and influence and have begun looking for ways to better engage their audiences.

In 2016, the Annals of Surgery was looking to better disseminate the work being published in its pages and looked to Twitter as one way of accomplishing this. At the time, most journals were only posting the title or a brief description of the published manuscript and hoping their Twitter followers would click on the article link. As journal editors were finding, if the audience was not immediately familiar with the topic or able to quickly capture the nuances of the study, there was a good chance the reader would continue to scroll past the post and never view the article.

Recognizing that social media heavily relies on visual material to garner attention, Annals turned to Andrew Ibrahim, MD, an architect turned surgeon, to help them rethink their social media strategy. Using the design training he had previously received in his career as an architect, Dr. Ibrahim created a simple visual tool that could be used to capture the often complicated and nuanced aspects of a research study. He called his creation a “visual abstract.”

But what is a visual abstract? Simply, they are visual representations of the key findings of a published manuscript; or put another way, a “movie trailer” to the full manuscript. While they can take many different forms and designs, they often consist of three key components: (1) a simple, easy to understand title, (2) a primary focus on outcomes, and (3) the use of visual cues or images to help the reader absorb and remember the take home message. This simplified delivery of complex information allows the producer to efficiently share complex findings in a format that allows for rapid visualization and interpretation.

Since its inception, several studies have examined the influence visual abstracts have on disseminating research. One study conducted by Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues found that articles tweeted with a visual abstract had an almost eightfold increase in the number of Twitter impressions (a measure of social media dissemination) and a threefold increase in article visits, compared with those manuscripts tweeted with the article title only.1 These results reflect what behavioral scientists have long understood: Humans process visual data better than any other type of data.2 For instance, according to research compiled by 3M, the company behind popular sticky notes, visual data is processed 60,000 times faster than text and has been shown to improve learning by 400%.3 Likewise, digital marketers have found that pages with videos and images draw on average 94% more views than their text-only counterparts.4

This knowledge, along with the substantial difference in engagement and dissemination characteristics from Dr. Ibrahim’s study, was far beyond what anyone might have expected and started a trend in medicine that continues to grow today. Medical journals across all practices and disciplines, including several leading journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), are utilizing this new tool to help disseminate their work in social media.

Visual abstracts have expanded beyond the social media sphere and are now frequently used in Grand Rounds presentations and as teaching tools among medical educators. JHM was one of the first journals to adopt the use of visual abstracts and has since published more than 150 in total. Given the growing popularity and expanded use of visual abstracts, JHM recently began archiving them on the journal’s website to allow clinicians to use the material in their own creative ways.

Visual abstracts are just one piece of the growing enterprise in social media for JHM. Recognizing the growing utilization of social media among physicians, JHM has taken a leading role in the use of online journal clubs. Since 2014, JHM has run a monthly Twitter-based journal club that discusses recently published articles and hospital medicine–based topics, called #JHMChat.5 This forum has allowed hospitalists from across the country, and around the world, to connect, network, and engage around topics important to the field of hospital medicine. The journal frequently reaches beyond hospital medicine borders and partners with other specialties and interest groups to gain perspective and insights into shared topic areas. To date, #JHMChat has one of the most robust online communities and continues to attract new followers each month.

As social media use continues to expand among clinicians, engagement tools like visual abstracts and Twitter chats will certainly continue to grow. Given that more clinicians are scrolling through websites than flipping through journal pages, medical journals like JHM will continually look for novel ways to engage their audiences and create communities among their followers. While a former architect who now practices as a surgeon led the way with visual abstracts, it remains to be seen who will create the next tool used to capture our attention on the ever-evolving sphere of social media.

Dr. Wray is a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He also serves as a digital media and associate editor for the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

References

1. Ibrahim AM et al. Visual abstracts to disseminate research on social media: A prospective, case-control crossover study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):e46.

2. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Second edition. Cheshire, Conn. Graphics Press, 2001. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999913808702121.

3. Polishing Your Presentation. http://web.archive.org/web/20001014041642/http://www.3m.com:80/meetingnetwork/files/meetingguide_pres.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2017.

4. 7 reasons you need visual content in your marketing strategy. https://medium.com/@nikos_iliopoulos/7-reasons-you-need-visual-content-in-your-marketing-strategy-bc77ca5521ac. Accessed May 28, 2017.

5. Wray CM et al. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2987.

In recent years, social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have become popular gathering spots for clinicians to connect, engage, and share medical content. Medical journals, which often act as purveyors of this content, have recognized social media’s growing power and influence and have begun looking for ways to better engage their audiences.

In 2016, the Annals of Surgery was looking to better disseminate the work being published in its pages and looked to Twitter as one way of accomplishing this. At the time, most journals were only posting the title or a brief description of the published manuscript and hoping their Twitter followers would click on the article link. As journal editors were finding, if the audience was not immediately familiar with the topic or able to quickly capture the nuances of the study, there was a good chance the reader would continue to scroll past the post and never view the article.

Recognizing that social media heavily relies on visual material to garner attention, Annals turned to Andrew Ibrahim, MD, an architect turned surgeon, to help them rethink their social media strategy. Using the design training he had previously received in his career as an architect, Dr. Ibrahim created a simple visual tool that could be used to capture the often complicated and nuanced aspects of a research study. He called his creation a “visual abstract.”

But what is a visual abstract? Simply, they are visual representations of the key findings of a published manuscript; or put another way, a “movie trailer” to the full manuscript. While they can take many different forms and designs, they often consist of three key components: (1) a simple, easy to understand title, (2) a primary focus on outcomes, and (3) the use of visual cues or images to help the reader absorb and remember the take home message. This simplified delivery of complex information allows the producer to efficiently share complex findings in a format that allows for rapid visualization and interpretation.

Since its inception, several studies have examined the influence visual abstracts have on disseminating research. One study conducted by Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues found that articles tweeted with a visual abstract had an almost eightfold increase in the number of Twitter impressions (a measure of social media dissemination) and a threefold increase in article visits, compared with those manuscripts tweeted with the article title only.1 These results reflect what behavioral scientists have long understood: Humans process visual data better than any other type of data.2 For instance, according to research compiled by 3M, the company behind popular sticky notes, visual data is processed 60,000 times faster than text and has been shown to improve learning by 400%.3 Likewise, digital marketers have found that pages with videos and images draw on average 94% more views than their text-only counterparts.4

This knowledge, along with the substantial difference in engagement and dissemination characteristics from Dr. Ibrahim’s study, was far beyond what anyone might have expected and started a trend in medicine that continues to grow today. Medical journals across all practices and disciplines, including several leading journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), are utilizing this new tool to help disseminate their work in social media.

Visual abstracts have expanded beyond the social media sphere and are now frequently used in Grand Rounds presentations and as teaching tools among medical educators. JHM was one of the first journals to adopt the use of visual abstracts and has since published more than 150 in total. Given the growing popularity and expanded use of visual abstracts, JHM recently began archiving them on the journal’s website to allow clinicians to use the material in their own creative ways.

Visual abstracts are just one piece of the growing enterprise in social media for JHM. Recognizing the growing utilization of social media among physicians, JHM has taken a leading role in the use of online journal clubs. Since 2014, JHM has run a monthly Twitter-based journal club that discusses recently published articles and hospital medicine–based topics, called #JHMChat.5 This forum has allowed hospitalists from across the country, and around the world, to connect, network, and engage around topics important to the field of hospital medicine. The journal frequently reaches beyond hospital medicine borders and partners with other specialties and interest groups to gain perspective and insights into shared topic areas. To date, #JHMChat has one of the most robust online communities and continues to attract new followers each month.

As social media use continues to expand among clinicians, engagement tools like visual abstracts and Twitter chats will certainly continue to grow. Given that more clinicians are scrolling through websites than flipping through journal pages, medical journals like JHM will continually look for novel ways to engage their audiences and create communities among their followers. While a former architect who now practices as a surgeon led the way with visual abstracts, it remains to be seen who will create the next tool used to capture our attention on the ever-evolving sphere of social media.

Dr. Wray is a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He also serves as a digital media and associate editor for the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

References

1. Ibrahim AM et al. Visual abstracts to disseminate research on social media: A prospective, case-control crossover study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):e46.

2. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Second edition. Cheshire, Conn. Graphics Press, 2001. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999913808702121.

3. Polishing Your Presentation. http://web.archive.org/web/20001014041642/http://www.3m.com:80/meetingnetwork/files/meetingguide_pres.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2017.

4. 7 reasons you need visual content in your marketing strategy. https://medium.com/@nikos_iliopoulos/7-reasons-you-need-visual-content-in-your-marketing-strategy-bc77ca5521ac. Accessed May 28, 2017.

5. Wray CM et al. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2987.

In recent years, social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have become popular gathering spots for clinicians to connect, engage, and share medical content. Medical journals, which often act as purveyors of this content, have recognized social media’s growing power and influence and have begun looking for ways to better engage their audiences.

In 2016, the Annals of Surgery was looking to better disseminate the work being published in its pages and looked to Twitter as one way of accomplishing this. At the time, most journals were only posting the title or a brief description of the published manuscript and hoping their Twitter followers would click on the article link. As journal editors were finding, if the audience was not immediately familiar with the topic or able to quickly capture the nuances of the study, there was a good chance the reader would continue to scroll past the post and never view the article.

Recognizing that social media heavily relies on visual material to garner attention, Annals turned to Andrew Ibrahim, MD, an architect turned surgeon, to help them rethink their social media strategy. Using the design training he had previously received in his career as an architect, Dr. Ibrahim created a simple visual tool that could be used to capture the often complicated and nuanced aspects of a research study. He called his creation a “visual abstract.”

But what is a visual abstract? Simply, they are visual representations of the key findings of a published manuscript; or put another way, a “movie trailer” to the full manuscript. While they can take many different forms and designs, they often consist of three key components: (1) a simple, easy to understand title, (2) a primary focus on outcomes, and (3) the use of visual cues or images to help the reader absorb and remember the take home message. This simplified delivery of complex information allows the producer to efficiently share complex findings in a format that allows for rapid visualization and interpretation.

Since its inception, several studies have examined the influence visual abstracts have on disseminating research. One study conducted by Dr. Ibrahim and his colleagues found that articles tweeted with a visual abstract had an almost eightfold increase in the number of Twitter impressions (a measure of social media dissemination) and a threefold increase in article visits, compared with those manuscripts tweeted with the article title only.1 These results reflect what behavioral scientists have long understood: Humans process visual data better than any other type of data.2 For instance, according to research compiled by 3M, the company behind popular sticky notes, visual data is processed 60,000 times faster than text and has been shown to improve learning by 400%.3 Likewise, digital marketers have found that pages with videos and images draw on average 94% more views than their text-only counterparts.4

This knowledge, along with the substantial difference in engagement and dissemination characteristics from Dr. Ibrahim’s study, was far beyond what anyone might have expected and started a trend in medicine that continues to grow today. Medical journals across all practices and disciplines, including several leading journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), are utilizing this new tool to help disseminate their work in social media.

Visual abstracts have expanded beyond the social media sphere and are now frequently used in Grand Rounds presentations and as teaching tools among medical educators. JHM was one of the first journals to adopt the use of visual abstracts and has since published more than 150 in total. Given the growing popularity and expanded use of visual abstracts, JHM recently began archiving them on the journal’s website to allow clinicians to use the material in their own creative ways.

Visual abstracts are just one piece of the growing enterprise in social media for JHM. Recognizing the growing utilization of social media among physicians, JHM has taken a leading role in the use of online journal clubs. Since 2014, JHM has run a monthly Twitter-based journal club that discusses recently published articles and hospital medicine–based topics, called #JHMChat.5 This forum has allowed hospitalists from across the country, and around the world, to connect, network, and engage around topics important to the field of hospital medicine. The journal frequently reaches beyond hospital medicine borders and partners with other specialties and interest groups to gain perspective and insights into shared topic areas. To date, #JHMChat has one of the most robust online communities and continues to attract new followers each month.

As social media use continues to expand among clinicians, engagement tools like visual abstracts and Twitter chats will certainly continue to grow. Given that more clinicians are scrolling through websites than flipping through journal pages, medical journals like JHM will continually look for novel ways to engage their audiences and create communities among their followers. While a former architect who now practices as a surgeon led the way with visual abstracts, it remains to be seen who will create the next tool used to capture our attention on the ever-evolving sphere of social media.

Dr. Wray is a hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He also serves as a digital media and associate editor for the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

References

1. Ibrahim AM et al. Visual abstracts to disseminate research on social media: A prospective, case-control crossover study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):e46.

2. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Second edition. Cheshire, Conn. Graphics Press, 2001. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999913808702121.

3. Polishing Your Presentation. http://web.archive.org/web/20001014041642/http://www.3m.com:80/meetingnetwork/files/meetingguide_pres.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2017.

4. 7 reasons you need visual content in your marketing strategy. https://medium.com/@nikos_iliopoulos/7-reasons-you-need-visual-content-in-your-marketing-strategy-bc77ca5521ac. Accessed May 28, 2017.

5. Wray CM et al. The adoption of an online journal club to improve research dissemination and social media engagement among hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2987.

When is a troponin elevation an acute myocardial infarction?

Misdiagnosis can have ‘downstream repercussions’

Hospitalists encounter troponin elevations daily, but we have to use clinical judgment to determine if the troponin elevation represents either a myocardial infarction (MI), or a non-MI troponin elevation (i.e. a , nonischemic myocardial injury).

It is important to remember that an MI specifically refers to myocardial injury due to acute myocardial ischemia to the myocardium. This lack of blood supply can be due to an acute absolute or relative deficiency in coronary artery blood flow. However, there are also many mechanisms of myocardial injury unrelated to reduced coronary artery blood flow, and these should be more appropriately termed non-MI troponin elevations.

Historically, when an ischemic mechanism of myocardial injury was suspected, providers would categorize troponin elevations into ST-elevation MI (STEMI) versus non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) based on the electrocardiogram (ECG). We would further classify the NSTEMI into type 1 or type 2, depending on the mechanism of injury. The term “NSTEMI” served as a “catch-all” term to describe both type 1 NSTEMIs and type 2 MIs, but that classification system is no longer valid.

As of Oct. 1, 2017, ICD-10 and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have a new ICD-10 diagnosis code for type 2 MI (I21.A1), distinct from NSTEMI (I21.4) based on updated definitions from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, and World Heart Federation. The term “NSTEMI” should be used only when referring to a type 1 MI not when referring to a type 2 MI.1

Classification of MI types

The Fourth Universal Definition of MI published in August 2018 further updated the definitions of MI (summarized in Figure 1).2 This review focuses on type 1 and type 2 MIs, which are the most common types encountered by hospitalists. Types 3-5 MI (grouped under a common ICD-10 diagnosis code for “Other MI Types,” or I21.A9) would rarely be diagnosed by hospitalists.

Figure 1: Classification of MI

MI Type | Classification |

1 | STEMI (acute coronary artery thrombosis) |

2 | Supply/demand mismatch (heterogeneous underlying causes) |

3 | Sudden cardiac death with ECG evidence of acute myocardial ischemia before cardiac troponins could be drawn |

4 | MI due to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) |

5 | MI due to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) |

The diagnosis of a type 1 MIs (STEMI and NSTEMI) is supported by the presence of an acute coronary thrombus or plaque rupture/erosion on coronary angiography or a strong suspicion for these when angiography is unavailable or contraindicated. Type 1 MI (also referred to as spontaneous MI) is generally a primary reason (or “principal” diagnosis) for a patient’s presentation to a hospital.3 Please note that a very high or rising troponin level alone is not diagnostic for a type 1 or type 2 NSTEMI. The lab has to be taken in the context of the patient’s presentation and other supporting findings.

In contrast to a type 1 MI (STEMI and NSTEMI), at type 2 MI results from an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand unrelated to acute coronary artery thrombosis or plaque rupture. A type 2 MI is a relative (as opposed to an absolute) deficiency in coronary artery blood flow triggered by an abrupt increase in myocardial oxygen demand, drop in myocardial blood supply, or both. In type 2 MI, myocardial injury occurs secondary to an underlying process, and therefore requires correct documentation of the underlying cause as well.

Common examples of underlying causes of type 2 MI include acute blood loss anemia (e.g. GI bleed), acute hypoxia (e.g. COPD exacerbation), shock states (cardiogenic, hypovolemic, hemorrhagic, or septic), coronary vasospasm (e.g. spontaneous), and bradyarrhythmias. Patients with type 2 MI often have a history of fixed obstructive coronary disease, which when coupled with the acute trigger facilitates the type 2 MI; however, underlying CAD is not always present.

Diagnosing a type 2 MI requires evidence of acute myocardial ischemia (Figure 2) with an elevated troponin but must also have at least one of the following:2

- Symptoms of acute myocardial ischemia such as typical chest pain.

- New ischemic ECG changes.

- Development of pathological Q waves.

- Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium, significant reversible perfusion defect on nuclear imaging, or new regional wall motion abnormality in a pattern consistent with an ischemic etiology.

Distinguishing a type 1 NSTEMI from a type 2 MI depends mainly on the clinical context and clinical judgment. A patient whose presenting symptoms include acute chest discomfort, acute ST-T wave changes, and a rise in troponin would be suspected of having a type 1 NSTEMI. However, in a patient presenting with other or vague complaints where an elevated troponin was found amongst a battery of tests, a type 2 MI may be favored, particularly if there is evidence of an underlying trigger for a supply-demand mismatch. In challenging cases, cardiology consultation can help determine the MI type and/or the next diagnostic and treatment considerations.

When there is only elevated troponin levels (or even a rise and fall in troponin) without new symptoms or ECG/imaging evidence of myocardial ischemia, it is most appropriate to document a non-MI troponin elevation due to a nonischemic mechanism of myocardial injury.

Non-MI troponin elevation (nonischemic myocardial injury)

The number of conditions known to cause myocardial injury through mechanisms other than myocardial ischemia (see Figure 2) is growing, especially in the current era of high-sensitivity troponin assays.4

Common examples of underlying causes of non-MI troponin elevation include:

- Acute (on chronic) systolic or diastolic heart failure: Usually due to acute ventricular wall stretch/strain. Troponin elevations tend to be mild, with more indolent (or even flat) troponin trajectories.

- Pericarditis and myocarditis: Due to direct injury from myocardial inflammation.

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): Due to physical injury to the heart from mechanical chest compressions and from electrical shocks of external defibrillation.

- Stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy: Stress-induced release of neurohormonal factors and catecholamines that cause direct myocyte injury and transient dilatation of the ventricle.

- Acute pulmonary embolism: Result of acute right ventricular wall stretch/strain, not from myocardial ischemia.

- Sepsis without shock: Direct toxicity of circulating cytokines to cardiac myocytes. In the absence of evidence of shock and symptoms/signs of myocardial ischemia, do not document type 2 MI.

- Renal failure (acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease): Multiple etiologies, but at least partially related to reduced renal clearance of troponin. In general, renal failure in the absence of symptoms/signs of ischemia is best classified as a non-MI troponin elevation. ESRD patients who present with volume overload due to missed dialysis also typically have a non-MI troponin elevation.

- Stroke/intracranial hemorrhage: Mechanisms of myocardial injury and troponin elevation are incompletely understood, but may include catecholamine surges that injure the heart.

Some underlying conditions can cause a type 2 MI or a non-MI troponin elevation depending on the clinical context. For example, hypertensive emergency, severe aortic valve stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and tachyarrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) may cause increased myocardial oxygen demand, and in patients with underlying CAD, could precipitate a type 2 MI.

However, these same conditions could cause a non-MI troponin elevation in patients without CAD and could also cause myocardial injury and troponin release by causing acute left ventricular stretch/strain. Distinguishing the diagnose of type 2 MI vs. non-MI troponin elevation depends on documenting whether there are ancillary ischemic symptoms, ECG findings, imaging, and/or cath findings of acute myocardial ischemia.

Case examples