User login

Medicare study evaluates impact of U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

Research offers evidence against calls to curtail the program

Among Medicare beneficiaries admitted to the hospital between 2008 and 2016, there was an increase in postdischarge 30-day mortality for patients with heart failure, but not for those with acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia.

The finding comes from an effort to evaluate the use of services soon after discharge for conditions targeted in the U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), and patients’ outcomes.

“The announcement and implementation of the HRRP were associated with a reduction in readmissions within 30 days of discharge for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia, as shown by a decrease in the overall national rate of readmissions,” first author Rohan Khera, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online Jan. 15, 2020, in the British Medical Journal (doi:10.1136/bmj.l6831).

“Concerns existed that pressures to reduce readmissions had led to the evolution of care patterns that may have adverse consequences through reducing access to care in appropriate settings. Therefore, determining whether patients who are seen in acute care settings, but not admitted to hospital, experience an increased risk of mortality is essential.”

Dr. Khera, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues limited the analysis to Medicare claims data from patients who were admitted to the hospital with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (MI), or pneumonia between 2008 and 2016. Key outcomes of interest were: (1) postdischarge 30-day mortality; and (2) acute care utilization in inpatient units, observation units, and the ED during the postdischarge period.

During the study period there were 3,772,924 hospital admissions for heart failure, 1,570,113 for acute MI, and 3,131,162 for pneumonia. The greatest number of readmissions within 30 days of discharge was for heart failure patients (22.5%), followed by acute MI (17.5%), and pneumonia (17.2%).

The overall rates of observation stays were 1.7% for heart failure, 2.6% for acute MI, and 1.4% for pneumonia, while the overall rates of emergency department visits were 6.4% for heart failure, 6.8% for acute MI, and 6.3% for pneumonia. Cumulatively, about one-third of all admissions – 30.7% for heart failure, 26.9% for acute MI, and 24.8% for pneumonia – received postdischarge care in any acute care setting.

Dr. Khera and colleagues found that overall postdischarge 30-day mortality was 8.7% for heart failure, 7.3% for acute MI, and 8.4% for pneumonia. At the same time, postdischarge 30-day mortality was higher in patients with readmissions (13.2% for heart failure, 12.7% for acute MI, and 15.3% for pneumonia), compared with those who had observation stays (4.5% for heart failure, 2.7% for acute MI, and 4.6% for pneumonia), emergency department visits (9.7% for heart failure, 8.8% for acute MI, and 7.8% for pneumonia), or no postdischarge acute care (7.2% for heart failure, 6.0% for acute MI, and 6.9% for pneumonia). Risk adjusted mortality increased annually by 0.05% only for heart failure, while it decreased by 0.06% for acute MI, and did not significantly change for pneumonia.

“The study strongly suggests that the HRRP did not lead to harm through inappropriate triage of patients at high risk to observation units and the emergency department, and therefore provides evidence against calls to curtail the program owing to this theoretical concern (see JAMA 2018;320:2539-41),” the researchers concluded.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they were “unable to identify patterns of acute care during the index hospital admission that would be associated with a higher rate of postdischarge acute care in observation units and emergency departments and whether these visits represented avenues for planned postdischarge follow-up care. Moreover, the proportion of these care encounters that were preventable remains poorly understood.”

Dr. Khera disclosed that he is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. His coauthors reported having numerous disclosures.

SOURCE: Khera et al. BMJ 2020;368:l6831.

Research offers evidence against calls to curtail the program

Research offers evidence against calls to curtail the program

Among Medicare beneficiaries admitted to the hospital between 2008 and 2016, there was an increase in postdischarge 30-day mortality for patients with heart failure, but not for those with acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia.

The finding comes from an effort to evaluate the use of services soon after discharge for conditions targeted in the U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), and patients’ outcomes.

“The announcement and implementation of the HRRP were associated with a reduction in readmissions within 30 days of discharge for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia, as shown by a decrease in the overall national rate of readmissions,” first author Rohan Khera, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online Jan. 15, 2020, in the British Medical Journal (doi:10.1136/bmj.l6831).

“Concerns existed that pressures to reduce readmissions had led to the evolution of care patterns that may have adverse consequences through reducing access to care in appropriate settings. Therefore, determining whether patients who are seen in acute care settings, but not admitted to hospital, experience an increased risk of mortality is essential.”

Dr. Khera, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues limited the analysis to Medicare claims data from patients who were admitted to the hospital with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (MI), or pneumonia between 2008 and 2016. Key outcomes of interest were: (1) postdischarge 30-day mortality; and (2) acute care utilization in inpatient units, observation units, and the ED during the postdischarge period.

During the study period there were 3,772,924 hospital admissions for heart failure, 1,570,113 for acute MI, and 3,131,162 for pneumonia. The greatest number of readmissions within 30 days of discharge was for heart failure patients (22.5%), followed by acute MI (17.5%), and pneumonia (17.2%).

The overall rates of observation stays were 1.7% for heart failure, 2.6% for acute MI, and 1.4% for pneumonia, while the overall rates of emergency department visits were 6.4% for heart failure, 6.8% for acute MI, and 6.3% for pneumonia. Cumulatively, about one-third of all admissions – 30.7% for heart failure, 26.9% for acute MI, and 24.8% for pneumonia – received postdischarge care in any acute care setting.

Dr. Khera and colleagues found that overall postdischarge 30-day mortality was 8.7% for heart failure, 7.3% for acute MI, and 8.4% for pneumonia. At the same time, postdischarge 30-day mortality was higher in patients with readmissions (13.2% for heart failure, 12.7% for acute MI, and 15.3% for pneumonia), compared with those who had observation stays (4.5% for heart failure, 2.7% for acute MI, and 4.6% for pneumonia), emergency department visits (9.7% for heart failure, 8.8% for acute MI, and 7.8% for pneumonia), or no postdischarge acute care (7.2% for heart failure, 6.0% for acute MI, and 6.9% for pneumonia). Risk adjusted mortality increased annually by 0.05% only for heart failure, while it decreased by 0.06% for acute MI, and did not significantly change for pneumonia.

“The study strongly suggests that the HRRP did not lead to harm through inappropriate triage of patients at high risk to observation units and the emergency department, and therefore provides evidence against calls to curtail the program owing to this theoretical concern (see JAMA 2018;320:2539-41),” the researchers concluded.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they were “unable to identify patterns of acute care during the index hospital admission that would be associated with a higher rate of postdischarge acute care in observation units and emergency departments and whether these visits represented avenues for planned postdischarge follow-up care. Moreover, the proportion of these care encounters that were preventable remains poorly understood.”

Dr. Khera disclosed that he is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. His coauthors reported having numerous disclosures.

SOURCE: Khera et al. BMJ 2020;368:l6831.

Among Medicare beneficiaries admitted to the hospital between 2008 and 2016, there was an increase in postdischarge 30-day mortality for patients with heart failure, but not for those with acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia.

The finding comes from an effort to evaluate the use of services soon after discharge for conditions targeted in the U.S. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), and patients’ outcomes.

“The announcement and implementation of the HRRP were associated with a reduction in readmissions within 30 days of discharge for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia, as shown by a decrease in the overall national rate of readmissions,” first author Rohan Khera, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online Jan. 15, 2020, in the British Medical Journal (doi:10.1136/bmj.l6831).

“Concerns existed that pressures to reduce readmissions had led to the evolution of care patterns that may have adverse consequences through reducing access to care in appropriate settings. Therefore, determining whether patients who are seen in acute care settings, but not admitted to hospital, experience an increased risk of mortality is essential.”

Dr. Khera, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues limited the analysis to Medicare claims data from patients who were admitted to the hospital with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (MI), or pneumonia between 2008 and 2016. Key outcomes of interest were: (1) postdischarge 30-day mortality; and (2) acute care utilization in inpatient units, observation units, and the ED during the postdischarge period.

During the study period there were 3,772,924 hospital admissions for heart failure, 1,570,113 for acute MI, and 3,131,162 for pneumonia. The greatest number of readmissions within 30 days of discharge was for heart failure patients (22.5%), followed by acute MI (17.5%), and pneumonia (17.2%).

The overall rates of observation stays were 1.7% for heart failure, 2.6% for acute MI, and 1.4% for pneumonia, while the overall rates of emergency department visits were 6.4% for heart failure, 6.8% for acute MI, and 6.3% for pneumonia. Cumulatively, about one-third of all admissions – 30.7% for heart failure, 26.9% for acute MI, and 24.8% for pneumonia – received postdischarge care in any acute care setting.

Dr. Khera and colleagues found that overall postdischarge 30-day mortality was 8.7% for heart failure, 7.3% for acute MI, and 8.4% for pneumonia. At the same time, postdischarge 30-day mortality was higher in patients with readmissions (13.2% for heart failure, 12.7% for acute MI, and 15.3% for pneumonia), compared with those who had observation stays (4.5% for heart failure, 2.7% for acute MI, and 4.6% for pneumonia), emergency department visits (9.7% for heart failure, 8.8% for acute MI, and 7.8% for pneumonia), or no postdischarge acute care (7.2% for heart failure, 6.0% for acute MI, and 6.9% for pneumonia). Risk adjusted mortality increased annually by 0.05% only for heart failure, while it decreased by 0.06% for acute MI, and did not significantly change for pneumonia.

“The study strongly suggests that the HRRP did not lead to harm through inappropriate triage of patients at high risk to observation units and the emergency department, and therefore provides evidence against calls to curtail the program owing to this theoretical concern (see JAMA 2018;320:2539-41),” the researchers concluded.

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that they were “unable to identify patterns of acute care during the index hospital admission that would be associated with a higher rate of postdischarge acute care in observation units and emergency departments and whether these visits represented avenues for planned postdischarge follow-up care. Moreover, the proportion of these care encounters that were preventable remains poorly understood.”

Dr. Khera disclosed that he is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. His coauthors reported having numerous disclosures.

SOURCE: Khera et al. BMJ 2020;368:l6831.

FROM BMJ

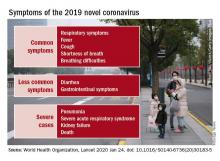

CDC begins coronavirus diagnostic test kit distribution; new case confirmed in Wisconsin

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services confirmed a new case of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on Feb. 5, 2020, bringing the total number of cases in the United States to 12.*

Earlier in the day, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters that 206 individuals under investigation had tested negative for infection with the novel virus and that tests were pending on another 76 individuals.

The agency also announced during a press briefing call that diagnostic test kits will begin shipping on Feb. 5, less than 24 hours after receiving an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration. Full information is available in an article published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The emergency use authorization will allow for broader use of the CDC’s 2019-nCoV Real Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, which to date has been limited for use at CDC laboratories. Under the emergency use authorization, the diagnostic kit is authorized for patients who meed the CDC criteria for 2019-nCoV testing. The diagnostic test is a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test that provides presumptive detection of 2019-nCoV from respiratory secretions, such as nasal or oral swabs. A positive test indicates likely infection, although a negative test does not preclude infection and should not be the sole determination for patient management decisions.

“Today, the test kits will start shipping to over 100 U.S. public health labs,” she said. “Each of these labs is required to perform international verification for [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] compliance prior to reporting out. This process is expected to take a few days.”

Dr. Messonnier said that 200 test kits will be distributed to domestic labs and another 200 test kits will go to select international labs. Each kit can perform diagnostics on 700-800 patient samples.

“What that means is that, by the start of next week, we expect there to be much enhanced capacity for laboratory testing closer to our patients,” she said, adding that additional test kits are being produced and will be available for ordering in the future. Each laboratory that places an order will receive one test kit.

“Distribution of these tests will improve the global capacity to detect and respond to this new virus,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Availability of this test is a starting place for greater commercial availability of diagnostic testing for nCoV.”

The CDC also said that the next batch of passengers arriving from Wuhan, China, will be arriving in one of four locations: Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, Calif.; Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, San Diego; Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio; and Eppley Airfield, Omaha, Neb. Passengers will be quarantined for up to 14 days from the day the flight left Wuhan and medical care will be provided if needed.

“We do not believe these people pose a threat to the communities where they are being housed as we are taking measures to minimize any contact,” she said, adding that confirmed infections are expected among these and other returning travelers.

Dr. Messonnier warned that the quarantine measures “may not catch every single returning traveler returning with novel coronavirus, given the nature of this virus and how it is spreading. But if we can catch the majority of them, that will slow the entry of this virus into the United States.”

*This story was updated on 02/05/2020.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services confirmed a new case of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on Feb. 5, 2020, bringing the total number of cases in the United States to 12.*

Earlier in the day, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters that 206 individuals under investigation had tested negative for infection with the novel virus and that tests were pending on another 76 individuals.

The agency also announced during a press briefing call that diagnostic test kits will begin shipping on Feb. 5, less than 24 hours after receiving an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration. Full information is available in an article published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The emergency use authorization will allow for broader use of the CDC’s 2019-nCoV Real Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, which to date has been limited for use at CDC laboratories. Under the emergency use authorization, the diagnostic kit is authorized for patients who meed the CDC criteria for 2019-nCoV testing. The diagnostic test is a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test that provides presumptive detection of 2019-nCoV from respiratory secretions, such as nasal or oral swabs. A positive test indicates likely infection, although a negative test does not preclude infection and should not be the sole determination for patient management decisions.

“Today, the test kits will start shipping to over 100 U.S. public health labs,” she said. “Each of these labs is required to perform international verification for [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] compliance prior to reporting out. This process is expected to take a few days.”

Dr. Messonnier said that 200 test kits will be distributed to domestic labs and another 200 test kits will go to select international labs. Each kit can perform diagnostics on 700-800 patient samples.

“What that means is that, by the start of next week, we expect there to be much enhanced capacity for laboratory testing closer to our patients,” she said, adding that additional test kits are being produced and will be available for ordering in the future. Each laboratory that places an order will receive one test kit.

“Distribution of these tests will improve the global capacity to detect and respond to this new virus,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Availability of this test is a starting place for greater commercial availability of diagnostic testing for nCoV.”

The CDC also said that the next batch of passengers arriving from Wuhan, China, will be arriving in one of four locations: Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, Calif.; Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, San Diego; Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio; and Eppley Airfield, Omaha, Neb. Passengers will be quarantined for up to 14 days from the day the flight left Wuhan and medical care will be provided if needed.

“We do not believe these people pose a threat to the communities where they are being housed as we are taking measures to minimize any contact,” she said, adding that confirmed infections are expected among these and other returning travelers.

Dr. Messonnier warned that the quarantine measures “may not catch every single returning traveler returning with novel coronavirus, given the nature of this virus and how it is spreading. But if we can catch the majority of them, that will slow the entry of this virus into the United States.”

*This story was updated on 02/05/2020.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services confirmed a new case of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) on Feb. 5, 2020, bringing the total number of cases in the United States to 12.*

Earlier in the day, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters that 206 individuals under investigation had tested negative for infection with the novel virus and that tests were pending on another 76 individuals.

The agency also announced during a press briefing call that diagnostic test kits will begin shipping on Feb. 5, less than 24 hours after receiving an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration. Full information is available in an article published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The emergency use authorization will allow for broader use of the CDC’s 2019-nCoV Real Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, which to date has been limited for use at CDC laboratories. Under the emergency use authorization, the diagnostic kit is authorized for patients who meed the CDC criteria for 2019-nCoV testing. The diagnostic test is a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test that provides presumptive detection of 2019-nCoV from respiratory secretions, such as nasal or oral swabs. A positive test indicates likely infection, although a negative test does not preclude infection and should not be the sole determination for patient management decisions.

“Today, the test kits will start shipping to over 100 U.S. public health labs,” she said. “Each of these labs is required to perform international verification for [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] compliance prior to reporting out. This process is expected to take a few days.”

Dr. Messonnier said that 200 test kits will be distributed to domestic labs and another 200 test kits will go to select international labs. Each kit can perform diagnostics on 700-800 patient samples.

“What that means is that, by the start of next week, we expect there to be much enhanced capacity for laboratory testing closer to our patients,” she said, adding that additional test kits are being produced and will be available for ordering in the future. Each laboratory that places an order will receive one test kit.

“Distribution of these tests will improve the global capacity to detect and respond to this new virus,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Availability of this test is a starting place for greater commercial availability of diagnostic testing for nCoV.”

The CDC also said that the next batch of passengers arriving from Wuhan, China, will be arriving in one of four locations: Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, Calif.; Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, San Diego; Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio; and Eppley Airfield, Omaha, Neb. Passengers will be quarantined for up to 14 days from the day the flight left Wuhan and medical care will be provided if needed.

“We do not believe these people pose a threat to the communities where they are being housed as we are taking measures to minimize any contact,” she said, adding that confirmed infections are expected among these and other returning travelers.

Dr. Messonnier warned that the quarantine measures “may not catch every single returning traveler returning with novel coronavirus, given the nature of this virus and how it is spreading. But if we can catch the majority of them, that will slow the entry of this virus into the United States.”

*This story was updated on 02/05/2020.

Documentation matters

Quality over quantity

Documentation has always been part of a physician’s job. Historically, in the days of paper records, physicians saw a patient on rounds and immediately following, while still on the unit, wrote a daily note detailing the events, test results, and plans since the last note. Addenda were written over the course of the day and night as needed.

The medical record was a chronological itemization of the encounter. The chart told the patient’s story, hopefully legibly and without excessive rehashing of previous material. The discharge summary then encapsulated the hospitalization in several coherent paragraphs.

In the current electronic records environment, we are inundated with excessive and repetitious information, data without interpretation, differentials without diagnoses. Prepopulation of templated notes, defaults without edit, and dictation without revision have degraded our documentation to the point of unintelligibility. The chronological storytelling and trustworthiness of the medical record has become suspect.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is touting its “Patients over Paperwork” initiative. The solution is flawed (that is, future relaxation of documentation requirements for professional billing) because the premise is delusive. Documentation isn’t fundamentally the problem. Having clinicians jump through regulatory hoops which do not advance patients’ care, and providers misunderstanding the requirements for level-of-service billing are the essential issues. Getting no training on how to properly document in medical school/residency and receiving no formative feedback on documentation throughout one’s career compounds the problem. Having clinical documentation serve too many masters, including compliance, quality, medicolegal, utilization review, and reimbursement, is also to blame. The advent of the electronic medical record was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Many hospitals now have a clinical documentation integrity (CDI) team which is tasked with querying the provider when the health record documentation is conflicting, imprecise, incomplete, illegible, ambiguous, or inconsistent. They are charged with getting practitioners to associate clinical indicators with diagnoses and to consider removal of diagnoses which do not seem clinically valid from the existing documentation. From this explanation, you might well conclude that the CDI specialist could generate a query on every patient if they were so inclined, and you would be correct. But the goal isn’t to torture the physician – it is to ensure that the medical record is accurately depicting the encounter.

You are not being asked for more documentation by the CDI team; they are entreating you for higher-quality documentation. Let me give you some pointers to ward off queries.

- Tell the story. The most important goal of documentation is to clinically communicate to other caregivers. Think to yourself: “What would a fellow clinician need to know about this patient to understand why I drew those conclusions or to pick up where I left off?” At 2 a.m., that information, or lack thereof, could literally be a matter of life or death.

- Tell the truth. Embellishing the record or including invalid diagnoses with the intent to increase the severity of illness resulting in a more favorable diagnosis-related group – the inpatient risk-adjustment system – is considered fraud.

- You may like the convenience of copy forward, but do you relish reading other people’s copy and paste? Consider doing a documentation time-out. Before you copy and paste yesterday’s assessment and plan, stop and think: “Why is the patient still here? Why are we doing what we are doing?” If you choose to copy and paste, be certain to do mindful editing so the documentation represents the current situation and avoids redundancy. Appropriately editing copy and pasted documentation may prove more time consuming than generating a note de novo.

- Translate findings into diagnoses using your best medical judgment. One man’s hypotension may be another health care provider’s shock. Coders are not clinical and are not permitted to make inferences. A potassium of 6.7 may be hyperkalemia or it may be spurious – only a clinician may make that determination using their clinical expertise and experience. The coder is not allowed to read your mind. You must explicitly draw the conclusion that a febrile patient with bacteremia, encephalopathy, hypoxemia, and a blood pressure of 85/60 is in septic shock.

- Uncertain diagnoses (heralded by words such as: likely, possible, probable, suspected, rule out, etc.) which are not ruled out prior to discharge or demise are coded as if they were definitively present, for the inpatient technical side of hospital billing. This is distinctly different than the professional fee where you can only code definitive diagnoses. If you have a strong suspicion (not wild speculation) that a condition is present, best practice is to offer an uncertain diagnosis. Associate signs and symptoms with your most likely diagnosis: “Shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, and hypoxemia in the setting of cancer, probable pulmonary embolism.”

- Evolve, resolve, remove, and recap. If an uncertain diagnosis is ruled in, take away the uncertainty. If it is ruled out, don’t have 4 days of copy and pasted: “Possible eosinophilic pneumonia.” You do not have to maintain a resolved diagnosis ad infinitum. It can drop off the diagnosis list but be sure to have it reappear in the discharge summary.

- I know it can be a hASSLe to do excellent documentation, but it is critical for many reasons, most importantly for superlative patient care. More accurate coding and billing is an intended consequence. A: Acuity; S: Severity; S: Specificity (may affect the coding and the risk-adjustment implications. Acute systolic heart failure does not equal heart failure; type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic chronic kidney disease, stage 4 does not equal chronic kidney disease); and L: Linkage (of diagnosis with underlying cause or manifestation [e.g., because of, associated with, as a result of, secondary to, or from diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive encephalopathy]).

- If you have the capability to keep a running summary throughout the hospital stay, do so and keep it updated. A few moments of daily careful editing and composing can save time and effort at the back end creating the discharge summary. The follow-up care provider can reconstruct the hospital course and it is your last chance to spin the narrative for the lawyers.

- Read your documentation over. Ensure that it is clear, accurate, concise, and tells the story and the plans for the patient. Make sure that someone reading the note will know what you were thinking.

- Set up a program to self-audit documentation where monthly or quarterly, you and your partners mutually review a certain number of records and give each other feedback. Design an assessment tool which rates the quality of documentation elements which your hospital/network/service line values (clarity, copy and paste, complete and specific diagnoses, etc.). You know who the best documenters are. Why do you think their documentation is superior? How can you emulate them?

Finally, answer CDI queries. The CDI specialist is your ally, not your enemy. They want you to get credit for taking care of sick and complex patients. They are not permitted to lead the provider, so don’t ask them what they want you to write. But, if you don’t understand the query or issue, have a conversation and get it clarified. It is in everyone’s best interest to get this right.

Documentation improves patient care and demonstrates that you provided excellent patient care. Put mentation back into documentation.

Dr. Remer was a practicing emergency physician for 25 years and a physician advisor for 4 years. She is on the board of directors of the American College of Physician Advisors and the advisory board of the Association of Clinical Documentation Improvement Specialists. She currently provides consulting services for provider education on documentation, CDI, and ICD-10 coding. Dr. Remer can be reached at [email protected]

Quality over quantity

Quality over quantity

Documentation has always been part of a physician’s job. Historically, in the days of paper records, physicians saw a patient on rounds and immediately following, while still on the unit, wrote a daily note detailing the events, test results, and plans since the last note. Addenda were written over the course of the day and night as needed.

The medical record was a chronological itemization of the encounter. The chart told the patient’s story, hopefully legibly and without excessive rehashing of previous material. The discharge summary then encapsulated the hospitalization in several coherent paragraphs.

In the current electronic records environment, we are inundated with excessive and repetitious information, data without interpretation, differentials without diagnoses. Prepopulation of templated notes, defaults without edit, and dictation without revision have degraded our documentation to the point of unintelligibility. The chronological storytelling and trustworthiness of the medical record has become suspect.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is touting its “Patients over Paperwork” initiative. The solution is flawed (that is, future relaxation of documentation requirements for professional billing) because the premise is delusive. Documentation isn’t fundamentally the problem. Having clinicians jump through regulatory hoops which do not advance patients’ care, and providers misunderstanding the requirements for level-of-service billing are the essential issues. Getting no training on how to properly document in medical school/residency and receiving no formative feedback on documentation throughout one’s career compounds the problem. Having clinical documentation serve too many masters, including compliance, quality, medicolegal, utilization review, and reimbursement, is also to blame. The advent of the electronic medical record was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Many hospitals now have a clinical documentation integrity (CDI) team which is tasked with querying the provider when the health record documentation is conflicting, imprecise, incomplete, illegible, ambiguous, or inconsistent. They are charged with getting practitioners to associate clinical indicators with diagnoses and to consider removal of diagnoses which do not seem clinically valid from the existing documentation. From this explanation, you might well conclude that the CDI specialist could generate a query on every patient if they were so inclined, and you would be correct. But the goal isn’t to torture the physician – it is to ensure that the medical record is accurately depicting the encounter.

You are not being asked for more documentation by the CDI team; they are entreating you for higher-quality documentation. Let me give you some pointers to ward off queries.

- Tell the story. The most important goal of documentation is to clinically communicate to other caregivers. Think to yourself: “What would a fellow clinician need to know about this patient to understand why I drew those conclusions or to pick up where I left off?” At 2 a.m., that information, or lack thereof, could literally be a matter of life or death.

- Tell the truth. Embellishing the record or including invalid diagnoses with the intent to increase the severity of illness resulting in a more favorable diagnosis-related group – the inpatient risk-adjustment system – is considered fraud.

- You may like the convenience of copy forward, but do you relish reading other people’s copy and paste? Consider doing a documentation time-out. Before you copy and paste yesterday’s assessment and plan, stop and think: “Why is the patient still here? Why are we doing what we are doing?” If you choose to copy and paste, be certain to do mindful editing so the documentation represents the current situation and avoids redundancy. Appropriately editing copy and pasted documentation may prove more time consuming than generating a note de novo.

- Translate findings into diagnoses using your best medical judgment. One man’s hypotension may be another health care provider’s shock. Coders are not clinical and are not permitted to make inferences. A potassium of 6.7 may be hyperkalemia or it may be spurious – only a clinician may make that determination using their clinical expertise and experience. The coder is not allowed to read your mind. You must explicitly draw the conclusion that a febrile patient with bacteremia, encephalopathy, hypoxemia, and a blood pressure of 85/60 is in septic shock.

- Uncertain diagnoses (heralded by words such as: likely, possible, probable, suspected, rule out, etc.) which are not ruled out prior to discharge or demise are coded as if they were definitively present, for the inpatient technical side of hospital billing. This is distinctly different than the professional fee where you can only code definitive diagnoses. If you have a strong suspicion (not wild speculation) that a condition is present, best practice is to offer an uncertain diagnosis. Associate signs and symptoms with your most likely diagnosis: “Shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, and hypoxemia in the setting of cancer, probable pulmonary embolism.”

- Evolve, resolve, remove, and recap. If an uncertain diagnosis is ruled in, take away the uncertainty. If it is ruled out, don’t have 4 days of copy and pasted: “Possible eosinophilic pneumonia.” You do not have to maintain a resolved diagnosis ad infinitum. It can drop off the diagnosis list but be sure to have it reappear in the discharge summary.

- I know it can be a hASSLe to do excellent documentation, but it is critical for many reasons, most importantly for superlative patient care. More accurate coding and billing is an intended consequence. A: Acuity; S: Severity; S: Specificity (may affect the coding and the risk-adjustment implications. Acute systolic heart failure does not equal heart failure; type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic chronic kidney disease, stage 4 does not equal chronic kidney disease); and L: Linkage (of diagnosis with underlying cause or manifestation [e.g., because of, associated with, as a result of, secondary to, or from diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive encephalopathy]).

- If you have the capability to keep a running summary throughout the hospital stay, do so and keep it updated. A few moments of daily careful editing and composing can save time and effort at the back end creating the discharge summary. The follow-up care provider can reconstruct the hospital course and it is your last chance to spin the narrative for the lawyers.

- Read your documentation over. Ensure that it is clear, accurate, concise, and tells the story and the plans for the patient. Make sure that someone reading the note will know what you were thinking.

- Set up a program to self-audit documentation where monthly or quarterly, you and your partners mutually review a certain number of records and give each other feedback. Design an assessment tool which rates the quality of documentation elements which your hospital/network/service line values (clarity, copy and paste, complete and specific diagnoses, etc.). You know who the best documenters are. Why do you think their documentation is superior? How can you emulate them?

Finally, answer CDI queries. The CDI specialist is your ally, not your enemy. They want you to get credit for taking care of sick and complex patients. They are not permitted to lead the provider, so don’t ask them what they want you to write. But, if you don’t understand the query or issue, have a conversation and get it clarified. It is in everyone’s best interest to get this right.

Documentation improves patient care and demonstrates that you provided excellent patient care. Put mentation back into documentation.

Dr. Remer was a practicing emergency physician for 25 years and a physician advisor for 4 years. She is on the board of directors of the American College of Physician Advisors and the advisory board of the Association of Clinical Documentation Improvement Specialists. She currently provides consulting services for provider education on documentation, CDI, and ICD-10 coding. Dr. Remer can be reached at [email protected]

Documentation has always been part of a physician’s job. Historically, in the days of paper records, physicians saw a patient on rounds and immediately following, while still on the unit, wrote a daily note detailing the events, test results, and plans since the last note. Addenda were written over the course of the day and night as needed.

The medical record was a chronological itemization of the encounter. The chart told the patient’s story, hopefully legibly and without excessive rehashing of previous material. The discharge summary then encapsulated the hospitalization in several coherent paragraphs.

In the current electronic records environment, we are inundated with excessive and repetitious information, data without interpretation, differentials without diagnoses. Prepopulation of templated notes, defaults without edit, and dictation without revision have degraded our documentation to the point of unintelligibility. The chronological storytelling and trustworthiness of the medical record has become suspect.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is touting its “Patients over Paperwork” initiative. The solution is flawed (that is, future relaxation of documentation requirements for professional billing) because the premise is delusive. Documentation isn’t fundamentally the problem. Having clinicians jump through regulatory hoops which do not advance patients’ care, and providers misunderstanding the requirements for level-of-service billing are the essential issues. Getting no training on how to properly document in medical school/residency and receiving no formative feedback on documentation throughout one’s career compounds the problem. Having clinical documentation serve too many masters, including compliance, quality, medicolegal, utilization review, and reimbursement, is also to blame. The advent of the electronic medical record was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Many hospitals now have a clinical documentation integrity (CDI) team which is tasked with querying the provider when the health record documentation is conflicting, imprecise, incomplete, illegible, ambiguous, or inconsistent. They are charged with getting practitioners to associate clinical indicators with diagnoses and to consider removal of diagnoses which do not seem clinically valid from the existing documentation. From this explanation, you might well conclude that the CDI specialist could generate a query on every patient if they were so inclined, and you would be correct. But the goal isn’t to torture the physician – it is to ensure that the medical record is accurately depicting the encounter.

You are not being asked for more documentation by the CDI team; they are entreating you for higher-quality documentation. Let me give you some pointers to ward off queries.

- Tell the story. The most important goal of documentation is to clinically communicate to other caregivers. Think to yourself: “What would a fellow clinician need to know about this patient to understand why I drew those conclusions or to pick up where I left off?” At 2 a.m., that information, or lack thereof, could literally be a matter of life or death.

- Tell the truth. Embellishing the record or including invalid diagnoses with the intent to increase the severity of illness resulting in a more favorable diagnosis-related group – the inpatient risk-adjustment system – is considered fraud.

- You may like the convenience of copy forward, but do you relish reading other people’s copy and paste? Consider doing a documentation time-out. Before you copy and paste yesterday’s assessment and plan, stop and think: “Why is the patient still here? Why are we doing what we are doing?” If you choose to copy and paste, be certain to do mindful editing so the documentation represents the current situation and avoids redundancy. Appropriately editing copy and pasted documentation may prove more time consuming than generating a note de novo.

- Translate findings into diagnoses using your best medical judgment. One man’s hypotension may be another health care provider’s shock. Coders are not clinical and are not permitted to make inferences. A potassium of 6.7 may be hyperkalemia or it may be spurious – only a clinician may make that determination using their clinical expertise and experience. The coder is not allowed to read your mind. You must explicitly draw the conclusion that a febrile patient with bacteremia, encephalopathy, hypoxemia, and a blood pressure of 85/60 is in septic shock.

- Uncertain diagnoses (heralded by words such as: likely, possible, probable, suspected, rule out, etc.) which are not ruled out prior to discharge or demise are coded as if they were definitively present, for the inpatient technical side of hospital billing. This is distinctly different than the professional fee where you can only code definitive diagnoses. If you have a strong suspicion (not wild speculation) that a condition is present, best practice is to offer an uncertain diagnosis. Associate signs and symptoms with your most likely diagnosis: “Shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, and hypoxemia in the setting of cancer, probable pulmonary embolism.”

- Evolve, resolve, remove, and recap. If an uncertain diagnosis is ruled in, take away the uncertainty. If it is ruled out, don’t have 4 days of copy and pasted: “Possible eosinophilic pneumonia.” You do not have to maintain a resolved diagnosis ad infinitum. It can drop off the diagnosis list but be sure to have it reappear in the discharge summary.

- I know it can be a hASSLe to do excellent documentation, but it is critical for many reasons, most importantly for superlative patient care. More accurate coding and billing is an intended consequence. A: Acuity; S: Severity; S: Specificity (may affect the coding and the risk-adjustment implications. Acute systolic heart failure does not equal heart failure; type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic chronic kidney disease, stage 4 does not equal chronic kidney disease); and L: Linkage (of diagnosis with underlying cause or manifestation [e.g., because of, associated with, as a result of, secondary to, or from diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive encephalopathy]).

- If you have the capability to keep a running summary throughout the hospital stay, do so and keep it updated. A few moments of daily careful editing and composing can save time and effort at the back end creating the discharge summary. The follow-up care provider can reconstruct the hospital course and it is your last chance to spin the narrative for the lawyers.

- Read your documentation over. Ensure that it is clear, accurate, concise, and tells the story and the plans for the patient. Make sure that someone reading the note will know what you were thinking.

- Set up a program to self-audit documentation where monthly or quarterly, you and your partners mutually review a certain number of records and give each other feedback. Design an assessment tool which rates the quality of documentation elements which your hospital/network/service line values (clarity, copy and paste, complete and specific diagnoses, etc.). You know who the best documenters are. Why do you think their documentation is superior? How can you emulate them?

Finally, answer CDI queries. The CDI specialist is your ally, not your enemy. They want you to get credit for taking care of sick and complex patients. They are not permitted to lead the provider, so don’t ask them what they want you to write. But, if you don’t understand the query or issue, have a conversation and get it clarified. It is in everyone’s best interest to get this right.

Documentation improves patient care and demonstrates that you provided excellent patient care. Put mentation back into documentation.

Dr. Remer was a practicing emergency physician for 25 years and a physician advisor for 4 years. She is on the board of directors of the American College of Physician Advisors and the advisory board of the Association of Clinical Documentation Improvement Specialists. She currently provides consulting services for provider education on documentation, CDI, and ICD-10 coding. Dr. Remer can be reached at [email protected]

Developing guidance for patient movement requests

Clear guidelines in policy needed

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

Clear guidelines in policy needed

Clear guidelines in policy needed

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

CDC: First person-to-person spread of novel coronavirus in U.S.

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

Introduction to population management

Defining the key terms

Traditionally, U.S. health care has operated under a fee-for-service payment model, in which health care providers (such as physicians, hospitals, and health care systems) receive a fee for services such as office visits, hospital stays, procedures, and tests. However, reimbursement discussions are increasingly moving from fee-for-service to value-based, in which payments are tied to managing population health and total cost of care.

Because these changes will impact the entire system all the way down to individual providers, in the upcoming Population Management article series in The Hospitalist, we will discuss the nuances and implications that physicians, executives, and hospitals should be aware of. In this first article, we will examine the impetus for the shift toward population management and introduce common terminology to lay the foundation for the future content.

The traditional model: Fee for service

Under the traditional fee-for-service payment system, health care providers are paid per unit of service. For example, hospitals receive diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments for inpatient stays, and physicians are paid per patient visit. The more services that hospitals or physicians provide, the more money both get paid, without financial consequences for quality outcomes or total cost of care. Total cost of care includes clinic visits, outpatient procedures and tests, hospital and ED visits, home health, skilled nursing facilities, durable medical equipment, and sometimes drugs during an episode of care (for example, a hospital stay plus 90 days after discharge) or over a period of time (for example, a month or a year).

As a result of the fee-for-service payment system, the United States spends more money on health care than other wealthy countries, yet it lags behind other countries on many quality measures, such as disease burden, overall mortality, premature death, and preventable death.1,2

In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the Triple Aim framework that focused on the following:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction).

- Improving the health of populations.

- Reducing per capita cost of care.

Both public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private payers, embraced the Triple Aim to reform how health care is delivered and paid for. As such, health care delivery focus and financial incentives are shifting from managing discrete patient encounters for acute illness to managing population health and total cost of care.

A new approach: Population management

Before diving into population management, it is important to first understand the terms “population” and “population health.” A population can be defined geographically or may include employees of an organization, members of a health plan, or patients receiving care from a specific physician group or health care system. David A. Kindig, MD, PhD, professor emeritus of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”3 Dr. Kindig noted that population health outcomes have many determinants, such as the following:4

- Health care (access, cost, quantity, and quality of health care services).

- Individual behavior (including diet, exercise, and substance abuse).

- Genetics.

- The social environment (education, income, occupation, class, and social support).

- Physical environment (air and water quality, lead exposure, and the design of neighborhoods).

IHI operationally defines population health by measures such as life expectancy, mortality rates, health and functional status, the incidence and/or prevalence of chronic disease, and behavioral and physiological factors such as smoking, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, body mass index, and cholesterol.5

On the other hand, population management is primarily concerned with health care determinants of health and, according to IHI, should be clearly distinguished from population health, which focuses on the broader determinants of health.5

According to Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, one of the founding members and a past-president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, population management is a “global approach of caring for an entire patient population to deliver safe and equitable care and to more intelligently allocate resources to keep people well.”

Population management requires understanding the patient population, which includes risk stratification and redesigning and delivering services that are guided by integrated clinical and administrative data and enabled by information technology.

Cost-sharing payment models

The cornerstone of population management is provider accountability for the cost of care, which can be accomplished through shared-risk models or population-based payments. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Under shared-risk models, providers receive payment based on their performance against cost targets. The goal is to generate cost savings by improving care coordination, engaging patients in shared decision making based on their health goals, and reducing utilization of care that provides little to no value for patients (for example, preventable hospital admissions or unnecessary imaging or procedures).

Cost targets and actual spending are reconciled retrospectively. If providers beat cost targets, they are eligible to keep a share of generated savings based on their performance on selected quality measures. However, if providers’ actual spending exceeds cost targets, they will compensate payers for a portion of the losses. Under one-sided risk models, providers are eligible for shared savings but not financially responsible for losses. Under two-sided risk models, providers are accountable for both savings and losses.

With prospective population-based payments, also known as capitation, providers receive in advance a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time (for example, per month) that creates a budget to cover the cost of agreed-upon health care services. The prospective payments are risk adjusted and typically tied to performance on selected quality, effectiveness, and patient experience measures.

Professional services capitation arrangements between physician groups and payers cover the cost of physician services including primary care, specialty care, and related laboratory and radiology services. Under global capitation or global payment arrangements, health care systems receive payments that cover the total cost of care for the patient population for a defined period.

Population-based payments create incentives to provide high-quality and efficient care within a set budget.6 If actual cost of delivering services to the defined patient population comes under the budget, the providers will realize savings, but otherwise will encounter losses.

What is next?

Now that we have explained the impetus for population management and the terminology, in the next article in this series we will discuss the current state of population management. We will also delve into a hospitalist’s role and participation so you can be aware of impending changes and ensure you are set up for success, no matter how the payment models evolve.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician adviser, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start

2. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/on-several-indicators-of-healthcare-quality the-u-s-falls-short/

3. Kindig D, Asada Y, Booske B. (2008). A Population Health Framework for Setting National and State Health Goals. JAMA, 299, 2081-2083.

4. Source: https://improvingpopulationhealth.typepad.com/blog/what-are-health-factorsdeterminants.html

5. Source: http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/population-health-population-management-terminology-in-us-health-care

6. Source: http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-refresh-whitepaper-final.pdf

Defining the key terms

Defining the key terms

Traditionally, U.S. health care has operated under a fee-for-service payment model, in which health care providers (such as physicians, hospitals, and health care systems) receive a fee for services such as office visits, hospital stays, procedures, and tests. However, reimbursement discussions are increasingly moving from fee-for-service to value-based, in which payments are tied to managing population health and total cost of care.

Because these changes will impact the entire system all the way down to individual providers, in the upcoming Population Management article series in The Hospitalist, we will discuss the nuances and implications that physicians, executives, and hospitals should be aware of. In this first article, we will examine the impetus for the shift toward population management and introduce common terminology to lay the foundation for the future content.

The traditional model: Fee for service

Under the traditional fee-for-service payment system, health care providers are paid per unit of service. For example, hospitals receive diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments for inpatient stays, and physicians are paid per patient visit. The more services that hospitals or physicians provide, the more money both get paid, without financial consequences for quality outcomes or total cost of care. Total cost of care includes clinic visits, outpatient procedures and tests, hospital and ED visits, home health, skilled nursing facilities, durable medical equipment, and sometimes drugs during an episode of care (for example, a hospital stay plus 90 days after discharge) or over a period of time (for example, a month or a year).

As a result of the fee-for-service payment system, the United States spends more money on health care than other wealthy countries, yet it lags behind other countries on many quality measures, such as disease burden, overall mortality, premature death, and preventable death.1,2

In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the Triple Aim framework that focused on the following:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction).

- Improving the health of populations.

- Reducing per capita cost of care.

Both public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private payers, embraced the Triple Aim to reform how health care is delivered and paid for. As such, health care delivery focus and financial incentives are shifting from managing discrete patient encounters for acute illness to managing population health and total cost of care.

A new approach: Population management

Before diving into population management, it is important to first understand the terms “population” and “population health.” A population can be defined geographically or may include employees of an organization, members of a health plan, or patients receiving care from a specific physician group or health care system. David A. Kindig, MD, PhD, professor emeritus of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”3 Dr. Kindig noted that population health outcomes have many determinants, such as the following:4

- Health care (access, cost, quantity, and quality of health care services).

- Individual behavior (including diet, exercise, and substance abuse).

- Genetics.

- The social environment (education, income, occupation, class, and social support).

- Physical environment (air and water quality, lead exposure, and the design of neighborhoods).

IHI operationally defines population health by measures such as life expectancy, mortality rates, health and functional status, the incidence and/or prevalence of chronic disease, and behavioral and physiological factors such as smoking, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, body mass index, and cholesterol.5

On the other hand, population management is primarily concerned with health care determinants of health and, according to IHI, should be clearly distinguished from population health, which focuses on the broader determinants of health.5

According to Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, one of the founding members and a past-president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, population management is a “global approach of caring for an entire patient population to deliver safe and equitable care and to more intelligently allocate resources to keep people well.”