User login

How Hospitalist Groups Make Time for Leadership

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

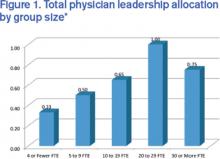

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Negotiating salaries. Improving patient flow. Increasing patient satisfaction. Reducing readmissions. Championing quality improvement efforts. Planning strategically. Handling schedule issues. Dealing with coverage issues. Working on Ebola preparation. Being on call 24 hours a day for an urgent concern from hospital administration or a hospitalist.

Hospitalist group leaders often feel they are pulled in multiple directions all at once and find that a day off really is not a day off. Leaders often are asked to take on additional responsibilities and might wonder whether they are given sufficient protected time. Leaders of larger HM groups might ask whether adding an associate chief would help cover the administrative workload. Or they may be asking whether hospitalist group leaders should receive a premium in salary, above that of other hospitalists in the group.

These are questions the State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) attempts to answer. Although there is significant variation that is dependent on many factors (i.e., group size, academic status, and whether or not the practice is part of a larger multi-site group), the 2014 SOHM found that the median total full-time equivalent (FTE) allocation for physician administration/leadership for HMGs serving adults was just 0.60. The highest-ranking physician leader most commonly had 0.25 to 0.35 FTE protected for administrative responsibilities. And the median compensation premium for group leaders was 15%.

One leadership challenge is that administrative work never stops. Group leaders often find themselves having to come in for meetings before or after night shifts. Leaders sometimes feel that the 0.30 FTE allocated for administrative responsibilities actually requires the workload of a full-time position. Yet, like other hospitalists, leaders typically work a significant number of consecutive clinical shifts to ensure continuity of care for patients, which can make juggling administrative work challenging.

Additionally, group leaders often carry a significant clinical workload. (Read about Team Hospitalist’s newest member and her split leadership-clinical roles) I would argue that this is a good thing, important for many reasons, including maintaining clinical skills, understanding the nature of work and challenges on the front lines, and being able to facilitate quality improvement efforts. Further, group leaders often are perceived to be team players by other hospitalists when they work a wide variety of shifts on all days of the week. Many programs face staffing challenges, and leaders might work extra shifts when other hospitalists are unable to fill them.

Certainly group leaders face significant challenges, but the position also comes with many rewards. Satisfaction comes from improving the program for all hospitalists in a group, from gains in hospital efficiency or flow, from systems improvements to ensure patient safety or improve patient outcomes, and from being respected by hospital administration as well as other hospitalists in the group. With a good understanding of hospital finances and patient flow, some hospitalist group leaders advance to other roles in hospital administration, such as CMO or CEO.

Although there may be no one-size-fits-all answer for the right amount of protected time or salary for group leaders, leaders clearly play a challenging but essential role in bringing value to both hospitals and hospitalist groups.

For more data from the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine and associate clinical professor at the University of California San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Time-Based Physician Services Require Proper Documentation

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

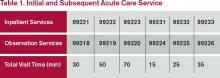

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

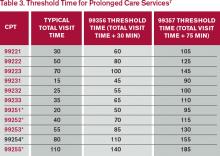

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record, and they often misunderstand the use of time when selecting visit levels. Sometimes providers may report a lower service level than warranted because they didn’t feel that they spent the required amount of time with the patient; however, the duration of the visit is an ancillary factor and does not control the level of service to be billed unless more than 50% of the face-to-face time (for non-inpatient services) or more than 50% of the floor time (for inpatient services) is spent providing counseling or coordination of care (C/CC).1 In these instances, providers may choose to document only a brief history and exam, or none at all. They should update the medical decision-making based on the discussion.

Consider the hospitalization of an elderly patient who is newly diagnosed with diabetes. In addition to stabilizing the patient’s glucose levels and devising the appropriate care plan, the patient and/or caregivers also require extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime. Coordination of care for outpatient programs and resources is also crucial. To make sure that this qualifies as a time-based service, ensure that the documentation contains the duration, the issues addressed, and the signature of the service provider.

Duration of Counseling and/or Coordination of Care

Time is not used for visit level selection if C/CC is minimal (<50%) or absent from the patient encounter. For inpatient services, total visit time is identified as provider face-to-face time (i.e., at the bedside) combined with time spent on the patient’s unit/floor performing services that are directly related to that patient, such as reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed in locations other than the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. reviewing current results or images from the physician’s office) is not allowable in calculating the total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns is also excluded, because this doesn’t reflect patient care activities. Once the provider documents all services rendered on a given calendar date, the provider selects the visit level that corresponds with the cumulative visit time documented in the chart (see Tables 1 and 2).

Issues Addressed

When counseling and/or coordination of care dominate more than 50% of the time a physician spends with a patient during an evaluation and management (E/M) service, then time may be considered as the controlling factor to qualify the E/M service for a particular level of care.2 The following must be documented in the patient’s medical record in order to report an E/M service based on time:

- The total length of time of the E/M visit;

- Evidence that more than half of the total length of time of the E/M visit was spent in counseling and coordinating of care; and

- The content of the counseling and coordination of care provided during the E/M visit.

History and exam, if performed or updated, should also be documented, along with the patient response or comprehension of information. An acceptable C/CC time entry may be noted as, “Total visit time = 35 minutes; > 50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payer may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to query payer policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance. Please remember that while this example constitutes the required elements for the notation of time, documentation must also include the details of counseling, care plan revisions, and any information that is pertinent to patient care and communication with other healthcare professionals.

Family Discussions

Family discussions are a typical event involved in taking care of patients and are appropriate to count as C/CC time. Special circumstances are considered when discussions must take place without the patient present. This type of counseling time is recognized but only counts towards C/CC time if the following criteria are met and documented:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.3

Time cannot be counted if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor (e.g. in the physician’s office) or if the time is spent counseling the family members through their grieving process.

It is fairly common for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has completed morning rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient assessment incorporating the components of an evaluation (i.e., history update and physical) and management (i.e., care plan review/revision) service, the meeting time may qualify for prolonged care services.

Service Provider

Be sure to count only the physician’s time spent in C/CC. Counseling time by the nursing staff, the social worker, or the resident cannot contribute toward the physician’s total visit time. When more than one physician is involved in services throughout the day, the physicians should select a level of service representative of the combined visits and submit the appropriate code for that level under one physician’s name.4

Consider the following example: The hospitalist takes a brief history about overnight events and reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient. He/she then leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care in anticipation that the patient will be discharged over the next few days (25 minutes). The resident is asked to continue the assessment and counsel the patient on the patient’s current disease process (20 minutes).

In the above scenario, the hospitalist is only able to report 99232, because the time spent by the resident is “nonbillable time.”

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1B. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Novitas Solutions, Inc. Frequently Asked Questions: Evaluation and Management Services (Part B). Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/faces/oracle/webcenter/page/scopedMD/sad78b265_6797_4ed0_a02f_81627913bc78/Page57.jspx?wc.contextURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH&wc.originURL=%2Fspaces%2FMedicareJH%2Fpage%2Fpagebyid&contentId=00005056&_afrLoop=1728453012371000#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D1728453012371000%26wc.originURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%252Fpage%252Fpagebyid%26contentId%3D00005056%26wc.contextURL%3D%252Fspaces%252FMedicareJH%26_adf.ctrl-state%3D610bhasa4_134. Accessed on December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Part 1: Coverage Determinations, Section 70.1. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.5. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Abraham M, Ahlman JT, Boudreau AJ, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2013:1-32.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.1C. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12: Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners, Section 30.6.15.1G. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf.

Joining forces, Part 2

The ongoing sea change in medicine has led to a substantial erosion of physician autonomy, and to ever-increasing administrative burdens that hit small practices the hardest. Does this mean that the independent private physician practice model is doomed, as some predict? Absolutely not; but it will force many solo practitioners and small groups to join forces to protect themselves.

Those practices that offer unique services, or fill an unmet niche, may be able to remain small; but most smaller practices will need to consider a larger alternative. In a previous column, I outlined the basics of one such protective strategy – merging two or more small practices into a larger entity – but there are other options to consider.

One attractive and relatively straightforward strategy is the formation of a cooperative group. In most areas, there are very likely several small practices in similar predicaments that might be receptive to discussing a collaboration on billing and purchasing. This allows each participant to maintain independence as a private practice, while pooling resources to ease the administrative burdens of all. Once that arrangement is in place, the group can consider more ambitious projects, such as the joint purchase of an EHR system, sharing of personnel to lower staffing costs, and an integrated scheduling system. The latter will be particularly attractive to participants in later stages of their careers who are considering an intermediate option, somewhere between full-time work and complete retirement.

After a time, when the structure is stabilized and everyone agrees that his or her individual and shared interests and goals are being met, an outright merger can be contemplated. Projects of this scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

A more complex but increasingly popular option is to join other small practices and providers in an independent practice association (IPA). An IPA is a legal entity organized and directed by physicians for the purpose of negotiating contracts with insurance companies on their behalf. Because of its structure, an IPA is better positioned to enter into such financial arrangements, and to counterbalance the leverage of insurers, but there are legal issues to consider. Many IPAs are vulnerable to antitrust charges because they include competing health care providers. You should check with legal counsel before signing on to an IPA, to make sure that it abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. IPAs have also been known to fail, particularly in states where they are not adequately regulated.

A possible successor to IPAs is the accountable care organization (ACO), an entity born as a component of the Affordable Care Act. While the official definition remains nebulous, an ACO is basically a network of doctors and hospitals that shares financial and medical responsibility for providing coordinated and efficient care to patients. The goal of ACO participants is to limit unnecessary spending, both individually and collectively, according to criteria established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, without compromising quality of care in the process. More than 600 ACOs had been approved by the CMS as of the beginning of 2014.

It is important to remember that the ACO model remains very much a work in progress. ACOs make providers jointly accountable for the health of their patients. They offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings.

As with IPAs, ACO ventures involve a measure of risk. ACOs that fail to meet the CMS performance and savings benchmarks can be stuck with the bill for investments made to improve care, such as equipment and computer purchases and the hiring of mid-level providers and managers, and they may be assessed monetary penalties as well. ACOs sponsored by physicians or rural providers, however, can apply to receive payments in advance to help finance infrastructure investments – a concession the Obama administration made after receiving complaints from rural hospitals.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous will be significant, and many private practitioners will be unwilling to pay it: Only 36% of physicians remained in independent practice at the end of the 2013, according to data from the American Medical Association – down from 57% in 2000 – but those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

The ongoing sea change in medicine has led to a substantial erosion of physician autonomy, and to ever-increasing administrative burdens that hit small practices the hardest. Does this mean that the independent private physician practice model is doomed, as some predict? Absolutely not; but it will force many solo practitioners and small groups to join forces to protect themselves.

Those practices that offer unique services, or fill an unmet niche, may be able to remain small; but most smaller practices will need to consider a larger alternative. In a previous column, I outlined the basics of one such protective strategy – merging two or more small practices into a larger entity – but there are other options to consider.

One attractive and relatively straightforward strategy is the formation of a cooperative group. In most areas, there are very likely several small practices in similar predicaments that might be receptive to discussing a collaboration on billing and purchasing. This allows each participant to maintain independence as a private practice, while pooling resources to ease the administrative burdens of all. Once that arrangement is in place, the group can consider more ambitious projects, such as the joint purchase of an EHR system, sharing of personnel to lower staffing costs, and an integrated scheduling system. The latter will be particularly attractive to participants in later stages of their careers who are considering an intermediate option, somewhere between full-time work and complete retirement.

After a time, when the structure is stabilized and everyone agrees that his or her individual and shared interests and goals are being met, an outright merger can be contemplated. Projects of this scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

A more complex but increasingly popular option is to join other small practices and providers in an independent practice association (IPA). An IPA is a legal entity organized and directed by physicians for the purpose of negotiating contracts with insurance companies on their behalf. Because of its structure, an IPA is better positioned to enter into such financial arrangements, and to counterbalance the leverage of insurers, but there are legal issues to consider. Many IPAs are vulnerable to antitrust charges because they include competing health care providers. You should check with legal counsel before signing on to an IPA, to make sure that it abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. IPAs have also been known to fail, particularly in states where they are not adequately regulated.

A possible successor to IPAs is the accountable care organization (ACO), an entity born as a component of the Affordable Care Act. While the official definition remains nebulous, an ACO is basically a network of doctors and hospitals that shares financial and medical responsibility for providing coordinated and efficient care to patients. The goal of ACO participants is to limit unnecessary spending, both individually and collectively, according to criteria established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, without compromising quality of care in the process. More than 600 ACOs had been approved by the CMS as of the beginning of 2014.

It is important to remember that the ACO model remains very much a work in progress. ACOs make providers jointly accountable for the health of their patients. They offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings.

As with IPAs, ACO ventures involve a measure of risk. ACOs that fail to meet the CMS performance and savings benchmarks can be stuck with the bill for investments made to improve care, such as equipment and computer purchases and the hiring of mid-level providers and managers, and they may be assessed monetary penalties as well. ACOs sponsored by physicians or rural providers, however, can apply to receive payments in advance to help finance infrastructure investments – a concession the Obama administration made after receiving complaints from rural hospitals.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous will be significant, and many private practitioners will be unwilling to pay it: Only 36% of physicians remained in independent practice at the end of the 2013, according to data from the American Medical Association – down from 57% in 2000 – but those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

The ongoing sea change in medicine has led to a substantial erosion of physician autonomy, and to ever-increasing administrative burdens that hit small practices the hardest. Does this mean that the independent private physician practice model is doomed, as some predict? Absolutely not; but it will force many solo practitioners and small groups to join forces to protect themselves.

Those practices that offer unique services, or fill an unmet niche, may be able to remain small; but most smaller practices will need to consider a larger alternative. In a previous column, I outlined the basics of one such protective strategy – merging two or more small practices into a larger entity – but there are other options to consider.

One attractive and relatively straightforward strategy is the formation of a cooperative group. In most areas, there are very likely several small practices in similar predicaments that might be receptive to discussing a collaboration on billing and purchasing. This allows each participant to maintain independence as a private practice, while pooling resources to ease the administrative burdens of all. Once that arrangement is in place, the group can consider more ambitious projects, such as the joint purchase of an EHR system, sharing of personnel to lower staffing costs, and an integrated scheduling system. The latter will be particularly attractive to participants in later stages of their careers who are considering an intermediate option, somewhere between full-time work and complete retirement.

After a time, when the structure is stabilized and everyone agrees that his or her individual and shared interests and goals are being met, an outright merger can be contemplated. Projects of this scope require careful planning and implementation, and should not be undertaken without the help of competent legal counsel and an experienced business consultant.

A more complex but increasingly popular option is to join other small practices and providers in an independent practice association (IPA). An IPA is a legal entity organized and directed by physicians for the purpose of negotiating contracts with insurance companies on their behalf. Because of its structure, an IPA is better positioned to enter into such financial arrangements, and to counterbalance the leverage of insurers, but there are legal issues to consider. Many IPAs are vulnerable to antitrust charges because they include competing health care providers. You should check with legal counsel before signing on to an IPA, to make sure that it abides by antitrust and price fixing laws. IPAs have also been known to fail, particularly in states where they are not adequately regulated.

A possible successor to IPAs is the accountable care organization (ACO), an entity born as a component of the Affordable Care Act. While the official definition remains nebulous, an ACO is basically a network of doctors and hospitals that shares financial and medical responsibility for providing coordinated and efficient care to patients. The goal of ACO participants is to limit unnecessary spending, both individually and collectively, according to criteria established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, without compromising quality of care in the process. More than 600 ACOs had been approved by the CMS as of the beginning of 2014.

It is important to remember that the ACO model remains very much a work in progress. ACOs make providers jointly accountable for the health of their patients. They offer financial incentives to cooperate, and to save money by avoiding unnecessary tests and procedures. A key component is the sharing of information. Providers who save money while also meeting quality targets are theoretically entitled to a portion of the savings.

As with IPAs, ACO ventures involve a measure of risk. ACOs that fail to meet the CMS performance and savings benchmarks can be stuck with the bill for investments made to improve care, such as equipment and computer purchases and the hiring of mid-level providers and managers, and they may be assessed monetary penalties as well. ACOs sponsored by physicians or rural providers, however, can apply to receive payments in advance to help finance infrastructure investments – a concession the Obama administration made after receiving complaints from rural hospitals.

Clearly, the price of remaining autonomous will be significant, and many private practitioners will be unwilling to pay it: Only 36% of physicians remained in independent practice at the end of the 2013, according to data from the American Medical Association – down from 57% in 2000 – but those of us who remain committed to independence will find ways to preserve it. In medicine, as in life, those most responsive to change will survive and flourish.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Fit Direct Observation of Medical Trainees Into Your Day

All of us who work with housestaff understand that a crucial component of teaching clinical medicine is to take the time to both supervise resident work and deliver constructive feedback on its quality. In the assessment of competence, trainees have “direct supervision” when an attending, senior resident, or other individual is physically present and guiding the care in real time or “indirect supervision” when work is being checked after the care has been administered.

Regardless of the level of supervision, checking in with direct observations (watching trainees do the actual work in real time) provides invaluable information for both patient care and resident assessment. Given that assessment and supervision are key components of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) Next Accreditation System, many programs are now placing particular emphasis on the time we spend observing our trainees.

How can faculty fit direct observation into an already busy day? Here are some ideas for how to adapt and leverage your workflow to create new opportunities for resident skills assessment.

Micro-Observations Matter

Gone are the days of sitting in a patient room for an hour observing a long history and physical performed by the resident or student that you are supervising. In spite of time constraints, you should aim to be at the bedside at the same time as the trainee as much as possible. Once there, take note of all that you see. For example, we often observe residents and students during bedside rounds or critical family discussions. Here are additional opportunities for trainee observation that might fit into your workflow:

- First thing in the morning, when the team is pre-rounding (this is perfect for when you are worried about a patient or are scheduled for a busy afternoon). Do NOT interrupt the resident workflow. Instruct them at the beginning of the rotation that you plan to observe unannounced. If they see you, they should continue with their normal activities. Pop in and out to catch key points, and gather the information necessary to guide patient care. Don’t take over to do teaching or feedback; that will come later in the day.

- During a procedure performed by a supervising resident who already has demonstrated technical competence. Bring a computer on wheels into the patient’s room, sit down, and catch up on charting while listening to and observing the explanations, teaching, and interaction between the patient and the resident. You can still intervene if necessary, but take appropriate steps to allow resident autonomy and the observation of high-level communication skills.

- At the bedside of a clinically unstable patient. If you are together with the team when a nurse calls with a concern, you can instruct the resident to go ahead and intervene with close follow-up in a few minutes. This allows residents to get a head start, gather information, and establish themselves as the decision-makers, while still providing an opportunity for close observation by the faculty.

- Finalizing a discharge first thing in the morning. With most hospitals focusing on discharge timeliness, faculty often discuss patients scheduled for discharge prior to or outside of formal rounds. Get to the patient! Observe the resident interacting with the patient and multidisciplinary team, confirming medication reconciliation, finalizing the discharge diagnosis and instructions, and inquiring further about barriers to adherence with the discharge regimen.

Vary Your Approach

Use a variety of formats to tell your learners what was observed. Specific, quick comments made in real time can be encouraging, and brief suggestions are usually welcome in the context of a particular patient. Other observations and feedback that need to be more sensitive or require more time are perfect to wrap up at the end of the day. Finally, the message function in the electronic medical record is another great and timely format for providing feedback on observations related to clinical documentation, differential diagnosis, and management plan.

Real-Time Recordkeeping

Record your observations as you go. Even though you are providing formative feedback throughout the month, you likely also will be expected to translate those observations into a summative end-of-rotation assessment. Whether it is on a notecard with the name of each trainee being supervised or on a printed blank copy of the end of the month assessment or other program-specific assessments, jotting down specific observations will help you recall key information.

When feedback is provided, note the date in order to guide your summative feedback discussion and the final assessment.

Keep in mind that program assessment tools often serve to remind faculty of specific behaviors that have not historically been evaluated. For example, faculty might be in the habit of providing feedback on communication skills after a family meeting but may not specifically listen for trainees to use “teach-back” concepts when explaining the plan for discharge or noting whether they actively seek input from the multidisciplinary team. A tool that lists “teach-back” or “seeks out interprofessional collaboration” as line items on the form can help to remind you of the qualities you are being asked to assess.

Although direct observation is essential in providing useful assessments during the course of supervision of trainees, there are additional ways that faculty can “see” how a trainee is doing. For example, faculty or supervising residents can “observe” an intern’s completed discharge summary in real time for important and key components. Checking this work enables you to provide an assessment of additional skills (i.e., medication reconciliation, medical knowledge, management of clinical conditions, and appropriate handoff to future care providers). As trainees progressively demonstrate competence, the degree of supervision evolves to the point of a quick verification rather than the initial detailed review.

In summary, supervising trainees well means both thinking critically about their care of patients and providing feedback. As much as we have adapted our clinical workflow to meet increasing regulatory, quality, or patient throughput requirements, we must also change our educational workflow to meet the needs of our learners.

This adaptation should not be onerous. A few simple adjustments, as outlined above, can lead to higher-quality assessments and increased satisfaction in your role as teacher. So, get back out on the wards and observe!

Dr. O’Malley is the internal medicine residency program director at Banner Good Samaritan in Phoenix, Ariz., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. She currently serves as SHM’s representative on the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Education Redesign Advisory Board, along with Dr. Caverzagie, who is associate dean for educational strategy at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in Omaha and vice president for education, clinical enterprise of the Nebraska Medical Center. Dr. Caverzagie also was a member of the ABIM and ACGME milestone writing groups.

All of us who work with housestaff understand that a crucial component of teaching clinical medicine is to take the time to both supervise resident work and deliver constructive feedback on its quality. In the assessment of competence, trainees have “direct supervision” when an attending, senior resident, or other individual is physically present and guiding the care in real time or “indirect supervision” when work is being checked after the care has been administered.

Regardless of the level of supervision, checking in with direct observations (watching trainees do the actual work in real time) provides invaluable information for both patient care and resident assessment. Given that assessment and supervision are key components of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) Next Accreditation System, many programs are now placing particular emphasis on the time we spend observing our trainees.

How can faculty fit direct observation into an already busy day? Here are some ideas for how to adapt and leverage your workflow to create new opportunities for resident skills assessment.

Micro-Observations Matter

Gone are the days of sitting in a patient room for an hour observing a long history and physical performed by the resident or student that you are supervising. In spite of time constraints, you should aim to be at the bedside at the same time as the trainee as much as possible. Once there, take note of all that you see. For example, we often observe residents and students during bedside rounds or critical family discussions. Here are additional opportunities for trainee observation that might fit into your workflow:

- First thing in the morning, when the team is pre-rounding (this is perfect for when you are worried about a patient or are scheduled for a busy afternoon). Do NOT interrupt the resident workflow. Instruct them at the beginning of the rotation that you plan to observe unannounced. If they see you, they should continue with their normal activities. Pop in and out to catch key points, and gather the information necessary to guide patient care. Don’t take over to do teaching or feedback; that will come later in the day.

- During a procedure performed by a supervising resident who already has demonstrated technical competence. Bring a computer on wheels into the patient’s room, sit down, and catch up on charting while listening to and observing the explanations, teaching, and interaction between the patient and the resident. You can still intervene if necessary, but take appropriate steps to allow resident autonomy and the observation of high-level communication skills.

- At the bedside of a clinically unstable patient. If you are together with the team when a nurse calls with a concern, you can instruct the resident to go ahead and intervene with close follow-up in a few minutes. This allows residents to get a head start, gather information, and establish themselves as the decision-makers, while still providing an opportunity for close observation by the faculty.

- Finalizing a discharge first thing in the morning. With most hospitals focusing on discharge timeliness, faculty often discuss patients scheduled for discharge prior to or outside of formal rounds. Get to the patient! Observe the resident interacting with the patient and multidisciplinary team, confirming medication reconciliation, finalizing the discharge diagnosis and instructions, and inquiring further about barriers to adherence with the discharge regimen.

Vary Your Approach

Use a variety of formats to tell your learners what was observed. Specific, quick comments made in real time can be encouraging, and brief suggestions are usually welcome in the context of a particular patient. Other observations and feedback that need to be more sensitive or require more time are perfect to wrap up at the end of the day. Finally, the message function in the electronic medical record is another great and timely format for providing feedback on observations related to clinical documentation, differential diagnosis, and management plan.

Real-Time Recordkeeping

Record your observations as you go. Even though you are providing formative feedback throughout the month, you likely also will be expected to translate those observations into a summative end-of-rotation assessment. Whether it is on a notecard with the name of each trainee being supervised or on a printed blank copy of the end of the month assessment or other program-specific assessments, jotting down specific observations will help you recall key information.

When feedback is provided, note the date in order to guide your summative feedback discussion and the final assessment.

Keep in mind that program assessment tools often serve to remind faculty of specific behaviors that have not historically been evaluated. For example, faculty might be in the habit of providing feedback on communication skills after a family meeting but may not specifically listen for trainees to use “teach-back” concepts when explaining the plan for discharge or noting whether they actively seek input from the multidisciplinary team. A tool that lists “teach-back” or “seeks out interprofessional collaboration” as line items on the form can help to remind you of the qualities you are being asked to assess.

Although direct observation is essential in providing useful assessments during the course of supervision of trainees, there are additional ways that faculty can “see” how a trainee is doing. For example, faculty or supervising residents can “observe” an intern’s completed discharge summary in real time for important and key components. Checking this work enables you to provide an assessment of additional skills (i.e., medication reconciliation, medical knowledge, management of clinical conditions, and appropriate handoff to future care providers). As trainees progressively demonstrate competence, the degree of supervision evolves to the point of a quick verification rather than the initial detailed review.

In summary, supervising trainees well means both thinking critically about their care of patients and providing feedback. As much as we have adapted our clinical workflow to meet increasing regulatory, quality, or patient throughput requirements, we must also change our educational workflow to meet the needs of our learners.

This adaptation should not be onerous. A few simple adjustments, as outlined above, can lead to higher-quality assessments and increased satisfaction in your role as teacher. So, get back out on the wards and observe!

Dr. O’Malley is the internal medicine residency program director at Banner Good Samaritan in Phoenix, Ariz., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. She currently serves as SHM’s representative on the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Education Redesign Advisory Board, along with Dr. Caverzagie, who is associate dean for educational strategy at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in Omaha and vice president for education, clinical enterprise of the Nebraska Medical Center. Dr. Caverzagie also was a member of the ABIM and ACGME milestone writing groups.

All of us who work with housestaff understand that a crucial component of teaching clinical medicine is to take the time to both supervise resident work and deliver constructive feedback on its quality. In the assessment of competence, trainees have “direct supervision” when an attending, senior resident, or other individual is physically present and guiding the care in real time or “indirect supervision” when work is being checked after the care has been administered.

Regardless of the level of supervision, checking in with direct observations (watching trainees do the actual work in real time) provides invaluable information for both patient care and resident assessment. Given that assessment and supervision are key components of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) Next Accreditation System, many programs are now placing particular emphasis on the time we spend observing our trainees.

How can faculty fit direct observation into an already busy day? Here are some ideas for how to adapt and leverage your workflow to create new opportunities for resident skills assessment.

Micro-Observations Matter

Gone are the days of sitting in a patient room for an hour observing a long history and physical performed by the resident or student that you are supervising. In spite of time constraints, you should aim to be at the bedside at the same time as the trainee as much as possible. Once there, take note of all that you see. For example, we often observe residents and students during bedside rounds or critical family discussions. Here are additional opportunities for trainee observation that might fit into your workflow:

- First thing in the morning, when the team is pre-rounding (this is perfect for when you are worried about a patient or are scheduled for a busy afternoon). Do NOT interrupt the resident workflow. Instruct them at the beginning of the rotation that you plan to observe unannounced. If they see you, they should continue with their normal activities. Pop in and out to catch key points, and gather the information necessary to guide patient care. Don’t take over to do teaching or feedback; that will come later in the day.

- During a procedure performed by a supervising resident who already has demonstrated technical competence. Bring a computer on wheels into the patient’s room, sit down, and catch up on charting while listening to and observing the explanations, teaching, and interaction between the patient and the resident. You can still intervene if necessary, but take appropriate steps to allow resident autonomy and the observation of high-level communication skills.

- At the bedside of a clinically unstable patient. If you are together with the team when a nurse calls with a concern, you can instruct the resident to go ahead and intervene with close follow-up in a few minutes. This allows residents to get a head start, gather information, and establish themselves as the decision-makers, while still providing an opportunity for close observation by the faculty.

- Finalizing a discharge first thing in the morning. With most hospitals focusing on discharge timeliness, faculty often discuss patients scheduled for discharge prior to or outside of formal rounds. Get to the patient! Observe the resident interacting with the patient and multidisciplinary team, confirming medication reconciliation, finalizing the discharge diagnosis and instructions, and inquiring further about barriers to adherence with the discharge regimen.

Vary Your Approach

Use a variety of formats to tell your learners what was observed. Specific, quick comments made in real time can be encouraging, and brief suggestions are usually welcome in the context of a particular patient. Other observations and feedback that need to be more sensitive or require more time are perfect to wrap up at the end of the day. Finally, the message function in the electronic medical record is another great and timely format for providing feedback on observations related to clinical documentation, differential diagnosis, and management plan.

Real-Time Recordkeeping

Record your observations as you go. Even though you are providing formative feedback throughout the month, you likely also will be expected to translate those observations into a summative end-of-rotation assessment. Whether it is on a notecard with the name of each trainee being supervised or on a printed blank copy of the end of the month assessment or other program-specific assessments, jotting down specific observations will help you recall key information.

When feedback is provided, note the date in order to guide your summative feedback discussion and the final assessment.

Keep in mind that program assessment tools often serve to remind faculty of specific behaviors that have not historically been evaluated. For example, faculty might be in the habit of providing feedback on communication skills after a family meeting but may not specifically listen for trainees to use “teach-back” concepts when explaining the plan for discharge or noting whether they actively seek input from the multidisciplinary team. A tool that lists “teach-back” or “seeks out interprofessional collaboration” as line items on the form can help to remind you of the qualities you are being asked to assess.

Although direct observation is essential in providing useful assessments during the course of supervision of trainees, there are additional ways that faculty can “see” how a trainee is doing. For example, faculty or supervising residents can “observe” an intern’s completed discharge summary in real time for important and key components. Checking this work enables you to provide an assessment of additional skills (i.e., medication reconciliation, medical knowledge, management of clinical conditions, and appropriate handoff to future care providers). As trainees progressively demonstrate competence, the degree of supervision evolves to the point of a quick verification rather than the initial detailed review.

In summary, supervising trainees well means both thinking critically about their care of patients and providing feedback. As much as we have adapted our clinical workflow to meet increasing regulatory, quality, or patient throughput requirements, we must also change our educational workflow to meet the needs of our learners.

This adaptation should not be onerous. A few simple adjustments, as outlined above, can lead to higher-quality assessments and increased satisfaction in your role as teacher. So, get back out on the wards and observe!

Dr. O’Malley is the internal medicine residency program director at Banner Good Samaritan in Phoenix, Ariz., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. She currently serves as SHM’s representative on the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine’s Internal Medicine Education Redesign Advisory Board, along with Dr. Caverzagie, who is associate dean for educational strategy at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in Omaha and vice president for education, clinical enterprise of the Nebraska Medical Center. Dr. Caverzagie also was a member of the ABIM and ACGME milestone writing groups.

Academic Hospitalist Groups Use Observation Status More Frequently

Insurers’ use of certain criteria to separate hospital stays into inpatient or observation status remains widespread. Observation status ensures provider reimbursement for hospitalizations deemed necessary by clinical judgment but not qualifying as inpatient care. Admission under observation status impacts the patient’s financial burden, as well, with observation admissions typically associated with increased out-of-pocket costs.

Although hospitals have always faced decreased reimbursement for observation admissions (compared to inpatient admissions), new penalties attached to readmission for patients discharged from an inpatient stay raise the potential to impact hospitalist practice by incentivizing increased use of observation status for hospitalizations in order to avoid readmission penalties.

Have readmission penalties associated with inpatient admissions actually led to increased use of observation status by hospitalist groups?

SHM’s 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report provides insight into this question. In groups serving adults only, observation discharges accounted for 16.1% of all discharges (see Figure 1). If the survey’s reported same-day admission and discharge rate of 3.5%, collected separately this year, can be assumed to be largely reflective of observation status discharges, then the true percentage of discharges under observation status is likely closer to 19.6%.

–Dr. Smith

The question of determining whether to bill episodes as inpatient or observation status was asked in the 2012 survey, as well, though by a different methodology: 20% of admissions were billed as observation status by hospitalist practices seeing adults only. Even with some observation admissions in 2012 being converted to inpatient status later in the hospital stay (a factor accounted for in the 2014 survey by changing the wording of the survey so that it asks about status at discharge), not much overall change in hospitalist group practice can be appreciated.

Does the overall observation status use rate tell the whole story?

When 2012 and 2014 survey data are separated by academic status, a clear change in practice over time can be seen. Academic HMGs experienced an increase in use of observation status, from 15.3% of admissions in 2012 to 19.4% of discharges in 2014 (or 22.8% in 2014, if same-day hospital stay responses are added to the observation data). In comparison, nonacademic hospitalist practices reported a decrease in observation status utilization, from 20.4% of admissions in 2012 to 15.6% of discharges in 2014 (or 19.2%, accounting for same-day discharges as observation status).

Academic HMGs, which frequently rely on housestaff for the finer points of patient care documentation, must consequently rely on documentation largely written by providers with less experience and incentive to optimize documentation for billing, compared to experienced hospitalists. It’s plausible to speculate that the benefits associated with compensation for inpatient status for hospitals, compared to the risks of financial penalty associated with billing under inpatient status, could be different for academic than for nonacademic hospitalist groups, due to the differences in the quality of documentation between the two practice types, and that academic HMGs, or the hospitals they work with, see the risks associated with inpatient status billing as high enough to change billing practices. Nonacademic hospitalist groups, on the other hand, may rely on the experience of their retained hospitalists to document justification for inpatient status more effectively, and may thus maximize the financial benefit of inpatient status utilization sufficiently to overcome associated financial risks.

In an ever-changing reimbursement and political advocacy landscape, future SHM surveys will be pivotal in assessing what happens with trends surrounding use of observation status for episodes of hospital care.

Dr. Smith is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Northwestern University in Chicago, Ill., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Insurers’ use of certain criteria to separate hospital stays into inpatient or observation status remains widespread. Observation status ensures provider reimbursement for hospitalizations deemed necessary by clinical judgment but not qualifying as inpatient care. Admission under observation status impacts the patient’s financial burden, as well, with observation admissions typically associated with increased out-of-pocket costs.

Although hospitals have always faced decreased reimbursement for observation admissions (compared to inpatient admissions), new penalties attached to readmission for patients discharged from an inpatient stay raise the potential to impact hospitalist practice by incentivizing increased use of observation status for hospitalizations in order to avoid readmission penalties.