User login

Evidence-based guidelines for management of nursing home-acquired pneumonia

—William Osler, ca 1900

We convened a multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel to develop comprehensive evidence and consensus-based guidelines for managing nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The panel began with explicit criteria for process of care quality measures, performed a comprehensive review of the English-language literature, evaluated the quality of the evidence, and drafted a set of proposed guidelines. The panel reviewed the draft, an annotated bibliography, and data from a study of 30-day survival from nursing home-acquired pneumonia, and then participated in an all-day meeting in January 2001. Using a modified Delphi process, the panel refined the guidelines and developed a care pathway. The guidelines recommend a comprehensive approach, including immunization of staff and residents, and communication between nursing staff and the attending physician within 2 hours of symptom onset. Probable pneumonia was defined. An algorithm was delineated for assessing the patient’s wishes for hospitalization and aggressive care, and deciding on hospitalization based on the severity of the illness as well as the capacity of the nursing home to provide acute care. The timing and extent of evaluation in a nursing home relative to the rapid initiation of antibiotics should depend on whether the patient has any unstable vital signs. An antibiotic covering Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, common gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus should be given for 10 to 14 days, orally if the patient is able to take medications by mouth.

Mortality from nursing home-acquired pneumonia is as high as 44%,1and nearly a third of those who survive suffer significant functional decline.2 Nursing home-acquired pneumonia is an entity distinct from community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly and nosocomial pneumonia. Older adults in nursing homes are more likely than community-dwelling older persons, but less likely than hospitalized elderly patients, to be colonized with gram-negative rods and pathogens with multiple antibiotic resistance.3-8Inappropriate use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities contributes significantly to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance generally.9 In addition, most nursing home residents are cognitively impaired, immunocompromised, have multiple functional deficits, or have dysphagia, which further contributes to their vulnerability.10

In recent work11 with a national nursing home sample, we showed that high quality care, including appropriate antibiotic use, hospitalization when indicated, and rapid identification of and response to respiratory symptoms, is associated with improved survival of residents who acquire pneumonia. Unfortunately, we also found that many of the 58 nursing homes in our study provided less than adequate care; for example, only 31% of residents received antibiotics within one 8-hour shift of symptom onset.11

Convincing evidence indicates that treatment guidelines improve pneumonia outcomes in acute care settings,12,13 and preliminary indications suggest that they may have a positive impact on processes of care in nursing facilities.14 Three guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of infections in nursing homes have been published in the last 2 years,15-17but these guidelines are not specific to pneumonia. The only guideline specific to nursing home-acquired pneumonia used current community practice in 1 metropolitan area to define guidelines for antibiotic use.18 The outline specifically does not address issues of diagnostic work-up, decision to hospitalize, or timing of initial antibiotic treatment. We therefore convened a national panel of experts in infectious disease, pharmacology, pulmonology, geriatrics, and nursing to develop comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for management of nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The guidelines address immunization, infection control, timing and thoroughness of nurse and physician evaluation of lower respiratory tract infections, criteria for hospitalization, and criteria for antibiotic spectrum, timing, route, and duration.

Guideline development

Literature review

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken using Ovid (http://www.ovid.com/) and the “explode” version of each of the following key words: nursing homes, long-term care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and pneumonia, to search MEDLINE from 1975 through 2000. Only studies published in English and germane to nursing home residents in the United States and Canada were examined. Results of the search were augmented by a local mulidisciplinary team, consisting of faculty in geriatric studies, infectious disease, pulmonology, and pharmacology at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, an internist who practices exclusively in nursing homes, and a nursing home nurse consultant. This team developed explicit criteria for nursing home-acquired pneumonia processes of care, as described previously.11

Construction of draft guidelines

Working with the explicit criteria developed by the local team, the data from our retrospective study of process of care and survival, and the published literature on nursing home-acquired pneumonia, we drafted an initial set of comprehensive guidelines. We then graded the recommendations according to a standard system for defining quality, with 3 categories for recommendation strength (A, good evidence; B, moderate evidence; C, poor evidence) and 3 grades for quality of evidence (I, at least 1 properly randomized, controlled trial; II, at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies, multiple time series, or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees).19 Published Canadian and American guidelines for treatment of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia formed a template for the antibiotic recommendations.20,21

Modified delphi process

A multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel was recruited from nationally recognized experts in nursing home-acquired pneumonia, geriatric and infectious disease pharmacology, pneumonia treatment guideline development, and nursing home nurses (see Appendix). Panel members received an annotated version of the draft guidelines with a bibliography and the questionnaire described below. A table of the activity spectrum of currently available antibiotics, a table summarizing published reports on the microbiology of nursing home-acquired pneumonia (see Table 1), and tables summarizing our retrospective study of care processes in nursing homes and 30-day survival11were also included in that mailing.

The questionnaire asked whether each proposed guideline was clear, specific, feasible, measurable, and commensurate with his or her usual practice. Panelists were also asked to score each proposed guideline on its importance in determining the outcome of a nursing home-acquired pneumonia episode on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being not important and 5 being extremely important. Suggestions for substantive changes were elicited. The questionnaires were returned 2 weeks before an all-day, face-to-face meeting. For each guideline we calculated the percentage of panelists who agreed that it met each of the 5 criteria outlined. The means and standard deviations of the guideline weights were analyzed. Suggestions for substantive changes in the guidelines were collated and presented in tabular form, along with results of the survey, at the beginning of the meeting.

The most controversial guidelines were found to be classification of symptoms into a diagnosis of probable pneumonia, criteria for hospitalization, evaluation and treatment of residents not being hospitalized, and antibiotic choice. Less controversial were recommendations for immunization and treatment duration. The panel meeting devoted 2 hours to each of the 4 most controversial guidelines. The draft guideline was read and results of the pre-meeting ratings and suggestions were discussed. The guidelines were revised substantially and voted on. A care pathway was also developed at the meeting.

Because revisions were extensive and 1 of the panelists was participating by telephone, a copy of the revised guidelines and care pathway was sent to the panelists for further review and comment after the meeting. At that time, they were asked to rate each guideline on how confident they were that the recommendation should be included as part of the proposed guidelines using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 denoting not confident and 5 denoting very confident. Because the lowest mean confidence rating was 3.4 after this iterative process, no guidelines were dropped from the set agreed upon at the meeting. Final revisions were made to the guidelines and their respective strength-and-quality-of-evidence grades, and approved by the panel.

TABLE 1

Nursing home pneumonia etiology according to studies using verified sputum* or blood culture

| Study | N | Year | Streptococcus pneumoniae (%) | Staphylococcus aureus (%) | Gram-negative rods (%) | Haemophilus influenzae (%) | Anerobes (%) | Multiple organisms (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez3 | 414 | 1988 | 32 | — | 29 | — | — | 22% |

| Peterson4 | 123 | 1988 | 10 | 3 | 21 | 9 | — | — |

| Marrie5 | 131 | 1989 | 16 | 13 | 13 | — | 4 | — |

| Hirata-Davis6 | 50 | 1991 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 10 | — | — |

| Drinka7 | 17 | 1994 | 30 | 6 | — | 25 | — | (Atypicals = 0) |

| Marrie and Blanchard51 | 71 | 1997 | 2/5 | — | 2/5 | — | — | — |

| Pick8 | 257 (98 aspirations) | 1996 | 3 | 38 | 6 | 3 | — | Group B streptococci 43% |

| *Expectorated sputum with > 25 white blood cells per low-power field and < 10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field. | ||||||||

Recommendations

Each of the 25 guidelines is presented below. The strength and quality of evidence rating and panelists’ mean confidence score are shown in parentheses.

Prevention

- Residents should be vaccinated against Streptococcus pneumoniae at admission unless there is documentation of vaccination within 5 years preceding admission or they were allergic to previous pneumococcal vaccine. (A/I/4.7)22-27

- Residents should be vaccinated against influenza by December of each year if they are not allergic to eggs or previous influenza vaccine. Residents admitted between December and March should be vaccinated if not already immunized for the current influenza season, and they are not allergic as described above. (A/I/5.0)27,28

- The nursing facility should provide and strongly recommend immunization against influenza for all employees by December of each year if the employee is not allergic to eggs or previous vaccine. (A/I/4.9)29,30

Initial evaluation of residents with respiratory impairment

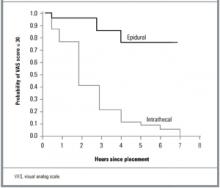

Once a resident has been noted to have a significant change in respiratory status, the clinician should use the care pathway outlined in (Figure 1). The panel believed that nurse practitioners and physician assistants with appropriate supervision could substitute for physician care in all pathway activities. Guideline recommendations 4 through 8 address the rapid recognition and physician notification of serious respiratory symptoms:

- Physicians with nursing home residents should be available or have cross-coverage by pager 24 hours/day, 7 days/week. (Absent/Absent/4.8)

- Nursing home staff should page the physician within 1 hour when a resident is noted to have any 2 of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; increased or newly purulent sputum; decline in cognitive, physical, or functional status; fever; hypothermia; dyspnea; tachypnea; chest pain; or new or worsening hypoxemia. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- Nurse evaluation at symptom onset should include, at least, vital signs (temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) and oxygen saturation if a pulse oximeter is available in the facility. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- When notified as in guideline #5, the physician should call back within 1 hour. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- If the nurse does not hear back from the physician within 1 hour, he or she should notify the director of nurses or designee. The nurse and the director of nurses should agree on a plan to notify the medical director or designee and ask him or her to assume care of that episode until the medical director can contact the attending physician. (Absent/Absent/3.5)

Once the physician has been notified, he or she must decide whether pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the reported change.

- The physician and nursing home staff should concur that pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the change noted in guideline #5 above, if the patient has 2 or more of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; newly purulent sputum; fever of 100.5°F or 2°F more than baseline; hypothermia < 96°F; dyspnea; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute; tachycardia; new or worse hypoxemia; pleuritic chest pain; a decline in cognitive or functional status; or new rales or rhonchi on chest examination. Such patients will be referred to in the remainder of the guidelines as having “probable pneumonia.” (C/III/4.1)5,31

FIGURE

Care pathway for nursing home-acquired pneumonia

Venue of care

Once pneumonia is considered likely, the physician must decide whether to hospitalize the resident. Because nursing home-acquired pneumonia is frequently the terminal event of a long and debilitating illness, this decision is especially important.

- The patient’s desire for hospitalization and aggressive care should be assessed directly if possible, or by chart review or discussion with the patient’s health care proxy. Patients with prior orders for no hospitalization or who refuse hospitalization (personally or by proxy) should not be hospitalized. (Absent/Absent/4.8)32

For patients willing to be hospitalized, the panel suggested categorization into 1 of 3 groups: patients whose severity of illness mandates hospitalization; patients whose severity of illness is such that the nursing home’s capacity to deliver acute care should be considered; and patients so stable that treatment in the nursing home is preferable. This set of recommendations is based on 2 retrospective series which suggest that only patients with elevated respiratory rates benefit from hospitalization2 and that patients hospitalized according to criteria similar to these tended to have better survival.11 These recommendations are modeled after Fine’s prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia,33 and take into account the mortality prediction model of Naughton and coworkers34 for nursing home-acquired pneumonia.

- Patients with 2 or more of the following symptoms should be hospitalized (C/III/4.1)2,11:

- If the nursing home cannot provide vital sign assessment every 4 hours, laboratory access, parenteral hydration, and 2 licensed nurses per shift in the facility, serious consideration should be given to hospitalizing patients with any one of the above. (C/III/4.1)11,35,36

- Patients with none of the above should be treated in the nursing home unless the patient or proxy insists on hospitalization. (B/II/4.5)2,11,33,34

Evaluating and monitoring patients who remain in nursing homes

- Nurse evaluation each shift should include, at least, vital signs with measured respiratory rate and oxygen saturation until symptoms resolve. (C/III/4.5)16,17,37

Although a study published by Mehr and colleagues38 after the panel proceedings suggested that patients with multiple signs and symptoms of nursing home-acquired pneumonia are so likely to have an infiltrate on chest x-ray that treating without first obtaining an x-ray may be acceptable, the panel recommended that:

- Patients with probable pneumonia should have a chest x-ray. (C/III/4.2)15,39

- Patients with probable pneumonia should be evaluated in person by the physician, ideally within 24 hours and certainly within 72 hours. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- Because of the issue of antibiotic resistance, and not because of anticipated direct patient benefit, patients for whom antibiotics are ordered should have 1 blood culture drawn if this can be accomplished without delaying initiation of antibiotics longer than 1 hour. (C/III/3.4)37,40

The panel did not recommend sputum Gram’s stain and culture even though 2 recent guidelines on evaluating infection in long-term care facilities did.15,16 Obtaining high-quality sputa in this population is notoriously difficult.1

TABLE 2

Key recommendations of evidence

| Guideline | Strength/quality of evidence |

|---|---|

| 1, 2, 3: Vaccinate staff and residents against influenza and residents against Streptococcus pneumoniae. | A/I |

| 4, 5, 6, 7, 8: Nursing assessment of change in condition should include a full set of vital signs with oxygen saturation. Initial communication with the physician should be completed within 2 hours of symptom onset. | Absent |

| 9: Probable pneumonia is defined as 2 or more of the following: new or worsening cough; newly purulent sputum; temperature > 100.5°F, < 96°F, or 2°F more than baseline; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute, tachycardia; new or worsening hypoxia; pleuritic chest pain; decline in cognitive or functional status; physical findings on chest examination such as rales or rhonchi. | C/III |

| 10: Patient’s desire for hospitalization and aggressive care should be assessed at the onset of the episode and directly with the patient, if possible. | Absent |

| 11, 12, 13: The decision to hospitalize should be based on a combination of vital sign criteria, active comorbidity, and nursing home capabilities. | C/III |

| 23: The antibiotic chosen as empiric therapy should cover S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, common gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus. | B/II |

| 25: Use oral antibiotics if the patient can take oral medication. | A/I |

| Recommendations were graded according to a standard system,19with 3 categories for recommendation strength (A, good evidence; B, moderate evidence; C, poor evidence) and 3 grades for quality of evidence (I, at least 1 properly randomized, controlled trial; II, at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies, multiple time series, or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees). | |

Antibiotic use

Extrapolating from studies of hospital- and community-acquired pneumonia indicating a survival benefit for patients who receive antibiotics within 8 hours of arrival in hospital or symptom onset,40 the panel made the following recommendations, which do not conflict with 3 recently published guidelines on use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities.16

- Patients being sent immediately to the hospital should receive 1 dose of parenteral antibiotics prior to leaving the nursing home unless this treatment would delay transport for more than 1 hour. The hospital should be notified of the antibiotic given. (B/II/4.4)40

- A single dose of antibiotics should be ordered immediately (simultaneously with the chest x-ray order) if the patient has any of the following: systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or 20 mm Hg less than baseline; oxygen saturation < 90% on room air at sea level; pulse > 130 beats per minute; respiratory rate > 30 breaths per minute; or temperature > 101.5°F. (B/II/4.5)40,41

- For patients with probable pneumonia who are stable (oxygen saturation > 90%, systolic blood pressure > 90 mm Hg, pulse < 120 beats per minute, and respiratory rate < 30 beats per minute), a decision to use antibiotics may await results of the chest x-ray if they will be available within 24 hours. (C/III/3.8)40,41 If the chest x-ray does not confirm the suspicion of pneumonia, consideration should be given to stopping antibiotic treatment.

- Antibiotics, if ordered, should be delivered to the patient within 4 hours of the orders being given by the physician. (B/II/4.5)40,41

- If the patient is able to take oral medication, that route is preferred, except that patients being sent to the hospital should have 1 parenteral dose. (A/I/4.7)4,42,43

Because it is difficult to obtain a bacteriologic diagnosis in most nursing home residents, the initial choice of antibiotic must be empiric. Based on the published studies of nursing home-acquired pneumonia bacteriology, half of which used high-quality sputum samples (> 25 white blood cells per low-power field and < 10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field, (see Table 1), the panel recommended a broad-spectrum antibiotic covering S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus. In areas or facilities where resistance of S pneumoniae to penicillin is known to be high, treatment should be modified accordingly. These recommendations differ from those proposed by the Society of Health Care Epidemiology of America in their 2000 position paper,16 but are similar to those proposed by Naughton and Mylotte18 in their guideline derived from current community practice in Buffalo, New York, except that the current panel recommends the addition of a macrolide. These differences are driven by controversy over the relative importance of gram-negative rods as etiologic vs colonizing organisms in nursing home-acquired pneumonia; the relative importance of atypical organisms; and by the current panel’s concern that an important percentage of bacteria in long-term care facilities may already be resistant to many of the antibiotics endorsed by the Society of Health Care Epidemiology of America. Moreover, 3 studies have suggested a survival benefit of broader-spectrum empiric treatment in nursing home-acquired pneumonia.11,44,45

- The antibiotic chosen as empiric therapy needs to cover S pneumoniae, H influenzae, gram-neg-ative rods, and S aureus. (B/II/4.5)37,31,39,44-51

- Currently acceptable choices for empiric treatment include: antipneumococcal quinolones or an extended-spectrum beta-lactam plus a macrolide other than erythromycin. (C/III/4.5)45,52,53

- Treat for 10 to 14 days. (B/II/4.4)18,25

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel of nationally recognized experts in nursing home-acquired pneumonia achieved consensus in proposing guidelines and a care pathway to prevent, recognize, evaluate, and treat nursing home-acquired pneumonia. For immunization and use of oral antibiotics when possible, evidence was sufficient to make a strong (A/I) recommendation. Even in areas in which evidence was lacking, the panel agreed readily. Thus for most of the 25 proposed guidelines, strong evidence and/or ready consensus existed among national experts from many disciplines.

The process of guideline development that we followed was systematic and meticulous. The panel was diverse, including nurses and pharmacologists, nationally recognized experts in infectious disease, nursing home care, geriatrics, and pulmonology. The breadth of the panel’s collective experience, and the rigor of the Delphi process we followed, lend face validity to the proposed guidelines despite some differences with other guidelines, as noted above.45,53

These guidelines are uniquely comprehensive. They address management of pneumonia from prevention through diagnosis, the decision to hospitalize, and treatment. Such a comprehensive approach is essential given the many people and systems that interact in the care of nursing home residents, a uniquely frail and vulnerable population. Evidence from our work and others11,13 suggests that only a comprehensive approach will, over time, improve the outcome of this important illness.

The guidelines have 2 important limitations. They have not yet been approved by any official professional society, nor have they been tested prospectively. Prospective testing is required to validate whether, in fact, the proposed guidelines can be implemented and, if implemented, they will improve mortality, function, cost of care, rehospitalization rates, and community discharge rates. We chose not to seek official approval of the guidelines until they can be proven effective.

We believe the proposed guidelines can and should be used to the fullest extent possible by nursing homes and physicians who practice there, because the combination of evidence and consensus is strong. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia causes excess mortality and functional loss. The proposed guidelines, based as they are in empiric evidence, common sense, and expert consensus, offer some hope of decreasing rehospitalization and cost, mitigating functional decline, and improving survival.

APPENDIX: PANEL MEMBERS . Diana Blake, RN, Western Hills Health Care Center, Lakewood, CO; JoAnn G. Congdon, RN, PhD, University of Colorado HSC, Denver, CO; Douglas Fish, PharmD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Evelyn Hutt, MD, University of Colorado HSC, Denver, CO; Denise Iskra, RN, Life Care of Westminster, Westminster, CO; Andrew M. Kramer, MD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Thomas J. Marrie, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Mark Loeb, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Wayne C. McCormick, MD, MPH, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA; Annette M. Medina-Walpole, MD, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; David R. Mehr, MD, MS, University of Missouri–Columbia, Columbia, MO; Michael S. Niederman, MD, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Mineola, NY; Phillip K. Peterson, MD, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; J. Mark Ruscin, PharmD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Thomas T. Yoshikawa, MD, Charles Drew University, Los Angeles, CA.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of the panel for their thoughtful participation and willingness to review multiple drafts of the guidelines and manuscript; Steven Teutsch, MD, Senior Director, Outcomes Research and Management, Merck & Co., Inc., for his support and advice; Lisa Lampinen for manuscript preparation; and Merck & Co., Inc., for funding.

1. Medina-Walpole AM, Katz PR. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:1005-15.

2. Fried TR, Gillick MR, Lipsitz LA. Short-term functional outcomes of long-term care residents with pneumonia treated with and without hospital transfer. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:302-6.

3. Alvarez S, Shell CG, Woolley TW, et al. Nosocomial infections occurring in nursing home residents. J Gerontol 1988;43:M9-17.

4. Peterson PK, Stein DJ, Guay D, et al. Prospective study of lower respiratory tract infections in an extended-care nursing home program: potential role of oral ciprofloxacin. Am J Med 1988;85:164-71.

5. Marrie TJ, Durant H, Yates L. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: 5-year prospective study. Rev Infect Dis 1989;11:586-99.

6. Hirata-Davis CAI, Stein DJ, Guay DRP, Gruninger RP, Peterson PK. A randomized study of ciprofloxacin versus ceftriaxone in the treatment of nursing home-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:979-85.

7. Drinka PJ, Gauerke C, Voeks S, et al. Pneumonia in a nursing home. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:650-2.

8. Pick N, McDonald A, Bennett N, et al. Pulmonary aspiration in a long-term care setting: clinical and laboratory observations and an analysis of risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996;44:763-8.

9. John JF, Ribner BS. Antibiotic resistance in long-term care facilities. Infec Control Hosp Epidemiol 1991;12:245-50.

10. Gabrel CS. Characteristics of elderly nursing home current residents and discharges: data from the 1997 National Nursing Home Survey. Advance Data 2000;312:1-15.

11. Hutt E, Frederickson E, Kramer AM. Association between quality of care and survival in nursing home acquired pneumonia. Abstract presented at: American Geriatrics Society 58th Annual Scientific Meeting; May 9-13, 2001; Chicago, IL.

12. Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, et al. A computer-assisted management program for antibiotics and other antiinfective agents. N Engl J Med 1998;338:232-8.

13. Dempsey CL. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia: outcomes from a clinical process improvement program. Pharmacotherapy 1995;15:33S-38S.

14. Naughton BJ, Mylotte JM, Ramadan F, Karuza J, Priore RL. Antibiotic use, hospital admissions and mortality before and after implementing guidelines for nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1020-4.

15. Bentley DW, Bradley S, High K, Schoenbaum S, Taler G, Yoshikawa TT. Practice guideline for evaluation of fever and infection in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:210-22.

16. Nicolle LE, Bentley DW, Garibaldi R, Neuhaus E, Smith PW. Antimicrobial use in long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000;21:537-45.

17. Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term-care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infec Control Hosp Epidemiol 2001;22:120-4.

18. Naughton B, Mylotte JM. Treatment guideline for nursing home-acquired pneumonia based on community practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:82-8.

19. Gross PA, Swenson DL, Dellinger EP, et al. Purpose of quality standards for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18:421.-

20. Niederman MS, Bass JB, Campbell GD, et al. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:1418-26.

21. Campbell GD, Niederman MS, Broughton WA, et al. Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventative strategies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;153:1711-25.

22. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:2666-77.

23. Ortqvist A, Hedlund J, Burman L, et al. Randomised trial of 23-valent pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in prevention of pneumonia in middle-aged and elderly people. Lancet 1998;351:399-403.

24. Koivula I, Sten M, Leinonen M, Makela PH. Clinical efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine in the elderly: a randomized, single-blind population-based trial. Am J Med 1997;103:281-90.

25. Quick RE, Hoge CW, Hamilton DJ, Whitney CJ, Borges M, Kobayashi JM. Underutilization of pneumococcal vaccine in nursing homes in Washington state: report of a serotype-specific outbreak and a survey. Am J Med 1993;94:149-52.

26. Nuorti JP, Butlere JC, Crutcher JM, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant pneumococcal pneumonia and bacteremia among unvaccinated nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1861-8.

27. Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2058-64.

28. Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS, Lau J, Levandowski RA. The efficacy of influenza vaccine in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:518-27.

29. Potter J, Stott DJ, Roberts MA, et al. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in long-term-care hospitals reduces the mortality of elderly patients. J Infect Dis 1997;175:1-6.

30. Carman WF, Elder AG, Wallace LA, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination of health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:93-7.

31. McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, et al. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control 1991;19:1-7.

32. Mehr DR. Nursing home acquired pneumonia: how and where to treat? J Am Board Fam Pract 1997;10:168-70.

33. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-50.

34. Naughton BJ, Mylotte JM, Tayara A. Outcome of nursing home-acquired pneumonia: derivation and application of a practical model to predict 30 day mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:1292-9.

35. Li J, Birkhead GS, Strogatz DS, Coles FB. Impact of institution size, staffing patterns, and infection control practices on communicable disease outbreaks in New York state nursing homes. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:1042-9.

36. Kutner JS, Kramer AM, Mortimore EF, Feuerberg MA. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: a qualitative study. Ann Long-Term Care 1998;6:1-10.

37. Meehan TP, Chua-Reyes JM, Tate J, et al. Process of care performance, patient characteristics, and outcomes in elderly patients hospitalized with community-acquired or nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2000;117:1378-85.

38. Mehr DR, Binder EF, Kruse RL, Zweig SC, Madsen RW, D’Agostino RB. Clinical findings associated with radiographic pneumonia in nursing home residents. J Fam Pract 2001;50:931-7.

39. Bentley DW. Bacterial pneumonia in the elderly: clinical features, diagnosis, etiology, and treatment. Gerontology 1984;30:297-307.

40. Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Quality of care, process, and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA 1997;278:2080-4.

41. Luna CM, Vujacich P, Niederman MS, et al. Impact of BAL data on the therapy and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 1997;111:676-85.

42. Degelau J, Guay D, Straub K, Luxenberg MG. Effectiveness of oral antibiotic treatment in nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:245-51.

43. Medina-Walpole AM, McCormick WC. Provider practice patterns in nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:187-92.

44. Mehr DR, Foxman B, Colombo P. Risk factors for mortality from lower respiratory infections in nursing home patients. J Fam Pract 1992;34:585-91.

45. Gleason PP, Meehan TP, Fine JM, Galusha DH, Fine MJ. Associations between initial antimicrobial therapy and medical outcomes for hospitalized elderly patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2562-72.

46. Garb JL, Brown RB, Garb JR, Tuthill RW. Differences in etiology of pneumonias in nursing home and community patients. JAMA 1978;240:2169-72.

47. Nicolle LE, McIntyre M, Zacharies H, MacDonnell JA. Twelve-month surveillance of infections in institutionalized elderly men. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;32:513-9.

48. Phillips SL, Branaman-Phillips J. The use of intramuscular cefoperazone versus intramuscular ceftriaxone in patients with nursing home-acquired pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:1071-4.

49. Chow CW, Senathiragah N, Rawji J, Chan M, Lee-Pack LR, Chan CK. Interim report on drug utilization review of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia: clinical, bacteriological and radiological spectrum. Can J Infect Dis 1994;5(Suppl C):20C-27C.

50. Muder RR. Pneumonia in residents of long-term care facilities: epidemiology, etiology, management, and prevention. Am J Med 1998;105:319-30.

51. Marrie TJ, Blanchard W. A comparison of nursing home-acquired pneumonia patients with patients with community-acquired pneumonia and nursing home patients without pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:50-5.

52. Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Sande MA. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 30th ed. Hyde Park, VT: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc.; 2001.

53. Troy CJ, Peeling RW, Ellis AG, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae as a new source of infectious outbreaks in nursing homes. JAMA 1997;277:1214-8.

—William Osler, ca 1900

We convened a multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel to develop comprehensive evidence and consensus-based guidelines for managing nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The panel began with explicit criteria for process of care quality measures, performed a comprehensive review of the English-language literature, evaluated the quality of the evidence, and drafted a set of proposed guidelines. The panel reviewed the draft, an annotated bibliography, and data from a study of 30-day survival from nursing home-acquired pneumonia, and then participated in an all-day meeting in January 2001. Using a modified Delphi process, the panel refined the guidelines and developed a care pathway. The guidelines recommend a comprehensive approach, including immunization of staff and residents, and communication between nursing staff and the attending physician within 2 hours of symptom onset. Probable pneumonia was defined. An algorithm was delineated for assessing the patient’s wishes for hospitalization and aggressive care, and deciding on hospitalization based on the severity of the illness as well as the capacity of the nursing home to provide acute care. The timing and extent of evaluation in a nursing home relative to the rapid initiation of antibiotics should depend on whether the patient has any unstable vital signs. An antibiotic covering Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, common gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus should be given for 10 to 14 days, orally if the patient is able to take medications by mouth.

Mortality from nursing home-acquired pneumonia is as high as 44%,1and nearly a third of those who survive suffer significant functional decline.2 Nursing home-acquired pneumonia is an entity distinct from community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly and nosocomial pneumonia. Older adults in nursing homes are more likely than community-dwelling older persons, but less likely than hospitalized elderly patients, to be colonized with gram-negative rods and pathogens with multiple antibiotic resistance.3-8Inappropriate use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities contributes significantly to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance generally.9 In addition, most nursing home residents are cognitively impaired, immunocompromised, have multiple functional deficits, or have dysphagia, which further contributes to their vulnerability.10

In recent work11 with a national nursing home sample, we showed that high quality care, including appropriate antibiotic use, hospitalization when indicated, and rapid identification of and response to respiratory symptoms, is associated with improved survival of residents who acquire pneumonia. Unfortunately, we also found that many of the 58 nursing homes in our study provided less than adequate care; for example, only 31% of residents received antibiotics within one 8-hour shift of symptom onset.11

Convincing evidence indicates that treatment guidelines improve pneumonia outcomes in acute care settings,12,13 and preliminary indications suggest that they may have a positive impact on processes of care in nursing facilities.14 Three guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of infections in nursing homes have been published in the last 2 years,15-17but these guidelines are not specific to pneumonia. The only guideline specific to nursing home-acquired pneumonia used current community practice in 1 metropolitan area to define guidelines for antibiotic use.18 The outline specifically does not address issues of diagnostic work-up, decision to hospitalize, or timing of initial antibiotic treatment. We therefore convened a national panel of experts in infectious disease, pharmacology, pulmonology, geriatrics, and nursing to develop comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for management of nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The guidelines address immunization, infection control, timing and thoroughness of nurse and physician evaluation of lower respiratory tract infections, criteria for hospitalization, and criteria for antibiotic spectrum, timing, route, and duration.

Guideline development

Literature review

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken using Ovid (http://www.ovid.com/) and the “explode” version of each of the following key words: nursing homes, long-term care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and pneumonia, to search MEDLINE from 1975 through 2000. Only studies published in English and germane to nursing home residents in the United States and Canada were examined. Results of the search were augmented by a local mulidisciplinary team, consisting of faculty in geriatric studies, infectious disease, pulmonology, and pharmacology at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, an internist who practices exclusively in nursing homes, and a nursing home nurse consultant. This team developed explicit criteria for nursing home-acquired pneumonia processes of care, as described previously.11

Construction of draft guidelines

Working with the explicit criteria developed by the local team, the data from our retrospective study of process of care and survival, and the published literature on nursing home-acquired pneumonia, we drafted an initial set of comprehensive guidelines. We then graded the recommendations according to a standard system for defining quality, with 3 categories for recommendation strength (A, good evidence; B, moderate evidence; C, poor evidence) and 3 grades for quality of evidence (I, at least 1 properly randomized, controlled trial; II, at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies, multiple time series, or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees).19 Published Canadian and American guidelines for treatment of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia formed a template for the antibiotic recommendations.20,21

Modified delphi process

A multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel was recruited from nationally recognized experts in nursing home-acquired pneumonia, geriatric and infectious disease pharmacology, pneumonia treatment guideline development, and nursing home nurses (see Appendix). Panel members received an annotated version of the draft guidelines with a bibliography and the questionnaire described below. A table of the activity spectrum of currently available antibiotics, a table summarizing published reports on the microbiology of nursing home-acquired pneumonia (see Table 1), and tables summarizing our retrospective study of care processes in nursing homes and 30-day survival11were also included in that mailing.

The questionnaire asked whether each proposed guideline was clear, specific, feasible, measurable, and commensurate with his or her usual practice. Panelists were also asked to score each proposed guideline on its importance in determining the outcome of a nursing home-acquired pneumonia episode on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being not important and 5 being extremely important. Suggestions for substantive changes were elicited. The questionnaires were returned 2 weeks before an all-day, face-to-face meeting. For each guideline we calculated the percentage of panelists who agreed that it met each of the 5 criteria outlined. The means and standard deviations of the guideline weights were analyzed. Suggestions for substantive changes in the guidelines were collated and presented in tabular form, along with results of the survey, at the beginning of the meeting.

The most controversial guidelines were found to be classification of symptoms into a diagnosis of probable pneumonia, criteria for hospitalization, evaluation and treatment of residents not being hospitalized, and antibiotic choice. Less controversial were recommendations for immunization and treatment duration. The panel meeting devoted 2 hours to each of the 4 most controversial guidelines. The draft guideline was read and results of the pre-meeting ratings and suggestions were discussed. The guidelines were revised substantially and voted on. A care pathway was also developed at the meeting.

Because revisions were extensive and 1 of the panelists was participating by telephone, a copy of the revised guidelines and care pathway was sent to the panelists for further review and comment after the meeting. At that time, they were asked to rate each guideline on how confident they were that the recommendation should be included as part of the proposed guidelines using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 denoting not confident and 5 denoting very confident. Because the lowest mean confidence rating was 3.4 after this iterative process, no guidelines were dropped from the set agreed upon at the meeting. Final revisions were made to the guidelines and their respective strength-and-quality-of-evidence grades, and approved by the panel.

TABLE 1

Nursing home pneumonia etiology according to studies using verified sputum* or blood culture

| Study | N | Year | Streptococcus pneumoniae (%) | Staphylococcus aureus (%) | Gram-negative rods (%) | Haemophilus influenzae (%) | Anerobes (%) | Multiple organisms (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez3 | 414 | 1988 | 32 | — | 29 | — | — | 22% |

| Peterson4 | 123 | 1988 | 10 | 3 | 21 | 9 | — | — |

| Marrie5 | 131 | 1989 | 16 | 13 | 13 | — | 4 | — |

| Hirata-Davis6 | 50 | 1991 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 10 | — | — |

| Drinka7 | 17 | 1994 | 30 | 6 | — | 25 | — | (Atypicals = 0) |

| Marrie and Blanchard51 | 71 | 1997 | 2/5 | — | 2/5 | — | — | — |

| Pick8 | 257 (98 aspirations) | 1996 | 3 | 38 | 6 | 3 | — | Group B streptococci 43% |

| *Expectorated sputum with > 25 white blood cells per low-power field and < 10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field. | ||||||||

Recommendations

Each of the 25 guidelines is presented below. The strength and quality of evidence rating and panelists’ mean confidence score are shown in parentheses.

Prevention

- Residents should be vaccinated against Streptococcus pneumoniae at admission unless there is documentation of vaccination within 5 years preceding admission or they were allergic to previous pneumococcal vaccine. (A/I/4.7)22-27

- Residents should be vaccinated against influenza by December of each year if they are not allergic to eggs or previous influenza vaccine. Residents admitted between December and March should be vaccinated if not already immunized for the current influenza season, and they are not allergic as described above. (A/I/5.0)27,28

- The nursing facility should provide and strongly recommend immunization against influenza for all employees by December of each year if the employee is not allergic to eggs or previous vaccine. (A/I/4.9)29,30

Initial evaluation of residents with respiratory impairment

Once a resident has been noted to have a significant change in respiratory status, the clinician should use the care pathway outlined in (Figure 1). The panel believed that nurse practitioners and physician assistants with appropriate supervision could substitute for physician care in all pathway activities. Guideline recommendations 4 through 8 address the rapid recognition and physician notification of serious respiratory symptoms:

- Physicians with nursing home residents should be available or have cross-coverage by pager 24 hours/day, 7 days/week. (Absent/Absent/4.8)

- Nursing home staff should page the physician within 1 hour when a resident is noted to have any 2 of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; increased or newly purulent sputum; decline in cognitive, physical, or functional status; fever; hypothermia; dyspnea; tachypnea; chest pain; or new or worsening hypoxemia. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- Nurse evaluation at symptom onset should include, at least, vital signs (temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) and oxygen saturation if a pulse oximeter is available in the facility. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- When notified as in guideline #5, the physician should call back within 1 hour. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- If the nurse does not hear back from the physician within 1 hour, he or she should notify the director of nurses or designee. The nurse and the director of nurses should agree on a plan to notify the medical director or designee and ask him or her to assume care of that episode until the medical director can contact the attending physician. (Absent/Absent/3.5)

Once the physician has been notified, he or she must decide whether pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the reported change.

- The physician and nursing home staff should concur that pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the change noted in guideline #5 above, if the patient has 2 or more of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; newly purulent sputum; fever of 100.5°F or 2°F more than baseline; hypothermia < 96°F; dyspnea; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute; tachycardia; new or worse hypoxemia; pleuritic chest pain; a decline in cognitive or functional status; or new rales or rhonchi on chest examination. Such patients will be referred to in the remainder of the guidelines as having “probable pneumonia.” (C/III/4.1)5,31

FIGURE

Care pathway for nursing home-acquired pneumonia

Venue of care

Once pneumonia is considered likely, the physician must decide whether to hospitalize the resident. Because nursing home-acquired pneumonia is frequently the terminal event of a long and debilitating illness, this decision is especially important.

- The patient’s desire for hospitalization and aggressive care should be assessed directly if possible, or by chart review or discussion with the patient’s health care proxy. Patients with prior orders for no hospitalization or who refuse hospitalization (personally or by proxy) should not be hospitalized. (Absent/Absent/4.8)32

For patients willing to be hospitalized, the panel suggested categorization into 1 of 3 groups: patients whose severity of illness mandates hospitalization; patients whose severity of illness is such that the nursing home’s capacity to deliver acute care should be considered; and patients so stable that treatment in the nursing home is preferable. This set of recommendations is based on 2 retrospective series which suggest that only patients with elevated respiratory rates benefit from hospitalization2 and that patients hospitalized according to criteria similar to these tended to have better survival.11 These recommendations are modeled after Fine’s prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia,33 and take into account the mortality prediction model of Naughton and coworkers34 for nursing home-acquired pneumonia.

- Patients with 2 or more of the following symptoms should be hospitalized (C/III/4.1)2,11:

- If the nursing home cannot provide vital sign assessment every 4 hours, laboratory access, parenteral hydration, and 2 licensed nurses per shift in the facility, serious consideration should be given to hospitalizing patients with any one of the above. (C/III/4.1)11,35,36

- Patients with none of the above should be treated in the nursing home unless the patient or proxy insists on hospitalization. (B/II/4.5)2,11,33,34

Evaluating and monitoring patients who remain in nursing homes

- Nurse evaluation each shift should include, at least, vital signs with measured respiratory rate and oxygen saturation until symptoms resolve. (C/III/4.5)16,17,37

Although a study published by Mehr and colleagues38 after the panel proceedings suggested that patients with multiple signs and symptoms of nursing home-acquired pneumonia are so likely to have an infiltrate on chest x-ray that treating without first obtaining an x-ray may be acceptable, the panel recommended that:

- Patients with probable pneumonia should have a chest x-ray. (C/III/4.2)15,39

- Patients with probable pneumonia should be evaluated in person by the physician, ideally within 24 hours and certainly within 72 hours. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- Because of the issue of antibiotic resistance, and not because of anticipated direct patient benefit, patients for whom antibiotics are ordered should have 1 blood culture drawn if this can be accomplished without delaying initiation of antibiotics longer than 1 hour. (C/III/3.4)37,40

The panel did not recommend sputum Gram’s stain and culture even though 2 recent guidelines on evaluating infection in long-term care facilities did.15,16 Obtaining high-quality sputa in this population is notoriously difficult.1

TABLE 2

Key recommendations of evidence

| Guideline | Strength/quality of evidence |

|---|---|

| 1, 2, 3: Vaccinate staff and residents against influenza and residents against Streptococcus pneumoniae. | A/I |

| 4, 5, 6, 7, 8: Nursing assessment of change in condition should include a full set of vital signs with oxygen saturation. Initial communication with the physician should be completed within 2 hours of symptom onset. | Absent |

| 9: Probable pneumonia is defined as 2 or more of the following: new or worsening cough; newly purulent sputum; temperature > 100.5°F, < 96°F, or 2°F more than baseline; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute, tachycardia; new or worsening hypoxia; pleuritic chest pain; decline in cognitive or functional status; physical findings on chest examination such as rales or rhonchi. | C/III |

| 10: Patient’s desire for hospitalization and aggressive care should be assessed at the onset of the episode and directly with the patient, if possible. | Absent |

| 11, 12, 13: The decision to hospitalize should be based on a combination of vital sign criteria, active comorbidity, and nursing home capabilities. | C/III |

| 23: The antibiotic chosen as empiric therapy should cover S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, common gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus. | B/II |

| 25: Use oral antibiotics if the patient can take oral medication. | A/I |

| Recommendations were graded according to a standard system,19with 3 categories for recommendation strength (A, good evidence; B, moderate evidence; C, poor evidence) and 3 grades for quality of evidence (I, at least 1 properly randomized, controlled trial; II, at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies, multiple time series, or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees). | |

Antibiotic use

Extrapolating from studies of hospital- and community-acquired pneumonia indicating a survival benefit for patients who receive antibiotics within 8 hours of arrival in hospital or symptom onset,40 the panel made the following recommendations, which do not conflict with 3 recently published guidelines on use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities.16

- Patients being sent immediately to the hospital should receive 1 dose of parenteral antibiotics prior to leaving the nursing home unless this treatment would delay transport for more than 1 hour. The hospital should be notified of the antibiotic given. (B/II/4.4)40

- A single dose of antibiotics should be ordered immediately (simultaneously with the chest x-ray order) if the patient has any of the following: systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or 20 mm Hg less than baseline; oxygen saturation < 90% on room air at sea level; pulse > 130 beats per minute; respiratory rate > 30 breaths per minute; or temperature > 101.5°F. (B/II/4.5)40,41

- For patients with probable pneumonia who are stable (oxygen saturation > 90%, systolic blood pressure > 90 mm Hg, pulse < 120 beats per minute, and respiratory rate < 30 beats per minute), a decision to use antibiotics may await results of the chest x-ray if they will be available within 24 hours. (C/III/3.8)40,41 If the chest x-ray does not confirm the suspicion of pneumonia, consideration should be given to stopping antibiotic treatment.

- Antibiotics, if ordered, should be delivered to the patient within 4 hours of the orders being given by the physician. (B/II/4.5)40,41

- If the patient is able to take oral medication, that route is preferred, except that patients being sent to the hospital should have 1 parenteral dose. (A/I/4.7)4,42,43

Because it is difficult to obtain a bacteriologic diagnosis in most nursing home residents, the initial choice of antibiotic must be empiric. Based on the published studies of nursing home-acquired pneumonia bacteriology, half of which used high-quality sputum samples (> 25 white blood cells per low-power field and < 10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field, (see Table 1), the panel recommended a broad-spectrum antibiotic covering S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus. In areas or facilities where resistance of S pneumoniae to penicillin is known to be high, treatment should be modified accordingly. These recommendations differ from those proposed by the Society of Health Care Epidemiology of America in their 2000 position paper,16 but are similar to those proposed by Naughton and Mylotte18 in their guideline derived from current community practice in Buffalo, New York, except that the current panel recommends the addition of a macrolide. These differences are driven by controversy over the relative importance of gram-negative rods as etiologic vs colonizing organisms in nursing home-acquired pneumonia; the relative importance of atypical organisms; and by the current panel’s concern that an important percentage of bacteria in long-term care facilities may already be resistant to many of the antibiotics endorsed by the Society of Health Care Epidemiology of America. Moreover, 3 studies have suggested a survival benefit of broader-spectrum empiric treatment in nursing home-acquired pneumonia.11,44,45

- The antibiotic chosen as empiric therapy needs to cover S pneumoniae, H influenzae, gram-neg-ative rods, and S aureus. (B/II/4.5)37,31,39,44-51

- Currently acceptable choices for empiric treatment include: antipneumococcal quinolones or an extended-spectrum beta-lactam plus a macrolide other than erythromycin. (C/III/4.5)45,52,53

- Treat for 10 to 14 days. (B/II/4.4)18,25

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel of nationally recognized experts in nursing home-acquired pneumonia achieved consensus in proposing guidelines and a care pathway to prevent, recognize, evaluate, and treat nursing home-acquired pneumonia. For immunization and use of oral antibiotics when possible, evidence was sufficient to make a strong (A/I) recommendation. Even in areas in which evidence was lacking, the panel agreed readily. Thus for most of the 25 proposed guidelines, strong evidence and/or ready consensus existed among national experts from many disciplines.

The process of guideline development that we followed was systematic and meticulous. The panel was diverse, including nurses and pharmacologists, nationally recognized experts in infectious disease, nursing home care, geriatrics, and pulmonology. The breadth of the panel’s collective experience, and the rigor of the Delphi process we followed, lend face validity to the proposed guidelines despite some differences with other guidelines, as noted above.45,53

These guidelines are uniquely comprehensive. They address management of pneumonia from prevention through diagnosis, the decision to hospitalize, and treatment. Such a comprehensive approach is essential given the many people and systems that interact in the care of nursing home residents, a uniquely frail and vulnerable population. Evidence from our work and others11,13 suggests that only a comprehensive approach will, over time, improve the outcome of this important illness.

The guidelines have 2 important limitations. They have not yet been approved by any official professional society, nor have they been tested prospectively. Prospective testing is required to validate whether, in fact, the proposed guidelines can be implemented and, if implemented, they will improve mortality, function, cost of care, rehospitalization rates, and community discharge rates. We chose not to seek official approval of the guidelines until they can be proven effective.

We believe the proposed guidelines can and should be used to the fullest extent possible by nursing homes and physicians who practice there, because the combination of evidence and consensus is strong. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia causes excess mortality and functional loss. The proposed guidelines, based as they are in empiric evidence, common sense, and expert consensus, offer some hope of decreasing rehospitalization and cost, mitigating functional decline, and improving survival.

APPENDIX: PANEL MEMBERS . Diana Blake, RN, Western Hills Health Care Center, Lakewood, CO; JoAnn G. Congdon, RN, PhD, University of Colorado HSC, Denver, CO; Douglas Fish, PharmD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Evelyn Hutt, MD, University of Colorado HSC, Denver, CO; Denise Iskra, RN, Life Care of Westminster, Westminster, CO; Andrew M. Kramer, MD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Thomas J. Marrie, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Mark Loeb, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Wayne C. McCormick, MD, MPH, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA; Annette M. Medina-Walpole, MD, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; David R. Mehr, MD, MS, University of Missouri–Columbia, Columbia, MO; Michael S. Niederman, MD, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Mineola, NY; Phillip K. Peterson, MD, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; J. Mark Ruscin, PharmD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Thomas T. Yoshikawa, MD, Charles Drew University, Los Angeles, CA.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of the panel for their thoughtful participation and willingness to review multiple drafts of the guidelines and manuscript; Steven Teutsch, MD, Senior Director, Outcomes Research and Management, Merck & Co., Inc., for his support and advice; Lisa Lampinen for manuscript preparation; and Merck & Co., Inc., for funding.

—William Osler, ca 1900

We convened a multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel to develop comprehensive evidence and consensus-based guidelines for managing nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The panel began with explicit criteria for process of care quality measures, performed a comprehensive review of the English-language literature, evaluated the quality of the evidence, and drafted a set of proposed guidelines. The panel reviewed the draft, an annotated bibliography, and data from a study of 30-day survival from nursing home-acquired pneumonia, and then participated in an all-day meeting in January 2001. Using a modified Delphi process, the panel refined the guidelines and developed a care pathway. The guidelines recommend a comprehensive approach, including immunization of staff and residents, and communication between nursing staff and the attending physician within 2 hours of symptom onset. Probable pneumonia was defined. An algorithm was delineated for assessing the patient’s wishes for hospitalization and aggressive care, and deciding on hospitalization based on the severity of the illness as well as the capacity of the nursing home to provide acute care. The timing and extent of evaluation in a nursing home relative to the rapid initiation of antibiotics should depend on whether the patient has any unstable vital signs. An antibiotic covering Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, common gram-negative rods, and Staphylococcus aureus should be given for 10 to 14 days, orally if the patient is able to take medications by mouth.

Mortality from nursing home-acquired pneumonia is as high as 44%,1and nearly a third of those who survive suffer significant functional decline.2 Nursing home-acquired pneumonia is an entity distinct from community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly and nosocomial pneumonia. Older adults in nursing homes are more likely than community-dwelling older persons, but less likely than hospitalized elderly patients, to be colonized with gram-negative rods and pathogens with multiple antibiotic resistance.3-8Inappropriate use of antibiotics in long-term care facilities contributes significantly to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance generally.9 In addition, most nursing home residents are cognitively impaired, immunocompromised, have multiple functional deficits, or have dysphagia, which further contributes to their vulnerability.10

In recent work11 with a national nursing home sample, we showed that high quality care, including appropriate antibiotic use, hospitalization when indicated, and rapid identification of and response to respiratory symptoms, is associated with improved survival of residents who acquire pneumonia. Unfortunately, we also found that many of the 58 nursing homes in our study provided less than adequate care; for example, only 31% of residents received antibiotics within one 8-hour shift of symptom onset.11

Convincing evidence indicates that treatment guidelines improve pneumonia outcomes in acute care settings,12,13 and preliminary indications suggest that they may have a positive impact on processes of care in nursing facilities.14 Three guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of infections in nursing homes have been published in the last 2 years,15-17but these guidelines are not specific to pneumonia. The only guideline specific to nursing home-acquired pneumonia used current community practice in 1 metropolitan area to define guidelines for antibiotic use.18 The outline specifically does not address issues of diagnostic work-up, decision to hospitalize, or timing of initial antibiotic treatment. We therefore convened a national panel of experts in infectious disease, pharmacology, pulmonology, geriatrics, and nursing to develop comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for management of nursing home-acquired pneumonia. The guidelines address immunization, infection control, timing and thoroughness of nurse and physician evaluation of lower respiratory tract infections, criteria for hospitalization, and criteria for antibiotic spectrum, timing, route, and duration.

Guideline development

Literature review

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken using Ovid (http://www.ovid.com/) and the “explode” version of each of the following key words: nursing homes, long-term care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and pneumonia, to search MEDLINE from 1975 through 2000. Only studies published in English and germane to nursing home residents in the United States and Canada were examined. Results of the search were augmented by a local mulidisciplinary team, consisting of faculty in geriatric studies, infectious disease, pulmonology, and pharmacology at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, an internist who practices exclusively in nursing homes, and a nursing home nurse consultant. This team developed explicit criteria for nursing home-acquired pneumonia processes of care, as described previously.11

Construction of draft guidelines

Working with the explicit criteria developed by the local team, the data from our retrospective study of process of care and survival, and the published literature on nursing home-acquired pneumonia, we drafted an initial set of comprehensive guidelines. We then graded the recommendations according to a standard system for defining quality, with 3 categories for recommendation strength (A, good evidence; B, moderate evidence; C, poor evidence) and 3 grades for quality of evidence (I, at least 1 properly randomized, controlled trial; II, at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies, multiple time series, or dramatic results in uncontrolled experiments; III, opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees).19 Published Canadian and American guidelines for treatment of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia formed a template for the antibiotic recommendations.20,21

Modified delphi process

A multidisciplinary, multispecialty panel was recruited from nationally recognized experts in nursing home-acquired pneumonia, geriatric and infectious disease pharmacology, pneumonia treatment guideline development, and nursing home nurses (see Appendix). Panel members received an annotated version of the draft guidelines with a bibliography and the questionnaire described below. A table of the activity spectrum of currently available antibiotics, a table summarizing published reports on the microbiology of nursing home-acquired pneumonia (see Table 1), and tables summarizing our retrospective study of care processes in nursing homes and 30-day survival11were also included in that mailing.

The questionnaire asked whether each proposed guideline was clear, specific, feasible, measurable, and commensurate with his or her usual practice. Panelists were also asked to score each proposed guideline on its importance in determining the outcome of a nursing home-acquired pneumonia episode on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being not important and 5 being extremely important. Suggestions for substantive changes were elicited. The questionnaires were returned 2 weeks before an all-day, face-to-face meeting. For each guideline we calculated the percentage of panelists who agreed that it met each of the 5 criteria outlined. The means and standard deviations of the guideline weights were analyzed. Suggestions for substantive changes in the guidelines were collated and presented in tabular form, along with results of the survey, at the beginning of the meeting.

The most controversial guidelines were found to be classification of symptoms into a diagnosis of probable pneumonia, criteria for hospitalization, evaluation and treatment of residents not being hospitalized, and antibiotic choice. Less controversial were recommendations for immunization and treatment duration. The panel meeting devoted 2 hours to each of the 4 most controversial guidelines. The draft guideline was read and results of the pre-meeting ratings and suggestions were discussed. The guidelines were revised substantially and voted on. A care pathway was also developed at the meeting.

Because revisions were extensive and 1 of the panelists was participating by telephone, a copy of the revised guidelines and care pathway was sent to the panelists for further review and comment after the meeting. At that time, they were asked to rate each guideline on how confident they were that the recommendation should be included as part of the proposed guidelines using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 denoting not confident and 5 denoting very confident. Because the lowest mean confidence rating was 3.4 after this iterative process, no guidelines were dropped from the set agreed upon at the meeting. Final revisions were made to the guidelines and their respective strength-and-quality-of-evidence grades, and approved by the panel.

TABLE 1

Nursing home pneumonia etiology according to studies using verified sputum* or blood culture

| Study | N | Year | Streptococcus pneumoniae (%) | Staphylococcus aureus (%) | Gram-negative rods (%) | Haemophilus influenzae (%) | Anerobes (%) | Multiple organisms (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez3 | 414 | 1988 | 32 | — | 29 | — | — | 22% |

| Peterson4 | 123 | 1988 | 10 | 3 | 21 | 9 | — | — |

| Marrie5 | 131 | 1989 | 16 | 13 | 13 | — | 4 | — |

| Hirata-Davis6 | 50 | 1991 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 10 | — | — |

| Drinka7 | 17 | 1994 | 30 | 6 | — | 25 | — | (Atypicals = 0) |

| Marrie and Blanchard51 | 71 | 1997 | 2/5 | — | 2/5 | — | — | — |

| Pick8 | 257 (98 aspirations) | 1996 | 3 | 38 | 6 | 3 | — | Group B streptococci 43% |

| *Expectorated sputum with > 25 white blood cells per low-power field and < 10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field. | ||||||||

Recommendations

Each of the 25 guidelines is presented below. The strength and quality of evidence rating and panelists’ mean confidence score are shown in parentheses.

Prevention

- Residents should be vaccinated against Streptococcus pneumoniae at admission unless there is documentation of vaccination within 5 years preceding admission or they were allergic to previous pneumococcal vaccine. (A/I/4.7)22-27

- Residents should be vaccinated against influenza by December of each year if they are not allergic to eggs or previous influenza vaccine. Residents admitted between December and March should be vaccinated if not already immunized for the current influenza season, and they are not allergic as described above. (A/I/5.0)27,28

- The nursing facility should provide and strongly recommend immunization against influenza for all employees by December of each year if the employee is not allergic to eggs or previous vaccine. (A/I/4.9)29,30

Initial evaluation of residents with respiratory impairment

Once a resident has been noted to have a significant change in respiratory status, the clinician should use the care pathway outlined in (Figure 1). The panel believed that nurse practitioners and physician assistants with appropriate supervision could substitute for physician care in all pathway activities. Guideline recommendations 4 through 8 address the rapid recognition and physician notification of serious respiratory symptoms:

- Physicians with nursing home residents should be available or have cross-coverage by pager 24 hours/day, 7 days/week. (Absent/Absent/4.8)

- Nursing home staff should page the physician within 1 hour when a resident is noted to have any 2 of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; increased or newly purulent sputum; decline in cognitive, physical, or functional status; fever; hypothermia; dyspnea; tachypnea; chest pain; or new or worsening hypoxemia. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- Nurse evaluation at symptom onset should include, at least, vital signs (temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) and oxygen saturation if a pulse oximeter is available in the facility. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- When notified as in guideline #5, the physician should call back within 1 hour. (Absent/Absent/4.3)

- If the nurse does not hear back from the physician within 1 hour, he or she should notify the director of nurses or designee. The nurse and the director of nurses should agree on a plan to notify the medical director or designee and ask him or her to assume care of that episode until the medical director can contact the attending physician. (Absent/Absent/3.5)

Once the physician has been notified, he or she must decide whether pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the reported change.

- The physician and nursing home staff should concur that pneumonia is a leading consideration in the diagnosis of the change noted in guideline #5 above, if the patient has 2 or more of the following signs or symptoms: new or worsening cough; newly purulent sputum; fever of 100.5°F or 2°F more than baseline; hypothermia < 96°F; dyspnea; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute; tachycardia; new or worse hypoxemia; pleuritic chest pain; a decline in cognitive or functional status; or new rales or rhonchi on chest examination. Such patients will be referred to in the remainder of the guidelines as having “probable pneumonia.” (C/III/4.1)5,31

FIGURE

Care pathway for nursing home-acquired pneumonia

Venue of care

Once pneumonia is considered likely, the physician must decide whether to hospitalize the resident. Because nursing home-acquired pneumonia is frequently the terminal event of a long and debilitating illness, this decision is especially important.

- The patient’s desire for hospitalization and aggressive care should be assessed directly if possible, or by chart review or discussion with the patient’s health care proxy. Patients with prior orders for no hospitalization or who refuse hospitalization (personally or by proxy) should not be hospitalized. (Absent/Absent/4.8)32

For patients willing to be hospitalized, the panel suggested categorization into 1 of 3 groups: patients whose severity of illness mandates hospitalization; patients whose severity of illness is such that the nursing home’s capacity to deliver acute care should be considered; and patients so stable that treatment in the nursing home is preferable. This set of recommendations is based on 2 retrospective series which suggest that only patients with elevated respiratory rates benefit from hospitalization2 and that patients hospitalized according to criteria similar to these tended to have better survival.11 These recommendations are modeled after Fine’s prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia,33 and take into account the mortality prediction model of Naughton and coworkers34 for nursing home-acquired pneumonia.

- Patients with 2 or more of the following symptoms should be hospitalized (C/III/4.1)2,11:

- If the nursing home cannot provide vital sign assessment every 4 hours, laboratory access, parenteral hydration, and 2 licensed nurses per shift in the facility, serious consideration should be given to hospitalizing patients with any one of the above. (C/III/4.1)11,35,36

- Patients with none of the above should be treated in the nursing home unless the patient or proxy insists on hospitalization. (B/II/4.5)2,11,33,34

Evaluating and monitoring patients who remain in nursing homes

- Nurse evaluation each shift should include, at least, vital signs with measured respiratory rate and oxygen saturation until symptoms resolve. (C/III/4.5)16,17,37

Although a study published by Mehr and colleagues38 after the panel proceedings suggested that patients with multiple signs and symptoms of nursing home-acquired pneumonia are so likely to have an infiltrate on chest x-ray that treating without first obtaining an x-ray may be acceptable, the panel recommended that:

- Patients with probable pneumonia should have a chest x-ray. (C/III/4.2)15,39

- Patients with probable pneumonia should be evaluated in person by the physician, ideally within 24 hours and certainly within 72 hours. (Absent/Absent/4.5)

- Because of the issue of antibiotic resistance, and not because of anticipated direct patient benefit, patients for whom antibiotics are ordered should have 1 blood culture drawn if this can be accomplished without delaying initiation of antibiotics longer than 1 hour. (C/III/3.4)37,40

The panel did not recommend sputum Gram’s stain and culture even though 2 recent guidelines on evaluating infection in long-term care facilities did.15,16 Obtaining high-quality sputa in this population is notoriously difficult.1

TABLE 2