User login

Frequently Hospitalized Patients’ Perceptions of Factors Contributing to High Hospital Use

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

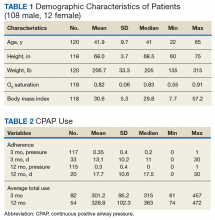

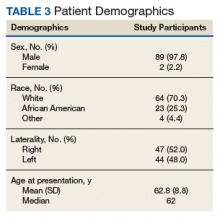

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

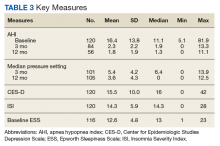

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

In recent years, hospitals have made considerable efforts to improve transitions of care, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP).1 Initially focusing on three medical conditions, the HRRP has been associated with significant reductions in readmission rates.2 Importantly, a small proportion of patients accounts for a very large proportion of hospital readmissions and hospital use.3,4 Frequently hospitalized patients often have multiple chronic conditions and unique needs which may not be met by conventional approaches to healthcare delivery, including those influenced by the HRRP.4-6 In light of this challenge, some hospitals have developed programs specifically focused on frequently hospitalized patients. A recent systematic review of these programs found relatively few studies of high quality, providing only limited insight in designing interventions to support this population.7 Moreover, no studies appear to have incorporated the patients’ perspectives into the design or adaptation of the model. Members of our research team developed and implemented the Complex High Admission Management Program (CHAMP) in January 2016 to address the needs of frequently hospitalized patients in our hospital. To enhance CHAMP and inform the design of programs serving similar populations in other health systems, we sought to identify factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Our research question was, from the patients’ perspective, what factors contribute to patients’ becoming and continuing to be high users of hospital care.

METHODS

Setting, Study Design, and Participants

This qualitative study took place at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), an 894-bed urban academic hospital located in Chicago, Illinois. Between December 2016 and September 2017, we recruited adult patients admitted to the general medicine services. Eligible participants were identified with the assistance of a daily Northwestern Medicine Electronic Data Warehouse (EDW) search and included patients with two unplanned 30-day inpatient readmissions to NMH within the prior 12 months, in addition to one or more of the following criteria: (1) at least one readmission in the last six months; (2) a referral from one of the patient’s medical providers; or (3) at least three observation visits. We excluded patients whose preferred language was not English and those disoriented to person, place, or time. Considering NMH data showing that approximately one-third of high-utilizer patients have sickle cell disease, we used purposive sampling with the goal to compare findings within and between two groups of participants; those with and those without sickle cell disease. Our study was deemed exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Enrollment and Data Collection

We created an interview guide based on the research team’s experience with this population, a literature review, and our research question (See Appendix).8,9 A research coordinator approached eligible participants during their hospital stay. The coordinator explained the study to eligible participants and obtained verbal consent for participation. The research coordinator then conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were audio recorded for subsequent transcription and coding. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time.

Analysis

Digital audio recordings from interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified, and analyzed using an iterative inductive team-based approach to coding.10 In our first cycle coding, all coders (KJO, SF, MMC, LO, KAC) independently reviewed and coded three transcripts using descriptive coding and subcoding to generate a preliminary codebook with code definitions.10,11 Following the meetings to compare and compile our initial coding, each researcher then independently recoded the three transcripts with the developed codebook. The researchers met again to triangulate perspectives and reach a consensus on the final codebook. Using multiple coders is a standard process to control for subjective bias that one coder could bring to the coding process.12 Following this meeting, the coders split into two teams of two (KJO, SF, and MMC, LO) to complete the coding of the remaining transcripts. Each team member independently coded the assigned transcripts and reconciled their codes with their counterpart; any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Using this strategy, every transcript was coded by at least two team members. Our second coding cycle utilized pattern coding and involved identifying consistency both within and between transcripts; discovering associations between codes.10,11,13 Constant comparison was used to compare responses among all participants, as well as between sickle-cell and nonsickle-cell participants.13,14 Following team coding and reconciling, the analyses were presented to a broader research team for additional feedback and critique. All analyses were conducted using Dedoose version 8.0.35 (Los Angeles, California). Participant recruitment, interviews, and analysis of the transcripts continued until no new codes emerged and thematic saturation was achieved.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Overall, we invited 34 patients to be interviewed; 26 consented and completed interviews (76.5%). Six (17.6%) patients declined participation, one (2.9%) was unable to complete the interview before hospital discharge, and one (2.9%) was excluded due to disorientation. Demographic characteristics of the 26 participants are shown in Table 1.

Four main themes emerged from our analysis. Table 2 summarizes these themes, subthemes, and provides representative quotes.

Major Medical Problem(s) are Universal, but High Hospital Use Varies in Onset

Not surprisingly, all participants described having at least one major medical problem. Some participants, such as those with genetic disorders, had experienced periods of high hospital use throughout their entire lifetime, while other participants experienced an onset of high hospital use as an adult after being previously healthy. Though most participants with genetic disorders had sickle cell anemia; one had a rare genetic disorder which caused chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants typically described having a significant medical condition as well as other medical problems or complications from past surgery. Some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until a complication or other medical problem arose, suggesting these new issues pushed them over a threshold beyond which self-management at home was less successful.

Course Fluctuates over Time and is Related to Psychological, Social, and Economic Factors

Participants identified psychological stress, social support, and financial constraints as factors which influence the course of their illness over time. Deaths in the family, breakups, and concerns about other family members were mentioned as specific forms of psychological stress and directly linked by participants to worsening of symptoms. Social support was present for most, but not all, participants, with no appreciable difference based on whether the participant had sickle cell disease. Social support was generally perceived as helpful, and several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others. Financial pressures also served as stressors and often impeded care due to lack of access to medications, other treatments, and housing.

Onset and Progression of Episodes Vary, but Generally Seem Uncontrollable

Regarding the onset of illness episodes, some participants described the sudden, unpredictable onset of symptoms, others described a more gradual onset which allowed them to attempt self-management. Regardless of the timing, episodes of illness were often perceived as spontaneous or triggered by factors outside of the participant’s control. Several participants, especially those with sickle cell disease, mentioned a relationship between their symptoms and the weather. Participants also noted the inconsistency in factors which may trigger an episode (ie, sometimes the factor exacerbated symptoms, while other times it did not). Participants also described having a high symptom burden with significant limitations in activities of daily living during episodes of illness. Pain was a very common component of symptoms regardless of whether or not the participant had sickle cell disease.

Individuals Seek Care after Self-Management Fails and Prefer to Avoid Hospitalization

Participants tried to control their symptoms with medications and typically sought care only when it was clear that this approach was not working, or they ran out of medications. This finding was consistent across both groups of participants (ie, those with and those without sickle cell disease). Many participants described very strong preferences not to come to the hospital; no participant described being in the hospital as a favorable or positive experience. Some participants mentioned that they had spent major holidays in the hospital and that they missed their family. No participant had a desire to come to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

In this study of frequently hospitalized patients, we found four major themes that illuminate patient perspectives about factors that contribute to high hospital use. While some of our findings corroborate those of previous studies, other emerging patterns were novel. Herein, we summarize key findings, provide context, and describe implications for the design of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Similar to the findings of previous quantitative research, participants in our study described having a significant medical condition and typically had multiple medical conditions or complications.4-6 Importantly, some participants described having a major medical problem which did not require frequent hospitalization until another medical problem or complication arose. This finding suggests that there may be an opportunity to identify patients with significant medical problems who are at elevated risk before the onset of high hospital use. Early identification of these high-risk patients could allow for the provision of additional support to prevent potential complications or address other factors which may contribute to the need for frequent hospitalization.

Participants in our study directly linked psychological stress to fluctuations in their course of illness. Previous research by Mautner and colleagues queried participants about childhood experiences and early life stressors and reported that early life instabilities and traumas were prevalent among patients with high levels of emergency and hospital-based healthcare utilization.15 Our participants identified more recent traumatic events (eg, the death of a loved one and breakups) when reflecting on factors contributing to illness exacerbations; early life trauma did not emerge as an identified contributor. Of note, unlike Mautner et al., we did not ask participants to reflect on childhood determinants of disease and illness specifically. Our findings suggest that psychological stress contributes to illness exacerbation, even for those patients without other significant psychiatric conditions (eg, depressive disorder, schizophrenia). Incorporating mental health professionals into programs for this patient population may improve health by teaching specific coping strategies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for an acute stress disorder.16,17

Social support was also a factor related to illness fluctuations over time. Notably, several participants indicated a benefit to their own health when providing social support to others, suggesting a role for peer support that may be reciprocally beneficial. This approach is supported by the literature. Williams and colleagues found that patients with sickle cell anemia experienced symptom improvement with peer support;18 while Johnson and colleagues recently reported a reduction in readmissions to acute care with the use of peer support for patients with severe mental illness.19

Financial constraints impeded care for some patients and served as a barrier to accessing medications, other treatments, and housing. Similar to the findings of prior quantitative research, our frequently hospitalized patients had a high proportion of patients with Medicaid and low proportion with private insurance, suggesting low socioeconomic status.9,20 We did not formally collect data on income or economic status. Interestingly, prior qualitative studies have not identified financial constraints as a major theme, though this may be explained by differences in study populations and the overall objectives of the studies.15,21 Importantly, the overwhelming majority of programs for frequently hospitalized patients identified in a recent systematic review included social workers.7 Our findings support the need to address financial constraints and the use of social workers in models of care for frequently hospitalized patients.

Many participants in our study felt that the factors contributing to exacerbations of illness were either inconsistent in their effect or out of their control. These findings have similarities to those from a qualitative study by Liu and colleagues in which they interviewed 20 “hospital-dependent” patients over 65 years of age.21 Though not explicitly focused on factors contributing to exacerbations, participants in their study felt that hospitalizations were generally inevitable. In our study, participants with sickle cell disease often identified changes in the weather as contributing to illness exacerbations. The relationship between weather and sickle cell disease remains incompletely understood, with an inconsistent association found in prior studies.22

Participants in our study strongly desired to avoid hospitalization and typically sought hospital care when symptoms could not be controlled at home. This finding is in contrast to that from the study by Liu and colleagues where they found that hospital-dependent patients over 65 years had favorable perspectives of hospitalization because they felt safer and more secure in the hospital.21 Our participants were younger than those from the study by Liu and colleagues, had a high symptom burden, and may have been more concerned about control of those symptoms than the risk for clinical deterioration. Programs should aim to strengthen their support of patients’ self-management efforts early in the episode of illness and potentially offer home visits or a day hospital to avoid hospitalization. A recent systematic review found evidence that alternatives to inpatient care (eg, hospital-at-home) for low risk medical patients can achieve comparable outcomes at lower costs.23 Similarly, some health systems have implemented day hospitals to treat low risk patients with uncomplicated sickle cell pain.24,25

The heavy symptom burden experienced by participants in our study is notable. Pain was especially common. Programs may wish to partner with palliative care and addiction specialists to balance symptom relief with the simultaneous need to address comorbid substance and opioid use disorders when they are present.4,9

Our study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from the medicine service at a single academic hospital using criteria we developed to identify frequently hospitalized patients. Populations differ across hospitals and definitions of frequently hospitalized patients vary, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we excluded patients whose preferred language was not English, as well as those disoriented to person, place, or time. It is possible that factors contributing to high hospital use differ for non-English speaking patients and those with cognitive deficits.

CONCLUSION

In this qualitative study, we identified factors associated with the onset and continuation of high hospital use. Emergent themes pointed to factors which influence patients’ onset of high hospital use, fluctuations in their illness over time, and triggers to seek care during an illness episode. These findings represent an important contribution to the literature because they allow patients’ perspectives to be incorporated into the design and adaptation of programs serving similar populations in other health systems. Programs that integrate patients’ perspectives into their design are likely to be better prepared to address patients’ needs and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and willingness to share their stories. The authors also thank Claire A. Knoten PhD and Erin Lambers PhD, former research team members who helped in the initial stages of the study.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was funded by Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the Northwestern Medical Group.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 17, 2018.

2. Wasfy JH, Zigler CM, Choirat C, Wang Y, Dominici F, Yeh RW. Readmission rates after passage of the hospital readmissions reduction program: a pre-post analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;166(5):324-331. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0185.

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients-an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1608511.

4. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2375.

5. Dastidar JG, Jiang M. Characterization, categorization, and 5-year mortality of medicine high utilizer inpatients. J Palliat Care. 2018;33(3):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0825859718769095.

6. Mudge AM, Kasper K, Clair A, et al. Recurrent readmissions in medical patients: a prospective study. J Hosp Med. 2010;6(2):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.811.

7. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, Odwyer LC, Nichols N, Oleary KJ. Interventions for frequently hospitalized patients and their effect on outcomes: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):853-859. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3090.

8. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273-1302. PubMed

9. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000000628.

10. Miles MB, Huberman M, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2014.

11. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE publications; 2013.

12. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1 ed. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE Publications; 1985.

13. Kolb SM. Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: valid research strategies for educators. J Emerging Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 2012;3(1):83-86.

14. Glasser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2017.

15. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26-S33. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2013.0033.

16. Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM, Powers MB, Smits JAJ, Hofmann SG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depres Anxiety. 2018;35(6):502-514. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728.

17. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple-session early interventions following traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):293-301. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040590.

18. Williams H, Tanabe P. Sickle cell disease: a review of nonpharmacological approaches for pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):163-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.017.

19. Johnson S, Lamb D, Marston L, et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):409-418.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31470-3.

20. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2351.

21. Liu T, Kiwak E, Tinetti ME. Perceptions of hospital-dependent patients on their needs for hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):450-453. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2756.

22. Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC. Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1561-1573. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1510865.

23. Conley J, O’Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693-1702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974.

24. Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):854-855. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.10757.

25. Benjamin LJ, Swinson GI, Nagel RL. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: an approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood. 2000;95(4):1130-1136. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

An Advanced Practice Provider Clinical Fellowship as a Pipeline to Staffing a Hospitalist Program

There is an increasing utilization of advanced practice providers (APPs) in the delivery of healthcare in the United States.1,2 As of 2016, there were 157, 025 nurse practitioners (NPs) and 102,084 physician assistants (PAs) with a projected growth rate of 6.8% and 4.3%, respectively, which exceeds the physician growth rate of 1.1%.2 This increased growth rate has been attributed to the expectation that APPs can enhance the quality of physician care, relieve physician shortages, and reduce service costs, as APPs are less expensive to hire than physicians.3,4 Hospital medicine is the fastest growing medical field in the United States, and approximately 83% of hospitalist groups around the country utilize APPs; however, the demand for hospitalists continues to exceed the supply, and this has led to increased utilization of APPs in hospital medicine.5-10

APPs receive very limited inpatient training and there is wide variation in their clinical abilities after graduation.11 This is an issue that has become exacerbated in recent years by a change in the training process for PAs. Before 2005, PA programs were typically two to three years long and required the same prerequisite courses as medical schools.11 PA students completed more than 2,000 hours of clinical rotations and then had to pass the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam before they could practice.12 Traditionally, PA programs typically attracted students with prior healthcare experience.11 In 2005, PA programs began transitioning from bachelor’s degrees to requiring a master’s level degree for completion of the programs. This has shifted the demographics of the students matriculating to younger students with little-to-no prior healthcare experience; moreover, these fresh graduates lack exposure to hospital medicine.11

NPs usually gain clinical experience working as registered nurses (RNs) for two or more years prior to entry into the NP program. NP programs for baccalaureate-prepared RNs vary in length from two to three years.2 There is an acute care focus for NPs in training; however, there is no standardized training or licensure to ensure that hospital medicine competencies are met.13-15 Some studies have shown that a lack of structured support has been found to affect NP role transition negatively during the first year of practice,16 and graduating NPs have indicated that they needed more out of their clinical education in terms of content, clinical experience, and competency testing.17

Hiring new APP graduates as hospitalists requires a longer and more rigorous onboarding process. On‐the‐job training in hospital medicine for new APP graduates can take as long as six to 12 months in order for them to acquire the basic skill set necessary to adequately manage hospitalized patients.15 This extended onboarding is costly because the APPs are receiving a full hospitalist salary, yet they are not functioning at full capacity. Ideally, there should be an intermediary training step between graduation and employment as hospitalist APPs. Studies have shown that APPs are interested in formal postgraduate hospital medicine training, even if it means having a lower stipend during the first year after graduating from their NP or PA program.9,15,18

The growing need for hospitalists, driven by residency work-hour reform, increased age and complexity of patients, and the need to improve the quality of inpatient care while simultaneously reducing waste, has contributed to the increasing utilization of and need for highly qualified APPs in hospital medicine.11,19,20 We established a fellowship to train APPs. The goal of this study was to determine if an APP fellowship is a cost-effective pipeline for filling vacancies within a hospitalist program.

METHODS

Design and Setting

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (JHBMC) is a 440 bed hospital in Baltimore Maryland. The hospitalist group was started in 1996 with one physician seeing approximately 500 discharges a year. Over the last 20 years, the group has grown and is now its own division with 57 providers, including 42 physicians, 11 APPs, and four APP fellows. The hospitalist division manages ~7,000 discharges a year, which corresponds to approximately 60% of admissions to general medicine. Hospitalist APPs help staff general medicine by working alongside doctors and admitting patients during the day and night. The APPs also staff the pulmonary step down unit with a pulmonary attending and the chemical dependency unit with an internal medicine addiction specialist.

The growth of the division of hospital medicine at JHBMC is a result of increasing volumes and reduced residency duty hours. The increasing full time equivalents (FTEs) resulted in a need for APPs; however, vacancies went unfilled for an average of 35 weeks due to the time it took to post open positions, interview applicants, and hire applicants through the credentialing process. Further, it took as long as 22 to 34 weeks for a new hire to work independently. The APP vacancies and onboarding resulted in increased costs to the division incurred by physician moonlighting to cover open shifts. The hourly physician moonlighting rate at JHBMC is $150. All costs were calculated on the basis of a 40-hour work week. We performed a pre- and postanalysis of outcomes of interest between January 2009 and June 2018. This study was exempt from institutional review board review.

Intervention

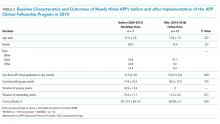

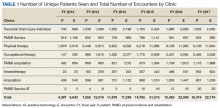

In 2014, a one year APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine was started. The fellows evaluate and manage patients working one-on-one with an experienced hospitalist faculty member. The program consists of 80% clinical experience in the inpatient setting and 20% didactic instruction (Table 1). Up to four fellows are accepted each year and are eligible for hire after training if vacancies exist. The program is cost neutral and was financed by downsizing, through attrition, two physician FTEs. Four APP fellows’ salaries are the equivalent of two entry-level hospitalist physicians’ salaries at JHBMC. The annual salary for an APP fellow is $69,000.

Downsizing by two physician FTEs meant that one less doctor was scheduled every day. The patient load previously seen by that one doctor (10 patients) was absorbed by the MD–APP fellow dyads. Paired with a fellow, each physician sees a higher cap of 13 patients, and it takes six weeks for the fellows to ramp-up to this patient load. When the fellow first starts, the team sees 10 patients. Every two weeks, the pair’s census increases by one patient to the cap of 13. Collectively, the four APP fellow–MD dyads make it possible for four physicians to see an additional 12 patients. The two extra patients absorbed by the service per day results in a net increase in capacity of up to 730 patient encounters a year.

Outcomes and Analysis

Our main outcomes of interest were duration of onboarding and cost incurred by the division to (1) staff the service during a vacancy and (2) onboard new hires. Secondary outcomes included duration of vacancy and total time spent with the group. We collected basic demographic data on participants, including, age, gender, and race. Demographics and outcomes of interest were compared pre- (2009-2013) and post- (2014-2018) initiation of the APP clinical fellowship using the chi-square test, the t-test for normally distributed data, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum for nonnormally distributed data, as appropriate. The normality of the data distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Two-tailed P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. Results were analyzed using Stata/MP version 13.0 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Twelve fellows have been recruited, and of these, 10 have graduated. Two chose to leave the program prior to completion. Of the 10 fellows that have graduated, six have been hired into our group, one was hired within our facility, and three were hired as hospitalists at other institutions. The median time from APP school graduation to hire was also not different between the two groups (10.5 vs 3.9 months, P = .069). In addition, the total time that the new APP hires spent with the group was nonstatistically significantly different between the two periods (17.9 vs 18.3 months, P = .735). Both the mean duration of onboarding and the cost to the division were significantly reduced after implementation of the program (25.4 vs 11.0 weeks, P = .017 and $361,714 vs $66,000, P = .004; Table 2).

The yearly cost of an APP vacancy and onboarding is incurred by doctor moonlighting costs (at the rate of $150 per hour) to cover open shifts. The mean duration of vacancies and onboarding each year was 34.9 and 25.4 weeks, respectively, before the fellowship. The yearly cost of onboarding, after the establishment of the fellowship, is a maximum of $66,000, derived from physician moonlighting to cover the six-week ramp-up at the very beginning of the fellowship and the five weeks of orientation to the pulmonary and chemical dependency units after the fellowship (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Our APP clinical fellowship in hospital medicine at JHBMC has produced several benefits. First, the fellowship has become a pipeline for filling APP vacancies within our division. We have been able to hire for four consecutive years from the fellowship. Second, the ready availability of high-functioning and efficient APP hospitalists has cut down on the onboarding time for our new APP hires. Many new APP graduates lack confidence in caring for complex hospitalized patients. Following our 12-month clinical fellowship, our matriculated fellows are able to practice at the top of their license immediately and confidently. Third, the reduced vacancy and shortened onboarding periods have reduced costs to the division. Fourth, the fellowship has created additional teaching avenues for the faculty. The medicine units at JHBMC are comprised of hospitalist and internal medicine residency services. The hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time in direct patient care; however, they rotate on the residency service for two weeks out of the year. The majority of physicians welcome the chance to teach more, and partnering with an APP fellow provides that opportunity.

As we have developed and grown this program, the one great challenge has been what to do with graduating fellows when we cannot hire them. Fortunately, the market for highly qualified, well trained APPs is strong, and every one of the fellows that we could not hire within our group has been able to find a position either within our facility or outside our institution. To facilitate this process, program directors and recruiters are invited to meet with the fellows toward the end of their fellowship to share employment opportunities with them.

Our study has limitations. First, had the $276,000 from the attrition of two physicians been used to hire nonfellow APPs under the old model, then the costs of the two models would have been similar, but this was simply not possible because the positions could not be filled. Second, this is a single-site experience, and our findings may not be generalizable, particularly those pertaining to remuneration. Third, our study was underpowered to detect small but important differences in characteristics of APPs, especially time from graduation to hire, before and after the implementation of our fellowship. Further research comparing various programs both in structure and outcomes—such as fellows’ readiness for practice, costs, duration of vacancies, and provider satisfaction—are an important next step.

We have developed a pool of applicants within our division to fill vacancies left by turnover from senior NPs and PAs. This program has reduced costs and improved the joy of practice for both doctors and APPs. As the need for highly qualified NPs and PAs in hospital medicine continues to grow, we may see more APP fellowships in hospital medicine in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the advanced practice providers who have helped us grow and refine our fellowship.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose