User login

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

To the Editor:

Online resources that are convenient and affordable play a crucial role in mitigating health inequality and improving patient access to health care information; however, the benefits are limited by the quality of information available, as medical misinformation can lead to patients engaging in harmful practices, making dangerous decisions, and even avoiding safe and effective treatments. In this study, we aimed to assess and compare the quality of patient guidance on dermatologic care generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit based on accuracy, appropriateness, and safety. It is essential to assess the quality and reliability of online health information to support patients in making informed decisions about their health.

The emergence and advancement of artificial intelligence and large language models such as ChatGPT present a new method for patients to access health care advice. ChatGPT can engage in conversation by accessing information from existing publicly available data on the internet, including books and websites, up to the year 2023 and providing humanlike responses with context.1 ChatGPT’s access to a breadth of online evidence-based literature ensures the dissemination of quality information that is quick and without inherent bias, offering the potential to more closely align with health care professionals. ChatGPT’s use in dermatology by patients has shown efficacy, with a 98.87% approval rate by dermatologists scoring its ability to recommend appropriate medication for common dermatologic conditions.2 However, ChatGPT has limitations when providing health care advice and has been observed to misunderstand health care standards, lack personalization, and offer incorrect references; currently, the latest publicly available version (ChatGPT 3.5) also is unable to analyze clinical images.3,4

Reddit is an online social media forum that allows users to post questions and photographs to which anyone can reply and offer advice. Patients may find comfort in online communities where they can connect with others facing similar challenges related to their diagnosis. Within these communities, the responses often share users’ own lived experiences and offer support based on what has and has not worked for them. Prior research found that users intentionally seeking health information via Reddit are likely to implement the advice they receive even without verification of its credibility, suggesting a trust and receptibility to ideas offered on the platform.5 Furthermore, a study analyzing the dermatologic content of 17 dermatology related subreddits that had 1000 or more subscribers found that 70.6% of posts fell under the category of “seeking health/cosmetic advice.”6 Reddit users thus are vulnerable to receiving advice based on personal bias and exposing their health information to the public.

We hypothesized that ChatGPT would provide users with guidance that was more closely aligned with typical dermatologists’ advice due to its thorough analysis and compilation of diverse sources and recommendations available on the internet. We expected Reddit to yield recommendations of lesser quality and a diminished safety score, primarily due to the absence of credibility-vetting mechanisms and the influence of personal biases within the advice shared.

User-submitted posts to large dermatologic community Reddit forums representing a few of the most common skin conditions (r/eczema, r/acne, r/Folliculitis, r/SebDerm, r/Hidradenitis, r/keratosis, and r/Psoriasis) were retrospectively reviewed from January 2024 to March 2024. The most popular posts that did not include photographs were included in our study. Posts with photographs were excluded, as clinical images were not able to be uploaded to the publicly available ChatGPT 3.5. We collected real user questions about common skin conditions from Reddit forums and then asked ChatGPT to answer those same questions. We compared ChatGPT’s responses to the most upvoted Reddit comments to see how they matched up (eTable).

Each ChatGPT response and the top-rated Reddit comment were independently evaluated by a board certified dermatologist (S.A.) and a dermatology resident (A.H.K.). The quality of the ChatGPT and Reddit responses were determined by scoring the accuracy, appropriateness, safety consideration, and specificity on a 5-point Likert scale (1=low, 5=high). The 2 evaluators’ mean scores for each of the 4 categories were calculated based on adequate interrater reliability, which was tested using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Related-samples sign tests were used to compare ChatGPT and Reddit responses for each of the 4 categories. Analysis was completed using SPSS statistics software version 29.0 (IBM). The evaluators also were asked to provide qualitative feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of each response.

Our retrospective review yielded 20 total questions: 5 (25%) on atopic dermatitis, 4 (20%) on acne, 4 (20%) on hidradenitis suppurativa, 4 (20%) on psoriasis, 1 (5%) on folliculitis, 1 (5%) on keratosis pilaris, and 1 (5%) on seborrheic dermatitis. The number of posts was limited to 20 due to the extensive time required for grading each response. These 20 questions were selected from a larger pool of eligible posts based on factors such as clarity and relevance to common skin conditions. With regard to the types of questions that were asked, 6 (30%) were related to general management of a diagnosis, 5 (25%) were on treatment recommendations for symptom relief, 3 (15%) were on optimal utilization of current treatment regimens, 2 (10%) were on prescription side effects, 2 (10%) were on diagnosis presentation, 1 (5%) was on potential triggers of the diagnosis, and 1 (5%) was on natural treatment recommendations.

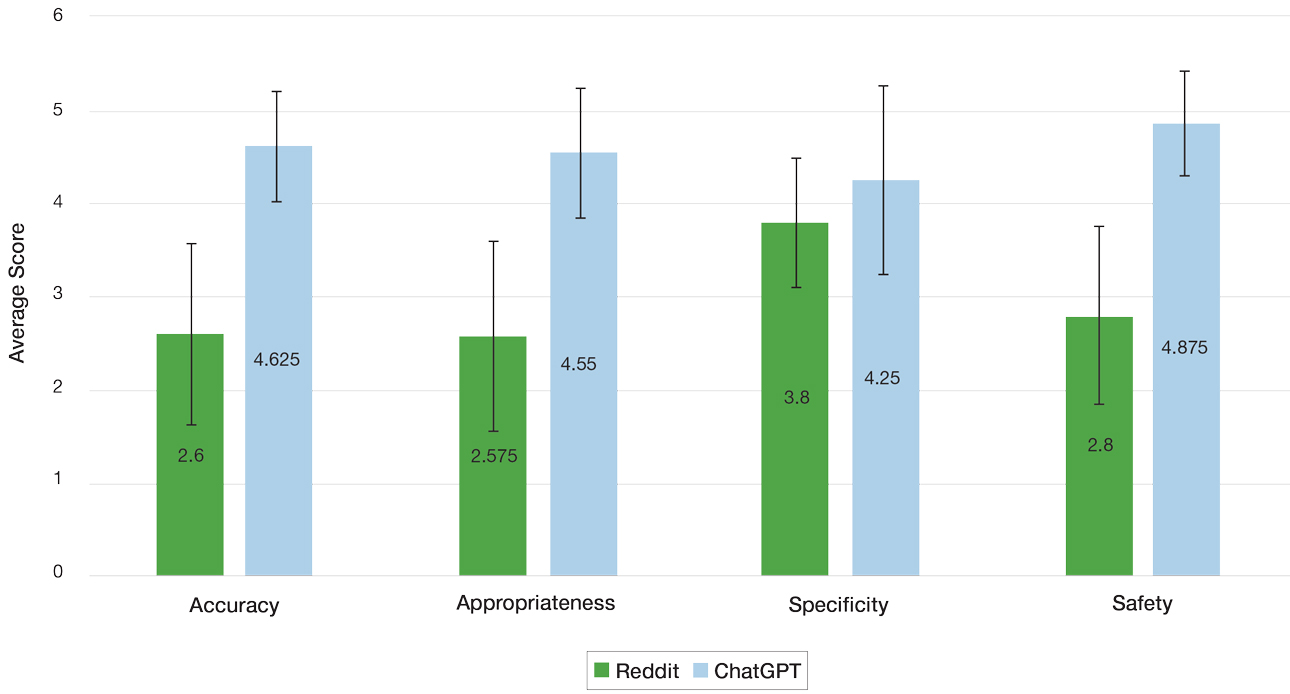

Mean (SD) evaluator scores for accuracy were significantly higher among ChatGPT responses compared with Reddit (4.63 [0.60] vs 2.60 [0.98])(P<.001). ChatGPT responses also were significantly higher for appropriateness compared with Reddit (4.55 [0.71] vs 2.58 [1.02])(P<.001) and safety consideration (4.88 [0.56] vs 2.80[0.97])(P <.001). There was no significant difference in mean specificity scores between ChatGPT and Reddit (4.25[1.02] vs 3.80 [0.70])(P=.096)(Figure).

For the Reddit responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.200 (95% CI, –.089 to .489) for accuracy, 0.255 (95% CI, .014-.497) for appropriateness, 0.385 (95% CI, .176-.594) for safety consideration, and –0.024 (95% CI, –.177 to .129) for specificity. For the ChatGPT responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.426 (95% CI, .122-.730) for accuracy, 0.571 (95% CI, .294-.849) for appropriateness, 0.655 (95% CI, .632-.678) for safety consideration, and 0.313 (95% CI, .043-.584) for specificity.

The strengths and weaknesses of the responses also were qualitatively analyzed. One commonly observed strength was ChatGPT’s frequent and appropriate recommendation for users to consult a dermatologist. In the case of atopic dermatitis—one of the more frequently asked about conditions—ChatGPT consistently emphasized evidence-based strategies such as gentle skin care and moisturization, reflecting alignment with clinical guidelines. Additionally, a common weakness of both ChatGPT and Reddit responses generally was the lack of personalized guidance and comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits of specific treatments. It also was noted that neither platform consistently explored differential diagnoses—for example, distinguishing atopic dermatitis from conditions such as allergic contact dermatitis—limiting the diagnostic depth of the responses.

ChatGPT and Reddit can provide patients with quick and accessible health information for various dermatologic concerns. The results of our study demonstrated a significantly higher level of accuracy, appropriateness, and safety of responses generated by ChatGPT compared with human-generated responses on Reddit (P<.001). Both platforms offered similarly specific responses to user inquiries, demonstrating ChatGPT’s ability to comprehend user questions and draw from publicly available texts and Reddit users’ contributing insights based on their own first-hand experiences.

Reddit’s dermatologic forums often feature personal anecdotes and unique treatments described by individual users. Although specific to particular dermatologic concerns, such advice lacks an evidence-based standard of care. With the noted inherent trust of patients seeking guidance within Reddit communities, patients may follow unhelpful or potentially dangerous medical advice.5 A study examining 300 user-submitted posts on popular Reddit dermatology forums during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the mean scores for top-rated comments’ potential to be misleading or dangerous was 2.33 out of 5 on a Likert scale (95% CI, 2.18- 2.48).7 Dermatologists should be aware of the potential risks associated with dermatologic advice offered on Reddit and should caution patients against relying solely on this information without consulting a qualified dermatologist first.

Reddit’s open-forum design provides licensed dermatologists with the opportunity to disseminate evidence based information regarding dermatologic conditions. Currently, there is a subreddit (r/AskDocs) that allows users to post medical questions that can be answered by moderator-verified physicians. Participation from dermatologists in online communities such as this can improve the quality of dermatologic information shared online, combat misinformation, and promote safe skin care practices.

ChatGPT offers more accurate, appropriate, and safe information compared to Reddit responses, but its answers lack personalization. In a clinical setting, a personalized treatment plan from a physician can be tailored with a comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits. Further, clinical settings allow for diagnosis and confirmation via biopsy and meticulous history taking to ensure that the diagnosis and treatment plan are accurate. While ChatGPT may be an option for seeking basic advice on dermatologic conditions, a licensed dermatologist should always be consulted for proper medical advice. Services such as telehealth may be another option to for patients with limited access to care.

Since ChatGPT 3.5 does not support the ability to upload images, our study acknowledges a limitation regarding the inclusion of Reddit posts containing photographs. Images can improve the response quality from both Reddit users and ChatGPT. While the updated ChatGPT 4o is capable of processing images, it requires a monthly subscription fee. The free version was chosen for use in this study, as this may reflect the most likely version that patients of low socioeconomic status would utilize to access dermatologic care; however, there is potential for growth and improvement of ChatGPT’s capability in providing medical advice.

This study compared the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT’s and Reddit’s responses to common dermatologic inquiries. ChatGPT and Reddit both show potential to be helpful sources of dermatologic health information; however, their current versions have many limitations and require caution and careful examination by patients of the guidance provided. Clinicians should be aware of these limitations when advising patients and emphasize the importance of consulting a licensed dermatologist for personalized, evidence-based care. For the best medical advice, it is always advisable to consult with a licensed dermatologist.

- Roumeliotis KI, Tselikas ND. ChatGPT and open-AI models: a preliminary review. Future Internet. 2023;15:192. doi:10.3390/fi15060192

- Iqbal U, Lee LTJ, Rahmanti AR, et al. Can large language models provide secondary reliable opinion on treatment options for dermatological diseases? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31:1341-1347. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocae067

- Whiles BB, Bird VG, Canales BK, et al. Caution! AI bot has entered the patient chat: ChatGPT has limitations in providing accurate urologic healthcare advice. Urology. 2023;180:278-284. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.07.010

- Nastasi AJ, Courtright KR, Halpern SD, et al. A vignette-based evaluation of ChatGPT’s ability to provide appropriate and equitable medical advice across care contexts. Sci Rep. 2023;13:17885. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45223-y

- Record RA, Silberman WR, Santiago JE, et al. I sought it, I Reddit: examining health information engagement behaviors among Reddit users. J Health Commun. 2018;23:470-476. doi:10.1080/1081073 0.2018.1465493

- Buntinx-Krieg T, Caravaglio J, Domozych R, et al. Dermatology on Reddit: elucidating trends in dermatologic communications on the world wide web. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9dr1f7x6.

- Aboul-Fettouh N, Lee KP, Kash N, et al. Social media and dermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyzing usersubmitted posts seeking dermatologic advice on Reddit. Cureus. 2023;15:E33720. doi:10.7759/cureus.33720

To the Editor:

Online resources that are convenient and affordable play a crucial role in mitigating health inequality and improving patient access to health care information; however, the benefits are limited by the quality of information available, as medical misinformation can lead to patients engaging in harmful practices, making dangerous decisions, and even avoiding safe and effective treatments. In this study, we aimed to assess and compare the quality of patient guidance on dermatologic care generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit based on accuracy, appropriateness, and safety. It is essential to assess the quality and reliability of online health information to support patients in making informed decisions about their health.

The emergence and advancement of artificial intelligence and large language models such as ChatGPT present a new method for patients to access health care advice. ChatGPT can engage in conversation by accessing information from existing publicly available data on the internet, including books and websites, up to the year 2023 and providing humanlike responses with context.1 ChatGPT’s access to a breadth of online evidence-based literature ensures the dissemination of quality information that is quick and without inherent bias, offering the potential to more closely align with health care professionals. ChatGPT’s use in dermatology by patients has shown efficacy, with a 98.87% approval rate by dermatologists scoring its ability to recommend appropriate medication for common dermatologic conditions.2 However, ChatGPT has limitations when providing health care advice and has been observed to misunderstand health care standards, lack personalization, and offer incorrect references; currently, the latest publicly available version (ChatGPT 3.5) also is unable to analyze clinical images.3,4

Reddit is an online social media forum that allows users to post questions and photographs to which anyone can reply and offer advice. Patients may find comfort in online communities where they can connect with others facing similar challenges related to their diagnosis. Within these communities, the responses often share users’ own lived experiences and offer support based on what has and has not worked for them. Prior research found that users intentionally seeking health information via Reddit are likely to implement the advice they receive even without verification of its credibility, suggesting a trust and receptibility to ideas offered on the platform.5 Furthermore, a study analyzing the dermatologic content of 17 dermatology related subreddits that had 1000 or more subscribers found that 70.6% of posts fell under the category of “seeking health/cosmetic advice.”6 Reddit users thus are vulnerable to receiving advice based on personal bias and exposing their health information to the public.

We hypothesized that ChatGPT would provide users with guidance that was more closely aligned with typical dermatologists’ advice due to its thorough analysis and compilation of diverse sources and recommendations available on the internet. We expected Reddit to yield recommendations of lesser quality and a diminished safety score, primarily due to the absence of credibility-vetting mechanisms and the influence of personal biases within the advice shared.

User-submitted posts to large dermatologic community Reddit forums representing a few of the most common skin conditions (r/eczema, r/acne, r/Folliculitis, r/SebDerm, r/Hidradenitis, r/keratosis, and r/Psoriasis) were retrospectively reviewed from January 2024 to March 2024. The most popular posts that did not include photographs were included in our study. Posts with photographs were excluded, as clinical images were not able to be uploaded to the publicly available ChatGPT 3.5. We collected real user questions about common skin conditions from Reddit forums and then asked ChatGPT to answer those same questions. We compared ChatGPT’s responses to the most upvoted Reddit comments to see how they matched up (eTable).

Each ChatGPT response and the top-rated Reddit comment were independently evaluated by a board certified dermatologist (S.A.) and a dermatology resident (A.H.K.). The quality of the ChatGPT and Reddit responses were determined by scoring the accuracy, appropriateness, safety consideration, and specificity on a 5-point Likert scale (1=low, 5=high). The 2 evaluators’ mean scores for each of the 4 categories were calculated based on adequate interrater reliability, which was tested using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Related-samples sign tests were used to compare ChatGPT and Reddit responses for each of the 4 categories. Analysis was completed using SPSS statistics software version 29.0 (IBM). The evaluators also were asked to provide qualitative feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of each response.

Our retrospective review yielded 20 total questions: 5 (25%) on atopic dermatitis, 4 (20%) on acne, 4 (20%) on hidradenitis suppurativa, 4 (20%) on psoriasis, 1 (5%) on folliculitis, 1 (5%) on keratosis pilaris, and 1 (5%) on seborrheic dermatitis. The number of posts was limited to 20 due to the extensive time required for grading each response. These 20 questions were selected from a larger pool of eligible posts based on factors such as clarity and relevance to common skin conditions. With regard to the types of questions that were asked, 6 (30%) were related to general management of a diagnosis, 5 (25%) were on treatment recommendations for symptom relief, 3 (15%) were on optimal utilization of current treatment regimens, 2 (10%) were on prescription side effects, 2 (10%) were on diagnosis presentation, 1 (5%) was on potential triggers of the diagnosis, and 1 (5%) was on natural treatment recommendations.

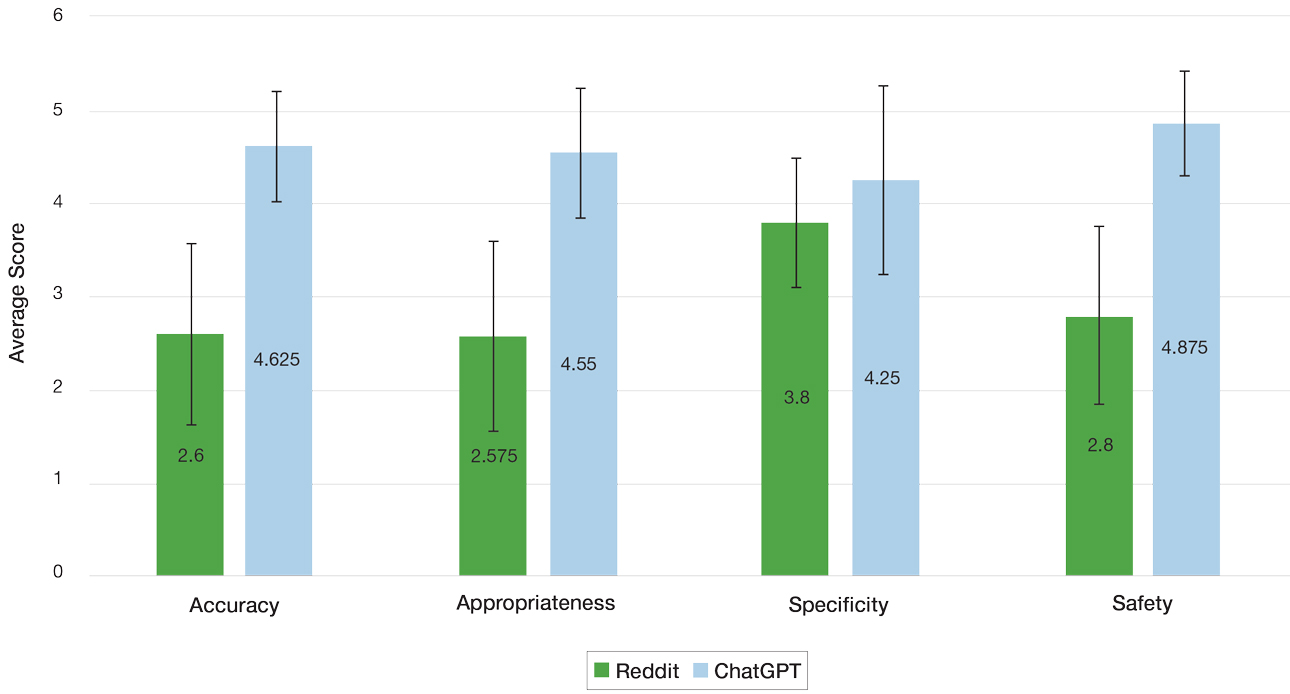

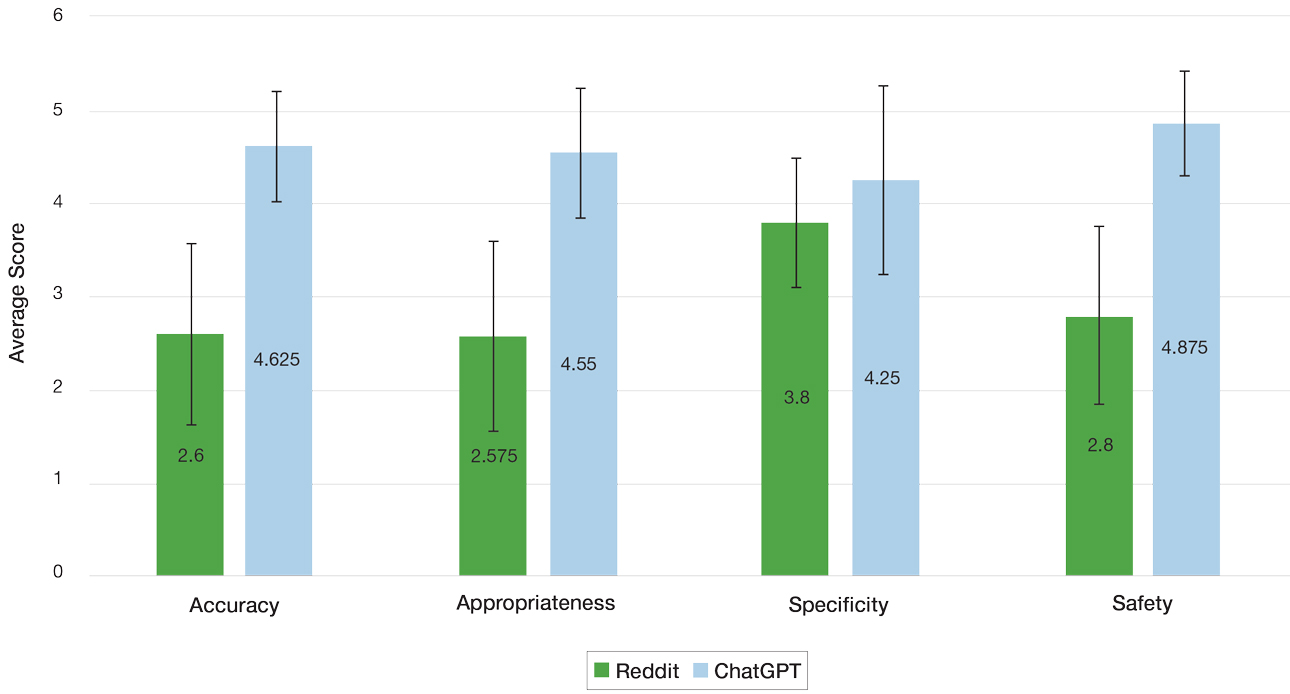

Mean (SD) evaluator scores for accuracy were significantly higher among ChatGPT responses compared with Reddit (4.63 [0.60] vs 2.60 [0.98])(P<.001). ChatGPT responses also were significantly higher for appropriateness compared with Reddit (4.55 [0.71] vs 2.58 [1.02])(P<.001) and safety consideration (4.88 [0.56] vs 2.80[0.97])(P <.001). There was no significant difference in mean specificity scores between ChatGPT and Reddit (4.25[1.02] vs 3.80 [0.70])(P=.096)(Figure).

For the Reddit responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.200 (95% CI, –.089 to .489) for accuracy, 0.255 (95% CI, .014-.497) for appropriateness, 0.385 (95% CI, .176-.594) for safety consideration, and –0.024 (95% CI, –.177 to .129) for specificity. For the ChatGPT responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.426 (95% CI, .122-.730) for accuracy, 0.571 (95% CI, .294-.849) for appropriateness, 0.655 (95% CI, .632-.678) for safety consideration, and 0.313 (95% CI, .043-.584) for specificity.

The strengths and weaknesses of the responses also were qualitatively analyzed. One commonly observed strength was ChatGPT’s frequent and appropriate recommendation for users to consult a dermatologist. In the case of atopic dermatitis—one of the more frequently asked about conditions—ChatGPT consistently emphasized evidence-based strategies such as gentle skin care and moisturization, reflecting alignment with clinical guidelines. Additionally, a common weakness of both ChatGPT and Reddit responses generally was the lack of personalized guidance and comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits of specific treatments. It also was noted that neither platform consistently explored differential diagnoses—for example, distinguishing atopic dermatitis from conditions such as allergic contact dermatitis—limiting the diagnostic depth of the responses.

ChatGPT and Reddit can provide patients with quick and accessible health information for various dermatologic concerns. The results of our study demonstrated a significantly higher level of accuracy, appropriateness, and safety of responses generated by ChatGPT compared with human-generated responses on Reddit (P<.001). Both platforms offered similarly specific responses to user inquiries, demonstrating ChatGPT’s ability to comprehend user questions and draw from publicly available texts and Reddit users’ contributing insights based on their own first-hand experiences.

Reddit’s dermatologic forums often feature personal anecdotes and unique treatments described by individual users. Although specific to particular dermatologic concerns, such advice lacks an evidence-based standard of care. With the noted inherent trust of patients seeking guidance within Reddit communities, patients may follow unhelpful or potentially dangerous medical advice.5 A study examining 300 user-submitted posts on popular Reddit dermatology forums during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the mean scores for top-rated comments’ potential to be misleading or dangerous was 2.33 out of 5 on a Likert scale (95% CI, 2.18- 2.48).7 Dermatologists should be aware of the potential risks associated with dermatologic advice offered on Reddit and should caution patients against relying solely on this information without consulting a qualified dermatologist first.

Reddit’s open-forum design provides licensed dermatologists with the opportunity to disseminate evidence based information regarding dermatologic conditions. Currently, there is a subreddit (r/AskDocs) that allows users to post medical questions that can be answered by moderator-verified physicians. Participation from dermatologists in online communities such as this can improve the quality of dermatologic information shared online, combat misinformation, and promote safe skin care practices.

ChatGPT offers more accurate, appropriate, and safe information compared to Reddit responses, but its answers lack personalization. In a clinical setting, a personalized treatment plan from a physician can be tailored with a comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits. Further, clinical settings allow for diagnosis and confirmation via biopsy and meticulous history taking to ensure that the diagnosis and treatment plan are accurate. While ChatGPT may be an option for seeking basic advice on dermatologic conditions, a licensed dermatologist should always be consulted for proper medical advice. Services such as telehealth may be another option to for patients with limited access to care.

Since ChatGPT 3.5 does not support the ability to upload images, our study acknowledges a limitation regarding the inclusion of Reddit posts containing photographs. Images can improve the response quality from both Reddit users and ChatGPT. While the updated ChatGPT 4o is capable of processing images, it requires a monthly subscription fee. The free version was chosen for use in this study, as this may reflect the most likely version that patients of low socioeconomic status would utilize to access dermatologic care; however, there is potential for growth and improvement of ChatGPT’s capability in providing medical advice.

This study compared the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT’s and Reddit’s responses to common dermatologic inquiries. ChatGPT and Reddit both show potential to be helpful sources of dermatologic health information; however, their current versions have many limitations and require caution and careful examination by patients of the guidance provided. Clinicians should be aware of these limitations when advising patients and emphasize the importance of consulting a licensed dermatologist for personalized, evidence-based care. For the best medical advice, it is always advisable to consult with a licensed dermatologist.

To the Editor:

Online resources that are convenient and affordable play a crucial role in mitigating health inequality and improving patient access to health care information; however, the benefits are limited by the quality of information available, as medical misinformation can lead to patients engaging in harmful practices, making dangerous decisions, and even avoiding safe and effective treatments. In this study, we aimed to assess and compare the quality of patient guidance on dermatologic care generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit based on accuracy, appropriateness, and safety. It is essential to assess the quality and reliability of online health information to support patients in making informed decisions about their health.

The emergence and advancement of artificial intelligence and large language models such as ChatGPT present a new method for patients to access health care advice. ChatGPT can engage in conversation by accessing information from existing publicly available data on the internet, including books and websites, up to the year 2023 and providing humanlike responses with context.1 ChatGPT’s access to a breadth of online evidence-based literature ensures the dissemination of quality information that is quick and without inherent bias, offering the potential to more closely align with health care professionals. ChatGPT’s use in dermatology by patients has shown efficacy, with a 98.87% approval rate by dermatologists scoring its ability to recommend appropriate medication for common dermatologic conditions.2 However, ChatGPT has limitations when providing health care advice and has been observed to misunderstand health care standards, lack personalization, and offer incorrect references; currently, the latest publicly available version (ChatGPT 3.5) also is unable to analyze clinical images.3,4

Reddit is an online social media forum that allows users to post questions and photographs to which anyone can reply and offer advice. Patients may find comfort in online communities where they can connect with others facing similar challenges related to their diagnosis. Within these communities, the responses often share users’ own lived experiences and offer support based on what has and has not worked for them. Prior research found that users intentionally seeking health information via Reddit are likely to implement the advice they receive even without verification of its credibility, suggesting a trust and receptibility to ideas offered on the platform.5 Furthermore, a study analyzing the dermatologic content of 17 dermatology related subreddits that had 1000 or more subscribers found that 70.6% of posts fell under the category of “seeking health/cosmetic advice.”6 Reddit users thus are vulnerable to receiving advice based on personal bias and exposing their health information to the public.

We hypothesized that ChatGPT would provide users with guidance that was more closely aligned with typical dermatologists’ advice due to its thorough analysis and compilation of diverse sources and recommendations available on the internet. We expected Reddit to yield recommendations of lesser quality and a diminished safety score, primarily due to the absence of credibility-vetting mechanisms and the influence of personal biases within the advice shared.

User-submitted posts to large dermatologic community Reddit forums representing a few of the most common skin conditions (r/eczema, r/acne, r/Folliculitis, r/SebDerm, r/Hidradenitis, r/keratosis, and r/Psoriasis) were retrospectively reviewed from January 2024 to March 2024. The most popular posts that did not include photographs were included in our study. Posts with photographs were excluded, as clinical images were not able to be uploaded to the publicly available ChatGPT 3.5. We collected real user questions about common skin conditions from Reddit forums and then asked ChatGPT to answer those same questions. We compared ChatGPT’s responses to the most upvoted Reddit comments to see how they matched up (eTable).

Each ChatGPT response and the top-rated Reddit comment were independently evaluated by a board certified dermatologist (S.A.) and a dermatology resident (A.H.K.). The quality of the ChatGPT and Reddit responses were determined by scoring the accuracy, appropriateness, safety consideration, and specificity on a 5-point Likert scale (1=low, 5=high). The 2 evaluators’ mean scores for each of the 4 categories were calculated based on adequate interrater reliability, which was tested using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Related-samples sign tests were used to compare ChatGPT and Reddit responses for each of the 4 categories. Analysis was completed using SPSS statistics software version 29.0 (IBM). The evaluators also were asked to provide qualitative feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of each response.

Our retrospective review yielded 20 total questions: 5 (25%) on atopic dermatitis, 4 (20%) on acne, 4 (20%) on hidradenitis suppurativa, 4 (20%) on psoriasis, 1 (5%) on folliculitis, 1 (5%) on keratosis pilaris, and 1 (5%) on seborrheic dermatitis. The number of posts was limited to 20 due to the extensive time required for grading each response. These 20 questions were selected from a larger pool of eligible posts based on factors such as clarity and relevance to common skin conditions. With regard to the types of questions that were asked, 6 (30%) were related to general management of a diagnosis, 5 (25%) were on treatment recommendations for symptom relief, 3 (15%) were on optimal utilization of current treatment regimens, 2 (10%) were on prescription side effects, 2 (10%) were on diagnosis presentation, 1 (5%) was on potential triggers of the diagnosis, and 1 (5%) was on natural treatment recommendations.

Mean (SD) evaluator scores for accuracy were significantly higher among ChatGPT responses compared with Reddit (4.63 [0.60] vs 2.60 [0.98])(P<.001). ChatGPT responses also were significantly higher for appropriateness compared with Reddit (4.55 [0.71] vs 2.58 [1.02])(P<.001) and safety consideration (4.88 [0.56] vs 2.80[0.97])(P <.001). There was no significant difference in mean specificity scores between ChatGPT and Reddit (4.25[1.02] vs 3.80 [0.70])(P=.096)(Figure).

For the Reddit responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.200 (95% CI, –.089 to .489) for accuracy, 0.255 (95% CI, .014-.497) for appropriateness, 0.385 (95% CI, .176-.594) for safety consideration, and –0.024 (95% CI, –.177 to .129) for specificity. For the ChatGPT responses, the weighted Cohen’s κ coefficient between the 2 evaluators was 0.426 (95% CI, .122-.730) for accuracy, 0.571 (95% CI, .294-.849) for appropriateness, 0.655 (95% CI, .632-.678) for safety consideration, and 0.313 (95% CI, .043-.584) for specificity.

The strengths and weaknesses of the responses also were qualitatively analyzed. One commonly observed strength was ChatGPT’s frequent and appropriate recommendation for users to consult a dermatologist. In the case of atopic dermatitis—one of the more frequently asked about conditions—ChatGPT consistently emphasized evidence-based strategies such as gentle skin care and moisturization, reflecting alignment with clinical guidelines. Additionally, a common weakness of both ChatGPT and Reddit responses generally was the lack of personalized guidance and comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits of specific treatments. It also was noted that neither platform consistently explored differential diagnoses—for example, distinguishing atopic dermatitis from conditions such as allergic contact dermatitis—limiting the diagnostic depth of the responses.

ChatGPT and Reddit can provide patients with quick and accessible health information for various dermatologic concerns. The results of our study demonstrated a significantly higher level of accuracy, appropriateness, and safety of responses generated by ChatGPT compared with human-generated responses on Reddit (P<.001). Both platforms offered similarly specific responses to user inquiries, demonstrating ChatGPT’s ability to comprehend user questions and draw from publicly available texts and Reddit users’ contributing insights based on their own first-hand experiences.

Reddit’s dermatologic forums often feature personal anecdotes and unique treatments described by individual users. Although specific to particular dermatologic concerns, such advice lacks an evidence-based standard of care. With the noted inherent trust of patients seeking guidance within Reddit communities, patients may follow unhelpful or potentially dangerous medical advice.5 A study examining 300 user-submitted posts on popular Reddit dermatology forums during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the mean scores for top-rated comments’ potential to be misleading or dangerous was 2.33 out of 5 on a Likert scale (95% CI, 2.18- 2.48).7 Dermatologists should be aware of the potential risks associated with dermatologic advice offered on Reddit and should caution patients against relying solely on this information without consulting a qualified dermatologist first.

Reddit’s open-forum design provides licensed dermatologists with the opportunity to disseminate evidence based information regarding dermatologic conditions. Currently, there is a subreddit (r/AskDocs) that allows users to post medical questions that can be answered by moderator-verified physicians. Participation from dermatologists in online communities such as this can improve the quality of dermatologic information shared online, combat misinformation, and promote safe skin care practices.

ChatGPT offers more accurate, appropriate, and safe information compared to Reddit responses, but its answers lack personalization. In a clinical setting, a personalized treatment plan from a physician can be tailored with a comprehensive discussion of the risks and benefits. Further, clinical settings allow for diagnosis and confirmation via biopsy and meticulous history taking to ensure that the diagnosis and treatment plan are accurate. While ChatGPT may be an option for seeking basic advice on dermatologic conditions, a licensed dermatologist should always be consulted for proper medical advice. Services such as telehealth may be another option to for patients with limited access to care.

Since ChatGPT 3.5 does not support the ability to upload images, our study acknowledges a limitation regarding the inclusion of Reddit posts containing photographs. Images can improve the response quality from both Reddit users and ChatGPT. While the updated ChatGPT 4o is capable of processing images, it requires a monthly subscription fee. The free version was chosen for use in this study, as this may reflect the most likely version that patients of low socioeconomic status would utilize to access dermatologic care; however, there is potential for growth and improvement of ChatGPT’s capability in providing medical advice.

This study compared the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT’s and Reddit’s responses to common dermatologic inquiries. ChatGPT and Reddit both show potential to be helpful sources of dermatologic health information; however, their current versions have many limitations and require caution and careful examination by patients of the guidance provided. Clinicians should be aware of these limitations when advising patients and emphasize the importance of consulting a licensed dermatologist for personalized, evidence-based care. For the best medical advice, it is always advisable to consult with a licensed dermatologist.

- Roumeliotis KI, Tselikas ND. ChatGPT and open-AI models: a preliminary review. Future Internet. 2023;15:192. doi:10.3390/fi15060192

- Iqbal U, Lee LTJ, Rahmanti AR, et al. Can large language models provide secondary reliable opinion on treatment options for dermatological diseases? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31:1341-1347. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocae067

- Whiles BB, Bird VG, Canales BK, et al. Caution! AI bot has entered the patient chat: ChatGPT has limitations in providing accurate urologic healthcare advice. Urology. 2023;180:278-284. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.07.010

- Nastasi AJ, Courtright KR, Halpern SD, et al. A vignette-based evaluation of ChatGPT’s ability to provide appropriate and equitable medical advice across care contexts. Sci Rep. 2023;13:17885. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45223-y

- Record RA, Silberman WR, Santiago JE, et al. I sought it, I Reddit: examining health information engagement behaviors among Reddit users. J Health Commun. 2018;23:470-476. doi:10.1080/1081073 0.2018.1465493

- Buntinx-Krieg T, Caravaglio J, Domozych R, et al. Dermatology on Reddit: elucidating trends in dermatologic communications on the world wide web. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9dr1f7x6.

- Aboul-Fettouh N, Lee KP, Kash N, et al. Social media and dermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyzing usersubmitted posts seeking dermatologic advice on Reddit. Cureus. 2023;15:E33720. doi:10.7759/cureus.33720

- Roumeliotis KI, Tselikas ND. ChatGPT and open-AI models: a preliminary review. Future Internet. 2023;15:192. doi:10.3390/fi15060192

- Iqbal U, Lee LTJ, Rahmanti AR, et al. Can large language models provide secondary reliable opinion on treatment options for dermatological diseases? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31:1341-1347. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocae067

- Whiles BB, Bird VG, Canales BK, et al. Caution! AI bot has entered the patient chat: ChatGPT has limitations in providing accurate urologic healthcare advice. Urology. 2023;180:278-284. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.07.010

- Nastasi AJ, Courtright KR, Halpern SD, et al. A vignette-based evaluation of ChatGPT’s ability to provide appropriate and equitable medical advice across care contexts. Sci Rep. 2023;13:17885. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45223-y

- Record RA, Silberman WR, Santiago JE, et al. I sought it, I Reddit: examining health information engagement behaviors among Reddit users. J Health Commun. 2018;23:470-476. doi:10.1080/1081073 0.2018.1465493

- Buntinx-Krieg T, Caravaglio J, Domozych R, et al. Dermatology on Reddit: elucidating trends in dermatologic communications on the world wide web. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9dr1f7x6.

- Aboul-Fettouh N, Lee KP, Kash N, et al. Social media and dermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyzing usersubmitted posts seeking dermatologic advice on Reddit. Cureus. 2023;15:E33720. doi:10.7759/cureus.33720

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

PRACTICE POINTS

- ChatGPT and Reddit are free, convenient, and accessible online resources that patients may use for guidance on dermatologic care.

- Dermatologists should be aware of the potential risks associated with obtaining medical guidance from ChatGPT and Reddit and caution patients on them.

- An increasing presence of dermatologists on online public forums can increase the dissemination of reliable health care information.

Impact of Multisite Patient Education on Pharmacotherapy for Veterans With Alcohol Use Disorder

Impact of Multisite Patient Education on Pharmacotherapy for Veterans With Alcohol Use Disorder

Excessive alcohol use is one of the leading preventable causes of death in the United States, responsible for about 178,000 deaths annually and an average of 488 daily deaths in 2020 and 2021.1Alcohol-related deaths increased by 49% between 2006 and 2019.2 This trend continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, with death certificates that listed alcohol increasing by > 25% from 2019 to 2020, and another 10% in 2021.3 This increase of alcohol-related deaths includes those as a direct result of chronic alcohol use, such as alcoholic cardiomyopathy, alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, and alcohol-induced pancreatitis, as well as a result of acute use such as alcohol poisoning, suicide by exposure to alcohol, and alcohol-impaired driving fatalities.4

Excessive alcohol consumption poses other serious risks, including cases when intake is abruptly reduced without proper management. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) can vary in severity, with potentially life-threatening complications such as hallucinations, seizures, and delirium tremens.5

These risks highlight the importance of professional intervention and support, not only to mitigate risks associated with AWS, but provide a pathway towards recovery from alcohol use disorder (AUD).

According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 28.8 million US adults had AUD in the prior year, yet only 7.6% of these individuals received treatment and an even smaller group (2.2%) received medication-assisted treatment for alcohol.6,7 This is despite American Psychiatric Association guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of patients with AUD, including the use of naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, topiramate, or gabapentin, depending on therapy goals, past medication trials, medication contraindications, and patient preference.8 Several of these medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AUD and have support for effectiveness from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses.9-11

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of substance use disorders (SUDs) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and US Department of Defense have strong recommendations for naltrexone and topiramate as first-line pharmacotherapies for moderate to severe AUD. Acamprosate and disulfiram are weak recommendations as alternative options. Gabapentin is a weak recommendation for cases where first-line treatments are contraindicated or ineffective. The guidelines emphasize the importance of a comprehensive approach to AUD treatment, including psychosocial interventions in addition to pharmacotherapy.12

A 2023 national survey found veterans reported higher alcohol consumption than nonveterans.13 At the end of fiscal year 2023, > 4.4 million veterans—6% of Veterans Health Administration patients—had been diagnosed with AUD.14 However, > 87% of these patients nationally, and 88% of Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 21 patients, were not receiving naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, or topiramate as part of their treatment. The VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) now includes AUD pharmacotherapy as a campaign focus, highlighting its importance. The ADS is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote aligning prescribing behavior with best practices. Academic detailing methods include speaking with health care practitioners (HCPs), and direct-to-consumer (DTC) patient education.

ADS campaigns include DTC educational handouts. Past ADS projects and research using DTC have demonstrated a significant improvement in outcomes and positively influencing patients’ pharmacotherapy treatment. 15,16 A VA quality improvement project found a positive correlation between the initiation of AUD pharmacotherapy and engagement with mental health care following the distribution of AUD DTC patient education. 17 This project aimed to apply the same principles of prior research to explore the use of DTC across multiple facilities within VISN 21 to increase AUD pharmacotherapy. VISN 21 includes VA facilities and clinics across the Pacific Islands, Nevada, and California and serves about 350,000 veterans.

METHODS

A prospective cohort of VISN 21 veterans with or at high risk for AUD was identified using the VA ADS AUD Dashboard. The cohort included those not on acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, topiramate, or gabapentin for treatment of AUD and had an elevated Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) score of ≥ 6 (high risk) with an AUD diagnosis or ≥ 8 (severe risk) without a diagnosis. The AUDIT-C scores used in the dashboard are supported by the VA AUD clinician guide as the minimum scores when AUD pharmacotherapy should be offered to patients.18 Prescriptions filled outside the VA were not included in this dashboard.

Data and patient information were collected using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. To be eligible, veterans needed a valid mailing address within the VISN 21 region and a primary care, mental health, or SUD clinician prescriber visit scheduled between October 1, 2023, and January 31, 2024. Veterans were excluded if they were in hospice, had a 1-year mortality risk score > 50% based on their Care Assessment Need (CAN) score, or facility leadership opted out of project involvement. Patients with both severe renal and hepatic impairments were excluded because they were ineligible for AUD pharmacotherapy. However, veterans with either renal or hepatic impairment (but not both) were included, as they could be potential candidates for ≥ 1 AUD pharmacotherapy option.

Initial correspondence with facilities was initiated through local academic detailers. A local champion was identified for the 1 facility without an academic detailer. Facilities could opt in or out of the project. Approval was provided by the local pharmacy and therapeutics committee, pharmacy, primary care, or psychiatry leadership. Approval process and clinician involvement varied by site.

Education

The selected AUD patient education was designed and approved by the national VA ADS (eappendix). The DTC patient education provided general knowledge about alcohol, including what constitutes a standard amount of alcohol, what is considered heavy drinking, risks of heavy drinking, creating a plan with a clinician to reduce and manage withdrawal symptoms, and additional resources. The DTC was accompanied by a cover letter that included a local facility contact number.

A centralized mailing facility was used for all materials. VA Northern California Health Care System provided the funding to cover the cost of postage. The list of veterans to be contacted was updated on a rolling basis and DTC education was mailed 2 weeks prior to their scheduled prescriber visit.

The eligible cohort of 1260 veterans received DTC education. A comparator group of 2048 veterans that did not receive DTC education was obtained retrospectively by using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria with a scheduled primary care, mental health, or SUD HCP visit from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023. The outcomes assessed were within 30 days of the scheduled visit, with the primary outcome as the initiation of AUD-related pharmacotherapy and the secondary outcome as the placement of a consultation for mental health or SUD services. Any consultations sent to Behavioral Health, Addiction, Mental Health, Psychiatric, and SUD services following the HCP visit, within the specified time frame, were used for the secondary outcome.

Matching and Analysis

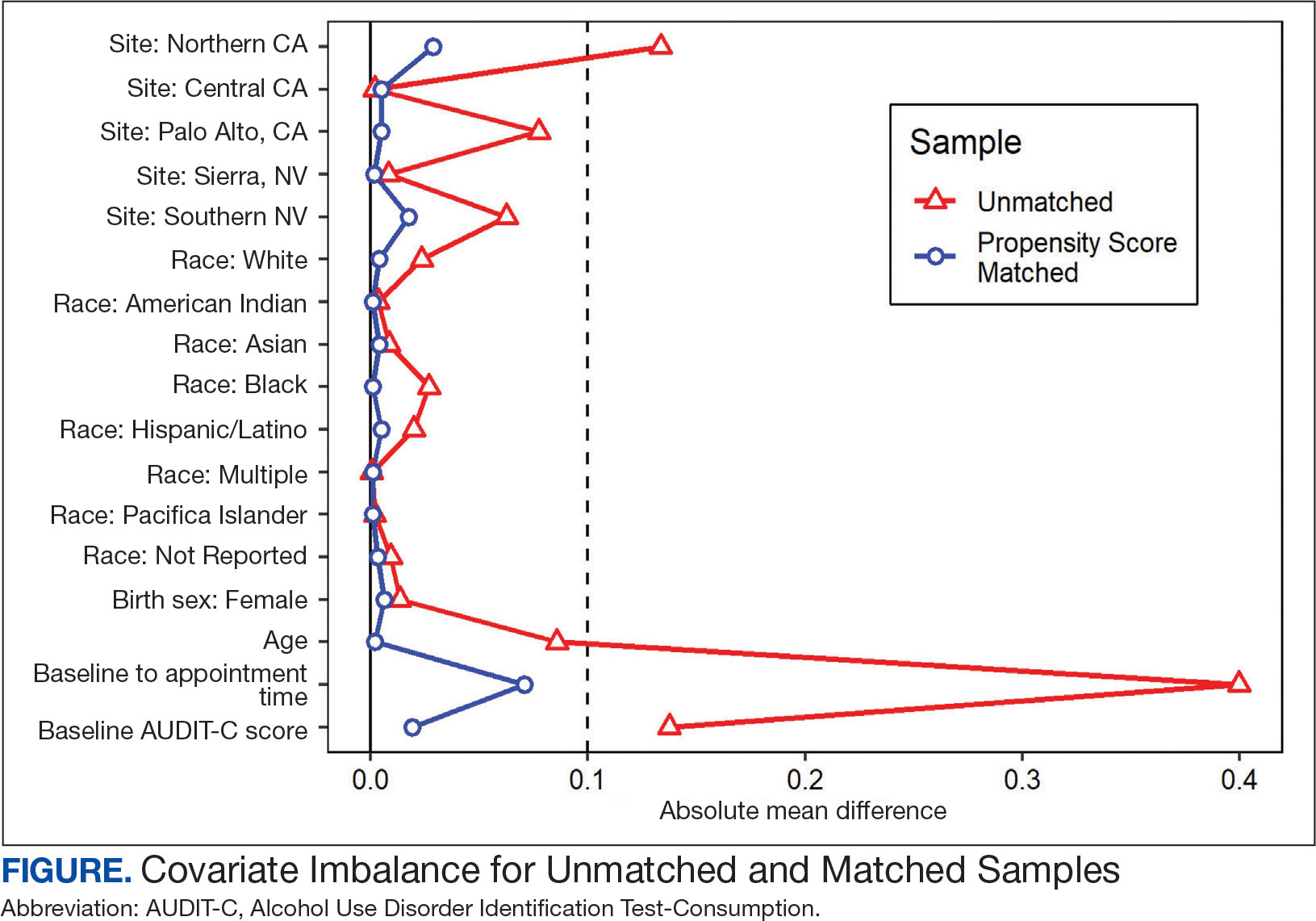

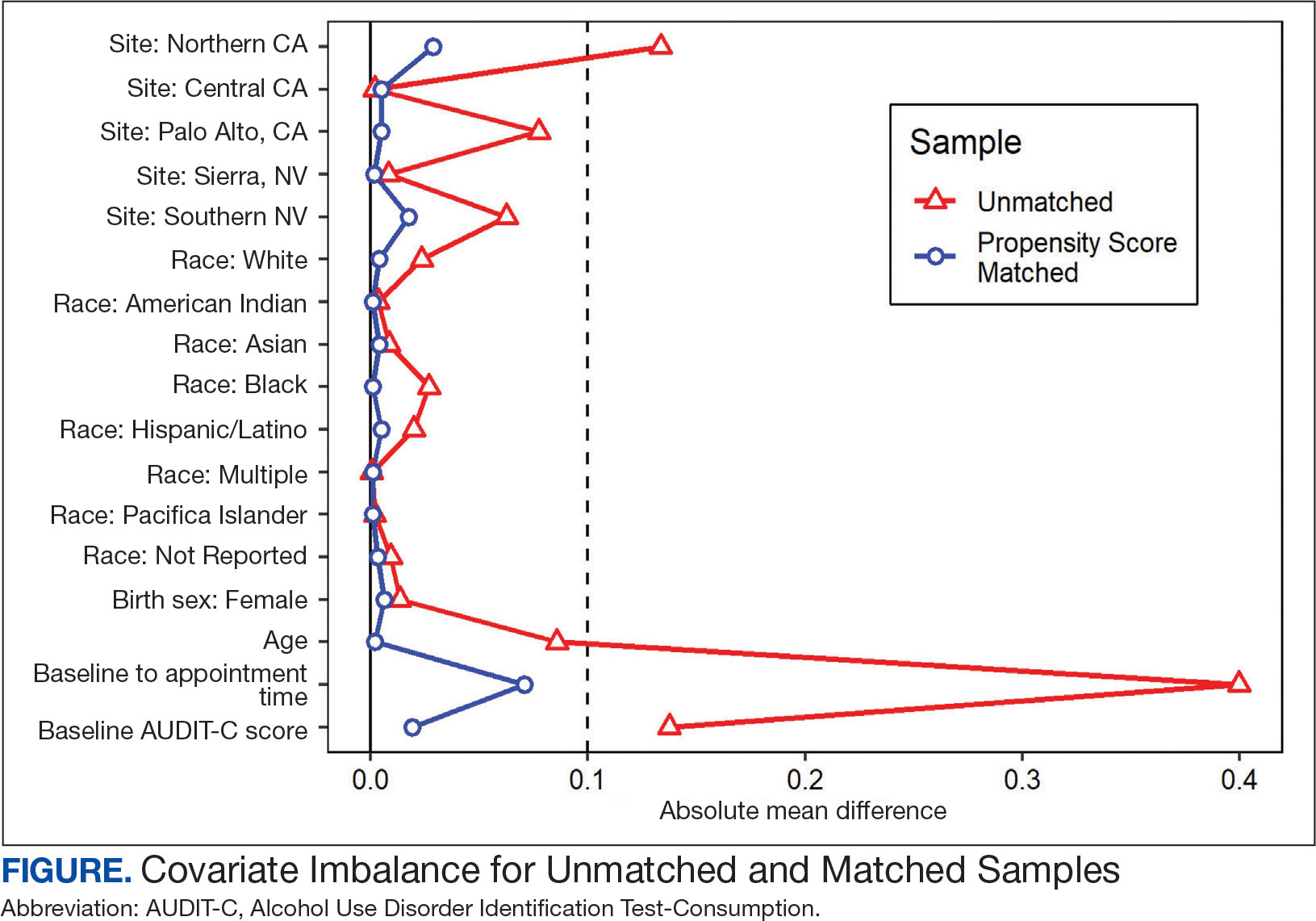

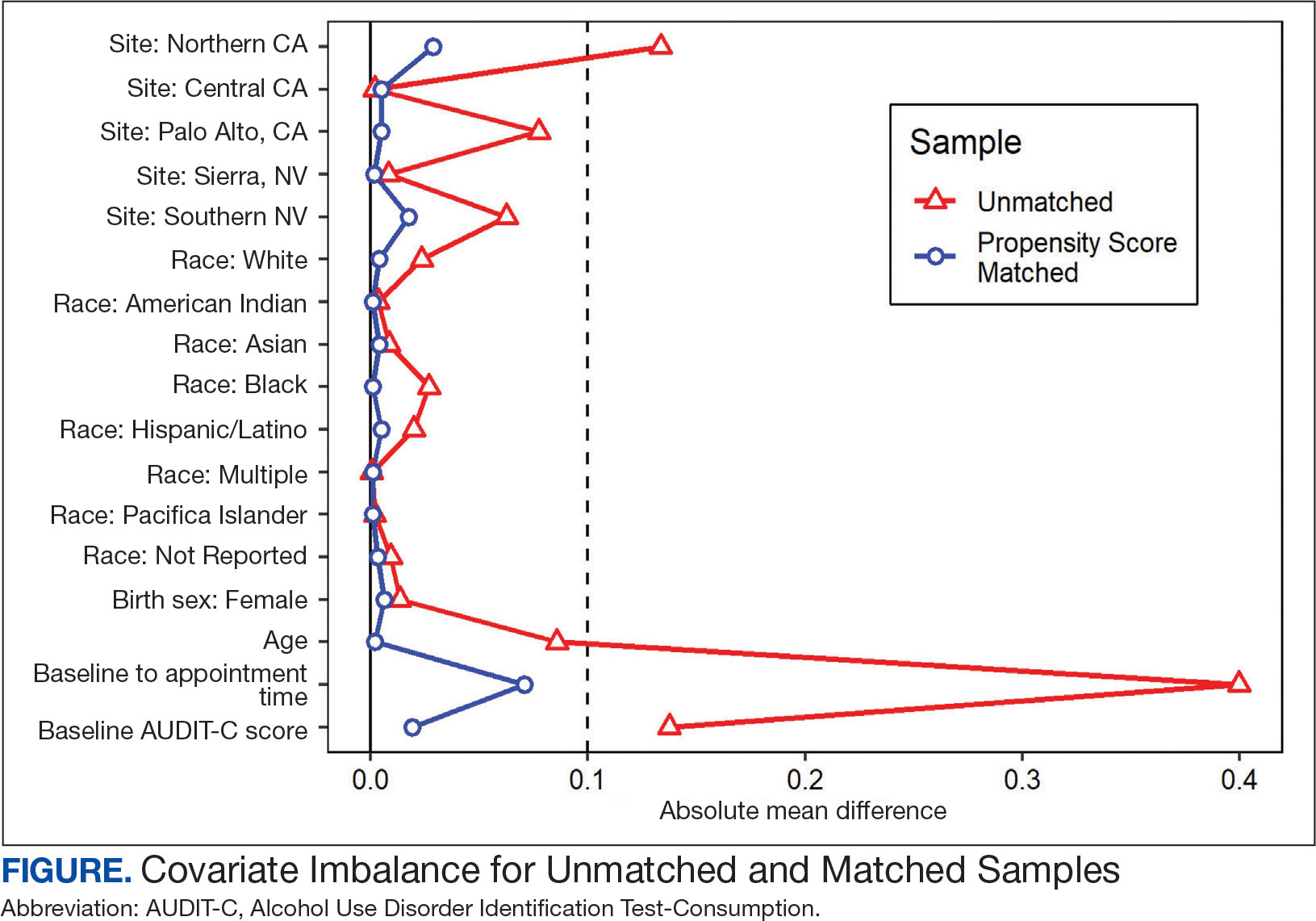

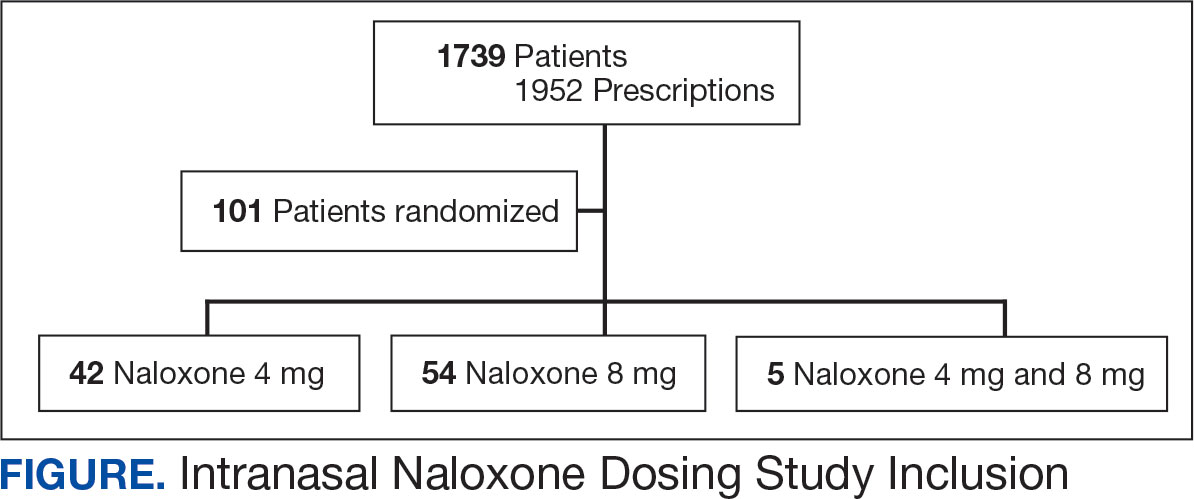

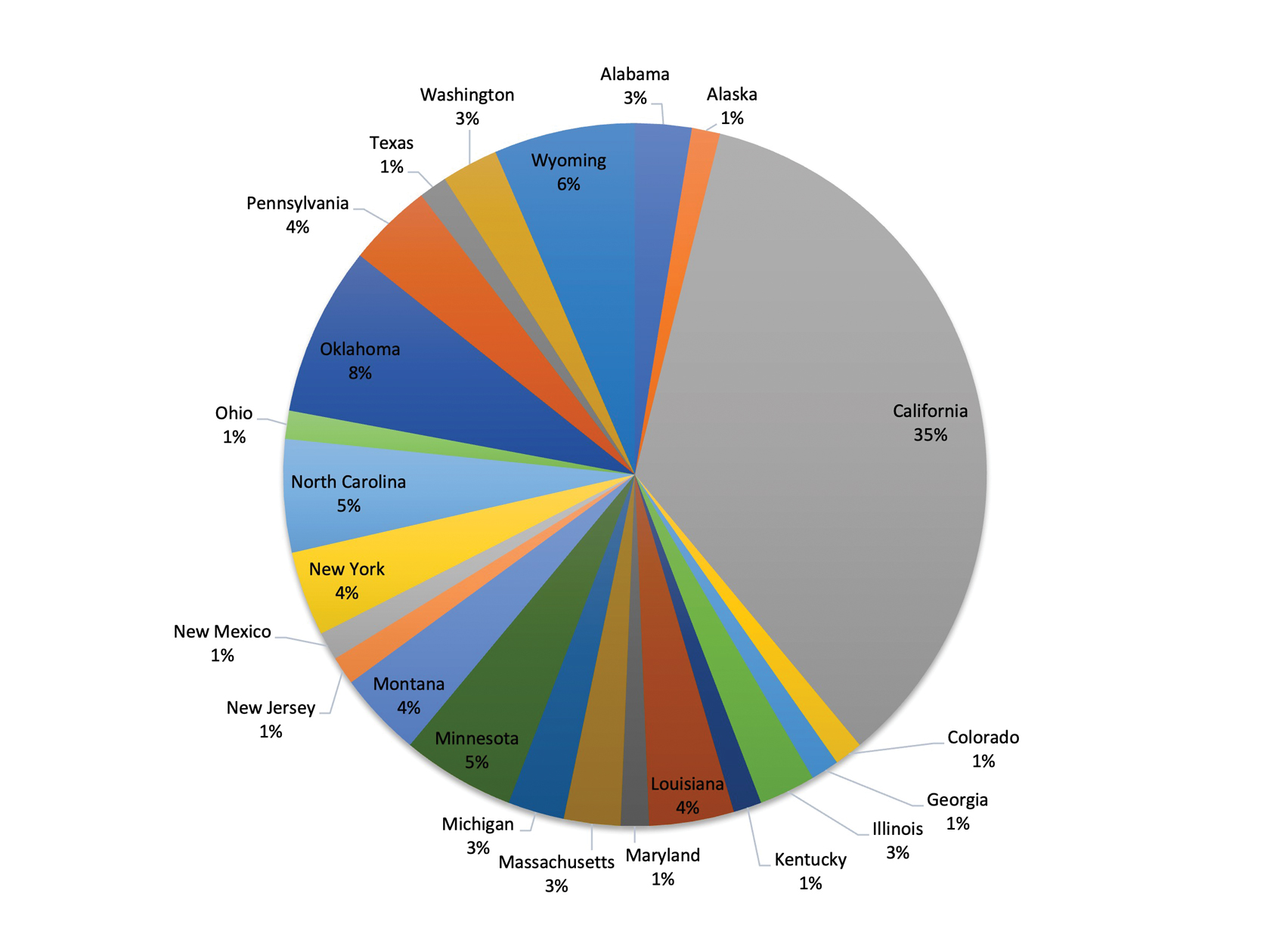

A 1-to-1 nearest neighbor propensity score (PS) matching without replacement was used to pair the 1260 veterans from the intervention group with similarly scored comparator group veterans for a PS-matched final dataset of 2520 veterans. The PS model was a multivariate logistic regression with the outcome being exposure and comparator group status. Baseline characteristics used in the PS model were age, birth sex, race, facility of care, baseline AUDIT-C score, and days between project start and scheduled appointment. Covariate imbalance for the PS-matched sample was assessed to ensure the standardized mean difference for all covariates fell under a 0.1 threshold (Figure).19

A frequency table was provided to compare the discrete distributions of the baseline characteristics in the intervention and comparator groups. Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between DTC education exposure and pharmacotherapy initiation, while controlling for potential confounders. Univariate and multivariate P value results for each variable included in the model were reported along with the multivariate odds ratios (ORs) and their associated 95% CIs. Logistic regression analyses were run for both outcomes. Each model included the exposure and comparator group status as well as the baseline characteristics included in the PS model. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.1.

RESULTS

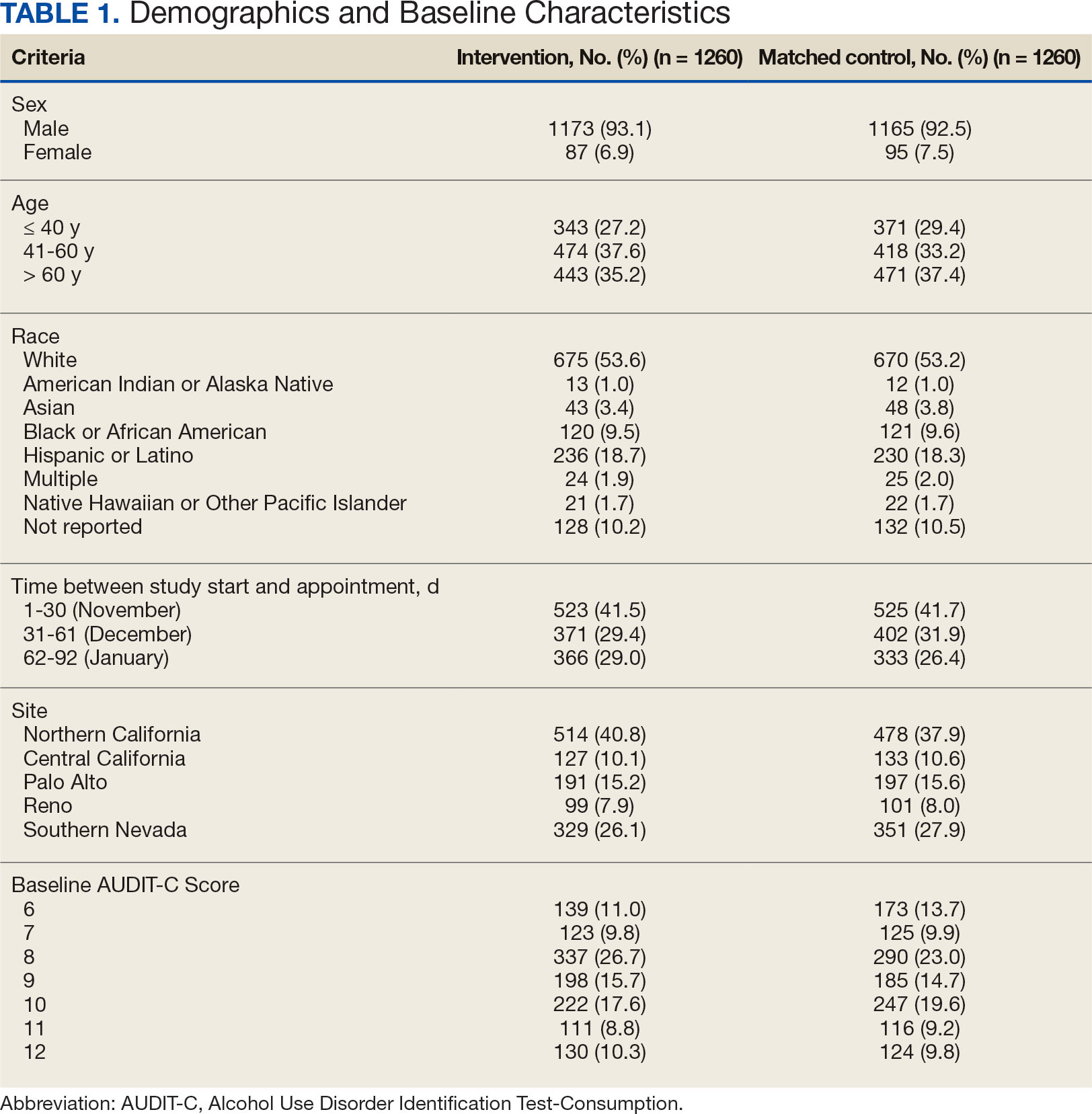

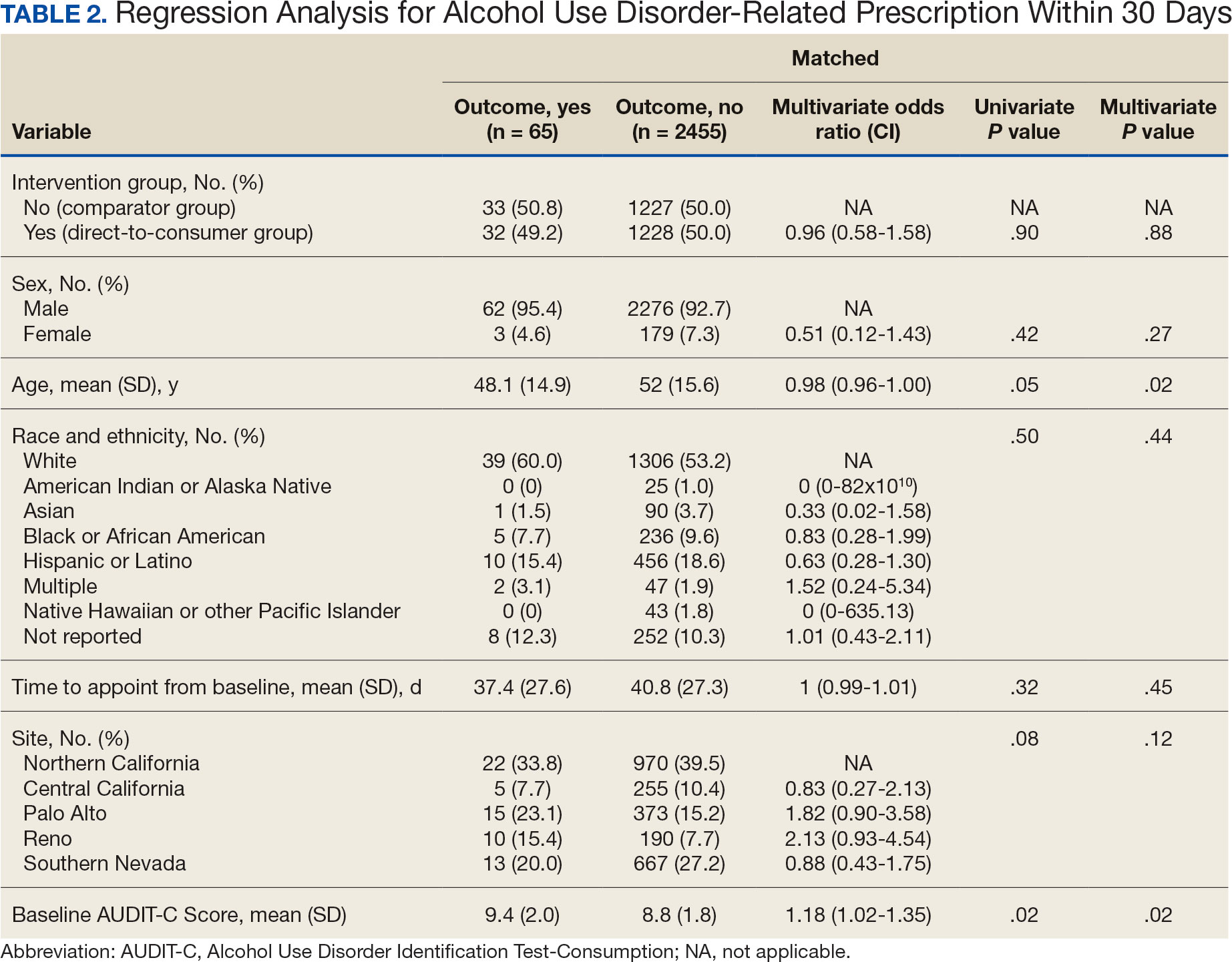

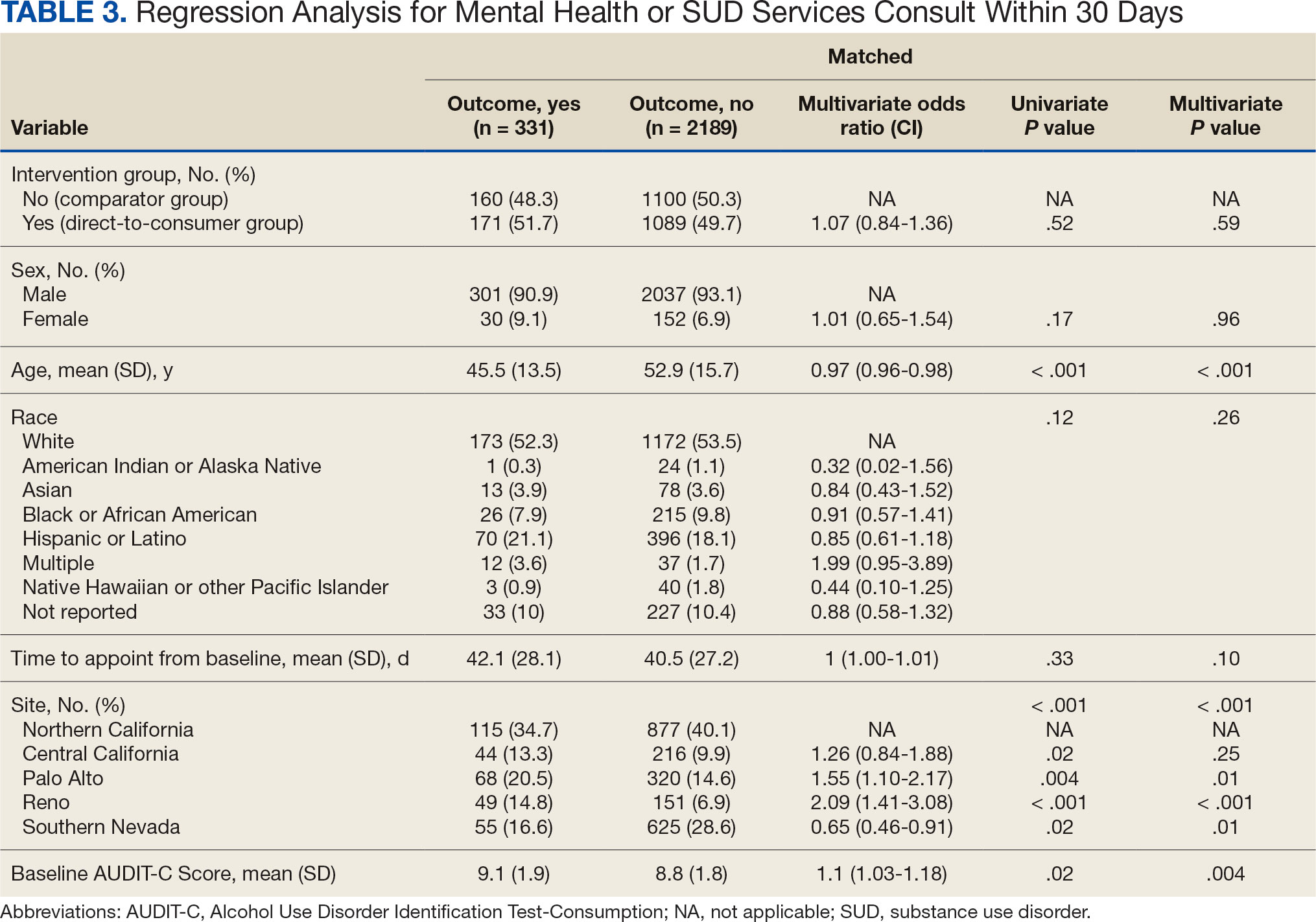

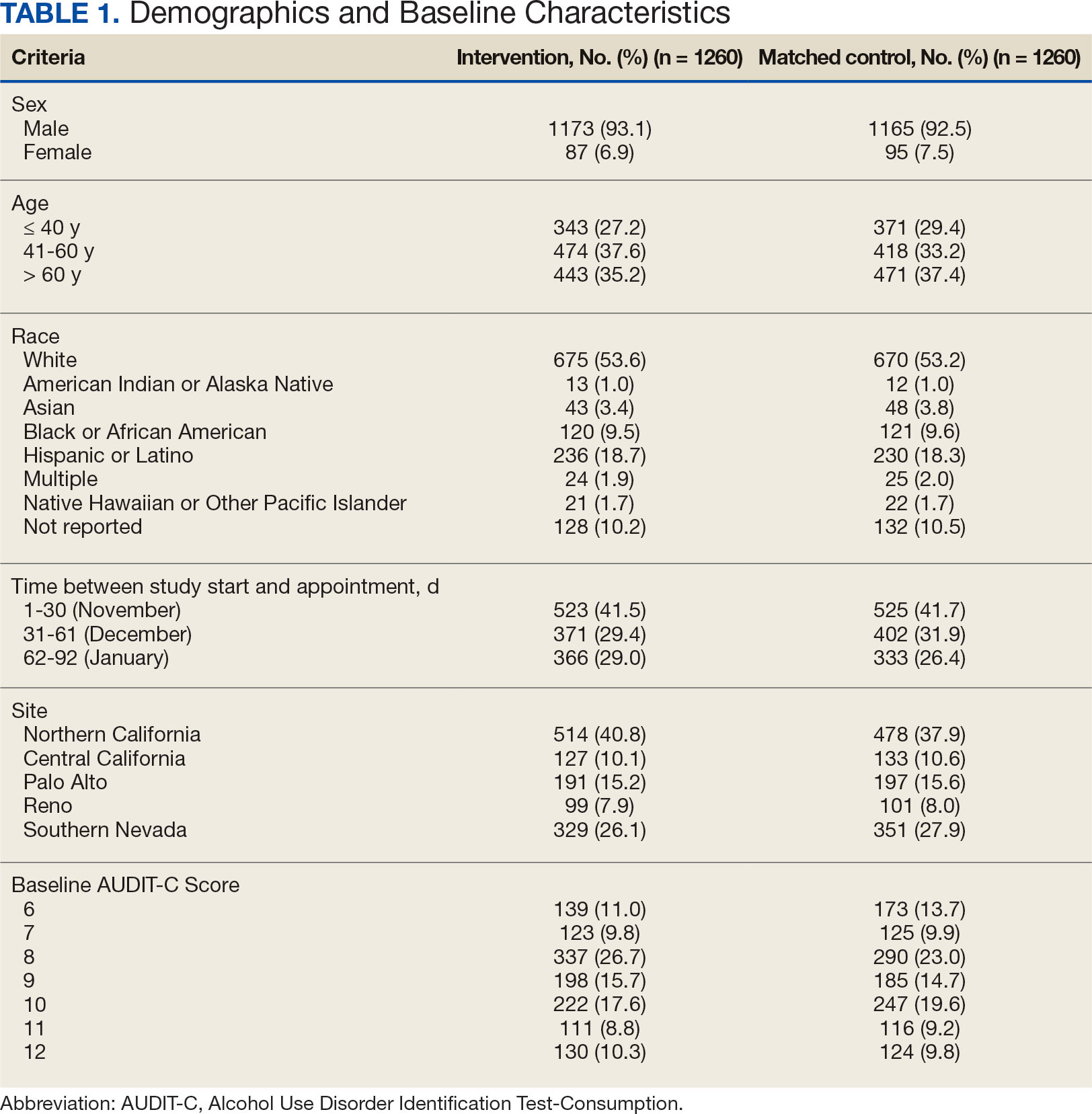

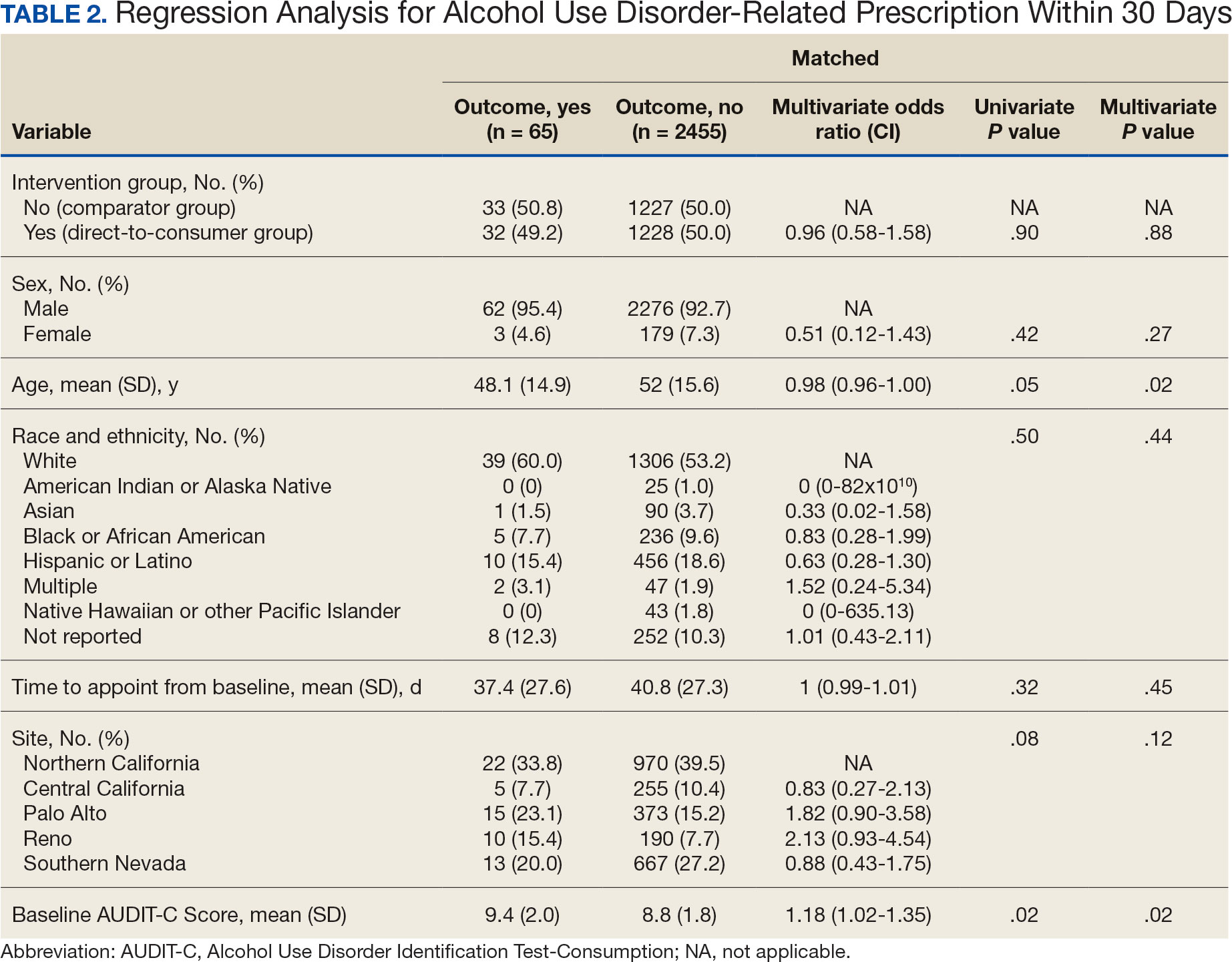

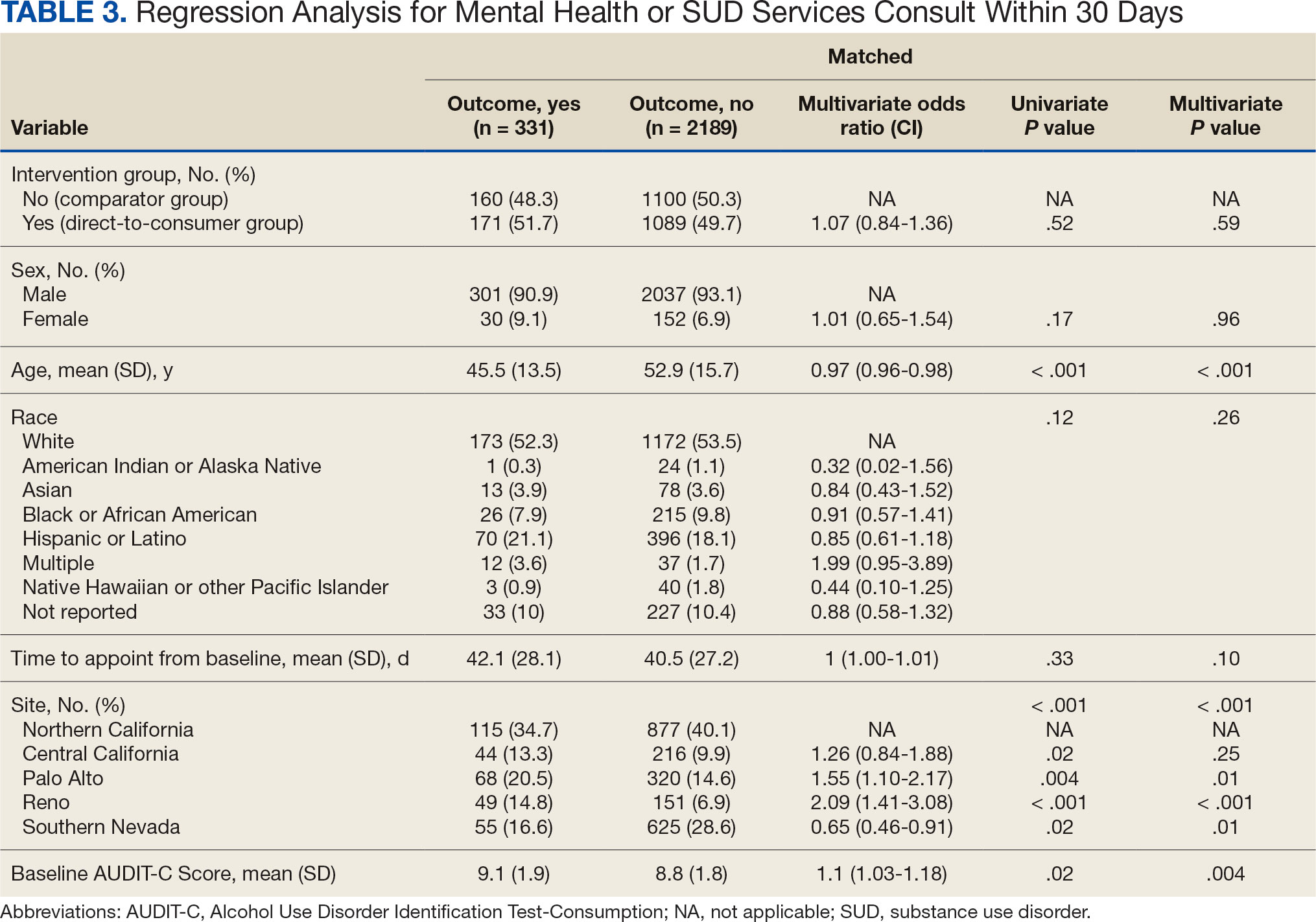

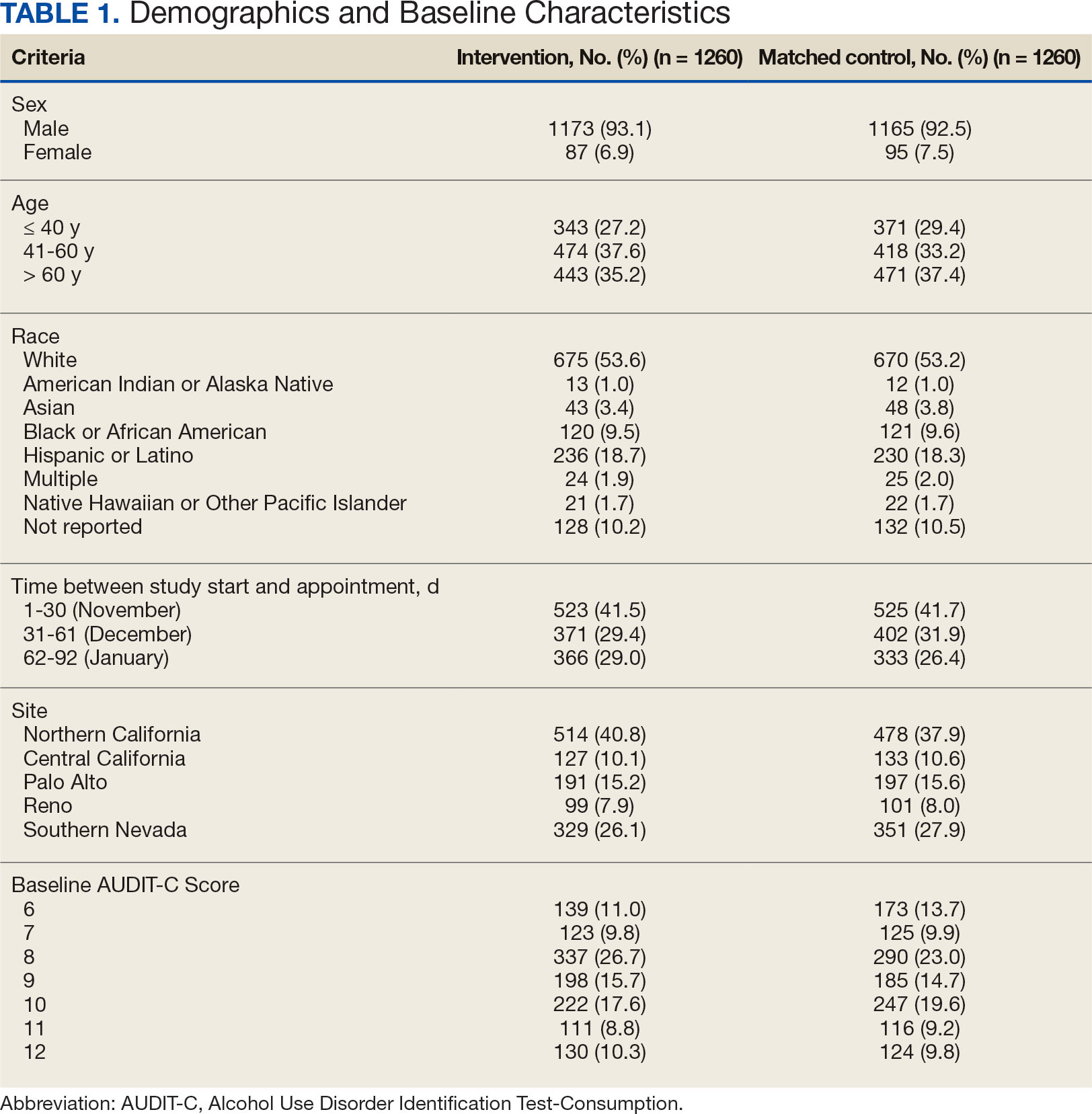

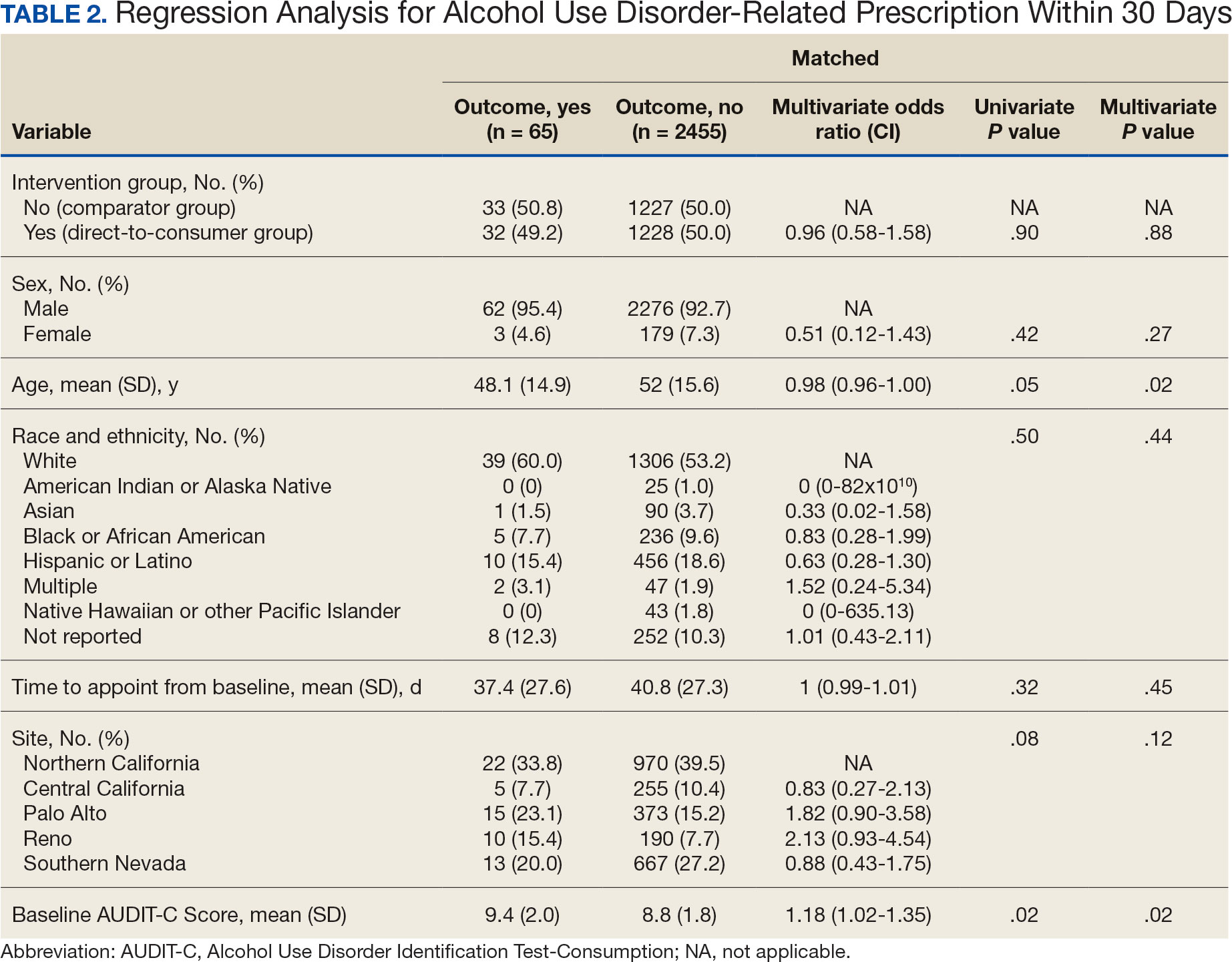

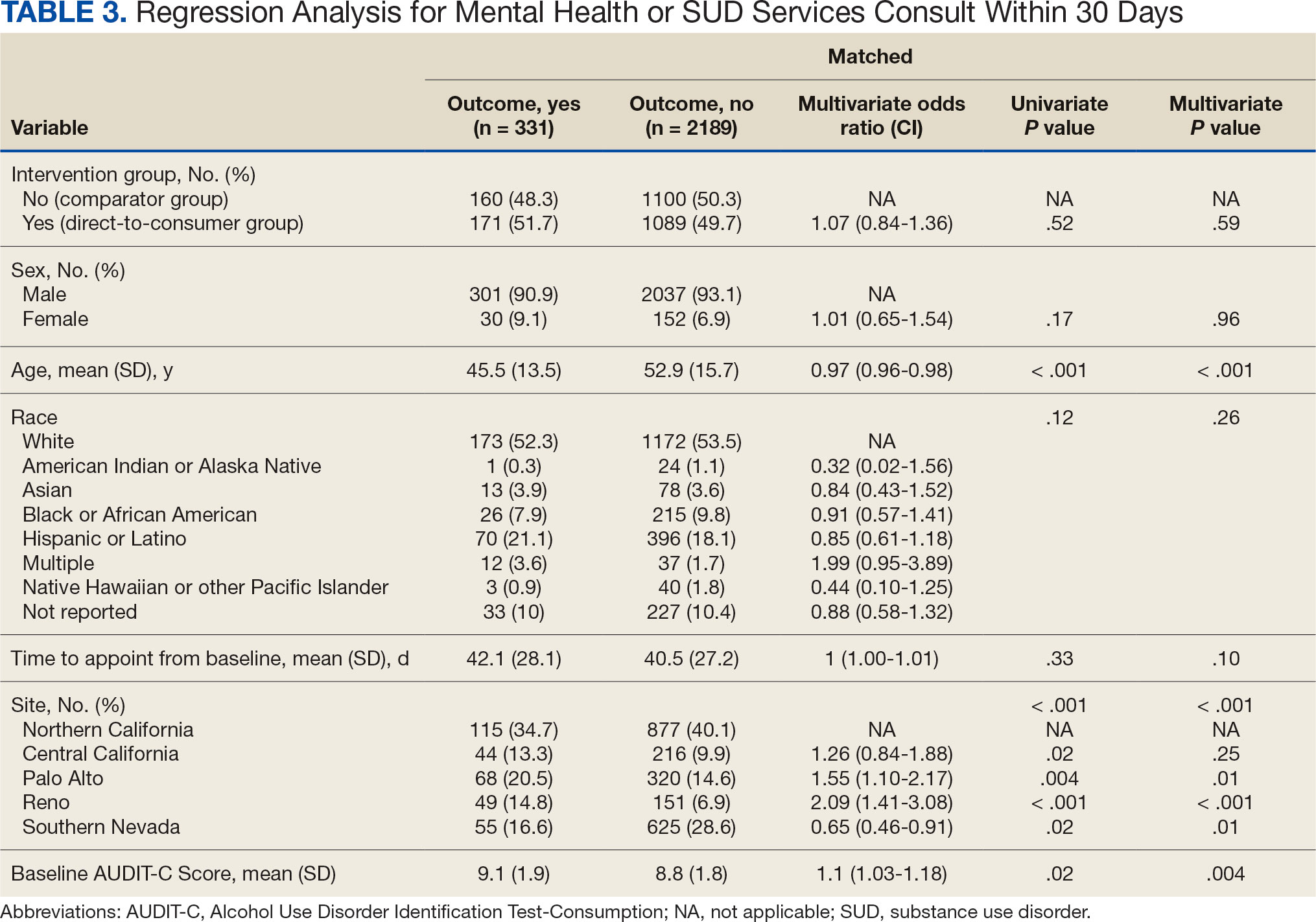

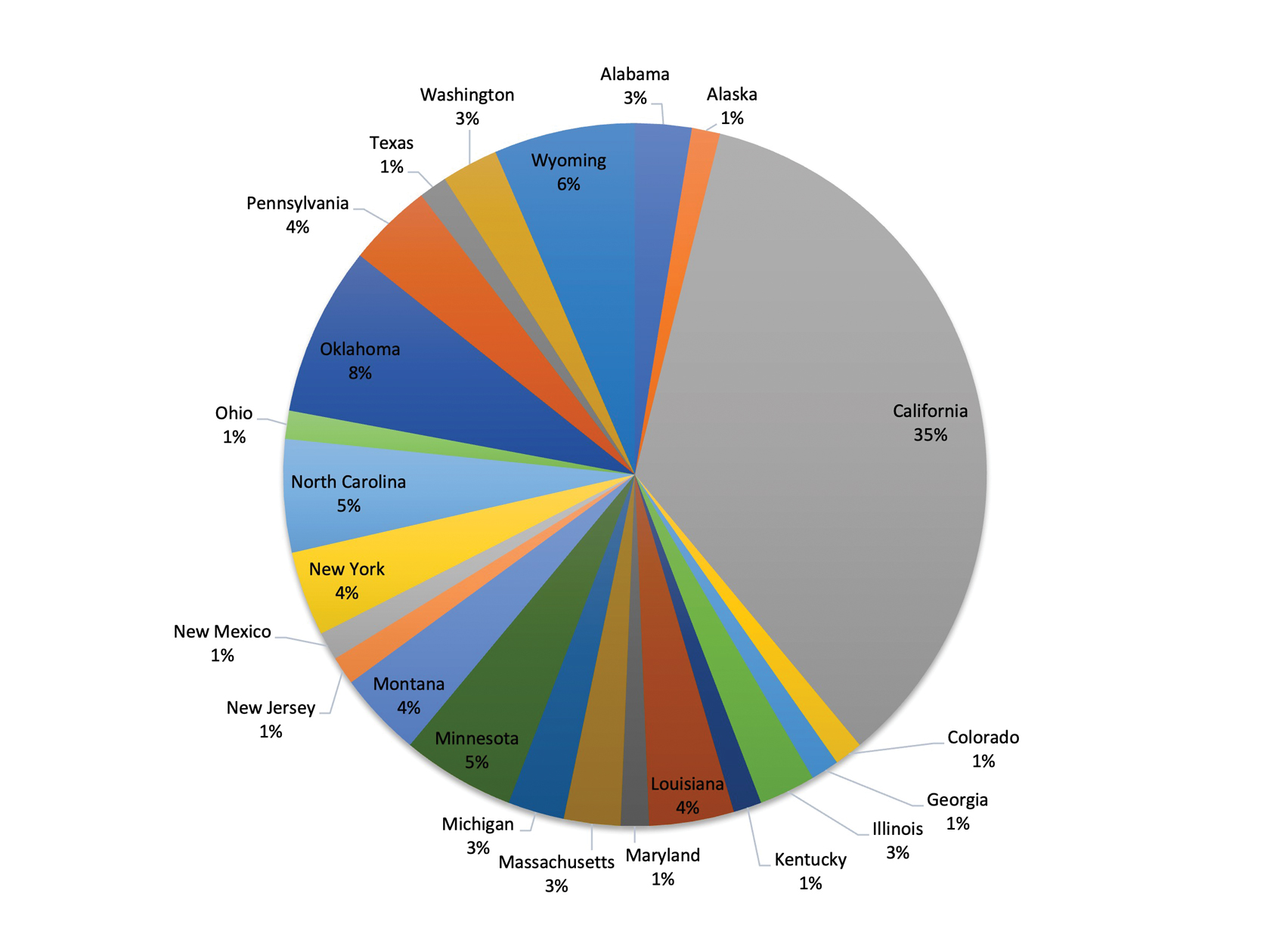

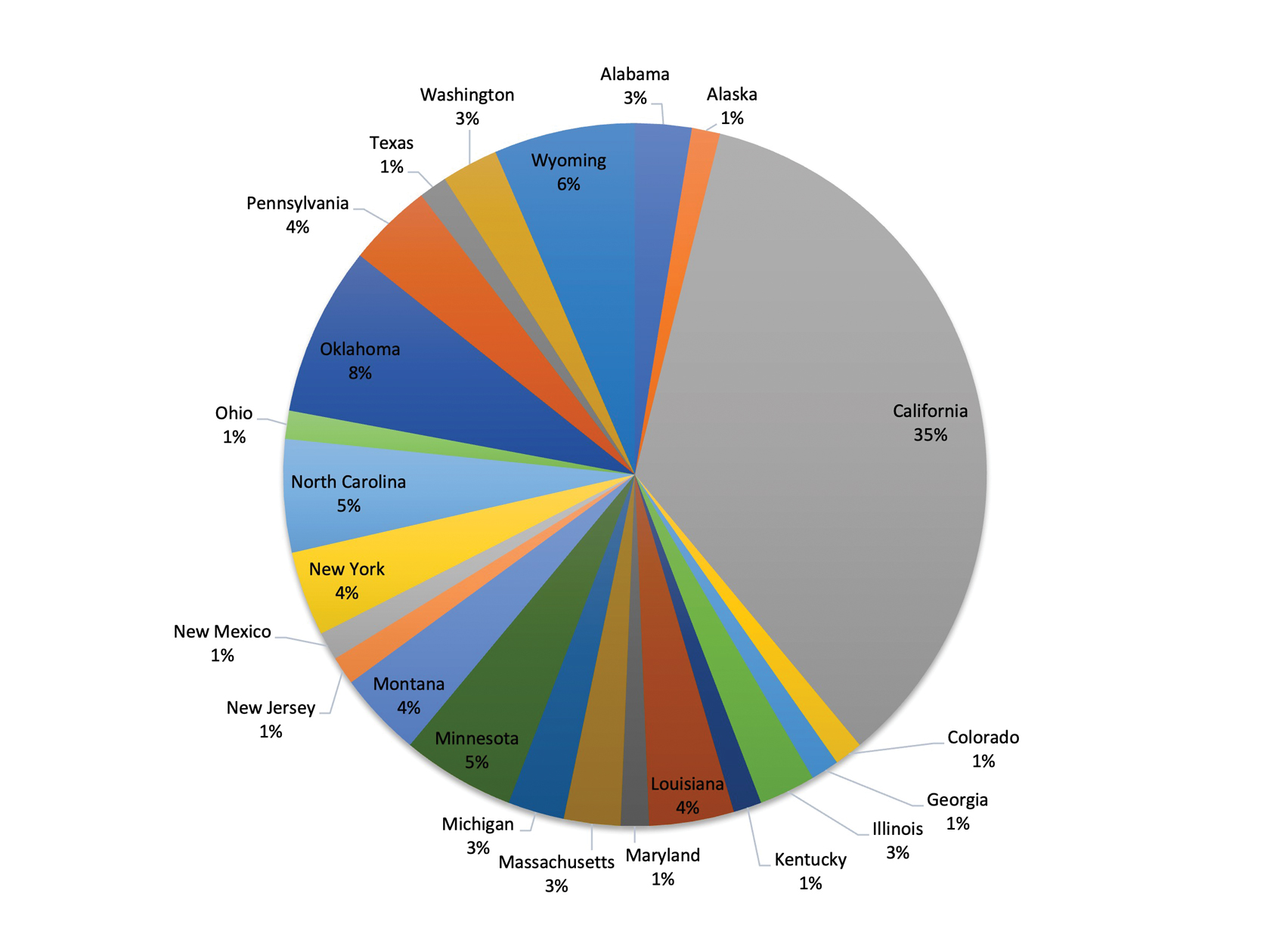

Two of 7 VISN 21 sites did not participate, and 3 had restrictions on participation. DTC education was mailed about 2 weeks prior to scheduled visit for 1260 veterans; 53.6% identified as White, 37.6% were aged 41 to 60 years, and 79.2% had an AUDIT-C ≥ 8 (Table 1). Of those mailed education, there were 173 no-show appointments (13.7%). Thirty-two veterans (2.5%) in the DTC group and 33 veterans (2.6%) in the comparator group received an AUD-related pharmacotherapy prescription (P = .88) (Table 2). One hundred seventy-one veterans (13.6%) in the DTC group and 160 veterans (12.7%) in the comparator group had a consult placed for mental health or SUD services within 30 days of their appointment (P = .59) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This project did not yield statistically significant differences in either the primary or secondary outcomes within the 30-day follow-up window and found limited impact from the DTC educational outreach to veterans. The percentage of veterans that received AUD-related pharmacotherapy or consultations for mental health or SUD services was similarly low in the DTC and comparator groups. These findings suggest that although DTC education may raise awareness, it may not be sufficient on its own to drive changes in prescribing behavior or referral patterns without system-level support.

Addiction is a complex disease faced with stigma and requiring readiness by both the HCP and patient to move forward in support and treatment. The consequences of stigma can be severe: the more stigma perceived by a person with AUD, the less likely they are to seek treatment.20 Stigma may exist even within HCPs and may lead to compromised care including shortened visits, less engagement, and less empathy.19 Cultural attitude towards alcohol use and intoxication can also be influenced through a wide range of sources including social media, movies, music, and television. Studies have shown targeted alcohol marketing may result in the development of positive beliefs about drinking and expand environments where alcohol use is socially acceptable and encouraged.21 These factors can impact drinking behavior, including the onset of drinking, binge drinking, and increased alcohol consumption.22

Three VISN 21 sites in this study had restrictions on or excluded primary care from participation. Leadership at some of these facilities were concerned that primary care teams did not have the bandwidth to take on additional items and/or there was variable primary care readiness for initiating AUD pharmacotherapy. Further attempts should be made to integrate primary care into the process of initiating AUD treatment as significant research suggests that integrated care models for AUD may be associated with improved process and outcome measures of care.23

There are several differences between this quality improvement project and prior research investigating the impact of DTC education for other conditions, such as the EMPOWER randomized controlled trial and VISN 22 project, which both demonstrated effectiveness of DTC education for reducing benzodiazepine use in geriatric veterans. 15,16 These studies focused on reducing or stopping pharmacotherapy use, whereas this project sought to promote the initiation of AUD pharmacotherapy. These studies evaluated outcomes at least 6 months postindex date, whereas this project evaluated outcomes within 30 days postappointment. Furthermore, the educational content varied significantly. Other projects provided patients with information focused on specific medications and interventions, such as benzodiazepine tapering, while this project mailed general information on heavy drinking, its risks, and strategies for cutting back, without mentioning pharmacotherapy. The DTC material used in this project was chosen because it was a preapproved national VA ADS resource, which expedited the project timeline by avoiding the need for additional approvals at each participating site. These differences may impact the observed effectiveness of DTC education in this project, especially regarding the primary outcome.

Strengths and Limitations

This quality improvement project sent a large sample of veterans DTC education in a clinical setting across multiple sites. Additionally, PS matching methods were used to balance covariates between the comparator and DTC education group, thereby simulating a randomized controlled trial and reducing selection bias. The project brought attention to the VISN 21 AUD treatment rates, stimulated conversation across sites about available treatments and resources for AUD, and sparked collaboration between academic detailing, mental health, and primary care services. The time frame for visits was selected during the winter; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism notes this is a time when people may be more likely to engage in excessive alcohol consumption than at other times of the year.24

The 30-day time frame for outcomes may have been too short to observe changes in prescribing or referral patterns. Additionally, the comparator group was comprised of veterans seen from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023, where seasonal timing may have influenced alcohol consumption behaviors and skewed the results. There were also no-show appointments in the DTC education group (13.7%), though it is likely some patients rescheduled and still received AUD pharmacotherapy within 30 days of the original appointment. Finally, it was not possible to confirm whether a patient opened and read the education that was mailed to them. This may be another reason to explore electronic distribution of DTC education. This all may have contributed to the lack of statistically significant differences in both the primary and secondary outcomes.

There was a high level of variability between facility participation in the project. Two of 7 sites did not participate, and 3 sites restricted primary care engagement. This represents a significant limitation, particularly for the secondary outcome of placing consultations for MH or SUD services. Facilities that only included mental health or SUD HCPs may have resulted in lower consultation rates due to their inherent specialization, reducing the likelihood of self-referrals.

The project may overestimate prescribed AUD pharmacotherapy in the primary outcome due to potential misclassification of medications. While the project adhered to the national VA ADS AUD dashboard’s definition of AUD pharmacotherapy, including acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, topiramate, and gabapentin, some of these medications have multiple indications. For example, gabapentin is commonly prescribed for peripheral neuropathy, and topiramate is used to treat migraines and seizures. The multipurpose use adds uncertainty about whether they were prescribed specifically for AUD treatment, especially in cases where the HCP is responsible for treating a broad range of disease states, as in primary care.

CONCLUSIONS

Results of this quality improvement project did not show a statistically significant difference between patients sent DTC education and the comparator group for the initiation of AUD pharmacotherapy or placement of a consult to mental health or SUD services within 30 days of their scheduled visit. Future studies may seek to implement stricter criteria to confirm the intended use of topiramate and gabapentin, such as looking for keywords in the prescription instructions for use, performing chart reviews, and/or only including these medications if prescribed by a mental health or SUD HCP. Alternatively, future studies may consider limiting the analysis to only FDA-approved AUD medications: acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone. It is vital to continue to enhance primary care HCP readiness to treat AUD, given the existing relationships and trust they often have with patients. Electronic methods for distributing DTC education could also be advantageous, as these methods may have the ability to track whether a message has been opened and read. Despite a lack of statistical significance, this project sparked crucial conversations and collaboration around AUD, available treatments, and addressing potential barriers to connecting patients to care within VISN 21.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about U.S. deaths from excessive alcohol use. August 6, 2024. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/facts-stats/

- State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Escalating alcohol-involved death rates: trends and variation across the nation and in the states from 2006 to 2019. April 19, 2021. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.shadac.org/escalating-alcohol-involved-death-rates-trends-and-variation-across-nation-and-states-2006-2019

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol- related emergencies and deaths in the United States. Updated November 2024. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-related-emergencies-and-deaths-united-states

- Esser MB, Sherk A, Liu Y, Naimi TS. Deaths from excessive alcohol use - United States, 2016- 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(8):154-161. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7308a1

- Canver BR, Newman RK, Gomez AE. Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol treatment in the United States. Updated January 2025. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-treatment-united-states

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) in the United States: age groups and demographic characteristics. Updated September 2024. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-use-disorder-aud-united-states-age-groups-and-demographic-characteristics

- Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(1):86-90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.1750101

- Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, Finney JW. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488. doi:10.1111/acer.12411

- Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x

- Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3628

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. August 2021. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADODSUDCPG.pdf

- Ranney RM, Bernhard PA, Vogt D, et al. Alcohol use and treatment utilization in a national sample of veterans and nonveterans. J Subst Use Addict Treat. 2023;146:208964. doi:10.1016/j.josat.2023.208964

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefit Management Service, Academic Detailing Service. AUD Trend Report. https://vaww.pbi.cdw.va.gov/PBIRS/Pages/ReportViewer.aspx?/GPE/PBM_AD/SSRS/AUD/AUD_TrendReport

- Mendes MA, Smith JP, Marin JK, et al. Reducing benzodiazepine prescribing in older veterans: a direct-to-consumer educational brochure. Fed Pract. 2018;35(9):36-43.

- Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-898. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949

- Maloney R, Funmilayo M. Acting on the AUDIT-C: implementation of direct-to-consumer education on unhealth alcohol use. Presented on March 31, 2023; Central Virginia Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Richmond, Virginia.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefit Management Service. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) – leading the charge in the treatment of AUD: a VA clinician’s guide. February 2022. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/AcademicDetailingService/Documents/508/10-1530_AUD_ClinicianGuide_508Conformant.pdf

- Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424. doi:10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Stigma: overcoming a pervasive barrier to optimal care. Updated January 6, 2025. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/health-professionals-communities/core-resource-on-alcohol/stigma-overcoming-pervasive-barrier-optimal-care

- Sudhinaraset M, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and cultural contexts of alcohol use: influences in a socialecological framework. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):35-45.

- Tanski SE, McClure AC, Li Z, et al. Cued recall of alcohol advertising on television and underage drinking behavior. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):264-271. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3345

- Hyland CJ, McDowell MJ, Bain PA, Huskamp HA, Busch AB. Integration of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder treatment in primary care settings: a scoping review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2023;144:108919. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108919

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The truth about holiday spirits. Updated November 2023. Accessed February 5, 2025. ,a href="https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/truth-about-holiday-spirits">https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/truth-about-holiday-spirits

Excessive alcohol use is one of the leading preventable causes of death in the United States, responsible for about 178,000 deaths annually and an average of 488 daily deaths in 2020 and 2021.1Alcohol-related deaths increased by 49% between 2006 and 2019.2 This trend continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, with death certificates that listed alcohol increasing by > 25% from 2019 to 2020, and another 10% in 2021.3 This increase of alcohol-related deaths includes those as a direct result of chronic alcohol use, such as alcoholic cardiomyopathy, alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, and alcohol-induced pancreatitis, as well as a result of acute use such as alcohol poisoning, suicide by exposure to alcohol, and alcohol-impaired driving fatalities.4

Excessive alcohol consumption poses other serious risks, including cases when intake is abruptly reduced without proper management. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) can vary in severity, with potentially life-threatening complications such as hallucinations, seizures, and delirium tremens.5

These risks highlight the importance of professional intervention and support, not only to mitigate risks associated with AWS, but provide a pathway towards recovery from alcohol use disorder (AUD).

According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 28.8 million US adults had AUD in the prior year, yet only 7.6% of these individuals received treatment and an even smaller group (2.2%) received medication-assisted treatment for alcohol.6,7 This is despite American Psychiatric Association guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of patients with AUD, including the use of naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, topiramate, or gabapentin, depending on therapy goals, past medication trials, medication contraindications, and patient preference.8 Several of these medications are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AUD and have support for effectiveness from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses.9-11

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of substance use disorders (SUDs) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and US Department of Defense have strong recommendations for naltrexone and topiramate as first-line pharmacotherapies for moderate to severe AUD. Acamprosate and disulfiram are weak recommendations as alternative options. Gabapentin is a weak recommendation for cases where first-line treatments are contraindicated or ineffective. The guidelines emphasize the importance of a comprehensive approach to AUD treatment, including psychosocial interventions in addition to pharmacotherapy.12

A 2023 national survey found veterans reported higher alcohol consumption than nonveterans.13 At the end of fiscal year 2023, > 4.4 million veterans—6% of Veterans Health Administration patients—had been diagnosed with AUD.14 However, > 87% of these patients nationally, and 88% of Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 21 patients, were not receiving naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, or topiramate as part of their treatment. The VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) now includes AUD pharmacotherapy as a campaign focus, highlighting its importance. The ADS is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote aligning prescribing behavior with best practices. Academic detailing methods include speaking with health care practitioners (HCPs), and direct-to-consumer (DTC) patient education.

ADS campaigns include DTC educational handouts. Past ADS projects and research using DTC have demonstrated a significant improvement in outcomes and positively influencing patients’ pharmacotherapy treatment. 15,16 A VA quality improvement project found a positive correlation between the initiation of AUD pharmacotherapy and engagement with mental health care following the distribution of AUD DTC patient education. 17 This project aimed to apply the same principles of prior research to explore the use of DTC across multiple facilities within VISN 21 to increase AUD pharmacotherapy. VISN 21 includes VA facilities and clinics across the Pacific Islands, Nevada, and California and serves about 350,000 veterans.

METHODS

A prospective cohort of VISN 21 veterans with or at high risk for AUD was identified using the VA ADS AUD Dashboard. The cohort included those not on acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, topiramate, or gabapentin for treatment of AUD and had an elevated Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) score of ≥ 6 (high risk) with an AUD diagnosis or ≥ 8 (severe risk) without a diagnosis. The AUDIT-C scores used in the dashboard are supported by the VA AUD clinician guide as the minimum scores when AUD pharmacotherapy should be offered to patients.18 Prescriptions filled outside the VA were not included in this dashboard.

Data and patient information were collected using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. To be eligible, veterans needed a valid mailing address within the VISN 21 region and a primary care, mental health, or SUD clinician prescriber visit scheduled between October 1, 2023, and January 31, 2024. Veterans were excluded if they were in hospice, had a 1-year mortality risk score > 50% based on their Care Assessment Need (CAN) score, or facility leadership opted out of project involvement. Patients with both severe renal and hepatic impairments were excluded because they were ineligible for AUD pharmacotherapy. However, veterans with either renal or hepatic impairment (but not both) were included, as they could be potential candidates for ≥ 1 AUD pharmacotherapy option.

Initial correspondence with facilities was initiated through local academic detailers. A local champion was identified for the 1 facility without an academic detailer. Facilities could opt in or out of the project. Approval was provided by the local pharmacy and therapeutics committee, pharmacy, primary care, or psychiatry leadership. Approval process and clinician involvement varied by site.

Education

The selected AUD patient education was designed and approved by the national VA ADS (eappendix). The DTC patient education provided general knowledge about alcohol, including what constitutes a standard amount of alcohol, what is considered heavy drinking, risks of heavy drinking, creating a plan with a clinician to reduce and manage withdrawal symptoms, and additional resources. The DTC was accompanied by a cover letter that included a local facility contact number.

A centralized mailing facility was used for all materials. VA Northern California Health Care System provided the funding to cover the cost of postage. The list of veterans to be contacted was updated on a rolling basis and DTC education was mailed 2 weeks prior to their scheduled prescriber visit.

The eligible cohort of 1260 veterans received DTC education. A comparator group of 2048 veterans that did not receive DTC education was obtained retrospectively by using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria with a scheduled primary care, mental health, or SUD HCP visit from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023. The outcomes assessed were within 30 days of the scheduled visit, with the primary outcome as the initiation of AUD-related pharmacotherapy and the secondary outcome as the placement of a consultation for mental health or SUD services. Any consultations sent to Behavioral Health, Addiction, Mental Health, Psychiatric, and SUD services following the HCP visit, within the specified time frame, were used for the secondary outcome.

Matching and Analysis

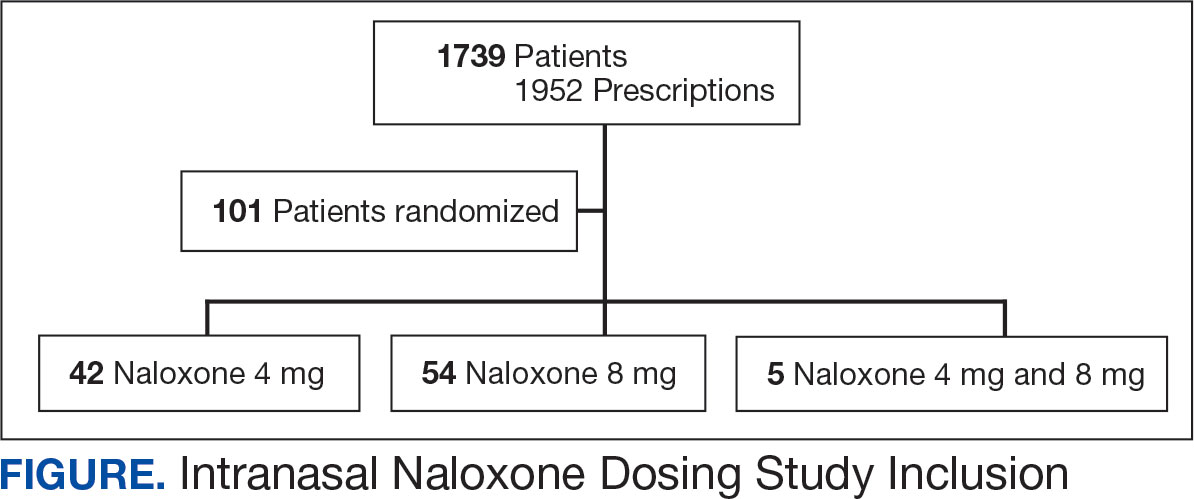

A 1-to-1 nearest neighbor propensity score (PS) matching without replacement was used to pair the 1260 veterans from the intervention group with similarly scored comparator group veterans for a PS-matched final dataset of 2520 veterans. The PS model was a multivariate logistic regression with the outcome being exposure and comparator group status. Baseline characteristics used in the PS model were age, birth sex, race, facility of care, baseline AUDIT-C score, and days between project start and scheduled appointment. Covariate imbalance for the PS-matched sample was assessed to ensure the standardized mean difference for all covariates fell under a 0.1 threshold (Figure).19

A frequency table was provided to compare the discrete distributions of the baseline characteristics in the intervention and comparator groups. Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between DTC education exposure and pharmacotherapy initiation, while controlling for potential confounders. Univariate and multivariate P value results for each variable included in the model were reported along with the multivariate odds ratios (ORs) and their associated 95% CIs. Logistic regression analyses were run for both outcomes. Each model included the exposure and comparator group status as well as the baseline characteristics included in the PS model. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.1.

RESULTS

Two of 7 VISN 21 sites did not participate, and 3 had restrictions on participation. DTC education was mailed about 2 weeks prior to scheduled visit for 1260 veterans; 53.6% identified as White, 37.6% were aged 41 to 60 years, and 79.2% had an AUDIT-C ≥ 8 (Table 1). Of those mailed education, there were 173 no-show appointments (13.7%). Thirty-two veterans (2.5%) in the DTC group and 33 veterans (2.6%) in the comparator group received an AUD-related pharmacotherapy prescription (P = .88) (Table 2). One hundred seventy-one veterans (13.6%) in the DTC group and 160 veterans (12.7%) in the comparator group had a consult placed for mental health or SUD services within 30 days of their appointment (P = .59) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This project did not yield statistically significant differences in either the primary or secondary outcomes within the 30-day follow-up window and found limited impact from the DTC educational outreach to veterans. The percentage of veterans that received AUD-related pharmacotherapy or consultations for mental health or SUD services was similarly low in the DTC and comparator groups. These findings suggest that although DTC education may raise awareness, it may not be sufficient on its own to drive changes in prescribing behavior or referral patterns without system-level support.

Addiction is a complex disease faced with stigma and requiring readiness by both the HCP and patient to move forward in support and treatment. The consequences of stigma can be severe: the more stigma perceived by a person with AUD, the less likely they are to seek treatment.20 Stigma may exist even within HCPs and may lead to compromised care including shortened visits, less engagement, and less empathy.19 Cultural attitude towards alcohol use and intoxication can also be influenced through a wide range of sources including social media, movies, music, and television. Studies have shown targeted alcohol marketing may result in the development of positive beliefs about drinking and expand environments where alcohol use is socially acceptable and encouraged.21 These factors can impact drinking behavior, including the onset of drinking, binge drinking, and increased alcohol consumption.22

Three VISN 21 sites in this study had restrictions on or excluded primary care from participation. Leadership at some of these facilities were concerned that primary care teams did not have the bandwidth to take on additional items and/or there was variable primary care readiness for initiating AUD pharmacotherapy. Further attempts should be made to integrate primary care into the process of initiating AUD treatment as significant research suggests that integrated care models for AUD may be associated with improved process and outcome measures of care.23

There are several differences between this quality improvement project and prior research investigating the impact of DTC education for other conditions, such as the EMPOWER randomized controlled trial and VISN 22 project, which both demonstrated effectiveness of DTC education for reducing benzodiazepine use in geriatric veterans. 15,16 These studies focused on reducing or stopping pharmacotherapy use, whereas this project sought to promote the initiation of AUD pharmacotherapy. These studies evaluated outcomes at least 6 months postindex date, whereas this project evaluated outcomes within 30 days postappointment. Furthermore, the educational content varied significantly. Other projects provided patients with information focused on specific medications and interventions, such as benzodiazepine tapering, while this project mailed general information on heavy drinking, its risks, and strategies for cutting back, without mentioning pharmacotherapy. The DTC material used in this project was chosen because it was a preapproved national VA ADS resource, which expedited the project timeline by avoiding the need for additional approvals at each participating site. These differences may impact the observed effectiveness of DTC education in this project, especially regarding the primary outcome.

Strengths and Limitations

This quality improvement project sent a large sample of veterans DTC education in a clinical setting across multiple sites. Additionally, PS matching methods were used to balance covariates between the comparator and DTC education group, thereby simulating a randomized controlled trial and reducing selection bias. The project brought attention to the VISN 21 AUD treatment rates, stimulated conversation across sites about available treatments and resources for AUD, and sparked collaboration between academic detailing, mental health, and primary care services. The time frame for visits was selected during the winter; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism notes this is a time when people may be more likely to engage in excessive alcohol consumption than at other times of the year.24

The 30-day time frame for outcomes may have been too short to observe changes in prescribing or referral patterns. Additionally, the comparator group was comprised of veterans seen from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023, where seasonal timing may have influenced alcohol consumption behaviors and skewed the results. There were also no-show appointments in the DTC education group (13.7%), though it is likely some patients rescheduled and still received AUD pharmacotherapy within 30 days of the original appointment. Finally, it was not possible to confirm whether a patient opened and read the education that was mailed to them. This may be another reason to explore electronic distribution of DTC education. This all may have contributed to the lack of statistically significant differences in both the primary and secondary outcomes.

There was a high level of variability between facility participation in the project. Two of 7 sites did not participate, and 3 sites restricted primary care engagement. This represents a significant limitation, particularly for the secondary outcome of placing consultations for MH or SUD services. Facilities that only included mental health or SUD HCPs may have resulted in lower consultation rates due to their inherent specialization, reducing the likelihood of self-referrals.

The project may overestimate prescribed AUD pharmacotherapy in the primary outcome due to potential misclassification of medications. While the project adhered to the national VA ADS AUD dashboard’s definition of AUD pharmacotherapy, including acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone, topiramate, and gabapentin, some of these medications have multiple indications. For example, gabapentin is commonly prescribed for peripheral neuropathy, and topiramate is used to treat migraines and seizures. The multipurpose use adds uncertainty about whether they were prescribed specifically for AUD treatment, especially in cases where the HCP is responsible for treating a broad range of disease states, as in primary care.

CONCLUSIONS