User login

Smooth Papules on the Left Hand

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

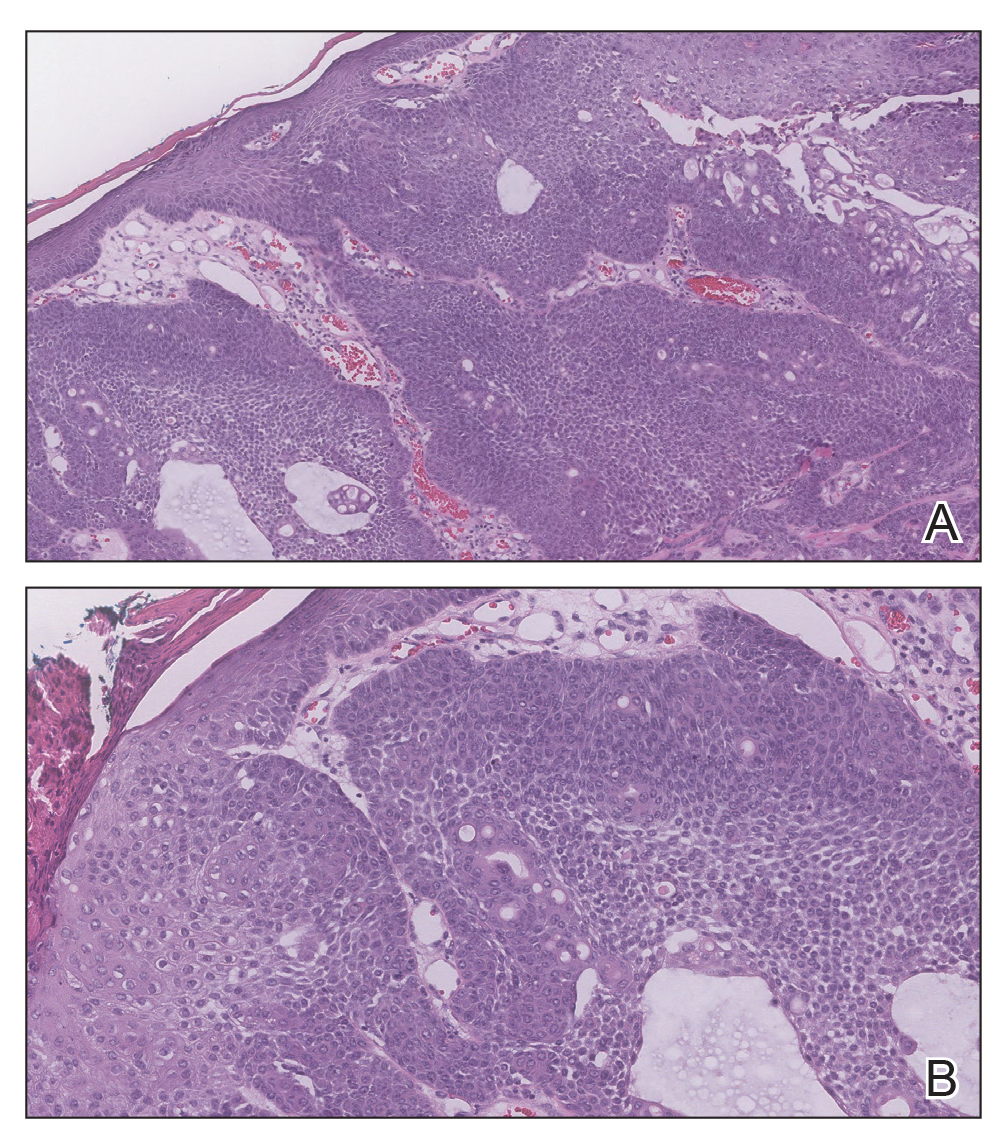

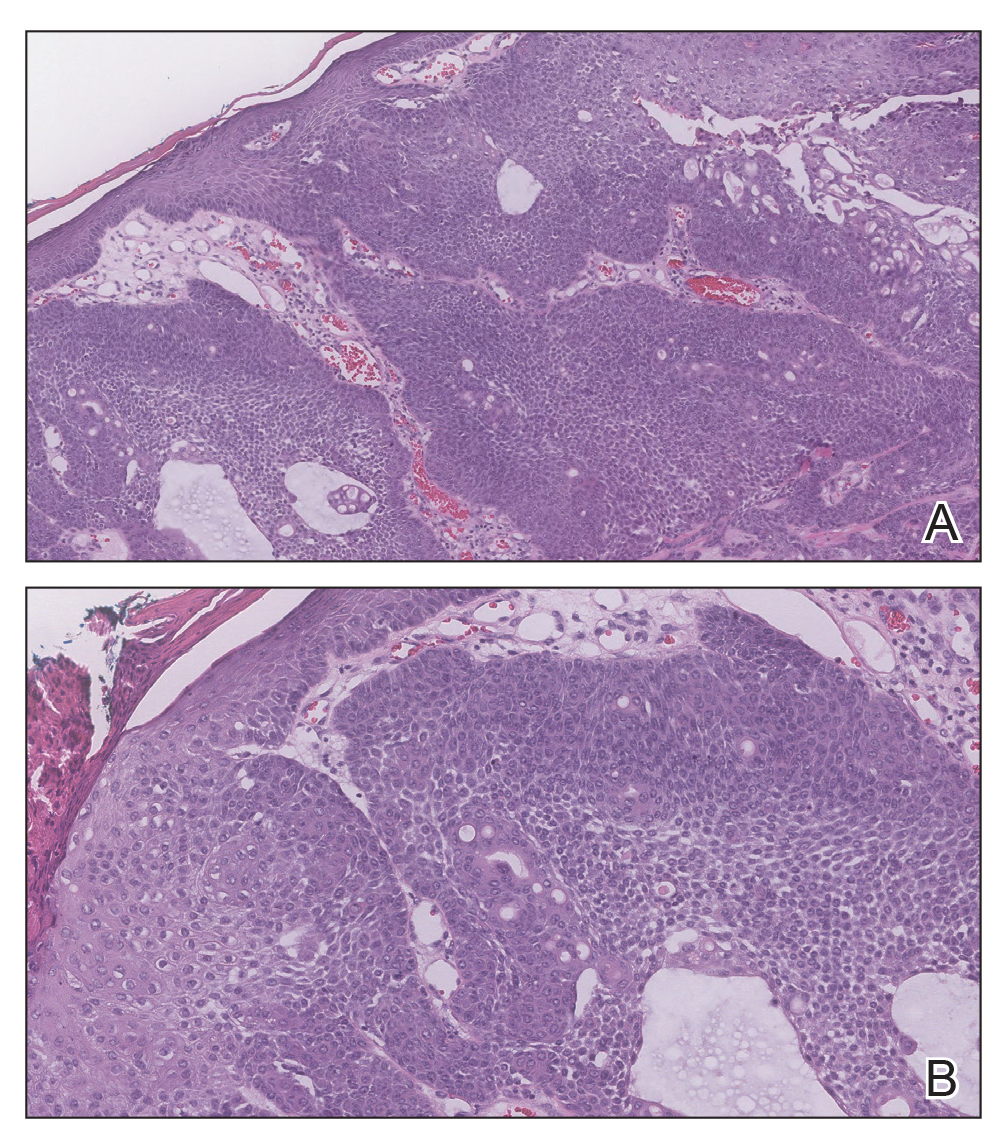

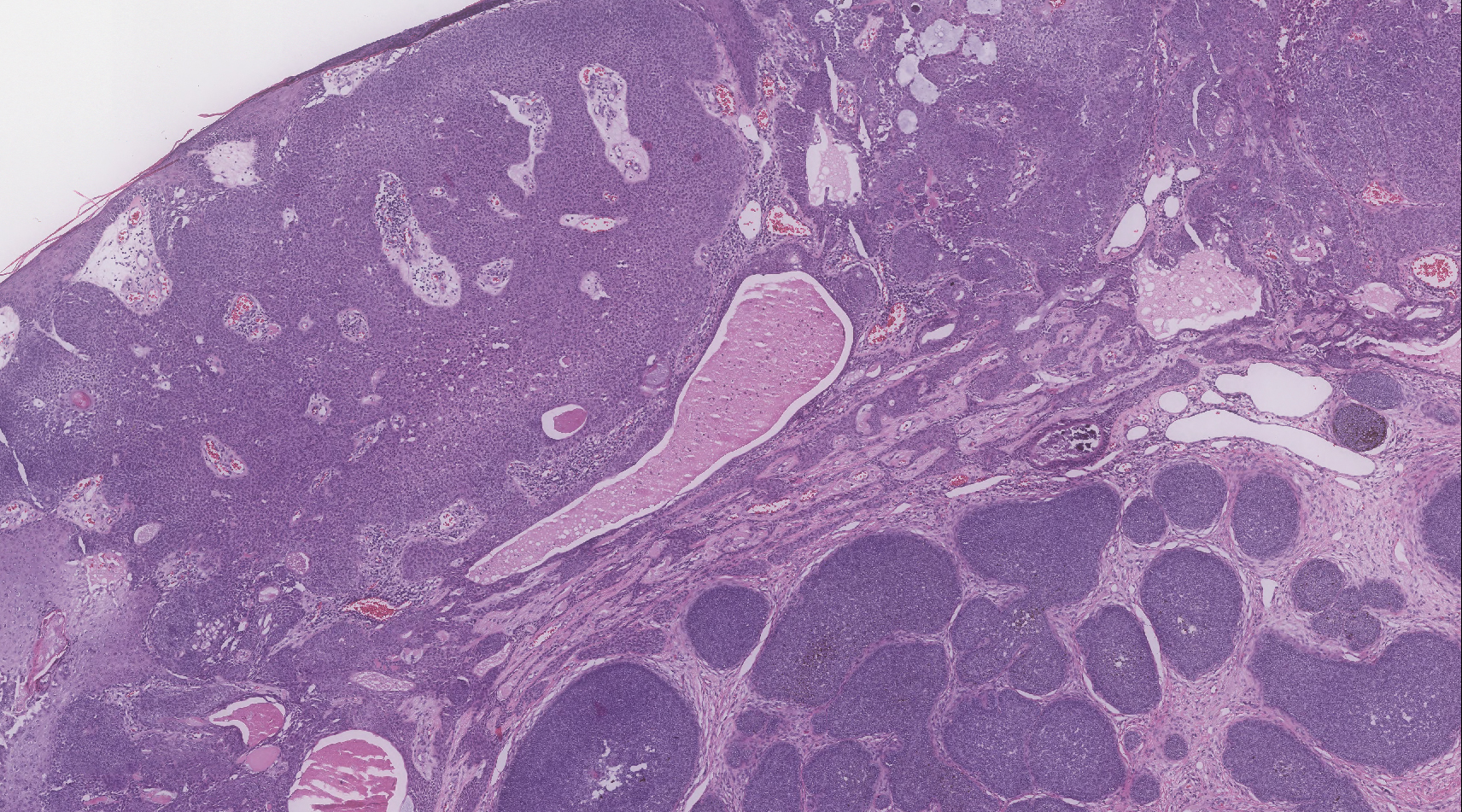

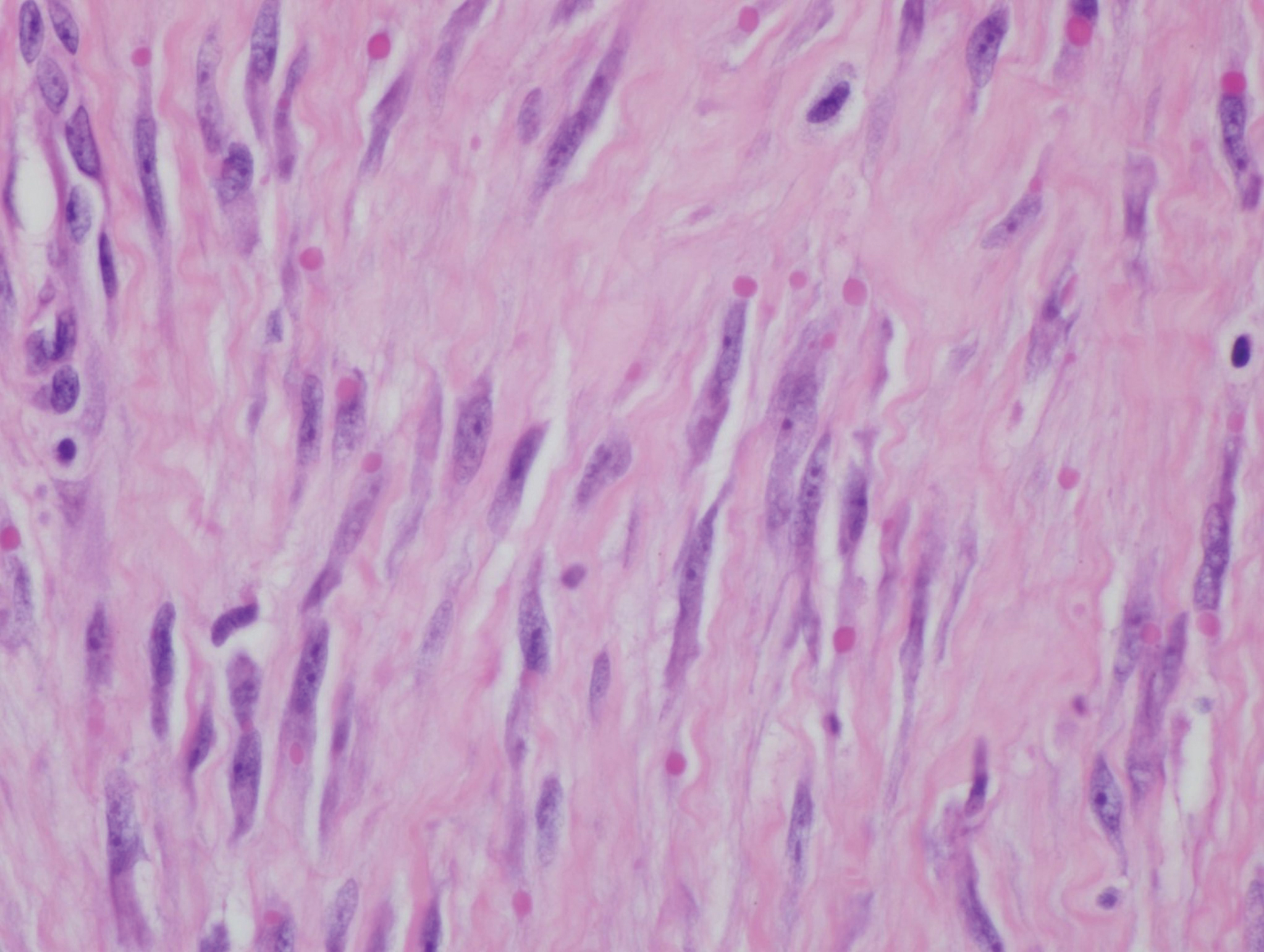

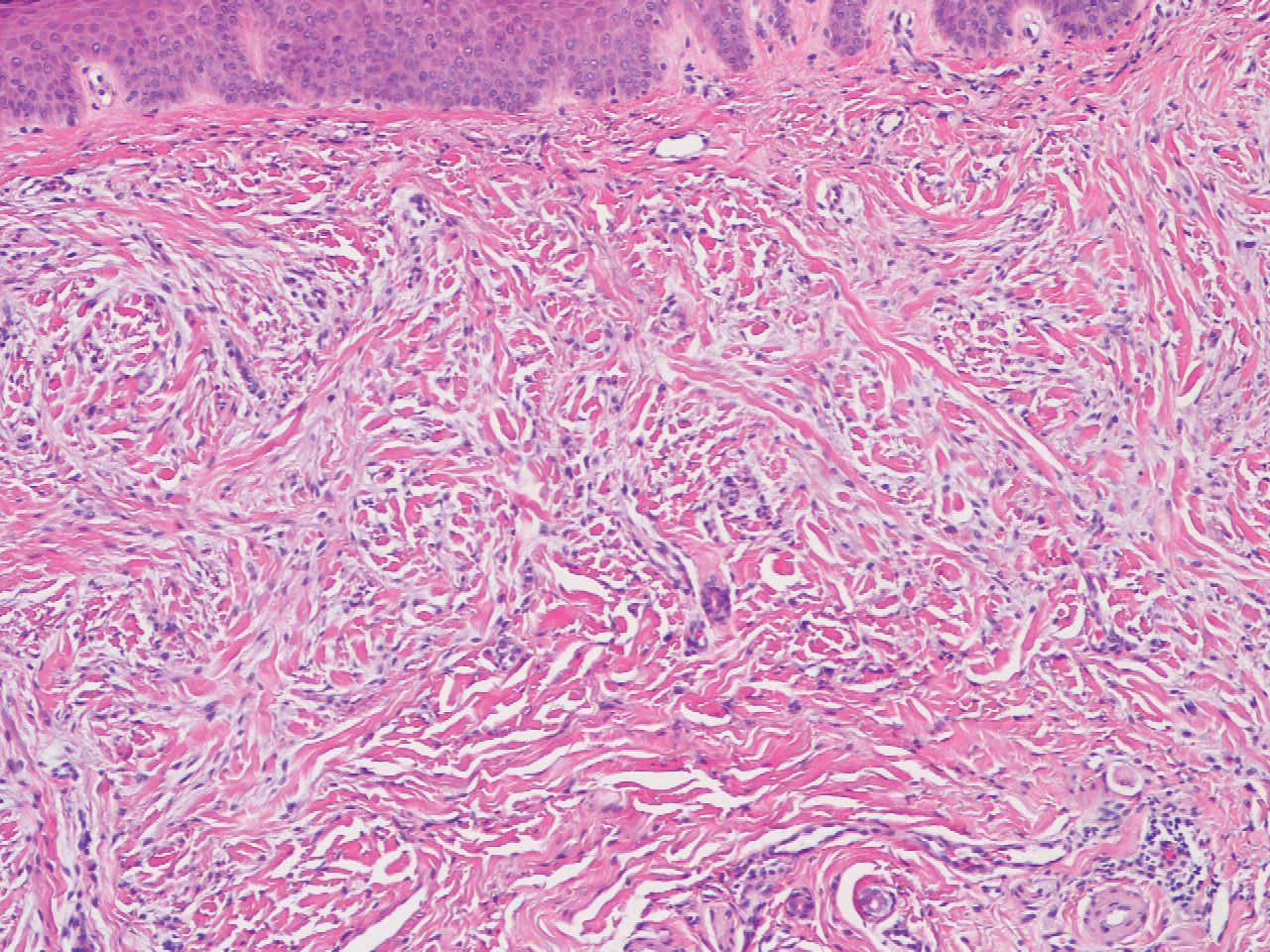

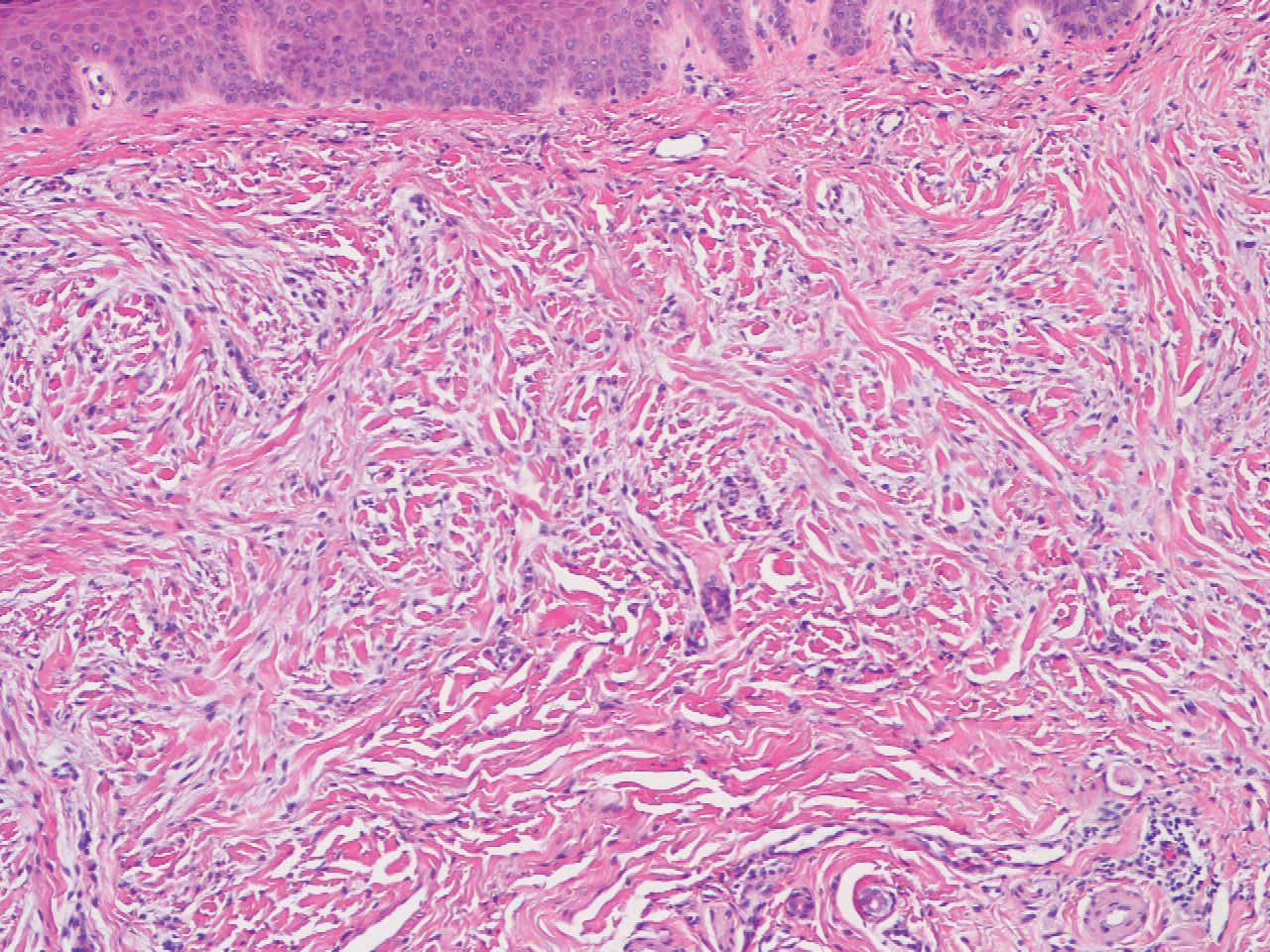

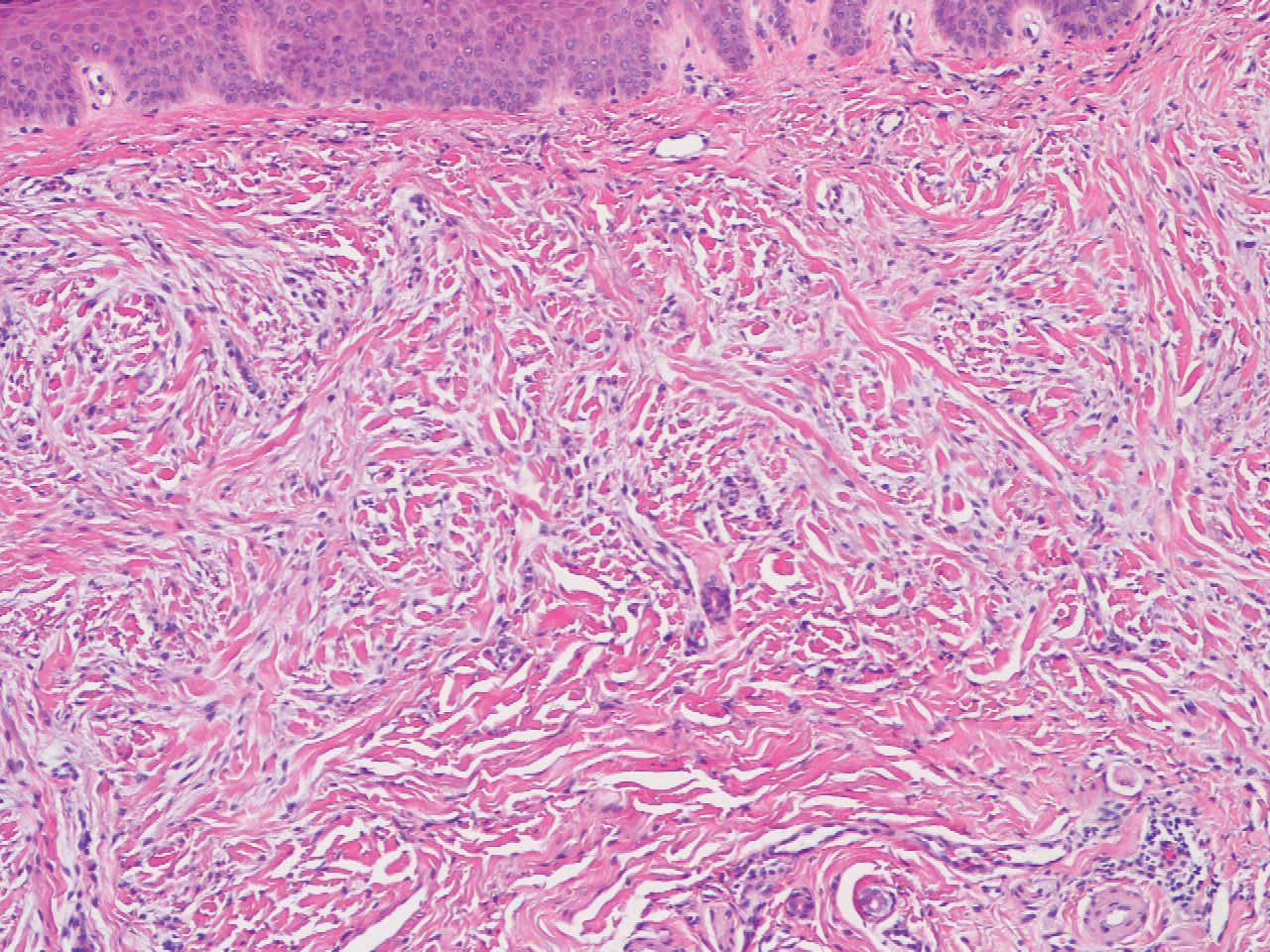

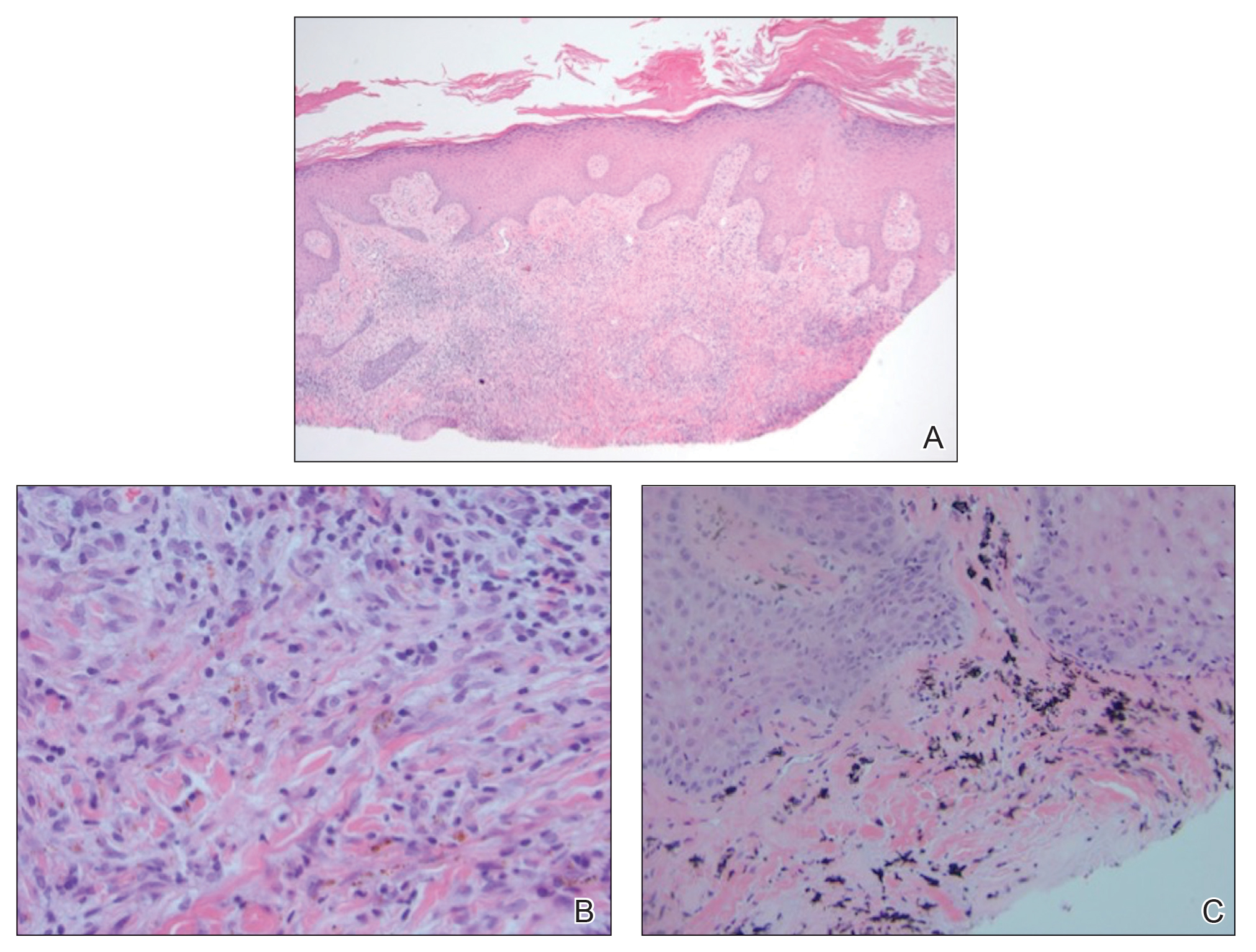

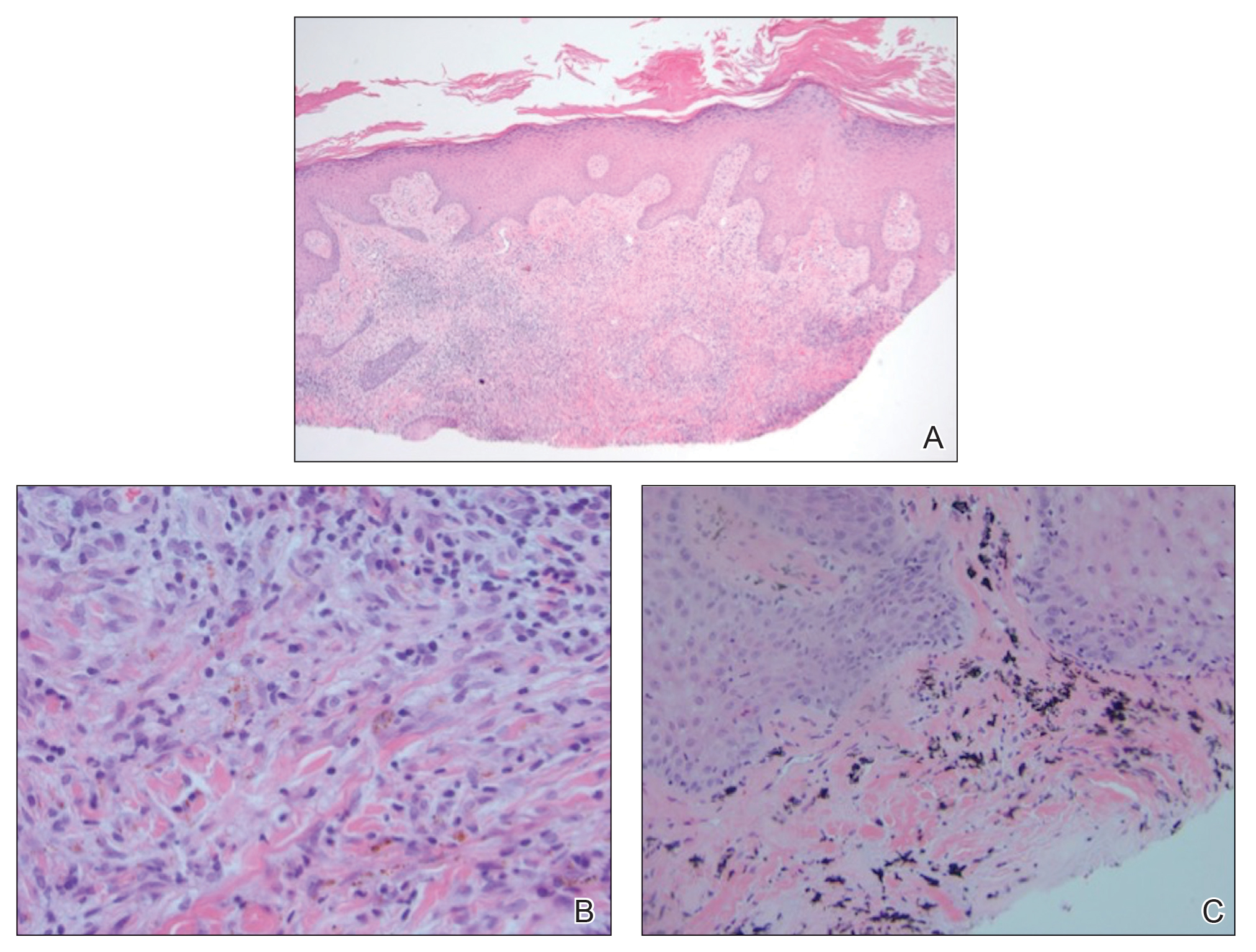

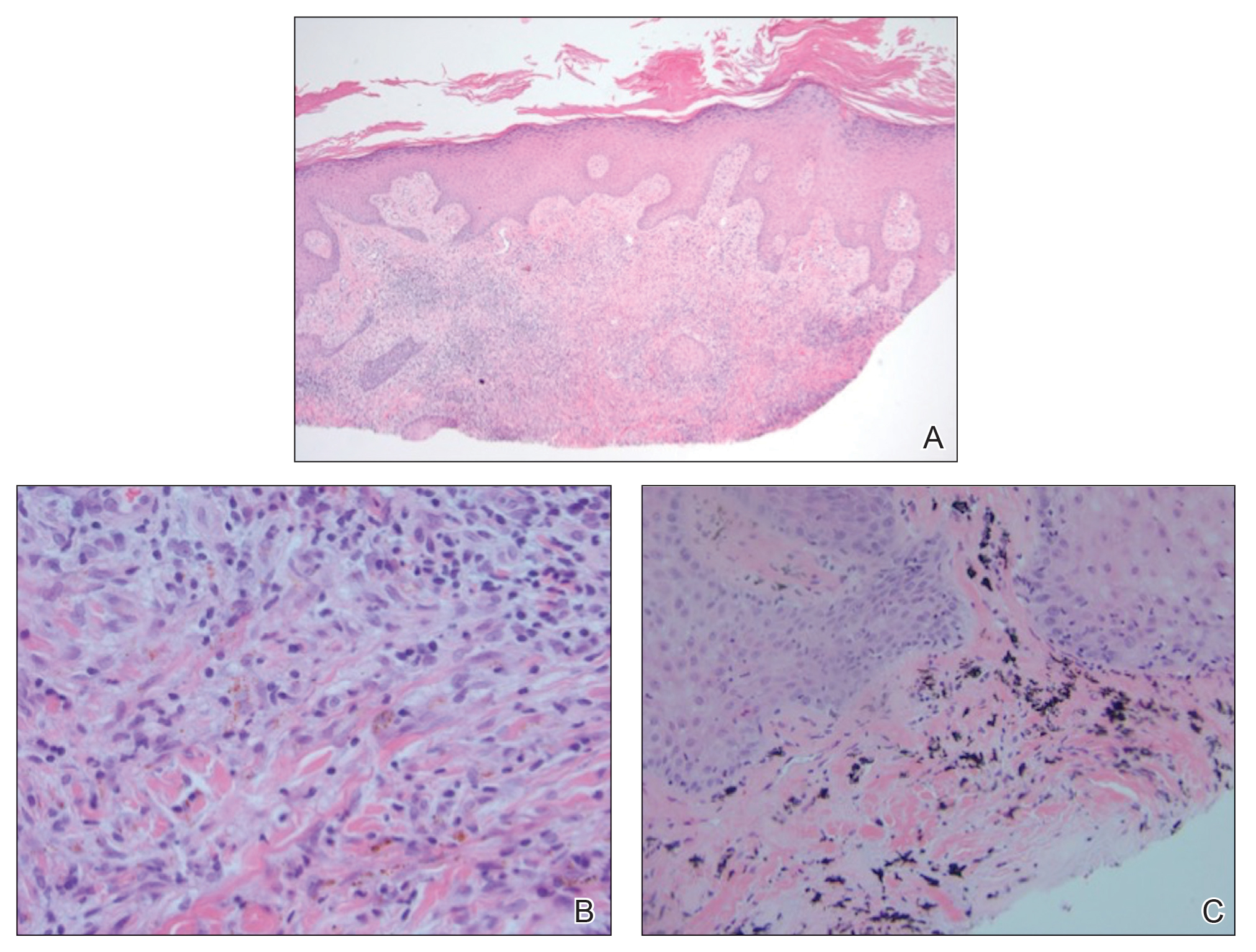

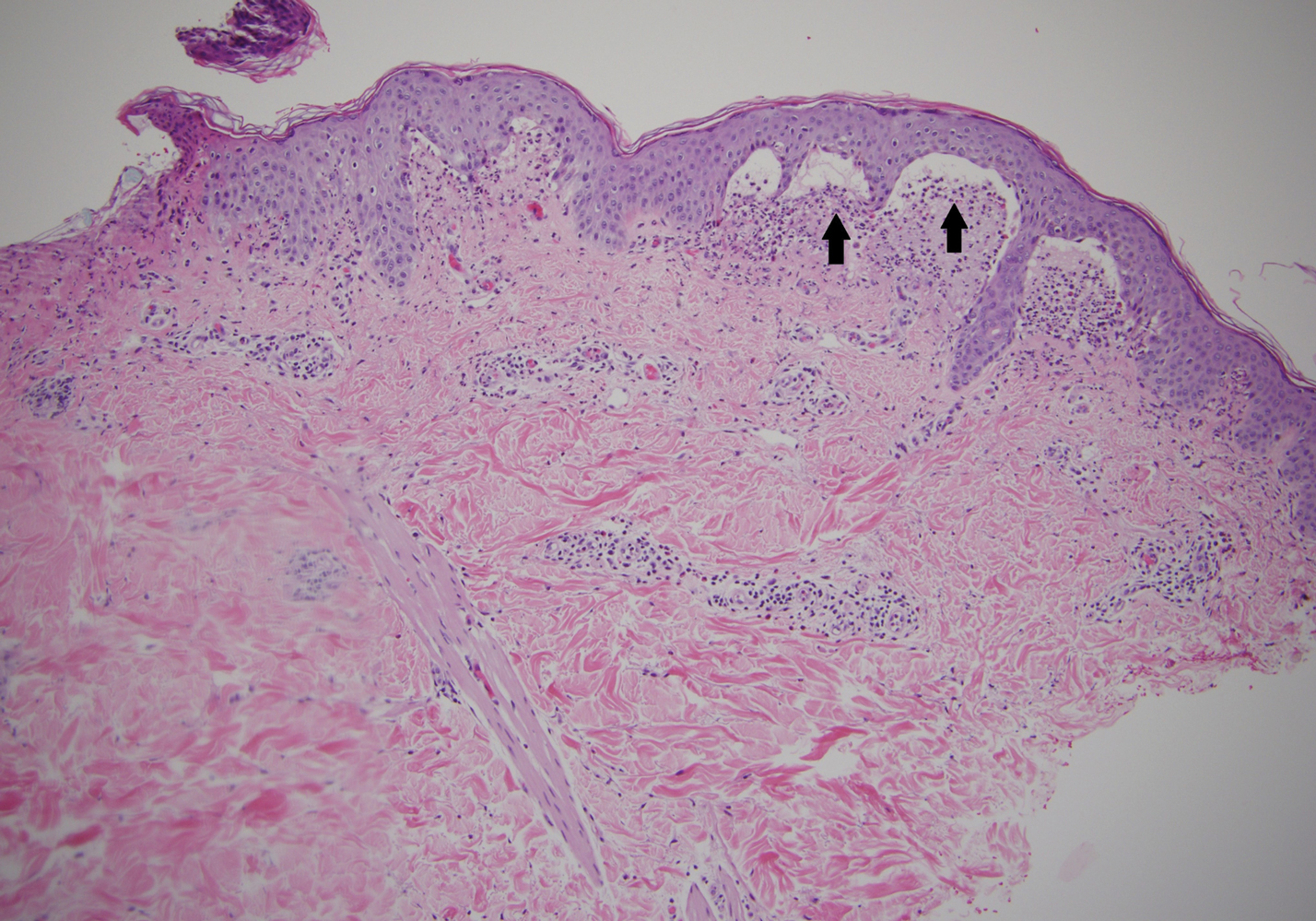

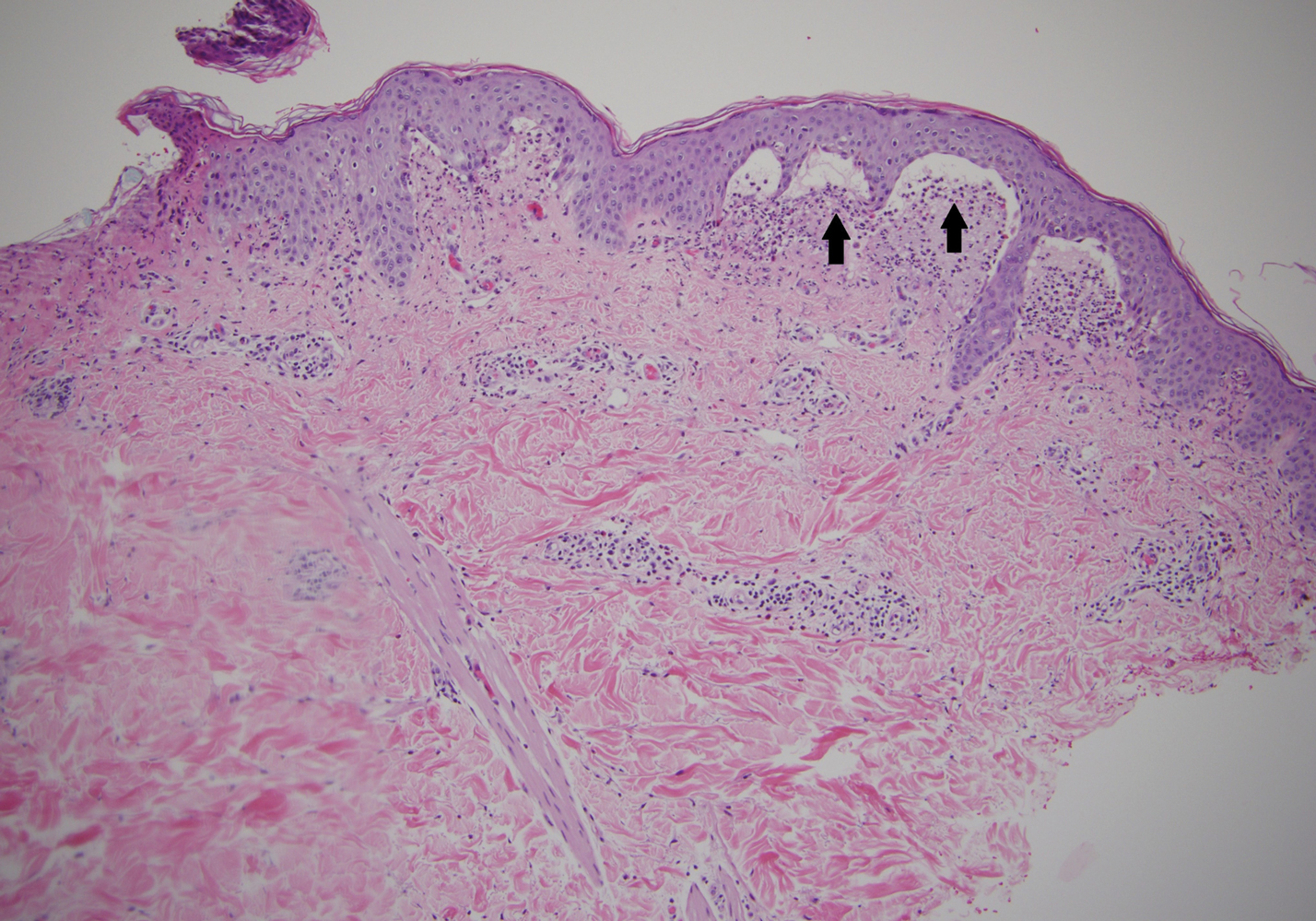

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

A 41-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic with multiple smooth papules on the left hand of 7 years' duration. The papules had been steadily increasing in number, and the patient reported that they were frequently symptomatic with a burning itching sensation. Physical examination revealed multiple 1- to 3-mm, dome-shaped, translucent to flesh-colored papules on the left hand with a few scattered bright red papules. No similar lesions were present on the right hand or elsewhere on the body. He had a history of hypertension but was otherwise healthy with no other chronic medical conditions.

Periorbital Swelling and Rash Following Trauma

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

Due to the potential concern of vision loss, the patient was directed to a local emergency department for immediate ophthalmologic evaluation. He was diagnosed with herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) and treated with oral acyclovir and prednisone. The rash and periorbital swelling resolved within 2 weeks of treatment, and he remained asymptomatic at follow-up 3 months later.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus presents with an erythematous and vesicular rash in the distribution of cranial nerve V1. The herpetiform grouping of lesions on the forehead is diagnostic of HZO. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection presents in 2 distinct forms. Primary infection (commonly known as chickenpox) presents clinically as a vesicular rash usually located on the face, arms, and trunk. Although the initial presentation usually occurs in childhood and is self-limited, the virus becomes latent in the dorsal root ganglia of sensory neurons. Varicella-zoster virus may become reactivated later in life and is termed herpes zoster (commonly known as shingles). It most often presents as a painful vesicular rash that may later form pustules.

Zoster outbreaks typically do not cross the midline but may in disseminated disease. Patients may experience a prodrome in the form of pain or less commonly pruritus or paresthesia along the dermatome between 1 and 10 days before the rash appears. Triggers for herpes zoster include illness, medications, malnutrition, surgery, or the natural decline in immune function due to aging. Trauma is another important precipitating event for VZV reactivation; one case-control study showed that zoster patients were 3.4 times more likely than controls to have had trauma the week prior.1 Patients with cranial zoster are more than 25 times more likely to have experienced trauma in the preceding week. Local trauma may predispose these patients to VZV reactivation by stimulating local sensory nerves or by disrupting local cutaneous immunity.2

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs when zoster presents in the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve. It is a serious, vision-threatening condition with a presentation that can include conjunctivitis, scleritis, keratitis, optic neuritis, exophthalmos, lid retraction, ptosis, and extraocular muscle palsies. Treatment includes antiviral medication (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) and prompt ophthalmologic consultation due to potential vision-threatening complications, such as acute retinal necrosis. Acute pain control may be necessary with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, steroids, tricyclic antidepressants, or anticonvulsants.3 Wet-to-dry dressings with sterile saline or Burow solution and/or calamine lotion can provide symptomatic relief of itching.

Periorbital and preseptal cellulitis typically present with more erythema of the skin surrounding the eye and without the accompanying rash. Periorbital cellulitis is the more serious infection and may be clinically distinguished by the presence of pain with extraocular muscle movement. Contact dermatitis and pemphigus vulgaris are possibilities, but both were less likely than HZO in this case presentation given the distribution of the rash and the patient history. Contact dermatitis typically presents with no prodrome with a main concern of pruritus. Pemphigus vulgaris nearly always includes involvement of the oral mucous membranes.

- Goh CL, Khoo L. A retrospective study of the clinical presentation and outcome of herpes zoster in a tertiary dermatology outpatient referral clinic. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:667-672.

- Zhang JX, Joesoef RM, Bialek S, et al. Association of physical trauma with risk of herpes zoster among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1007-1011.

- Rousseau A, Bourcier T, Colin J, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus--diagnosis and management. US Ophthalm Rev. 2013;6:119-124.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

Due to the potential concern of vision loss, the patient was directed to a local emergency department for immediate ophthalmologic evaluation. He was diagnosed with herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) and treated with oral acyclovir and prednisone. The rash and periorbital swelling resolved within 2 weeks of treatment, and he remained asymptomatic at follow-up 3 months later.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus presents with an erythematous and vesicular rash in the distribution of cranial nerve V1. The herpetiform grouping of lesions on the forehead is diagnostic of HZO. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection presents in 2 distinct forms. Primary infection (commonly known as chickenpox) presents clinically as a vesicular rash usually located on the face, arms, and trunk. Although the initial presentation usually occurs in childhood and is self-limited, the virus becomes latent in the dorsal root ganglia of sensory neurons. Varicella-zoster virus may become reactivated later in life and is termed herpes zoster (commonly known as shingles). It most often presents as a painful vesicular rash that may later form pustules.

Zoster outbreaks typically do not cross the midline but may in disseminated disease. Patients may experience a prodrome in the form of pain or less commonly pruritus or paresthesia along the dermatome between 1 and 10 days before the rash appears. Triggers for herpes zoster include illness, medications, malnutrition, surgery, or the natural decline in immune function due to aging. Trauma is another important precipitating event for VZV reactivation; one case-control study showed that zoster patients were 3.4 times more likely than controls to have had trauma the week prior.1 Patients with cranial zoster are more than 25 times more likely to have experienced trauma in the preceding week. Local trauma may predispose these patients to VZV reactivation by stimulating local sensory nerves or by disrupting local cutaneous immunity.2

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs when zoster presents in the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve. It is a serious, vision-threatening condition with a presentation that can include conjunctivitis, scleritis, keratitis, optic neuritis, exophthalmos, lid retraction, ptosis, and extraocular muscle palsies. Treatment includes antiviral medication (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) and prompt ophthalmologic consultation due to potential vision-threatening complications, such as acute retinal necrosis. Acute pain control may be necessary with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, steroids, tricyclic antidepressants, or anticonvulsants.3 Wet-to-dry dressings with sterile saline or Burow solution and/or calamine lotion can provide symptomatic relief of itching.

Periorbital and preseptal cellulitis typically present with more erythema of the skin surrounding the eye and without the accompanying rash. Periorbital cellulitis is the more serious infection and may be clinically distinguished by the presence of pain with extraocular muscle movement. Contact dermatitis and pemphigus vulgaris are possibilities, but both were less likely than HZO in this case presentation given the distribution of the rash and the patient history. Contact dermatitis typically presents with no prodrome with a main concern of pruritus. Pemphigus vulgaris nearly always includes involvement of the oral mucous membranes.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

Due to the potential concern of vision loss, the patient was directed to a local emergency department for immediate ophthalmologic evaluation. He was diagnosed with herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) and treated with oral acyclovir and prednisone. The rash and periorbital swelling resolved within 2 weeks of treatment, and he remained asymptomatic at follow-up 3 months later.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus presents with an erythematous and vesicular rash in the distribution of cranial nerve V1. The herpetiform grouping of lesions on the forehead is diagnostic of HZO. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection presents in 2 distinct forms. Primary infection (commonly known as chickenpox) presents clinically as a vesicular rash usually located on the face, arms, and trunk. Although the initial presentation usually occurs in childhood and is self-limited, the virus becomes latent in the dorsal root ganglia of sensory neurons. Varicella-zoster virus may become reactivated later in life and is termed herpes zoster (commonly known as shingles). It most often presents as a painful vesicular rash that may later form pustules.

Zoster outbreaks typically do not cross the midline but may in disseminated disease. Patients may experience a prodrome in the form of pain or less commonly pruritus or paresthesia along the dermatome between 1 and 10 days before the rash appears. Triggers for herpes zoster include illness, medications, malnutrition, surgery, or the natural decline in immune function due to aging. Trauma is another important precipitating event for VZV reactivation; one case-control study showed that zoster patients were 3.4 times more likely than controls to have had trauma the week prior.1 Patients with cranial zoster are more than 25 times more likely to have experienced trauma in the preceding week. Local trauma may predispose these patients to VZV reactivation by stimulating local sensory nerves or by disrupting local cutaneous immunity.2

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs when zoster presents in the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve. It is a serious, vision-threatening condition with a presentation that can include conjunctivitis, scleritis, keratitis, optic neuritis, exophthalmos, lid retraction, ptosis, and extraocular muscle palsies. Treatment includes antiviral medication (eg, acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) and prompt ophthalmologic consultation due to potential vision-threatening complications, such as acute retinal necrosis. Acute pain control may be necessary with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, steroids, tricyclic antidepressants, or anticonvulsants.3 Wet-to-dry dressings with sterile saline or Burow solution and/or calamine lotion can provide symptomatic relief of itching.

Periorbital and preseptal cellulitis typically present with more erythema of the skin surrounding the eye and without the accompanying rash. Periorbital cellulitis is the more serious infection and may be clinically distinguished by the presence of pain with extraocular muscle movement. Contact dermatitis and pemphigus vulgaris are possibilities, but both were less likely than HZO in this case presentation given the distribution of the rash and the patient history. Contact dermatitis typically presents with no prodrome with a main concern of pruritus. Pemphigus vulgaris nearly always includes involvement of the oral mucous membranes.

- Goh CL, Khoo L. A retrospective study of the clinical presentation and outcome of herpes zoster in a tertiary dermatology outpatient referral clinic. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:667-672.

- Zhang JX, Joesoef RM, Bialek S, et al. Association of physical trauma with risk of herpes zoster among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1007-1011.

- Rousseau A, Bourcier T, Colin J, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus--diagnosis and management. US Ophthalm Rev. 2013;6:119-124.

- Goh CL, Khoo L. A retrospective study of the clinical presentation and outcome of herpes zoster in a tertiary dermatology outpatient referral clinic. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:667-672.

- Zhang JX, Joesoef RM, Bialek S, et al. Association of physical trauma with risk of herpes zoster among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1007-1011.

- Rousseau A, Bourcier T, Colin J, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus--diagnosis and management. US Ophthalm Rev. 2013;6:119-124.

A 56-year-old man presented to an urgent care clinic with right periorbital swelling. He reported hitting his head on the door to a storage unit 2 days prior but did not lose consciousness. The swelling presented 2 days later. He reported mild headache and swelling around the right eye that coincided with an uncomfortable rash on the face and scalp. He also reported visual disruption due to the swelling but denied any eye pain, discharge from the eye, or painful eye movements. He had no lesions on the lips or inside the mouth. He denied any history of skin conditions. He further denied fever, joint pain, or any other systemic symptoms. His chronic medical conditions included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia that were stable on metformin, carvedilol, amlodipine, enalapril, and simvastatin, which he had taken for several years. He had not started any new medications, and there were no recent changes in the dosing of his medications.

Friable Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

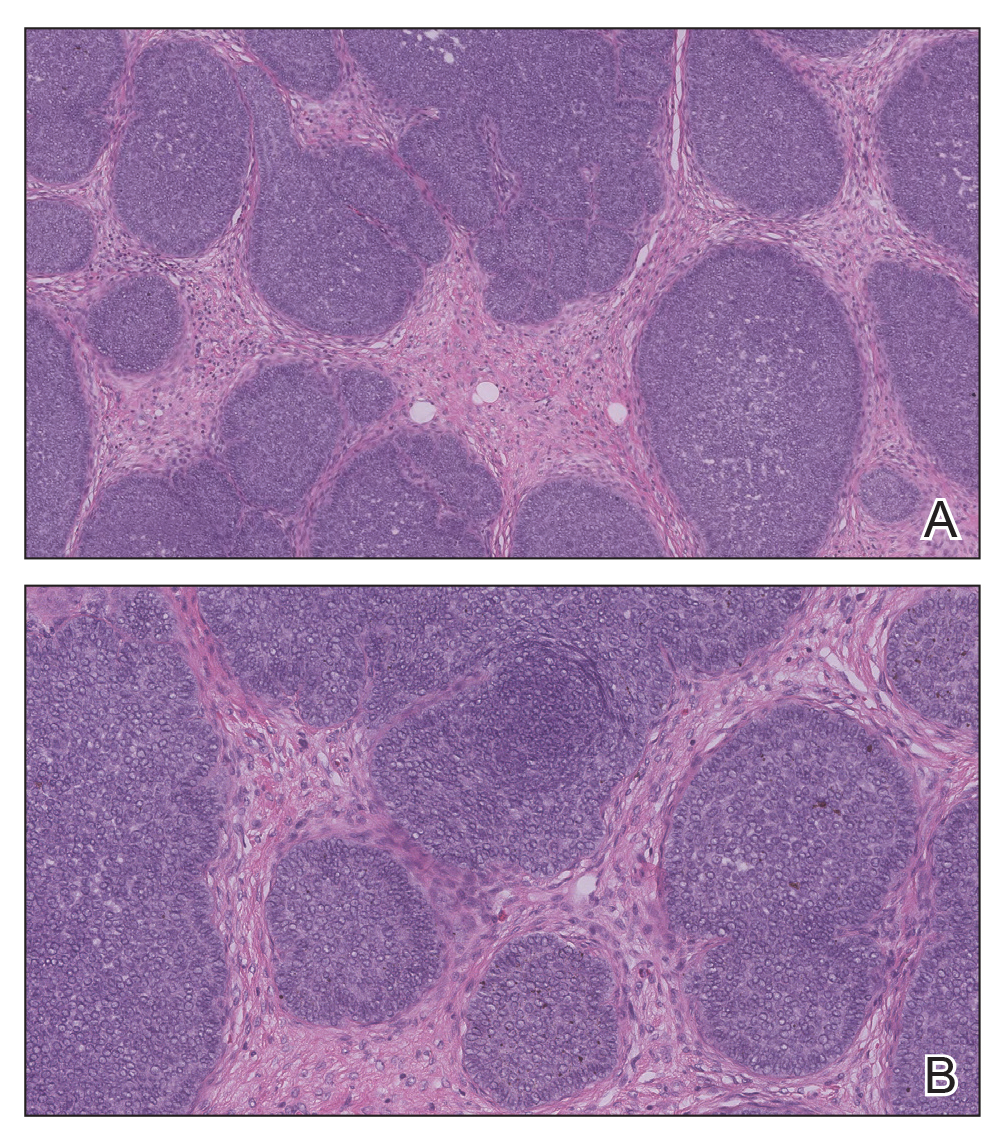

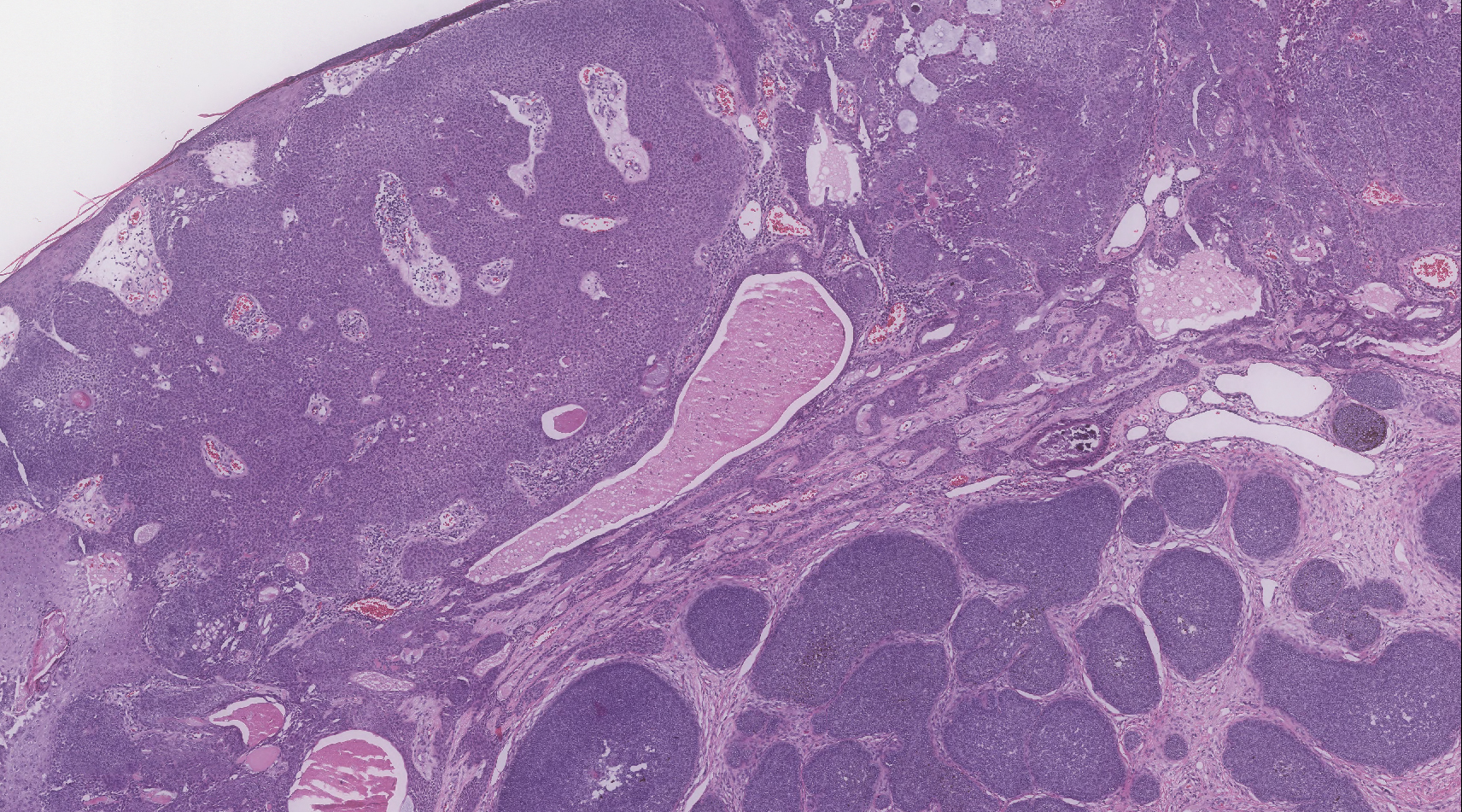

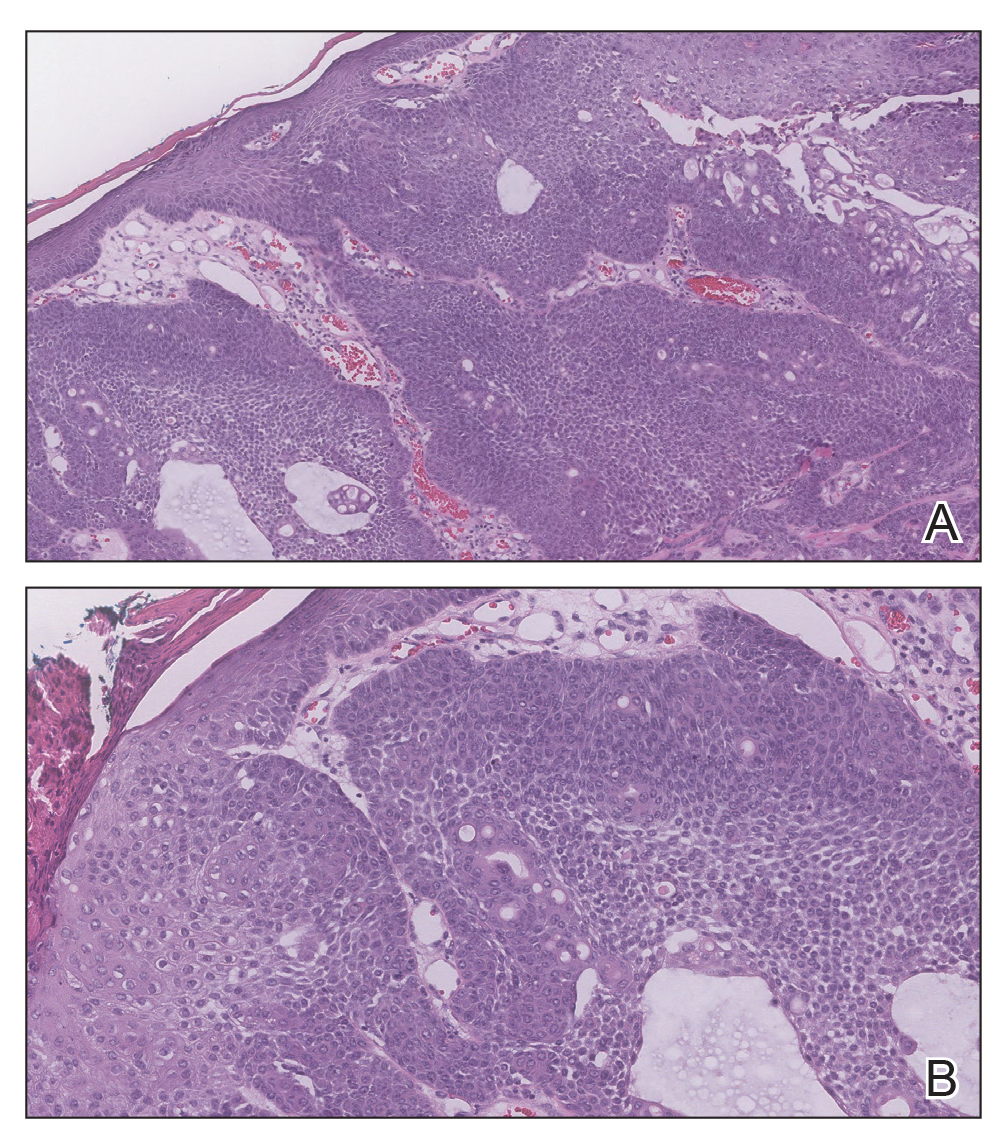

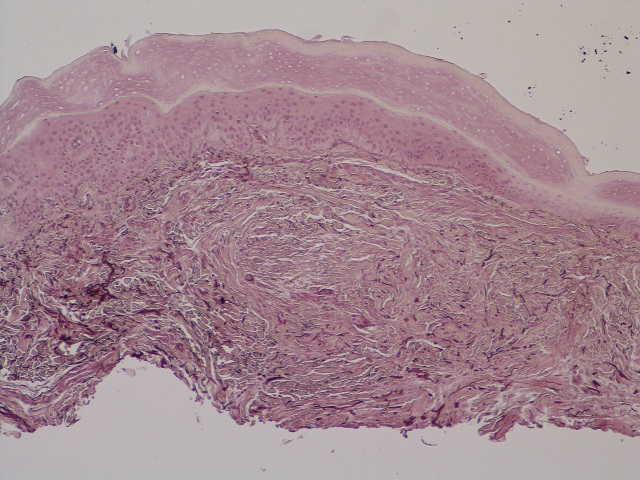

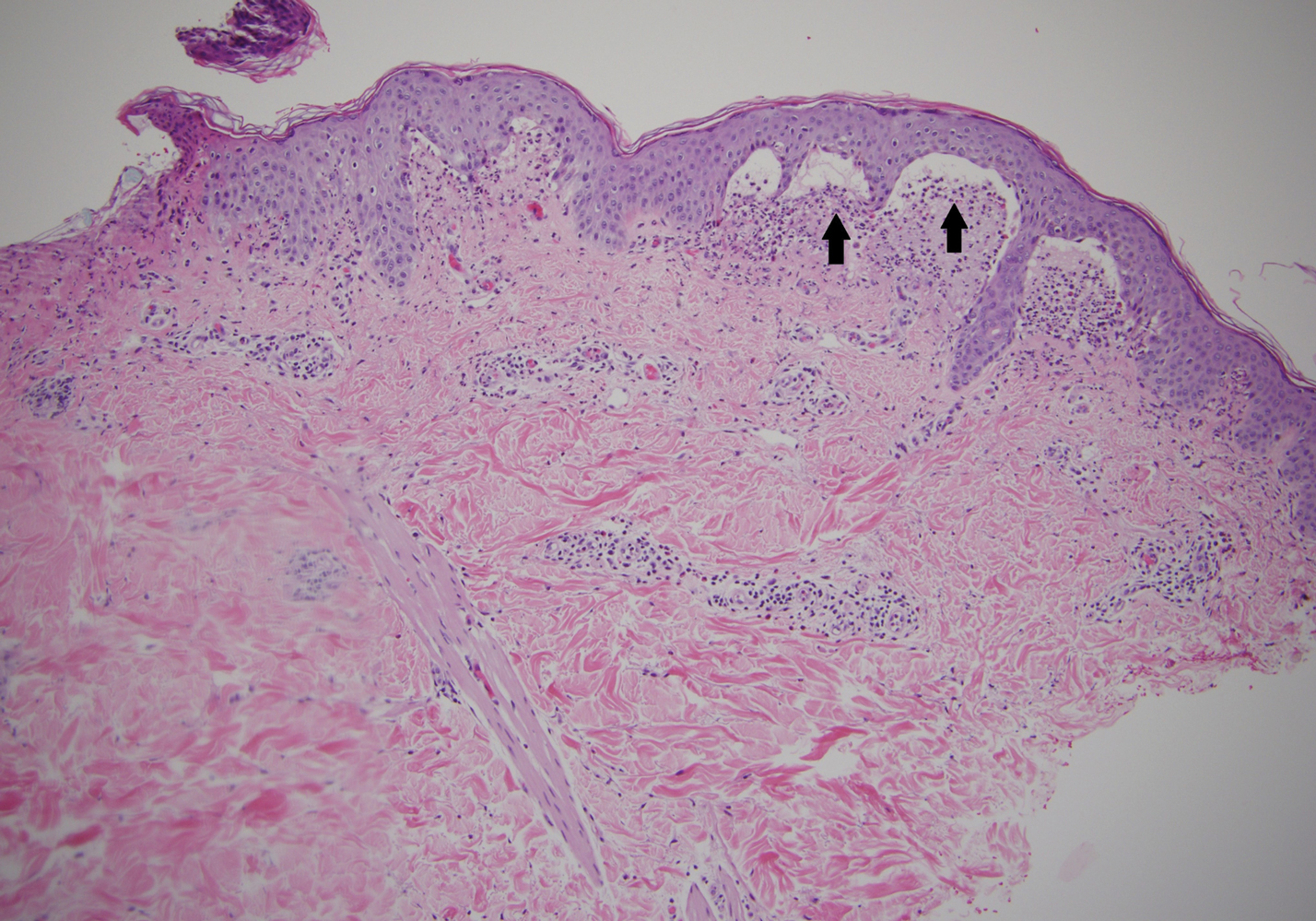

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

A 75-year-old woman presented with an enlarging plaque on the scalp of 5 years' duration. Physical examination revealed a 5.6.2 ×2.9-cm, tan-colored, verrucous plaque with an overlying pink friable nodule on the left occipital scalp. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and the patient did not have any constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss. The patient denied prior tanning bed use and reported intermittent sun exposure over her lifetime. She denied any prior surgical intervention. There was no family history of similar lesions.

Brown-Black Punctate Macule on the Left Palm

The Diagnosis: Talon Noir

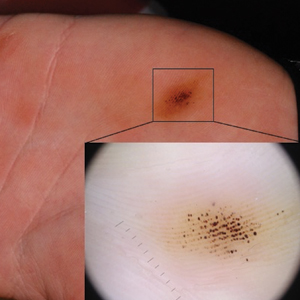

Paring of the stratum corneum overlying the lesion revealed coagulated blood, leading to a diagnosis of talon noir. Talon noir, also known as calcaneal petechiae, is a benign lesion that is typically found on the heel of the foot or palm of the hand.1 To the naked eye, talon noir appears as a brown-black asymmetric macule often with an overlying callus. Dermatoscopic visualization reveals grouped, reddish-colored globules composed of intracorneal hemorrhages, often in a linear pattern without any disruption of the normal skin surface architecture.1,2

Talon noir is the product of shear stress and often is seen in individuals who participate in sports such as baseball, hockey, soccer, and football.1,3 Lateral shearing forces cause tearing of blood vessels within the papillary dermis, which leads to punctate papillary dermal hemorrhages and extravasation of blood into the epidermis, resulting in intracorneal hemorrhage.1,4 Talon noir lesions are completely asymptomatic and typically resolve without intervention within 2 to 3 weeks of discontinuation of the precipitating sport or trauma.4

Recognizing talon noir is important, as it can occasionally be mistaken for acral lentiginous melanoma junctional nevus, tinea nigra, or verruca vulgaris. Paring of a lesion that is suspicious for talon noir is a simple and important step for ruling out a more ominous diagnosis (ie, acral lentiginous melanoma). If paring reveals coagulated blood, then junctional nevus, acral lentiginous melanoma, and tinea nigra can be excluded from the differential diagnosis. To rule out verruca vulgaris, one must prove that there is no disruption of the normal skin architecture, which can be confirmed with dermatoscopic visualization. Verrucae characteristically cause disruption of normal skin architecture, and junctional nevi would reveal a pigment pattern on dermatoscopy. This case illustrates how simple bedside procedures—dermoscopy and paring—can reassure patients and caregivers of the benign nature of talon noir.

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731.

2. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919.

3. Ayres S, Mihan R. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:262.

4. Bender TW. Cutaneous manifestations of disease in athletes. Skinmed. 2003;2:34-40

The Diagnosis: Talon Noir

Paring of the stratum corneum overlying the lesion revealed coagulated blood, leading to a diagnosis of talon noir. Talon noir, also known as calcaneal petechiae, is a benign lesion that is typically found on the heel of the foot or palm of the hand.1 To the naked eye, talon noir appears as a brown-black asymmetric macule often with an overlying callus. Dermatoscopic visualization reveals grouped, reddish-colored globules composed of intracorneal hemorrhages, often in a linear pattern without any disruption of the normal skin surface architecture.1,2

Talon noir is the product of shear stress and often is seen in individuals who participate in sports such as baseball, hockey, soccer, and football.1,3 Lateral shearing forces cause tearing of blood vessels within the papillary dermis, which leads to punctate papillary dermal hemorrhages and extravasation of blood into the epidermis, resulting in intracorneal hemorrhage.1,4 Talon noir lesions are completely asymptomatic and typically resolve without intervention within 2 to 3 weeks of discontinuation of the precipitating sport or trauma.4

Recognizing talon noir is important, as it can occasionally be mistaken for acral lentiginous melanoma junctional nevus, tinea nigra, or verruca vulgaris. Paring of a lesion that is suspicious for talon noir is a simple and important step for ruling out a more ominous diagnosis (ie, acral lentiginous melanoma). If paring reveals coagulated blood, then junctional nevus, acral lentiginous melanoma, and tinea nigra can be excluded from the differential diagnosis. To rule out verruca vulgaris, one must prove that there is no disruption of the normal skin architecture, which can be confirmed with dermatoscopic visualization. Verrucae characteristically cause disruption of normal skin architecture, and junctional nevi would reveal a pigment pattern on dermatoscopy. This case illustrates how simple bedside procedures—dermoscopy and paring—can reassure patients and caregivers of the benign nature of talon noir.

The Diagnosis: Talon Noir

Paring of the stratum corneum overlying the lesion revealed coagulated blood, leading to a diagnosis of talon noir. Talon noir, also known as calcaneal petechiae, is a benign lesion that is typically found on the heel of the foot or palm of the hand.1 To the naked eye, talon noir appears as a brown-black asymmetric macule often with an overlying callus. Dermatoscopic visualization reveals grouped, reddish-colored globules composed of intracorneal hemorrhages, often in a linear pattern without any disruption of the normal skin surface architecture.1,2

Talon noir is the product of shear stress and often is seen in individuals who participate in sports such as baseball, hockey, soccer, and football.1,3 Lateral shearing forces cause tearing of blood vessels within the papillary dermis, which leads to punctate papillary dermal hemorrhages and extravasation of blood into the epidermis, resulting in intracorneal hemorrhage.1,4 Talon noir lesions are completely asymptomatic and typically resolve without intervention within 2 to 3 weeks of discontinuation of the precipitating sport or trauma.4

Recognizing talon noir is important, as it can occasionally be mistaken for acral lentiginous melanoma junctional nevus, tinea nigra, or verruca vulgaris. Paring of a lesion that is suspicious for talon noir is a simple and important step for ruling out a more ominous diagnosis (ie, acral lentiginous melanoma). If paring reveals coagulated blood, then junctional nevus, acral lentiginous melanoma, and tinea nigra can be excluded from the differential diagnosis. To rule out verruca vulgaris, one must prove that there is no disruption of the normal skin architecture, which can be confirmed with dermatoscopic visualization. Verrucae characteristically cause disruption of normal skin architecture, and junctional nevi would reveal a pigment pattern on dermatoscopy. This case illustrates how simple bedside procedures—dermoscopy and paring—can reassure patients and caregivers of the benign nature of talon noir.

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731.

2. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919.

3. Ayres S, Mihan R. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:262.

4. Bender TW. Cutaneous manifestations of disease in athletes. Skinmed. 2003;2:34-40

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731.

2. Lao M, Weissler A, Siegfried E. Talon noir. J Pediatr. 2013;163:919.

3. Ayres S, Mihan R. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:262.

4. Bender TW. Cutaneous manifestations of disease in athletes. Skinmed. 2003;2:34-40

A 16-year-old adolescent boy presented to our clinic with a “new brown mole” on the left palm that had appeared within the last few months. The patient did not recall if it had changed in size, shape, or color, and there was no associated pain or itching. He denied any trauma to the hand, but he actively played both hockey and baseball. Physical examination revealed calloused palms bilaterally. One of the calluses was present over the hypothenar eminence, and centrally there were grouped brown-black punctate macules, some that coalesced into larger macules. Dermatoscopic examination (inset) revealed punctate rustcolored macules in a parallel ridge pattern. There was no disruption of the normal skin architecture.

Firm Tumor Encasing the Left Second Toe of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

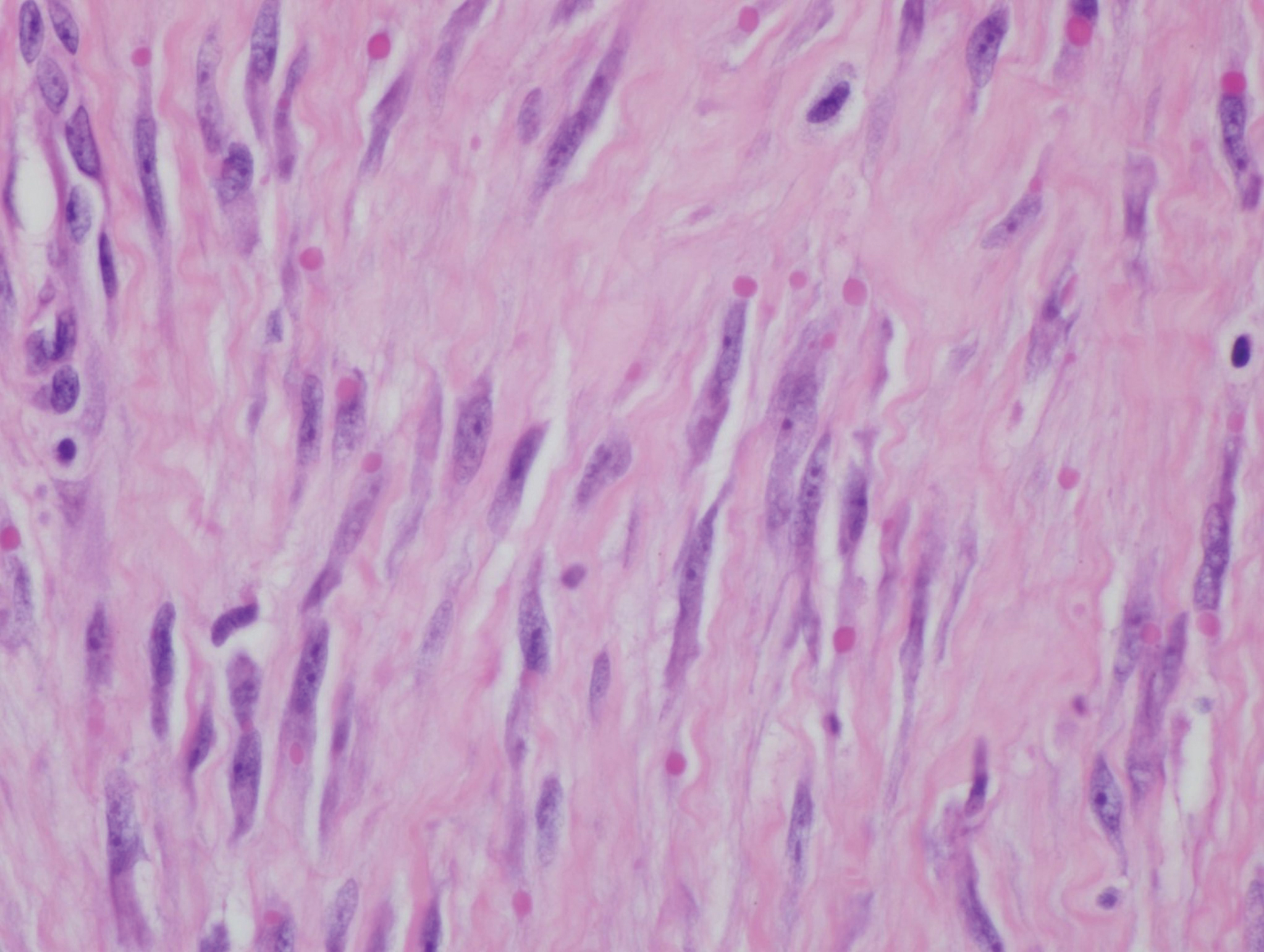

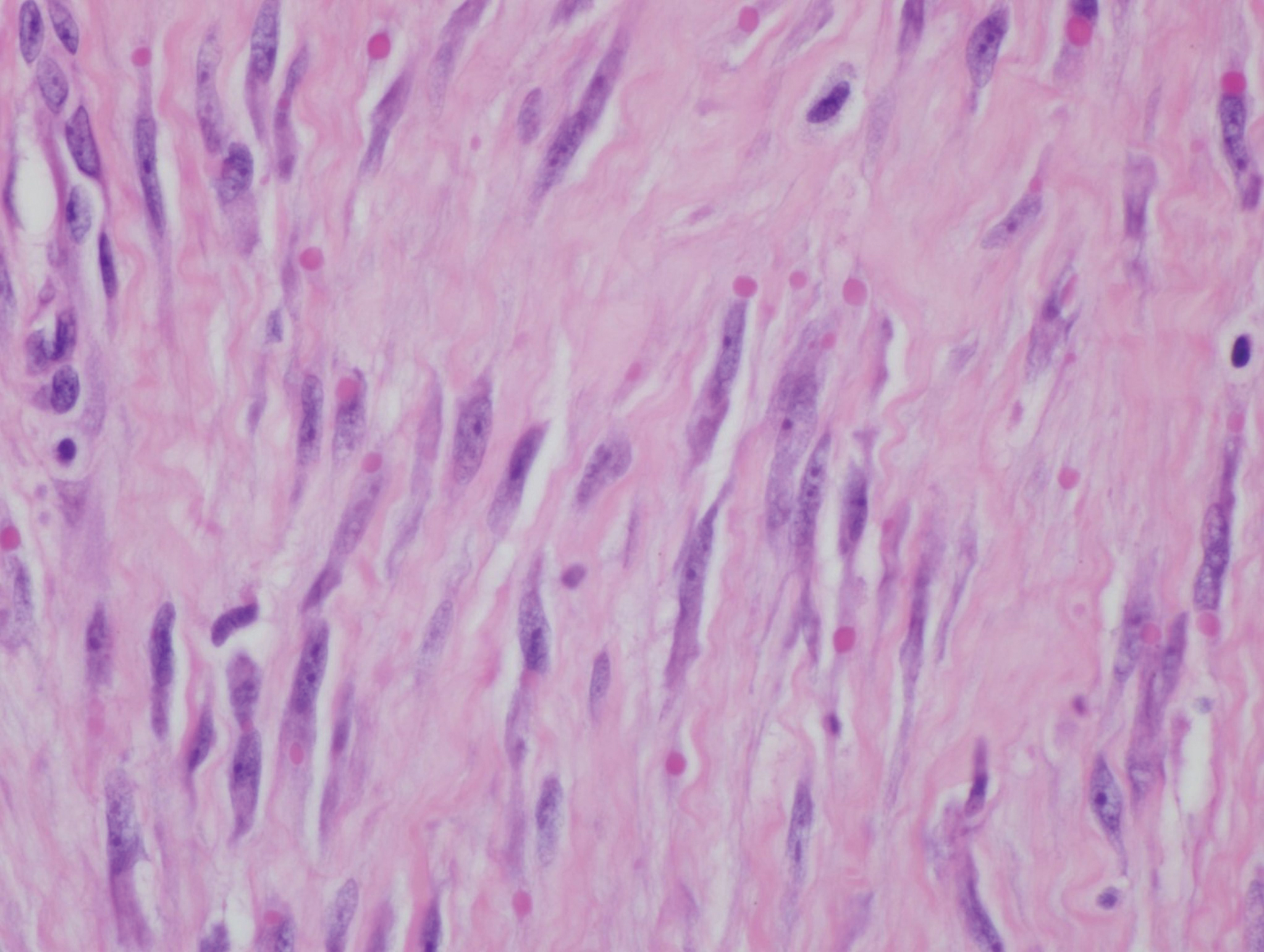

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

A 10-month-old infant boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a firm, nonpainful, 5.5.×5.6-cm tumor encasing the left second toe, with associated skin breakdown, gait impairment, and lateral displacement of the third toe. The lesion began as a small bump under the toenail at 2 months of age; it then grew rapidly without bleeding or ulceration. It was diagnosed as a hemangioma at 4 months of age, and oral propranolol was initiated for 3 months, without suppression of tumor growth. The patient was referred to the pediatric dermatology department where a clinical diagnosis was made, and the patient was subsequently referred to plastic surgery for excision.

Numerous Flesh-Colored Nodules on the Trunk

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

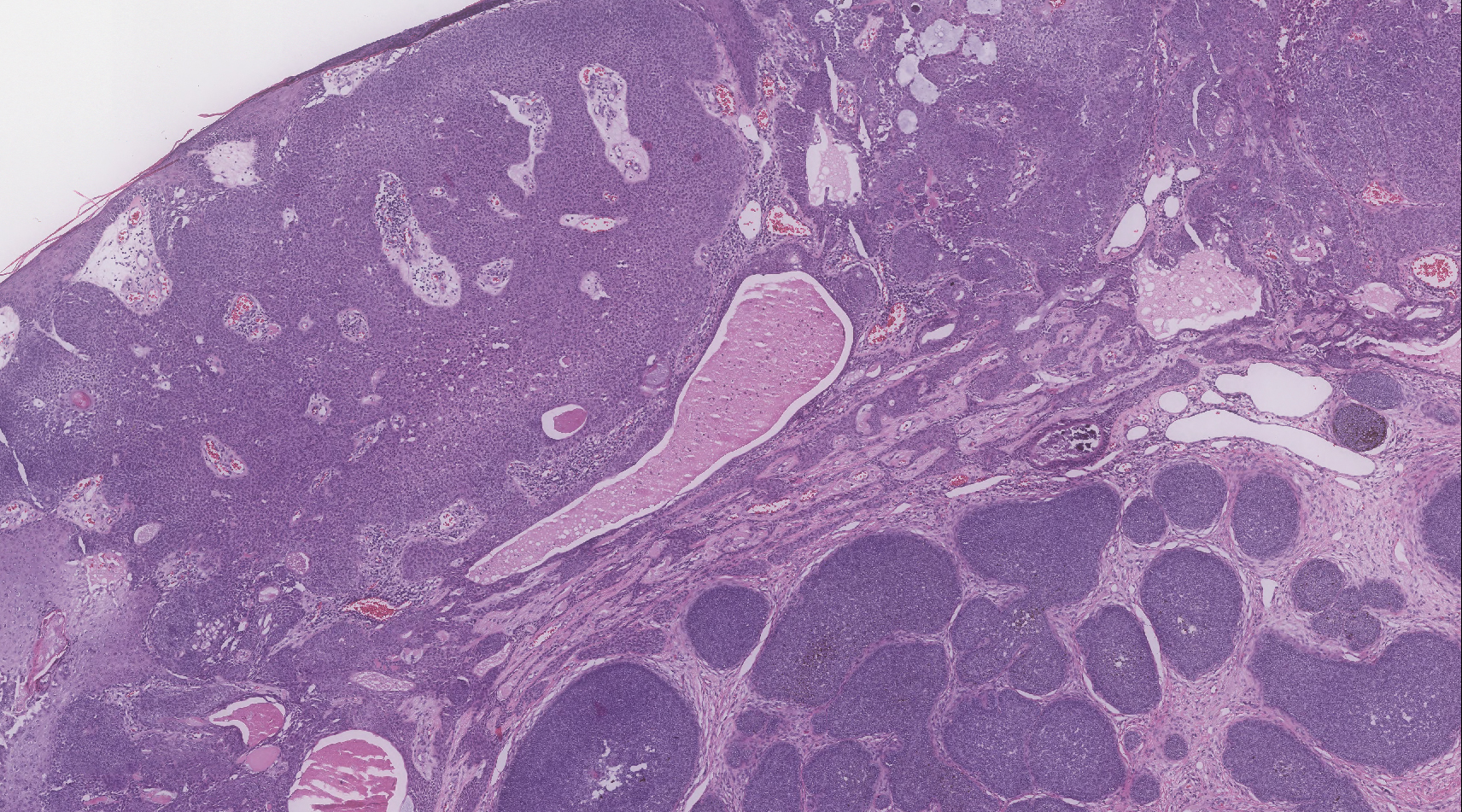

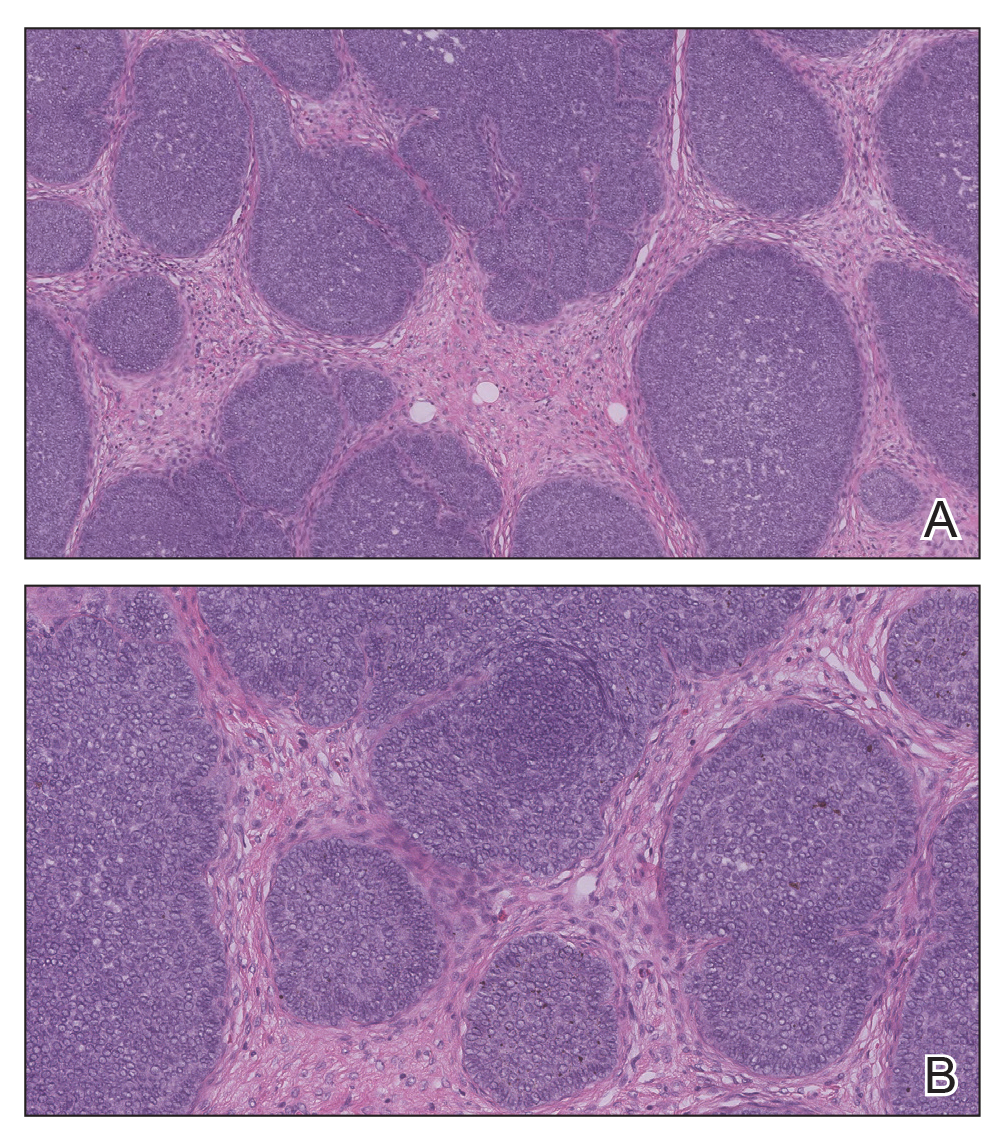

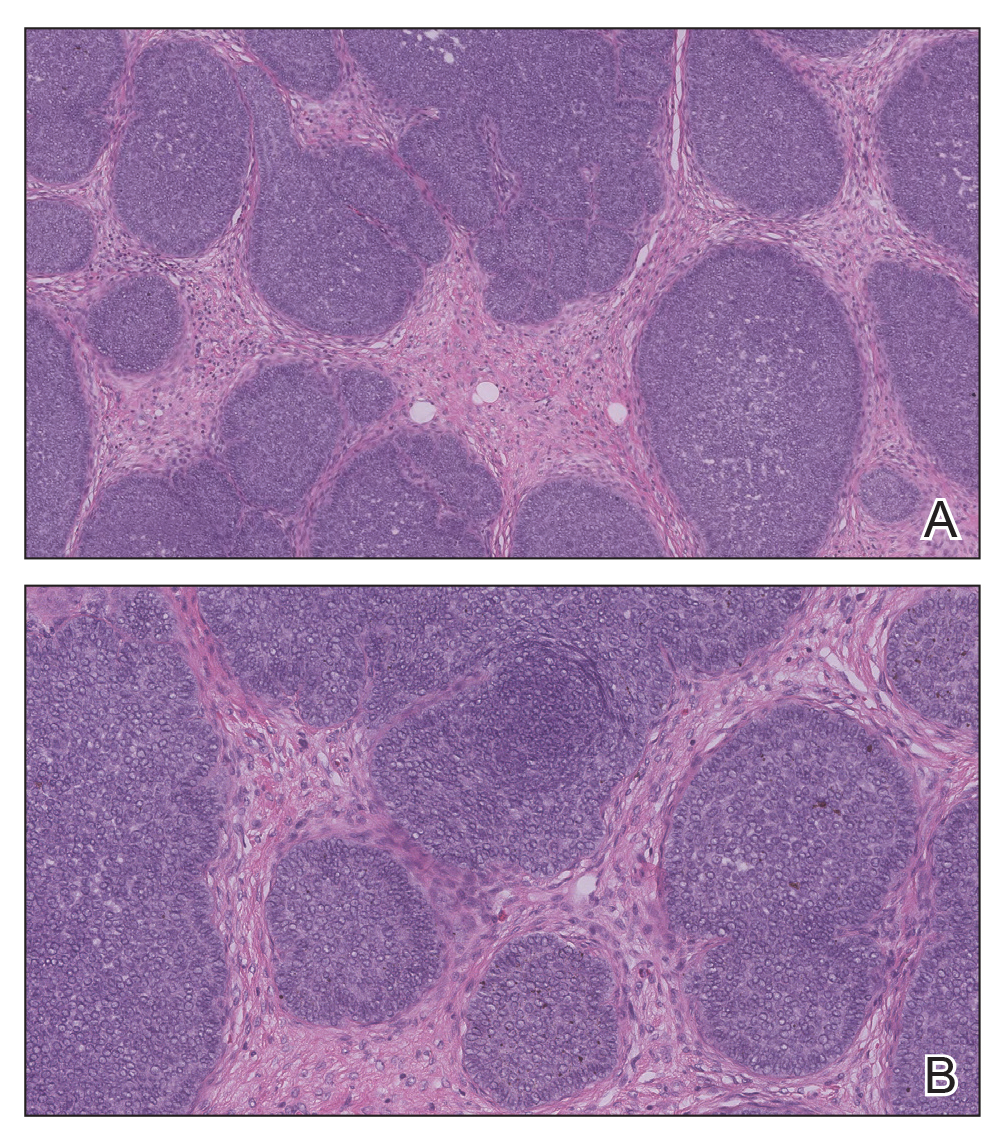

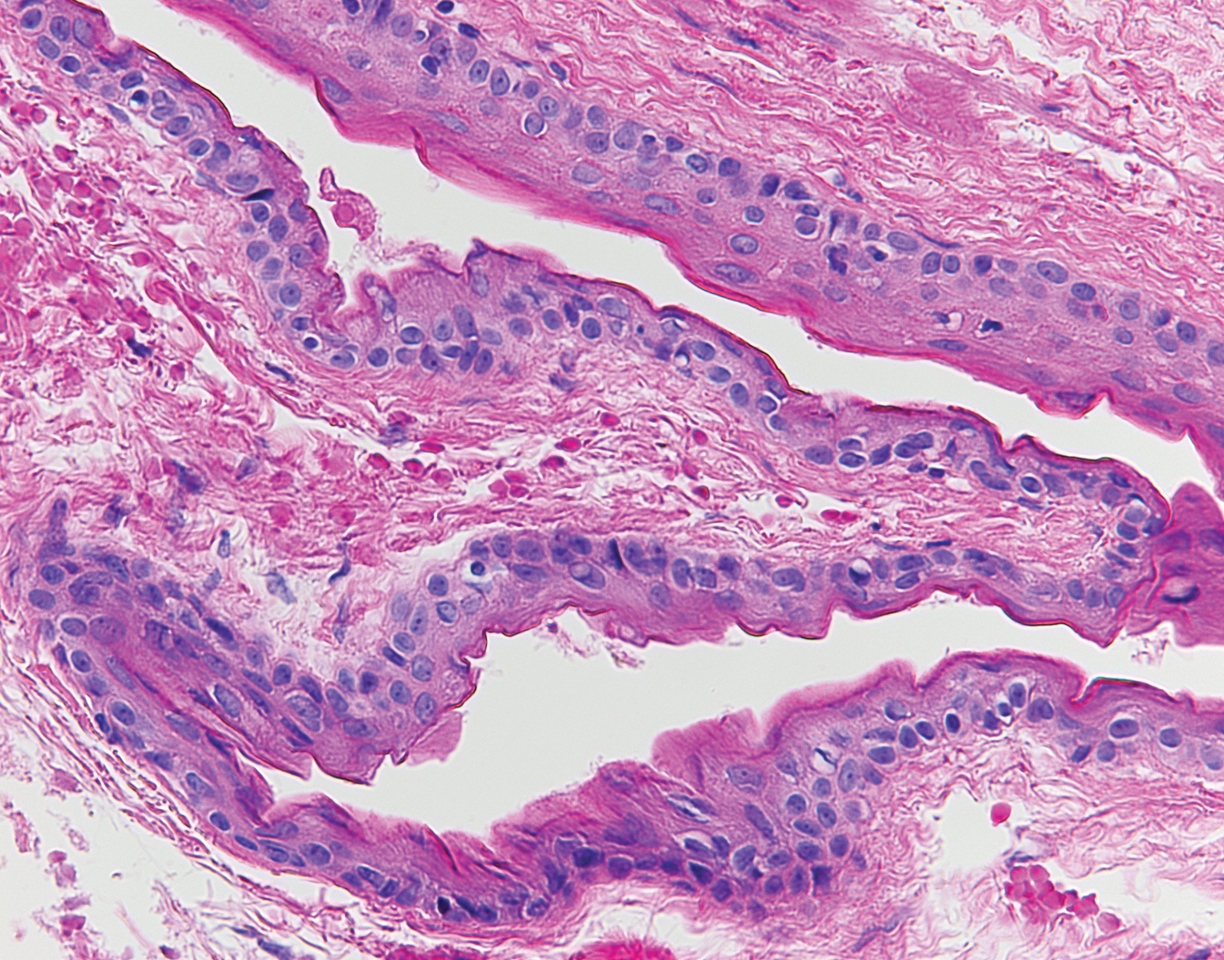

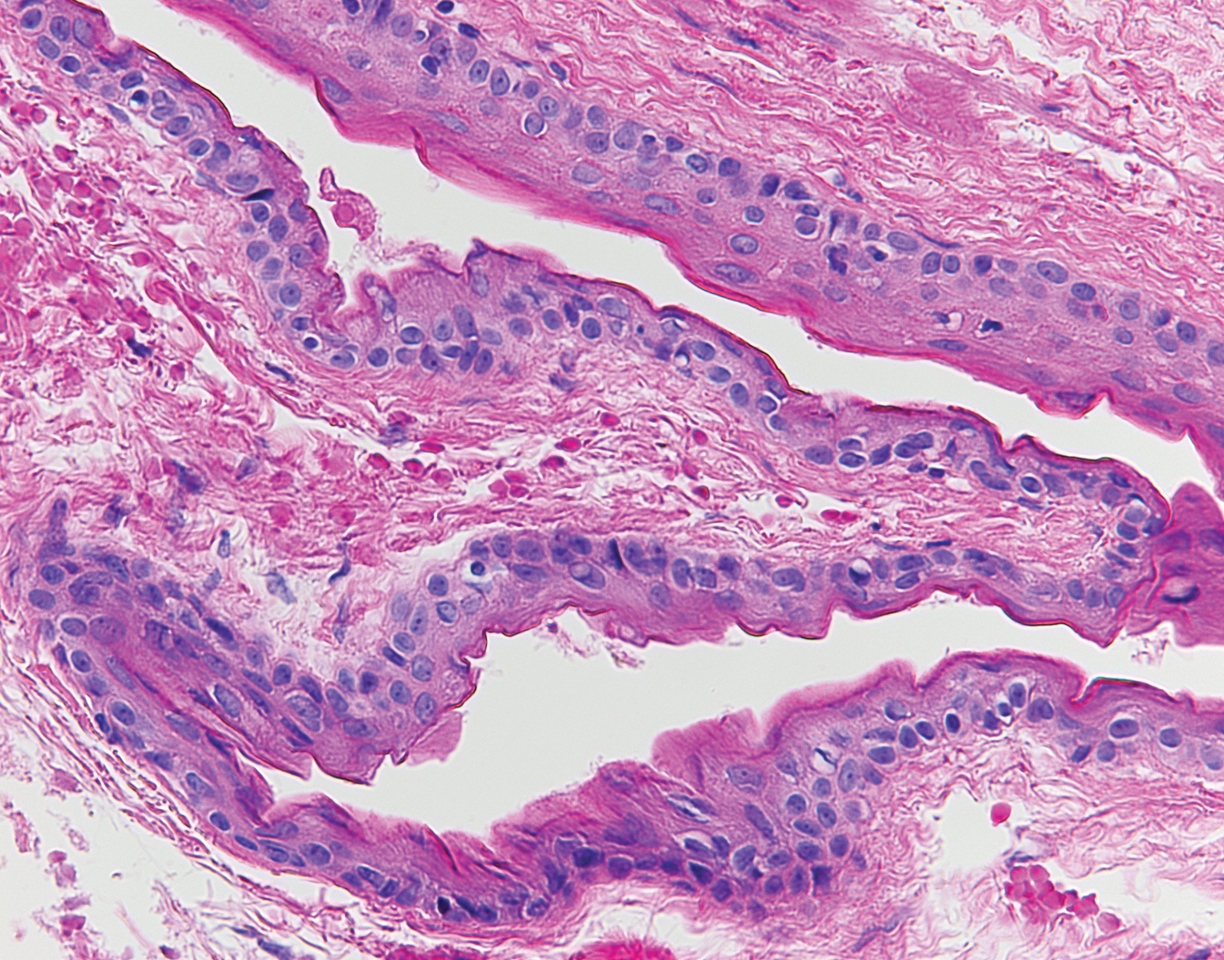

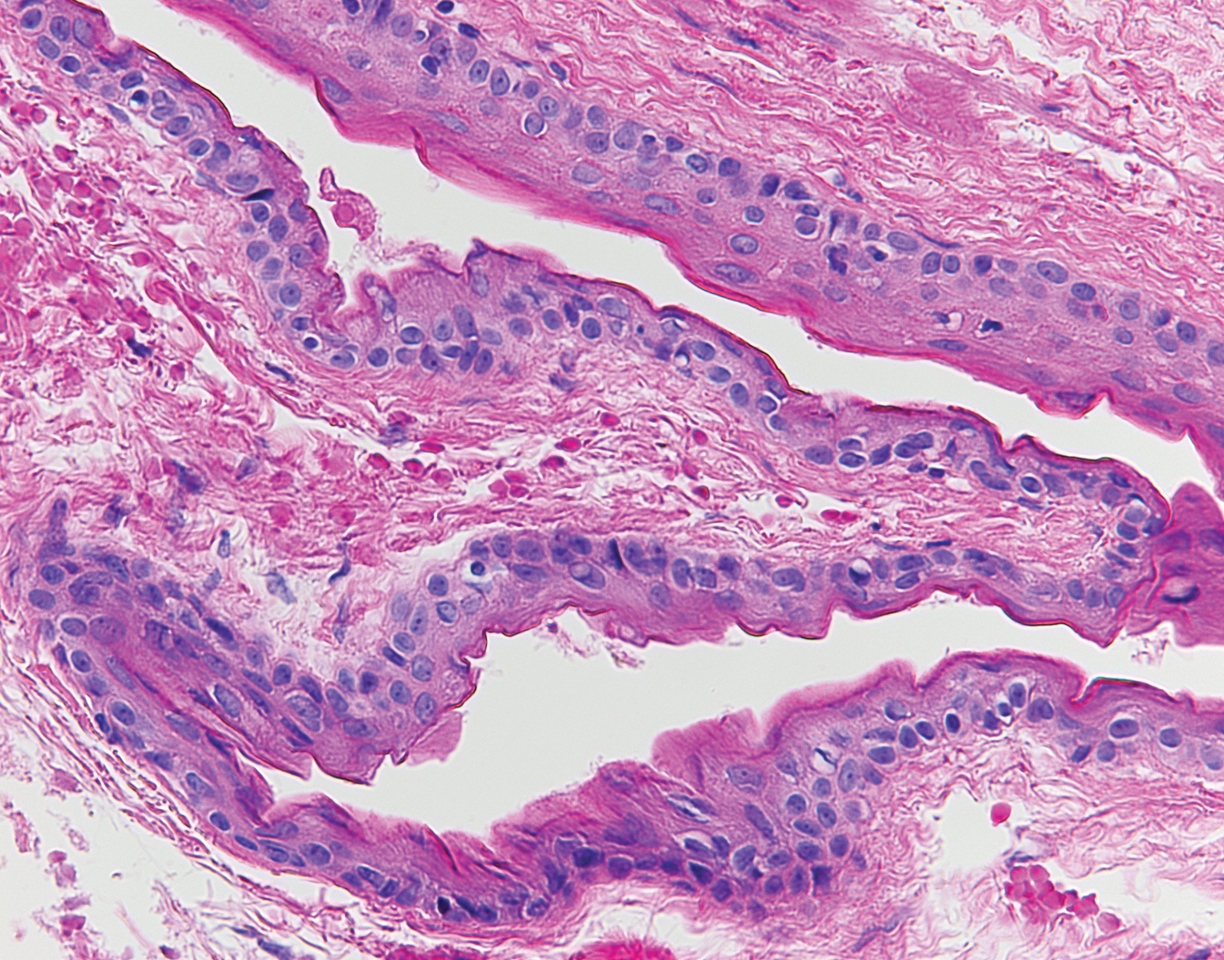

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

The Diagnosis: Steatocystoma Multiplex

The punch biopsy of an abdominal lesion demonstrated a folded cyst wall with a wavy eosinophilic cuticle (Figure), characteristics consistent with steatocystoma multiplex (SM).

Also known as eruptive steatocystoma, SM consists of numerous flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules and nodules that most commonly arise during adolescence, with a median age of onset of 26 years.1 These hamartomatous nevoid malformations arise in areas with well-developed pilosebaceous units, such as the upper extremities, neck, axillae, and trunk.1,2 They occur less commonly on the scalp, face, and acral surfaces.2-5 The lesions range in size from 2 to 30 mm6 and usually are asymptomatic.1 Occasionally, steatocystomas become tender or can rupture.7

Steatocystoma multiplex may arise sporadically or may be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Mutations in exon 1 of the keratin 17 gene, KRT17, have been identified in autosomal-dominant SM.6,8 KRT17 mutations also are responsible for pachyonychia congenita type 2, which is associated with SM.9 Some patients with pachyonychia congenita type 2 who have prominent SM and mild nail findings may be misdiagnosed as having pure SM.2

The histopathologic features of SM were described in a study by Cho and colleagues1 of 64 patients. Steatocystomas have cyst walls that may be either intricately folded or round/oval, comprised of an average of 4.9 epithelial cell layers. In most cases, the cyst wall contains sebaceous lobules. In all cases, an acellular eosinophilic cuticle was present, and no granular layer was seen. Few vellus hairs may be observed in the cystic cavity.1

The differential diagnosis of SM includes eruptive vellus hair cysts, lipomas, Muir-Torre syndrome, and Gardner syndrome. Some have suggested that eruptive vellus hair cysts and SM exist on a disease spectrum because of their similar clinical presentation.10 In contrast to SM, however, eruptive vellus hair cysts originate in the infundibulum of the hair shaft rather than the sebaceous duct, and more numerous vellus hair shafts are seen on histopathology.1

Various treatment modalities have been described, including isotretinoin for inflamed lesions,11 cryotherapy for noninflamed lesions,11 aspiration of lesions smallerthan 1 cm,12 and electrocautery combined with topical retinoids.13 Laser treatment has been described, with a 1450-nm diode laser used to target the abnormal sebaceous glands and a 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser used to target the dermal cysts.14 Carbon dioxide lasers also may be used to open the cyst for drainage.15 Surgical excision or mini-incision also may be performed.16,17

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his assistance with interpretation of the dermatopathology in this case.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

- Cho S, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinical and histologic features of 64 cases of steatocystoma multiplex. J Dermatol. 2002;29:152-156.

- Rollins T, Levin RM, Heymann WR. Acral steatocystoma multiplex.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 2):396-399.

- Setoyama M, Mizoguchi S, Usuki K, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex: a case with unusual clinical and histological manifestation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:89-92.

- Cole LA. Steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1437-1439.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Balice Y, et al. Acral subcutaneous steatocystoma multiplex: a distinct subtype of the disease? Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:198-201.

- Liu Q, Wu W, Lu J, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex is associated with the R94C mutation in the KRTl7 gene. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5072-5076.

- Egbert BM, Price NM, Segal RJ. Steatocystoma multiplex. Report of a florid case and a review. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:334-335.

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475-480.

- McLean WH, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, et al. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273-278.

- Ohtake N, Kubota Y, Takayama O, et al. Relationship between steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5, pt 2):876-878.

- Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgurler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

- Sato K, Shibuya K, Taguchi H, et al. Aspiration therapy in steatocystoma multiplex. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:35-37.

- Papakonstantinou E, Franke I, Gollnick H. Facial steatocystoma multiplex combined with eruptive vellus hair cysts: a hybrid? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2051-2053.

- Moody MN, Landau JM, Goldberg LH, et al. 1,450-nm diode laser in combination with the 1550-nm fractionated erbium-doped fiber laser for the treatment of steatocystoma multiplex: a case report. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7, pt 1):1104-1106.

- Rossi R, Cappugi P, Battini M, et al. CO2 laser therapy in a case of steatocystoma multiplex with prominent nodules on the face and neck. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:302-304.

- Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

- Adams BB, Mutasim DF, Nordlund JJ. Steatocystoma multiplex: a quick removal technique. Cutis. 1999;64:127-130.

A 33-year-old woman presented with numerous firm, noncompressible, flesh-colored nodules that measured 3 to 4 mm and were distributed across the abdomen, chest, back, and neck. The lesions had been present for approximately 10 years. The patient denied any lesion-associated pain, itching, or bleeding, and there was no family history of similar lesions. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the central abdomen was obtained.

Widespread Skin Thickening

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

Scleromyxedema is a rare skin disorder characterized by a diffuse eruption of small waxy papules that are linearly arranged and closely spaced together. As the papular lesions coalesce, the skin thickens. Firm induration of the skin is widespread and--unlike the distribution in scleroderma and scleredema--amplified over the facial convexities, especially the glabella and ears. Histopathology reveals the classic triad of mucin accumulation, proliferation of fibroblasts, and collagen deposition with associated fibrotic changes.1

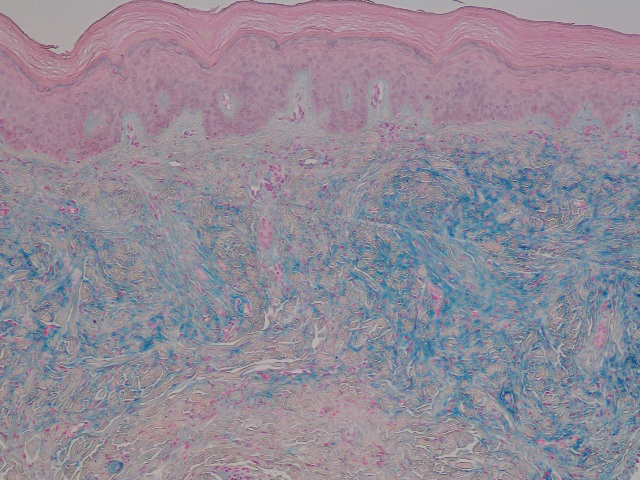

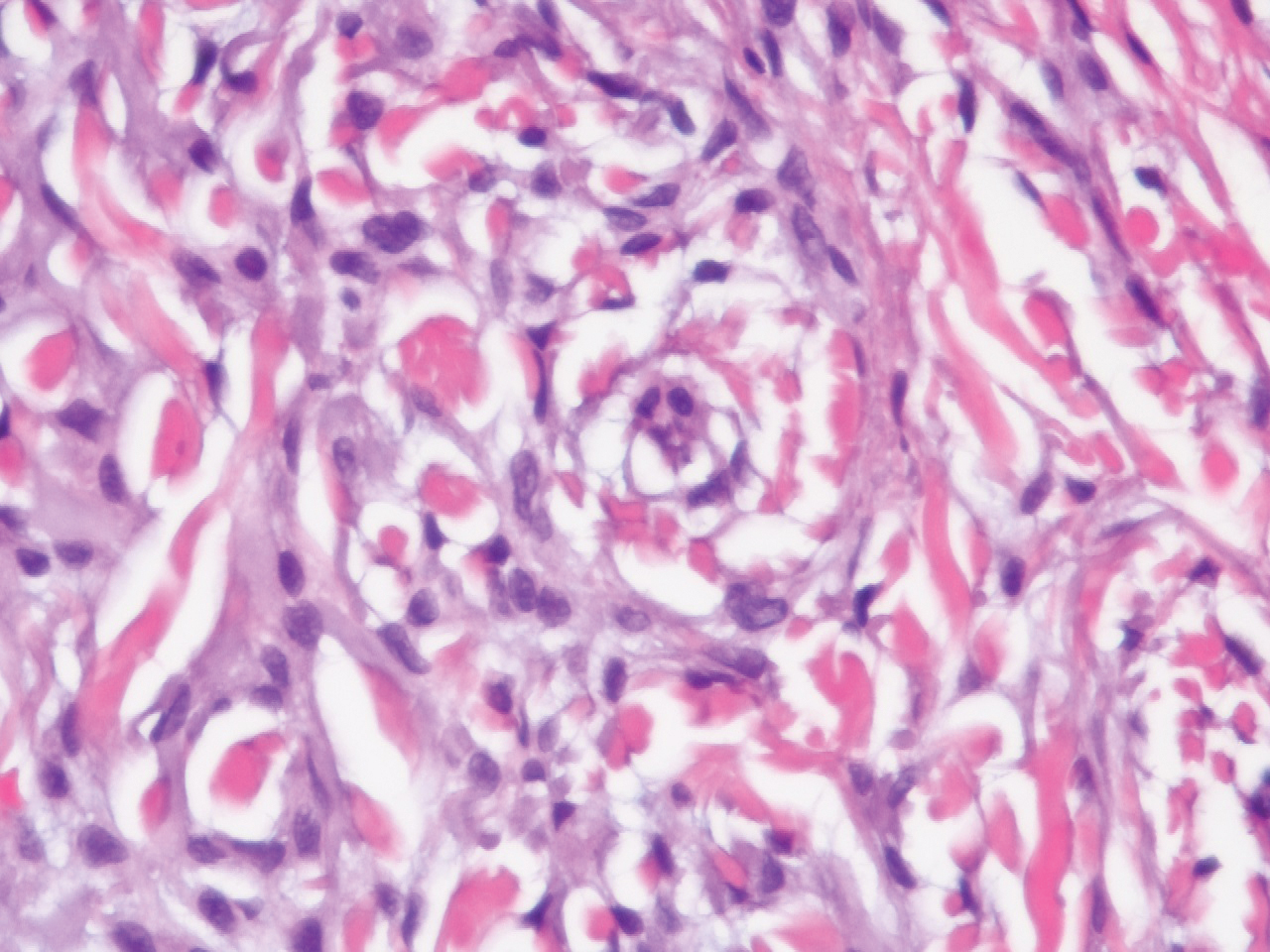

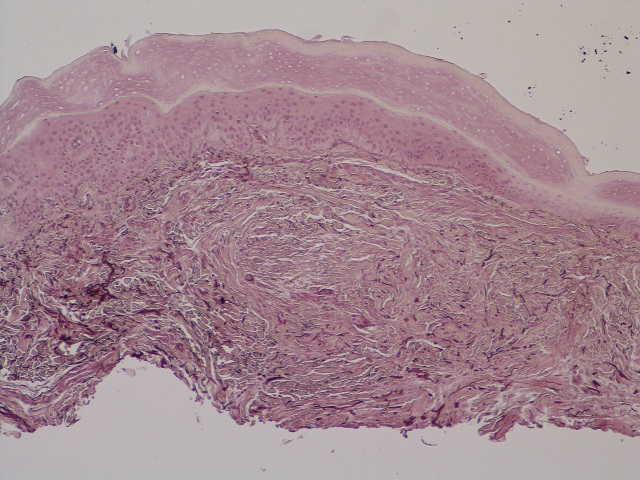

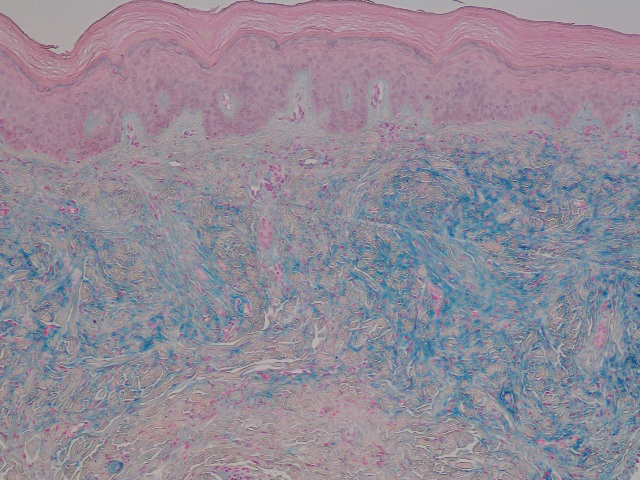

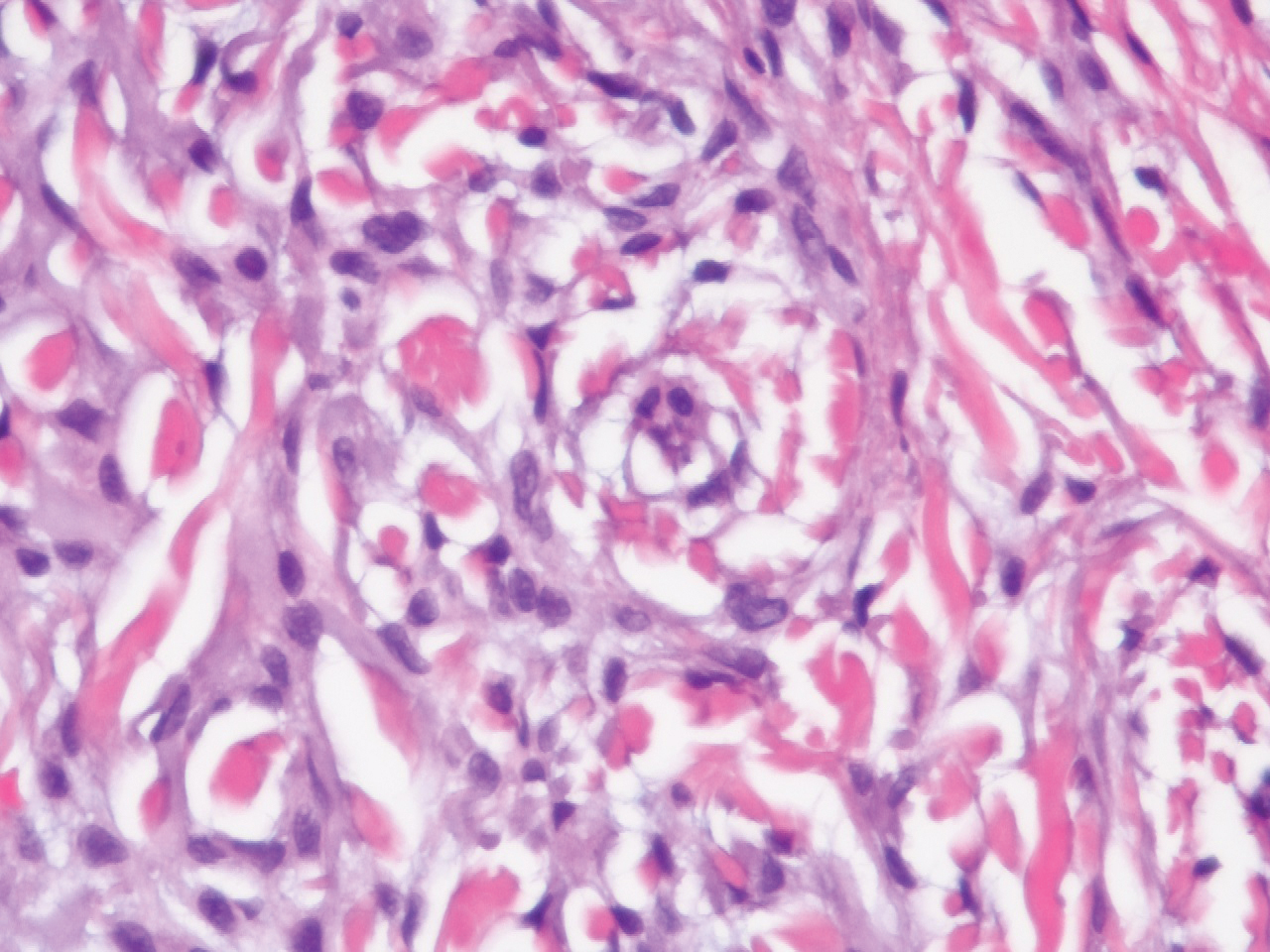

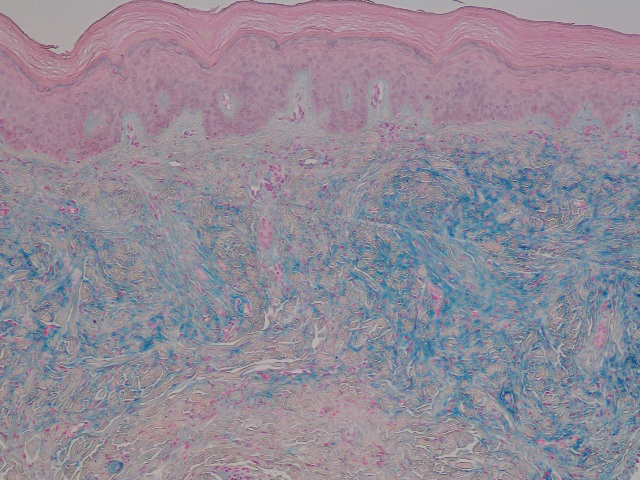

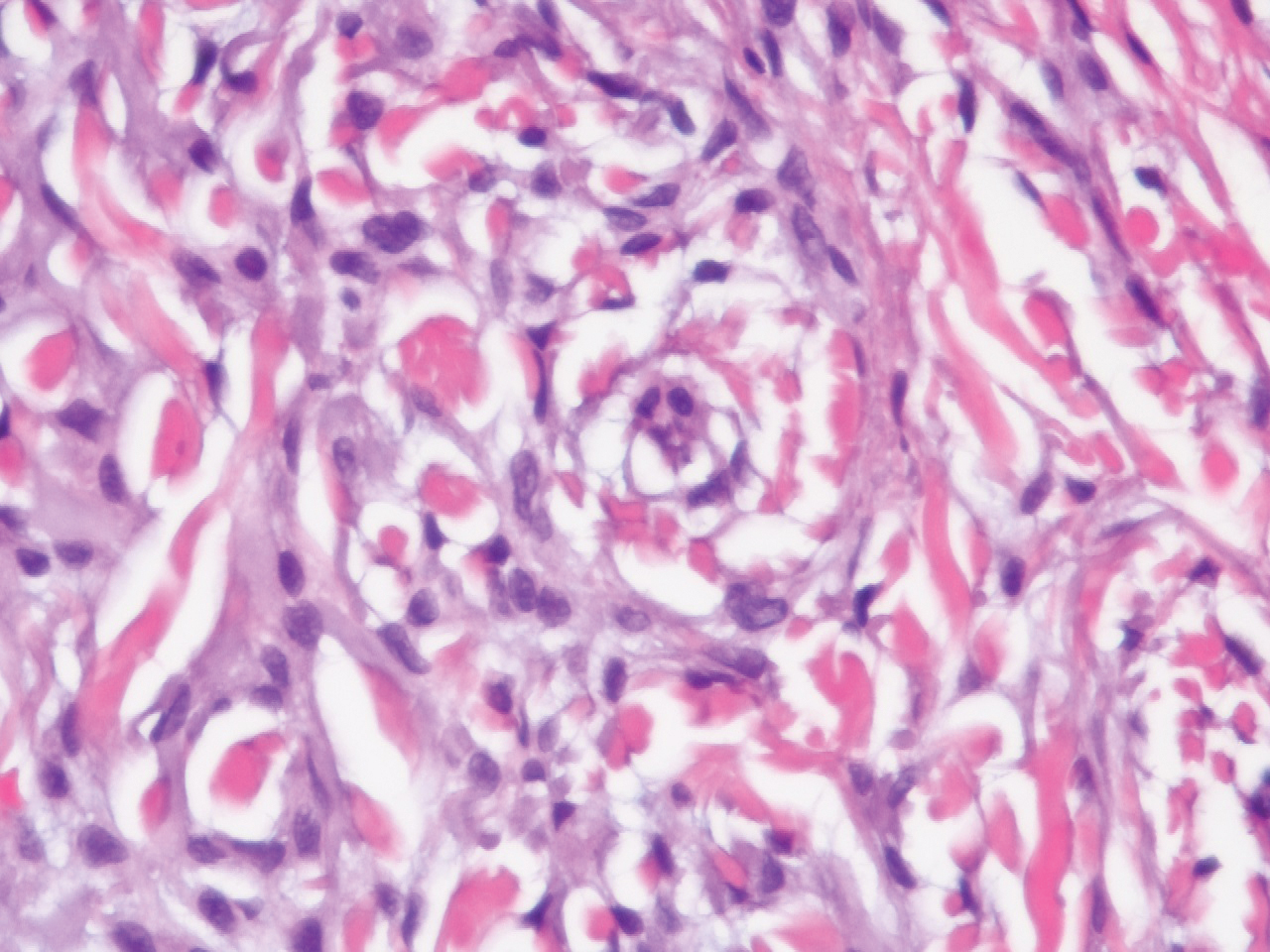

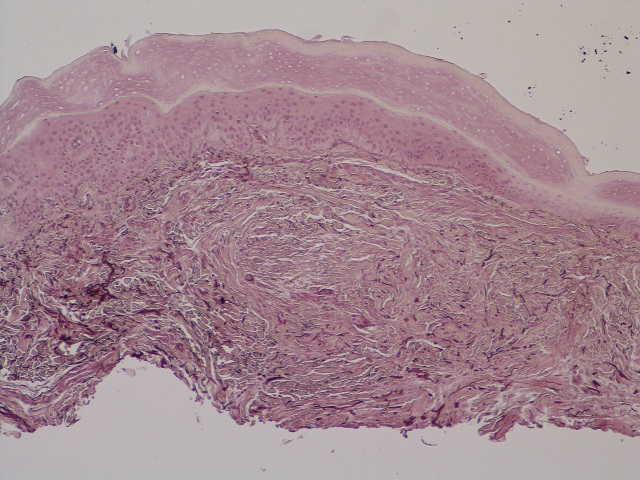

In this case, the patient exhibited the characteristic doughnut sign over the second interphalangeal joint of the right hand due to thickening and dimpling of the skin (quiz image). Histopathology from the right second finger showed the dermis with a spindled histiocytic infiltrate, fibroblasts, fibrosis, and increased interstitial mucin deposition highlighted with colloidal iron stain (Figures 1 and 2). Multinucleated giant cells also were seen in the dermis (Figure 3), and a Shikata orcein stain illustrated decreased elastic fibers (stained black) in the superficial dermis within areas of increased collagen deposition (Figure 4).

Scleromyxedema is strongly associated with a monoclonal gammopathy, which is generally mild and, in almost 80% of cases, related to λ IgG. However, the clinical implications are unclear.2,3 Scleromyxedema also is accompanied by systemic features, most commonly dysphagia, myalgias, and arthralgias, which distinguishes it from other cutaneous mucinoses. Notable morbidity and mortality are associated with involvement of the central nervous system, which can manifest as encephalopathy, seizures, or coma. Mucin deposition may be found in the myocardium and the coronary and pulmonary vasculature, resulting in rare cases of cardiac and pulmonary disease.4,5

Clinically, scleroderma also demonstrates progressive generalized skin tightening. Histopathology reveals hyalinization and thickening of the connective tissue of the deep dermis, subcutaneous fat, and muscular fascia. These changes are accompanied by a perivascular and focal interstitial lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate with prominent myofibroblast proliferation. In this case, the normal nail fold capillaries and absence of Raynaud phenomenon help to distinguish the diagnosis from scleroderma. In limited scleroderma, common findings include calcinosis, esophageal dysmotility, telangiectasia, and pulmonary hypertension, while systemic sclerosis can involve the internal organs, with the greatest morbidity stemming from interstitial lung disease.3,6,7

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is another disorder of skin thickening that involves the extremities and trunk. It is a rare complication of exposure to gadolinium contrast media in patients with advanced renal disease and those undergoing dialysis; use of gadolinium is now strictly avoided in patients with at least moderately impaired glomerular filtration rate.8 Although nephrogenic systemic fibrosis histologically looks similar to scleromyxedema, it involves deeper tissues. There is fibrosis with haphazard collagen bundle deposition in the deep dermis and subcutaneous septa. Fibroblasts and histiocytes are increased between the collagen bundles, with surrounding edema and mucin buildup. Multinucleated giant cells may or may not be present.9

Patients with scleredema present with nonpitting edema and dermal hardening over the neck, face, upper trunk, and arms. Lesional skin appears shiny and indurated. The skin is characteristically difficult to wrinkle, and the face may appear expressionless. Skin biopsy will show a thickened reticular dermis with mucin deposition and eccrine glands appearing in the upper third or mid dermis. Fibroblasts are normal in number. Scleredema generally is associated with poorly controlled diabetes, a monoclonal gammopathy, or as the aftermath of an acute infection, especially streptococcal pharyngitis. The condition may develop at any age, though nearly 50% of cases occur in children and adolescents.3,10

Interstitial granuloma annulare (GA) is a common, benign, and self-limiting dermatosis. Distinct from other skin-thickening disorders, GA is composed of smooth annular papules and plaques that do not result in skin hardening. Although GA may manifest in a generalized distribution, it is more frequently localized to the distal extremities.11 The presence of an inflammatory infiltrate surrounded by abundant mucin and collagen resembles scleromyxedema. However, GA is distinguished by palisading granulomas of histiocytes, fibroblasts, and lymphocytes lining a necrobiotic center of collagen, mucin, and fibrin.12

This patient's skin showed an immediate and marked response to intravenous immunoglobulin with dramatic softening. Such a response is well reported in the literature, and intravenous immunoglobulin is considered first-line therapy for scleromyxedema, typically in conjunction with steroids.5 Other immunosuppressive agents have been employed with reported efficacy, as have several treatments used for multiple myeloma, including thalidomide and lenalidomide.

Although spontaneous improvement infrequently occurs, a chronic progressive course is far more common with scleromyxedema. Studies are ongoing to elucidate the etiopathogenesis of scleromyxedema, scleroderma, and similar disorders to uncover the triggers that provoke the underlying dysregulation of dermal fibroblast activation and proliferation, which could offer a more precise target for effective treatments.5,13-15

- Crowe DR. Scleromyxedema. In: Crowe DR, Morgan M, Somach S, Trapp K, eds. Deadly Dermatologic Diseases: Clinicopathologic Atlas and Text. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016:139-142.

- Farmer ER, Hambrick GW Jr, Shulman LE. Papular mucinosis: a clinicopathologic study of four patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:9-13.

- Rongioletti F. Mucinoses. In: Smoller BR, Rongioletti F, eds. Clinical and Pathological Aspects of Skin Diseases in Endocrine, Metabolic, Nutritional and Deposition Disease. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2010:139-152.

- Gabriel PH, Oleson GB, Bowles GA. Scleromyxoedema: a scleroderma-like disorder with systemic manifestations. Medicine. 1988;67:58-65.