User login

Translucent Periorbital Papules

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

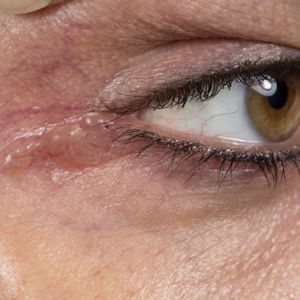

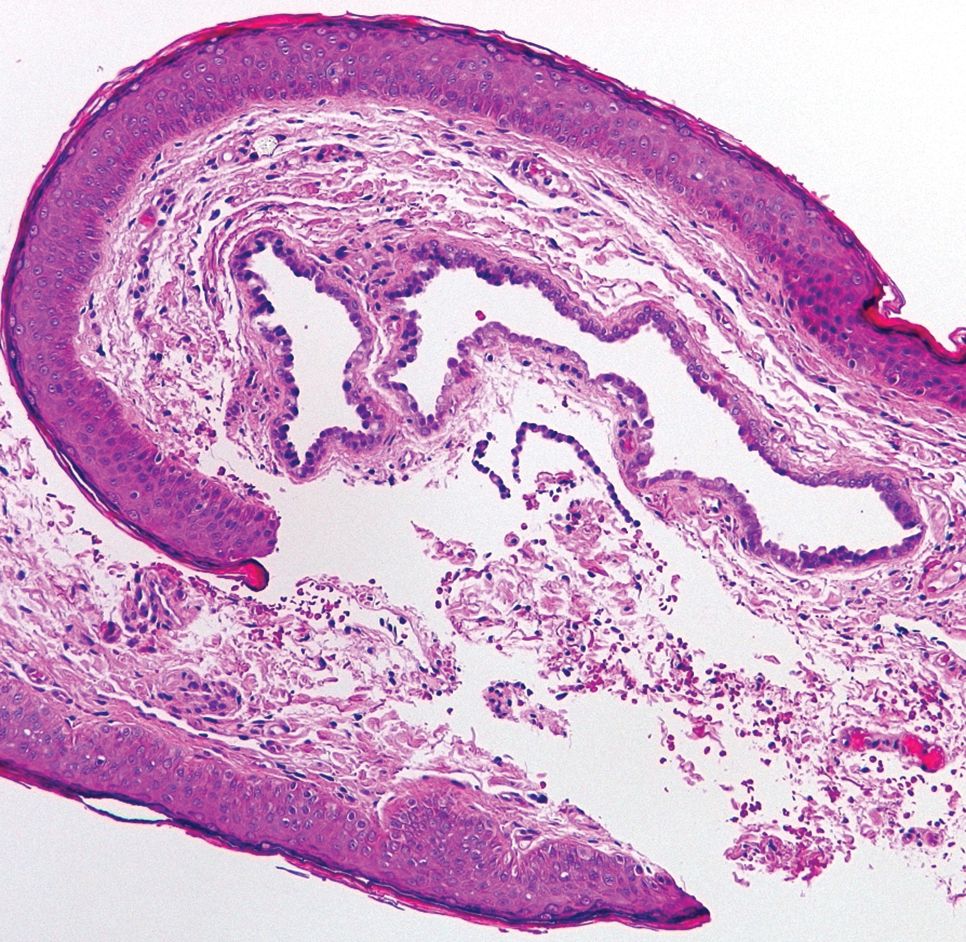

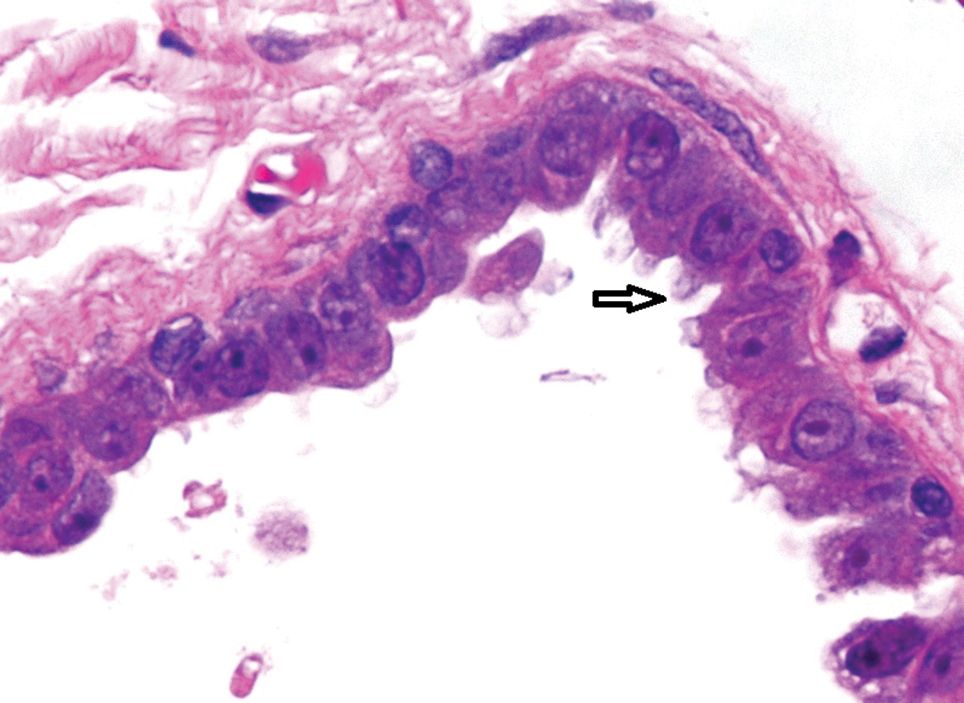

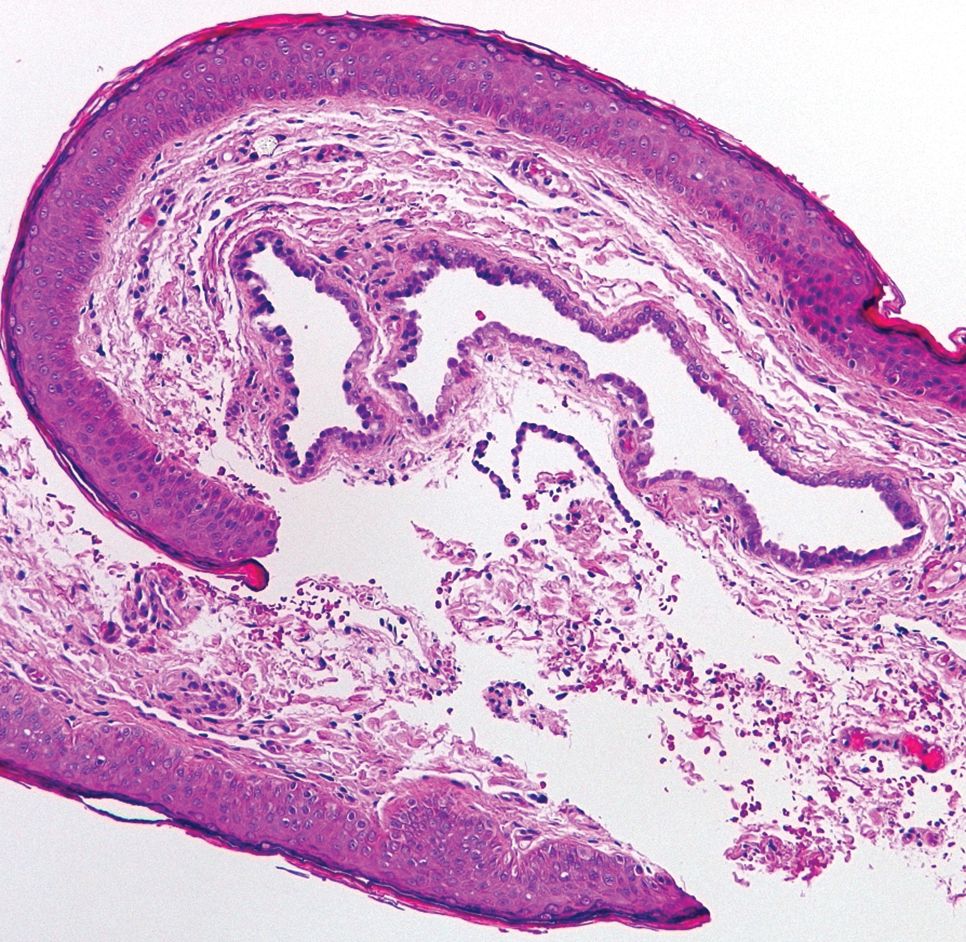

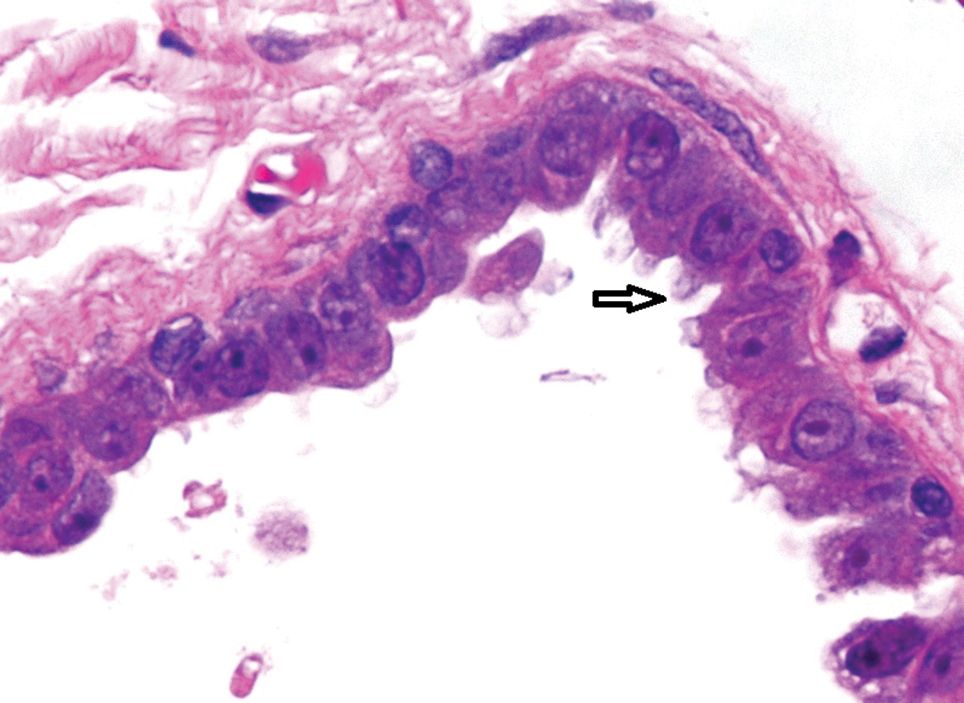

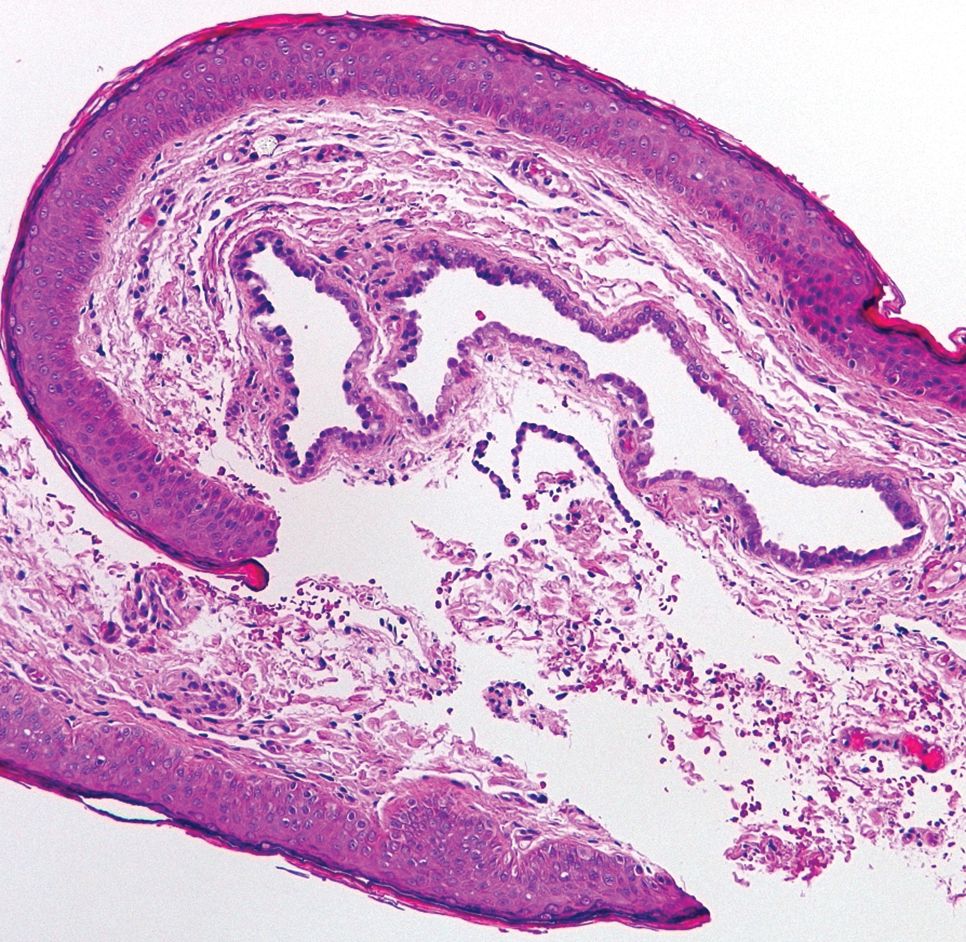

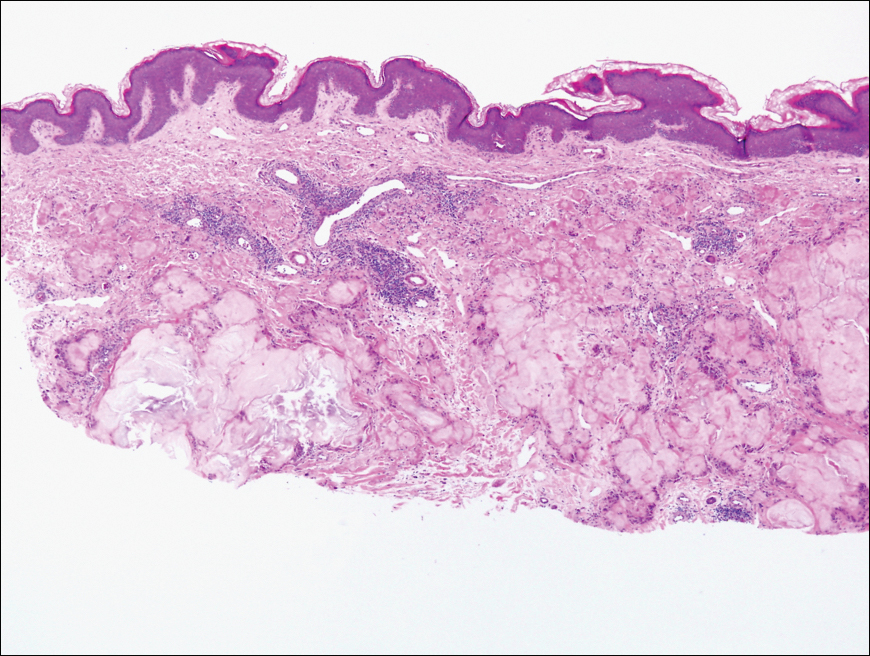

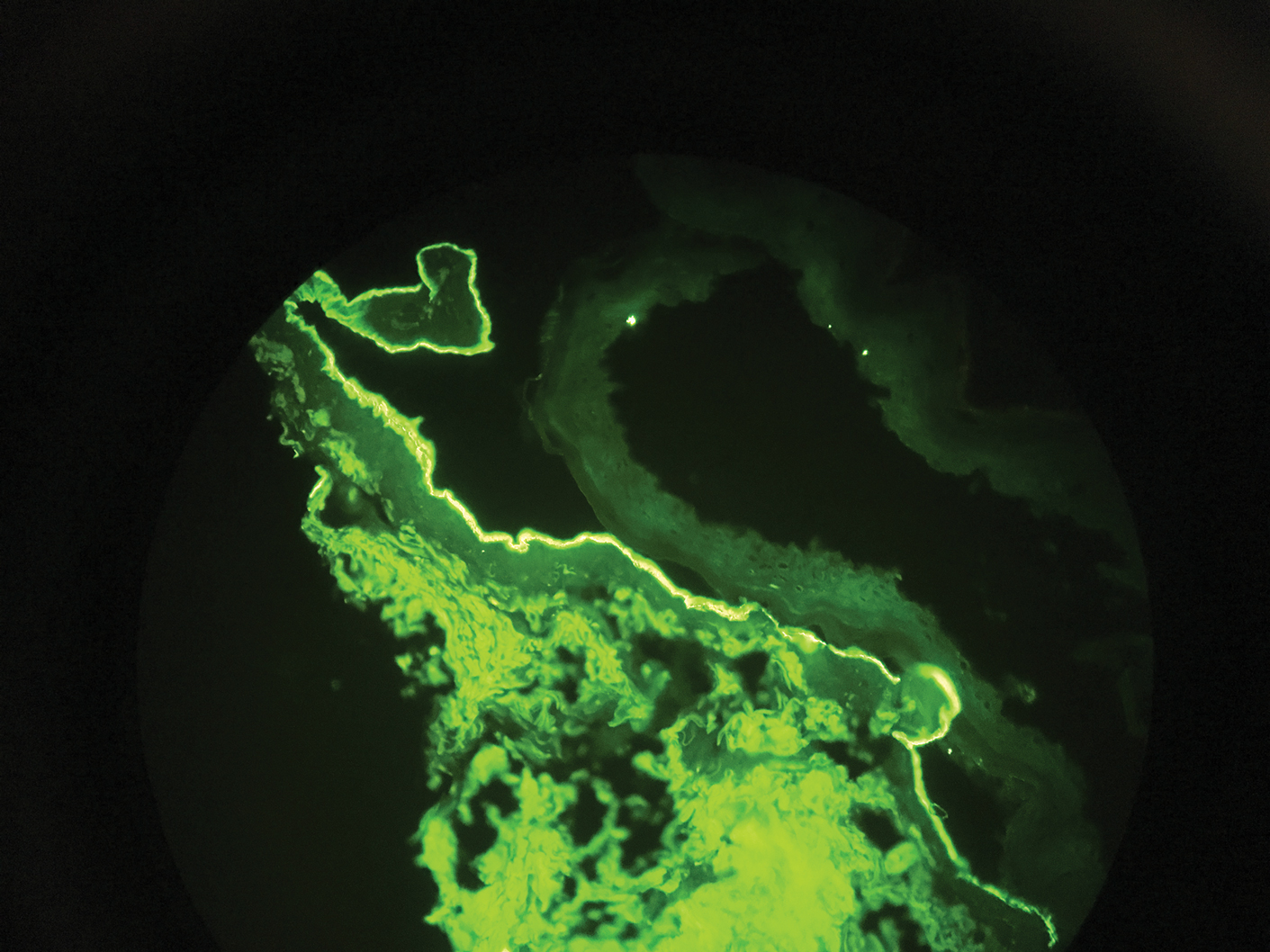

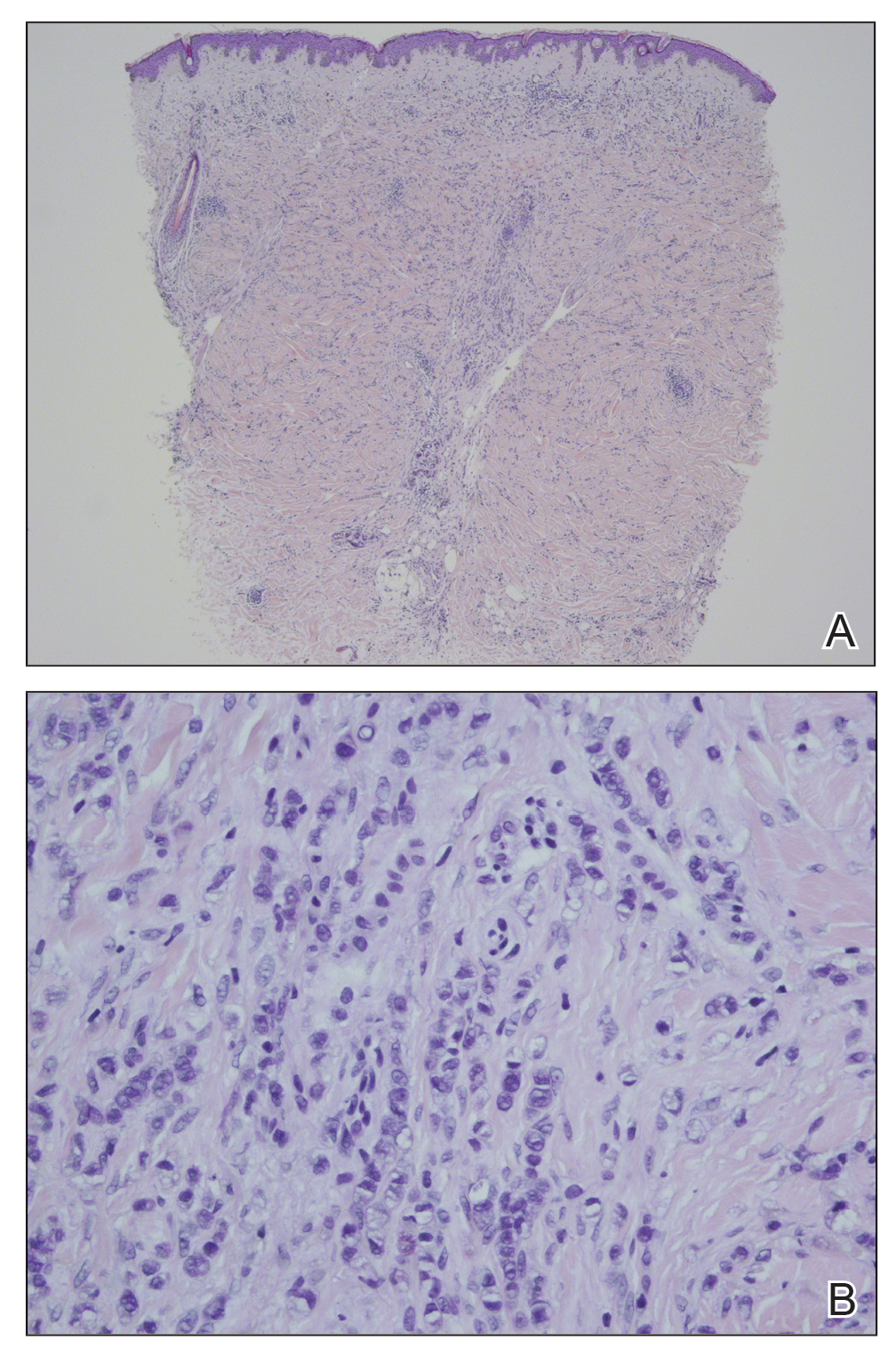

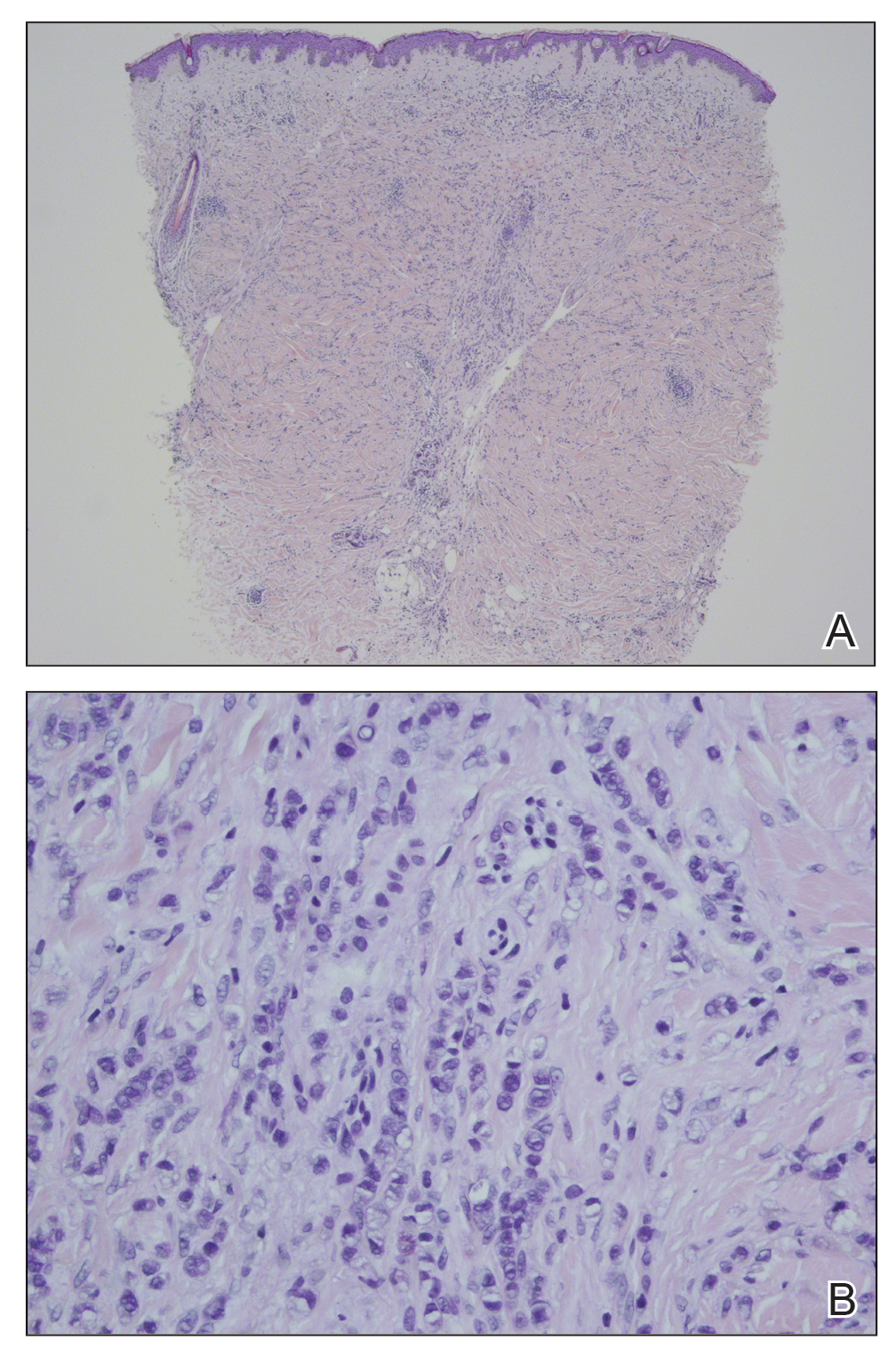

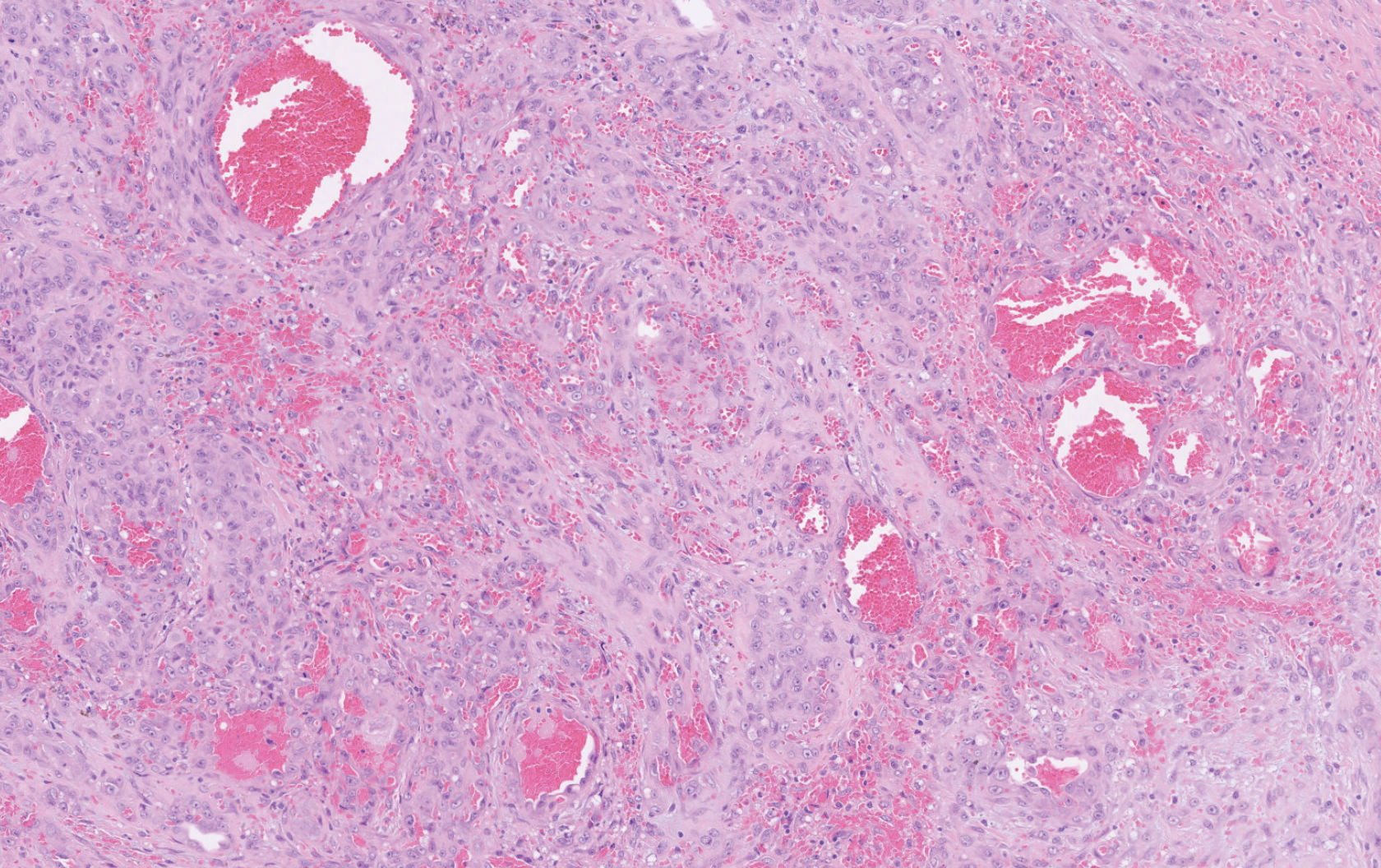

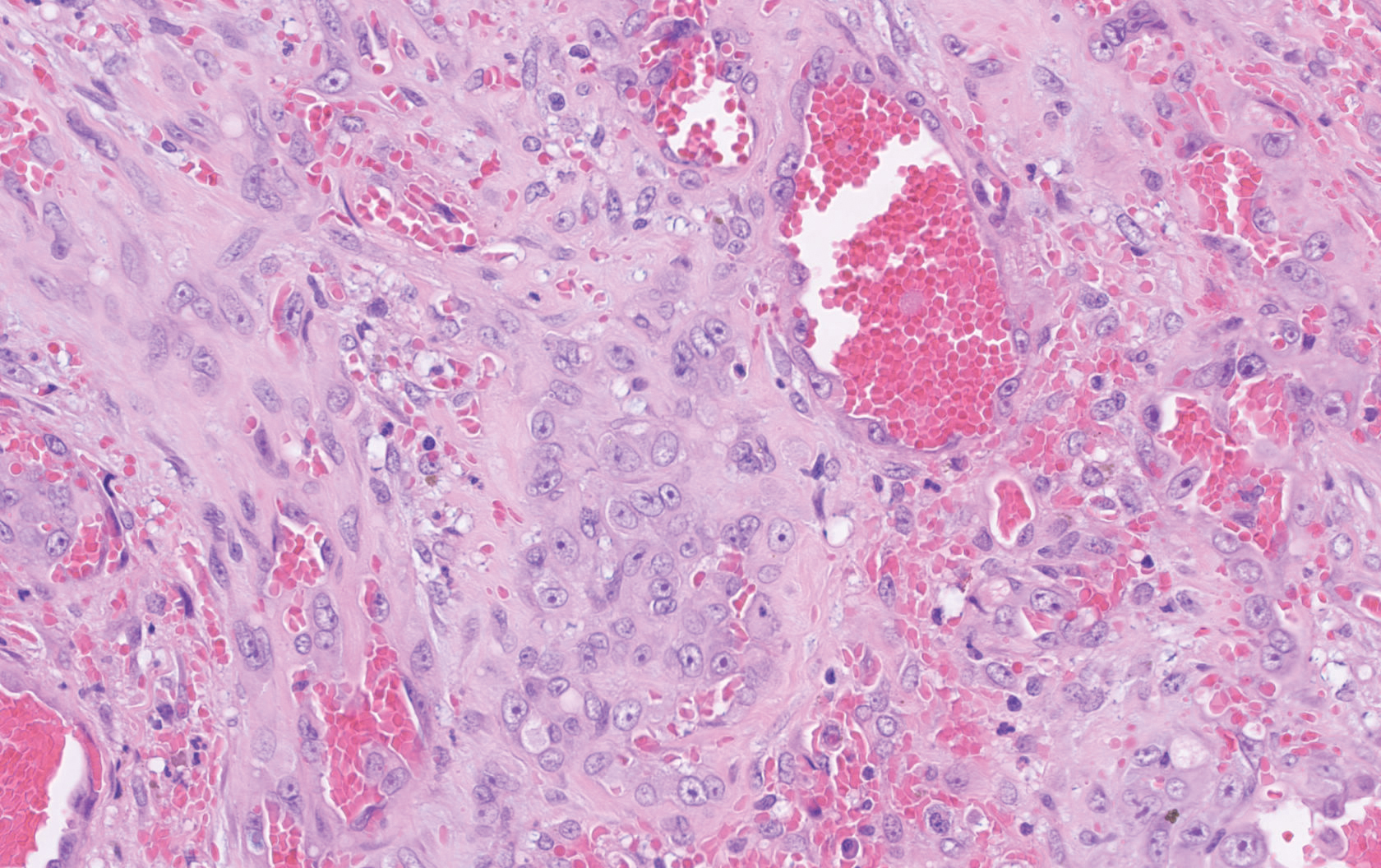

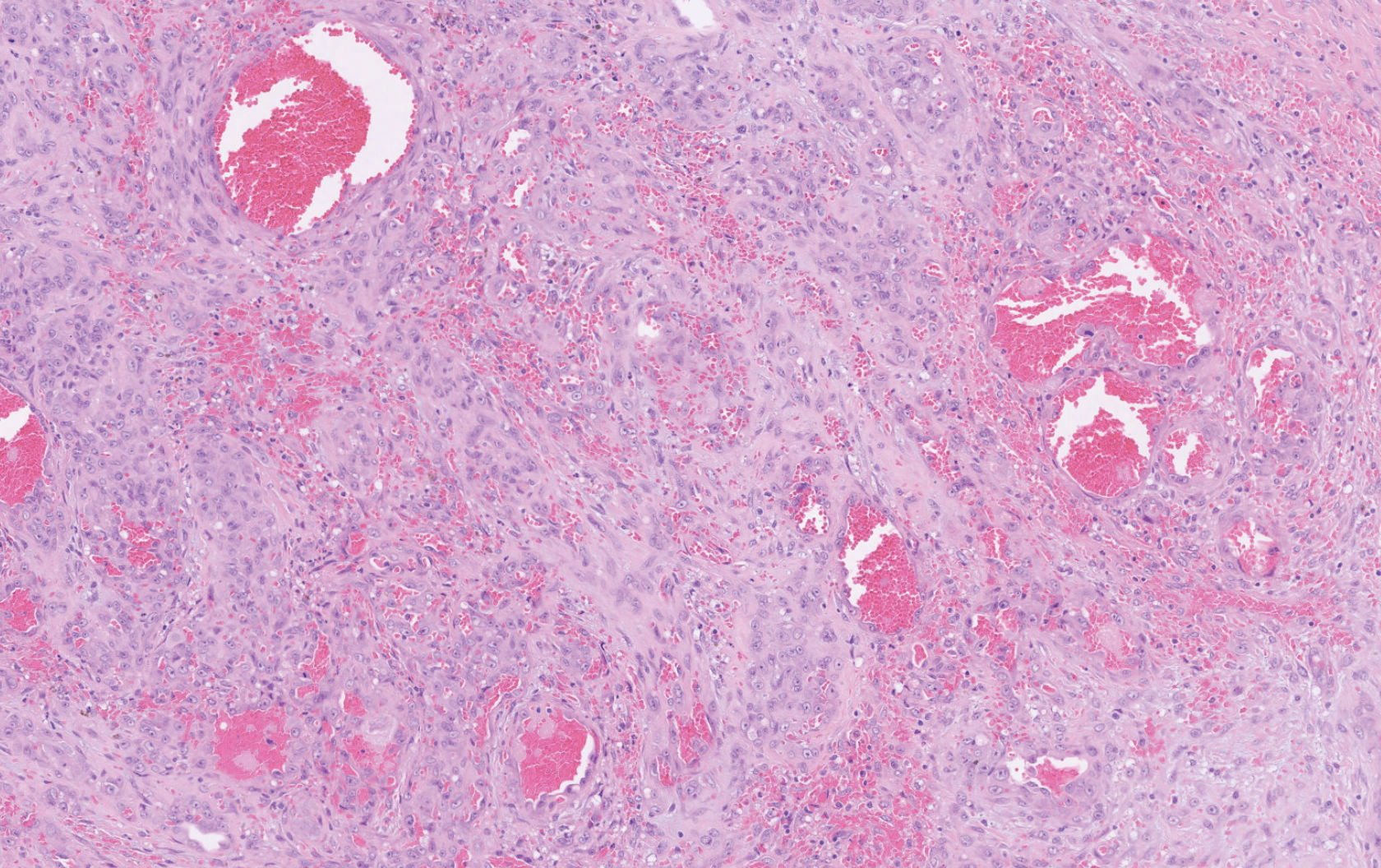

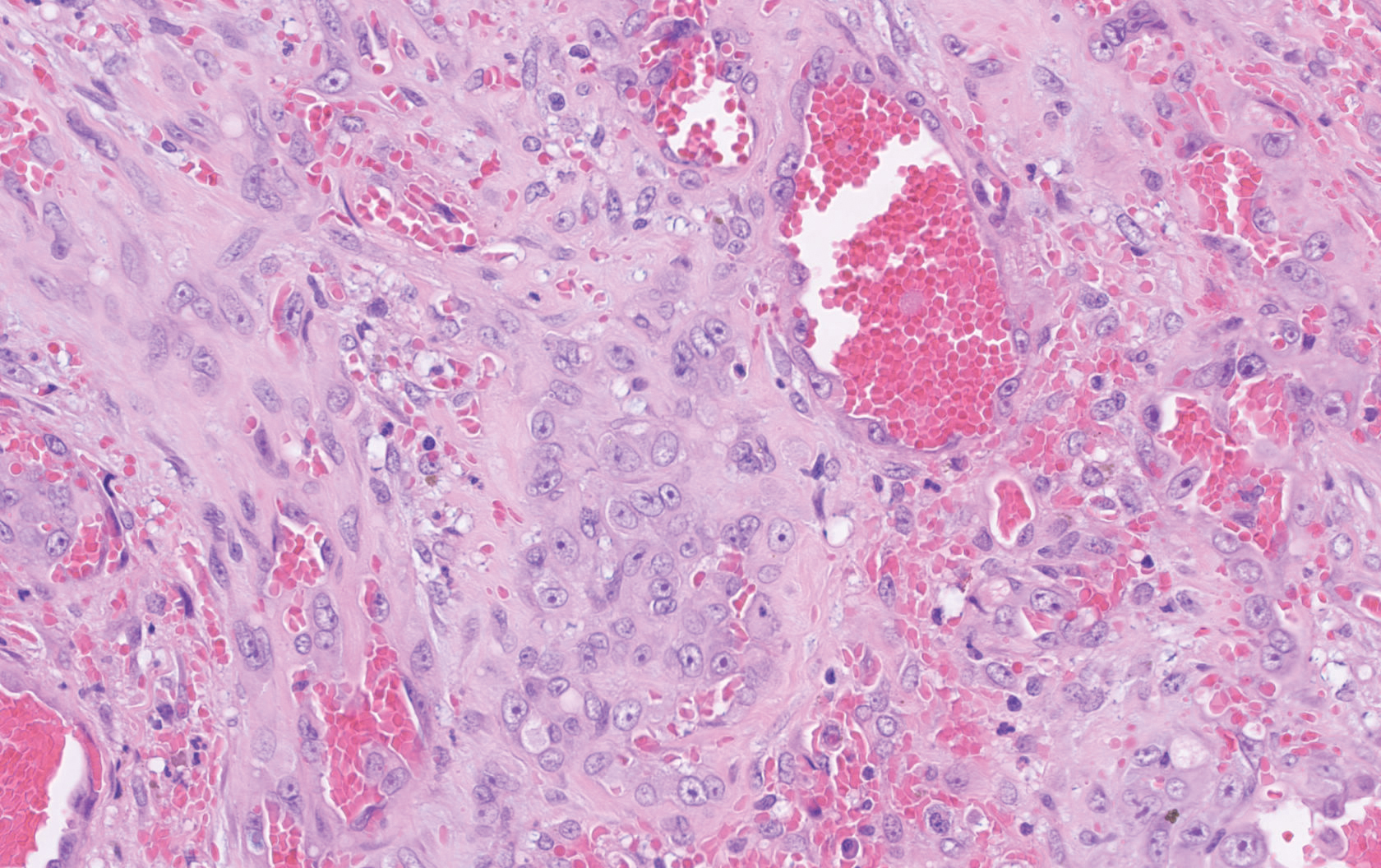

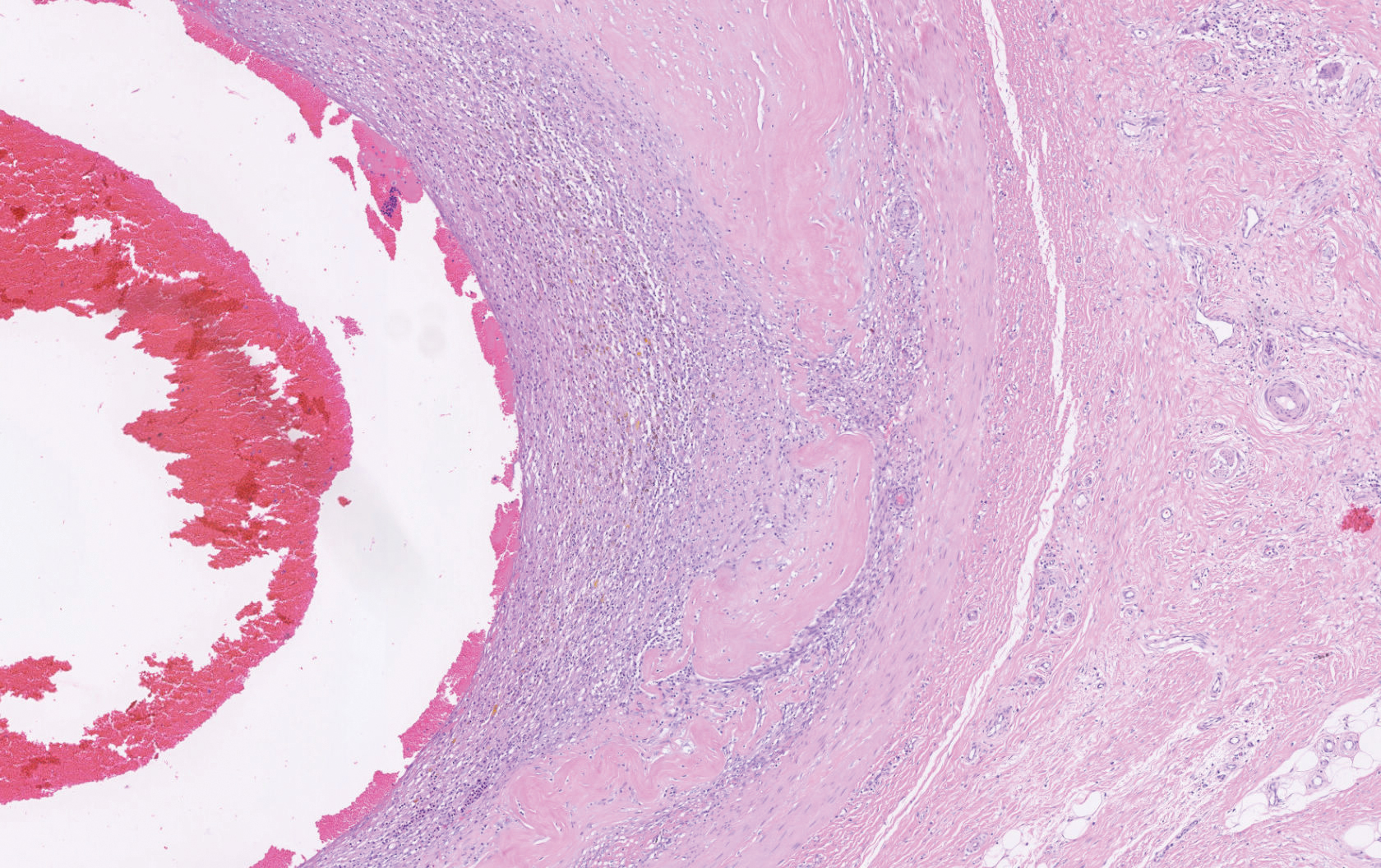

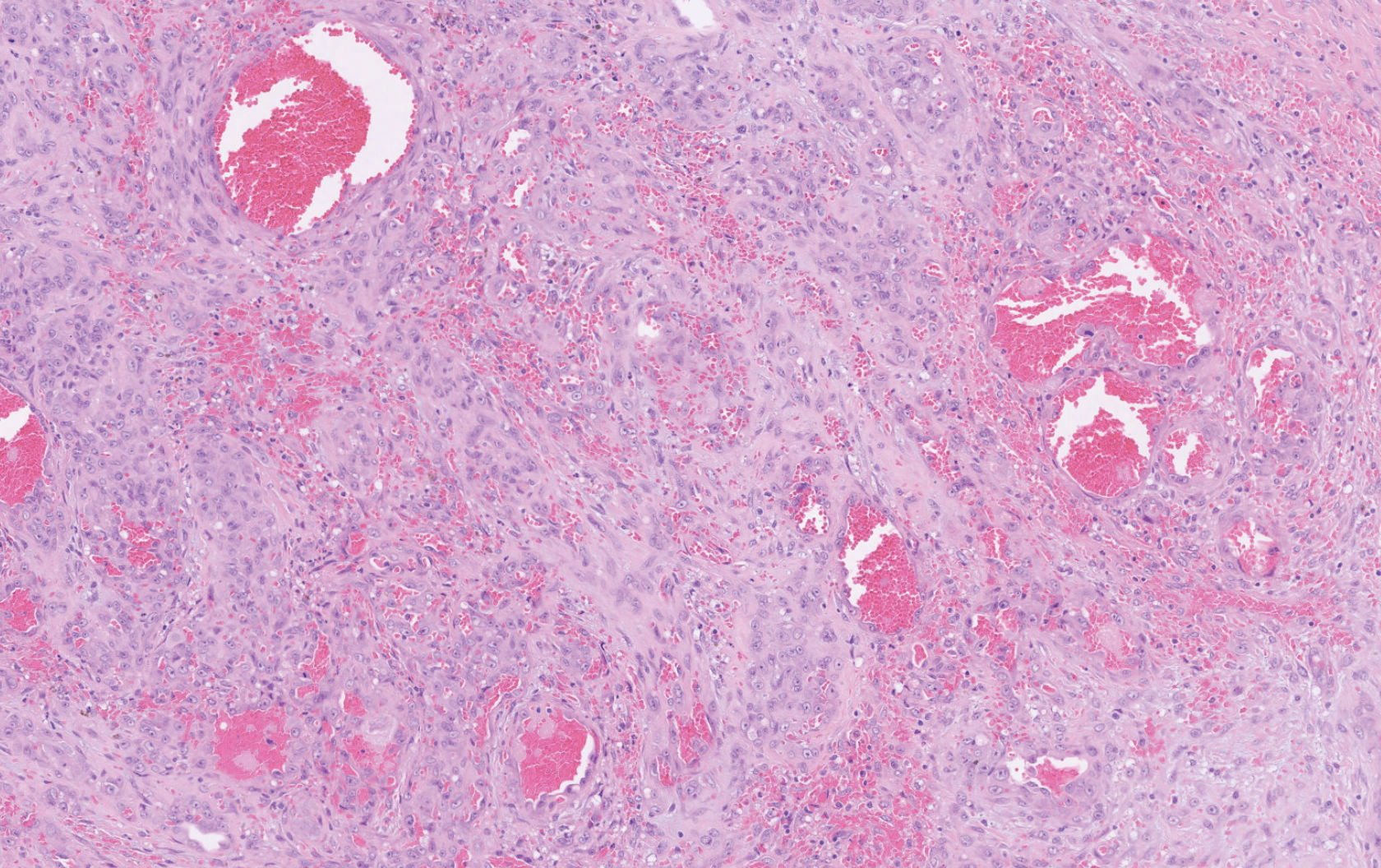

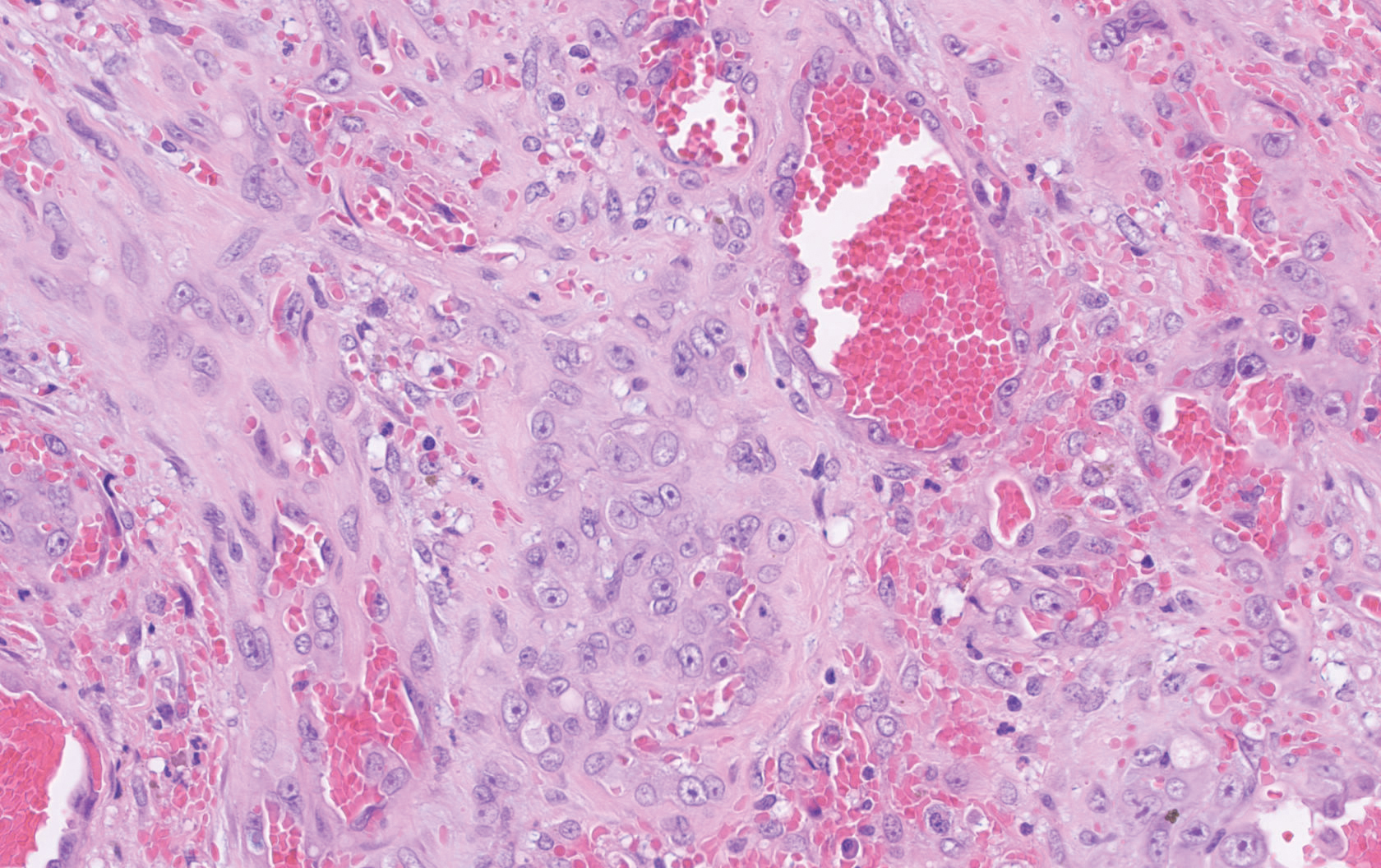

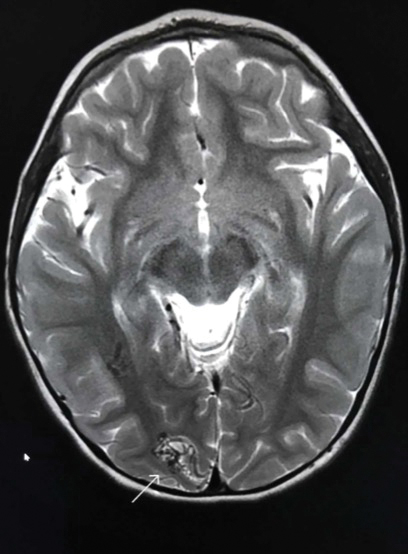

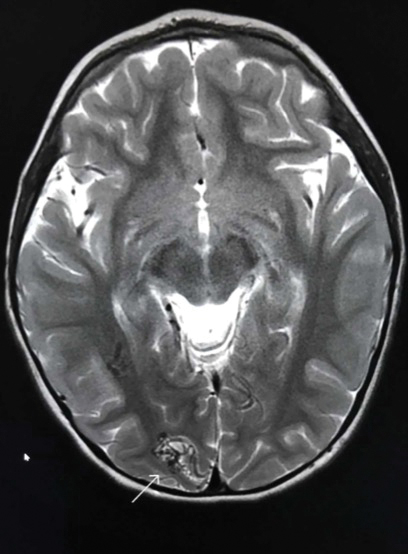

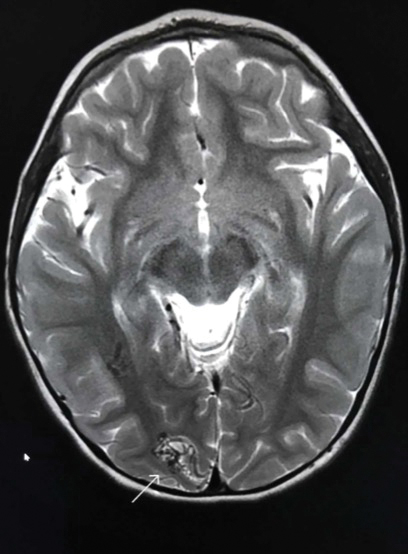

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

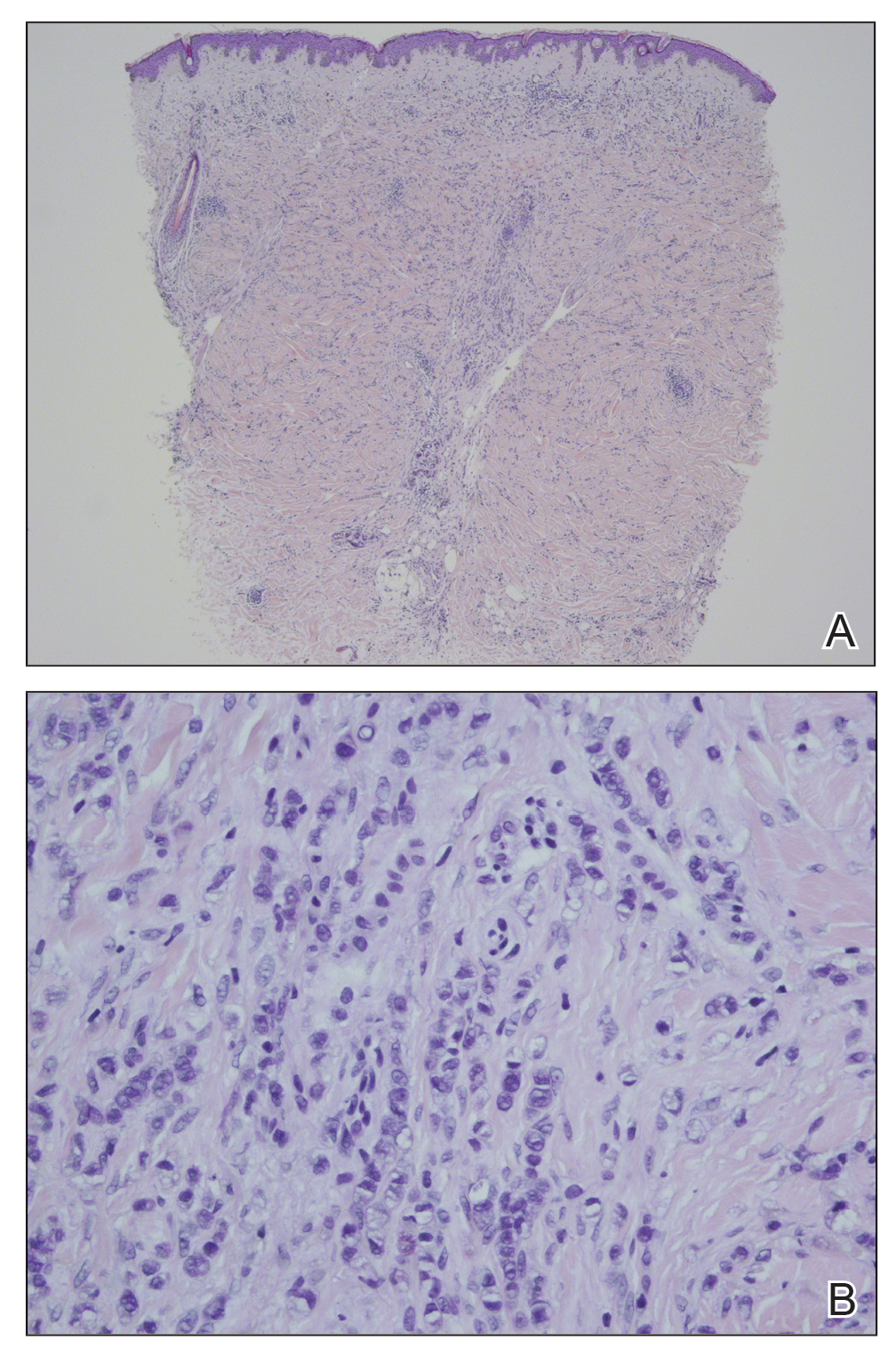

A 40-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of occasionally pruritic periorbital papules that had gradually increased in size and number over the last 7 to 8 months (top). She had a similar solitary lesion on the left lower eyelid that was removed twice: 10 years and 10 months prior. She was taking an oral contraceptive (desogestrel) but otherwise had no notable medical history or drug allergies. Physical examination revealed individual and clustered translucent papules along the eyelid margins, left medial canthus, and both lateral canthi (bottom).

Solitary Warty Mucosal Lesion on the Hard Palate

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

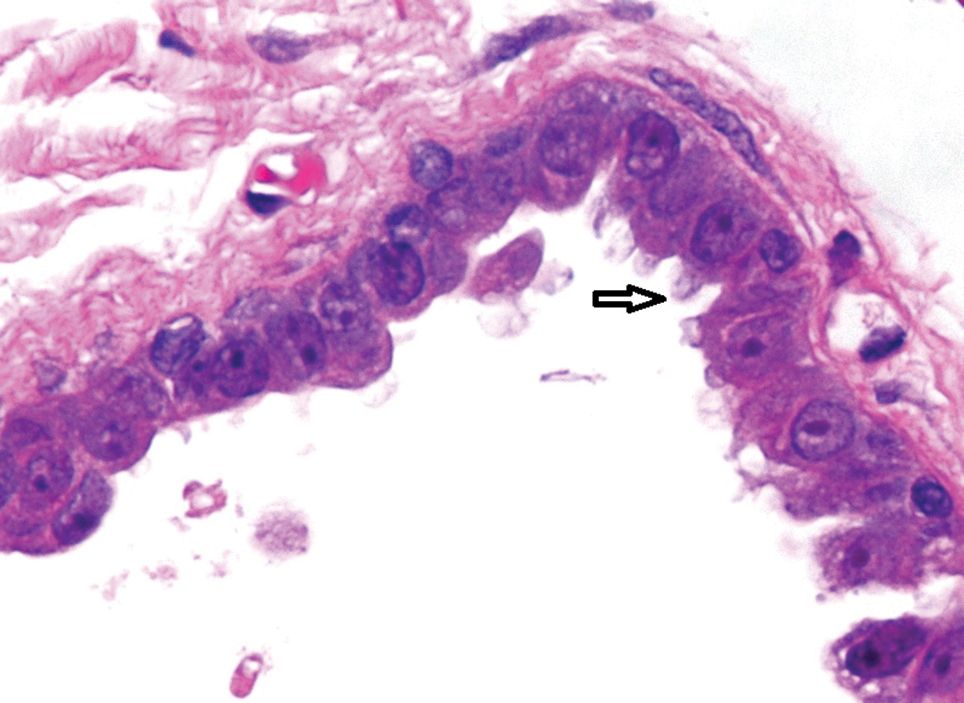

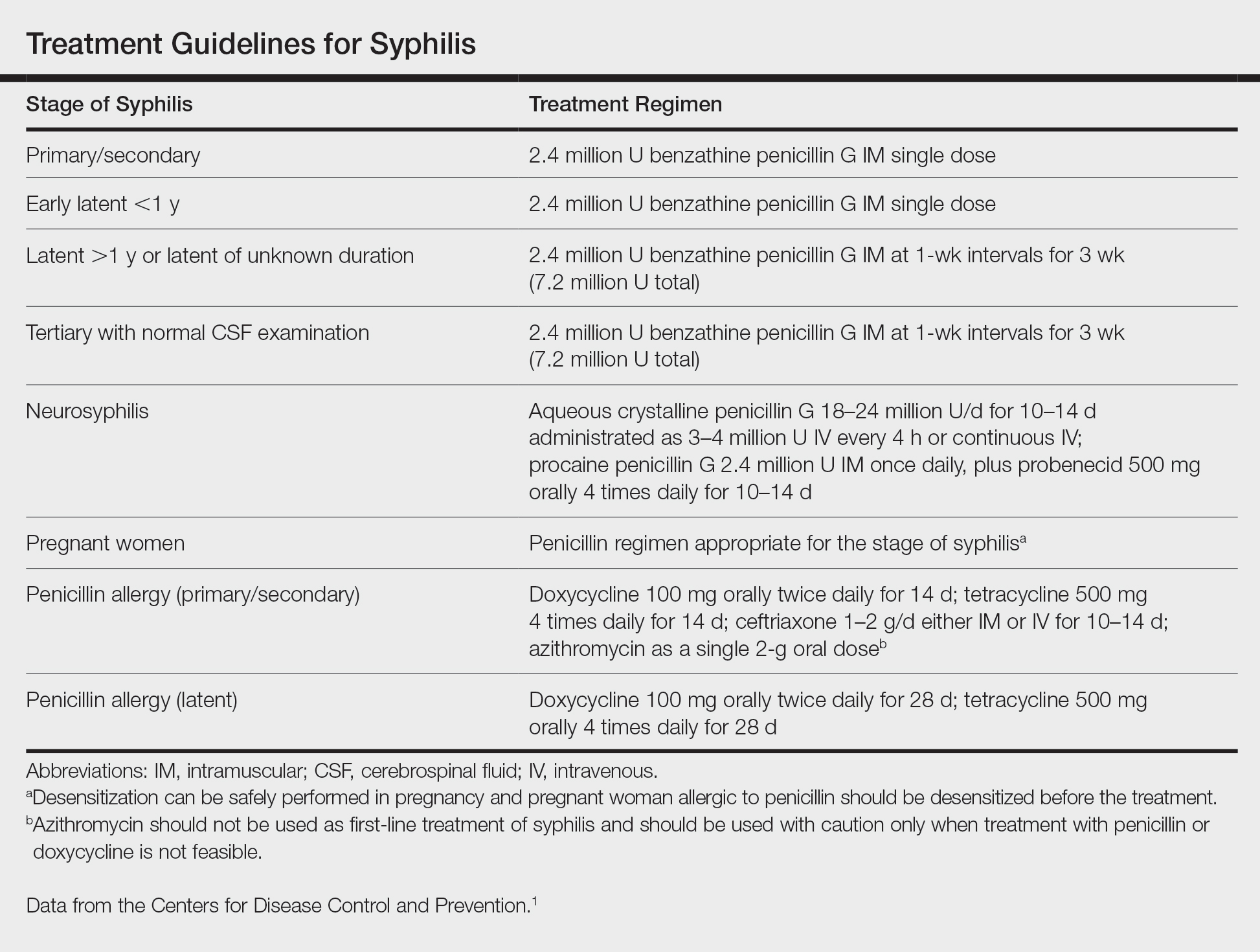

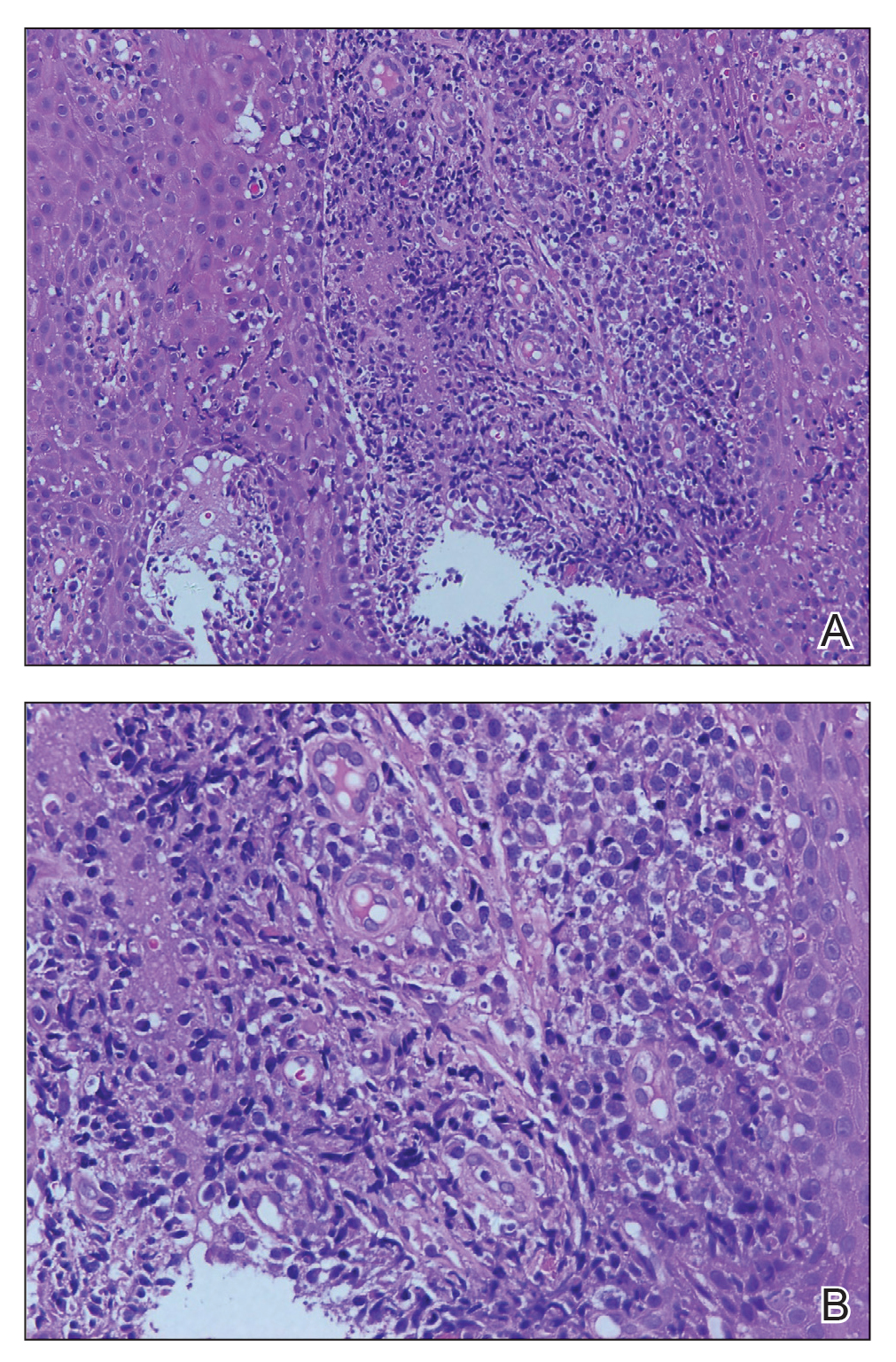

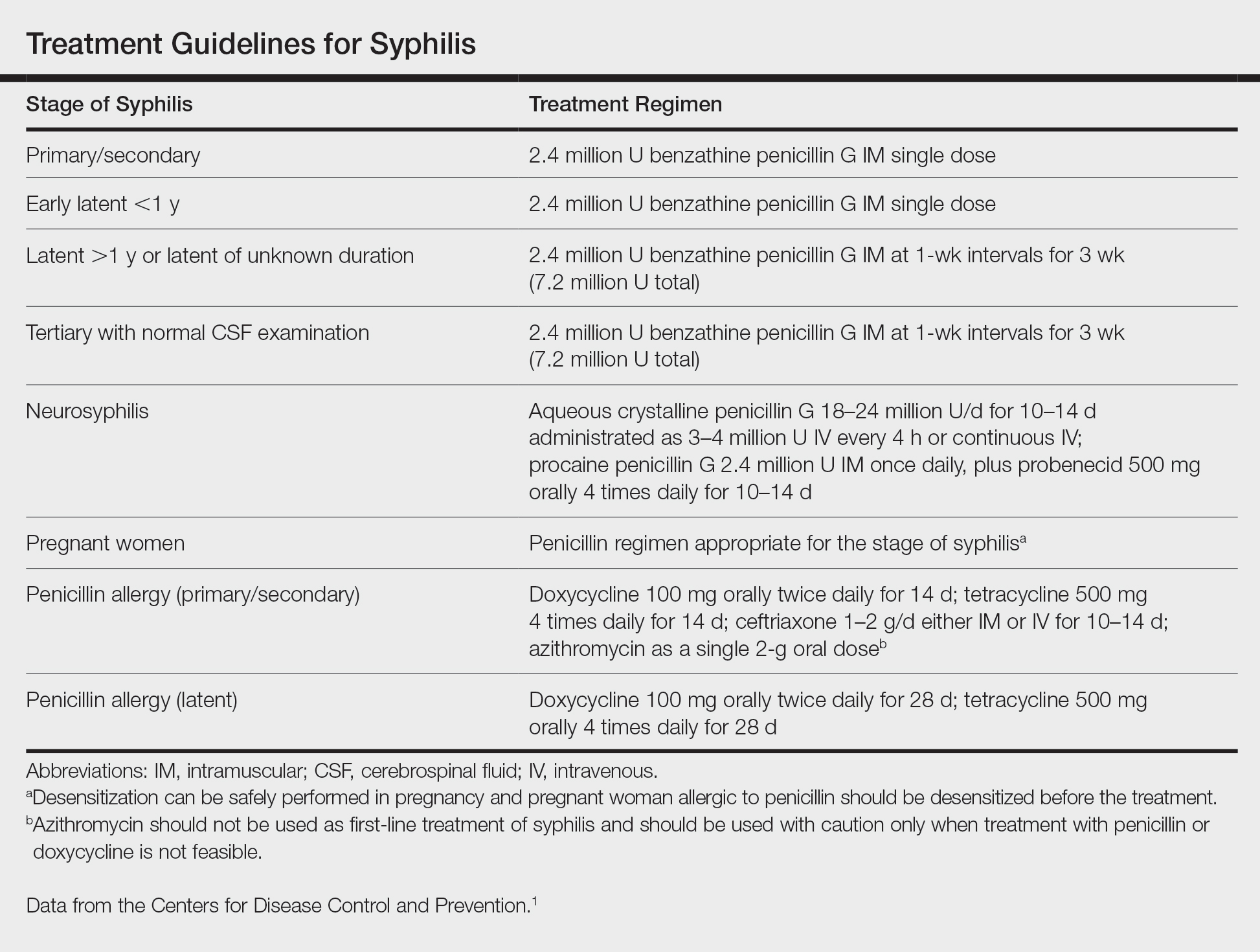

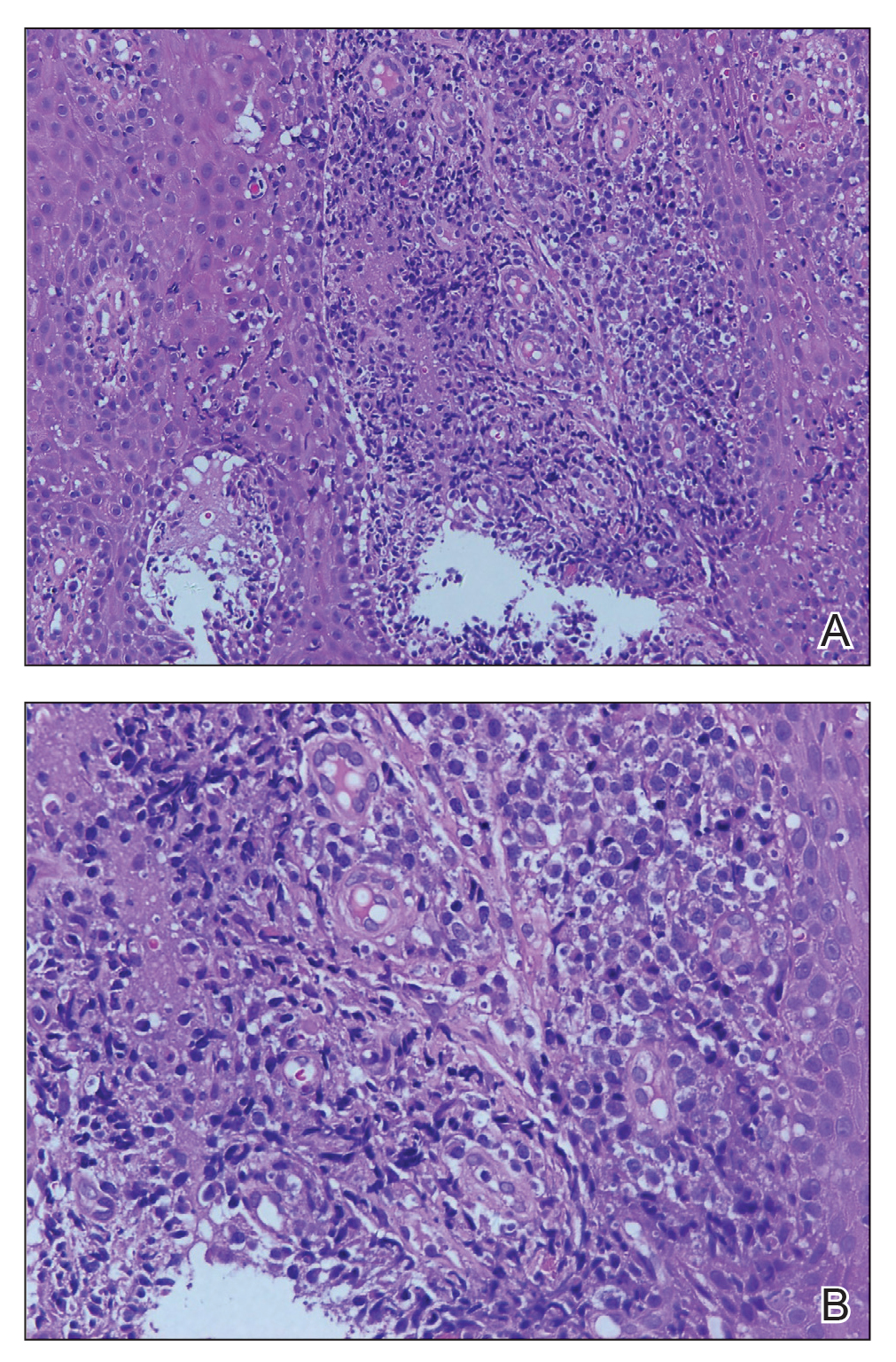

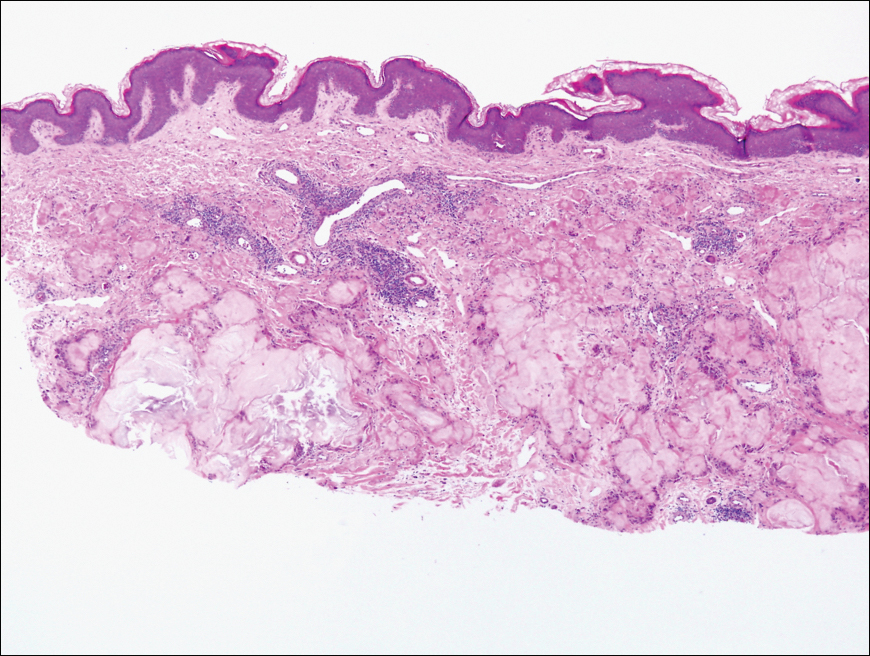

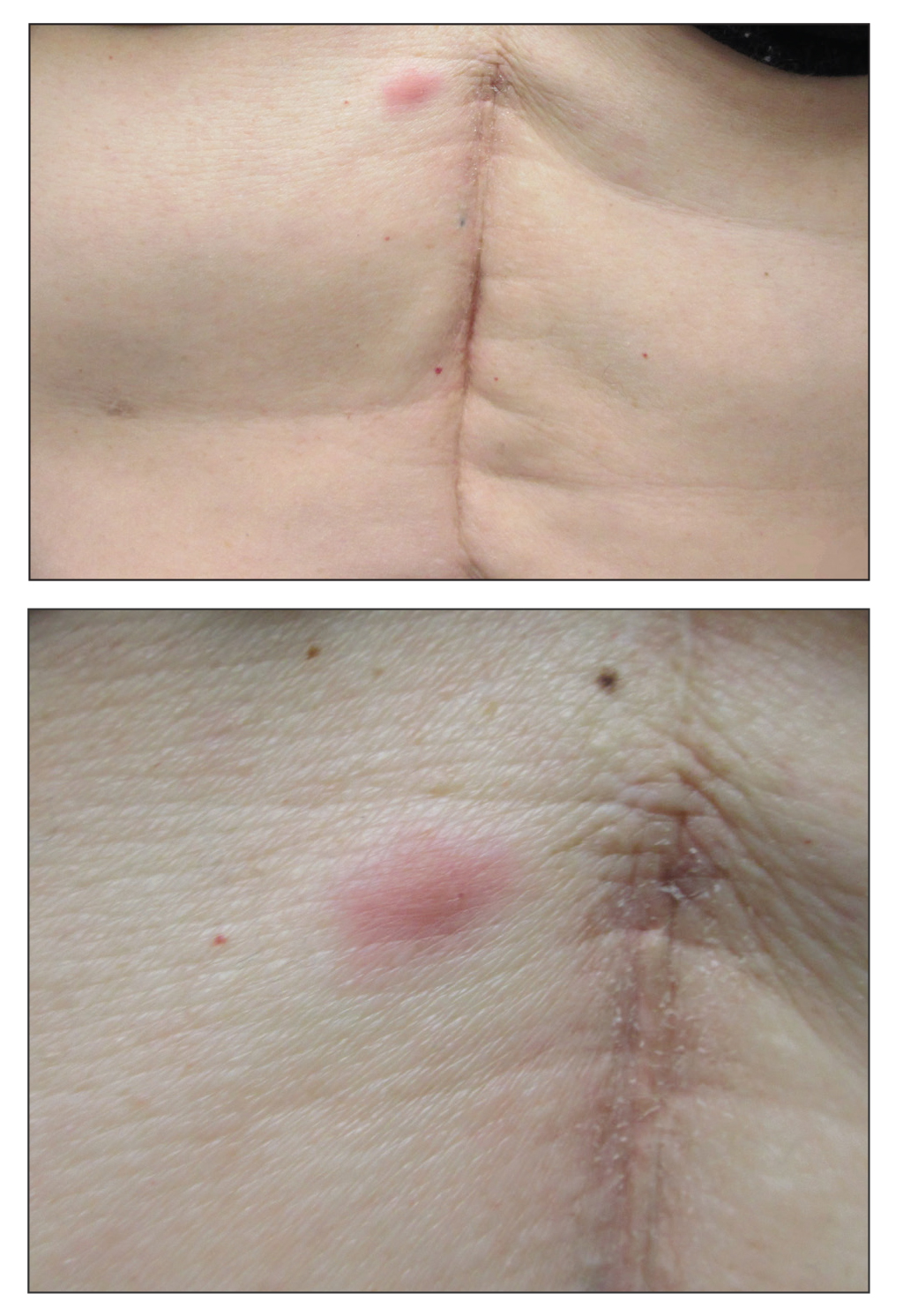

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Oral Condyloma Lata of Secondary Syphilis

A punch biopsy of the lesion revealed acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges; interface dermatitis; and a moderately dense, predominantly lymphoid dermal infiltration (Figure). Based on a serologic toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) titer of 1:64 and positive Treponema antibodies, a diagnosis of secondary syphilitic infection was made. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection was negative, and the patient was not immunocompromised. Due to allergy to benzathine penicillin G, she was prescribed oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily for 15 days. (See the Table for current recommended regimens from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the treatment of syphilis.1) The hard palate plaque began to fade after 2 days of treatment and completely regressed 2 weeks later. The TRUST titer decreased to 1:4 after 6 months.

The patient's husband was examined following confirmation of his wife's infection; his TRUST titer was 1:64 and Treponema antibodies were positive. No skin lesions were detected. A test for human immunodeficiency virus infection also was negative. Further inquiry revealed that he had had sexual intercourse with a prostitute about 3 months prior. He was diagnosed with latent syphilis and prescribed the same medication regimen as his wife. However, after 6 months, his TRUST titer was still 1:64, possibly due to irregular medication use.

Secondary syphilis often is preceded by flulike symptoms of fever, sore throat, headache, malaise, generalized painless lymphadenopathy, and myalgia 4 to 10 weeks after onset of infection.2-5 Condyloma lata can be one of the characteristic mucosal signs of secondary syphilis; however, it is typically located in the anogenital area or less commonly in atypical areas such as the umbilicus, axillae, inframammary folds, and toe web spaces.6 Condyloma lata in the oral cavity is rare. In fact, this unusual manifestation prompted the patient to suspect cancer and she initially presented to a local tumor hospital. However, oral computed tomography did not detect any tumor cells, and subsequent testing yielded the diagnosis of secondary syphilis.

The differential diagnosis for a warty oral mass includes squamous cell carcinoma, condyloma acuminatum, oral submucous fibrosis, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Similar to other nontreponemal tests, TRUST is a flocculation-based quantitative test that can be used to follow treatment response, as its antibody titers may correlate with disease activity.7 Clinically, a 4-fold change in titer (equivalent to a change of 2 dilutions) is considered necessary to demonstrate a notable difference between 2 nontreponemal test results obtained using the same serologic test. The TRUST titers for the case patient decreased from 1:64 to 1:4, indicating a good response to minocycline. In contrast, the TRUST of her husband remained as high at 6-month follow-up as it had been at initial examination. This serofast state was most likely related to his irregular medication use; however, other possibilities should be considered, including confounding nontreponemal inflammatory conditions in the host, the variability of host response to infection, or even persistent low-level infection with Treponema pallidum.8 Because treponemal antibodies typically remain positive for life and most patients who have a reactive treponemal test will have a reactive report for the remainder of their lives, regardless of treatment or disease activity, treponemal antibody titers should not be used to monitor treatment response.9

China has experienced a resurgence in the incidence and prevalence of syphilis in recent decades. According to the national reporting database, the annual rate of syphilis in China has increased 14.3% since 2009 (6.5 cases per 100,000 population in 1999 vs 24.66 cases per 100,000 population in 2009).10 This re-emergence is truly remarkable, given this infection was virtually eradicated in the country 60 years ago. Recognizing this syphilis epidemic as a public health threat, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China in 2010 announced a 10-year plan for syphilis control and prevention to curb the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, the syphilis burden is still great, with 25.54 cases per 100,000 population in 2016,11 but the situation has been stabilized and the annual increase is less than 1% since the plan's introduction.

Globally, there has been a marked resurgence of syphilis in the last decade, largely attributed to changing social and behavioral factors, especially among the population of men who have sex with men. Despite the availability of effective treatments and previously reliable prevention strategies, there are an estimated 6 million new cases of syphilis in those aged 15 to 49 years, and congenital syphilis causes more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths each year.12 Continued vigilance and investment is needed to combat syphilis worldwide, and recognition of syphilis, with its versatile presentations, is of vital importance today.13

The presentation of secondary syphilis can be highly variable and requires a high level of awareness.4-6 Solitary oral involvement in secondary syphilis is rare and can lead to misdiagnosis; therefore, a high level of suspicion for syphilis should be maintained when evaluating oral lesions.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 SexuallyTransmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Syphilis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- Lombardo J, Alhashim M. Secondary syphilis: an atypical presentation complicated by a false negative rapid plasma reagin test. Cutis. 2018;101:E11-E13.

- Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

- Dourmishev LA, Assen L. Syphilis: uncommon presentations in adults. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:555-564.

- Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF. Dermatological manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases other than HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:533-583.

- Liu Z, Wang L, Zhang G, et al. Warty mucosal lesions: oral condyloma lata of secondary syphilis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:277.

- Morshed MG, Singh AE. Recent trends in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:137-147.

- Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Response to therapy following retreatment of serofast early syphilis patients with benzathine penicillin. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:420-422.

- Rhoads DD, Genzen JR, Bashleben CP, et al. Prevalence of traditional and reverse-algorithm syphilis screening in laboratory practice: a survey of participants in the College of American Pathologists syphilis serology proficiency testing program. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:93-97.

- Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China's syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:50-55.

- Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;17:716-725.

- Noah K, Jeffrey DK. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5:24-38.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

A 50-year-old Chinese woman presented with a painless, well-demarcated, nontender, elevated, flat-topped verrucous plaque on the hard palate of 1 month's duration. The lesion measured 2 cm in diameter. The patient reported no other dermatologic or systemic concerns, and no other skin or genital lesions were observed.

Multinodular Plaque on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Tophaceous Gout

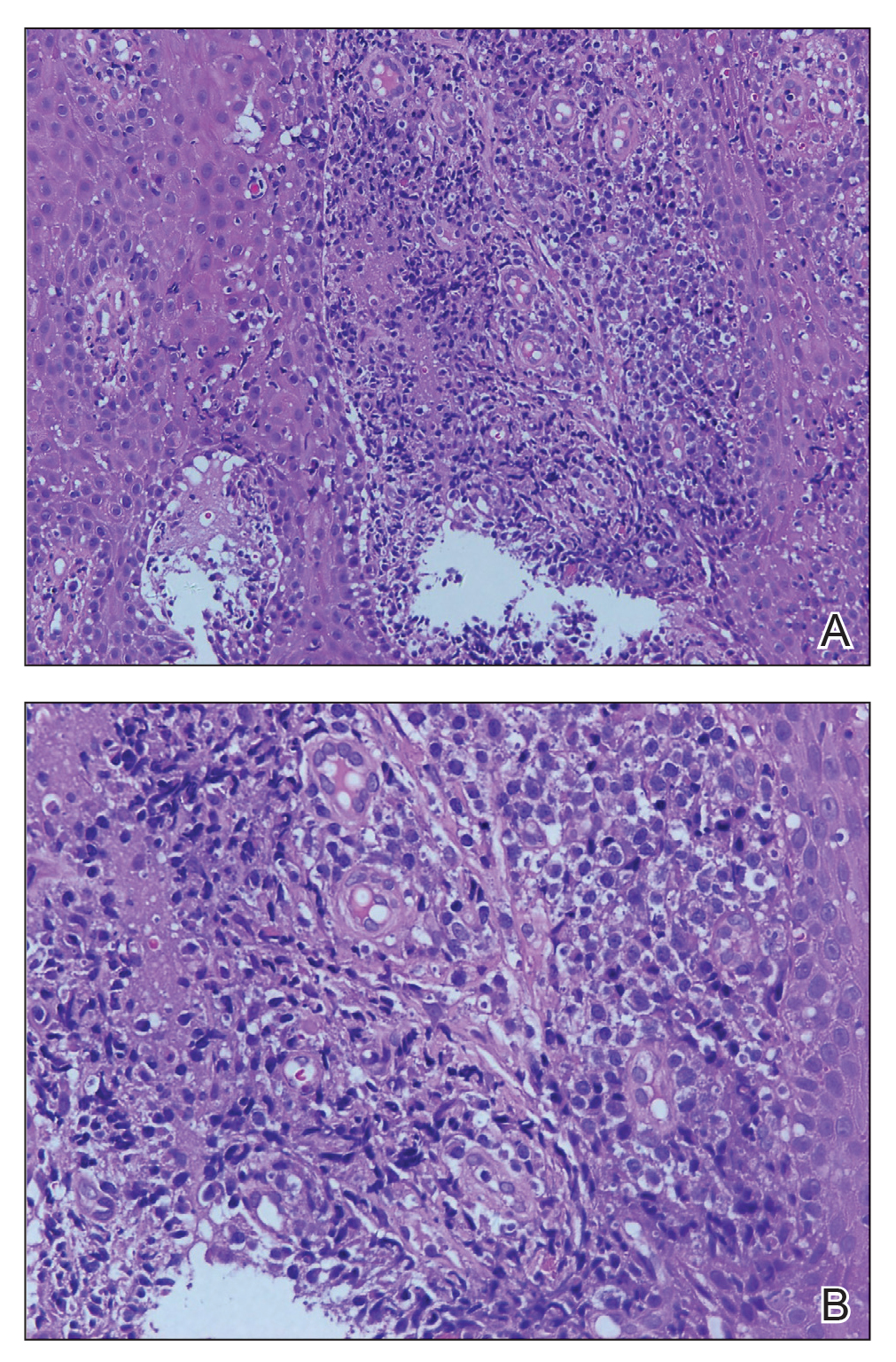

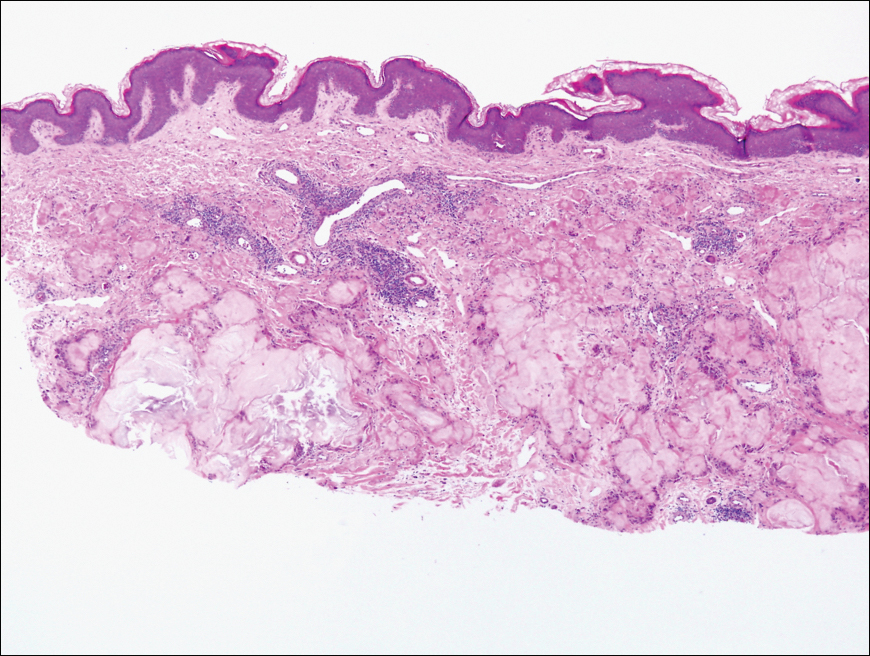

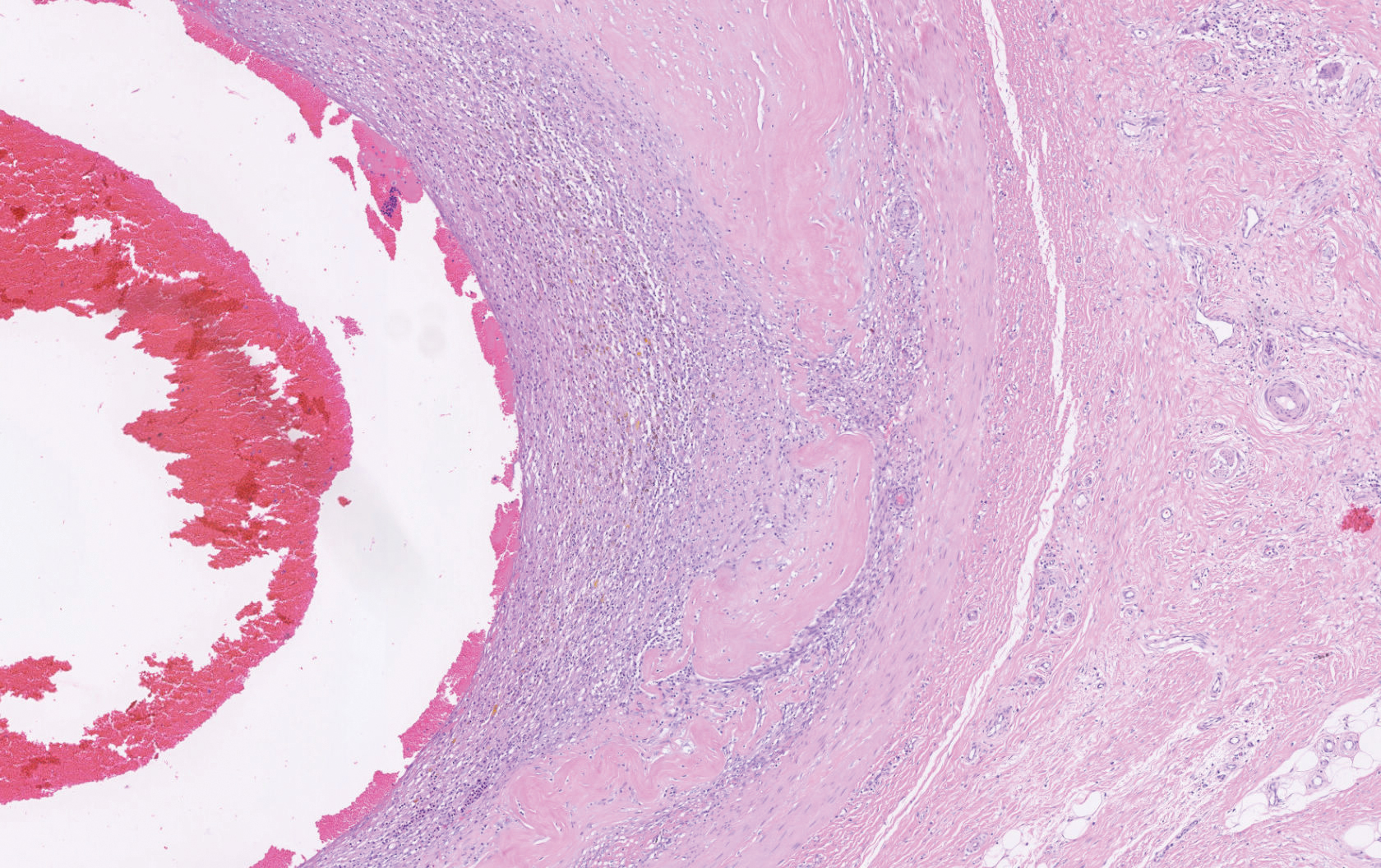

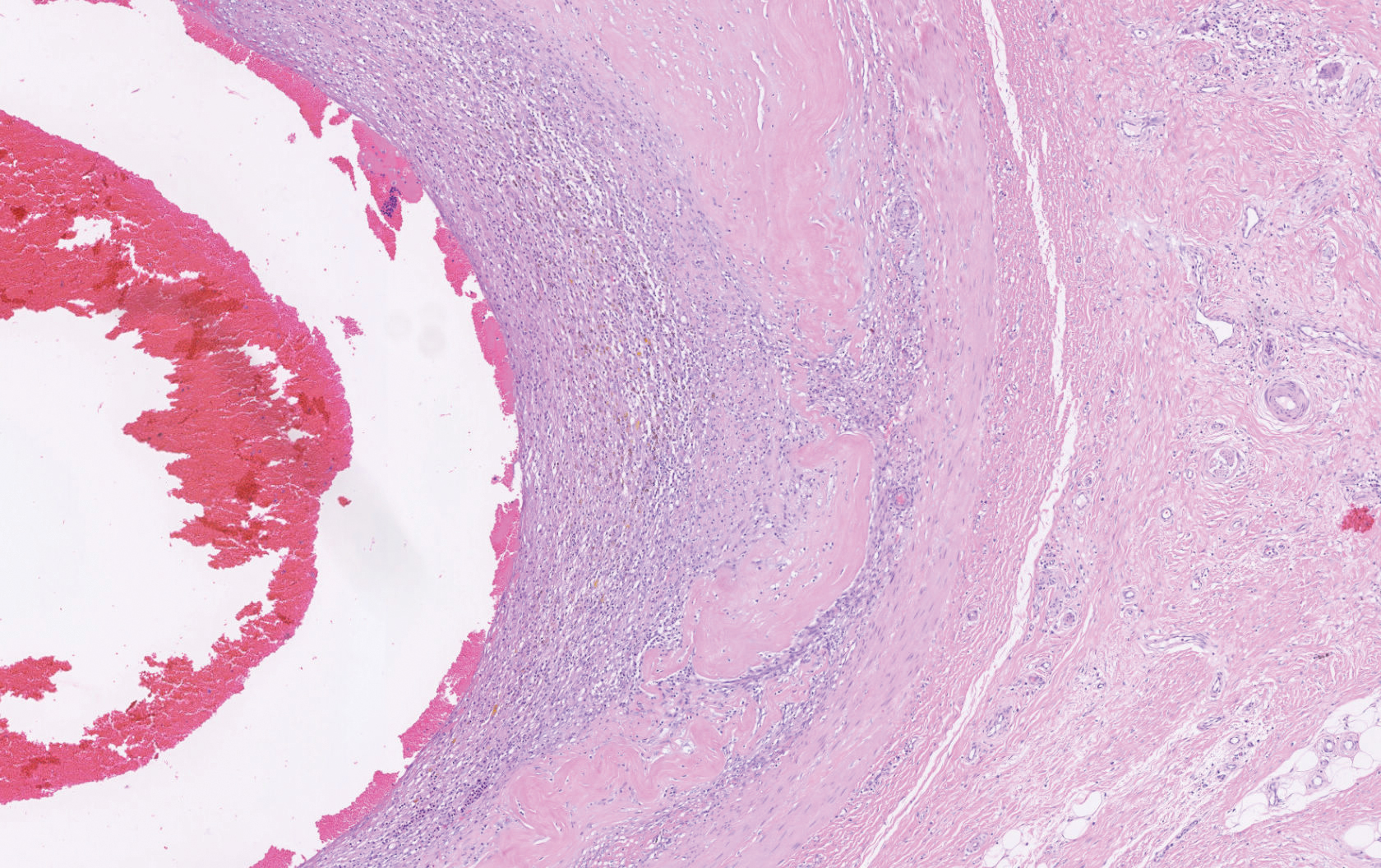

Biopsy revealed amorphous pink material within the center of palisading granulomas lined by histiocytes and giant cells. Scattered crystal remnants also were identified within the center of the granulomas; however, the majority of the crystals were dissolved during the formalin processing of the tissue to become the amorphous material. A perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded the tophi nodules. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of tophaceous gout (Figure).

Gout is a systemic metabolic disease characterized by the supersaturation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and bursae. Peripheral joints most commonly are affected due to the poor solubility of MSU crystals at low temperatures.1 It is one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis, with an estimated prevalence of 4% of adults in the United States.2 An estimated $1 billion is spent each year on ambulatory care for gout.3 Gout occurs most commonly in men and usually manifests in the fifth or sixth decades of life.4 Risk factors for the development of gout include obesity, hypertension, poor dietary habits and kidney function, excessive alcohol intake, and diuretic use.3

Disease manifestations range from asymptomatic hyperuricemia to acute gouty arthritis and chronic tophaceous gout. Patients may present with chronic tophaceous gout without a prior clinically apparent acute gout episode.5,6 Uncontrolled gout may result in large accumulations of MSU crystals, leading to well-circumscribed masses (known as tophi), as demonstrated in our patient.1 Tophi are pathognomonic features of gout and are the sine qua non of advanced gout (also known as chronic tophaceous gout).2 Clinically, these tophi appear as subcutaneous, yellowish white, firm and smooth nodules that are highlighted on the skin.4 Tophi most commonly are found on the helix, articular and periarticular tissue, and the tissue of the hands and feet. They usually are visible on physical examination but also may be detected on imaging studies.2,4

Gouty tophi have been reported in extraordinary locations, such as in sclerae; vocal cords; heart valves; abdominal striae; nerves; axial skeleton4,7; and the penis, as in our patient and one other case.2 These gouty deposits can appear similarly to lipomas, rheumatoid and osteoarthritic nodules, and infectious and malignant processes.1,5 When tophi present in unusual locations, tissue biopsy often is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Tissue preservation in alcohol is required to preserve the urate crystals. Microscopically, urate crystals appear as tightly packed, brown, needle-shaped crystals surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with foreign body giant cells, macrophages, and possibly some fibrosis. When examined under polarized light, the MSU crystals are negatively birefringent. However, when clinical suspicion for gout is low and the tissue is instead formalin fixed, as was performed in our case, the crystals dissolve into fibrillary amorphous deposits within the center of the granulomatous inflammation, which is another characteristic histologic finding in tophaceous gout.8

Management of gout focuses on urate-lowering therapy including lifestyle changes. Lower serum urate levels are associated with a decreased incidence of acute gout attacks and chronic tophaceous gout.2 Urate-lowering drugs often are combined with anti-inflammatory drugs during acute attacks. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, reduced alcohol consumption, high fluid intake, and a low-purine diet also are beneficial.3,4 Although gout cannot be cured, it can be effectively managed, and appropriate treatment can improve quality of life and reduce the risk for permanent joint damage and structural deformities. If medical treatment and lifestyle changes fail to adequately control tophaceous gout or if tophi become symptomatic, surgical removal of tophi is appropriate.4

At follow-up, our patient opted for surgical removal of the penile tophi. Using local anesthesia, surgical debulking via curettage was performed. Open defects were closed with fine absorbable sutures, and prophylactic antibiotics were given. Allopurinol also was started. Six weeks following extraction, the patient reported no complications and the area was continuing to heal.

Tophaceous gout would be distinguished from conditions in the differential diagnosis based on histologic findings from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Actinomycotic mycetoma is rare in the United States and is characterized by a seropurulent or stringy exudate with grains, ulcerations, melicerous scabs, and retractable scarring.9 On H&E-stained sections, actinomyces appear filamentous with deeply basophilic staining and radially oriented acidophilic projections.10 Calcinosis cutis of the penis has been reported to appear as asymptomatic papules; however, microscopic sections reveal deeply basophilic calcium deposits within the tissue.11 Multinodular syphilis shows characteristic histology with lichenoid or vacuolar interface dermatitis, slender acanthosis, plasma cells, and endothelial swelling of the small vessels. A Treponema pallidum immunoperoxidase stain shows numerous organisms. Planar xanthoma shows xanthomatous or foamy histiocytes throughout the dermis on H&E-stained sections.12

- Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: an old disease in new perspective--a review. J Adv Res. 2007;8:495-511.

- Flores Martín JF, Vázquez Alonso F, Puche Sanz I, et al. Gouty tophi in the penis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:594905.

- Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:58-68.

- Forbess LJ, Fields TR. The broad spectrum of urate crystal deposition: unusual presentations of gouty tophi. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:146-154.

- Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1431-1446.

- Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-1461.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Weedon D. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Guerra-Leal JD, Medrano-Danés LA, Montemayor-Martinez A, et al. The importance of diagnostic imaging of mycetoma in the foot [published online December 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:600-604.

- Fazeli MS, Bateni H. Actinomycosis: a rare soft tissue infection. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:18.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Idiopathic calcinosis cutis of the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:23-30.

- Ko C, Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

The Diagnosis: Tophaceous Gout

Biopsy revealed amorphous pink material within the center of palisading granulomas lined by histiocytes and giant cells. Scattered crystal remnants also were identified within the center of the granulomas; however, the majority of the crystals were dissolved during the formalin processing of the tissue to become the amorphous material. A perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded the tophi nodules. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of tophaceous gout (Figure).

Gout is a systemic metabolic disease characterized by the supersaturation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and bursae. Peripheral joints most commonly are affected due to the poor solubility of MSU crystals at low temperatures.1 It is one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis, with an estimated prevalence of 4% of adults in the United States.2 An estimated $1 billion is spent each year on ambulatory care for gout.3 Gout occurs most commonly in men and usually manifests in the fifth or sixth decades of life.4 Risk factors for the development of gout include obesity, hypertension, poor dietary habits and kidney function, excessive alcohol intake, and diuretic use.3

Disease manifestations range from asymptomatic hyperuricemia to acute gouty arthritis and chronic tophaceous gout. Patients may present with chronic tophaceous gout without a prior clinically apparent acute gout episode.5,6 Uncontrolled gout may result in large accumulations of MSU crystals, leading to well-circumscribed masses (known as tophi), as demonstrated in our patient.1 Tophi are pathognomonic features of gout and are the sine qua non of advanced gout (also known as chronic tophaceous gout).2 Clinically, these tophi appear as subcutaneous, yellowish white, firm and smooth nodules that are highlighted on the skin.4 Tophi most commonly are found on the helix, articular and periarticular tissue, and the tissue of the hands and feet. They usually are visible on physical examination but also may be detected on imaging studies.2,4

Gouty tophi have been reported in extraordinary locations, such as in sclerae; vocal cords; heart valves; abdominal striae; nerves; axial skeleton4,7; and the penis, as in our patient and one other case.2 These gouty deposits can appear similarly to lipomas, rheumatoid and osteoarthritic nodules, and infectious and malignant processes.1,5 When tophi present in unusual locations, tissue biopsy often is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Tissue preservation in alcohol is required to preserve the urate crystals. Microscopically, urate crystals appear as tightly packed, brown, needle-shaped crystals surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with foreign body giant cells, macrophages, and possibly some fibrosis. When examined under polarized light, the MSU crystals are negatively birefringent. However, when clinical suspicion for gout is low and the tissue is instead formalin fixed, as was performed in our case, the crystals dissolve into fibrillary amorphous deposits within the center of the granulomatous inflammation, which is another characteristic histologic finding in tophaceous gout.8

Management of gout focuses on urate-lowering therapy including lifestyle changes. Lower serum urate levels are associated with a decreased incidence of acute gout attacks and chronic tophaceous gout.2 Urate-lowering drugs often are combined with anti-inflammatory drugs during acute attacks. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, reduced alcohol consumption, high fluid intake, and a low-purine diet also are beneficial.3,4 Although gout cannot be cured, it can be effectively managed, and appropriate treatment can improve quality of life and reduce the risk for permanent joint damage and structural deformities. If medical treatment and lifestyle changes fail to adequately control tophaceous gout or if tophi become symptomatic, surgical removal of tophi is appropriate.4

At follow-up, our patient opted for surgical removal of the penile tophi. Using local anesthesia, surgical debulking via curettage was performed. Open defects were closed with fine absorbable sutures, and prophylactic antibiotics were given. Allopurinol also was started. Six weeks following extraction, the patient reported no complications and the area was continuing to heal.

Tophaceous gout would be distinguished from conditions in the differential diagnosis based on histologic findings from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Actinomycotic mycetoma is rare in the United States and is characterized by a seropurulent or stringy exudate with grains, ulcerations, melicerous scabs, and retractable scarring.9 On H&E-stained sections, actinomyces appear filamentous with deeply basophilic staining and radially oriented acidophilic projections.10 Calcinosis cutis of the penis has been reported to appear as asymptomatic papules; however, microscopic sections reveal deeply basophilic calcium deposits within the tissue.11 Multinodular syphilis shows characteristic histology with lichenoid or vacuolar interface dermatitis, slender acanthosis, plasma cells, and endothelial swelling of the small vessels. A Treponema pallidum immunoperoxidase stain shows numerous organisms. Planar xanthoma shows xanthomatous or foamy histiocytes throughout the dermis on H&E-stained sections.12

The Diagnosis: Tophaceous Gout

Biopsy revealed amorphous pink material within the center of palisading granulomas lined by histiocytes and giant cells. Scattered crystal remnants also were identified within the center of the granulomas; however, the majority of the crystals were dissolved during the formalin processing of the tissue to become the amorphous material. A perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded the tophi nodules. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of tophaceous gout (Figure).

Gout is a systemic metabolic disease characterized by the supersaturation of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and bursae. Peripheral joints most commonly are affected due to the poor solubility of MSU crystals at low temperatures.1 It is one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis, with an estimated prevalence of 4% of adults in the United States.2 An estimated $1 billion is spent each year on ambulatory care for gout.3 Gout occurs most commonly in men and usually manifests in the fifth or sixth decades of life.4 Risk factors for the development of gout include obesity, hypertension, poor dietary habits and kidney function, excessive alcohol intake, and diuretic use.3

Disease manifestations range from asymptomatic hyperuricemia to acute gouty arthritis and chronic tophaceous gout. Patients may present with chronic tophaceous gout without a prior clinically apparent acute gout episode.5,6 Uncontrolled gout may result in large accumulations of MSU crystals, leading to well-circumscribed masses (known as tophi), as demonstrated in our patient.1 Tophi are pathognomonic features of gout and are the sine qua non of advanced gout (also known as chronic tophaceous gout).2 Clinically, these tophi appear as subcutaneous, yellowish white, firm and smooth nodules that are highlighted on the skin.4 Tophi most commonly are found on the helix, articular and periarticular tissue, and the tissue of the hands and feet. They usually are visible on physical examination but also may be detected on imaging studies.2,4

Gouty tophi have been reported in extraordinary locations, such as in sclerae; vocal cords; heart valves; abdominal striae; nerves; axial skeleton4,7; and the penis, as in our patient and one other case.2 These gouty deposits can appear similarly to lipomas, rheumatoid and osteoarthritic nodules, and infectious and malignant processes.1,5 When tophi present in unusual locations, tissue biopsy often is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Tissue preservation in alcohol is required to preserve the urate crystals. Microscopically, urate crystals appear as tightly packed, brown, needle-shaped crystals surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with foreign body giant cells, macrophages, and possibly some fibrosis. When examined under polarized light, the MSU crystals are negatively birefringent. However, when clinical suspicion for gout is low and the tissue is instead formalin fixed, as was performed in our case, the crystals dissolve into fibrillary amorphous deposits within the center of the granulomatous inflammation, which is another characteristic histologic finding in tophaceous gout.8

Management of gout focuses on urate-lowering therapy including lifestyle changes. Lower serum urate levels are associated with a decreased incidence of acute gout attacks and chronic tophaceous gout.2 Urate-lowering drugs often are combined with anti-inflammatory drugs during acute attacks. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, exercise, reduced alcohol consumption, high fluid intake, and a low-purine diet also are beneficial.3,4 Although gout cannot be cured, it can be effectively managed, and appropriate treatment can improve quality of life and reduce the risk for permanent joint damage and structural deformities. If medical treatment and lifestyle changes fail to adequately control tophaceous gout or if tophi become symptomatic, surgical removal of tophi is appropriate.4

At follow-up, our patient opted for surgical removal of the penile tophi. Using local anesthesia, surgical debulking via curettage was performed. Open defects were closed with fine absorbable sutures, and prophylactic antibiotics were given. Allopurinol also was started. Six weeks following extraction, the patient reported no complications and the area was continuing to heal.

Tophaceous gout would be distinguished from conditions in the differential diagnosis based on histologic findings from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. Actinomycotic mycetoma is rare in the United States and is characterized by a seropurulent or stringy exudate with grains, ulcerations, melicerous scabs, and retractable scarring.9 On H&E-stained sections, actinomyces appear filamentous with deeply basophilic staining and radially oriented acidophilic projections.10 Calcinosis cutis of the penis has been reported to appear as asymptomatic papules; however, microscopic sections reveal deeply basophilic calcium deposits within the tissue.11 Multinodular syphilis shows characteristic histology with lichenoid or vacuolar interface dermatitis, slender acanthosis, plasma cells, and endothelial swelling of the small vessels. A Treponema pallidum immunoperoxidase stain shows numerous organisms. Planar xanthoma shows xanthomatous or foamy histiocytes throughout the dermis on H&E-stained sections.12

- Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: an old disease in new perspective--a review. J Adv Res. 2007;8:495-511.

- Flores Martín JF, Vázquez Alonso F, Puche Sanz I, et al. Gouty tophi in the penis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:594905.

- Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:58-68.

- Forbess LJ, Fields TR. The broad spectrum of urate crystal deposition: unusual presentations of gouty tophi. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:146-154.

- Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1431-1446.

- Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-1461.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Weedon D. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Guerra-Leal JD, Medrano-Danés LA, Montemayor-Martinez A, et al. The importance of diagnostic imaging of mycetoma in the foot [published online December 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:600-604.

- Fazeli MS, Bateni H. Actinomycosis: a rare soft tissue infection. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:18.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Idiopathic calcinosis cutis of the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:23-30.

- Ko C, Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

- Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: an old disease in new perspective--a review. J Adv Res. 2007;8:495-511.

- Flores Martín JF, Vázquez Alonso F, Puche Sanz I, et al. Gouty tophi in the penis: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:594905.

- Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:58-68.

- Forbess LJ, Fields TR. The broad spectrum of urate crystal deposition: unusual presentations of gouty tophi. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:146-154.

- Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1431-1446.

- Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1447-1461.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Weedon D. Weedon's Skin Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Guerra-Leal JD, Medrano-Danés LA, Montemayor-Martinez A, et al. The importance of diagnostic imaging of mycetoma in the foot [published online December 18, 2018]. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:600-604.

- Fazeli MS, Bateni H. Actinomycosis: a rare soft tissue infection. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:18.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Idiopathic calcinosis cutis of the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:23-30.

- Ko C, Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

A 34-year-old man presented for evaluation of a slowly growing group of firm white bumps on the penis. The lesions were nontender and asymptomatic. Medical and family history was notable for gout, though he was not being treated. Physical examination revealed a 3-cm, firm, multinodular, chalky white plaque on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft. A tangential biopsy was performed and sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Tense Bullae on the Hands

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

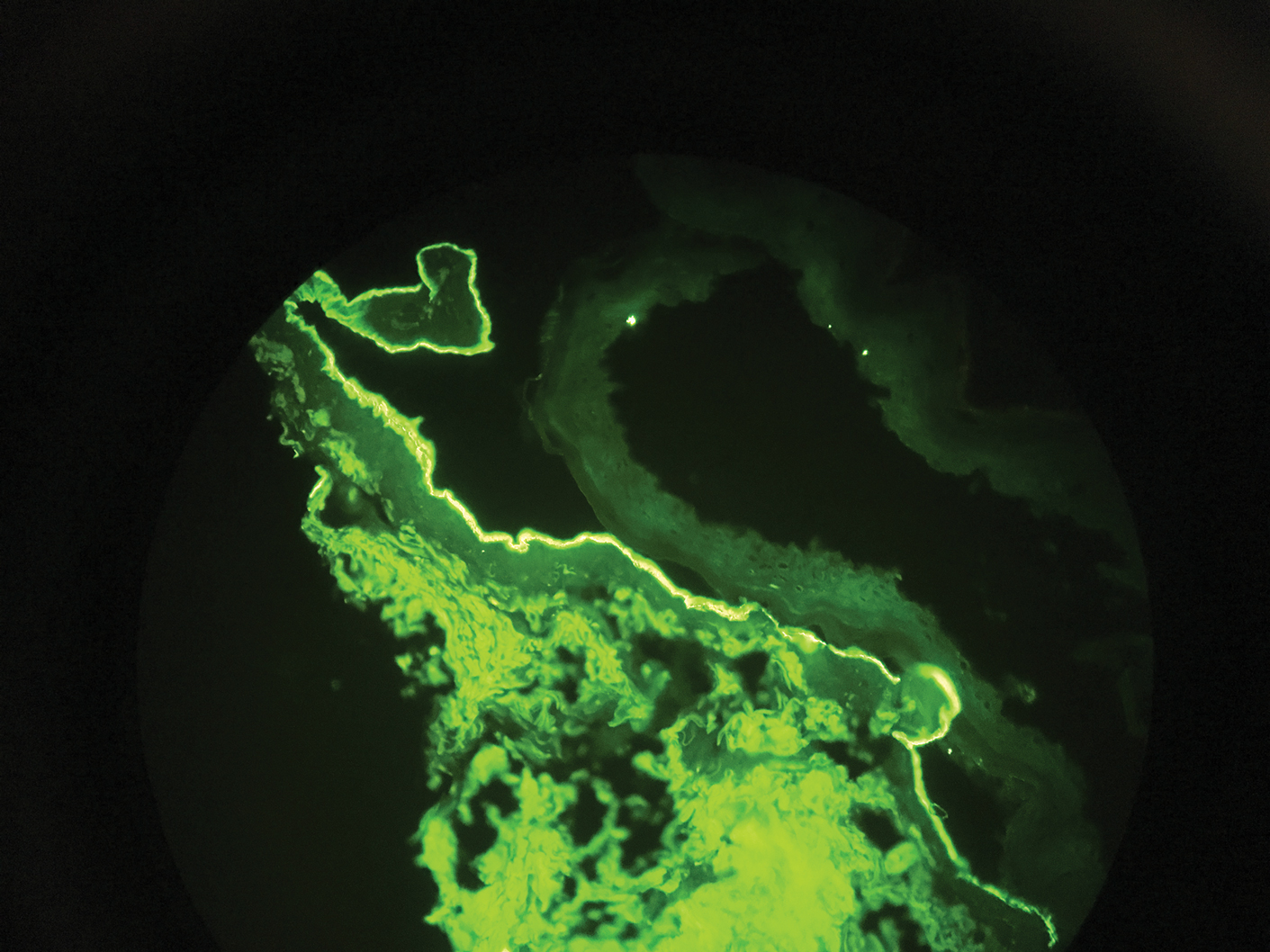

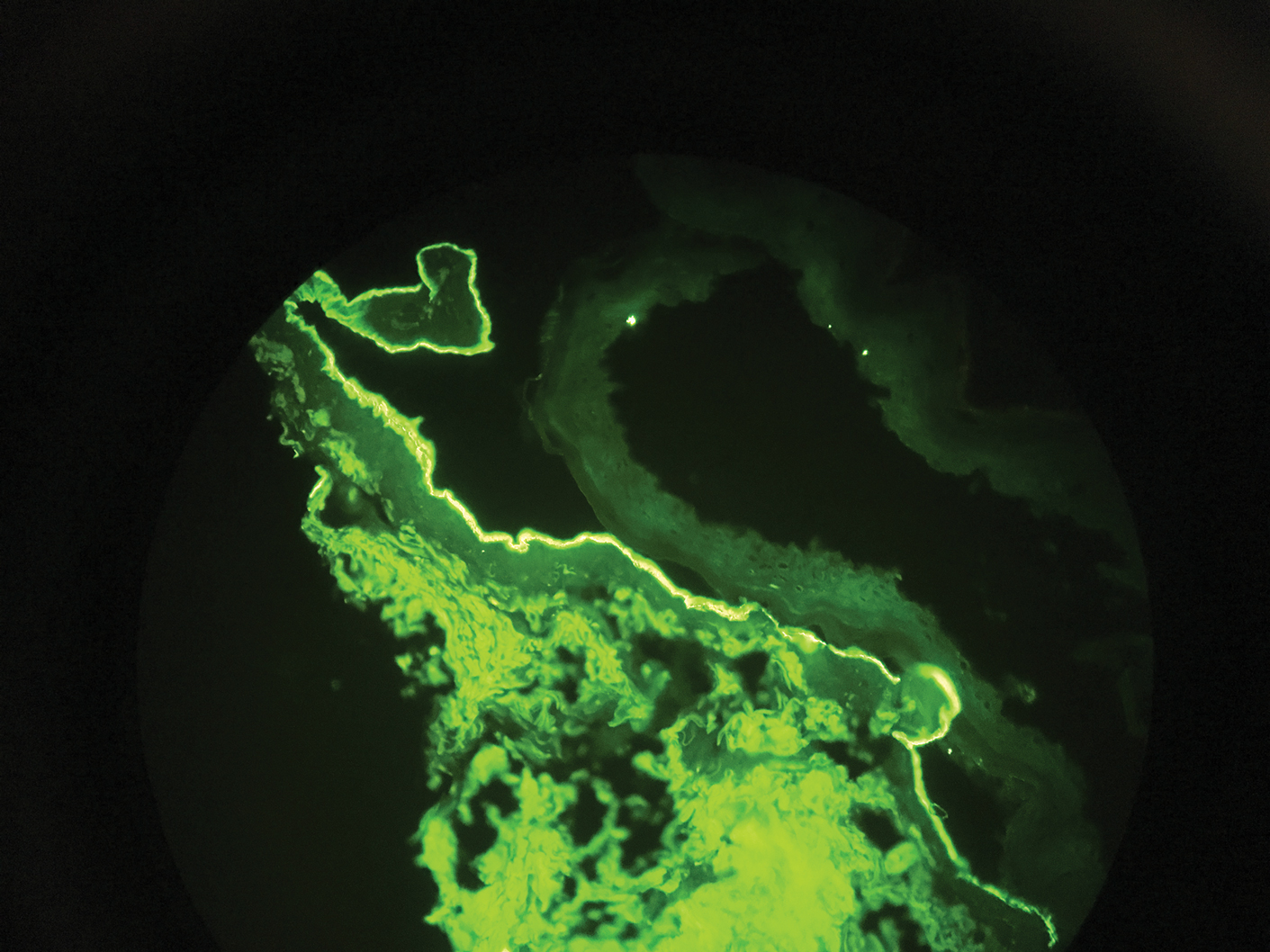

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

A 75-year-old man presented to our clinic with nonpainful, nonpruritic, tense bullae and erosions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and extensor surfaces of the elbows of 1 month's duration. The patient also had erythematous erosions and crusted papules on the left cheek and surrounding the left eye. He denied any new medications, history of liver or kidney disease, or history of hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus. There were no obvious exacerbating factors, including exposure to sunlight. Direct immunofluorescence using a salt-split preparation was performed on a biopsy of the perilesional skin.

Firm Abdominal Papule

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of primary gastric carcinoma is a rare occurrence, with the more common metastatic sites being the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneal cavity. The incidence of visceral neoplasm metastasis to the skin ranges from 0.7% to 9% and is less than 1% for upper digestive tract carcinomas.1 Cutaneous metastases make up 2% of all tumors of the skin and commonly are located near the site of the primary tumor.2 The most common cutaneous metastasis sites for gastric carcinoma include the neck, chest, and head.3 One of the more typical sites of cutaneous metastasis from gastric cancer is the umbilicus (ie, Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Cutaneous metastases from gastric carcinoma commonly present as asymptomatic hyperpigmented nodules.1,3

In our patient, histopathologic sections showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis by atypical polygonal/round cells arranged in cords and small aggregates. Some of the neoplastic cells had signet ring morphology (Figure). Tumor cells demonstrated positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen; they were negative for S-100, MART-1 (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells 1), leukocyte common antigen, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, estrogen and progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2).

Our patient's presentation was rare in that she developed an asymptomatic erythematous papule on the skin of the abdomen. However, her history of stage IIIB gastric adenocarcinoma in conjunction with the clinical picture and microscopic findings were most consistent with metastatic carcinoma of gastrointestinal origin. The histologic hallmarks of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma include aggregates of neoplastic cells arranged in cords, sometimes forming glands, embedded in a fibrous stroma. Tumor cells may demonstrate signet ring morphology. These unique histologic findings, as well as positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen, rule out other potential diagnoses for an asymptomatic solitary papule.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, indurated papule or plaque that develops into a red or brownish nodule. Histologically, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by spindled cells, few mitotic figures, infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomblike pattern, and obliteration of the adnexal structures.4

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) can present as single or multiple red papules or nodules located on the trunk, face, or extremities. Histologically, CBCL would show a nodular or diffuse infiltrate throughout the dermis, frequently with accentuation in the deep reticular dermis, sparing of the epidermis, and the presence of a grenz zone. The infiltrate in CBCL consists of CD20+, CD19+, and CD79a+ B cells. Identification of a monoclonal B-cell population either by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction would further support a diagnosis of CBCL.4 These specific histologic findings and the immunohistochemical staining pattern helped rule out CBCL as the diagnosis in our patient.