User login

Acute-Onset Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Thallium-Induced Alopecia

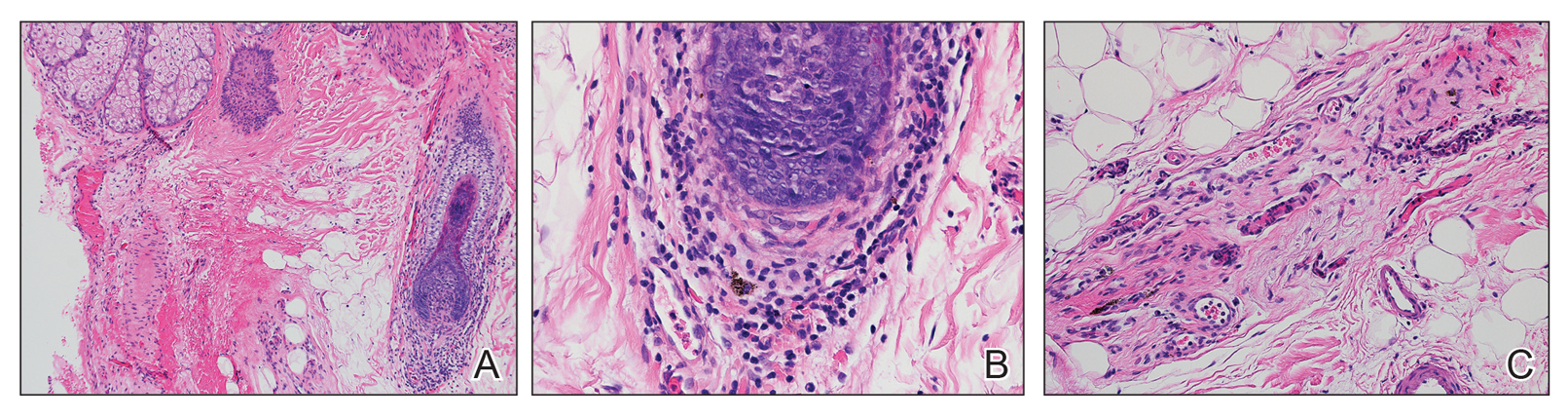

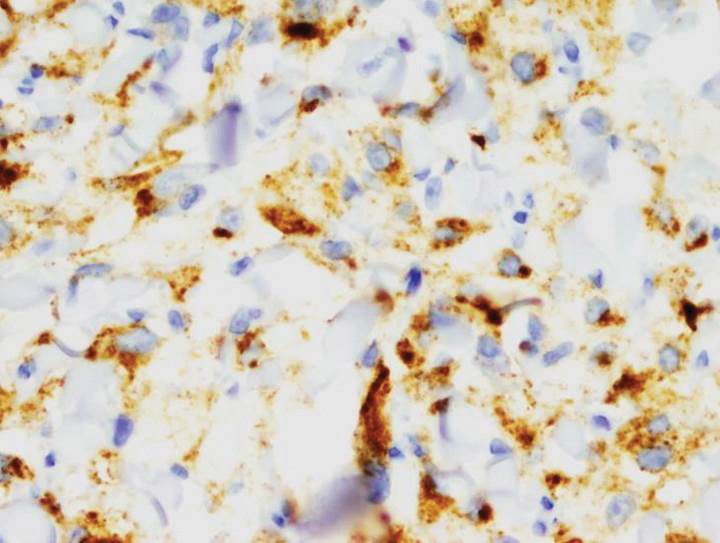

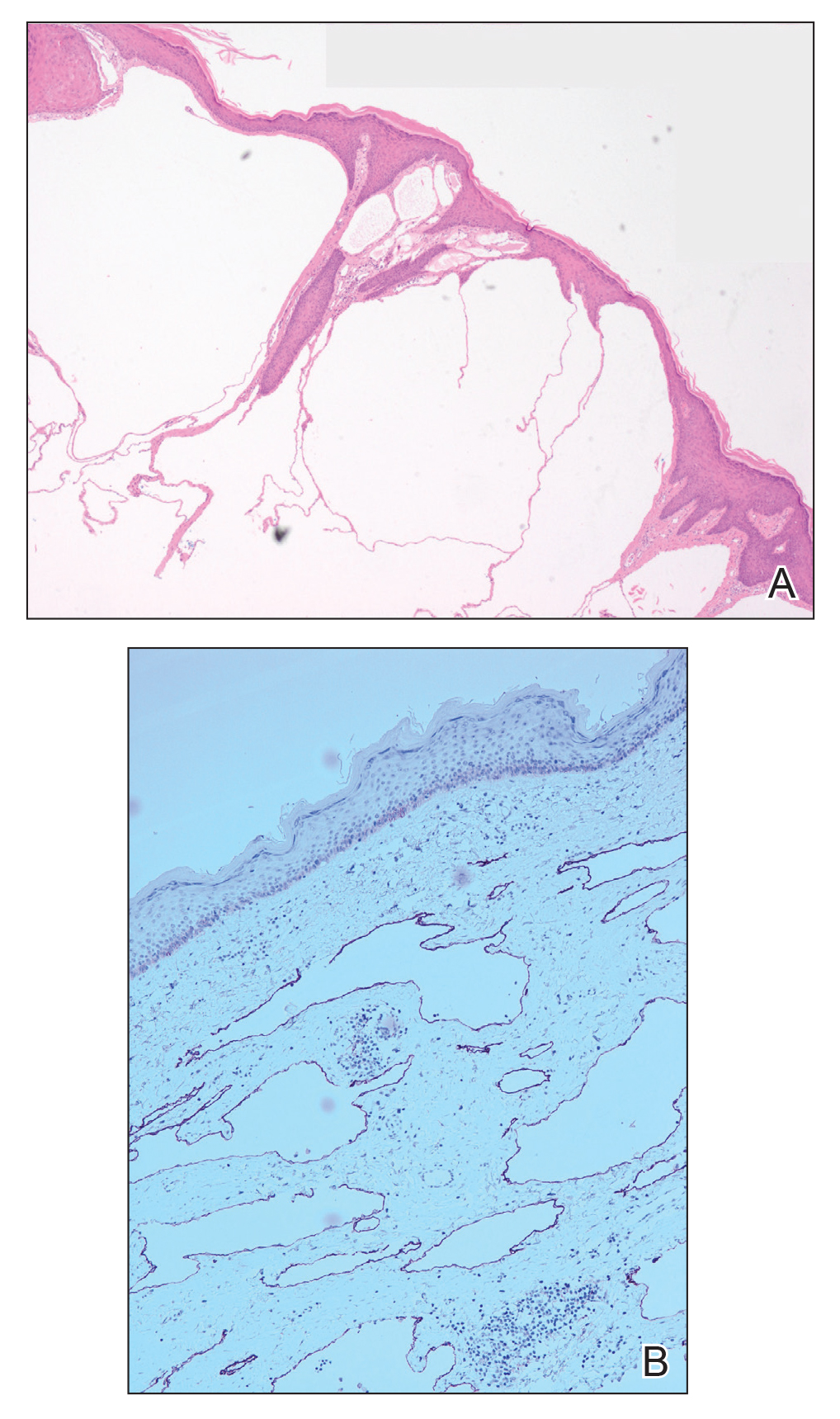

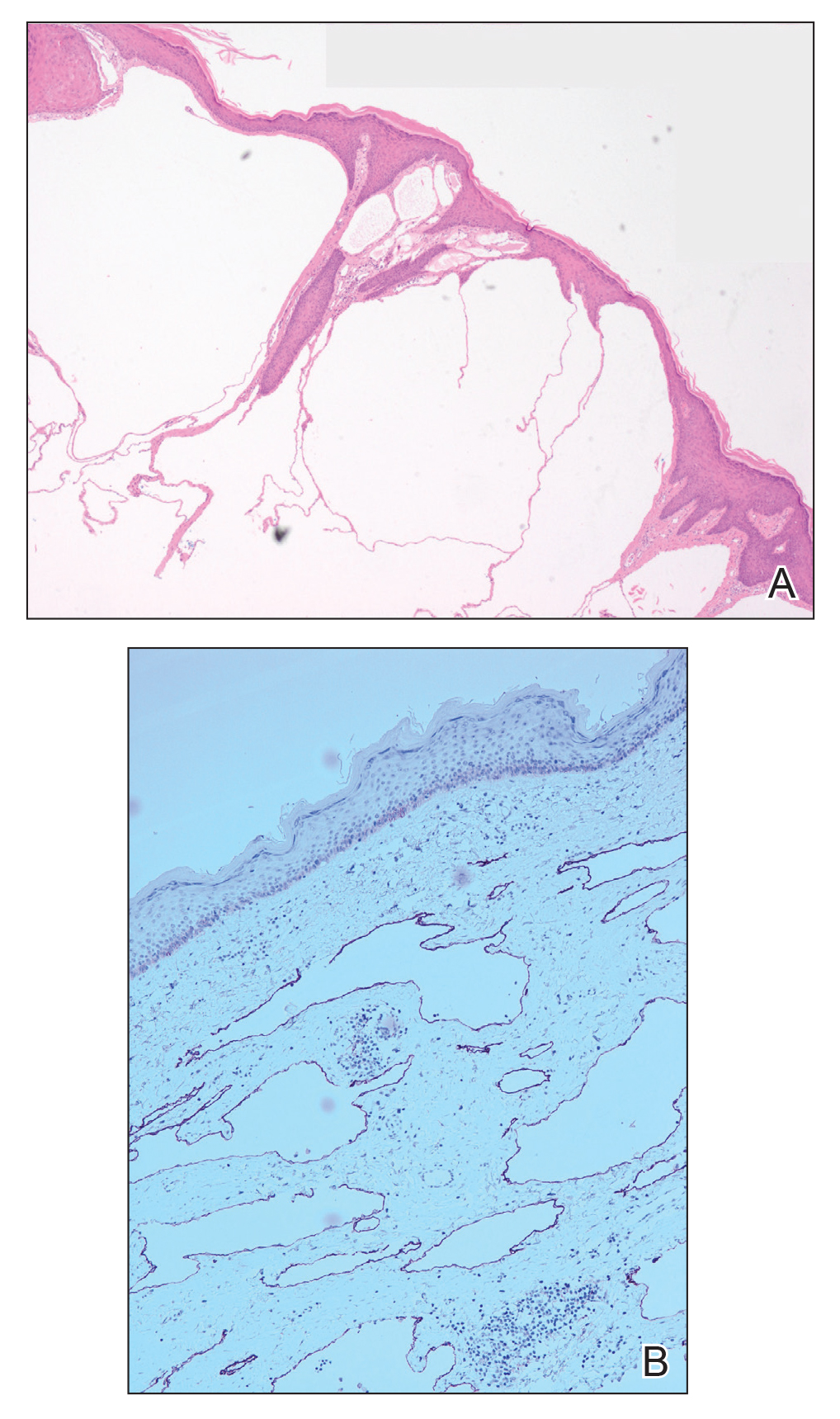

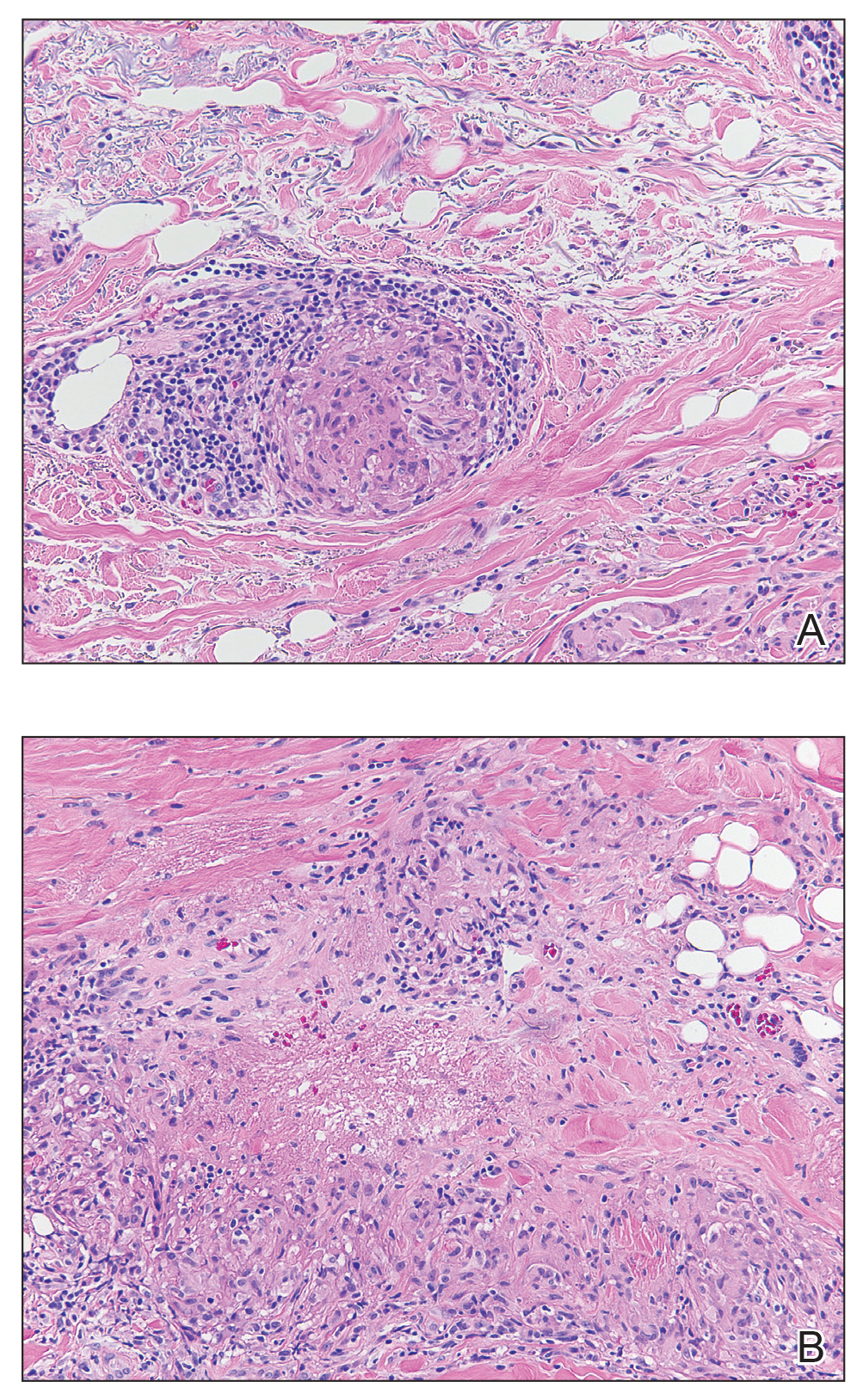

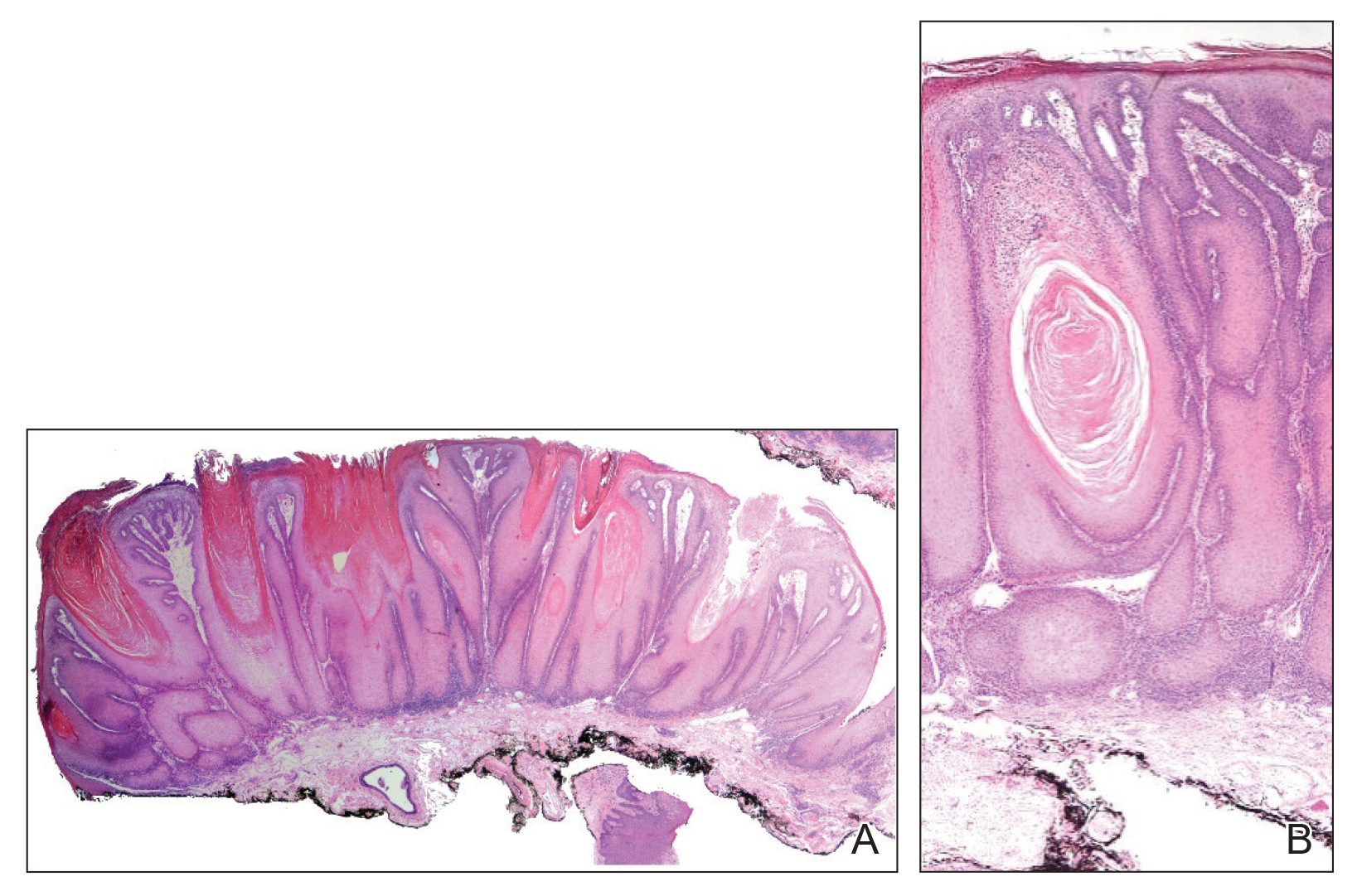

At the time of presentation, a punch biopsy specimen of the scalp revealed nonscarring alopecia with increased catagen hairs; follicular miniaturization; peribulbar lymphoid infiltrates; and fibrous tract remnants containing melanin, lymphocytes, and occasional mast cells (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included alopecia areata, syphilis, and toxin-mediated anagen effluvium (AE). Given the abrupt onset affecting multiple individuals in an industrial environment, heavy metal poisoning was suspected. Blood and urine testing was negative, but a few months had elapsed since exposure. Several months after his initial presentation, the patient reported problems with his teeth, thin brittle nails, and resolution of the visual changes. Photographs sent by the patient revealed darkening and degeneration of the gingival margin (Figure 2).

Environmental review revealed the patient was working on a demolition site of a 150-year-old electrical plant near a river. Inundation of rainfall caused a river swell and subsequent flooding of the work site. The patient reported working for more than 2 months in knee-deep muddy water, and he noted that water for consumption and showers was procured on-site from a well-based source that may have been contaminated by the floodwaters.

Acute nonscarring alopecia can be an AE or telogen effluvium (TE), also known as telogen defluvium. The key distinguishing factor is the mode of injury.1 In TE, medications, stress, hormonal shifts, or inflammation induce a synchronized and abrupt transition of hairs from anagen phase to catagen phase, a committed step that then must fully cycle through the telogen phase, culminating in the simultaneous shedding of numerous telogen hairs approximately 3 to 4 months later. Conversely, AE is caused by a sudden insult to the metabolic machinery of the hair matrix. Affected follicles rapidly produce thinner weaker shafts yielding Pohl-Pinkus constrictions or pencil point-shaped fractures that shed approximately 1 to 2 months after injury. The 10% of scalp hairs in the resting telogen phase have no matrix and thus are unaffected. Some etiologies can cause either AE or TE, depending on the dose and intensity of the insult. Common causes of AE include alopecia areata and syphilis, both consisting of abrupt severe bulbar inflammation.1 Other causes include chemotherapy, particularly antimetabolites, alkylating agents, and mitotic inhibitors; radiation; medications (eg, isoniazid); severe protein malnutrition; toxic chemicals (eg, boron/boric acid); and heavy metals (eg, thallium, mercury).

Thallium is one of the most common causes of heavy metal poisoning and is particularly dangerous due to its colorless, tasteless, and odorless characteristics. Although its common use as a rodenticide has dramatically decreased in the United States after it was banned in 1965, it is still used in this fashion in other countries and has a notable industrial presence, particularly in electronics, superconductors, and low-temperature thermometers. Accidental poisoning of a graduate chemistry student during copper research has been reported,2 highlighting that thallium can be inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. Thallium is even present in mycoplasma agar plates, the ingestion of which has resulted in poisoning.3

Systemic symptoms of thallium poisoning include somnolence, weakness, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, abdominal pain, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypertension, and polyneuropathy.4-7 Neuropathy often manifests as painful acral dysesthesia and paresthesia, perioral numbness, optic neuropathy causing visual changes, and encephalopathy. Cutaneous findings include diffuse alopecia of the scalp and eyebrows, perioral dermatitis, glossitis, diffuse hyperpigmentation, oral hyperpigmentation (often as a stippled lead line along the gingival margin with subsequent alveolar damage and resorption), melanonychia, palmoplantar keratoderma, acneform or pustular eruption, and nail changes including Mees lines.2,4,5,7-9 Rarely, major organ failure and death may result.10

Toxin panels may not include thallium, and urine and serum tests may be negative if too much time has transpired since the acute exposure. Hair or nail analysis has proved useful in subacute cases11; however, most laboratories require a pencil-thick segment of hair cut at the roots and bundled, weighing at least 500 mg. Thallium poisoning is treated with activated charcoal, Prussian blue, and blood purification therapies (eg, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, hemofiltration).4,7 Cutaneous findings typically resolve, but neuropathic changes may persist.

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE, Knopp EA. An Atlas of Hair Pathology With Clinical Correlations. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.

- Campbell C, Bahrami S, Owen C. Anagen effluvium caused by thallium poisoning. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:724-726.

- Puschner B, Basso MM. Graham TW. Thallium toxicosis in a dog consequent to ingestion of Mycoplasma agar plates. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:227-230.

- Sojáková M, Zigrai M, Karaman A, et al. Thallium intoxication: case report. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2015;36:311-315.

- Lu Cl, Huang CC, Chang YC, et al. Short-term thallium intoxication: dermatological findings correlated with thallium concentration. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:93-98.

- Liu EM, Rajagopal R, Grand MG. Optic nerve atrophy and hair loss in a young man. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:1469-1470.

- Zhang HT, Qiao BP, Liu BP, et al. Study on the treatment of acute thallium poisoning. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:377-381.

- Misra UK, Kalita J, Yadav RK, et al. Thallium poisoning: emphasis on early diagnosis and response to haemodialysis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:103-105.

- Tromme I, Van Neste D, Dobbelaere F, et al. Skin signs in the diagnosis of thallium poisoning. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:321-325.

- Li S, Huang W, Duan Y, et al. Human fatality due to thallium poisoning: autopsy, microscopy, and mass spectrometry assays. J Forensic Sci. 2015;60:247-251.

- Daniel CR 3rd, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. The nail and hair in forensic science. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:258-261.

The Diagnosis: Thallium-Induced Alopecia

At the time of presentation, a punch biopsy specimen of the scalp revealed nonscarring alopecia with increased catagen hairs; follicular miniaturization; peribulbar lymphoid infiltrates; and fibrous tract remnants containing melanin, lymphocytes, and occasional mast cells (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included alopecia areata, syphilis, and toxin-mediated anagen effluvium (AE). Given the abrupt onset affecting multiple individuals in an industrial environment, heavy metal poisoning was suspected. Blood and urine testing was negative, but a few months had elapsed since exposure. Several months after his initial presentation, the patient reported problems with his teeth, thin brittle nails, and resolution of the visual changes. Photographs sent by the patient revealed darkening and degeneration of the gingival margin (Figure 2).

Environmental review revealed the patient was working on a demolition site of a 150-year-old electrical plant near a river. Inundation of rainfall caused a river swell and subsequent flooding of the work site. The patient reported working for more than 2 months in knee-deep muddy water, and he noted that water for consumption and showers was procured on-site from a well-based source that may have been contaminated by the floodwaters.

Acute nonscarring alopecia can be an AE or telogen effluvium (TE), also known as telogen defluvium. The key distinguishing factor is the mode of injury.1 In TE, medications, stress, hormonal shifts, or inflammation induce a synchronized and abrupt transition of hairs from anagen phase to catagen phase, a committed step that then must fully cycle through the telogen phase, culminating in the simultaneous shedding of numerous telogen hairs approximately 3 to 4 months later. Conversely, AE is caused by a sudden insult to the metabolic machinery of the hair matrix. Affected follicles rapidly produce thinner weaker shafts yielding Pohl-Pinkus constrictions or pencil point-shaped fractures that shed approximately 1 to 2 months after injury. The 10% of scalp hairs in the resting telogen phase have no matrix and thus are unaffected. Some etiologies can cause either AE or TE, depending on the dose and intensity of the insult. Common causes of AE include alopecia areata and syphilis, both consisting of abrupt severe bulbar inflammation.1 Other causes include chemotherapy, particularly antimetabolites, alkylating agents, and mitotic inhibitors; radiation; medications (eg, isoniazid); severe protein malnutrition; toxic chemicals (eg, boron/boric acid); and heavy metals (eg, thallium, mercury).

Thallium is one of the most common causes of heavy metal poisoning and is particularly dangerous due to its colorless, tasteless, and odorless characteristics. Although its common use as a rodenticide has dramatically decreased in the United States after it was banned in 1965, it is still used in this fashion in other countries and has a notable industrial presence, particularly in electronics, superconductors, and low-temperature thermometers. Accidental poisoning of a graduate chemistry student during copper research has been reported,2 highlighting that thallium can be inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. Thallium is even present in mycoplasma agar plates, the ingestion of which has resulted in poisoning.3

Systemic symptoms of thallium poisoning include somnolence, weakness, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, abdominal pain, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypertension, and polyneuropathy.4-7 Neuropathy often manifests as painful acral dysesthesia and paresthesia, perioral numbness, optic neuropathy causing visual changes, and encephalopathy. Cutaneous findings include diffuse alopecia of the scalp and eyebrows, perioral dermatitis, glossitis, diffuse hyperpigmentation, oral hyperpigmentation (often as a stippled lead line along the gingival margin with subsequent alveolar damage and resorption), melanonychia, palmoplantar keratoderma, acneform or pustular eruption, and nail changes including Mees lines.2,4,5,7-9 Rarely, major organ failure and death may result.10

Toxin panels may not include thallium, and urine and serum tests may be negative if too much time has transpired since the acute exposure. Hair or nail analysis has proved useful in subacute cases11; however, most laboratories require a pencil-thick segment of hair cut at the roots and bundled, weighing at least 500 mg. Thallium poisoning is treated with activated charcoal, Prussian blue, and blood purification therapies (eg, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, hemofiltration).4,7 Cutaneous findings typically resolve, but neuropathic changes may persist.

The Diagnosis: Thallium-Induced Alopecia

At the time of presentation, a punch biopsy specimen of the scalp revealed nonscarring alopecia with increased catagen hairs; follicular miniaturization; peribulbar lymphoid infiltrates; and fibrous tract remnants containing melanin, lymphocytes, and occasional mast cells (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included alopecia areata, syphilis, and toxin-mediated anagen effluvium (AE). Given the abrupt onset affecting multiple individuals in an industrial environment, heavy metal poisoning was suspected. Blood and urine testing was negative, but a few months had elapsed since exposure. Several months after his initial presentation, the patient reported problems with his teeth, thin brittle nails, and resolution of the visual changes. Photographs sent by the patient revealed darkening and degeneration of the gingival margin (Figure 2).

Environmental review revealed the patient was working on a demolition site of a 150-year-old electrical plant near a river. Inundation of rainfall caused a river swell and subsequent flooding of the work site. The patient reported working for more than 2 months in knee-deep muddy water, and he noted that water for consumption and showers was procured on-site from a well-based source that may have been contaminated by the floodwaters.

Acute nonscarring alopecia can be an AE or telogen effluvium (TE), also known as telogen defluvium. The key distinguishing factor is the mode of injury.1 In TE, medications, stress, hormonal shifts, or inflammation induce a synchronized and abrupt transition of hairs from anagen phase to catagen phase, a committed step that then must fully cycle through the telogen phase, culminating in the simultaneous shedding of numerous telogen hairs approximately 3 to 4 months later. Conversely, AE is caused by a sudden insult to the metabolic machinery of the hair matrix. Affected follicles rapidly produce thinner weaker shafts yielding Pohl-Pinkus constrictions or pencil point-shaped fractures that shed approximately 1 to 2 months after injury. The 10% of scalp hairs in the resting telogen phase have no matrix and thus are unaffected. Some etiologies can cause either AE or TE, depending on the dose and intensity of the insult. Common causes of AE include alopecia areata and syphilis, both consisting of abrupt severe bulbar inflammation.1 Other causes include chemotherapy, particularly antimetabolites, alkylating agents, and mitotic inhibitors; radiation; medications (eg, isoniazid); severe protein malnutrition; toxic chemicals (eg, boron/boric acid); and heavy metals (eg, thallium, mercury).

Thallium is one of the most common causes of heavy metal poisoning and is particularly dangerous due to its colorless, tasteless, and odorless characteristics. Although its common use as a rodenticide has dramatically decreased in the United States after it was banned in 1965, it is still used in this fashion in other countries and has a notable industrial presence, particularly in electronics, superconductors, and low-temperature thermometers. Accidental poisoning of a graduate chemistry student during copper research has been reported,2 highlighting that thallium can be inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. Thallium is even present in mycoplasma agar plates, the ingestion of which has resulted in poisoning.3

Systemic symptoms of thallium poisoning include somnolence, weakness, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, abdominal pain, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypertension, and polyneuropathy.4-7 Neuropathy often manifests as painful acral dysesthesia and paresthesia, perioral numbness, optic neuropathy causing visual changes, and encephalopathy. Cutaneous findings include diffuse alopecia of the scalp and eyebrows, perioral dermatitis, glossitis, diffuse hyperpigmentation, oral hyperpigmentation (often as a stippled lead line along the gingival margin with subsequent alveolar damage and resorption), melanonychia, palmoplantar keratoderma, acneform or pustular eruption, and nail changes including Mees lines.2,4,5,7-9 Rarely, major organ failure and death may result.10

Toxin panels may not include thallium, and urine and serum tests may be negative if too much time has transpired since the acute exposure. Hair or nail analysis has proved useful in subacute cases11; however, most laboratories require a pencil-thick segment of hair cut at the roots and bundled, weighing at least 500 mg. Thallium poisoning is treated with activated charcoal, Prussian blue, and blood purification therapies (eg, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, hemofiltration).4,7 Cutaneous findings typically resolve, but neuropathic changes may persist.

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE, Knopp EA. An Atlas of Hair Pathology With Clinical Correlations. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.

- Campbell C, Bahrami S, Owen C. Anagen effluvium caused by thallium poisoning. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:724-726.

- Puschner B, Basso MM. Graham TW. Thallium toxicosis in a dog consequent to ingestion of Mycoplasma agar plates. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:227-230.

- Sojáková M, Zigrai M, Karaman A, et al. Thallium intoxication: case report. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2015;36:311-315.

- Lu Cl, Huang CC, Chang YC, et al. Short-term thallium intoxication: dermatological findings correlated with thallium concentration. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:93-98.

- Liu EM, Rajagopal R, Grand MG. Optic nerve atrophy and hair loss in a young man. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:1469-1470.

- Zhang HT, Qiao BP, Liu BP, et al. Study on the treatment of acute thallium poisoning. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:377-381.

- Misra UK, Kalita J, Yadav RK, et al. Thallium poisoning: emphasis on early diagnosis and response to haemodialysis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:103-105.

- Tromme I, Van Neste D, Dobbelaere F, et al. Skin signs in the diagnosis of thallium poisoning. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:321-325.

- Li S, Huang W, Duan Y, et al. Human fatality due to thallium poisoning: autopsy, microscopy, and mass spectrometry assays. J Forensic Sci. 2015;60:247-251.

- Daniel CR 3rd, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. The nail and hair in forensic science. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:258-261.

- Sperling LC, Cowper SE, Knopp EA. An Atlas of Hair Pathology With Clinical Correlations. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.

- Campbell C, Bahrami S, Owen C. Anagen effluvium caused by thallium poisoning. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:724-726.

- Puschner B, Basso MM. Graham TW. Thallium toxicosis in a dog consequent to ingestion of Mycoplasma agar plates. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:227-230.

- Sojáková M, Zigrai M, Karaman A, et al. Thallium intoxication: case report. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2015;36:311-315.

- Lu Cl, Huang CC, Chang YC, et al. Short-term thallium intoxication: dermatological findings correlated with thallium concentration. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:93-98.

- Liu EM, Rajagopal R, Grand MG. Optic nerve atrophy and hair loss in a young man. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:1469-1470.

- Zhang HT, Qiao BP, Liu BP, et al. Study on the treatment of acute thallium poisoning. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:377-381.

- Misra UK, Kalita J, Yadav RK, et al. Thallium poisoning: emphasis on early diagnosis and response to haemodialysis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:103-105.

- Tromme I, Van Neste D, Dobbelaere F, et al. Skin signs in the diagnosis of thallium poisoning. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:321-325.

- Li S, Huang W, Duan Y, et al. Human fatality due to thallium poisoning: autopsy, microscopy, and mass spectrometry assays. J Forensic Sci. 2015;60:247-251.

- Daniel CR 3rd, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. The nail and hair in forensic science. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:258-261.

A previously healthy 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with abrupt onset of patchy, progressively worsening alopecia of the scalp as well as nausea with emesis and blurry vision of a few weeks' duration. All symptoms were temporally associated with a new demolition job the patient had started at an industrial site. He reported 10 other contractors were similarly affected. The patient denied paresthesia or other skin changes. On physical examination, large patches of smooth alopecia without erythema, scale, scarring, tenderness, or edema that coalesced to involve the majority of the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes (inset) were noted.

Acquired Hypertrichosis of the Periorbital Area and Malar Cheek

The Diagnosis: Bimatoprost-Induced Hypertrichosis

Latanoprost, a prostaglandin analogue, typically is prescribed by ophthalmologists as eye drops to reduce intraocular pressure in open-angle glaucoma.1 Common adverse reactions of latanoprost drops include blurred vision, ocular irritation, darkening of the eyelid skin, and pigmentation of the iris.

In 1997, Johnstone2 reported hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of the eyelashes of both eyes and adjacent skin after latanoprost drops were used in glaucoma patients. Subsequently, topical latanoprost and bimatoprost, a similar analogue, are now utilized for the cosmetic purpose of thickening and lengthening the eyelashes due to the hypertrichosis effect. Travoprost, another prostaglandin analogue used to treat glaucoma, also has been associated with periocular hypertrichosis.3 Concomitant poliosis of the eyelashes with hypertrichosis from latanoprost also has been reported.4 Our patient specifically purchased the eye drops (marketed as generic bimatoprost) to lengthen her eyelashes and had noticed an increase in length. She denied a family history of increased facial hair in females.

Along with gingival hyperplasia, systemic cyclosporine may cause generalized hypertrichosis consisting of terminal hair growth, particularly on the face and forearms. However, hypertrichosis from cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% rarely has been reported5 but would be more likely to occur in a patient reporting a history of chronic dry eye. Oral acetazolamide, not eye drops, is prescribed for glaucoma and typically is not associated with hypertrichosis. Betamethasone and timolol eye drops may cause burning, stinging, redness, or watering of the eyes, but they do not typically cause hypertrichosis.

Other systemic medications (eg, zidovudine, phenytoin, minoxidil, danazol, anabolic steroids) may cause hypertrichosis but not typically localized to the periocular area. Phenytoin usually causes hair growth on the limbs but not on the face and trunk. Oral minoxidil causes hypertrichosis, predominately on the face, lower legs, and forearms.

Systemic conditions such as endocrine abnormalities or porphyria cutanea tarda also may cause hypertrichosis; however, it typically does not present in small focal areas, and other stigmata often are present such as signs of virilization in hirsutism (ie, deepening of voice, pattern alopecia, acne) or liver disease with photosensitive erosions and bullae that leave scars and milia in porphyria cutanea tarda. Acquired hypertrichosis lanuginosa deserves consideration, in part due to its association with lung and colon cancers; however, it consists of softer, downy, nonterminal hairs (malignant down) and is more generalized on the face. Malnutrition from anorexia nervosa may similarly induce hypertrichosis lanuginose.

The molecular mechanism for latanoprost-induced hypertrichosis is unknown; however, it may promote anagen growth as well as hypertrophic changes in the affected follicles.6 Patients should use extreme caution when purchasing unregulated medications due to the risk for impurities, less stable formulation, or inaccurate concentrations. Comparison between brand name and approved generic latanoprost has found notable differences, including variations in active-ingredient concentration, poor stability in warmer temperatures, and higher levels of particulate matter.7 Some cosmetic eyelash enhancers sold over-the-counter or online may contain prostaglandin analogues, but they may not be listed as ingredients.8 One report noted a bimatoprost product with a concentration level double that of brand-name bimatoprost that was discovered using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.9

Treatment options for eliminating the excess hairs include discontinuing the prostaglandin analogue or applying it only to the eyelid margin with an appropriate applicator. Waxing, manual extraction, laser hair removal, electrolysis, and depilatory creams are alternative treatments.

- Alm A. Latanoprost in the treatment of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1967-1985.

- Johnstone MA. Hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of eyelashes and adjacent hair in the region of the ipsilateral eyelids of patients treated with unilateral topical latanoprost. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:544-547.

- Ortiz-Perez S, Olver JM. Hypertrichosis of the upper cheek area associated with travoprost treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:376-377.

- Özyurt S, Çetinkaya GS. Hypertrichosis of the malar areas and poliosis of the eyelashes caused by latanoprost. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:74-75.

- Lei HL, Ku WC, Sun MH, et al. Cyclosporine A eye drop-induced elongated eyelashes: a case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2:398-400.

- Johnstone MA, Albert DM. Prostaglandin-induced hair growth. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):S185-S202.

- Kahook MY, Fechtner RD, Katz LJ, et al. A comparison of active ingredients and preservatives between brand name and generic topical glaucoma medications using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:101-108.

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Pharmaceutical ingredients in one out of three eyelash serums. https://www.dr-jetskeultee.nl/jetskeultee/download/common/artikel-wimpers-ingredients.pdf. Published April 15, 2013. Accessed April 11, 2019.

- Marchei E, De Orsi D, Guarino C, et al. High performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry measurement of bimatoprost, latanoprost and travoprost in eyelash enhancing cosmetic serums. Cosmetics. 2016;3:4.

The Diagnosis: Bimatoprost-Induced Hypertrichosis

Latanoprost, a prostaglandin analogue, typically is prescribed by ophthalmologists as eye drops to reduce intraocular pressure in open-angle glaucoma.1 Common adverse reactions of latanoprost drops include blurred vision, ocular irritation, darkening of the eyelid skin, and pigmentation of the iris.

In 1997, Johnstone2 reported hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of the eyelashes of both eyes and adjacent skin after latanoprost drops were used in glaucoma patients. Subsequently, topical latanoprost and bimatoprost, a similar analogue, are now utilized for the cosmetic purpose of thickening and lengthening the eyelashes due to the hypertrichosis effect. Travoprost, another prostaglandin analogue used to treat glaucoma, also has been associated with periocular hypertrichosis.3 Concomitant poliosis of the eyelashes with hypertrichosis from latanoprost also has been reported.4 Our patient specifically purchased the eye drops (marketed as generic bimatoprost) to lengthen her eyelashes and had noticed an increase in length. She denied a family history of increased facial hair in females.

Along with gingival hyperplasia, systemic cyclosporine may cause generalized hypertrichosis consisting of terminal hair growth, particularly on the face and forearms. However, hypertrichosis from cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% rarely has been reported5 but would be more likely to occur in a patient reporting a history of chronic dry eye. Oral acetazolamide, not eye drops, is prescribed for glaucoma and typically is not associated with hypertrichosis. Betamethasone and timolol eye drops may cause burning, stinging, redness, or watering of the eyes, but they do not typically cause hypertrichosis.

Other systemic medications (eg, zidovudine, phenytoin, minoxidil, danazol, anabolic steroids) may cause hypertrichosis but not typically localized to the periocular area. Phenytoin usually causes hair growth on the limbs but not on the face and trunk. Oral minoxidil causes hypertrichosis, predominately on the face, lower legs, and forearms.

Systemic conditions such as endocrine abnormalities or porphyria cutanea tarda also may cause hypertrichosis; however, it typically does not present in small focal areas, and other stigmata often are present such as signs of virilization in hirsutism (ie, deepening of voice, pattern alopecia, acne) or liver disease with photosensitive erosions and bullae that leave scars and milia in porphyria cutanea tarda. Acquired hypertrichosis lanuginosa deserves consideration, in part due to its association with lung and colon cancers; however, it consists of softer, downy, nonterminal hairs (malignant down) and is more generalized on the face. Malnutrition from anorexia nervosa may similarly induce hypertrichosis lanuginose.

The molecular mechanism for latanoprost-induced hypertrichosis is unknown; however, it may promote anagen growth as well as hypertrophic changes in the affected follicles.6 Patients should use extreme caution when purchasing unregulated medications due to the risk for impurities, less stable formulation, or inaccurate concentrations. Comparison between brand name and approved generic latanoprost has found notable differences, including variations in active-ingredient concentration, poor stability in warmer temperatures, and higher levels of particulate matter.7 Some cosmetic eyelash enhancers sold over-the-counter or online may contain prostaglandin analogues, but they may not be listed as ingredients.8 One report noted a bimatoprost product with a concentration level double that of brand-name bimatoprost that was discovered using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.9

Treatment options for eliminating the excess hairs include discontinuing the prostaglandin analogue or applying it only to the eyelid margin with an appropriate applicator. Waxing, manual extraction, laser hair removal, electrolysis, and depilatory creams are alternative treatments.

The Diagnosis: Bimatoprost-Induced Hypertrichosis

Latanoprost, a prostaglandin analogue, typically is prescribed by ophthalmologists as eye drops to reduce intraocular pressure in open-angle glaucoma.1 Common adverse reactions of latanoprost drops include blurred vision, ocular irritation, darkening of the eyelid skin, and pigmentation of the iris.

In 1997, Johnstone2 reported hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of the eyelashes of both eyes and adjacent skin after latanoprost drops were used in glaucoma patients. Subsequently, topical latanoprost and bimatoprost, a similar analogue, are now utilized for the cosmetic purpose of thickening and lengthening the eyelashes due to the hypertrichosis effect. Travoprost, another prostaglandin analogue used to treat glaucoma, also has been associated with periocular hypertrichosis.3 Concomitant poliosis of the eyelashes with hypertrichosis from latanoprost also has been reported.4 Our patient specifically purchased the eye drops (marketed as generic bimatoprost) to lengthen her eyelashes and had noticed an increase in length. She denied a family history of increased facial hair in females.

Along with gingival hyperplasia, systemic cyclosporine may cause generalized hypertrichosis consisting of terminal hair growth, particularly on the face and forearms. However, hypertrichosis from cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% rarely has been reported5 but would be more likely to occur in a patient reporting a history of chronic dry eye. Oral acetazolamide, not eye drops, is prescribed for glaucoma and typically is not associated with hypertrichosis. Betamethasone and timolol eye drops may cause burning, stinging, redness, or watering of the eyes, but they do not typically cause hypertrichosis.

Other systemic medications (eg, zidovudine, phenytoin, minoxidil, danazol, anabolic steroids) may cause hypertrichosis but not typically localized to the periocular area. Phenytoin usually causes hair growth on the limbs but not on the face and trunk. Oral minoxidil causes hypertrichosis, predominately on the face, lower legs, and forearms.

Systemic conditions such as endocrine abnormalities or porphyria cutanea tarda also may cause hypertrichosis; however, it typically does not present in small focal areas, and other stigmata often are present such as signs of virilization in hirsutism (ie, deepening of voice, pattern alopecia, acne) or liver disease with photosensitive erosions and bullae that leave scars and milia in porphyria cutanea tarda. Acquired hypertrichosis lanuginosa deserves consideration, in part due to its association with lung and colon cancers; however, it consists of softer, downy, nonterminal hairs (malignant down) and is more generalized on the face. Malnutrition from anorexia nervosa may similarly induce hypertrichosis lanuginose.

The molecular mechanism for latanoprost-induced hypertrichosis is unknown; however, it may promote anagen growth as well as hypertrophic changes in the affected follicles.6 Patients should use extreme caution when purchasing unregulated medications due to the risk for impurities, less stable formulation, or inaccurate concentrations. Comparison between brand name and approved generic latanoprost has found notable differences, including variations in active-ingredient concentration, poor stability in warmer temperatures, and higher levels of particulate matter.7 Some cosmetic eyelash enhancers sold over-the-counter or online may contain prostaglandin analogues, but they may not be listed as ingredients.8 One report noted a bimatoprost product with a concentration level double that of brand-name bimatoprost that was discovered using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.9

Treatment options for eliminating the excess hairs include discontinuing the prostaglandin analogue or applying it only to the eyelid margin with an appropriate applicator. Waxing, manual extraction, laser hair removal, electrolysis, and depilatory creams are alternative treatments.

- Alm A. Latanoprost in the treatment of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1967-1985.

- Johnstone MA. Hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of eyelashes and adjacent hair in the region of the ipsilateral eyelids of patients treated with unilateral topical latanoprost. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:544-547.

- Ortiz-Perez S, Olver JM. Hypertrichosis of the upper cheek area associated with travoprost treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:376-377.

- Özyurt S, Çetinkaya GS. Hypertrichosis of the malar areas and poliosis of the eyelashes caused by latanoprost. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:74-75.

- Lei HL, Ku WC, Sun MH, et al. Cyclosporine A eye drop-induced elongated eyelashes: a case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2:398-400.

- Johnstone MA, Albert DM. Prostaglandin-induced hair growth. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):S185-S202.

- Kahook MY, Fechtner RD, Katz LJ, et al. A comparison of active ingredients and preservatives between brand name and generic topical glaucoma medications using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:101-108.

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Pharmaceutical ingredients in one out of three eyelash serums. https://www.dr-jetskeultee.nl/jetskeultee/download/common/artikel-wimpers-ingredients.pdf. Published April 15, 2013. Accessed April 11, 2019.

- Marchei E, De Orsi D, Guarino C, et al. High performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry measurement of bimatoprost, latanoprost and travoprost in eyelash enhancing cosmetic serums. Cosmetics. 2016;3:4.

- Alm A. Latanoprost in the treatment of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1967-1985.

- Johnstone MA. Hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of eyelashes and adjacent hair in the region of the ipsilateral eyelids of patients treated with unilateral topical latanoprost. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:544-547.

- Ortiz-Perez S, Olver JM. Hypertrichosis of the upper cheek area associated with travoprost treatment of glaucoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:376-377.

- Özyurt S, Çetinkaya GS. Hypertrichosis of the malar areas and poliosis of the eyelashes caused by latanoprost. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:74-75.

- Lei HL, Ku WC, Sun MH, et al. Cyclosporine A eye drop-induced elongated eyelashes: a case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2:398-400.

- Johnstone MA, Albert DM. Prostaglandin-induced hair growth. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):S185-S202.

- Kahook MY, Fechtner RD, Katz LJ, et al. A comparison of active ingredients and preservatives between brand name and generic topical glaucoma medications using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:101-108.

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Pharmaceutical ingredients in one out of three eyelash serums. https://www.dr-jetskeultee.nl/jetskeultee/download/common/artikel-wimpers-ingredients.pdf. Published April 15, 2013. Accessed April 11, 2019.

- Marchei E, De Orsi D, Guarino C, et al. High performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry measurement of bimatoprost, latanoprost and travoprost in eyelash enhancing cosmetic serums. Cosmetics. 2016;3:4.

An otherwise healthy woman in her late 50s with Fitzpatrick skin type II presented to the dermatology department for a scheduled cosmetic botulinum toxin injection. Her medical history was notable only for periodic nonsurgical cosmetic procedures including botulinum toxin and dermal fillers, and she was not taking any daily systemic medications. During the preoperative assessment, subtle bilateral and symmetric hypertrichosis with darker terminal hair formation was noted on the periorbital skin and zygomatic cheek. Upon inquiry, the patient admitted to purchasing a “special eye drop” from Mexico and using it regularly. After instillation of 2 to 3 drops per eye, she would laterally wipe the resulting excess drops away from the eyes with her hands and then wash her hands. She denied a change in eye color from their natural brown but did report using blue color contact lenses. She denied an increase in hair growth elsewhere including the upper lip, chin, upper chest, forearms, and hands. She denied deepening of her voice, acne, or hair thinning.

Acral Flesh-Colored Papules on the Fingers

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

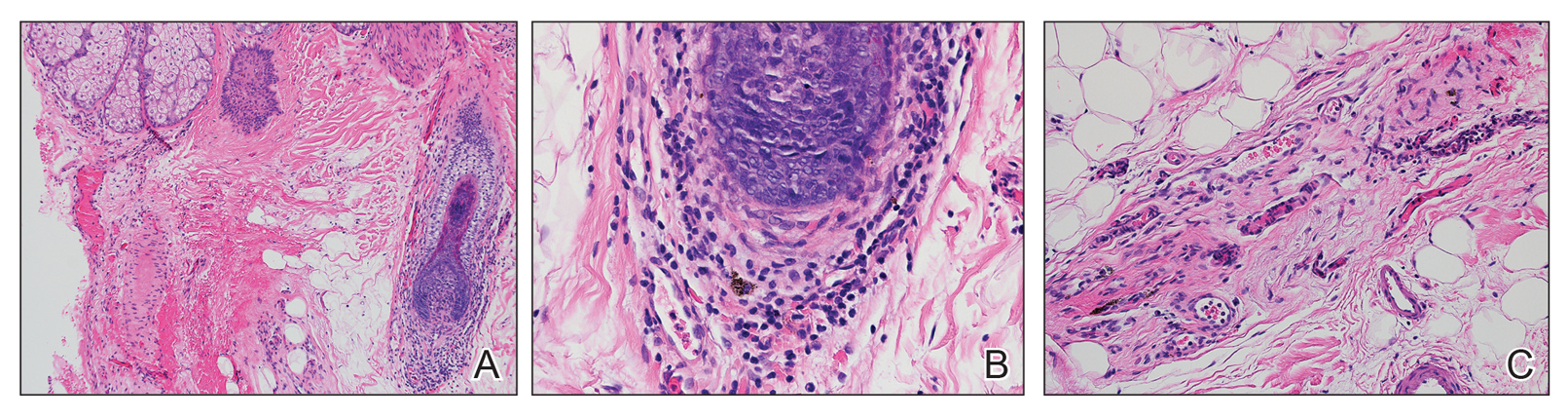

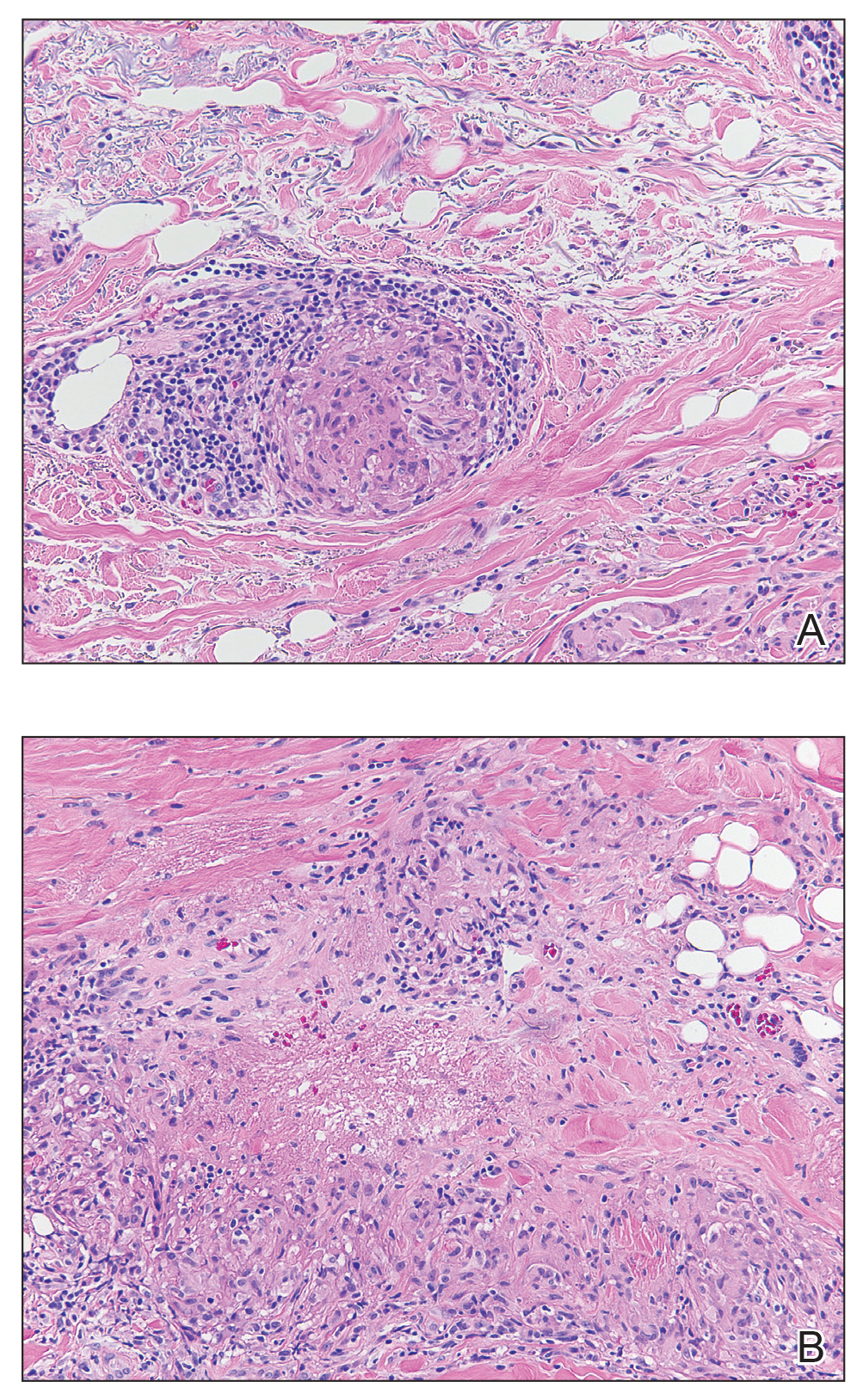

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

The Diagnosis: Lichen Nitidus

Our patient represents a case of lichen nitidus (LN) that was diagnosed through clinicopathologic correlation, with the pathology results showing a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis enclosed by acanthotic rete ridges on either side. Lichen nitidus was first described by Pinkus in 1901 as a variant of lichen planus.1 It is a rare chronic inflammatory disease that is most prevalent in children and adolescents.2 Clinically, the lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, shiny, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication.3 Typically, lesions are localized and discrete; however, vesicular, hemorrhagic, perforating, spinous follicular, linear, generalized, and actinic variants all have been reported in the literature. Lichen nitidus has a predilection for the lower abdomen, medial thighs, penis, forearms, ventral wrists, and hands.4 Cases of LN have been reported on the palms, soles, nails, and mucosa, presenting a diagnostic challenge.5 The pathogenesis of LN is unknown, and all races and sexes are affected equally.6

Histopathologically, LN has distinct findings including a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis embraced by elongated and acanthotic rete ridges.2 These histopathologic characteristics were seen in our patient's biopsy specimen (Figure) and have been described as the ball-and-claw configuration. Lichen nitidus may be pruritic but typically is asymptomatic.7 It often spontaneously regresses within months to years without any treatment7; however, successful outcomes have been seen with topical steroids, UVA/UVB phototherapy, and retinoids.2 Our patient was treated with topical steroids.

The differential diagnosis for LN includes verruca plana, dyshidrotic eczema, acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM), and molluscum contagiosum. Verruca plana can occur as 1- to 5-mm, grouped, flesh-colored papules on the face, neck, dorsal hands, wrists, or knees.8 Most commonly, verruca plana occurs due to human papillomavirus type 3 and less commonly human papillomavirus types 10, 27, and 41. Verruca plana is easily differentiated from LN on pathology with findings of epidermal hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and koilocytic changes.8

Dyshidrotic eczema is a pruritic vesicular rash that is classically distributed symmetrically on the palmar aspects of the hands and lateral fingers.9 Histopathology of the lesions reveals spongiosis with an epidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Exacerbating factors include exposure to allergens, stress, fungal infections, and genetic predisposition.9

Acral persistent papular mucinosis can present as multiple, 2- to 5-mm, flesh-colored papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands.10 However, the demographic is different from LN, as APPM most commonly affects middle-aged females versus adolescents. Lesions of APPM may multiply or spontaneously remit over time. Acral persistent papular mucinosis generally is asymptomatic but can be treated with cryotherapy, topical corticosteroids, electrodesiccation, or CO2 lasers for cosmetic purposes. Acral persistent papular mucinosis can be easily distinguished from LN on histology, as it will show areas of focal, well-circumscribed mucin in the papillary dermis and a spared Grenz zone.10

Molluscum contagiosum is a common viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus that affects children and adults.11 The skin lesions appear as 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules with central umbilication on the limbs, trunk, or face. Clinicians may choose to monitor lesions of molluscum contagiosum, as it is a self-limited condition, or it may be treated with cryotherapy, salicylic acid, imiquimod, curettage, laser, or cimetidine.11 On histology, epidermal budlike proliferations can be appreciated in the dermis, and characteristic large, eosinophilic, intracytoplasmic inclusion or molluscum bodies are found in the epidermis.12

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

- Barber HW. Case of lichen nitidus (Pinkus) or tuberculide lichéniforme et nitida (Chatellier). Proc R Soc Med. 1924;17:39.

- Frey MN, Luzzatto L, Seidel GB, et al. Case for diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:561-563.

- Pielop JA, Hsu S. Tiny, skin-colored papules on the arms and hands. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:343-344.

- Cho EB, Kim HY, Park EJ, et al. Three cases of lichen nitidus associated with various cutaneous diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:505-509.

- Podder I, Mohanty S, Chandra S, et al. Isolated palmar lichen nitidus--a diagnostic challenge: first case from Eastern India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:308-309.

- Chen W, Schramm M, Zouboulis C. Generalized lichen nitidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:630-631.

- Rallis E, Verros C, Moussatou V, et al. Generalized purpuric lichen nitidus: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:5.

- Pavithra S, Mallya H, Pai GS. Extensive presentation of verruca plana in a healthy individual. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:324-325.

- Paulsen L, Geller D, Guggenbiller M. Symmetrical vesicular eruption on the palms. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15:811-812.

- Alvarez-Garrido H, Najera L, Garrido-Rios A, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: is it an under-diagnosed disease? Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:10

- Diaconu R, Oprea B, Vasilescu M, et al. Inflamed molluscum contagiosum in a 6-year-old boy: a case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:843-845.

- Krishnamurthy J, Nagappa D. The cytology of molluscum contagiosum mimicking skin adnexal tumor. J Cytol. 2010;27:74.

A 13-year-old otherwise healthy adolescent boy presented to the dermatology clinic for a rash on the bilateral dorsal hands of approximately 1 year’s duration. The rash was asymptomatic with no pain or pruritus reported. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished adolescent boy in no acute distress with 1- to 2-mm flesh-colored papules clustered on the bilateral dorsal fingers.

Papules and Telangiectases on the Distal Fingers of a Child

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory myopathy of childhood that is autoimmune in nature with an annual incidence ranging from 2.5 to 4.1 cases per million children. Its peak incidence is between 5 and 10 years of age, and it affects girls more than boys at a 2-fold to 5-fold greater rate.1 Juvenile dermatomyositis is characterized by skeletal muscle weakness in the presence of distinctive rashes, including Gottron papules and heliotrope erythema. Muscle weakness typically is proximal and symmetrical, and eventually patients may have trouble rising from a seated position or lifting objects overhead. Other skin manifestations include nail fold capillary changes, calcinosis cutis, and less commonly ulcerations signifying vasculopathy of the skin.2 A subset of patients will present with juvenile amyopathic dermatomyositis. These children have the characteristic skin changes without the muscle weakness or elevated muscle enzymes for more than 6 months; however, one-quarter may go on to develop mysositis.3

Diagnosis of JDM traditionally was based on the following 5 diagnostic criteria: characteristic skin rash, proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, myopathic changes on electromyogram, and typical muscle biopsy.1 Current practice shows a broadening of diagnostic criteria using new techniques in the diagnosis of JDM. To make the diagnosis, the patient must have the characteristic skin manifestations with a minimum of 3 other criteria.4 A 2006 international consensus survey expanded the list of criteria to include typical findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nail fold capillaroscopy abnormalities, calcinosis, and

dysphonia.5

To assess muscle disease, MRI is utilized because it is a reliable noninvasive tool to assess muscle inflammation. Muscle biopsy is only recommended if the diagnosis is unclear.5 The results of the MRI in our patient displayed symmetric mild fatty atrophy of the gluteus maximus muscle, as well as edema in the right rectus femoris and left vastus lateralis muscles, suggesting early findings of myositis. Muscle enzymes may not be diagnostic because they are not always elevated at diagnosis. Our patient had a normal creatinine kinase level (92 U/L [reference range, <190 U/L]), and both aldolase and lactate dehydrogenase also were within reference range. Conversely, antinuclear antibodies frequently are positive in patients with JDM, such as in our patient at a 1:320 dilution, but are nonspecific and nondiagnostic. It is recommended to include nail fold capillaroscopy to evaluate periungual capillary changes because nailfold capillary density is a sensitive measure of both skin and muscle disease.5 Using dermoscopy, nail fold capillary dilation was observed in our patient.

Other differential diagnoses can have somewhat similar clinical features to JDM. Infantile papular acrodermatitis, commonly referred to as Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, is a viral exanthem that affects children (median age, 2 years).6 The rash appears as monomorphous, flat-topped, pink to brown papules affecting the face, buttocks, and arms; it typically spontaneously resolves in 10 days.6

Juvenile-onset lupus is a chronic autoimmune disorder that can involve any organ system and typically affects children aged 11 to 12 years with a female preponderance. Skin manifestations are similar to adult-onset lupus and include malar rash, discoid rash, oral ulcerations, petechiae, palpable purpura, and digital telangiectasia and ulcers. 7

Juvenile scleroderma is rare connective-tissue disorder that also has multiple organ involvement. Cutaneous involvement can range from isolated morphealike plaques to diffuse sclerotic lesions with growth disturbances, contractures, and facial atrophy.8

Verrucae planae, commonly referred to as flat warts, are papules caused primarily by human papillomavirus types 3, 10, 28, and 41. Children and young adults commonly are affected, and warts can appear on the hands, as in our patient.6

Treatment of JDM depends on disease severity at initial presentation and requires a multidisciplinary approach. The mainstay of treatment is high-dose oral prednisone in combination with disease-modifying drugs such as methotrexate and cyclosporin A. Patients with more severe presentations (eg, ulcerative skin disease) or life-threatening organ involvement are treated with cyclophosphamide, usually in combination with high-dose glucocorticoids.9

Early detection with aggressive treatment is vital to reduce morbidity and mortality from organ damage and disease complications. Mortality rates have dropped to 3%10 in recent decades with the use of systemic glucocorticoids. Delayed treatment is associated with a prolonged disease course and poorer outcomes. Disease complications in children with JDM include osteoporosis, calcinosis, and intestinal perforation; however, with early treatment, children with JDM can expect full recovery and to live a normal life as compared to adults with dermatomyositis.10

Prior to our patient's diagnosis, the family was assigned to move to an overseas location through the US Military with no direct access to advanced medical care. Early detection and diagnosis of JDM through an astute clinical examination allowed the patient and her family to remain in the continental United States to continue receiving specialty care.

- Mendez EP, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. US incidence of juvenile dermatomyositis,1995-1998: results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:300-305.

- Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN, et al. The clinical phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine. 2013;92:25-41.

- Gerami P, Walling HW, Lewis J, et al. A systematic review of juvenile-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;57:637-644.

- Enders FB, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:329-340.

- Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, et al. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:990-993.

- William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Viral diseases. In: William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:360-413.

- Levy DM, Kamphuis S. Systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59:345-364.

- Li SC, Torok KS, Pope E, et al; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Localized Scleroderma Workgroup. Development of consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma: a roadmap toward comparative effectiveness studies in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1175-1185.

- Stringer E, Ota S, Bohnsack J, et al. Treatment approaches to juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) across North America: the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) JDM treatment study. J Rhematol. 2010;37:S1953-S1961.

- Huber AM, Feldman BM. Long-term outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis: how did we get here and where are we going? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:441-446.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory myopathy of childhood that is autoimmune in nature with an annual incidence ranging from 2.5 to 4.1 cases per million children. Its peak incidence is between 5 and 10 years of age, and it affects girls more than boys at a 2-fold to 5-fold greater rate.1 Juvenile dermatomyositis is characterized by skeletal muscle weakness in the presence of distinctive rashes, including Gottron papules and heliotrope erythema. Muscle weakness typically is proximal and symmetrical, and eventually patients may have trouble rising from a seated position or lifting objects overhead. Other skin manifestations include nail fold capillary changes, calcinosis cutis, and less commonly ulcerations signifying vasculopathy of the skin.2 A subset of patients will present with juvenile amyopathic dermatomyositis. These children have the characteristic skin changes without the muscle weakness or elevated muscle enzymes for more than 6 months; however, one-quarter may go on to develop mysositis.3

Diagnosis of JDM traditionally was based on the following 5 diagnostic criteria: characteristic skin rash, proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, myopathic changes on electromyogram, and typical muscle biopsy.1 Current practice shows a broadening of diagnostic criteria using new techniques in the diagnosis of JDM. To make the diagnosis, the patient must have the characteristic skin manifestations with a minimum of 3 other criteria.4 A 2006 international consensus survey expanded the list of criteria to include typical findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nail fold capillaroscopy abnormalities, calcinosis, and

dysphonia.5

To assess muscle disease, MRI is utilized because it is a reliable noninvasive tool to assess muscle inflammation. Muscle biopsy is only recommended if the diagnosis is unclear.5 The results of the MRI in our patient displayed symmetric mild fatty atrophy of the gluteus maximus muscle, as well as edema in the right rectus femoris and left vastus lateralis muscles, suggesting early findings of myositis. Muscle enzymes may not be diagnostic because they are not always elevated at diagnosis. Our patient had a normal creatinine kinase level (92 U/L [reference range, <190 U/L]), and both aldolase and lactate dehydrogenase also were within reference range. Conversely, antinuclear antibodies frequently are positive in patients with JDM, such as in our patient at a 1:320 dilution, but are nonspecific and nondiagnostic. It is recommended to include nail fold capillaroscopy to evaluate periungual capillary changes because nailfold capillary density is a sensitive measure of both skin and muscle disease.5 Using dermoscopy, nail fold capillary dilation was observed in our patient.

Other differential diagnoses can have somewhat similar clinical features to JDM. Infantile papular acrodermatitis, commonly referred to as Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, is a viral exanthem that affects children (median age, 2 years).6 The rash appears as monomorphous, flat-topped, pink to brown papules affecting the face, buttocks, and arms; it typically spontaneously resolves in 10 days.6

Juvenile-onset lupus is a chronic autoimmune disorder that can involve any organ system and typically affects children aged 11 to 12 years with a female preponderance. Skin manifestations are similar to adult-onset lupus and include malar rash, discoid rash, oral ulcerations, petechiae, palpable purpura, and digital telangiectasia and ulcers. 7

Juvenile scleroderma is rare connective-tissue disorder that also has multiple organ involvement. Cutaneous involvement can range from isolated morphealike plaques to diffuse sclerotic lesions with growth disturbances, contractures, and facial atrophy.8

Verrucae planae, commonly referred to as flat warts, are papules caused primarily by human papillomavirus types 3, 10, 28, and 41. Children and young adults commonly are affected, and warts can appear on the hands, as in our patient.6

Treatment of JDM depends on disease severity at initial presentation and requires a multidisciplinary approach. The mainstay of treatment is high-dose oral prednisone in combination with disease-modifying drugs such as methotrexate and cyclosporin A. Patients with more severe presentations (eg, ulcerative skin disease) or life-threatening organ involvement are treated with cyclophosphamide, usually in combination with high-dose glucocorticoids.9

Early detection with aggressive treatment is vital to reduce morbidity and mortality from organ damage and disease complications. Mortality rates have dropped to 3%10 in recent decades with the use of systemic glucocorticoids. Delayed treatment is associated with a prolonged disease course and poorer outcomes. Disease complications in children with JDM include osteoporosis, calcinosis, and intestinal perforation; however, with early treatment, children with JDM can expect full recovery and to live a normal life as compared to adults with dermatomyositis.10

Prior to our patient's diagnosis, the family was assigned to move to an overseas location through the US Military with no direct access to advanced medical care. Early detection and diagnosis of JDM through an astute clinical examination allowed the patient and her family to remain in the continental United States to continue receiving specialty care.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory myopathy of childhood that is autoimmune in nature with an annual incidence ranging from 2.5 to 4.1 cases per million children. Its peak incidence is between 5 and 10 years of age, and it affects girls more than boys at a 2-fold to 5-fold greater rate.1 Juvenile dermatomyositis is characterized by skeletal muscle weakness in the presence of distinctive rashes, including Gottron papules and heliotrope erythema. Muscle weakness typically is proximal and symmetrical, and eventually patients may have trouble rising from a seated position or lifting objects overhead. Other skin manifestations include nail fold capillary changes, calcinosis cutis, and less commonly ulcerations signifying vasculopathy of the skin.2 A subset of patients will present with juvenile amyopathic dermatomyositis. These children have the characteristic skin changes without the muscle weakness or elevated muscle enzymes for more than 6 months; however, one-quarter may go on to develop mysositis.3

Diagnosis of JDM traditionally was based on the following 5 diagnostic criteria: characteristic skin rash, proximal muscle weakness, elevated muscle enzymes, myopathic changes on electromyogram, and typical muscle biopsy.1 Current practice shows a broadening of diagnostic criteria using new techniques in the diagnosis of JDM. To make the diagnosis, the patient must have the characteristic skin manifestations with a minimum of 3 other criteria.4 A 2006 international consensus survey expanded the list of criteria to include typical findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nail fold capillaroscopy abnormalities, calcinosis, and

dysphonia.5

To assess muscle disease, MRI is utilized because it is a reliable noninvasive tool to assess muscle inflammation. Muscle biopsy is only recommended if the diagnosis is unclear.5 The results of the MRI in our patient displayed symmetric mild fatty atrophy of the gluteus maximus muscle, as well as edema in the right rectus femoris and left vastus lateralis muscles, suggesting early findings of myositis. Muscle enzymes may not be diagnostic because they are not always elevated at diagnosis. Our patient had a normal creatinine kinase level (92 U/L [reference range, <190 U/L]), and both aldolase and lactate dehydrogenase also were within reference range. Conversely, antinuclear antibodies frequently are positive in patients with JDM, such as in our patient at a 1:320 dilution, but are nonspecific and nondiagnostic. It is recommended to include nail fold capillaroscopy to evaluate periungual capillary changes because nailfold capillary density is a sensitive measure of both skin and muscle disease.5 Using dermoscopy, nail fold capillary dilation was observed in our patient.

Other differential diagnoses can have somewhat similar clinical features to JDM. Infantile papular acrodermatitis, commonly referred to as Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, is a viral exanthem that affects children (median age, 2 years).6 The rash appears as monomorphous, flat-topped, pink to brown papules affecting the face, buttocks, and arms; it typically spontaneously resolves in 10 days.6

Juvenile-onset lupus is a chronic autoimmune disorder that can involve any organ system and typically affects children aged 11 to 12 years with a female preponderance. Skin manifestations are similar to adult-onset lupus and include malar rash, discoid rash, oral ulcerations, petechiae, palpable purpura, and digital telangiectasia and ulcers. 7

Juvenile scleroderma is rare connective-tissue disorder that also has multiple organ involvement. Cutaneous involvement can range from isolated morphealike plaques to diffuse sclerotic lesions with growth disturbances, contractures, and facial atrophy.8

Verrucae planae, commonly referred to as flat warts, are papules caused primarily by human papillomavirus types 3, 10, 28, and 41. Children and young adults commonly are affected, and warts can appear on the hands, as in our patient.6

Treatment of JDM depends on disease severity at initial presentation and requires a multidisciplinary approach. The mainstay of treatment is high-dose oral prednisone in combination with disease-modifying drugs such as methotrexate and cyclosporin A. Patients with more severe presentations (eg, ulcerative skin disease) or life-threatening organ involvement are treated with cyclophosphamide, usually in combination with high-dose glucocorticoids.9

Early detection with aggressive treatment is vital to reduce morbidity and mortality from organ damage and disease complications. Mortality rates have dropped to 3%10 in recent decades with the use of systemic glucocorticoids. Delayed treatment is associated with a prolonged disease course and poorer outcomes. Disease complications in children with JDM include osteoporosis, calcinosis, and intestinal perforation; however, with early treatment, children with JDM can expect full recovery and to live a normal life as compared to adults with dermatomyositis.10

Prior to our patient's diagnosis, the family was assigned to move to an overseas location through the US Military with no direct access to advanced medical care. Early detection and diagnosis of JDM through an astute clinical examination allowed the patient and her family to remain in the continental United States to continue receiving specialty care.

- Mendez EP, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. US incidence of juvenile dermatomyositis,1995-1998: results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:300-305.

- Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN, et al. The clinical phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine. 2013;92:25-41.

- Gerami P, Walling HW, Lewis J, et al. A systematic review of juvenile-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;57:637-644.

- Enders FB, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:329-340.

- Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, et al. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:990-993.

- William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Viral diseases. In: William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:360-413.

- Levy DM, Kamphuis S. Systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59:345-364.

- Li SC, Torok KS, Pope E, et al; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Localized Scleroderma Workgroup. Development of consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma: a roadmap toward comparative effectiveness studies in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1175-1185.

- Stringer E, Ota S, Bohnsack J, et al. Treatment approaches to juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) across North America: the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) JDM treatment study. J Rhematol. 2010;37:S1953-S1961.

- Huber AM, Feldman BM. Long-term outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis: how did we get here and where are we going? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:441-446.

- Mendez EP, Lipton R, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. US incidence of juvenile dermatomyositis,1995-1998: results from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:300-305.

- Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN, et al. The clinical phenotypes of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine. 2013;92:25-41.

- Gerami P, Walling HW, Lewis J, et al. A systematic review of juvenile-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;57:637-644.

- Enders FB, Bader-Meunier B, Baildam E, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of juvenile dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:329-340.

- Brown VE, Pilkington CA, Feldman BM, et al. An international consensus survey of the diagnostic criteria for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:990-993.

- William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Viral diseases. In: William JD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:360-413.

- Levy DM, Kamphuis S. Systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59:345-364.

- Li SC, Torok KS, Pope E, et al; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Localized Scleroderma Workgroup. Development of consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma: a roadmap toward comparative effectiveness studies in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1175-1185.

- Stringer E, Ota S, Bohnsack J, et al. Treatment approaches to juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) across North America: the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) JDM treatment study. J Rhematol. 2010;37:S1953-S1961.

- Huber AM, Feldman BM. Long-term outcomes in juvenile dermatomyositis: how did we get here and where are we going? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:441-446.

A 4-year-old girl presented to our dermatology clinic with asymptomatic flesh-colored bumps on the fingers of 2 to 3 months’ duration. Prior to presentation the patient was otherwise healthy with normal growth and development. She was referred to dermatology for recommended treatment options for suspected flat warts. On physical examination, grouped 1- to 3-mm, smooth, flat-topped papules were found on the dorsal aspects of the distal interphalangeal joints of all fingers (top). The papules were nonpruritic. Additionally, there were nail findings of ragged cuticles and dilated capillary loops in the proximal nail folds (bottom). The patient did not bite her nails, per the mother’s report, and no other rashes were noted. There were no systemic symptoms or reports of muscle fatigue. She was positive for antinuclear antibodies at 1:320 dilution. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thighs and pelvis was ordered.

Asymptomatic Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) were first described in 1996.1 They comprise a family of rare mesenchymal neoplasms that have a unique characteristic of staining positive for melanocytic and smooth muscle markers on immunohistochemistry.2 These neoplasms have been described in many areas of the body including the uterus, bladder, heart, pancreas, and prostate. The majority of PEComas are extracutaneous, with only 8% of reported cases originating on the skin.3 A case of primary cutaneous PEComa (pcPEComa) was described in 2003.4 The primary cutaneous form is extremely rare.3,5-7

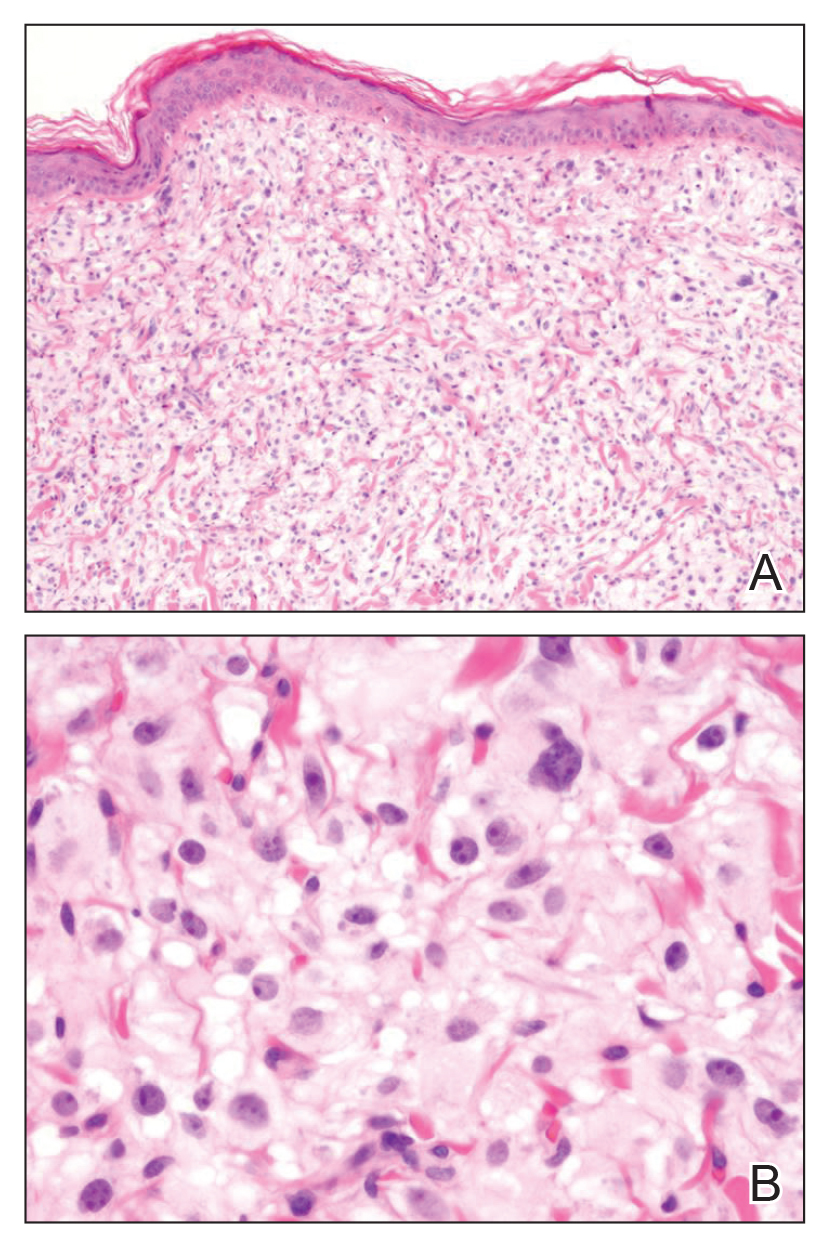

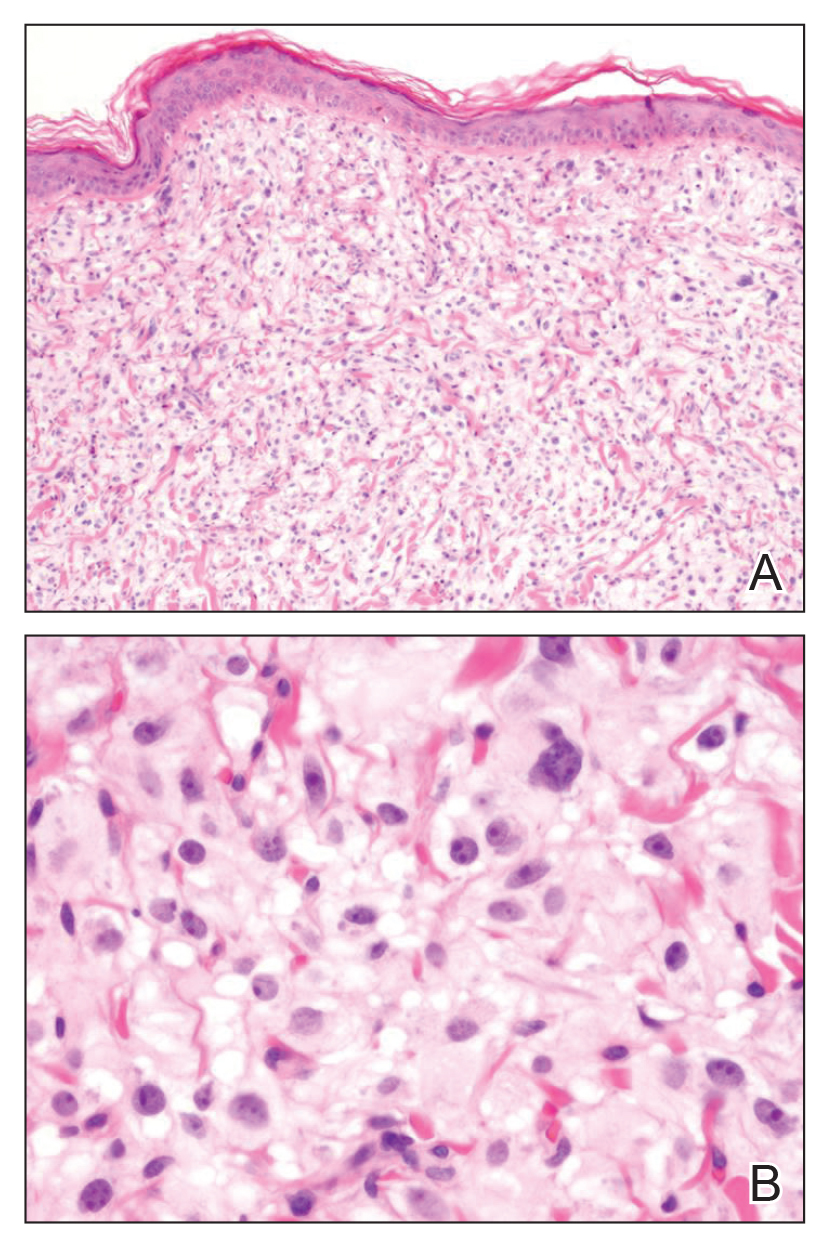

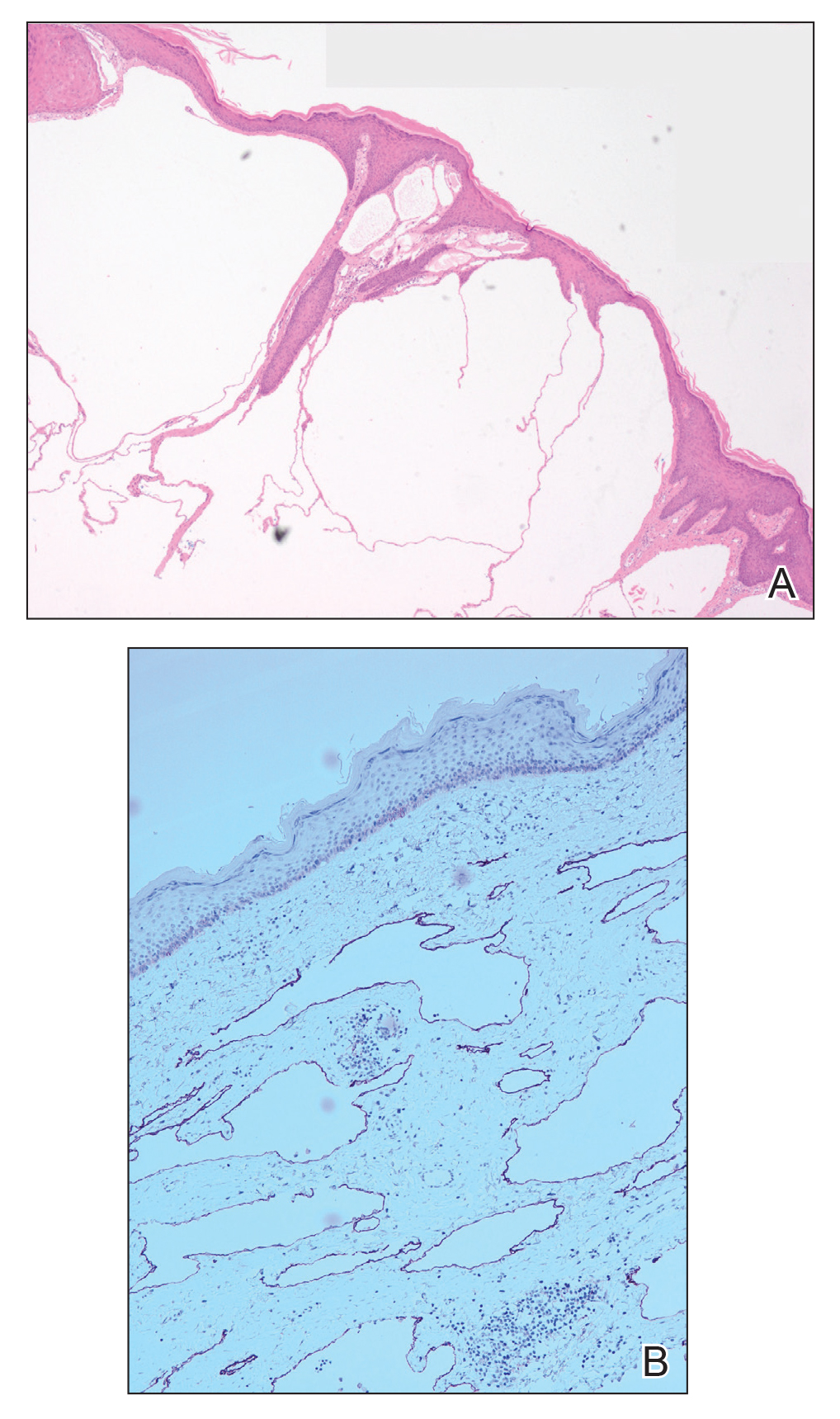

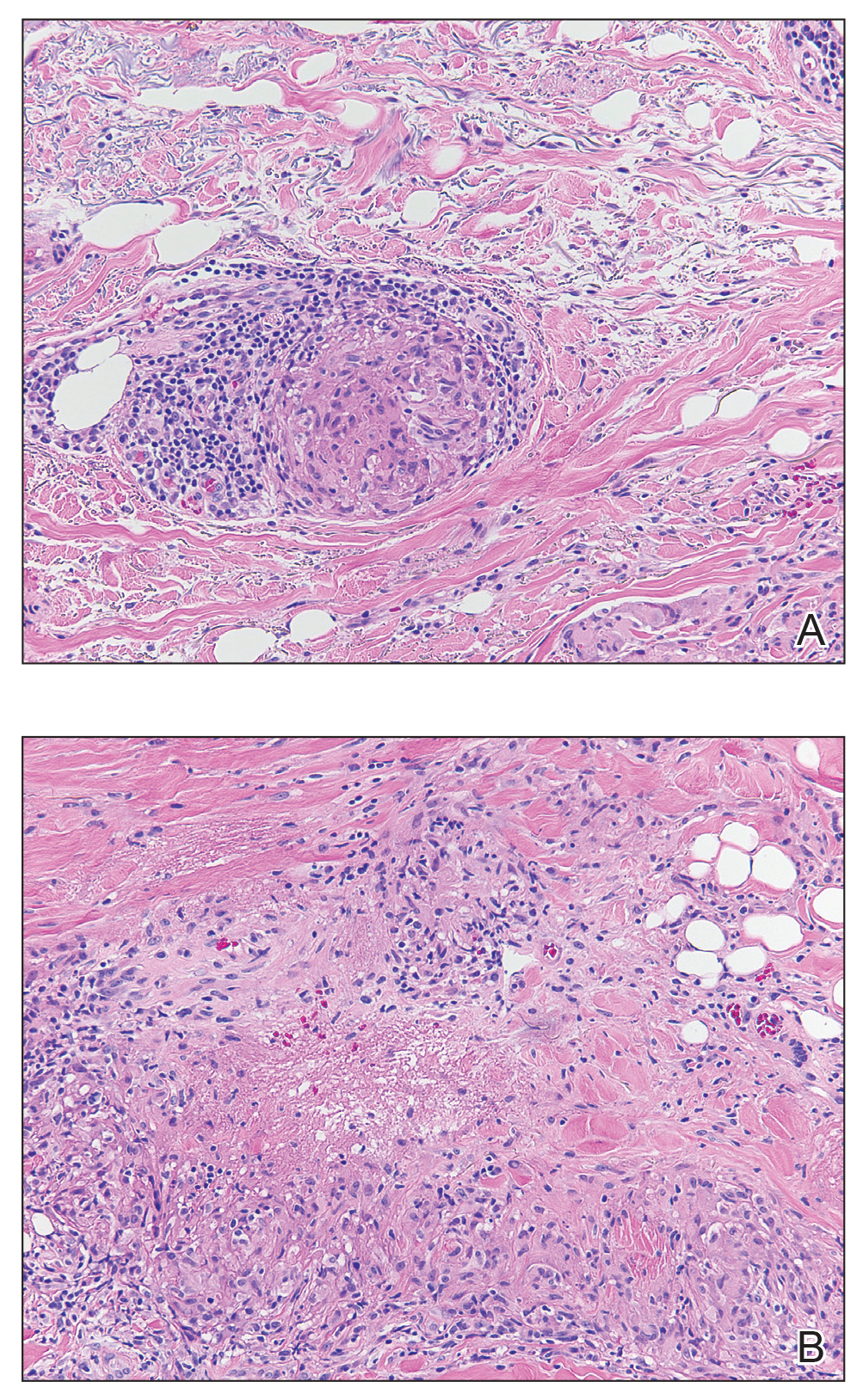

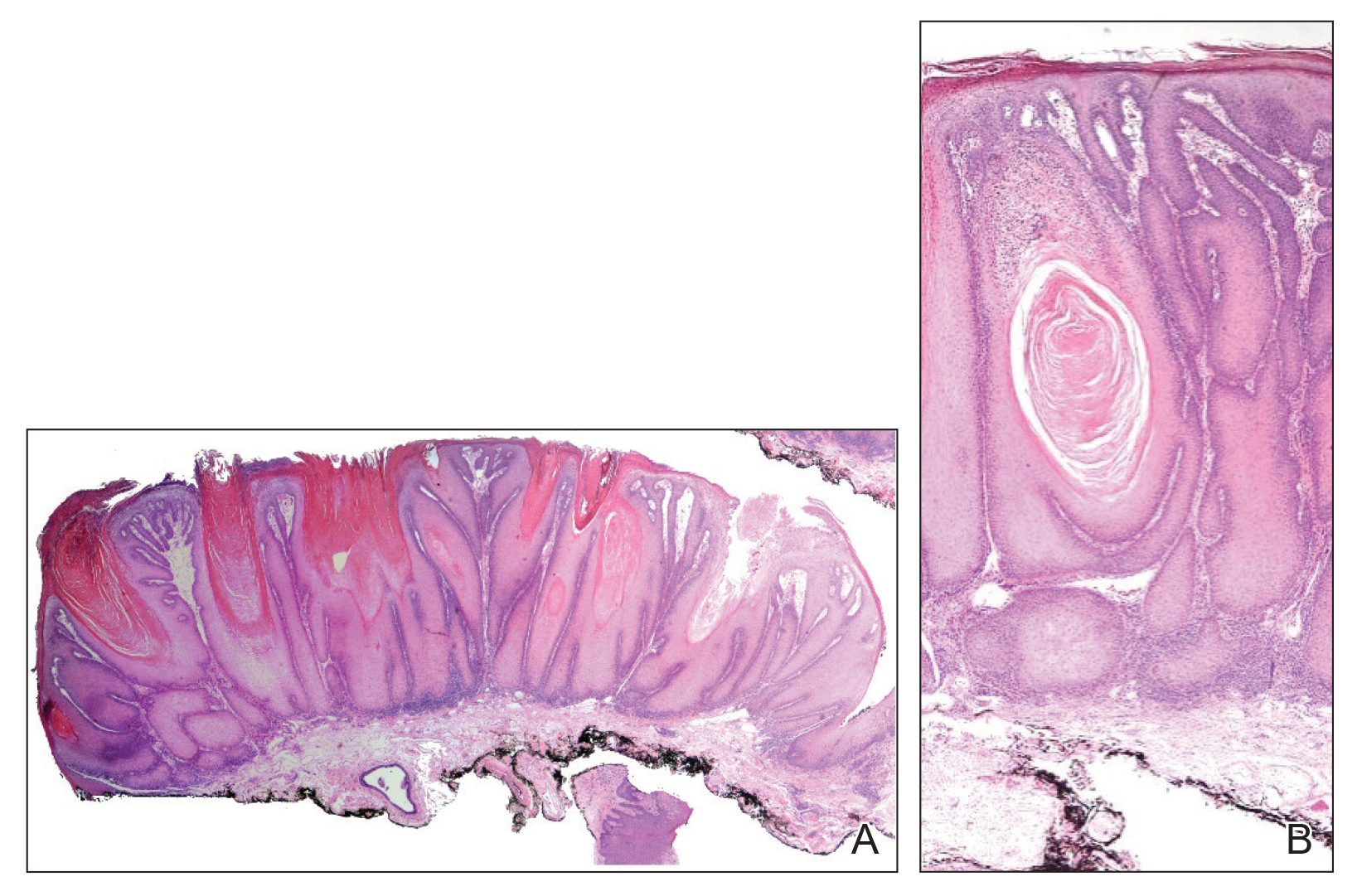

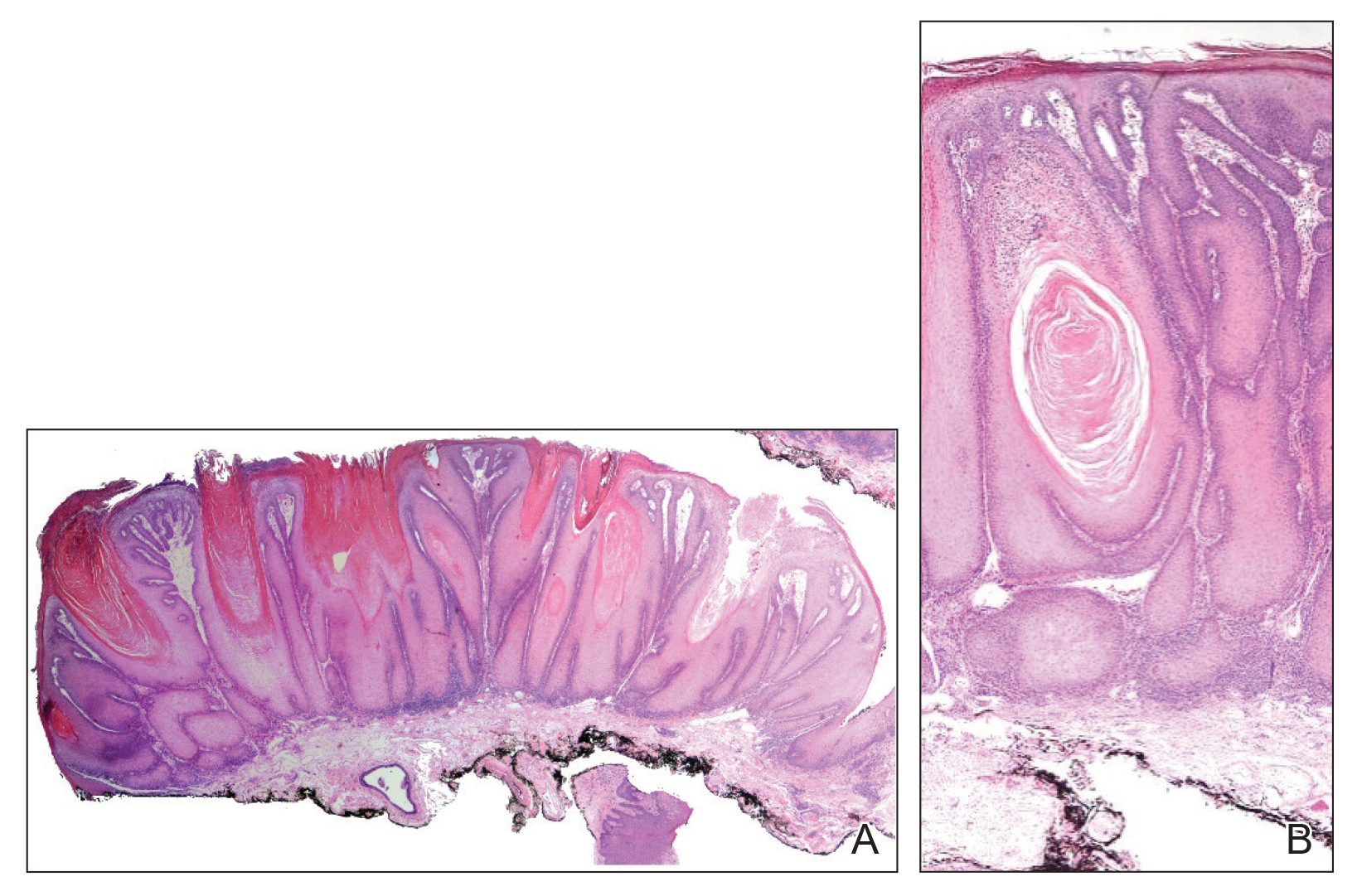

A broad deep shave biopsy was performed in our patient in an attempt to sample the entire lesion. Histopathologic examination of the nodule demonstrated a dermal neoplasm comprised of a diffuse proliferation of large polygonal cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, fine chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1A). Higher-power magnification showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism and only rare mitotic figures (Figure 1B).

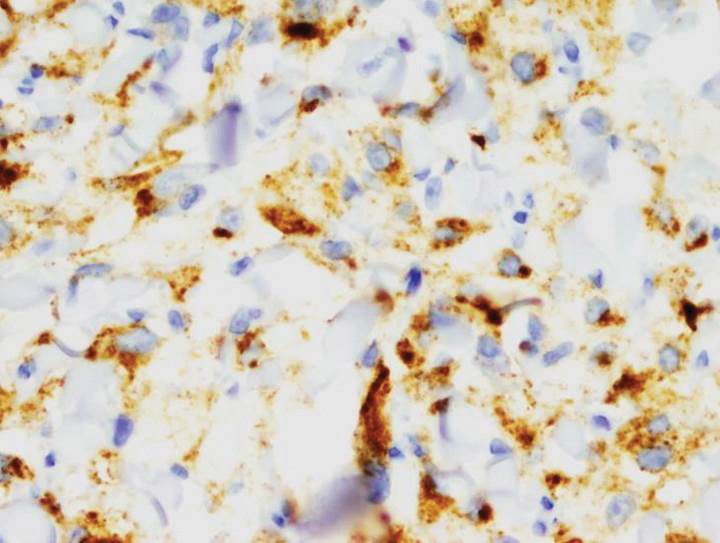

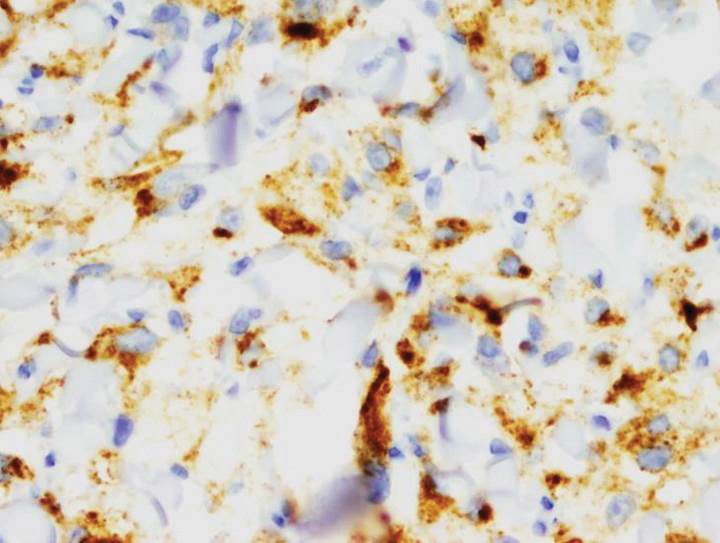

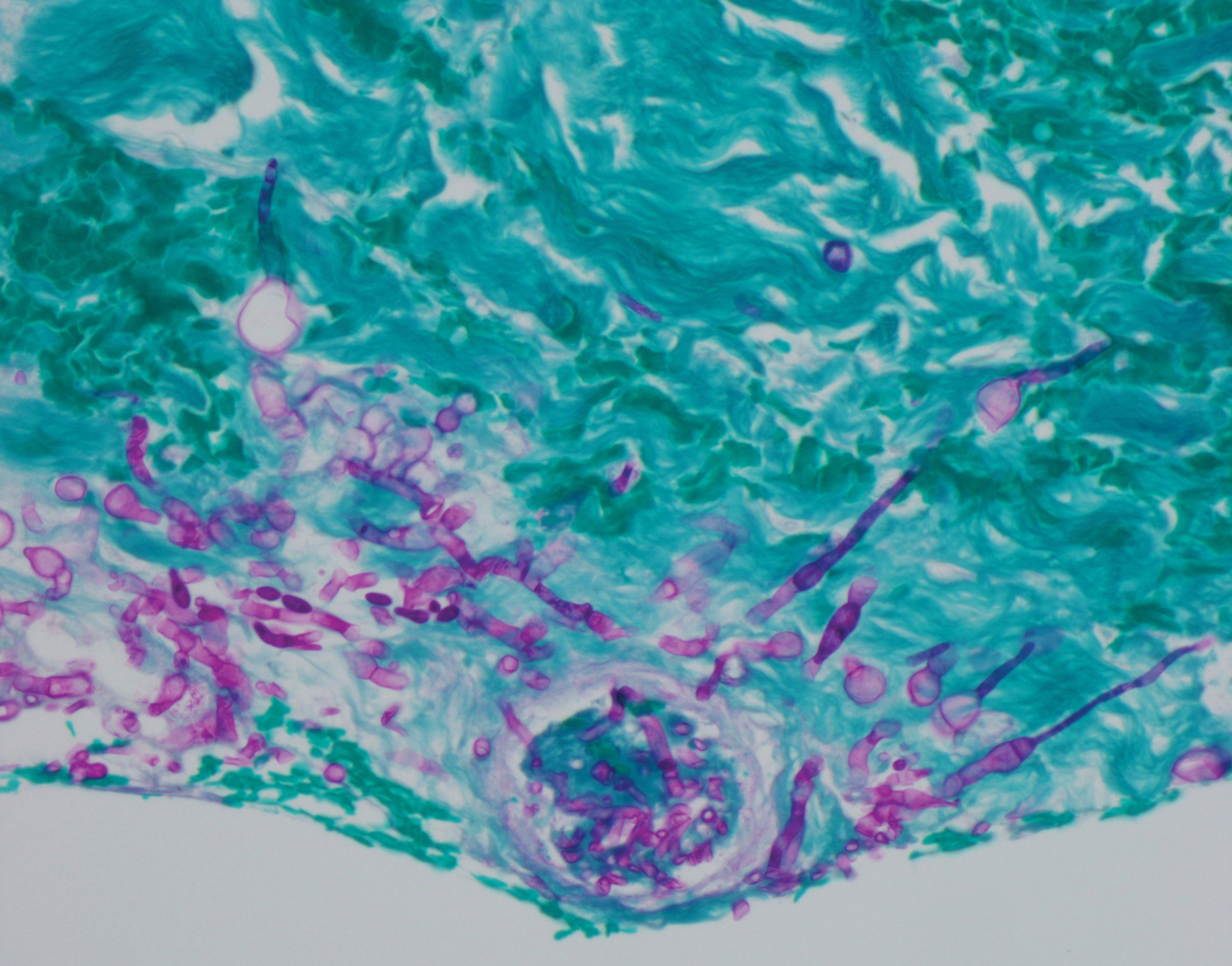

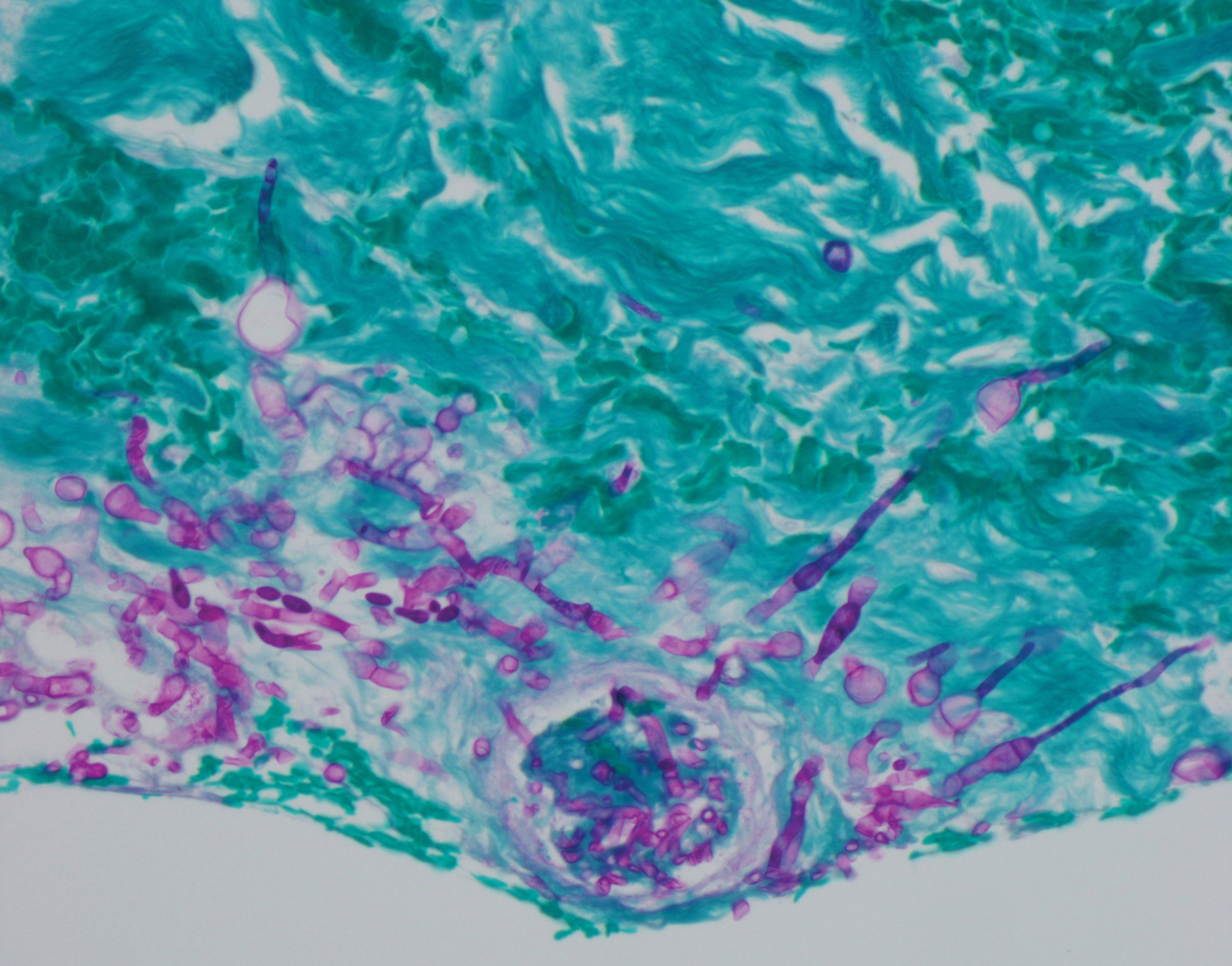

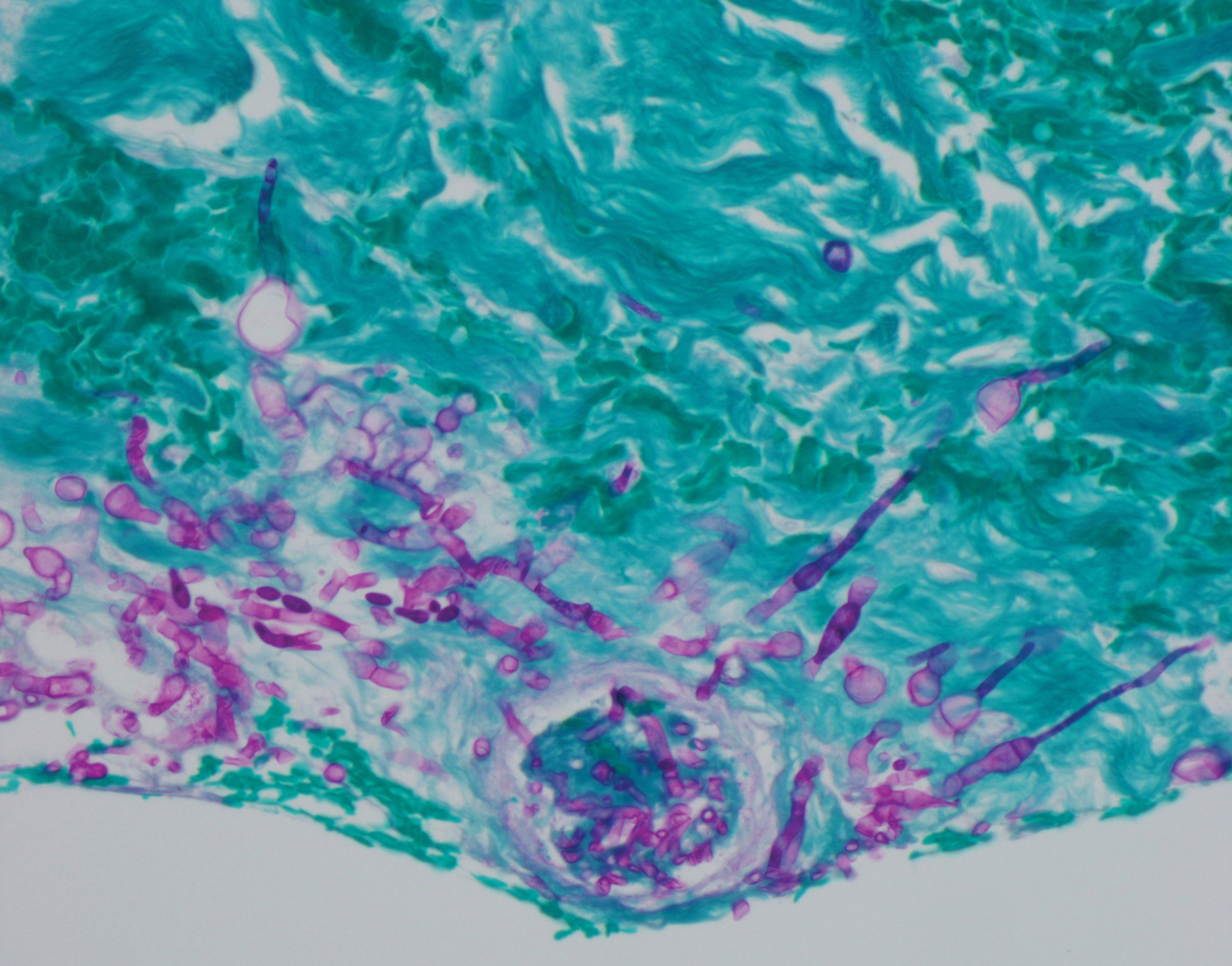

Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for myomelanocytic markers with positivity for human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 2) and desmin (not shown). Additionally, the tumor was positive for CD163 and negative for smooth muscle actin, cytokeratin, and S-100 protein.