User login

Hyperpigmented Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

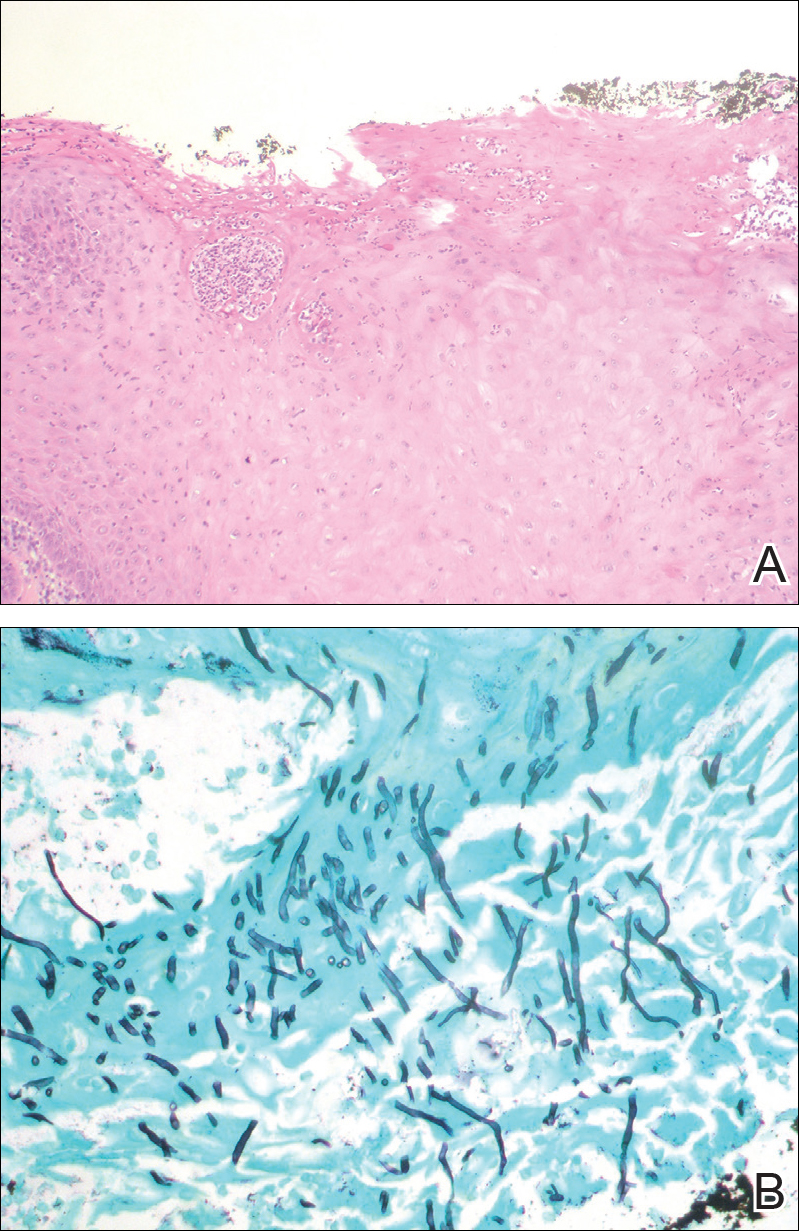

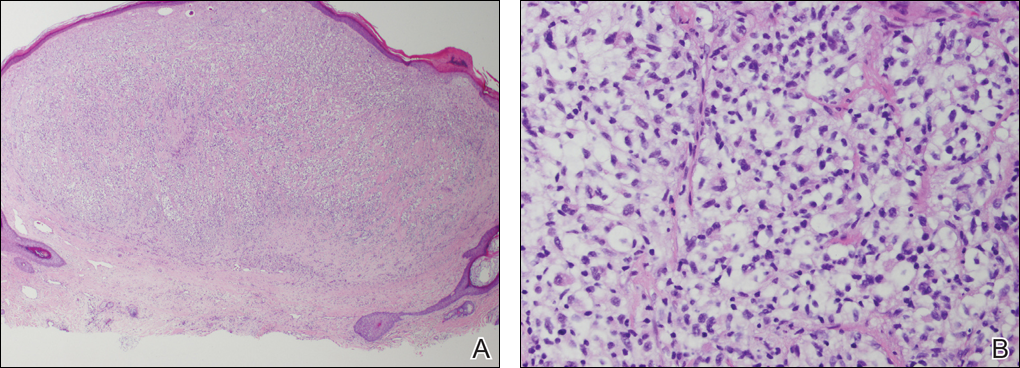

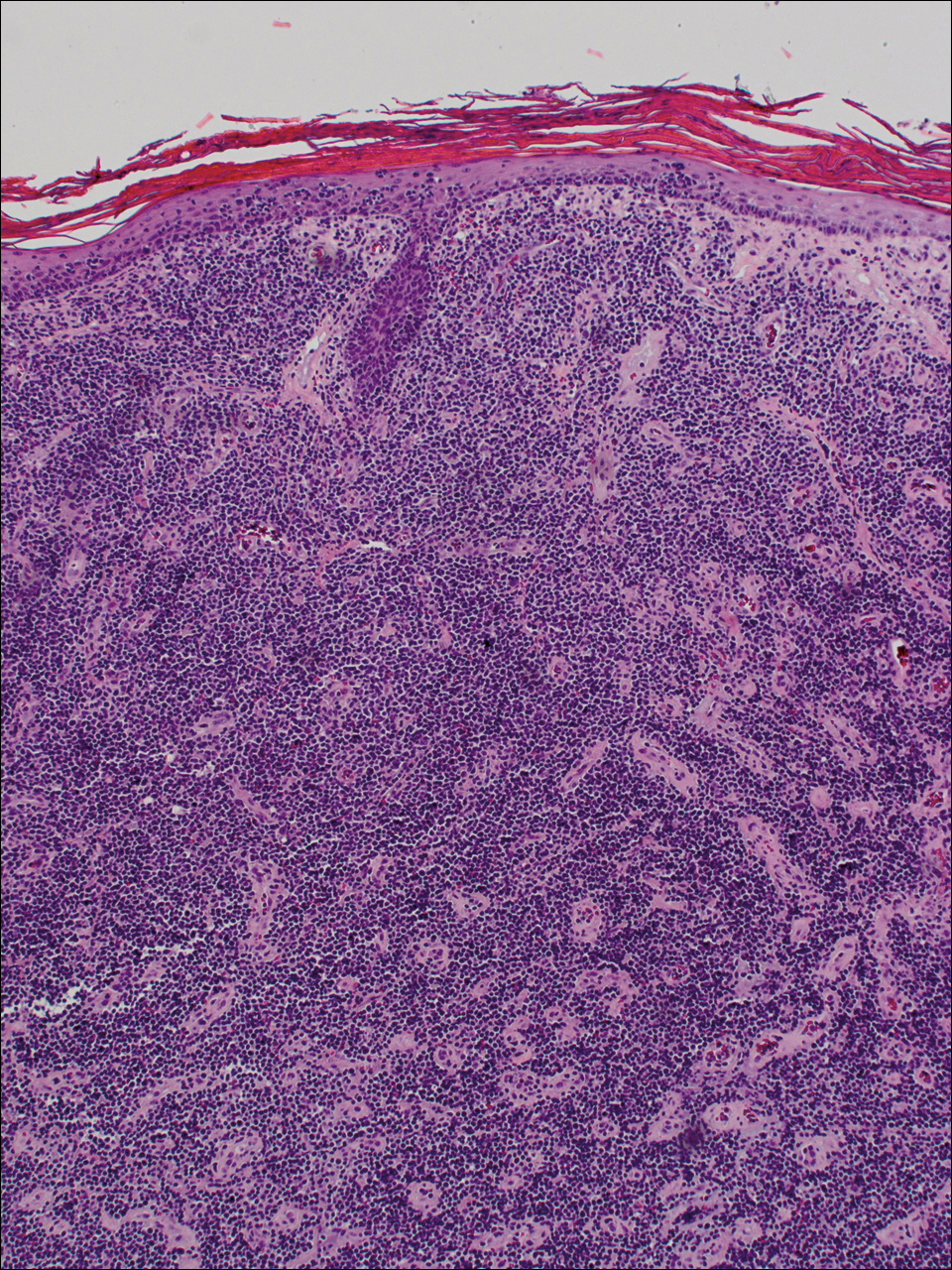

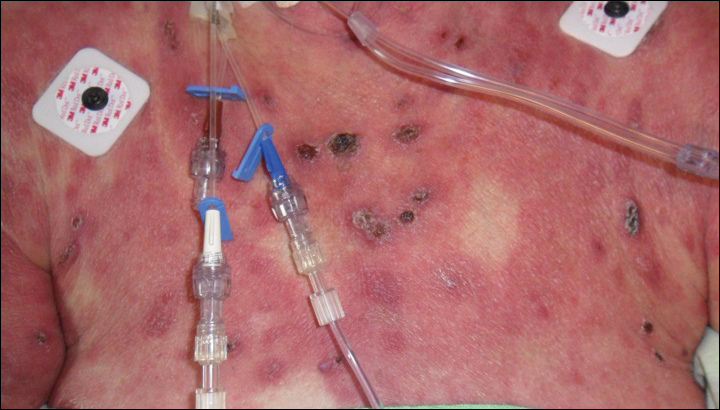

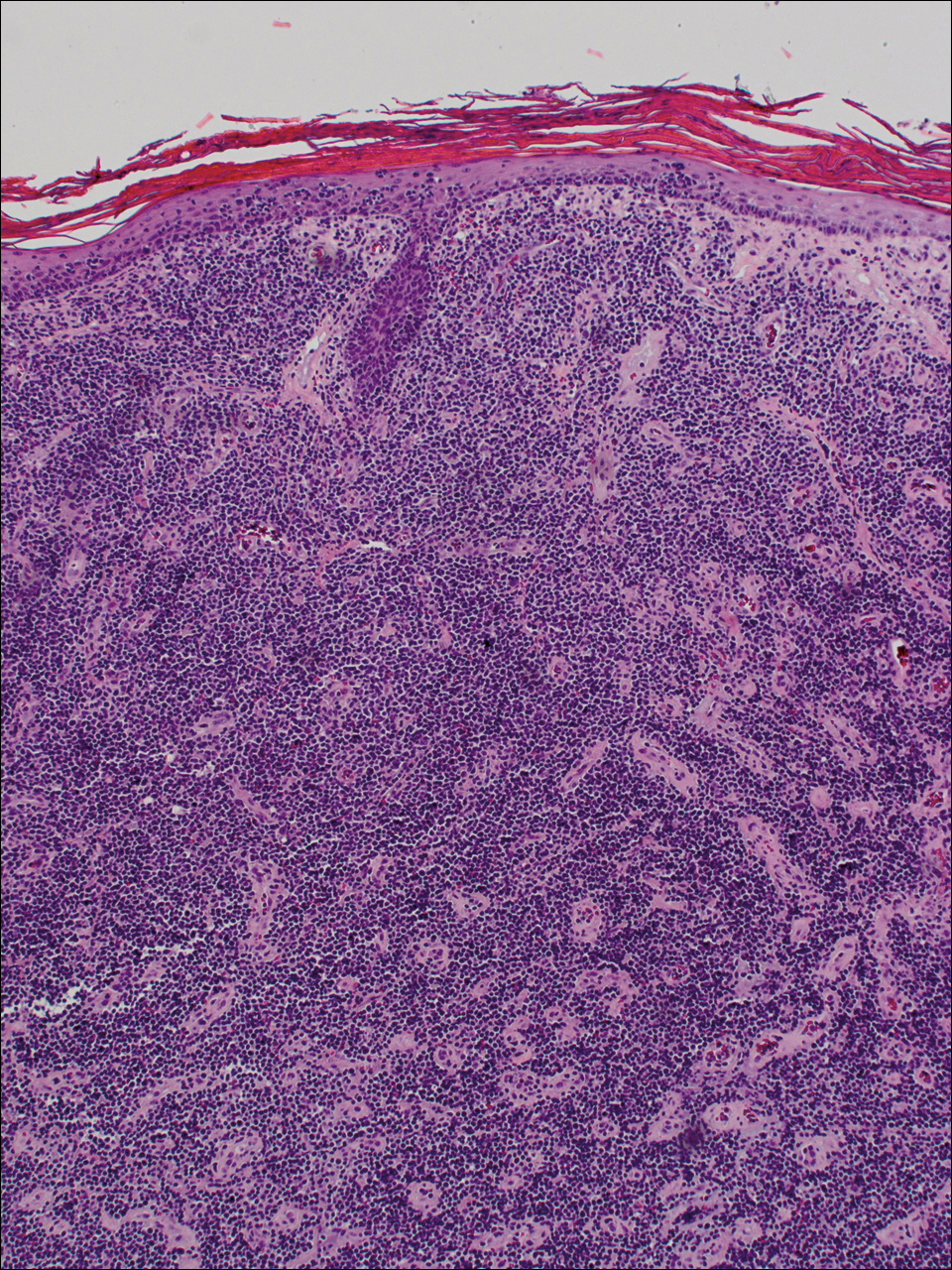

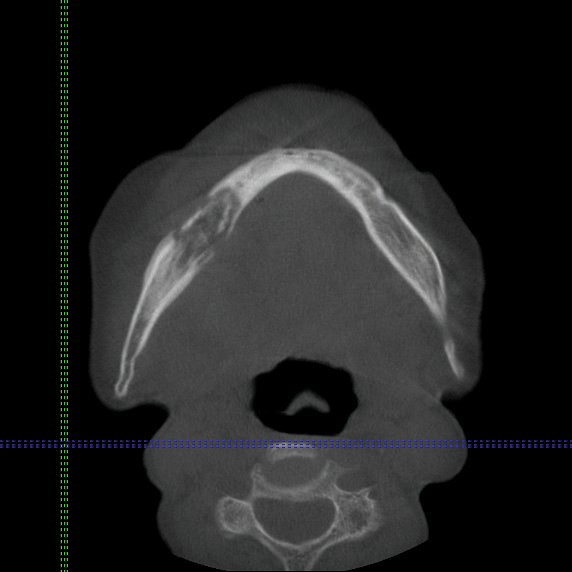

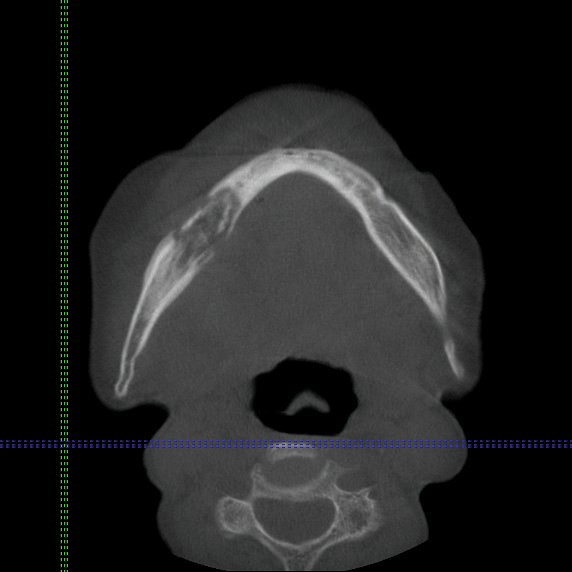

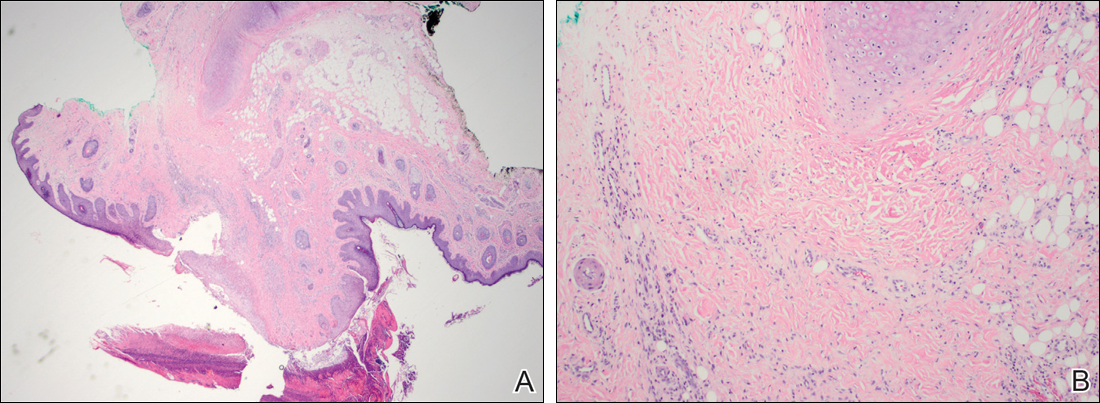

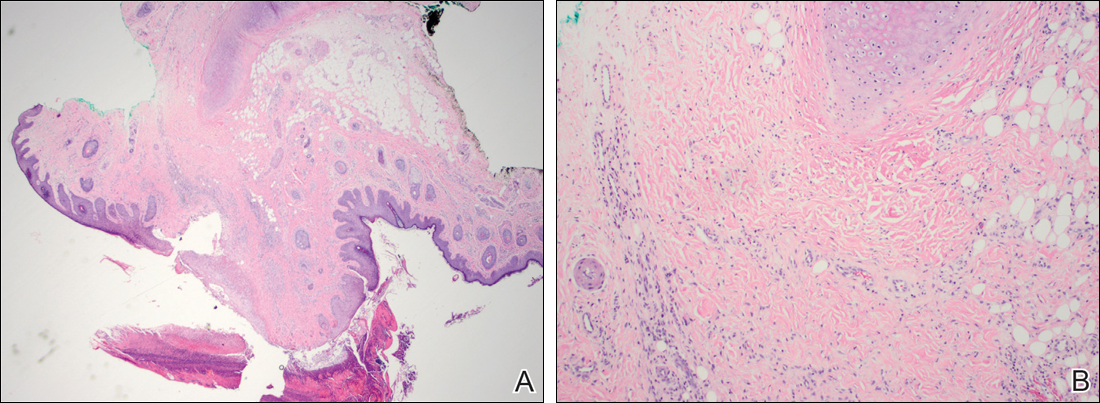

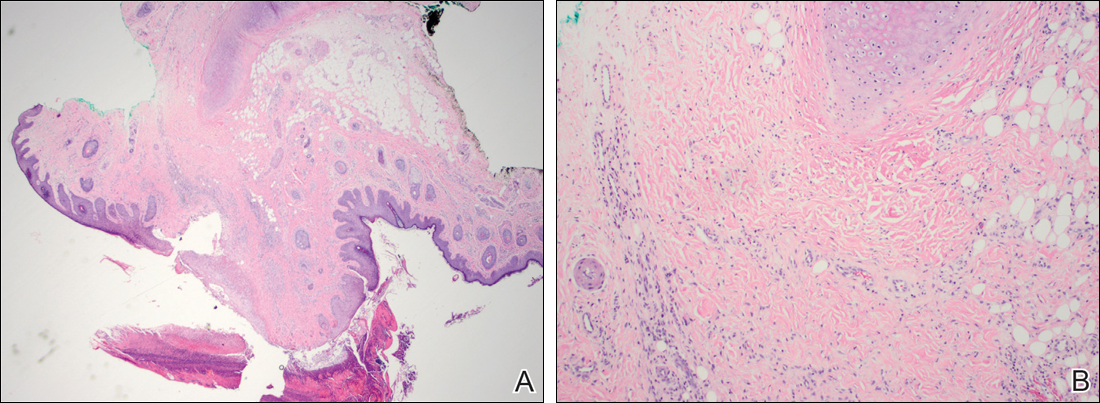

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

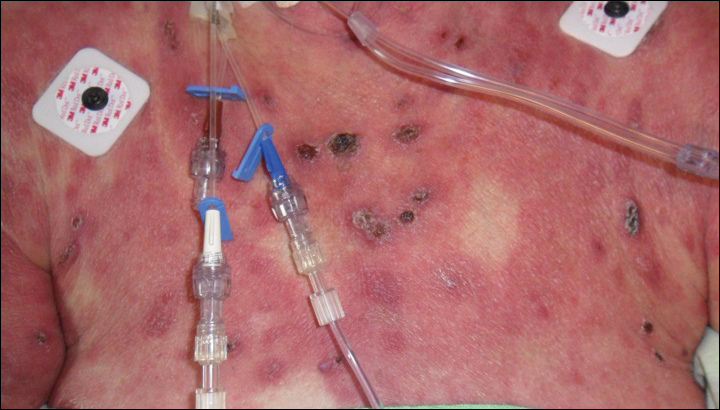

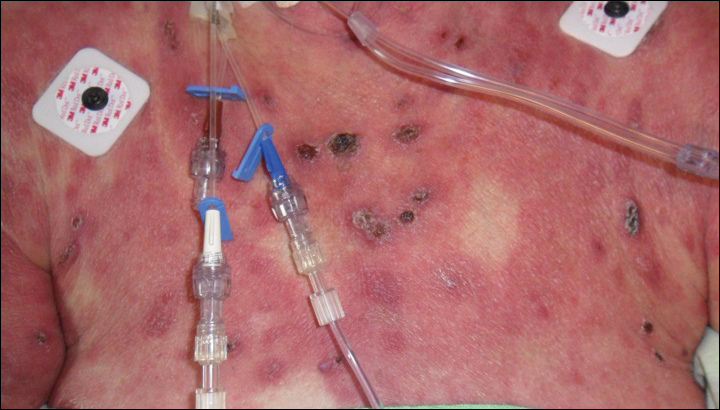

A 25-year-old Hispanic man with a history of juvenile idiopathic arthritis was admitted with a high-grade fever (temperature, >38.9°C) and diffuse nonlocalized abdominal pain of 2 days' duration. Physical examination revealed tachycardia, axillary lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cutaneous findings consisted of striking hyperpigmented patches on the chest and back, and hyperpigmented scaly lichenoid papules and plaques on the upper and lower extremities. The plaques on the lower extremities exhibited koebnerization. The patient reported that the eruption initially presented at 16 years of age as pruritic papules on the legs, which gradually spread to involve the arms, chest, and back. Prior treatments of juvenile idiopathic arthritis included prednisone, methotrexate, infliximab, and etanercept, though they were intermittent and temporary. Over time, the cutaneous eruption evolved into its current morphology and distribution, with periods of clearance observed while receiving systemic medications.

Bilateral Symmetric Onycholysis of Distal Fingernails

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

An allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to acrylates was suspected and 4 patches were applied to the forearm (the North American Standard Series of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group). The patches were 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 2.0% permissible exposure limit (peL), ethyl acrylate 0.1% peL, tosylamide formaldehyde resin 10.0% peL, and methyl methacrylate 2.0% peL. A reading at 72 hours was performed and showed a positive reaction to hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate, and a negative patch test to tosylamide formaldehyde resin (nail polish)(Figure). The patient was diagnosed with an allergic contact hypersensitivity to the aforementioned acrylates and instructed to avoid artificial nails and acrylate glues. She also was started on oral biotin supplements. On 6-month follow-up the patient had regrowth of all 10 fingernails without brittleness or splitting. She was able to use nail polishes but avoided all acrylic artificial nails and acrylate-containing personal care products.

Acrylate Allergy and Artificial Nails

Acrylates are plastic materials formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid monomers and have been cited as a major cause of occupational and nonoccupational contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to acrylates in artificial nails was first reported in the 1950s.1,2 Products containing 100% methyl methacrylate monomers in acrylic nails were banned by the US Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s after receiving a number of complaints.3 However, no regulation prohibits the use of methyl methacrylate monomer in cosmetic products, and various methacrylate and acrylate monomers remain widely used.4 With a growing popularity in artificial nails, it is expected the number of sensitized persons will increase.

Acrylate allergy from sculptured nails concern self-curing resins made from a polymer powder and a liquid monomer solution. Advantages of new UV-cured products include the lack of unpleasant smell and simplified modeling. They also do not require an irritant, such as methacrylic acid, as a bonding agent. Instead, 2-HEMA and 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate are added. These photobonded nails colloquially are called gel nails (acid free) as opposed to acrylic nails (using methacrylic acid as a primer). It is important to note that the esters of acrylic acid but not the acid itself sensitize patients, and sensitization is not caused by the uncured gel or the monomer solution but by the remaining monomers in the cured plastic nail and the dust filings that are produced during the finishing process.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of an ACD to nail acrylates include pruritus and fingertip dermatitis along with nail plate dystrophy. There may be pruritus at the nail base, with subsequent dryness, thickening, and onycholysis. The brittle nails may become split, discolored, and develop paronychia. Inadvertent contact with glue monomers or other acrylate-containing substances may cause eczematous lesions at distant sites. Avoidance of the allergen often results in complete restoration of the normal nail and fingertip within months.

Sensitization

Acrylates and methacrylates are ubiquitous materials used for both industrial and commercial applications. Due to their widespread industrial use, contact allergies to acrylates including 2-HEMA, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and triethyleneglycol diacrylate (TREGDA) are common. Cross-reaction of these compounds has been observed and is postulated to be due to reaction of the (meth)acrylate carboxyethyl group with the receptors of antigen-presenting cells.5 As a result, an individual with an acrylate allergy sensitized to one allergen often is allergic to its similar compounds and cross-reactors and must avoid the assortment of compounds containing these ingredients, which is important for individuals with occupational sensitization to a particular acrylate who is subsequently susceptible to other acrylate-containing compounds triggering allergic reactions when reexposure occurs in different settings.

Allergens and Occupational Exposure

Acrylates in cosmetic nail products are a source of ACD for not only the customer but also the manicurist.6 The most frequently cited sources of ACD in beauticians are acrylate chemicals.7 However, acrylate compounds are an occupational hazard for a number of other specialists, including dentists and dental technicians, histology technicians, and individuals in the printing industry.8,9 Other individuals may be sensitized to acrylates through their inclusion in adhesives, dental bonding agents, hearing aids, electrocardiogram electrodes, artificial bone cement, and a myriad of other medical and nonmedical applications.4,10-12 For workers who cannot avoid occupational exposure to these allergens, polyvinyl alcohol and multilayer laminate gloves are recommended, as natural rubber latex gloves do not always provide adequate protection from many of these agents.10

Testing for Suspected Acrylate Allergy

Cross-reactivity among acrylates is widely considered in the literature but remains enigmatic and is an important consideration with regard to routine patch test screening.13 In the case of an acrylate allergy to nail products, using 2-HEMA and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate is effective in detecting sensitization by photobonded nails and in patients sensitized by powder liquid products.14 One study showed a patch test panel including 2-HEMA, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and TREGDA was effective in identifying the majority of individuals with an allergy to acrylates in nail products and nail technicians.15 Another study has shown the most commonly positive testing allergens to be HEMA, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate.16 If one is patch testing only one chemical, it appears 2-HEMA is preferred.17 However, broader panels of screening allergens are necessary to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, different panels of test allergens have been shown to vary in their ability to detect an acrylate allergy in different occupational exposures.12

The time to patch test read also is important. A standard read at 72 hours is warranted; however, one study showed if only one read at day 3 was done without a subsequent day 7 read, then 25% of TREGDA and 50% of 2-HEMA allergies would have been missed in patients with occupational acrylate allergy.15 Other studies have reported late-appearing and long-lasting test reactions when testing for an acrylate allergy.18,19 Clinicians should be cognizant that an acrylate allergy may be present even if initial screening is negative but the history and clinical picture are suggestive.

- Canizares O. Contact dermatitis due to the acrylic materials used in artificial nails. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:141-143.

- Fisher AA, Franks A, Glick H. Allergic sensitization of the skin and nails to acrylic plastic nails. J Allergy. 1957;28:84-88.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Nail care products. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients/Products/ucm127068.htm. Updated October 26, 2016. Accessed December 27, 2016.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S123-S124.

- Kanerva L. Cross-reactions of multifunctional methacrylates and acrylates. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:320-329.

- Tammaro A, Narcisi A, Abruzzese C, et al. Fingertip dermatitis: occupational acrylate cross reaction. Allergol Int. 2014;63:609-610.

- Kwok C, Money A, Carder M, et al. Cases of occupational dermatitis and asthma in beauticians that were reported to The Health and Occupation Research (THOR) network from 1996 to 2011. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:590-595.

- Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:324-330.

- Molina L, Amado A, Mattei PL 4th, et al. Contact dermatitis from acrylics in a histology laboratory assistant. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E11-E12.

- Prasad Hunasehally RY, Hughes TM, Stone NM. Atypical pattern of (meth)acrylate allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals. Br Dent J. 2012;213:223-224.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes [published online January 27, 2015]. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23:6-16.

- Fisher AA. Cross reactions between methyl methacrylate monomer and acrylic monomers presently used in acrylic nail preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 1980;6:345-347.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Wantke F, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to artificial fingernails prepared from UV light-cured acrylates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):377-380.

- Teik-Jin Goon A, Bruze M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates/methacrylates in the acrylate and nail acrylics series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:21-27.

- Drucker AM, Pratt MD. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis. 2011;22:98-101.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Goncalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates--a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Goon AT, Isaksson M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylates in the dental series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:219-226.

- Isaksson M, Lindberg M, Sundberg K, et al. The development and course of patch-test reactions to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethyleneglycol dimethacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:292-297.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

An allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to acrylates was suspected and 4 patches were applied to the forearm (the North American Standard Series of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group). The patches were 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 2.0% permissible exposure limit (peL), ethyl acrylate 0.1% peL, tosylamide formaldehyde resin 10.0% peL, and methyl methacrylate 2.0% peL. A reading at 72 hours was performed and showed a positive reaction to hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate, and a negative patch test to tosylamide formaldehyde resin (nail polish)(Figure). The patient was diagnosed with an allergic contact hypersensitivity to the aforementioned acrylates and instructed to avoid artificial nails and acrylate glues. She also was started on oral biotin supplements. On 6-month follow-up the patient had regrowth of all 10 fingernails without brittleness or splitting. She was able to use nail polishes but avoided all acrylic artificial nails and acrylate-containing personal care products.

Acrylate Allergy and Artificial Nails

Acrylates are plastic materials formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid monomers and have been cited as a major cause of occupational and nonoccupational contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to acrylates in artificial nails was first reported in the 1950s.1,2 Products containing 100% methyl methacrylate monomers in acrylic nails were banned by the US Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s after receiving a number of complaints.3 However, no regulation prohibits the use of methyl methacrylate monomer in cosmetic products, and various methacrylate and acrylate monomers remain widely used.4 With a growing popularity in artificial nails, it is expected the number of sensitized persons will increase.

Acrylate allergy from sculptured nails concern self-curing resins made from a polymer powder and a liquid monomer solution. Advantages of new UV-cured products include the lack of unpleasant smell and simplified modeling. They also do not require an irritant, such as methacrylic acid, as a bonding agent. Instead, 2-HEMA and 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate are added. These photobonded nails colloquially are called gel nails (acid free) as opposed to acrylic nails (using methacrylic acid as a primer). It is important to note that the esters of acrylic acid but not the acid itself sensitize patients, and sensitization is not caused by the uncured gel or the monomer solution but by the remaining monomers in the cured plastic nail and the dust filings that are produced during the finishing process.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of an ACD to nail acrylates include pruritus and fingertip dermatitis along with nail plate dystrophy. There may be pruritus at the nail base, with subsequent dryness, thickening, and onycholysis. The brittle nails may become split, discolored, and develop paronychia. Inadvertent contact with glue monomers or other acrylate-containing substances may cause eczematous lesions at distant sites. Avoidance of the allergen often results in complete restoration of the normal nail and fingertip within months.

Sensitization

Acrylates and methacrylates are ubiquitous materials used for both industrial and commercial applications. Due to their widespread industrial use, contact allergies to acrylates including 2-HEMA, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and triethyleneglycol diacrylate (TREGDA) are common. Cross-reaction of these compounds has been observed and is postulated to be due to reaction of the (meth)acrylate carboxyethyl group with the receptors of antigen-presenting cells.5 As a result, an individual with an acrylate allergy sensitized to one allergen often is allergic to its similar compounds and cross-reactors and must avoid the assortment of compounds containing these ingredients, which is important for individuals with occupational sensitization to a particular acrylate who is subsequently susceptible to other acrylate-containing compounds triggering allergic reactions when reexposure occurs in different settings.

Allergens and Occupational Exposure

Acrylates in cosmetic nail products are a source of ACD for not only the customer but also the manicurist.6 The most frequently cited sources of ACD in beauticians are acrylate chemicals.7 However, acrylate compounds are an occupational hazard for a number of other specialists, including dentists and dental technicians, histology technicians, and individuals in the printing industry.8,9 Other individuals may be sensitized to acrylates through their inclusion in adhesives, dental bonding agents, hearing aids, electrocardiogram electrodes, artificial bone cement, and a myriad of other medical and nonmedical applications.4,10-12 For workers who cannot avoid occupational exposure to these allergens, polyvinyl alcohol and multilayer laminate gloves are recommended, as natural rubber latex gloves do not always provide adequate protection from many of these agents.10

Testing for Suspected Acrylate Allergy

Cross-reactivity among acrylates is widely considered in the literature but remains enigmatic and is an important consideration with regard to routine patch test screening.13 In the case of an acrylate allergy to nail products, using 2-HEMA and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate is effective in detecting sensitization by photobonded nails and in patients sensitized by powder liquid products.14 One study showed a patch test panel including 2-HEMA, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and TREGDA was effective in identifying the majority of individuals with an allergy to acrylates in nail products and nail technicians.15 Another study has shown the most commonly positive testing allergens to be HEMA, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate.16 If one is patch testing only one chemical, it appears 2-HEMA is preferred.17 However, broader panels of screening allergens are necessary to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, different panels of test allergens have been shown to vary in their ability to detect an acrylate allergy in different occupational exposures.12

The time to patch test read also is important. A standard read at 72 hours is warranted; however, one study showed if only one read at day 3 was done without a subsequent day 7 read, then 25% of TREGDA and 50% of 2-HEMA allergies would have been missed in patients with occupational acrylate allergy.15 Other studies have reported late-appearing and long-lasting test reactions when testing for an acrylate allergy.18,19 Clinicians should be cognizant that an acrylate allergy may be present even if initial screening is negative but the history and clinical picture are suggestive.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

An allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to acrylates was suspected and 4 patches were applied to the forearm (the North American Standard Series of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group). The patches were 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 2.0% permissible exposure limit (peL), ethyl acrylate 0.1% peL, tosylamide formaldehyde resin 10.0% peL, and methyl methacrylate 2.0% peL. A reading at 72 hours was performed and showed a positive reaction to hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate, and a negative patch test to tosylamide formaldehyde resin (nail polish)(Figure). The patient was diagnosed with an allergic contact hypersensitivity to the aforementioned acrylates and instructed to avoid artificial nails and acrylate glues. She also was started on oral biotin supplements. On 6-month follow-up the patient had regrowth of all 10 fingernails without brittleness or splitting. She was able to use nail polishes but avoided all acrylic artificial nails and acrylate-containing personal care products.

Acrylate Allergy and Artificial Nails

Acrylates are plastic materials formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid monomers and have been cited as a major cause of occupational and nonoccupational contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to acrylates in artificial nails was first reported in the 1950s.1,2 Products containing 100% methyl methacrylate monomers in acrylic nails were banned by the US Food and Drug Administration in the early 1970s after receiving a number of complaints.3 However, no regulation prohibits the use of methyl methacrylate monomer in cosmetic products, and various methacrylate and acrylate monomers remain widely used.4 With a growing popularity in artificial nails, it is expected the number of sensitized persons will increase.

Acrylate allergy from sculptured nails concern self-curing resins made from a polymer powder and a liquid monomer solution. Advantages of new UV-cured products include the lack of unpleasant smell and simplified modeling. They also do not require an irritant, such as methacrylic acid, as a bonding agent. Instead, 2-HEMA and 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate are added. These photobonded nails colloquially are called gel nails (acid free) as opposed to acrylic nails (using methacrylic acid as a primer). It is important to note that the esters of acrylic acid but not the acid itself sensitize patients, and sensitization is not caused by the uncured gel or the monomer solution but by the remaining monomers in the cured plastic nail and the dust filings that are produced during the finishing process.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of an ACD to nail acrylates include pruritus and fingertip dermatitis along with nail plate dystrophy. There may be pruritus at the nail base, with subsequent dryness, thickening, and onycholysis. The brittle nails may become split, discolored, and develop paronychia. Inadvertent contact with glue monomers or other acrylate-containing substances may cause eczematous lesions at distant sites. Avoidance of the allergen often results in complete restoration of the normal nail and fingertip within months.

Sensitization

Acrylates and methacrylates are ubiquitous materials used for both industrial and commercial applications. Due to their widespread industrial use, contact allergies to acrylates including 2-HEMA, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and triethyleneglycol diacrylate (TREGDA) are common. Cross-reaction of these compounds has been observed and is postulated to be due to reaction of the (meth)acrylate carboxyethyl group with the receptors of antigen-presenting cells.5 As a result, an individual with an acrylate allergy sensitized to one allergen often is allergic to its similar compounds and cross-reactors and must avoid the assortment of compounds containing these ingredients, which is important for individuals with occupational sensitization to a particular acrylate who is subsequently susceptible to other acrylate-containing compounds triggering allergic reactions when reexposure occurs in different settings.

Allergens and Occupational Exposure

Acrylates in cosmetic nail products are a source of ACD for not only the customer but also the manicurist.6 The most frequently cited sources of ACD in beauticians are acrylate chemicals.7 However, acrylate compounds are an occupational hazard for a number of other specialists, including dentists and dental technicians, histology technicians, and individuals in the printing industry.8,9 Other individuals may be sensitized to acrylates through their inclusion in adhesives, dental bonding agents, hearing aids, electrocardiogram electrodes, artificial bone cement, and a myriad of other medical and nonmedical applications.4,10-12 For workers who cannot avoid occupational exposure to these allergens, polyvinyl alcohol and multilayer laminate gloves are recommended, as natural rubber latex gloves do not always provide adequate protection from many of these agents.10

Testing for Suspected Acrylate Allergy

Cross-reactivity among acrylates is widely considered in the literature but remains enigmatic and is an important consideration with regard to routine patch test screening.13 In the case of an acrylate allergy to nail products, using 2-HEMA and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate is effective in detecting sensitization by photobonded nails and in patients sensitized by powder liquid products.14 One study showed a patch test panel including 2-HEMA, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and TREGDA was effective in identifying the majority of individuals with an allergy to acrylates in nail products and nail technicians.15 Another study has shown the most commonly positive testing allergens to be HEMA, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate.16 If one is patch testing only one chemical, it appears 2-HEMA is preferred.17 However, broader panels of screening allergens are necessary to achieve an accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, different panels of test allergens have been shown to vary in their ability to detect an acrylate allergy in different occupational exposures.12

The time to patch test read also is important. A standard read at 72 hours is warranted; however, one study showed if only one read at day 3 was done without a subsequent day 7 read, then 25% of TREGDA and 50% of 2-HEMA allergies would have been missed in patients with occupational acrylate allergy.15 Other studies have reported late-appearing and long-lasting test reactions when testing for an acrylate allergy.18,19 Clinicians should be cognizant that an acrylate allergy may be present even if initial screening is negative but the history and clinical picture are suggestive.

- Canizares O. Contact dermatitis due to the acrylic materials used in artificial nails. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:141-143.

- Fisher AA, Franks A, Glick H. Allergic sensitization of the skin and nails to acrylic plastic nails. J Allergy. 1957;28:84-88.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Nail care products. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients/Products/ucm127068.htm. Updated October 26, 2016. Accessed December 27, 2016.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S123-S124.

- Kanerva L. Cross-reactions of multifunctional methacrylates and acrylates. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:320-329.

- Tammaro A, Narcisi A, Abruzzese C, et al. Fingertip dermatitis: occupational acrylate cross reaction. Allergol Int. 2014;63:609-610.

- Kwok C, Money A, Carder M, et al. Cases of occupational dermatitis and asthma in beauticians that were reported to The Health and Occupation Research (THOR) network from 1996 to 2011. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:590-595.

- Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:324-330.

- Molina L, Amado A, Mattei PL 4th, et al. Contact dermatitis from acrylics in a histology laboratory assistant. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E11-E12.

- Prasad Hunasehally RY, Hughes TM, Stone NM. Atypical pattern of (meth)acrylate allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals. Br Dent J. 2012;213:223-224.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes [published online January 27, 2015]. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23:6-16.

- Fisher AA. Cross reactions between methyl methacrylate monomer and acrylic monomers presently used in acrylic nail preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 1980;6:345-347.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Wantke F, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to artificial fingernails prepared from UV light-cured acrylates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):377-380.

- Teik-Jin Goon A, Bruze M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates/methacrylates in the acrylate and nail acrylics series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:21-27.

- Drucker AM, Pratt MD. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis. 2011;22:98-101.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Goncalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates--a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Goon AT, Isaksson M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylates in the dental series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:219-226.

- Isaksson M, Lindberg M, Sundberg K, et al. The development and course of patch-test reactions to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethyleneglycol dimethacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:292-297.

- Canizares O. Contact dermatitis due to the acrylic materials used in artificial nails. AMA Arch Derm. 1956;74:141-143.

- Fisher AA, Franks A, Glick H. Allergic sensitization of the skin and nails to acrylic plastic nails. J Allergy. 1957;28:84-88.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Nail care products. http://www.fda.gov/Cosmetics/ProductsIngredients/Products/ucm127068.htm. Updated October 26, 2016. Accessed December 27, 2016.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S123-S124.

- Kanerva L. Cross-reactions of multifunctional methacrylates and acrylates. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:320-329.

- Tammaro A, Narcisi A, Abruzzese C, et al. Fingertip dermatitis: occupational acrylate cross reaction. Allergol Int. 2014;63:609-610.

- Kwok C, Money A, Carder M, et al. Cases of occupational dermatitis and asthma in beauticians that were reported to The Health and Occupation Research (THOR) network from 1996 to 2011. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:590-595.

- Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:324-330.

- Molina L, Amado A, Mattei PL 4th, et al. Contact dermatitis from acrylics in a histology laboratory assistant. Dermatitis. 2009;20:E11-E12.

- Prasad Hunasehally RY, Hughes TM, Stone NM. Atypical pattern of (meth)acrylate allergic contact dermatitis in dental professionals. Br Dent J. 2012;213:223-224.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes [published online January 27, 2015]. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23:6-16.

- Fisher AA. Cross reactions between methyl methacrylate monomer and acrylic monomers presently used in acrylic nail preparations. Contact Dermatitis. 1980;6:345-347.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Wantke F, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to artificial fingernails prepared from UV light-cured acrylates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(3, pt 1):377-380.

- Teik-Jin Goon A, Bruze M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates/methacrylates in the acrylate and nail acrylics series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:21-27.

- Drucker AM, Pratt MD. Acrylate contact allergy: patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis. 2011;22:98-101.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Goncalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates--a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Goon AT, Isaksson M, Zimerson E, et al. Contact allergy to (meth)acrylates in the dental series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:219-226.

- Isaksson M, Lindberg M, Sundberg K, et al. The development and course of patch-test reactions to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethyleneglycol dimethacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:292-297.

A 28-year-old woman presented with distal onycholysis of all 10 fingernails. The patient started to notice brittleness in the first, second, and third fingernails of the right hand 2 months prior. She had a 10-year history of wearing acrylic nails and reported a history of periungual eczema. On physical examination, all 10 fingernails had distal onycholysis and there was a green discoloration of the first fingernail on the left hand. On blood analysis, thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine were within reference range. A nail clipping showed onychodystrophy and a negative periodic acid-Schiff stain.

Painful Oral and Genital Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

A 52-year-old man presented with persistent painful oral ulcers and penile and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. He strongly denied engaging in high-risk sexual activities and had lost 10 kg over the last 6 months. He did not report taking any over-the-counter or alternative medications. On physical examination there were multiple fissures on the lower lip with erosive white plaques on the tongue and buccal mucosa. There were erosions over the foreskin and glans penis and a few erosive plaques on the perianal skin. Bilateral inguinal lymph nodes were enlarged.

Superficial Ulceration on the Vulva

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

A 23-year-old woman who was immunosuppressed secondary to cyclophosphamide and prednisolone treatment of autoimmune panniculitis was admitted to intensive care with dyspnea. Cytomegalovirus and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia were diagnosed on bronchoscopy and bronchial washings. Management with valganciclovir was started but worsened the patient's pancytopenia. She was started on intravenous foscarnet. After a week of therapy, the patient reported vulval soreness and painful micturition. On examination there was superficial ulceration of the labia minora. The affected area was symmetrical, and there was some extension into the vestibule. There were no vesicles or lesions on the cutaneous skin.

Purple Curvilinear Papules on the Back

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Graft-vs-host Disease

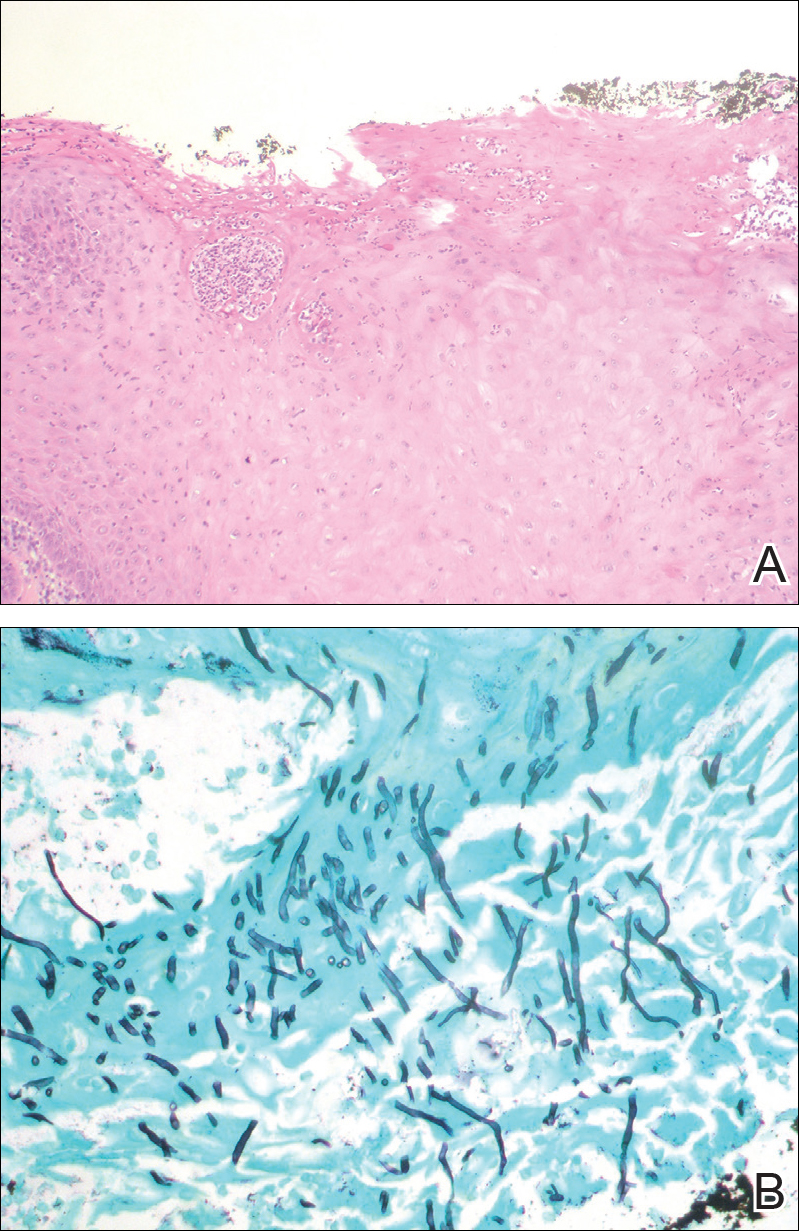

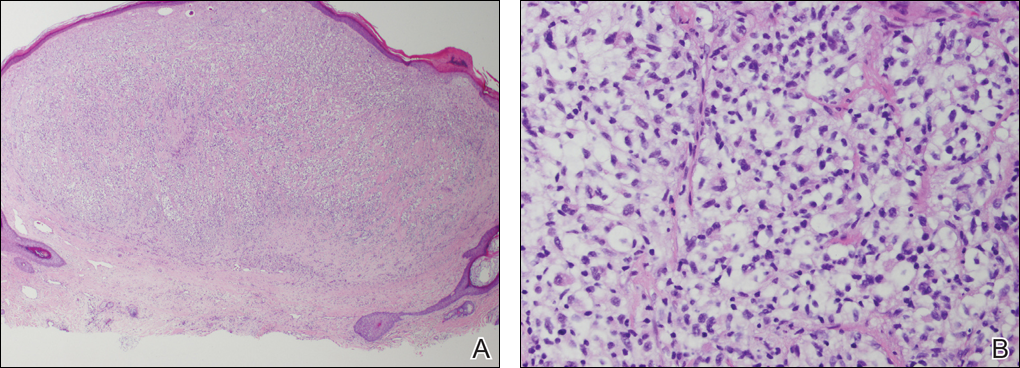

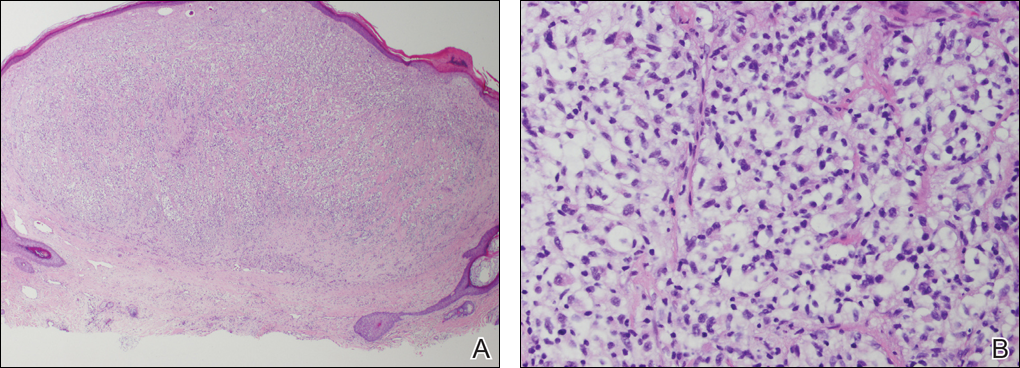

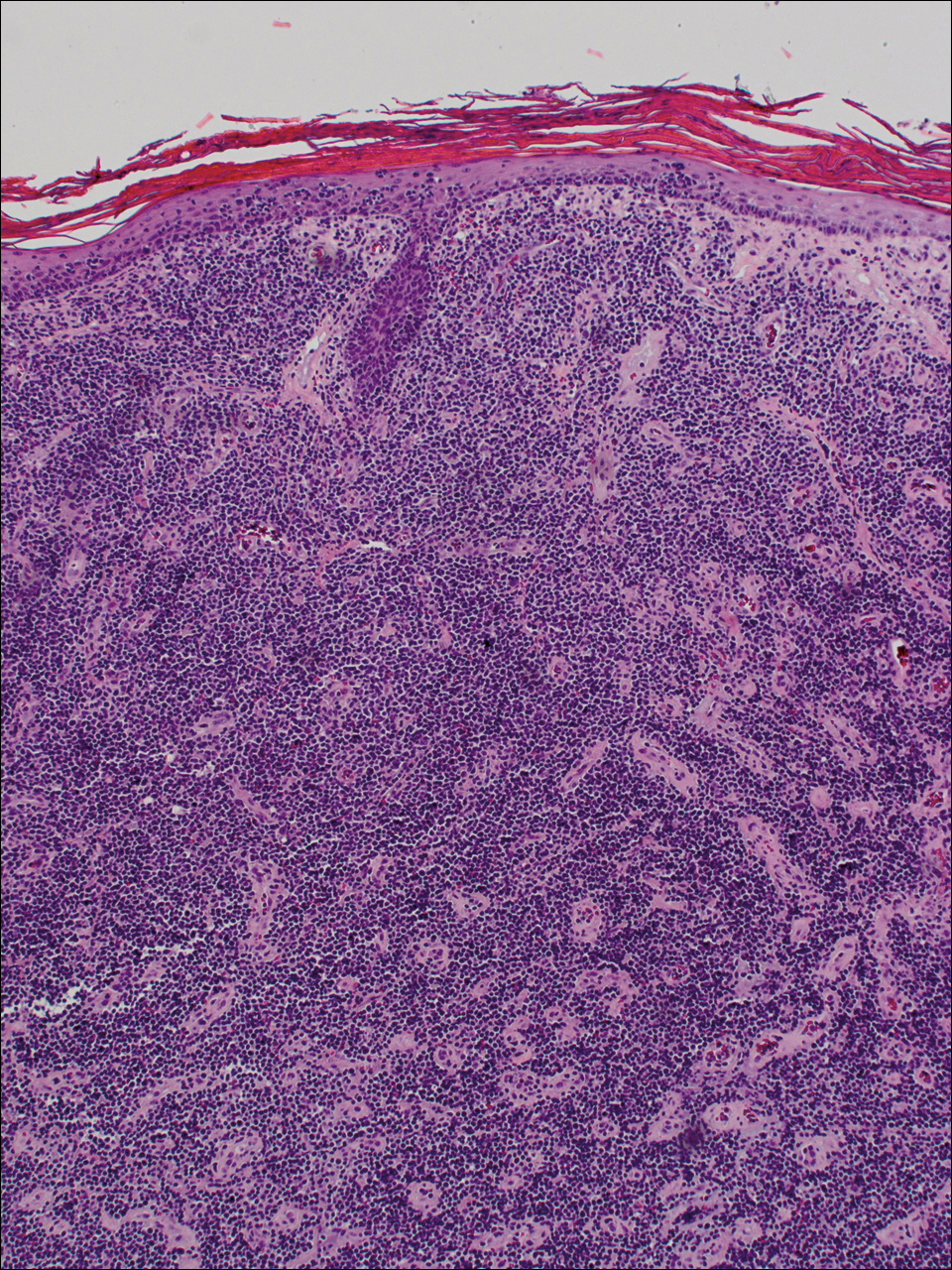

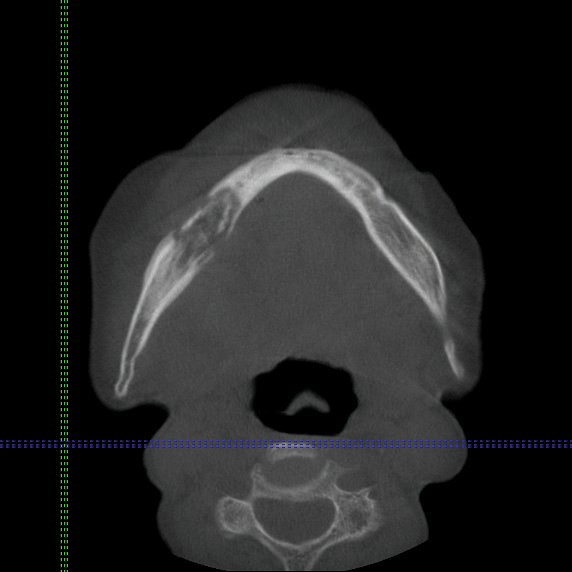

The patient had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and underwent a bone marrow transplant 1 year prior to presentation. She had acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) 6 weeks following the transplant, which resolved with high-dose prednisone followed by UVB phototherapy. Skin biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration, dyskeratosis, and prominent pigment incontinence (Figure). Based on these findings and her clinical presentation, a diagnosis of blaschkoid GVHD was made.

Although acute GVHD is the result of immunocompetent donor T cells recognizing host tissues as foreign and initiating an immune response, the pathophysiology of chronic GVHD is not well understood.1,2 Theories for disease pathogenesis in chronic GVHD suggest an underlying autoimmune and/or alloreactive process.2-5 The skin often is the first organ affected in acute GVHD, and patients generally present with a pruritic morbilliform eruption that begins on the trunk and spreads to the rest of the body.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD may be protean. Lesions can resemble systemic sclerosis or morphea, lichen planus, psoriasis, ichthyosis, and many other conditions.2

The differential diagnosis of linear dermatoses includes herpes zoster, contact dermatitis, lichen striatus (blaschkitis), nevus unius lateris, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and incontinentia pigmenti.6,7 Lichen planus-like chronic GVHD occurring in a linear distribution has been described.6-14 Distinction between dermatomal and blaschkoid processes is diagnostically important. In the case of GVHD, dermatomal distribution may suggest an association between GVHD and prior herpes simplex virus or varicella-zoster virus infection.6,8 Herpesvirus may alter surface antigens of keratinocytes, rendering them targets of donor lymphocytes, and antibodies to viral particles may cross-react with host keratinocyte HLA antigens. It also is possible that dermatomal GVHD may simply be a type of isomorphic response (Köbner phenomenon).8

When cutaneous GVHD follows Blaschko lines, other mechanisms appear to be at play.9-14 It is plausible that these patients have an underlying genetic mosaicism, perhaps the result of a postzygotic mutation, that results in a daughter cell population that expresses surface antigens different from those of the primary cell population found elsewhere in the skin. Donor lymphocytes may selectively react to this mosaic population, leading to the clinical picture of chronic GVHD oriented along Blaschko lines.10,11,13,14

In conclusion, lichenoid linear GVHD following Blaschko lines is an uncommon presentation of chronic GVHD that highlights the heterogeneity of this disease and should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, et al. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550-1561.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-515.e18; quiz 533-534.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

- Shimada M, Onizuka M, Machida S, et al. Association of autoimmune disease-related gene polymorphisms with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:458-463.

- Zhang C, Todorov I, Zhang Z, et al. Donor CD4+ T and B cells in transplants induce chronic graft-versus-host disease with autoimmune manifestations. Blood. 2006;107:2993-3001.

- Freemer CS, Farmer ER, Corio RL, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease occurring in a dermatomal distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:70-72.

- Kikuchi A, Okamoto S, Takahashi S, et al. Linear chronic cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:1004-1006.

- Sanli H, Anadolu R, Arat M, et al. Dermatomal lichenoid graft-versus-host disease within herpes zoster scars. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:562-564.

- Kennedy FE, Hilari H, Ferrer B, et al. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease following Blaschko lines. ActasDermosifiliogr. 2014;105:89-92.

- Lee SW, Kim YC, Lee E, et al. Linear lichenoid graft versus host disease: an unusual configuration following Blaschko's lines. J Dermatol. 2006;33:583-584.

- Beers B, Kalish RS, Kaye VN, et al. Unilateral linear lichenoid eruption after bone marrow transplantation: an unmasking of tolerance to an abnormal keratinocyte clone? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):888-892.

- Wilson B, Lockman D. Linear lichenoid graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(9):1206-1208.

- Reisfeld PL. Lichenoid chronic graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1207-1208.

- Vassallo C, Derlino F, Ripamonti F, et al. Lichenoid cutaneous chronic GvHD following Blaschko lines. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:473-475.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Graft-vs-host Disease

The patient had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and underwent a bone marrow transplant 1 year prior to presentation. She had acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) 6 weeks following the transplant, which resolved with high-dose prednisone followed by UVB phototherapy. Skin biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration, dyskeratosis, and prominent pigment incontinence (Figure). Based on these findings and her clinical presentation, a diagnosis of blaschkoid GVHD was made.

Although acute GVHD is the result of immunocompetent donor T cells recognizing host tissues as foreign and initiating an immune response, the pathophysiology of chronic GVHD is not well understood.1,2 Theories for disease pathogenesis in chronic GVHD suggest an underlying autoimmune and/or alloreactive process.2-5 The skin often is the first organ affected in acute GVHD, and patients generally present with a pruritic morbilliform eruption that begins on the trunk and spreads to the rest of the body.1,2 Cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD may be protean. Lesions can resemble systemic sclerosis or morphea, lichen planus, psoriasis, ichthyosis, and many other conditions.2

The differential diagnosis of linear dermatoses includes herpes zoster, contact dermatitis, lichen striatus (blaschkitis), nevus unius lateris, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and incontinentia pigmenti.6,7 Lichen planus-like chronic GVHD occurring in a linear distribution has been described.6-14 Distinction between dermatomal and blaschkoid processes is diagnostically important. In the case of GVHD, dermatomal distribution may suggest an association between GVHD and prior herpes simplex virus or varicella-zoster virus infection.6,8 Herpesvirus may alter surface antigens of keratinocytes, rendering them targets of donor lymphocytes, and antibodies to viral particles may cross-react with host keratinocyte HLA antigens. It also is possible that dermatomal GVHD may simply be a type of isomorphic response (Köbner phenomenon).8

When cutaneous GVHD follows Blaschko lines, other mechanisms appear to be at play.9-14 It is plausible that these patients have an underlying genetic mosaicism, perhaps the result of a postzygotic mutation, that results in a daughter cell population that expresses surface antigens different from those of the primary cell population found elsewhere in the skin. Donor lymphocytes may selectively react to this mosaic population, leading to the clinical picture of chronic GVHD oriented along Blaschko lines.10,11,13,14

In conclusion, lichenoid linear GVHD following Blaschko lines is an uncommon presentation of chronic GVHD that highlights the heterogeneity of this disease and should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Graft-vs-host Disease

The patient had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and underwent a bone marrow transplant 1 year prior to presentation. She had acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) 6 weeks following the transplant, which resolved with high-dose prednisone followed by UVB phototherapy. Skin biopsy demonstrated lichenoid dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration, dyskeratosis, and prominent pigment incontinence (Figure). Based on these findings and her clinical presentation, a diagnosis of blaschkoid GVHD was made.