User login

Crusted Plaque in the Umbilicus

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

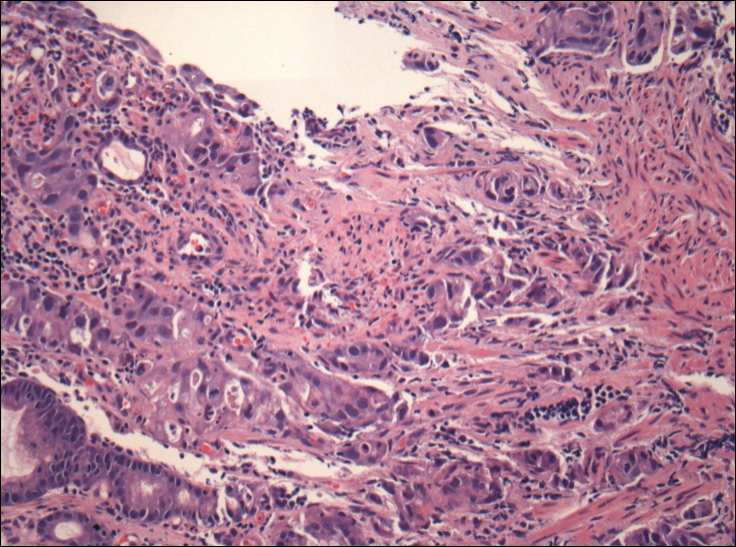

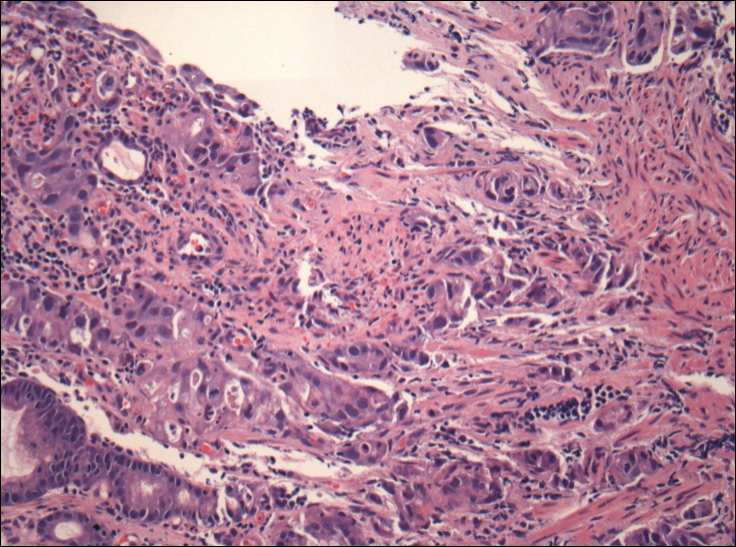

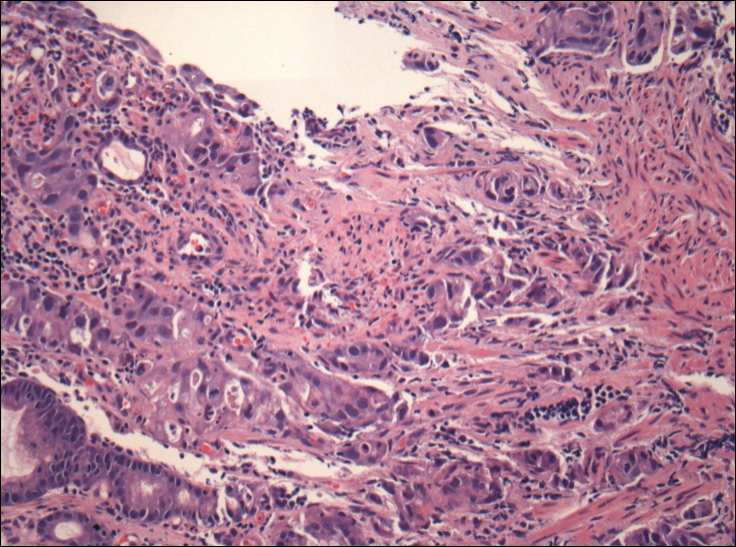

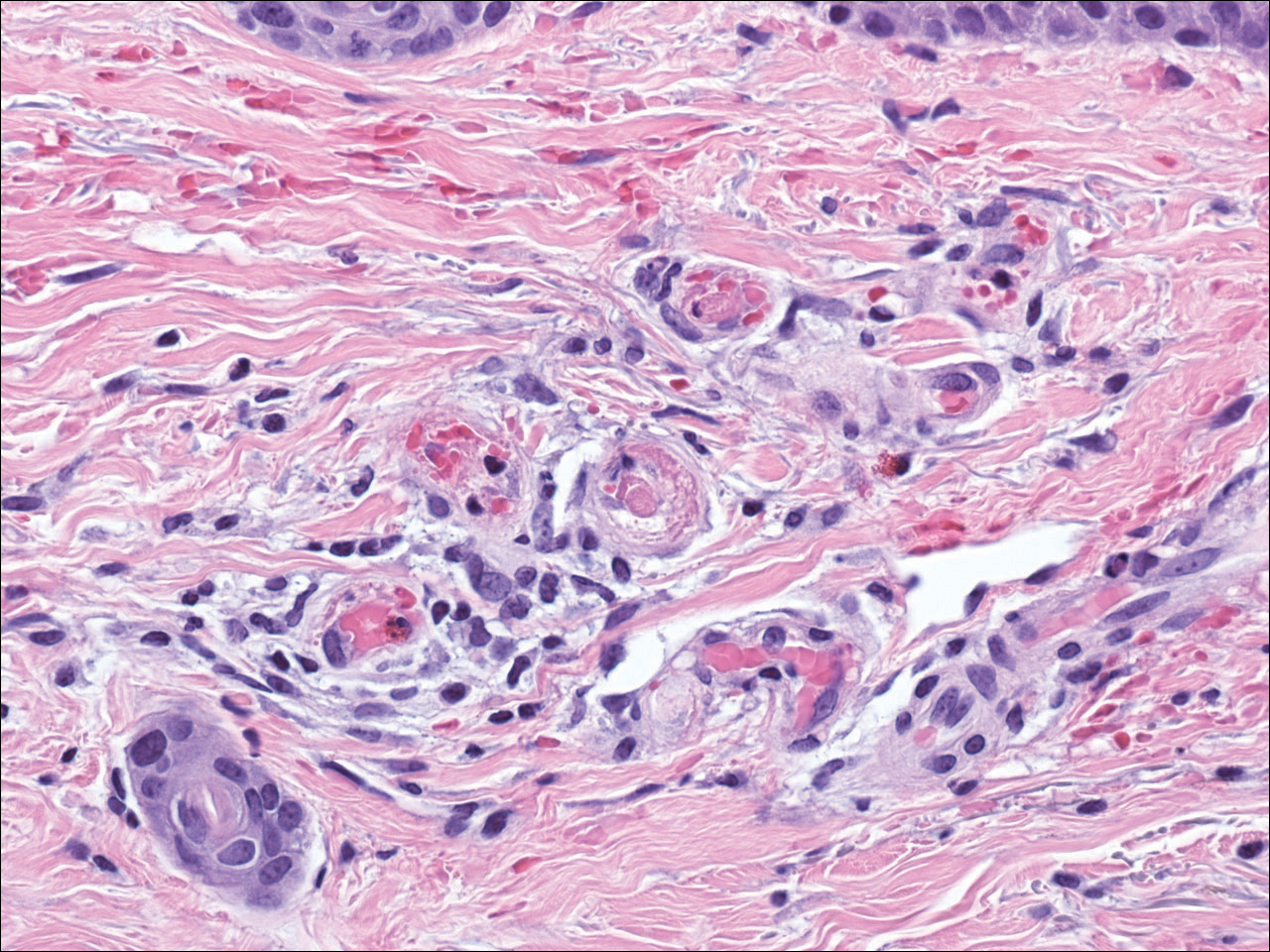

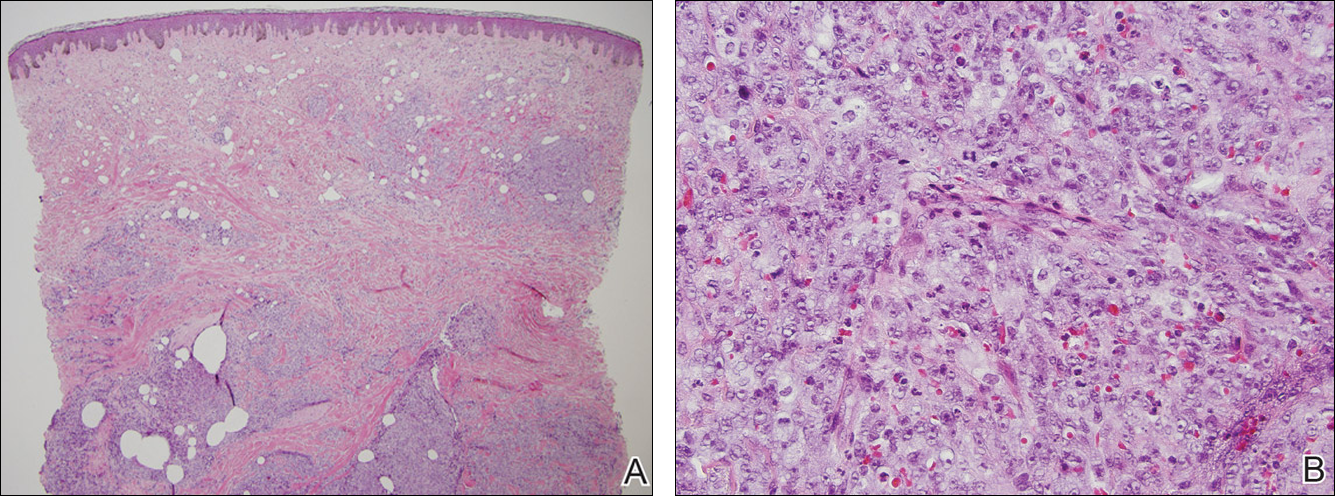

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

The umbilical skin biopsy revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure) that was positive for cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 and negative for cytokeratin 7 and transcription termination factor 1. The patient subsequently underwent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, which showed multiple soft-tissue nodules on the greater omentum, a soft-tissue density at the umbilicus, and thickening of the gastric mucosa. An upper endoscopy was then performed, which revealed a large fungating ulcerated mass in the stomach. Biopsy of this mass showed an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, which was ERBB2 (formerly HER2) negative. Histopathologically, these pleomorphic glands looked similar to the glands seen in the original skin biopsy. With this diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, our patient chose palliative chemotherapy but declined precipitously and died 2 months after the initial skin biopsy of the umbilical lesion.

When encountering a patient with an umbilical lesion, it is important to consider benign and malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis. A benign lesion may include scar, cyst, pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, polyp, abscess, or the presence of an omphalith.1 Inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis or eczema also should be considered. Malignant lesions could be either primary or secondary, with metastatic disease being the most common.2 Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is the eponymgiven to an umbilical lesion representing metastatic disease. Sister Mary Joseph was a nurse and surgical assistant to Dr. William Mayo in Rochester, Minnesota, in what is now known as the Mayo Clinic. She is credited to be the first to observe and note the association between an umbilical nodule and intra-abdominal malignancy. Metastasis to the umbilicus is thought to occur by way of contiguous, hematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread through embryologic remnants from primary cancers of nearby gastrointestinal or pelvic viscera. It is a rare cutaneous sign of internal malignancy, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%.3 The most common primary cancer is gastric adenocarcinoma, though cases of metastasis from pancreatic, endometrial, and less commonly hematopoietic or supradiaphragmatic cancers have been reported.4 It is more common in women, likely due to the addition of gynecologic malignancies.1

The use of dermoscopy has been advocated as an adjuvant tool in delineating benign and malignant umbilical lesions when an atypical polymorphous vascular pattern indicating neovascularization has been observed with neoplastic growth.5 Once a suspicious umbilical lesion is identified, the first step should be to obtain a skin biopsy or to use fine needle aspiration for cytology.6 Biopsy is especially relevant in the background of cancer history because SMJN may present with cancer recurrence.3 Once one of these is obtained, histological and immunohistochemical analysis will guide further workup and diagnosis of the umbilical lesion.

The importance of reviewing such cases lies in the variable presentation of cutaneous metastases such as SMJN and the grim prognosis that accompanies this finding. It presents as a firm indurated plaque or nodule that may present with systemic symptoms suggestive of malignancy, though in 30% of cases it is the sole initial sign.7 The nodule may be painful if ulcerated or fissured. Bloody, serous, or purulent discharge may be present. After diagnosis of an SMJN, most patients succumb to the disease within 12 months. Thus, it is vital for dermatologists to investigate umbilical lesions with great caution and a high index of suspicion.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule at a University teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Papalas JA, Selim MA. Metastatic vs primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus: clinicopathologic features of 77 tumors. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:237-242.

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:78-81.

- Zhang YL, Selvaggi SM. Metastatic islet cell carcinoma to the umbilicus: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:91-94.

- Mun JH, Kim JM, Ko HC, et al. Dermoscopy of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e190-e192.

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:348-350.

- Abu-Hilal M, Newman JS. Sister Mary Joseph and her nodule: historical and clinical perspective. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:271-273.

A 74-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic umbilical lesion of unknown duration. The patient believed the lesion was a scar resulting from a prior laparoscopic repair of an umbilical hernia. However, the patient reported epigastric abdominal pain and diarrhea of 1 month's duration that he believed was due to the stomach flu. The patient denied fever, chills, loss of appetite, or weight loss. History was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and emphysema. The patient had a surgical history of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in addition to the laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair. The patient's medications included pantoprazole, ondansetron, diphenoxylate-atropine as needed, amlodipine, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and aspirin. Physical examination revealed a 1×2-cm pink, nodular, firm plaque with crust at the umbilicus that was tender on palpation. A shave biopsy of the umbilicus was performed and sent for both pathological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Blaschkoid Unilateral Patch on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is an acquired and self-limited linear inflammatory dermatosis that most frequently occurs in children and less commonly in adults.1-3 Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of an eruption consisting of slightly pigmented, erythematous, flat-topped papules with minimal scaling. These papules quickly coalesce to form a linear band that extends along a limb, the trunk, or the face, within Blaschko lines.1,4 In the adult form, patients tend to experience more diffuse lesions as well as severe pruritus with higher rates of relapse. It occasionally manifests in a dermatomal manner.1

The differential diagnosis includes other linear acquired inflammatory dermatoses such as blaschkitis, lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and psoriasis. Blaschkitis has been described as a rare dermatosis that occurs along the Blaschko lines, affecting adults preferentially over children. Controversy exists whether blaschkitis and lichen striatus are the same disease or 2 separate entities.5 Clinically, both blaschkitis and lichen striatus can present with multiple linear papules and vesicles predominantly on the trunk. In blaschkitis, there is a predilection for males, with an older mean age at onset of 40 years.5 Lesions quickly resolve over months with frequent relapse compared to lichen striatus, which can persist for months to years.

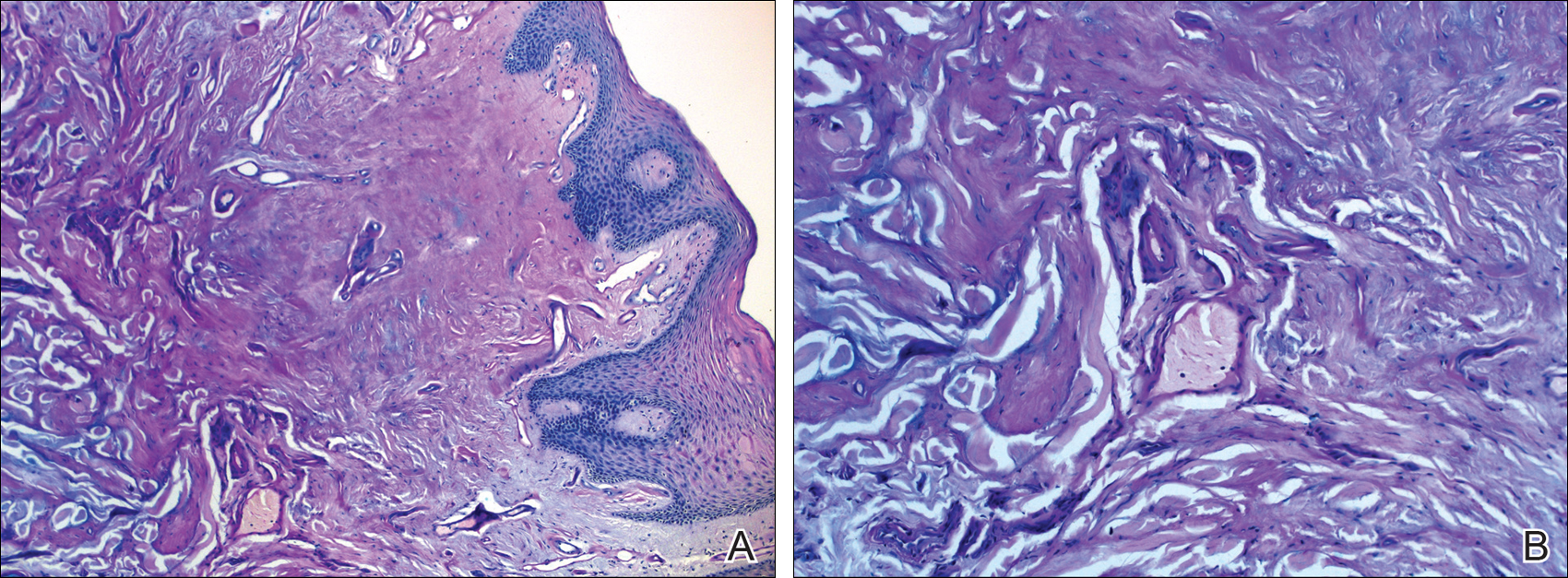

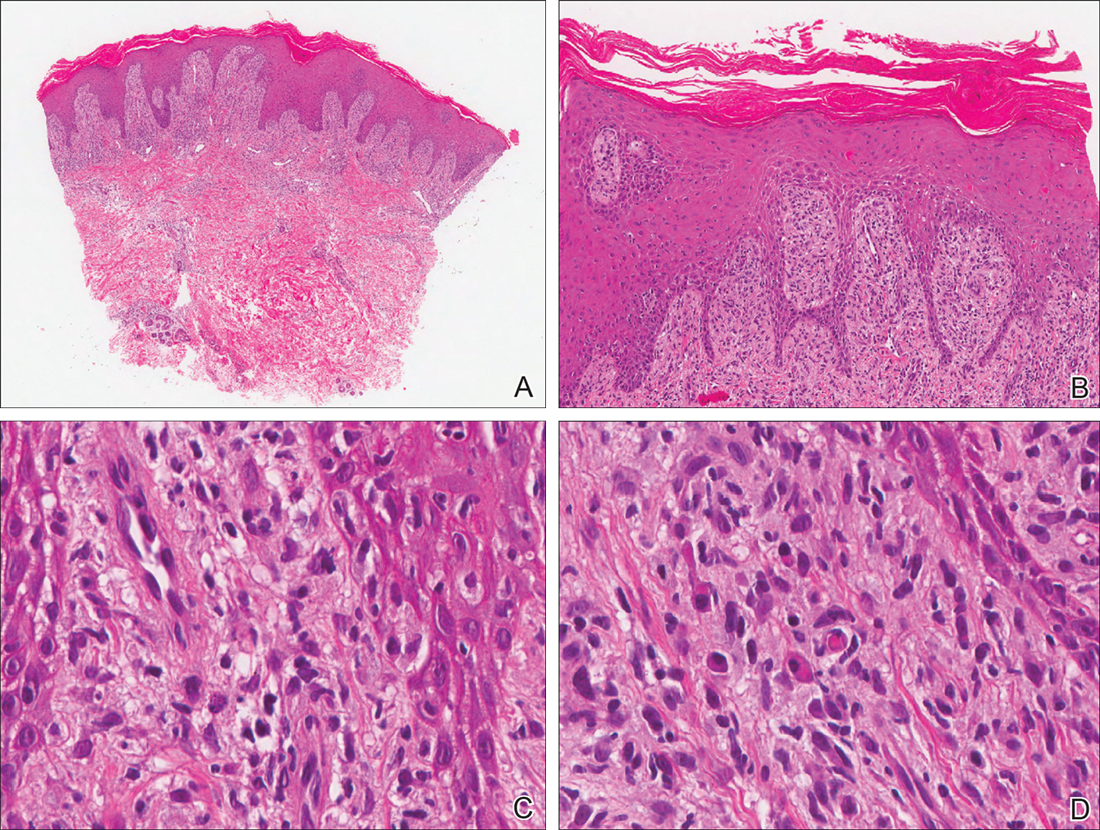

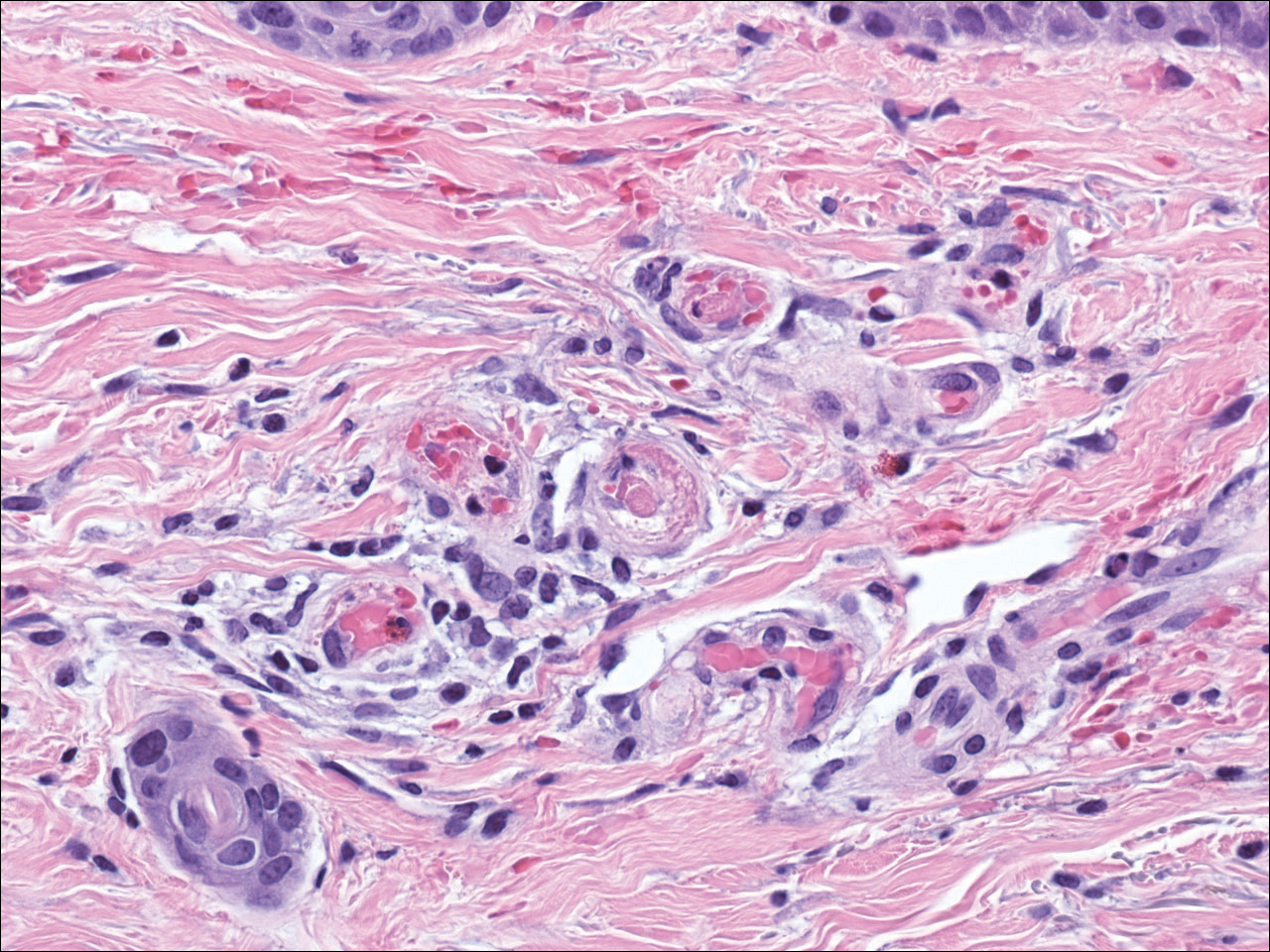

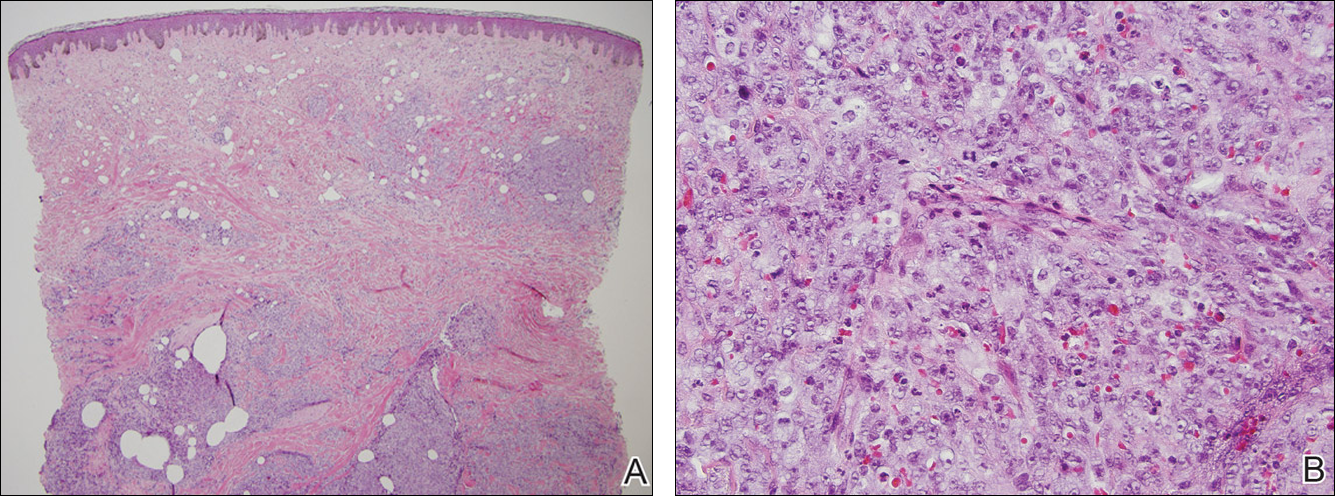

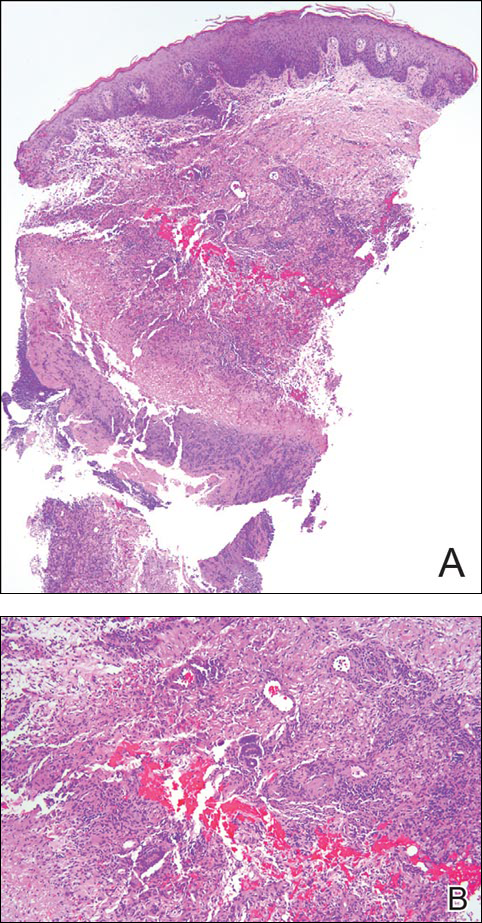

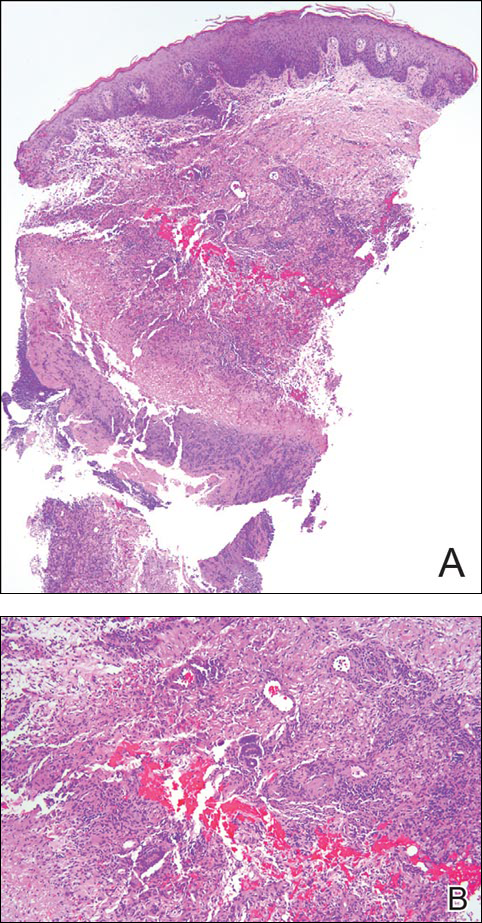

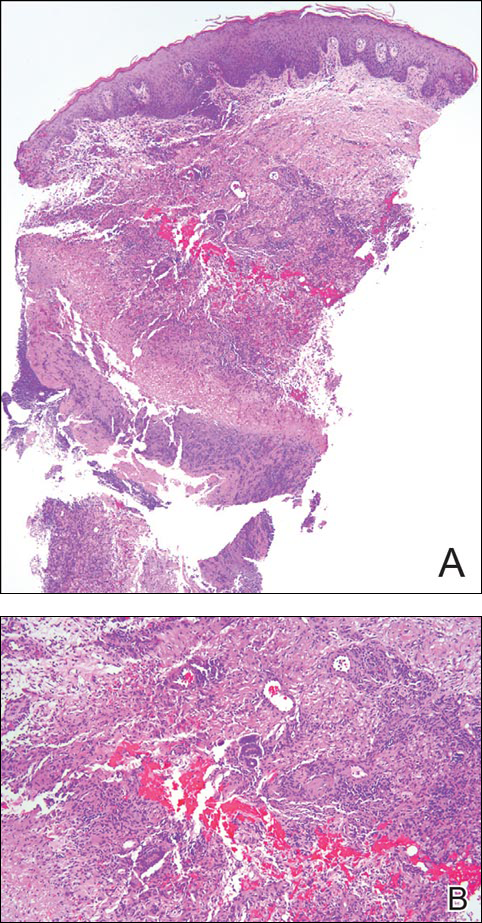

Histopathologically, blaschkitis demonstrates spongiosis, usually without involvement of the adnexal structures. Lichenoid and spongiotic changes with adnexal extension are the hallmark features of lichen striatus. In our patient, biopsy showed several dense bandlike foci of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates along the dermoepidermal junction with spongiosis, basal cell liquefactive degeneration, and pigmentary incontinence (Figure 1). The focal areas were surfaced by parakeratotic and orthohyperkeratotic scale. Deep dermal perivascular and periadnexal extension was present (Figure 2). Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungi.

The pathogenesis of lichen striatus is not entirely understood, but it has been postulated that trauma, vaccinations, or viral infections may induce loss of immunologic tolerance to keratinocytes.1 This loss of tolerance can result in a T cell-mediated autoimmune reaction against malpighian cells, which show genetic mosaicism and are arranged along Blaschko lines.1,3 Familial cases also have been reported, suggesting that there may be an epigenetic mosaicism that contributes to this group of skin diseases.6,7

Lichen striatus tends to resolve on its own after approximately 6 to 9 months.8 Treatment typically consists of application of topical corticosteroids.1 Cases also have been successfully treated with tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.1,8 Our patient was treated with a midpotency topical steroid with improvement of the appearance but not complete resolution.

- Campanati A, Brandozzi G, Giangiacomi M, et al. Lichen striatus in adults and pimecrolimus: open, off-label clinical study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:732-736.

- Lee DY, Kim S, Kim CR, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult treated by a short course of low-dose systemic corticosteroid. J Dermatol. 2011;38:298-299.

- Hofer T. Lichen striatus in adults or "adult blaschkitis"? there is no need for a new naming. Dermatology. 2003;207:89-92.

- Shepherd V, Lun K, Strutton G. Lichen striatus in an adult following trauma. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:25-28.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Yaosaka M, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Lichen striatus affecting a mother and her son. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:352-353.

- Jackson R. The lines of Blaschko: a review and reconsideration: observations of the cause of certain unusual linear conditions of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:349-360.

- Sorgentini C, Allevato MA, Dahbar M, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult: successful treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:776-777.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is an acquired and self-limited linear inflammatory dermatosis that most frequently occurs in children and less commonly in adults.1-3 Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of an eruption consisting of slightly pigmented, erythematous, flat-topped papules with minimal scaling. These papules quickly coalesce to form a linear band that extends along a limb, the trunk, or the face, within Blaschko lines.1,4 In the adult form, patients tend to experience more diffuse lesions as well as severe pruritus with higher rates of relapse. It occasionally manifests in a dermatomal manner.1

The differential diagnosis includes other linear acquired inflammatory dermatoses such as blaschkitis, lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and psoriasis. Blaschkitis has been described as a rare dermatosis that occurs along the Blaschko lines, affecting adults preferentially over children. Controversy exists whether blaschkitis and lichen striatus are the same disease or 2 separate entities.5 Clinically, both blaschkitis and lichen striatus can present with multiple linear papules and vesicles predominantly on the trunk. In blaschkitis, there is a predilection for males, with an older mean age at onset of 40 years.5 Lesions quickly resolve over months with frequent relapse compared to lichen striatus, which can persist for months to years.

Histopathologically, blaschkitis demonstrates spongiosis, usually without involvement of the adnexal structures. Lichenoid and spongiotic changes with adnexal extension are the hallmark features of lichen striatus. In our patient, biopsy showed several dense bandlike foci of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates along the dermoepidermal junction with spongiosis, basal cell liquefactive degeneration, and pigmentary incontinence (Figure 1). The focal areas were surfaced by parakeratotic and orthohyperkeratotic scale. Deep dermal perivascular and periadnexal extension was present (Figure 2). Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungi.

The pathogenesis of lichen striatus is not entirely understood, but it has been postulated that trauma, vaccinations, or viral infections may induce loss of immunologic tolerance to keratinocytes.1 This loss of tolerance can result in a T cell-mediated autoimmune reaction against malpighian cells, which show genetic mosaicism and are arranged along Blaschko lines.1,3 Familial cases also have been reported, suggesting that there may be an epigenetic mosaicism that contributes to this group of skin diseases.6,7

Lichen striatus tends to resolve on its own after approximately 6 to 9 months.8 Treatment typically consists of application of topical corticosteroids.1 Cases also have been successfully treated with tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.1,8 Our patient was treated with a midpotency topical steroid with improvement of the appearance but not complete resolution.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus (LS) is an acquired and self-limited linear inflammatory dermatosis that most frequently occurs in children and less commonly in adults.1-3 Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of an eruption consisting of slightly pigmented, erythematous, flat-topped papules with minimal scaling. These papules quickly coalesce to form a linear band that extends along a limb, the trunk, or the face, within Blaschko lines.1,4 In the adult form, patients tend to experience more diffuse lesions as well as severe pruritus with higher rates of relapse. It occasionally manifests in a dermatomal manner.1

The differential diagnosis includes other linear acquired inflammatory dermatoses such as blaschkitis, lichen planus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, and psoriasis. Blaschkitis has been described as a rare dermatosis that occurs along the Blaschko lines, affecting adults preferentially over children. Controversy exists whether blaschkitis and lichen striatus are the same disease or 2 separate entities.5 Clinically, both blaschkitis and lichen striatus can present with multiple linear papules and vesicles predominantly on the trunk. In blaschkitis, there is a predilection for males, with an older mean age at onset of 40 years.5 Lesions quickly resolve over months with frequent relapse compared to lichen striatus, which can persist for months to years.

Histopathologically, blaschkitis demonstrates spongiosis, usually without involvement of the adnexal structures. Lichenoid and spongiotic changes with adnexal extension are the hallmark features of lichen striatus. In our patient, biopsy showed several dense bandlike foci of lymphohistiocytic infiltrates along the dermoepidermal junction with spongiosis, basal cell liquefactive degeneration, and pigmentary incontinence (Figure 1). The focal areas were surfaced by parakeratotic and orthohyperkeratotic scale. Deep dermal perivascular and periadnexal extension was present (Figure 2). Periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungi.

The pathogenesis of lichen striatus is not entirely understood, but it has been postulated that trauma, vaccinations, or viral infections may induce loss of immunologic tolerance to keratinocytes.1 This loss of tolerance can result in a T cell-mediated autoimmune reaction against malpighian cells, which show genetic mosaicism and are arranged along Blaschko lines.1,3 Familial cases also have been reported, suggesting that there may be an epigenetic mosaicism that contributes to this group of skin diseases.6,7

Lichen striatus tends to resolve on its own after approximately 6 to 9 months.8 Treatment typically consists of application of topical corticosteroids.1 Cases also have been successfully treated with tacrolimus and pimecrolimus.1,8 Our patient was treated with a midpotency topical steroid with improvement of the appearance but not complete resolution.

- Campanati A, Brandozzi G, Giangiacomi M, et al. Lichen striatus in adults and pimecrolimus: open, off-label clinical study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:732-736.

- Lee DY, Kim S, Kim CR, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult treated by a short course of low-dose systemic corticosteroid. J Dermatol. 2011;38:298-299.

- Hofer T. Lichen striatus in adults or "adult blaschkitis"? there is no need for a new naming. Dermatology. 2003;207:89-92.

- Shepherd V, Lun K, Strutton G. Lichen striatus in an adult following trauma. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:25-28.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Yaosaka M, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Lichen striatus affecting a mother and her son. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:352-353.

- Jackson R. The lines of Blaschko: a review and reconsideration: observations of the cause of certain unusual linear conditions of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:349-360.

- Sorgentini C, Allevato MA, Dahbar M, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult: successful treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:776-777.

- Campanati A, Brandozzi G, Giangiacomi M, et al. Lichen striatus in adults and pimecrolimus: open, off-label clinical study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:732-736.

- Lee DY, Kim S, Kim CR, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult treated by a short course of low-dose systemic corticosteroid. J Dermatol. 2011;38:298-299.

- Hofer T. Lichen striatus in adults or "adult blaschkitis"? there is no need for a new naming. Dermatology. 2003;207:89-92.

- Shepherd V, Lun K, Strutton G. Lichen striatus in an adult following trauma. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:25-28.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Yaosaka M, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Lichen striatus affecting a mother and her son. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:352-353.

- Jackson R. The lines of Blaschko: a review and reconsideration: observations of the cause of certain unusual linear conditions of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:349-360.

- Sorgentini C, Allevato MA, Dahbar M, et al. Lichen striatus in an adult: successful treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:776-777.

A 26-year-old man presented with erythematous, scaly, grouped papules along the right side of the chest of 3 weeks' duration, extending to the flank following a blaschkoid distribution on the right side of the chest and not crossing the midline. He reported occasional irritation but otherwise was asymptomatic. His medical history was unremarkable and he was not taking any medications. He also denied trauma to the area.

Beaded Papules Along the Eyelid Margins

The Diagnosis: Lipoid Proteinosis

Lipoid proteinosis (LP), also known as hyalinosis cutis et mucosae or Urbach-Wiethe disease, is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. It is characterized by deposition of hyalinelike material in multiple organs including the skin, oral mucosa, larynx, and brain. The underlying defect is mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene, ECM1, which binds to various proteins (eg, perlecan, fibulins, matrix metalloproteinase 9) and plays a role in angiogenesis and epidermal differentiation.1-4

The clinical spectrum of LP is primarily related to respiratory, skin, and neurologic manifestations, but any organ involvement may be seen. A childhood-onset weak cry or hoarseness usually is the first clinical sign of LP due to infiltration of the laryngeal mucosa.3-6 A thickened frenulum, which manifests as restricted tongue movements, is another reliable clinical sign of LP.7 In addition, yellow-white submucous infiltrates on other mucosal surfaces (eg, pharynx, tongue, soft palate, esophagus)(Figure 1), occlusion of the salivary ducts (recurrent parotitis), dental anomalies, and dental caries (Figure 2) also may be seen.5,7

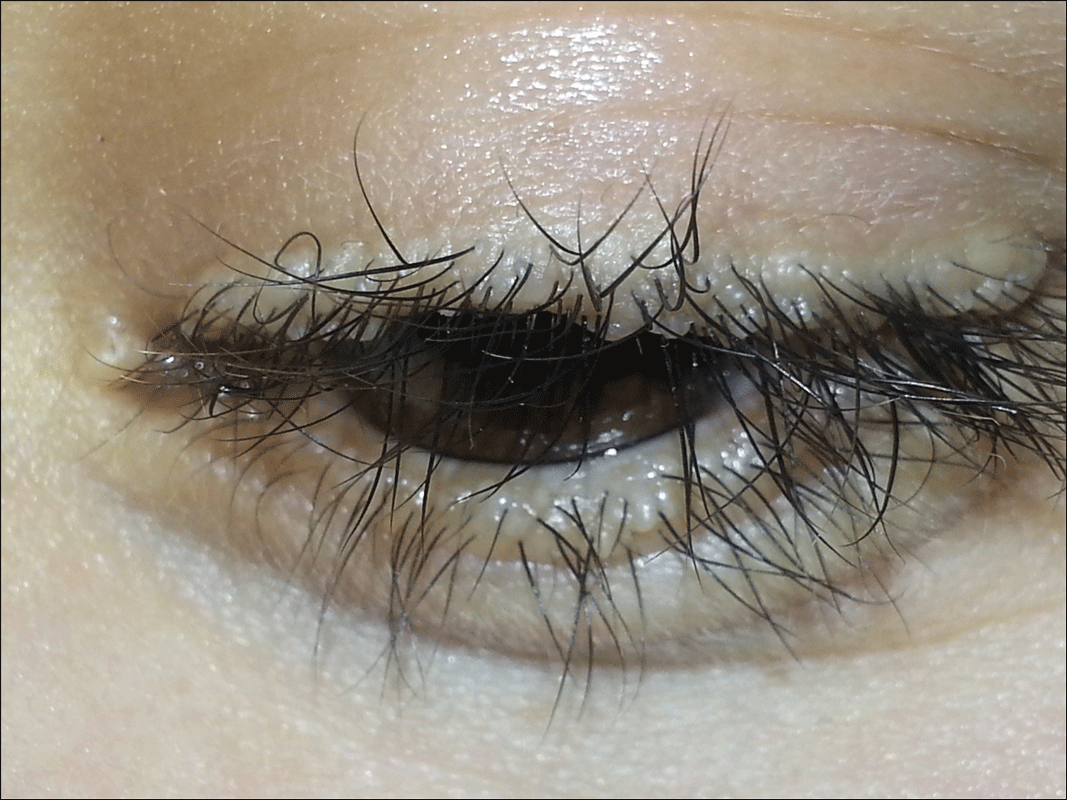

Related to cutaneous manifestations of LP, lesions that present in early childhood are characterized by vesicles, erosions, and hemorrhagic crusts that result in pocklike (Figure 3), linear, or cribriform scarring on the face and extremities, either following trauma or spontaneously.6,7 Second-stage skin lesions are beaded papules (moniliform blepharosis) along the eyelid margins; generalized cutaneous thickening with yellowish discoloration; and waxy papules, hyperkeratosis, or verrucous plaques/nodules on the hands, forehead, axillae, scrotum, elbows, or knees.1,5

Neurological manifestations usually occur as epilepsy and psychiatric problems, which are likely due to intracranial calcification within the amygdala or the temporal lobe. Bean-shaped calcification in the temporal lobe is seen as a pathognomonic radiographic finding.7 Other manifestations including drusenlike fundal lesions, corneal deposits with diminution of vision, and visceral involvement may be seen.7,8

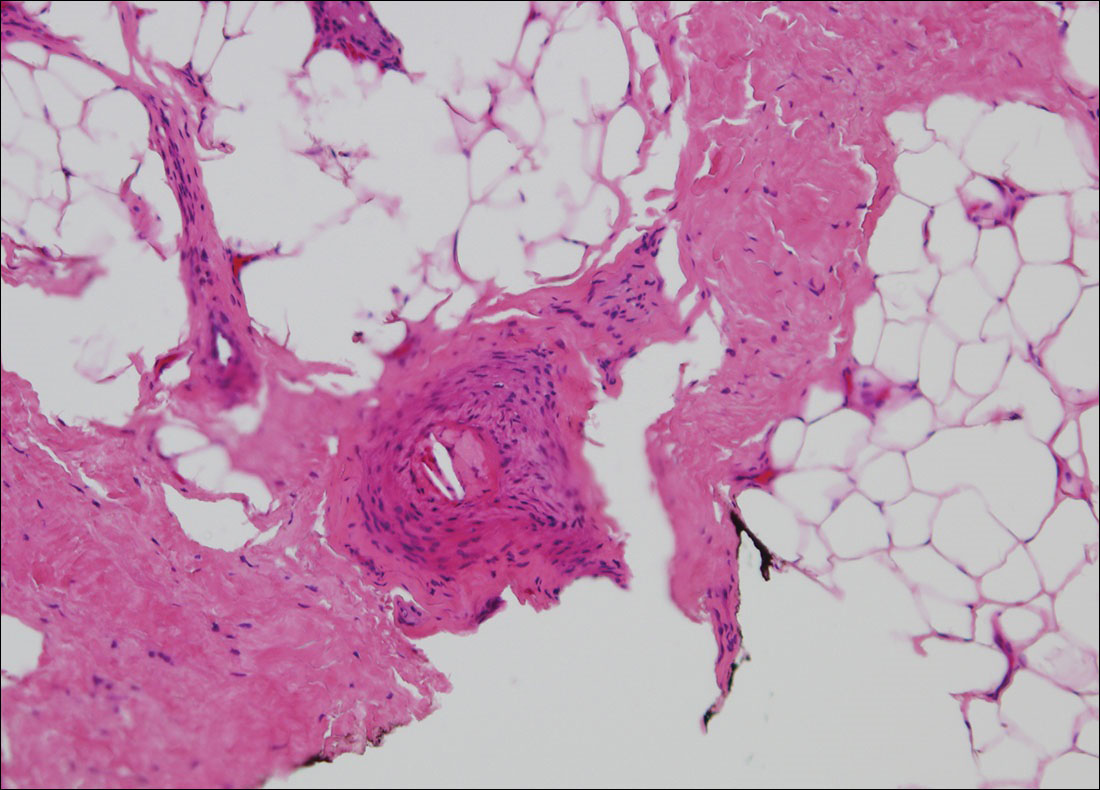

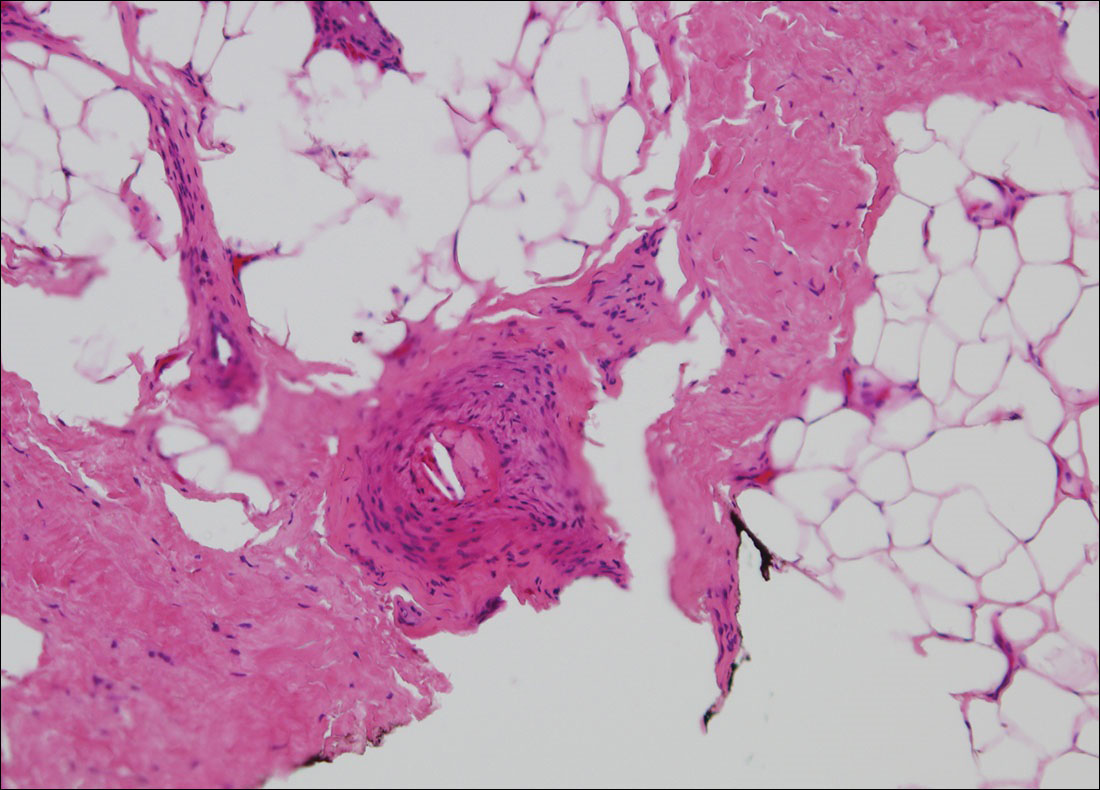

Histologically, deposition of eosinophilic homogeneous material is seen around the blood vessels and sweat glands as well as in the dermis and dermoepidermal junction (Figure 4).1,5 Although most patients with LP have a slowly progressive benign course that stabilizes in early adult life, some morbidities and complications may occur (eg, rarely upper respiratory tract involvement can progress and require tracheostomy). There presently is no cure for LP, but some drugs (eg, oral dimethyl sulfoxide, etretinate, acitretin, penicillamine) and laser ablation/dermabrasion of papules are helpful in some cases.1,7

- Sarkany RPE, Breathnach S, Morris AAM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional disorders. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:59.41-59.42.

- Hamada T, McLean WH, Ramsay M, et al. Lipoid proteinosis maps to 1q21and is caused by mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene (ECM1). Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:833-840.

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Houla NS, et al. Two Egyptian cases of lipoid proteinosis successfully treated with acitretin. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:29-34.

- Dogramaci AC, Celik MM, Celik E, et al. Lipoid proteinosis in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:318-322.

- Franke I, Gollnick H. Deposition diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:633-640.

- Parmar NV, Krishna CV, De D, et al. Papules, pock-like scars, and hoarseness of voice. lipoid proteinosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:136.

- Dyer JA. Lipoid proteinosis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:1288-1292.

- Gutte R, Sanghvi S, Tamhankar P, et al. Lipoid proteinosis: histopathological characterization of early papulovesicular lesions. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:148-149.

The Diagnosis: Lipoid Proteinosis

Lipoid proteinosis (LP), also known as hyalinosis cutis et mucosae or Urbach-Wiethe disease, is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. It is characterized by deposition of hyalinelike material in multiple organs including the skin, oral mucosa, larynx, and brain. The underlying defect is mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene, ECM1, which binds to various proteins (eg, perlecan, fibulins, matrix metalloproteinase 9) and plays a role in angiogenesis and epidermal differentiation.1-4

The clinical spectrum of LP is primarily related to respiratory, skin, and neurologic manifestations, but any organ involvement may be seen. A childhood-onset weak cry or hoarseness usually is the first clinical sign of LP due to infiltration of the laryngeal mucosa.3-6 A thickened frenulum, which manifests as restricted tongue movements, is another reliable clinical sign of LP.7 In addition, yellow-white submucous infiltrates on other mucosal surfaces (eg, pharynx, tongue, soft palate, esophagus)(Figure 1), occlusion of the salivary ducts (recurrent parotitis), dental anomalies, and dental caries (Figure 2) also may be seen.5,7

Related to cutaneous manifestations of LP, lesions that present in early childhood are characterized by vesicles, erosions, and hemorrhagic crusts that result in pocklike (Figure 3), linear, or cribriform scarring on the face and extremities, either following trauma or spontaneously.6,7 Second-stage skin lesions are beaded papules (moniliform blepharosis) along the eyelid margins; generalized cutaneous thickening with yellowish discoloration; and waxy papules, hyperkeratosis, or verrucous plaques/nodules on the hands, forehead, axillae, scrotum, elbows, or knees.1,5

Neurological manifestations usually occur as epilepsy and psychiatric problems, which are likely due to intracranial calcification within the amygdala or the temporal lobe. Bean-shaped calcification in the temporal lobe is seen as a pathognomonic radiographic finding.7 Other manifestations including drusenlike fundal lesions, corneal deposits with diminution of vision, and visceral involvement may be seen.7,8

Histologically, deposition of eosinophilic homogeneous material is seen around the blood vessels and sweat glands as well as in the dermis and dermoepidermal junction (Figure 4).1,5 Although most patients with LP have a slowly progressive benign course that stabilizes in early adult life, some morbidities and complications may occur (eg, rarely upper respiratory tract involvement can progress and require tracheostomy). There presently is no cure for LP, but some drugs (eg, oral dimethyl sulfoxide, etretinate, acitretin, penicillamine) and laser ablation/dermabrasion of papules are helpful in some cases.1,7

The Diagnosis: Lipoid Proteinosis

Lipoid proteinosis (LP), also known as hyalinosis cutis et mucosae or Urbach-Wiethe disease, is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. It is characterized by deposition of hyalinelike material in multiple organs including the skin, oral mucosa, larynx, and brain. The underlying defect is mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene, ECM1, which binds to various proteins (eg, perlecan, fibulins, matrix metalloproteinase 9) and plays a role in angiogenesis and epidermal differentiation.1-4

The clinical spectrum of LP is primarily related to respiratory, skin, and neurologic manifestations, but any organ involvement may be seen. A childhood-onset weak cry or hoarseness usually is the first clinical sign of LP due to infiltration of the laryngeal mucosa.3-6 A thickened frenulum, which manifests as restricted tongue movements, is another reliable clinical sign of LP.7 In addition, yellow-white submucous infiltrates on other mucosal surfaces (eg, pharynx, tongue, soft palate, esophagus)(Figure 1), occlusion of the salivary ducts (recurrent parotitis), dental anomalies, and dental caries (Figure 2) also may be seen.5,7

Related to cutaneous manifestations of LP, lesions that present in early childhood are characterized by vesicles, erosions, and hemorrhagic crusts that result in pocklike (Figure 3), linear, or cribriform scarring on the face and extremities, either following trauma or spontaneously.6,7 Second-stage skin lesions are beaded papules (moniliform blepharosis) along the eyelid margins; generalized cutaneous thickening with yellowish discoloration; and waxy papules, hyperkeratosis, or verrucous plaques/nodules on the hands, forehead, axillae, scrotum, elbows, or knees.1,5

Neurological manifestations usually occur as epilepsy and psychiatric problems, which are likely due to intracranial calcification within the amygdala or the temporal lobe. Bean-shaped calcification in the temporal lobe is seen as a pathognomonic radiographic finding.7 Other manifestations including drusenlike fundal lesions, corneal deposits with diminution of vision, and visceral involvement may be seen.7,8

Histologically, deposition of eosinophilic homogeneous material is seen around the blood vessels and sweat glands as well as in the dermis and dermoepidermal junction (Figure 4).1,5 Although most patients with LP have a slowly progressive benign course that stabilizes in early adult life, some morbidities and complications may occur (eg, rarely upper respiratory tract involvement can progress and require tracheostomy). There presently is no cure for LP, but some drugs (eg, oral dimethyl sulfoxide, etretinate, acitretin, penicillamine) and laser ablation/dermabrasion of papules are helpful in some cases.1,7

- Sarkany RPE, Breathnach S, Morris AAM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional disorders. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:59.41-59.42.

- Hamada T, McLean WH, Ramsay M, et al. Lipoid proteinosis maps to 1q21and is caused by mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene (ECM1). Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:833-840.

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Houla NS, et al. Two Egyptian cases of lipoid proteinosis successfully treated with acitretin. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:29-34.

- Dogramaci AC, Celik MM, Celik E, et al. Lipoid proteinosis in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:318-322.

- Franke I, Gollnick H. Deposition diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:633-640.

- Parmar NV, Krishna CV, De D, et al. Papules, pock-like scars, and hoarseness of voice. lipoid proteinosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:136.

- Dyer JA. Lipoid proteinosis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:1288-1292.

- Gutte R, Sanghvi S, Tamhankar P, et al. Lipoid proteinosis: histopathological characterization of early papulovesicular lesions. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:148-149.

- Sarkany RPE, Breathnach S, Morris AAM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional disorders. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Vol 2. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:59.41-59.42.

- Hamada T, McLean WH, Ramsay M, et al. Lipoid proteinosis maps to 1q21and is caused by mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene (ECM1). Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:833-840.

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Houla NS, et al. Two Egyptian cases of lipoid proteinosis successfully treated with acitretin. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:29-34.

- Dogramaci AC, Celik MM, Celik E, et al. Lipoid proteinosis in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:318-322.

- Franke I, Gollnick H. Deposition diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:633-640.

- Parmar NV, Krishna CV, De D, et al. Papules, pock-like scars, and hoarseness of voice. lipoid proteinosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:136.

- Dyer JA. Lipoid proteinosis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007:1288-1292.

- Gutte R, Sanghvi S, Tamhankar P, et al. Lipoid proteinosis: histopathological characterization of early papulovesicular lesions. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:148-149.

A 21-year-old woman (born of consanguineous parents) presented with asymptomatic, waxy, white, beaded papules along the eyelid margins of 6 years' duration. Physical examination revealed moniliform blepharosis over the eyelid margins, multiple linear and pocklike scars on the face and arm, pebbling on the lower lip and oropharynx, and hoarseness that was present since early infancy. Medical history was unremarkable for systemic disorders and routine laboratory tests were within reference range. Pathological examination of a papule on the lower lip mucosae revealed perivascular deposition of eosinophilic homogeneous material.

Reticular Hyperpigmentation on the Lower Legs

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

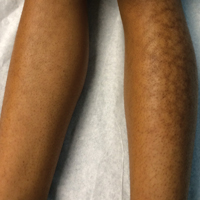

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Given the patient's reticulated hyperpigmented lesions in the setting of recent space heater use with heater closer to the more affected leg, erythema ab igne was diagnosed. Patient education was provided and moving the heater away from the lower extremities was advised.

Erythema ab igne first was described by German dermatologist Abraham Buschke as hitze melanose, meaning melanosis induced by heat. The classic skin findings were first observed on the lower legs of patients who worked in front of open fires or coal stoves.1 Over the years, new causes of erythema ab igne secondary to prolonged thermal radiation exposure have been reported.1 In the elderly, hospitalized, and chronic pain patients, erythema ab igne has been observed in areas treated with heating pads and blankets.2 Other triggers such as frequent hot bathing, furniture, steam radiators, space heaters, and laptops also have been reported.3-6 Laptop-induced erythema ab igne is a diagnosis that has been reported in the last decade and its incidence likely will increase in the future.6

The clinical manifestations of erythema ab igne correlate with the frequency and duration of heat exposure. Acutely, a mild and transient erythema develops in the affected area. With chronic heat exposure, these areas subsequently develop a permanent reticulated hyperpigmented pattern and may eventually become atrophic.2,6 All body surfaces are at risk, but erythema ab igne classically involves the legs, lower back, and/or abdomen. Lesions typically are asymptomatic; however, burning and pruritus can be present.2,6 Bullous erythema ab igne, though rare, has been reported,7 suggesting a potential transition from erythema ab igne to burns.6

Biopsy is not recommended for diagnosis; however, the histopathologic changes of erythema ab igne include hyperkeratosis, interface dermatitis, epidermal atrophy with apoptotic keratinocytes, and melanin incontinence. Although this condition typically is benign, histologic findings could resemble actinic keratosis, suggesting that chronic changes induced by infrared thermal radiation may lead to squamous cell carcinoma or rarely Merkel cell carcinoma. The latency for developing carcinoma appears to extend 30 years, with a 30% tendency for recurrence or metastasis. Given the possibility of an increase in erythema ab igne in the pediatric population in the upcoming years, as displayed by our patient, and increasing laptop and electronic use in children and adolescents, it is important to be aware of this skin condition and the potential complications of it going undiagnosed.2,6

No specific therapy for erythema ab igne exists. Treatment is centered on eliminating exposure to the heat source. With appropriate removal, the reticulated hyperpigmented lesions will resolve, sometimes taking several months.

Differential diagnosis includes livedo reticularis, livedoid vasculopathy, and cutis marmorata. The reticulated purpuric lesions of livedo reticularis involving the extremities often mimic erythema ab igne's cutaneous morphology; however, livedo reticularis frequently is associated with conditions such as drug reactions, infections, thrombosis, and vasculitides,2 as opposed to erythema ab igne, which frequently is associated with conditions causing pain or decreased body temperature, thus necessitating use of heating devices, as seen in our patient. Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by purpuric macules involving the lower legs and feet that progress to recurrent leg ulcers. Our patient's asymptomatic lesions and absence of ulcers excluded this diagnosis.8 Lastly, cutis marmorata, a congenital condition, is characterized by blue-violet vascular networks that often display ulceration and atrophy of the involved skin as well as hypertrophy or atrophy of the involved limb9; these clinical findings were not present in our patient and this diagnosis would not explain the relationship between the cutaneous lesions and heat exposure.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

- Nilic M, Adams BB. Erythema ab igne induced by a laptop computer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:973-974.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR, Robinson FW, et al. Erythema ab igne mimicking livedo reticularis. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1314-1317.

- Lin SJ, Hsu CJ, Chiu HC. Erythema ab igne caused by frequent hot bathing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:478-479.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM. Furniture-induced erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:516-517.

- Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:369-375.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer−induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature [published online October 4, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1227-e1230.

- Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Baz K, et al. Bullous erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:18.

- Khenifer S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: thrombotic or inflammatory disease? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;35:693-698.

- Pernet C, Guillot B, Bigorre M, et al. Focal and atrophic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e268-e269.

A 13-year-old otherwise healthy adolescent girl presented to the pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a rash on the legs. The patient noticed the rash 1 month prior to presentation. The rash initially involved the left shin and gradually spread to involve the shins bilaterally. The rash was asymptomatic with no pain, pruritus, or muscular asymmetry of the legs. She denied recent fevers, chills, or travel. The patient reported using a space heater daily that was directed at the legs, approximately 0.5 m away. Physical examination revealed a well-nourished adolescent girl in no acute distress with reticular hyperpigmentation of the lower extremities located on the left anterior shin and knee, with mild involvement of the right shin. The reticulated hyperpigmented areas were arranged in a rectangular distribution. Lower extremity musculoskeletal examination was symmetric.

Painful Purple Toes

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

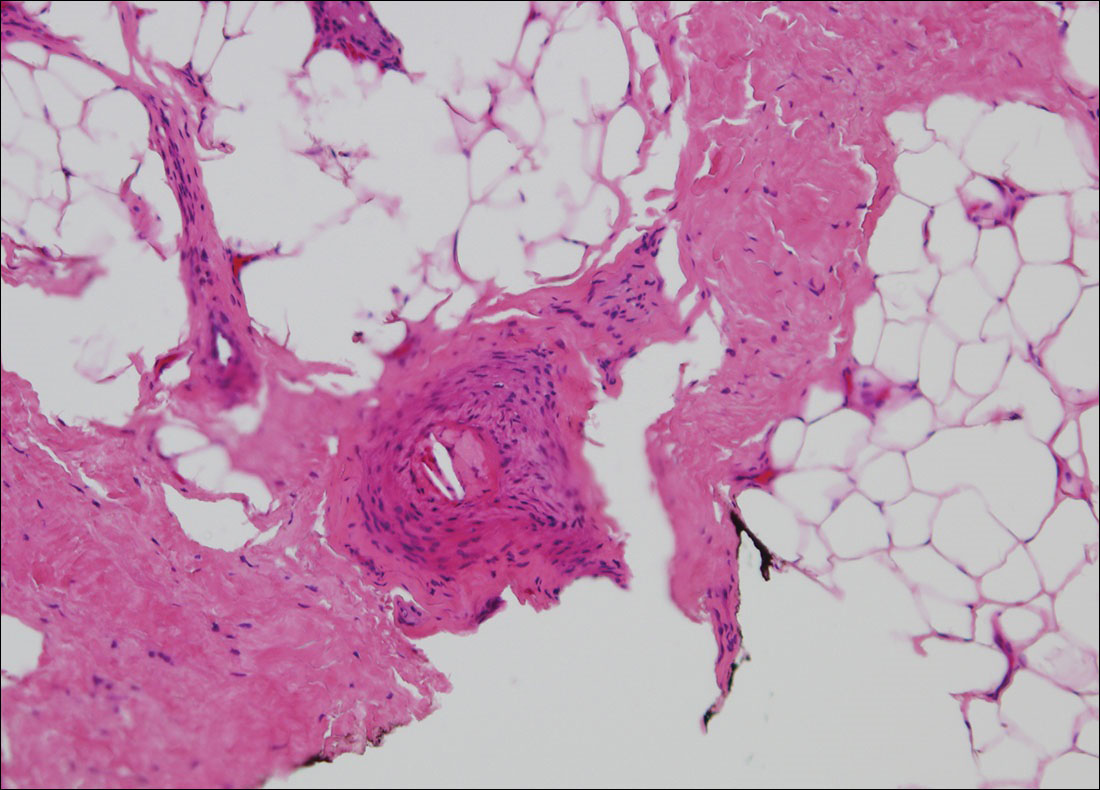

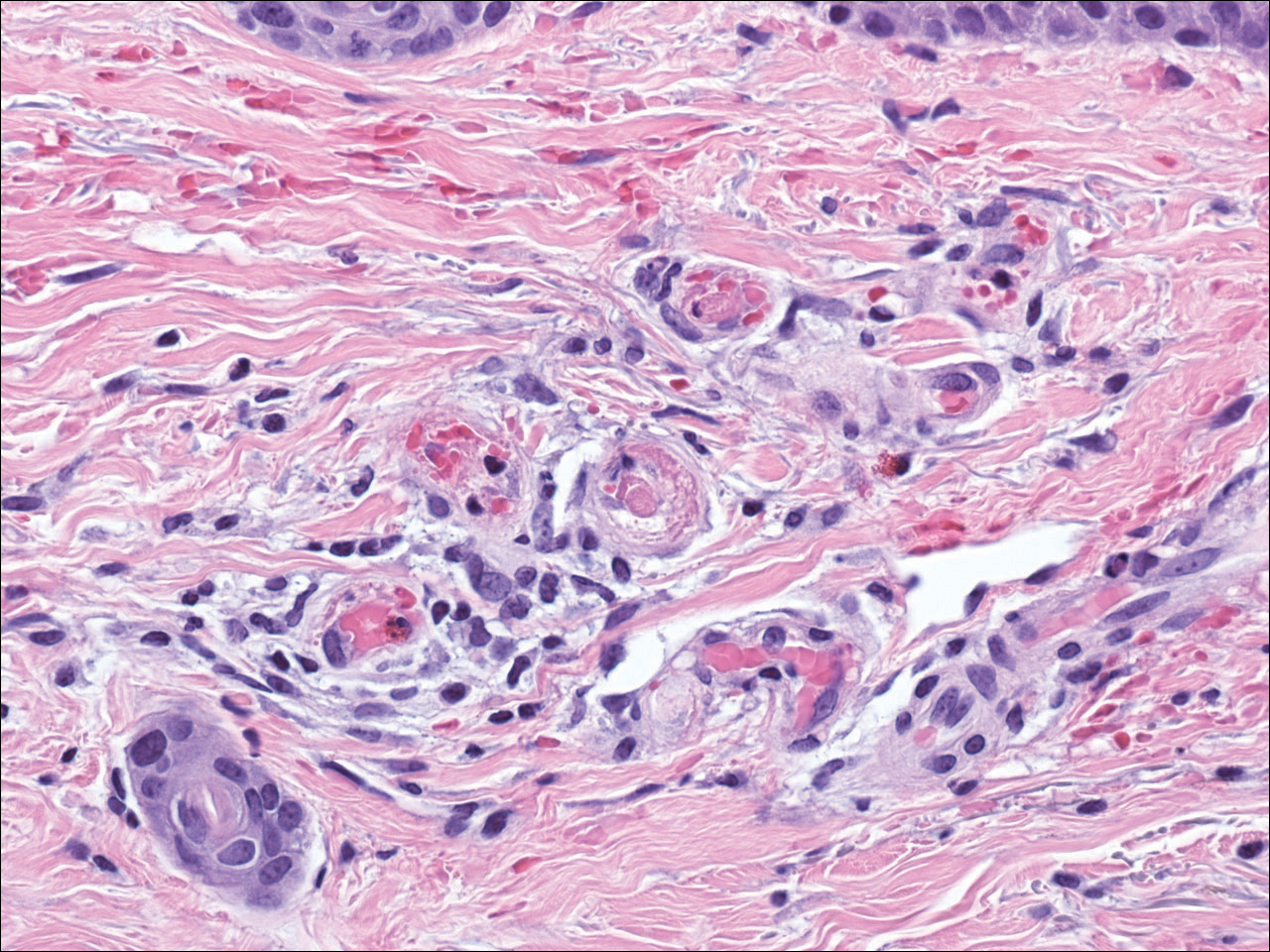

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

The Diagnosis: Blue Toe Syndrome

The clinical manifestation suggested blue toe syndrome. A variety of causes for blue toe syndrome are known such as embolism, thrombosis, vasoconstrictive disorders, infectious and noninfectious inflammation, extensive venous thrombosis, and abnormal circulating blood.1 Among them, only emboli from atherosclerotic plaques give rise to typical cholesterol clefts on skin biopsy (Figure 1). Such atheroemboli often are an iatrogenic complication, especially those caused by invasive percutaneous procedures or damage to the arterial walls from vascular surgery. However, spontaneous plaque hemorrhage or shearing forces of the circulating blood can disrupt atheromatous plaques and cause embolization of the cholesterol crystals, which was likely to be the case in our patient because no preceding trigger events were noted.

Other clinical features also are seen in atheroembolism. Approximately half of patients with atheroembolism develop clinical kidney disease.2 Almost all iatrogenic cases have acute or subacute reduction in glomerular filtration rate of at least to 50% level, whereas the spontaneous cases present as stable chronic renal failure.3 Approximately 20% of patients with atheroembolism also have involvement of digestive organs.4,5 Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal blood loss are common features; bowel infarction and perforation occasionally occur.5 Pancreatitis is another common complication, and serum amylase levels are raised in approximately 50% of patients.6 Atheroemboli may reach the eyes and brain. They occasionally can cause loss of vision,7 as well as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and gradual deterioration in cerebral function.3 Blood eosinophilia, which occurs in approximately 60% of patients, is an important finding.3,8

Although there is no specific therapy for atheroembolism, the use of antiplatelet agents is considered reasonable because they are beneficial in preventing myocardial infarction in patients with atherosclerosis.9 In our case, the livedo reticularis cleared, as did the coldness on the affected toes after 2 weeks of sarpogrelate hydrochloride administration; however, development of necrotic change was noted (Figure 2). Necrotic change on the hallux disappeared after 2 weeks.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1-20; quiz 21-22.

- Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R, et al. The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors. Circulation. 2007;116:298-304.

- Scolari F, Tardanico R, Zani R, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism: a recognizable cause of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:1089-1109.

- Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:653-657.

- Ben-Horin S, Bardan E, Barshack I, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization to the digestive system: characterization of a common, yet overlooked presentation of atheroembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1471-1479.

- Mayo RR, Swartz RD. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Am J Med. 1996;100:524-529.

- Gittinger JW Jr, Kershaw GR. Retinal cholesterol emboli in the diagnosis of renal atheroembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1265-1267.

- Kasinath BS, Corwin HL, Bidani AK, et al. Eosinophilia in the diagnosis of atheroembolic renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:173-177.

- Quinones A, Saric M. The cholesterol emboli syndrome in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:315.

A 63-year-old man presented with sudden onset of severe pain in the right hallux and fifth toe of 3 days' duration. The patient had hypertension and hyperlipidemia with a 45-year history of smoking and had not undergone any vascular procedures. Physical examination revealed relatively well-defined cyanotic change with remarkable coldness on the affected toes as well as livedo reticularis on the underside of the toes. All peripheral pulses were present. Laboratory investigation revealed no remarkable changes with eosinophil counts within reference range and normal renal function. A biopsy taken from the fifth toe revealed thrombotic arterioles with cholesterol clefts.

Thick Scaly Plaques on the Wrists, Knees, and Feet

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

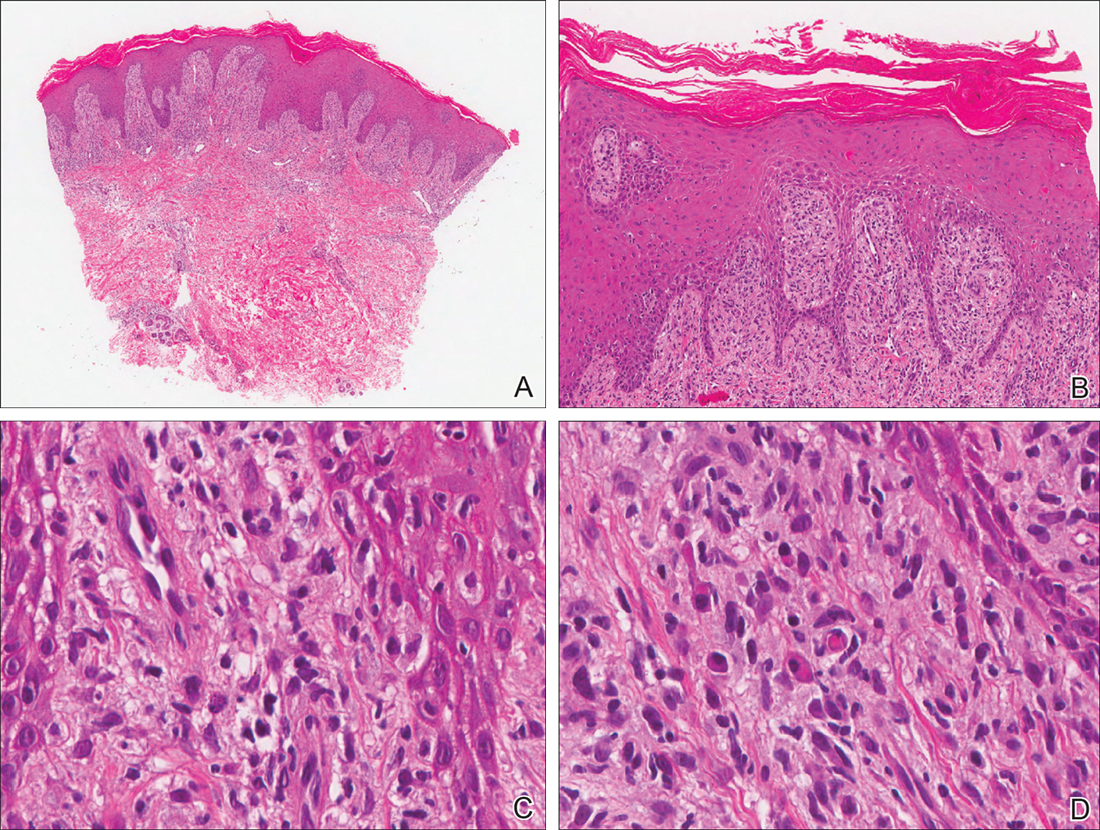

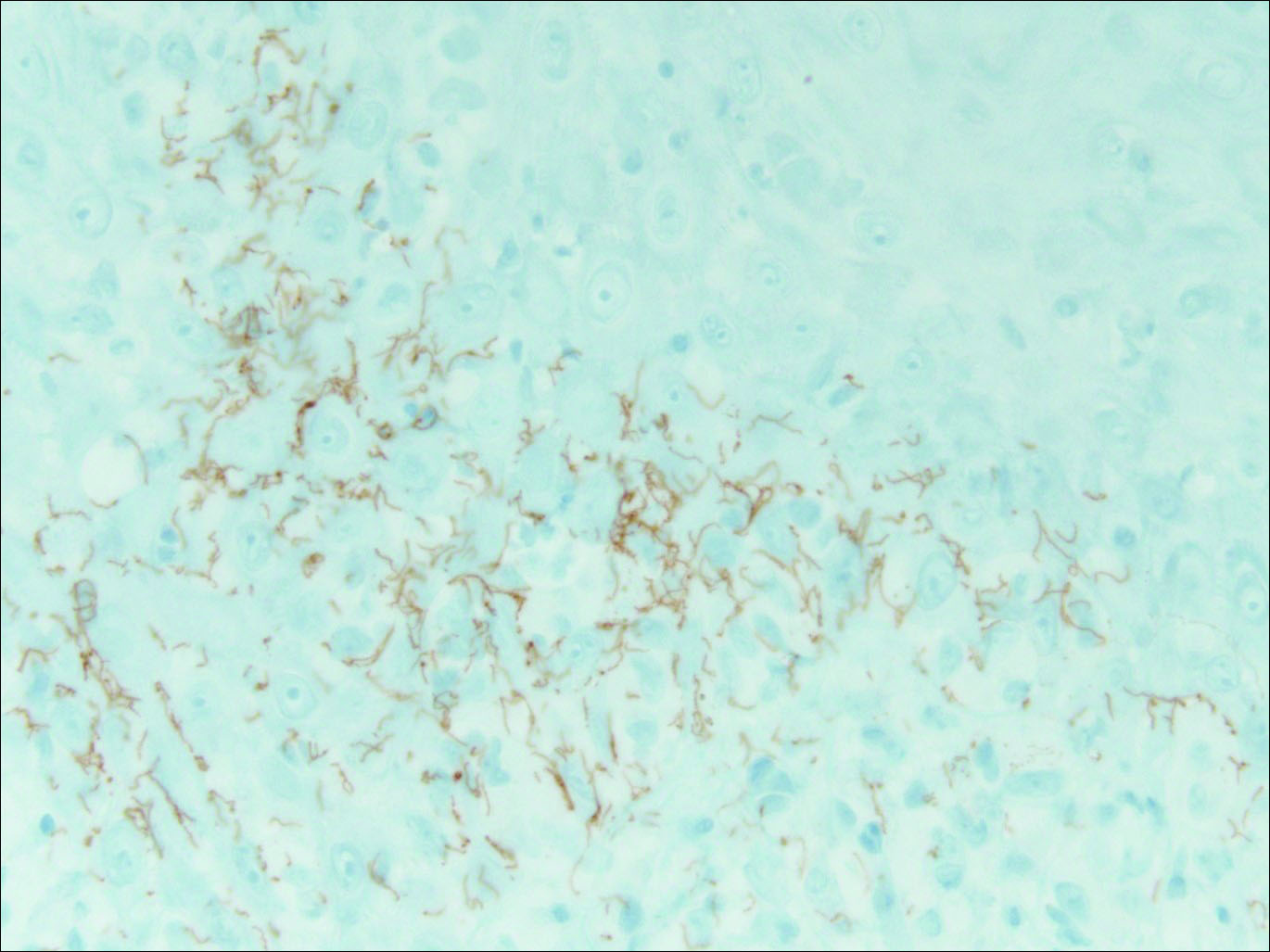

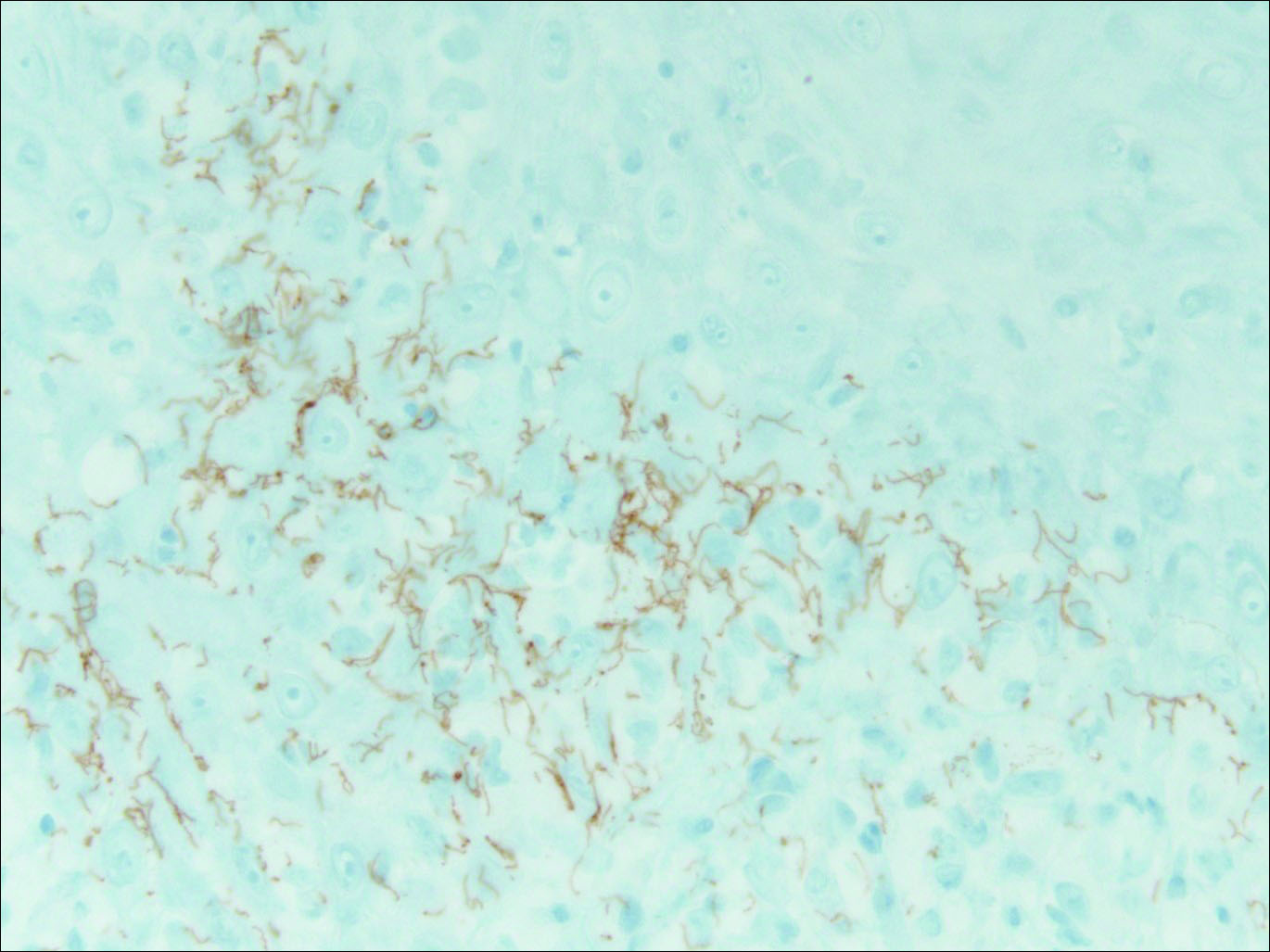

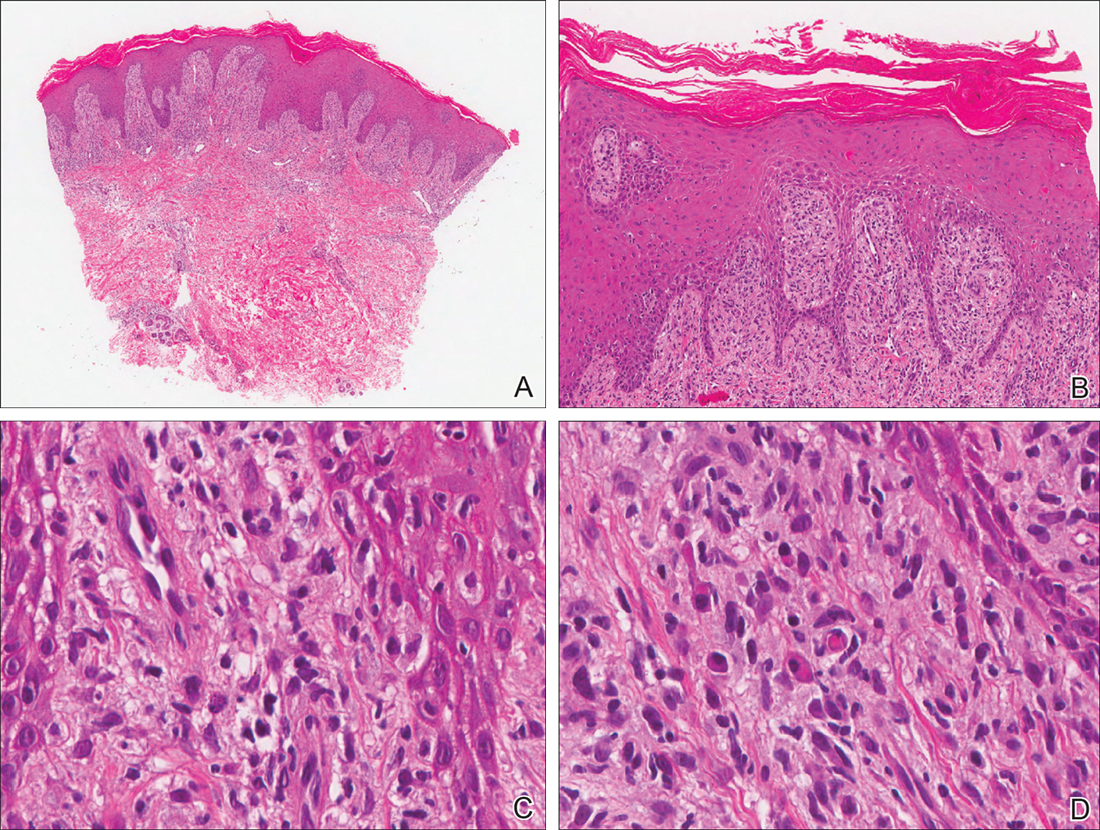

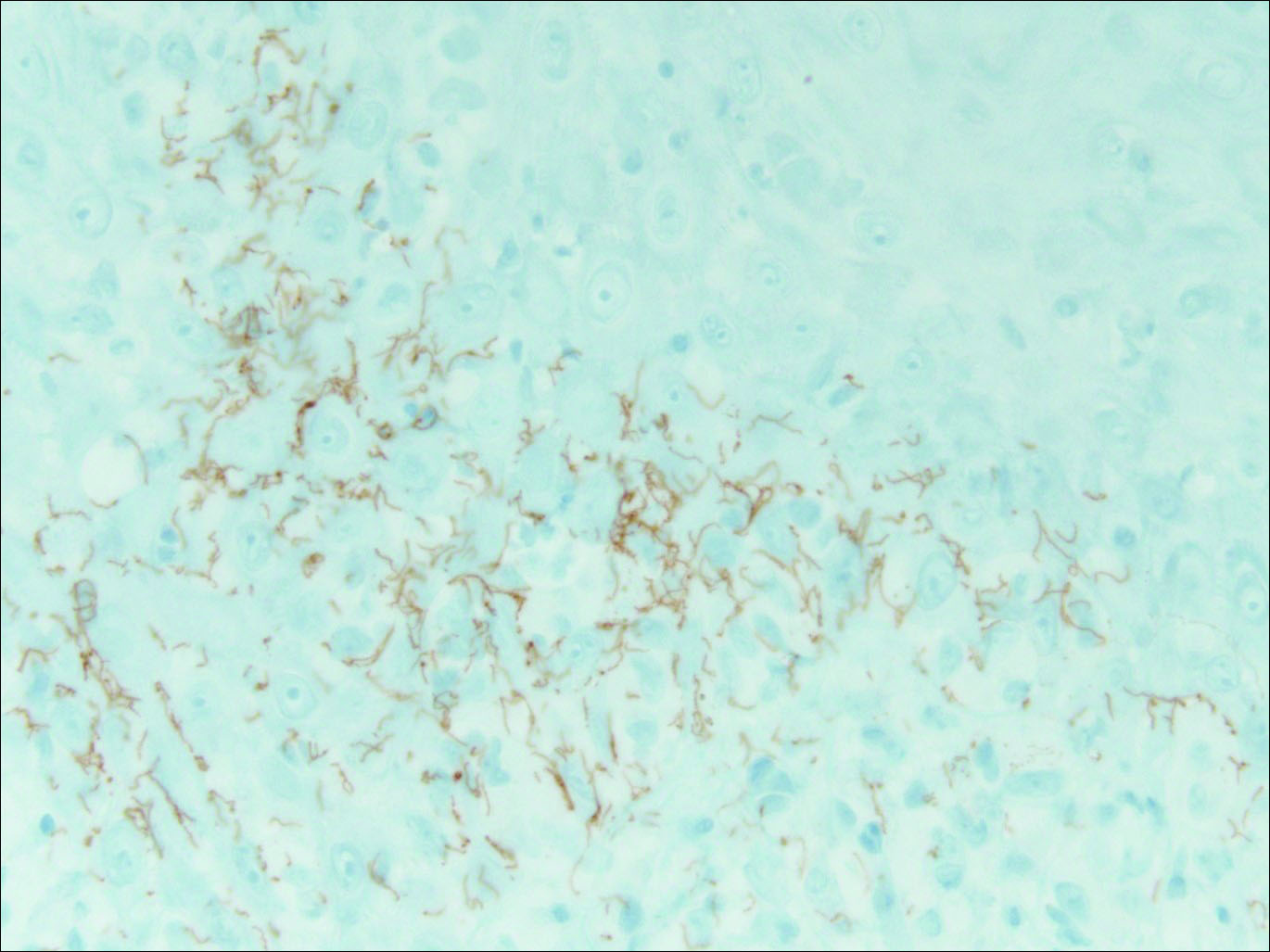

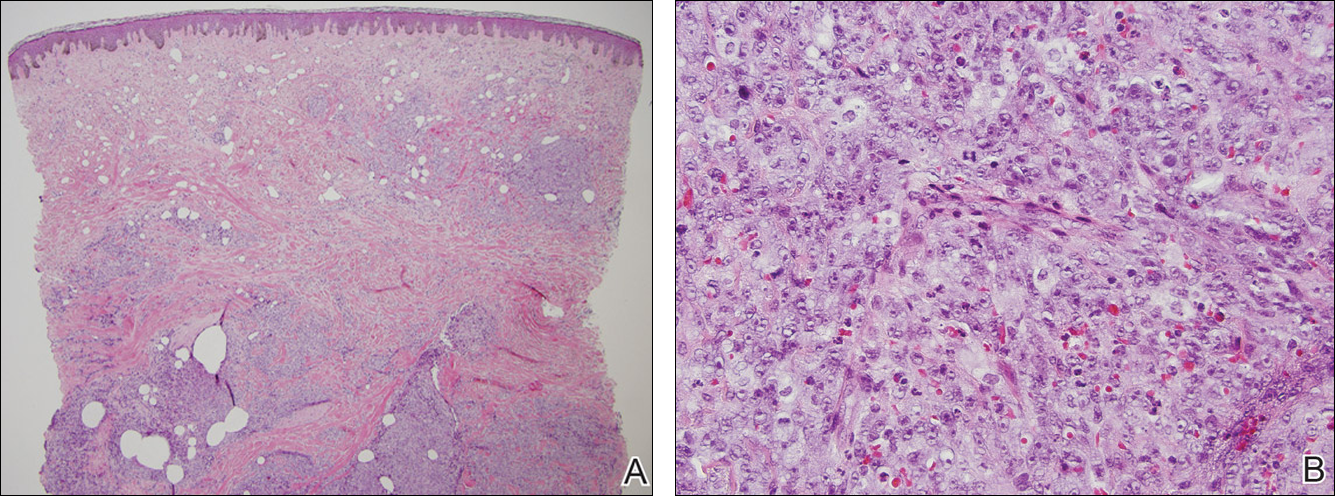

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).