User login

Understanding Principles of High Reliability Organizations Through the Eyes of VIONE, A Clinical Program to Improve Patient Safety by Deprescribing Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Reducing Polypharmacy

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

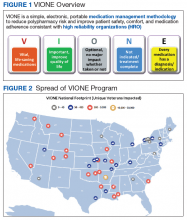

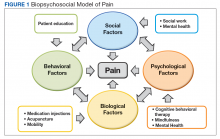

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

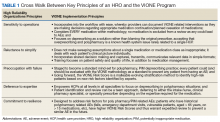

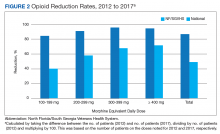

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact [email protected].

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

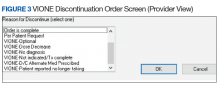

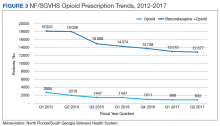

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

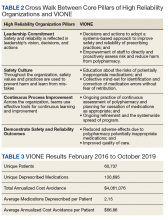

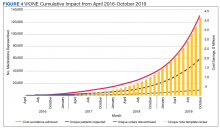

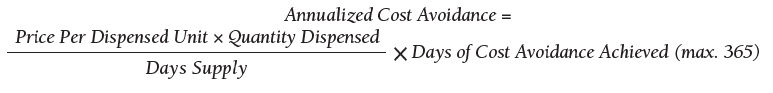

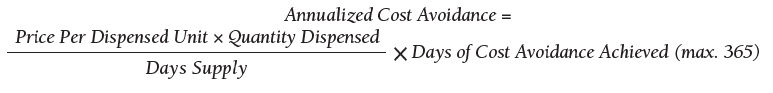

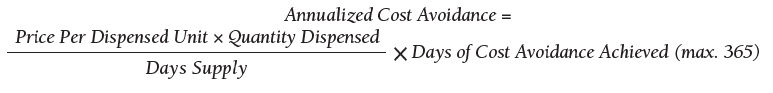

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

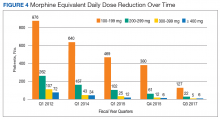

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact [email protected].

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

High reliability organizations (HROs) incorporate continuous process improvement through leadership commitment to create a safety culture that works toward creating a zero-harm environment.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has set transformational goals for becoming an HRO. In this article, we describe VIONE, an expanding medication deprescribing clinical program, which exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system models. Both VIONE and HRO are globally relevant.

Reducing medication errors and related adverse drug events are important for achieving zero harm. Preventable medical errors rank behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the US.2 The simultaneous use of multiple medications can lead to dangerous drug interactions, adverse outcomes, and challenges with adherence. When a person is taking multiple medicines, known as polypharmacy, it is more likely that some are potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Current literature highlights the prevalence and dangers of polypharmacy, which ranks among the top 10 common causes of death in the US, as well as suggestions to address preventable adverse outcomes from polypharmacy and PIM.3-5

Deprescribing of PIM frequently results in better disease management with improved health outcomes and quality of life.4 Many health care settings lack standardized approaches or set expectations to proactively deprescribe PIM. There has been insufficient emphasis on how to make decisions for deprescribing medications when therapeutic benefits are not clear and/or when the adverse effects may outweigh the therapeutic benefits.5

It is imperative to provide practice guidance for deprescribing nonessential medications along with systems-based infrastructure to enable integrated and effective assessments during opportune moments in the health care continuum. Multimodal approaches that include education, risk stratification, population health management interventions, research and resource allocation can help transform organizational culture in health care facilities toward HRO models of care, aiming at zero harm to patients.

The practical lessons learned from VIONE implementation science experiences on various scales and under diverse circumstances, cumulative wisdom from hindsight, foresight and critical insights gathered during nationwide spread of VIONE over the past 3 years continues to propel us toward the desirable direction and core concepts of an HRO.

The VIONE program facilitates practical, real-time interventions that could be tailored to various health care settings, organizational needs, and available resources. VIONE implements an electronic Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) tool to enable planned cessation of nonessential medications that are potentially harmful, inappropriate, not indicated, or not necessary. The VIONE tool supports systematic, individualized assessment and adjustment through 5 filters (Figure 1). It prompts providers to assign 1 of these filters intuitively and objectively. VIONE combines clinical evidence for best practices, an interprofessional team approach, patient engagement, adapted use of existing medical records systems, and HRO principles for effective implementation.

As a tool to support safer prescribing practices, VIONE aligns closely with HRO principles (Table 1) and core pillars (Table 2).6-8 A zero-harm safety culture necessitates that medications be used for correct reasons, over a correct duration of time, and following a correct schedule while monitoring for adverse outcomes. However, reality generally falls significantly short of this for a myriad of reasons, such as compromised health literacy, functional limitations, affordability, communication gaps, patients seen by multiple providers, and an accumulation of prescriptions due to comorbidities, symptom progression, and management of adverse effects. Through a sharpened focus on both precision medicine and competent prescription management, VIONE is a viable opportunity for investing in the zero-harm philosophy that is integral to an HRO.

Design and Implementation

Initially launched in 2016 in a 15-bed inpatient, subacute rehabilitation unit within a VHA tertiary care facility, VIONE has been sustained and gradually expanded to 38 other VHA facility programs (Figure 2). Recognizing the potential value if adopted into widespread use, VIONE was a Gold Status winner in the VHA Under Secretary for Health Shark Tank-style competition in 2017 and was selected by the VHA Diffusion of Excellence as an innovation worthy of scale and spread through national dissemination.9 A toolkit for VIONE implementation, patient and provider brochures, VIONE vignette, and National Dialog template also have been created.10

Implementing VIONE in a new facility requires an actively engaged core team committed to patient safety and reduction of polypharmacy and PIM, interest and availability to lead project implementation strategies, along with meaningful local organizational support. The current structure for VIONE spread is as follows:

- Interested VHA participants review information and contact [email protected].

- The VIONE team orients implementing champions, mainly pharmacists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants at a facility program level, offering guidance and available resources.

- Clinical Application Coordinators at Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System and participating facilities collaborate to add deprescribing menu options in CPRS and install the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog template.

- Through close and ongoing collaborations, medical providers and clinical pharmacists proceed with deprescribing, aiming at planned cessation of nonessential and PIM, using the mnemonic prompt of VIONE. Vital and Important medications are continued and consolidated while a methodical plan is developed to deprescribe any medications that could lead to more harm than benefit and qualify based on the filters of Optional, Not indicated, and Every medicine has a diagnosis/reason. They select the proper discontinuation reasons in the CPRS medication menu (Figure 3) and document the rationale in the progress notes. It is highly encouraged that the collaborating pharmacists and health care providers add each other as cosigners and communicate effectively. Clinical pharmacy specialists also use the VIONE Polypharmacy Reminder Dialog Template (RDT) to document complete medication reviews with veterans to include deprescribing rationale and document shared decision making.

- A VIONE national dashboard captures deprescribing data in real time and automates reporting with daily updates that are readily accessible to all implementing facilities. Minimum data captured include the number of unique veterans impacted, number of medications deprescribed, cumulative cost avoidance to date, and number of prescriptions deprescribed per veteran. The dashboard facilitates real-time use of individual patient data and has also been designed to capture data from VHA administrative data portals and Corporate Data Warehouse.

Results

As of October 31, 2019, the assessment of polypharmacy using the VIONE tool across VHA sites has benefited > 60,000 unique veterans, of whom 49.2% were in urban areas, 47.7% in rural areas, and 3.1% in highly rural areas. Elderly male veterans comprised a clear majority. More than 128,000 medications have been deprescribed. The top classes of medications deprescribed are antihypertensives, over-the-counter medications, and antidiabetic medications. An annualized cost avoidance of > $4.0 million has been achieved. Cost avoidance is the cost of medications that otherwise would have continued to be filled and paid for by the VHA if they had not been deprescribed, projected for a maximum of 365 days. The calculation methodology can be summarized as follows:

The calculations reported in Table 3 and Figure 4 are conservative and include only chronic outpatient prescriptions and do not account for medications deprescribed in inpatient units, nursing home, community living centers, or domiciliary populations. Data tracked separately from inpatient and community living center patient populations indicated an additional 25,536 deprescribed medications, across 28 VA facilities, impacting 7,076 veterans with an average 2.15 medications deprescribed per veteran. The additional achieved cost avoidance was $370,272 (based on $14.50 average cost per prescription). Medications restarted within 30 days of deprescribing are not included in these calculations.

The cost avoidance calculation further excludes the effects of VIONE implementation on many other types of interventions. These interventions include, but are not limited to, changing from aggressive care to end of life, comfort care when strongly indicated; reduced emergency department visits or invasive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, when not indicated; medical supplies, antimicrobial preparations; labor costs related to packaging, mailing, and administering prescriptions; reduced/prevented clinical waste; reduced decompensation of systemic illnesses and subsequent health care needs precipitated by iatrogenic disturbances and prolonged convalescence; and overall changes to prescribing practices through purposeful and targeted interactions with colleagues across various disciplines and various hierarchical levels.

Discussion

The VIONE clinical program exemplifies the translation of HRO principles into health care system practices. VIONE offers a systematic approach to improve medication management with an emphasis on deprescribing nonessential medications across various health care settings, facilitating VHA efforts toward zero harm. It demonstrates close alignment with the key building blocks of an HRO. Effective VIONE incorporation into an organizational culture reflects leadership commitment to safety and reliability in their vision and actions. By empowering staff to proactively reduce inappropriate medications and thereby prevent patient harm, VIONE contributes to enhancing an enterprise-wide culture of safety, with fewer errors and greater reliability. As a standardized decision support tool for the ongoing practice of assessment and planned cessation of potentially inappropriate medications, VIONE illustrates how continuous process improvement can be a part of staff-engaged, veteran-centered, highly reliable care. The standardization of the VIONE tool promotes achievement and sustainment of desired HRO principles and practices within health care delivery systems.

Conclusions

The VIONE program was launched not as a cost savings or research program but as a practical, real-time bedside or ambulatory care intervention to improve patient safety. Its value is reflected in the overwhelming response from scholarly and well-engaged colleagues expressing serious interests in expanding collaborations and tailoring efforts to add more depth and breadth to VIONE related efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Central Arkansas VA Healthcare System leadership, Clinical Applications Coordinators, and colleagues for their unconditional support, to the Diffusion of Excellence programs at US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office for their endorsement, and to the many VHA participants who renew our optimism and energy as we continue this exciting journey. We also thank Bridget B. Kelly for her assistance in writing and editing of the manuscript.

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

1. Chassin MR, Jerod ML. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. The Joint Commission. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459-490.

2. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139.

3. Quinn KJ, Shah NH. A dataset quantifying polypharmacy in the United States. Sci Data. 2017;4:170167.

4. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.

5. Steinman MA. Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):482-483.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. High reliability. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

7. Gordon S, Mendenhall P, O’Connor BB. Beyond the Checklist: What Else Health Care Can Learn from Aviation Teamwork and Safety. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2013.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Diffusion of Excellence. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHCAREEXCELLENCE/diffusion-of-excellence/. Updated August 10, 2018. Accessed June 26, 2019.

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE program toolkit. https://www.vapulse.net/docs/DOC-259375. [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

VA Boston Healthcare System First Friday Faculty Development Presentation Series

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) trains a large number of learners from across multiple health care professions— more than 122,000 in 2017.1 The VA has affiliation agreements with almost all American medical schools (97%), and annually about one-third of all medical residents in the US train at VA academic medical centers (AMCs).1,2 The VA also trains learners in more than 40 health care professions from >1,800 training programs.1,3 This large commitment to training aides the recruitment of these learners as VA clinicians. In fact, a high percentage of current VA clinicians previously trained at the VA. For example, 60% of VA physicians and about 70% of both VA optometrists and psychologists trained at the VA.1

Given the large scope of training experiences and the impact on future employment, it is critical that VA educators provide a highquality learning experience for trainees. To do this, VA educators need both initial and ongoing education and support to grow and develop as teachers and as supervisors.4 Few educators currently report receiving this type of training, which includes effectively providing feedback to trainees, assessing trainee learning, and teaching on interprofessional teams.5

Numerous benefits to the AMC may be realized when a structured approach to faculty development is implemented. Systematic literature reviews of such approaches found that faculty members were satisfied with programming and that the content of programing was useful and relevant to their teaching.6,7 Faculty reported increased positive attitudes toward faculty development and toward teaching, increased knowledge of educational principles, greater establishment of faculty networks, and positive changes in teaching behavior (as identified by faculty and students).6,7 Further, participating in faculty development programming increased teaching effectiveness.6-8 Faculty development programs also provided direct and indirect financial benefits to the AMC and may lead to increased patient safety, increased patient satisfaction with care, and higher quality of care.9,10 Faculty development programming can be delivered via an online system that is as effective as face-to-face trainings and is more cost-efficient than are face-to-face trainings, particularly for educators at rural sites.11

Methods

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is a large AMC with more than 350 academic affiliations, 500 faculty members, and 3200 trainees from a wide range of health care professions. Despite this robust presence of trainees, like many other AMCs, in 2014 VABHS lacked a structured approach to faculty development programming.12,13

To realize the potential benefits of this programming, VABHS developed a framework to conceptualize multiple components of faculty development programming. The framework focused on faculty development activities in 5 areas: teaching, research, awards, interprofessional, networking (TRAIN).14 The TRAIN framework allowed VABHS to develop specific faculty development programs in a strategic and organized manner.

In this article, we describe the VABHS First Friday Faculty Development Presentation series, a faculty development program that was created to improve teaching and supervising skill. The presentation series began in 2014. Faculty members at all 3 VABHS campuses participated in the presentations either in-person or via videoconference. Over time, faculty members at other New England VA AMCs began to express interest in participating, and audio and videoconferences were used to allow participation from those sites.

The program soon developed a national audience. In January 2017, this program provided the opportunity for faculty members to earn continuing education (CE) credits for participation. This allowed faculty members a unique opportunity to earn CE for presentations specifically geared toward improving skills as an educator, which is not widely available—particularly at rural and remote VA sites.

Presentations were 1 hour and held on the first Friday of the month at 12 pm Eastern Standard time. Topics for the presentations were identified through formal and informal needs assessments of faculty and through faculty development needs identified in the literature. Presentation topics consistent with the components of the TRAIN framework were selected. The cost to develop the program was largely related to time spent by presentation organizers to arrange speakers, advertise the presentations, develop a protocol for the use of the technology, and apply for accreditation for participants to receive CE credits.

Presenters were educators from a range of health care professions, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, and other professions from VABHS and neighboring Boston-area AMCs. Topics included providing feedback to learners, using active learning strategies, teaching clinical thinking, reducing burnout among educators, managing work-life balance, and developing interprofessional learning curricula. Presentations are archived online.

Results

From January 2017 to June 2018, 869 CE credits were earned by faculty members at VA AMCs nationwide for participating in this faculty development program, including 359 credits for nurses (41.3%), 164 credits for pharmacists (18.9%), 128 credits for physicians (14.7%), 67 credits for social workers (7.7%), and 54 credits for psychologists (6.2%). Other CE credits were earned by dieticians (14), dentists (13), speech pathologists (3), and occupational therapists (2), and other health care professionals (65).

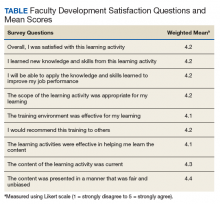

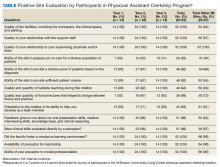

Participants completed satisfaction surveys, responding to 9 questions using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) (Table). Data collection practices were reviewed by the VABHS Internal Review Board, which determined that the data did not meet the definition of human subject research and did not require further review.

Participants were asked 2 additional questions to further assess the programming. Seven hundred forty-eight participants responded to the question “How much did you learn as a result of this CE program?” using Likert-scale responses (1 = very little to 5 = great deal): 56.6% responded with a 4, (fair amount), and 21.5% responded with a 5 (great deal). Participants also were asked whether the content of this CE program was useful for their practice or other professional development (1 = not useful to 5 = extremely useful). Seven hundred forty-nine participants responded with a 4 (useful), and 25.4% of participants responded with a 5 (extremely useful).

Discussion

Overall, participants reported that the presentations were effective in teaching content, they acquired new knowledge, and they can apply this knowledge in future teaching. Participants reported satisfaction with the training activities and that the content was presented in a fair and unbiased manner. Further, they reported the training environment was effective, and they would recommend the training to others.

Conclusion

VABHS will continue to identify mechanisms to further disseminate and enhance this programming, particularly in rural areas, where there is a shortage of faculty development programming.2 We will continue to assess the impact of these presentations on many factors, including patient safety and veteran satisfaction with their health care. We will also seek to understand how many total participants attend each presentation, as we currently have data only from participants who completed the satisfaction survey.

We invite faculty members from all VA AMCs and training sites to attend future presentations. Information about upcoming presentations is disseminated across multiple VA listservs; you can also e-mail the authors to receive notification of future presentations.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2019.

2. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198.

3. Lee J, Sanders K, Cox M. Honoring those who have served: how can health professionals provide optimal care for members of the military, veterans, and their families? Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1198-1200.

4. Houston TK, Ferenchick GS, Clark JM, et al. Faculty development needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):375-379.

5. Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460-467.

6. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526.

7. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786.

8. Lee SM, Lee MC, Reed DA, et al. Success of a faculty development program for teachers at the Mayo Clinic. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):704-708.

9. Topor DR, Roberts DH. Faculty development programming at academic medical centers: identifying financial benefits and value. Med Sci Educ. 2016;26(3):417-419.

10. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al; I-PASS Study Group. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.

11. Maloney S, Haas R, Keating JL, et al. Breakeven, cost benefit, cost effectiveness, and willingness to pay for web-based versus face-to-face education delivery for health professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e47.

12. Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):205-214.

13. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944.

14. Topor DR, Budson AE. A framework for faculty development programming at VA and non-VA Academic Medical.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) trains a large number of learners from across multiple health care professions— more than 122,000 in 2017.1 The VA has affiliation agreements with almost all American medical schools (97%), and annually about one-third of all medical residents in the US train at VA academic medical centers (AMCs).1,2 The VA also trains learners in more than 40 health care professions from >1,800 training programs.1,3 This large commitment to training aides the recruitment of these learners as VA clinicians. In fact, a high percentage of current VA clinicians previously trained at the VA. For example, 60% of VA physicians and about 70% of both VA optometrists and psychologists trained at the VA.1

Given the large scope of training experiences and the impact on future employment, it is critical that VA educators provide a highquality learning experience for trainees. To do this, VA educators need both initial and ongoing education and support to grow and develop as teachers and as supervisors.4 Few educators currently report receiving this type of training, which includes effectively providing feedback to trainees, assessing trainee learning, and teaching on interprofessional teams.5

Numerous benefits to the AMC may be realized when a structured approach to faculty development is implemented. Systematic literature reviews of such approaches found that faculty members were satisfied with programming and that the content of programing was useful and relevant to their teaching.6,7 Faculty reported increased positive attitudes toward faculty development and toward teaching, increased knowledge of educational principles, greater establishment of faculty networks, and positive changes in teaching behavior (as identified by faculty and students).6,7 Further, participating in faculty development programming increased teaching effectiveness.6-8 Faculty development programs also provided direct and indirect financial benefits to the AMC and may lead to increased patient safety, increased patient satisfaction with care, and higher quality of care.9,10 Faculty development programming can be delivered via an online system that is as effective as face-to-face trainings and is more cost-efficient than are face-to-face trainings, particularly for educators at rural sites.11

Methods

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is a large AMC with more than 350 academic affiliations, 500 faculty members, and 3200 trainees from a wide range of health care professions. Despite this robust presence of trainees, like many other AMCs, in 2014 VABHS lacked a structured approach to faculty development programming.12,13

To realize the potential benefits of this programming, VABHS developed a framework to conceptualize multiple components of faculty development programming. The framework focused on faculty development activities in 5 areas: teaching, research, awards, interprofessional, networking (TRAIN).14 The TRAIN framework allowed VABHS to develop specific faculty development programs in a strategic and organized manner.

In this article, we describe the VABHS First Friday Faculty Development Presentation series, a faculty development program that was created to improve teaching and supervising skill. The presentation series began in 2014. Faculty members at all 3 VABHS campuses participated in the presentations either in-person or via videoconference. Over time, faculty members at other New England VA AMCs began to express interest in participating, and audio and videoconferences were used to allow participation from those sites.

The program soon developed a national audience. In January 2017, this program provided the opportunity for faculty members to earn continuing education (CE) credits for participation. This allowed faculty members a unique opportunity to earn CE for presentations specifically geared toward improving skills as an educator, which is not widely available—particularly at rural and remote VA sites.

Presentations were 1 hour and held on the first Friday of the month at 12 pm Eastern Standard time. Topics for the presentations were identified through formal and informal needs assessments of faculty and through faculty development needs identified in the literature. Presentation topics consistent with the components of the TRAIN framework were selected. The cost to develop the program was largely related to time spent by presentation organizers to arrange speakers, advertise the presentations, develop a protocol for the use of the technology, and apply for accreditation for participants to receive CE credits.

Presenters were educators from a range of health care professions, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, and other professions from VABHS and neighboring Boston-area AMCs. Topics included providing feedback to learners, using active learning strategies, teaching clinical thinking, reducing burnout among educators, managing work-life balance, and developing interprofessional learning curricula. Presentations are archived online.

Results

From January 2017 to June 2018, 869 CE credits were earned by faculty members at VA AMCs nationwide for participating in this faculty development program, including 359 credits for nurses (41.3%), 164 credits for pharmacists (18.9%), 128 credits for physicians (14.7%), 67 credits for social workers (7.7%), and 54 credits for psychologists (6.2%). Other CE credits were earned by dieticians (14), dentists (13), speech pathologists (3), and occupational therapists (2), and other health care professionals (65).

Participants completed satisfaction surveys, responding to 9 questions using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) (Table). Data collection practices were reviewed by the VABHS Internal Review Board, which determined that the data did not meet the definition of human subject research and did not require further review.

Participants were asked 2 additional questions to further assess the programming. Seven hundred forty-eight participants responded to the question “How much did you learn as a result of this CE program?” using Likert-scale responses (1 = very little to 5 = great deal): 56.6% responded with a 4, (fair amount), and 21.5% responded with a 5 (great deal). Participants also were asked whether the content of this CE program was useful for their practice or other professional development (1 = not useful to 5 = extremely useful). Seven hundred forty-nine participants responded with a 4 (useful), and 25.4% of participants responded with a 5 (extremely useful).

Discussion

Overall, participants reported that the presentations were effective in teaching content, they acquired new knowledge, and they can apply this knowledge in future teaching. Participants reported satisfaction with the training activities and that the content was presented in a fair and unbiased manner. Further, they reported the training environment was effective, and they would recommend the training to others.

Conclusion

VABHS will continue to identify mechanisms to further disseminate and enhance this programming, particularly in rural areas, where there is a shortage of faculty development programming.2 We will continue to assess the impact of these presentations on many factors, including patient safety and veteran satisfaction with their health care. We will also seek to understand how many total participants attend each presentation, as we currently have data only from participants who completed the satisfaction survey.

We invite faculty members from all VA AMCs and training sites to attend future presentations. Information about upcoming presentations is disseminated across multiple VA listservs; you can also e-mail the authors to receive notification of future presentations.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) trains a large number of learners from across multiple health care professions— more than 122,000 in 2017.1 The VA has affiliation agreements with almost all American medical schools (97%), and annually about one-third of all medical residents in the US train at VA academic medical centers (AMCs).1,2 The VA also trains learners in more than 40 health care professions from >1,800 training programs.1,3 This large commitment to training aides the recruitment of these learners as VA clinicians. In fact, a high percentage of current VA clinicians previously trained at the VA. For example, 60% of VA physicians and about 70% of both VA optometrists and psychologists trained at the VA.1

Given the large scope of training experiences and the impact on future employment, it is critical that VA educators provide a highquality learning experience for trainees. To do this, VA educators need both initial and ongoing education and support to grow and develop as teachers and as supervisors.4 Few educators currently report receiving this type of training, which includes effectively providing feedback to trainees, assessing trainee learning, and teaching on interprofessional teams.5

Numerous benefits to the AMC may be realized when a structured approach to faculty development is implemented. Systematic literature reviews of such approaches found that faculty members were satisfied with programming and that the content of programing was useful and relevant to their teaching.6,7 Faculty reported increased positive attitudes toward faculty development and toward teaching, increased knowledge of educational principles, greater establishment of faculty networks, and positive changes in teaching behavior (as identified by faculty and students).6,7 Further, participating in faculty development programming increased teaching effectiveness.6-8 Faculty development programs also provided direct and indirect financial benefits to the AMC and may lead to increased patient safety, increased patient satisfaction with care, and higher quality of care.9,10 Faculty development programming can be delivered via an online system that is as effective as face-to-face trainings and is more cost-efficient than are face-to-face trainings, particularly for educators at rural sites.11

Methods

The VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) is a large AMC with more than 350 academic affiliations, 500 faculty members, and 3200 trainees from a wide range of health care professions. Despite this robust presence of trainees, like many other AMCs, in 2014 VABHS lacked a structured approach to faculty development programming.12,13

To realize the potential benefits of this programming, VABHS developed a framework to conceptualize multiple components of faculty development programming. The framework focused on faculty development activities in 5 areas: teaching, research, awards, interprofessional, networking (TRAIN).14 The TRAIN framework allowed VABHS to develop specific faculty development programs in a strategic and organized manner.

In this article, we describe the VABHS First Friday Faculty Development Presentation series, a faculty development program that was created to improve teaching and supervising skill. The presentation series began in 2014. Faculty members at all 3 VABHS campuses participated in the presentations either in-person or via videoconference. Over time, faculty members at other New England VA AMCs began to express interest in participating, and audio and videoconferences were used to allow participation from those sites.

The program soon developed a national audience. In January 2017, this program provided the opportunity for faculty members to earn continuing education (CE) credits for participation. This allowed faculty members a unique opportunity to earn CE for presentations specifically geared toward improving skills as an educator, which is not widely available—particularly at rural and remote VA sites.

Presentations were 1 hour and held on the first Friday of the month at 12 pm Eastern Standard time. Topics for the presentations were identified through formal and informal needs assessments of faculty and through faculty development needs identified in the literature. Presentation topics consistent with the components of the TRAIN framework were selected. The cost to develop the program was largely related to time spent by presentation organizers to arrange speakers, advertise the presentations, develop a protocol for the use of the technology, and apply for accreditation for participants to receive CE credits.

Presenters were educators from a range of health care professions, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, and other professions from VABHS and neighboring Boston-area AMCs. Topics included providing feedback to learners, using active learning strategies, teaching clinical thinking, reducing burnout among educators, managing work-life balance, and developing interprofessional learning curricula. Presentations are archived online.

Results

From January 2017 to June 2018, 869 CE credits were earned by faculty members at VA AMCs nationwide for participating in this faculty development program, including 359 credits for nurses (41.3%), 164 credits for pharmacists (18.9%), 128 credits for physicians (14.7%), 67 credits for social workers (7.7%), and 54 credits for psychologists (6.2%). Other CE credits were earned by dieticians (14), dentists (13), speech pathologists (3), and occupational therapists (2), and other health care professionals (65).

Participants completed satisfaction surveys, responding to 9 questions using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) (Table). Data collection practices were reviewed by the VABHS Internal Review Board, which determined that the data did not meet the definition of human subject research and did not require further review.

Participants were asked 2 additional questions to further assess the programming. Seven hundred forty-eight participants responded to the question “How much did you learn as a result of this CE program?” using Likert-scale responses (1 = very little to 5 = great deal): 56.6% responded with a 4, (fair amount), and 21.5% responded with a 5 (great deal). Participants also were asked whether the content of this CE program was useful for their practice or other professional development (1 = not useful to 5 = extremely useful). Seven hundred forty-nine participants responded with a 4 (useful), and 25.4% of participants responded with a 5 (extremely useful).

Discussion

Overall, participants reported that the presentations were effective in teaching content, they acquired new knowledge, and they can apply this knowledge in future teaching. Participants reported satisfaction with the training activities and that the content was presented in a fair and unbiased manner. Further, they reported the training environment was effective, and they would recommend the training to others.

Conclusion

VABHS will continue to identify mechanisms to further disseminate and enhance this programming, particularly in rural areas, where there is a shortage of faculty development programming.2 We will continue to assess the impact of these presentations on many factors, including patient safety and veteran satisfaction with their health care. We will also seek to understand how many total participants attend each presentation, as we currently have data only from participants who completed the satisfaction survey.

We invite faculty members from all VA AMCs and training sites to attend future presentations. Information about upcoming presentations is disseminated across multiple VA listservs; you can also e-mail the authors to receive notification of future presentations.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2019.

2. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198.

3. Lee J, Sanders K, Cox M. Honoring those who have served: how can health professionals provide optimal care for members of the military, veterans, and their families? Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1198-1200.

4. Houston TK, Ferenchick GS, Clark JM, et al. Faculty development needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):375-379.

5. Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460-467.

6. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526.

7. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786.

8. Lee SM, Lee MC, Reed DA, et al. Success of a faculty development program for teachers at the Mayo Clinic. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):704-708.

9. Topor DR, Roberts DH. Faculty development programming at academic medical centers: identifying financial benefits and value. Med Sci Educ. 2016;26(3):417-419.

10. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al; I-PASS Study Group. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.

11. Maloney S, Haas R, Keating JL, et al. Breakeven, cost benefit, cost effectiveness, and willingness to pay for web-based versus face-to-face education delivery for health professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e47.

12. Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):205-214.

13. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944.

14. Topor DR, Budson AE. A framework for faculty development programming at VA and non-VA Academic Medical.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2019.

2. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198.

3. Lee J, Sanders K, Cox M. Honoring those who have served: how can health professionals provide optimal care for members of the military, veterans, and their families? Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1198-1200.

4. Houston TK, Ferenchick GS, Clark JM, et al. Faculty development needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):375-379.

5. Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460-467.

6. Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497-526.

7. Steinert Y, Mann K, Anderson B, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Med Teach. 2016;38(8):769-786.

8. Lee SM, Lee MC, Reed DA, et al. Success of a faculty development program for teachers at the Mayo Clinic. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):704-708.

9. Topor DR, Roberts DH. Faculty development programming at academic medical centers: identifying financial benefits and value. Med Sci Educ. 2016;26(3):417-419.

10. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al; I-PASS Study Group. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812.

11. Maloney S, Haas R, Keating JL, et al. Breakeven, cost benefit, cost effectiveness, and willingness to pay for web-based versus face-to-face education delivery for health professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e47.

12. Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):205-214.

13. Hatem CJ, Lown BA, Newman LR. The academic health center coming of age: helping faculty become better teachers and agents of educational change. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):941-944.

14. Topor DR, Budson AE. A framework for faculty development programming at VA and non-VA Academic Medical.

Telehealth Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Patients With Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

According to World Health Organization estimates, 65 million people have moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) globally, and > 20 million patients with COPD are living in the US.1 COPD is a progressive respiratory disease with a poor prognosis and a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US, especially within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).2 The prevalence of COPD is higher in veterans than it is in the general population. COPD prevalence in the adult US population has been estimated to be between 5% and 15%, whereas in veterans, prevalence estimates have ranged from about 5% to 43%.3-5

COPD is associated with disabling dyspnea, muscle weakness, exercise intolerance, morbidity, and mortality. These symptoms and complications gradually and progressively compromise mobility, ability to perform daily functions, and decrease quality of life (QOL). Dyspnea, fatigue, and discomfort are the principal symptoms that negatively impact exercise tolerance.6,7 Therefore, patients often intentionally limit their activities to avoid these uncomfortable feelings and adopt a more sedentary behavior. As the disease progresses, individuals with COPD will gradually need assistance in performing activities of daily living, which eventually leads to functional dependence.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an essential component of the management of symptomatic patients with COPD. PR is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, comprehensive intervention that includes exercise and education for patients with chronic respiratory disease.8 The key benefits of PR are clinical improvements in dyspnea, physical capacity, QOL, and reduced disability in patients with COPD and other respiratory diseases.9-11 PR was found to improve respiratory health in veterans with COPD and decrease respiratory-related health care utilization.12

Despite the known benefits of PR, many patients with chronic respiratory diseases are not referred or do not have access to rehabilitation. Also, uptake of PR is low due to patient frailty, transportation issues, and other health care access problems.13-15 Unfortunately, in the US health care system, access to PR and other nonpharmacologic treatments can be challenging due to a shortage of available PR programs, limited physician referral to existing programs, and lack of family and social support.16

There are only a few accredited PR programs in VHA facilities, and they tend to be located in urban areas.12,17 Many patients have limited access to the PR programs due to geographic distance to the programs and transportation challenges (eg, limited ability to drive, cost of transportation). Moreover, veterans with COPD are likely to have limited mobility or are homebound due to experiencing shortness of breath with minimal exertion. Given the clear benefits of PR and the increasing impact of COPD on morbidity and mortality of the patients with COPD, strategies to improve the access and capacity of PR are needed. VA telehealth services allow for distribution of health care services in different geographic locations by providing access for the veterans who live in rural and highly rural areas. The most recent implementation of VA Video Connect (VVC) by the VHA provides a new avenue for clinicians to deliver much needed medical care into the veterans’ home.

COPD Telehealth Program

In this article, we describe the processes for developing and delivering an in-home, interactive, supervised PR program for veterans with severe COPD through VA telehealth service. The program consists of 18 sessions delivered over 6 weeks by a licensed physical therapist (PT) and a respiratory therapist (RT). The aims of the telehealth PR are to improve exercise tolerance, reduce dyspnea and fatigue, improve QOL, improve accessibility, and decrease costs and transportation burdens for patients with COPD. The program was developed, implemented and delivered by an interdisciplinary team, including a pulmonologist, PT, RT, physiatrist, and nonclinical supporting staff.

Patient Assessment

To be eligible to participate in the program the patient must: (1) have a forced expiratory volume (FEV1) < 60%; ( 2) be medically stable and be receiving optimal medical management; (3) have no severe cognitive impairments; (4) be able to use a computer and e-mail; (5) be able to ambulate with or without a walking device; (6) be willing to enroll in a smoking cessation program or to stop smoking; (7) be willing to participate without prolonged interruption; and (8) have all visual and auditory impairments corrected with medical devices.

After referral and enrollment, patients receive medical and physical examinations by the PR team, including a pulmonologist, a PT, and a RT, to ensure that the patients are medically stable to undergo rehabilitation and to develop a tailored exercise program while being mindful of the comorbidities, limitations, and precautions, (eg, loss of balance, risk of fall, limited range of motion). The preprogram assessment includes a pulmonary function test, arterial blood gas test, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Modified Medical Research Council Scale, St. George Respiratory Questionnaire, the COPD Assessment Test, Patient Health Questionnaire-9,Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Katz Index of Independence of Activities of Daily Living, medications and inhaler use, oxygen use, breathing pattern, coughing, 6-minute walk test, Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale, grip strength, 5 Times Sit to Stand Test, manual muscle test, gait measure, Timed Up & Go test, clinical balance tests, range of motion, flexibility, sensation, pain, and fall history.18-32 Educational needs (eg, respiratory hygiene, nutrition, infection control, sleep, disease/symptom management) also are evaluated.

This thorough assessment is performed in a face-to-face outpatient visit. During the program participation, a physiatrist may be consulted for additional needs (eg, wheelchair assessment, home safety evaluation/ modifications, and mobility/disability issues). After completing the 6-week program, patients are scheduled for the postprogram evaluation in a face-to-face outpatient visit with the clinicians.

Equipment

Both clinician and the patient are equipped with a computer with Wi-Fi connectivity, a webcam, and a microphone. Patients are provided an exercise pictorial booklet, an exercise compact disk (audio and video), small exercise apparatuses (eg, assorted colors of resistance bands, hand grip exerciser, hand putty, ergometer, harmonica, and pedometer), incentive spirometer, pulse oximeter, cough assistive device (as needed), blood pressure monitor, COPD information booklets, and a diary to use at home during the program.33

Technology Preparation

Prior to starting the telehealth program, the patient is contacted 1 or 2 days before the first session for technical preparation and familiarization of the VA telehealth connection process. Either the PT or RT provides step-by-step instructions for the patient to practice connecting through VVC during this preparatory phone call. The patient also practices using the computer webcam, speaker, and microphone; checks the telehealth scheduling e-mail; and learns how to solve possible common technical issues (eg, adjusting volume and position of webcam). The patient is asked to set up a table close to the computer and to place all exercise apparatuses and respiratory devices on the table surface.

Program Delivery

A secure online VVC is used for connection during the telehealth session. The patient received an e-mail from the telehealth scheduling system with a link for VVC before each session. During the 6-week program, each telehealth session is conducted by a PT and a RT concurrently for 120 minutes, 3 days per week. The PT provides exercises for the patient to attempt, and the RT provides breathing training and monitoring during the session. After a successful connection to VVC, the therapist verifies the patient’s identity and confirms patient consent for the telehealth session.