User login

Improving Diagnostic Accuracy in Skin of Color Using an Educational Module

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

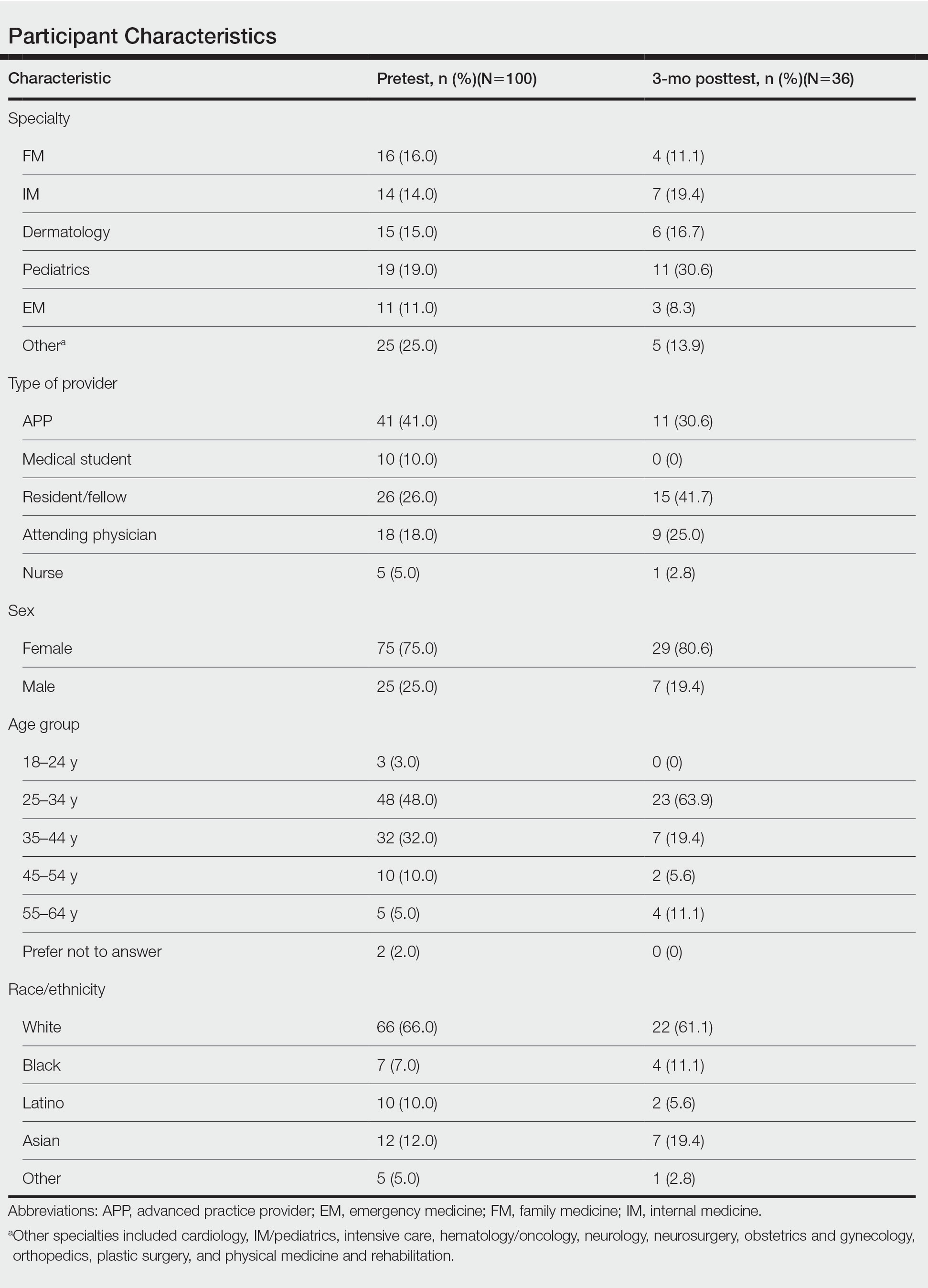

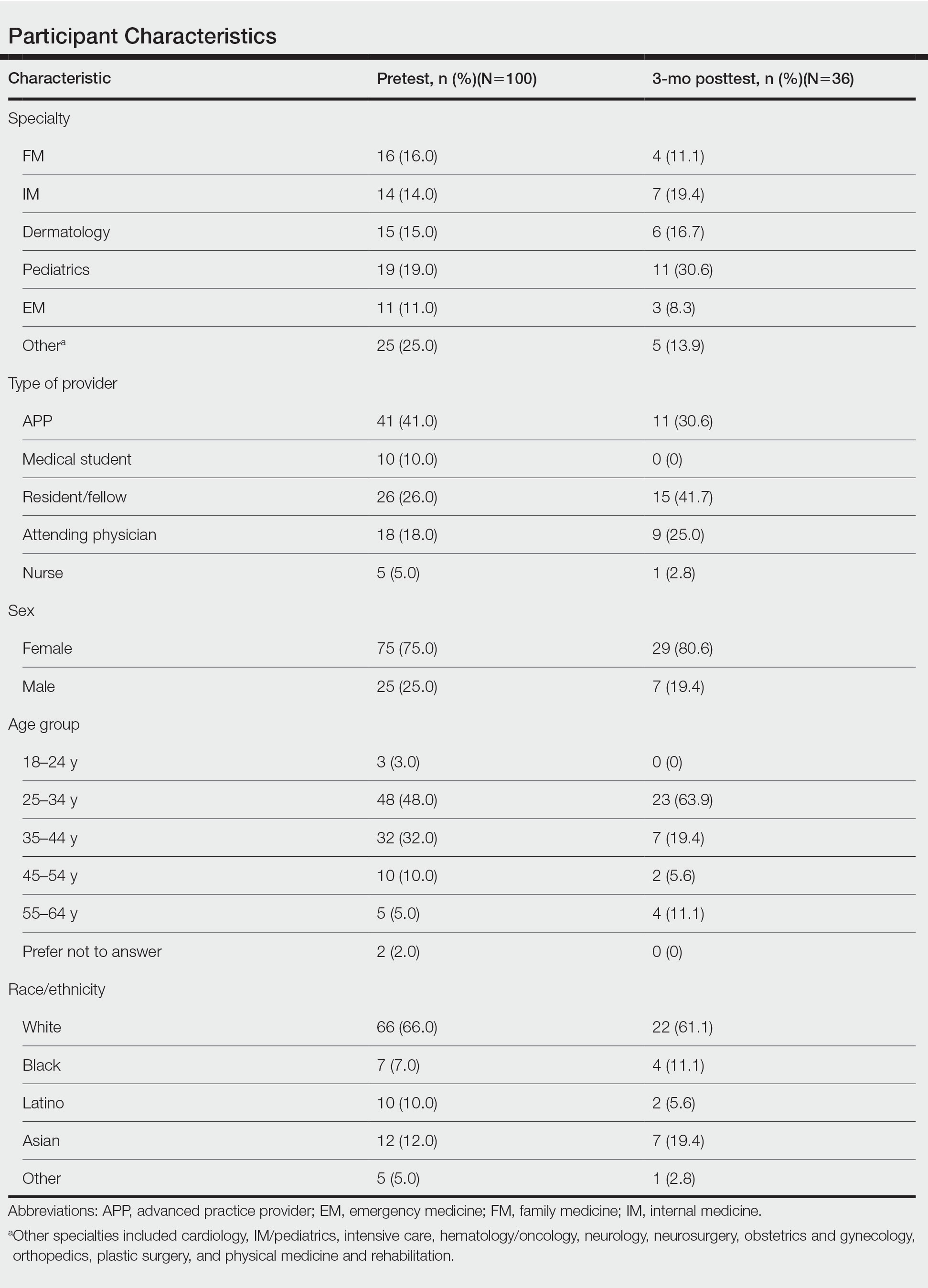

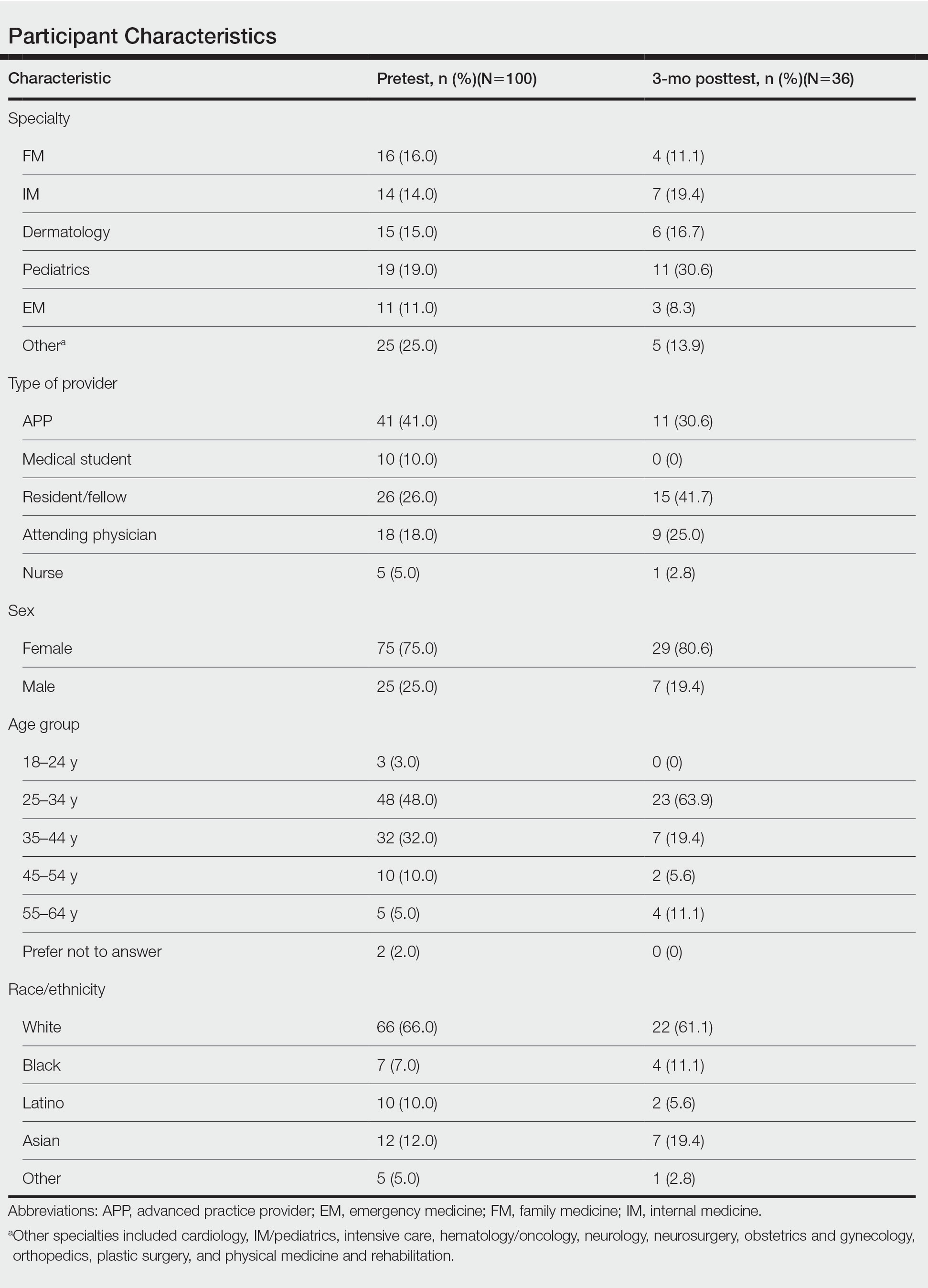

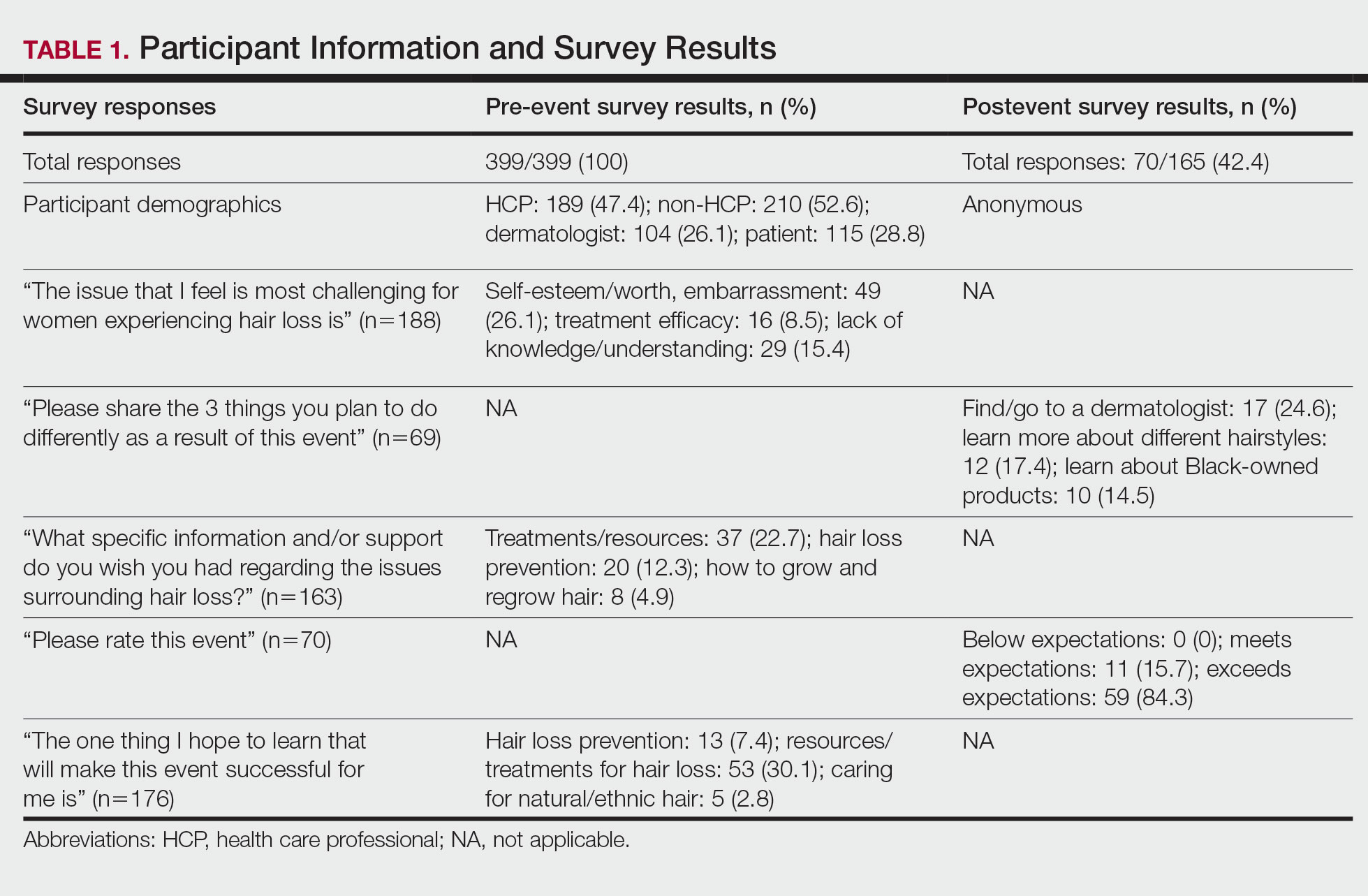

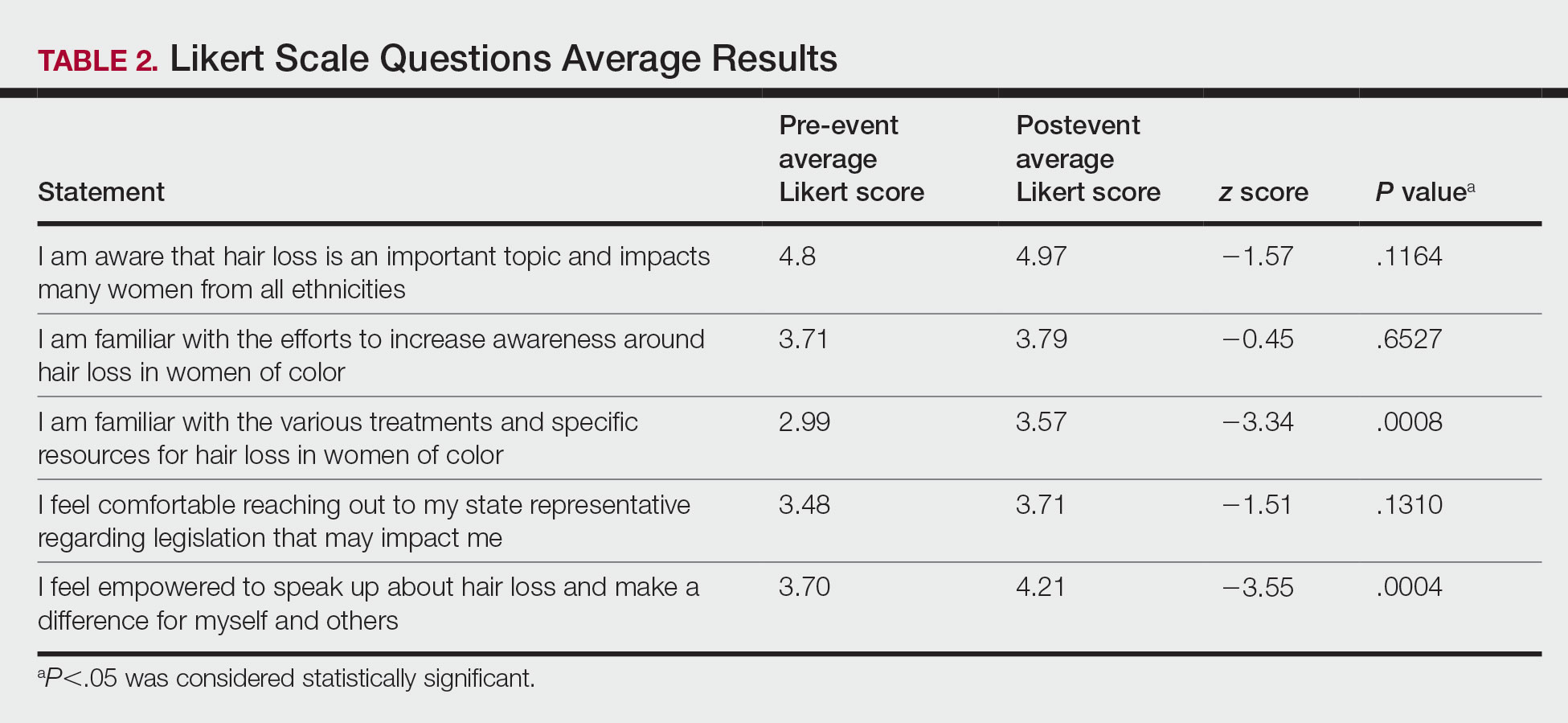

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

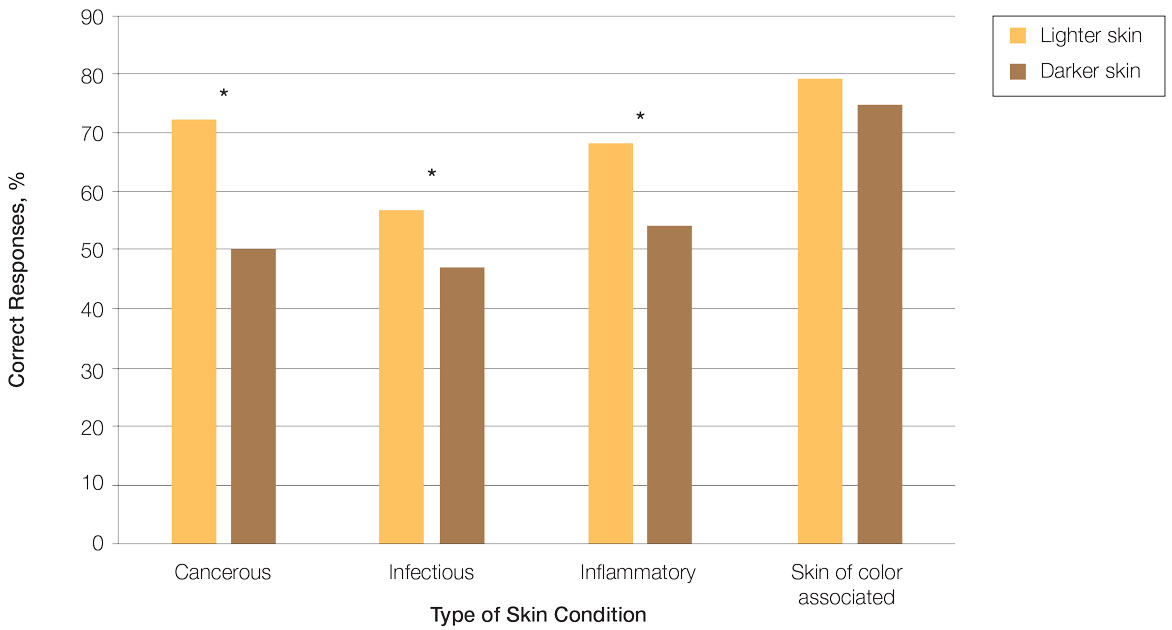

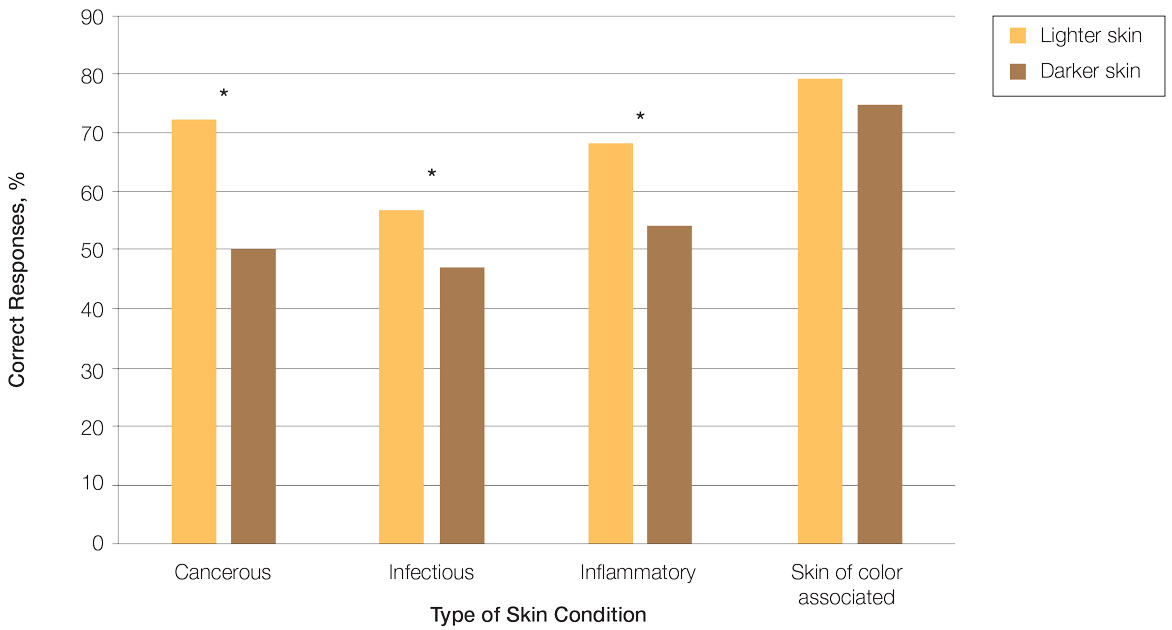

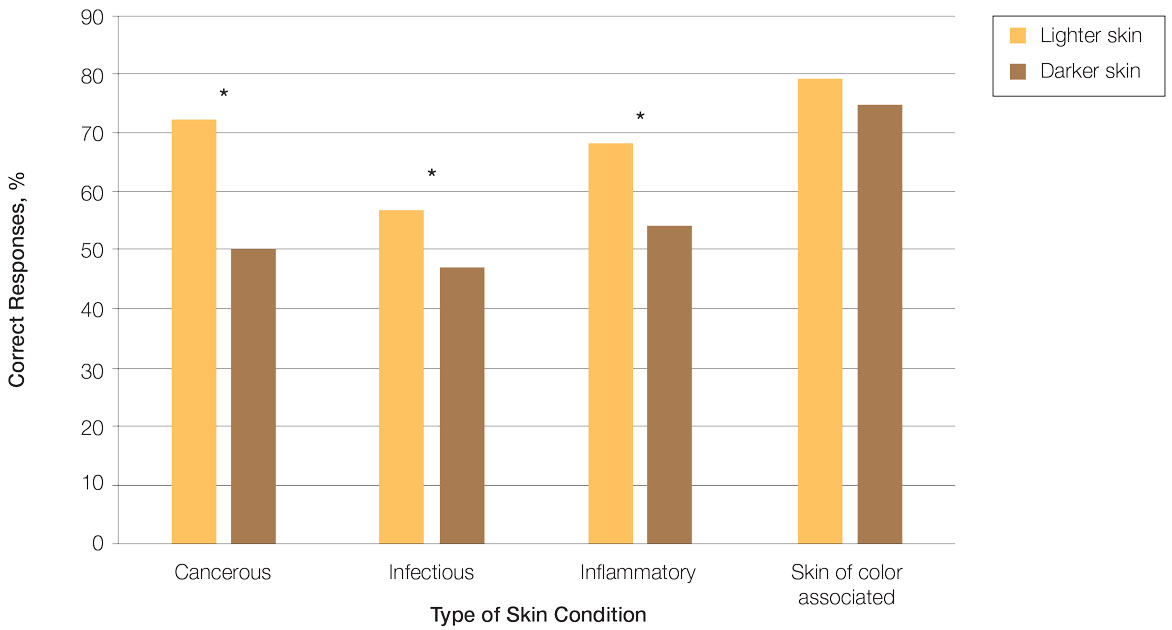

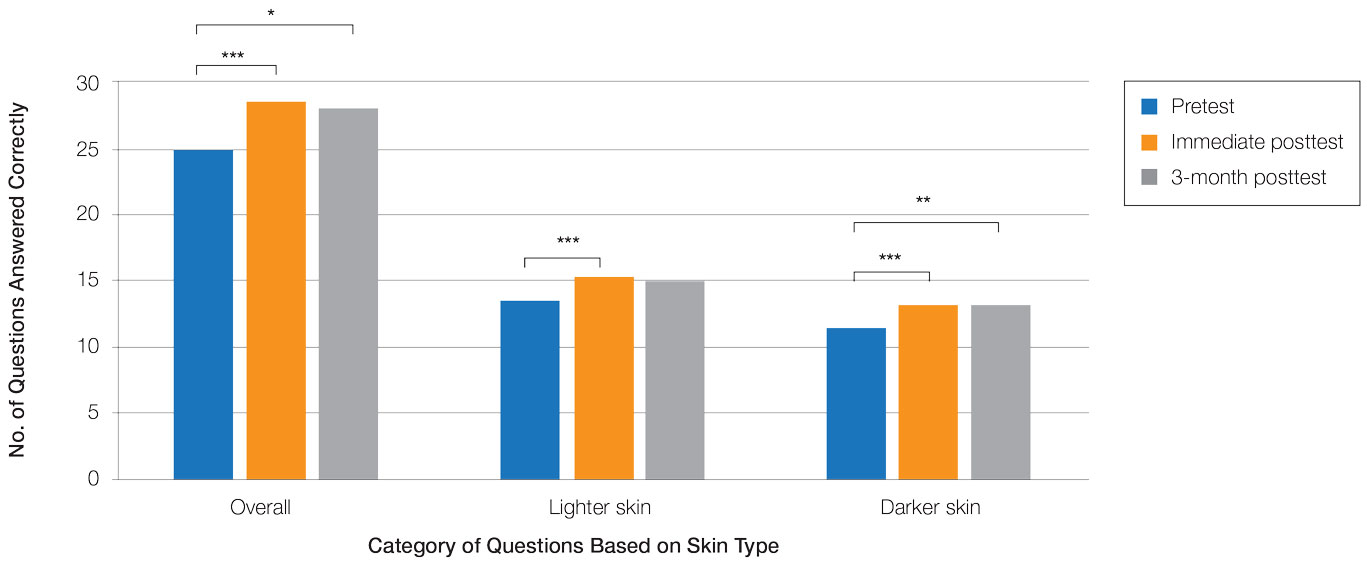

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

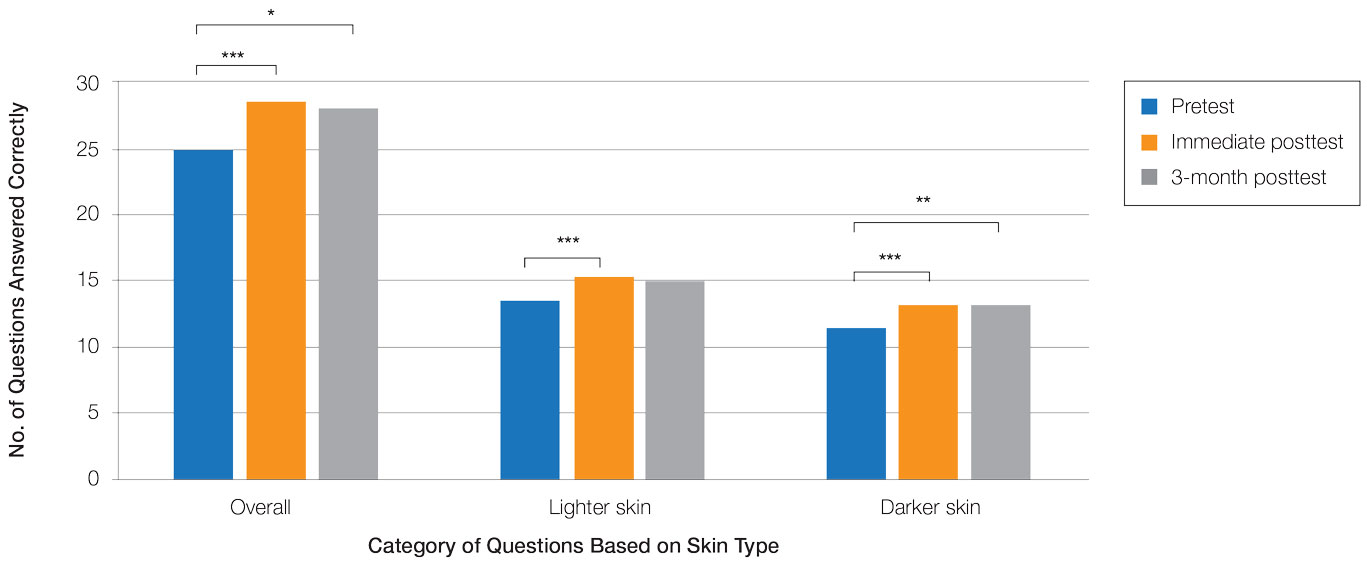

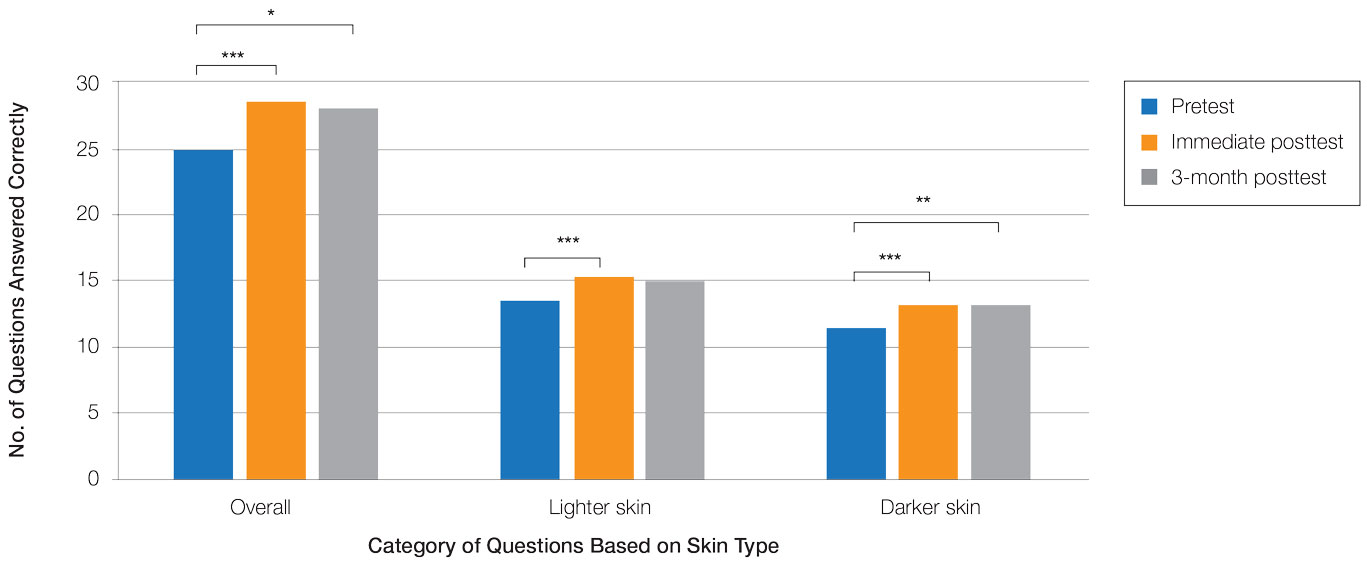

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

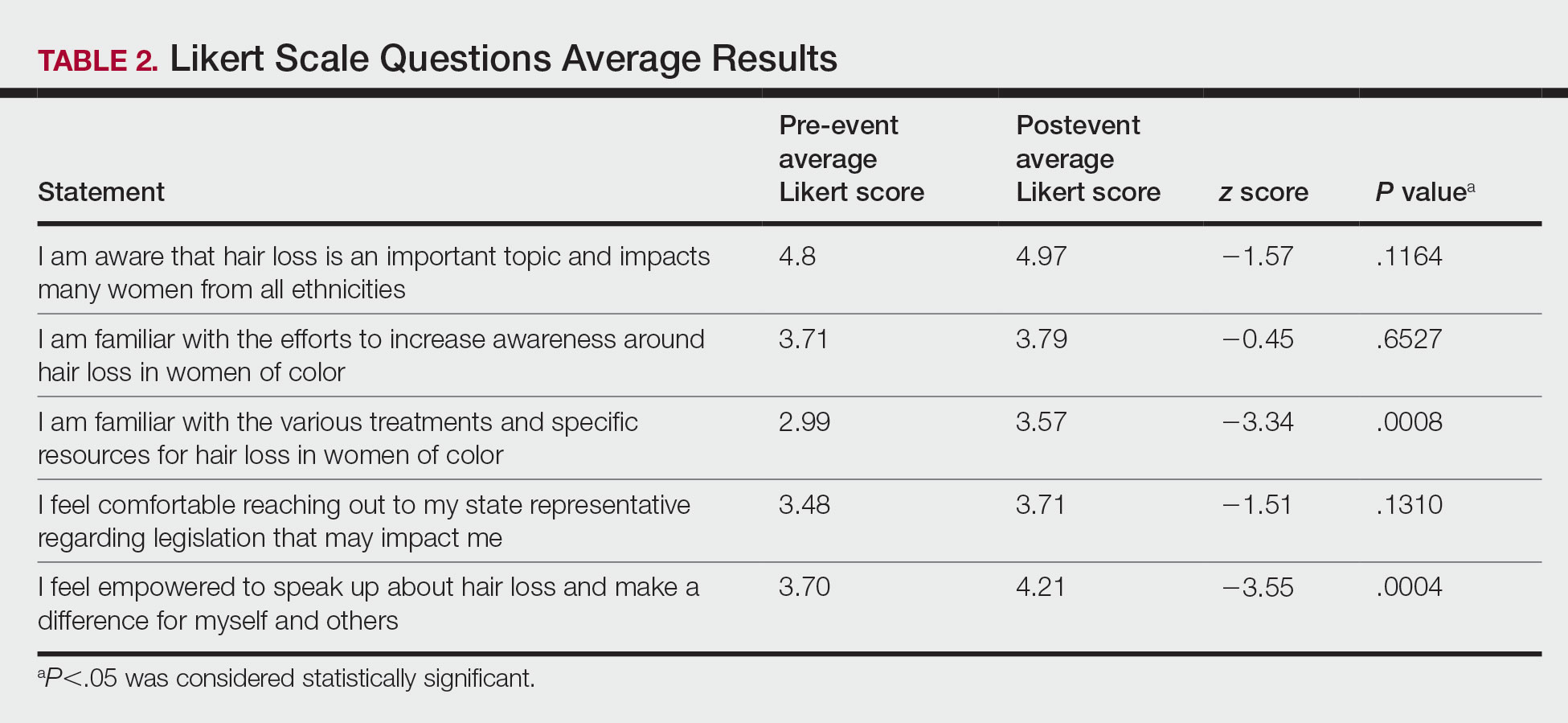

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

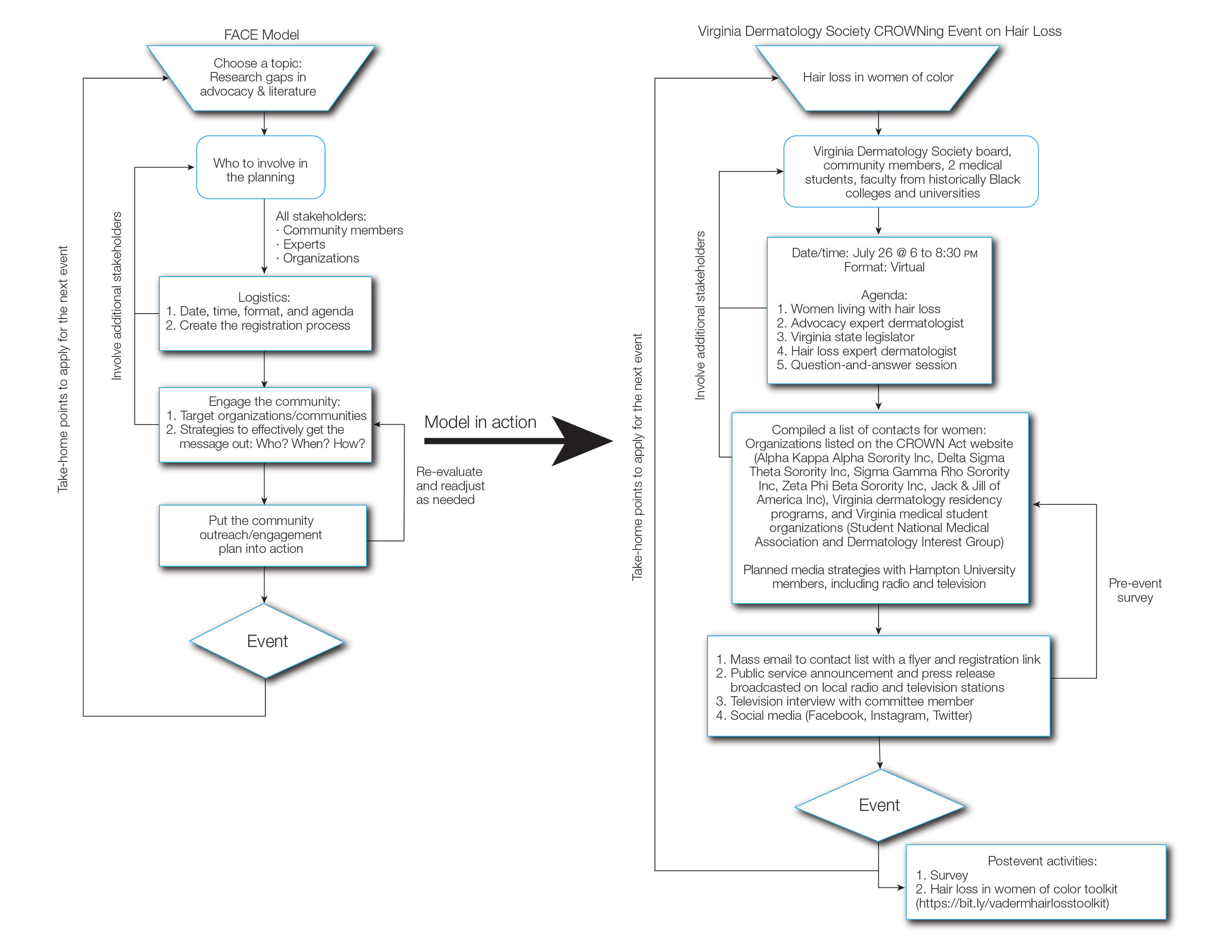

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

Practice Points

- Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when diagnosing conditions in patients with lighter and darker skin, specifically for infectious, cancerous, or inflammatory conditions vs conditions that are preferentially seen in patients with skin of color (SOC).

- A focused educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

Treatment of Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia in Black Patients: A Systematic Review

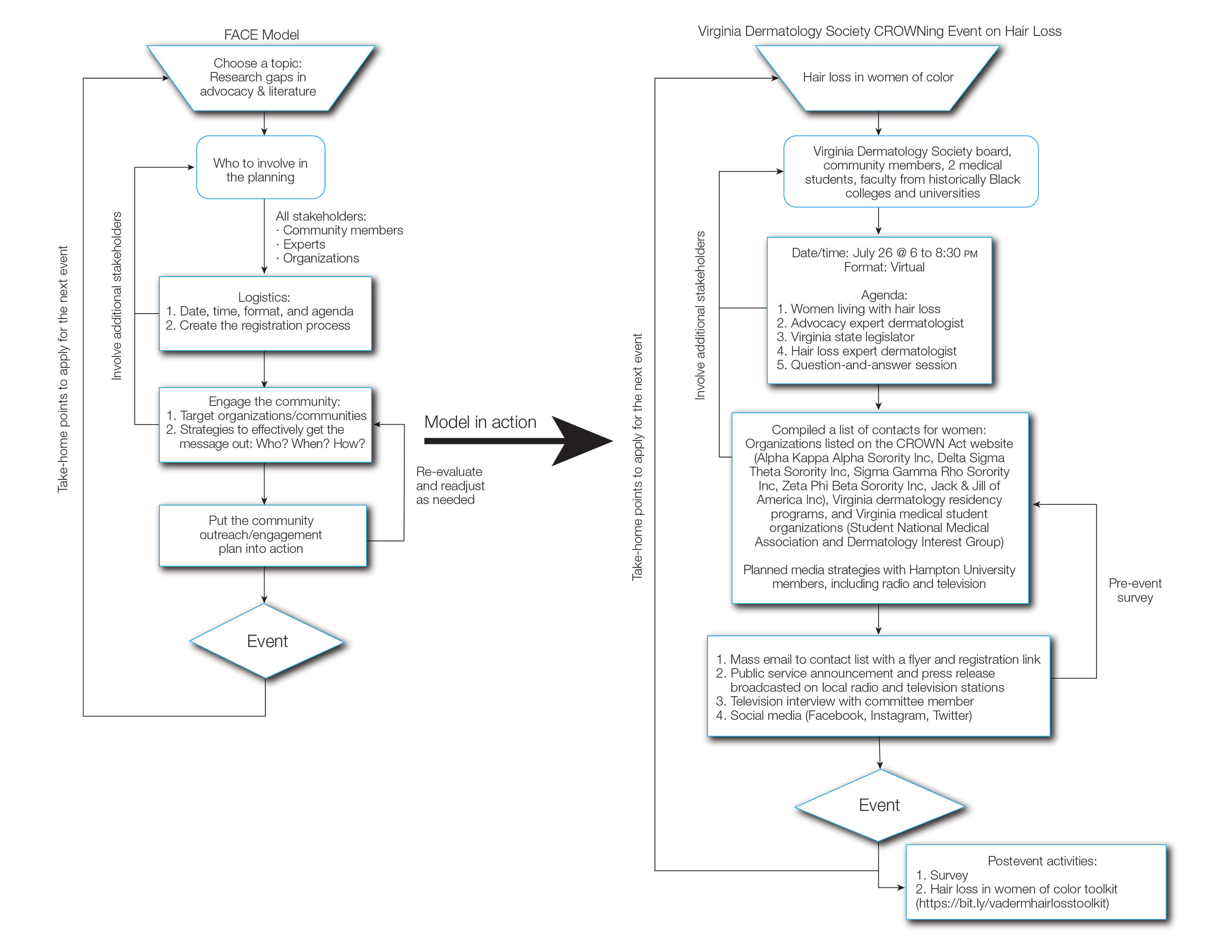

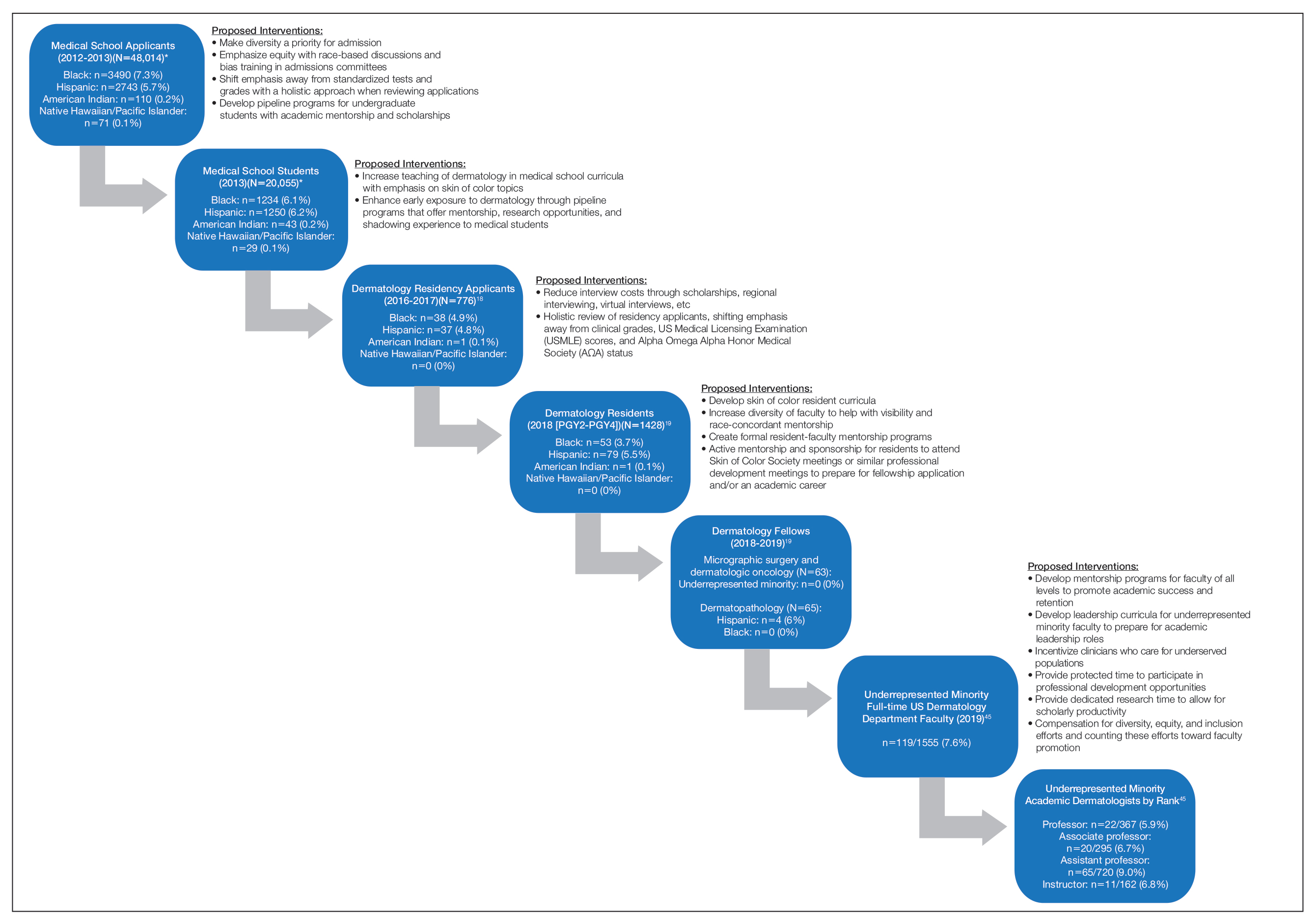

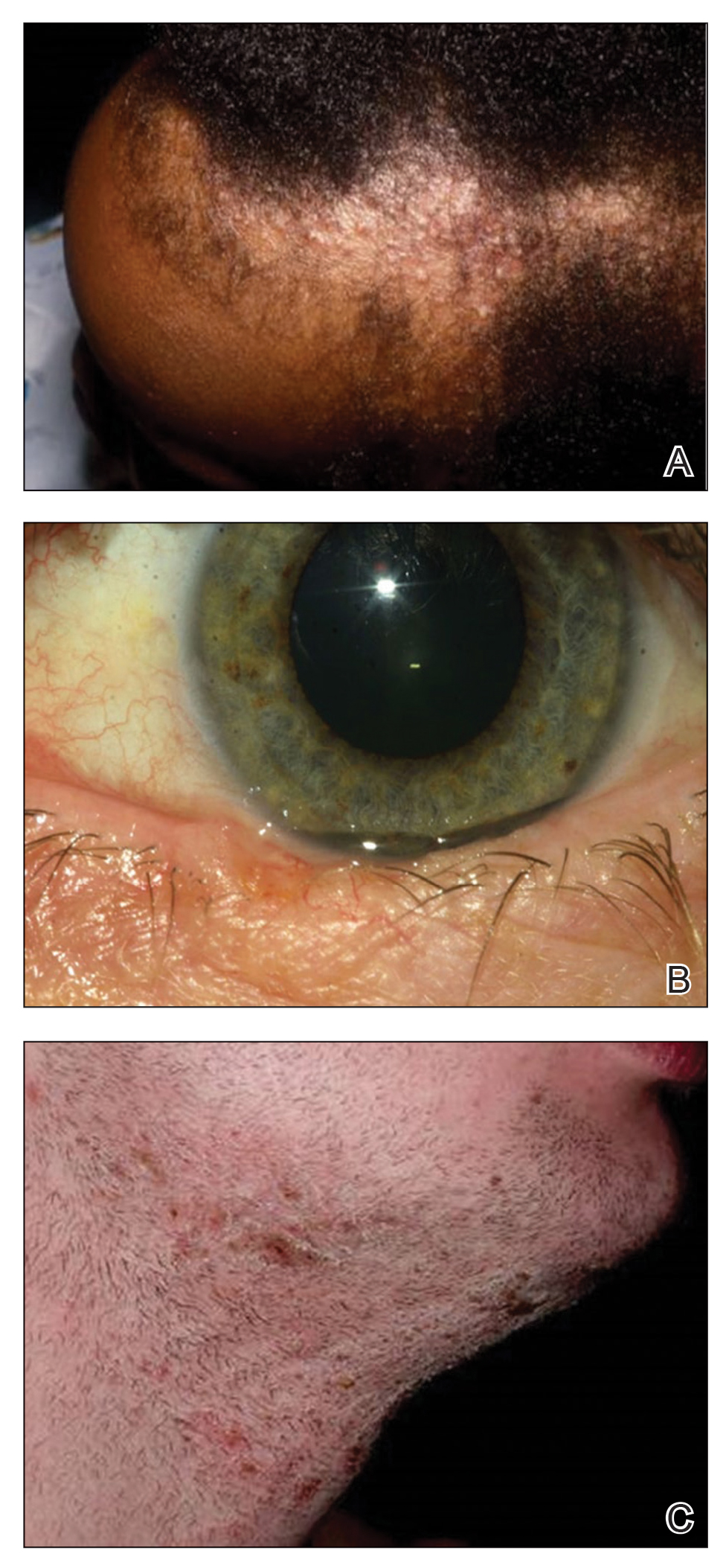

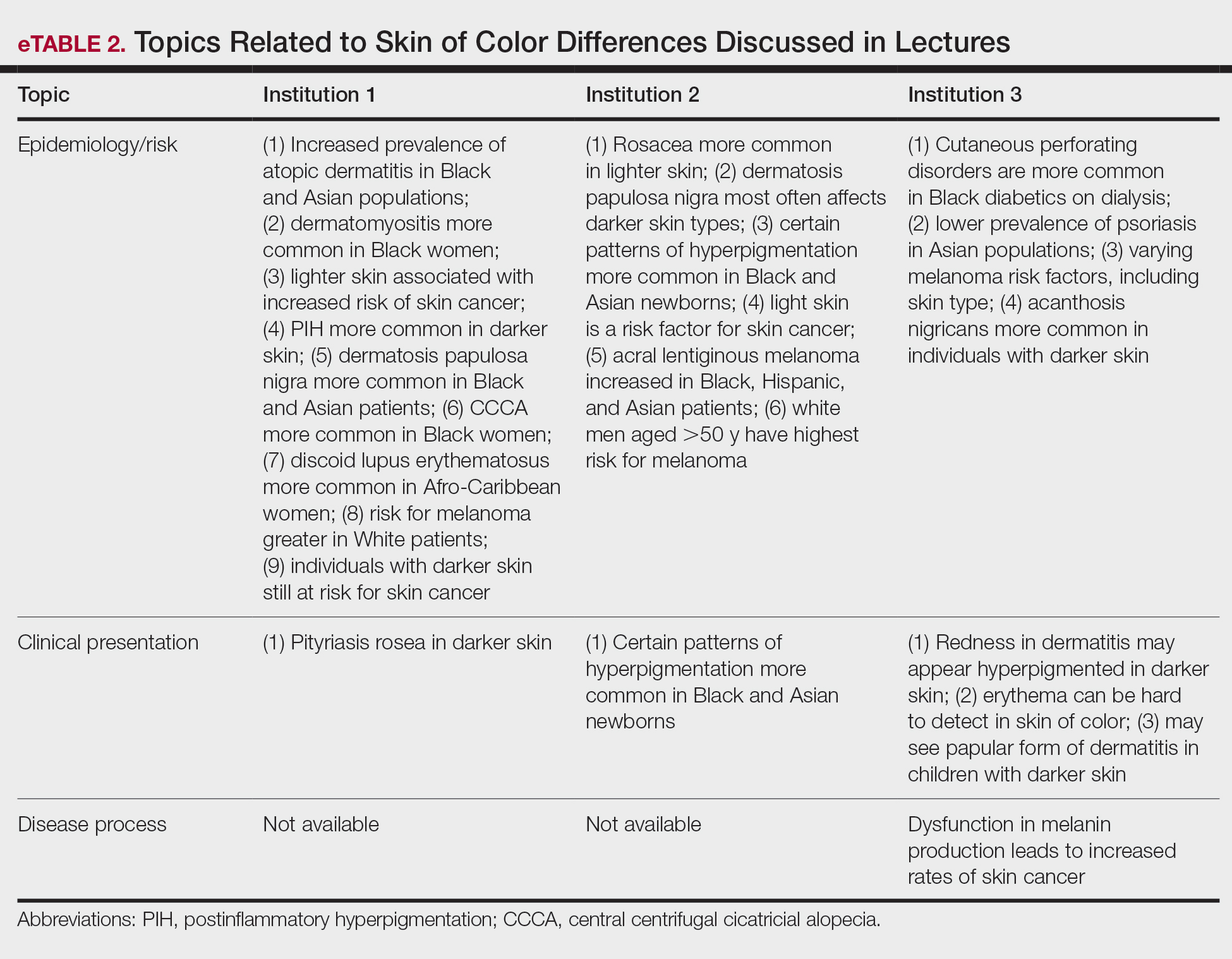

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

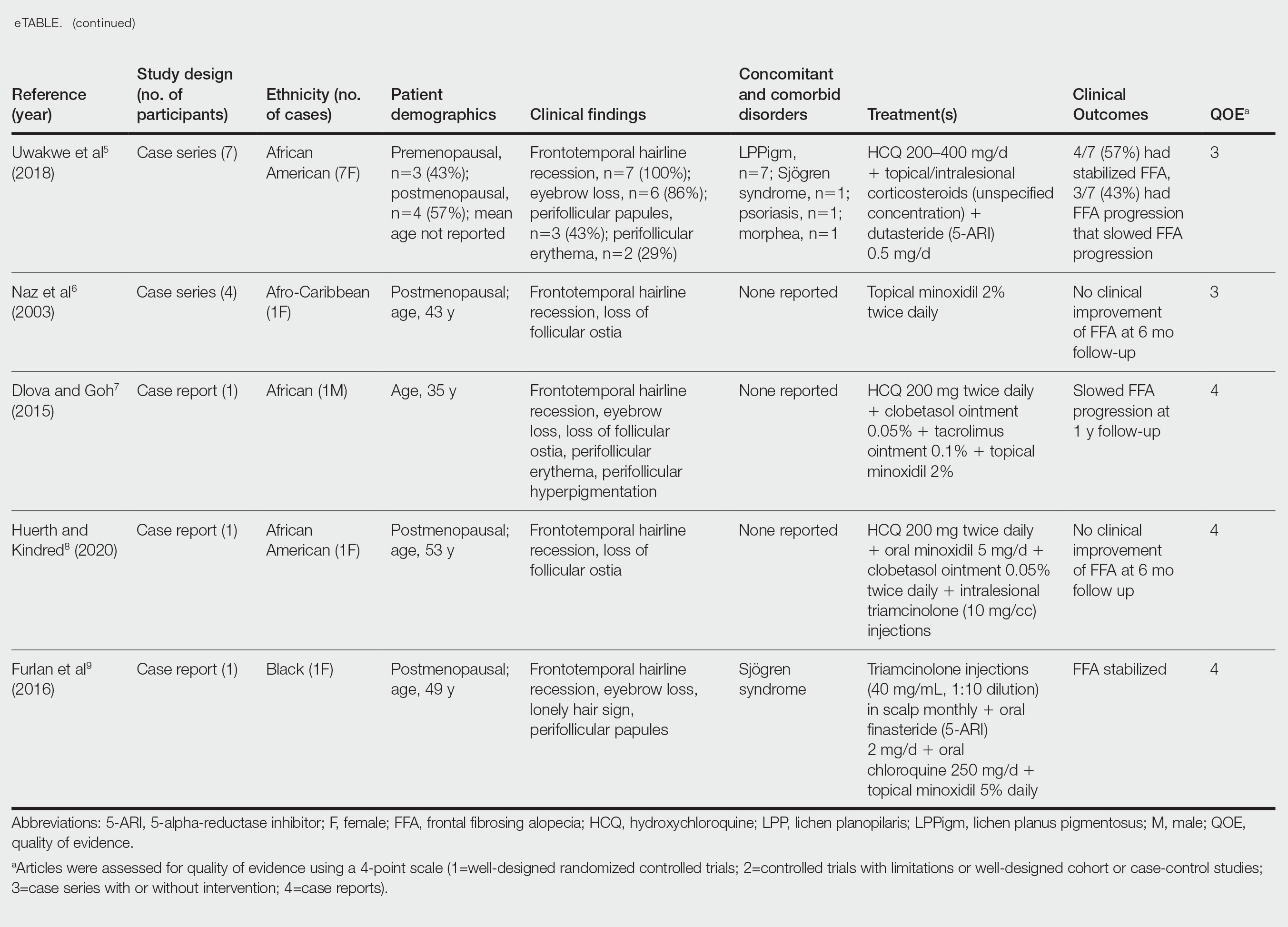

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

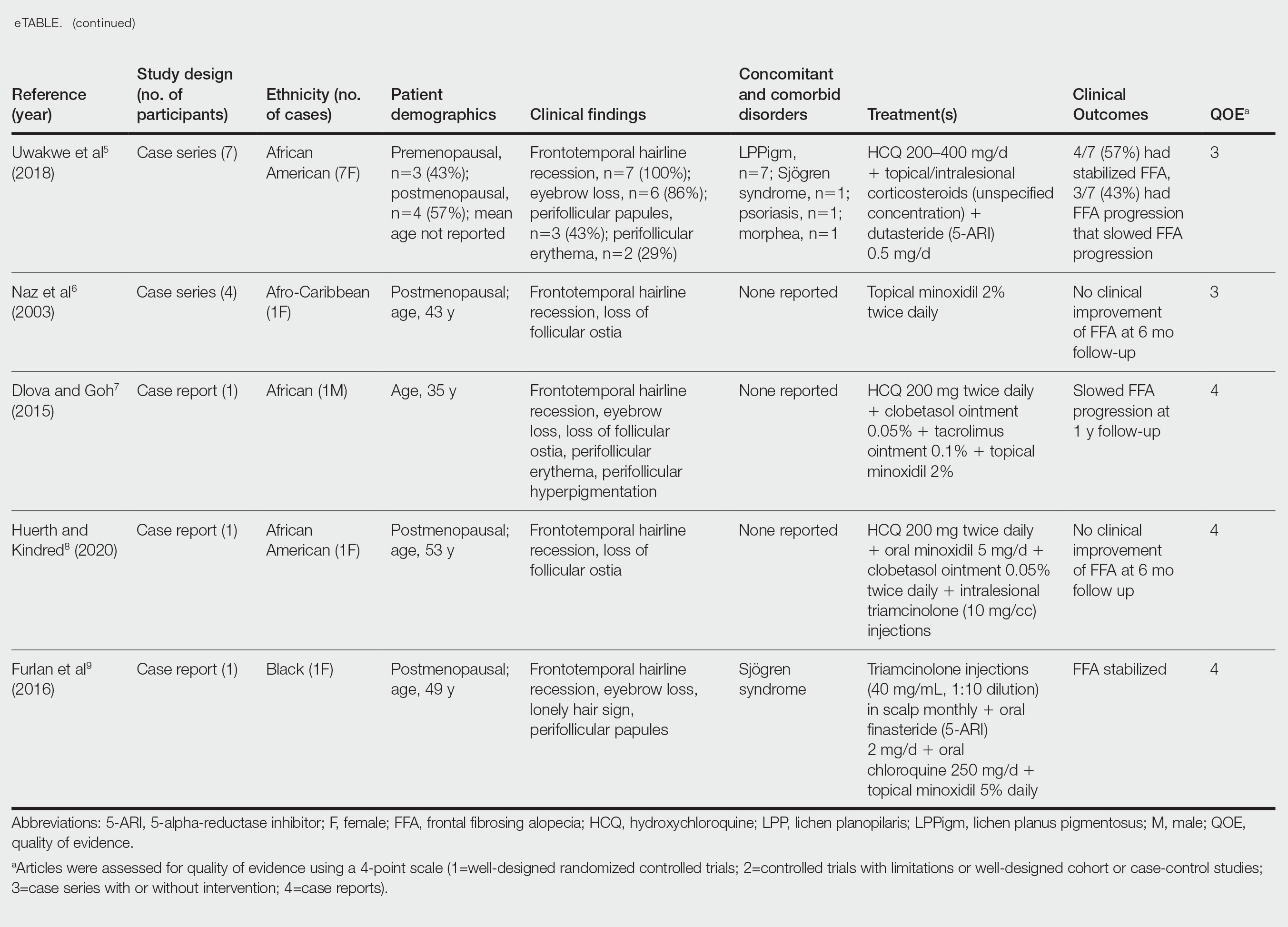

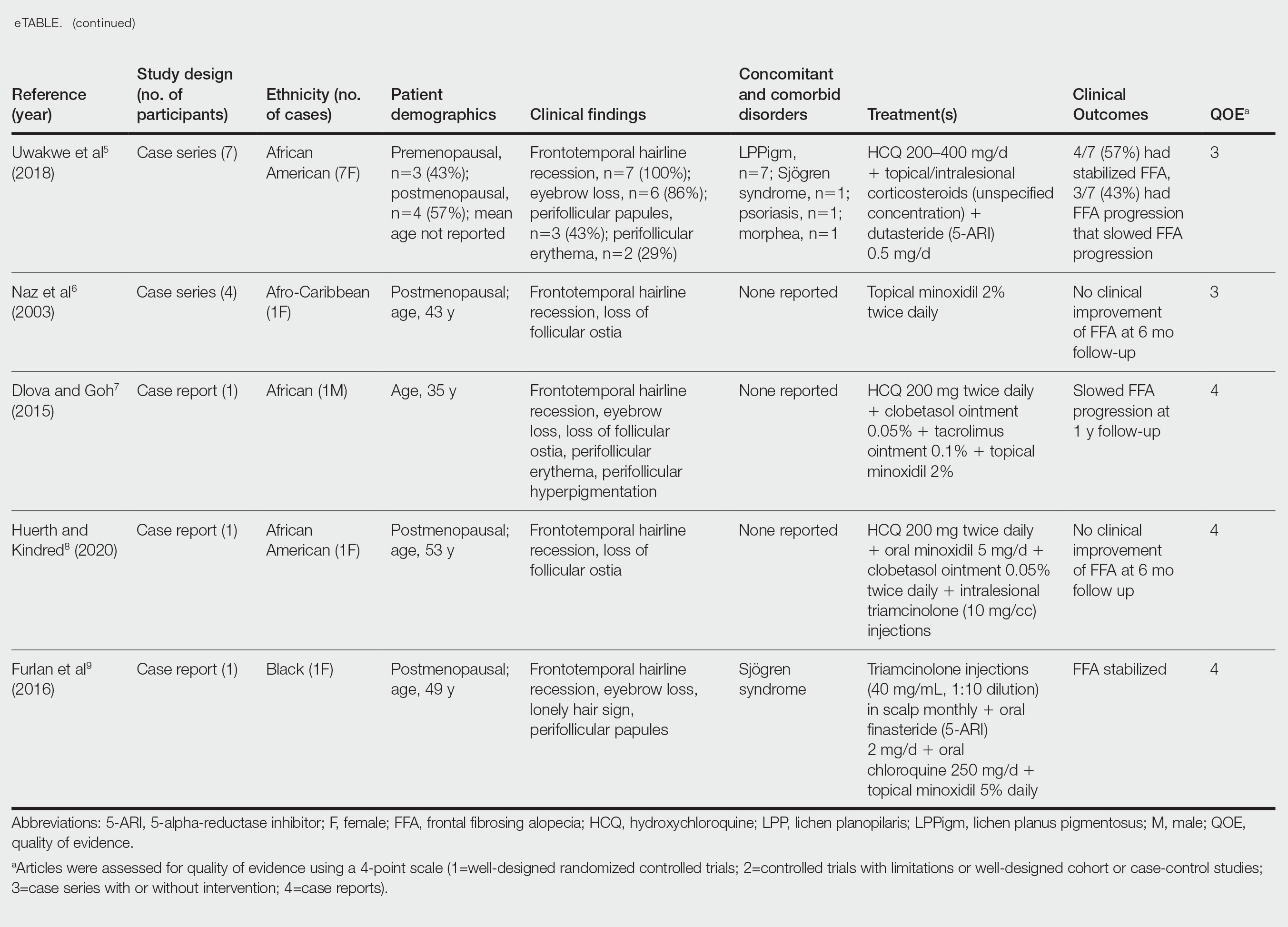

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

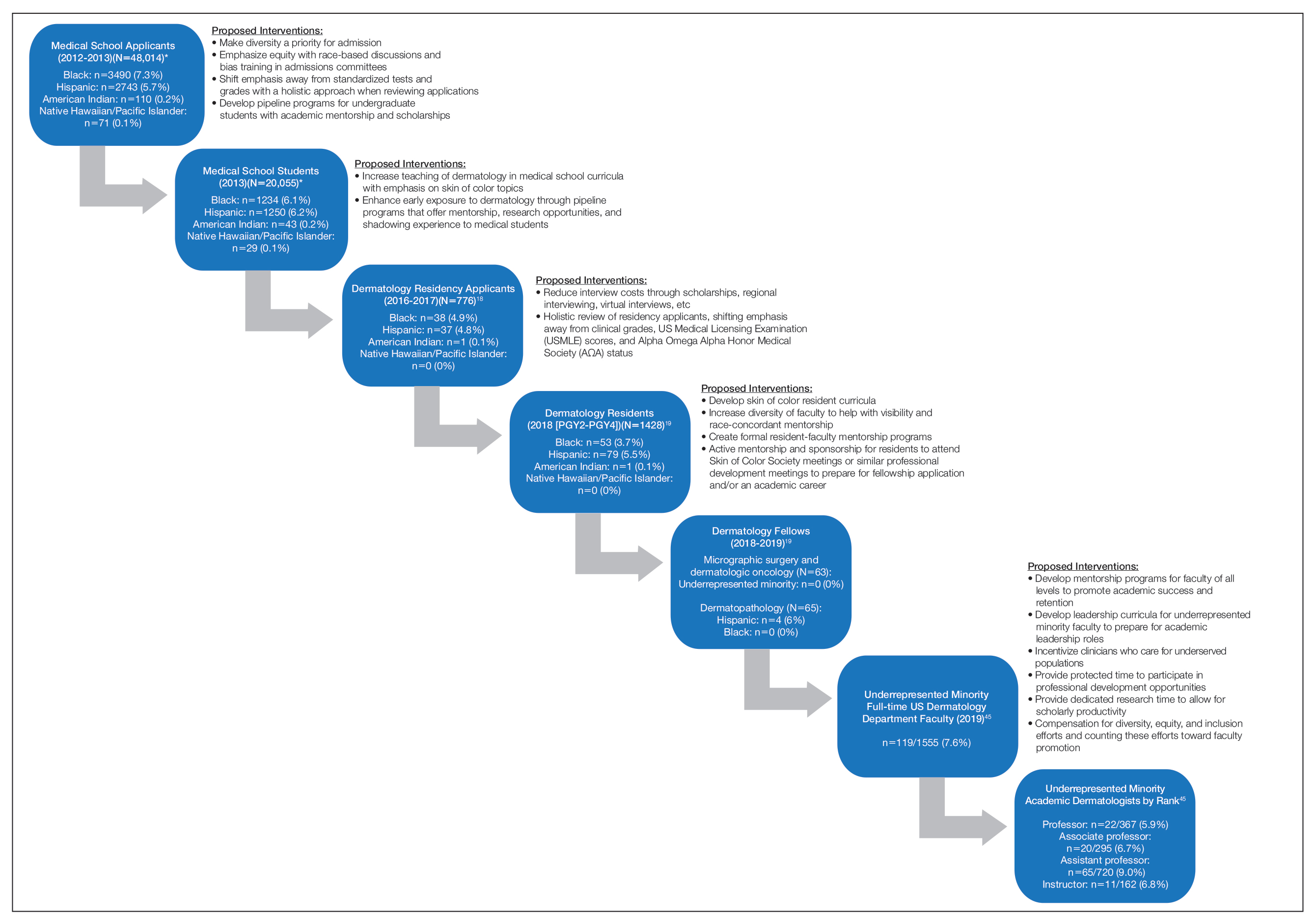

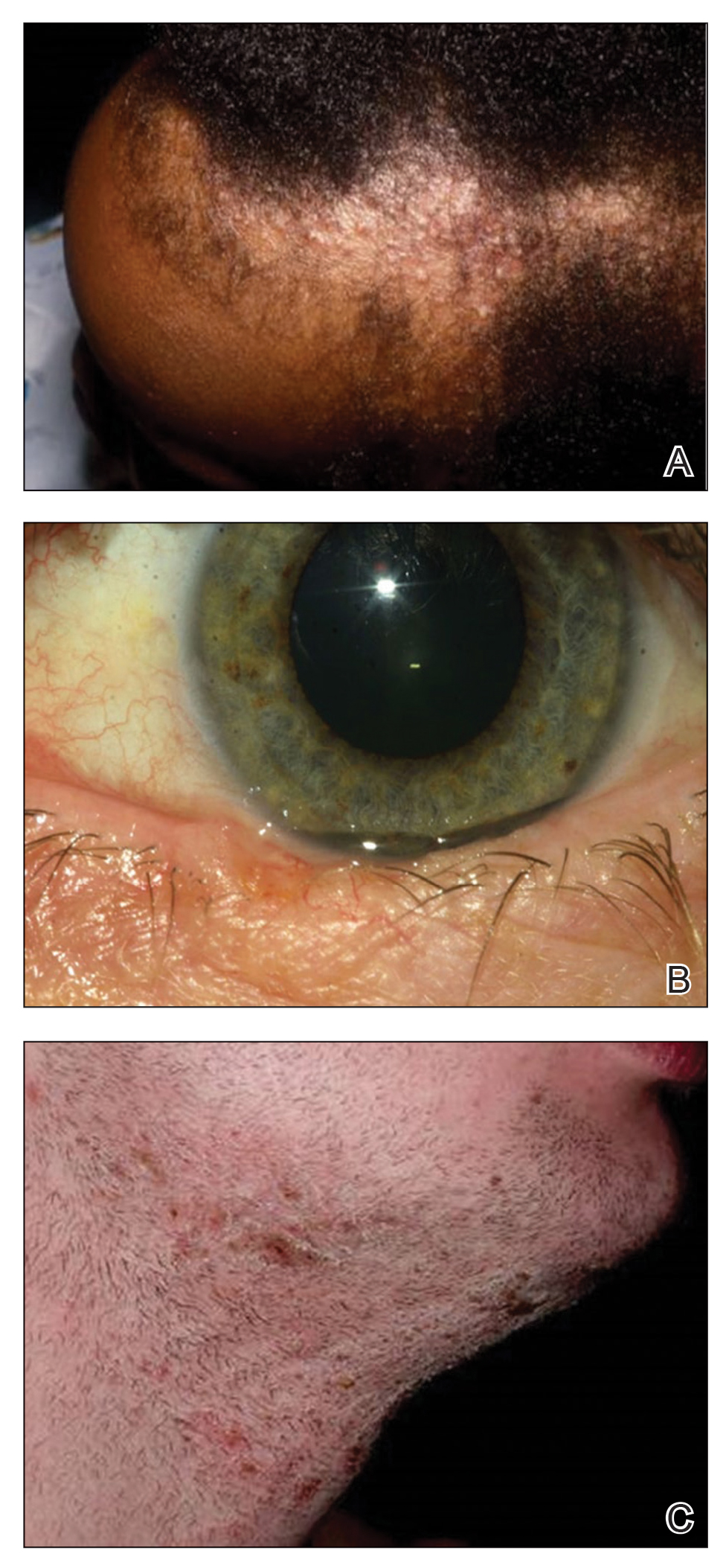

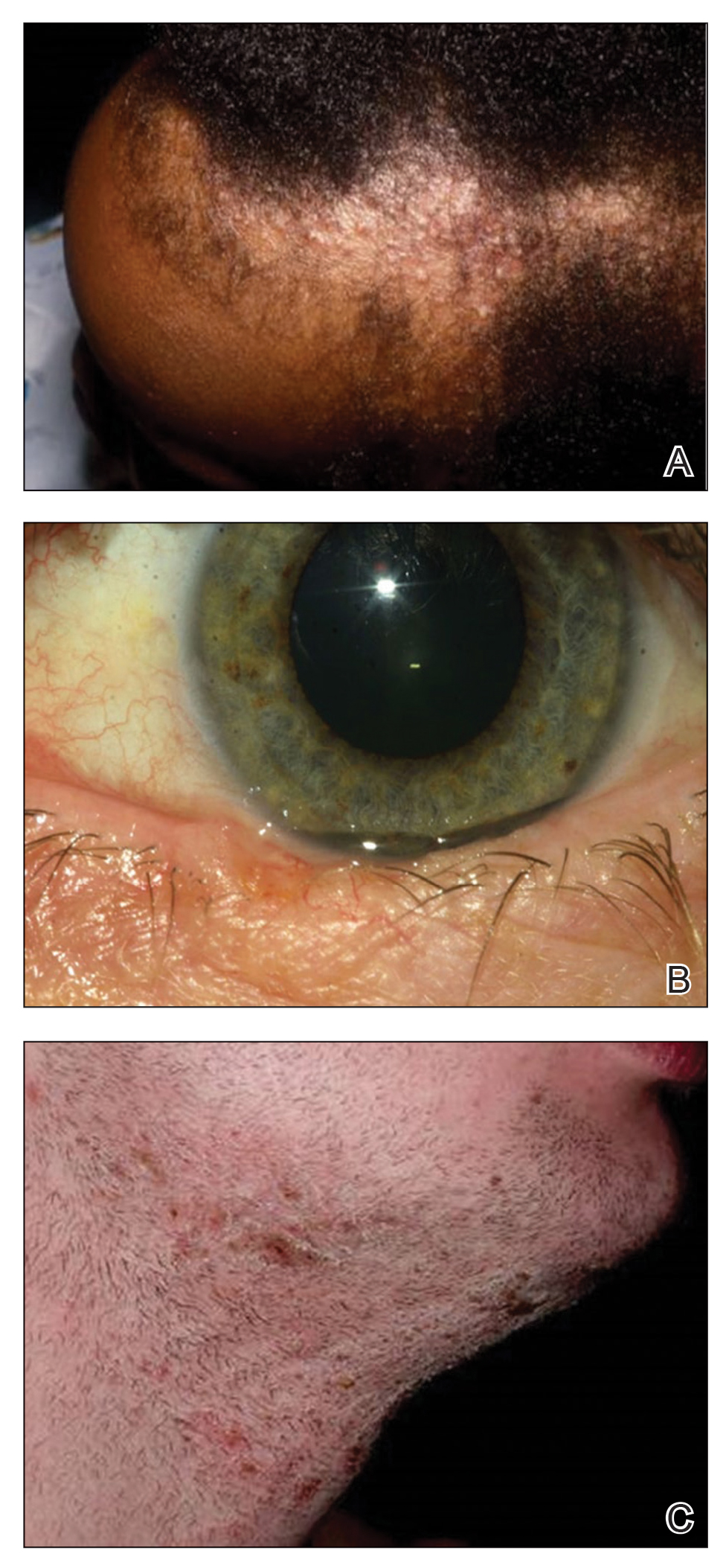

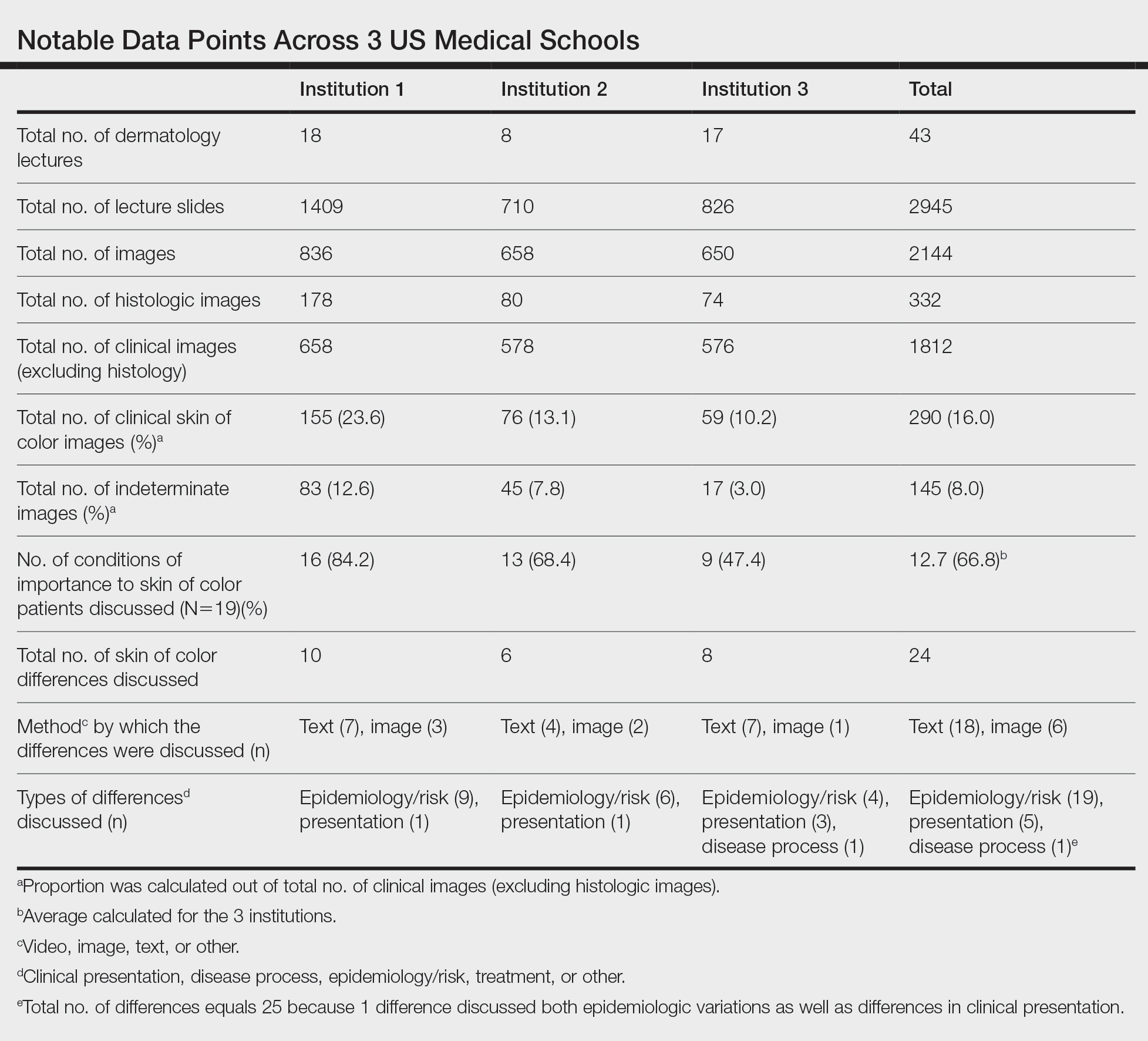

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

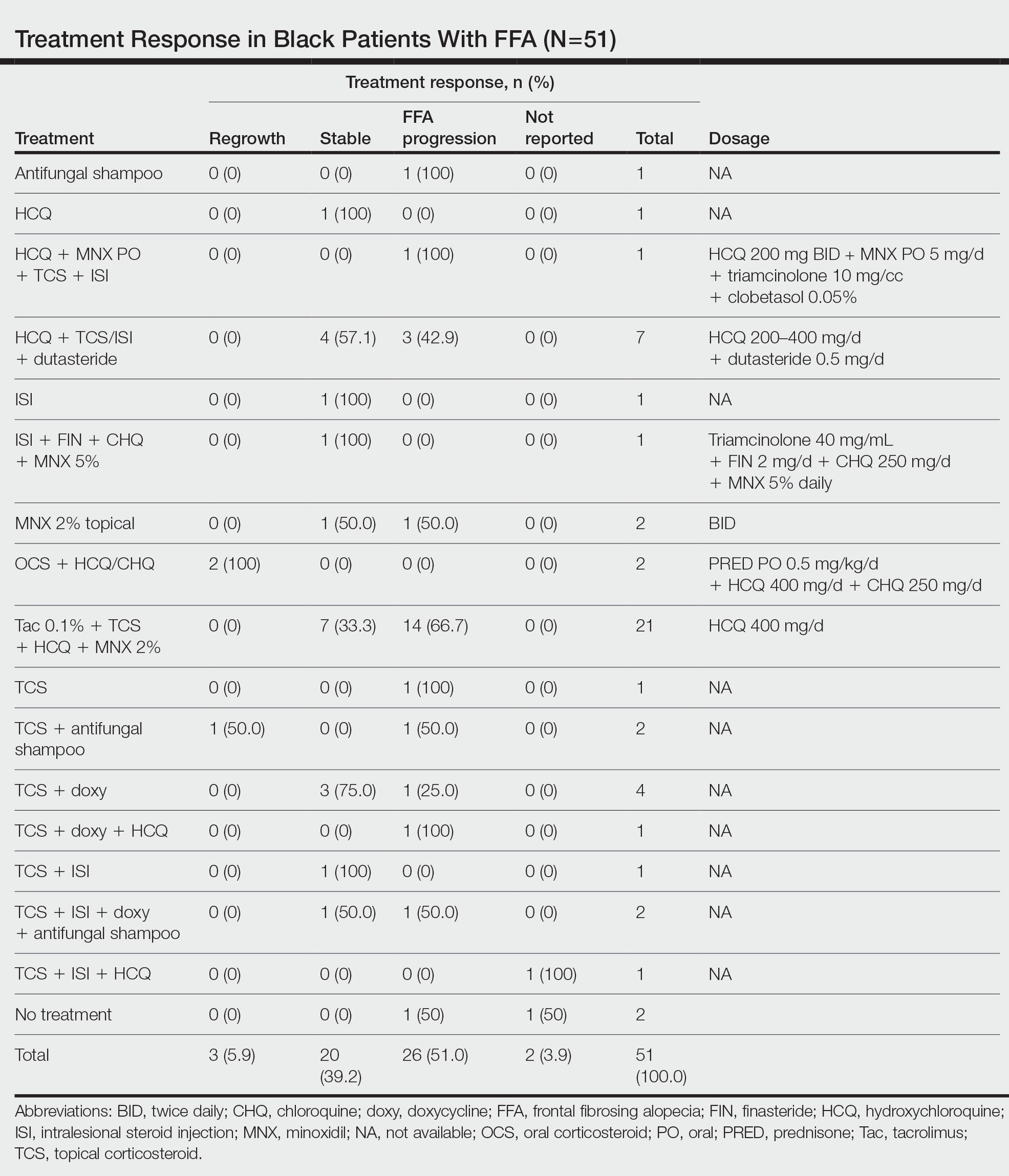

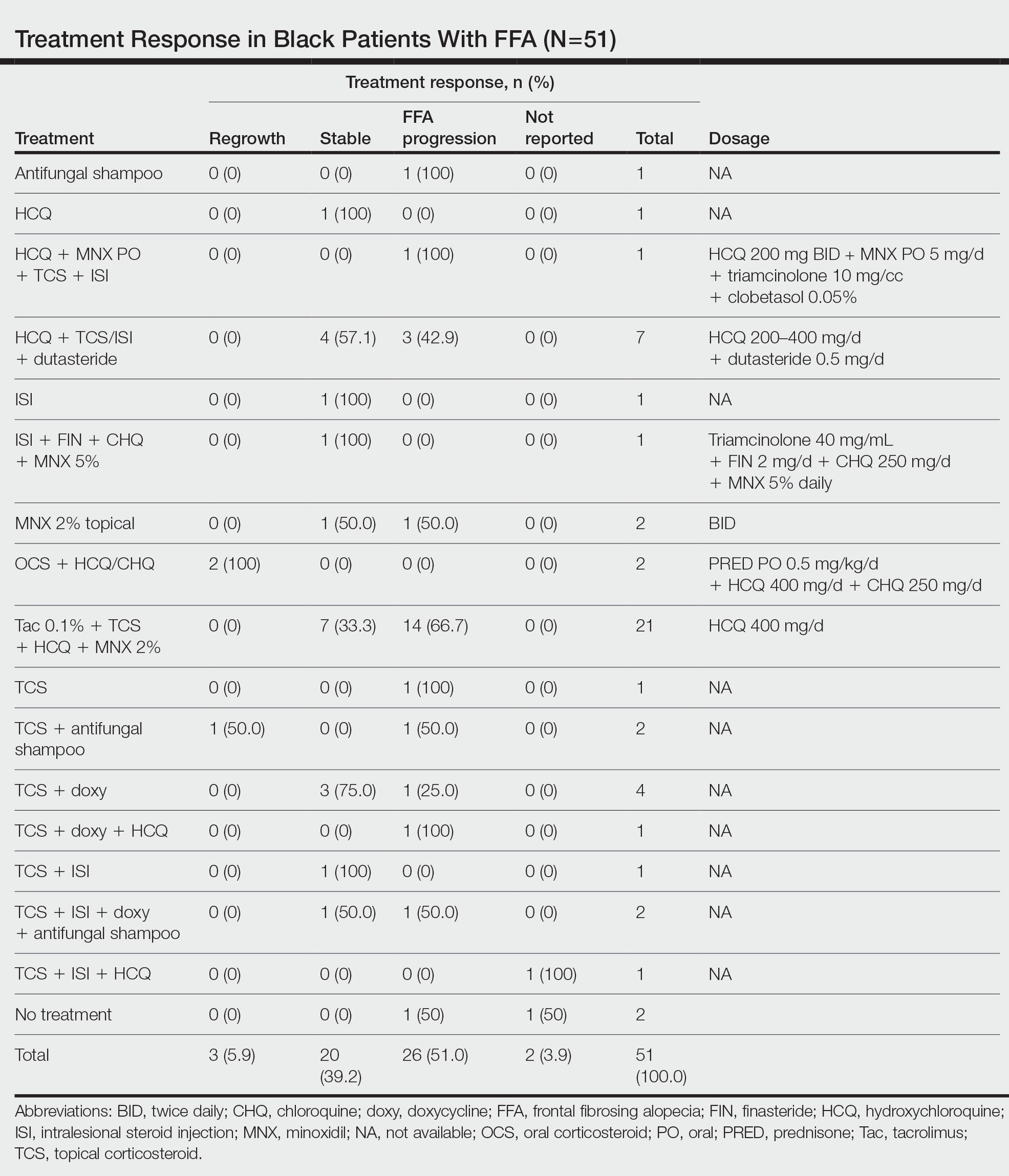

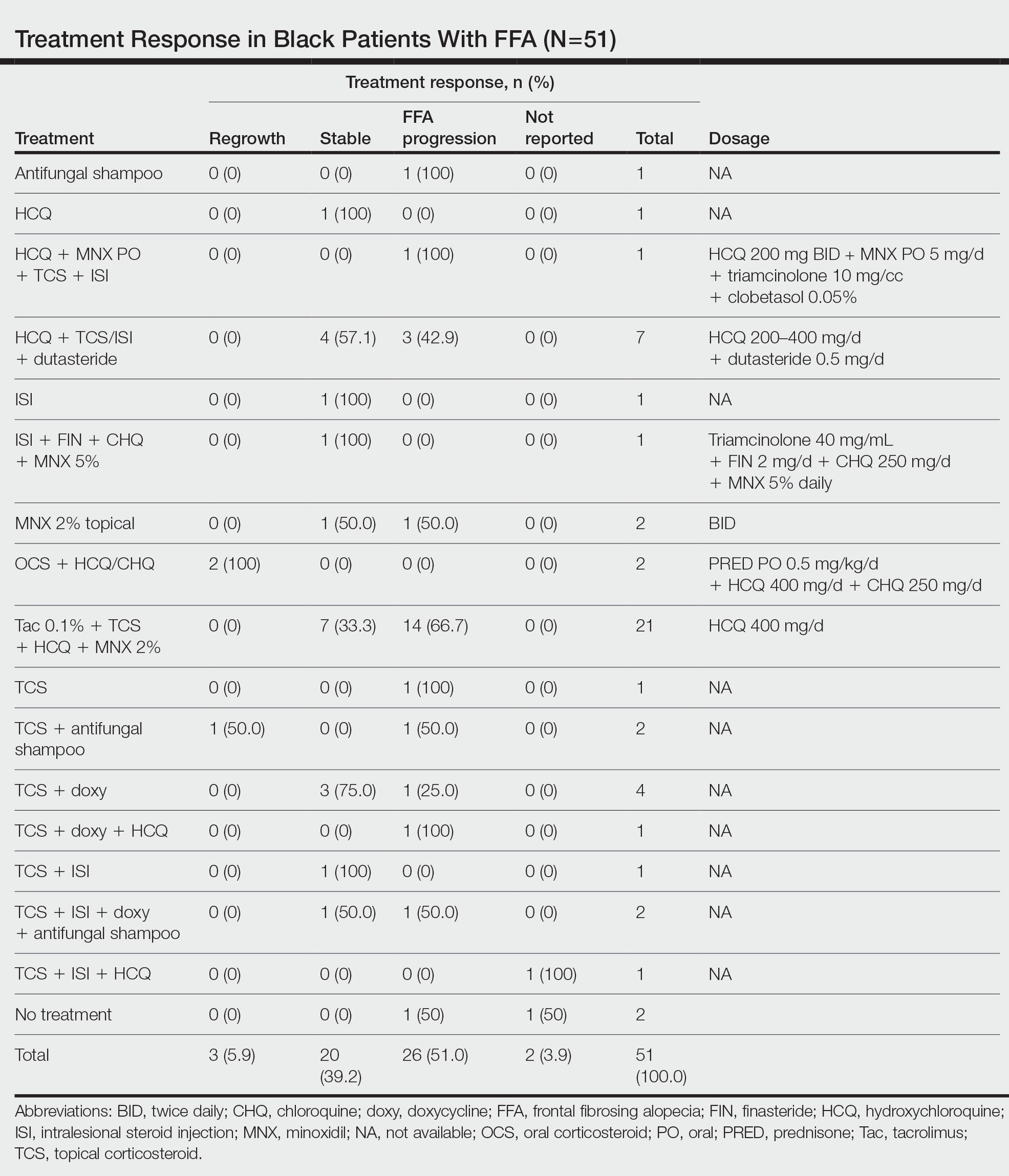

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

- Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:939-941. doi:10.1111/bjd.12424

- Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, et al. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:45-51.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321

- Uwakwe LN, Cardwell LA, Dothard EH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and concomitant lichen planus pigmentosus: a case series of seven African American women. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:397-400.

- Naz E, Vidaurrázaga C, Hernández-Cano N, et al. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:25-27. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01131.x

- Dlova NC, Goh CL. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:81-83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05821.x

- Huerth K, Kindred C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting as androgenetic alopecia in an African American woman. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:794-795. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4682

- Furlan KC, Kakizaki P, Chartuni JC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in association with Sjögren’s syndrome: more than a simple coincidence. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5 suppl 1):14-16. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164526

- Zhang M, Zhang L, Rosman IS, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia demographics: a survey of 29 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:E16-E22.

- MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038

- Starace M, Brandi N, Alessandrini A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case series of 65 patients seen in a single Italian centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:433-438. doi:10.1111/jdv.15372

- Dlova NC. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: is there a link? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:439-442. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11146.x

- Petrof G, Cuell A, Rajkomar VV, et al. Retrospective review of 18 British South Asian women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:490-491. doi:10.1111/ijd.13929

- Mervis JS, Borda LJ, Miteva M. Facial and extrafacial lesions in an ethnically diverse series of 91 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia followed at a single center. Dermatology. 2019;235:112-119. doi:10.1159/000494603

- Valesky EM, Maier MD, Kippenberger S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia - review of recent case reports and case series in PubMed. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. Aug 2018;16:992-999. doi:10.1111/ddg.13601

- Adotama P, Callender V, Kolla A, et al. Comparing the clinical differences in white and black women with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1074-1076. doi:10.1111/bjd.20605

- Miao YJ, Jing J, Du XF, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of disease pathogenesis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:911944. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.911944

- Pirmez R, Duque-Estrada B, Donati A, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of lichen planus pigmentosus in 37 patients with frontal fibrosing alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1387-1390. doi:10.1111/bjd.14722

- Berliner JG, McCalmont TH, Price VH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E26-E27. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.031

- Romiti R, Biancardi Gavioli CF, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings of frontal fibrosing alopecia-associated lichen planus pigmentosus. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:59-63. doi:10.1159/000456038

- Mulinari-Brenner FA, Guilherme MR, Peretti MC, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planus pigmentosus: diagnosis and therapeutic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):79-81. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175833

- Panchaprateep R, Ruxrungtham P, Chancheewa B, et al. Clinical characteristics, trichoscopy, histopathology and treatment outcomes of frontal fibrosing alopecia in an Asian population: a retro-prospective cohort study. J Dermatol. 2020;47:1301-1311. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15517

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in postmenopausal women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:55-60. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.014

- Rokni GR, Emadi SN, Dabbaghzade A, et al. Evaluating the combined efficacy of oral isotretinoin and topical tacrolimus versus oral finasteride and topical tacrolimus in frontal fibrosing alopecia—a randomized controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:613-619. doi:10.1111/jocd.15232

- Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59-66. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8

- Miteva M, Whiting D, Harries M, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in black patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:208-210. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10809.x

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia that primarily affects postmenopausal women. Considered a subtype of lichen planopilaris (LPP), FFA is histologically identical but presents as symmetric frontotemporal hairline recession rather than the multifocal distribution typical of LPP (Figure 1). Patients also may experience symptoms such as itching, facial papules, and eyebrow loss. As a progressive and scarring alopecia, early management of FFA is necessary to prevent permanent hair loss; however, there still are no clear guidelines regarding the efficacy of different treatment options for FFA due to a lack of randomized controlled studies in the literature. Patients with skin of color (SOC) also may have varying responses to treatment, further complicating the establishment of any treatment algorithm. Furthermore, symptoms, clinical findings, and demographics of FFA have been observed to vary across different ethnicities, especially among Black individuals. We conducted a systematic review of the literature on FFA in Black patients, with an analysis of demographics, clinical findings, concomitant skin conditions, treatments given, and treatment responses.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted of studies investigating FFA in patients with SOC from January 1, 2000, through November 30, 2020, using the terms frontal fibrosing alopecia, ethnicity, African, Black, Asian, Indian, Hispanic, and Latino. Articles were included if they were available in English and discussed treatment and clinical outcomes of FFA in Black individuals. The reference lists of included studies also were reviewed. Articles were assessed for quality of evidence using a 4-point scale (1=well-designed randomized controlled trials; 2=controlled trials with limitations or well-designed cohort or case-control studies; 3=case series with or without intervention; 4=case reports). Variables related to study type, patient demographics, treatments, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

Of the 69 search results, 8 studies—2 retrospective cohort studies, 3 case series, and 3 case reports—describing 51 Black individuals with FFA were included in our review (eTable). Of these, 49 (96.1%) were female and 2 (3.9%) were male. Of the 45 females with data available for menopausal status, 24 (53.3%) were premenopausal and 21 (46.7%) were postmenopausal; data were not available for 4 females. Patients identified as African or African American in 27 (52.9%) cases, South African in 19 (37.3%), Black in 3 (5.9%), Indian in 1 (2.0%), and Afro-Caribbean in 1 (2.0%). The average age of FFA onset was 43.8 years in females (raw data available in 24 patients) and 35 years in males (raw data available in 2 patients). A family history of hair loss was reported in 15.7% (8/51) of patients.

Involved areas of hair loss included the frontotemporal hairline (51/51 [100%]), eyebrows (32/51 [62.7%]), limbs (4/51 [7.8%]), occiput (4/51 [7.8%]), facial hair (2/51 [3.9%]), vertex scalp (1/51 [2.0%]), and eyelashes (1/51 [2.0%]). Patchy alopecia suggestive of LPP was reported in 2 (3.9%) patients.

Patients frequently presented with scalp pruritus (26/51 [51.0%]), perifollicular papules or pustules (9/51 [17.6%]), and perifollicular hyperpigmentation (9/51 [17.6%]). Other associated symptoms included perifollicular erythema (6/51 [11.8%]), scalp pain (5/51 [9.8%]), hyperkeratosis or flaking (3/51 [5.9%]), and facial papules (2/51 [3.9%]). Loss of follicular ostia, prominent follicular ostia, and the lonely hair sign (Figure 2) was described in 21 (41.2%), 5 (9.8%), and 15 (29.4%) of patients, respectively. Hairstyles that involve scalp traction (19/51 [37.3%]) and/or chemicals (28/51 [54.9%]), such as hair dye or chemical relaxers, commonly were reported in patients prior to the onset of FFA.

The most commonly reported dermatologic comorbidities included traction alopecia (17/51 [33.3%]), followed by lichen planus pigmentosus (LLPigm)(7/51 [13.7%]), LPP (2/51 [3.9%]), psoriasis (1/51 [2.0%]), and morphea (1/51 [2.0%]). Reported comorbid diseases included Sjögren syndrome (2/51 [3.9%]), hypothyroidism (2/51 [3.9%]), HIV (1/51 [2.0%]), and diabetes mellitus (1/51 [2.0%]).

Of available reports (n=32), the most common histologic findings included perifollicular fibrosis (23/32 [71.9%]), lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation (22/23 [95.7%]) primarily affecting the isthmus and infundibular areas of the follicles, and decreased follicular density (21/23 [91.3%]).

The average time interval from treatment initiation to treatment assessment in available reports (n=25) was 1.8 years (range, 0.5–2 years). Response to treatment included regrowth of hair in 5.9% (3/51) of patients, FFA stabilization in 39.2% (20/51), FFA progression in 51.0% (26/51), and not reported in 3.9% (2/51). Combination therapy was used in 84.3% (43/51) of patients, while monotherapy was used in 11.8% (6/51), and 3.9% (2/51) did not have any treatment reported. Response to treatment was highly variable among patients, as were the combinations of therapeutic agents used (Table). Regrowth of hair was rare, occurring in only 2 (100%) patients treated with oral prednisone plus hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) or chloroquine (CHQ), and in 1 (50.0%) patient treated with topical corticosteroids plus antifungal shampoo, while there was no response in the other patient treated with this combination.

Improvement in hair loss, defined as having at least slowed progression of FFA, was observed in 100% (2/2) of patients who had oral steroids as part of their treatment regimen, followed by 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs)(finasteride and dutasteride; 62.5% [5/8]), intralesional steroids (57.1% [8/14]), HCQ/CHQ (42.9% [15/35]), topical steroids (41.5% [17/41]), antifungal shampoo (40.0% [2/5]), topical/oral minoxidil (36.0% [9/25]), and tacrolimus (33.3% [7/21]).

Comment

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a progressive scarring alopecia and a clinical variant of LPP. First described in 1994 by Kossard,1 it initially was thought to be a disease of postmenopausal White women. Although still most prevalent in White individuals, there has been a growing number of reports describing FFA in patients with SOC, including Black individuals.10 Despite the increasing number of cases over the years, studies on the treatment of FFA remain sparse. Without expert guidelines, treatments usually are chosen based on clinician preferences. Few observational studies on these treatment modalities and their clinical outcomes exist, and the cohorts largely are composed of White patients.10-12 However, Black individuals may respond differently to these treatments, just as they have been shown to exhibit unique features of FFA.3

Demographics of Patients With FFA—Consistent with our findings, prior studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be younger and premenopausal at FFA onset than their White counterparts.13-15 Among the Black individuals included in our review, the majority were premenopausal (53%) with an average age of FFA onset of 46.7 years. Conversely, only 5% of 60 White females with FFA reported in a retrospective review were premenopausal and had an older mean age of FFA onset of 64 years,1 substantiating prior reports.

Clinical Findings in Patients With FFA—The clinical findings observed in our cohort were consistent with what has previously been described in Black patients, including loss of follicular ostia (41.2%), lonely hair sign (29.4%), perifollicular erythema (11.8%), perifollicular papules (17.6%), and hyperkeratosis or flaking (5.9%). In comparing these findings with a review of 932 patients, 86% of whom were White, the observed frequencies of follicular ostia loss (38.3%) and lonely hair sign (26.7%) were similar; however, perifollicular erythema (44.2%), and hyperkeratosis (44.4%) were more prevalent in this group, while perifollicular papules (6.2%) were less common compared to our Black cohort.16 An explanation for this discrepancy in perifollicular erythema may be the increased skin pigmentation diminishing the appearance of erythema in Black individuals. Our cohort of Black individuals noted the presence of follicular hyperpigmentation (17.6%) and a high prevalence of scalp pruritus (51.0%), which appear to be more common in Black patients.3,17 Although it is unclear why these differences in FFA presentation exist, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware of these unique features when examining Black patients with suspected FFA.

Concomitant Cutaneous Disorders—A notable proportion of our cohort also had concomitant traction alopecia, which presents with frontotemporal alopecia, similar to FFA, making the diagnosis more challenging; however, the presence of perifollicular hyperpigmentation and facial hyperpigmentation in FFA may aid in differentiating these 2 entities.3 Other concomitant conditions noted in our review included androgenic alopecia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, hypothyroidism, morphea, and HIV, suggesting a potential interplay between autoimmune, genetic, hormonal, and environmental components in the etiology of FFA. In fact, a recent study found that a persistent inflammatory response, loss of immune privilege, and a genetic susceptibility are some of the key processes in the pathogenesis of FFA.18 Although the authors speculated that there may be other triggers in initiating the onset of FFA, such as steroid hormones, sun exposure, and topical allergens, more evidence and controlled studies are needed

Additionally, concomitant LPPigm occurred in 13.7% of our FFA cohort, which appears to be more common in patients with darker skin types.5,19-21 Lichen planus pigmentosus is a rare variant of LPP, and previous reports suggest that it may be associated with FFA.5 Similar to FFA, the pathogenesis of LPPigm also is unclear, and its treatment may be just as difficult.22 Because LPPigm may occur before, during, or after onset of FFA,23 it may be helpful for clinicians to search for the signs of LPPigm in patients with darker skin types patients presenting with hair loss both as a diagnostic clue and so that treatment may be tailored to both conditions.

Response to Treatment—Similar to the varying clinical pictures, the response to treatment also can vary between patients of different ethnicities. For Black patients, treatment outcomes did not seem as successful as they did for other patients with SOC described in the literature. A retrospective cohort of 58 Asian individuals with FFA found that up to 90% had improvement or stabilization of FFA after treatment,23 while only 45.1% (23/51) of the Black patients included in our study had improvement or stabilization. One reason may be that a greater proportion of Black patients are premenopausal at FFA onset (53%) compared to what is reported in Asian patients (28%),23 and women who are premenopausal at FFA onset often face more severe disease.15 Although there may be additional explanations for these differences in treatment outcomes between ethnic groups, further investigation is needed.

All patients included in our study received either monotherapy or combination therapy of topical/intralesional/oral steroids, HCQ or CHQ, 5-ARIs, topical/oral minoxidil, antifungal shampoo, and/or a calcineurin inhibitor; however, most patients (51.0%) did not see a response to treatment, while only 45.1% showed slowed or halted progression of FFA. Hair regrowth was rare, occurring in only 3 (5.9%) patients; 2 of them were the only patients treated with oral prednisone, making for a potentially promising therapeutic for Black patients that should be further investigated in larger controlled cohort studies. In a prior study, intramuscular steroids (40 mg every 3 weeks) plus topical minoxidil were unsuccessful in slowing the progression of FFA in 3 postmenopausal women,24 which may be explained by the racial differences in the response to FFA treatments and perhaps also menopausal status. Although not included in any of the regimens in our review, isotretinoin was shown to be effective in an ethnically unspecified group of patients (n=16) and also may be efficacious in Black individuals.25 Although FFA may stabilize with time,26 this was not observed in any of the patients included in our study; however, we only included patients who were treated, making it impossible to discern whether resolution was idiopathic or due to treatment.

Future Research—Research on treatments for FFA is lacking, especially in patients with SOC. Although we observed that there may be differences in the treatment response among Black individuals compared to other patients with SOC, additional studies are needed to delineate these racial differences, which can help guide management. More randomized controlled trials evaluating the various treatment regimens also are required to establish treatment guidelines. Frontal fibrosing alopecia likely is underdiagnosed in Black individuals, contributing to the lack of research in this group. Darker skin can obscure some of the clinical and dermoscopic features that are more visible in fair skin. Furthermore, it may be challenging to distinguish clinical features of FFA in the setting of concomitant traction alopecia, which is more common in Black patients.27 Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting in Black women also is less likely to be biopsied, contributing to the tendency to miss FFA in favor of traction or androgenic alopecia, which often are assumed to be more common in this population.2,27 Therefore, histologic evaluation through biopsy is paramount in securing an accurate diagnosis for Black patients with frontotemporal alopecia.

Study Limitations—The studies included in our review were limited by a lack of control comparison groups, especially among the retrospective cohort studies. Additionally, some of the studies included cases refractory to prior treatment modalities, possibly leading to a selection bias of more severe cases that were not representative of FFA in the general population. Thus, further studies involving larger populations of those with SOC are needed to fully evaluate the clinical utility of the current treatment modalities in this group.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

- Dlova NC, Jordaan HF, Skenjane A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 20 black patients from South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:939-941. doi:10.1111/bjd.12424

- Callender VD, Reid SD, Obayan O, et al. Diagnostic clues to frontal fibrosing alopecia in patients of African descent. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:45-51.

- Donati A, Molina L, Doche I, et al. Facial papules in frontal fibrosing alopecia: evidence of vellus follicle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1424-1427. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.321

- Uwakwe LN, Cardwell LA, Dothard EH, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and concomitant lichen planus pigmentosus: a case series of seven African American women. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:397-400.

- Naz E, Vidaurrázaga C, Hernández-Cano N, et al. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:25-27. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01131.x

- Dlova NC, Goh CL. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in an African man. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:81-83. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05821.x

- Huerth K, Kindred C. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presenting as androgenetic alopecia in an African American woman. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:794-795. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4682