User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The road to weight loss is paved with collusion and sabotage

Three big bumps on the weight-loss journey

The search for the Holy Grail. The destruction of the One Ring. The never-ending struggle to Lose Weight.

Like most legendary quests, weight loss is a journey, and we need support to help us achieve our goal. Maybe it’s gaining a new workout partner or finding a similarly-goaled Facebook Group. For a lot of people, it’s as simple as your friends and family. A recent study, however, suggests that the people closest to you may be your worst weight-loss enemies, and they might not even know it.

Researchers at the University of Surrey reviewed the literature on the positives and negatives of social support when it comes to weight loss and identified three types of negative effects: acts of sabotage, feeding behavior, and collusion.

Let’s start with the softest of intentions and work our way up. Collusion is the least negative. Friends and family may just go with the flow, even if it doesn’t agree with the goals of the person who’s trying to lose weight. It can even happen when health care professionals try to help their patients navigate or avoid obesity, ultimately killing with kindness, so to speak.

Next up, feeding behavior. Maybe you know someone whose love language is cooking. There are also people who share food because they don’t want to waste it or because they’re trying to be polite. They act out of the goodness of their hearts, but they’re putting up roadblocks to someone’s goals. These types of acts are usually one-sided, the researchers found. Remember, it’s okay to say, “No thanks.”

The last method, sabotage, is the most sinister. The saboteur may discourage others from eating healthy, undermine their efforts to be physically active, or take jabs at their confidence or self-esteem. Something as simple as criticizing someone for eating a salad or refusing to go on a walk with them can cause a setback.

“We need to explore this area further to develop interventions which could target family and friends and help them be more supportive in helping those they are close to lose weight,” said lead author Jane Odgen, PhD, of the University of Surrey, Guildford, England.

Like we said before, weight loss is a journey. The right support can only improve the odds of success.

Robots vs. mosquitoes

If there’s one thing robots are bad at, it’s giving solid mental health advice to people in crisis. If there’s one thing robots are very, very good at, it’s causing apocalypses. And joyous day for humanity, this time we’re not the ones being apocalypsed.

Yet.

Taiwan has a big mosquito problem. Not only do the mosquitoes in Taiwan carry dengue – among other dangerous diseases – but they’ve urbanized. Not urbanized in the sense that they’ve acquired a taste for organic coffee and avocado toast (that would be the millennial mosquito, a separate but even more terrifying creature), but more that they’ve adapted to reproduce literally anywhere and everywhere. Taiwanese mosquitoes like to breed in roadside sewer ditches, and this is where our genocidal robot comes in.

To combat the new, dangerous form of street-savvy mosquito, researchers built a robot armed with both insecticide and high-temperature, high-pressure water jets and sent it into the sewers of Kaohsiung City. The robot’s goal was simple: Whenever it came across signs of heavy mosquito breeding – eggs, larvae, pupae, and so on – the robot went to work. Utilizing both its primary weapons, the robot scrubbed numerous breeding sites across the city clean.

The researchers could just sit back and wait to see how effective their robot was. In the immediate aftermath, at various monitoring sites placed alongside the ditches, adult mosquito density fell by two-thirds in areas targeted by the robot. That’s nothing to sniff at, and it does make sense. After all, mosquitoes are quite difficult to kill in their adult stage, why not target them when they’re young and basically immobile?

The researchers saw promise with their mosquito-killing robot, but we’ve noticed a rather large issue. Killing two-thirds of mosquitoes is fine, but the third that’s left will be very angry. Very angry indeed. After all, we’re targeting the mosquito equivalent of children. Let’s hope our mosquito Terminator managed to kill mosquito Sarah Connor, or we’re going to have a big problem on our hands a bit later down the line.

This is knot what you were expecting

Physicians who aren’t surgeons probably don’t realize it, but the big thing that’s been getting between the knot-tying specialists and perfect suturing technique all these years is a lack of physics. Don’t believe us? Well, maybe you’ll believe plastic surgeon Samia Guerid, MD, of Lausanne, Switzerland: “The lack of physics-based analysis has been a limitation.” Nuff said.

That’s not enough for you, is it? Fine, we were warned.

Any surgical knot, Dr. Guerid and associates explained in a written statement, involves the “complex interplay” between six key factors: topology, geometry, elasticity, contact, friction, and polymer plasticity of the suturing filament. The strength of a suture “depends on the tension applied during the tying of the knot, [which] permanently deforms, or stretches the filament, creating a holding force.” Not enough tension and the knot comes undone, while too much snaps the filament.

For the experiment, Dr. Guerid tied a few dozen surgical knots, which were then scanned using x-ray micro–computed tomography to facilitate finite element modeling with a “3D continuum-level constitutive model for elastic-viscoplastic mechanical behavior” – no, we have no idea what that means, either – developed by the research team.

That model, and a great deal of math – so much math – allowed the researchers to define a threshold between loose and tight knots and uncover “relationships between knot strength and pretension, friction, and number of throws,” they said.

But what about the big question? The one about the ideal amount of tension? You may want to sit down. The answer to the ultimate question of the relationship between knot pretension and strength is … Did we mention that the team had its own mathematician? Their predictive model for safe knot-tying is … You’re not going to like this. The best way to teach safe knot-tying to both trainees and robots is … not ready yet.

The secret to targeting the knot tension sweet spot, for now, anyway, is still intuition gained from years of experience. Nobody ever said science was perfect … or easy … or quick.

Three big bumps on the weight-loss journey

The search for the Holy Grail. The destruction of the One Ring. The never-ending struggle to Lose Weight.

Like most legendary quests, weight loss is a journey, and we need support to help us achieve our goal. Maybe it’s gaining a new workout partner or finding a similarly-goaled Facebook Group. For a lot of people, it’s as simple as your friends and family. A recent study, however, suggests that the people closest to you may be your worst weight-loss enemies, and they might not even know it.

Researchers at the University of Surrey reviewed the literature on the positives and negatives of social support when it comes to weight loss and identified three types of negative effects: acts of sabotage, feeding behavior, and collusion.

Let’s start with the softest of intentions and work our way up. Collusion is the least negative. Friends and family may just go with the flow, even if it doesn’t agree with the goals of the person who’s trying to lose weight. It can even happen when health care professionals try to help their patients navigate or avoid obesity, ultimately killing with kindness, so to speak.

Next up, feeding behavior. Maybe you know someone whose love language is cooking. There are also people who share food because they don’t want to waste it or because they’re trying to be polite. They act out of the goodness of their hearts, but they’re putting up roadblocks to someone’s goals. These types of acts are usually one-sided, the researchers found. Remember, it’s okay to say, “No thanks.”

The last method, sabotage, is the most sinister. The saboteur may discourage others from eating healthy, undermine their efforts to be physically active, or take jabs at their confidence or self-esteem. Something as simple as criticizing someone for eating a salad or refusing to go on a walk with them can cause a setback.

“We need to explore this area further to develop interventions which could target family and friends and help them be more supportive in helping those they are close to lose weight,” said lead author Jane Odgen, PhD, of the University of Surrey, Guildford, England.

Like we said before, weight loss is a journey. The right support can only improve the odds of success.

Robots vs. mosquitoes

If there’s one thing robots are bad at, it’s giving solid mental health advice to people in crisis. If there’s one thing robots are very, very good at, it’s causing apocalypses. And joyous day for humanity, this time we’re not the ones being apocalypsed.

Yet.

Taiwan has a big mosquito problem. Not only do the mosquitoes in Taiwan carry dengue – among other dangerous diseases – but they’ve urbanized. Not urbanized in the sense that they’ve acquired a taste for organic coffee and avocado toast (that would be the millennial mosquito, a separate but even more terrifying creature), but more that they’ve adapted to reproduce literally anywhere and everywhere. Taiwanese mosquitoes like to breed in roadside sewer ditches, and this is where our genocidal robot comes in.

To combat the new, dangerous form of street-savvy mosquito, researchers built a robot armed with both insecticide and high-temperature, high-pressure water jets and sent it into the sewers of Kaohsiung City. The robot’s goal was simple: Whenever it came across signs of heavy mosquito breeding – eggs, larvae, pupae, and so on – the robot went to work. Utilizing both its primary weapons, the robot scrubbed numerous breeding sites across the city clean.

The researchers could just sit back and wait to see how effective their robot was. In the immediate aftermath, at various monitoring sites placed alongside the ditches, adult mosquito density fell by two-thirds in areas targeted by the robot. That’s nothing to sniff at, and it does make sense. After all, mosquitoes are quite difficult to kill in their adult stage, why not target them when they’re young and basically immobile?

The researchers saw promise with their mosquito-killing robot, but we’ve noticed a rather large issue. Killing two-thirds of mosquitoes is fine, but the third that’s left will be very angry. Very angry indeed. After all, we’re targeting the mosquito equivalent of children. Let’s hope our mosquito Terminator managed to kill mosquito Sarah Connor, or we’re going to have a big problem on our hands a bit later down the line.

This is knot what you were expecting

Physicians who aren’t surgeons probably don’t realize it, but the big thing that’s been getting between the knot-tying specialists and perfect suturing technique all these years is a lack of physics. Don’t believe us? Well, maybe you’ll believe plastic surgeon Samia Guerid, MD, of Lausanne, Switzerland: “The lack of physics-based analysis has been a limitation.” Nuff said.

That’s not enough for you, is it? Fine, we were warned.

Any surgical knot, Dr. Guerid and associates explained in a written statement, involves the “complex interplay” between six key factors: topology, geometry, elasticity, contact, friction, and polymer plasticity of the suturing filament. The strength of a suture “depends on the tension applied during the tying of the knot, [which] permanently deforms, or stretches the filament, creating a holding force.” Not enough tension and the knot comes undone, while too much snaps the filament.

For the experiment, Dr. Guerid tied a few dozen surgical knots, which were then scanned using x-ray micro–computed tomography to facilitate finite element modeling with a “3D continuum-level constitutive model for elastic-viscoplastic mechanical behavior” – no, we have no idea what that means, either – developed by the research team.

That model, and a great deal of math – so much math – allowed the researchers to define a threshold between loose and tight knots and uncover “relationships between knot strength and pretension, friction, and number of throws,” they said.

But what about the big question? The one about the ideal amount of tension? You may want to sit down. The answer to the ultimate question of the relationship between knot pretension and strength is … Did we mention that the team had its own mathematician? Their predictive model for safe knot-tying is … You’re not going to like this. The best way to teach safe knot-tying to both trainees and robots is … not ready yet.

The secret to targeting the knot tension sweet spot, for now, anyway, is still intuition gained from years of experience. Nobody ever said science was perfect … or easy … or quick.

Three big bumps on the weight-loss journey

The search for the Holy Grail. The destruction of the One Ring. The never-ending struggle to Lose Weight.

Like most legendary quests, weight loss is a journey, and we need support to help us achieve our goal. Maybe it’s gaining a new workout partner or finding a similarly-goaled Facebook Group. For a lot of people, it’s as simple as your friends and family. A recent study, however, suggests that the people closest to you may be your worst weight-loss enemies, and they might not even know it.

Researchers at the University of Surrey reviewed the literature on the positives and negatives of social support when it comes to weight loss and identified three types of negative effects: acts of sabotage, feeding behavior, and collusion.

Let’s start with the softest of intentions and work our way up. Collusion is the least negative. Friends and family may just go with the flow, even if it doesn’t agree with the goals of the person who’s trying to lose weight. It can even happen when health care professionals try to help their patients navigate or avoid obesity, ultimately killing with kindness, so to speak.

Next up, feeding behavior. Maybe you know someone whose love language is cooking. There are also people who share food because they don’t want to waste it or because they’re trying to be polite. They act out of the goodness of their hearts, but they’re putting up roadblocks to someone’s goals. These types of acts are usually one-sided, the researchers found. Remember, it’s okay to say, “No thanks.”

The last method, sabotage, is the most sinister. The saboteur may discourage others from eating healthy, undermine their efforts to be physically active, or take jabs at their confidence or self-esteem. Something as simple as criticizing someone for eating a salad or refusing to go on a walk with them can cause a setback.

“We need to explore this area further to develop interventions which could target family and friends and help them be more supportive in helping those they are close to lose weight,” said lead author Jane Odgen, PhD, of the University of Surrey, Guildford, England.

Like we said before, weight loss is a journey. The right support can only improve the odds of success.

Robots vs. mosquitoes

If there’s one thing robots are bad at, it’s giving solid mental health advice to people in crisis. If there’s one thing robots are very, very good at, it’s causing apocalypses. And joyous day for humanity, this time we’re not the ones being apocalypsed.

Yet.

Taiwan has a big mosquito problem. Not only do the mosquitoes in Taiwan carry dengue – among other dangerous diseases – but they’ve urbanized. Not urbanized in the sense that they’ve acquired a taste for organic coffee and avocado toast (that would be the millennial mosquito, a separate but even more terrifying creature), but more that they’ve adapted to reproduce literally anywhere and everywhere. Taiwanese mosquitoes like to breed in roadside sewer ditches, and this is where our genocidal robot comes in.

To combat the new, dangerous form of street-savvy mosquito, researchers built a robot armed with both insecticide and high-temperature, high-pressure water jets and sent it into the sewers of Kaohsiung City. The robot’s goal was simple: Whenever it came across signs of heavy mosquito breeding – eggs, larvae, pupae, and so on – the robot went to work. Utilizing both its primary weapons, the robot scrubbed numerous breeding sites across the city clean.

The researchers could just sit back and wait to see how effective their robot was. In the immediate aftermath, at various monitoring sites placed alongside the ditches, adult mosquito density fell by two-thirds in areas targeted by the robot. That’s nothing to sniff at, and it does make sense. After all, mosquitoes are quite difficult to kill in their adult stage, why not target them when they’re young and basically immobile?

The researchers saw promise with their mosquito-killing robot, but we’ve noticed a rather large issue. Killing two-thirds of mosquitoes is fine, but the third that’s left will be very angry. Very angry indeed. After all, we’re targeting the mosquito equivalent of children. Let’s hope our mosquito Terminator managed to kill mosquito Sarah Connor, or we’re going to have a big problem on our hands a bit later down the line.

This is knot what you were expecting

Physicians who aren’t surgeons probably don’t realize it, but the big thing that’s been getting between the knot-tying specialists and perfect suturing technique all these years is a lack of physics. Don’t believe us? Well, maybe you’ll believe plastic surgeon Samia Guerid, MD, of Lausanne, Switzerland: “The lack of physics-based analysis has been a limitation.” Nuff said.

That’s not enough for you, is it? Fine, we were warned.

Any surgical knot, Dr. Guerid and associates explained in a written statement, involves the “complex interplay” between six key factors: topology, geometry, elasticity, contact, friction, and polymer plasticity of the suturing filament. The strength of a suture “depends on the tension applied during the tying of the knot, [which] permanently deforms, or stretches the filament, creating a holding force.” Not enough tension and the knot comes undone, while too much snaps the filament.

For the experiment, Dr. Guerid tied a few dozen surgical knots, which were then scanned using x-ray micro–computed tomography to facilitate finite element modeling with a “3D continuum-level constitutive model for elastic-viscoplastic mechanical behavior” – no, we have no idea what that means, either – developed by the research team.

That model, and a great deal of math – so much math – allowed the researchers to define a threshold between loose and tight knots and uncover “relationships between knot strength and pretension, friction, and number of throws,” they said.

But what about the big question? The one about the ideal amount of tension? You may want to sit down. The answer to the ultimate question of the relationship between knot pretension and strength is … Did we mention that the team had its own mathematician? Their predictive model for safe knot-tying is … You’re not going to like this. The best way to teach safe knot-tying to both trainees and robots is … not ready yet.

The secret to targeting the knot tension sweet spot, for now, anyway, is still intuition gained from years of experience. Nobody ever said science was perfect … or easy … or quick.

Early hysterectomy linked to higher CVD, stroke risk

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Risk of CVD rapidly increases after menopause, possibly owing to loss of protective effects of female sex hormones and hemorheologic changes.

- Results of previous studies of the association between hysterectomy and CVD were mixed.

- Using national health insurance data, this cohort study included 55,539 South Korean women (median age, 45 years) who underwent a hysterectomy and a propensity-matched group of women.

- The primary outcome was CVD, including myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery revascularization, and stroke.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up of just under 8 years, the hysterectomy group had an increased risk of CVD compared with the non-hysterectomy group (hazard ratio [HR] 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09-1.44; P = .002)

- The incidence of MI and coronary revascularization was comparable between groups, but the risk of stroke was significantly higher among those who had had a hysterectomy (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P < .001)

- This increase in risk was similar after excluding patients who also underwent adnexal surgery.

IN PRACTICE:

Early hysterectomy was linked to higher CVD risk, especially stroke, but since the CVD incidence wasn’t high, a change in clinical practice may not be needed, said the authors.

STUDY DETAILS:

The study was conducted by Jin-Sung Yuk, MD, PhD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues. It was published online June 12 in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and observational and used administrative databases that may be prone to inaccurate coding. The findings may not be generalizable outside Korea.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Survival similar with hearts donated after circulatory or brain death

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

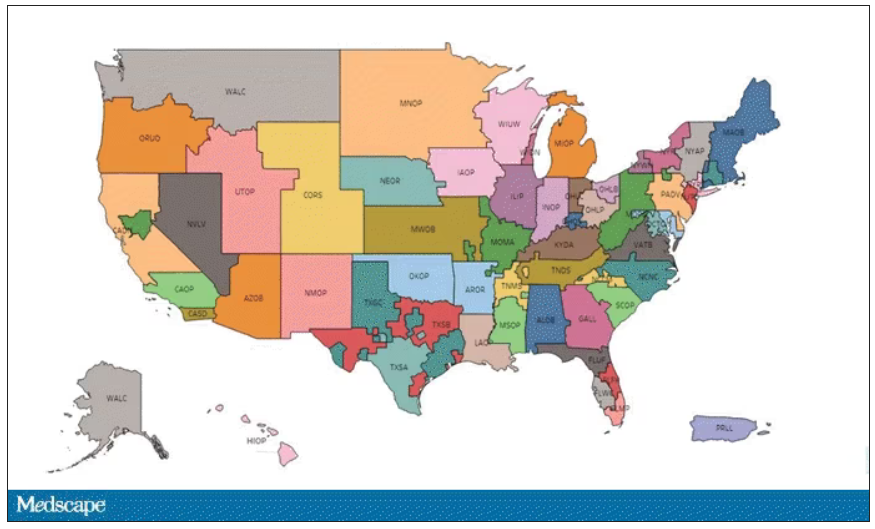

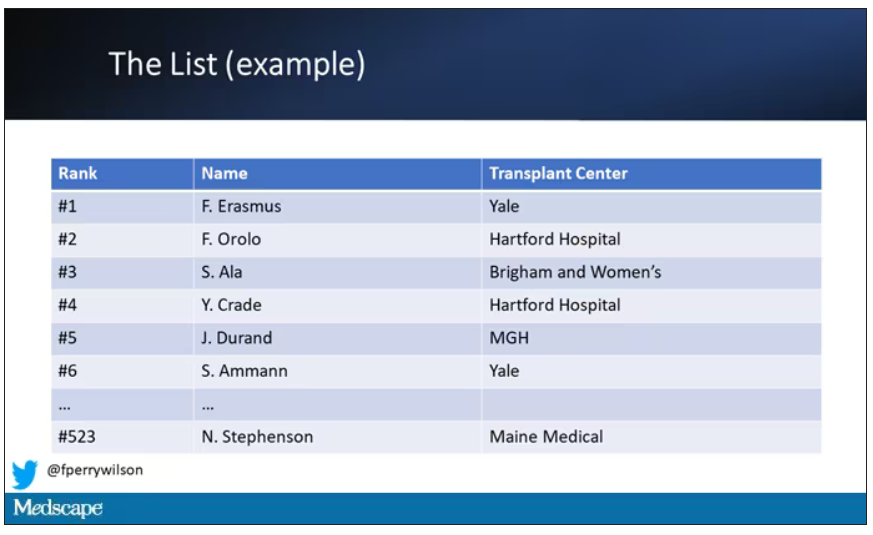

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

When could you be sued for AI malpractice? You’re likely using it now

The ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) may transform the future of medicine is making headlines across the globe. But chances are, you’re already using AI in your practice every day – you may just not realize it.

And whether you recognize the presence of AI or not, the technology could be putting you in danger of a lawsuit, legal experts say.

“For physicians, AI has also not yet drastically changed or improved the way care is provided or consumed,” said Michael LeTang, chief nursing informatics officer and vice president of risk management and patient safety at Healthcare Risk Advisors, part of TDC Group. “Consequently, it may seem like AI is not present in their work streams, but in reality, it has been utilized in health care for several years. As AI technologies continue to develop and become more sophisticated, we can expect them to play an increasingly significant role in health care.”

Today, most AI applications in health care use narrow AI, which is designed to complete a single task without human assistance, as opposed to artificial general intelligence (AGI), which pertains to human-level reasoning and problem solving across a broad spectrum. Here are some ways doctors are using AI throughout the day – sometimes being aware of its assistance, and sometimes being unaware:

- Many doctors use electronic health records (EHRs) with integrated AI that include computerized clinical decision support tools designed to reduce the risk of diagnostic error and to integrate decision-making in the medication ordering function.

- Cardiologists, pathologists, and dermatologists use AI in the interpretation of vast amounts of images, tracings, and complex patterns.

- Surgeons are using AI-enhanced surgical robotics for orthopedic surgeries, such as joint replacement and spine surgery.

- A growing number of doctors are using ChatGPT to assist in drafting prior authorization letters for insurers. Experts say more doctors are also experimenting with ChatGPT to support medical decision-making.

- Within oncology, physicians use machine learning techniques in the form of computer-aided detection systems for early breast cancer detection.

- AI algorithms are often used by health systems for workflow, staffing optimization, population management, and care coordination.

- Some systems within EHRs use AI to indicate high-risk patients.

- Physicians are using AI applications for the early recognition of sepsis, including EHR-integrated decision tools, such as the Hospital Corporation of America Healthcare’s Sepsis Prediction and Optimization Therapy and the Sepsis Early Risk Assessment algorithm.

- About 30% of radiologists use AI in their practice to analyze x-rays and CT scans.

- Epic Systems recently announced a partnership with Microsoft to integrate ChatGPT into MyChart, Epic’s patient portal system. Pilot hospitals will utilize ChatGPT to automatically generate responses to patient-generated questions sent via the portal.

The growth of AI in health care has been enormous, and it’s only going to continue, said Ravi B. Parikh, MD, an assistant professor in the department of medical ethics and health policy and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“What’s really critical is that physicians, clinicians, and nurses using AI are provided with the tools to understand how artificial intelligence works and, most importantly, understand that they are still accountable for making the ultimate decision,” Mr. LeTang said, “The information is not always going to be the right thing to do or the most accurate thing to do. They’re still liable for making a bad decision, even if AI is driving that.”

What are the top AI legal dangers of today?

A pressing legal risk is becoming too reliant on the suggestions that AI-based systems provide, which can lead to poor care decisions, said Kenneth Rashbaum, a New York–based cybersecurity attorney with more than 25 years of experience in medical malpractice defense.

This can occur, for example, when using clinical support systems that leverage AI, machine learning, or statistical pattern recognition. Today, clinical support systems are commonly administered through EHRs and other computerized clinical workflows. In general, such systems match a patient’s characteristics to a computerized clinical knowledge base. An assessment or recommendation is then presented to the physician for a decision.

“If the clinician blindly accepts it without considering whether it’s appropriate for this patient at this time with this presentation, the clinician may bear some responsibility if there is an untoward result,” Mr. Rashbaum said.

“A common claim even in the days before the EMR [electronic medical record] and AI, was that the clinician did not take all available information into account in rendering treatment, including history of past and present condition, as reflected in the records, communication with past and other present treating clinicians, lab and radiology results, discussions with the patient, and physical examination findings,” he said. “So, if the clinician relied upon the support prompt to the exclusion of these other sources of information, that could be a very strong argument for the plaintiff.”

Chatbots, such OpenAI’s ChatGPT, are another form of AI raising legal red flags. ChatGPT, trained on a massive set of text data, can carry out conversations, write code, draft emails, and answer any question posed. The chatbot has gained considerable credibility for accurately diagnosing rare conditions in seconds, and it recently passed the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination.

It’s unclear how many doctors are signing onto the ChatGPT website daily, but physicians are actively using the chatbot, particularly for assistance with prior authorization letters and to support decision-making processes in their practices, said Mr. LeTang.

When physicians ask ChatGPT a question, however, they should be mindful that ChatGPT could “hallucinate,” a term that refers to a generated response that sounds plausible but is factually incorrect or is unrelated to the context, explains Harvey Castro, MD, an emergency physician, ChatGPT health care expert, and author of the 2023 book “ChatGPT and Healthcare: Unlocking the Potential of Patient Empowerment.”

Acting on ChatGPT’s response without vetting the information places doctors at serious risk of a lawsuit, he said.

“Sometimes, the response is half true and half false,” he said. “Say, I go outside my specialty of emergency medicine and ask it about a pediatric surgical procedure. It could give me a response that sounds medically correct, but then I ask a pediatric cardiologist, and he says, ‘We don’t even do this. This doesn’t even exist!’ Physicians really have to make sure they are vetting the information provided.”

In response to ChatGPT’s growing usage by health care professionals, hospitals and practices are quickly implementing guidelines, policies, and restrictions that caution physicians about the accuracy of ChatGPT-generated information, adds Mr. LeTang.

Emerging best practices include avoiding the input of patient health information, personally identifiable information, or any data that could be commercially valuable or considered the intellectual property of a hospital or health system, he said.

“Another crucial guideline is not to rely solely on ChatGPT as a definitive source for clinical decision-making; physicians must exercise their professional judgment,” he said. “If best practices are not adhered to, the associated risks are present today. However, these risks may become more significant as AI technologies continue to evolve and become increasingly integrated into health care.”

The potential for misdiagnosis by AI systems and the risk of unnecessary procedures if physicians do not thoroughly evaluate and validate AI predictions are other dangers.

As an example, Mr. LeTang described a case in which a physician documents in the EHR that a patient has presented to the emergency department with chest pains and other signs of a heart attack, and an AI algorithm predicts that the patient is experiencing an active myocardial infarction. If the physician then sends the patient for stenting or an angioplasty without other concrete evidence or tests to confirm the diagnosis, the doctor could later face a misdiagnosis complaint if the costly procedures were unnecessary.

“That’s one of the risks of using artificial intelligence,” he said. “A large percentage of malpractice claims is failure to diagnose, delayed diagnosis, or inaccurate diagnosis. What falls in the category of failure to diagnose is sending a patient for an unnecessary procedure or having an adverse event or bad outcome because of the failure to diagnose.”

So far, no AI lawsuits have been filed, but they may make an appearance soon, said Sue Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company, a national medical liability insurer.

“There are hundreds of AI programs currently in use in health care,” she said. “At some point, a provider will make a decision that is contrary to what the AI recommended. The AI may be wrong, or the provider may be wrong. Either way, the provider will neglect to document their clinical reasoning, a patient will be harmed, and we will have the first AI claim.”

Upcoming AI legal risks to watch for

Lawsuits that allege biased patient care by physicians on the basis of algorithmic bias may also be forthcoming, analysts warn.

Much has been written about algorithmic bias that compounds and worsens inequities in socioeconomic status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender in health systems. In 2019, a groundbreaking article in Science shed light on commonly used algorithms that are considered racially biased and how health care professionals often use such information to make medical decisions.

No claims involving AI bias have come down the pipeline yet, but it’s an area to watch, said Ms. Boisvert. She noted a website that highlights complaints and accusations of AI bias, including in health care.

“We need to be sure the training of the AI is appropriate, current, and broad enough so that there is no bias in the AI when it’s participating in the decision-making,” said Ms. Boisvert. “Imagine if the AI is diagnosing based on a dataset that is not local. It doesn’t represent the population at that particular hospital, and it’s providing inaccurate information to the physicians who are then making decisions about treatment.”

In pain management, for example, there are known differences in how patients experience pain, Ms. Boisvert said. If AI was being used to develop an algorithm for how a particular patient’s postoperative pain should be managed, and the algorithm did not include the differences, the pain control for a certain patient could be inappropriate. A poor outcome resulting from the treatment could lead to a claim against the physician or hospital that used the biased AI system, she said.

In the future, as AI becomes more integrated and accepted in medicine, there may be a risk of legal complaints against doctors for not using AI, said Saurabh Jha, MD, an associate professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a scholar of AI in radiology.

“Ultimately, we might get to a place where AI starts helping physicians detect more or reduce the miss of certain conditions, and it becomes the standard of care,” Dr. Jha said. “For example, if it became part of the standard of care for pulmonary embolism [PE] detection, and you didn’t use it for PE detection, and there was a miss. That could put you at legal risk. We’re not at that stage yet, but that is one future possibility.”

Dr. Parikh envisions an even cloudier liability landscape as the potential grows for AI to control patient care decisions. In such a scenario, rather than just issuing an alert or prediction to a physician, the AI system could trigger an action.

For instance, if an algorithm is trained to predict sepsis and, once triggered, the AI could initiate a nurse-led rapid response or a change in patient care outside the clinician’s control, said Dr. Parikh, who coauthored a recent article on AI and medical liability in The Milbank Quarterly.

“That’s still very much the minority of how AI is being used, but as evidence is growing that AI-based diagnostic tools perform equivalent or even superior to physicians, these autonomous workflows are being considered,” Dr. Parikh said. “When the ultimate action upon the patient is more determined by the AI than what the clinician does, then I think the liability picture gets murkier, and we should be thinking about how we can respond to that from a liability framework.”

How you can prevent AI-related lawsuits

The first step to preventing an AI-related claim is being aware of when and how you are using AI.

Ensure you’re informed about how the AI was trained, Ms. Boisvert stresses.

“Ask questions!” she said. “Is the AI safe? Are the recommendations accurate? Does the AI perform better than current systems? In what way? What databases were used, and did the programmers consider bias? Do I understand how to use the results?”

Never blindly trust the AI but rather view it as a data point in a medical decision, said Dr. Parikh. Ensure that other sources of medical information are properly accessed and that best practices for your specialty are still being followed.

When using any form of AI, document your usage, adds Mr. Rashbaum. A record that clearly outlines how the physician incorporated the AI is critical if a claim later arises in which the doctor is accused of AI-related malpractice, he said.

“Indicating how the AI tool was used, why it was used, and that it was used in conjunction with available clinical information and the clinician’s best judgment could reduce the risk of being found responsible as a result of AI use in a particular case,” he said.

Use chatbots, such as ChatGPT, the way they were intended, as support tools, rather than definitive diagnostic instruments, adds Dr. Castro.

“Doctors should also be well-trained in interpreting and understanding the suggestions provided by ChatGPT and should use their clinical judgment and experience alongside the AI tool for more accurate decision-making,” he said.

In addition, because no AI insurance product exists on the market, physicians and organizations using AI – particularly for direct health care – should evaluate their current insurance or insurance-like products to determine where a claim involving AI might fall and whether the policy would respond, said Ms. Boisvert. The AI vendor/manufacturer will likely have indemnified themselves in the purchase and sale agreement or contract, she said.

It will also become increasingly important for medical practices, hospitals, and health systems to put in place strong data governance strategies, Mr. LeTang said.

“AI relies on good data,” he said. “A data governance strategy is a key component to making sure we understand where the data is coming from, what is represents, how accurate it is, if it’s reproducible, what controls are in place to ensure the right people have the right access, and that if we’re starting to use it to build algorithms, that it’s deidentified.”

While no malpractice claims associated with the use of AI have yet surfaced, this may change as legal courts catch up on the backlog of malpractice claims that were delayed because of COVID-19, and even more so as AI becomes more prevalent in health care, Mr. LeTang said.

“Similar to the attention that autonomous driving systems, like Tesla, receive when the system fails and accidents occur, we can be assured that media outlets will widely publicize AI-related medical adverse events,” he said. “It is crucial for health care professionals, AI developers, and regulatory authorities to work together to ensure the responsible use of AI in health care, with patient safety as the top priority. By doing so, they can mitigate the risks associated with AI implementation and minimize the potential for legal disputes arising from AI-related medical errors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The ways in which artificial intelligence (AI) may transform the future of medicine is making headlines across the globe. But chances are, you’re already using AI in your practice every day – you may just not realize it.

And whether you recognize the presence of AI or not, the technology could be putting you in danger of a lawsuit, legal experts say.

“For physicians, AI has also not yet drastically changed or improved the way care is provided or consumed,” said Michael LeTang, chief nursing informatics officer and vice president of risk management and patient safety at Healthcare Risk Advisors, part of TDC Group. “Consequently, it may seem like AI is not present in their work streams, but in reality, it has been utilized in health care for several years. As AI technologies continue to develop and become more sophisticated, we can expect them to play an increasingly significant role in health care.”

Today, most AI applications in health care use narrow AI, which is designed to complete a single task without human assistance, as opposed to artificial general intelligence (AGI), which pertains to human-level reasoning and problem solving across a broad spectrum. Here are some ways doctors are using AI throughout the day – sometimes being aware of its assistance, and sometimes being unaware:

- Many doctors use electronic health records (EHRs) with integrated AI that include computerized clinical decision support tools designed to reduce the risk of diagnostic error and to integrate decision-making in the medication ordering function.

- Cardiologists, pathologists, and dermatologists use AI in the interpretation of vast amounts of images, tracings, and complex patterns.

- Surgeons are using AI-enhanced surgical robotics for orthopedic surgeries, such as joint replacement and spine surgery.

- A growing number of doctors are using ChatGPT to assist in drafting prior authorization letters for insurers. Experts say more doctors are also experimenting with ChatGPT to support medical decision-making.

- Within oncology, physicians use machine learning techniques in the form of computer-aided detection systems for early breast cancer detection.

- AI algorithms are often used by health systems for workflow, staffing optimization, population management, and care coordination.

- Some systems within EHRs use AI to indicate high-risk patients.

- Physicians are using AI applications for the early recognition of sepsis, including EHR-integrated decision tools, such as the Hospital Corporation of America Healthcare’s Sepsis Prediction and Optimization Therapy and the Sepsis Early Risk Assessment algorithm.

- About 30% of radiologists use AI in their practice to analyze x-rays and CT scans.

- Epic Systems recently announced a partnership with Microsoft to integrate ChatGPT into MyChart, Epic’s patient portal system. Pilot hospitals will utilize ChatGPT to automatically generate responses to patient-generated questions sent via the portal.

The growth of AI in health care has been enormous, and it’s only going to continue, said Ravi B. Parikh, MD, an assistant professor in the department of medical ethics and health policy and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“What’s really critical is that physicians, clinicians, and nurses using AI are provided with the tools to understand how artificial intelligence works and, most importantly, understand that they are still accountable for making the ultimate decision,” Mr. LeTang said, “The information is not always going to be the right thing to do or the most accurate thing to do. They’re still liable for making a bad decision, even if AI is driving that.”

What are the top AI legal dangers of today?

A pressing legal risk is becoming too reliant on the suggestions that AI-based systems provide, which can lead to poor care decisions, said Kenneth Rashbaum, a New York–based cybersecurity attorney with more than 25 years of experience in medical malpractice defense.

This can occur, for example, when using clinical support systems that leverage AI, machine learning, or statistical pattern recognition. Today, clinical support systems are commonly administered through EHRs and other computerized clinical workflows. In general, such systems match a patient’s characteristics to a computerized clinical knowledge base. An assessment or recommendation is then presented to the physician for a decision.

“If the clinician blindly accepts it without considering whether it’s appropriate for this patient at this time with this presentation, the clinician may bear some responsibility if there is an untoward result,” Mr. Rashbaum said.

“A common claim even in the days before the EMR [electronic medical record] and AI, was that the clinician did not take all available information into account in rendering treatment, including history of past and present condition, as reflected in the records, communication with past and other present treating clinicians, lab and radiology results, discussions with the patient, and physical examination findings,” he said. “So, if the clinician relied upon the support prompt to the exclusion of these other sources of information, that could be a very strong argument for the plaintiff.”

Chatbots, such OpenAI’s ChatGPT, are another form of AI raising legal red flags. ChatGPT, trained on a massive set of text data, can carry out conversations, write code, draft emails, and answer any question posed. The chatbot has gained considerable credibility for accurately diagnosing rare conditions in seconds, and it recently passed the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination.

It’s unclear how many doctors are signing onto the ChatGPT website daily, but physicians are actively using the chatbot, particularly for assistance with prior authorization letters and to support decision-making processes in their practices, said Mr. LeTang.

When physicians ask ChatGPT a question, however, they should be mindful that ChatGPT could “hallucinate,” a term that refers to a generated response that sounds plausible but is factually incorrect or is unrelated to the context, explains Harvey Castro, MD, an emergency physician, ChatGPT health care expert, and author of the 2023 book “ChatGPT and Healthcare: Unlocking the Potential of Patient Empowerment.”

Acting on ChatGPT’s response without vetting the information places doctors at serious risk of a lawsuit, he said.

“Sometimes, the response is half true and half false,” he said. “Say, I go outside my specialty of emergency medicine and ask it about a pediatric surgical procedure. It could give me a response that sounds medically correct, but then I ask a pediatric cardiologist, and he says, ‘We don’t even do this. This doesn’t even exist!’ Physicians really have to make sure they are vetting the information provided.”

In response to ChatGPT’s growing usage by health care professionals, hospitals and practices are quickly implementing guidelines, policies, and restrictions that caution physicians about the accuracy of ChatGPT-generated information, adds Mr. LeTang.

Emerging best practices include avoiding the input of patient health information, personally identifiable information, or any data that could be commercially valuable or considered the intellectual property of a hospital or health system, he said.

“Another crucial guideline is not to rely solely on ChatGPT as a definitive source for clinical decision-making; physicians must exercise their professional judgment,” he said. “If best practices are not adhered to, the associated risks are present today. However, these risks may become more significant as AI technologies continue to evolve and become increasingly integrated into health care.”

The potential for misdiagnosis by AI systems and the risk of unnecessary procedures if physicians do not thoroughly evaluate and validate AI predictions are other dangers.

As an example, Mr. LeTang described a case in which a physician documents in the EHR that a patient has presented to the emergency department with chest pains and other signs of a heart attack, and an AI algorithm predicts that the patient is experiencing an active myocardial infarction. If the physician then sends the patient for stenting or an angioplasty without other concrete evidence or tests to confirm the diagnosis, the doctor could later face a misdiagnosis complaint if the costly procedures were unnecessary.

“That’s one of the risks of using artificial intelligence,” he said. “A large percentage of malpractice claims is failure to diagnose, delayed diagnosis, or inaccurate diagnosis. What falls in the category of failure to diagnose is sending a patient for an unnecessary procedure or having an adverse event or bad outcome because of the failure to diagnose.”

So far, no AI lawsuits have been filed, but they may make an appearance soon, said Sue Boisvert, senior patient safety risk manager at The Doctors Company, a national medical liability insurer.

“There are hundreds of AI programs currently in use in health care,” she said. “At some point, a provider will make a decision that is contrary to what the AI recommended. The AI may be wrong, or the provider may be wrong. Either way, the provider will neglect to document their clinical reasoning, a patient will be harmed, and we will have the first AI claim.”

Upcoming AI legal risks to watch for

Lawsuits that allege biased patient care by physicians on the basis of algorithmic bias may also be forthcoming, analysts warn.

Much has been written about algorithmic bias that compounds and worsens inequities in socioeconomic status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender in health systems. In 2019, a groundbreaking article in Science shed light on commonly used algorithms that are considered racially biased and how health care professionals often use such information to make medical decisions.

No claims involving AI bias have come down the pipeline yet, but it’s an area to watch, said Ms. Boisvert. She noted a website that highlights complaints and accusations of AI bias, including in health care.

“We need to be sure the training of the AI is appropriate, current, and broad enough so that there is no bias in the AI when it’s participating in the decision-making,” said Ms. Boisvert. “Imagine if the AI is diagnosing based on a dataset that is not local. It doesn’t represent the population at that particular hospital, and it’s providing inaccurate information to the physicians who are then making decisions about treatment.”

In pain management, for example, there are known differences in how patients experience pain, Ms. Boisvert said. If AI was being used to develop an algorithm for how a particular patient’s postoperative pain should be managed, and the algorithm did not include the differences, the pain control for a certain patient could be inappropriate. A poor outcome resulting from the treatment could lead to a claim against the physician or hospital that used the biased AI system, she said.