User login

Low-income DC communities have restricted access to iPLEDGE pharmacies

Residents of , results from a survey demonstrated.

Prescription of isotretinoin is regulated by the iPLEDGE program, which strives to ensure that no female patient starts isotretinoin therapy if pregnant and that no female patient on isotretinoin therapy becomes pregnant. “Over the years, many studies have criticized the program by demonstrating that iPLEDGE has promoted health care disparities,” Nidhi Shah said during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology. “For example, racial minorities and women are more likely to be underprescribed isotretinoin, as well as face more delays in treatment.”

In an effort to evaluate the geographic distribution of iPLEDGE pharmacies in Washington DC, and its correlation with sociodemographic factors, Ms. Shah, a third-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues obtained a list of active pharmacies in Washington from the local government. They also surveyed each outpatient pharmacy in the District of Columbia to verify their iPLEDGE registration status, for a total of 146 pharmacies.

Ms. Shah reported that 82% of all outpatient pharmacies were enrolled in iPLEDGE. However, enrollment significantly varied by the type of pharmacy. For example, 100% of chain pharmacies were enrolled, compared with 46% of independent pharmacies and 60% of hospital-based pharmacies.

When the researchers evaluated the number and type of iPLEDGE pharmacy by each of the eight wards in Washington, they observed a high density of pharmacies in wards 1 and 2, communities with a generally low proportion of residents who live in poverty, and low density of pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, communities with a higher proportion of residents who live in poverty. In addition, there were more independent than chain pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, and residents in those wards had a greater distance to travel to reach an iPLEDGE pharmacy, compared with residents who live in the other wards.

When Ms. Shah and colleagues examined the correlation between pharmacies per 10,000 residents and specific sociodemographic factors, they observed a strong, positive correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and median household income (P = .0003). On the other hand, there was a strong negative correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and the percentage of individuals with public insurance (P less than .0001), as well as the percentage of nonwhite individuals (P = .0009).

“Our study highlights the lack of isotretinoin-dispensing pharmacies in low-income communities,” Ms. Shah concluded. “Not only are there fewer such pharmacies available in low income communities, but the residents must also travel further to reach them. The spatial heterogeneity of iPLEDGE pharmacies may be an important patient barrier to timely access of isotretinoin, especially for female patients who have a strict 7-day window to collect their medication. We hope that future public health reform works to close this gap.”

The virtual meeting included presentations that had been slated for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ms. Shah reported having no disclosures.

Residents of , results from a survey demonstrated.

Prescription of isotretinoin is regulated by the iPLEDGE program, which strives to ensure that no female patient starts isotretinoin therapy if pregnant and that no female patient on isotretinoin therapy becomes pregnant. “Over the years, many studies have criticized the program by demonstrating that iPLEDGE has promoted health care disparities,” Nidhi Shah said during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology. “For example, racial minorities and women are more likely to be underprescribed isotretinoin, as well as face more delays in treatment.”

In an effort to evaluate the geographic distribution of iPLEDGE pharmacies in Washington DC, and its correlation with sociodemographic factors, Ms. Shah, a third-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues obtained a list of active pharmacies in Washington from the local government. They also surveyed each outpatient pharmacy in the District of Columbia to verify their iPLEDGE registration status, for a total of 146 pharmacies.

Ms. Shah reported that 82% of all outpatient pharmacies were enrolled in iPLEDGE. However, enrollment significantly varied by the type of pharmacy. For example, 100% of chain pharmacies were enrolled, compared with 46% of independent pharmacies and 60% of hospital-based pharmacies.

When the researchers evaluated the number and type of iPLEDGE pharmacy by each of the eight wards in Washington, they observed a high density of pharmacies in wards 1 and 2, communities with a generally low proportion of residents who live in poverty, and low density of pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, communities with a higher proportion of residents who live in poverty. In addition, there were more independent than chain pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, and residents in those wards had a greater distance to travel to reach an iPLEDGE pharmacy, compared with residents who live in the other wards.

When Ms. Shah and colleagues examined the correlation between pharmacies per 10,000 residents and specific sociodemographic factors, they observed a strong, positive correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and median household income (P = .0003). On the other hand, there was a strong negative correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and the percentage of individuals with public insurance (P less than .0001), as well as the percentage of nonwhite individuals (P = .0009).

“Our study highlights the lack of isotretinoin-dispensing pharmacies in low-income communities,” Ms. Shah concluded. “Not only are there fewer such pharmacies available in low income communities, but the residents must also travel further to reach them. The spatial heterogeneity of iPLEDGE pharmacies may be an important patient barrier to timely access of isotretinoin, especially for female patients who have a strict 7-day window to collect their medication. We hope that future public health reform works to close this gap.”

The virtual meeting included presentations that had been slated for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ms. Shah reported having no disclosures.

Residents of , results from a survey demonstrated.

Prescription of isotretinoin is regulated by the iPLEDGE program, which strives to ensure that no female patient starts isotretinoin therapy if pregnant and that no female patient on isotretinoin therapy becomes pregnant. “Over the years, many studies have criticized the program by demonstrating that iPLEDGE has promoted health care disparities,” Nidhi Shah said during a virtual meeting held by the George Washington University department of dermatology. “For example, racial minorities and women are more likely to be underprescribed isotretinoin, as well as face more delays in treatment.”

In an effort to evaluate the geographic distribution of iPLEDGE pharmacies in Washington DC, and its correlation with sociodemographic factors, Ms. Shah, a third-year medical student at the George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues obtained a list of active pharmacies in Washington from the local government. They also surveyed each outpatient pharmacy in the District of Columbia to verify their iPLEDGE registration status, for a total of 146 pharmacies.

Ms. Shah reported that 82% of all outpatient pharmacies were enrolled in iPLEDGE. However, enrollment significantly varied by the type of pharmacy. For example, 100% of chain pharmacies were enrolled, compared with 46% of independent pharmacies and 60% of hospital-based pharmacies.

When the researchers evaluated the number and type of iPLEDGE pharmacy by each of the eight wards in Washington, they observed a high density of pharmacies in wards 1 and 2, communities with a generally low proportion of residents who live in poverty, and low density of pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, communities with a higher proportion of residents who live in poverty. In addition, there were more independent than chain pharmacies in wards 7 and 8, and residents in those wards had a greater distance to travel to reach an iPLEDGE pharmacy, compared with residents who live in the other wards.

When Ms. Shah and colleagues examined the correlation between pharmacies per 10,000 residents and specific sociodemographic factors, they observed a strong, positive correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and median household income (P = .0003). On the other hand, there was a strong negative correlation between iPLEDGE pharmacy density and the percentage of individuals with public insurance (P less than .0001), as well as the percentage of nonwhite individuals (P = .0009).

“Our study highlights the lack of isotretinoin-dispensing pharmacies in low-income communities,” Ms. Shah concluded. “Not only are there fewer such pharmacies available in low income communities, but the residents must also travel further to reach them. The spatial heterogeneity of iPLEDGE pharmacies may be an important patient barrier to timely access of isotretinoin, especially for female patients who have a strict 7-day window to collect their medication. We hope that future public health reform works to close this gap.”

The virtual meeting included presentations that had been slated for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ms. Shah reported having no disclosures.

Isotretinoin data provide postmeal absorption guidance

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Recent , Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

It is recommended that isotretinoin, which is fat-soluble, be taken with food, preferably high-fat foods. So it has been unclear what the effect would be when taken with lower-fat food, such as low-fat cereal and raspberries, for example, Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York, pointed out.

“We’ve been trying for years to figure out how we’re going to get around this,” and there have not been any relevant data available until recently, other than in the setting of taking isotretinoin on an empty stomach or with a high-fat meal, she commented.

She referred to a open-label, single-dose, randomized crossover study that compared the bioavailability of the lidose formulation of isotretinoin (Absorica) and brand name Accutane, at a dose of 40 mg either on top of a fatty meal (the Food and Drug Administration-stipulated high-fat, high-calorie diet) or after a 10-hour fast; 60 patients did all four arms, with a 21-day washout period between them (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69[5]:762-7).

In the fed state, both isotretinoin formulations were absorbed to the same extent, “but in the fasting state, there was a considerable difference,” Dr. Baldwin said. Absorption of both dropped in the fasting state, but the drop was more extreme with Accutane, “about a 50% difference between the two, in terms of how much drug was getting into the system,” she noted.

That is important because weight-based dosing is considered with isotretinoin, so at the end of treatment, a patient who has been taking it on an empty stomach may be getting a 60% lower dose than prescribed, “which could lead to a lessening of the effectiveness of the drug and also an increase in relapse over time.”

But how would a low-fat meal, like low-fat cereal and raspberries, affect the absorption, and ultimate efficacy?

This question was addressed in an open-label, single-arm study of 163 patients with acne, who were taking the lidose isotretinoin formulation without food, at the standard dose, for no longer than 20 weeks. Whether they relapsed was evaluated in a 2-year observational phase of the study, Dr. Baldwin said.

At the end of the trial, the drug was considered effective, with improvements in IGA (the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale). But the change from baseline was maintained at the 2-year posttreatment period, so the benefits of treatment lasted, which indicates that patients can take it “on top of absolutely no food whatsoever ... so if they eat anything, we are headed in the right direction,” including a low-fat meal. During the 2-year period, most patients did not need to be retreated. Of those people who needed treatment, only 4.2% needed treatment with isotretinoin, which is better than the historical relapse rates with isotretinoin, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin’s disclosures included being on the speakers’ bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Recent , Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

It is recommended that isotretinoin, which is fat-soluble, be taken with food, preferably high-fat foods. So it has been unclear what the effect would be when taken with lower-fat food, such as low-fat cereal and raspberries, for example, Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York, pointed out.

“We’ve been trying for years to figure out how we’re going to get around this,” and there have not been any relevant data available until recently, other than in the setting of taking isotretinoin on an empty stomach or with a high-fat meal, she commented.

She referred to a open-label, single-dose, randomized crossover study that compared the bioavailability of the lidose formulation of isotretinoin (Absorica) and brand name Accutane, at a dose of 40 mg either on top of a fatty meal (the Food and Drug Administration-stipulated high-fat, high-calorie diet) or after a 10-hour fast; 60 patients did all four arms, with a 21-day washout period between them (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69[5]:762-7).

In the fed state, both isotretinoin formulations were absorbed to the same extent, “but in the fasting state, there was a considerable difference,” Dr. Baldwin said. Absorption of both dropped in the fasting state, but the drop was more extreme with Accutane, “about a 50% difference between the two, in terms of how much drug was getting into the system,” she noted.

That is important because weight-based dosing is considered with isotretinoin, so at the end of treatment, a patient who has been taking it on an empty stomach may be getting a 60% lower dose than prescribed, “which could lead to a lessening of the effectiveness of the drug and also an increase in relapse over time.”

But how would a low-fat meal, like low-fat cereal and raspberries, affect the absorption, and ultimate efficacy?

This question was addressed in an open-label, single-arm study of 163 patients with acne, who were taking the lidose isotretinoin formulation without food, at the standard dose, for no longer than 20 weeks. Whether they relapsed was evaluated in a 2-year observational phase of the study, Dr. Baldwin said.

At the end of the trial, the drug was considered effective, with improvements in IGA (the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale). But the change from baseline was maintained at the 2-year posttreatment period, so the benefits of treatment lasted, which indicates that patients can take it “on top of absolutely no food whatsoever ... so if they eat anything, we are headed in the right direction,” including a low-fat meal. During the 2-year period, most patients did not need to be retreated. Of those people who needed treatment, only 4.2% needed treatment with isotretinoin, which is better than the historical relapse rates with isotretinoin, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin’s disclosures included being on the speakers’ bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Recent , Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

It is recommended that isotretinoin, which is fat-soluble, be taken with food, preferably high-fat foods. So it has been unclear what the effect would be when taken with lower-fat food, such as low-fat cereal and raspberries, for example, Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York, pointed out.

“We’ve been trying for years to figure out how we’re going to get around this,” and there have not been any relevant data available until recently, other than in the setting of taking isotretinoin on an empty stomach or with a high-fat meal, she commented.

She referred to a open-label, single-dose, randomized crossover study that compared the bioavailability of the lidose formulation of isotretinoin (Absorica) and brand name Accutane, at a dose of 40 mg either on top of a fatty meal (the Food and Drug Administration-stipulated high-fat, high-calorie diet) or after a 10-hour fast; 60 patients did all four arms, with a 21-day washout period between them (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69[5]:762-7).

In the fed state, both isotretinoin formulations were absorbed to the same extent, “but in the fasting state, there was a considerable difference,” Dr. Baldwin said. Absorption of both dropped in the fasting state, but the drop was more extreme with Accutane, “about a 50% difference between the two, in terms of how much drug was getting into the system,” she noted.

That is important because weight-based dosing is considered with isotretinoin, so at the end of treatment, a patient who has been taking it on an empty stomach may be getting a 60% lower dose than prescribed, “which could lead to a lessening of the effectiveness of the drug and also an increase in relapse over time.”

But how would a low-fat meal, like low-fat cereal and raspberries, affect the absorption, and ultimate efficacy?

This question was addressed in an open-label, single-arm study of 163 patients with acne, who were taking the lidose isotretinoin formulation without food, at the standard dose, for no longer than 20 weeks. Whether they relapsed was evaluated in a 2-year observational phase of the study, Dr. Baldwin said.

At the end of the trial, the drug was considered effective, with improvements in IGA (the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale). But the change from baseline was maintained at the 2-year posttreatment period, so the benefits of treatment lasted, which indicates that patients can take it “on top of absolutely no food whatsoever ... so if they eat anything, we are headed in the right direction,” including a low-fat meal. During the 2-year period, most patients did not need to be retreated. Of those people who needed treatment, only 4.2% needed treatment with isotretinoin, which is better than the historical relapse rates with isotretinoin, she noted.

Dr. Baldwin’s disclosures included being on the speakers’ bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Avoid ‘mutant selection window’ when prescribing antibiotics for acne

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Consider the “mutant selection window” to reduce antibiotic resistance when treating acne, Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, advised at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dermatologists continue to write a disproportionate number of prescriptions for antibiotics, particularly tetracyclines, noted Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York. In addition to limiting unnecessary use of antimicrobials, strategies for slowing antimicrobial resistance include using anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline; using more retinoids, isotretinoin, spironolactone, and oral contraceptives; and improving patient compliance with treatment.

Dermatologists can also “pay attention to the bug we are treating and ... make sure the concentration of the drug that we are using is appropriate to the bug we’re trying to kill,” while also targeting resistant organisms. Dr. Baldwin referred to a paper in the infectious disease literature titled: “The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance,” which points out that a drug concentration range exists for which mutant strains of bacteria are selected most frequently (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Jul;52[1]:11-7). The dimensions of this range, or “window,” are characteristic of each pathogen-antimicrobial combination. A high enough drug concentration will eliminate both resistant and sensitive strains of the pathogen.

The paper notes that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism. The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) is the minimum drug concentration needed to prevent the growth of resistant strains, Dr. Baldwin said. The mutant selection window is the concentration range that extends from the MIC up to the MPC, the range “within which resistant mutants are likely to emerge.” If the antimicrobial concentration falls within this window, a mutant strain is likely to develop and “you’re going to add to the problem of antibiotic resistance,” she explained. “So the goal is to treat low or to treat high, but not right in the middle.”

“This is not theoretical,” and has been shown over and over again, with, for example, Streptococcus pneumonia and moxifloxacin, she said (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Oct;52[4]:616-22.).

When the therapeutic window does not extend all the way to the MPC, “toxicity starts to kick in before you can get high enough to kill off the whole group of organisms,” in which case a low-dose strategy would reduce the development of resistant organisms, she noted.

“We’re doing this already,” with topical antifungals, Dr. Baldwin pointed out, asking when the last time anyone heard that a fungus developed resistance to topical antifungal therapy. “Never, because we use our antifungals in such a high dose, that we’re 500 times the MPC.”

Using an anti-inflammatory dose of doxycycline for treating acne or rosacea is a low-dose strategy, and the 40-mg delayed-release dose stays “way below” the antimicrobial threshold, she said, but the 50-mg dose falls “right in the middle of that mutant selection window.”

As more treatments become available, it will be important to determine how to dose topical antibiotics so that they do not fall within the mutant selection window and avoid what happened with clindamycin and erythromycin, “where the topical use of these medications led to the development of resistance such that they no longer work for the treatment” of Cutibacterium acnes.

Dr. Baldwin disclosures included being on the speakers bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Consider the “mutant selection window” to reduce antibiotic resistance when treating acne, Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, advised at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dermatologists continue to write a disproportionate number of prescriptions for antibiotics, particularly tetracyclines, noted Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York. In addition to limiting unnecessary use of antimicrobials, strategies for slowing antimicrobial resistance include using anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline; using more retinoids, isotretinoin, spironolactone, and oral contraceptives; and improving patient compliance with treatment.

Dermatologists can also “pay attention to the bug we are treating and ... make sure the concentration of the drug that we are using is appropriate to the bug we’re trying to kill,” while also targeting resistant organisms. Dr. Baldwin referred to a paper in the infectious disease literature titled: “The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance,” which points out that a drug concentration range exists for which mutant strains of bacteria are selected most frequently (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Jul;52[1]:11-7). The dimensions of this range, or “window,” are characteristic of each pathogen-antimicrobial combination. A high enough drug concentration will eliminate both resistant and sensitive strains of the pathogen.

The paper notes that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism. The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) is the minimum drug concentration needed to prevent the growth of resistant strains, Dr. Baldwin said. The mutant selection window is the concentration range that extends from the MIC up to the MPC, the range “within which resistant mutants are likely to emerge.” If the antimicrobial concentration falls within this window, a mutant strain is likely to develop and “you’re going to add to the problem of antibiotic resistance,” she explained. “So the goal is to treat low or to treat high, but not right in the middle.”

“This is not theoretical,” and has been shown over and over again, with, for example, Streptococcus pneumonia and moxifloxacin, she said (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Oct;52[4]:616-22.).

When the therapeutic window does not extend all the way to the MPC, “toxicity starts to kick in before you can get high enough to kill off the whole group of organisms,” in which case a low-dose strategy would reduce the development of resistant organisms, she noted.

“We’re doing this already,” with topical antifungals, Dr. Baldwin pointed out, asking when the last time anyone heard that a fungus developed resistance to topical antifungal therapy. “Never, because we use our antifungals in such a high dose, that we’re 500 times the MPC.”

Using an anti-inflammatory dose of doxycycline for treating acne or rosacea is a low-dose strategy, and the 40-mg delayed-release dose stays “way below” the antimicrobial threshold, she said, but the 50-mg dose falls “right in the middle of that mutant selection window.”

As more treatments become available, it will be important to determine how to dose topical antibiotics so that they do not fall within the mutant selection window and avoid what happened with clindamycin and erythromycin, “where the topical use of these medications led to the development of resistance such that they no longer work for the treatment” of Cutibacterium acnes.

Dr. Baldwin disclosures included being on the speakers bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Consider the “mutant selection window” to reduce antibiotic resistance when treating acne, Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, advised at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dermatologists continue to write a disproportionate number of prescriptions for antibiotics, particularly tetracyclines, noted Dr. Baldwin, medical director of the Acne Treatment and Research Center in New York. In addition to limiting unnecessary use of antimicrobials, strategies for slowing antimicrobial resistance include using anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline; using more retinoids, isotretinoin, spironolactone, and oral contraceptives; and improving patient compliance with treatment.

Dermatologists can also “pay attention to the bug we are treating and ... make sure the concentration of the drug that we are using is appropriate to the bug we’re trying to kill,” while also targeting resistant organisms. Dr. Baldwin referred to a paper in the infectious disease literature titled: “The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance,” which points out that a drug concentration range exists for which mutant strains of bacteria are selected most frequently (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Jul;52[1]:11-7). The dimensions of this range, or “window,” are characteristic of each pathogen-antimicrobial combination. A high enough drug concentration will eliminate both resistant and sensitive strains of the pathogen.

The paper notes that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism. The mutant prevention concentration (MPC) is the minimum drug concentration needed to prevent the growth of resistant strains, Dr. Baldwin said. The mutant selection window is the concentration range that extends from the MIC up to the MPC, the range “within which resistant mutants are likely to emerge.” If the antimicrobial concentration falls within this window, a mutant strain is likely to develop and “you’re going to add to the problem of antibiotic resistance,” she explained. “So the goal is to treat low or to treat high, but not right in the middle.”

“This is not theoretical,” and has been shown over and over again, with, for example, Streptococcus pneumonia and moxifloxacin, she said (J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Oct;52[4]:616-22.).

When the therapeutic window does not extend all the way to the MPC, “toxicity starts to kick in before you can get high enough to kill off the whole group of organisms,” in which case a low-dose strategy would reduce the development of resistant organisms, she noted.

“We’re doing this already,” with topical antifungals, Dr. Baldwin pointed out, asking when the last time anyone heard that a fungus developed resistance to topical antifungal therapy. “Never, because we use our antifungals in such a high dose, that we’re 500 times the MPC.”

Using an anti-inflammatory dose of doxycycline for treating acne or rosacea is a low-dose strategy, and the 40-mg delayed-release dose stays “way below” the antimicrobial threshold, she said, but the 50-mg dose falls “right in the middle of that mutant selection window.”

As more treatments become available, it will be important to determine how to dose topical antibiotics so that they do not fall within the mutant selection window and avoid what happened with clindamycin and erythromycin, “where the topical use of these medications led to the development of resistance such that they no longer work for the treatment” of Cutibacterium acnes.

Dr. Baldwin disclosures included being on the speakers bureau, serving as an advisor, and/or an investigator for companies that include Almirall, BioPharmx, Foamix, Galderma, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and La Roche–Posay.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Acne treatment may vary based on race, gender, insurance

based on findings from a retrospective, cohort study of 29,928 individuals with acne.

“Our findings suggest the presence of racial/ethnic, sex, and insurance-based disparities in health care use and treatment for acne and raise particular concern for undertreatment among racial/ethnic minority and female patients,” John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote in a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies have suggested racial disparities in the management of several dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but associations between social demographics and prescribing patterns have not been well studied for acne treatment, the authors noted.

For the current study, the researchers used deidentified data from the Optum electronic health record from Jan. 1, 2007 to June 30, 2017. In all, 29,928 patients aged 15-35 years and who were being treated for acne were included in the study. Of that total, 64% were women, 8% were non-Hispanic black and 68% were white, with the remaining patients grouped as non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, or other.

Non-Hispanic black patients were significantly more likely to be seen by a dermatologist, compared with non-Hispanic white patients, who were designated as the reference (odds ratio, 1.20). However, the black patients were less likely to receive prescriptions for any acne medication (incidence rate ratio, 0.89).

Non-Hispanic black patients were more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to be prescribed topical retinoids or topical antibiotics (OR, 1.25 and 1.35, respectively). They were also were less likely than their white counterparts to be prescribed oral antibiotics, spironolactone, and isotretinoin (OR, 0.80, 0.68, and 0.39, respectively).

Overall, men were more than twice as likely as women to receive prescriptions for isotretinoin (OR, 2.44). They were also more likely to receive prescriptions for the other treatments, but the differences were not as high as those for isotretinoin.

In addition, patients with Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely than those with commercial insurance (the reference) to see a dermatologist (OR, 0.46). Medicaid patients also were less likely to be prescribed topical retinoids, oral antibiotics, spironolactone, or isotretinoin (OR, 0.82, 0.87, 0.50, and 0.43, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors, among them, the use of automated pharmacy data without confirmation that patients had picked up the medications they had been prescribed, the researchers said. The study also lacked data on acne severity, clinical outcomes, and the use of over-the-counter acne treatments.

“Further study is needed to confirm our findings, provide understanding of the reasons for these potential disparities, and develop strategies to ensure equitable care for patients with acne,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, and by a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Barbieri had no financial conflicts to disclose. One of the study coauthors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Barbieri JS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818.

based on findings from a retrospective, cohort study of 29,928 individuals with acne.

“Our findings suggest the presence of racial/ethnic, sex, and insurance-based disparities in health care use and treatment for acne and raise particular concern for undertreatment among racial/ethnic minority and female patients,” John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote in a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies have suggested racial disparities in the management of several dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but associations between social demographics and prescribing patterns have not been well studied for acne treatment, the authors noted.

For the current study, the researchers used deidentified data from the Optum electronic health record from Jan. 1, 2007 to June 30, 2017. In all, 29,928 patients aged 15-35 years and who were being treated for acne were included in the study. Of that total, 64% were women, 8% were non-Hispanic black and 68% were white, with the remaining patients grouped as non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, or other.

Non-Hispanic black patients were significantly more likely to be seen by a dermatologist, compared with non-Hispanic white patients, who were designated as the reference (odds ratio, 1.20). However, the black patients were less likely to receive prescriptions for any acne medication (incidence rate ratio, 0.89).

Non-Hispanic black patients were more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to be prescribed topical retinoids or topical antibiotics (OR, 1.25 and 1.35, respectively). They were also were less likely than their white counterparts to be prescribed oral antibiotics, spironolactone, and isotretinoin (OR, 0.80, 0.68, and 0.39, respectively).

Overall, men were more than twice as likely as women to receive prescriptions for isotretinoin (OR, 2.44). They were also more likely to receive prescriptions for the other treatments, but the differences were not as high as those for isotretinoin.

In addition, patients with Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely than those with commercial insurance (the reference) to see a dermatologist (OR, 0.46). Medicaid patients also were less likely to be prescribed topical retinoids, oral antibiotics, spironolactone, or isotretinoin (OR, 0.82, 0.87, 0.50, and 0.43, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors, among them, the use of automated pharmacy data without confirmation that patients had picked up the medications they had been prescribed, the researchers said. The study also lacked data on acne severity, clinical outcomes, and the use of over-the-counter acne treatments.

“Further study is needed to confirm our findings, provide understanding of the reasons for these potential disparities, and develop strategies to ensure equitable care for patients with acne,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, and by a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Barbieri had no financial conflicts to disclose. One of the study coauthors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Barbieri JS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818.

based on findings from a retrospective, cohort study of 29,928 individuals with acne.

“Our findings suggest the presence of racial/ethnic, sex, and insurance-based disparities in health care use and treatment for acne and raise particular concern for undertreatment among racial/ethnic minority and female patients,” John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatology research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote in a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies have suggested racial disparities in the management of several dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but associations between social demographics and prescribing patterns have not been well studied for acne treatment, the authors noted.

For the current study, the researchers used deidentified data from the Optum electronic health record from Jan. 1, 2007 to June 30, 2017. In all, 29,928 patients aged 15-35 years and who were being treated for acne were included in the study. Of that total, 64% were women, 8% were non-Hispanic black and 68% were white, with the remaining patients grouped as non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, or other.

Non-Hispanic black patients were significantly more likely to be seen by a dermatologist, compared with non-Hispanic white patients, who were designated as the reference (odds ratio, 1.20). However, the black patients were less likely to receive prescriptions for any acne medication (incidence rate ratio, 0.89).

Non-Hispanic black patients were more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to be prescribed topical retinoids or topical antibiotics (OR, 1.25 and 1.35, respectively). They were also were less likely than their white counterparts to be prescribed oral antibiotics, spironolactone, and isotretinoin (OR, 0.80, 0.68, and 0.39, respectively).

Overall, men were more than twice as likely as women to receive prescriptions for isotretinoin (OR, 2.44). They were also more likely to receive prescriptions for the other treatments, but the differences were not as high as those for isotretinoin.

In addition, patients with Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely than those with commercial insurance (the reference) to see a dermatologist (OR, 0.46). Medicaid patients also were less likely to be prescribed topical retinoids, oral antibiotics, spironolactone, or isotretinoin (OR, 0.82, 0.87, 0.50, and 0.43, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors, among them, the use of automated pharmacy data without confirmation that patients had picked up the medications they had been prescribed, the researchers said. The study also lacked data on acne severity, clinical outcomes, and the use of over-the-counter acne treatments.

“Further study is needed to confirm our findings, provide understanding of the reasons for these potential disparities, and develop strategies to ensure equitable care for patients with acne,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, and by a Pfizer Fellowship in Dermatology Patient Oriented Research grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Barbieri had no financial conflicts to disclose. One of the study coauthors disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Barbieri JS et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4818.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Effect of In-Office Samples on Dermatologists’ Prescribing Habits: A Retrospective Review

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3

A 2014 study reported that prescribing habits are influenced by the free drug samples provided by nongeneric pharmaceutical companies.19 Nationally, the number of brand-name and branded generic medications constitute 79% of prescriptions, yet together they only comprise 17% of medications prescribed at an academic medical clinic that does not provide samples. The number of medications with samples being prescribed by dermatologists increased by 15% over 9 years, which may correlate with the wider availability of medication samples, more specifically an increase in branded generic samples.19 This potential interaction is the reason why institutions question the current influence of pharmaceutical companies. Samples may appear convenient, allowing a patient to test the medication prior to committing; however, with brand-name samples being provided to the physician, he/she may become more inclined to prescribe the branded medication.12,15,19-22 Because brand-name medications are more expensive than generic medications, this practice can increase the cost of health care.13 One study found that over 1 year, the overuse of nongeneric medications led to a loss of potential savings throughout 49 states, equating to $229 million just through Medicaid; interestingly, it was noted that in some states, a maximum reimbursement is set by Medicaid, regardless of whether the generic or branded medication is dispensed. The authors also noted variability in the potential savings by state, which may be a function of the state-by-state maximum reimbursements for certain medications.23 Another study on oral combination medications estimated Medicare spending on branded drugs relative to the cost if generic combinations had been purchased instead. This study examined branded medications for which the active components were available as over-the-counter (OTC), generic, or same-class generic, and the authors estimated that $925 million could have been saved in 2016 by purchasing a generic substitute.24 The overuse of nongeneric medications when generic alternatives are available becomes an issue that not only financially impacts patients but all taxpayers. However, this pattern may differ if limited only to dermatologic medications, which was not the focus of the prior studies.

To limit conflicts of interest in interactions with the pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology industries, the University of South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine (COM)(Tampa, Florida) implemented its own set of regulations that eliminated in-office pharmaceutical samples, in addition to other restrictions. This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after their medical school implemented these new policies.

We hypothesized that the number of brand-name drugs prescribed by physicians in the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery would change following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes. We sought to determine how physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery changed following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted to investigate the effect of the USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes on physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery. Medical records of patients seen for common dermatology diagnoses before (January 1, 2010, to May 30, 2010) and after (August 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011) the pharmaceutical policy changes were reviewed, and all medications prescribed were recorded. Data were collected from medical records within the USF Health electronic medical record system and included visits with each of the department’s 3 attending dermatologists. The diagnoses included in the study—acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, and rosacea—were chosen because in-office samples were available. Prescribing data from the first 100 consecutive medical records were collected from each time period, and a medical record was included only if it contained at least 1 of the following diagnoses: acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, or rosacea. The assessment and plan of each progress note were reviewed, and the exact medication name and associated diagnosis were recorded for each prescription. Subsequently, each medication was reviewed and placed in 1 of 3 categories: brand name, generic, and OTC. The total number of prescriptions for each diagnosis (per visit/note); the specific number of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note); and the percentage of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note and per diagnosis in total) were calculated. To ensure only intended medications were included, each medication recorded in the medical record note was cross-referenced with the prescribed medication in the electronic medical record. The primary objective of this study was to capture the prescribing physician’s intent as proxied by the pattern of prescription. Thus, changes made in prescriptions after the initial plan—whether insurance related or otherwise—were not relevant to this investigation.

The data were collected to compare the percentage of brand vs generic or OTC prescriptions per diagnosis to see if there was a difference in the prescribing habits before and after the pharmaceutical policy changes. Of note, several other pieces of data were collected from each medical record, including age, race, class of insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private health maintenance organization, private preferred provider organization), subtype diagnoses, and whether the prescription was new or a refill. The information gathered from the written record on the assessment and plan was verified using prescriptions ordered in the Allscripts electronic record, and any difference was noted. No identifying information that could be used to easily identify study participants was recorded.

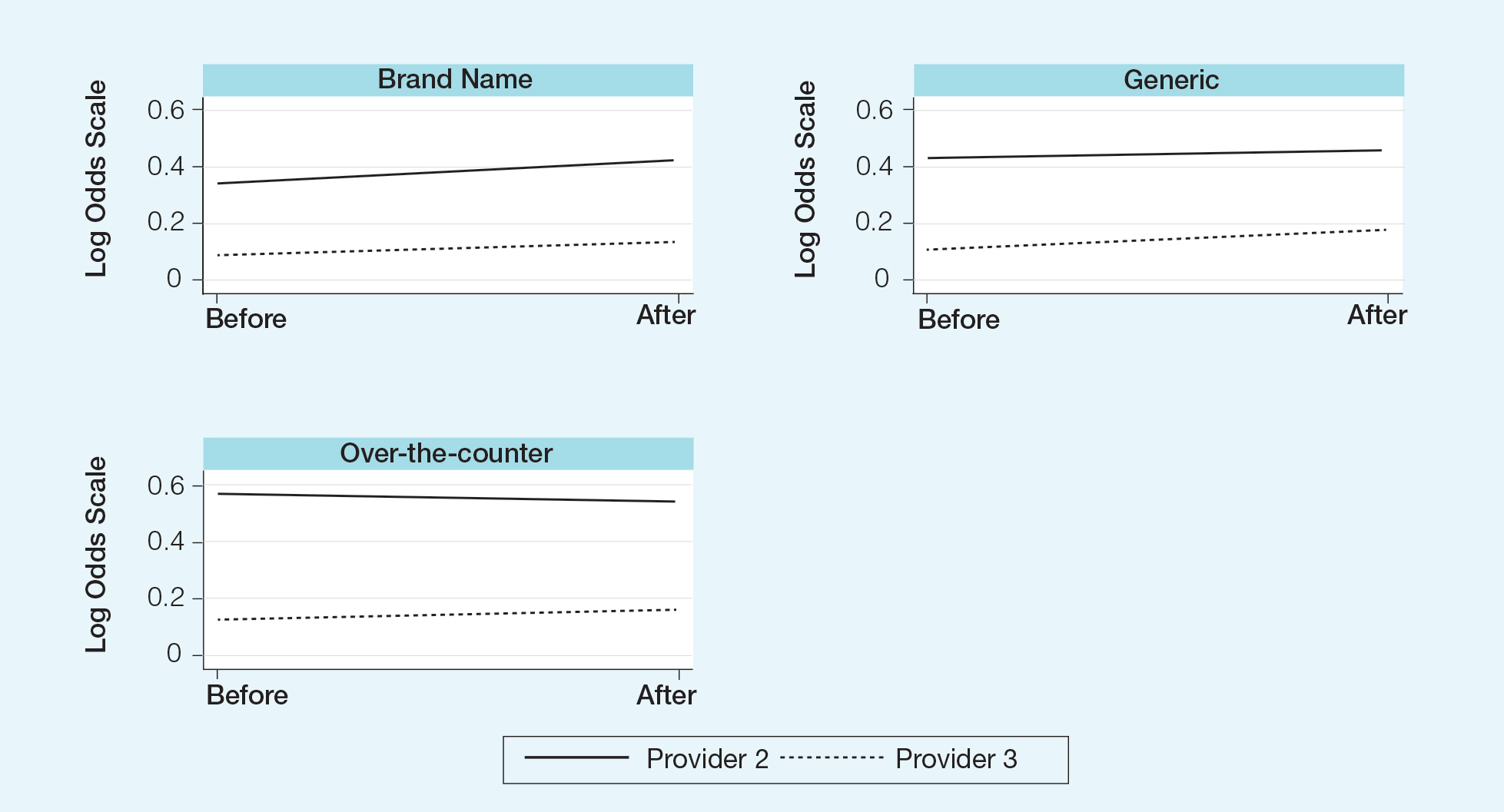

Differences in prescribing habits across diagnoses before and after the policy changes were ascertained using a Fisher exact test and were further assessed using a mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model that accounted for within-provider clustering and baseline patient characteristics. An ordinal model was chosen to recognize differences in average cost among brand-name, generic, and OTC medications.

Results

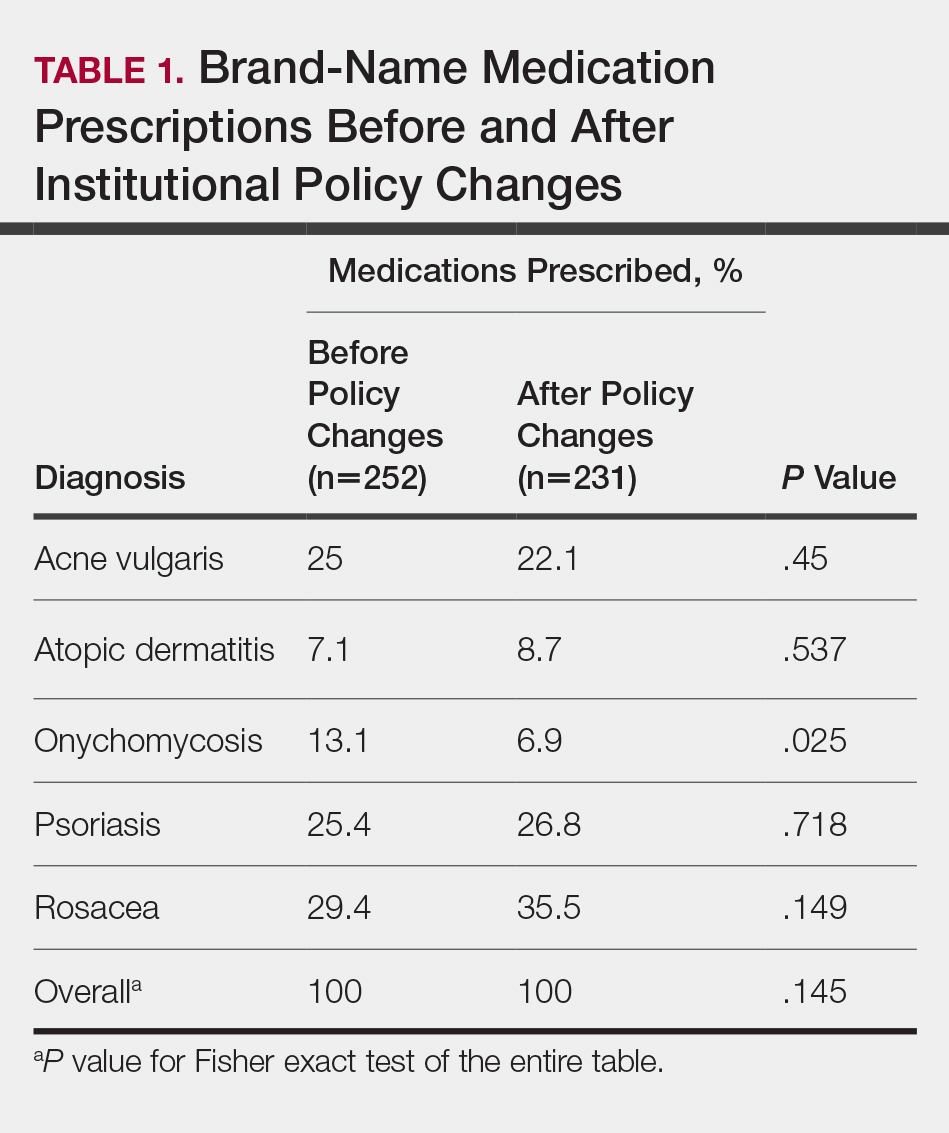

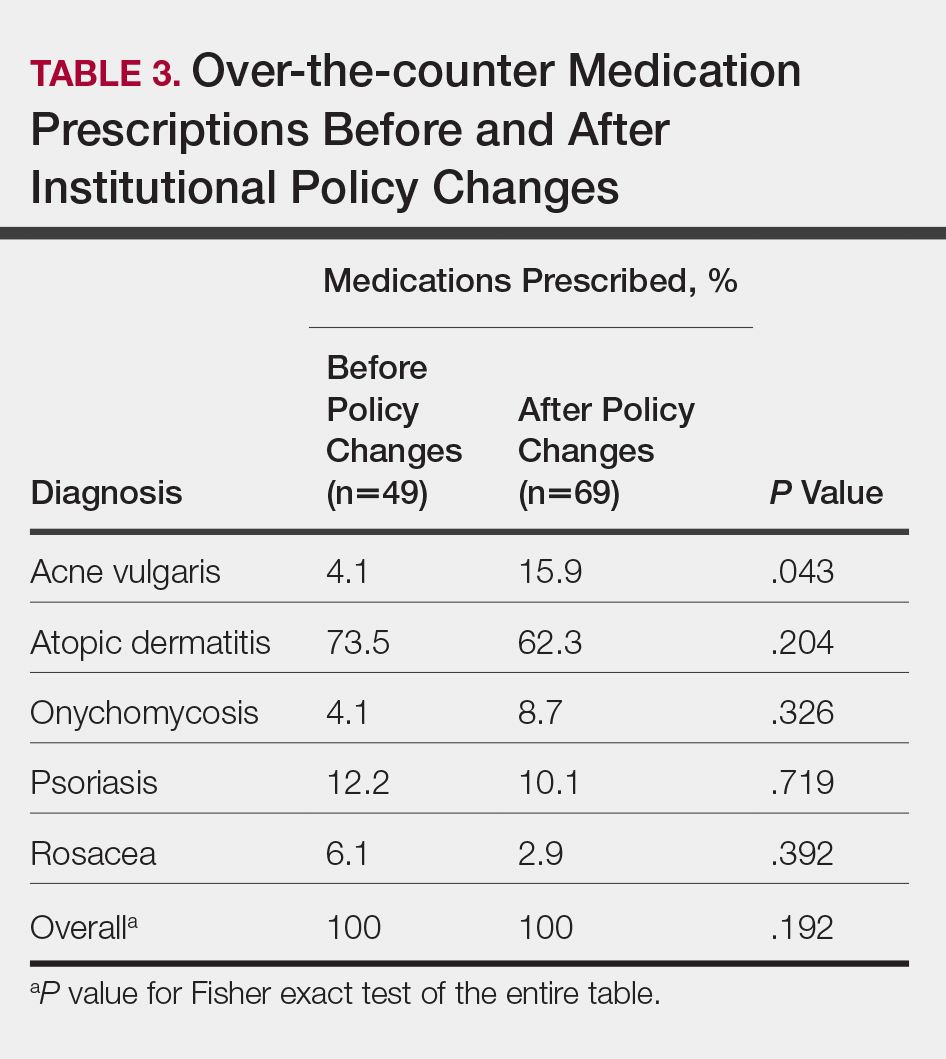

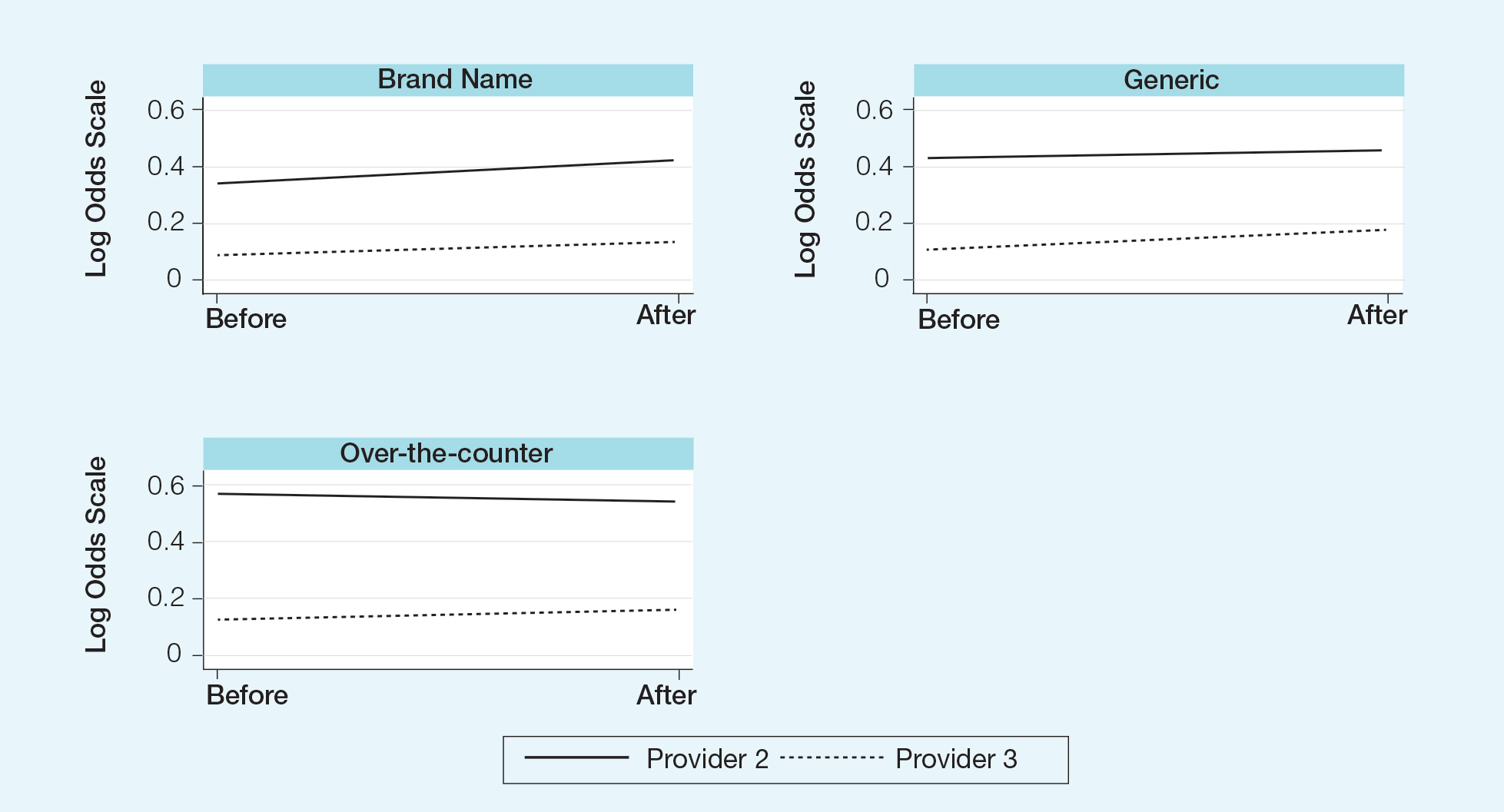

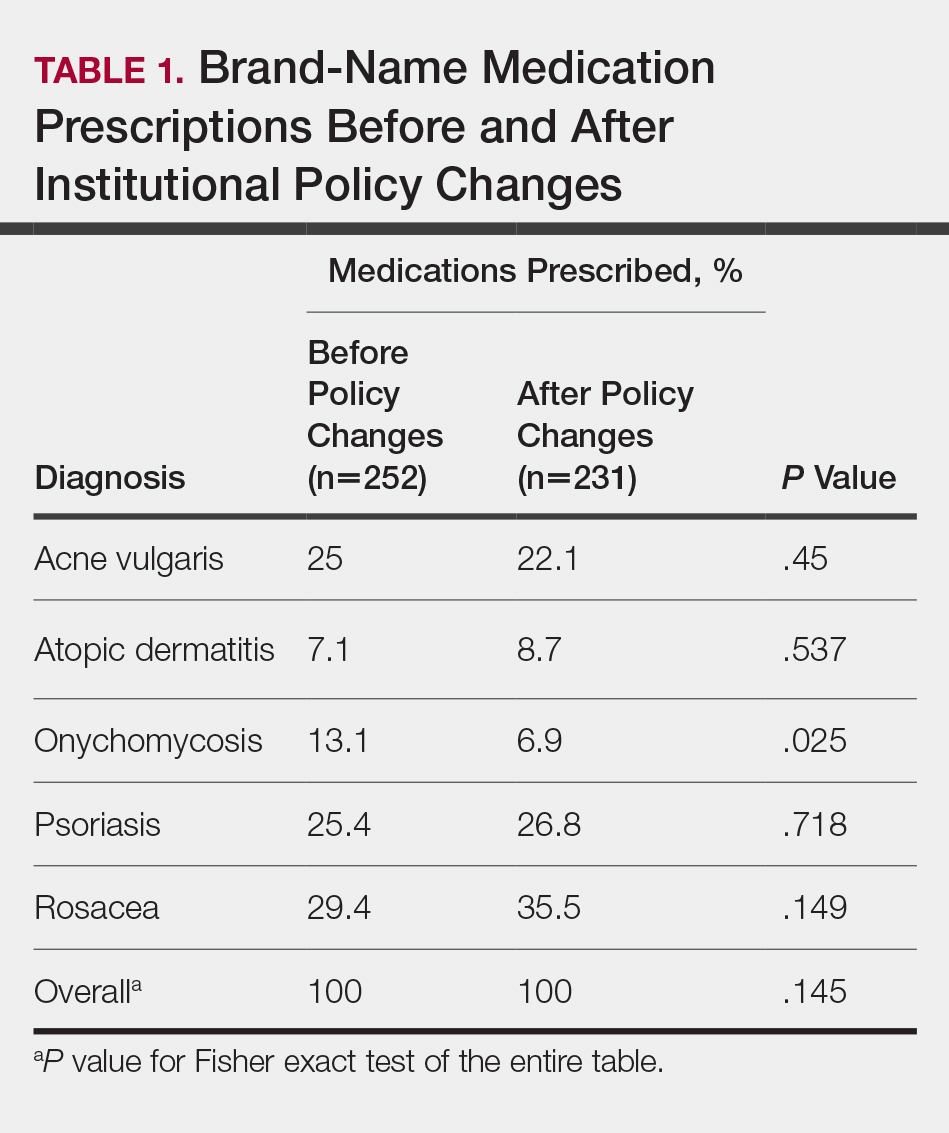

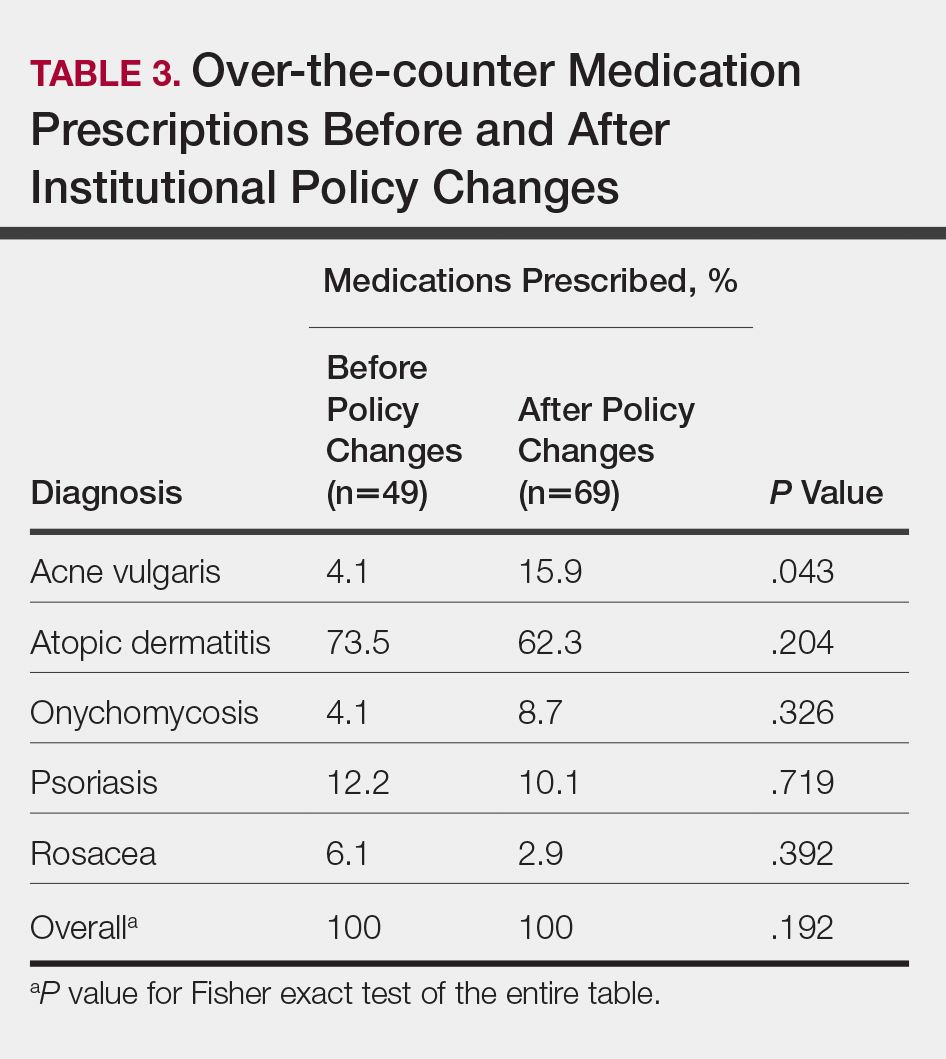

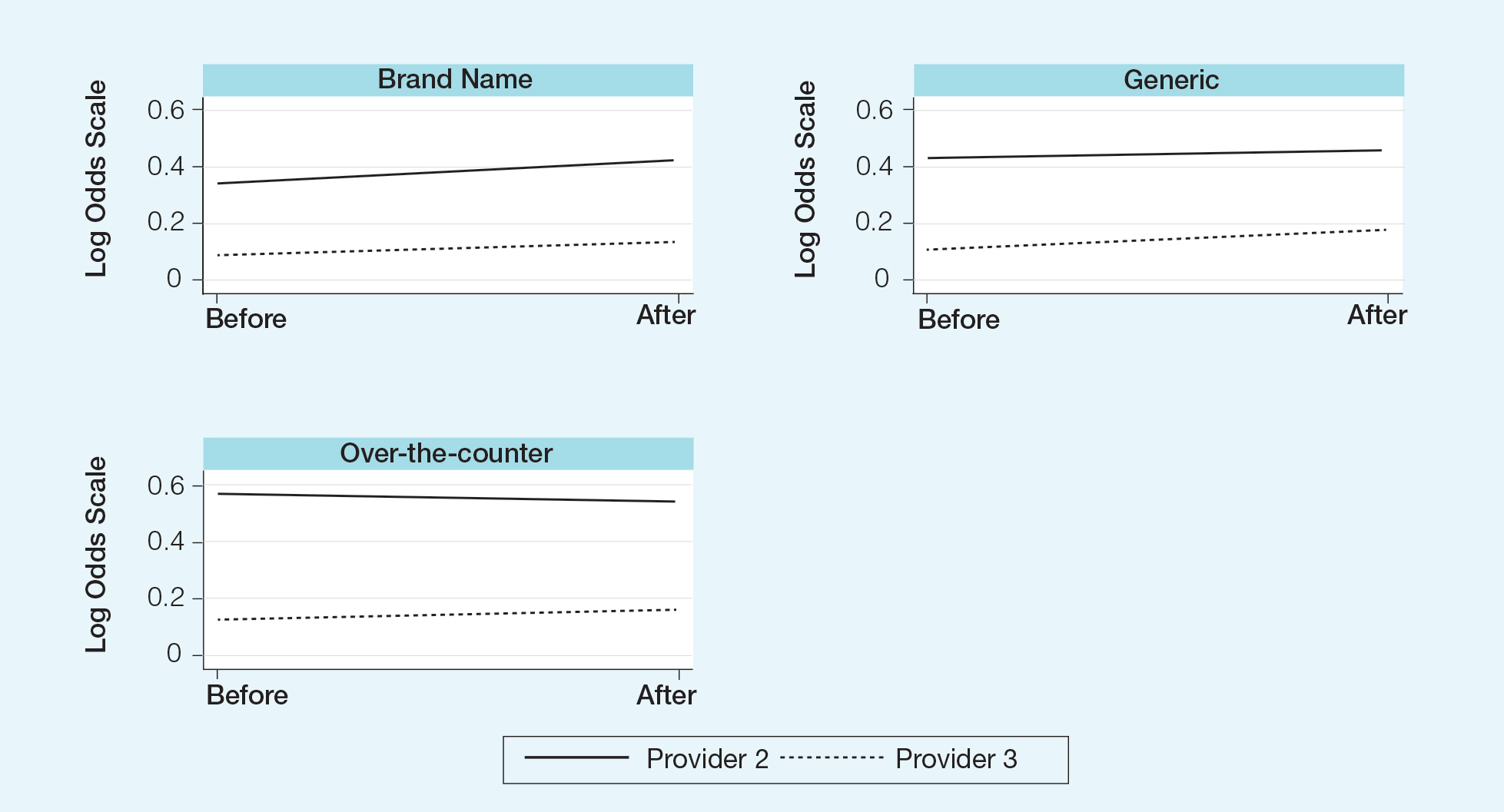

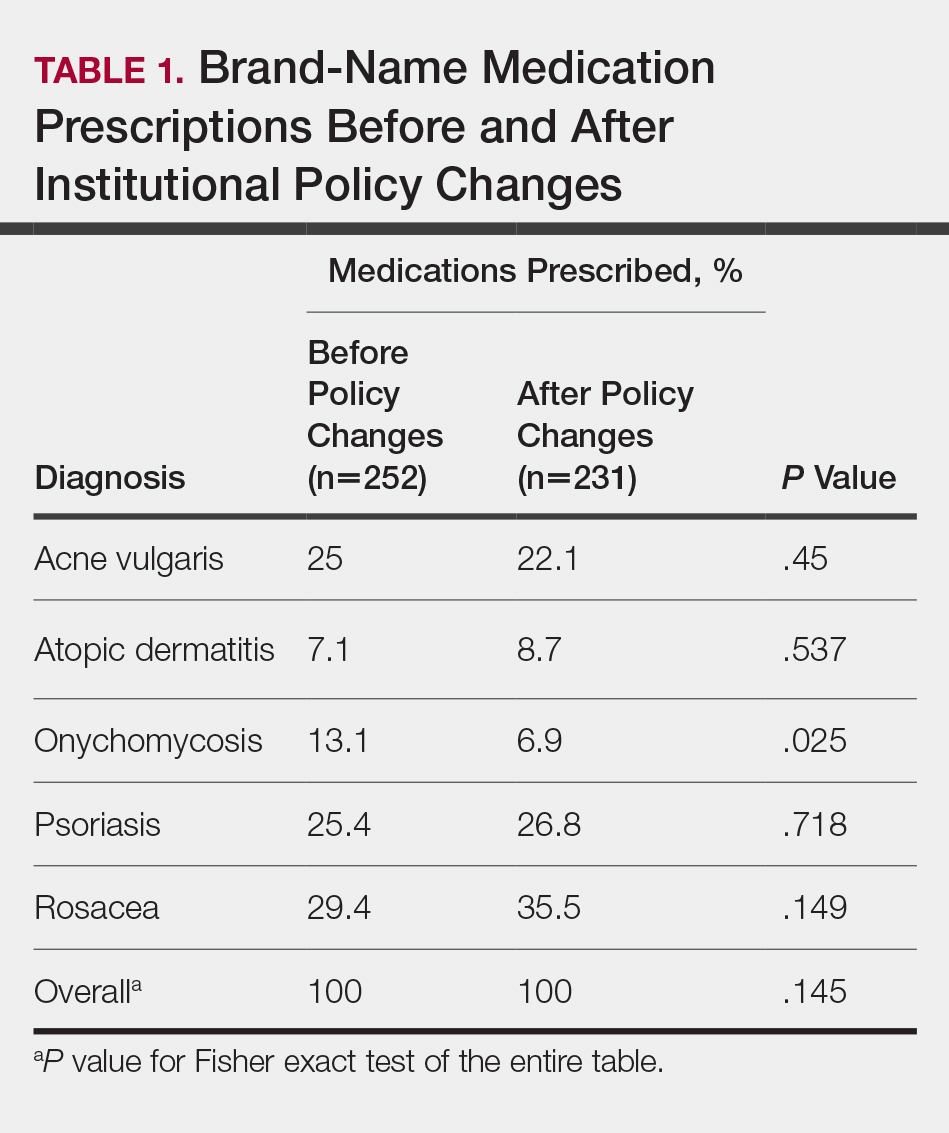

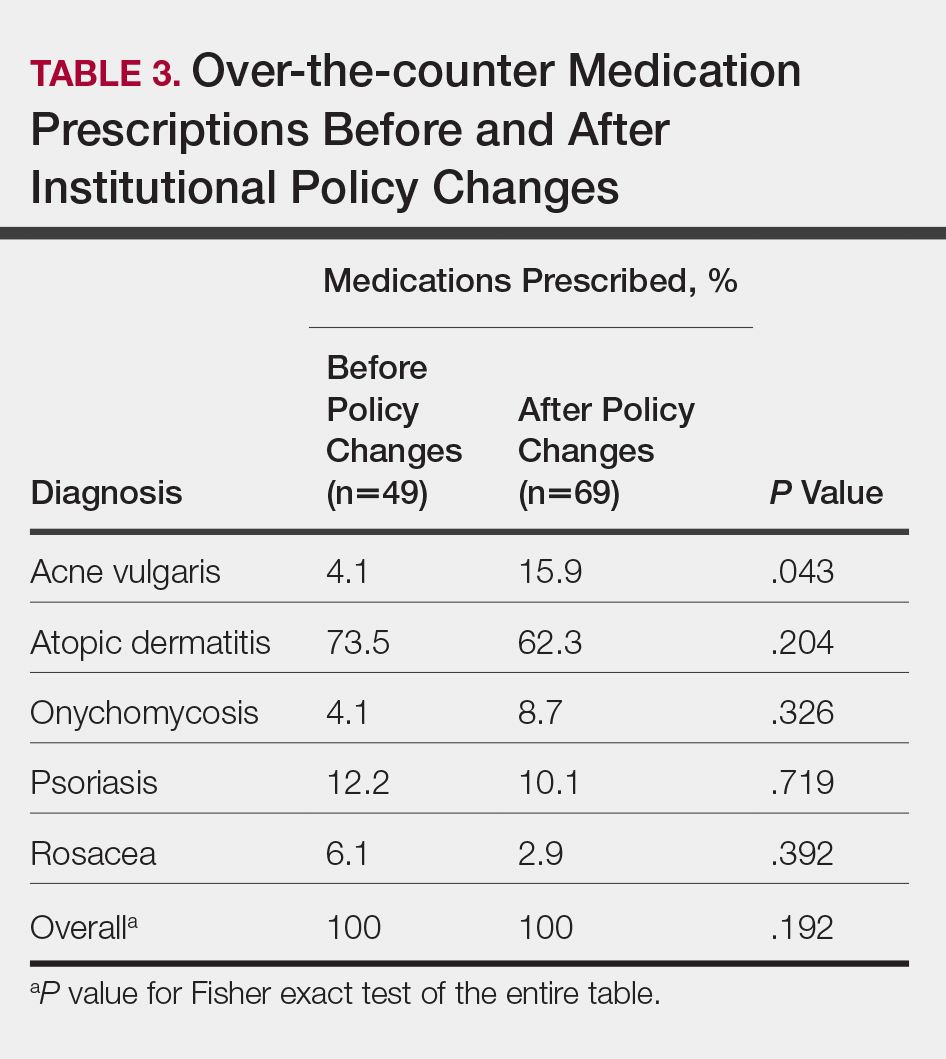

In total, 200 medical records were collected. For the period analyzed before the policy change, 252 brand-name medications were prescribed compared to 231 prescribed for the period analyzed after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in brand-name medications prescribed before and after the policy changes (P=.145; Fisher exact test)(Table 1). There also was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in generic prescriptions, which totaled 153 before and 134 after the policy changes (P=.872; Fisher exact test)(Table 2). Over-the-counter prescriptions totaled 49 before and 69 after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference before and after the policy changes for OTC medications (P=.192; Fisher exact test)(Table 3).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.

- Sondergaard J, Vach K, Kragstrup J, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical representative visits on GPs’ drug preferences. Fam Pract. 2009;26:204-209.

- Jelinek GA, Neate SL. The influence of the pharmaceutical industry in medicine. J Law Med. 2009;17:216-223.

- Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373-380.

- Coleman DL. Establishing policies for the relationship between industry and clinicians: lessons learned from two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2008;83:882-887.

- Coleman DL, Kazdin AE, Miller LA, et al. Guidelines for interactions between clinical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry: one medical school’s approach. Acad Med. 2006;81:154-160.

- Evans D, Hartung DM, Beasley D, et al. Breaking up is hard to do: lessons learned from a pharma-free practice transformation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:332-338.

- Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583-1597.

- Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514-2526.

- McCormack J, Chmelicek JT. Generic versus brand name: the other drug war. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:911.

- Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1578-1592.

- Garrison GD, Levin GM. Factors affecting prescribing of the newer antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:10-14.

- Rafique S, Sarwar W, Rashid A, et al. Influence of free drug samples on prescribing by physicians: a cross sectional survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:465-467.

- Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394-402.

- Hodges B. Interactions with the pharmaceutical industry: experiences and attitudes of psychiatry residents, interns and clerks. CMAJ. 1995;153:553-559.

- Brotzman GL, Mark DH. The effect on resident attitudes of regulatory policies regarding pharmaceutical representative activities. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:130-134.

- Keim SM, Sanders AB, Witzke DB, et al. Beliefs and practices of emergency medicine faculty and residents regarding professional interactions with the biomedical industry. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1576-1581.

- Thomson AN, Craig BJ, Barham PM. Attitudes of general practitioners in New Zealand to pharmaceutical representatives. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:220-223.

- Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273:1296-1298.

- Hurley MP, Stafford RS, Lane AT. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:487-493.

- Lexchin J. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: what does the literature say? CMAJ. 1993;149:1401-1407.

- Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110130.

- Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352.

- Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic consequences of underuse of generic drugs: evidence from Medicaid and implications for prescription drug benefit plans. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1051-1064.

- Sacks CA, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, et al. Medicare spending on brand-name combination medications vs their generic constituents. JAMA. 2018;320:650-656.

- Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429-433.

- Allan GM, Lexchin J, Wiebe N. Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e283.

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3

A 2014 study reported that prescribing habits are influenced by the free drug samples provided by nongeneric pharmaceutical companies.19 Nationally, the number of brand-name and branded generic medications constitute 79% of prescriptions, yet together they only comprise 17% of medications prescribed at an academic medical clinic that does not provide samples. The number of medications with samples being prescribed by dermatologists increased by 15% over 9 years, which may correlate with the wider availability of medication samples, more specifically an increase in branded generic samples.19 This potential interaction is the reason why institutions question the current influence of pharmaceutical companies. Samples may appear convenient, allowing a patient to test the medication prior to committing; however, with brand-name samples being provided to the physician, he/she may become more inclined to prescribe the branded medication.12,15,19-22 Because brand-name medications are more expensive than generic medications, this practice can increase the cost of health care.13 One study found that over 1 year, the overuse of nongeneric medications led to a loss of potential savings throughout 49 states, equating to $229 million just through Medicaid; interestingly, it was noted that in some states, a maximum reimbursement is set by Medicaid, regardless of whether the generic or branded medication is dispensed. The authors also noted variability in the potential savings by state, which may be a function of the state-by-state maximum reimbursements for certain medications.23 Another study on oral combination medications estimated Medicare spending on branded drugs relative to the cost if generic combinations had been purchased instead. This study examined branded medications for which the active components were available as over-the-counter (OTC), generic, or same-class generic, and the authors estimated that $925 million could have been saved in 2016 by purchasing a generic substitute.24 The overuse of nongeneric medications when generic alternatives are available becomes an issue that not only financially impacts patients but all taxpayers. However, this pattern may differ if limited only to dermatologic medications, which was not the focus of the prior studies.

To limit conflicts of interest in interactions with the pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology industries, the University of South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine (COM)(Tampa, Florida) implemented its own set of regulations that eliminated in-office pharmaceutical samples, in addition to other restrictions. This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after their medical school implemented these new policies.

We hypothesized that the number of brand-name drugs prescribed by physicians in the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery would change following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes. We sought to determine how physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery changed following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted to investigate the effect of the USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes on physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery. Medical records of patients seen for common dermatology diagnoses before (January 1, 2010, to May 30, 2010) and after (August 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011) the pharmaceutical policy changes were reviewed, and all medications prescribed were recorded. Data were collected from medical records within the USF Health electronic medical record system and included visits with each of the department’s 3 attending dermatologists. The diagnoses included in the study—acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, and rosacea—were chosen because in-office samples were available. Prescribing data from the first 100 consecutive medical records were collected from each time period, and a medical record was included only if it contained at least 1 of the following diagnoses: acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, or rosacea. The assessment and plan of each progress note were reviewed, and the exact medication name and associated diagnosis were recorded for each prescription. Subsequently, each medication was reviewed and placed in 1 of 3 categories: brand name, generic, and OTC. The total number of prescriptions for each diagnosis (per visit/note); the specific number of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note); and the percentage of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note and per diagnosis in total) were calculated. To ensure only intended medications were included, each medication recorded in the medical record note was cross-referenced with the prescribed medication in the electronic medical record. The primary objective of this study was to capture the prescribing physician’s intent as proxied by the pattern of prescription. Thus, changes made in prescriptions after the initial plan—whether insurance related or otherwise—were not relevant to this investigation.

The data were collected to compare the percentage of brand vs generic or OTC prescriptions per diagnosis to see if there was a difference in the prescribing habits before and after the pharmaceutical policy changes. Of note, several other pieces of data were collected from each medical record, including age, race, class of insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private health maintenance organization, private preferred provider organization), subtype diagnoses, and whether the prescription was new or a refill. The information gathered from the written record on the assessment and plan was verified using prescriptions ordered in the Allscripts electronic record, and any difference was noted. No identifying information that could be used to easily identify study participants was recorded.

Differences in prescribing habits across diagnoses before and after the policy changes were ascertained using a Fisher exact test and were further assessed using a mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model that accounted for within-provider clustering and baseline patient characteristics. An ordinal model was chosen to recognize differences in average cost among brand-name, generic, and OTC medications.

Results

In total, 200 medical records were collected. For the period analyzed before the policy change, 252 brand-name medications were prescribed compared to 231 prescribed for the period analyzed after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in brand-name medications prescribed before and after the policy changes (P=.145; Fisher exact test)(Table 1). There also was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in generic prescriptions, which totaled 153 before and 134 after the policy changes (P=.872; Fisher exact test)(Table 2). Over-the-counter prescriptions totaled 49 before and 69 after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference before and after the policy changes for OTC medications (P=.192; Fisher exact test)(Table 3).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3