User login

Transitioning patients with opioid use disorder from methadone to buprenorphine

Mr. M, age 46, has opioid use disorder (OUD). He is currently stabilized on methadone 80 mg/d but presents to your hospital with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. After Mr. M is admitted, the care team looks to start amiodarone; however, they receive notice of a drug-drug interaction that may cause QTc prolongation. Mr. M agrees to switch to another medication to treat his OUD because he is tired of the regulated process required to receive methadone. The care team would like to taper him to a different OUD medication but would like Mr. M to avoid cravings, symptoms of withdrawal, and potential relapse.

The opioid epidemic has devastated the United States, causing approximately 130 deaths per day.1 The economic burden of this epidemic on medical, social welfare, and correctional services is approximately $1 trillion annually.2 Research supports opioid replacement therapy for treating OUD.1 Multiple types of opioid replacement therapies are available in multiple dosage forms; all act on the mu-opioid receptor. These include full agonist treatment (eg, methadone) and partial agonist treatment (eg, buprenorphine).3 Alternatively, opioid antagonist therapies (eg, naltrexone) have also been found to be effective for treating OUD.1,2,4 This article focuses on partial agonist treatment for OUD, specifically using a buprenorphine microdosing strategy to transition a patient from methadone to buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine for OUD

Buprenorphine binds with high affinity to the mu-opioid receptor, resulting in partial agonism of the receptor.1,2 Buprenorphine has a higher therapeutic index and lower intrinsic agonist activity than other opioids and a low incidence of adverse effects. Due to the partial agonism at the mu receptor, its analgesic effects plateau at higher doses and exhibit antagonist properties.1,2 This distinct “ceiling” effect, combined with a lower risk of respiratory depression, makes buprenorphine significantly safer than methadone.4 Additionally, it has a lower potential for misuse when used with an abuse deterrent such as naloxone.

Common reasons for transitioning a patient from methadone to buprenorphine include intolerable adverse effects of methadone, variable duration of efficacy, drug-drug interactions, or limited access to an opioid treatment program. Traditional buprenorphine induction requires moderate withdrawal before initiating therapy. Due to buprenorphine’s high affinity and partial agonism at the mu receptor, it competes with other opioids (eg, heroin, methadone) and will abruptly displace the receptor’s full agonist with a lower affinity, resulting in precipitated withdrawal.1,3,5 To avoid precipitated withdrawal, it is recommended to leave a sufficient amount of time between full opioid agonist treatment and buprenorphine treatment, a process called “opioid washout.”1,5 Depending on the duration, amount, and specific opioid used, the amount of time between ending opioid agonist treatment and initiating buprenorphine treatment may vary. As a result, many patients who attempt to transition from methadone to buprenorphine remain on methadone due to their inability to tolerate withdrawal. Additionally, given the risk of precipitating withdrawal, initiating buprenorphine may negatively impact pain control.1

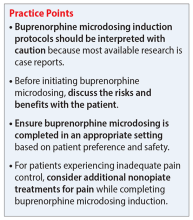

Recently, buprenorphine “microdosing” inductions, which do not require patients to be in opioid withdrawal, have been used to overcome some of the challenges of transitioning patients from methadone to buprenorphine.2

Buprenorphine microdosing techniques

Multiple methods of microdosing buprenorphine have been used in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Bernese method. In 1997, Mendelson et al6 completed a trial with 5 patients maintained on methadone. They found that IV buprenorphine 0.2 mg every 24 hours did not produce a withdrawal effect and was comparable to placebo.6 Haamig et al5 hypothesized that repetitive administration of buprenorphine at minute doses in adequate dosing intervals would not cause withdrawal. Additionally, because of its high receptor binding affinity, buprenorphine will accumulate over time at the mu receptor. Thus, eventually the full mu agonist (eg, methadone) will be replaced by buprenorphine at the mu receptor as the receptor becomes saturated.4,5

Continue to: The goal is to taper...

The goal is to taper the opioid agonist therapy while titrating buprenorphine. This taper method is not described in current treatment guidelines, and as a result, there are differences in doses used in each taper because the amount of opioid agonist and type of opioid agonist therapy can vary. In most cases, buprenorphine is initiated at 0.25 mg/d to 0.5 mg/d and increased by 0.25 mg/d to 1 mg/d as tolerated.4,5 The dose of the full opioid agonist is slowly decreased as the buprenorphine dose increases. The Bernese method does not require frequent dosing, so it is a favorable option for outpatient therapy.4 One limitation to this method is that it is necessary to divide tablets into small doses.4 Additionally, adherence issues may disrupt the tapering method; therefore, some patients may not be appropriate candidates.4

Transdermal patch method. This method aims to provide a consistent amount of buprenorphine—similar to dividing tablets into smaller doses as seen in the Bernese method—but with the goal of avoiding inconsistencies in dosing. Hess et al7 examined 22 patients with OUD who were maintained on methadone 60 mg/d to 100 mg/d. In the buprenorphine transdermal patch method, a 35 mcg/h buprenorphine patch was applied 12 hours after the patient’s final methadone dose.1,7 This was intended to provide continuous delivery over 96 hours.1 Additionally, small, incremental doses of sublingual buprenorphine (SL-BUP) were administered throughout the course of 5 days.1 A potential strength of this method is that like the Bernese method, it may be completed in outpatient therapy.4 Potential limitations include time to initiation, off-label use, and related costs.

Rapid microdosing induction method. Contrary to typical microdosing, rapid microdosing induction requires buprenorphine to be administered every 3 to 4 hours.4 As with most buprenorphine microinduction protocols, this does not require a period of withdrawal prior to initiation and may be performed because of the 1-hour time to peak effect of buprenorphine.4 Due to the frequent dosing schedule, it is recommended to use this method in an inpatient setting.4 With rapid microdosing, an individual may receive SL-BUP 0.5 mg every 3 hours on Day 1, then 1 mg SL-BUP every 3 hours on Day 2. On Day 3, the individual may receive 12 mg SL-BUP with 2 mg as needed. A limitation of this method is that it must be performed in an inpatient setting.4

CASE CONTINUED

To ensure patient-inclusive care, clinicians should conduct a risk-benefit discussion with the patient regarding microdosing buprenorphine. Because Mr. M would like to be managed as an outpatient, rapid microdosing is not an option. Mr. M works with his care team to design a microdosing approach with the Bernese method. They initiate buprenorphine 0.5 mg/d and increase the dose by 0.5 mg to 1 mg from Day 2 to Day 8. The variance in buprenorphine titration occurs due to Mr. M’s tolerance and symptoms of withdrawal. The team decreases the methadone dose by 5 mg to 10 mg each day, depending on symptoms of withdrawal, and discontinues therapy on Day 8. Throughout the microdosing induction, Mr. M does not experience withdrawal symptoms and is now managed on buprenorphine 12 mg/d.

Related Resources

- Van Hale C, Gluck R, Tang Y. Laboratory monitoring for patients on buprenorphine: 10 questions. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):12-15,20-21,26.

- Moreno JL, Johnson JL, Peckham AM. Sublingual buprenorphine plus buprenorphine XR for opioid use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):39-42,49.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Buprenorphine • Subutex, Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

1. Ahmed S, Bhivandkar S, Lonergan B, et al. Microinduction of buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of the literature. Am J Addict. 2021;30:305-315.

2. De Aquino JP, Fairgrieve C, Klair S, et al. Rapid transition from methadone to buprenorphine utilizing a micro-dosing protocol in the outpatient veteran affairs setting. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e271-e273.

3. Lintzeris N, Monds LA, Rivas C, et al. Transferring patients from methadone to buprenorphine: the feasibility and evaluation of practice guidelines. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):234-240.

4. Ghosh SM, Klaire S, Tanguay R, et al. A review of novel methods to support the transition from methadone and other full agonist opioids to buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual in both community and acute care settings. Can J Addict. 2019;10:41-50.

5. Haamig R, Kemter A, Strasser J, et al. Use of microdoses for induction of buprenorphine treatment with overlapping full opioid agonist use: the Bernese method. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:99-105.

6. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1095-1101.

7. Hess M, Boesch L, Leisinger R, et al. Transdermal buprenorphine to switch patients from higher dose methadone to buprenorphine without severe withdrawal symptoms. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):480‐481.

Mr. M, age 46, has opioid use disorder (OUD). He is currently stabilized on methadone 80 mg/d but presents to your hospital with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. After Mr. M is admitted, the care team looks to start amiodarone; however, they receive notice of a drug-drug interaction that may cause QTc prolongation. Mr. M agrees to switch to another medication to treat his OUD because he is tired of the regulated process required to receive methadone. The care team would like to taper him to a different OUD medication but would like Mr. M to avoid cravings, symptoms of withdrawal, and potential relapse.

The opioid epidemic has devastated the United States, causing approximately 130 deaths per day.1 The economic burden of this epidemic on medical, social welfare, and correctional services is approximately $1 trillion annually.2 Research supports opioid replacement therapy for treating OUD.1 Multiple types of opioid replacement therapies are available in multiple dosage forms; all act on the mu-opioid receptor. These include full agonist treatment (eg, methadone) and partial agonist treatment (eg, buprenorphine).3 Alternatively, opioid antagonist therapies (eg, naltrexone) have also been found to be effective for treating OUD.1,2,4 This article focuses on partial agonist treatment for OUD, specifically using a buprenorphine microdosing strategy to transition a patient from methadone to buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine for OUD

Buprenorphine binds with high affinity to the mu-opioid receptor, resulting in partial agonism of the receptor.1,2 Buprenorphine has a higher therapeutic index and lower intrinsic agonist activity than other opioids and a low incidence of adverse effects. Due to the partial agonism at the mu receptor, its analgesic effects plateau at higher doses and exhibit antagonist properties.1,2 This distinct “ceiling” effect, combined with a lower risk of respiratory depression, makes buprenorphine significantly safer than methadone.4 Additionally, it has a lower potential for misuse when used with an abuse deterrent such as naloxone.

Common reasons for transitioning a patient from methadone to buprenorphine include intolerable adverse effects of methadone, variable duration of efficacy, drug-drug interactions, or limited access to an opioid treatment program. Traditional buprenorphine induction requires moderate withdrawal before initiating therapy. Due to buprenorphine’s high affinity and partial agonism at the mu receptor, it competes with other opioids (eg, heroin, methadone) and will abruptly displace the receptor’s full agonist with a lower affinity, resulting in precipitated withdrawal.1,3,5 To avoid precipitated withdrawal, it is recommended to leave a sufficient amount of time between full opioid agonist treatment and buprenorphine treatment, a process called “opioid washout.”1,5 Depending on the duration, amount, and specific opioid used, the amount of time between ending opioid agonist treatment and initiating buprenorphine treatment may vary. As a result, many patients who attempt to transition from methadone to buprenorphine remain on methadone due to their inability to tolerate withdrawal. Additionally, given the risk of precipitating withdrawal, initiating buprenorphine may negatively impact pain control.1

Recently, buprenorphine “microdosing” inductions, which do not require patients to be in opioid withdrawal, have been used to overcome some of the challenges of transitioning patients from methadone to buprenorphine.2

Buprenorphine microdosing techniques

Multiple methods of microdosing buprenorphine have been used in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Bernese method. In 1997, Mendelson et al6 completed a trial with 5 patients maintained on methadone. They found that IV buprenorphine 0.2 mg every 24 hours did not produce a withdrawal effect and was comparable to placebo.6 Haamig et al5 hypothesized that repetitive administration of buprenorphine at minute doses in adequate dosing intervals would not cause withdrawal. Additionally, because of its high receptor binding affinity, buprenorphine will accumulate over time at the mu receptor. Thus, eventually the full mu agonist (eg, methadone) will be replaced by buprenorphine at the mu receptor as the receptor becomes saturated.4,5

Continue to: The goal is to taper...

The goal is to taper the opioid agonist therapy while titrating buprenorphine. This taper method is not described in current treatment guidelines, and as a result, there are differences in doses used in each taper because the amount of opioid agonist and type of opioid agonist therapy can vary. In most cases, buprenorphine is initiated at 0.25 mg/d to 0.5 mg/d and increased by 0.25 mg/d to 1 mg/d as tolerated.4,5 The dose of the full opioid agonist is slowly decreased as the buprenorphine dose increases. The Bernese method does not require frequent dosing, so it is a favorable option for outpatient therapy.4 One limitation to this method is that it is necessary to divide tablets into small doses.4 Additionally, adherence issues may disrupt the tapering method; therefore, some patients may not be appropriate candidates.4

Transdermal patch method. This method aims to provide a consistent amount of buprenorphine—similar to dividing tablets into smaller doses as seen in the Bernese method—but with the goal of avoiding inconsistencies in dosing. Hess et al7 examined 22 patients with OUD who were maintained on methadone 60 mg/d to 100 mg/d. In the buprenorphine transdermal patch method, a 35 mcg/h buprenorphine patch was applied 12 hours after the patient’s final methadone dose.1,7 This was intended to provide continuous delivery over 96 hours.1 Additionally, small, incremental doses of sublingual buprenorphine (SL-BUP) were administered throughout the course of 5 days.1 A potential strength of this method is that like the Bernese method, it may be completed in outpatient therapy.4 Potential limitations include time to initiation, off-label use, and related costs.

Rapid microdosing induction method. Contrary to typical microdosing, rapid microdosing induction requires buprenorphine to be administered every 3 to 4 hours.4 As with most buprenorphine microinduction protocols, this does not require a period of withdrawal prior to initiation and may be performed because of the 1-hour time to peak effect of buprenorphine.4 Due to the frequent dosing schedule, it is recommended to use this method in an inpatient setting.4 With rapid microdosing, an individual may receive SL-BUP 0.5 mg every 3 hours on Day 1, then 1 mg SL-BUP every 3 hours on Day 2. On Day 3, the individual may receive 12 mg SL-BUP with 2 mg as needed. A limitation of this method is that it must be performed in an inpatient setting.4

CASE CONTINUED

To ensure patient-inclusive care, clinicians should conduct a risk-benefit discussion with the patient regarding microdosing buprenorphine. Because Mr. M would like to be managed as an outpatient, rapid microdosing is not an option. Mr. M works with his care team to design a microdosing approach with the Bernese method. They initiate buprenorphine 0.5 mg/d and increase the dose by 0.5 mg to 1 mg from Day 2 to Day 8. The variance in buprenorphine titration occurs due to Mr. M’s tolerance and symptoms of withdrawal. The team decreases the methadone dose by 5 mg to 10 mg each day, depending on symptoms of withdrawal, and discontinues therapy on Day 8. Throughout the microdosing induction, Mr. M does not experience withdrawal symptoms and is now managed on buprenorphine 12 mg/d.

Related Resources

- Van Hale C, Gluck R, Tang Y. Laboratory monitoring for patients on buprenorphine: 10 questions. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):12-15,20-21,26.

- Moreno JL, Johnson JL, Peckham AM. Sublingual buprenorphine plus buprenorphine XR for opioid use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):39-42,49.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Buprenorphine • Subutex, Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Mr. M, age 46, has opioid use disorder (OUD). He is currently stabilized on methadone 80 mg/d but presents to your hospital with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. After Mr. M is admitted, the care team looks to start amiodarone; however, they receive notice of a drug-drug interaction that may cause QTc prolongation. Mr. M agrees to switch to another medication to treat his OUD because he is tired of the regulated process required to receive methadone. The care team would like to taper him to a different OUD medication but would like Mr. M to avoid cravings, symptoms of withdrawal, and potential relapse.

The opioid epidemic has devastated the United States, causing approximately 130 deaths per day.1 The economic burden of this epidemic on medical, social welfare, and correctional services is approximately $1 trillion annually.2 Research supports opioid replacement therapy for treating OUD.1 Multiple types of opioid replacement therapies are available in multiple dosage forms; all act on the mu-opioid receptor. These include full agonist treatment (eg, methadone) and partial agonist treatment (eg, buprenorphine).3 Alternatively, opioid antagonist therapies (eg, naltrexone) have also been found to be effective for treating OUD.1,2,4 This article focuses on partial agonist treatment for OUD, specifically using a buprenorphine microdosing strategy to transition a patient from methadone to buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine for OUD

Buprenorphine binds with high affinity to the mu-opioid receptor, resulting in partial agonism of the receptor.1,2 Buprenorphine has a higher therapeutic index and lower intrinsic agonist activity than other opioids and a low incidence of adverse effects. Due to the partial agonism at the mu receptor, its analgesic effects plateau at higher doses and exhibit antagonist properties.1,2 This distinct “ceiling” effect, combined with a lower risk of respiratory depression, makes buprenorphine significantly safer than methadone.4 Additionally, it has a lower potential for misuse when used with an abuse deterrent such as naloxone.

Common reasons for transitioning a patient from methadone to buprenorphine include intolerable adverse effects of methadone, variable duration of efficacy, drug-drug interactions, or limited access to an opioid treatment program. Traditional buprenorphine induction requires moderate withdrawal before initiating therapy. Due to buprenorphine’s high affinity and partial agonism at the mu receptor, it competes with other opioids (eg, heroin, methadone) and will abruptly displace the receptor’s full agonist with a lower affinity, resulting in precipitated withdrawal.1,3,5 To avoid precipitated withdrawal, it is recommended to leave a sufficient amount of time between full opioid agonist treatment and buprenorphine treatment, a process called “opioid washout.”1,5 Depending on the duration, amount, and specific opioid used, the amount of time between ending opioid agonist treatment and initiating buprenorphine treatment may vary. As a result, many patients who attempt to transition from methadone to buprenorphine remain on methadone due to their inability to tolerate withdrawal. Additionally, given the risk of precipitating withdrawal, initiating buprenorphine may negatively impact pain control.1

Recently, buprenorphine “microdosing” inductions, which do not require patients to be in opioid withdrawal, have been used to overcome some of the challenges of transitioning patients from methadone to buprenorphine.2

Buprenorphine microdosing techniques

Multiple methods of microdosing buprenorphine have been used in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Bernese method. In 1997, Mendelson et al6 completed a trial with 5 patients maintained on methadone. They found that IV buprenorphine 0.2 mg every 24 hours did not produce a withdrawal effect and was comparable to placebo.6 Haamig et al5 hypothesized that repetitive administration of buprenorphine at minute doses in adequate dosing intervals would not cause withdrawal. Additionally, because of its high receptor binding affinity, buprenorphine will accumulate over time at the mu receptor. Thus, eventually the full mu agonist (eg, methadone) will be replaced by buprenorphine at the mu receptor as the receptor becomes saturated.4,5

Continue to: The goal is to taper...

The goal is to taper the opioid agonist therapy while titrating buprenorphine. This taper method is not described in current treatment guidelines, and as a result, there are differences in doses used in each taper because the amount of opioid agonist and type of opioid agonist therapy can vary. In most cases, buprenorphine is initiated at 0.25 mg/d to 0.5 mg/d and increased by 0.25 mg/d to 1 mg/d as tolerated.4,5 The dose of the full opioid agonist is slowly decreased as the buprenorphine dose increases. The Bernese method does not require frequent dosing, so it is a favorable option for outpatient therapy.4 One limitation to this method is that it is necessary to divide tablets into small doses.4 Additionally, adherence issues may disrupt the tapering method; therefore, some patients may not be appropriate candidates.4

Transdermal patch method. This method aims to provide a consistent amount of buprenorphine—similar to dividing tablets into smaller doses as seen in the Bernese method—but with the goal of avoiding inconsistencies in dosing. Hess et al7 examined 22 patients with OUD who were maintained on methadone 60 mg/d to 100 mg/d. In the buprenorphine transdermal patch method, a 35 mcg/h buprenorphine patch was applied 12 hours after the patient’s final methadone dose.1,7 This was intended to provide continuous delivery over 96 hours.1 Additionally, small, incremental doses of sublingual buprenorphine (SL-BUP) were administered throughout the course of 5 days.1 A potential strength of this method is that like the Bernese method, it may be completed in outpatient therapy.4 Potential limitations include time to initiation, off-label use, and related costs.

Rapid microdosing induction method. Contrary to typical microdosing, rapid microdosing induction requires buprenorphine to be administered every 3 to 4 hours.4 As with most buprenorphine microinduction protocols, this does not require a period of withdrawal prior to initiation and may be performed because of the 1-hour time to peak effect of buprenorphine.4 Due to the frequent dosing schedule, it is recommended to use this method in an inpatient setting.4 With rapid microdosing, an individual may receive SL-BUP 0.5 mg every 3 hours on Day 1, then 1 mg SL-BUP every 3 hours on Day 2. On Day 3, the individual may receive 12 mg SL-BUP with 2 mg as needed. A limitation of this method is that it must be performed in an inpatient setting.4

CASE CONTINUED

To ensure patient-inclusive care, clinicians should conduct a risk-benefit discussion with the patient regarding microdosing buprenorphine. Because Mr. M would like to be managed as an outpatient, rapid microdosing is not an option. Mr. M works with his care team to design a microdosing approach with the Bernese method. They initiate buprenorphine 0.5 mg/d and increase the dose by 0.5 mg to 1 mg from Day 2 to Day 8. The variance in buprenorphine titration occurs due to Mr. M’s tolerance and symptoms of withdrawal. The team decreases the methadone dose by 5 mg to 10 mg each day, depending on symptoms of withdrawal, and discontinues therapy on Day 8. Throughout the microdosing induction, Mr. M does not experience withdrawal symptoms and is now managed on buprenorphine 12 mg/d.

Related Resources

- Van Hale C, Gluck R, Tang Y. Laboratory monitoring for patients on buprenorphine: 10 questions. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):12-15,20-21,26.

- Moreno JL, Johnson JL, Peckham AM. Sublingual buprenorphine plus buprenorphine XR for opioid use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(6):39-42,49.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Buprenorphine • Subutex, Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone, Zubsolv

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

1. Ahmed S, Bhivandkar S, Lonergan B, et al. Microinduction of buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of the literature. Am J Addict. 2021;30:305-315.

2. De Aquino JP, Fairgrieve C, Klair S, et al. Rapid transition from methadone to buprenorphine utilizing a micro-dosing protocol in the outpatient veteran affairs setting. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e271-e273.

3. Lintzeris N, Monds LA, Rivas C, et al. Transferring patients from methadone to buprenorphine: the feasibility and evaluation of practice guidelines. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):234-240.

4. Ghosh SM, Klaire S, Tanguay R, et al. A review of novel methods to support the transition from methadone and other full agonist opioids to buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual in both community and acute care settings. Can J Addict. 2019;10:41-50.

5. Haamig R, Kemter A, Strasser J, et al. Use of microdoses for induction of buprenorphine treatment with overlapping full opioid agonist use: the Bernese method. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:99-105.

6. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1095-1101.

7. Hess M, Boesch L, Leisinger R, et al. Transdermal buprenorphine to switch patients from higher dose methadone to buprenorphine without severe withdrawal symptoms. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):480‐481.

1. Ahmed S, Bhivandkar S, Lonergan B, et al. Microinduction of buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of the literature. Am J Addict. 2021;30:305-315.

2. De Aquino JP, Fairgrieve C, Klair S, et al. Rapid transition from methadone to buprenorphine utilizing a micro-dosing protocol in the outpatient veteran affairs setting. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e271-e273.

3. Lintzeris N, Monds LA, Rivas C, et al. Transferring patients from methadone to buprenorphine: the feasibility and evaluation of practice guidelines. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):234-240.

4. Ghosh SM, Klaire S, Tanguay R, et al. A review of novel methods to support the transition from methadone and other full agonist opioids to buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual in both community and acute care settings. Can J Addict. 2019;10:41-50.

5. Haamig R, Kemter A, Strasser J, et al. Use of microdoses for induction of buprenorphine treatment with overlapping full opioid agonist use: the Bernese method. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:99-105.

6. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1095-1101.

7. Hess M, Boesch L, Leisinger R, et al. Transdermal buprenorphine to switch patients from higher dose methadone to buprenorphine without severe withdrawal symptoms. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):480‐481.

Buprenorphine linked with lower risk for neonatal harms than methadone

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Your patients are rotting their teeth with vaping

Primary care physicians, and especially pediatricians, should consider telling their patients about the long-term oral health problems associated with vaping.

A new study found that patients who use vapes were at a higher risk of developing tooth decay and periodontal disease.

Vapes were introduced to the U.S. market in 2006 as an alternative to conventional cigarettes and have become widely popular among youth. According to a 2022 survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2.55 million middle and high school students in this country reported using the devices in the previous 30 days.

The new study, published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, expands on an initial case series published in 2020 of patients who reported use of vapes and who had severe dental decay. Karina Irusa, BDS, assistant professor of comprehensive care at Tufts University, Boston, and lead author of the case series, wanted to investigate whether her initial findings would apply to a large population of vape users.

For the new study, Dr. Irusa and colleagues collected data on 13,216 patients aged 16-40 who attended Tufts dental clinics between 2019 and 2021. All patients had received a diagnosis of tooth decay, had a tooth decay risk assessment on record, and had answered “yes” or “no” to use of vapes in a health history questionnaire.

Patients had records on file of varying types of dental lesions, cavities filled within the previous 3 years, heavy plaque on teeth, inadequate brushing and flushing, and a self-report of recreational drug use and frequent snacking. If patients had these factors on their file, they were at high risk of developing decay that leads to cavities.

The study found that 79% of patients who responded “yes” to being a current user of vapes were at high risk for dental decay, compared with 60% of those who did not report using the devices.

Materials in the vaping liquids further cause an inflammatory response that disrupts an individual’s internal microbiome, according to numerous studies.

“All the ingredients of vaping are surely a recipe for overgrowth of cavities causing bacteria,” said Jennifer Genuardi, MD, an internist and pediatrician at federally qualified community health center Urban Health Plan, in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Irusa said information on patient’s vaping habits should be included in routine dental and medical history questionnaires as part of their overall electronic health record.

“Decay in its severe form not only affects one’s ability to eat but affects facial aesthetics and self-esteem as well,” Dr. Irusa said.

Dr. Genuardi called the findings unsurprising.

“We are learning daily more and more about the dangers of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said. “There’s a focus of today’s research on the effect of actions on our microbiome and the subsequent effects on our health.”

Dr. Genuardi also said many of her teenage patients do not enjoy dental visits or having cavities filled, which could serve as a useful deterrent to vaping for a demographic that has been targeted with marketing from vape manufacturers.

“Cavity formation and the experience of having cavities filled is an experience teens can identify with, so this to me seems like perhaps an even more effective angle to try to curb this unhealthy behavior of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care physicians, and especially pediatricians, should consider telling their patients about the long-term oral health problems associated with vaping.

A new study found that patients who use vapes were at a higher risk of developing tooth decay and periodontal disease.

Vapes were introduced to the U.S. market in 2006 as an alternative to conventional cigarettes and have become widely popular among youth. According to a 2022 survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2.55 million middle and high school students in this country reported using the devices in the previous 30 days.

The new study, published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, expands on an initial case series published in 2020 of patients who reported use of vapes and who had severe dental decay. Karina Irusa, BDS, assistant professor of comprehensive care at Tufts University, Boston, and lead author of the case series, wanted to investigate whether her initial findings would apply to a large population of vape users.

For the new study, Dr. Irusa and colleagues collected data on 13,216 patients aged 16-40 who attended Tufts dental clinics between 2019 and 2021. All patients had received a diagnosis of tooth decay, had a tooth decay risk assessment on record, and had answered “yes” or “no” to use of vapes in a health history questionnaire.

Patients had records on file of varying types of dental lesions, cavities filled within the previous 3 years, heavy plaque on teeth, inadequate brushing and flushing, and a self-report of recreational drug use and frequent snacking. If patients had these factors on their file, they were at high risk of developing decay that leads to cavities.

The study found that 79% of patients who responded “yes” to being a current user of vapes were at high risk for dental decay, compared with 60% of those who did not report using the devices.

Materials in the vaping liquids further cause an inflammatory response that disrupts an individual’s internal microbiome, according to numerous studies.

“All the ingredients of vaping are surely a recipe for overgrowth of cavities causing bacteria,” said Jennifer Genuardi, MD, an internist and pediatrician at federally qualified community health center Urban Health Plan, in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Irusa said information on patient’s vaping habits should be included in routine dental and medical history questionnaires as part of their overall electronic health record.

“Decay in its severe form not only affects one’s ability to eat but affects facial aesthetics and self-esteem as well,” Dr. Irusa said.

Dr. Genuardi called the findings unsurprising.

“We are learning daily more and more about the dangers of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said. “There’s a focus of today’s research on the effect of actions on our microbiome and the subsequent effects on our health.”

Dr. Genuardi also said many of her teenage patients do not enjoy dental visits or having cavities filled, which could serve as a useful deterrent to vaping for a demographic that has been targeted with marketing from vape manufacturers.

“Cavity formation and the experience of having cavities filled is an experience teens can identify with, so this to me seems like perhaps an even more effective angle to try to curb this unhealthy behavior of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care physicians, and especially pediatricians, should consider telling their patients about the long-term oral health problems associated with vaping.

A new study found that patients who use vapes were at a higher risk of developing tooth decay and periodontal disease.

Vapes were introduced to the U.S. market in 2006 as an alternative to conventional cigarettes and have become widely popular among youth. According to a 2022 survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2.55 million middle and high school students in this country reported using the devices in the previous 30 days.

The new study, published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, expands on an initial case series published in 2020 of patients who reported use of vapes and who had severe dental decay. Karina Irusa, BDS, assistant professor of comprehensive care at Tufts University, Boston, and lead author of the case series, wanted to investigate whether her initial findings would apply to a large population of vape users.

For the new study, Dr. Irusa and colleagues collected data on 13,216 patients aged 16-40 who attended Tufts dental clinics between 2019 and 2021. All patients had received a diagnosis of tooth decay, had a tooth decay risk assessment on record, and had answered “yes” or “no” to use of vapes in a health history questionnaire.

Patients had records on file of varying types of dental lesions, cavities filled within the previous 3 years, heavy plaque on teeth, inadequate brushing and flushing, and a self-report of recreational drug use and frequent snacking. If patients had these factors on their file, they were at high risk of developing decay that leads to cavities.

The study found that 79% of patients who responded “yes” to being a current user of vapes were at high risk for dental decay, compared with 60% of those who did not report using the devices.

Materials in the vaping liquids further cause an inflammatory response that disrupts an individual’s internal microbiome, according to numerous studies.

“All the ingredients of vaping are surely a recipe for overgrowth of cavities causing bacteria,” said Jennifer Genuardi, MD, an internist and pediatrician at federally qualified community health center Urban Health Plan, in New York, who was not involved in the study.

Dr. Irusa said information on patient’s vaping habits should be included in routine dental and medical history questionnaires as part of their overall electronic health record.

“Decay in its severe form not only affects one’s ability to eat but affects facial aesthetics and self-esteem as well,” Dr. Irusa said.

Dr. Genuardi called the findings unsurprising.

“We are learning daily more and more about the dangers of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said. “There’s a focus of today’s research on the effect of actions on our microbiome and the subsequent effects on our health.”

Dr. Genuardi also said many of her teenage patients do not enjoy dental visits or having cavities filled, which could serve as a useful deterrent to vaping for a demographic that has been targeted with marketing from vape manufacturers.

“Cavity formation and the experience of having cavities filled is an experience teens can identify with, so this to me seems like perhaps an even more effective angle to try to curb this unhealthy behavior of vaping,” Dr. Genuardi said.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION

Highly processed foods ‘as addictive’ as tobacco

according to a new U.S. study that proposes a set of criteria to assess the addictive potential of some foods.

The research suggests that health care professionals are taking steps toward framing food addiction as a clinical entity in its own right; it currently lacks validated treatment protocols and recognition as a clinical diagnosis.

Meanwhile, other data, reported by researchers at the 2022 Diabetes Professional Care conference in London also add support to the clinical recognition of food addiction.

Clinical psychologist Jen Unwin, PhD, from Southport, England, showed that a 3-month online program of low-carbohydrate diet together with psychoeducational support significantly reduced food addiction symptoms among a varied group of individuals, not all of whom were overweight or had obesity.

Dr. Unwin said her new data represent the first wide-scale clinical audit of its kind, other than a prior report of three patients with food addiction who were successfully treated with a ketogenic diet.

“Food addiction explains so much of what we see in clinical practice, where intelligent people understand what we tell them about the physiology associated with a low-carb diet, and they follow it for a while, but then they relapse,” said Dr. Unwin, explaining the difficulties faced by around 20% of her patients who are considered to have food addiction.

Meanwhile, the authors of the U.S. study, led by Ashley N. Gearhardt, PhD, a psychologist from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that the ability of highly processed foods (HPFs) “to rapidly deliver high doses of refined carbohydrates and/or fat appear key to their addictive potential. Thus, we conclude that HPFs can be considered addictive substances based on scientifically established criteria.”

They asserted that the contribution to preventable deaths by a diet dominated by highly processed foods is comparable with that of tobacco products, and as such, like Dr. Unwin, the authors sought clinical recognition and a more formalized protocol to manage food addiction.

“Understanding whether addiction contributes to HPF intake may lead to new treatments, as preliminary research finds that behavioral and pharmacological interventions that target addictive mechanisms may reduce compulsive HPF intake,” they stated.

The study led by Dr. Gearhardt was published in the journal Addiction, and the study led by Unwin was also recently published in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

Addiction criteria similar to tobacco

HPFs can be associated with an eating phenotype “that reflects the hallmarks of addiction,” said Dr. Gearhardt and coauthors; typically, loss of control over intake, intense cravings, inability to cut down, and continued use despite negative consequences.

Acknowledging the lack of a single addictive agent, they explain that food addiction reflects mechanisms implicated in other addictive disorders such as smoking.

As such, in their study, Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues proposed a set of scientifically based criteria for the evaluation of whether certain foods are addictive. “Specifically, we propose the primary criteria used to resolve one of the last major controversies over whether a substance, tobacco products, was addictive.”

They consider certain foods according to the primary criteria that have stood the test of time after being proposed in 1988 by the U.S. Surgeon General to establish the addictive potential of tobacco: they trigger compulsive use, they have psychoactive effects, and they are reinforcing.

They have updated these criteria to include the ability to trigger urges and cravings, and added that “both these products [tobacco and HPFs] are legal, easily accessible, inexpensive, lack an intoxication syndrome, and are major causes of preventable death.”

For example, with compulsive use, tobacco meets this criterion because evidence suggests that most smokers would like to quit but are unable to do so.

Likewise, wrote Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues, even “in the face of significant diet-related health consequences (e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular disease), the majority of patients are unable to adhere to medically recommended dietary plans that require a reduction in HPF intake.”

Reinforcement, through tobacco use, is demonstrated by its ‘being sufficiently rewarding to maintain self-administration” because of its ability to deliver nicotine, they said, quoting the Surgeon General’s report, and likewise, with food addiction, “both adults and children will self-administer HPFs (e.g., potato chips, candy, and cookies) even when satiated.”

Online group food addiction intervention study

Dr. Unwin and coauthors want people with food addiction to be able to access a validated treatment protocol. Their study aimed to evaluate an online group intervention across multiple sites in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, involving an abstinent, low-carbohydrate diet and biopsychosocial education focused on addiction and recovery in people self-identifying as having food addiction.

“Lots of people with food addiction go to GPs who don’t clinically recognize this, or if they attend addiction services and psychiatry, then they tend to only specialize in drugs, alcohol, and gambling. Eating disorder services are linked but their programs mostly don’t work for a food addict,” Dr. Unwin remarked in an interview.

“We feel running groups, as well as training professionals to run groups, is the best way to manage food addiction,” she said, reflecting on the scale of the problem, with around 10% of adults in the U.K. general population considered to have food addiction. In Dr. Unwin’s study, some people had type 2 diabetes and some overweight/obesity, but she added that some participants were underweight or of normal weight.

Initially, the 103 participants received weekly group (8-24 people) sessions for 10-14 weeks, and then monthly maintenance comprising follow-up that involved coaching participants on how to cope with relapse and get back on track.

Food addiction symptoms were assessed pre- and post program using the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale (mYFAS) 2.0; ICD-10 symptoms of food-related substance use disorder (CRAVED); and mental health well-being measured using the short version of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale and body weight.

“The program eliminates processed foods with a personalized, abstinence food plan that involves education around mechanisms involved,” said Dr. Unwin, who explained that processed foods deliver a dopamine high, and in response to this, the brain lowers the number of dopamine receptors to effectively counteract the increase in dopamine. This drop in dopamine receptors explains the depression often associated with food addiction.

Dr. Unwin reported that food addiction symptoms were significantly reduced, with the mYFAS dropping by 1.52, the CRAVED score by 1.53, and body weight by 2.34 kg (5.2 lb). Mental health, as measured by the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale, improved by 2.37 points.

“We were very interested in mental health and well-being because it impacts so much across our lives, and we saw significant improvements here, but we were less interested in weight because food addicts come in all shapes and sizes with some people underweight,” said Dr. Unwin. “Food addiction symptoms were significantly improved in the group, but we now need to look at the longer-term outcomes.”

Dr. Unwin runs a low-carbohydrate program for type 2 diabetes with her husband David Unwin, MD, who is a GP in Southport, England. She said that they ask patients if they think they have food addiction, and most say they do.

“I always try to explain to patients about the dopamine high, and how this starts the craving which makes people wonder when and where they can find the next sugar hit. Just thinking about the next chocolate bar gets the dopamine running for many people, and the more they tread this path then the worse it gets because the dopamine receptors keep reducing.”

Lorraine Avery, RN, a diabetes nurse specialist for Solent NHS Trust, who attended the DPC conference, welcomed Dr. Unwin’s presentation.

“My concern as a diabetes nurse specialist is that I’m unsure all our patients recognize their food addiction, and there are often more drivers to eating than just the food in front of them,” she said in an interview. “I think there’s an emotional element, too. These people are often ‘yo-yo’ dieters, and they join lots of expert companies to help them lose weight, but these companies want them to regain and re-join their programs,” she said.

“I think there is something about helping patients recognize they have a food addiction and they need to consider that other approaches might be helpful.”

Dr. Unwin reported no relevant financial relationships; some other authors have fee-paying clients with food addiction. Dr. Gearhardt and Ms. Avery reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new U.S. study that proposes a set of criteria to assess the addictive potential of some foods.

The research suggests that health care professionals are taking steps toward framing food addiction as a clinical entity in its own right; it currently lacks validated treatment protocols and recognition as a clinical diagnosis.

Meanwhile, other data, reported by researchers at the 2022 Diabetes Professional Care conference in London also add support to the clinical recognition of food addiction.

Clinical psychologist Jen Unwin, PhD, from Southport, England, showed that a 3-month online program of low-carbohydrate diet together with psychoeducational support significantly reduced food addiction symptoms among a varied group of individuals, not all of whom were overweight or had obesity.

Dr. Unwin said her new data represent the first wide-scale clinical audit of its kind, other than a prior report of three patients with food addiction who were successfully treated with a ketogenic diet.

“Food addiction explains so much of what we see in clinical practice, where intelligent people understand what we tell them about the physiology associated with a low-carb diet, and they follow it for a while, but then they relapse,” said Dr. Unwin, explaining the difficulties faced by around 20% of her patients who are considered to have food addiction.

Meanwhile, the authors of the U.S. study, led by Ashley N. Gearhardt, PhD, a psychologist from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that the ability of highly processed foods (HPFs) “to rapidly deliver high doses of refined carbohydrates and/or fat appear key to their addictive potential. Thus, we conclude that HPFs can be considered addictive substances based on scientifically established criteria.”

They asserted that the contribution to preventable deaths by a diet dominated by highly processed foods is comparable with that of tobacco products, and as such, like Dr. Unwin, the authors sought clinical recognition and a more formalized protocol to manage food addiction.

“Understanding whether addiction contributes to HPF intake may lead to new treatments, as preliminary research finds that behavioral and pharmacological interventions that target addictive mechanisms may reduce compulsive HPF intake,” they stated.

The study led by Dr. Gearhardt was published in the journal Addiction, and the study led by Unwin was also recently published in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

Addiction criteria similar to tobacco

HPFs can be associated with an eating phenotype “that reflects the hallmarks of addiction,” said Dr. Gearhardt and coauthors; typically, loss of control over intake, intense cravings, inability to cut down, and continued use despite negative consequences.

Acknowledging the lack of a single addictive agent, they explain that food addiction reflects mechanisms implicated in other addictive disorders such as smoking.

As such, in their study, Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues proposed a set of scientifically based criteria for the evaluation of whether certain foods are addictive. “Specifically, we propose the primary criteria used to resolve one of the last major controversies over whether a substance, tobacco products, was addictive.”

They consider certain foods according to the primary criteria that have stood the test of time after being proposed in 1988 by the U.S. Surgeon General to establish the addictive potential of tobacco: they trigger compulsive use, they have psychoactive effects, and they are reinforcing.

They have updated these criteria to include the ability to trigger urges and cravings, and added that “both these products [tobacco and HPFs] are legal, easily accessible, inexpensive, lack an intoxication syndrome, and are major causes of preventable death.”

For example, with compulsive use, tobacco meets this criterion because evidence suggests that most smokers would like to quit but are unable to do so.

Likewise, wrote Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues, even “in the face of significant diet-related health consequences (e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular disease), the majority of patients are unable to adhere to medically recommended dietary plans that require a reduction in HPF intake.”

Reinforcement, through tobacco use, is demonstrated by its ‘being sufficiently rewarding to maintain self-administration” because of its ability to deliver nicotine, they said, quoting the Surgeon General’s report, and likewise, with food addiction, “both adults and children will self-administer HPFs (e.g., potato chips, candy, and cookies) even when satiated.”

Online group food addiction intervention study

Dr. Unwin and coauthors want people with food addiction to be able to access a validated treatment protocol. Their study aimed to evaluate an online group intervention across multiple sites in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, involving an abstinent, low-carbohydrate diet and biopsychosocial education focused on addiction and recovery in people self-identifying as having food addiction.

“Lots of people with food addiction go to GPs who don’t clinically recognize this, or if they attend addiction services and psychiatry, then they tend to only specialize in drugs, alcohol, and gambling. Eating disorder services are linked but their programs mostly don’t work for a food addict,” Dr. Unwin remarked in an interview.

“We feel running groups, as well as training professionals to run groups, is the best way to manage food addiction,” she said, reflecting on the scale of the problem, with around 10% of adults in the U.K. general population considered to have food addiction. In Dr. Unwin’s study, some people had type 2 diabetes and some overweight/obesity, but she added that some participants were underweight or of normal weight.

Initially, the 103 participants received weekly group (8-24 people) sessions for 10-14 weeks, and then monthly maintenance comprising follow-up that involved coaching participants on how to cope with relapse and get back on track.

Food addiction symptoms were assessed pre- and post program using the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale (mYFAS) 2.0; ICD-10 symptoms of food-related substance use disorder (CRAVED); and mental health well-being measured using the short version of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale and body weight.

“The program eliminates processed foods with a personalized, abstinence food plan that involves education around mechanisms involved,” said Dr. Unwin, who explained that processed foods deliver a dopamine high, and in response to this, the brain lowers the number of dopamine receptors to effectively counteract the increase in dopamine. This drop in dopamine receptors explains the depression often associated with food addiction.

Dr. Unwin reported that food addiction symptoms were significantly reduced, with the mYFAS dropping by 1.52, the CRAVED score by 1.53, and body weight by 2.34 kg (5.2 lb). Mental health, as measured by the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale, improved by 2.37 points.

“We were very interested in mental health and well-being because it impacts so much across our lives, and we saw significant improvements here, but we were less interested in weight because food addicts come in all shapes and sizes with some people underweight,” said Dr. Unwin. “Food addiction symptoms were significantly improved in the group, but we now need to look at the longer-term outcomes.”

Dr. Unwin runs a low-carbohydrate program for type 2 diabetes with her husband David Unwin, MD, who is a GP in Southport, England. She said that they ask patients if they think they have food addiction, and most say they do.

“I always try to explain to patients about the dopamine high, and how this starts the craving which makes people wonder when and where they can find the next sugar hit. Just thinking about the next chocolate bar gets the dopamine running for many people, and the more they tread this path then the worse it gets because the dopamine receptors keep reducing.”

Lorraine Avery, RN, a diabetes nurse specialist for Solent NHS Trust, who attended the DPC conference, welcomed Dr. Unwin’s presentation.

“My concern as a diabetes nurse specialist is that I’m unsure all our patients recognize their food addiction, and there are often more drivers to eating than just the food in front of them,” she said in an interview. “I think there’s an emotional element, too. These people are often ‘yo-yo’ dieters, and they join lots of expert companies to help them lose weight, but these companies want them to regain and re-join their programs,” she said.

“I think there is something about helping patients recognize they have a food addiction and they need to consider that other approaches might be helpful.”

Dr. Unwin reported no relevant financial relationships; some other authors have fee-paying clients with food addiction. Dr. Gearhardt and Ms. Avery reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new U.S. study that proposes a set of criteria to assess the addictive potential of some foods.

The research suggests that health care professionals are taking steps toward framing food addiction as a clinical entity in its own right; it currently lacks validated treatment protocols and recognition as a clinical diagnosis.

Meanwhile, other data, reported by researchers at the 2022 Diabetes Professional Care conference in London also add support to the clinical recognition of food addiction.

Clinical psychologist Jen Unwin, PhD, from Southport, England, showed that a 3-month online program of low-carbohydrate diet together with psychoeducational support significantly reduced food addiction symptoms among a varied group of individuals, not all of whom were overweight or had obesity.

Dr. Unwin said her new data represent the first wide-scale clinical audit of its kind, other than a prior report of three patients with food addiction who were successfully treated with a ketogenic diet.

“Food addiction explains so much of what we see in clinical practice, where intelligent people understand what we tell them about the physiology associated with a low-carb diet, and they follow it for a while, but then they relapse,” said Dr. Unwin, explaining the difficulties faced by around 20% of her patients who are considered to have food addiction.

Meanwhile, the authors of the U.S. study, led by Ashley N. Gearhardt, PhD, a psychologist from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote that the ability of highly processed foods (HPFs) “to rapidly deliver high doses of refined carbohydrates and/or fat appear key to their addictive potential. Thus, we conclude that HPFs can be considered addictive substances based on scientifically established criteria.”

They asserted that the contribution to preventable deaths by a diet dominated by highly processed foods is comparable with that of tobacco products, and as such, like Dr. Unwin, the authors sought clinical recognition and a more formalized protocol to manage food addiction.

“Understanding whether addiction contributes to HPF intake may lead to new treatments, as preliminary research finds that behavioral and pharmacological interventions that target addictive mechanisms may reduce compulsive HPF intake,” they stated.

The study led by Dr. Gearhardt was published in the journal Addiction, and the study led by Unwin was also recently published in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

Addiction criteria similar to tobacco

HPFs can be associated with an eating phenotype “that reflects the hallmarks of addiction,” said Dr. Gearhardt and coauthors; typically, loss of control over intake, intense cravings, inability to cut down, and continued use despite negative consequences.

Acknowledging the lack of a single addictive agent, they explain that food addiction reflects mechanisms implicated in other addictive disorders such as smoking.

As such, in their study, Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues proposed a set of scientifically based criteria for the evaluation of whether certain foods are addictive. “Specifically, we propose the primary criteria used to resolve one of the last major controversies over whether a substance, tobacco products, was addictive.”

They consider certain foods according to the primary criteria that have stood the test of time after being proposed in 1988 by the U.S. Surgeon General to establish the addictive potential of tobacco: they trigger compulsive use, they have psychoactive effects, and they are reinforcing.

They have updated these criteria to include the ability to trigger urges and cravings, and added that “both these products [tobacco and HPFs] are legal, easily accessible, inexpensive, lack an intoxication syndrome, and are major causes of preventable death.”

For example, with compulsive use, tobacco meets this criterion because evidence suggests that most smokers would like to quit but are unable to do so.

Likewise, wrote Dr. Gearhardt and colleagues, even “in the face of significant diet-related health consequences (e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular disease), the majority of patients are unable to adhere to medically recommended dietary plans that require a reduction in HPF intake.”

Reinforcement, through tobacco use, is demonstrated by its ‘being sufficiently rewarding to maintain self-administration” because of its ability to deliver nicotine, they said, quoting the Surgeon General’s report, and likewise, with food addiction, “both adults and children will self-administer HPFs (e.g., potato chips, candy, and cookies) even when satiated.”

Online group food addiction intervention study

Dr. Unwin and coauthors want people with food addiction to be able to access a validated treatment protocol. Their study aimed to evaluate an online group intervention across multiple sites in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, involving an abstinent, low-carbohydrate diet and biopsychosocial education focused on addiction and recovery in people self-identifying as having food addiction.

“Lots of people with food addiction go to GPs who don’t clinically recognize this, or if they attend addiction services and psychiatry, then they tend to only specialize in drugs, alcohol, and gambling. Eating disorder services are linked but their programs mostly don’t work for a food addict,” Dr. Unwin remarked in an interview.

“We feel running groups, as well as training professionals to run groups, is the best way to manage food addiction,” she said, reflecting on the scale of the problem, with around 10% of adults in the U.K. general population considered to have food addiction. In Dr. Unwin’s study, some people had type 2 diabetes and some overweight/obesity, but she added that some participants were underweight or of normal weight.

Initially, the 103 participants received weekly group (8-24 people) sessions for 10-14 weeks, and then monthly maintenance comprising follow-up that involved coaching participants on how to cope with relapse and get back on track.

Food addiction symptoms were assessed pre- and post program using the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale (mYFAS) 2.0; ICD-10 symptoms of food-related substance use disorder (CRAVED); and mental health well-being measured using the short version of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale and body weight.

“The program eliminates processed foods with a personalized, abstinence food plan that involves education around mechanisms involved,” said Dr. Unwin, who explained that processed foods deliver a dopamine high, and in response to this, the brain lowers the number of dopamine receptors to effectively counteract the increase in dopamine. This drop in dopamine receptors explains the depression often associated with food addiction.

Dr. Unwin reported that food addiction symptoms were significantly reduced, with the mYFAS dropping by 1.52, the CRAVED score by 1.53, and body weight by 2.34 kg (5.2 lb). Mental health, as measured by the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing scale, improved by 2.37 points.

“We were very interested in mental health and well-being because it impacts so much across our lives, and we saw significant improvements here, but we were less interested in weight because food addicts come in all shapes and sizes with some people underweight,” said Dr. Unwin. “Food addiction symptoms were significantly improved in the group, but we now need to look at the longer-term outcomes.”

Dr. Unwin runs a low-carbohydrate program for type 2 diabetes with her husband David Unwin, MD, who is a GP in Southport, England. She said that they ask patients if they think they have food addiction, and most say they do.

“I always try to explain to patients about the dopamine high, and how this starts the craving which makes people wonder when and where they can find the next sugar hit. Just thinking about the next chocolate bar gets the dopamine running for many people, and the more they tread this path then the worse it gets because the dopamine receptors keep reducing.”

Lorraine Avery, RN, a diabetes nurse specialist for Solent NHS Trust, who attended the DPC conference, welcomed Dr. Unwin’s presentation.

“My concern as a diabetes nurse specialist is that I’m unsure all our patients recognize their food addiction, and there are often more drivers to eating than just the food in front of them,” she said in an interview. “I think there’s an emotional element, too. These people are often ‘yo-yo’ dieters, and they join lots of expert companies to help them lose weight, but these companies want them to regain and re-join their programs,” she said.

“I think there is something about helping patients recognize they have a food addiction and they need to consider that other approaches might be helpful.”