User login

Stable, long-term opioid therapy safer than tapering?

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

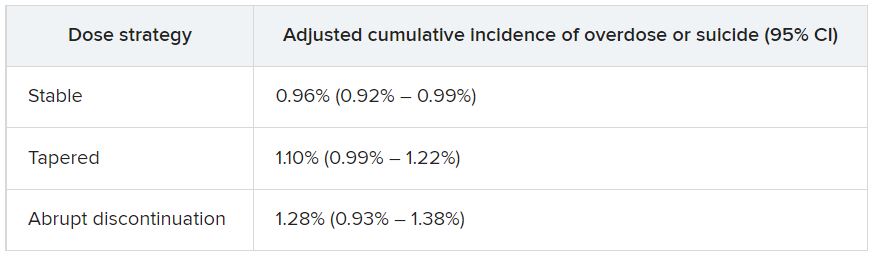

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

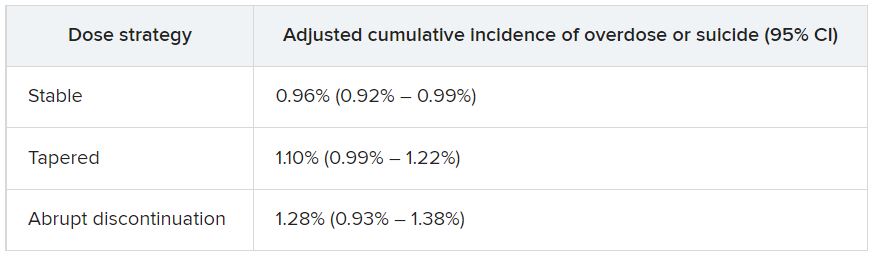

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

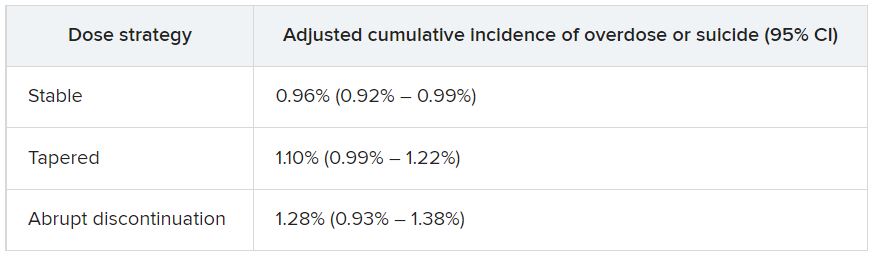

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

TikTok’s impact on adolescent mental health

For younger generations, TikTok is a go-to site for those who like short and catchy video clips. As a social media platform that allows concise video sharing, TikTok has over 1 billion monthly global users. Because of its platform size, a plethora of resources, and influence on media discourse, TikTok is the place for content creators to share visual media. Its cursory, condensed content delivery with videos capped at 1-minute focuses on high-yield information and rapid identification of fundamental points that are both engaging and entertaining.

Currently, on TikTok, 40 billion views are associated with the hashtag #mentalhealth. Content creators and regular users are employing this platform to share their own experiences, opinions, and strategies to overcome their struggles. While it is understandable for creators to share their personal stories that may be abusive, traumatic, or violent, they may not be prepared for their video to “go viral.”

Like any other social media platform, hateful speech such as racism, sexism, or xenophobia can accumulate on TikTok, which may cause more self-harm than self-help. Oversharing about personal strategies may lead to misconceived advice for TikTok viewers, while watching these TikTok videos can have negative mental health effects, even though there are no malicious intentions behind the creators who post these videos.

Hence, public health should pay more attention to the potential health-related implications this platform can create, as the quality of the information and the qualifications of the creators are mostly unrevealed. The concerns include undisclosed conflicts of interest, unchecked spread of misinformation, difficulty identifying source credibility, and excessive false information that viewers must filter through.1,2

Individual TikTok users may follow accounts and interpret these content creators as therapists and the content they see as therapy. They may also believe that a close relationship with the content creator exists when it does not. Specifically, these relationships may be defined as parasocial relationships, which are one-sided relationships where one person (the TikTok viewer) extends emotional energy, interest, and time, and the other party (the content creator) is completely unaware of the other’s existence.3 Additionally, Americans who are uninsured/underinsured may turn to this diluted version of therapy to compensate for the one-on-one or group therapy they need.

While TikTok may seem like a dangerous platform to browse through or post on, its growing influence cannot be underestimated. With 41% of TikTok users between the ages of 16 and 24, this is an ideal platform to disseminate public health information pertaining to this age group (for example, safe sex practices, substance abuse, and mental health issues).4 Because younger generations have incorporated social media into their daily lives, the medical community can harness TikTok’s potential to disseminate accurate information to potential patients for targeted medical education.

For example, Jake Goodman, MD, MBA, and Melissa Shepard, MD, each have more than a million TikTok followers and are notable psychiatrists who post a variety of content ranging from recognizing signs of depression to reducing stigma around mental health. Similarly, Justin Puder, PhD, is a licensed psychologist who advocates for ways to overcome mental health issues. By creating diverse content with appealing strategies, spreading accurate medical knowledge, and answering common medical questions for the public, these ‘mental health influencers’ educate potential patients to create patient-centered interactions.

While there are many pros and cons to social media platforms, it is undeniable that these platforms – such as TikTok – are here to stay. It is crucial for members of the medical community to recognize the outlets that younger generations use to express themselves and to exploit these media channels therapeutically.

Ms. Wong is a fourth-year medical student at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y. Dr. Chua is a psychiatrist with the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

References

1. Gottlieb M and Dyer S. Information and Disinformation: Social Media in the COVID-19 Crisis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Jul;27(7):640-1. doi: 10.1111/acem.14036.

2. De Veirman M et al. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2685. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02685.

3. Bennett N-K et al. “Parasocial Relationships: The Nature of Celebrity Fascinations.” National Register of Health Service Psychologists. https://www.findapsychologist.org/parasocial-relationships-the-nature-of-celebrity-fascinations/.

4. Eghtesadi M and Florea A. Can J Public Health. 2020 Jun;111(3):389-91. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00343-0.

For younger generations, TikTok is a go-to site for those who like short and catchy video clips. As a social media platform that allows concise video sharing, TikTok has over 1 billion monthly global users. Because of its platform size, a plethora of resources, and influence on media discourse, TikTok is the place for content creators to share visual media. Its cursory, condensed content delivery with videos capped at 1-minute focuses on high-yield information and rapid identification of fundamental points that are both engaging and entertaining.

Currently, on TikTok, 40 billion views are associated with the hashtag #mentalhealth. Content creators and regular users are employing this platform to share their own experiences, opinions, and strategies to overcome their struggles. While it is understandable for creators to share their personal stories that may be abusive, traumatic, or violent, they may not be prepared for their video to “go viral.”

Like any other social media platform, hateful speech such as racism, sexism, or xenophobia can accumulate on TikTok, which may cause more self-harm than self-help. Oversharing about personal strategies may lead to misconceived advice for TikTok viewers, while watching these TikTok videos can have negative mental health effects, even though there are no malicious intentions behind the creators who post these videos.

Hence, public health should pay more attention to the potential health-related implications this platform can create, as the quality of the information and the qualifications of the creators are mostly unrevealed. The concerns include undisclosed conflicts of interest, unchecked spread of misinformation, difficulty identifying source credibility, and excessive false information that viewers must filter through.1,2

Individual TikTok users may follow accounts and interpret these content creators as therapists and the content they see as therapy. They may also believe that a close relationship with the content creator exists when it does not. Specifically, these relationships may be defined as parasocial relationships, which are one-sided relationships where one person (the TikTok viewer) extends emotional energy, interest, and time, and the other party (the content creator) is completely unaware of the other’s existence.3 Additionally, Americans who are uninsured/underinsured may turn to this diluted version of therapy to compensate for the one-on-one or group therapy they need.

While TikTok may seem like a dangerous platform to browse through or post on, its growing influence cannot be underestimated. With 41% of TikTok users between the ages of 16 and 24, this is an ideal platform to disseminate public health information pertaining to this age group (for example, safe sex practices, substance abuse, and mental health issues).4 Because younger generations have incorporated social media into their daily lives, the medical community can harness TikTok’s potential to disseminate accurate information to potential patients for targeted medical education.

For example, Jake Goodman, MD, MBA, and Melissa Shepard, MD, each have more than a million TikTok followers and are notable psychiatrists who post a variety of content ranging from recognizing signs of depression to reducing stigma around mental health. Similarly, Justin Puder, PhD, is a licensed psychologist who advocates for ways to overcome mental health issues. By creating diverse content with appealing strategies, spreading accurate medical knowledge, and answering common medical questions for the public, these ‘mental health influencers’ educate potential patients to create patient-centered interactions.

While there are many pros and cons to social media platforms, it is undeniable that these platforms – such as TikTok – are here to stay. It is crucial for members of the medical community to recognize the outlets that younger generations use to express themselves and to exploit these media channels therapeutically.

Ms. Wong is a fourth-year medical student at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y. Dr. Chua is a psychiatrist with the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

References

1. Gottlieb M and Dyer S. Information and Disinformation: Social Media in the COVID-19 Crisis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Jul;27(7):640-1. doi: 10.1111/acem.14036.

2. De Veirman M et al. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2685. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02685.

3. Bennett N-K et al. “Parasocial Relationships: The Nature of Celebrity Fascinations.” National Register of Health Service Psychologists. https://www.findapsychologist.org/parasocial-relationships-the-nature-of-celebrity-fascinations/.

4. Eghtesadi M and Florea A. Can J Public Health. 2020 Jun;111(3):389-91. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00343-0.

For younger generations, TikTok is a go-to site for those who like short and catchy video clips. As a social media platform that allows concise video sharing, TikTok has over 1 billion monthly global users. Because of its platform size, a plethora of resources, and influence on media discourse, TikTok is the place for content creators to share visual media. Its cursory, condensed content delivery with videos capped at 1-minute focuses on high-yield information and rapid identification of fundamental points that are both engaging and entertaining.

Currently, on TikTok, 40 billion views are associated with the hashtag #mentalhealth. Content creators and regular users are employing this platform to share their own experiences, opinions, and strategies to overcome their struggles. While it is understandable for creators to share their personal stories that may be abusive, traumatic, or violent, they may not be prepared for their video to “go viral.”

Like any other social media platform, hateful speech such as racism, sexism, or xenophobia can accumulate on TikTok, which may cause more self-harm than self-help. Oversharing about personal strategies may lead to misconceived advice for TikTok viewers, while watching these TikTok videos can have negative mental health effects, even though there are no malicious intentions behind the creators who post these videos.

Hence, public health should pay more attention to the potential health-related implications this platform can create, as the quality of the information and the qualifications of the creators are mostly unrevealed. The concerns include undisclosed conflicts of interest, unchecked spread of misinformation, difficulty identifying source credibility, and excessive false information that viewers must filter through.1,2

Individual TikTok users may follow accounts and interpret these content creators as therapists and the content they see as therapy. They may also believe that a close relationship with the content creator exists when it does not. Specifically, these relationships may be defined as parasocial relationships, which are one-sided relationships where one person (the TikTok viewer) extends emotional energy, interest, and time, and the other party (the content creator) is completely unaware of the other’s existence.3 Additionally, Americans who are uninsured/underinsured may turn to this diluted version of therapy to compensate for the one-on-one or group therapy they need.

While TikTok may seem like a dangerous platform to browse through or post on, its growing influence cannot be underestimated. With 41% of TikTok users between the ages of 16 and 24, this is an ideal platform to disseminate public health information pertaining to this age group (for example, safe sex practices, substance abuse, and mental health issues).4 Because younger generations have incorporated social media into their daily lives, the medical community can harness TikTok’s potential to disseminate accurate information to potential patients for targeted medical education.

For example, Jake Goodman, MD, MBA, and Melissa Shepard, MD, each have more than a million TikTok followers and are notable psychiatrists who post a variety of content ranging from recognizing signs of depression to reducing stigma around mental health. Similarly, Justin Puder, PhD, is a licensed psychologist who advocates for ways to overcome mental health issues. By creating diverse content with appealing strategies, spreading accurate medical knowledge, and answering common medical questions for the public, these ‘mental health influencers’ educate potential patients to create patient-centered interactions.

While there are many pros and cons to social media platforms, it is undeniable that these platforms – such as TikTok – are here to stay. It is crucial for members of the medical community to recognize the outlets that younger generations use to express themselves and to exploit these media channels therapeutically.

Ms. Wong is a fourth-year medical student at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y. Dr. Chua is a psychiatrist with the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

References

1. Gottlieb M and Dyer S. Information and Disinformation: Social Media in the COVID-19 Crisis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020 Jul;27(7):640-1. doi: 10.1111/acem.14036.

2. De Veirman M et al. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2685. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02685.

3. Bennett N-K et al. “Parasocial Relationships: The Nature of Celebrity Fascinations.” National Register of Health Service Psychologists. https://www.findapsychologist.org/parasocial-relationships-the-nature-of-celebrity-fascinations/.

4. Eghtesadi M and Florea A. Can J Public Health. 2020 Jun;111(3):389-91. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00343-0.

Psychedelic drug therapy a potential ‘breakthrough’ for alcohol dependence

Results from the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of psilocybin for alcohol dependence showed that during the 8 months after first treatment dose, participants who received psilocybin had less than half as many heavy drinking days as their counterparts who received placebo.

In addition, 7 months after the last dose of medication, twice as many psilocybin-treated patients as placebo-treated patients were abstinent.

The effects observed with psilocybin were “considerably larger” than those of currently approved treatments for AUD, senior investigator Michael Bogenschutz, MD, psychiatrist and director of the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine, New York, said during an Aug. 24 press briefing.

If the findings hold up in future trials, psilocybin will be a “real breakthrough” in the treatment of the condition, Dr. Bogenschutz said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

83% reduction in drinking days

The study included 93 adults (mean age, 46 years) with alcohol dependence who consumed an average of seven drinks on the days they drank and had had at least four heavy drinking days during the month prior to treatment.

Of the participants, 48 were randomly assigned to receive two doses of psilocybin, and 45 were assigned to receive an antihistamine (diphenhydramine) placebo. Study medication was administered during 2 day-long sessions at week 4 and week 8.

The participants also received 12 psychotherapy sessions over a 12-week period. All were assessed at intervals from the beginning of the study until 32 weeks after the first medication session.

The primary outcome was percentage of days in which the patient drank heavily during the 32-week period following first medication dose. Heavy drinking was defined as having five or more drinks in a day for a man and four or more drinks in a day for a woman.

The percentage of heavy drinking days during the 32-week period was 9.7% for the psilocybin group and 23.6% for the placebo group, for a mean difference of 13.9% (P = .01).

“Compared to their baseline before the study, after receiving medication, the psilocybin group decreased their heavy drinking days by 83%, while the placebo group reduced their heavy drinking by 51%,” Dr. Bogenschutz reported.

During the last month of follow-up, which was 7 months after the final dose of study medication, 48% of the psilocybin group were entirely abstinent vs. 24% of the placebo group.

“It is remarkable that the effects of psilocybin treatment persisted for 7 months after people received the last dose of medication. This suggests that psilocybin is treating the underlying disorder of alcohol addiction rather than merely treating symptoms,” Dr. Bogenschutz noted.

Total alcohol consumption and problems related to alcohol use were also significantly less in the psilocybin group.

‘Encouraged and hopeful’

Adverse events related to psilocybin were mostly mild, self-limiting, and consistent with other recent trials that evaluated the drug’s effects in various conditions.

However, the current investigators note that they implemented measures to ensure safety, including careful medical and psychiatric screening, therapy, and monitoring that was provided by well-trained therapists, including a licensed psychiatrist. In addition, medications were available to treat acute psychiatric reactions.

A cited limitation of the study was that blinding was not maintained because the average intensity of experience with psilocybin was high, whereas it was low with diphenhydramine.

This difference undermined the masking of treatment such that more than 90% of participants and therapists correctly guessed the treatment assignment.

Another limitation was that objective measures to validate self-reported drinking outcomes were available for only 54% of study participants.

Despite these limitations, the study builds on earlier work by the NYU team that showed that two doses of psilocybin taken over a period of 8 weeks significantly reduced alcohol use and cravings in patients with AUD.

“We’re very encouraged by these findings and hopeful about where they could lead. Personally, it’s been very meaningful and rewarding for me to do this work and inspiring to witness the remarkable recoveries that some of our participants have experienced,” Dr. Bogenschutz told briefing attendees.

Urgent need

The authors of an accompanying editorial note that novel medications for alcohol dependence are “sorely needed. Recent renewed interest in the potential of hallucinogens for treating psychiatric disorders, including AUD, represents a potential move in that direction.”

Henry Kranzler, MD, and Emily Hartwell, PhD, both with the Center for Studies of Addiction, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, write that the new findings “underscore the potential of developing psilocybin as an addition to the alcohol treatment pharmacopeia.”

They question, however, the feasibility of using hallucinogens in routine clinical practice because intensive psychotherapy, such as that provided in this study, requires a significant investment of time and labor.

“Such concomitant therapy, if necessary to realize the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin for treating AUD, could limit its uptake by clinicians,” Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell write.

The study was funded by the Heffter Research Institute and by individual donations from Carey and Claudia Turnbull, Dr. Efrem Nulman, Rodrigo Niño, and Cody Swift. Dr. Bogenschutz reports having received research funds from and serving as a consultant to Mind Medicine, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, B. More, AJNA Labs, Beckley Psytech, Journey Colab, and Bright Minds Biosciences. Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of psilocybin for alcohol dependence showed that during the 8 months after first treatment dose, participants who received psilocybin had less than half as many heavy drinking days as their counterparts who received placebo.

In addition, 7 months after the last dose of medication, twice as many psilocybin-treated patients as placebo-treated patients were abstinent.

The effects observed with psilocybin were “considerably larger” than those of currently approved treatments for AUD, senior investigator Michael Bogenschutz, MD, psychiatrist and director of the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine, New York, said during an Aug. 24 press briefing.

If the findings hold up in future trials, psilocybin will be a “real breakthrough” in the treatment of the condition, Dr. Bogenschutz said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

83% reduction in drinking days

The study included 93 adults (mean age, 46 years) with alcohol dependence who consumed an average of seven drinks on the days they drank and had had at least four heavy drinking days during the month prior to treatment.

Of the participants, 48 were randomly assigned to receive two doses of psilocybin, and 45 were assigned to receive an antihistamine (diphenhydramine) placebo. Study medication was administered during 2 day-long sessions at week 4 and week 8.

The participants also received 12 psychotherapy sessions over a 12-week period. All were assessed at intervals from the beginning of the study until 32 weeks after the first medication session.

The primary outcome was percentage of days in which the patient drank heavily during the 32-week period following first medication dose. Heavy drinking was defined as having five or more drinks in a day for a man and four or more drinks in a day for a woman.

The percentage of heavy drinking days during the 32-week period was 9.7% for the psilocybin group and 23.6% for the placebo group, for a mean difference of 13.9% (P = .01).

“Compared to their baseline before the study, after receiving medication, the psilocybin group decreased their heavy drinking days by 83%, while the placebo group reduced their heavy drinking by 51%,” Dr. Bogenschutz reported.

During the last month of follow-up, which was 7 months after the final dose of study medication, 48% of the psilocybin group were entirely abstinent vs. 24% of the placebo group.

“It is remarkable that the effects of psilocybin treatment persisted for 7 months after people received the last dose of medication. This suggests that psilocybin is treating the underlying disorder of alcohol addiction rather than merely treating symptoms,” Dr. Bogenschutz noted.

Total alcohol consumption and problems related to alcohol use were also significantly less in the psilocybin group.

‘Encouraged and hopeful’

Adverse events related to psilocybin were mostly mild, self-limiting, and consistent with other recent trials that evaluated the drug’s effects in various conditions.

However, the current investigators note that they implemented measures to ensure safety, including careful medical and psychiatric screening, therapy, and monitoring that was provided by well-trained therapists, including a licensed psychiatrist. In addition, medications were available to treat acute psychiatric reactions.

A cited limitation of the study was that blinding was not maintained because the average intensity of experience with psilocybin was high, whereas it was low with diphenhydramine.

This difference undermined the masking of treatment such that more than 90% of participants and therapists correctly guessed the treatment assignment.

Another limitation was that objective measures to validate self-reported drinking outcomes were available for only 54% of study participants.

Despite these limitations, the study builds on earlier work by the NYU team that showed that two doses of psilocybin taken over a period of 8 weeks significantly reduced alcohol use and cravings in patients with AUD.

“We’re very encouraged by these findings and hopeful about where they could lead. Personally, it’s been very meaningful and rewarding for me to do this work and inspiring to witness the remarkable recoveries that some of our participants have experienced,” Dr. Bogenschutz told briefing attendees.

Urgent need

The authors of an accompanying editorial note that novel medications for alcohol dependence are “sorely needed. Recent renewed interest in the potential of hallucinogens for treating psychiatric disorders, including AUD, represents a potential move in that direction.”

Henry Kranzler, MD, and Emily Hartwell, PhD, both with the Center for Studies of Addiction, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, write that the new findings “underscore the potential of developing psilocybin as an addition to the alcohol treatment pharmacopeia.”

They question, however, the feasibility of using hallucinogens in routine clinical practice because intensive psychotherapy, such as that provided in this study, requires a significant investment of time and labor.

“Such concomitant therapy, if necessary to realize the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin for treating AUD, could limit its uptake by clinicians,” Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell write.

The study was funded by the Heffter Research Institute and by individual donations from Carey and Claudia Turnbull, Dr. Efrem Nulman, Rodrigo Niño, and Cody Swift. Dr. Bogenschutz reports having received research funds from and serving as a consultant to Mind Medicine, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, B. More, AJNA Labs, Beckley Psytech, Journey Colab, and Bright Minds Biosciences. Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial of psilocybin for alcohol dependence showed that during the 8 months after first treatment dose, participants who received psilocybin had less than half as many heavy drinking days as their counterparts who received placebo.

In addition, 7 months after the last dose of medication, twice as many psilocybin-treated patients as placebo-treated patients were abstinent.

The effects observed with psilocybin were “considerably larger” than those of currently approved treatments for AUD, senior investigator Michael Bogenschutz, MD, psychiatrist and director of the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine, New York, said during an Aug. 24 press briefing.

If the findings hold up in future trials, psilocybin will be a “real breakthrough” in the treatment of the condition, Dr. Bogenschutz said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

83% reduction in drinking days

The study included 93 adults (mean age, 46 years) with alcohol dependence who consumed an average of seven drinks on the days they drank and had had at least four heavy drinking days during the month prior to treatment.

Of the participants, 48 were randomly assigned to receive two doses of psilocybin, and 45 were assigned to receive an antihistamine (diphenhydramine) placebo. Study medication was administered during 2 day-long sessions at week 4 and week 8.

The participants also received 12 psychotherapy sessions over a 12-week period. All were assessed at intervals from the beginning of the study until 32 weeks after the first medication session.

The primary outcome was percentage of days in which the patient drank heavily during the 32-week period following first medication dose. Heavy drinking was defined as having five or more drinks in a day for a man and four or more drinks in a day for a woman.

The percentage of heavy drinking days during the 32-week period was 9.7% for the psilocybin group and 23.6% for the placebo group, for a mean difference of 13.9% (P = .01).

“Compared to their baseline before the study, after receiving medication, the psilocybin group decreased their heavy drinking days by 83%, while the placebo group reduced their heavy drinking by 51%,” Dr. Bogenschutz reported.

During the last month of follow-up, which was 7 months after the final dose of study medication, 48% of the psilocybin group were entirely abstinent vs. 24% of the placebo group.

“It is remarkable that the effects of psilocybin treatment persisted for 7 months after people received the last dose of medication. This suggests that psilocybin is treating the underlying disorder of alcohol addiction rather than merely treating symptoms,” Dr. Bogenschutz noted.

Total alcohol consumption and problems related to alcohol use were also significantly less in the psilocybin group.

‘Encouraged and hopeful’

Adverse events related to psilocybin were mostly mild, self-limiting, and consistent with other recent trials that evaluated the drug’s effects in various conditions.

However, the current investigators note that they implemented measures to ensure safety, including careful medical and psychiatric screening, therapy, and monitoring that was provided by well-trained therapists, including a licensed psychiatrist. In addition, medications were available to treat acute psychiatric reactions.

A cited limitation of the study was that blinding was not maintained because the average intensity of experience with psilocybin was high, whereas it was low with diphenhydramine.

This difference undermined the masking of treatment such that more than 90% of participants and therapists correctly guessed the treatment assignment.

Another limitation was that objective measures to validate self-reported drinking outcomes were available for only 54% of study participants.

Despite these limitations, the study builds on earlier work by the NYU team that showed that two doses of psilocybin taken over a period of 8 weeks significantly reduced alcohol use and cravings in patients with AUD.

“We’re very encouraged by these findings and hopeful about where they could lead. Personally, it’s been very meaningful and rewarding for me to do this work and inspiring to witness the remarkable recoveries that some of our participants have experienced,” Dr. Bogenschutz told briefing attendees.

Urgent need

The authors of an accompanying editorial note that novel medications for alcohol dependence are “sorely needed. Recent renewed interest in the potential of hallucinogens for treating psychiatric disorders, including AUD, represents a potential move in that direction.”

Henry Kranzler, MD, and Emily Hartwell, PhD, both with the Center for Studies of Addiction, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, write that the new findings “underscore the potential of developing psilocybin as an addition to the alcohol treatment pharmacopeia.”

They question, however, the feasibility of using hallucinogens in routine clinical practice because intensive psychotherapy, such as that provided in this study, requires a significant investment of time and labor.

“Such concomitant therapy, if necessary to realize the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin for treating AUD, could limit its uptake by clinicians,” Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell write.

The study was funded by the Heffter Research Institute and by individual donations from Carey and Claudia Turnbull, Dr. Efrem Nulman, Rodrigo Niño, and Cody Swift. Dr. Bogenschutz reports having received research funds from and serving as a consultant to Mind Medicine, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, B. More, AJNA Labs, Beckley Psytech, Journey Colab, and Bright Minds Biosciences. Dr. Kranzler and Dr. Hartwell have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Reducing alcohol intake may reduce cancer risk

Alcohol is a major preventable risk factor for cancer. New data suggest that reducing alcohol intake reduces the risk of developing an alcohol-related cancer.

The findings, from a large population-based study conducted in Korea, underscore the importance of encouraging individuals to quit drinking or to reduce alcohol consumption to help reduce cancer risk, the authors noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

It provides evidence “suggesting that cancer risk can be meaningfully altered by changing the amount of alcoholic beverages consumed,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Neal D. Freedman, PhD, and Christian C. Abnet, PhD, of the division of cancer epidemiology and genetics at the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Md.

they wrote, adding that a “well examined dose-response association has been reported, with highest risks observed among people who drink 3 alcoholic beverages per day and higher.”

The new study shows that a “reduction in use was associated with lower risk, particularly among participants who started drinking at a heavy level,” they noted.

Previous studies have estimated that alcohol use accounts for nearly 4% of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide and nearly 5% of U.S. cancer cases overall.

But the figures are much higher for some specific cancers. That same U.S. study found that alcohol accounts for at least 45% of oral cavity/pharyngeal cancers and at least 25% of laryngeal cancers, as well as 12.1% of female breast cancers, 11.1% of colorectal cancers, 10.5% of liver cancers, and 7.7% of esophageal cancers, as previously reported by this news organization.

New findings on reducing intake

This latest study involved an analysis of data on 4.5 million individuals who were adult beneficiaries of the Korean National Health Insurance Service. The median age of the participants was 53.6 years, and they underwent a national health screening in 2009 and 2011.

During median follow-up of 6.4 years, the cancer incidence rate was 7.7 per 1,000 person-years.

Information on alcohol consumption was collected from self-administered questionnaires completed during the health screenings. Participants were categorized on the basis of alcohol consumption: none (0 g/d), mild ( less than 15 g/d), moderate (15-29.9 g/d), and heavy (30 or more g/d).

Compared with those who sustained their alcohol consumption level during the study period, those who increased their level were at higher risk of alcohol-related cancers and all cancers, the investigators found.

The increase in alcohol-related cancer incidence was dose dependent: Those who changed from nondrinking to mild, moderate, or heavy drinking were at increasingly higher risk for alcohol-related cancer, compared with those who remained nondrinkers (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs], 1.03, 1.10, and 1.34, respectively).

Participants who were mild drinkers at baseline and who quit drinking were at lower risk of alcohol-related cancer, compared with those whose drinking level was sustained (aHR, 0.96). Those with moderate or heavy drinking levels who quit drinking were at higher overall cancer risk than were those who sustained their drinking levels. However, this difference was negated when quitting was sustained, the authors noted.

For heavy drinkers who reduced their drinking levels, cancer incidence was reduced, compared with those who sustained heavy drinking levels. This was true for those who changed from heavy to moderate drinking (aHR, 0.91 for alcohol-related cancers; 0.96 for alcohol-related cancers) and those who changed from heavy to mild drinking (aHR, 0.92 for alcohol-related cancers and all cancers).

“Alcohol cessation and reduction should be reinforced for the prevention of cancer,” concluded the authors.

Implications and future directions

The editorialists noted that the study is limited by several factors, such as a short interval between assessments and relatively short follow-up. There is also no information on participants’ alcohol consumption earlier in life or about other healthy lifestyle changes during the study period. In addition, there is no mention of a genetic variant affecting aldehyde dehydrogenase that leads to alcohol-induced flushing, which is common among East Asians.

Despite of these limitations, the study provides “important new findings about the potential role of changes in alcohol consumption in cancer risk,” Dr. Freedman and Dr. Abnet noted. Future studies should examine the association between alcohol intake and cancer risk in other populations and use longer intervals between assessments, they suggested.

“Such studies are needed to move the field forward and inform public health guidance on cancer prevention,” the editorialists concluded.

The authors of the study and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alcohol is a major preventable risk factor for cancer. New data suggest that reducing alcohol intake reduces the risk of developing an alcohol-related cancer.

The findings, from a large population-based study conducted in Korea, underscore the importance of encouraging individuals to quit drinking or to reduce alcohol consumption to help reduce cancer risk, the authors noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

It provides evidence “suggesting that cancer risk can be meaningfully altered by changing the amount of alcoholic beverages consumed,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Neal D. Freedman, PhD, and Christian C. Abnet, PhD, of the division of cancer epidemiology and genetics at the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Md.

they wrote, adding that a “well examined dose-response association has been reported, with highest risks observed among people who drink 3 alcoholic beverages per day and higher.”

The new study shows that a “reduction in use was associated with lower risk, particularly among participants who started drinking at a heavy level,” they noted.

Previous studies have estimated that alcohol use accounts for nearly 4% of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide and nearly 5% of U.S. cancer cases overall.

But the figures are much higher for some specific cancers. That same U.S. study found that alcohol accounts for at least 45% of oral cavity/pharyngeal cancers and at least 25% of laryngeal cancers, as well as 12.1% of female breast cancers, 11.1% of colorectal cancers, 10.5% of liver cancers, and 7.7% of esophageal cancers, as previously reported by this news organization.

New findings on reducing intake

This latest study involved an analysis of data on 4.5 million individuals who were adult beneficiaries of the Korean National Health Insurance Service. The median age of the participants was 53.6 years, and they underwent a national health screening in 2009 and 2011.

During median follow-up of 6.4 years, the cancer incidence rate was 7.7 per 1,000 person-years.

Information on alcohol consumption was collected from self-administered questionnaires completed during the health screenings. Participants were categorized on the basis of alcohol consumption: none (0 g/d), mild ( less than 15 g/d), moderate (15-29.9 g/d), and heavy (30 or more g/d).

Compared with those who sustained their alcohol consumption level during the study period, those who increased their level were at higher risk of alcohol-related cancers and all cancers, the investigators found.

The increase in alcohol-related cancer incidence was dose dependent: Those who changed from nondrinking to mild, moderate, or heavy drinking were at increasingly higher risk for alcohol-related cancer, compared with those who remained nondrinkers (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs], 1.03, 1.10, and 1.34, respectively).

Participants who were mild drinkers at baseline and who quit drinking were at lower risk of alcohol-related cancer, compared with those whose drinking level was sustained (aHR, 0.96). Those with moderate or heavy drinking levels who quit drinking were at higher overall cancer risk than were those who sustained their drinking levels. However, this difference was negated when quitting was sustained, the authors noted.

For heavy drinkers who reduced their drinking levels, cancer incidence was reduced, compared with those who sustained heavy drinking levels. This was true for those who changed from heavy to moderate drinking (aHR, 0.91 for alcohol-related cancers; 0.96 for alcohol-related cancers) and those who changed from heavy to mild drinking (aHR, 0.92 for alcohol-related cancers and all cancers).

“Alcohol cessation and reduction should be reinforced for the prevention of cancer,” concluded the authors.

Implications and future directions

The editorialists noted that the study is limited by several factors, such as a short interval between assessments and relatively short follow-up. There is also no information on participants’ alcohol consumption earlier in life or about other healthy lifestyle changes during the study period. In addition, there is no mention of a genetic variant affecting aldehyde dehydrogenase that leads to alcohol-induced flushing, which is common among East Asians.

Despite of these limitations, the study provides “important new findings about the potential role of changes in alcohol consumption in cancer risk,” Dr. Freedman and Dr. Abnet noted. Future studies should examine the association between alcohol intake and cancer risk in other populations and use longer intervals between assessments, they suggested.

“Such studies are needed to move the field forward and inform public health guidance on cancer prevention,” the editorialists concluded.

The authors of the study and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alcohol is a major preventable risk factor for cancer. New data suggest that reducing alcohol intake reduces the risk of developing an alcohol-related cancer.

The findings, from a large population-based study conducted in Korea, underscore the importance of encouraging individuals to quit drinking or to reduce alcohol consumption to help reduce cancer risk, the authors noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

It provides evidence “suggesting that cancer risk can be meaningfully altered by changing the amount of alcoholic beverages consumed,” wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial, Neal D. Freedman, PhD, and Christian C. Abnet, PhD, of the division of cancer epidemiology and genetics at the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Md.

they wrote, adding that a “well examined dose-response association has been reported, with highest risks observed among people who drink 3 alcoholic beverages per day and higher.”

The new study shows that a “reduction in use was associated with lower risk, particularly among participants who started drinking at a heavy level,” they noted.

Previous studies have estimated that alcohol use accounts for nearly 4% of newly diagnosed cancers worldwide and nearly 5% of U.S. cancer cases overall.

But the figures are much higher for some specific cancers. That same U.S. study found that alcohol accounts for at least 45% of oral cavity/pharyngeal cancers and at least 25% of laryngeal cancers, as well as 12.1% of female breast cancers, 11.1% of colorectal cancers, 10.5% of liver cancers, and 7.7% of esophageal cancers, as previously reported by this news organization.

New findings on reducing intake

This latest study involved an analysis of data on 4.5 million individuals who were adult beneficiaries of the Korean National Health Insurance Service. The median age of the participants was 53.6 years, and they underwent a national health screening in 2009 and 2011.

During median follow-up of 6.4 years, the cancer incidence rate was 7.7 per 1,000 person-years.

Information on alcohol consumption was collected from self-administered questionnaires completed during the health screenings. Participants were categorized on the basis of alcohol consumption: none (0 g/d), mild ( less than 15 g/d), moderate (15-29.9 g/d), and heavy (30 or more g/d).

Compared with those who sustained their alcohol consumption level during the study period, those who increased their level were at higher risk of alcohol-related cancers and all cancers, the investigators found.

The increase in alcohol-related cancer incidence was dose dependent: Those who changed from nondrinking to mild, moderate, or heavy drinking were at increasingly higher risk for alcohol-related cancer, compared with those who remained nondrinkers (adjusted hazard ratios [aHRs], 1.03, 1.10, and 1.34, respectively).

Participants who were mild drinkers at baseline and who quit drinking were at lower risk of alcohol-related cancer, compared with those whose drinking level was sustained (aHR, 0.96). Those with moderate or heavy drinking levels who quit drinking were at higher overall cancer risk than were those who sustained their drinking levels. However, this difference was negated when quitting was sustained, the authors noted.

For heavy drinkers who reduced their drinking levels, cancer incidence was reduced, compared with those who sustained heavy drinking levels. This was true for those who changed from heavy to moderate drinking (aHR, 0.91 for alcohol-related cancers; 0.96 for alcohol-related cancers) and those who changed from heavy to mild drinking (aHR, 0.92 for alcohol-related cancers and all cancers).

“Alcohol cessation and reduction should be reinforced for the prevention of cancer,” concluded the authors.

Implications and future directions

The editorialists noted that the study is limited by several factors, such as a short interval between assessments and relatively short follow-up. There is also no information on participants’ alcohol consumption earlier in life or about other healthy lifestyle changes during the study period. In addition, there is no mention of a genetic variant affecting aldehyde dehydrogenase that leads to alcohol-induced flushing, which is common among East Asians.

Despite of these limitations, the study provides “important new findings about the potential role of changes in alcohol consumption in cancer risk,” Dr. Freedman and Dr. Abnet noted. Future studies should examine the association between alcohol intake and cancer risk in other populations and use longer intervals between assessments, they suggested.

“Such studies are needed to move the field forward and inform public health guidance on cancer prevention,” the editorialists concluded.

The authors of the study and the editorialists have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale succeeds as transdiagnostic measure

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).

Overall, the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP showed moderate correlation and good agreement, the researchers said. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP scales was 0.53 and the concordance correlation coefficient was 0.52. The mean sum scores for the BPRS, the mini-ICF-APP, and the CGI were 45.4 (standard deviation, 14.4), 19.93 (SD, 8.21), and 5.55 (SD, 0.84), respectively, which indicated “markedly ill” to “severely ill” patients, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to detect three clusters of symptoms corresponding to externalizing, internalizing, and thought disturbance domains using the BPRS, and four clusters using the mini-ICF-APP.

The symptoms using BPRS and the functionality domains using the mini-ICF-APP “showed a close interplay,” the researchers noted.

“The symptoms and functional domains we found to be central within the network structure are among the first targets of any psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, namely the building of a common language and understanding as well as the establishment of confidence in relationships and a trustworthy therapeutic alliance,” they wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the collection of data from routine practice rather than clinical trials, the focus on only the main diagnosis without comorbidities, and the inclusion only of patients requiring hospitalization, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and demonstrate the validity of the BPRS as a measurement tool across a range of psychiatric diagnoses, they said.

“Since the BPRS is a widely known and readily available psychometric scale, our results support its use as a transdiagnostic measurement instrument of psychopathology,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).

Overall, the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP showed moderate correlation and good agreement, the researchers said. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP scales was 0.53 and the concordance correlation coefficient was 0.52. The mean sum scores for the BPRS, the mini-ICF-APP, and the CGI were 45.4 (standard deviation, 14.4), 19.93 (SD, 8.21), and 5.55 (SD, 0.84), respectively, which indicated “markedly ill” to “severely ill” patients, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to detect three clusters of symptoms corresponding to externalizing, internalizing, and thought disturbance domains using the BPRS, and four clusters using the mini-ICF-APP.

The symptoms using BPRS and the functionality domains using the mini-ICF-APP “showed a close interplay,” the researchers noted.

“The symptoms and functional domains we found to be central within the network structure are among the first targets of any psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, namely the building of a common language and understanding as well as the establishment of confidence in relationships and a trustworthy therapeutic alliance,” they wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the collection of data from routine practice rather than clinical trials, the focus on only the main diagnosis without comorbidities, and the inclusion only of patients requiring hospitalization, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and demonstrate the validity of the BPRS as a measurement tool across a range of psychiatric diagnoses, they said.

“Since the BPRS is a widely known and readily available psychometric scale, our results support its use as a transdiagnostic measurement instrument of psychopathology,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).