User login

50.6 million tobacco users are not a homogeneous group

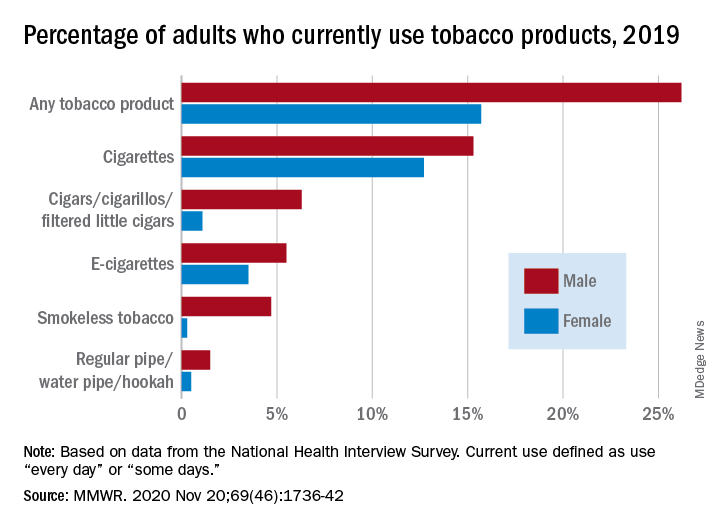

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

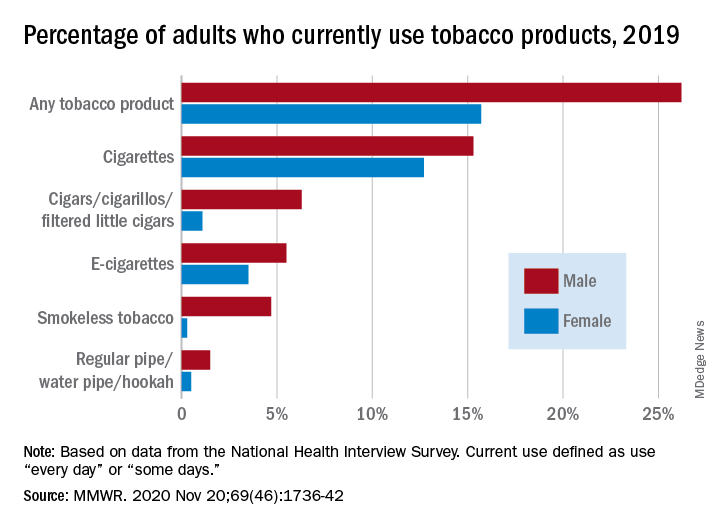

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

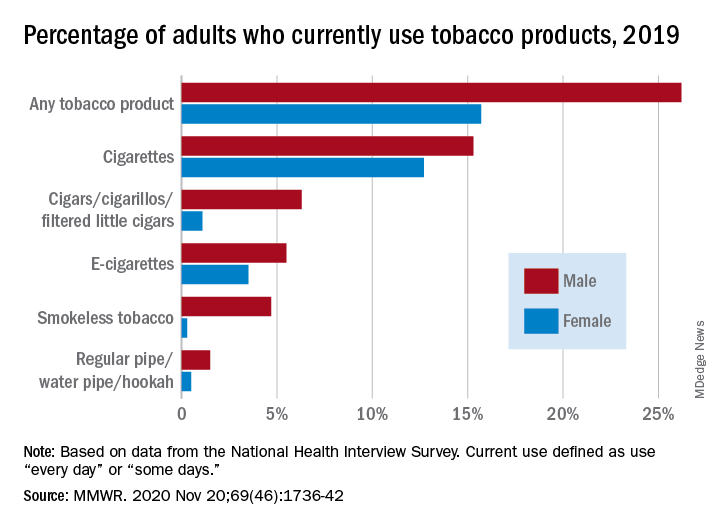

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

FROM MMWR

Can mental health teams de-escalate crises in NYC?

“Defund the police”: It’s a slogan, or perhaps a battle cry, that has emerged from the Black Lives Matter movement as a response to race-related police brutality and concerns that people of color are profiled, targeted, arrested, charged, manhandled, and killed by law enforcement in a disproportionate and unjust manner. It crosses into our realm as psychiatrists as mental health emergency calls are handled by the police and not by mental health professionals. The result is sometimes tragic: As many as half of police shootings involve people with psychiatric disorders, and the hope is that many of the police shootings could be avoided if crises were handed by mental health clinicians instead of, or in cooperation with, the police.

At best, police officers receive a week of specialized, crisis intervention training about how to approach those with psychiatric disorders; most officers receive no training. This leaves psychiatry as the only field where medical crises are routinely handled by the police – it is demeaning and embarrassing for some of our patients and dangerous for others. The reality remains, however, that there are times when psychiatric disorders result in violent behavior, and patients being taken for involuntary treatment often resist transport, so either way there is risk, both to the patient and to anyone who responds to a call for assistance.

Early this month, the office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that a major change would be made in how mental health calls to 911 are handled in two “high-need” areas. The mayor’s website states:

“Beginning in February 2021, new Mental Health Teams will use their physical and mental health expertise, and experience in crisis response to de-escalate emergency situations, will help reduce the number of times police will need to respond to 911 mental health calls in these precincts. These teams will have the expertise to respond to a range of behavioral health problems, such as suicide attempts, substance misuse, and serious mental illness, as well as physical health problems, which can be exacerbated by or mask mental health problems. NYC Health + Hospitals will train and provide ongoing technical assistance and support. In selecting team members for this program, FDNY will prioritize professionals with significant experience with mental health crises.”

The press release goes on to say that, in situations where there is a weapon or reason to believe there is a risk of violence, the police will be dispatched along with the new mental health team.

“This is the first time in our history that health professionals will be the default responders to mental health emergencies,” New York City First Lady Chirlane McCray said as she announced the new program. “Treating mental health crises as mental health challenges and not public safety ones is the modern and more appropriate approach.”

New York City is not the first city to employ this model. In the United States, the CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) program in Eugene, Ore., has been run by the White Bird Clinic since 1989 as part of a community policing initiative. Last year, the team responded to 24,000 calls and police backup was required on only 150 of those responses. The CAHOOTS website states:

“The CAHOOTS model has been in the spotlight recently as our nation struggles to reimagine public safety. The program mobilizes two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The CAHOOTS teams deal with a wide range of mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, welfare checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more, relying on trauma-informed de-escalation and harm reduction techniques. CAHOOTS staff are not law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons; their training and experience are the tools they use to ensure a non-violent resolution of crisis situations. They also handle non-emergent medical issues, avoiding costly ambulance transport and emergency room treatment.”

Other cities in the United States are also looking at implementing programs where mental health teams, and not the police, respond to emergency calls. Last year, Oakland, Calif.’s city council invested $40,000 in research to assess how they could best implement a program like the one in Eugene. They hope to begin the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACROS) next year. Sigal Samuel writes in a Vox article, “The goal is to launch the pilot next year with funding from the city budget, and although supporters are not yet sure what its size and duration will be, they’re hopeful it’ll make a big difference to Oakland’s overpoliced community of people without homes. They were among those who first called for a non-policing approach.”

The model is not unique to the United States. In 2005, Stockholm started a program with a psychiatric ambulance – equipped with comfortable seating rather than a stretcher – to respond to mental health emergencies. The ambulance responds to 130 calls a month. It is staffed with a driver and two psychiatric nurses, and for half of the calls, the police also come. While the Swedish program was not about removing resources from the police, it has relieved the police of the responsibility for many psychiatric emergencies.

The New York City program will be modeled after the CAHOOTS initiative in Eugene. It differs from the mobile crisis response services in many other cities because CAHOOTS is hooked directly into the 911 emergency services system. Its website notes that the program has saved money:

“The cost savings are considerable. The CAHOOTS program budget is about $2.1 million annually, while the combined annual budgets for the Eugene and Springfield police departments are $90 million. In 2017, the CAHOOTS teams answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s overall call volume. The program saves the city of Eugene an estimated $8.5 million in public safety spending annually.”

Some worry there is an unpredictable aspect to calls for psychiatric emergencies, and the potential for mental health professions to be injured or killed. Annette Hanson, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at University of Maryland, Baltimore, voiced her concerns, “While multidisciplinary teams are useful, there have been rare cases of violence against responding mental health providers. People with serious mental illness are rarely violent but their dangerousness is unpredictable and cannot be predicted by case screening.”

Daniel Felts is a mental health crisis counselor who has worked at CAHOOTS for the past 4* years. He has responded to about 8,000 calls, and called for police backup only three times to request an immediate "Code 3 cover" when someone's safety has been in danger. Mr. Felts calls the police about once a month for concerns that do not require an immediate response for safety.* “Over the last 4 years, I am only aware of three instances when a team member’s safety was compromised because of a client’s violent behavior. No employee has been seriously physically harmed. In 30 years, with hundreds of thousands (millions?) of calls responded to, no CAHOOTS worker has ever been killed, shot, or stabbed in the line of duty,” Mr. Felts noted.

Emergency calls are screened. “It is not uncommon for CAHOOTS to be dispatched to ‘stage’ for calls involving active disputes or acutely suicidal individuals where means are present. “Staging” entails us parking roughly a mile away while police make first contact and advise whether it is safe for CAHOOTS to engage.”

Mr. Felts went on to discuss the program’s relationship with the community. “ and how we operate. Having operated in Eugene for 30 years, our service is well understood to be one that does not kill, harm, or violate personal boundaries or liberties.”

Would a program like the ones in Stockholm or in Eugene work in other places? Eugene is a city with a population of 172,000 with a low crime rate. Whether a program implemented in one city can be mimicked in another very different city is not clear.

Paul Appelbaum, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York, is optimistic about New York City’s forthcoming program.

“The proposed pilot project in NYC is a real step forward. Work that we’ve done looking at fatal encounters involving the police found that roughly 25% of all deaths at the hands of the police are of people with mental illness. In many of those cases, police were initially called to bring people who were clearly troubled for psychiatric evaluation, but as the situation escalated, the police turned to their weapons to control it, which led to a fatal outcome. Taking police out of the picture whenever possible in favor of trained mental health personnel is clearly a better approach. It will be important for the city to collect good outcome data to enable independent evaluation of the pilot project – not something that political entities are inclined toward, but a critical element in assessing the effectiveness of this approach.”

There are questions that remain about the new program. Mayor de Blasio’s office has not released information about which areas of the city are being chosen for the new program, how much the program will cost, or what the funding source will be. If it can be implemented safely and effectively, it has the potential to provide more sensitive care to patients in crisis, and to save lives.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

*Correction, 11/27/2020: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of years Daniel Felts has worked at CAHOOTS.

“Defund the police”: It’s a slogan, or perhaps a battle cry, that has emerged from the Black Lives Matter movement as a response to race-related police brutality and concerns that people of color are profiled, targeted, arrested, charged, manhandled, and killed by law enforcement in a disproportionate and unjust manner. It crosses into our realm as psychiatrists as mental health emergency calls are handled by the police and not by mental health professionals. The result is sometimes tragic: As many as half of police shootings involve people with psychiatric disorders, and the hope is that many of the police shootings could be avoided if crises were handed by mental health clinicians instead of, or in cooperation with, the police.

At best, police officers receive a week of specialized, crisis intervention training about how to approach those with psychiatric disorders; most officers receive no training. This leaves psychiatry as the only field where medical crises are routinely handled by the police – it is demeaning and embarrassing for some of our patients and dangerous for others. The reality remains, however, that there are times when psychiatric disorders result in violent behavior, and patients being taken for involuntary treatment often resist transport, so either way there is risk, both to the patient and to anyone who responds to a call for assistance.

Early this month, the office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that a major change would be made in how mental health calls to 911 are handled in two “high-need” areas. The mayor’s website states:

“Beginning in February 2021, new Mental Health Teams will use their physical and mental health expertise, and experience in crisis response to de-escalate emergency situations, will help reduce the number of times police will need to respond to 911 mental health calls in these precincts. These teams will have the expertise to respond to a range of behavioral health problems, such as suicide attempts, substance misuse, and serious mental illness, as well as physical health problems, which can be exacerbated by or mask mental health problems. NYC Health + Hospitals will train and provide ongoing technical assistance and support. In selecting team members for this program, FDNY will prioritize professionals with significant experience with mental health crises.”

The press release goes on to say that, in situations where there is a weapon or reason to believe there is a risk of violence, the police will be dispatched along with the new mental health team.

“This is the first time in our history that health professionals will be the default responders to mental health emergencies,” New York City First Lady Chirlane McCray said as she announced the new program. “Treating mental health crises as mental health challenges and not public safety ones is the modern and more appropriate approach.”

New York City is not the first city to employ this model. In the United States, the CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) program in Eugene, Ore., has been run by the White Bird Clinic since 1989 as part of a community policing initiative. Last year, the team responded to 24,000 calls and police backup was required on only 150 of those responses. The CAHOOTS website states:

“The CAHOOTS model has been in the spotlight recently as our nation struggles to reimagine public safety. The program mobilizes two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The CAHOOTS teams deal with a wide range of mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, welfare checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more, relying on trauma-informed de-escalation and harm reduction techniques. CAHOOTS staff are not law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons; their training and experience are the tools they use to ensure a non-violent resolution of crisis situations. They also handle non-emergent medical issues, avoiding costly ambulance transport and emergency room treatment.”

Other cities in the United States are also looking at implementing programs where mental health teams, and not the police, respond to emergency calls. Last year, Oakland, Calif.’s city council invested $40,000 in research to assess how they could best implement a program like the one in Eugene. They hope to begin the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACROS) next year. Sigal Samuel writes in a Vox article, “The goal is to launch the pilot next year with funding from the city budget, and although supporters are not yet sure what its size and duration will be, they’re hopeful it’ll make a big difference to Oakland’s overpoliced community of people without homes. They were among those who first called for a non-policing approach.”

The model is not unique to the United States. In 2005, Stockholm started a program with a psychiatric ambulance – equipped with comfortable seating rather than a stretcher – to respond to mental health emergencies. The ambulance responds to 130 calls a month. It is staffed with a driver and two psychiatric nurses, and for half of the calls, the police also come. While the Swedish program was not about removing resources from the police, it has relieved the police of the responsibility for many psychiatric emergencies.

The New York City program will be modeled after the CAHOOTS initiative in Eugene. It differs from the mobile crisis response services in many other cities because CAHOOTS is hooked directly into the 911 emergency services system. Its website notes that the program has saved money:

“The cost savings are considerable. The CAHOOTS program budget is about $2.1 million annually, while the combined annual budgets for the Eugene and Springfield police departments are $90 million. In 2017, the CAHOOTS teams answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s overall call volume. The program saves the city of Eugene an estimated $8.5 million in public safety spending annually.”

Some worry there is an unpredictable aspect to calls for psychiatric emergencies, and the potential for mental health professions to be injured or killed. Annette Hanson, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at University of Maryland, Baltimore, voiced her concerns, “While multidisciplinary teams are useful, there have been rare cases of violence against responding mental health providers. People with serious mental illness are rarely violent but their dangerousness is unpredictable and cannot be predicted by case screening.”

Daniel Felts is a mental health crisis counselor who has worked at CAHOOTS for the past 4* years. He has responded to about 8,000 calls, and called for police backup only three times to request an immediate "Code 3 cover" when someone's safety has been in danger. Mr. Felts calls the police about once a month for concerns that do not require an immediate response for safety.* “Over the last 4 years, I am only aware of three instances when a team member’s safety was compromised because of a client’s violent behavior. No employee has been seriously physically harmed. In 30 years, with hundreds of thousands (millions?) of calls responded to, no CAHOOTS worker has ever been killed, shot, or stabbed in the line of duty,” Mr. Felts noted.

Emergency calls are screened. “It is not uncommon for CAHOOTS to be dispatched to ‘stage’ for calls involving active disputes or acutely suicidal individuals where means are present. “Staging” entails us parking roughly a mile away while police make first contact and advise whether it is safe for CAHOOTS to engage.”

Mr. Felts went on to discuss the program’s relationship with the community. “ and how we operate. Having operated in Eugene for 30 years, our service is well understood to be one that does not kill, harm, or violate personal boundaries or liberties.”

Would a program like the ones in Stockholm or in Eugene work in other places? Eugene is a city with a population of 172,000 with a low crime rate. Whether a program implemented in one city can be mimicked in another very different city is not clear.

Paul Appelbaum, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York, is optimistic about New York City’s forthcoming program.

“The proposed pilot project in NYC is a real step forward. Work that we’ve done looking at fatal encounters involving the police found that roughly 25% of all deaths at the hands of the police are of people with mental illness. In many of those cases, police were initially called to bring people who were clearly troubled for psychiatric evaluation, but as the situation escalated, the police turned to their weapons to control it, which led to a fatal outcome. Taking police out of the picture whenever possible in favor of trained mental health personnel is clearly a better approach. It will be important for the city to collect good outcome data to enable independent evaluation of the pilot project – not something that political entities are inclined toward, but a critical element in assessing the effectiveness of this approach.”

There are questions that remain about the new program. Mayor de Blasio’s office has not released information about which areas of the city are being chosen for the new program, how much the program will cost, or what the funding source will be. If it can be implemented safely and effectively, it has the potential to provide more sensitive care to patients in crisis, and to save lives.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

*Correction, 11/27/2020: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of years Daniel Felts has worked at CAHOOTS.

“Defund the police”: It’s a slogan, or perhaps a battle cry, that has emerged from the Black Lives Matter movement as a response to race-related police brutality and concerns that people of color are profiled, targeted, arrested, charged, manhandled, and killed by law enforcement in a disproportionate and unjust manner. It crosses into our realm as psychiatrists as mental health emergency calls are handled by the police and not by mental health professionals. The result is sometimes tragic: As many as half of police shootings involve people with psychiatric disorders, and the hope is that many of the police shootings could be avoided if crises were handed by mental health clinicians instead of, or in cooperation with, the police.

At best, police officers receive a week of specialized, crisis intervention training about how to approach those with psychiatric disorders; most officers receive no training. This leaves psychiatry as the only field where medical crises are routinely handled by the police – it is demeaning and embarrassing for some of our patients and dangerous for others. The reality remains, however, that there are times when psychiatric disorders result in violent behavior, and patients being taken for involuntary treatment often resist transport, so either way there is risk, both to the patient and to anyone who responds to a call for assistance.

Early this month, the office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that a major change would be made in how mental health calls to 911 are handled in two “high-need” areas. The mayor’s website states:

“Beginning in February 2021, new Mental Health Teams will use their physical and mental health expertise, and experience in crisis response to de-escalate emergency situations, will help reduce the number of times police will need to respond to 911 mental health calls in these precincts. These teams will have the expertise to respond to a range of behavioral health problems, such as suicide attempts, substance misuse, and serious mental illness, as well as physical health problems, which can be exacerbated by or mask mental health problems. NYC Health + Hospitals will train and provide ongoing technical assistance and support. In selecting team members for this program, FDNY will prioritize professionals with significant experience with mental health crises.”

The press release goes on to say that, in situations where there is a weapon or reason to believe there is a risk of violence, the police will be dispatched along with the new mental health team.

“This is the first time in our history that health professionals will be the default responders to mental health emergencies,” New York City First Lady Chirlane McCray said as she announced the new program. “Treating mental health crises as mental health challenges and not public safety ones is the modern and more appropriate approach.”

New York City is not the first city to employ this model. In the United States, the CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets) program in Eugene, Ore., has been run by the White Bird Clinic since 1989 as part of a community policing initiative. Last year, the team responded to 24,000 calls and police backup was required on only 150 of those responses. The CAHOOTS website states:

“The CAHOOTS model has been in the spotlight recently as our nation struggles to reimagine public safety. The program mobilizes two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field. The CAHOOTS teams deal with a wide range of mental health-related crises, including conflict resolution, welfare checks, substance abuse, suicide threats, and more, relying on trauma-informed de-escalation and harm reduction techniques. CAHOOTS staff are not law enforcement officers and do not carry weapons; their training and experience are the tools they use to ensure a non-violent resolution of crisis situations. They also handle non-emergent medical issues, avoiding costly ambulance transport and emergency room treatment.”

Other cities in the United States are also looking at implementing programs where mental health teams, and not the police, respond to emergency calls. Last year, Oakland, Calif.’s city council invested $40,000 in research to assess how they could best implement a program like the one in Eugene. They hope to begin the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACROS) next year. Sigal Samuel writes in a Vox article, “The goal is to launch the pilot next year with funding from the city budget, and although supporters are not yet sure what its size and duration will be, they’re hopeful it’ll make a big difference to Oakland’s overpoliced community of people without homes. They were among those who first called for a non-policing approach.”

The model is not unique to the United States. In 2005, Stockholm started a program with a psychiatric ambulance – equipped with comfortable seating rather than a stretcher – to respond to mental health emergencies. The ambulance responds to 130 calls a month. It is staffed with a driver and two psychiatric nurses, and for half of the calls, the police also come. While the Swedish program was not about removing resources from the police, it has relieved the police of the responsibility for many psychiatric emergencies.

The New York City program will be modeled after the CAHOOTS initiative in Eugene. It differs from the mobile crisis response services in many other cities because CAHOOTS is hooked directly into the 911 emergency services system. Its website notes that the program has saved money:

“The cost savings are considerable. The CAHOOTS program budget is about $2.1 million annually, while the combined annual budgets for the Eugene and Springfield police departments are $90 million. In 2017, the CAHOOTS teams answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s overall call volume. The program saves the city of Eugene an estimated $8.5 million in public safety spending annually.”

Some worry there is an unpredictable aspect to calls for psychiatric emergencies, and the potential for mental health professions to be injured or killed. Annette Hanson, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at University of Maryland, Baltimore, voiced her concerns, “While multidisciplinary teams are useful, there have been rare cases of violence against responding mental health providers. People with serious mental illness are rarely violent but their dangerousness is unpredictable and cannot be predicted by case screening.”

Daniel Felts is a mental health crisis counselor who has worked at CAHOOTS for the past 4* years. He has responded to about 8,000 calls, and called for police backup only three times to request an immediate "Code 3 cover" when someone's safety has been in danger. Mr. Felts calls the police about once a month for concerns that do not require an immediate response for safety.* “Over the last 4 years, I am only aware of three instances when a team member’s safety was compromised because of a client’s violent behavior. No employee has been seriously physically harmed. In 30 years, with hundreds of thousands (millions?) of calls responded to, no CAHOOTS worker has ever been killed, shot, or stabbed in the line of duty,” Mr. Felts noted.

Emergency calls are screened. “It is not uncommon for CAHOOTS to be dispatched to ‘stage’ for calls involving active disputes or acutely suicidal individuals where means are present. “Staging” entails us parking roughly a mile away while police make first contact and advise whether it is safe for CAHOOTS to engage.”

Mr. Felts went on to discuss the program’s relationship with the community. “ and how we operate. Having operated in Eugene for 30 years, our service is well understood to be one that does not kill, harm, or violate personal boundaries or liberties.”

Would a program like the ones in Stockholm or in Eugene work in other places? Eugene is a city with a population of 172,000 with a low crime rate. Whether a program implemented in one city can be mimicked in another very different city is not clear.

Paul Appelbaum, MD, a forensic psychiatrist at Columbia University, New York, is optimistic about New York City’s forthcoming program.

“The proposed pilot project in NYC is a real step forward. Work that we’ve done looking at fatal encounters involving the police found that roughly 25% of all deaths at the hands of the police are of people with mental illness. In many of those cases, police were initially called to bring people who were clearly troubled for psychiatric evaluation, but as the situation escalated, the police turned to their weapons to control it, which led to a fatal outcome. Taking police out of the picture whenever possible in favor of trained mental health personnel is clearly a better approach. It will be important for the city to collect good outcome data to enable independent evaluation of the pilot project – not something that political entities are inclined toward, but a critical element in assessing the effectiveness of this approach.”

There are questions that remain about the new program. Mayor de Blasio’s office has not released information about which areas of the city are being chosen for the new program, how much the program will cost, or what the funding source will be. If it can be implemented safely and effectively, it has the potential to provide more sensitive care to patients in crisis, and to save lives.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2018). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

*Correction, 11/27/2020: An earlier version of this article misstated the number of years Daniel Felts has worked at CAHOOTS.

Excited delirium: Is it time to change the status quo?

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Siblings of patients with bipolar disorder at increased risk

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder not only face a significantly increased lifetime risk of that affective disorder, but a whole panoply of other psychiatric disorders, according to a new Danish longitudinal national registry study.

“Our data show the healthy siblings of patients with bipolar disorder are themselves at increased risk of developing any kind of psychiatric disorder. Mainly bipolar disorder, but all other kinds as well,” Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DMSc, said in presenting the results of the soon-to-be-published Danish study at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Moreover, the long-term Danish study also demonstrated that several major psychiatric disorders follow a previously unappreciated bimodal distribution of age of onset in the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, the incidence of new-onset bipolar disorder and unipolar depression in the siblings was markedly increased during youth and early adulthood, compared with controls drawn from the general Danish population. Then, incidence rates dropped off and plateaued at a lower level in midlife before surging after age 60 years. The same was true for somatoform disorders as well as alcohol and substance use disorders.

“Strategies to prevent onset of psychiatric illness in individuals with a first-generation family history of bipolar disorder should not be limited to adolescence and early adulthood but should be lifelong, likely with differentiated age-specific approaches. And this is not now the case.

“Generally, most researchers and clinicians are focusing more on the early part of life and not the later part of life from age 60 and up, even though this is indeed also a risk period for any kind of psychiatric illness as well as bipolar disorder,” according to Dr. Kessing, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Kessing, a past recipient of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research Award, also described his research group’s successful innovative efforts to prevent first recurrences after a single manic episode or bipolar disorder.

Danish national sibling study

The longitudinal registry study included all 19,995 Danish patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder during 1995-2017, along with 13,923 of their siblings and 278,460 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from the general population.

The cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was 66% greater in siblings than controls. Leading the way was a 374% increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Strategies to prevent a first relapse of bipolar disorder

Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated in a meta-analysis that, with current standard therapies, the risk of recurrence among patients after a single manic or mixed episode is high in both adult and pediatric patients. In three studies of adults, the risk of recurrence was 35% during the first year after recovery from the index episode and 59% at 2 years. In three studies of children and adolescents, the risk of recurrence within 1 year after recovery was 40% in children and 52% in adolescents. This makes a compelling case for starting maintenance therapy following onset of a single manic or mixed episode, according to the investigators.

More than half a decade ago, Dr. Kessing and colleagues demonstrated in a study of 4,714 Danish patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed lithium while in a psychiatric hospital that those who started the drug for prophylaxis early – that is, following their first psychiatric contact – had a significantly higher response to lithium monotherapy than those who started it only after repeated contacts. Indeed, their risk of nonresponse to lithium prophylaxis as evidenced by repeat hospital admission after a 6-month lithium stabilization period was 13% lower than in those starting the drug later.

Early intervention aiming to stop clinical progression of bipolar disorder intuitively seems appealing, so Dr. Kessing and colleagues created a specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic combining optimized pharmacotherapy and evidence-based group psychoeducation. They then put it to the test in a clinical trial in which 158 patients discharged from an initial psychiatric hospital admission for bipolar disorder were randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic or standard care.

The rate of psychiatric hospital readmission within the next 6 years was 40% lower in the group assigned to the specialized early intervention clinic. Their rate of adherence to medication – mostly lithium and antipsychotics – was significantly higher. So were their treatment satisfaction scores. And the clincher: The total net direct cost of treatment in the specialized mood disorders clinic averaged 3,194 euro less per patient, an 11% reduction relative to the cost of standard care, a striking economic benefit achieved mainly through avoided hospitalizations.

In a subsequent subgroup analysis of the randomized trial data, Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated that young adults with bipolar disorder not only benefited from participation in the specialized outpatient clinic, but they appeared to have derived greater benefit than the older patients. The rehospitalization rate was 67% lower in 18- to 25-year-old patients randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorder clinic than in standard-care controls, compared with a 32% relative risk reduction in outpatient clinic patients aged 26 years or older).

“There are now several centers around the world which also use this model involving early intervention,” Dr. Kessing said. “It is so important that, when the diagnosis is made for the first time, the patient gets sufficient evidence-based treatment comprised of mood maintenance medication as well as group-based psychoeducation, which is the psychotherapeutic intervention for which there is the strongest evidence of an effect.”

The sibling study was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Kessing reported serving as a consultant to Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Kessing LV. ECNP 2020, Session S.25.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder not only face a significantly increased lifetime risk of that affective disorder, but a whole panoply of other psychiatric disorders, according to a new Danish longitudinal national registry study.

“Our data show the healthy siblings of patients with bipolar disorder are themselves at increased risk of developing any kind of psychiatric disorder. Mainly bipolar disorder, but all other kinds as well,” Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DMSc, said in presenting the results of the soon-to-be-published Danish study at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Moreover, the long-term Danish study also demonstrated that several major psychiatric disorders follow a previously unappreciated bimodal distribution of age of onset in the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, the incidence of new-onset bipolar disorder and unipolar depression in the siblings was markedly increased during youth and early adulthood, compared with controls drawn from the general Danish population. Then, incidence rates dropped off and plateaued at a lower level in midlife before surging after age 60 years. The same was true for somatoform disorders as well as alcohol and substance use disorders.

“Strategies to prevent onset of psychiatric illness in individuals with a first-generation family history of bipolar disorder should not be limited to adolescence and early adulthood but should be lifelong, likely with differentiated age-specific approaches. And this is not now the case.

“Generally, most researchers and clinicians are focusing more on the early part of life and not the later part of life from age 60 and up, even though this is indeed also a risk period for any kind of psychiatric illness as well as bipolar disorder,” according to Dr. Kessing, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Kessing, a past recipient of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research Award, also described his research group’s successful innovative efforts to prevent first recurrences after a single manic episode or bipolar disorder.

Danish national sibling study

The longitudinal registry study included all 19,995 Danish patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder during 1995-2017, along with 13,923 of their siblings and 278,460 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from the general population.

The cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was 66% greater in siblings than controls. Leading the way was a 374% increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Strategies to prevent a first relapse of bipolar disorder

Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated in a meta-analysis that, with current standard therapies, the risk of recurrence among patients after a single manic or mixed episode is high in both adult and pediatric patients. In three studies of adults, the risk of recurrence was 35% during the first year after recovery from the index episode and 59% at 2 years. In three studies of children and adolescents, the risk of recurrence within 1 year after recovery was 40% in children and 52% in adolescents. This makes a compelling case for starting maintenance therapy following onset of a single manic or mixed episode, according to the investigators.

More than half a decade ago, Dr. Kessing and colleagues demonstrated in a study of 4,714 Danish patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed lithium while in a psychiatric hospital that those who started the drug for prophylaxis early – that is, following their first psychiatric contact – had a significantly higher response to lithium monotherapy than those who started it only after repeated contacts. Indeed, their risk of nonresponse to lithium prophylaxis as evidenced by repeat hospital admission after a 6-month lithium stabilization period was 13% lower than in those starting the drug later.

Early intervention aiming to stop clinical progression of bipolar disorder intuitively seems appealing, so Dr. Kessing and colleagues created a specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic combining optimized pharmacotherapy and evidence-based group psychoeducation. They then put it to the test in a clinical trial in which 158 patients discharged from an initial psychiatric hospital admission for bipolar disorder were randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic or standard care.

The rate of psychiatric hospital readmission within the next 6 years was 40% lower in the group assigned to the specialized early intervention clinic. Their rate of adherence to medication – mostly lithium and antipsychotics – was significantly higher. So were their treatment satisfaction scores. And the clincher: The total net direct cost of treatment in the specialized mood disorders clinic averaged 3,194 euro less per patient, an 11% reduction relative to the cost of standard care, a striking economic benefit achieved mainly through avoided hospitalizations.