User login

Study eyes impact of isotretinoin on triglycerides, other lab measures

.

“Isotretinoin is a very effective treatment for severe acne,” Varsha Parthasarathy said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, initiating this medication requires a complex process of laboratory testing,” which includes human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy testing, because isotretinoin is a teratogen, as well as lipid labs and liver function tests, she noted. “Importantly, triglycerides are measured due to an association in adults between isotretinoin and hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. However, these findings in children are limited to case reports, as are findings of retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity.”

To identify the role of isotretinoin on changes in lipids, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and to determine the impact on treatment course, Ms. Parthasarathy, a 4-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the charts of 130 patients aged 12-21 years who were cared for at Children’s National Hospital between January 2012 and October 2020. Nearly two-thirds (65%) were male, their average age was 16 years, and the mean time to obtain follow-up labs after starting isotretinoin was 3.25 months.

Between baseline and follow-up, the researchers observed increases in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL (P less than .001 for all associations) and a decrease in HDL (P = .001), but there were no significant changes in AST or ALT levels. These findings were consistent with prior studies in adults examining the utility of these laboratory tests, most notably a 2016 study by Timothy J. Hansen, MD, and colleagues.

Among the 13 patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline, 9 (69%) were overweight or obese. Of the 20 patients with elevated triglycerides at follow-up, 11 patients (55%) were obese. At follow-up, 11 patients had levels of 200-500 mg/dL (grade I elevation), and 2 patients had levels of 501-1,000 mg/dL (grade II elevation). Isotretinoin was stopped in the latter two patients, who also had obesity as a risk factor for their hypertriglyceridemia.

“None of these patients had clinical sequelae from their hypertriglyceridemia, such as pancreatitis at baseline or follow-up,” Ms. Parthasarathy said. “However, since pancreatitis would be expected to be exceedingly rare, the sample size may be limited in identifying this adverse effect.”

She noted that while isotretinoin might cause a significant increase in lipid levels, the mean levels remained within normal limits at both baseline and follow-up. “Of the patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline and follow-up, obesity may have been a potential risk factor,” she said. “This could suggest a possible strategy for reduced testing in nonobese isotretinoin patients, which can be further explored in larger study populations.”

In addition, “there was a lack of significant change in AST and ALT in this study and adult studies, as well as minimal evidence for pediatric retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity, which raises the question of the necessity of baseline and follow-up comprehensive metabolic panel testing,” Ms. Parthasarathy added. “Clinicians must weigh the laboratory values with the costs of laboratory testing, including opportunity costs such as time, monetary costs, and the discomfort of testing for pediatric patients.”

The study’s senior author was A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

.

“Isotretinoin is a very effective treatment for severe acne,” Varsha Parthasarathy said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, initiating this medication requires a complex process of laboratory testing,” which includes human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy testing, because isotretinoin is a teratogen, as well as lipid labs and liver function tests, she noted. “Importantly, triglycerides are measured due to an association in adults between isotretinoin and hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. However, these findings in children are limited to case reports, as are findings of retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity.”

To identify the role of isotretinoin on changes in lipids, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and to determine the impact on treatment course, Ms. Parthasarathy, a 4-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the charts of 130 patients aged 12-21 years who were cared for at Children’s National Hospital between January 2012 and October 2020. Nearly two-thirds (65%) were male, their average age was 16 years, and the mean time to obtain follow-up labs after starting isotretinoin was 3.25 months.

Between baseline and follow-up, the researchers observed increases in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL (P less than .001 for all associations) and a decrease in HDL (P = .001), but there were no significant changes in AST or ALT levels. These findings were consistent with prior studies in adults examining the utility of these laboratory tests, most notably a 2016 study by Timothy J. Hansen, MD, and colleagues.

Among the 13 patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline, 9 (69%) were overweight or obese. Of the 20 patients with elevated triglycerides at follow-up, 11 patients (55%) were obese. At follow-up, 11 patients had levels of 200-500 mg/dL (grade I elevation), and 2 patients had levels of 501-1,000 mg/dL (grade II elevation). Isotretinoin was stopped in the latter two patients, who also had obesity as a risk factor for their hypertriglyceridemia.

“None of these patients had clinical sequelae from their hypertriglyceridemia, such as pancreatitis at baseline or follow-up,” Ms. Parthasarathy said. “However, since pancreatitis would be expected to be exceedingly rare, the sample size may be limited in identifying this adverse effect.”

She noted that while isotretinoin might cause a significant increase in lipid levels, the mean levels remained within normal limits at both baseline and follow-up. “Of the patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline and follow-up, obesity may have been a potential risk factor,” she said. “This could suggest a possible strategy for reduced testing in nonobese isotretinoin patients, which can be further explored in larger study populations.”

In addition, “there was a lack of significant change in AST and ALT in this study and adult studies, as well as minimal evidence for pediatric retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity, which raises the question of the necessity of baseline and follow-up comprehensive metabolic panel testing,” Ms. Parthasarathy added. “Clinicians must weigh the laboratory values with the costs of laboratory testing, including opportunity costs such as time, monetary costs, and the discomfort of testing for pediatric patients.”

The study’s senior author was A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

.

“Isotretinoin is a very effective treatment for severe acne,” Varsha Parthasarathy said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “However, initiating this medication requires a complex process of laboratory testing,” which includes human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy testing, because isotretinoin is a teratogen, as well as lipid labs and liver function tests, she noted. “Importantly, triglycerides are measured due to an association in adults between isotretinoin and hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. However, these findings in children are limited to case reports, as are findings of retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity.”

To identify the role of isotretinoin on changes in lipids, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and to determine the impact on treatment course, Ms. Parthasarathy, a 4-year medical student at George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the charts of 130 patients aged 12-21 years who were cared for at Children’s National Hospital between January 2012 and October 2020. Nearly two-thirds (65%) were male, their average age was 16 years, and the mean time to obtain follow-up labs after starting isotretinoin was 3.25 months.

Between baseline and follow-up, the researchers observed increases in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL (P less than .001 for all associations) and a decrease in HDL (P = .001), but there were no significant changes in AST or ALT levels. These findings were consistent with prior studies in adults examining the utility of these laboratory tests, most notably a 2016 study by Timothy J. Hansen, MD, and colleagues.

Among the 13 patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline, 9 (69%) were overweight or obese. Of the 20 patients with elevated triglycerides at follow-up, 11 patients (55%) were obese. At follow-up, 11 patients had levels of 200-500 mg/dL (grade I elevation), and 2 patients had levels of 501-1,000 mg/dL (grade II elevation). Isotretinoin was stopped in the latter two patients, who also had obesity as a risk factor for their hypertriglyceridemia.

“None of these patients had clinical sequelae from their hypertriglyceridemia, such as pancreatitis at baseline or follow-up,” Ms. Parthasarathy said. “However, since pancreatitis would be expected to be exceedingly rare, the sample size may be limited in identifying this adverse effect.”

She noted that while isotretinoin might cause a significant increase in lipid levels, the mean levels remained within normal limits at both baseline and follow-up. “Of the patients with elevated triglycerides at baseline and follow-up, obesity may have been a potential risk factor,” she said. “This could suggest a possible strategy for reduced testing in nonobese isotretinoin patients, which can be further explored in larger study populations.”

In addition, “there was a lack of significant change in AST and ALT in this study and adult studies, as well as minimal evidence for pediatric retinoid-induced hepatotoxicity, which raises the question of the necessity of baseline and follow-up comprehensive metabolic panel testing,” Ms. Parthasarathy added. “Clinicians must weigh the laboratory values with the costs of laboratory testing, including opportunity costs such as time, monetary costs, and the discomfort of testing for pediatric patients.”

The study’s senior author was A. Yasmine Kirkorian, MD, chief of dermatology at Children’s National Hospital, Washington. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM SPD 2021

Isotretinoin benefits similar in overweight, obese adolescents, and those in normal weight range

a retrospective cohort study found.

“Oral isotretinoin is among the most effective treatments for acne and is indicated for the treatment of severe acne or when first-line regimens have failed,” Maggie Tallmadge said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. In adolescents with acne, isotretinoin is prescribed at a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg per day “with the goal of reaching a cumulative dose of 120-150 mg/kg and clinical clearance with durable remission,” she said. “Most providers do not prescribe a daily dose over 80 mg due to perceived increased risk of side effects, including xerosis, cheilitis, liver dysfunction, and acne flare. However, many adolescents weigh over 80 kg and are therefore effectively underdosed, prolonging treatment time and possibly increasing the risk of side effects due to prolonged therapy.”

To evaluate differences in treatment courses among normal-weight, overweight, and obese adolescents, and the efficacy and safety of treatment, Ms. Tallmadge, a third-year medical student at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues completed a retrospective chart review of 550 dermatology patients at Children’s Wisconsin, also in Milwaukee, who completed at least 2 months of isotretinoin treatment for acne when they were between the ages of 10 and 24, from November 2012 to January 2020. They collected data on age, weight, height, daily dose, cumulative dose, time to acne clearance, side effects, and acne recurrence after treatment, and classified patients as normal weight, overweight, or obese based on their body mass index for age percentile.

Of the 550 patients, 367 (67%) were normal weight, 101 (18%) were overweight, and 82 (15%) were obese. The median age of those in the normal-weight and overweight groups was 16, and was 15 in the obese group.

There was were significant differences in the median cumulative dose in each weight group: 143.7 mg/kg for normal-weight patients, 138.2 mg/kg for overweight patients, and 140.6 mg/kg for obese patients (P < .001).

“Despite achieving different cumulative doses, there was no difference in acne clearance, relapse, and most side effects among the three [body mass index] cohorts,” Ms. Tallmadge said. “Thus, it appears that current treatment strategies may be appropriate for overweight and obese adolescents.”

The proportion of patients with acne clearance did not differ significantly among the three groups of patients: 62% who were in the normal weight range, 60% who were overweight, and 59% who were obese had clearance of facial acne with treatment (P = .84).

Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, the proportion with acne recurrences was similar between the three groups: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients (P > .05). Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, there was no significant differences in acne recurrence: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients.

However, the proportion of patients reporting headaches differed significantly between the groups: 29% of normal-weight patients, compared with 40% of both overweight and obese patients (P = .035). The researchers also observed a significant positive correlation between increased BMI and increased triglyceride and ALT levels during treatment (P < .001 for both associations), yet no elevations required clinical action.

Funding for the study was provided by the MCW Medical Student Summer Research Program and the American Acne & Rosacea Society.

a retrospective cohort study found.

“Oral isotretinoin is among the most effective treatments for acne and is indicated for the treatment of severe acne or when first-line regimens have failed,” Maggie Tallmadge said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. In adolescents with acne, isotretinoin is prescribed at a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg per day “with the goal of reaching a cumulative dose of 120-150 mg/kg and clinical clearance with durable remission,” she said. “Most providers do not prescribe a daily dose over 80 mg due to perceived increased risk of side effects, including xerosis, cheilitis, liver dysfunction, and acne flare. However, many adolescents weigh over 80 kg and are therefore effectively underdosed, prolonging treatment time and possibly increasing the risk of side effects due to prolonged therapy.”

To evaluate differences in treatment courses among normal-weight, overweight, and obese adolescents, and the efficacy and safety of treatment, Ms. Tallmadge, a third-year medical student at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues completed a retrospective chart review of 550 dermatology patients at Children’s Wisconsin, also in Milwaukee, who completed at least 2 months of isotretinoin treatment for acne when they were between the ages of 10 and 24, from November 2012 to January 2020. They collected data on age, weight, height, daily dose, cumulative dose, time to acne clearance, side effects, and acne recurrence after treatment, and classified patients as normal weight, overweight, or obese based on their body mass index for age percentile.

Of the 550 patients, 367 (67%) were normal weight, 101 (18%) were overweight, and 82 (15%) were obese. The median age of those in the normal-weight and overweight groups was 16, and was 15 in the obese group.

There was were significant differences in the median cumulative dose in each weight group: 143.7 mg/kg for normal-weight patients, 138.2 mg/kg for overweight patients, and 140.6 mg/kg for obese patients (P < .001).

“Despite achieving different cumulative doses, there was no difference in acne clearance, relapse, and most side effects among the three [body mass index] cohorts,” Ms. Tallmadge said. “Thus, it appears that current treatment strategies may be appropriate for overweight and obese adolescents.”

The proportion of patients with acne clearance did not differ significantly among the three groups of patients: 62% who were in the normal weight range, 60% who were overweight, and 59% who were obese had clearance of facial acne with treatment (P = .84).

Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, the proportion with acne recurrences was similar between the three groups: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients (P > .05). Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, there was no significant differences in acne recurrence: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients.

However, the proportion of patients reporting headaches differed significantly between the groups: 29% of normal-weight patients, compared with 40% of both overweight and obese patients (P = .035). The researchers also observed a significant positive correlation between increased BMI and increased triglyceride and ALT levels during treatment (P < .001 for both associations), yet no elevations required clinical action.

Funding for the study was provided by the MCW Medical Student Summer Research Program and the American Acne & Rosacea Society.

a retrospective cohort study found.

“Oral isotretinoin is among the most effective treatments for acne and is indicated for the treatment of severe acne or when first-line regimens have failed,” Maggie Tallmadge said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. In adolescents with acne, isotretinoin is prescribed at a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg per day “with the goal of reaching a cumulative dose of 120-150 mg/kg and clinical clearance with durable remission,” she said. “Most providers do not prescribe a daily dose over 80 mg due to perceived increased risk of side effects, including xerosis, cheilitis, liver dysfunction, and acne flare. However, many adolescents weigh over 80 kg and are therefore effectively underdosed, prolonging treatment time and possibly increasing the risk of side effects due to prolonged therapy.”

To evaluate differences in treatment courses among normal-weight, overweight, and obese adolescents, and the efficacy and safety of treatment, Ms. Tallmadge, a third-year medical student at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues completed a retrospective chart review of 550 dermatology patients at Children’s Wisconsin, also in Milwaukee, who completed at least 2 months of isotretinoin treatment for acne when they were between the ages of 10 and 24, from November 2012 to January 2020. They collected data on age, weight, height, daily dose, cumulative dose, time to acne clearance, side effects, and acne recurrence after treatment, and classified patients as normal weight, overweight, or obese based on their body mass index for age percentile.

Of the 550 patients, 367 (67%) were normal weight, 101 (18%) were overweight, and 82 (15%) were obese. The median age of those in the normal-weight and overweight groups was 16, and was 15 in the obese group.

There was were significant differences in the median cumulative dose in each weight group: 143.7 mg/kg for normal-weight patients, 138.2 mg/kg for overweight patients, and 140.6 mg/kg for obese patients (P < .001).

“Despite achieving different cumulative doses, there was no difference in acne clearance, relapse, and most side effects among the three [body mass index] cohorts,” Ms. Tallmadge said. “Thus, it appears that current treatment strategies may be appropriate for overweight and obese adolescents.”

The proportion of patients with acne clearance did not differ significantly among the three groups of patients: 62% who were in the normal weight range, 60% who were overweight, and 59% who were obese had clearance of facial acne with treatment (P = .84).

Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, the proportion with acne recurrences was similar between the three groups: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients (P > .05). Of patients whose treatment course was completed by the time of data collection, there was no significant differences in acne recurrence: 25% of normal-weight patients, 27% of overweight patients, and 35% of obese patients.

However, the proportion of patients reporting headaches differed significantly between the groups: 29% of normal-weight patients, compared with 40% of both overweight and obese patients (P = .035). The researchers also observed a significant positive correlation between increased BMI and increased triglyceride and ALT levels during treatment (P < .001 for both associations), yet no elevations required clinical action.

Funding for the study was provided by the MCW Medical Student Summer Research Program and the American Acne & Rosacea Society.

FROM SPD 2021

‘Treat youth with gender dysphoria as individuals’

Young people with gender dysphoria should be considered as individuals rather than fall into an age-defined bracket when assessing their understanding to consent to hormone treatment, according to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, as it awaits the verdict of its recent appeal in London against a High Court ruling.

The High Court ruling, made in December 2020 as reported by this news organization, stated that adolescents with gender dysphoria were unlikely to fully understand the consequences of hormone treatment for gender reassignment and was the result of a case brought by 24-year-old Keira Bell, who transitioned from female to male at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), starting at the age of 16, but later “detransitioned.”

Along with changes made to rules around prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors with gender dysphoria in countries such as Finland and Sweden, the English ruling signals a more cautious approach to any medical treatment for such children, as detailed in a feature published in April.

However, during the appeal, The Trust argued once more that puberty blockers give children time to “consider options” about their bodies and that the decision (the December ruling) was inconsistent with the law that “entitles children under the age of 16 to make decisions for themselves after being assessed as competent to do so by their doctor.”

Alongside other organizations, the United States–based Endocrine Society submitted written evidence in support of the Tavistock. “The High Court’s decision, if it is allowed to stand, would set a harmful precedent preventing physicians from providing transgender and gender diverse youth with high-quality medical care,” it noted in a statement.

Defending the High Court’s ruling, the lawyer for Ms. Bell said its conclusion was that puberty blockers for gender dysphoria are an “experimental” treatment with a very limited evidence base.

“The judgment of the [High Court] is entirely correct, and there is no proper basis for overturning it,” he asserted.

The 2-day appeal hearing ended on June 24, and a ruling will be made at a later date.

Do children understand the consequences of hormone treatment?

One central aspect of the overall case is the fact that Ms. Bell regrets her decision to transition at age 16, saying she only received three counseling sessions prior to endocrinology referral. And she consequently had a mastectomy at age 20, which she also bitterly regrets.

So a key concern is whether young people fully understand the consequences of taking puberty blockers and therapies that may follow, including cross-sex hormones.

Witness for the appeal Gary Butler, MD, consultant in pediatric and adolescent endocrinology at University College Hospital, London, where children are referred to from GIDS for hormone treatment, said the number of children who go on to cross-sex hormones from puberty blockers is “over 80%.”

But the actual number of children who are referred to endocrinology services (where puberty blockers are initiated) from GIDS is low, at approximately 16%, according to 2019-2020 data, said a GIDS spokesperson.

“Once at the endocrinology service, young people either participate in a group education session, or if under 15 years, an individualized session between the clinician and the patient and family members,” she added. The Trust also maintained that initiation of cross-sex hormones “is separate from the prescription of puberty blockers.”

Since the December ruling, The Trust has put in place multidisciplinary clinical reviews (MDCR) of cases, and in July, NHS England will start implementing an independent multidisciplinary professional review (MDPR) to check that the GIDS has followed due process with each case.

Slow the process down, give appropriate psychotherapy

Stella O’Malley is a psychotherapist who works with transitioners and detransitioners and is a founding member of the International Association of Therapists for Desisters and Detransitioners (IATDD).

Whatever the outcome of the appeal process, Ms. O’Malley said she would like to see the Tavistock slow down and take a broader approach to counseling children before referral to endocrinology services.

In discussing therapy prior to transition, Ms. O’Malley stated that her clients often say they did not explore their inner motivations or other possible reasons for their distress, and the therapy was focused more on when they transition, rather than being sure it was something they wanted to do.

“We need to learn from the mistakes made with people like Keira Bell. , especially when [children are] ... young and especially when they’re traumatized,” Ms. O’Malley said.

“Had they received a more conventional therapy, they might have thought about their decision from different perspectives and in the process acquired more self-awareness, which would have been more beneficial.”

“The ‘affirmative’ approach to gender therapy is too narrow; we need to look at the whole individual. Therapy in other areas would never disregard other, nongender issues such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or anxiety [which often co-exist with gender dysphoria] – issues bleed into each other,” Ms. O’Malley pointed out. “We need a more exploratory approach.”

“I’d also like to see other therapists all over the [U.K.] who are perfectly qualified and capable of working with gender actually start working with gender issues,” she said, noting that such an approach might also help reduce the long waiting list at the Tavistock.

The latter had been overwhelmed, and this led to a speeding up of the assessment process, which led to a number of professionals resigning from the service in recent years, saying children were being “fast-tracked” to medical transition.

Fertility and sexual function are complex issues for kids

Also asked to comment was Claire Graham, from Genspect, a group that describes itself as a voice for parents of gender-questioning kids.

She told this news organization that “parents are rightly concerned about their children’s ability to consent to treatments that may lead to infertility and issues surrounding sexual function.” She added that other countries in Europe were changing their approach. “Look to Sweden and Finland, who have both rowed back on puberty blockers and no longer recommend them.”

Ms. Graham, who has worked with children with differences in sexual development, added that it was very difficult for children and young people to understand the life-long implications of decisions made at an early age.

“How can children understand what it is to live with impaired sexual functioning if they have never had sex? Likewise, fertility is a complex issue. Most people do not want to become parents as teenagers, but we understand that this will often change as they grow,” said Ms. Graham.

“Many parents worry that their child is not being considered in the whole [and] that their child’s ability to consent to medical interventions for gender dysphoria is impacted by comorbidities, such as a diagnosis of autism or a history of mental health issues. These children are particularly vulnerable.”

“At Genspect, we hope that the decision from the ... court is upheld,” Ms. Graham concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young people with gender dysphoria should be considered as individuals rather than fall into an age-defined bracket when assessing their understanding to consent to hormone treatment, according to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, as it awaits the verdict of its recent appeal in London against a High Court ruling.

The High Court ruling, made in December 2020 as reported by this news organization, stated that adolescents with gender dysphoria were unlikely to fully understand the consequences of hormone treatment for gender reassignment and was the result of a case brought by 24-year-old Keira Bell, who transitioned from female to male at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), starting at the age of 16, but later “detransitioned.”

Along with changes made to rules around prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors with gender dysphoria in countries such as Finland and Sweden, the English ruling signals a more cautious approach to any medical treatment for such children, as detailed in a feature published in April.

However, during the appeal, The Trust argued once more that puberty blockers give children time to “consider options” about their bodies and that the decision (the December ruling) was inconsistent with the law that “entitles children under the age of 16 to make decisions for themselves after being assessed as competent to do so by their doctor.”

Alongside other organizations, the United States–based Endocrine Society submitted written evidence in support of the Tavistock. “The High Court’s decision, if it is allowed to stand, would set a harmful precedent preventing physicians from providing transgender and gender diverse youth with high-quality medical care,” it noted in a statement.

Defending the High Court’s ruling, the lawyer for Ms. Bell said its conclusion was that puberty blockers for gender dysphoria are an “experimental” treatment with a very limited evidence base.

“The judgment of the [High Court] is entirely correct, and there is no proper basis for overturning it,” he asserted.

The 2-day appeal hearing ended on June 24, and a ruling will be made at a later date.

Do children understand the consequences of hormone treatment?

One central aspect of the overall case is the fact that Ms. Bell regrets her decision to transition at age 16, saying she only received three counseling sessions prior to endocrinology referral. And she consequently had a mastectomy at age 20, which she also bitterly regrets.

So a key concern is whether young people fully understand the consequences of taking puberty blockers and therapies that may follow, including cross-sex hormones.

Witness for the appeal Gary Butler, MD, consultant in pediatric and adolescent endocrinology at University College Hospital, London, where children are referred to from GIDS for hormone treatment, said the number of children who go on to cross-sex hormones from puberty blockers is “over 80%.”

But the actual number of children who are referred to endocrinology services (where puberty blockers are initiated) from GIDS is low, at approximately 16%, according to 2019-2020 data, said a GIDS spokesperson.

“Once at the endocrinology service, young people either participate in a group education session, or if under 15 years, an individualized session between the clinician and the patient and family members,” she added. The Trust also maintained that initiation of cross-sex hormones “is separate from the prescription of puberty blockers.”

Since the December ruling, The Trust has put in place multidisciplinary clinical reviews (MDCR) of cases, and in July, NHS England will start implementing an independent multidisciplinary professional review (MDPR) to check that the GIDS has followed due process with each case.

Slow the process down, give appropriate psychotherapy

Stella O’Malley is a psychotherapist who works with transitioners and detransitioners and is a founding member of the International Association of Therapists for Desisters and Detransitioners (IATDD).

Whatever the outcome of the appeal process, Ms. O’Malley said she would like to see the Tavistock slow down and take a broader approach to counseling children before referral to endocrinology services.

In discussing therapy prior to transition, Ms. O’Malley stated that her clients often say they did not explore their inner motivations or other possible reasons for their distress, and the therapy was focused more on when they transition, rather than being sure it was something they wanted to do.

“We need to learn from the mistakes made with people like Keira Bell. , especially when [children are] ... young and especially when they’re traumatized,” Ms. O’Malley said.

“Had they received a more conventional therapy, they might have thought about their decision from different perspectives and in the process acquired more self-awareness, which would have been more beneficial.”

“The ‘affirmative’ approach to gender therapy is too narrow; we need to look at the whole individual. Therapy in other areas would never disregard other, nongender issues such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or anxiety [which often co-exist with gender dysphoria] – issues bleed into each other,” Ms. O’Malley pointed out. “We need a more exploratory approach.”

“I’d also like to see other therapists all over the [U.K.] who are perfectly qualified and capable of working with gender actually start working with gender issues,” she said, noting that such an approach might also help reduce the long waiting list at the Tavistock.

The latter had been overwhelmed, and this led to a speeding up of the assessment process, which led to a number of professionals resigning from the service in recent years, saying children were being “fast-tracked” to medical transition.

Fertility and sexual function are complex issues for kids

Also asked to comment was Claire Graham, from Genspect, a group that describes itself as a voice for parents of gender-questioning kids.

She told this news organization that “parents are rightly concerned about their children’s ability to consent to treatments that may lead to infertility and issues surrounding sexual function.” She added that other countries in Europe were changing their approach. “Look to Sweden and Finland, who have both rowed back on puberty blockers and no longer recommend them.”

Ms. Graham, who has worked with children with differences in sexual development, added that it was very difficult for children and young people to understand the life-long implications of decisions made at an early age.

“How can children understand what it is to live with impaired sexual functioning if they have never had sex? Likewise, fertility is a complex issue. Most people do not want to become parents as teenagers, but we understand that this will often change as they grow,” said Ms. Graham.

“Many parents worry that their child is not being considered in the whole [and] that their child’s ability to consent to medical interventions for gender dysphoria is impacted by comorbidities, such as a diagnosis of autism or a history of mental health issues. These children are particularly vulnerable.”

“At Genspect, we hope that the decision from the ... court is upheld,” Ms. Graham concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young people with gender dysphoria should be considered as individuals rather than fall into an age-defined bracket when assessing their understanding to consent to hormone treatment, according to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, as it awaits the verdict of its recent appeal in London against a High Court ruling.

The High Court ruling, made in December 2020 as reported by this news organization, stated that adolescents with gender dysphoria were unlikely to fully understand the consequences of hormone treatment for gender reassignment and was the result of a case brought by 24-year-old Keira Bell, who transitioned from female to male at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), starting at the age of 16, but later “detransitioned.”

Along with changes made to rules around prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors with gender dysphoria in countries such as Finland and Sweden, the English ruling signals a more cautious approach to any medical treatment for such children, as detailed in a feature published in April.

However, during the appeal, The Trust argued once more that puberty blockers give children time to “consider options” about their bodies and that the decision (the December ruling) was inconsistent with the law that “entitles children under the age of 16 to make decisions for themselves after being assessed as competent to do so by their doctor.”

Alongside other organizations, the United States–based Endocrine Society submitted written evidence in support of the Tavistock. “The High Court’s decision, if it is allowed to stand, would set a harmful precedent preventing physicians from providing transgender and gender diverse youth with high-quality medical care,” it noted in a statement.

Defending the High Court’s ruling, the lawyer for Ms. Bell said its conclusion was that puberty blockers for gender dysphoria are an “experimental” treatment with a very limited evidence base.

“The judgment of the [High Court] is entirely correct, and there is no proper basis for overturning it,” he asserted.

The 2-day appeal hearing ended on June 24, and a ruling will be made at a later date.

Do children understand the consequences of hormone treatment?

One central aspect of the overall case is the fact that Ms. Bell regrets her decision to transition at age 16, saying she only received three counseling sessions prior to endocrinology referral. And she consequently had a mastectomy at age 20, which she also bitterly regrets.

So a key concern is whether young people fully understand the consequences of taking puberty blockers and therapies that may follow, including cross-sex hormones.

Witness for the appeal Gary Butler, MD, consultant in pediatric and adolescent endocrinology at University College Hospital, London, where children are referred to from GIDS for hormone treatment, said the number of children who go on to cross-sex hormones from puberty blockers is “over 80%.”

But the actual number of children who are referred to endocrinology services (where puberty blockers are initiated) from GIDS is low, at approximately 16%, according to 2019-2020 data, said a GIDS spokesperson.

“Once at the endocrinology service, young people either participate in a group education session, or if under 15 years, an individualized session between the clinician and the patient and family members,” she added. The Trust also maintained that initiation of cross-sex hormones “is separate from the prescription of puberty blockers.”

Since the December ruling, The Trust has put in place multidisciplinary clinical reviews (MDCR) of cases, and in July, NHS England will start implementing an independent multidisciplinary professional review (MDPR) to check that the GIDS has followed due process with each case.

Slow the process down, give appropriate psychotherapy

Stella O’Malley is a psychotherapist who works with transitioners and detransitioners and is a founding member of the International Association of Therapists for Desisters and Detransitioners (IATDD).

Whatever the outcome of the appeal process, Ms. O’Malley said she would like to see the Tavistock slow down and take a broader approach to counseling children before referral to endocrinology services.

In discussing therapy prior to transition, Ms. O’Malley stated that her clients often say they did not explore their inner motivations or other possible reasons for their distress, and the therapy was focused more on when they transition, rather than being sure it was something they wanted to do.

“We need to learn from the mistakes made with people like Keira Bell. , especially when [children are] ... young and especially when they’re traumatized,” Ms. O’Malley said.

“Had they received a more conventional therapy, they might have thought about their decision from different perspectives and in the process acquired more self-awareness, which would have been more beneficial.”

“The ‘affirmative’ approach to gender therapy is too narrow; we need to look at the whole individual. Therapy in other areas would never disregard other, nongender issues such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or anxiety [which often co-exist with gender dysphoria] – issues bleed into each other,” Ms. O’Malley pointed out. “We need a more exploratory approach.”

“I’d also like to see other therapists all over the [U.K.] who are perfectly qualified and capable of working with gender actually start working with gender issues,” she said, noting that such an approach might also help reduce the long waiting list at the Tavistock.

The latter had been overwhelmed, and this led to a speeding up of the assessment process, which led to a number of professionals resigning from the service in recent years, saying children were being “fast-tracked” to medical transition.

Fertility and sexual function are complex issues for kids

Also asked to comment was Claire Graham, from Genspect, a group that describes itself as a voice for parents of gender-questioning kids.

She told this news organization that “parents are rightly concerned about their children’s ability to consent to treatments that may lead to infertility and issues surrounding sexual function.” She added that other countries in Europe were changing their approach. “Look to Sweden and Finland, who have both rowed back on puberty blockers and no longer recommend them.”

Ms. Graham, who has worked with children with differences in sexual development, added that it was very difficult for children and young people to understand the life-long implications of decisions made at an early age.

“How can children understand what it is to live with impaired sexual functioning if they have never had sex? Likewise, fertility is a complex issue. Most people do not want to become parents as teenagers, but we understand that this will often change as they grow,” said Ms. Graham.

“Many parents worry that their child is not being considered in the whole [and] that their child’s ability to consent to medical interventions for gender dysphoria is impacted by comorbidities, such as a diagnosis of autism or a history of mental health issues. These children are particularly vulnerable.”

“At Genspect, we hope that the decision from the ... court is upheld,” Ms. Graham concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

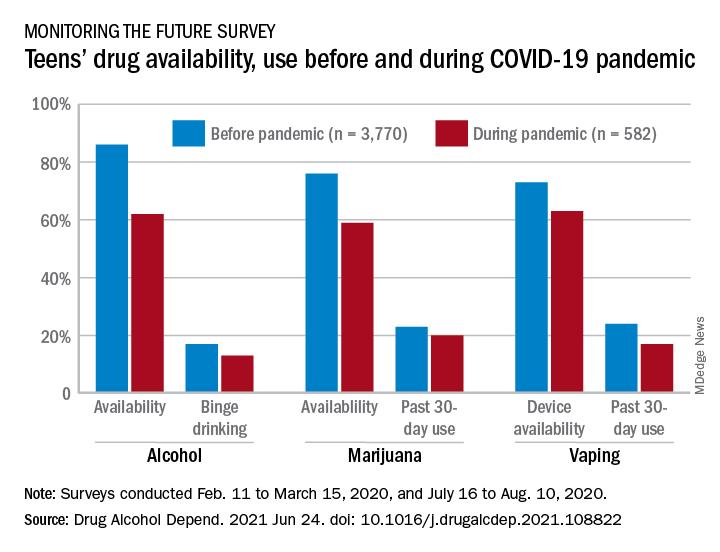

Even a pandemic can’t stop teens’ alcohol and marijuana use

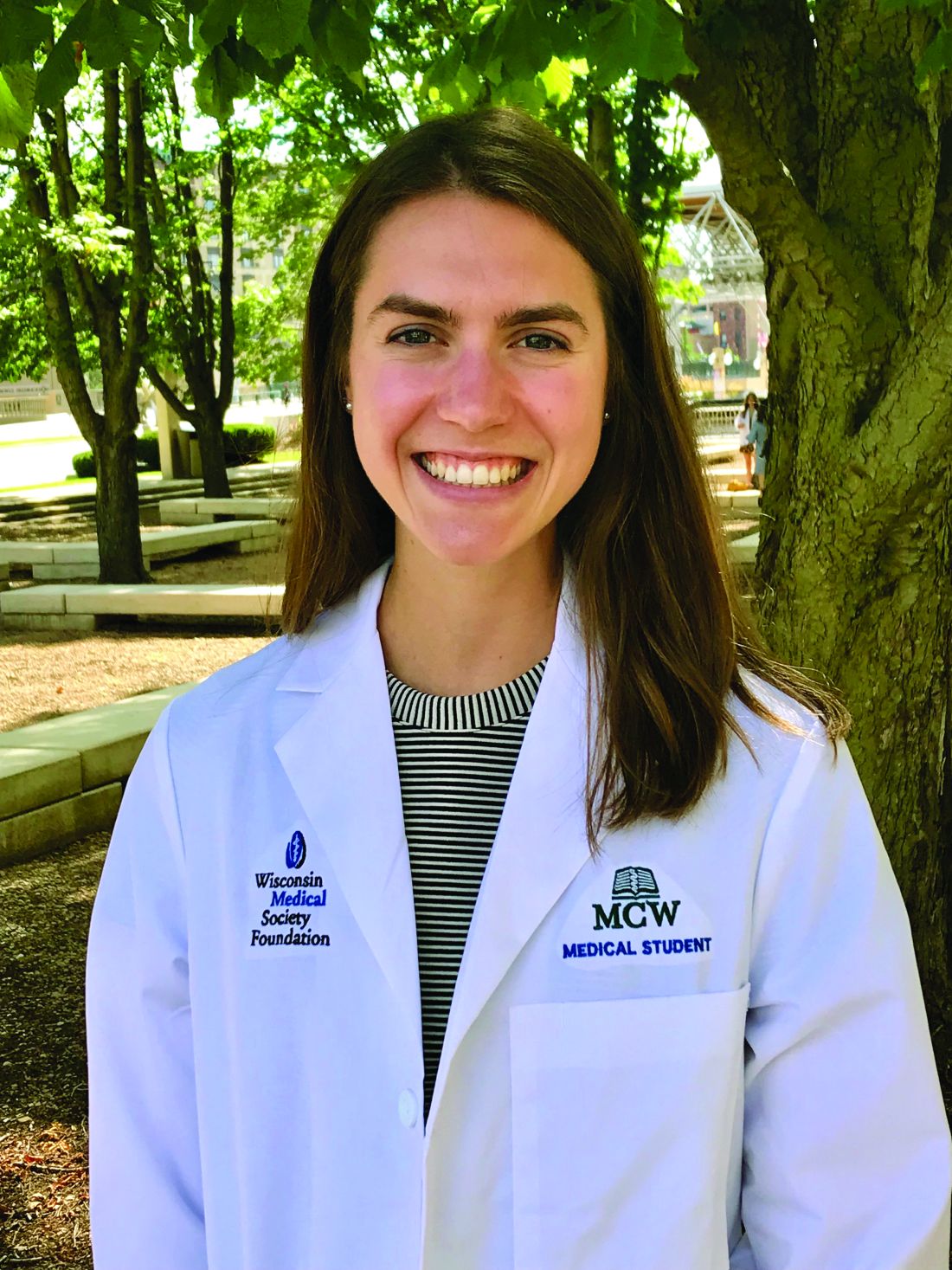

Despite record-breaking decreases in perceived availability of alcohol and marijuana among 12th-grade students, their use of these substances did not change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to two surveys conducted in 2020.

Vaping, however, did not show the same pattern. A decline in use over the previous 30 days was seen between the two surveys – conducted from Feb. 11 to March 15 and July 16 to Aug. 10 – along with a perceived reduction in the supply of vaping devices, Richard A. Miech, PhD, and associates said in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

“Last year brought dramatic changes to adolescents’ lives, as many teens remained home with parents and other family members full time,” Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said in a separate written statement. “It is striking that, despite this monumental shift and teens’ perceived decreases in availability of marijuana and alcohol, usage rates held steady for these substances. This indicates that teens were able to obtain them despite barriers caused by the pandemic and despite not being of age to legally purchase them.”

In the first poll, conducted as part of the Monitoring the Future survey largely before the national emergency was declared, 86% of 12th-graders said that it was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get alcohol, but that dropped to 62% in the second survey. For marijuana, prevalence of that level of availability was 76% before and 59% during the pandemic, Dr. Miech of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associates reported.

These results “indicate the largest decreases in substance use availability ever recorded in the 46 consecutive years it has been monitored by Monitoring the Future,” the investigators wrote.

The prevalence of marijuana use in the past 30 days declined from 23% before the pandemic to 20% during, with the respective figures for binge drinking in the past 2 weeks at 17% and 13%, and neither of those reductions reached significance, they noted.

“Adolescents may redouble their substance procurement efforts so that they can continue using substances at the levels at which they used in the past. In addition, adolescents may move to more solitary substance use. Social distancing policies might even increase substance use to the extent that they lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness that some adolescents address through increased substance use,” they suggested.

This hypothesis does not apply to vaping. The significant decline in availability – 73% before and 63% during – was accompanied by a significant drop in prevalence of past 30-day use from 24% to 17%, based on the survey data, which came from 3,770 responses to the first poll and 582 to the second.

In the case of vaping, the decline in use may have been caused by the decreased “exposure to substance-using peer networks ... and adults who provide opportunities for youth to initiate and continue use of substances,” Dr. Miech and associates said.

The findings of this analysis “suggest that reducing adolescent substance use through attempts to restrict supply alone would be a difficult undertaking,” Dr. Miech said in the NIDA statement. “The best strategy is likely to be one that combines approaches to limit the supply of these substances with efforts to decrease demand, through educational and public health campaigns.”

The research was funded by a NIDA grant. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

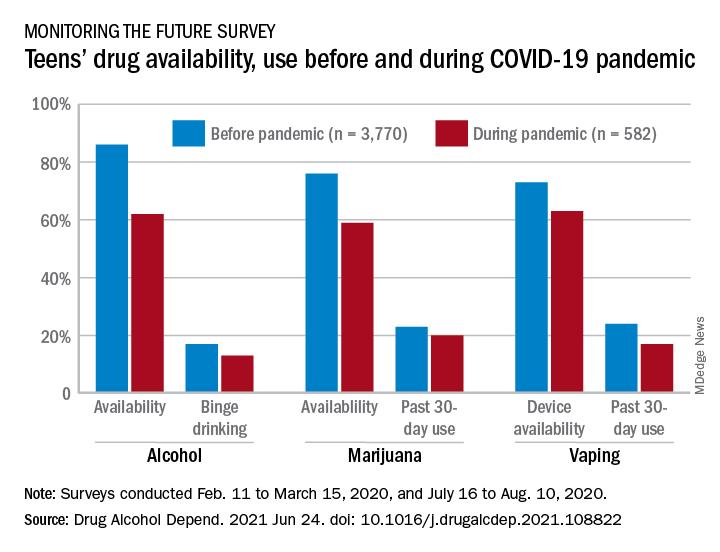

Despite record-breaking decreases in perceived availability of alcohol and marijuana among 12th-grade students, their use of these substances did not change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to two surveys conducted in 2020.

Vaping, however, did not show the same pattern. A decline in use over the previous 30 days was seen between the two surveys – conducted from Feb. 11 to March 15 and July 16 to Aug. 10 – along with a perceived reduction in the supply of vaping devices, Richard A. Miech, PhD, and associates said in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

“Last year brought dramatic changes to adolescents’ lives, as many teens remained home with parents and other family members full time,” Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said in a separate written statement. “It is striking that, despite this monumental shift and teens’ perceived decreases in availability of marijuana and alcohol, usage rates held steady for these substances. This indicates that teens were able to obtain them despite barriers caused by the pandemic and despite not being of age to legally purchase them.”

In the first poll, conducted as part of the Monitoring the Future survey largely before the national emergency was declared, 86% of 12th-graders said that it was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get alcohol, but that dropped to 62% in the second survey. For marijuana, prevalence of that level of availability was 76% before and 59% during the pandemic, Dr. Miech of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associates reported.

These results “indicate the largest decreases in substance use availability ever recorded in the 46 consecutive years it has been monitored by Monitoring the Future,” the investigators wrote.

The prevalence of marijuana use in the past 30 days declined from 23% before the pandemic to 20% during, with the respective figures for binge drinking in the past 2 weeks at 17% and 13%, and neither of those reductions reached significance, they noted.

“Adolescents may redouble their substance procurement efforts so that they can continue using substances at the levels at which they used in the past. In addition, adolescents may move to more solitary substance use. Social distancing policies might even increase substance use to the extent that they lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness that some adolescents address through increased substance use,” they suggested.

This hypothesis does not apply to vaping. The significant decline in availability – 73% before and 63% during – was accompanied by a significant drop in prevalence of past 30-day use from 24% to 17%, based on the survey data, which came from 3,770 responses to the first poll and 582 to the second.

In the case of vaping, the decline in use may have been caused by the decreased “exposure to substance-using peer networks ... and adults who provide opportunities for youth to initiate and continue use of substances,” Dr. Miech and associates said.

The findings of this analysis “suggest that reducing adolescent substance use through attempts to restrict supply alone would be a difficult undertaking,” Dr. Miech said in the NIDA statement. “The best strategy is likely to be one that combines approaches to limit the supply of these substances with efforts to decrease demand, through educational and public health campaigns.”

The research was funded by a NIDA grant. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

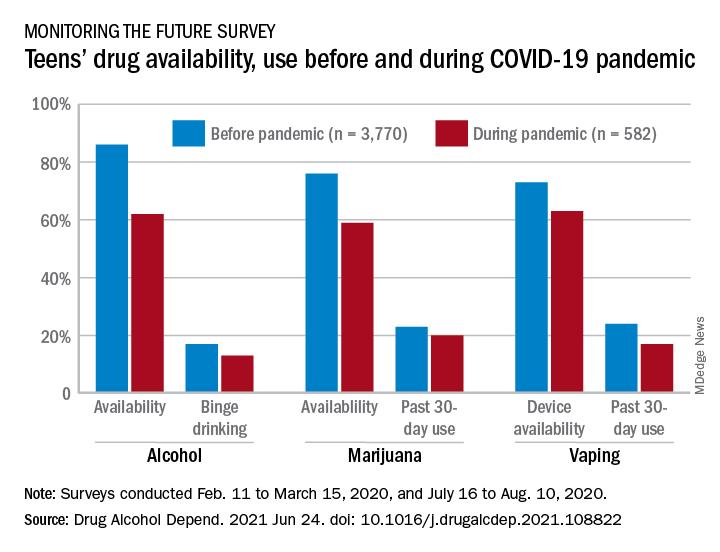

Despite record-breaking decreases in perceived availability of alcohol and marijuana among 12th-grade students, their use of these substances did not change significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to two surveys conducted in 2020.

Vaping, however, did not show the same pattern. A decline in use over the previous 30 days was seen between the two surveys – conducted from Feb. 11 to March 15 and July 16 to Aug. 10 – along with a perceived reduction in the supply of vaping devices, Richard A. Miech, PhD, and associates said in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

“Last year brought dramatic changes to adolescents’ lives, as many teens remained home with parents and other family members full time,” Nora D. Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said in a separate written statement. “It is striking that, despite this monumental shift and teens’ perceived decreases in availability of marijuana and alcohol, usage rates held steady for these substances. This indicates that teens were able to obtain them despite barriers caused by the pandemic and despite not being of age to legally purchase them.”

In the first poll, conducted as part of the Monitoring the Future survey largely before the national emergency was declared, 86% of 12th-graders said that it was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to get alcohol, but that dropped to 62% in the second survey. For marijuana, prevalence of that level of availability was 76% before and 59% during the pandemic, Dr. Miech of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associates reported.

These results “indicate the largest decreases in substance use availability ever recorded in the 46 consecutive years it has been monitored by Monitoring the Future,” the investigators wrote.

The prevalence of marijuana use in the past 30 days declined from 23% before the pandemic to 20% during, with the respective figures for binge drinking in the past 2 weeks at 17% and 13%, and neither of those reductions reached significance, they noted.

“Adolescents may redouble their substance procurement efforts so that they can continue using substances at the levels at which they used in the past. In addition, adolescents may move to more solitary substance use. Social distancing policies might even increase substance use to the extent that they lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness that some adolescents address through increased substance use,” they suggested.

This hypothesis does not apply to vaping. The significant decline in availability – 73% before and 63% during – was accompanied by a significant drop in prevalence of past 30-day use from 24% to 17%, based on the survey data, which came from 3,770 responses to the first poll and 582 to the second.

In the case of vaping, the decline in use may have been caused by the decreased “exposure to substance-using peer networks ... and adults who provide opportunities for youth to initiate and continue use of substances,” Dr. Miech and associates said.

The findings of this analysis “suggest that reducing adolescent substance use through attempts to restrict supply alone would be a difficult undertaking,” Dr. Miech said in the NIDA statement. “The best strategy is likely to be one that combines approaches to limit the supply of these substances with efforts to decrease demand, through educational and public health campaigns.”

The research was funded by a NIDA grant. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

FROM DRUG AND ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE

Cannabis use tied to increased risk for suicidal thoughts, actions

Young adults who use cannabis – either sporadically, daily, or those who have cannabis use disorder – have a significantly increased risk for suicidal thoughts and actions, according to U.S. national drug survey data.

The risks appear greater for women than men and remained regardless of whether the individual was depressed.

“We cannot establish that cannabis use caused increased suicidality,” Nora Volkow, MD, director, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), told this news organization.

“However, it is likely that these two factors influence one another bidirectionally, meaning people with suicidal thinking might be more vulnerable to cannabis use to self-medicate their distress, and cannabis use may trigger negative moods and suicidal thinking in some people,” said Dr. Volkow.

“It is also possible that these factors are not causally linked to one another at all but rather reflect the common and related risk factors underlying both suicidality and substance use. For instance, one’s genetics may put them at a higher risk for both suicide and for using marijuana,” she added.

The study was published online June 22 in JAMA Network Open.

Marked increase in use

Cannabis use among U.S. adults has increased markedly over the past 10 years, with a parallel increase in suicidality. However, the links between cannabis use and suicidality among young adults are poorly understood.

NIDA researchers sought to fill this gap. They examined data on 281,650 young men and women aged 18 to 34 years who participated in National Surveys on Drug Use and Health from 2008 to 2019.

Status regarding past-year cannabis use was categorized as past-year daily or near-daily use (greater than or equal to 300 days), non-daily use, and no cannabis use.

Although suicidality was associated with cannabis use, even young adults who did not use cannabis on a daily basis were more likely to have suicidal thoughts or actions than those who did not use the drug at all, the researchers found.

Among young adults without a major depressive episode, about 3% of those who did not use cannabis had suicidal ideation, compared with about 7% of non-daily cannabis users, about 9% of daily cannabis users, and 14% of those with a cannabis use disorder.

Among young adults with depression, the corresponding percentages were 35%, 44%, 53%, and 50%.

Similar trends existed for the associations between the different levels of cannabis use and suicide plan or attempt.

Women at greatest risk

Gender differences also emerged. than men with the same levels of cannabis use.

Among those without a major depressive episode, the prevalence of suicidal ideation for those with versus without a cannabis use disorder was around 14% versus 4.0% among women and 10% versus 3.0% among men.

Among young adults with both cannabis use disorder and major depressive episode, the prevalence of past-year suicide plan was 52% higher for women (24%) than for men (16%).

“Suicide is a leading cause of death among young adults in the United States, and the findings of this study offer important information that may help us reduce this risk,” lead author and NIDA researcher Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH, said in a news release.

“Depression and cannabis use disorder are treatable conditions, and cannabis use can be modified. Through better understanding the associations of different risk factors for suicidality, we hope to offer new targets for prevention and intervention in individuals that we know may be at high risk. These findings also underscore the importance of tailoring interventions in a way that takes sex and gender into account,” said Dr. Han.

“Additional research is needed to better understand these complex associations, especially given the great burden of suicide on young adults,” said Dr. Volkow.

Gender difference ‘striking’

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, said this study is “clearly of great interest; of course correlation and causality are completely distinct entities, and this study is all about correlation.

“This does not, of course, mean that cannabis use causes suicide but suggests that in individuals who use cannabis, suicidality in the broadest sense is increased in prevalence rate,” said Dr. Nemeroff, who serves as principal investigator of the Texas Child Trauma Network.

Dr. Nemeroff said “the most striking finding” was the larger effect in women than men – “striking because suicide is, in almost all cultures, higher in prevalence in men versus women.”

Dr. Nemeroff said he’d like to know more about other potential contributing factors, “which would include a history of child abuse and neglect, a major vulnerability factor for suicidality, comorbid alcohol and other substance abuse, [and] comorbid psychiatric diagnosis such as posttraumatic stress disorder.”

The study was sponsored by NIDA, of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkow, Dr. Han, and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young adults who use cannabis – either sporadically, daily, or those who have cannabis use disorder – have a significantly increased risk for suicidal thoughts and actions, according to U.S. national drug survey data.

The risks appear greater for women than men and remained regardless of whether the individual was depressed.

“We cannot establish that cannabis use caused increased suicidality,” Nora Volkow, MD, director, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), told this news organization.

“However, it is likely that these two factors influence one another bidirectionally, meaning people with suicidal thinking might be more vulnerable to cannabis use to self-medicate their distress, and cannabis use may trigger negative moods and suicidal thinking in some people,” said Dr. Volkow.

“It is also possible that these factors are not causally linked to one another at all but rather reflect the common and related risk factors underlying both suicidality and substance use. For instance, one’s genetics may put them at a higher risk for both suicide and for using marijuana,” she added.

The study was published online June 22 in JAMA Network Open.

Marked increase in use

Cannabis use among U.S. adults has increased markedly over the past 10 years, with a parallel increase in suicidality. However, the links between cannabis use and suicidality among young adults are poorly understood.

NIDA researchers sought to fill this gap. They examined data on 281,650 young men and women aged 18 to 34 years who participated in National Surveys on Drug Use and Health from 2008 to 2019.

Status regarding past-year cannabis use was categorized as past-year daily or near-daily use (greater than or equal to 300 days), non-daily use, and no cannabis use.

Although suicidality was associated with cannabis use, even young adults who did not use cannabis on a daily basis were more likely to have suicidal thoughts or actions than those who did not use the drug at all, the researchers found.

Among young adults without a major depressive episode, about 3% of those who did not use cannabis had suicidal ideation, compared with about 7% of non-daily cannabis users, about 9% of daily cannabis users, and 14% of those with a cannabis use disorder.

Among young adults with depression, the corresponding percentages were 35%, 44%, 53%, and 50%.

Similar trends existed for the associations between the different levels of cannabis use and suicide plan or attempt.

Women at greatest risk

Gender differences also emerged. than men with the same levels of cannabis use.

Among those without a major depressive episode, the prevalence of suicidal ideation for those with versus without a cannabis use disorder was around 14% versus 4.0% among women and 10% versus 3.0% among men.

Among young adults with both cannabis use disorder and major depressive episode, the prevalence of past-year suicide plan was 52% higher for women (24%) than for men (16%).

“Suicide is a leading cause of death among young adults in the United States, and the findings of this study offer important information that may help us reduce this risk,” lead author and NIDA researcher Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH, said in a news release.

“Depression and cannabis use disorder are treatable conditions, and cannabis use can be modified. Through better understanding the associations of different risk factors for suicidality, we hope to offer new targets for prevention and intervention in individuals that we know may be at high risk. These findings also underscore the importance of tailoring interventions in a way that takes sex and gender into account,” said Dr. Han.

“Additional research is needed to better understand these complex associations, especially given the great burden of suicide on young adults,” said Dr. Volkow.

Gender difference ‘striking’

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, said this study is “clearly of great interest; of course correlation and causality are completely distinct entities, and this study is all about correlation.

“This does not, of course, mean that cannabis use causes suicide but suggests that in individuals who use cannabis, suicidality in the broadest sense is increased in prevalence rate,” said Dr. Nemeroff, who serves as principal investigator of the Texas Child Trauma Network.

Dr. Nemeroff said “the most striking finding” was the larger effect in women than men – “striking because suicide is, in almost all cultures, higher in prevalence in men versus women.”

Dr. Nemeroff said he’d like to know more about other potential contributing factors, “which would include a history of child abuse and neglect, a major vulnerability factor for suicidality, comorbid alcohol and other substance abuse, [and] comorbid psychiatric diagnosis such as posttraumatic stress disorder.”

The study was sponsored by NIDA, of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkow, Dr. Han, and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young adults who use cannabis – either sporadically, daily, or those who have cannabis use disorder – have a significantly increased risk for suicidal thoughts and actions, according to U.S. national drug survey data.

The risks appear greater for women than men and remained regardless of whether the individual was depressed.

“We cannot establish that cannabis use caused increased suicidality,” Nora Volkow, MD, director, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), told this news organization.

“However, it is likely that these two factors influence one another bidirectionally, meaning people with suicidal thinking might be more vulnerable to cannabis use to self-medicate their distress, and cannabis use may trigger negative moods and suicidal thinking in some people,” said Dr. Volkow.

“It is also possible that these factors are not causally linked to one another at all but rather reflect the common and related risk factors underlying both suicidality and substance use. For instance, one’s genetics may put them at a higher risk for both suicide and for using marijuana,” she added.

The study was published online June 22 in JAMA Network Open.

Marked increase in use

Cannabis use among U.S. adults has increased markedly over the past 10 years, with a parallel increase in suicidality. However, the links between cannabis use and suicidality among young adults are poorly understood.

NIDA researchers sought to fill this gap. They examined data on 281,650 young men and women aged 18 to 34 years who participated in National Surveys on Drug Use and Health from 2008 to 2019.

Status regarding past-year cannabis use was categorized as past-year daily or near-daily use (greater than or equal to 300 days), non-daily use, and no cannabis use.

Although suicidality was associated with cannabis use, even young adults who did not use cannabis on a daily basis were more likely to have suicidal thoughts or actions than those who did not use the drug at all, the researchers found.

Among young adults without a major depressive episode, about 3% of those who did not use cannabis had suicidal ideation, compared with about 7% of non-daily cannabis users, about 9% of daily cannabis users, and 14% of those with a cannabis use disorder.

Among young adults with depression, the corresponding percentages were 35%, 44%, 53%, and 50%.

Similar trends existed for the associations between the different levels of cannabis use and suicide plan or attempt.

Women at greatest risk

Gender differences also emerged. than men with the same levels of cannabis use.

Among those without a major depressive episode, the prevalence of suicidal ideation for those with versus without a cannabis use disorder was around 14% versus 4.0% among women and 10% versus 3.0% among men.

Among young adults with both cannabis use disorder and major depressive episode, the prevalence of past-year suicide plan was 52% higher for women (24%) than for men (16%).

“Suicide is a leading cause of death among young adults in the United States, and the findings of this study offer important information that may help us reduce this risk,” lead author and NIDA researcher Beth Han, MD, PhD, MPH, said in a news release.

“Depression and cannabis use disorder are treatable conditions, and cannabis use can be modified. Through better understanding the associations of different risk factors for suicidality, we hope to offer new targets for prevention and intervention in individuals that we know may be at high risk. These findings also underscore the importance of tailoring interventions in a way that takes sex and gender into account,” said Dr. Han.

“Additional research is needed to better understand these complex associations, especially given the great burden of suicide on young adults,” said Dr. Volkow.

Gender difference ‘striking’

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Charles B. Nemeroff, MD, PhD, professor and chair, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, said this study is “clearly of great interest; of course correlation and causality are completely distinct entities, and this study is all about correlation.

“This does not, of course, mean that cannabis use causes suicide but suggests that in individuals who use cannabis, suicidality in the broadest sense is increased in prevalence rate,” said Dr. Nemeroff, who serves as principal investigator of the Texas Child Trauma Network.

Dr. Nemeroff said “the most striking finding” was the larger effect in women than men – “striking because suicide is, in almost all cultures, higher in prevalence in men versus women.”

Dr. Nemeroff said he’d like to know more about other potential contributing factors, “which would include a history of child abuse and neglect, a major vulnerability factor for suicidality, comorbid alcohol and other substance abuse, [and] comorbid psychiatric diagnosis such as posttraumatic stress disorder.”

The study was sponsored by NIDA, of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkow, Dr. Han, and Dr. Nemeroff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dose-dependent effect of ‘internet addiction’ and sleep problems

More evidence suggests the severity of internet addiction (IA) is directly related to the severity of sleep problems in youth.

Results from a study of more than 4,000 adolescent students show IA severity was linked to less sleep and to daytime sleepiness. In addition, boys aged 12-14 years who were addicted to computer games versus social media networking were the most affected.

Sleep issues could be “easily detectable manifestations of pathological internet addiction,” investigator Sergey Tereshchenko, PhD, Scientific Research Institute for Medical Problems of the North, Krasnoyask State Medical University, Russia, told this news organization.

These sleep problems require attention and correction, Dr. Tereshchenko added.

The findings were presented at the virtual Congress of the European Academy of Neurology 2021.

New phenomenon

IA is a relatively new psychological phenomenon and is most prevalent in “socially vulnerable groups,” such as adolescents, Dr. Tereshchenko said.

He cited numerous studies that have “convincingly demonstrated” IA is comorbid with a broad range of psychopathologic conditions, including depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

There is also growing evidence, including from systematic reviews in 2014 and 2019, that IA affects a wide range of sleep parameters.

However, most studies in adolescents have used only one psychometric tool to assess addiction, revealing only the “general IA pattern” and not the type of IA, Dr. Tereshchenko noted.

Adolescents may not be addicted to the internet itself but to certain behaviors like gaming or social networking, he said.

The “undoubted advantage” of his team’s research is the use of more than one tool, making it possible to “verify the predominant content of the addiction,” he added.

The investigators previously assessed general prevalence of IA in adolescents in Siberia and found about 6.8% of participants displayed pathological IA behavior – and that gaming addiction is more common in boys whereas addiction to social networking is more common in girls.

This prevalence rate is lower than in the Philippines (21.1%), Hong Kong (16.4%), Malaysia (14.1%), China (11%), and South Korea (9.7%), but slightly higher than in Japan (6.2%).

IA prevalence among adolescents in Europe ranges from 1% to 11%, with an average of 4.4%, said Dr. Tereshchenko.

Siberian students’ sleep

The current study included 4,344 students aged 12-18 years (average age, about 15 years) from 10 public schools in three large cities of Central Siberia (Krasnoyarsk, Abakan, and Kyzyl). There were slightly more girls than boys in the study sample.

Participants completed the Russian language version of the Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS), which covers five symptomatic criteria for addictive behavior: withdrawal symptoms, signs of tolerance, compulsive use, psychological or physical problems, and difficulty managing time.

In this questionnaire, respondents rate several statements regarding the effect of internet use, each on a 4-point Likert scale: not at all (1 point), a little bit (2 points), moderately (3 points) and extremely (4). The total score ranges from 26 to 104.

A CIAS score of 26-42 indicates adaptive internet use, 43-64 indicates maladaptive internet use, and 65 and above indicates pathological internet use (PIU), which was classified as “internet-addicted.”

The researchers also used the nine-item Social Media Disorder Scale, as well as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to assess nighttime sleep.

Among other questions, teens were asked how long it usually took them to fall asleep and when they typically went to bed and woke up on school nights.

For daytime sleepiness, investigators used the targeted Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale questionnaire, making them among the few research groups to use this psychometric instrument, Dr. Tereshchenko noted.

After parental consent was given, students completed the tests at the end of the day’s lessons. Total test time was about 45 minutes.

Sleep disturbance

Initial study results showed that compared with the other groups, adolescents with PIU tended to go to bed later, wake up later, take longer to fall asleep, sleep less at night, have more nighttime awakenings, and have more daytime sleepiness.

Sleep quality was the most impaired in boys aged 12-14 years who are addicted to internet computer games.

“In this group, 5 of the 6 sleep assessment parameters we studied were changed,” Dr. Tereshchenko reported.

Decreased total nighttime sleep was more common in older adolescents.

On average, boys and girls aged 15-18 years got less than the recommended 8 hours of sleep per night. Boys with IA got only about 6.4 hours per night and girls with IA got about 6.6 hours.

Interestingly, IA is generally more prevalent among teen girls than boys in Russia, which is not the case in Europe and North America, Dr. Tereshchenko noted.

Mechanisms linking IA and sleep disorders are not clear, but the relationship is probably multifactorial and perhaps interrelated, creating something of a “vicious circle,” he said.

“Sleep disturbances, which reflect psychosocial problems, depression, and anxiety-phobic disorders, can precede and contribute to IA. On the other hand, sleep disturbances such as insomnia can lead to increased use of the internet in the evening and at night, further exacerbating the problem,” said Dr. Tereshchenko.

Research is lacking on useful treatments for youth with IA, but these kids would likely benefit from behavioral therapy approaches, he added.

No escape?

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Maurice M. Ohayon, MD, DSc, PhD, director of the Stanford Sleep Epidemiology Research Center, Stanford University, California, said the topic of youth IA is “very important.”

Previous research in this field has shown a major impact from IA not only on sleep but also on mood – with irritability, depression, and even thoughts of suicide being possible red flags, said Dr. Ohayon, who was not involved in the current study.

Interestingly, his own research has also found that young teenage boys are most at risk for gaming addiction.

Although internet gaming has some positive effects, such as fostering leadership skills and relationships, it has become increasingly violent and isolating, with more adult professional gamers preying on younger players, Dr. Ohayon said.

“The major problem is that it’s putting children in a virtual world from which it’s difficult to escape,” he added.

Dr. Ohayon also noted concern about future developmental effects in kids who play video games for hours on end without coming out of their bedroom and with no physical contact with fellow players.

Parents should intervene before this situation occurs and limit the time their children spend on the gaming console, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More evidence suggests the severity of internet addiction (IA) is directly related to the severity of sleep problems in youth.

Results from a study of more than 4,000 adolescent students show IA severity was linked to less sleep and to daytime sleepiness. In addition, boys aged 12-14 years who were addicted to computer games versus social media networking were the most affected.

Sleep issues could be “easily detectable manifestations of pathological internet addiction,” investigator Sergey Tereshchenko, PhD, Scientific Research Institute for Medical Problems of the North, Krasnoyask State Medical University, Russia, told this news organization.

These sleep problems require attention and correction, Dr. Tereshchenko added.

The findings were presented at the virtual Congress of the European Academy of Neurology 2021.

New phenomenon

IA is a relatively new psychological phenomenon and is most prevalent in “socially vulnerable groups,” such as adolescents, Dr. Tereshchenko said.

He cited numerous studies that have “convincingly demonstrated” IA is comorbid with a broad range of psychopathologic conditions, including depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.