User login

Merino wool clothing improves atopic dermatitis, studies find

Conventional wisdom holds that Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually.

“We’ve always though that wool is bad in atopics, right? Indeed, rough wool might be. But fine wool garments can actually improve atopic dermatitis, probably because wool is the most breathable fabric and has the best temperature regulation qualities of any fabric we can wear,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky).

He was first author of a randomized, 12-week, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial which showed precisely that. And a second, similarly designed study, this one conducted in Australia, also concluded that fine merino wool assists in the management of AD.

The study by Dr. Fowler and coinvestigators included 50 children and adults with mild or moderate AD who either wore top-and-bottom base layer merino wool ensembles for 6 weeks and then switched to their regular nonwoolen clothing, or vice versa. The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in those initially randomized to merino wool improved from a mean baseline of 4.5 to 1.7 at week 6, a significantly greater improvement than in the group wearing their regular clothing. Similarly, those who switched to merino wool after 6 weeks experienced a significant decrease in EASI scores from that point on to week 12, while those who switched from merino wool to their regular clothing did not.

Mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores in patients who wore merino wool first improved from 6.9 at baseline to 3.4 at week 6. Those who wore their regular clothing first went from a mean baseline DLQI of 6.7 to 6.2 at week 6 – a nonsignificant change – but then improved to a week 12 mean DLQI of 3.7 while wearing wool. There was no improvement in DLQI scores while participants were wearing their regular clothing.

Static Investigator’s Global Assessment scores showed significantly greater improvement while patients wore merino wool garments than their regular clothing.

The Australian study included 39 patients with mild to moderate AD aged between 4 weeks and 3 years. This, too, was a 12-week, randomized, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Participating children wore merino wool for 6 weeks and cotton ensembles chosen by their parents for an equal time. The primary endpoint was change in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index after each 6-week period. The mean 7.6-point greater SCORAD reduction at 6 weeks while wearing merino wool, compared with cotton, was “a pretty impressive reduction,” Dr. Fowler observed.

Reductions in the secondary endpoints of Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index while wearing merino wool followed suit. In contrast, switching from wool to cotton resulted in an increase in both scores. Also, use of topical corticosteroids was significantly reduced while patients wore merino wool.

Wool harvested from merino sheep is characterized by fine-diameter fibers. In Dr. Fowler’s study the mean fiber diameter was 17.5 mcm. This makes for a soft fabric with outstanding moisture absorbance capacity, a quality that’s beneficial in patients with AD, since their lesional skin loses the ability to regulate moisture, the dermatologist explained.

Both randomized trials were funded by Australian Wool Innovation and the Australian government.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Conventional wisdom holds that Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually.

“We’ve always though that wool is bad in atopics, right? Indeed, rough wool might be. But fine wool garments can actually improve atopic dermatitis, probably because wool is the most breathable fabric and has the best temperature regulation qualities of any fabric we can wear,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky).

He was first author of a randomized, 12-week, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial which showed precisely that. And a second, similarly designed study, this one conducted in Australia, also concluded that fine merino wool assists in the management of AD.

The study by Dr. Fowler and coinvestigators included 50 children and adults with mild or moderate AD who either wore top-and-bottom base layer merino wool ensembles for 6 weeks and then switched to their regular nonwoolen clothing, or vice versa. The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in those initially randomized to merino wool improved from a mean baseline of 4.5 to 1.7 at week 6, a significantly greater improvement than in the group wearing their regular clothing. Similarly, those who switched to merino wool after 6 weeks experienced a significant decrease in EASI scores from that point on to week 12, while those who switched from merino wool to their regular clothing did not.

Mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores in patients who wore merino wool first improved from 6.9 at baseline to 3.4 at week 6. Those who wore their regular clothing first went from a mean baseline DLQI of 6.7 to 6.2 at week 6 – a nonsignificant change – but then improved to a week 12 mean DLQI of 3.7 while wearing wool. There was no improvement in DLQI scores while participants were wearing their regular clothing.

Static Investigator’s Global Assessment scores showed significantly greater improvement while patients wore merino wool garments than their regular clothing.

The Australian study included 39 patients with mild to moderate AD aged between 4 weeks and 3 years. This, too, was a 12-week, randomized, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Participating children wore merino wool for 6 weeks and cotton ensembles chosen by their parents for an equal time. The primary endpoint was change in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index after each 6-week period. The mean 7.6-point greater SCORAD reduction at 6 weeks while wearing merino wool, compared with cotton, was “a pretty impressive reduction,” Dr. Fowler observed.

Reductions in the secondary endpoints of Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index while wearing merino wool followed suit. In contrast, switching from wool to cotton resulted in an increase in both scores. Also, use of topical corticosteroids was significantly reduced while patients wore merino wool.

Wool harvested from merino sheep is characterized by fine-diameter fibers. In Dr. Fowler’s study the mean fiber diameter was 17.5 mcm. This makes for a soft fabric with outstanding moisture absorbance capacity, a quality that’s beneficial in patients with AD, since their lesional skin loses the ability to regulate moisture, the dermatologist explained.

Both randomized trials were funded by Australian Wool Innovation and the Australian government.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Conventional wisdom holds that Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually.

“We’ve always though that wool is bad in atopics, right? Indeed, rough wool might be. But fine wool garments can actually improve atopic dermatitis, probably because wool is the most breathable fabric and has the best temperature regulation qualities of any fabric we can wear,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky).

He was first author of a randomized, 12-week, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial which showed precisely that. And a second, similarly designed study, this one conducted in Australia, also concluded that fine merino wool assists in the management of AD.

The study by Dr. Fowler and coinvestigators included 50 children and adults with mild or moderate AD who either wore top-and-bottom base layer merino wool ensembles for 6 weeks and then switched to their regular nonwoolen clothing, or vice versa. The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score in those initially randomized to merino wool improved from a mean baseline of 4.5 to 1.7 at week 6, a significantly greater improvement than in the group wearing their regular clothing. Similarly, those who switched to merino wool after 6 weeks experienced a significant decrease in EASI scores from that point on to week 12, while those who switched from merino wool to their regular clothing did not.

Mean Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores in patients who wore merino wool first improved from 6.9 at baseline to 3.4 at week 6. Those who wore their regular clothing first went from a mean baseline DLQI of 6.7 to 6.2 at week 6 – a nonsignificant change – but then improved to a week 12 mean DLQI of 3.7 while wearing wool. There was no improvement in DLQI scores while participants were wearing their regular clothing.

Static Investigator’s Global Assessment scores showed significantly greater improvement while patients wore merino wool garments than their regular clothing.

The Australian study included 39 patients with mild to moderate AD aged between 4 weeks and 3 years. This, too, was a 12-week, randomized, crossover, assessor-blinded clinical trial. Participating children wore merino wool for 6 weeks and cotton ensembles chosen by their parents for an equal time. The primary endpoint was change in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index after each 6-week period. The mean 7.6-point greater SCORAD reduction at 6 weeks while wearing merino wool, compared with cotton, was “a pretty impressive reduction,” Dr. Fowler observed.

Reductions in the secondary endpoints of Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index and Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index while wearing merino wool followed suit. In contrast, switching from wool to cotton resulted in an increase in both scores. Also, use of topical corticosteroids was significantly reduced while patients wore merino wool.

Wool harvested from merino sheep is characterized by fine-diameter fibers. In Dr. Fowler’s study the mean fiber diameter was 17.5 mcm. This makes for a soft fabric with outstanding moisture absorbance capacity, a quality that’s beneficial in patients with AD, since their lesional skin loses the ability to regulate moisture, the dermatologist explained.

Both randomized trials were funded by Australian Wool Innovation and the Australian government.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

‘Uptake is only the first step’ for effective HIV PrEP protection

To Amanda Allmacher, DNP, RN, nurse practitioner at the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic, that means that same-day PrEP prescribing works and is acceptable. But there’s more work to do on the clinic and pharmacy side to make HIV protection a reality for most of her patients. Allmacher presented her data at the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 virtual annual meeting.

Dawn K. Smith, MD, epidemiologist and medical officer in the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said this adds to other data to show that we’re now entering the next phase of PrEP implementation.

“Our original focus was on uptake — informing folks what PrEP is, why they might benefit from its use, and then prescribing it if accepted,” Smith told Medscape Medical News via email. “Whether standard or same-day [PrEP prescribing], it is clear that uptake is only the first step.”

Nurses help navigate

Patients who attended the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic are more likely to be younger, have no insurance, and otherwise “have little to no contact with the healthcare system,” Allmacher said in her presentation. They also tend to come from communities that bear the greatest burden of HIV in the US — in other words, they are often the people most missed in PrEP rollouts thus far.

In response, the clinic implemented a same-day PrEP protocol, in which registered nurses trained in HIV risk assessment identify clients who might most benefit from PrEP. Criteria often include the presence of other STIs. Once the nurse explains what PrEP is and how it works, if the patient is interested, clients meet with a nurse practitioner right then to get the prescription for PrEP. The clinic also does labs to rule out current HIV infection, hepatitis B, metabolic issues, and other STI screening.

But it doesn’t stop there. The clinic used grant funding to offer PrEP navigation and financial counseling services, which help clients navigate the sometimes-thorny process of paying for PrEP. Payment comes either through Medicaid, which in Michigan charges $3 a month for a PrEP prescription, through patient assistance programs, or through private insurance. With clients under age 18 who are interested in PrEP, the clinic works to find a way to access PrEP without having to inform their parents. These same navigators schedule follow-up appointments, offer appointment reminders, and contact clients when they miss an appointment.

“Our navigators and financial counselors are a huge support for our same-day PrEP starts, helping with financial assistance, prior authorization, navigating different plans, and helping patients apply for Medicaid when appropriate,” she said.

The clinic also offers community outreach and incentives, which can include gift cards, bus passes, and pill containers, among other things.

This was a key lesson in setting up the program, Allmacher told Medscape Medical News.

“Starting PrEP at that initial visit allows for clinicians to meet patients where they are and administer care in a more equitable manner,” Allmacher said via email. “Use all available resources and funding sources. We have a versatile team working together to increase access for patients and promote HIV prevention and risk reduction.”

Script vs. follow-up

This approach is common, used in places like New York City and San Francisco. So once it was set up Allmacher sat back and waited to see how the program helped clients protect themselves from HIV.

Of the 451 clients eligible for PrEP in 2019, 336 were gay and bisexual men, 6 were transgender women, 61 were heterosexual, cisgender men, and 48 were cisgender women. One transgender man also screened as eligible. Allmacher did not break down data by race.

Uptake was high: 70% of all eligible clients did receive a prescription for PrEP, either generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) or tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy). And uptake was high among people most at risk: 80% of gay and bisexual men who were eligible got a prescription, 60% of eligible cisgender women, 50% of the small number of transgender women, and 32.7% of heterosexual cisgender men did as well. The 1 transgender man also received a prescription.

This is a higher rate than found in a recent PrEP demonstration project, which found that despite gay and bisexual men, transgender adults, and Black people having the highest risk for HIV in the US, state health departments were more likely to refer heterosexual adults for PrEP.

That high uptake rate is encouraging, but follow-up? Not so much. After initial intake, clients are meant to return in a month to double-check their labs, ask about side effects, and start their 90-day supply of the medication. But just 40% showed up for their 30-day appointment, Allmacher said. And only one third of those showed up for the follow-up in 90 days.

By the end of 2019, just 73 of the original 451 clients screened were still taking PrEP.

“It was surprising to see just how significant the follow-up dropped off after that first visit, when the patient initially accepted the prescription,” Allmacher said.

And while it’s possible that some clients get their follow-up care from their primary care providers, “our clinic serves individuals regardless of insurance status and many do not identify having access to primary care for any type of service, PrEP or otherwise,” she said.

5 HIV acquisitions

In addition, the program review identified five clients who had been offered PrEP or had taken PrEP briefly who later acquired HIV. Those clients were offered same-day antiretroviral treatment, Allmacher said.

“So we’re finding people who are at high risk for HIV and we can prevent them, but we’re still not quite doing enough,” Allmacher said of those acquisitions. “Clearly we have a lot of work to do to focus on HIV prevention, and we are looking to create a more formal follow-up process” from the clinic’s side.

For instance, clinic staff call clients 1 week after their initial visit to share lab results. “This was identified as a missed opportunity for us to ask about their status, whether they filled their prescription, or if they need further assistance,” she said. “This is an area where our registered nurses are going to be taking on a greater role moving forward.”

Allmacher and team also discovered that, despite PrEP navigators arranging insurance coverage for clients on the day they receive their prescription, sometimes there were still barriers when the client showed up at the pharmacy to pick up their meds. The clinic does not have an in-house pharmacy and does not currently have the funding that would allow them to hand patients a bottle of the appropriate medication when they leave the clinic.

“Navigating the copays and the insurance coverage and using financial assistance through the drug manufacturer — even though we have the support in the clinic, it seems like there’s a disconnect between our clinic and getting to the pharmacy. Not every pharmacy is super familiar with navigating those,” she said. “So we have started to identify some area pharmacies near our clinic that are great at navigating these, and we really try to get our patients to go to places we know can give them assistance.”

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

To Amanda Allmacher, DNP, RN, nurse practitioner at the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic, that means that same-day PrEP prescribing works and is acceptable. But there’s more work to do on the clinic and pharmacy side to make HIV protection a reality for most of her patients. Allmacher presented her data at the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 virtual annual meeting.

Dawn K. Smith, MD, epidemiologist and medical officer in the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said this adds to other data to show that we’re now entering the next phase of PrEP implementation.

“Our original focus was on uptake — informing folks what PrEP is, why they might benefit from its use, and then prescribing it if accepted,” Smith told Medscape Medical News via email. “Whether standard or same-day [PrEP prescribing], it is clear that uptake is only the first step.”

Nurses help navigate

Patients who attended the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic are more likely to be younger, have no insurance, and otherwise “have little to no contact with the healthcare system,” Allmacher said in her presentation. They also tend to come from communities that bear the greatest burden of HIV in the US — in other words, they are often the people most missed in PrEP rollouts thus far.

In response, the clinic implemented a same-day PrEP protocol, in which registered nurses trained in HIV risk assessment identify clients who might most benefit from PrEP. Criteria often include the presence of other STIs. Once the nurse explains what PrEP is and how it works, if the patient is interested, clients meet with a nurse practitioner right then to get the prescription for PrEP. The clinic also does labs to rule out current HIV infection, hepatitis B, metabolic issues, and other STI screening.

But it doesn’t stop there. The clinic used grant funding to offer PrEP navigation and financial counseling services, which help clients navigate the sometimes-thorny process of paying for PrEP. Payment comes either through Medicaid, which in Michigan charges $3 a month for a PrEP prescription, through patient assistance programs, or through private insurance. With clients under age 18 who are interested in PrEP, the clinic works to find a way to access PrEP without having to inform their parents. These same navigators schedule follow-up appointments, offer appointment reminders, and contact clients when they miss an appointment.

“Our navigators and financial counselors are a huge support for our same-day PrEP starts, helping with financial assistance, prior authorization, navigating different plans, and helping patients apply for Medicaid when appropriate,” she said.

The clinic also offers community outreach and incentives, which can include gift cards, bus passes, and pill containers, among other things.

This was a key lesson in setting up the program, Allmacher told Medscape Medical News.

“Starting PrEP at that initial visit allows for clinicians to meet patients where they are and administer care in a more equitable manner,” Allmacher said via email. “Use all available resources and funding sources. We have a versatile team working together to increase access for patients and promote HIV prevention and risk reduction.”

Script vs. follow-up

This approach is common, used in places like New York City and San Francisco. So once it was set up Allmacher sat back and waited to see how the program helped clients protect themselves from HIV.

Of the 451 clients eligible for PrEP in 2019, 336 were gay and bisexual men, 6 were transgender women, 61 were heterosexual, cisgender men, and 48 were cisgender women. One transgender man also screened as eligible. Allmacher did not break down data by race.

Uptake was high: 70% of all eligible clients did receive a prescription for PrEP, either generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) or tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy). And uptake was high among people most at risk: 80% of gay and bisexual men who were eligible got a prescription, 60% of eligible cisgender women, 50% of the small number of transgender women, and 32.7% of heterosexual cisgender men did as well. The 1 transgender man also received a prescription.

This is a higher rate than found in a recent PrEP demonstration project, which found that despite gay and bisexual men, transgender adults, and Black people having the highest risk for HIV in the US, state health departments were more likely to refer heterosexual adults for PrEP.

That high uptake rate is encouraging, but follow-up? Not so much. After initial intake, clients are meant to return in a month to double-check their labs, ask about side effects, and start their 90-day supply of the medication. But just 40% showed up for their 30-day appointment, Allmacher said. And only one third of those showed up for the follow-up in 90 days.

By the end of 2019, just 73 of the original 451 clients screened were still taking PrEP.

“It was surprising to see just how significant the follow-up dropped off after that first visit, when the patient initially accepted the prescription,” Allmacher said.

And while it’s possible that some clients get their follow-up care from their primary care providers, “our clinic serves individuals regardless of insurance status and many do not identify having access to primary care for any type of service, PrEP or otherwise,” she said.

5 HIV acquisitions

In addition, the program review identified five clients who had been offered PrEP or had taken PrEP briefly who later acquired HIV. Those clients were offered same-day antiretroviral treatment, Allmacher said.

“So we’re finding people who are at high risk for HIV and we can prevent them, but we’re still not quite doing enough,” Allmacher said of those acquisitions. “Clearly we have a lot of work to do to focus on HIV prevention, and we are looking to create a more formal follow-up process” from the clinic’s side.

For instance, clinic staff call clients 1 week after their initial visit to share lab results. “This was identified as a missed opportunity for us to ask about their status, whether they filled their prescription, or if they need further assistance,” she said. “This is an area where our registered nurses are going to be taking on a greater role moving forward.”

Allmacher and team also discovered that, despite PrEP navigators arranging insurance coverage for clients on the day they receive their prescription, sometimes there were still barriers when the client showed up at the pharmacy to pick up their meds. The clinic does not have an in-house pharmacy and does not currently have the funding that would allow them to hand patients a bottle of the appropriate medication when they leave the clinic.

“Navigating the copays and the insurance coverage and using financial assistance through the drug manufacturer — even though we have the support in the clinic, it seems like there’s a disconnect between our clinic and getting to the pharmacy. Not every pharmacy is super familiar with navigating those,” she said. “So we have started to identify some area pharmacies near our clinic that are great at navigating these, and we really try to get our patients to go to places we know can give them assistance.”

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

To Amanda Allmacher, DNP, RN, nurse practitioner at the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic, that means that same-day PrEP prescribing works and is acceptable. But there’s more work to do on the clinic and pharmacy side to make HIV protection a reality for most of her patients. Allmacher presented her data at the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 virtual annual meeting.

Dawn K. Smith, MD, epidemiologist and medical officer in the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said this adds to other data to show that we’re now entering the next phase of PrEP implementation.

“Our original focus was on uptake — informing folks what PrEP is, why they might benefit from its use, and then prescribing it if accepted,” Smith told Medscape Medical News via email. “Whether standard or same-day [PrEP prescribing], it is clear that uptake is only the first step.”

Nurses help navigate

Patients who attended the Detroit Public Health STD Clinic are more likely to be younger, have no insurance, and otherwise “have little to no contact with the healthcare system,” Allmacher said in her presentation. They also tend to come from communities that bear the greatest burden of HIV in the US — in other words, they are often the people most missed in PrEP rollouts thus far.

In response, the clinic implemented a same-day PrEP protocol, in which registered nurses trained in HIV risk assessment identify clients who might most benefit from PrEP. Criteria often include the presence of other STIs. Once the nurse explains what PrEP is and how it works, if the patient is interested, clients meet with a nurse practitioner right then to get the prescription for PrEP. The clinic also does labs to rule out current HIV infection, hepatitis B, metabolic issues, and other STI screening.

But it doesn’t stop there. The clinic used grant funding to offer PrEP navigation and financial counseling services, which help clients navigate the sometimes-thorny process of paying for PrEP. Payment comes either through Medicaid, which in Michigan charges $3 a month for a PrEP prescription, through patient assistance programs, or through private insurance. With clients under age 18 who are interested in PrEP, the clinic works to find a way to access PrEP without having to inform their parents. These same navigators schedule follow-up appointments, offer appointment reminders, and contact clients when they miss an appointment.

“Our navigators and financial counselors are a huge support for our same-day PrEP starts, helping with financial assistance, prior authorization, navigating different plans, and helping patients apply for Medicaid when appropriate,” she said.

The clinic also offers community outreach and incentives, which can include gift cards, bus passes, and pill containers, among other things.

This was a key lesson in setting up the program, Allmacher told Medscape Medical News.

“Starting PrEP at that initial visit allows for clinicians to meet patients where they are and administer care in a more equitable manner,” Allmacher said via email. “Use all available resources and funding sources. We have a versatile team working together to increase access for patients and promote HIV prevention and risk reduction.”

Script vs. follow-up

This approach is common, used in places like New York City and San Francisco. So once it was set up Allmacher sat back and waited to see how the program helped clients protect themselves from HIV.

Of the 451 clients eligible for PrEP in 2019, 336 were gay and bisexual men, 6 were transgender women, 61 were heterosexual, cisgender men, and 48 were cisgender women. One transgender man also screened as eligible. Allmacher did not break down data by race.

Uptake was high: 70% of all eligible clients did receive a prescription for PrEP, either generic tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada) or tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy). And uptake was high among people most at risk: 80% of gay and bisexual men who were eligible got a prescription, 60% of eligible cisgender women, 50% of the small number of transgender women, and 32.7% of heterosexual cisgender men did as well. The 1 transgender man also received a prescription.

This is a higher rate than found in a recent PrEP demonstration project, which found that despite gay and bisexual men, transgender adults, and Black people having the highest risk for HIV in the US, state health departments were more likely to refer heterosexual adults for PrEP.

That high uptake rate is encouraging, but follow-up? Not so much. After initial intake, clients are meant to return in a month to double-check their labs, ask about side effects, and start their 90-day supply of the medication. But just 40% showed up for their 30-day appointment, Allmacher said. And only one third of those showed up for the follow-up in 90 days.

By the end of 2019, just 73 of the original 451 clients screened were still taking PrEP.

“It was surprising to see just how significant the follow-up dropped off after that first visit, when the patient initially accepted the prescription,” Allmacher said.

And while it’s possible that some clients get their follow-up care from their primary care providers, “our clinic serves individuals regardless of insurance status and many do not identify having access to primary care for any type of service, PrEP or otherwise,” she said.

5 HIV acquisitions

In addition, the program review identified five clients who had been offered PrEP or had taken PrEP briefly who later acquired HIV. Those clients were offered same-day antiretroviral treatment, Allmacher said.

“So we’re finding people who are at high risk for HIV and we can prevent them, but we’re still not quite doing enough,” Allmacher said of those acquisitions. “Clearly we have a lot of work to do to focus on HIV prevention, and we are looking to create a more formal follow-up process” from the clinic’s side.

For instance, clinic staff call clients 1 week after their initial visit to share lab results. “This was identified as a missed opportunity for us to ask about their status, whether they filled their prescription, or if they need further assistance,” she said. “This is an area where our registered nurses are going to be taking on a greater role moving forward.”

Allmacher and team also discovered that, despite PrEP navigators arranging insurance coverage for clients on the day they receive their prescription, sometimes there were still barriers when the client showed up at the pharmacy to pick up their meds. The clinic does not have an in-house pharmacy and does not currently have the funding that would allow them to hand patients a bottle of the appropriate medication when they leave the clinic.

“Navigating the copays and the insurance coverage and using financial assistance through the drug manufacturer — even though we have the support in the clinic, it seems like there’s a disconnect between our clinic and getting to the pharmacy. Not every pharmacy is super familiar with navigating those,” she said. “So we have started to identify some area pharmacies near our clinic that are great at navigating these, and we really try to get our patients to go to places we know can give them assistance.”

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts disagree with USPSTF’s take on pediatric blood pressure screening

Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for high blood pressure in children and adolescents, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reported in JAMA.

However, two experts in this area suggested there is evidence if you know where to look, and pediatric BP testing is crucial now.

In this update to the 2013 statement, the USPSTF’s systematic review focused on evidence surrounding the benefits of screening, test accuracy, treatment effectiveness and harms, and links between hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) markers in childhood and adulthood.

Limited information was available on the accuracy of screening tests. No studies were found that directly evaluated screening for pediatric high BP or reported effectiveness in delayed onset or risk reduction for cardiovascular outcomes related to hypertension. Additionally, no studies were found that addressed screening for secondary hypertension in asymptomatic pediatric patients. No studies were found that evaluated the treatment of primary childhood hypertension and BP reduction or other outcomes in adulthood. The panel also was unable to identify any studies that reported on harms of screening and treatment.

When the adult framework for cardiovascular risk reduction is extended in pediatric patients, there are methodological challenges that make it harder to determine how much of the potential burden can actually be prevented, the panel said. The clinical and epidemiologic significance of percentile thresholds that are used to determine their ties to adult CVD has limited supporting evidence. Inconsistent performance characteristics of current diagnostic methods, of which there are few, tend to yield unfavorable high false-positive rates. Such false positives are potentially harmful, because they lead to “unnecessary secondary evaluations or treatments.” Because pharmacologic management of pediatric hypertension is continued for a much longer period, it is the increased likelihood of adverse events that should be cause for concern.

Should the focus for screening be shifted to significant risk factors?

In an accompanying editorial, Joseph T. Flynn, MD, MS, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, said that the outcome of the latest statement is expected, “given how the key questions were framed and the analysis performed.” To begin, he suggested restating the question: “What is the best approach to assess whether childhood BP measurement is associated with adult CVD or whether treatment of high BP in childhood is associated with reducing the burden of adult CVD?” The answer is to tackle these questions with randomized clinical trials that compare screening to no screening and treatment to no treatment. But such studies are likely infeasible, partly because of the required length of follow-up of 5-6 decades.

Perhaps a better question would be: “Does BP measurement in childhood identify children and adolescents who already have markers of CVD or who are at risk of developing them as adults?” Were these youth to be identified, they would become candidates for approaches that seek to prevent disease progression. Reframing the question in this manner better positions physicians to focus on prevention and sidestep “the requirement that the only acceptable outcome is prevention of CVD events in adulthood,” he explained.

The next step would be to identify data already available to address the reframed question. Cross-sectional studies could be used to make the association between BP levels and cardiovascular risk markers already present. For example, several publications from the multicenter Study of High Blood Pressure in Pediatrics: Adult Hypertension Onset in Youth (SHIP-AHOY), which enrolled roughly 400 youth, provided data that reinforce prior single-center studies that essentially proved there are adverse consequences for youth with high BP, and they “set the stage for the institution of measures designed to reverse target-organ damage and reduce cardiovascular risk in youth,” said Dr. Flynn.

More specifically, results from SHIP-AHOY “have demonstrated that increased left ventricular mass can be demonstrated at BP levels currently classified as normotensive and that abnormal left ventricular function can be seen at similar BP levels,” Dr. Flynn noted. In addition, “they have established a substantial association between an abnormal metabolic phenotype and several forms of target-organ damage associated with high BP.”

One approach is to analyze longitudinal cohort studies

Because there is a paucity of prospective clinical trials, Dr. Flynn suggested that analyzing longitudinal cohort studies would be the most effective approach for evaluating the potential link between current BP levels and future CVD. Such studies already have “data that address an important point raised in the USPSTF statement, namely whether the pediatric percentile-based BP cut points, such as those in the 2017 AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] guideline, are associated with adult hypertension and CVD,” noted Dr. Flynn. “In the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium study, the specific childhood BP levels that were associated with increased adult carotid intima-medial thickness were remarkably similar to the BP percentile cut points in the AAP guideline for children of similar ages.”

Analysis of data from the Bogalusa Heart Study found looking at children classified as having high BP by the 2017 AAP guideline had “increased relative risks of having hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, or metabolic syndrome as adults 36 years later.”

“The conclusions of the USPSTF statement underscore the need for additional research on childhood high BP and its association with adult CVD. The starting points for such research can be deduced from currently available cross-sectional and longitudinal data, which demonstrate the detrimental outcomes associated with high BP in youth. Using these data to reframe and answer the questions raised by the USPSTF should point the way toward effective prevention of adult CVD,” concluded Dr. Flynn.

In a separate interview, Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, medical director of the preventive cardiology clinic at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, noted that in spite of USPSTF’s findings, there is actually an association between children with high blood pressure and intermediate outcomes in adults.

“Dr. Flynn suggests reframing the question. In fact, evidence exists that children with high blood pressure are at higher risk of left ventricular hypertrophy, increased arterial stiffness, and changes in retinal arteries,” noted Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

Evidence of pediatric heart damage has been documented in autopsies

“It is imperative that children have blood pressure evaluation,” she urged. “There is evidence that there are changes similar to those seen in adults with cardiovascular compromise. It has been shown that children dying of other causes [accidents] who have these problems also have more plaque on autopsy, indicating that those with high blood pressure are more likely to have markers of CVD already present in childhood.

“One of the keys of pediatric medicine is prevention and the counseling for prevention of adult diseases. The duration of study necessary to objectively determine whether treatment of hypertension in childhood reduces the risk of adult cardiac problems is extensive. If nothing is done now, we are putting more future generations in danger. We must provide appropriate counseling for children and their families regarding lifestyle improvements, to have a chance to improve cardiovascular risk factors in adults, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia and/or obesity,” urged Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and honoraria. Dr. Barry received grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The U.S. Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality support the operations of the USPSTF. Dr. Flynn reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate and Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Sexson Tejtel said she had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: USPSTF. JAMA. 2020 Nov 10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20122.

Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for high blood pressure in children and adolescents, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reported in JAMA.

However, two experts in this area suggested there is evidence if you know where to look, and pediatric BP testing is crucial now.

In this update to the 2013 statement, the USPSTF’s systematic review focused on evidence surrounding the benefits of screening, test accuracy, treatment effectiveness and harms, and links between hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) markers in childhood and adulthood.

Limited information was available on the accuracy of screening tests. No studies were found that directly evaluated screening for pediatric high BP or reported effectiveness in delayed onset or risk reduction for cardiovascular outcomes related to hypertension. Additionally, no studies were found that addressed screening for secondary hypertension in asymptomatic pediatric patients. No studies were found that evaluated the treatment of primary childhood hypertension and BP reduction or other outcomes in adulthood. The panel also was unable to identify any studies that reported on harms of screening and treatment.

When the adult framework for cardiovascular risk reduction is extended in pediatric patients, there are methodological challenges that make it harder to determine how much of the potential burden can actually be prevented, the panel said. The clinical and epidemiologic significance of percentile thresholds that are used to determine their ties to adult CVD has limited supporting evidence. Inconsistent performance characteristics of current diagnostic methods, of which there are few, tend to yield unfavorable high false-positive rates. Such false positives are potentially harmful, because they lead to “unnecessary secondary evaluations or treatments.” Because pharmacologic management of pediatric hypertension is continued for a much longer period, it is the increased likelihood of adverse events that should be cause for concern.

Should the focus for screening be shifted to significant risk factors?

In an accompanying editorial, Joseph T. Flynn, MD, MS, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, said that the outcome of the latest statement is expected, “given how the key questions were framed and the analysis performed.” To begin, he suggested restating the question: “What is the best approach to assess whether childhood BP measurement is associated with adult CVD or whether treatment of high BP in childhood is associated with reducing the burden of adult CVD?” The answer is to tackle these questions with randomized clinical trials that compare screening to no screening and treatment to no treatment. But such studies are likely infeasible, partly because of the required length of follow-up of 5-6 decades.

Perhaps a better question would be: “Does BP measurement in childhood identify children and adolescents who already have markers of CVD or who are at risk of developing them as adults?” Were these youth to be identified, they would become candidates for approaches that seek to prevent disease progression. Reframing the question in this manner better positions physicians to focus on prevention and sidestep “the requirement that the only acceptable outcome is prevention of CVD events in adulthood,” he explained.

The next step would be to identify data already available to address the reframed question. Cross-sectional studies could be used to make the association between BP levels and cardiovascular risk markers already present. For example, several publications from the multicenter Study of High Blood Pressure in Pediatrics: Adult Hypertension Onset in Youth (SHIP-AHOY), which enrolled roughly 400 youth, provided data that reinforce prior single-center studies that essentially proved there are adverse consequences for youth with high BP, and they “set the stage for the institution of measures designed to reverse target-organ damage and reduce cardiovascular risk in youth,” said Dr. Flynn.

More specifically, results from SHIP-AHOY “have demonstrated that increased left ventricular mass can be demonstrated at BP levels currently classified as normotensive and that abnormal left ventricular function can be seen at similar BP levels,” Dr. Flynn noted. In addition, “they have established a substantial association between an abnormal metabolic phenotype and several forms of target-organ damage associated with high BP.”

One approach is to analyze longitudinal cohort studies

Because there is a paucity of prospective clinical trials, Dr. Flynn suggested that analyzing longitudinal cohort studies would be the most effective approach for evaluating the potential link between current BP levels and future CVD. Such studies already have “data that address an important point raised in the USPSTF statement, namely whether the pediatric percentile-based BP cut points, such as those in the 2017 AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] guideline, are associated with adult hypertension and CVD,” noted Dr. Flynn. “In the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium study, the specific childhood BP levels that were associated with increased adult carotid intima-medial thickness were remarkably similar to the BP percentile cut points in the AAP guideline for children of similar ages.”

Analysis of data from the Bogalusa Heart Study found looking at children classified as having high BP by the 2017 AAP guideline had “increased relative risks of having hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, or metabolic syndrome as adults 36 years later.”

“The conclusions of the USPSTF statement underscore the need for additional research on childhood high BP and its association with adult CVD. The starting points for such research can be deduced from currently available cross-sectional and longitudinal data, which demonstrate the detrimental outcomes associated with high BP in youth. Using these data to reframe and answer the questions raised by the USPSTF should point the way toward effective prevention of adult CVD,” concluded Dr. Flynn.

In a separate interview, Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, medical director of the preventive cardiology clinic at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, noted that in spite of USPSTF’s findings, there is actually an association between children with high blood pressure and intermediate outcomes in adults.

“Dr. Flynn suggests reframing the question. In fact, evidence exists that children with high blood pressure are at higher risk of left ventricular hypertrophy, increased arterial stiffness, and changes in retinal arteries,” noted Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

Evidence of pediatric heart damage has been documented in autopsies

“It is imperative that children have blood pressure evaluation,” she urged. “There is evidence that there are changes similar to those seen in adults with cardiovascular compromise. It has been shown that children dying of other causes [accidents] who have these problems also have more plaque on autopsy, indicating that those with high blood pressure are more likely to have markers of CVD already present in childhood.

“One of the keys of pediatric medicine is prevention and the counseling for prevention of adult diseases. The duration of study necessary to objectively determine whether treatment of hypertension in childhood reduces the risk of adult cardiac problems is extensive. If nothing is done now, we are putting more future generations in danger. We must provide appropriate counseling for children and their families regarding lifestyle improvements, to have a chance to improve cardiovascular risk factors in adults, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia and/or obesity,” urged Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and honoraria. Dr. Barry received grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The U.S. Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality support the operations of the USPSTF. Dr. Flynn reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate and Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Sexson Tejtel said she had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: USPSTF. JAMA. 2020 Nov 10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20122.

Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for high blood pressure in children and adolescents, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reported in JAMA.

However, two experts in this area suggested there is evidence if you know where to look, and pediatric BP testing is crucial now.

In this update to the 2013 statement, the USPSTF’s systematic review focused on evidence surrounding the benefits of screening, test accuracy, treatment effectiveness and harms, and links between hypertension and cardiovascular disease (CVD) markers in childhood and adulthood.

Limited information was available on the accuracy of screening tests. No studies were found that directly evaluated screening for pediatric high BP or reported effectiveness in delayed onset or risk reduction for cardiovascular outcomes related to hypertension. Additionally, no studies were found that addressed screening for secondary hypertension in asymptomatic pediatric patients. No studies were found that evaluated the treatment of primary childhood hypertension and BP reduction or other outcomes in adulthood. The panel also was unable to identify any studies that reported on harms of screening and treatment.

When the adult framework for cardiovascular risk reduction is extended in pediatric patients, there are methodological challenges that make it harder to determine how much of the potential burden can actually be prevented, the panel said. The clinical and epidemiologic significance of percentile thresholds that are used to determine their ties to adult CVD has limited supporting evidence. Inconsistent performance characteristics of current diagnostic methods, of which there are few, tend to yield unfavorable high false-positive rates. Such false positives are potentially harmful, because they lead to “unnecessary secondary evaluations or treatments.” Because pharmacologic management of pediatric hypertension is continued for a much longer period, it is the increased likelihood of adverse events that should be cause for concern.

Should the focus for screening be shifted to significant risk factors?

In an accompanying editorial, Joseph T. Flynn, MD, MS, of Seattle Children’s Hospital, said that the outcome of the latest statement is expected, “given how the key questions were framed and the analysis performed.” To begin, he suggested restating the question: “What is the best approach to assess whether childhood BP measurement is associated with adult CVD or whether treatment of high BP in childhood is associated with reducing the burden of adult CVD?” The answer is to tackle these questions with randomized clinical trials that compare screening to no screening and treatment to no treatment. But such studies are likely infeasible, partly because of the required length of follow-up of 5-6 decades.

Perhaps a better question would be: “Does BP measurement in childhood identify children and adolescents who already have markers of CVD or who are at risk of developing them as adults?” Were these youth to be identified, they would become candidates for approaches that seek to prevent disease progression. Reframing the question in this manner better positions physicians to focus on prevention and sidestep “the requirement that the only acceptable outcome is prevention of CVD events in adulthood,” he explained.

The next step would be to identify data already available to address the reframed question. Cross-sectional studies could be used to make the association between BP levels and cardiovascular risk markers already present. For example, several publications from the multicenter Study of High Blood Pressure in Pediatrics: Adult Hypertension Onset in Youth (SHIP-AHOY), which enrolled roughly 400 youth, provided data that reinforce prior single-center studies that essentially proved there are adverse consequences for youth with high BP, and they “set the stage for the institution of measures designed to reverse target-organ damage and reduce cardiovascular risk in youth,” said Dr. Flynn.

More specifically, results from SHIP-AHOY “have demonstrated that increased left ventricular mass can be demonstrated at BP levels currently classified as normotensive and that abnormal left ventricular function can be seen at similar BP levels,” Dr. Flynn noted. In addition, “they have established a substantial association between an abnormal metabolic phenotype and several forms of target-organ damage associated with high BP.”

One approach is to analyze longitudinal cohort studies

Because there is a paucity of prospective clinical trials, Dr. Flynn suggested that analyzing longitudinal cohort studies would be the most effective approach for evaluating the potential link between current BP levels and future CVD. Such studies already have “data that address an important point raised in the USPSTF statement, namely whether the pediatric percentile-based BP cut points, such as those in the 2017 AAP [American Academy of Pediatrics] guideline, are associated with adult hypertension and CVD,” noted Dr. Flynn. “In the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium study, the specific childhood BP levels that were associated with increased adult carotid intima-medial thickness were remarkably similar to the BP percentile cut points in the AAP guideline for children of similar ages.”

Analysis of data from the Bogalusa Heart Study found looking at children classified as having high BP by the 2017 AAP guideline had “increased relative risks of having hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, or metabolic syndrome as adults 36 years later.”

“The conclusions of the USPSTF statement underscore the need for additional research on childhood high BP and its association with adult CVD. The starting points for such research can be deduced from currently available cross-sectional and longitudinal data, which demonstrate the detrimental outcomes associated with high BP in youth. Using these data to reframe and answer the questions raised by the USPSTF should point the way toward effective prevention of adult CVD,” concluded Dr. Flynn.

In a separate interview, Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, medical director of the preventive cardiology clinic at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, noted that in spite of USPSTF’s findings, there is actually an association between children with high blood pressure and intermediate outcomes in adults.

“Dr. Flynn suggests reframing the question. In fact, evidence exists that children with high blood pressure are at higher risk of left ventricular hypertrophy, increased arterial stiffness, and changes in retinal arteries,” noted Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

Evidence of pediatric heart damage has been documented in autopsies

“It is imperative that children have blood pressure evaluation,” she urged. “There is evidence that there are changes similar to those seen in adults with cardiovascular compromise. It has been shown that children dying of other causes [accidents] who have these problems also have more plaque on autopsy, indicating that those with high blood pressure are more likely to have markers of CVD already present in childhood.

“One of the keys of pediatric medicine is prevention and the counseling for prevention of adult diseases. The duration of study necessary to objectively determine whether treatment of hypertension in childhood reduces the risk of adult cardiac problems is extensive. If nothing is done now, we are putting more future generations in danger. We must provide appropriate counseling for children and their families regarding lifestyle improvements, to have a chance to improve cardiovascular risk factors in adults, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia and/or obesity,” urged Dr. Sexson Tejtel.

All members of the USPSTF received travel reimbursement and honoraria. Dr. Barry received grants and personal fees from Healthwise. The U.S. Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality support the operations of the USPSTF. Dr. Flynn reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate and Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Sexson Tejtel said she had no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: USPSTF. JAMA. 2020 Nov 10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20122.

FROM JAMA

Should our patients really go home for the holidays?

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

United States adds nearly 74,000 more children with COVID-19

The new weekly high for COVID-19 cases in children announced last week has been surpassed already, as the United States experienced almost 74,000 new pediatric cases for the week ending Nov. 5, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of COVID-19 cases in children is now 927,518 in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report.

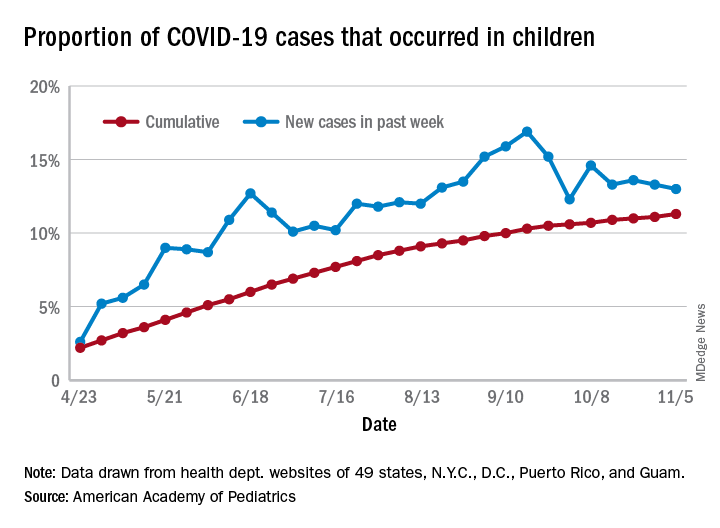

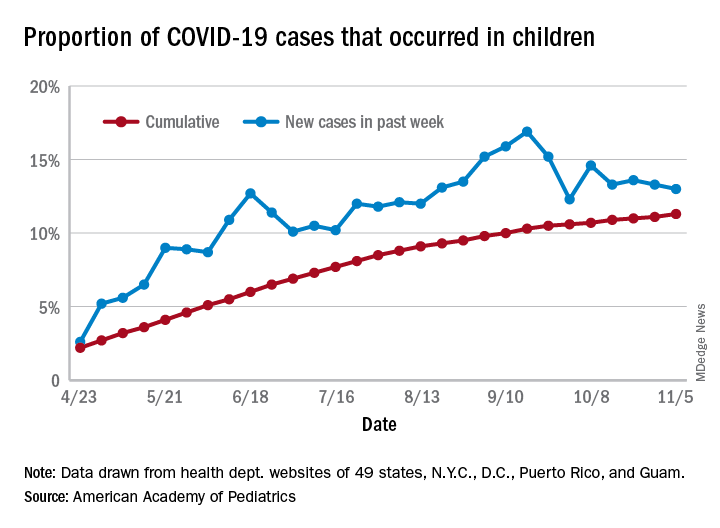

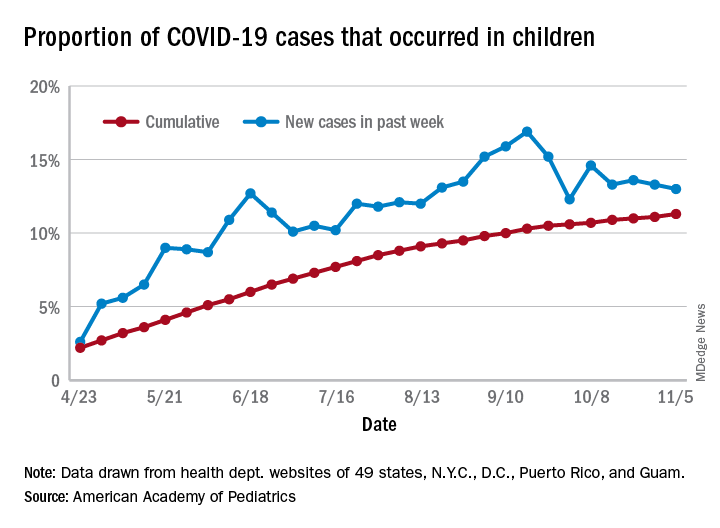

Cumulatively, children represent 11.3% of all COVID-19 cases in those jurisdictions, up from 11.1% a week ago. For just the past week, those 73,883 children represent 13.0% of the 567,672 new cases reported among all ages. That proportion peaked at 16.9% in mid-September, the AAP/CHA data show.

Dropping down to the state level, cumulative proportions as of Nov. 5 range from 5.2% in New Jersey to 23.3% in Wyoming, with 11 other states over 15%. California has had more cases, 100,856, than any other state, and Vermont the fewest at 329, the AAP and CHA said.