User login

Cannabis crimps teen cognitive development

BARCELONA – What would you predict has a greater detrimental effect on adolescent cognitive development: alcohol or cannabis use?

The evidence-based answer may come as a surprise. It certainly did for Patricia Conrod, PhD, who led the large population-based study that addressed the question.

“Generally, we found no effect of alcohol on cognitive development, which was a huge surprise to us. It might be related to the fact that the quantity of alcohol consumption in this young sample just wasn’t high enough to produce significant effects on cognitive development. But, to our surprise, we found rather significant effects of cannabis use on cognitive development,” she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, cannabis use proved to have detrimental effects on all four cognitive domains assessed in the study: working memory, perceptual reasoning, delayed recall, and inhibitory control, reported Dr. Conrod, professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal.

Her recently study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, included 3,826 seventh-grade students at 31 Montreal-area schools. They constituted 5% of all students entering that grade in the greater Montreal area. Participants were prospectively assessed annually for 4 years regarding their use or nonuse of alcohol or cannabis and also underwent neurocognitive testing on the four domains of interest. The assessments were done on school computers with preservation of student confidentiality. Investigators used a Big Data approach to model the relationship between the extent of substance use and neurocognitive function variables over time.

Abstinent students were the best performers on the neurocognitive testing. Cannabis use, but not alcohol, in a given year was associated with concurrent adverse effects on all four cognitive domains. In addition, cannabis use showed evidence of having a neurotoxic lag effect on inhibitory control and working memory. This took the form of a lasting effect: A student who reported using cannabis 1 year but not the next showed impairment of inhibitory control and working memory during both years. And a student who used cannabis both years was even more impaired in those domains.

Dr. Conrod found the evidence of a neurotoxic effect of cannabis use on inhibitory control to be of particular concern because in earlier studies she established that impaired inhibitory control is a strong independent risk factor for subsequent substance use disorders.

”So what we’re seeing is indeed that early onset substance use is interfering with cognitive development, which now sets us up to be able to answer the question of whether evidence-based prevention protects cognitive development by delaying early onset of substance use. And over the longer term, does that protect young people against addiction?”

Dr. Conrod and her coworkers are now in the process of obtaining answers to those questions in the large ongoing Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded Co-Venture Trial. This randomized trial involving thousands of adolescent students used the investigators’ Preventure Program, a school-based, personality-targeted intervention for prevention of substance use and abuse.

The Preventure Program involves two 90-minute group sessions of manual-based cognitive-behavioral therapy. Students are invited to participate if they score at least one standard deviation above the school mean on one of four personality traits that have been shown to increase the risk of substance misuse and psychiatric disorders. The four personality traits are sensation seeking, impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and hopelessness. Typically, about 45% of students met that threshold, and 85% of those invited to participate in the program volunteered to do so. Students of similar personality type are grouped together for the targeted therapy sessions.

This brief coping skills intervention has been shown in multiple randomized trials around the world to reduce the likelihood of substance use in at-risk adolescents. For example, in an early trial involving 732 high school students in London, participation in the Preventure Program was associated with a 30% reduction in the likelihood of taking up the use of cannabis within the next 2 years, an 80% reduction in the likelihood of taking up cocaine, and a 50% reduction in the use of other drugs (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67[1]:85-93).

[email protected]

SOURCE: Conrod P. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020202.

BARCELONA – What would you predict has a greater detrimental effect on adolescent cognitive development: alcohol or cannabis use?

The evidence-based answer may come as a surprise. It certainly did for Patricia Conrod, PhD, who led the large population-based study that addressed the question.

“Generally, we found no effect of alcohol on cognitive development, which was a huge surprise to us. It might be related to the fact that the quantity of alcohol consumption in this young sample just wasn’t high enough to produce significant effects on cognitive development. But, to our surprise, we found rather significant effects of cannabis use on cognitive development,” she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, cannabis use proved to have detrimental effects on all four cognitive domains assessed in the study: working memory, perceptual reasoning, delayed recall, and inhibitory control, reported Dr. Conrod, professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal.

Her recently study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, included 3,826 seventh-grade students at 31 Montreal-area schools. They constituted 5% of all students entering that grade in the greater Montreal area. Participants were prospectively assessed annually for 4 years regarding their use or nonuse of alcohol or cannabis and also underwent neurocognitive testing on the four domains of interest. The assessments were done on school computers with preservation of student confidentiality. Investigators used a Big Data approach to model the relationship between the extent of substance use and neurocognitive function variables over time.

Abstinent students were the best performers on the neurocognitive testing. Cannabis use, but not alcohol, in a given year was associated with concurrent adverse effects on all four cognitive domains. In addition, cannabis use showed evidence of having a neurotoxic lag effect on inhibitory control and working memory. This took the form of a lasting effect: A student who reported using cannabis 1 year but not the next showed impairment of inhibitory control and working memory during both years. And a student who used cannabis both years was even more impaired in those domains.

Dr. Conrod found the evidence of a neurotoxic effect of cannabis use on inhibitory control to be of particular concern because in earlier studies she established that impaired inhibitory control is a strong independent risk factor for subsequent substance use disorders.

”So what we’re seeing is indeed that early onset substance use is interfering with cognitive development, which now sets us up to be able to answer the question of whether evidence-based prevention protects cognitive development by delaying early onset of substance use. And over the longer term, does that protect young people against addiction?”

Dr. Conrod and her coworkers are now in the process of obtaining answers to those questions in the large ongoing Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded Co-Venture Trial. This randomized trial involving thousands of adolescent students used the investigators’ Preventure Program, a school-based, personality-targeted intervention for prevention of substance use and abuse.

The Preventure Program involves two 90-minute group sessions of manual-based cognitive-behavioral therapy. Students are invited to participate if they score at least one standard deviation above the school mean on one of four personality traits that have been shown to increase the risk of substance misuse and psychiatric disorders. The four personality traits are sensation seeking, impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and hopelessness. Typically, about 45% of students met that threshold, and 85% of those invited to participate in the program volunteered to do so. Students of similar personality type are grouped together for the targeted therapy sessions.

This brief coping skills intervention has been shown in multiple randomized trials around the world to reduce the likelihood of substance use in at-risk adolescents. For example, in an early trial involving 732 high school students in London, participation in the Preventure Program was associated with a 30% reduction in the likelihood of taking up the use of cannabis within the next 2 years, an 80% reduction in the likelihood of taking up cocaine, and a 50% reduction in the use of other drugs (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67[1]:85-93).

[email protected]

SOURCE: Conrod P. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020202.

BARCELONA – What would you predict has a greater detrimental effect on adolescent cognitive development: alcohol or cannabis use?

The evidence-based answer may come as a surprise. It certainly did for Patricia Conrod, PhD, who led the large population-based study that addressed the question.

“Generally, we found no effect of alcohol on cognitive development, which was a huge surprise to us. It might be related to the fact that the quantity of alcohol consumption in this young sample just wasn’t high enough to produce significant effects on cognitive development. But, to our surprise, we found rather significant effects of cannabis use on cognitive development,” she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Indeed, cannabis use proved to have detrimental effects on all four cognitive domains assessed in the study: working memory, perceptual reasoning, delayed recall, and inhibitory control, reported Dr. Conrod, professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal.

Her recently study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, included 3,826 seventh-grade students at 31 Montreal-area schools. They constituted 5% of all students entering that grade in the greater Montreal area. Participants were prospectively assessed annually for 4 years regarding their use or nonuse of alcohol or cannabis and also underwent neurocognitive testing on the four domains of interest. The assessments were done on school computers with preservation of student confidentiality. Investigators used a Big Data approach to model the relationship between the extent of substance use and neurocognitive function variables over time.

Abstinent students were the best performers on the neurocognitive testing. Cannabis use, but not alcohol, in a given year was associated with concurrent adverse effects on all four cognitive domains. In addition, cannabis use showed evidence of having a neurotoxic lag effect on inhibitory control and working memory. This took the form of a lasting effect: A student who reported using cannabis 1 year but not the next showed impairment of inhibitory control and working memory during both years. And a student who used cannabis both years was even more impaired in those domains.

Dr. Conrod found the evidence of a neurotoxic effect of cannabis use on inhibitory control to be of particular concern because in earlier studies she established that impaired inhibitory control is a strong independent risk factor for subsequent substance use disorders.

”So what we’re seeing is indeed that early onset substance use is interfering with cognitive development, which now sets us up to be able to answer the question of whether evidence-based prevention protects cognitive development by delaying early onset of substance use. And over the longer term, does that protect young people against addiction?”

Dr. Conrod and her coworkers are now in the process of obtaining answers to those questions in the large ongoing Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded Co-Venture Trial. This randomized trial involving thousands of adolescent students used the investigators’ Preventure Program, a school-based, personality-targeted intervention for prevention of substance use and abuse.

The Preventure Program involves two 90-minute group sessions of manual-based cognitive-behavioral therapy. Students are invited to participate if they score at least one standard deviation above the school mean on one of four personality traits that have been shown to increase the risk of substance misuse and psychiatric disorders. The four personality traits are sensation seeking, impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and hopelessness. Typically, about 45% of students met that threshold, and 85% of those invited to participate in the program volunteered to do so. Students of similar personality type are grouped together for the targeted therapy sessions.

This brief coping skills intervention has been shown in multiple randomized trials around the world to reduce the likelihood of substance use in at-risk adolescents. For example, in an early trial involving 732 high school students in London, participation in the Preventure Program was associated with a 30% reduction in the likelihood of taking up the use of cannabis within the next 2 years, an 80% reduction in the likelihood of taking up cocaine, and a 50% reduction in the use of other drugs (Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;67[1]:85-93).

[email protected]

SOURCE: Conrod P. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020202.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The observed neurotoxic effect on impulse control may spell future trouble.

Study details: This population-based study included 3,826 Montreal-area seventh graders who were prospectively assessed annually for 4 years regarding their cannabis and alcohol use and also underwent neurocognitive testing.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Source: Conrod P. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020202.

TB vaccine shows promise in previously infected

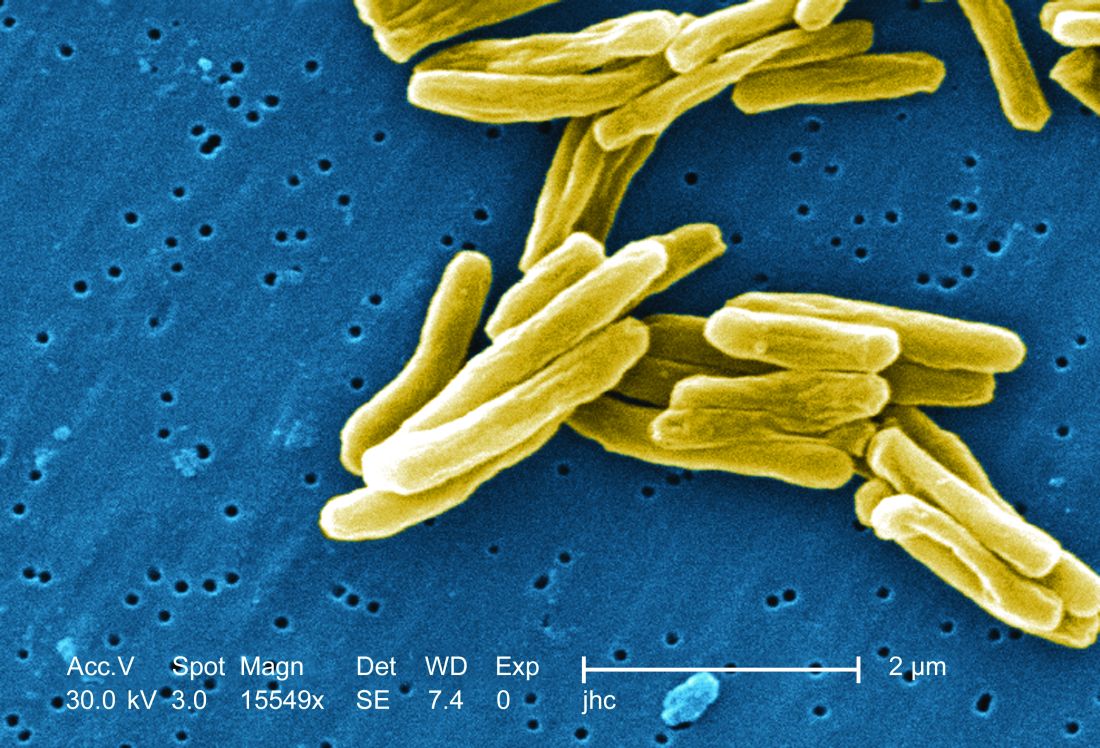

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

REPORTING FROM IDWEEK 2018

Key clinical point: The vaccine is the first to show efficacy in patients previously exposed to the TB bacterium.

Major finding: The vaccine had a protective efficacy of 54%.

Study details: Randomized, controlled trial with 3,330 participants.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

Source: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120.

Corporal punishment bans may reduce youth violence

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Key clinical point: Nations that ban corporal punishment of children have lower rates of youth violence.

Major finding: Countries with total bans on corporal punishment reported rates of fighting in males 31% lower than countries with no bans.

Study details: An ecological study evaluating school-based health surveys of 403,604 adolescents from 88 low- to high-income countries.

Disclosures: Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

Source: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

FDA approves omadacycline for pneumonia and skin infections

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

Obesity in early childhood promotes obese adolescence

Most obese adolescents first became obese between the ages of 2 and 6 years, based on data from approximately 50,000 children in Germany.

Identifying periods of weight gain in childhood can help develop intervention and prevention strategies to reduce the risk of obesity in adolescence, wrote Mandy Geserick, MSc, of the University of Leipzig, Germany, and her colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the timing of weight gain in early childhood, the researchers reviewed data from a German patient registry designed to monitor growth data. The study population included 51,505 children who had at least one visit to a pediatrician between birth and age 14 years and a second visit between age 15 and 19 years.

Overall, the probability of being overweight or obese in adolescence was 29% among children who gained more weight in the preschool years, between the ages of 2 and 6 years (defined as a change in body mass index [BMI] of 0.2 or more to less than 2.0), compared with 20% among children whose preschool weight remained stable (defined as a change in BMI of more than −0.2 to less than 0.2) – a relative risk of 1.43.

“A total of 83% of the children with obesity at the age of 4 were overweight or obese in adolescence, and only 17% returned to a normal weight,” they wrote. In addition, 44% of children who were born large for gestational age were overweight or obese in adolescence.

“A practical clinical implication of our study results would be surveillance for BMI acceleration, which should be recognized before 6 years of age, even in the absence of obesity,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variation in the number of visits, the lack of data on many children beyond the age of 14 years, and the lack of data on parental weight and perinatal risk factors associated with obesity, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based design, and support the study hypothesis that obesity develops in early childhood and, once present, persists into adolescence.

“The specific dynamics and patterns of BMI in this early childhood period, rather than the absolute BMI, appear to be important factors in identifying children at risk for obesity later in life,” the researchers wrote. “It is therefore important for health care professionals, educational staff, and parents to become more sensitive to this critical time period.”

The study was supported by the German Research Council for the Clinical Research Center; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research; and the University of Leipzig, which was supported by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund, and the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. The CrescNet registry infrastructure was supported by grants from Hexal, Novo Nordisk, Merck Serono, Lilly Deutschland, Pfizer, and Ipsen Pharma. Dr. Geserick had no financial conflicts to report.

SOURCE: Geserick M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527.

Most normal-weight children remained in the normal range throughout childhood, but the association between obesity by the age of 5 years and obese adolescence is a “new and important” finding, Michael S. Freemark, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811305).

Although body mass index (BMI) generally decreases by age 5-6 years before increasing through adolescence, data from previous studies have shown that “an early or exaggerated ‘adiposity rebound’ portends an increased risk of obesity in later childhood and adolescence,” he wrote.

In this study, BMI increase between age 2 and 6 years was the strongest predictor of obesity in adolescence. Although the study was not designed to show causality, the results support the idea of a window of opportunity for intervention for children at increased risk for obesity, Dr. Freemark wrote. “The finding that the risk of adolescent obesity manifests by 3 to 5 years of age suggests that nutritional counseling should be considered when exaggerated weight gain persists or emerges after 2 years of age; it would be of value to test the efficacy of early dietary intervention in an appropriate trial.

“Counseling could be applied preemptively for families in which the parents are overweight, particularly if there is a history of maternal diabetes or smoking,” he added.

Dr. Freemark is affiliated with the division of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He disclosed grants from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, the American Heart Association, and the Humanitarian Innovation Fund and European Commission, as well as personal fees from Springer Publishing outside the submitted work.

Most normal-weight children remained in the normal range throughout childhood, but the association between obesity by the age of 5 years and obese adolescence is a “new and important” finding, Michael S. Freemark, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811305).

Although body mass index (BMI) generally decreases by age 5-6 years before increasing through adolescence, data from previous studies have shown that “an early or exaggerated ‘adiposity rebound’ portends an increased risk of obesity in later childhood and adolescence,” he wrote.

In this study, BMI increase between age 2 and 6 years was the strongest predictor of obesity in adolescence. Although the study was not designed to show causality, the results support the idea of a window of opportunity for intervention for children at increased risk for obesity, Dr. Freemark wrote. “The finding that the risk of adolescent obesity manifests by 3 to 5 years of age suggests that nutritional counseling should be considered when exaggerated weight gain persists or emerges after 2 years of age; it would be of value to test the efficacy of early dietary intervention in an appropriate trial.

“Counseling could be applied preemptively for families in which the parents are overweight, particularly if there is a history of maternal diabetes or smoking,” he added.

Dr. Freemark is affiliated with the division of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He disclosed grants from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, the American Heart Association, and the Humanitarian Innovation Fund and European Commission, as well as personal fees from Springer Publishing outside the submitted work.

Most normal-weight children remained in the normal range throughout childhood, but the association between obesity by the age of 5 years and obese adolescence is a “new and important” finding, Michael S. Freemark, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811305).

Although body mass index (BMI) generally decreases by age 5-6 years before increasing through adolescence, data from previous studies have shown that “an early or exaggerated ‘adiposity rebound’ portends an increased risk of obesity in later childhood and adolescence,” he wrote.

In this study, BMI increase between age 2 and 6 years was the strongest predictor of obesity in adolescence. Although the study was not designed to show causality, the results support the idea of a window of opportunity for intervention for children at increased risk for obesity, Dr. Freemark wrote. “The finding that the risk of adolescent obesity manifests by 3 to 5 years of age suggests that nutritional counseling should be considered when exaggerated weight gain persists or emerges after 2 years of age; it would be of value to test the efficacy of early dietary intervention in an appropriate trial.

“Counseling could be applied preemptively for families in which the parents are overweight, particularly if there is a history of maternal diabetes or smoking,” he added.

Dr. Freemark is affiliated with the division of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Duke University, Durham, N.C. He disclosed grants from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, the American Heart Association, and the Humanitarian Innovation Fund and European Commission, as well as personal fees from Springer Publishing outside the submitted work.

Most obese adolescents first became obese between the ages of 2 and 6 years, based on data from approximately 50,000 children in Germany.

Identifying periods of weight gain in childhood can help develop intervention and prevention strategies to reduce the risk of obesity in adolescence, wrote Mandy Geserick, MSc, of the University of Leipzig, Germany, and her colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the timing of weight gain in early childhood, the researchers reviewed data from a German patient registry designed to monitor growth data. The study population included 51,505 children who had at least one visit to a pediatrician between birth and age 14 years and a second visit between age 15 and 19 years.

Overall, the probability of being overweight or obese in adolescence was 29% among children who gained more weight in the preschool years, between the ages of 2 and 6 years (defined as a change in body mass index [BMI] of 0.2 or more to less than 2.0), compared with 20% among children whose preschool weight remained stable (defined as a change in BMI of more than −0.2 to less than 0.2) – a relative risk of 1.43.

“A total of 83% of the children with obesity at the age of 4 were overweight or obese in adolescence, and only 17% returned to a normal weight,” they wrote. In addition, 44% of children who were born large for gestational age were overweight or obese in adolescence.

“A practical clinical implication of our study results would be surveillance for BMI acceleration, which should be recognized before 6 years of age, even in the absence of obesity,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variation in the number of visits, the lack of data on many children beyond the age of 14 years, and the lack of data on parental weight and perinatal risk factors associated with obesity, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based design, and support the study hypothesis that obesity develops in early childhood and, once present, persists into adolescence.

“The specific dynamics and patterns of BMI in this early childhood period, rather than the absolute BMI, appear to be important factors in identifying children at risk for obesity later in life,” the researchers wrote. “It is therefore important for health care professionals, educational staff, and parents to become more sensitive to this critical time period.”

The study was supported by the German Research Council for the Clinical Research Center; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research; and the University of Leipzig, which was supported by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund, and the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. The CrescNet registry infrastructure was supported by grants from Hexal, Novo Nordisk, Merck Serono, Lilly Deutschland, Pfizer, and Ipsen Pharma. Dr. Geserick had no financial conflicts to report.

SOURCE: Geserick M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527.

Most obese adolescents first became obese between the ages of 2 and 6 years, based on data from approximately 50,000 children in Germany.

Identifying periods of weight gain in childhood can help develop intervention and prevention strategies to reduce the risk of obesity in adolescence, wrote Mandy Geserick, MSc, of the University of Leipzig, Germany, and her colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine.

To assess the timing of weight gain in early childhood, the researchers reviewed data from a German patient registry designed to monitor growth data. The study population included 51,505 children who had at least one visit to a pediatrician between birth and age 14 years and a second visit between age 15 and 19 years.

Overall, the probability of being overweight or obese in adolescence was 29% among children who gained more weight in the preschool years, between the ages of 2 and 6 years (defined as a change in body mass index [BMI] of 0.2 or more to less than 2.0), compared with 20% among children whose preschool weight remained stable (defined as a change in BMI of more than −0.2 to less than 0.2) – a relative risk of 1.43.

“A total of 83% of the children with obesity at the age of 4 were overweight or obese in adolescence, and only 17% returned to a normal weight,” they wrote. In addition, 44% of children who were born large for gestational age were overweight or obese in adolescence.

“A practical clinical implication of our study results would be surveillance for BMI acceleration, which should be recognized before 6 years of age, even in the absence of obesity,” the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the variation in the number of visits, the lack of data on many children beyond the age of 14 years, and the lack of data on parental weight and perinatal risk factors associated with obesity, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based design, and support the study hypothesis that obesity develops in early childhood and, once present, persists into adolescence.

“The specific dynamics and patterns of BMI in this early childhood period, rather than the absolute BMI, appear to be important factors in identifying children at risk for obesity later in life,” the researchers wrote. “It is therefore important for health care professionals, educational staff, and parents to become more sensitive to this critical time period.”

The study was supported by the German Research Council for the Clinical Research Center; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research; and the University of Leipzig, which was supported by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund, and the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. The CrescNet registry infrastructure was supported by grants from Hexal, Novo Nordisk, Merck Serono, Lilly Deutschland, Pfizer, and Ipsen Pharma. Dr. Geserick had no financial conflicts to report.

SOURCE: Geserick M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of children who were obese at age 4 years, 83% were overweight or obese in adolescence.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 51,505 children in Germany.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the German Research Council for the Clinical Research Center; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research; and the University of Leipzig, which was supported by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund, and the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. The CrescNet registry infrastructure was supported by grants from Hexal, Novo Nordisk, Merck Serono, Lilly Deutschland, Pfizer, and Ipsen Pharma. Dr. Geserick had no financial conflicts to report.

Source: Geserick M et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527.

Teens who vape are likely to add cigarette smoking

instead of substituting one for the other, according to research published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research.

“Our work provides more evidence that young people who use e-cigarettes progress to smoking cigarettes in the future,” Michael S. Dunbar, PhD, a behavioral scientist at the RAND Corp. stated in a press release. “This study also suggests that teens don’t substitute vaping products for cigarettes. Instead, they go on to use both products more frequently as they get older.”

Dr. Dunbar and his colleagues followed 2,039 adolescents aged 16-20 years who were originally enrolled in a Los Angeles–based substance use prevention program in sixth and seventh grade (2008) and completed annual Web-based surveys during 2015-2017 on their use of e-cigarettes (EC), cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. They also answered questions about their mental health with questions about anxiety and depression. The researchers used two models to measures associations between different factors.

The first model showed an association between EC and cigarette use. Then other factors, such as alcohol use, were introduced. Alcohol use was associated with increased cigarette use, and cigarette use was associated with increased use of alcohol. When introducing marijuana as a factor, associations remained between cigarette use and EC use, with higher EC use associated with greater marijuana use and vice versa. Greater cigarette use, however, was not predictive of later marijuana use. There was no association between EC use and mental health, but more cigarette use was associated with poorer mental health.

Under the second model, there was a moderate to strong association between EC use and cigarette use, and participants with greater EC use and greater cigarette use also reported higher alcohol use. There also was a significant between-person association with higher EC use, cigarette use, and marijuana use. There was a small negative association between mental health and cigarette use, but not with mental health and EC use,the researchers said.

“For young people, using these products may actually lead to more harm in the long run,” Dr. Dunbar said in the press release. “This highlights the importance of taking steps to prevent youth from vaping in the first place. One way to do this could be to limit e-cigarette and other tobacco advertising in kid-accessible spaces.”

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dunbar MS et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty179.

instead of substituting one for the other, according to research published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research.

“Our work provides more evidence that young people who use e-cigarettes progress to smoking cigarettes in the future,” Michael S. Dunbar, PhD, a behavioral scientist at the RAND Corp. stated in a press release. “This study also suggests that teens don’t substitute vaping products for cigarettes. Instead, they go on to use both products more frequently as they get older.”

Dr. Dunbar and his colleagues followed 2,039 adolescents aged 16-20 years who were originally enrolled in a Los Angeles–based substance use prevention program in sixth and seventh grade (2008) and completed annual Web-based surveys during 2015-2017 on their use of e-cigarettes (EC), cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. They also answered questions about their mental health with questions about anxiety and depression. The researchers used two models to measures associations between different factors.

The first model showed an association between EC and cigarette use. Then other factors, such as alcohol use, were introduced. Alcohol use was associated with increased cigarette use, and cigarette use was associated with increased use of alcohol. When introducing marijuana as a factor, associations remained between cigarette use and EC use, with higher EC use associated with greater marijuana use and vice versa. Greater cigarette use, however, was not predictive of later marijuana use. There was no association between EC use and mental health, but more cigarette use was associated with poorer mental health.

Under the second model, there was a moderate to strong association between EC use and cigarette use, and participants with greater EC use and greater cigarette use also reported higher alcohol use. There also was a significant between-person association with higher EC use, cigarette use, and marijuana use. There was a small negative association between mental health and cigarette use, but not with mental health and EC use,the researchers said.

“For young people, using these products may actually lead to more harm in the long run,” Dr. Dunbar said in the press release. “This highlights the importance of taking steps to prevent youth from vaping in the first place. One way to do this could be to limit e-cigarette and other tobacco advertising in kid-accessible spaces.”

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dunbar MS et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty179.

instead of substituting one for the other, according to research published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research.

“Our work provides more evidence that young people who use e-cigarettes progress to smoking cigarettes in the future,” Michael S. Dunbar, PhD, a behavioral scientist at the RAND Corp. stated in a press release. “This study also suggests that teens don’t substitute vaping products for cigarettes. Instead, they go on to use both products more frequently as they get older.”

Dr. Dunbar and his colleagues followed 2,039 adolescents aged 16-20 years who were originally enrolled in a Los Angeles–based substance use prevention program in sixth and seventh grade (2008) and completed annual Web-based surveys during 2015-2017 on their use of e-cigarettes (EC), cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. They also answered questions about their mental health with questions about anxiety and depression. The researchers used two models to measures associations between different factors.

The first model showed an association between EC and cigarette use. Then other factors, such as alcohol use, were introduced. Alcohol use was associated with increased cigarette use, and cigarette use was associated with increased use of alcohol. When introducing marijuana as a factor, associations remained between cigarette use and EC use, with higher EC use associated with greater marijuana use and vice versa. Greater cigarette use, however, was not predictive of later marijuana use. There was no association between EC use and mental health, but more cigarette use was associated with poorer mental health.

Under the second model, there was a moderate to strong association between EC use and cigarette use, and participants with greater EC use and greater cigarette use also reported higher alcohol use. There also was a significant between-person association with higher EC use, cigarette use, and marijuana use. There was a small negative association between mental health and cigarette use, but not with mental health and EC use,the researchers said.

“For young people, using these products may actually lead to more harm in the long run,” Dr. Dunbar said in the press release. “This highlights the importance of taking steps to prevent youth from vaping in the first place. One way to do this could be to limit e-cigarette and other tobacco advertising in kid-accessible spaces.”

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dunbar MS et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty179.

FROM NICOTINE & TOBACCO RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Adolescents who use e-cigarettes are more likely to progress to cigarette use, while continuing to vape.

Major finding: There was a significant bidirectional association between e-cigarette use and cigarette use, and some third factors such as alcohol use, marijuana use, and mental health.

Study details: A longitudinal study of adolescents aged 16-20 years enrolled in a substance use prevention program.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Dunbar MS et al. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty179.

Adalimumab safety profile similar in children and adults

The safety profile for adalimumab in children is similar to that of adults, according to findings published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In an analysis of data from seven clinical trials from 2002-2015, the most common adverse events across indications were upper respiratory tract infection (24 events per 100 patient-years), nasopharyngitis (17 events per 100 PY), and headache (20 events per 100 PY). Serious infections were the most frequent adverse events across indications (8% of all patients; 4 events per 100 PY), reported Gerd Horneff, MD, of the department of general pediatrics at Asklepios Klinik Sankt Augustin (Germany), and his coauthors.

All of the clinical trials were funded by AbbVie, and included 577 pediatric patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease. Patients received subcutaneous injection of adalimumab at a dosage of either 40 mg/0.8 mL or 20 mg/0.4 mL.

Adverse events that occurred after the first adalimumab dose and up to 70 days after the last dose were included. Serious adverse events were defined as “events that were fatal or immediately life-threatening; required inpatient or prolonged hospitalization; resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly, or spontaneous or elective abortion; or required medical or surgical intervention to prevent a serious outcome,” the authors said.

Infections occurred in 82% of JIA patients (151 events per 100 PY), 74% of patients with psoriasis (169 events per 100 PY), and 76% of patients with CD (132 events per 100 PY). The most common events for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were injection-site pain (22% of patients; 75 events per 100 PY), headache (30% of patients; 47 events per 100 PY), and worsening of Crohn’s disease (55% of patients; 37 events per 100 PY), respectively.

Serious adverse events occurred in 29% of patients. Rates for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were 14, 7, and 32 events per 100 PY, respectively. Serious infections were the most common serious adverse event, with rates of 3, 1, and 7 events per 100 PY for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease, respectively. Pneumonia was the most commonly reported serious infection (1% of patients; 1 event per 100 PY). One death, due to an accidental fall, occurred in an adolescent patient with psoriasis.

The study findings add to “a more complete understanding of the established safety profile of adalimumab,” and suggest that in pediatric patients, “the overall safety profile was comparable and consistent with that in adults,” Dr. Horneff and his associates added.

AbbVie funded the study. Dr. Horneff has received grants from AbbVie, Chugai, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Seven of the investigators are or were employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock and stock options. Two of the investigators disclosed ties with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Horneff G et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of being “aware of the safety profile of this widely used biologic medication,” Philip J. Hashkes, MD, MSc, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The major finding was that the safety profile is similar to that seen in adults,” he added. “Although almost all patients developed adverse effects, especially infections, most were usual pediatric infections (including the serious infections) with very few opportunistic infections.” Patients with Crohn’s disease had more serious adverse effects and infections.

Future research should go a step further and focus on “post-marketing surveillance in ‘real life’ settings,” he concluded.

Dr. Hashkes is a pediatric rheumatologist at the Cleveland Clinic. His editorial in response to the article by Horneff et al. appeared in the Journal of Pediatrics (J Pediatr. 2018 Oct;201:2-3).

The findings of this study underscore the importance of being “aware of the safety profile of this widely used biologic medication,” Philip J. Hashkes, MD, MSc, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The major finding was that the safety profile is similar to that seen in adults,” he added. “Although almost all patients developed adverse effects, especially infections, most were usual pediatric infections (including the serious infections) with very few opportunistic infections.” Patients with Crohn’s disease had more serious adverse effects and infections.

Future research should go a step further and focus on “post-marketing surveillance in ‘real life’ settings,” he concluded.

Dr. Hashkes is a pediatric rheumatologist at the Cleveland Clinic. His editorial in response to the article by Horneff et al. appeared in the Journal of Pediatrics (J Pediatr. 2018 Oct;201:2-3).

The findings of this study underscore the importance of being “aware of the safety profile of this widely used biologic medication,” Philip J. Hashkes, MD, MSc, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The major finding was that the safety profile is similar to that seen in adults,” he added. “Although almost all patients developed adverse effects, especially infections, most were usual pediatric infections (including the serious infections) with very few opportunistic infections.” Patients with Crohn’s disease had more serious adverse effects and infections.

Future research should go a step further and focus on “post-marketing surveillance in ‘real life’ settings,” he concluded.

Dr. Hashkes is a pediatric rheumatologist at the Cleveland Clinic. His editorial in response to the article by Horneff et al. appeared in the Journal of Pediatrics (J Pediatr. 2018 Oct;201:2-3).

The safety profile for adalimumab in children is similar to that of adults, according to findings published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In an analysis of data from seven clinical trials from 2002-2015, the most common adverse events across indications were upper respiratory tract infection (24 events per 100 patient-years), nasopharyngitis (17 events per 100 PY), and headache (20 events per 100 PY). Serious infections were the most frequent adverse events across indications (8% of all patients; 4 events per 100 PY), reported Gerd Horneff, MD, of the department of general pediatrics at Asklepios Klinik Sankt Augustin (Germany), and his coauthors.

All of the clinical trials were funded by AbbVie, and included 577 pediatric patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease. Patients received subcutaneous injection of adalimumab at a dosage of either 40 mg/0.8 mL or 20 mg/0.4 mL.

Adverse events that occurred after the first adalimumab dose and up to 70 days after the last dose were included. Serious adverse events were defined as “events that were fatal or immediately life-threatening; required inpatient or prolonged hospitalization; resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly, or spontaneous or elective abortion; or required medical or surgical intervention to prevent a serious outcome,” the authors said.

Infections occurred in 82% of JIA patients (151 events per 100 PY), 74% of patients with psoriasis (169 events per 100 PY), and 76% of patients with CD (132 events per 100 PY). The most common events for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were injection-site pain (22% of patients; 75 events per 100 PY), headache (30% of patients; 47 events per 100 PY), and worsening of Crohn’s disease (55% of patients; 37 events per 100 PY), respectively.

Serious adverse events occurred in 29% of patients. Rates for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were 14, 7, and 32 events per 100 PY, respectively. Serious infections were the most common serious adverse event, with rates of 3, 1, and 7 events per 100 PY for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease, respectively. Pneumonia was the most commonly reported serious infection (1% of patients; 1 event per 100 PY). One death, due to an accidental fall, occurred in an adolescent patient with psoriasis.

The study findings add to “a more complete understanding of the established safety profile of adalimumab,” and suggest that in pediatric patients, “the overall safety profile was comparable and consistent with that in adults,” Dr. Horneff and his associates added.

AbbVie funded the study. Dr. Horneff has received grants from AbbVie, Chugai, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Seven of the investigators are or were employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock and stock options. Two of the investigators disclosed ties with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Horneff G et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042.

The safety profile for adalimumab in children is similar to that of adults, according to findings published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

In an analysis of data from seven clinical trials from 2002-2015, the most common adverse events across indications were upper respiratory tract infection (24 events per 100 patient-years), nasopharyngitis (17 events per 100 PY), and headache (20 events per 100 PY). Serious infections were the most frequent adverse events across indications (8% of all patients; 4 events per 100 PY), reported Gerd Horneff, MD, of the department of general pediatrics at Asklepios Klinik Sankt Augustin (Germany), and his coauthors.

All of the clinical trials were funded by AbbVie, and included 577 pediatric patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease. Patients received subcutaneous injection of adalimumab at a dosage of either 40 mg/0.8 mL or 20 mg/0.4 mL.

Adverse events that occurred after the first adalimumab dose and up to 70 days after the last dose were included. Serious adverse events were defined as “events that were fatal or immediately life-threatening; required inpatient or prolonged hospitalization; resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly, or spontaneous or elective abortion; or required medical or surgical intervention to prevent a serious outcome,” the authors said.

Infections occurred in 82% of JIA patients (151 events per 100 PY), 74% of patients with psoriasis (169 events per 100 PY), and 76% of patients with CD (132 events per 100 PY). The most common events for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were injection-site pain (22% of patients; 75 events per 100 PY), headache (30% of patients; 47 events per 100 PY), and worsening of Crohn’s disease (55% of patients; 37 events per 100 PY), respectively.

Serious adverse events occurred in 29% of patients. Rates for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s were 14, 7, and 32 events per 100 PY, respectively. Serious infections were the most common serious adverse event, with rates of 3, 1, and 7 events per 100 PY for JIA, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease, respectively. Pneumonia was the most commonly reported serious infection (1% of patients; 1 event per 100 PY). One death, due to an accidental fall, occurred in an adolescent patient with psoriasis.

The study findings add to “a more complete understanding of the established safety profile of adalimumab,” and suggest that in pediatric patients, “the overall safety profile was comparable and consistent with that in adults,” Dr. Horneff and his associates added.

AbbVie funded the study. Dr. Horneff has received grants from AbbVie, Chugai, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Seven of the investigators are or were employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock and stock options. Two of the investigators disclosed ties with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Horneff G et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The most common adverse events across indications were upper respiratory tract infection (24 events per 100 patient-years), nasopharyngitis (17 events per 100 PY), and headache (20 events per 100 PY).

Study details: An analysis of data for 577 pediatric patients from seven clinical trials between September 2002 and December 2015.

Disclosures: AbbVie funded the study. Dr. Horneff has received grants from AbbVie, Chugai, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Seven of the investigators are or were employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie stock and stock options. Two of the investigators disclosed ties with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Horneff G et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.042.

Eat, toke or vape: Teens not too picky when it comes to pot’s potpourri

There is no doubt that some high school students will try to get high. However, the ways they’re doing it might be changing.