User login

Physical fitness tied to lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease

, new findings suggest. “One exciting finding of this study is that as people’s fitness improved, their risk of Alzheimer’s disease decreased – it was not an all-or-nothing proposition,” study investigator Edward Zamrini, MD, of the Washington DC VA Medical Center, said in a news release.

The findings suggest that people can work toward making incremental changes and improvements in their physical fitness, which may help decrease their risk of dementia, Dr. Zamrini added.

The findings were presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Effective prevention strategy

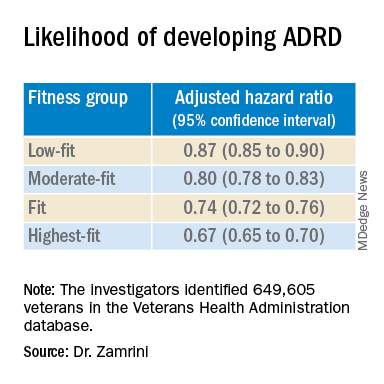

Using the Veterans Health Administration database, Dr. Zamrini and colleagues identified 649,605 veterans (mean age, 61 years) free of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (ADRD) when they completed standardized exercise treadmill tests between 2000 and 2017.

They divided participants into five age-specific fitness groups, from least fit to most fit, based on peak metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved during the treadmill test: lowest-fit (METs, ±3.8), low-fit (METs, ±5.8), moderate-fit (METs, ±7.5), fit (METs, ±9.2), and highest-fit (METs, ±11.7).

In unadjusted analysis, veterans with the lowest cardiorespiratory fitness developed ADRD at a rate of 9.5 cases per 1,000 person-years, compared with a rate of 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years for the most fit group (P < .001).

After adjusting for factors that could affect risk of ADRD, compared with the lowest-fit group, the highest-fit and fit groups were 33% and 26% less likely to develop ADRD, respectively, while the moderate-fit and low-fit groups were 20% and 13% less likely to develop the disease, respectively.

The findings suggest that the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and ADRD risk is “inverse, independent, and graded,” the researchers said in their conference abstract.

“The idea that you can reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s disease by simply increasing your activity is very promising, especially since there are no adequate treatments to prevent or stop the progression of the disease,” Dr. Zamrini added in the news release.

“We hope to develop a simple scale that can be individualized so people can see the benefits that even incremental improvements in fitness can deliver,” he said.

The next vital sign?

Commenting on the study, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Boston, noted that “for decades and with increasing body of support from studies like this, we have known that preventing dementia is based on healthy behaviors for the brain including a proper diet (NASH and/or Mediterranean), exercise regimen (aerobic/cardio more than anaerobic/weight-lifting), sleep hygiene, and social and intellectual engagements.”

“Frankly, what’s good for the body is good for the brain,” said Dr. Lakhan.

“It should be noted that the measure studied here is cardiorespiratory fitness, which has been associated with heart disease and resulting death, death from any cause, and now brain health,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“This powerful predictor may in fact be the next vital sign, after your heart rate and blood pressure, from which your primary care provider can make a personalized treatment plan,” he added.

“Accelerating this process, the ability to measure cardiorespiratory fitness traditionally from huge stationary machines down to wearables like a watch or ring, or even your iPhone or Android, is just on the horizon,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“Instead of tracking just your weight, shape, and BMI, personal fitness may be tailored to optimizing this indicator and further empowering individuals to take charge of their health,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Washington DC VA Medical Center, and George Washington University. Dr. Zamrini and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new findings suggest. “One exciting finding of this study is that as people’s fitness improved, their risk of Alzheimer’s disease decreased – it was not an all-or-nothing proposition,” study investigator Edward Zamrini, MD, of the Washington DC VA Medical Center, said in a news release.

The findings suggest that people can work toward making incremental changes and improvements in their physical fitness, which may help decrease their risk of dementia, Dr. Zamrini added.

The findings were presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Effective prevention strategy

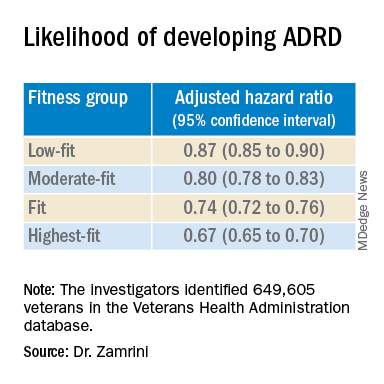

Using the Veterans Health Administration database, Dr. Zamrini and colleagues identified 649,605 veterans (mean age, 61 years) free of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (ADRD) when they completed standardized exercise treadmill tests between 2000 and 2017.

They divided participants into five age-specific fitness groups, from least fit to most fit, based on peak metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved during the treadmill test: lowest-fit (METs, ±3.8), low-fit (METs, ±5.8), moderate-fit (METs, ±7.5), fit (METs, ±9.2), and highest-fit (METs, ±11.7).

In unadjusted analysis, veterans with the lowest cardiorespiratory fitness developed ADRD at a rate of 9.5 cases per 1,000 person-years, compared with a rate of 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years for the most fit group (P < .001).

After adjusting for factors that could affect risk of ADRD, compared with the lowest-fit group, the highest-fit and fit groups were 33% and 26% less likely to develop ADRD, respectively, while the moderate-fit and low-fit groups were 20% and 13% less likely to develop the disease, respectively.

The findings suggest that the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and ADRD risk is “inverse, independent, and graded,” the researchers said in their conference abstract.

“The idea that you can reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s disease by simply increasing your activity is very promising, especially since there are no adequate treatments to prevent or stop the progression of the disease,” Dr. Zamrini added in the news release.

“We hope to develop a simple scale that can be individualized so people can see the benefits that even incremental improvements in fitness can deliver,” he said.

The next vital sign?

Commenting on the study, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Boston, noted that “for decades and with increasing body of support from studies like this, we have known that preventing dementia is based on healthy behaviors for the brain including a proper diet (NASH and/or Mediterranean), exercise regimen (aerobic/cardio more than anaerobic/weight-lifting), sleep hygiene, and social and intellectual engagements.”

“Frankly, what’s good for the body is good for the brain,” said Dr. Lakhan.

“It should be noted that the measure studied here is cardiorespiratory fitness, which has been associated with heart disease and resulting death, death from any cause, and now brain health,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“This powerful predictor may in fact be the next vital sign, after your heart rate and blood pressure, from which your primary care provider can make a personalized treatment plan,” he added.

“Accelerating this process, the ability to measure cardiorespiratory fitness traditionally from huge stationary machines down to wearables like a watch or ring, or even your iPhone or Android, is just on the horizon,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“Instead of tracking just your weight, shape, and BMI, personal fitness may be tailored to optimizing this indicator and further empowering individuals to take charge of their health,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Washington DC VA Medical Center, and George Washington University. Dr. Zamrini and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new findings suggest. “One exciting finding of this study is that as people’s fitness improved, their risk of Alzheimer’s disease decreased – it was not an all-or-nothing proposition,” study investigator Edward Zamrini, MD, of the Washington DC VA Medical Center, said in a news release.

The findings suggest that people can work toward making incremental changes and improvements in their physical fitness, which may help decrease their risk of dementia, Dr. Zamrini added.

The findings were presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Effective prevention strategy

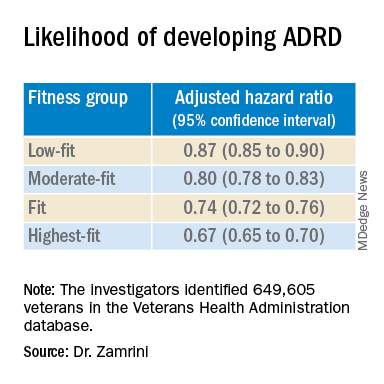

Using the Veterans Health Administration database, Dr. Zamrini and colleagues identified 649,605 veterans (mean age, 61 years) free of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders (ADRD) when they completed standardized exercise treadmill tests between 2000 and 2017.

They divided participants into five age-specific fitness groups, from least fit to most fit, based on peak metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved during the treadmill test: lowest-fit (METs, ±3.8), low-fit (METs, ±5.8), moderate-fit (METs, ±7.5), fit (METs, ±9.2), and highest-fit (METs, ±11.7).

In unadjusted analysis, veterans with the lowest cardiorespiratory fitness developed ADRD at a rate of 9.5 cases per 1,000 person-years, compared with a rate of 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years for the most fit group (P < .001).

After adjusting for factors that could affect risk of ADRD, compared with the lowest-fit group, the highest-fit and fit groups were 33% and 26% less likely to develop ADRD, respectively, while the moderate-fit and low-fit groups were 20% and 13% less likely to develop the disease, respectively.

The findings suggest that the association between cardiorespiratory fitness and ADRD risk is “inverse, independent, and graded,” the researchers said in their conference abstract.

“The idea that you can reduce your risk for Alzheimer’s disease by simply increasing your activity is very promising, especially since there are no adequate treatments to prevent or stop the progression of the disease,” Dr. Zamrini added in the news release.

“We hope to develop a simple scale that can be individualized so people can see the benefits that even incremental improvements in fitness can deliver,” he said.

The next vital sign?

Commenting on the study, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Boston, noted that “for decades and with increasing body of support from studies like this, we have known that preventing dementia is based on healthy behaviors for the brain including a proper diet (NASH and/or Mediterranean), exercise regimen (aerobic/cardio more than anaerobic/weight-lifting), sleep hygiene, and social and intellectual engagements.”

“Frankly, what’s good for the body is good for the brain,” said Dr. Lakhan.

“It should be noted that the measure studied here is cardiorespiratory fitness, which has been associated with heart disease and resulting death, death from any cause, and now brain health,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“This powerful predictor may in fact be the next vital sign, after your heart rate and blood pressure, from which your primary care provider can make a personalized treatment plan,” he added.

“Accelerating this process, the ability to measure cardiorespiratory fitness traditionally from huge stationary machines down to wearables like a watch or ring, or even your iPhone or Android, is just on the horizon,” Dr. Lakhan said.

“Instead of tracking just your weight, shape, and BMI, personal fitness may be tailored to optimizing this indicator and further empowering individuals to take charge of their health,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Washington DC VA Medical Center, and George Washington University. Dr. Zamrini and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAN 2022

Some reproductive factors linked with risk of dementia

Certain reproductive factors are associated with greater or lower risk of dementia, according to researchers who conducted a large population-based study with UK Biobank data.

Jessica Gong, a PhD candidate at the George Institute for Global Health at University of New South Wales in Australia, and coauthors found a greater dementia risk in women with early and late menarche, women who were younger when they first gave birth, and those who had had a hysterectomy, especially those who had a hysterectomy without concomitant oophorectomy or with a previous oophorectomy.

After controlling for key confounders, the researchers found lower risk of all-cause dementia if women had ever been pregnant, ever had an abortion, had a longer reproductive span, or had later menopause.

Use of oral contraceptive pills was associated with a lower dementia risk, they found.

In this study, there was no evidence that hormone therapy (HT) was associated with dementia risk (hazard ratio, 0.99, 95% confidence interval [0.90-1.09], P =.0828).

The analysis, published online April 5 in PLOS Medicine, comprised 273,240 women and 228,957 men without prevalent dementia.

The authors noted that dementia rates are increasing. Globally, 50 million people live with dementia, and the number is expected to triple by 2050, according to Alzheimer’s Disease International.

“Our study identified certain reproductive factors related to shorter exposure to endogenous estrogen were associated with increased risk of dementia, highlighting the susceptibility in dementia risk pertaining to women,” Ms. Gong told this publication.

Risk comparison of men and women

Men were included in this study to compare the association between number of children fathered and the risk of all-cause dementia, with the association in their female counterparts.

The U-shaped associations between the number of children and dementia risk were similar for both sexes, suggesting that the risk difference in women may not be associated with factors associated with childbearing

“It may be more related to social and behavioral factors in parenthood, rather than biological factors involved in childbearing,” Ms. Gong said.

Compared with those with two children, for those without children, the multiple adjusted HR (95% CI) was 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) (P = .027) for women and 1.10 (0.98-1.23) P = .164) for men.

For those with four or more children, the HR was 1.14 (0.98, 1.33) (P = .132) for women and 1.26 (1.10-1.45) (P = .003) for men.

Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant professor of neurology with a dual appointment at Brigham and Women’s and Massachusetts General hospitals in Boston, told this publication she found the comparison of dementia risk with number of children in men and women “fascinating.”

She said the argument usually is that if women have had more births, then they have had more estrogen through their body because women get a huge injection of hormones in pregnancy.

“The idea is that the more pregnancies you have the more protected you are. But this study put that on its head, because if men and women are showing increased [dementia] risk in the number of children they have, it suggests there must be something about having the children – not necessarily the circulating hormones – that might be having an impact,” Dr. Buckley said.

“I had never thought to compare the number of children in men. I do find that very interesting,” she said.

As for the lack of a link between HT and dementia risk, in this study she said, she wouldn’t shut the door on that discussion just yet.

She noted the long history of controversy in the field about whether there is a protective factor against dementia for estrogen or whether exposure to estrogen leads to increased risk.

Before the landmark Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in the 1990s, she pointed out, there was evidence in many observational studies that women who had longer exposure to estrogen – whether that was earlier age at first period and later age at menopause combined or women had taken hormone therapy at some point, had less risk for dementia.

Dr. Buckley said that in a secondary outcome of WHI, however, “there was increased risk for progression to dementia in women who were taking hormone therapy which essentially flipped the field on its ahead because until that point everybody thought that estrogen was a protective factor.”

She said although this study found no association with dementia, she still thinks HT has a role to play and that it may just need to be better tailored to individuals.

“If you think about it, we have our tailored cocktail of hormones in our body and who’s to say that my hormones are going to be the same as yours? Why should you and I be put on the same hormone therapy and assume that will give us the same outcome? I think we could do a lot better with customization and calibration of hormones to aid in women’s health.”

Lifetime approach to dementia

Ms. Gong says future dementia risk-reduction strategies should consider sex-specific risk, and consider the reproductive events that took place in women’s lifespans as well as their entire hormone history when assessing dementia risk, to ensure that the strategies are sex sensitive.

Dr. Buckley agrees: “I don’t think we should ever think about dementia in terms of 65 onwards. We know this disease is insidious and it starts very, very early.”

Regarding limitations, the authors noted that it was a retrospective study that included self-reported measures of reproductive factors, which may be inherently subject to recall bias.

A coauthor does consultant work for Amgen, Freeline, and Kirin outside the submitted work. There were no other relevant financial disclosures.

Certain reproductive factors are associated with greater or lower risk of dementia, according to researchers who conducted a large population-based study with UK Biobank data.

Jessica Gong, a PhD candidate at the George Institute for Global Health at University of New South Wales in Australia, and coauthors found a greater dementia risk in women with early and late menarche, women who were younger when they first gave birth, and those who had had a hysterectomy, especially those who had a hysterectomy without concomitant oophorectomy or with a previous oophorectomy.

After controlling for key confounders, the researchers found lower risk of all-cause dementia if women had ever been pregnant, ever had an abortion, had a longer reproductive span, or had later menopause.

Use of oral contraceptive pills was associated with a lower dementia risk, they found.

In this study, there was no evidence that hormone therapy (HT) was associated with dementia risk (hazard ratio, 0.99, 95% confidence interval [0.90-1.09], P =.0828).

The analysis, published online April 5 in PLOS Medicine, comprised 273,240 women and 228,957 men without prevalent dementia.

The authors noted that dementia rates are increasing. Globally, 50 million people live with dementia, and the number is expected to triple by 2050, according to Alzheimer’s Disease International.

“Our study identified certain reproductive factors related to shorter exposure to endogenous estrogen were associated with increased risk of dementia, highlighting the susceptibility in dementia risk pertaining to women,” Ms. Gong told this publication.

Risk comparison of men and women

Men were included in this study to compare the association between number of children fathered and the risk of all-cause dementia, with the association in their female counterparts.

The U-shaped associations between the number of children and dementia risk were similar for both sexes, suggesting that the risk difference in women may not be associated with factors associated with childbearing

“It may be more related to social and behavioral factors in parenthood, rather than biological factors involved in childbearing,” Ms. Gong said.

Compared with those with two children, for those without children, the multiple adjusted HR (95% CI) was 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) (P = .027) for women and 1.10 (0.98-1.23) P = .164) for men.

For those with four or more children, the HR was 1.14 (0.98, 1.33) (P = .132) for women and 1.26 (1.10-1.45) (P = .003) for men.

Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant professor of neurology with a dual appointment at Brigham and Women’s and Massachusetts General hospitals in Boston, told this publication she found the comparison of dementia risk with number of children in men and women “fascinating.”

She said the argument usually is that if women have had more births, then they have had more estrogen through their body because women get a huge injection of hormones in pregnancy.

“The idea is that the more pregnancies you have the more protected you are. But this study put that on its head, because if men and women are showing increased [dementia] risk in the number of children they have, it suggests there must be something about having the children – not necessarily the circulating hormones – that might be having an impact,” Dr. Buckley said.

“I had never thought to compare the number of children in men. I do find that very interesting,” she said.

As for the lack of a link between HT and dementia risk, in this study she said, she wouldn’t shut the door on that discussion just yet.

She noted the long history of controversy in the field about whether there is a protective factor against dementia for estrogen or whether exposure to estrogen leads to increased risk.

Before the landmark Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in the 1990s, she pointed out, there was evidence in many observational studies that women who had longer exposure to estrogen – whether that was earlier age at first period and later age at menopause combined or women had taken hormone therapy at some point, had less risk for dementia.

Dr. Buckley said that in a secondary outcome of WHI, however, “there was increased risk for progression to dementia in women who were taking hormone therapy which essentially flipped the field on its ahead because until that point everybody thought that estrogen was a protective factor.”

She said although this study found no association with dementia, she still thinks HT has a role to play and that it may just need to be better tailored to individuals.

“If you think about it, we have our tailored cocktail of hormones in our body and who’s to say that my hormones are going to be the same as yours? Why should you and I be put on the same hormone therapy and assume that will give us the same outcome? I think we could do a lot better with customization and calibration of hormones to aid in women’s health.”

Lifetime approach to dementia

Ms. Gong says future dementia risk-reduction strategies should consider sex-specific risk, and consider the reproductive events that took place in women’s lifespans as well as their entire hormone history when assessing dementia risk, to ensure that the strategies are sex sensitive.

Dr. Buckley agrees: “I don’t think we should ever think about dementia in terms of 65 onwards. We know this disease is insidious and it starts very, very early.”

Regarding limitations, the authors noted that it was a retrospective study that included self-reported measures of reproductive factors, which may be inherently subject to recall bias.

A coauthor does consultant work for Amgen, Freeline, and Kirin outside the submitted work. There were no other relevant financial disclosures.

Certain reproductive factors are associated with greater or lower risk of dementia, according to researchers who conducted a large population-based study with UK Biobank data.

Jessica Gong, a PhD candidate at the George Institute for Global Health at University of New South Wales in Australia, and coauthors found a greater dementia risk in women with early and late menarche, women who were younger when they first gave birth, and those who had had a hysterectomy, especially those who had a hysterectomy without concomitant oophorectomy or with a previous oophorectomy.

After controlling for key confounders, the researchers found lower risk of all-cause dementia if women had ever been pregnant, ever had an abortion, had a longer reproductive span, or had later menopause.

Use of oral contraceptive pills was associated with a lower dementia risk, they found.

In this study, there was no evidence that hormone therapy (HT) was associated with dementia risk (hazard ratio, 0.99, 95% confidence interval [0.90-1.09], P =.0828).

The analysis, published online April 5 in PLOS Medicine, comprised 273,240 women and 228,957 men without prevalent dementia.

The authors noted that dementia rates are increasing. Globally, 50 million people live with dementia, and the number is expected to triple by 2050, according to Alzheimer’s Disease International.

“Our study identified certain reproductive factors related to shorter exposure to endogenous estrogen were associated with increased risk of dementia, highlighting the susceptibility in dementia risk pertaining to women,” Ms. Gong told this publication.

Risk comparison of men and women

Men were included in this study to compare the association between number of children fathered and the risk of all-cause dementia, with the association in their female counterparts.

The U-shaped associations between the number of children and dementia risk were similar for both sexes, suggesting that the risk difference in women may not be associated with factors associated with childbearing

“It may be more related to social and behavioral factors in parenthood, rather than biological factors involved in childbearing,” Ms. Gong said.

Compared with those with two children, for those without children, the multiple adjusted HR (95% CI) was 1.18 (1.04, 1.33) (P = .027) for women and 1.10 (0.98-1.23) P = .164) for men.

For those with four or more children, the HR was 1.14 (0.98, 1.33) (P = .132) for women and 1.26 (1.10-1.45) (P = .003) for men.

Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant professor of neurology with a dual appointment at Brigham and Women’s and Massachusetts General hospitals in Boston, told this publication she found the comparison of dementia risk with number of children in men and women “fascinating.”

She said the argument usually is that if women have had more births, then they have had more estrogen through their body because women get a huge injection of hormones in pregnancy.

“The idea is that the more pregnancies you have the more protected you are. But this study put that on its head, because if men and women are showing increased [dementia] risk in the number of children they have, it suggests there must be something about having the children – not necessarily the circulating hormones – that might be having an impact,” Dr. Buckley said.

“I had never thought to compare the number of children in men. I do find that very interesting,” she said.

As for the lack of a link between HT and dementia risk, in this study she said, she wouldn’t shut the door on that discussion just yet.

She noted the long history of controversy in the field about whether there is a protective factor against dementia for estrogen or whether exposure to estrogen leads to increased risk.

Before the landmark Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study in the 1990s, she pointed out, there was evidence in many observational studies that women who had longer exposure to estrogen – whether that was earlier age at first period and later age at menopause combined or women had taken hormone therapy at some point, had less risk for dementia.

Dr. Buckley said that in a secondary outcome of WHI, however, “there was increased risk for progression to dementia in women who were taking hormone therapy which essentially flipped the field on its ahead because until that point everybody thought that estrogen was a protective factor.”

She said although this study found no association with dementia, she still thinks HT has a role to play and that it may just need to be better tailored to individuals.

“If you think about it, we have our tailored cocktail of hormones in our body and who’s to say that my hormones are going to be the same as yours? Why should you and I be put on the same hormone therapy and assume that will give us the same outcome? I think we could do a lot better with customization and calibration of hormones to aid in women’s health.”

Lifetime approach to dementia

Ms. Gong says future dementia risk-reduction strategies should consider sex-specific risk, and consider the reproductive events that took place in women’s lifespans as well as their entire hormone history when assessing dementia risk, to ensure that the strategies are sex sensitive.

Dr. Buckley agrees: “I don’t think we should ever think about dementia in terms of 65 onwards. We know this disease is insidious and it starts very, very early.”

Regarding limitations, the authors noted that it was a retrospective study that included self-reported measures of reproductive factors, which may be inherently subject to recall bias.

A coauthor does consultant work for Amgen, Freeline, and Kirin outside the submitted work. There were no other relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Experimental drug may boost executive function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease

Patients performed better in cognitive testing after just 2 weeks, especially in areas of executive functioning. Clinicians involved in the study also reported improvements in patients’ ability to complete daily activities, especially in complex tasks such as using a computer, carrying out household chores, and managing their medications.

“It’s pretty incredible to see improvement over the course of a week to a week and a half,” said study investigator Aaron Koenig, MD, vice president of Early Clinical Development at Sage Therapeutics in Cambridge, Mass. “Not only are we seeing objective improvement, we’re also seeing a subjective benefit.”

The drug, SAGE-718, is also under study for MCI in patients with Huntington’s disease, the drug’s primary indication, and Parkinson’s disease.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Improved executive function

SAGE-718 is in a new class of drugs called positive allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are thought to improve neuroplasticity.

For the phase 2a open-label LUMINARY trial, researchers enrolled 26 patients ages 50-80 years with Alzheimer’s disease who had MCI. Patients completed a battery of cognitive tests at the study outset, again at the end of treatment, and again after 28 days.

Participants received SAGE-718 daily for 2 weeks and were followed for another 2 weeks.

The study’s primary outcome was safety. Seven patients (26.9%) reported mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), and there were no serious AEs or deaths.

However, after 14 days, researchers also noted improvements from baseline on multiple tests of executive functioning, learning, and memory. And at 28 days, participants demonstrated significantly better Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores, compared with baseline (+2.3 points; P < .05), suggesting improvement in global cognition.

“We know that in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions there is a change in cognition, the ability to think, the ability to do things,” Dr. Koenig said. “What we’ve seen with SAGE-718 to date, all the way back to our phase 1 studies, is a cognitively beneficial effect, but more specifically an improvement in executive functioning.”

Intentional small study design

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, said that because of the small study size, short follow-up, and limited data available in the conference abstract, “we cannot speculate about the efficacy of this investigational therapy.”

“Bigger picture, the real-world clinical meaningfulness of research results that are generated in highly controlled circumstances is an important question that is being discussed right now throughout the Alzheimer’s field,” he added.

However, Dr. Koenig countered that the small study design was intentional. “Over the course of a year, we can get to the answer in different patient populations rather than running these rather large and arduous trials that may pan out to not be positive,” he said.

“The purpose here is to say, directionally, are we seeing improvement that warrants further investigation? If you don’t see an effect in a small number of patients, if you don’t see that effect rather quickly, and if you don’t see an effect that should translate into something meaningful, we at SAGE believe that you may not have a drug there,” he added.

Sage Therapeutics plans to launch a phase 2b placebo-controlled trial later this year to study SAGE-718 in more Alzheimer’s patients over a longer period of time.

The study was funded by SAGE Therapeutics. Dr. Koenig is an employee of SAGE and reports no other conflicts. Dr. Griffin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients performed better in cognitive testing after just 2 weeks, especially in areas of executive functioning. Clinicians involved in the study also reported improvements in patients’ ability to complete daily activities, especially in complex tasks such as using a computer, carrying out household chores, and managing their medications.

“It’s pretty incredible to see improvement over the course of a week to a week and a half,” said study investigator Aaron Koenig, MD, vice president of Early Clinical Development at Sage Therapeutics in Cambridge, Mass. “Not only are we seeing objective improvement, we’re also seeing a subjective benefit.”

The drug, SAGE-718, is also under study for MCI in patients with Huntington’s disease, the drug’s primary indication, and Parkinson’s disease.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Improved executive function

SAGE-718 is in a new class of drugs called positive allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are thought to improve neuroplasticity.

For the phase 2a open-label LUMINARY trial, researchers enrolled 26 patients ages 50-80 years with Alzheimer’s disease who had MCI. Patients completed a battery of cognitive tests at the study outset, again at the end of treatment, and again after 28 days.

Participants received SAGE-718 daily for 2 weeks and were followed for another 2 weeks.

The study’s primary outcome was safety. Seven patients (26.9%) reported mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), and there were no serious AEs or deaths.

However, after 14 days, researchers also noted improvements from baseline on multiple tests of executive functioning, learning, and memory. And at 28 days, participants demonstrated significantly better Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores, compared with baseline (+2.3 points; P < .05), suggesting improvement in global cognition.

“We know that in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions there is a change in cognition, the ability to think, the ability to do things,” Dr. Koenig said. “What we’ve seen with SAGE-718 to date, all the way back to our phase 1 studies, is a cognitively beneficial effect, but more specifically an improvement in executive functioning.”

Intentional small study design

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, said that because of the small study size, short follow-up, and limited data available in the conference abstract, “we cannot speculate about the efficacy of this investigational therapy.”

“Bigger picture, the real-world clinical meaningfulness of research results that are generated in highly controlled circumstances is an important question that is being discussed right now throughout the Alzheimer’s field,” he added.

However, Dr. Koenig countered that the small study design was intentional. “Over the course of a year, we can get to the answer in different patient populations rather than running these rather large and arduous trials that may pan out to not be positive,” he said.

“The purpose here is to say, directionally, are we seeing improvement that warrants further investigation? If you don’t see an effect in a small number of patients, if you don’t see that effect rather quickly, and if you don’t see an effect that should translate into something meaningful, we at SAGE believe that you may not have a drug there,” he added.

Sage Therapeutics plans to launch a phase 2b placebo-controlled trial later this year to study SAGE-718 in more Alzheimer’s patients over a longer period of time.

The study was funded by SAGE Therapeutics. Dr. Koenig is an employee of SAGE and reports no other conflicts. Dr. Griffin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients performed better in cognitive testing after just 2 weeks, especially in areas of executive functioning. Clinicians involved in the study also reported improvements in patients’ ability to complete daily activities, especially in complex tasks such as using a computer, carrying out household chores, and managing their medications.

“It’s pretty incredible to see improvement over the course of a week to a week and a half,” said study investigator Aaron Koenig, MD, vice president of Early Clinical Development at Sage Therapeutics in Cambridge, Mass. “Not only are we seeing objective improvement, we’re also seeing a subjective benefit.”

The drug, SAGE-718, is also under study for MCI in patients with Huntington’s disease, the drug’s primary indication, and Parkinson’s disease.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Improved executive function

SAGE-718 is in a new class of drugs called positive allosteric modulator of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are thought to improve neuroplasticity.

For the phase 2a open-label LUMINARY trial, researchers enrolled 26 patients ages 50-80 years with Alzheimer’s disease who had MCI. Patients completed a battery of cognitive tests at the study outset, again at the end of treatment, and again after 28 days.

Participants received SAGE-718 daily for 2 weeks and were followed for another 2 weeks.

The study’s primary outcome was safety. Seven patients (26.9%) reported mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), and there were no serious AEs or deaths.

However, after 14 days, researchers also noted improvements from baseline on multiple tests of executive functioning, learning, and memory. And at 28 days, participants demonstrated significantly better Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores, compared with baseline (+2.3 points; P < .05), suggesting improvement in global cognition.

“We know that in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions there is a change in cognition, the ability to think, the ability to do things,” Dr. Koenig said. “What we’ve seen with SAGE-718 to date, all the way back to our phase 1 studies, is a cognitively beneficial effect, but more specifically an improvement in executive functioning.”

Intentional small study design

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, said that because of the small study size, short follow-up, and limited data available in the conference abstract, “we cannot speculate about the efficacy of this investigational therapy.”

“Bigger picture, the real-world clinical meaningfulness of research results that are generated in highly controlled circumstances is an important question that is being discussed right now throughout the Alzheimer’s field,” he added.

However, Dr. Koenig countered that the small study design was intentional. “Over the course of a year, we can get to the answer in different patient populations rather than running these rather large and arduous trials that may pan out to not be positive,” he said.

“The purpose here is to say, directionally, are we seeing improvement that warrants further investigation? If you don’t see an effect in a small number of patients, if you don’t see that effect rather quickly, and if you don’t see an effect that should translate into something meaningful, we at SAGE believe that you may not have a drug there,” he added.

Sage Therapeutics plans to launch a phase 2b placebo-controlled trial later this year to study SAGE-718 in more Alzheimer’s patients over a longer period of time.

The study was funded by SAGE Therapeutics. Dr. Koenig is an employee of SAGE and reports no other conflicts. Dr. Griffin has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAN 2022

More evidence that COVID ‘brain fog’ is biologically based

Researchers found elevated levels of CSF immune activation and immunovascular markers in individuals with cognitive postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Patients whose cognitive symptoms developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had the highest levels of brain inflammation.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that suggests the condition often referred to as “brain fog” has a neurologic basis, said lead author Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco Weill Institute of Neurosciences and the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Inflammatory response

There are no effective diagnostic tests or treatments for cognitive PASC, which prompted the investigators to study inflammation in patients with the condition. Initial findings were reported earlier in 2022, which showed abnormalities in the CSF in 77% of patients with cognitive impairment. Patients without cognitive impairments had normal CSF.

Extending that work in this new study, researchers studied patients from the Long-term Impact of Infection With Novel Coronavirus (LIINC) study with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were not hospitalized. They conducted 2-hour neurocognitive interviews and identified 23 people with new, persistent cognitive symptoms (cognitive PASC) and 10 with no cognitive symptoms who served as controls.

All participants underwent additional neurologic examination and neuropsychological testing, and half agreed to a lumbar puncture to allow researchers to collect CSF samples. The CSF was collected a median of 10.2 months after initial COVID symptoms began.

Participants with cognitive PASC had higher median levels of CSF acute phase reactants C-reactive protein (0.007 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P =.004) and serum amyloid A (0.001 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P = .001), compared with COVID controls.

The PASC group also had elevated levels of CSF immune activation markers interferon gamma–inducible protein (IP-10), interleukin-8, and immunovascular markers vascular endothelial growth factor-C and VEGFR-1, although the differences with the control group were not statistically significant.

The timing of the onset of cognitive problems was also associated with higher levels of immune activation and immunovascular markers. Patients with brain fog that developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had higher levels of CSF VEGF-C, compared with patients whose cognitive symptoms developed more than a month after initial COVID symptoms (173 pg/mL vs. 99 pg/mL; P = .048) and COVID controls (79 pg/mL; P = .048).

Acute onset cognitive PASC participants had higher CSF levels of IP-10 (P = .030), IL-8 (P = .048), placental growth factor (P = .030) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (P = .045), compared with COVID controls.

Researchers believe these new findings could mean that intrathecal immune activation and endothelial activation/dysfunction may contribute to cognitive PASC and that the mechanisms involved may be different in patients with acute cognitive PASC versus those with delayed onset.

“Our data suggests that perhaps in these people with more acute cognitive changes they don’t have the return to homeostasis,” Dr. Hellmuth said, while patients with delayed onset cognitive PASC had levels more in line with COVID patients who had no cognitive issues.

Moving the needle forward

Commenting on the findings, William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said that, while the study doesn’t rule out a possible psychological basis for cognitive PASC, it adds more weight to the biological argument.

“When you have nonspecific symptoms for which specific tests are unavailable,” Dr. Schaffner explained, “there is a natural question that always comes up: Is this principally a biologically induced phenomenon or psychological? This moves the needle substantially in the direction of a biological phenomenon.”

Another important element to the study, Dr. Schaffner said, is that the patients involved had mild COVID.

“Not every patient with long COVID symptoms had been hospitalized with severe disease,” he said. “There are inflammatory phenomenon in various organ systems such that even if the inflammatory response in the lung was not severe enough to get you into the hospital, there were inflammatory responses in other organ systems that could persist once the acute infection resolved.”

Although the small size of the study is a limitation, Dr. Schaffner said that shouldn’t minimize the importance of these findings.

“That it’s small doesn’t diminish its value,” he said. “The next step forward might be to try to associate the markers more specifically with COVID. The more precise we can be, the more convincing the story will become.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hellmuth received grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health supporting this work and personal fees for medical-legal consultation outside of the submitted work. Dr. Schaffner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers found elevated levels of CSF immune activation and immunovascular markers in individuals with cognitive postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Patients whose cognitive symptoms developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had the highest levels of brain inflammation.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that suggests the condition often referred to as “brain fog” has a neurologic basis, said lead author Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco Weill Institute of Neurosciences and the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Inflammatory response

There are no effective diagnostic tests or treatments for cognitive PASC, which prompted the investigators to study inflammation in patients with the condition. Initial findings were reported earlier in 2022, which showed abnormalities in the CSF in 77% of patients with cognitive impairment. Patients without cognitive impairments had normal CSF.

Extending that work in this new study, researchers studied patients from the Long-term Impact of Infection With Novel Coronavirus (LIINC) study with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were not hospitalized. They conducted 2-hour neurocognitive interviews and identified 23 people with new, persistent cognitive symptoms (cognitive PASC) and 10 with no cognitive symptoms who served as controls.

All participants underwent additional neurologic examination and neuropsychological testing, and half agreed to a lumbar puncture to allow researchers to collect CSF samples. The CSF was collected a median of 10.2 months after initial COVID symptoms began.

Participants with cognitive PASC had higher median levels of CSF acute phase reactants C-reactive protein (0.007 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P =.004) and serum amyloid A (0.001 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P = .001), compared with COVID controls.

The PASC group also had elevated levels of CSF immune activation markers interferon gamma–inducible protein (IP-10), interleukin-8, and immunovascular markers vascular endothelial growth factor-C and VEGFR-1, although the differences with the control group were not statistically significant.

The timing of the onset of cognitive problems was also associated with higher levels of immune activation and immunovascular markers. Patients with brain fog that developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had higher levels of CSF VEGF-C, compared with patients whose cognitive symptoms developed more than a month after initial COVID symptoms (173 pg/mL vs. 99 pg/mL; P = .048) and COVID controls (79 pg/mL; P = .048).

Acute onset cognitive PASC participants had higher CSF levels of IP-10 (P = .030), IL-8 (P = .048), placental growth factor (P = .030) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (P = .045), compared with COVID controls.

Researchers believe these new findings could mean that intrathecal immune activation and endothelial activation/dysfunction may contribute to cognitive PASC and that the mechanisms involved may be different in patients with acute cognitive PASC versus those with delayed onset.

“Our data suggests that perhaps in these people with more acute cognitive changes they don’t have the return to homeostasis,” Dr. Hellmuth said, while patients with delayed onset cognitive PASC had levels more in line with COVID patients who had no cognitive issues.

Moving the needle forward

Commenting on the findings, William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said that, while the study doesn’t rule out a possible psychological basis for cognitive PASC, it adds more weight to the biological argument.

“When you have nonspecific symptoms for which specific tests are unavailable,” Dr. Schaffner explained, “there is a natural question that always comes up: Is this principally a biologically induced phenomenon or psychological? This moves the needle substantially in the direction of a biological phenomenon.”

Another important element to the study, Dr. Schaffner said, is that the patients involved had mild COVID.

“Not every patient with long COVID symptoms had been hospitalized with severe disease,” he said. “There are inflammatory phenomenon in various organ systems such that even if the inflammatory response in the lung was not severe enough to get you into the hospital, there were inflammatory responses in other organ systems that could persist once the acute infection resolved.”

Although the small size of the study is a limitation, Dr. Schaffner said that shouldn’t minimize the importance of these findings.

“That it’s small doesn’t diminish its value,” he said. “The next step forward might be to try to associate the markers more specifically with COVID. The more precise we can be, the more convincing the story will become.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hellmuth received grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health supporting this work and personal fees for medical-legal consultation outside of the submitted work. Dr. Schaffner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers found elevated levels of CSF immune activation and immunovascular markers in individuals with cognitive postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Patients whose cognitive symptoms developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had the highest levels of brain inflammation.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that suggests the condition often referred to as “brain fog” has a neurologic basis, said lead author Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco Weill Institute of Neurosciences and the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

The findings will be presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Inflammatory response

There are no effective diagnostic tests or treatments for cognitive PASC, which prompted the investigators to study inflammation in patients with the condition. Initial findings were reported earlier in 2022, which showed abnormalities in the CSF in 77% of patients with cognitive impairment. Patients without cognitive impairments had normal CSF.

Extending that work in this new study, researchers studied patients from the Long-term Impact of Infection With Novel Coronavirus (LIINC) study with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were not hospitalized. They conducted 2-hour neurocognitive interviews and identified 23 people with new, persistent cognitive symptoms (cognitive PASC) and 10 with no cognitive symptoms who served as controls.

All participants underwent additional neurologic examination and neuropsychological testing, and half agreed to a lumbar puncture to allow researchers to collect CSF samples. The CSF was collected a median of 10.2 months after initial COVID symptoms began.

Participants with cognitive PASC had higher median levels of CSF acute phase reactants C-reactive protein (0.007 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P =.004) and serum amyloid A (0.001 mg/L vs. 0.000 mg/L; P = .001), compared with COVID controls.

The PASC group also had elevated levels of CSF immune activation markers interferon gamma–inducible protein (IP-10), interleukin-8, and immunovascular markers vascular endothelial growth factor-C and VEGFR-1, although the differences with the control group were not statistically significant.

The timing of the onset of cognitive problems was also associated with higher levels of immune activation and immunovascular markers. Patients with brain fog that developed during the acute phase of COVID-19 had higher levels of CSF VEGF-C, compared with patients whose cognitive symptoms developed more than a month after initial COVID symptoms (173 pg/mL vs. 99 pg/mL; P = .048) and COVID controls (79 pg/mL; P = .048).

Acute onset cognitive PASC participants had higher CSF levels of IP-10 (P = .030), IL-8 (P = .048), placental growth factor (P = .030) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (P = .045), compared with COVID controls.

Researchers believe these new findings could mean that intrathecal immune activation and endothelial activation/dysfunction may contribute to cognitive PASC and that the mechanisms involved may be different in patients with acute cognitive PASC versus those with delayed onset.

“Our data suggests that perhaps in these people with more acute cognitive changes they don’t have the return to homeostasis,” Dr. Hellmuth said, while patients with delayed onset cognitive PASC had levels more in line with COVID patients who had no cognitive issues.

Moving the needle forward

Commenting on the findings, William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said that, while the study doesn’t rule out a possible psychological basis for cognitive PASC, it adds more weight to the biological argument.

“When you have nonspecific symptoms for which specific tests are unavailable,” Dr. Schaffner explained, “there is a natural question that always comes up: Is this principally a biologically induced phenomenon or psychological? This moves the needle substantially in the direction of a biological phenomenon.”

Another important element to the study, Dr. Schaffner said, is that the patients involved had mild COVID.

“Not every patient with long COVID symptoms had been hospitalized with severe disease,” he said. “There are inflammatory phenomenon in various organ systems such that even if the inflammatory response in the lung was not severe enough to get you into the hospital, there were inflammatory responses in other organ systems that could persist once the acute infection resolved.”

Although the small size of the study is a limitation, Dr. Schaffner said that shouldn’t minimize the importance of these findings.

“That it’s small doesn’t diminish its value,” he said. “The next step forward might be to try to associate the markers more specifically with COVID. The more precise we can be, the more convincing the story will become.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Hellmuth received grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health supporting this work and personal fees for medical-legal consultation outside of the submitted work. Dr. Schaffner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAN 2022

Does evidence support benefits of omega-3 fatty acids?

Dietary supplements that contain omega-3 fatty acids have been widely consumed for years. Researchers have been investigating the benefits of such preparations for cardiovascular, neurologic, and psychological conditions. A recently published study on omega-3 fatty acids and depression inspired neurologist Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, PhD, of the Institute for Epidemiology at the University Duisburg-Essen (Germany), to examine scientific publications concerning omega-3 fatty acids or fish-oil capsules in more detail.

Prevention of depression

Dr. Diener told the story of how he stumbled upon an interesting article in JAMA in December 2021. It was about a placebo-controlled study that investigated whether omega-3 fatty acids can prevent incident depression.

As the study authors reported, treatment with omega-3 preparations in adults aged 50 years or older without clinically relevant symptoms of depression at study initiation was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in the risk for depression or clinically relevant symptoms of depression. There was no difference in mood scale value, however, over a median follow-up of 5.3 years. According to the study authors, these results did not support the administration of omega-3 preparations for the prevention of depression.

This study was, as Dr. Diener said, somewhat negative, but it did arouse his interest in questions such as what biological effects omega-3 fatty acids have and what is known “about this topic with regard to neurology,” he said. When reviewing the literature, he noticed that there “were association studies, i.e., studies that describe that the intake of omega-3 fatty acids may possibly be associated with a lower risk of certain diseases.”

Beginning with the Inuit

It all started “with observations of the Inuit [population] in Greenland and Alaska after World War II, because it was remarked upon that these people ate a lot of fish and seal meat and had a very low incidence of cardiovascular diseases.” Over the years, a large number of association studies have been published, which may have encouraged the assumption that omega-3 fatty acids have positive health effects on various conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, various malignancies, cognitive impairments, Alzheimer’s disease, depression and anxiety disorders, heart failure, slipped disks, ADHD, symptoms of menopause, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, periodontitis, epilepsy, chemotherapy tolerance, premenstrual syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Dr. Diener believes that the problem is that these are association studies. But association does not mean that there is a causal relationship.

Disappointing study results

On the contrary, the results from the randomized placebo-controlled studies are truly frustrating, according to the neurologist. A meta-analysis of the use of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular diseases included 86 studies with over 162,000 patients. According to Dr. Diener, it did not reveal any benefit for overall and cardiovascular mortality, nor any benefit for the reduction of myocardial infarction and stroke.

The results did indicate a trend, however, for reduced mortality in coronary heart disease. Even so, the number needed to treat for this was 334, which means that 334 people would have to take omega-3 fatty acids for years to prevent one fatal cardiac event.

Aside from this study, Dr. Diener found six studies on Alzheimer’s disease and three studies on dementia with patient populations between 600 and 800. In these studies, too, a positive effect of omega-3 fatty acids could not be identified. Then he discovered another 31 placebo-controlled studies of omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment or prevention of depression and anxiety disorder. Despite including 50,000 patients, these studies also did not show any positive effect.

“I see a significant discrepancy between the promotion of omega-3 fatty acids, whether it’s on television, in the ‘yellow’ [journalism] press, or in advertisements, and the actual scientific evidence,” said Dr. Diener. “At least from a neurological perspective, there is no evidence that omega-3 fatty acids have any benefit. This is true for strokes, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and anxiety disorders.”

Potential adverse effects

Omega-3 fatty acids also have potentially adverse effects. The VITAL Rhythm study recently provided evidence that, depending on the dose, preparations with omega-3 fatty acids may increase the risk for atrial fibrillation. As the authors wrote, the results do not support taking omega-3 fatty acids to prevent atrial fibrillation.

In 2019, the global market for omega-3 fatty acids reached a value of $4.1 billion. This value is expected to double by 2025, according to a comment by Gregory Curfman, MD, deputy editor of JAMA and lecturer in health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

As Dr. Curfman wrote, this impressive amount of expenditure shows how beloved these products are and how strongly many people believe that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial for their health. It is therefore important to know the potential risks of such preparations. One such example for this would be the risk for atrial fibrillation.

According to Dr. Curfman, in the last 2 years, four randomized clinical studies have provided data on the risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids. In the STRENGTH study, 13,078 high-risk patients with cardiovascular diseases were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The subjects received either a high dose (4 g/day) of a combination of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) or corn oil. After a median of 42 months, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint, but more frequent atrial fibrillation in the omega-3 fatty acid group, compared with the corn oil group (2.2% vs. 1.3%; hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-2.21; P < .001).

In the REDUCE-IT study, 8179 subjects were randomly assigned to a high dose (4 g/day, as in STRENGTH) of an omega-3 fatty acid preparation consisting of a purified EPA (icosapent ethyl) or mineral oil. After a median observation period of 4.9 years, icosapent ethyl was associated with a relative reduction of the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint by 25%, compared with mineral oil. As in the STRENGTH study, this study found that the risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids, compared with mineral oil, was significantly higher (5.3% vs. 3.9%; P = .003).

In a third study (OMEMI), as Dr. Curfman reported, 1027 elderly patients who had recently had a myocardial infarction were randomly assigned to receive either a median dose of 1.8 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids (a combination of EPA and DHA) or corn oil. After 2 years, there was no significant difference between the two groups in primary composite cardiovascular endpoints, but 7.2% of the patients taking omega-3 fatty acids developed atrial fibrillation. In the corn oil group, this proportion was 4% (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.98-3.45; P = .06).

The data from the four studies together indicate a potential dose-dependent risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids, according to Dr. Curfman. At a dose of 4.0 g/day, there is a highly significant risk increase (almost double). With a median dose of 1.8 g/day, the risk increase (HR, 1.84) did not reach statistical significance. At a daily standard dose of 840 mg/day, an increase in risk could not be determined.

Dr. Curfman’s recommendation is that patients who take, or want to take, preparations with omega-3 fatty acids be informed of the potential development of arrhythmia at higher dosages. These patients also should undergo cardiological monitoring.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dietary supplements that contain omega-3 fatty acids have been widely consumed for years. Researchers have been investigating the benefits of such preparations for cardiovascular, neurologic, and psychological conditions. A recently published study on omega-3 fatty acids and depression inspired neurologist Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, PhD, of the Institute for Epidemiology at the University Duisburg-Essen (Germany), to examine scientific publications concerning omega-3 fatty acids or fish-oil capsules in more detail.

Prevention of depression

Dr. Diener told the story of how he stumbled upon an interesting article in JAMA in December 2021. It was about a placebo-controlled study that investigated whether omega-3 fatty acids can prevent incident depression.

As the study authors reported, treatment with omega-3 preparations in adults aged 50 years or older without clinically relevant symptoms of depression at study initiation was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in the risk for depression or clinically relevant symptoms of depression. There was no difference in mood scale value, however, over a median follow-up of 5.3 years. According to the study authors, these results did not support the administration of omega-3 preparations for the prevention of depression.

This study was, as Dr. Diener said, somewhat negative, but it did arouse his interest in questions such as what biological effects omega-3 fatty acids have and what is known “about this topic with regard to neurology,” he said. When reviewing the literature, he noticed that there “were association studies, i.e., studies that describe that the intake of omega-3 fatty acids may possibly be associated with a lower risk of certain diseases.”

Beginning with the Inuit

It all started “with observations of the Inuit [population] in Greenland and Alaska after World War II, because it was remarked upon that these people ate a lot of fish and seal meat and had a very low incidence of cardiovascular diseases.” Over the years, a large number of association studies have been published, which may have encouraged the assumption that omega-3 fatty acids have positive health effects on various conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, various malignancies, cognitive impairments, Alzheimer’s disease, depression and anxiety disorders, heart failure, slipped disks, ADHD, symptoms of menopause, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, periodontitis, epilepsy, chemotherapy tolerance, premenstrual syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Dr. Diener believes that the problem is that these are association studies. But association does not mean that there is a causal relationship.

Disappointing study results

On the contrary, the results from the randomized placebo-controlled studies are truly frustrating, according to the neurologist. A meta-analysis of the use of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular diseases included 86 studies with over 162,000 patients. According to Dr. Diener, it did not reveal any benefit for overall and cardiovascular mortality, nor any benefit for the reduction of myocardial infarction and stroke.

The results did indicate a trend, however, for reduced mortality in coronary heart disease. Even so, the number needed to treat for this was 334, which means that 334 people would have to take omega-3 fatty acids for years to prevent one fatal cardiac event.

Aside from this study, Dr. Diener found six studies on Alzheimer’s disease and three studies on dementia with patient populations between 600 and 800. In these studies, too, a positive effect of omega-3 fatty acids could not be identified. Then he discovered another 31 placebo-controlled studies of omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment or prevention of depression and anxiety disorder. Despite including 50,000 patients, these studies also did not show any positive effect.

“I see a significant discrepancy between the promotion of omega-3 fatty acids, whether it’s on television, in the ‘yellow’ [journalism] press, or in advertisements, and the actual scientific evidence,” said Dr. Diener. “At least from a neurological perspective, there is no evidence that omega-3 fatty acids have any benefit. This is true for strokes, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and anxiety disorders.”

Potential adverse effects

Omega-3 fatty acids also have potentially adverse effects. The VITAL Rhythm study recently provided evidence that, depending on the dose, preparations with omega-3 fatty acids may increase the risk for atrial fibrillation. As the authors wrote, the results do not support taking omega-3 fatty acids to prevent atrial fibrillation.

In 2019, the global market for omega-3 fatty acids reached a value of $4.1 billion. This value is expected to double by 2025, according to a comment by Gregory Curfman, MD, deputy editor of JAMA and lecturer in health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

As Dr. Curfman wrote, this impressive amount of expenditure shows how beloved these products are and how strongly many people believe that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial for their health. It is therefore important to know the potential risks of such preparations. One such example for this would be the risk for atrial fibrillation.

According to Dr. Curfman, in the last 2 years, four randomized clinical studies have provided data on the risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids. In the STRENGTH study, 13,078 high-risk patients with cardiovascular diseases were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The subjects received either a high dose (4 g/day) of a combination of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) or corn oil. After a median of 42 months, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint, but more frequent atrial fibrillation in the omega-3 fatty acid group, compared with the corn oil group (2.2% vs. 1.3%; hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% confidence interval, 1.29-2.21; P < .001).

In the REDUCE-IT study, 8179 subjects were randomly assigned to a high dose (4 g/day, as in STRENGTH) of an omega-3 fatty acid preparation consisting of a purified EPA (icosapent ethyl) or mineral oil. After a median observation period of 4.9 years, icosapent ethyl was associated with a relative reduction of the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint by 25%, compared with mineral oil. As in the STRENGTH study, this study found that the risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids, compared with mineral oil, was significantly higher (5.3% vs. 3.9%; P = .003).

In a third study (OMEMI), as Dr. Curfman reported, 1027 elderly patients who had recently had a myocardial infarction were randomly assigned to receive either a median dose of 1.8 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids (a combination of EPA and DHA) or corn oil. After 2 years, there was no significant difference between the two groups in primary composite cardiovascular endpoints, but 7.2% of the patients taking omega-3 fatty acids developed atrial fibrillation. In the corn oil group, this proportion was 4% (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.98-3.45; P = .06).

The data from the four studies together indicate a potential dose-dependent risk for atrial fibrillation associated with omega-3 fatty acids, according to Dr. Curfman. At a dose of 4.0 g/day, there is a highly significant risk increase (almost double). With a median dose of 1.8 g/day, the risk increase (HR, 1.84) did not reach statistical significance. At a daily standard dose of 840 mg/day, an increase in risk could not be determined.

Dr. Curfman’s recommendation is that patients who take, or want to take, preparations with omega-3 fatty acids be informed of the potential development of arrhythmia at higher dosages. These patients also should undergo cardiological monitoring.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dietary supplements that contain omega-3 fatty acids have been widely consumed for years. Researchers have been investigating the benefits of such preparations for cardiovascular, neurologic, and psychological conditions. A recently published study on omega-3 fatty acids and depression inspired neurologist Hans-Christoph Diener, MD, PhD, of the Institute for Epidemiology at the University Duisburg-Essen (Germany), to examine scientific publications concerning omega-3 fatty acids or fish-oil capsules in more detail.

Prevention of depression

Dr. Diener told the story of how he stumbled upon an interesting article in JAMA in December 2021. It was about a placebo-controlled study that investigated whether omega-3 fatty acids can prevent incident depression.

As the study authors reported, treatment with omega-3 preparations in adults aged 50 years or older without clinically relevant symptoms of depression at study initiation was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in the risk for depression or clinically relevant symptoms of depression. There was no difference in mood scale value, however, over a median follow-up of 5.3 years. According to the study authors, these results did not support the administration of omega-3 preparations for the prevention of depression.

This study was, as Dr. Diener said, somewhat negative, but it did arouse his interest in questions such as what biological effects omega-3 fatty acids have and what is known “about this topic with regard to neurology,” he said. When reviewing the literature, he noticed that there “were association studies, i.e., studies that describe that the intake of omega-3 fatty acids may possibly be associated with a lower risk of certain diseases.”

Beginning with the Inuit

It all started “with observations of the Inuit [population] in Greenland and Alaska after World War II, because it was remarked upon that these people ate a lot of fish and seal meat and had a very low incidence of cardiovascular diseases.” Over the years, a large number of association studies have been published, which may have encouraged the assumption that omega-3 fatty acids have positive health effects on various conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, various malignancies, cognitive impairments, Alzheimer’s disease, depression and anxiety disorders, heart failure, slipped disks, ADHD, symptoms of menopause, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, periodontitis, epilepsy, chemotherapy tolerance, premenstrual syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Dr. Diener believes that the problem is that these are association studies. But association does not mean that there is a causal relationship.

Disappointing study results

On the contrary, the results from the randomized placebo-controlled studies are truly frustrating, according to the neurologist. A meta-analysis of the use of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular diseases included 86 studies with over 162,000 patients. According to Dr. Diener, it did not reveal any benefit for overall and cardiovascular mortality, nor any benefit for the reduction of myocardial infarction and stroke.

The results did indicate a trend, however, for reduced mortality in coronary heart disease. Even so, the number needed to treat for this was 334, which means that 334 people would have to take omega-3 fatty acids for years to prevent one fatal cardiac event.

Aside from this study, Dr. Diener found six studies on Alzheimer’s disease and three studies on dementia with patient populations between 600 and 800. In these studies, too, a positive effect of omega-3 fatty acids could not be identified. Then he discovered another 31 placebo-controlled studies of omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment or prevention of depression and anxiety disorder. Despite including 50,000 patients, these studies also did not show any positive effect.

“I see a significant discrepancy between the promotion of omega-3 fatty acids, whether it’s on television, in the ‘yellow’ [journalism] press, or in advertisements, and the actual scientific evidence,” said Dr. Diener. “At least from a neurological perspective, there is no evidence that omega-3 fatty acids have any benefit. This is true for strokes, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and anxiety disorders.”

Potential adverse effects

Omega-3 fatty acids also have potentially adverse effects. The VITAL Rhythm study recently provided evidence that, depending on the dose, preparations with omega-3 fatty acids may increase the risk for atrial fibrillation. As the authors wrote, the results do not support taking omega-3 fatty acids to prevent atrial fibrillation.

In 2019, the global market for omega-3 fatty acids reached a value of $4.1 billion. This value is expected to double by 2025, according to a comment by Gregory Curfman, MD, deputy editor of JAMA and lecturer in health care policy at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

As Dr. Curfman wrote, this impressive amount of expenditure shows how beloved these products are and how strongly many people believe that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial for their health. It is therefore important to know the potential risks of such preparations. One such example for this would be the risk for atrial fibrillation.