User login

Universal anxiety screening recommendation is a good start

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A very good thing happened this summer for patients with anxiety and the psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals who provide treatment for them. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended anxiety screening for all adults younger than 65.

On the surface, this is a great recommendation for recognition and caring for those who deal with and suffer from an anxiety disorder or multiple anxiety disorders. Although the USPSTF recommendations are independent of the U.S. government and are not an official position of the Department of Health & Human Services, they are a wonderful start at recognizing the importance of mental health care.

After all, anxiety disorders are the most commonly experienced and diagnosed mental disorders, according to the DSM-5.

They range mainly from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), to panic attacks and panic disorder, separation anxiety, specific type phobias (bridges, tunnels, insects, snakes, and the list goes on), to other phobias, including agoraphobia, social phobia, and of course, anxiety caused by medical conditions. GAD alone occurs in, at least, more than 3% of the population.

Those of us who have been treating anxiety disorders for decades recognize them as an issue affecting both mental and physical well-being, not only because of the emotional causes but the physical distress and illnesses that anxiety may precipitate or worsen.

For example, blood pressure– and heart-related issues, GI disorders, and musculoskeletal issues are just a few examples of how our bodies and organ systems are affected by anxiety. Just the momentary physical symptoms of tachycardia or the “runs” before an exam are fine examples of how anxiety may affect patients physically, and an ongoing, consistent anxiety is potentially more harmful.

In fact, a first panic attack or episode of generalized anxiety may be so serious that an emergency department or physician visit is necessary to rule out a heart attack, asthma, or breathing issues – even a hormone or thyroid emergency, or a cardiac arrhythmia. Panic attacks alone create a high number of ED visits.

Treatments mainly include medication management and a variety of psychotherapy techniques. Currently, the most preferred, first-choice medications are the SSRI antidepressants, which are Food and Drug Administration approved for anxiety as well. These include Zoloft (sertraline), Prozac/Sarafem (fluoxetine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram).

For many years, benzodiazepines (that is, tranquillizers) such as Valium (diazepam), Ativan (lorazepam), and Klonopin/Rivotril (clonazepam) to name a few, were the mainstay of anxiety treatment, but they have proven addictive and may affect cognition and memory. As the current opioid epidemic has shown, when combined with opioids, benzodiazepines are a potentially lethal combination and when used, they need to be for shorter-term care and monitored very judiciously.

It should be noted that after ongoing long-term use of an SSRI for anxiety or depression, it should not be stopped abruptly, as a variety of physical symptoms (for example, flu-like symptoms) may occur.

Benefits of nonmedicinal therapies

There are a variety of talk therapies, from dynamic psychotherapies to cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT), plus relaxation techniques and guided imagery that have all had a good amount of success in treating generalized anxiety, panic disorder, as well as various types of phobias.

When medications are stopped, the anxiety symptoms may well return. But when using nonmedicinal therapies, clinicians have discovered that when patients develop a new perspective on the anxiety problem or have a new technique to treat anxiety, it may well be long lasting.

For me, using CBT, relaxation techniques, hypnosis, and guided imagery has been very successful in treating anxiety disorders with long-lasting results. Once a person learns to relax, whether it’s from deep breathing exercises, hypnosis (which is not sleep), mindfulness, or meditation, a strategy of guided imagery can be taught, which allows a person to practice as well as control their anxiety as a lifetime process. For example, I like imagining a large movie screen to desensitize and project anxieties.

In many instances, a combination of a medication and a talk therapy approach works best, but there are an equal number of instances in which just medication or just talk therapy is needed. Once again, knowledge, clinical judgment, and the art of care are required to make these assessments.

In other words, recognizing and treating anxiety requires highly specialized training, which is why I thought the USPSTF recommendations raise a few critical questions.

Questions and concerns

One issue, of course, is the exclusion of those patients over age 65 because of a lack of “data.” Why such an exclusion? Does this mean that data are lacking for this age group?

The concept of using solely evidenced-based data in psychiatry is itself an interesting concept because our profession, like many other medical specialties, requires practitioners to use a combination of art and science. And much can be said either way about the clarity of accuracy in the diversity of issues that arise when treating emotional disorders.

When looking at the over-65 population, has anyone thought of clinical knowledge, judgment, experience, observation, and, of course, common sense?

Just consider the worry (a cardinal feature of anxiety) that besets people over 65 when it comes to issues such as retirement, financial security, “empty nesting,” physical health issues, decreased socialization that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perpetual loss of relatives and friends.

In addition, as we age, anxiety can come simply from the loss of identity as active lifestyles decrease and the reality of nearing life’s end becomes more of a reality. It would seem that this population would benefit enormously from anxiety screening and possible treatment.

Another major concern is that the screening and potential treatment of patients is aimed at primary care physicians. Putting the sole responsibility of providing mental health care on these overworked PCPs defies common sense unless we’re okay with 1- to 2-minute assessments of mental health issues and no doubt, a pharmacology-only approach.

If this follows the same route as well-intentioned PCPs treating depression, where 5-minute medication management is far too common, the only proper diagnostic course – the in-depth interview necessary to make a proper diagnosis – is often missing.

For example, in depression alone, it takes psychiatric experience and time to differentiate a major depressive disorder from a bipolar depression and to provide the appropriate medication and treatment plan with careful follow-up. In my experience, this usually does not happen in the exceedingly overworked, time-driven day of a PCP.

Anxiety disorders and depression can prove debilitating, and if a PCP wants the responsibility of treatment, a mandated mental health program should be followed – just as here in New York, prescribers are mandated to take a pain control, opioid, and infection control CME course to keep our licenses up to date.

Short of mandating a mental health program for PCPs, it should be part of training and CME courses that Psychiatry is a super specialty, much like orthopedics and ophthalmology, and primary care physicians should never hesitate to make referrals to the specialist.

The big picture for me, and I hope for us all, is that the USPSTF has started things rolling by making it clear that PCPs and other health care clinicians need to screen for anxiety as a disabling disorder that is quite treatable.

This approach will help to advance the destigmatization of mental health disorders. But as result, with more patients diagnosed, there will be a need for more psychiatrists – and psychologists with PhDs or PsyDs – to fill the gaps in mental health care.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Barbie has an anxiety disorder

And it’s a great time to be a therapist

The Barbie movie is generating a lot of feelings, ranging from praise to vitriol. However one feels about the movie, let’s all pause and reflect for a moment on the fact that the number-one grossing film of 2023 is about our childhood doll trying to treat her anxiety disorder.

“Life imitates art more than art imitates life.” So said Oscar Wilde in 1889.

When my adult daughter, a childhood Barbie enthusiast, asked me to see the film, we put on pink and went. Twice. Little did I know that it would stir up so many thoughts and feelings. The one I want to share is how blessed I feel at this moment in time to be a mental health care provider! No longer is mental health something to be whispered about at the water cooler; instead, even Barbie is suffering. And with all the controversy in the press about the movie, no one seems at all surprised by this storyline.

I was raised by two child psychiatrists and have been practicing as an adult psychiatrist since 1991. The start of the pandemic was the most difficult time of my career, as almost every patient was struggling simultaneously, as was I. Three long years later, we are gradually emerging from our shared trauma. How ironic, now with the opportunity to go back to work, I have elected to maintain the majority of my practice online from home. It seems that most patients and providers prefer this mode of treatment, with a full 90 percent of practitioners saying they are using a hybrid model.

As mental health professionals, we know that anywhere from 3% to 49% of those experiencing trauma will develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and we have been trained to treat them.

But what happens when an entire global population is exposed simultaneously to trauma? Historians and social scientists refer to such events by many different names, such as: Singularity, Black Swan Event, and Tipping Point. These events are incredibly rare, and afterwards everything is different. These global traumas always lead to massive change.

I think we are at that tipping point. This is the singularity. This is our Black Swan Event. Within a 3-year span, we have experienced the following:

- A global traumatic event (COVID-19).

- A sudden and seemingly permanent shift from office to remote video meetings mostly from home.

- Upending of traditional fundamentals of the stock market as the game literally stopped in January 2021.

- Rapid and widespread availability of Artificial Intelligence.

- The first generation to be fully raised on the Internet and social media (Gen Z) is now entering the workforce.

- Ongoing war in Ukraine.

That’s already an overwhelming list, and I could go on, but let’s get back to Barbie’s anxiety disorder.

The awareness about and acceptance of mental health issues has never been higher. The access to treatment never greater. There are now more online therapy options than ever. Treatment options have dramatically expanded in recent years, from Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) to ketamine centers and psychedelics, as well as more mainstream options such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and so many more.

What is particularly unique about this moment is the direct access to care. Self-help books abound with many making it to the New York Times bestseller list. YouTube is loaded with fantastic content on overcoming many mental health issues, although one should be careful with selecting reliable sources. Apps like HeadSpace and Calm are being downloaded by millions of people around the globe. Investors provided a record-breaking $1.5 billion to mental health startups in 2020 alone.

For most practitioners, our phones have been ringing off the hook since 2020. Applications to psychology, psychiatric residency, social work, and counseling degree programs are on the rise, with workforce shortages expected to continue for decades. Psychological expertise has been embraced by businesses especially for DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion). Mental health experts are the most asked-for experts through media request services. Elite athletes are talking openly about bringing us on their teams.

In this unique moment, when everything seems set to transform into something else, it is time for mental health professionals to exert some agency and influence over where mental health will go from here. I think the next frontier for mental health specialists is to figure out how to speak collectively and help guide society.

Neil Howe, in his sweeping book “The Fourth Turning is Here,” says we have another 10 years in this “Millennial Crisis” phase. He calls this our “winter,” and it remains to be seen how we will emerge from our current challenges. I think we can make a difference.

If the Barbie movie is indeed a canary in the coal mine, I see positive trends ahead as we move past some of the societal and structural issues facing us, and work together to create a more open and egalitarian society. We must find creative solutions that will solve truly massive problems threatening our well-being and perhaps even our existence.

I am so grateful to be able to continue to practice and share my thoughts with you here from my home office, and I hope you can take a break and see this movie, which is not only entertaining but also thought- and emotion-provoking.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

And it’s a great time to be a therapist

And it’s a great time to be a therapist

The Barbie movie is generating a lot of feelings, ranging from praise to vitriol. However one feels about the movie, let’s all pause and reflect for a moment on the fact that the number-one grossing film of 2023 is about our childhood doll trying to treat her anxiety disorder.

“Life imitates art more than art imitates life.” So said Oscar Wilde in 1889.

When my adult daughter, a childhood Barbie enthusiast, asked me to see the film, we put on pink and went. Twice. Little did I know that it would stir up so many thoughts and feelings. The one I want to share is how blessed I feel at this moment in time to be a mental health care provider! No longer is mental health something to be whispered about at the water cooler; instead, even Barbie is suffering. And with all the controversy in the press about the movie, no one seems at all surprised by this storyline.

I was raised by two child psychiatrists and have been practicing as an adult psychiatrist since 1991. The start of the pandemic was the most difficult time of my career, as almost every patient was struggling simultaneously, as was I. Three long years later, we are gradually emerging from our shared trauma. How ironic, now with the opportunity to go back to work, I have elected to maintain the majority of my practice online from home. It seems that most patients and providers prefer this mode of treatment, with a full 90 percent of practitioners saying they are using a hybrid model.

As mental health professionals, we know that anywhere from 3% to 49% of those experiencing trauma will develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and we have been trained to treat them.

But what happens when an entire global population is exposed simultaneously to trauma? Historians and social scientists refer to such events by many different names, such as: Singularity, Black Swan Event, and Tipping Point. These events are incredibly rare, and afterwards everything is different. These global traumas always lead to massive change.

I think we are at that tipping point. This is the singularity. This is our Black Swan Event. Within a 3-year span, we have experienced the following:

- A global traumatic event (COVID-19).

- A sudden and seemingly permanent shift from office to remote video meetings mostly from home.

- Upending of traditional fundamentals of the stock market as the game literally stopped in January 2021.

- Rapid and widespread availability of Artificial Intelligence.

- The first generation to be fully raised on the Internet and social media (Gen Z) is now entering the workforce.

- Ongoing war in Ukraine.

That’s already an overwhelming list, and I could go on, but let’s get back to Barbie’s anxiety disorder.

The awareness about and acceptance of mental health issues has never been higher. The access to treatment never greater. There are now more online therapy options than ever. Treatment options have dramatically expanded in recent years, from Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) to ketamine centers and psychedelics, as well as more mainstream options such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and so many more.

What is particularly unique about this moment is the direct access to care. Self-help books abound with many making it to the New York Times bestseller list. YouTube is loaded with fantastic content on overcoming many mental health issues, although one should be careful with selecting reliable sources. Apps like HeadSpace and Calm are being downloaded by millions of people around the globe. Investors provided a record-breaking $1.5 billion to mental health startups in 2020 alone.

For most practitioners, our phones have been ringing off the hook since 2020. Applications to psychology, psychiatric residency, social work, and counseling degree programs are on the rise, with workforce shortages expected to continue for decades. Psychological expertise has been embraced by businesses especially for DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion). Mental health experts are the most asked-for experts through media request services. Elite athletes are talking openly about bringing us on their teams.

In this unique moment, when everything seems set to transform into something else, it is time for mental health professionals to exert some agency and influence over where mental health will go from here. I think the next frontier for mental health specialists is to figure out how to speak collectively and help guide society.

Neil Howe, in his sweeping book “The Fourth Turning is Here,” says we have another 10 years in this “Millennial Crisis” phase. He calls this our “winter,” and it remains to be seen how we will emerge from our current challenges. I think we can make a difference.

If the Barbie movie is indeed a canary in the coal mine, I see positive trends ahead as we move past some of the societal and structural issues facing us, and work together to create a more open and egalitarian society. We must find creative solutions that will solve truly massive problems threatening our well-being and perhaps even our existence.

I am so grateful to be able to continue to practice and share my thoughts with you here from my home office, and I hope you can take a break and see this movie, which is not only entertaining but also thought- and emotion-provoking.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

The Barbie movie is generating a lot of feelings, ranging from praise to vitriol. However one feels about the movie, let’s all pause and reflect for a moment on the fact that the number-one grossing film of 2023 is about our childhood doll trying to treat her anxiety disorder.

“Life imitates art more than art imitates life.” So said Oscar Wilde in 1889.

When my adult daughter, a childhood Barbie enthusiast, asked me to see the film, we put on pink and went. Twice. Little did I know that it would stir up so many thoughts and feelings. The one I want to share is how blessed I feel at this moment in time to be a mental health care provider! No longer is mental health something to be whispered about at the water cooler; instead, even Barbie is suffering. And with all the controversy in the press about the movie, no one seems at all surprised by this storyline.

I was raised by two child psychiatrists and have been practicing as an adult psychiatrist since 1991. The start of the pandemic was the most difficult time of my career, as almost every patient was struggling simultaneously, as was I. Three long years later, we are gradually emerging from our shared trauma. How ironic, now with the opportunity to go back to work, I have elected to maintain the majority of my practice online from home. It seems that most patients and providers prefer this mode of treatment, with a full 90 percent of practitioners saying they are using a hybrid model.

As mental health professionals, we know that anywhere from 3% to 49% of those experiencing trauma will develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and we have been trained to treat them.

But what happens when an entire global population is exposed simultaneously to trauma? Historians and social scientists refer to such events by many different names, such as: Singularity, Black Swan Event, and Tipping Point. These events are incredibly rare, and afterwards everything is different. These global traumas always lead to massive change.

I think we are at that tipping point. This is the singularity. This is our Black Swan Event. Within a 3-year span, we have experienced the following:

- A global traumatic event (COVID-19).

- A sudden and seemingly permanent shift from office to remote video meetings mostly from home.

- Upending of traditional fundamentals of the stock market as the game literally stopped in January 2021.

- Rapid and widespread availability of Artificial Intelligence.

- The first generation to be fully raised on the Internet and social media (Gen Z) is now entering the workforce.

- Ongoing war in Ukraine.

That’s already an overwhelming list, and I could go on, but let’s get back to Barbie’s anxiety disorder.

The awareness about and acceptance of mental health issues has never been higher. The access to treatment never greater. There are now more online therapy options than ever. Treatment options have dramatically expanded in recent years, from Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) to ketamine centers and psychedelics, as well as more mainstream options such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and so many more.

What is particularly unique about this moment is the direct access to care. Self-help books abound with many making it to the New York Times bestseller list. YouTube is loaded with fantastic content on overcoming many mental health issues, although one should be careful with selecting reliable sources. Apps like HeadSpace and Calm are being downloaded by millions of people around the globe. Investors provided a record-breaking $1.5 billion to mental health startups in 2020 alone.

For most practitioners, our phones have been ringing off the hook since 2020. Applications to psychology, psychiatric residency, social work, and counseling degree programs are on the rise, with workforce shortages expected to continue for decades. Psychological expertise has been embraced by businesses especially for DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion). Mental health experts are the most asked-for experts through media request services. Elite athletes are talking openly about bringing us on their teams.

In this unique moment, when everything seems set to transform into something else, it is time for mental health professionals to exert some agency and influence over where mental health will go from here. I think the next frontier for mental health specialists is to figure out how to speak collectively and help guide society.

Neil Howe, in his sweeping book “The Fourth Turning is Here,” says we have another 10 years in this “Millennial Crisis” phase. He calls this our “winter,” and it remains to be seen how we will emerge from our current challenges. I think we can make a difference.

If the Barbie movie is indeed a canary in the coal mine, I see positive trends ahead as we move past some of the societal and structural issues facing us, and work together to create a more open and egalitarian society. We must find creative solutions that will solve truly massive problems threatening our well-being and perhaps even our existence.

I am so grateful to be able to continue to practice and share my thoughts with you here from my home office, and I hope you can take a break and see this movie, which is not only entertaining but also thought- and emotion-provoking.

Dr. Ritvo has almost 30 years’ experience in psychiatry and is currently practicing telemedicine. She is the author of “Bekindr – The Transformative Power of Kindness” (Hellertown, Pa.: Momosa Publishing, 2018). She has no conflicts of interest.

Climate change and mental illness: What psychiatrists can do

“ Hope is engagement with the act of mapping our destinies.” 1

—Valerie Braithwaite

Why should psychiatrists care about climate change and try to mitigate its effects? First, we are tasked by society with managing the psychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae from disasters, which include climate change. The American Psychiatric Association’s position statement on climate change includes it as a legitimate focus for our specialty.2 Second, as physicians, we are morally obligated to do no harm. Since the health care sector contributes significantly to climate change (8.5% of national carbon emissions stem from health care) and causes demonstrable health impacts,3 managing these impacts and decarbonizing the health care industry is morally imperative.4 And third, psychiatric clinicians have transferrable skills that can address fears of climate change, challenge climate change denialism,5 motivate people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors, and help communities not only endure the emotional impact of climate change but become more psychologically resilient.6

Most psychiatrists, however, did not receive formal training on climate change and the related field of disaster preparedness. For example, Harvard Medical School did not include a course on climate change in their medical student curriculum until 2023.7 In this article, we provide a basic framework of climate change and its impact on mental health, with particular focus on patients with serious mental illness (SMI). We offer concrete steps clinicians can take to prevent or mitigate harm from climate change for their patients, prepare for disasters at the level of individual patient encounters, and strengthen their clinics and communities. We also encourage clinicians to take active leadership roles in their professional organizations to be part of climate solutions, building on the trust patients continue to have in their physicians.8 Even if clinicians do not view climate change concerns under their conceived clinical care mandate, having a working knowledge about it is important because patients, paraprofessional staff, or medical trainees are likely to bring it up.9

Climate change and mental health

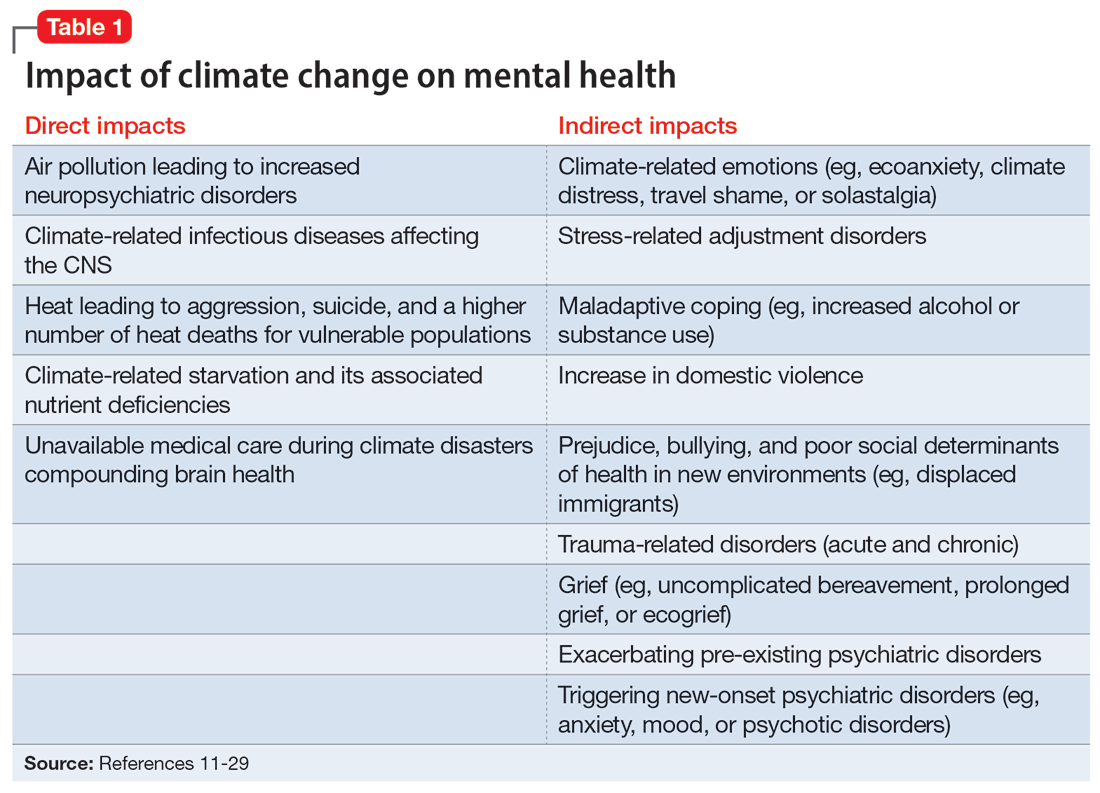

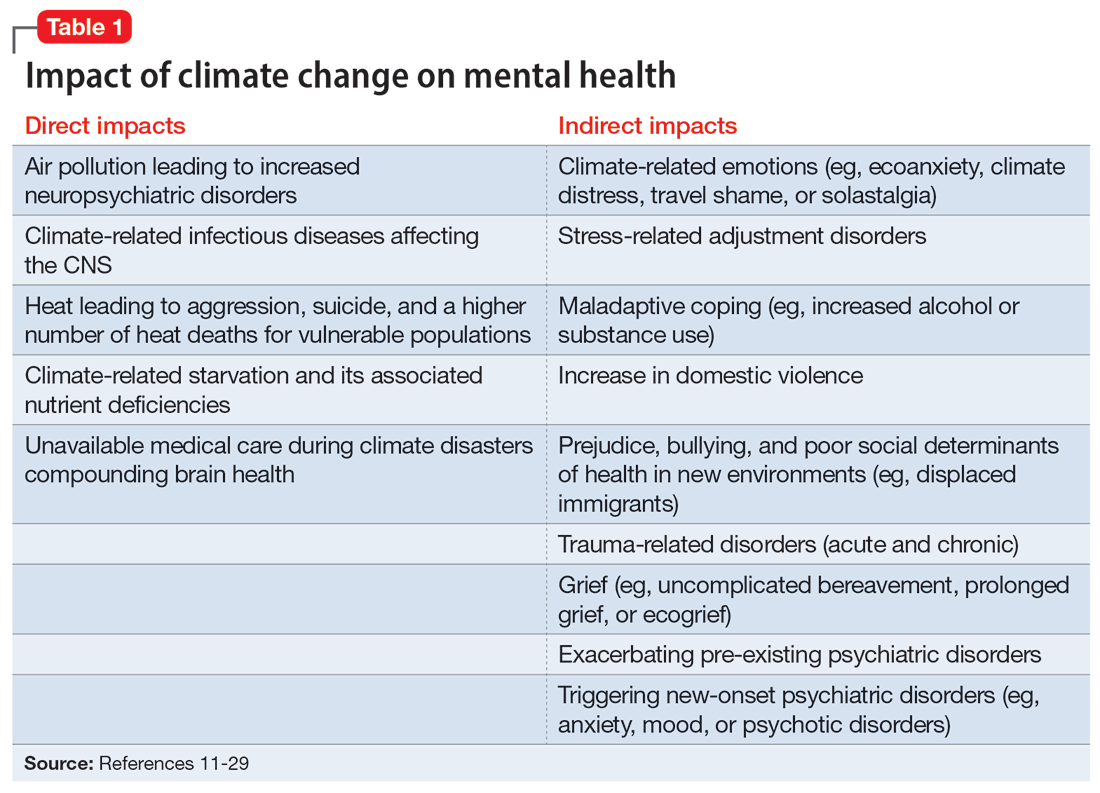

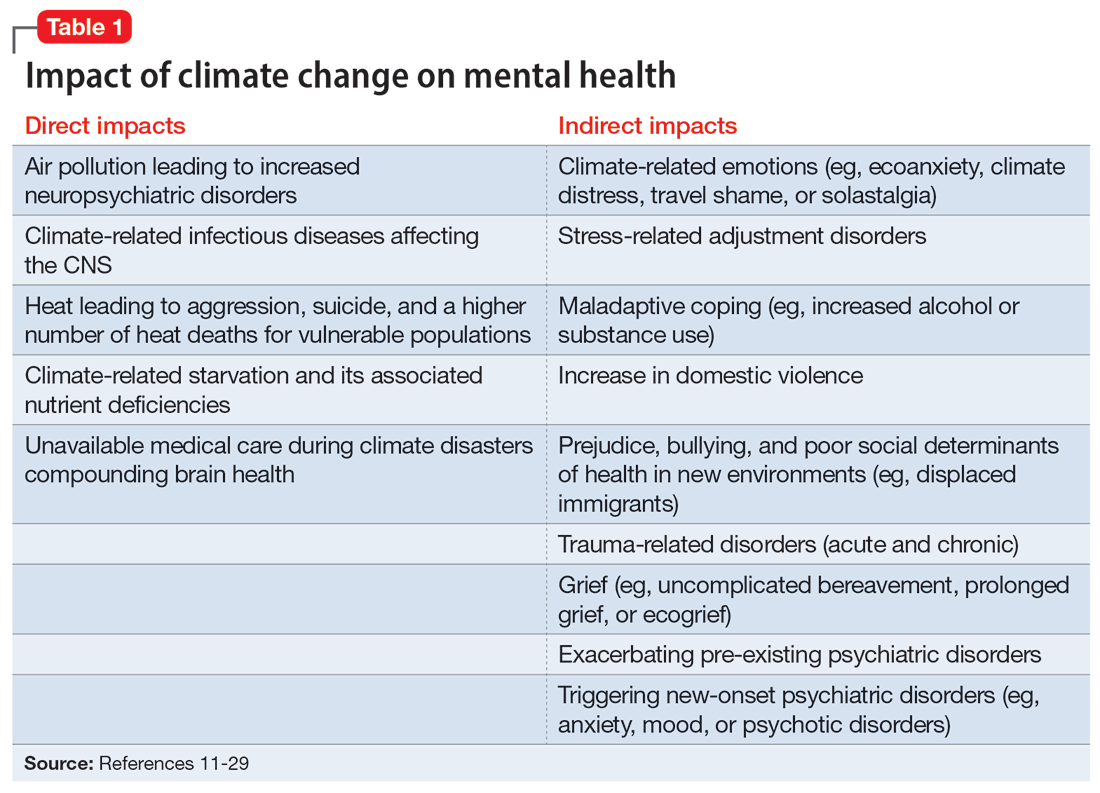

Climate change is harmful to human health, including mental health.10 It can impact mental health directly via its impact on brain function and neuropsychiatric sequelae, and indirectly via climate-related disasters leading to acute or chronic stress, losses, and displacement with psychiatric and psychological sequelae (Table 111-29).

Direct impact

The effects of air pollution, heat, infections, and starvation are examples of how climate change directly impacts mental health. Air pollution and brain health are a concern for psychiatry, given the well-described effects of air deterioration on the developing brain.11 In animal models, airborne pollutants lead to widespread neuroinflammation and cell loss via a multitude of mechanisms.12 This is consistent with worse cognitive and behavioral functions across a wide range of cognitive domains seen in children exposed to pollution compared to those who grew up in environments with healthy air.13 Even low-level exposure to air pollution increases the risk for later onset of depression, suicide, and anxiety.14 Hippocampal atrophy observed in patients with first-episode psychosis may also be partially attributable to air pollution.15 An association between heat and suicide (and to a lesser extent, aggression) has also been reported.16

Worse physical health (eg, strokes) due to excessive heat can further compound mental health via elevated rates of depression. Data from the United States and Mexico show that for each degree Celsius increase in ambient temperature, suicide rates may increase by approximately 1%.17 A meta-analysis by Frangione et al18 similarly concluded that each degree Celsius increase results in an overall risk ratio of 1.016 (95% CI, 1.012 to 1.019) for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. Additionally, global warming is shifting the endemic areas for many infectious agents, particularly vector-borne diseases,19 to regions in which they had hitherto been unknown, increasing the risk for future outbreaks and even pandemics.20 These infectious illnesses often carry neuropsychiatric morbidity, with seizures, encephalopathy with incomplete recovery, and psychiatric syndromes occurring in many cases. Crop failure can lead to starvation during pregnancy and childhood, which has wide-ranging consequences for brain development and later physical and psychological health in adults.21,22 Mothers affected by starvation also experience negative impacts on childbearing and childrearing.23

Indirect impact

Climate change’s indirect impact on mental health can stem from the stress of living through a disaster such as an extreme weather event; from losses, including the death of friends and family members; and from becoming temporarily displaced.24 Some climate change–driven disasters can be viewed as slow-moving, such as drought and the rising of sea levels, where displacement becomes permanent. Managing mass migration from internally or externally displaced people who must abandon their communities because of climate change will have significant repercussions for all societies.25 The term “climate refugee” is not (yet) included in the United Nations’ official definition of refugees; it defines refugees as individuals who have fled their countries because of war, violence, or persecution.26 These and other bureaucratic issues can come up when clinicians are trying to help migrants with immigration-related paperwork.

Continue to: As the inevitability of climate change...

As the inevitability of climate change sinks in, its long-term ramifications have introduced a new lexicon of psychological suffering related to the crisis.27 Common terms for such distress include ecoanxiety (fear of what is happening and will happen with climate change), ecogrief (sadness about the destruction of species and natural habitats), solastalgia28 (the nostalgia an individual feels for emotionally treasured landscapes that have changed), and terrafuria or ecorage (the reaction to betrayal and inaction by governments and leaders).29 Climate-related emotions can lead to pessimism about the future and a nihilistic outlook on an individual’s ability to effect change and have agency over their life’s outcomes.

The categories of direct and indirect impacts are not mutually exclusive. A child may be starving due to weather-related crop failure as the family is forced to move to another country, then have to contend with prejudice and bullying as an immigrant, and later become anxiously preoccupied with climate change and its ability to cause further distress.

Effect on individuals with serious mental illness

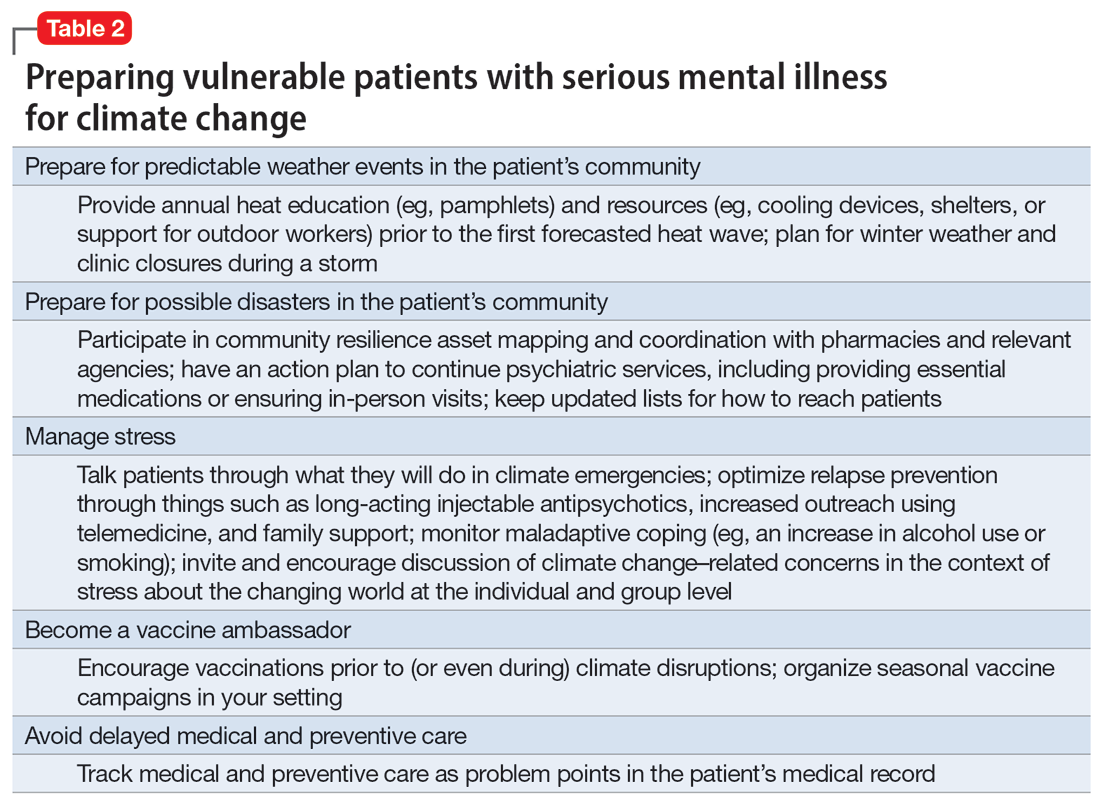

Patients with SMI are particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. They are less resilient to climate change–related events, such as heat waves or temporary displacement from flooding, both at the personal level due to illness factors (eg, negative symptoms or cognitive impairment) and at the community level due to social factors (eg, weaker social support or poverty).

Recognizing the increased vulnerability to heat waves and preparing for them is particularly important for patients with SMI because they are at an increased risk for heat-related illnesses.30 For example, patients may not appreciate the danger from heat and live in conditions that put them at risk (ie, not having air conditioning in their home or living alone). Their illness alone impairs heat regulation31; patients with depression and anxiety also dissipate heat less effectively.32,33 Additionally, many psychiatric medications, particularly antipsychotics, impair key mechanisms of heat dissipation.34,35 Antipsychotics render organisms more poikilothermic (susceptible to environmental temperature, like cold-blooded animals) and can be anticholinergic, which impedes sweating. A recent analysis of heat-related deaths during a period of extreme and prolonged heat in British Columbia in 2021 affirmed these concerns, reporting that patients with schizophrenia had the highest odds of death during this heat-related event.36

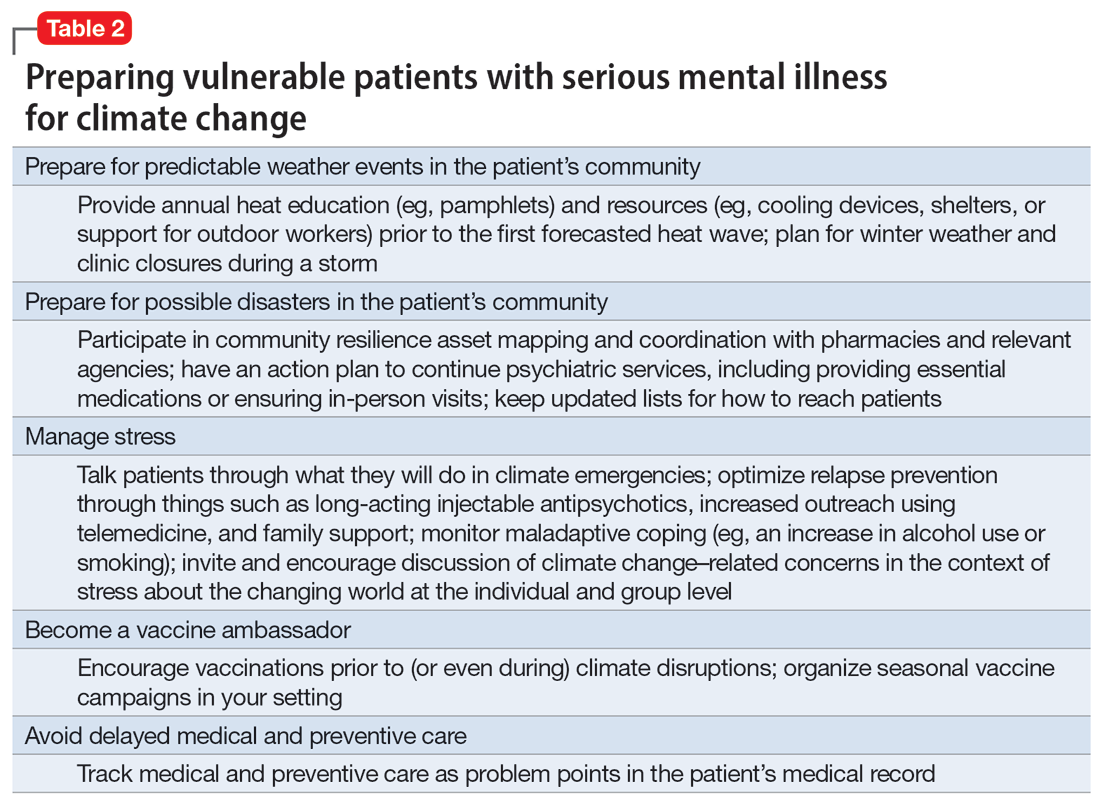

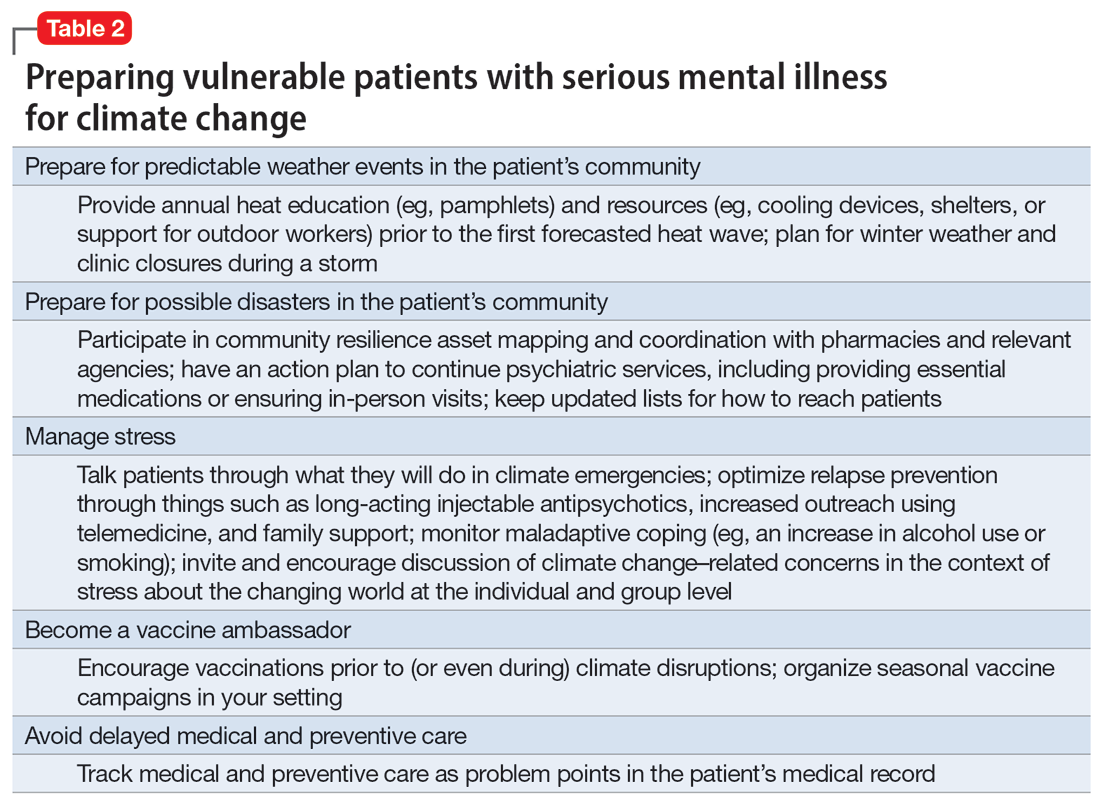

COVID-19 has shown that flexible models of care are needed to prevent disengagement from medical and psychiatric care37 and assure continued treatment with essential medications such as clozapine38 and long-acting injectable antipsychotics39 during periods of social change, as with climate change. While telehealth was critical during the COVID-19 pandemic40 and is here to stay, it alone may be insufficient given the digital divide (patients with SMI may be less likely to have access to or be proficient in the use of digital technologies). The pandemic has shown the importance of public health efforts, including benefits from targeted outreach, with regards to vaccinations for this patient group.41,42 Table 2 summarizes things clinicians should consider when preparing patients with SMI for the effects of climate change.

Continue to: The psychiatrist's role

The psychiatrist’s role

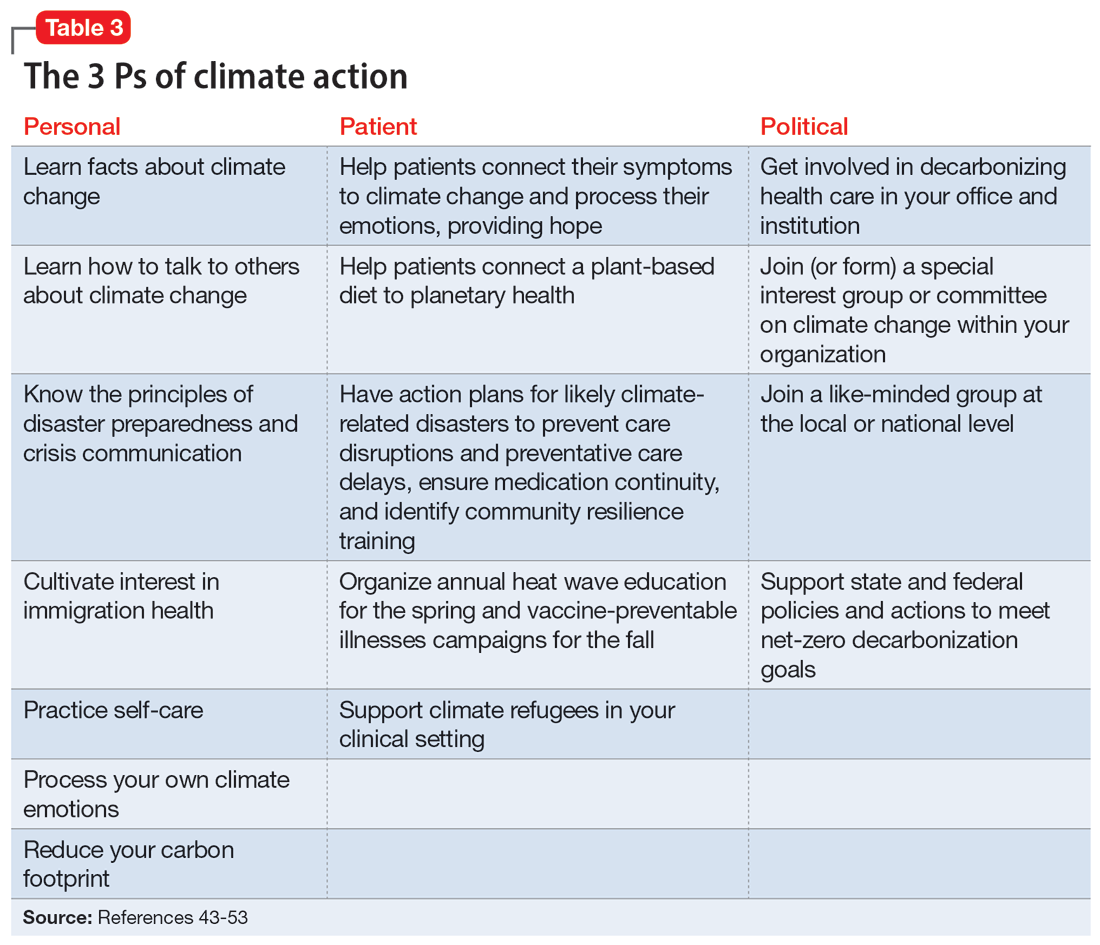

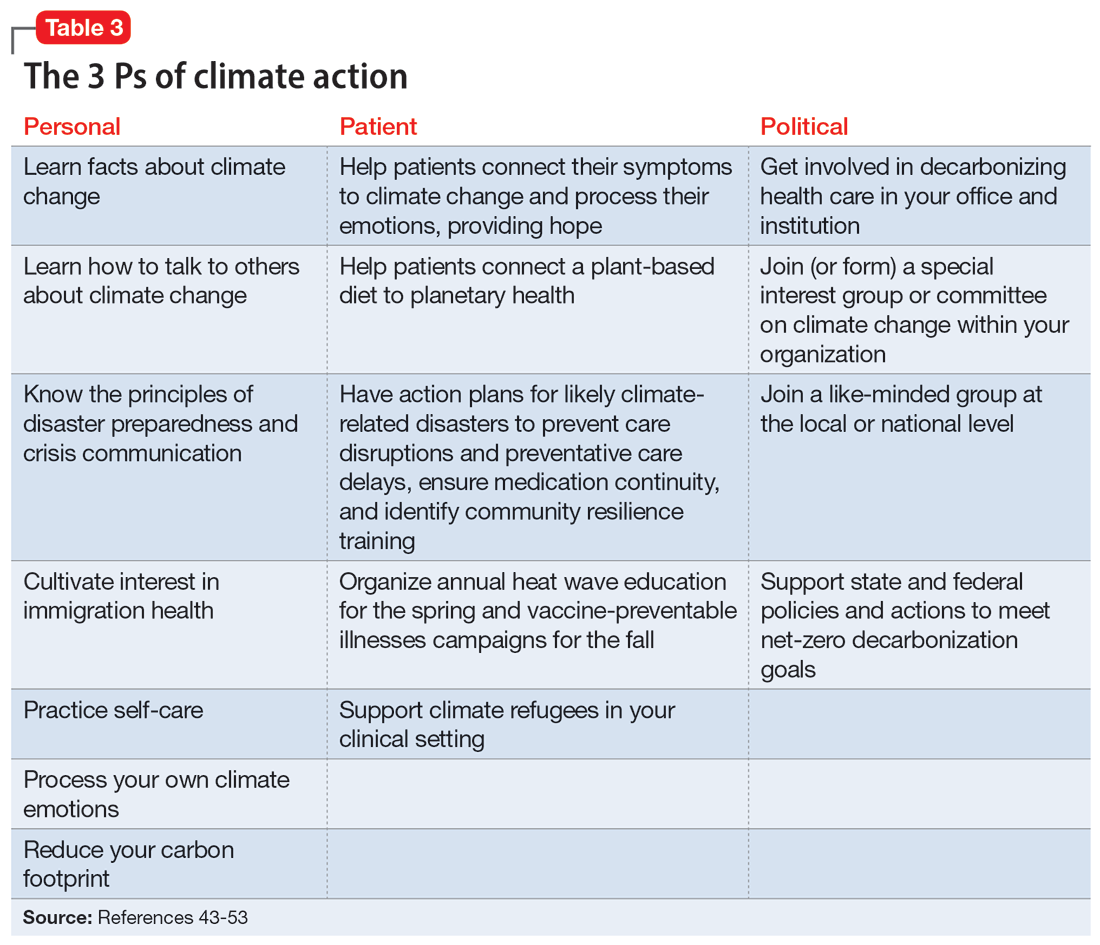

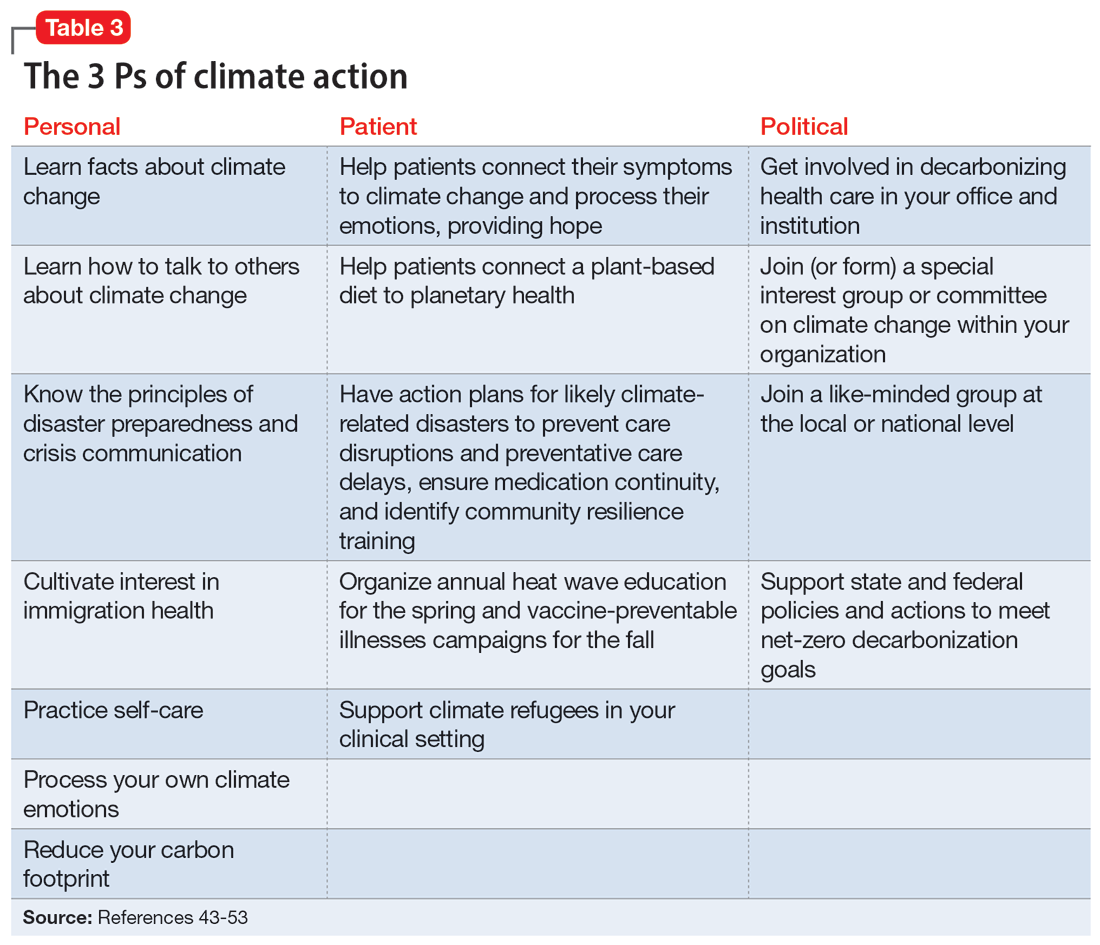

There are many ways a psychiatrist can professionally get involved in addressing climate change. Table 343-53 outlines the 3 Ps of climate action (taking actions to mitigate the effects of climate change): personal, patient (and clinic), and political (advocacy).

Personal

Even if clinicians believe climate change is important for their clinical work, they may still feel overwhelmed and unsure what to do in the context of competing responsibilities. A necessary first step is overcoming paralysis from the enormity of the problem, including the need to shift away from an expanding consumption model to environmental sustainability in a short period of time.

A good starting point is to get educated on the facts of climate change and how to discuss it in an office setting as well as in your personal life. A basic principle of climate change communication is that constructive hope (progress achieved despite everything) coupled with constructive doubt (the reality of the threat) can mobilize people towards action, whereas false hope or fatalistic doubt impedes action.43 The importance of optimal public health messaging cannot be overstated; well-meaning campaigns to change behavior can fail if they emphasize the wrong message. For example, in a study examining COVID-19 messaging in >80 countries, Dorison et al44 found that negatively framed messages mostly increased anxiety but had no benefit with regard to shifting people toward desired behaviors.

In addition, clinicians can learn how to confront climate disavowal and difficult emotions in themselves and even plan to shift to carbon neutrality, such as purchasing carbon offsets or green sources of energy and transportation. They may not be familiar with principles of disaster preparedness or crisis communication.46 Acquiring those professional skills may suggest next steps for action. Being familiar with the challenges and resources for immigrants, including individuals displaced due to climate change, may be necessary.47 Finally, to reduce the risk of burnout, it is important to practice self-care, including strategies to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.

Patient

In clinical encounters, clinicians can be proactive in helping patients understand their climate-related anxieties around an uncertain future, including identifying barriers to climate action.48

Continue to: Clinics must prepare for disasters...

Clinics must prepare for disasters in their communities to prevent disruption of psychiatric care by having an action plan, including the provision of medications. Such action plans should be prioritized for the most likely scenarios in an individual’s setting (eg, heat waves, wildfires, hurricanes, or flooding).

It is important to educate clinic staff and include them in planning for emergencies, because an all-hands approach and buy-in from all team members is critical. Clinicians should review how patients would continue to receive services, particularly medications, in the event of a disaster. In some cases, providing a 90-day medication supply will suffice, while in others (eg, patients receiving long-acting antipsychotics or clozapine) more preparation is necessary. Some events are predictable and can be organized annually, such as clinicians becoming vaccine ambassadors and organizing vaccine campaigns every fall50; winter-related disaster preparation every fall; and heat wave education every spring (leaflets for patients, staff, and family members; review of safety of medications during heat waves). Plan for, monitor, and coordinate medical care and services for climate refugees and other populations that may otherwise delay medical care and impede illness prevention. Finally, support climate refugees, including connecting them to services or providing trauma-informed care.

Political

Some clinicians may feel compelled to become politically active to advocate for changes within the health care system. Two initiatives related to decarbonizing the health care sector are My Green Doctor51 and Health Care Without Harm,52 which offer help in shifting your office, clinic, or hospital towards carbon neutrality.

Climate change unevenly affects people and will continue to exacerbate inequalities in society, including individuals with mental illness.53 To work toward climate justice on behalf of their patients, clinicians could join (or form) climate committees of special interest groups in their professional organizations or setting. Joining like-minded groups working on climate change at the local or national level prevents an omission of a psychiatric voice and counteracts burnout. It is important to stay focused on the root causes of the problem during activism: doing something to reduce fossil fuel use is ultimately most important.54 The concrete goal of reaching the Paris 1.5-degree Celsius climate goal is a critical benchmark against which any other action can be measured.54

Planning for the future

Over the course of history, societies have always faced difficult periods in which they needed to rebuild after natural disasters or self-inflicted catastrophes such as terrorist attacks or wars. Since the advent of the nuclear age, people have lived under the existential threat of nuclear war. The Anthropocene is a proposed geological term that reflects the enormous and possibly disastrous impact human activity has had on our planet.55 While not yet formally adopted, this term has heuristic value, directing attention and reflection to our role and its now undisputed consequences. In the future, historians will debate if the scale of our current climate crisis has been different. It is, however, not controversial that humanity will be faced with the effects of climate change for the foreseeable future.10 Already, even “normal” weather events are fueled by energy in overcharged and altered weather systems due to global warming, leading to weather events ranging from droughts to floods and storms that are more severe, more frequent, and have longer-lasting effects on communities.56

Continue to: As physicians, we are tasked...

As physicians, we are tasked by society to create and maintain a health care system that addresses the needs of our patients and the communities in which they live. Increasingly, we are forced to contend with an addition to the traditional 5 phases of acute disaster management (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery) to manage prolonged or even parallel disasters, where a series of disasters occurs before the community has recovered and healed. We must grapple with a sense of an “extended period of insecurity and instability” (permacrisis) and must better prepare for and prevent the polycrisis (many simultaneous crises) or the metacrisis of our “age of turmoil”57 in which we must limit global warming, mitigate its damage, and increase community resilience to adapt.

Leading by personal example and providing hope may be what some patients need, as the reality of climate change contributes to the general uneasiness about the future and doomsday scenarios to which many fall victim. At the level of professional societies, many are calling for leadership, including from mental health organizations, to bolster the “social climate,” to help us strengthen our emotional resilience and social bonds to better withstand climate change together.58 It is becoming harder to justify standing on the sidelines,59 and it may be better for both our world and a clinician’s own sanity to be engaged in professional and private hopeful action1 to address climate change. Without ecological or planetary health, there can be no mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can prepare their patients for climate-related disruptions and manage the impact climate change has on their mental health. Addressing climate change at clinical and political levels is consistent with the leadership roles and professional ethics clinicians face in daily practice.

Related Resources

- Lim C, MacLaurin S, Freudenreich O. Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):27-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0287

- My Green Doctor. https://mygreendoctor.org/

- The Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit from Americares. https://www.americares.org/what-we-do/community-health/climate-resilient-health-clinics

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance. https://www.climatepsychiatry.org/

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

1. Kretz L. Hope in environmental philosophy. J Agricult Environ Ethics. 2013;26:925-944. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9425-8

2. Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Cooper R. Position statement on mental health and climate change. American Psychiatric Association. March 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/0ce71f37-61a6-44d0-8fcd-c752b7e935fd/Position-Mental-Health-Climate-Change.pdf

3. Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

4. Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. health sector - a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

5. Haase E, Augustinavicius JH, K. Climate change and psychiatry. In: Tasman A, Riba MB, Alarcón RD, et al, eds. Tasman’s Psychiatry. 5th ed. Springer; 2023.

6. Belkin G. Mental health and the global race to resilience. Psychiatr Times. 2023;40(3):26.

7. Hu SR, Yang JQ. Harvard Medical School will integrate climate change into M.D. curriculum. The Harvard Crimson. February 3, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/2/3/hms-climate-curriculum/#:~:text=The%20new%20climate%20change%20curriculum,in%20arriving%20at%20climate%20solutions

8. Funk C, Gramlich J. Amid coronavirus threat, Americans generally have a high level of trust in medical doctors. Pew Research Center. March 13, 2020. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/13/amid-coronavirus-threat-americans-generally-have-a-high-level-of-trust-in-medical-doctors/

9. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. Climate change: a call to action for the psychiatric profession. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):317-323. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0885-7

10. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR6 synthesis report: climate change 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

11. Perera FP. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(2):141-148. doi:10.1289/EHP299

12. Hahad O, Lelieveldz J, Birklein F, et al. Ambient air pollution increases the risk of cerebrovascular and neuropsychiatric disorders through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4306. doi:10.3390/ijms21124306

13. Brockmeyer S, D’Angiulli A. How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation. Translational Neurosci. 2016;7(1):24-30. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2016-0005

14. Yang T, Wang J, Huang J, et al. Long-term exposure to multiple ambient air pollutants and association with incident depression and anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:305-313. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4812

15. Worthington MA, Petkova E, Freudenreich O, et al. Air pollution and hippocampal atrophy in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.001

16. Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, et al. Climate change and risk of completed suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(7):559-565. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001162

17. Burke M, Gonzales F, Bayis P, et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat Climate Change. 2018;8:723-729. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

18. Frangione B, Villamizar LAR, Lang JJ, et al. Short-term changes in meteorological conditions and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022;207:112230. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112230

19. Rocklov J, Dubrow R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(5):479-483. doi:10.1038/s41590-020-0648-y

20. Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022;607(7919):555-562. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

21. Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AFM, et al. Hungry in the womb: what are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine. Maturitas. 2011;70(2):141-145. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.017

22. Liu Y, Diao L, Xu L. The impact of childhood experience of starvations on the health of older adults: evidence from China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(2):515-531. doi:10.1002/hpm.3099

23. Rothschild J, Haase E. The mental health of women and climate change: direct neuropsychiatric impacts and associated psychological concerns. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;160(2):405-413. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14479

24. Cianconi P, Betro S, Janiri L. The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Frontiers Psychiatry. 2020;11:74. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

25. World Economic Forum. Climate refugees – the world’s forgotten victims. June 18, 2021. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-refugees-the-world-s-forgotten-victims

26. Climate Refugees. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climate-refugees.org/why

27. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12(19):7836. doi:10.3390/su12197836

28. Galway LP, Beery T, Jones-Casey K, et al. Mapping the solastalgia literature: a scoping review study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2662. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152662

29. Albrecht GA. Earth Emotions. New Words for a New World. Cornell University Press; 2019.

30. Sorensen C, Hess J. Treatment and prevention of heat-related illness. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1404-1413. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2210623

31. Chong TWH, Castle DJ. Layer upon layer: thermoregulation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69(2-3):149-157. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00222-6

32. von Salis S, Ehlert U, Fischer S. Altered experienced thermoregulation in depression--no evidence for an effect of early life stress. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:620656. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620656

33. Sarchiapone M, Gramaglia C, Iosue M, et al. The association between electrodermal activity (EDA), depression and suicidal behaviour: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1551-4

34. Martin-Latry K, Goumy MP, Latry P, et al. Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):335-338. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.007

35. Ebi KL, Capon A, Berry P, et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet. 2021;398(10301):698-708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3

36. Lee MJ, McLean KE, Kuo M, et al. Chronic diseases associated with mortality in British Columbia, Canada during the 2021 Western North America extreme heat event. Geohealth. 2023;7(3):e2022GH000729. doi:10.1029/2022GH000729

37. Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Raja P, et al. Disruptions in care for Medicare beneficiaries with severe mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2145677. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.45677

38. Siskind D, Honer WG, Clark S, et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(3):222-223. doi:10.1503/jpn.200061

39. MacLaurin SA, Mulligan C, Van Alphen MU, et al. Optimal long-acting injectable antipsychotic management during COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(1): 20l13730. doi:10.4088/JCP.20l13730

40. Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, et al. COVID-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(10):1078-1081. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000244

41. Van Alphen MU, Lim C, Freudenreich O. Mobile vaccine clinics for patients with serious mental illness and health care workers in outpatient mental health clinics. Psychiatr Serv. February 8, 2023. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.20220460

42. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Maclaurin S, et al. Increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates among patients with serious mental illness: a pilot intervention study. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(11):1274-1277. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202100702

43. Marlon JR, Bloodhart B, Ballew MT, et al. How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Front Commun. May 21, 2019. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

44. Dorison CA, Lerner JS, Heller BH, et al. In COVID-19 health messaging, loss framing increases anxiety with little-to-no concomitant benefits: experimental evidence from 84 countries. Affective Sci. 2022;3(3):577-602. doi:10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3

45. Maibach E. Increasing public awareness and facilitating behavior change: two guiding heuristics. George Mason University, Center for Climate Change Communication. September 2015. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climatechangecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Maibach-Two-hueristics-September-2015-revised.pdf

46. Koh KA, Raviola G, Stoddard FJ Jr. Psychiatry and crisis communication during COVID-19: a view from the trenches. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(5):615. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000912

47. Velez G, Adam B, Shadid O, et al. The clock is ticking: are we prepared for mass climate migration? Psychiatr News. March 24, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2023.04.4.3

48. Ingle HE, Mikulewicz M. Mental health and climate change: tackling invisible injustice. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:e128-e130. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30081-4

49. Shah UA, Merlo G. Personal and planetary health--the connection with dietary choices. JAMA. 2023;329(21):1823-1824. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.6118

50. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Freudenreich O. Becoming vaccine ambassadors: a new role for psychiatrists. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):10-11,17-21,26-28,38. doi:10.12788/cp.0155

51. My Green Doctor. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://mygreendoctor.org/

52. Healthcare Without Harm. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://noharm.org/

53. Levy BS, Patz JA. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:310-322.

54. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global warming of 1.5° C 2018. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

55. Steffen W, Crutzen J, McNeill JR. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? Ambio. 2007;36(8):614-621. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:taahno]2.0.co;2

56. American Meteorological Society. Explaining extreme events from a climate perspective. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ametsoc.org/ams/index.cfm/publications/bulletin-of-the-american-meteorological-society-bams/explaining-extreme-events-from-a-climate-perspective/

57. Nierenberg AA. Coping in the age of turmoil. Psychiatr Ann. 2022;52(7):263. July 1, 2022. doi:10.3928/23258160-20220701-01

58. Belkin G. Leadership for the social climate. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1975-1977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2001507

59. Skinner JR. Doctors and climate change: first do no harm. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(11):1754-1758. doi:10.1111/jpc.15658

“ Hope is engagement with the act of mapping our destinies.” 1

—Valerie Braithwaite

Why should psychiatrists care about climate change and try to mitigate its effects? First, we are tasked by society with managing the psychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae from disasters, which include climate change. The American Psychiatric Association’s position statement on climate change includes it as a legitimate focus for our specialty.2 Second, as physicians, we are morally obligated to do no harm. Since the health care sector contributes significantly to climate change (8.5% of national carbon emissions stem from health care) and causes demonstrable health impacts,3 managing these impacts and decarbonizing the health care industry is morally imperative.4 And third, psychiatric clinicians have transferrable skills that can address fears of climate change, challenge climate change denialism,5 motivate people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors, and help communities not only endure the emotional impact of climate change but become more psychologically resilient.6

Most psychiatrists, however, did not receive formal training on climate change and the related field of disaster preparedness. For example, Harvard Medical School did not include a course on climate change in their medical student curriculum until 2023.7 In this article, we provide a basic framework of climate change and its impact on mental health, with particular focus on patients with serious mental illness (SMI). We offer concrete steps clinicians can take to prevent or mitigate harm from climate change for their patients, prepare for disasters at the level of individual patient encounters, and strengthen their clinics and communities. We also encourage clinicians to take active leadership roles in their professional organizations to be part of climate solutions, building on the trust patients continue to have in their physicians.8 Even if clinicians do not view climate change concerns under their conceived clinical care mandate, having a working knowledge about it is important because patients, paraprofessional staff, or medical trainees are likely to bring it up.9

Climate change and mental health

Climate change is harmful to human health, including mental health.10 It can impact mental health directly via its impact on brain function and neuropsychiatric sequelae, and indirectly via climate-related disasters leading to acute or chronic stress, losses, and displacement with psychiatric and psychological sequelae (Table 111-29).

Direct impact

The effects of air pollution, heat, infections, and starvation are examples of how climate change directly impacts mental health. Air pollution and brain health are a concern for psychiatry, given the well-described effects of air deterioration on the developing brain.11 In animal models, airborne pollutants lead to widespread neuroinflammation and cell loss via a multitude of mechanisms.12 This is consistent with worse cognitive and behavioral functions across a wide range of cognitive domains seen in children exposed to pollution compared to those who grew up in environments with healthy air.13 Even low-level exposure to air pollution increases the risk for later onset of depression, suicide, and anxiety.14 Hippocampal atrophy observed in patients with first-episode psychosis may also be partially attributable to air pollution.15 An association between heat and suicide (and to a lesser extent, aggression) has also been reported.16

Worse physical health (eg, strokes) due to excessive heat can further compound mental health via elevated rates of depression. Data from the United States and Mexico show that for each degree Celsius increase in ambient temperature, suicide rates may increase by approximately 1%.17 A meta-analysis by Frangione et al18 similarly concluded that each degree Celsius increase results in an overall risk ratio of 1.016 (95% CI, 1.012 to 1.019) for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. Additionally, global warming is shifting the endemic areas for many infectious agents, particularly vector-borne diseases,19 to regions in which they had hitherto been unknown, increasing the risk for future outbreaks and even pandemics.20 These infectious illnesses often carry neuropsychiatric morbidity, with seizures, encephalopathy with incomplete recovery, and psychiatric syndromes occurring in many cases. Crop failure can lead to starvation during pregnancy and childhood, which has wide-ranging consequences for brain development and later physical and psychological health in adults.21,22 Mothers affected by starvation also experience negative impacts on childbearing and childrearing.23

Indirect impact

Climate change’s indirect impact on mental health can stem from the stress of living through a disaster such as an extreme weather event; from losses, including the death of friends and family members; and from becoming temporarily displaced.24 Some climate change–driven disasters can be viewed as slow-moving, such as drought and the rising of sea levels, where displacement becomes permanent. Managing mass migration from internally or externally displaced people who must abandon their communities because of climate change will have significant repercussions for all societies.25 The term “climate refugee” is not (yet) included in the United Nations’ official definition of refugees; it defines refugees as individuals who have fled their countries because of war, violence, or persecution.26 These and other bureaucratic issues can come up when clinicians are trying to help migrants with immigration-related paperwork.

Continue to: As the inevitability of climate change...

As the inevitability of climate change sinks in, its long-term ramifications have introduced a new lexicon of psychological suffering related to the crisis.27 Common terms for such distress include ecoanxiety (fear of what is happening and will happen with climate change), ecogrief (sadness about the destruction of species and natural habitats), solastalgia28 (the nostalgia an individual feels for emotionally treasured landscapes that have changed), and terrafuria or ecorage (the reaction to betrayal and inaction by governments and leaders).29 Climate-related emotions can lead to pessimism about the future and a nihilistic outlook on an individual’s ability to effect change and have agency over their life’s outcomes.

The categories of direct and indirect impacts are not mutually exclusive. A child may be starving due to weather-related crop failure as the family is forced to move to another country, then have to contend with prejudice and bullying as an immigrant, and later become anxiously preoccupied with climate change and its ability to cause further distress.

Effect on individuals with serious mental illness

Patients with SMI are particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. They are less resilient to climate change–related events, such as heat waves or temporary displacement from flooding, both at the personal level due to illness factors (eg, negative symptoms or cognitive impairment) and at the community level due to social factors (eg, weaker social support or poverty).