User login

FFR-guided PCI falls short vs. surgery in multivessel disease: FAME 3

Coronary stenting guided by fractional flow reserve (FFR) readings, considered to reflect the targeted lesion’s functional impact, was no match for coronary bypass surgery (CABG) in patients with multivessel disease (MVD) in a major international randomized trial.

Indeed, FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using one of the latest drug-eluting stents (DES) seemed to perform poorly in the trial, compared with surgery, apparently upping the risk for clinical events by 50% over 1 year.

Designed statistically for noninferiority, the third Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial, with 1,500 randomized patients, showed that FFR-guided PCI was “not noninferior” to CABG. Of those randomized to PCI, 10.6% met the 1-year primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), compared with only 6.9% of patients assigned to CABG.

The trial enrolled only patients with three-vessel coronary disease with no left-main coronary artery involvement, who were declared by their institution’s multidisciplinary heart team to be appropriate for either form of revascularization.

One of the roles of FFR for PCI guidance is to identify significant lesions “that are underrecognized by the angiogram,” which is less likely to happen in patients with very complex coronary anatomy, study chair William F. Fearon, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

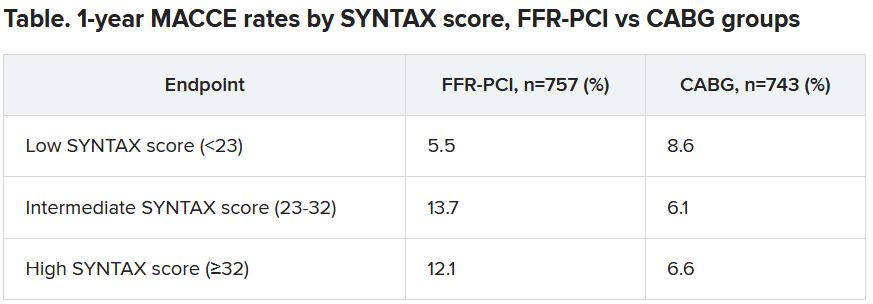

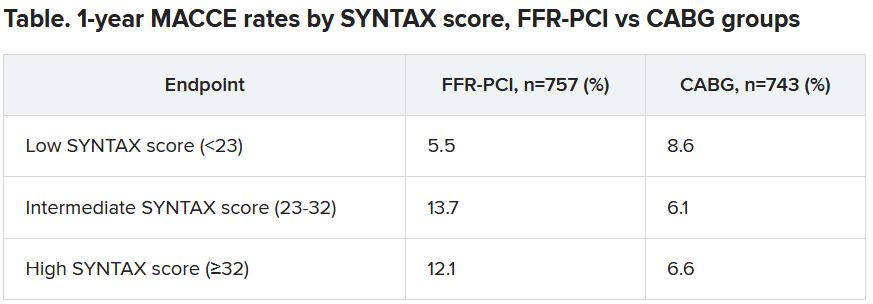

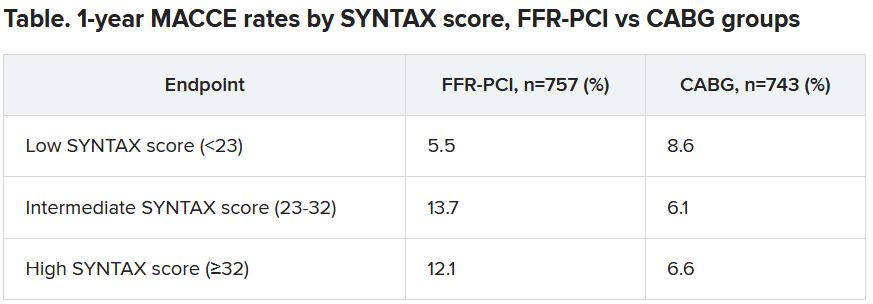

“That’s what we saw in a subgroup analysis based on SYNTAX score,” an index of lesion complexity. “In patients with very high SYNTAX scores, CABG outperformed FFR-guided PCI. But if you look at patients with low SYNTAX scores, actually, FFR-guided PCI outperformed CABG for 1-year MACCE.”

Dr. Fearon is lead author on the study’s Nov. 4, 2021, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, its release timed to coincide with his presentation of the trial at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He noted that FAME-3 “wasn’t designed or powered to test for superiority,” so its results do not imply CABG is superior to FFR-PCI in patients with MVD, and remains “inconclusive” on that question.

“I think what this study does is provide both the physician and patients more contemporary data and information on options and expected outcomes in multivessel disease. So if you are a patient who has less complex disease, I think you can feel comfortable that you will get an equivalent result with FFR-guided PCI.” But, at least based on FAME-3, Dr. Fearon said, CABG provides better outcomes in patients with more complex disease.

“I think there are still patients that look at trade-offs. Some patients will accept a higher event rate in order to avoid a long recovery, and vice versa.” So the trial may allow patients and physicians to make more informed decisions, he said.

A main message of FAME-3 “is that we’re getting very good results with three-vessel PCI, but better results with surgery,” Ran Kornowski, MD, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, said as a discussant following Dr. Fearon’s presentation of the trial. The subanalysis by SYNTAX score, he agreed, probably could be used as part of shared decision-making with patients.

Not all that surprising

“It’s a well-designed study, with a lot of patients,” said surgeon Frank W. Sellke, MD, of Rhode Island Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Brown University, all in Providence.

“I don’t think it’s all that surprising,” he said in an interview. “It’s very consistent with what other studies have shown, that for three-vessel disease, surgery tends to have the edge,” even when pitted against FFR-guided PCI.

Indeed, pressure-wire FFR-PCI has a spotty history, even as an alternative to standard angiography-based PCI. For example, it has performed well in registry and other cohort studies but showed no advantage in the all-comers RIPCORD-2 trial or in the setting of complete revascularization PCI for acute MI in FLOWER-MI. And it emitted an increased-mortality signal in the prematurely halted FUTURE trial.

In FAME-3, “the 1-year follow-up was the best chance for FFR-PCI to be noninferior to CABG. The CABG advantage is only going to get better with time if prior experience and pathobiology is true,” Sanjay Kaul, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Overall, “the quality and quantity of evidence is insufficient to support FFR-guided PCI” in patients with complex coronary artery disease (CAD), he said. “I would also argue that the evidence for FFR-guided PCI for simple CAD is also not high quality.”

Dr. Kaul also blasted the claim that FFR-PCI was seen to perform better against CABG in patients with low SYNTAX scores. “In general, one cannot use a positive subgroup in a null or negative trial, as is the case with FAME-3, to ‘rescue’ the treatment intervention.” Such a positive subgroup finding, he said, “would at best be deemed hypothesis-generating and not hypothesis validating.”

Dr. Fearon agreed that the subgroup analysis by SYNTAX score, though prespecified, was only hypothesis generating. “But I think that other studies have shown the same thing – that in less complex disease, the two strategies appear to perform in a similar fashion.”

The FAME-3 trial’s 1,500 patients were randomly assigned at 48 centers to undergo standard CABG or FFR-guided PCI with Resolute Integrity (Medtronic) zotarolimus-eluting DES. Lesions with a pressure-wire FFR of 0.80 or less were stented and those with higher FFR readings were deferred.

The 1-year hazard ratio for the primary endpoint—a composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or repeat revascularization – was 1.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.2) with a noninferiority P value of .35 for the comparison of FFR-PCI versus CABG.

FFR-guided PCI fared significantly better than CABG for some safety endpoints, including major bleeding (1.6% vs 3.8%, P < .01), arrhythmia including atrial fibrillation (2.4% vs. 14.1%, P < .001), acute kidney injury (0.1% vs 0.9%, P < .04), and 30-day rehospitalization (5.5% vs 10.2%, P < .001).

Did the primary endpoint favor CABG?

At a media briefing prior to Dr. Fearon’s TCT 2021 presentation of the trail, Roxana Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, proposed that the inclusion of repeat revascularization in the trial’s composite primary endpoint tilted the outcome in favor of CABG. “To me, the FAME-3 results are predictable because repeat revascularization is in the equation.”

It’s well recognized that the endpoint is less likely after CABG than PCI. The latter treats focal lesions that are a limited part of a coronary artery in which CAD is still likely progressing. CABG, on the other hand, can bypass longer segments of diseased artery.

Indeed, as Dr. Fearon reported, the rates of death, MI, or stroke excluding repeat revascularization were 7.3% with FFR-PCI and 5.2% for CABG, for an HR of 1.4 (95% CI, 0.9-2.1).

Dr. Mehran also proposed that intravascular-ultrasound (IVUS) guidance, had it been part of the trial, could potentially have boosted the performance of FFR-PCI.

Repeat revascularization, Dr. Kaul agreed, “should not have been included” in the trial’s primary endpoint. It had been added “to amplify events and to minimize sample size. Not including revascularization would render the sample size prohibitive. There is always give and take in designing clinical trials.”

And he agreed that “IVUS-based PCI optimization would have further improved PCI outcomes.” However, “IVUS plus FFR adds to the procedural burden and limited resources available.” Dr. Fearon said when interviewed that the trial’s definition of procedural MI, a component of the primary endpoint, might potentially be seen as controversial. Procedural MIs in both the PCI and CABG groups were required to meet the standards of CABG-related type-5 MI according to the third and fourth Universal Definitions. The had also had to be accompanied by “a significant finding like new Q waves or a new wall-motion abnormality on echocardiography,” he said.

“That’s fairly strict. Because of that, we had a low rate of periprocedural MI and it was similar between the two groups, around 1.5% in both arms.”

FAME-3 was funded by Medtronic and Abbott Vascular. Dr. Kaul disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kornowsky receives royalties from or holds intellectual property rights with CathWorks. Dr. Mehran disclosed financial ties to numerous pharmaceutical and device companies, and that she, her spouse, or her institution hold equity in Elixir Medical, Applied Therapeutics, and ControlRad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Coronary stenting guided by fractional flow reserve (FFR) readings, considered to reflect the targeted lesion’s functional impact, was no match for coronary bypass surgery (CABG) in patients with multivessel disease (MVD) in a major international randomized trial.

Indeed, FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using one of the latest drug-eluting stents (DES) seemed to perform poorly in the trial, compared with surgery, apparently upping the risk for clinical events by 50% over 1 year.

Designed statistically for noninferiority, the third Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial, with 1,500 randomized patients, showed that FFR-guided PCI was “not noninferior” to CABG. Of those randomized to PCI, 10.6% met the 1-year primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), compared with only 6.9% of patients assigned to CABG.

The trial enrolled only patients with three-vessel coronary disease with no left-main coronary artery involvement, who were declared by their institution’s multidisciplinary heart team to be appropriate for either form of revascularization.

One of the roles of FFR for PCI guidance is to identify significant lesions “that are underrecognized by the angiogram,” which is less likely to happen in patients with very complex coronary anatomy, study chair William F. Fearon, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

“That’s what we saw in a subgroup analysis based on SYNTAX score,” an index of lesion complexity. “In patients with very high SYNTAX scores, CABG outperformed FFR-guided PCI. But if you look at patients with low SYNTAX scores, actually, FFR-guided PCI outperformed CABG for 1-year MACCE.”

Dr. Fearon is lead author on the study’s Nov. 4, 2021, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, its release timed to coincide with his presentation of the trial at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He noted that FAME-3 “wasn’t designed or powered to test for superiority,” so its results do not imply CABG is superior to FFR-PCI in patients with MVD, and remains “inconclusive” on that question.

“I think what this study does is provide both the physician and patients more contemporary data and information on options and expected outcomes in multivessel disease. So if you are a patient who has less complex disease, I think you can feel comfortable that you will get an equivalent result with FFR-guided PCI.” But, at least based on FAME-3, Dr. Fearon said, CABG provides better outcomes in patients with more complex disease.

“I think there are still patients that look at trade-offs. Some patients will accept a higher event rate in order to avoid a long recovery, and vice versa.” So the trial may allow patients and physicians to make more informed decisions, he said.

A main message of FAME-3 “is that we’re getting very good results with three-vessel PCI, but better results with surgery,” Ran Kornowski, MD, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, said as a discussant following Dr. Fearon’s presentation of the trial. The subanalysis by SYNTAX score, he agreed, probably could be used as part of shared decision-making with patients.

Not all that surprising

“It’s a well-designed study, with a lot of patients,” said surgeon Frank W. Sellke, MD, of Rhode Island Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Brown University, all in Providence.

“I don’t think it’s all that surprising,” he said in an interview. “It’s very consistent with what other studies have shown, that for three-vessel disease, surgery tends to have the edge,” even when pitted against FFR-guided PCI.

Indeed, pressure-wire FFR-PCI has a spotty history, even as an alternative to standard angiography-based PCI. For example, it has performed well in registry and other cohort studies but showed no advantage in the all-comers RIPCORD-2 trial or in the setting of complete revascularization PCI for acute MI in FLOWER-MI. And it emitted an increased-mortality signal in the prematurely halted FUTURE trial.

In FAME-3, “the 1-year follow-up was the best chance for FFR-PCI to be noninferior to CABG. The CABG advantage is only going to get better with time if prior experience and pathobiology is true,” Sanjay Kaul, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Overall, “the quality and quantity of evidence is insufficient to support FFR-guided PCI” in patients with complex coronary artery disease (CAD), he said. “I would also argue that the evidence for FFR-guided PCI for simple CAD is also not high quality.”

Dr. Kaul also blasted the claim that FFR-PCI was seen to perform better against CABG in patients with low SYNTAX scores. “In general, one cannot use a positive subgroup in a null or negative trial, as is the case with FAME-3, to ‘rescue’ the treatment intervention.” Such a positive subgroup finding, he said, “would at best be deemed hypothesis-generating and not hypothesis validating.”

Dr. Fearon agreed that the subgroup analysis by SYNTAX score, though prespecified, was only hypothesis generating. “But I think that other studies have shown the same thing – that in less complex disease, the two strategies appear to perform in a similar fashion.”

The FAME-3 trial’s 1,500 patients were randomly assigned at 48 centers to undergo standard CABG or FFR-guided PCI with Resolute Integrity (Medtronic) zotarolimus-eluting DES. Lesions with a pressure-wire FFR of 0.80 or less were stented and those with higher FFR readings were deferred.

The 1-year hazard ratio for the primary endpoint—a composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or repeat revascularization – was 1.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.2) with a noninferiority P value of .35 for the comparison of FFR-PCI versus CABG.

FFR-guided PCI fared significantly better than CABG for some safety endpoints, including major bleeding (1.6% vs 3.8%, P < .01), arrhythmia including atrial fibrillation (2.4% vs. 14.1%, P < .001), acute kidney injury (0.1% vs 0.9%, P < .04), and 30-day rehospitalization (5.5% vs 10.2%, P < .001).

Did the primary endpoint favor CABG?

At a media briefing prior to Dr. Fearon’s TCT 2021 presentation of the trail, Roxana Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, proposed that the inclusion of repeat revascularization in the trial’s composite primary endpoint tilted the outcome in favor of CABG. “To me, the FAME-3 results are predictable because repeat revascularization is in the equation.”

It’s well recognized that the endpoint is less likely after CABG than PCI. The latter treats focal lesions that are a limited part of a coronary artery in which CAD is still likely progressing. CABG, on the other hand, can bypass longer segments of diseased artery.

Indeed, as Dr. Fearon reported, the rates of death, MI, or stroke excluding repeat revascularization were 7.3% with FFR-PCI and 5.2% for CABG, for an HR of 1.4 (95% CI, 0.9-2.1).

Dr. Mehran also proposed that intravascular-ultrasound (IVUS) guidance, had it been part of the trial, could potentially have boosted the performance of FFR-PCI.

Repeat revascularization, Dr. Kaul agreed, “should not have been included” in the trial’s primary endpoint. It had been added “to amplify events and to minimize sample size. Not including revascularization would render the sample size prohibitive. There is always give and take in designing clinical trials.”

And he agreed that “IVUS-based PCI optimization would have further improved PCI outcomes.” However, “IVUS plus FFR adds to the procedural burden and limited resources available.” Dr. Fearon said when interviewed that the trial’s definition of procedural MI, a component of the primary endpoint, might potentially be seen as controversial. Procedural MIs in both the PCI and CABG groups were required to meet the standards of CABG-related type-5 MI according to the third and fourth Universal Definitions. The had also had to be accompanied by “a significant finding like new Q waves or a new wall-motion abnormality on echocardiography,” he said.

“That’s fairly strict. Because of that, we had a low rate of periprocedural MI and it was similar between the two groups, around 1.5% in both arms.”

FAME-3 was funded by Medtronic and Abbott Vascular. Dr. Kaul disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kornowsky receives royalties from or holds intellectual property rights with CathWorks. Dr. Mehran disclosed financial ties to numerous pharmaceutical and device companies, and that she, her spouse, or her institution hold equity in Elixir Medical, Applied Therapeutics, and ControlRad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Coronary stenting guided by fractional flow reserve (FFR) readings, considered to reflect the targeted lesion’s functional impact, was no match for coronary bypass surgery (CABG) in patients with multivessel disease (MVD) in a major international randomized trial.

Indeed, FFR-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using one of the latest drug-eluting stents (DES) seemed to perform poorly in the trial, compared with surgery, apparently upping the risk for clinical events by 50% over 1 year.

Designed statistically for noninferiority, the third Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial, with 1,500 randomized patients, showed that FFR-guided PCI was “not noninferior” to CABG. Of those randomized to PCI, 10.6% met the 1-year primary endpoint of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCE), compared with only 6.9% of patients assigned to CABG.

The trial enrolled only patients with three-vessel coronary disease with no left-main coronary artery involvement, who were declared by their institution’s multidisciplinary heart team to be appropriate for either form of revascularization.

One of the roles of FFR for PCI guidance is to identify significant lesions “that are underrecognized by the angiogram,” which is less likely to happen in patients with very complex coronary anatomy, study chair William F. Fearon, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

“That’s what we saw in a subgroup analysis based on SYNTAX score,” an index of lesion complexity. “In patients with very high SYNTAX scores, CABG outperformed FFR-guided PCI. But if you look at patients with low SYNTAX scores, actually, FFR-guided PCI outperformed CABG for 1-year MACCE.”

Dr. Fearon is lead author on the study’s Nov. 4, 2021, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, its release timed to coincide with his presentation of the trial at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

He noted that FAME-3 “wasn’t designed or powered to test for superiority,” so its results do not imply CABG is superior to FFR-PCI in patients with MVD, and remains “inconclusive” on that question.

“I think what this study does is provide both the physician and patients more contemporary data and information on options and expected outcomes in multivessel disease. So if you are a patient who has less complex disease, I think you can feel comfortable that you will get an equivalent result with FFR-guided PCI.” But, at least based on FAME-3, Dr. Fearon said, CABG provides better outcomes in patients with more complex disease.

“I think there are still patients that look at trade-offs. Some patients will accept a higher event rate in order to avoid a long recovery, and vice versa.” So the trial may allow patients and physicians to make more informed decisions, he said.

A main message of FAME-3 “is that we’re getting very good results with three-vessel PCI, but better results with surgery,” Ran Kornowski, MD, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Tel Aviv University, said as a discussant following Dr. Fearon’s presentation of the trial. The subanalysis by SYNTAX score, he agreed, probably could be used as part of shared decision-making with patients.

Not all that surprising

“It’s a well-designed study, with a lot of patients,” said surgeon Frank W. Sellke, MD, of Rhode Island Hospital, Miriam Hospital, and Brown University, all in Providence.

“I don’t think it’s all that surprising,” he said in an interview. “It’s very consistent with what other studies have shown, that for three-vessel disease, surgery tends to have the edge,” even when pitted against FFR-guided PCI.

Indeed, pressure-wire FFR-PCI has a spotty history, even as an alternative to standard angiography-based PCI. For example, it has performed well in registry and other cohort studies but showed no advantage in the all-comers RIPCORD-2 trial or in the setting of complete revascularization PCI for acute MI in FLOWER-MI. And it emitted an increased-mortality signal in the prematurely halted FUTURE trial.

In FAME-3, “the 1-year follow-up was the best chance for FFR-PCI to be noninferior to CABG. The CABG advantage is only going to get better with time if prior experience and pathobiology is true,” Sanjay Kaul, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Overall, “the quality and quantity of evidence is insufficient to support FFR-guided PCI” in patients with complex coronary artery disease (CAD), he said. “I would also argue that the evidence for FFR-guided PCI for simple CAD is also not high quality.”

Dr. Kaul also blasted the claim that FFR-PCI was seen to perform better against CABG in patients with low SYNTAX scores. “In general, one cannot use a positive subgroup in a null or negative trial, as is the case with FAME-3, to ‘rescue’ the treatment intervention.” Such a positive subgroup finding, he said, “would at best be deemed hypothesis-generating and not hypothesis validating.”

Dr. Fearon agreed that the subgroup analysis by SYNTAX score, though prespecified, was only hypothesis generating. “But I think that other studies have shown the same thing – that in less complex disease, the two strategies appear to perform in a similar fashion.”

The FAME-3 trial’s 1,500 patients were randomly assigned at 48 centers to undergo standard CABG or FFR-guided PCI with Resolute Integrity (Medtronic) zotarolimus-eluting DES. Lesions with a pressure-wire FFR of 0.80 or less were stented and those with higher FFR readings were deferred.

The 1-year hazard ratio for the primary endpoint—a composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or repeat revascularization – was 1.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.2) with a noninferiority P value of .35 for the comparison of FFR-PCI versus CABG.

FFR-guided PCI fared significantly better than CABG for some safety endpoints, including major bleeding (1.6% vs 3.8%, P < .01), arrhythmia including atrial fibrillation (2.4% vs. 14.1%, P < .001), acute kidney injury (0.1% vs 0.9%, P < .04), and 30-day rehospitalization (5.5% vs 10.2%, P < .001).

Did the primary endpoint favor CABG?

At a media briefing prior to Dr. Fearon’s TCT 2021 presentation of the trail, Roxana Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, proposed that the inclusion of repeat revascularization in the trial’s composite primary endpoint tilted the outcome in favor of CABG. “To me, the FAME-3 results are predictable because repeat revascularization is in the equation.”

It’s well recognized that the endpoint is less likely after CABG than PCI. The latter treats focal lesions that are a limited part of a coronary artery in which CAD is still likely progressing. CABG, on the other hand, can bypass longer segments of diseased artery.

Indeed, as Dr. Fearon reported, the rates of death, MI, or stroke excluding repeat revascularization were 7.3% with FFR-PCI and 5.2% for CABG, for an HR of 1.4 (95% CI, 0.9-2.1).

Dr. Mehran also proposed that intravascular-ultrasound (IVUS) guidance, had it been part of the trial, could potentially have boosted the performance of FFR-PCI.

Repeat revascularization, Dr. Kaul agreed, “should not have been included” in the trial’s primary endpoint. It had been added “to amplify events and to minimize sample size. Not including revascularization would render the sample size prohibitive. There is always give and take in designing clinical trials.”

And he agreed that “IVUS-based PCI optimization would have further improved PCI outcomes.” However, “IVUS plus FFR adds to the procedural burden and limited resources available.” Dr. Fearon said when interviewed that the trial’s definition of procedural MI, a component of the primary endpoint, might potentially be seen as controversial. Procedural MIs in both the PCI and CABG groups were required to meet the standards of CABG-related type-5 MI according to the third and fourth Universal Definitions. The had also had to be accompanied by “a significant finding like new Q waves or a new wall-motion abnormality on echocardiography,” he said.

“That’s fairly strict. Because of that, we had a low rate of periprocedural MI and it was similar between the two groups, around 1.5% in both arms.”

FAME-3 was funded by Medtronic and Abbott Vascular. Dr. Kaul disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kornowsky receives royalties from or holds intellectual property rights with CathWorks. Dr. Mehran disclosed financial ties to numerous pharmaceutical and device companies, and that she, her spouse, or her institution hold equity in Elixir Medical, Applied Therapeutics, and ControlRad.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SUGAR trial finds superior stent for those with diabetes and CAD

Superiority shown on TLF endpoint

Designed to show noninferiority for treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with diabetes, a head-to-head comparison of contemporary stents ended up showing that one was superior to the for the primary endpoint of target lesion failure (TLF).

In the superiority analysis, the 35% relative reduction in the risk of TLF at 1 year for the Cre8 EVO (Alvimedica) stent relative to the Resolute Onyx (Medtronic) device reached significance, according to Rafael Romaguera, MD, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at the Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona.

At 1 year, the rates of TLF were 7.2% and 10.5% for the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stents, respectively. On the basis of noninferiority, the 3.73% reduction in TLF at 1 year among those receiving the Cre8 EVO device provided a highly significant confirmation of noninferiority (P < .001) and triggered the preplanned superiority analysis.

When the significant advantage on the TLF endpoint (P = .03) was broken down into its components, the Cre8 EVO stent was linked to numerically lower rates of cardiac death (2.1% vs. 2.7%), target vessel MI (5.3% vs. 7.2%), and target lesion revascularization (2.4% vs. 3.9%), according to the SUGAR (Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents in Diabetes) trial results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In a previous study comparing these devices, called the ReCre8 trial, the rates of TLF in an all-comer CAD population were similar at 1 year. When an updated 3-year analysis was presented earlier in 2021 at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies meeting, they remained similar.

Diabetes-centered trial was unmet need

The rationale for conducting a new trial limited to patients with diabetes was based on the greater risk in this population, according to Dr. Romaguera. He cited data that indicate the risk of major adverse cardiac events are about two times higher 2 years after stent implantation in patients with diabetes relative to those without, even when contemporary drug-eluting stents are used.

Both the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stent are drug eluting and employ contemporary architecture that provides the basis for marketing claims that they are suitable for complex patients; but they have differences.

“There are three features that I think differentiate the Cre8 EVO stent,” Dr. Romaguera reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

One is the absence of polymer, which contrasts with the permanent polymer of the Resolute device. This feature affects the dissolution of the anti-inflammatory drug and might be one explanation for the greater protection from ischemic events, according to Dr. Romaguera.

Another is the thickness of the struts, which range from 70 to 80 mm for the Cre8 EVO device and from 92 to 102 mm for the Resolute Onyx device. In experimental studies, strut thickness has been associated with greater risk of thrombus formation, although it is unclear if this modest difference is clinically significant.

Also important, the Cre8 EVO device employs sirolimus for an anti-inflammatory effect, while the Resolute Onyx elutes zotarolimus. Again, experimental evidence suggests a greater anti-inflammatory effect reduces the need for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT); that might offer a relative advantage in patients with an elevated risk of bleeding.

It is not clear whether all of these features contribute to the better results observed in this trial in diabetes patients, but Dr. Romaguera indicated that the lower risk of TLF with Cre8 EVO is not just statistically significant but also clinically meaningful.

In SUGAR, which included 23 centers in Spain, 1,175 patients with confirmed diabetes scheduled for percutaneous intervention (PCI) were randomized to one of the two stents. The study was purposely designed with very few exclusion criteria.

SUGAR trial employed all-comer design

“This was an all-comer design and there was no limitation in regard to clinical presentation, complexity, number of lesions, or other disease features,” said Dr. Romaguera. The major exclusions were a life expectancy of less than 2 years and a contraindication to taking DAPT for at least 1 month,

The patients were almost equally divided between those who had a non–ST-segment elevation MI) and those with chronic coronary artery disease, but patients with a STEMI, representing about 12% of the population, were included. Almost all of the patients (about 95%) had type 2 diabetes; nearly one-third were on insulin at the time of randomization.

According to Dr. Romaguera, “SUGAR is the first powered trial to compare new-generation drug-eluting stents in patients with diabetes,” and he emphasized the all-comer design in supporting its clinical relevance.

Several of those participating in discussion of the trial during the late-breaker session agreed. Although the moderator, Gregg Stone, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, expressed surprise that the trial “actually demonstrated superiority” given the difficulty of showing a difference between modern stents, he called the findings “remarkable.”

Others seemed to suggest that it would alter their practice.

“This study is sweet like sugar for us, because now we have a stent that is dedicated and fitted for the diabetic population,” said Gennaro Sardella, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome.

For Marc Etienne Jolicoeur, MD, an interventional cardiologist associated with Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the impressive findings was the early separation of the curves in favor of Cre8 EVO. Calling SUGAR a “fantastic trial,” he indicated that the progressive advantage over time reinforced his impression that the difference is real.

However, David Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta, was more circumspect. He did not express any criticisms of the trial, but he called for “a larger evidence base” before declaring the Cre8 EVO device a standard of care for patients with diabetes undergoing PCI.

The SUGAR results were published in the European Heart Journal at the time of presentation at the meeting.

The trial was funded by the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Dr. Romaguera reported financial relationships with Biotronik and Boston Scientific. Dr. Stone, has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing devices used in PCI. Dr. Sardella and Dr. Jolicoeur reported no financial relationships relevant to this topic. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

Superiority shown on TLF endpoint

Superiority shown on TLF endpoint

Designed to show noninferiority for treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with diabetes, a head-to-head comparison of contemporary stents ended up showing that one was superior to the for the primary endpoint of target lesion failure (TLF).

In the superiority analysis, the 35% relative reduction in the risk of TLF at 1 year for the Cre8 EVO (Alvimedica) stent relative to the Resolute Onyx (Medtronic) device reached significance, according to Rafael Romaguera, MD, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at the Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona.

At 1 year, the rates of TLF were 7.2% and 10.5% for the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stents, respectively. On the basis of noninferiority, the 3.73% reduction in TLF at 1 year among those receiving the Cre8 EVO device provided a highly significant confirmation of noninferiority (P < .001) and triggered the preplanned superiority analysis.

When the significant advantage on the TLF endpoint (P = .03) was broken down into its components, the Cre8 EVO stent was linked to numerically lower rates of cardiac death (2.1% vs. 2.7%), target vessel MI (5.3% vs. 7.2%), and target lesion revascularization (2.4% vs. 3.9%), according to the SUGAR (Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents in Diabetes) trial results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In a previous study comparing these devices, called the ReCre8 trial, the rates of TLF in an all-comer CAD population were similar at 1 year. When an updated 3-year analysis was presented earlier in 2021 at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies meeting, they remained similar.

Diabetes-centered trial was unmet need

The rationale for conducting a new trial limited to patients with diabetes was based on the greater risk in this population, according to Dr. Romaguera. He cited data that indicate the risk of major adverse cardiac events are about two times higher 2 years after stent implantation in patients with diabetes relative to those without, even when contemporary drug-eluting stents are used.

Both the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stent are drug eluting and employ contemporary architecture that provides the basis for marketing claims that they are suitable for complex patients; but they have differences.

“There are three features that I think differentiate the Cre8 EVO stent,” Dr. Romaguera reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

One is the absence of polymer, which contrasts with the permanent polymer of the Resolute device. This feature affects the dissolution of the anti-inflammatory drug and might be one explanation for the greater protection from ischemic events, according to Dr. Romaguera.

Another is the thickness of the struts, which range from 70 to 80 mm for the Cre8 EVO device and from 92 to 102 mm for the Resolute Onyx device. In experimental studies, strut thickness has been associated with greater risk of thrombus formation, although it is unclear if this modest difference is clinically significant.

Also important, the Cre8 EVO device employs sirolimus for an anti-inflammatory effect, while the Resolute Onyx elutes zotarolimus. Again, experimental evidence suggests a greater anti-inflammatory effect reduces the need for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT); that might offer a relative advantage in patients with an elevated risk of bleeding.

It is not clear whether all of these features contribute to the better results observed in this trial in diabetes patients, but Dr. Romaguera indicated that the lower risk of TLF with Cre8 EVO is not just statistically significant but also clinically meaningful.

In SUGAR, which included 23 centers in Spain, 1,175 patients with confirmed diabetes scheduled for percutaneous intervention (PCI) were randomized to one of the two stents. The study was purposely designed with very few exclusion criteria.

SUGAR trial employed all-comer design

“This was an all-comer design and there was no limitation in regard to clinical presentation, complexity, number of lesions, or other disease features,” said Dr. Romaguera. The major exclusions were a life expectancy of less than 2 years and a contraindication to taking DAPT for at least 1 month,

The patients were almost equally divided between those who had a non–ST-segment elevation MI) and those with chronic coronary artery disease, but patients with a STEMI, representing about 12% of the population, were included. Almost all of the patients (about 95%) had type 2 diabetes; nearly one-third were on insulin at the time of randomization.

According to Dr. Romaguera, “SUGAR is the first powered trial to compare new-generation drug-eluting stents in patients with diabetes,” and he emphasized the all-comer design in supporting its clinical relevance.

Several of those participating in discussion of the trial during the late-breaker session agreed. Although the moderator, Gregg Stone, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, expressed surprise that the trial “actually demonstrated superiority” given the difficulty of showing a difference between modern stents, he called the findings “remarkable.”

Others seemed to suggest that it would alter their practice.

“This study is sweet like sugar for us, because now we have a stent that is dedicated and fitted for the diabetic population,” said Gennaro Sardella, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome.

For Marc Etienne Jolicoeur, MD, an interventional cardiologist associated with Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the impressive findings was the early separation of the curves in favor of Cre8 EVO. Calling SUGAR a “fantastic trial,” he indicated that the progressive advantage over time reinforced his impression that the difference is real.

However, David Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta, was more circumspect. He did not express any criticisms of the trial, but he called for “a larger evidence base” before declaring the Cre8 EVO device a standard of care for patients with diabetes undergoing PCI.

The SUGAR results were published in the European Heart Journal at the time of presentation at the meeting.

The trial was funded by the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Dr. Romaguera reported financial relationships with Biotronik and Boston Scientific. Dr. Stone, has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing devices used in PCI. Dr. Sardella and Dr. Jolicoeur reported no financial relationships relevant to this topic. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

Designed to show noninferiority for treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with diabetes, a head-to-head comparison of contemporary stents ended up showing that one was superior to the for the primary endpoint of target lesion failure (TLF).

In the superiority analysis, the 35% relative reduction in the risk of TLF at 1 year for the Cre8 EVO (Alvimedica) stent relative to the Resolute Onyx (Medtronic) device reached significance, according to Rafael Romaguera, MD, PhD, an interventional cardiologist at the Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona.

At 1 year, the rates of TLF were 7.2% and 10.5% for the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stents, respectively. On the basis of noninferiority, the 3.73% reduction in TLF at 1 year among those receiving the Cre8 EVO device provided a highly significant confirmation of noninferiority (P < .001) and triggered the preplanned superiority analysis.

When the significant advantage on the TLF endpoint (P = .03) was broken down into its components, the Cre8 EVO stent was linked to numerically lower rates of cardiac death (2.1% vs. 2.7%), target vessel MI (5.3% vs. 7.2%), and target lesion revascularization (2.4% vs. 3.9%), according to the SUGAR (Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents in Diabetes) trial results presented at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, held virtually and live in Orlando and sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In a previous study comparing these devices, called the ReCre8 trial, the rates of TLF in an all-comer CAD population were similar at 1 year. When an updated 3-year analysis was presented earlier in 2021 at the Cardiovascular Research Technologies meeting, they remained similar.

Diabetes-centered trial was unmet need

The rationale for conducting a new trial limited to patients with diabetes was based on the greater risk in this population, according to Dr. Romaguera. He cited data that indicate the risk of major adverse cardiac events are about two times higher 2 years after stent implantation in patients with diabetes relative to those without, even when contemporary drug-eluting stents are used.

Both the Cre8 EVO and Resolute Onyx stent are drug eluting and employ contemporary architecture that provides the basis for marketing claims that they are suitable for complex patients; but they have differences.

“There are three features that I think differentiate the Cre8 EVO stent,” Dr. Romaguera reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

One is the absence of polymer, which contrasts with the permanent polymer of the Resolute device. This feature affects the dissolution of the anti-inflammatory drug and might be one explanation for the greater protection from ischemic events, according to Dr. Romaguera.

Another is the thickness of the struts, which range from 70 to 80 mm for the Cre8 EVO device and from 92 to 102 mm for the Resolute Onyx device. In experimental studies, strut thickness has been associated with greater risk of thrombus formation, although it is unclear if this modest difference is clinically significant.

Also important, the Cre8 EVO device employs sirolimus for an anti-inflammatory effect, while the Resolute Onyx elutes zotarolimus. Again, experimental evidence suggests a greater anti-inflammatory effect reduces the need for dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT); that might offer a relative advantage in patients with an elevated risk of bleeding.

It is not clear whether all of these features contribute to the better results observed in this trial in diabetes patients, but Dr. Romaguera indicated that the lower risk of TLF with Cre8 EVO is not just statistically significant but also clinically meaningful.

In SUGAR, which included 23 centers in Spain, 1,175 patients with confirmed diabetes scheduled for percutaneous intervention (PCI) were randomized to one of the two stents. The study was purposely designed with very few exclusion criteria.

SUGAR trial employed all-comer design

“This was an all-comer design and there was no limitation in regard to clinical presentation, complexity, number of lesions, or other disease features,” said Dr. Romaguera. The major exclusions were a life expectancy of less than 2 years and a contraindication to taking DAPT for at least 1 month,

The patients were almost equally divided between those who had a non–ST-segment elevation MI) and those with chronic coronary artery disease, but patients with a STEMI, representing about 12% of the population, were included. Almost all of the patients (about 95%) had type 2 diabetes; nearly one-third were on insulin at the time of randomization.

According to Dr. Romaguera, “SUGAR is the first powered trial to compare new-generation drug-eluting stents in patients with diabetes,” and he emphasized the all-comer design in supporting its clinical relevance.

Several of those participating in discussion of the trial during the late-breaker session agreed. Although the moderator, Gregg Stone, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, expressed surprise that the trial “actually demonstrated superiority” given the difficulty of showing a difference between modern stents, he called the findings “remarkable.”

Others seemed to suggest that it would alter their practice.

“This study is sweet like sugar for us, because now we have a stent that is dedicated and fitted for the diabetic population,” said Gennaro Sardella, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome.

For Marc Etienne Jolicoeur, MD, an interventional cardiologist associated with Duke University, Durham, N.C., one of the impressive findings was the early separation of the curves in favor of Cre8 EVO. Calling SUGAR a “fantastic trial,” he indicated that the progressive advantage over time reinforced his impression that the difference is real.

However, David Kandzari, MD, director of interventional cardiology, Piedmont Hart Institute, Atlanta, was more circumspect. He did not express any criticisms of the trial, but he called for “a larger evidence base” before declaring the Cre8 EVO device a standard of care for patients with diabetes undergoing PCI.

The SUGAR results were published in the European Heart Journal at the time of presentation at the meeting.

The trial was funded by the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Dr. Romaguera reported financial relationships with Biotronik and Boston Scientific. Dr. Stone, has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those developing devices used in PCI. Dr. Sardella and Dr. Jolicoeur reported no financial relationships relevant to this topic. Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Ablative Solutions and Medtronic.

FROM TCT 2021

COVID-19 has brought more complex, longer office visits

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

AHA dietary guidance cites structural challenges to heart-healthy patterns

In a new scientific statement on diet and lifestyle recommendations, the American Heart Association is highlighting, for the first time, structural challenges that impede the adoption of heart-healthy dietary patterns.

This is in addition to stressing aspects of diet that improve cardiovascular health and reduce cardiovascular risk, with an emphasis on dietary patterns and food-based guidance beyond naming individual foods or nutrients.

The 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health scientific statement, developed under Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, chair of the AHA writing group, provides 10 evidence-based guidance recommendations to promote cardiometabolic health.

“The way to make heart-healthy choices every day,” said Dr. Lichtenstein, of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston, in a statement, “is to step back, look at the environment in which you eat, whether it be at home, at work, during social interaction, and then identify what the best choices are. And if there are no good choices, then think about how you can modify your environment so that there are good choices.”

The statement, published in Circulation, underscores growing evidence that nutrition-related chronic diseases have maternal-nutritional origins, and that prevention of pediatric obesity is a key to preserving and prolonging ideal cardiovascular health.

The features are as follows:

- Adjust energy intake and expenditure to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. To counter the shift toward higher energy intake and more sedentary lifestyles over the past 3 decades, the statement recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week, adjusted for individual’s age, activity level, sex, and size.

- Eat plenty of fruits and vegetables; choose a wide variety. Observational and intervention studies document that dietary patterns rich in varied fruits and vegetables, with the exception of white potatoes, are linked to a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Also, whole fruits and vegetables, which more readily provide fiber and satiety, are preferred over juices.

- Choose whole grain foods and products made mostly with whole grains rather than refined grains. Evidence from observational, interventional, and clinical studies confirm the benefits of frequent consumption of whole grains over infrequent consumption or over refined grains in terms of CVD risk, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic risk factors, laxation, and gut microbiota.

- Choose healthy sources of protein, mostly from plants (legumes and nuts).

- Higher intake of legumes, which are rich in protein and fiber, is associated with lower CVD risk, while higher nut intake is associated with lower risks of CVD, CHD, and stroke mortality/incidence. Replacing animal-source foods with plant-source whole foods, beyond health benefits, lowers the diet’s carbon footprint. Meat alternatives are often ultraprocessed and evidence on their short- and long-term health effects is limited. Unsaturated fats are preferred, as are lean, nonprocessed meats.

- Use liquid plant oils rather than tropical oils (coconut, palm, and palm kernel), animal fats (butter and lard), and partially hydrogenated fats. Saturated and trans fats (animal and dairy fats, and partially hydrogenated fat) should be replaced with nontropical liquid plant oils. Evidence supports cardiovascular benefits of dietary unsaturated fats, especially polyunsaturated fats primarily from plant oils (e.g. soybean, corn, safflower and sunflower oils, walnuts, and flax seeds).

- Choose minimally processed foods instead of ultraprocessed foods. Because of their proven association with adverse health outcomes, including overweight and obesity, cardiometabolic disorders (type 2 diabetes, CVD), and all-cause mortality, the consumption of many ultraprocessed foods is of concern. Ultraprocessed foods include artificial colors and flavors and preservatives that promote shelf stability, preserve texture, and increase palatability. A general principle is to emphasize unprocessed or minimally processed foods.

- Minimize intake of beverages and foods with added sugars. Added sugars (commonly glucose, dextrose, sucrose, corn syrup, honey, maple syrup, and concentrated fruit juice) are tied to elevated risk for type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and excess body weight. Findings from meta-analyses on body weight and metabolic outcomes for replacing added sugars with low-energy sweeteners are mixed, and the possibility of reverse causality has been raised.

- Choose and prepare foods with little or no salt. In general, the effects of sodium reduction on blood pressure tend to be higher in Black people, middle-aged and older people, and those with hypertension. In the United States, the main combined sources of sodium intake are processed foods, those prepared outside the home, packaged foods, and restaurant foods. Potassium-enriched salts are a promising alternative.

- If you don’t drink alcohol, don’t start; if you choose to drink, limit intake.

- While relationships between alcohol intake and cardiovascular outcomes are complex, the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee recently concluded that those who do drink should consume no more than one drink per day and should not drink alcohol in binges; the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans continues to recommend no more than one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.

- Adhere to the guidance regardless in all settings. Food-based dietary guidance applies to all foods and beverages, regardless of where prepared, procured, and consumed. Policies should be enacted that encourage healthier default options (for example, whole grains, minimized sodium and sugar content).

Recognizing impediments

The AHA/ASA scientific statement closes with the declaration: “Creating an environment that facilitates, rather than impedes, adherence to heart-healthy dietary patterns among all individuals is a public health imperative.” It points to the National Institutes of Health’s 2020-2030 Strategic Plan for National Institutes of Health Nutrition Research, which focuses on precision nutrition as a means “to determine the impact on health of not only what individuals eat, but also of why, when, and how they eat throughout the life course.”

Ultimately, precision nutrition may provide personalized diets for CVD prevention. But the “food environment,” often conditioned by “rampant nutrition misinformation” through local, state, and federal practices and policies, may impede the adoption of heart-healthy dietary patterns. Factors such as targeted food marketing (for example, of processed food and beverages in minority neighborhoods), structural racism, neighborhood segregation, unhealthy built environments, and food insecurity create environments in which unhealthy foods are the default option.”

These factors compound adverse dietary and health effects, and underscore a need to “directly combat nutrition misinformation among the public and health care professionals.” They also explain why, despite widespread knowledge of heart-healthy dietary pattern components, little progress has been made in achieving dietary goals in the United States.

Dr. Lichtenstein’s office, in response to a request regarding AHA advocacy and consumer programs, provided the following links: Voices for Healthy Kids initiative site and choosing healthier processed foods and one on fresh, frozen, and canned fruits and vegetables.

Dr. Lichtenstein had no disclosures. Disclosures for the writing group members are included in the statement.

In a new scientific statement on diet and lifestyle recommendations, the American Heart Association is highlighting, for the first time, structural challenges that impede the adoption of heart-healthy dietary patterns.

This is in addition to stressing aspects of diet that improve cardiovascular health and reduce cardiovascular risk, with an emphasis on dietary patterns and food-based guidance beyond naming individual foods or nutrients.

The 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health scientific statement, developed under Alice H. Lichtenstein, DSc, chair of the AHA writing group, provides 10 evidence-based guidance recommendations to promote cardiometabolic health.

“The way to make heart-healthy choices every day,” said Dr. Lichtenstein, of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston, in a statement, “is to step back, look at the environment in which you eat, whether it be at home, at work, during social interaction, and then identify what the best choices are. And if there are no good choices, then think about how you can modify your environment so that there are good choices.”

The statement, published in Circulation, underscores growing evidence that nutrition-related chronic diseases have maternal-nutritional origins, and that prevention of pediatric obesity is a key to preserving and prolonging ideal cardiovascular health.

The features are as follows:

- Adjust energy intake and expenditure to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. To counter the shift toward higher energy intake and more sedentary lifestyles over the past 3 decades, the statement recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week, adjusted for individual’s age, activity level, sex, and size.

- Eat plenty of fruits and vegetables; choose a wide variety. Observational and intervention studies document that dietary patterns rich in varied fruits and vegetables, with the exception of white potatoes, are linked to a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Also, whole fruits and vegetables, which more readily provide fiber and satiety, are preferred over juices.

- Choose whole grain foods and products made mostly with whole grains rather than refined grains. Evidence from observational, interventional, and clinical studies confirm the benefits of frequent consumption of whole grains over infrequent consumption or over refined grains in terms of CVD risk, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic risk factors, laxation, and gut microbiota.

- Choose healthy sources of protein, mostly from plants (legumes and nuts).

- Higher intake of legumes, which are rich in protein and fiber, is associated with lower CVD risk, while higher nut intake is associated with lower risks of CVD, CHD, and stroke mortality/incidence. Replacing animal-source foods with plant-source whole foods, beyond health benefits, lowers the diet’s carbon footprint. Meat alternatives are often ultraprocessed and evidence on their short- and long-term health effects is limited. Unsaturated fats are preferred, as are lean, nonprocessed meats.