User login

Contact Dermatitis of the Hands: Is It Irritant or Allergic?

Hand dermatitis, also known as hand eczema, is common and affects a considerable number of individuals across all ages. The impact of hand dermatitis can be profound, as it can impair one’s ability to perform tasks at home and at work. As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been an increased focus on hand hygiene and subsequently hand dermatitis. There are many contributors to the severity of hand dermatitis, including genetic factors, immune reactions, and skin barrier disruption. In this column, we will explore irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) of the hands, including epidemiology, potential causes, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management.

Epidemiology

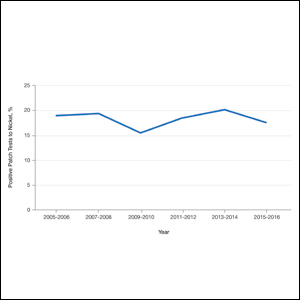

The prevalence of hand dermatitis in the general population is 3% to 4%, with a 1‐year prevalence of 10% and a lifetime prevalence of 15%.1 In a Swedish study of patients self-reporting hand eczema, contact dermatitis comprised 57% of the total cases (N=1385); ICD accounted for 35% of cases followed by ACD in 22%.2 A recent study on hand dermatitis in North American specialty patch test clinics documented that the hands were the primary site of involvement in 24.2% of patients undergoing patch testing (N=37,113).3

The hands are particularly at risk for occupation-related contact dermatitis and are the primary site of involvement in 80% of cases, followed by the wrists and forearms.4 Occupations at greatest risk include cleaning, construction, metalworking, hairdressing, health care, housework, and mechanics.5 Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, occupational hand dermatitis was common; in a survey of inpatient nurses, the prevalence was 55% (N=167).6 More recently, a study from China demonstrated a 74.5% prevalence of hand dermatitis in frontline health care workers involved in COVID-19 patient care.7

Etiology of Hand ICD

The pathogenesis of ICD is multifactorial; although traditionally thought to be nonimmunologic, evidence has shown that it involves skin barrier disruption, infiltration by immunocompetent cells, and induction of inflammatory signal molecules. The degree of irritancy is related to the concentration, contact duration, and properties of the irritant. Irritant reactions can be acute, such as those following a single chemical exposure that results in a localized dermatitis, or chronic, such as after repetitive cumulative exposure to mild irritants such as soaps.

Hand hygiene products (eg, soaps, hand sanitizers) can be irritants and have recently gained notoriety given their increased use to prevent COVID-19 transmission.8,9 Specific irritants include iodophors, antimicrobial soaps (chlorhexidine gluconate, chloroxylenol, triclosan), surfactants, and detergents. Wolfe et al10 showed that detergent-based hand cleansing products had the highest association with ICD, which was thought to be due to their propensity to remove protective lipids and reduce moisture content in the stratum corneum. Although hand sanitizers are better tolerated than detergents, they can still contribute to ICD by stripping precious lipids and disrupting the skin barrier.11 Compared to ethanol, isopropanol and N-propanol cause more disruption of the stratum corneum.12 In addition, N-propanol has the same irritant potential as the detergent sodium lauryl sulfate.13 Thus, ethanol-based sanitizers may be better tolerated. Disinfectant surface wipes may include the irritant N-alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride. Conversely, hand and baby wipes are formulated specifically for the skin and may be less irritating.11

Occupational contributors to hand ICD include chemical exposures and frequent handwashing. Wet work, mechanical trauma, warm dry air, and prolonged use of occlusive gloves also are well-known irritants.4 Fine or coarse particles encountered in some occupations or hobbies (eg, sand, sawdust, metal filings, plastic) can cause mechanical irritation. Exposure to physical friction from repeated handling of metal components, paper, cardboard, fabric, or steering wheels also has been implicated in hand ICD. Other common categories of occupational irritants include hydrocarbons, such as oils and petroleum.5,14

In addition to environmental factors, atopic dermatitis is an important endogenous factor that increases the risk of ICD due to underlying deficiencies within the main lipid15 and structural16 barrier components. These deficiencies ultimately lead to a lower threshold for the activation of inflammation via water loss and a weakened barrier. Studies have demonstrated that atopic dermatitis increases the risk for developing hand ICD 2- to 4-fold.17

Etiology of Hand ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported that the top 5 clinically relevant hand allergens were methylisothiazolinone (MI), nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrance mix I.3 Similarly, the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies demonstrated that the most common hand allergens were nickel, preservatives (quaternium-15 and formaldehyde), fragrances, and cobalt.18 In health care workers, rubber accelerators often are relevant in patients with hand ACD.5,19 Hand hygiene products are known to contain potential allergens; a recent study demonstrated that the top 5 allergens in common hand sanitizers were tocopherol, fragrance, propylene glycol, benzoates, and cetylstearyl alcohol,20 whereas the most common allergens in hand cleansers were fragrance, tocopherol, sodium benzoate, chloroxylenol, propylene glycol, and chlorhexidine gluconate.21

Preservatives

Preservatives can contribute to hand ACD. Methylisothiazolinone was the most commonly relevant allergen in a recent North American study of hand contact allergy,3 and a study of North American products confirmed its presence in dishwashing products (64%), shampoos (53%), household cleaners (47%), laundry softeners/additives (30%), soaps and cleansers (29%), and surface disinfectants (27%).22 In addition, in a study of 139 patients with refractory MI contact allergy, the hands were the most common site (69%) and had the highest rate of relapse.23 Because of the common presence of this preservative in liquid-based personal care products, patients with MI hand contact allergy need to be vigilant.

The same North American study highlighted formaldehyde and the formaldehyde releaser quaternium-15 as commonly relevant hand contact allergens.3 Formaldehyde is not commonly found in personal care products, but formaldehyde-releasing preservatives frequently are found in cosmetic products, topical medicaments, detergents, soaps, and metal working fluids. Another study noted that the most relevant contact allergen in health care workers was quaternium-15, possibly due to increased hand hygiene and exposure to medical products used for patient care.24,25

Metals

Nickel is used in metal objects and is found in many workplaces in the form of machines, office supplies, tools, electronics, uniforms, and jewelry. Occupationally related nickel ACD of the hands is most common in hairdressers/barbers/cosmetologists,26 which is not surprising, as hairdressing tools such as scissors and hair clips can release nickel.27,28

Although nickel contact allergy is more common than cobalt, these metals frequently co-react, with up to 25% of nickel-sensitive patients also having positive patch test reactions to cobalt.29 Because cobalt is contained in alloys, the occupations most at risk pertain to hard metal manufacturing. Furthermore, cobalt is used in dentistry for dental tools, fillings, crowns, bridges, and dentures.30 Cobalt also has been identified in leather, and leather gloves have been implicated in hand ACD.31

Fragrances

Fragrances can be added to products to infuse pleasing aromas or mask unpleasant chemical odors. In the North American study of hand ACD, fragrance mix I and balsam of Peru were the sixth and seventh most clinically relevant allergens, respectively.3 In another study, fragrances were found in 50% of waterless cleansers and 95% of rinse-off soaps and were the second most common allergens found in skin disinfectants.21 Fragrance is ubiquitous in personal care and cleansing products, which can make avoidance difficult.

Rubber Accelerators

Contact allergy to rubber additives in medical gloves is the most common cause of occupational hand ACD in health care workers.5,19 Importantly, it usually is rubber accelerators that act as allergens in hand ACD and not natural rubber latex. Rubber accelerators known to cause ACD include thiurams, carbamates, 1,3-diphenylguanidine (DPG), mixed dialkyl thioureas, and benzothiazoles.32 In the setting of hand ACD in North America, reactions to thiuram mix and carba mix were the most common.3 Notably, DPG is a component of carba mix and can be present in rubber gloves. It has been shown that 40.3% of DPG reactions are missed by testing with carba mix alone; therefore, DPG must be patch tested separately.33

Clinical Examination

It can be challenging to differentiate between hand ICD and ACD based on clinical appearance alone, and patch testing often is necessary for diagnosis. In the acute phase, both ICD and ACD can present as erythema, papules, vesicles, bullae, and/or crusting. In the chronic phase, scaling, lichenification, and/or fissures tend to prevail. Both acute and chronic ICD and ACD can be associated with pruritus and pain; however, ICD may be more likely associated with a burning or painful sensation, whereas ACD may be more associated with pruritus.

Other dermatoses may present as hand eruptions and should be kept in the differential diagnosis. Atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, dyshidrotic eczema, hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis, keratolysis exfoliativa, and palmoplantar pustulosis are other common causes of hand eruptions.5,34

Patch Testing for Hand ACD

Consider patch testing for hand dermatitis that is refractory to conservative treatment. Patients with new-onset hand dermatitis without history of atopy and patients with a new worsening of chronic hand dermatitis also may need patch testing.

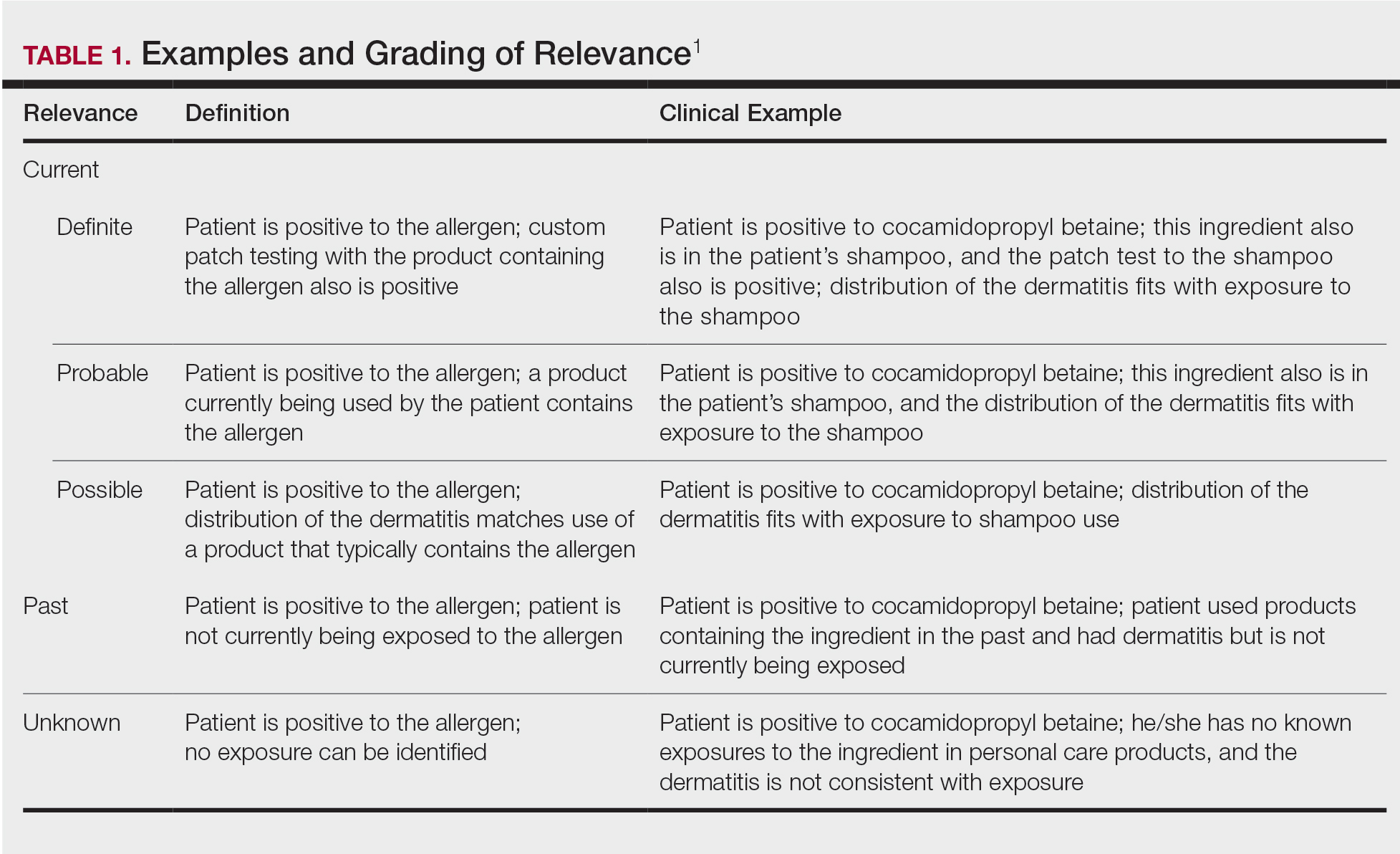

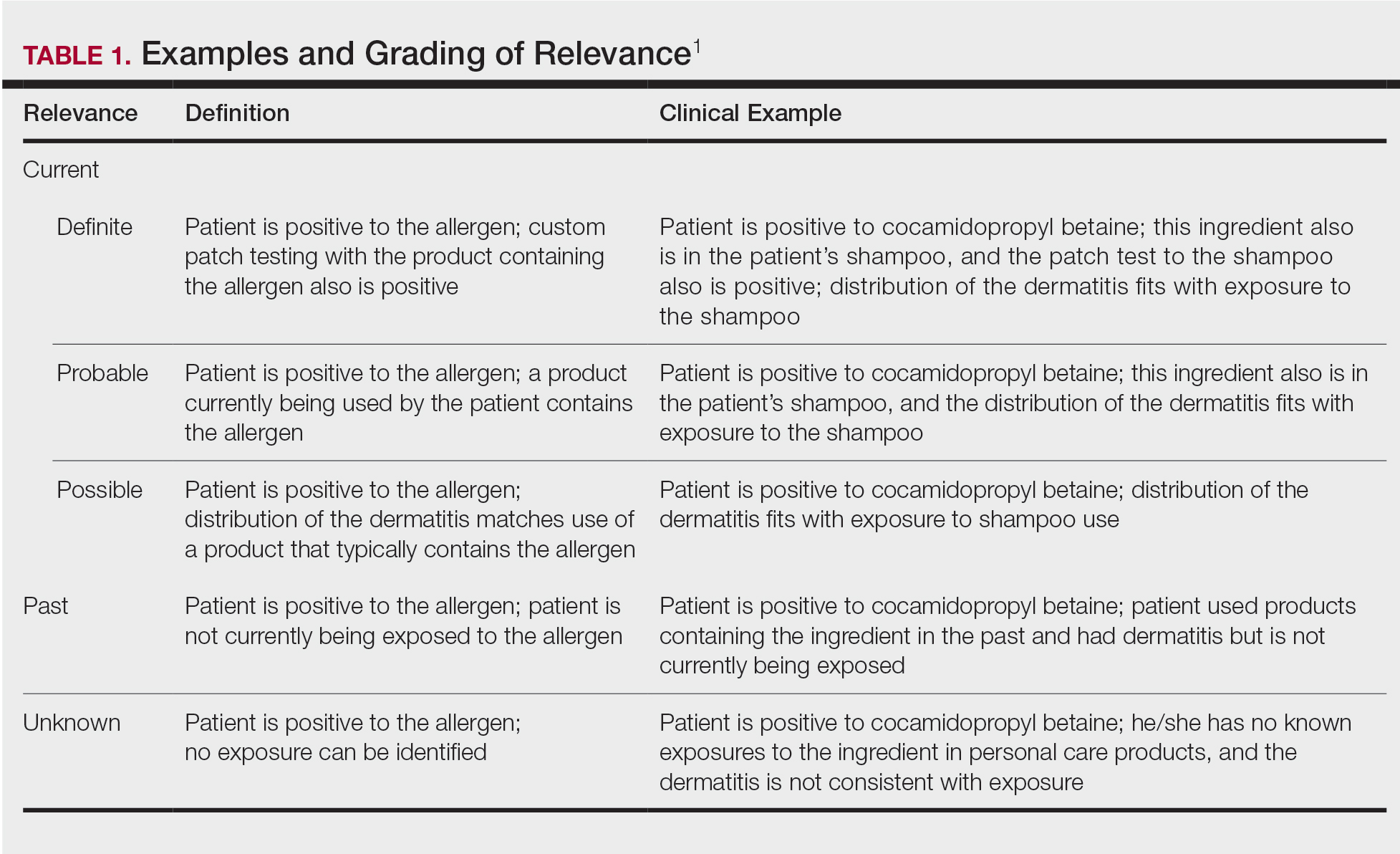

In addition to a medically appropriate screening series, patients with hand dermatitis often need supplemental patch testing. In a series of 37,113 patients with hand ACD, just over 20% of patients had positive patch test reactions to at least 1 supplemental allergen not on the screening series.3 Supplemental series should be selected based on the patient’s history and exposures; for example, nail salon technicians may need supplemental testing with the nail acrylate series, and massage therapists may need additional testing with the fragrance or essential oil series. Some of the most common supplemental series used for evaluation of hand dermatitis are the rubber, cosmetic, textile and dyes, plant, fragrance, essential oil, oil and coolants, nail or printing acrylates, and hairdressing series. If there is a high suspicion of occupational contact with allergens, obtaining material safety data sheets from the patient’s employer can be helpful to identify relevant allergens for testing.5 The thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test may miss several common and relevant hand allergens, including benzalkonium chloride, lanolin, and iodopropynyl butylcarbamate.3

Management

Management of hand ICD requires avoidance of irritants and proper hand hygiene practices.10,34 The hands should be washed using lukewarm water and mild fragrance-free soaps or cleansers,35 keeping in mind that hand sanitizers may be better tolerated due to their lower lipid-stripping effects. The moisturizers with the best efficacy are combinations of humectants (topical urea, glycerin) and occlusive emollients (dimethicone, petrolatum).11 When wet work is necessary, gloves should be worn; however, sweat and humidity from glove use can worsen ICD, and gloves should be changed regularly and applied only when hands are dry. Cotton gloves also can be worn underneath rubber gloves to prevent maceration from sweat.9

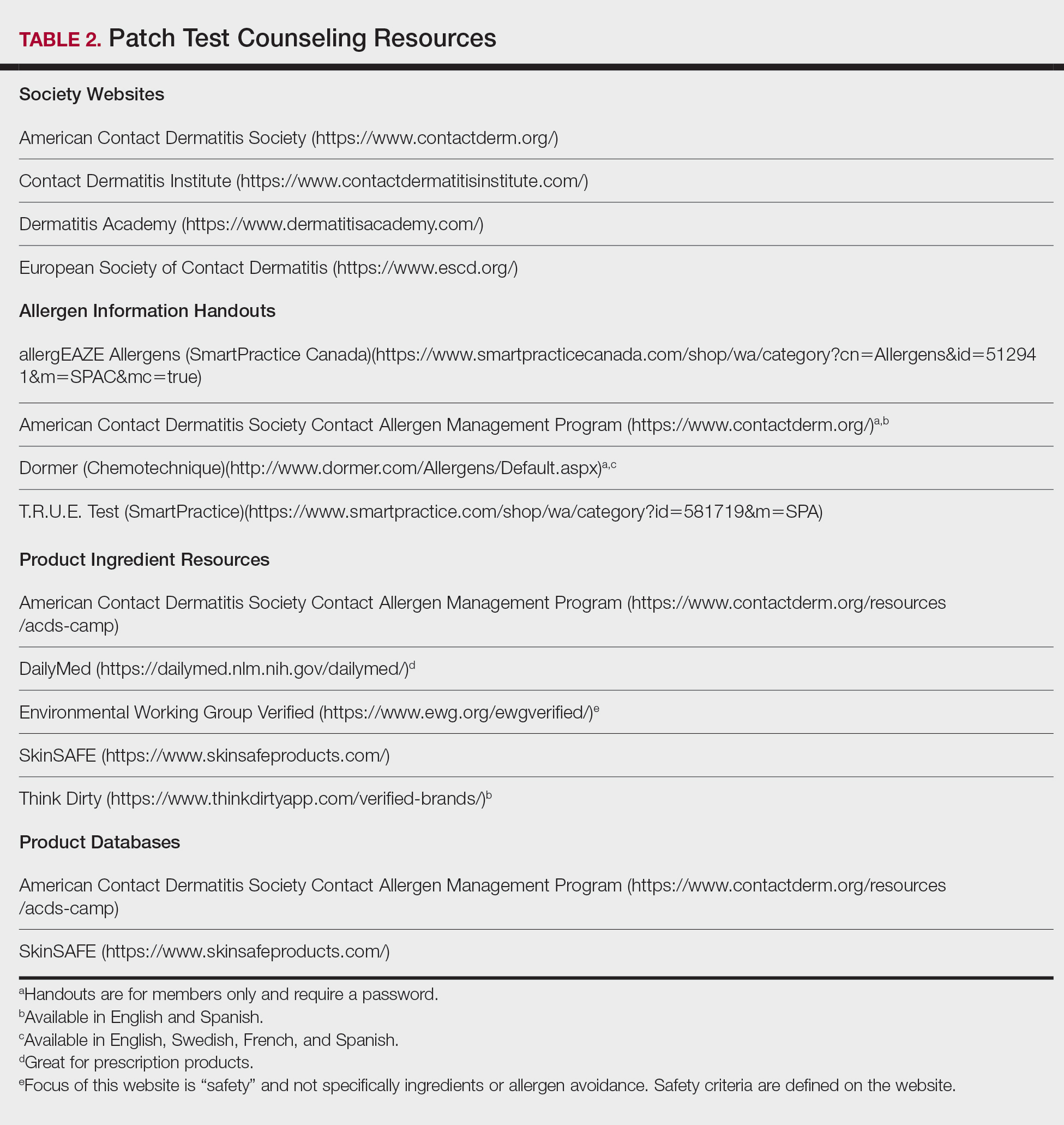

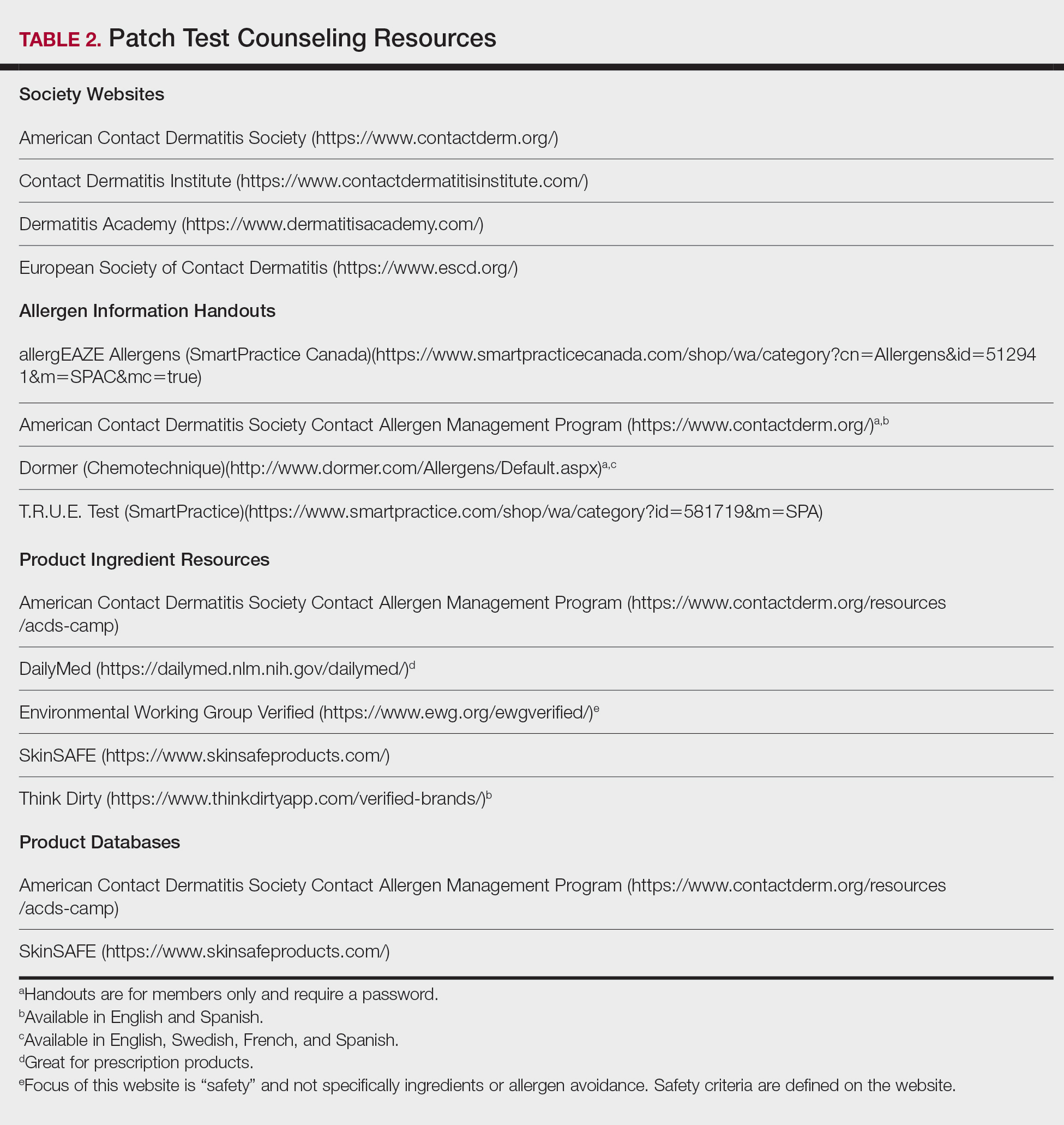

The mainstay of hand ACD management is allergen avoidance. The American Contact Dermatitis Society maintains the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP), a database that identifies products that do not contain patient allergens. The importance of reading ingredient labels of products should always be emphasized. For patients with rubber accelerator allergies, vinyl or accelerator-free gloves may be used. If the allergen is occupational, communication with the patient’s employer is necessary.5

When hand contact dermatitis does not improve with avoidance of irritants and allergens as well as gentle skin care, topical therapy, phototherapy, and in some cases systemic therapy may be required. High-potency topical corticosteroids or short courses of prednisone may be needed for quick relief. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole have shown some efficacy for hand dermatitis and can be used as steroid-sparing agents.36,37 Narrowband UVB and UVA have been used with moderate efficacy to treat resistant hand dermatitis.34,38 Oral immunosuppressant medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and cyclosporine can be used for more severe cases.34,39,40 Furthermore, oral retinoids have been used for chronic severe hand dermatitis with notable efficacy.41

Our Final Interpretation

The 2 major types of hand contact dermatitis are ICD and ACD. Hand ICD is more common than ACD in both occupational and nonoccupational settings. The hands are the most common sites in the setting of occupational dermatitis; in North American patch test populations, the hands were the primary site of involvement in just under 25% of patients.3 Many hand hygiene products contain irritants and allergens. The lipid-stripping effects of soaps, detergents, and hand sanitizers in conjunction with increased frequency of handwashing can trigger ICD. The most common allergens implicated in hand ACD include MI, nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrances. Patch testing is important for diagnosis, and supplemental series should be considered. Management includes avoidance of irritants and allergens; liberal use of moisturizers and barrier creams; and prescription topical therapy, phototherapy, or systemic therapy when indicated.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, et al. The epidemiology of hand eczema in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:75-87.

- Meding B, Swanbeck G. Epidemiology of different types of hand eczema in an industrial city. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:227-233.

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Atwater AR, et al. Hand dermatitis in adults referred for patch testing: analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2000–2016 [published online November 28, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.054

- Sasseville D. Occupational contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:59.

- Lampel HP, Powell HB. Occupational and hand dermatitis: a practical approach. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:60-71.

- Lampel HP, Patel N, Boyse K, et al. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in inpatient nurses at a United States hospital. Dermatitis. 2007;18:140-142.

- Lan J, Song Z, Miao X, et al. Skin damage among health care workers managing coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1215-1216.

- Wei Tan S, Chiat Oh C. Contact dermatitis from hand hygiene practices in the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020;49:674-676.

- Beiu C, Mihai M, Popa L, et al. Frequent hand washing for COVID-19 prevention can cause hand dermatitis: management tips. Cureus. 2020;12:E7506.

- Wolfe MK, Wells E, Mitro B, et al. Seeking clearer recommendations for hand hygiene in communities facing ebola: a randomized trial investigating the impact of six handwashing methods on skin irritation and dermatitis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167378.

- Rundle CW, Presley CL, Militello M, et al. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1730-1737.

- Cartner T, Brand N, Tian K, et al. Effect of different alcohols on stratum corneum kallikrein 5 and phospholipase A(2) together with epidermal keratinocytes and skin irritation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39:188-196.

- Clemmensen A, Andersen F, Petersen TK, et al. The irritant potential of n-propanol (nonanoic acid vehicle) in cumulative skin irritation: a validation study of two different human in vivo test models. Ski Res Technol. 2008;14:277-286.

- McMullen E, Gawkrodger DJ. Physical friction is under-recognized as an irritant that can cause or contribute to contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:154-156.

- Macheleidt O, Kaiser HW, Sandhoff K. Deficiency of epidermal protein-bound omega-hydroxyceramides in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:166-173.

- Visser MJ, Landeck L, Campbell LE, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis and loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene on the development of occupational irritant contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:326-332.

- Coenraads PJ, Diepgen TL. Risk for hand eczema in employees with past or present atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1998;71:7-13.

- Oosterhaven JAF, Uter W, Aberer W, et al. European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (ESSCA): contact allergies in relation to body sites in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:263-272.

- Goodier MC, Ronkainen SD, Hylwa SA. Rubber accelerators in medical examination and surgical gloves. Dermatitis. 2018;29:66-76.

- Voller LM, Schlarbaum JP, Hylwa SA. Allergenic ingredients in health care hand sanitizers in the United States [published online February 21, 2020]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000567

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Atwater AR. Allergens in medical hand skin cleansers. Dermatitis. 2019;30:336-341.

- Scheman A, Severson D. American Contact Dermatitis Society Contact Allergy Management Program: an epidemiologic tool to quantify ingredient usage. Dermatitis. 2016;27:11-13.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Kadivar S, Belsito DV. Occupational dermatitis in health care workers evaluated for suspected allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2015;26:177-183.

- Prodi A, Rui F, Fortina AB, et al. Healthcare workers and skin sensitization: north-eastern Italian database. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2016;66:72-74.

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Dekoven JG, et al. Occupationally related nickel reactions: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data 1998-2016. Dermatitis. 2019;30:306-313.

- Thyssen JP, Milting K, Bregnhøj A, et al. Nickel allergy in patch-tested female hairdressers and assessment of nickel release from hairdressers’ scissors and crochet hooks. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:281-286.

- Symanzik C, John SM, Strunk M. Nickel release from metal tools in the German hairdressing trade—a current analysis. 2019;80:382-385.

- Rystedt I, Fischer T. Relationship between nickel and cobalt sensitization in hard metal workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:195-200.

- Kettelarij JAB, Lidén C, Axén E, et al. Cobalt, nickel and chromium release from dental tools and alloys. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:3-10.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Jellesen MS, et al. Consumer leather exposure: an unrecognized cause of cobalt sensitization. 2013;69:276-279.

- Hamnerius N, Svedman C, Bergendorff O, et al. Hand eczema and occupational contact allergies in healthcare workers with a focus on rubber additives. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:149-156.

- Warshaw EM, Gupta R, Dekoven JG, et al. Patch testing to diphenylguanidine by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (2013-2016). Dermatitis. 2020;31:350-358.

- Perry AD, Trafeli JP. Hand dermatitis: review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:325-330.

- Abtahi-Naeini B. Frequent handwashing amidst the COVID-19 outbreak: prevention of hand irritant contact dermatitis and other considerations. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3:E163.

- Schliemann S, Kelterer D, Bauer A, et al. Tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of occupationally induced chronic hand dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:299-306. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01314.x

- Lynde CW, Bergman J, Fiorillo L, et al. Use of topical crisaborole for treating dermatitis in a variety of dermatology settings. Skin Therapy Lett. Published June 1, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.skintherapyletter.com/dermatology/topical-crisaborole-dermatitis-treatment/

- Rosén K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. Chronic eczematous dermatitis of the hands: a comparison of PUVA and UVB treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67:48-54.

- Kwon GP, Tan CZ, Chen JK. Hand dermatitis: utilizing subtype classification to direct intervention. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2016;3:322-332.

- Warshaw E, Lee G, Storrs FJ. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, therapeutic options, and long-term outcomes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:119-137.

- Song M, Lee H-J, Lee W-K, et al. Acitretin as a therapeutic option for chronic hand eczema. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:385-387.

Hand dermatitis, also known as hand eczema, is common and affects a considerable number of individuals across all ages. The impact of hand dermatitis can be profound, as it can impair one’s ability to perform tasks at home and at work. As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been an increased focus on hand hygiene and subsequently hand dermatitis. There are many contributors to the severity of hand dermatitis, including genetic factors, immune reactions, and skin barrier disruption. In this column, we will explore irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) of the hands, including epidemiology, potential causes, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of hand dermatitis in the general population is 3% to 4%, with a 1‐year prevalence of 10% and a lifetime prevalence of 15%.1 In a Swedish study of patients self-reporting hand eczema, contact dermatitis comprised 57% of the total cases (N=1385); ICD accounted for 35% of cases followed by ACD in 22%.2 A recent study on hand dermatitis in North American specialty patch test clinics documented that the hands were the primary site of involvement in 24.2% of patients undergoing patch testing (N=37,113).3

The hands are particularly at risk for occupation-related contact dermatitis and are the primary site of involvement in 80% of cases, followed by the wrists and forearms.4 Occupations at greatest risk include cleaning, construction, metalworking, hairdressing, health care, housework, and mechanics.5 Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, occupational hand dermatitis was common; in a survey of inpatient nurses, the prevalence was 55% (N=167).6 More recently, a study from China demonstrated a 74.5% prevalence of hand dermatitis in frontline health care workers involved in COVID-19 patient care.7

Etiology of Hand ICD

The pathogenesis of ICD is multifactorial; although traditionally thought to be nonimmunologic, evidence has shown that it involves skin barrier disruption, infiltration by immunocompetent cells, and induction of inflammatory signal molecules. The degree of irritancy is related to the concentration, contact duration, and properties of the irritant. Irritant reactions can be acute, such as those following a single chemical exposure that results in a localized dermatitis, or chronic, such as after repetitive cumulative exposure to mild irritants such as soaps.

Hand hygiene products (eg, soaps, hand sanitizers) can be irritants and have recently gained notoriety given their increased use to prevent COVID-19 transmission.8,9 Specific irritants include iodophors, antimicrobial soaps (chlorhexidine gluconate, chloroxylenol, triclosan), surfactants, and detergents. Wolfe et al10 showed that detergent-based hand cleansing products had the highest association with ICD, which was thought to be due to their propensity to remove protective lipids and reduce moisture content in the stratum corneum. Although hand sanitizers are better tolerated than detergents, they can still contribute to ICD by stripping precious lipids and disrupting the skin barrier.11 Compared to ethanol, isopropanol and N-propanol cause more disruption of the stratum corneum.12 In addition, N-propanol has the same irritant potential as the detergent sodium lauryl sulfate.13 Thus, ethanol-based sanitizers may be better tolerated. Disinfectant surface wipes may include the irritant N-alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride. Conversely, hand and baby wipes are formulated specifically for the skin and may be less irritating.11

Occupational contributors to hand ICD include chemical exposures and frequent handwashing. Wet work, mechanical trauma, warm dry air, and prolonged use of occlusive gloves also are well-known irritants.4 Fine or coarse particles encountered in some occupations or hobbies (eg, sand, sawdust, metal filings, plastic) can cause mechanical irritation. Exposure to physical friction from repeated handling of metal components, paper, cardboard, fabric, or steering wheels also has been implicated in hand ICD. Other common categories of occupational irritants include hydrocarbons, such as oils and petroleum.5,14

In addition to environmental factors, atopic dermatitis is an important endogenous factor that increases the risk of ICD due to underlying deficiencies within the main lipid15 and structural16 barrier components. These deficiencies ultimately lead to a lower threshold for the activation of inflammation via water loss and a weakened barrier. Studies have demonstrated that atopic dermatitis increases the risk for developing hand ICD 2- to 4-fold.17

Etiology of Hand ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported that the top 5 clinically relevant hand allergens were methylisothiazolinone (MI), nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrance mix I.3 Similarly, the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies demonstrated that the most common hand allergens were nickel, preservatives (quaternium-15 and formaldehyde), fragrances, and cobalt.18 In health care workers, rubber accelerators often are relevant in patients with hand ACD.5,19 Hand hygiene products are known to contain potential allergens; a recent study demonstrated that the top 5 allergens in common hand sanitizers were tocopherol, fragrance, propylene glycol, benzoates, and cetylstearyl alcohol,20 whereas the most common allergens in hand cleansers were fragrance, tocopherol, sodium benzoate, chloroxylenol, propylene glycol, and chlorhexidine gluconate.21

Preservatives

Preservatives can contribute to hand ACD. Methylisothiazolinone was the most commonly relevant allergen in a recent North American study of hand contact allergy,3 and a study of North American products confirmed its presence in dishwashing products (64%), shampoos (53%), household cleaners (47%), laundry softeners/additives (30%), soaps and cleansers (29%), and surface disinfectants (27%).22 In addition, in a study of 139 patients with refractory MI contact allergy, the hands were the most common site (69%) and had the highest rate of relapse.23 Because of the common presence of this preservative in liquid-based personal care products, patients with MI hand contact allergy need to be vigilant.

The same North American study highlighted formaldehyde and the formaldehyde releaser quaternium-15 as commonly relevant hand contact allergens.3 Formaldehyde is not commonly found in personal care products, but formaldehyde-releasing preservatives frequently are found in cosmetic products, topical medicaments, detergents, soaps, and metal working fluids. Another study noted that the most relevant contact allergen in health care workers was quaternium-15, possibly due to increased hand hygiene and exposure to medical products used for patient care.24,25

Metals

Nickel is used in metal objects and is found in many workplaces in the form of machines, office supplies, tools, electronics, uniforms, and jewelry. Occupationally related nickel ACD of the hands is most common in hairdressers/barbers/cosmetologists,26 which is not surprising, as hairdressing tools such as scissors and hair clips can release nickel.27,28

Although nickel contact allergy is more common than cobalt, these metals frequently co-react, with up to 25% of nickel-sensitive patients also having positive patch test reactions to cobalt.29 Because cobalt is contained in alloys, the occupations most at risk pertain to hard metal manufacturing. Furthermore, cobalt is used in dentistry for dental tools, fillings, crowns, bridges, and dentures.30 Cobalt also has been identified in leather, and leather gloves have been implicated in hand ACD.31

Fragrances

Fragrances can be added to products to infuse pleasing aromas or mask unpleasant chemical odors. In the North American study of hand ACD, fragrance mix I and balsam of Peru were the sixth and seventh most clinically relevant allergens, respectively.3 In another study, fragrances were found in 50% of waterless cleansers and 95% of rinse-off soaps and were the second most common allergens found in skin disinfectants.21 Fragrance is ubiquitous in personal care and cleansing products, which can make avoidance difficult.

Rubber Accelerators

Contact allergy to rubber additives in medical gloves is the most common cause of occupational hand ACD in health care workers.5,19 Importantly, it usually is rubber accelerators that act as allergens in hand ACD and not natural rubber latex. Rubber accelerators known to cause ACD include thiurams, carbamates, 1,3-diphenylguanidine (DPG), mixed dialkyl thioureas, and benzothiazoles.32 In the setting of hand ACD in North America, reactions to thiuram mix and carba mix were the most common.3 Notably, DPG is a component of carba mix and can be present in rubber gloves. It has been shown that 40.3% of DPG reactions are missed by testing with carba mix alone; therefore, DPG must be patch tested separately.33

Clinical Examination

It can be challenging to differentiate between hand ICD and ACD based on clinical appearance alone, and patch testing often is necessary for diagnosis. In the acute phase, both ICD and ACD can present as erythema, papules, vesicles, bullae, and/or crusting. In the chronic phase, scaling, lichenification, and/or fissures tend to prevail. Both acute and chronic ICD and ACD can be associated with pruritus and pain; however, ICD may be more likely associated with a burning or painful sensation, whereas ACD may be more associated with pruritus.

Other dermatoses may present as hand eruptions and should be kept in the differential diagnosis. Atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, dyshidrotic eczema, hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis, keratolysis exfoliativa, and palmoplantar pustulosis are other common causes of hand eruptions.5,34

Patch Testing for Hand ACD

Consider patch testing for hand dermatitis that is refractory to conservative treatment. Patients with new-onset hand dermatitis without history of atopy and patients with a new worsening of chronic hand dermatitis also may need patch testing.

In addition to a medically appropriate screening series, patients with hand dermatitis often need supplemental patch testing. In a series of 37,113 patients with hand ACD, just over 20% of patients had positive patch test reactions to at least 1 supplemental allergen not on the screening series.3 Supplemental series should be selected based on the patient’s history and exposures; for example, nail salon technicians may need supplemental testing with the nail acrylate series, and massage therapists may need additional testing with the fragrance or essential oil series. Some of the most common supplemental series used for evaluation of hand dermatitis are the rubber, cosmetic, textile and dyes, plant, fragrance, essential oil, oil and coolants, nail or printing acrylates, and hairdressing series. If there is a high suspicion of occupational contact with allergens, obtaining material safety data sheets from the patient’s employer can be helpful to identify relevant allergens for testing.5 The thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test may miss several common and relevant hand allergens, including benzalkonium chloride, lanolin, and iodopropynyl butylcarbamate.3

Management

Management of hand ICD requires avoidance of irritants and proper hand hygiene practices.10,34 The hands should be washed using lukewarm water and mild fragrance-free soaps or cleansers,35 keeping in mind that hand sanitizers may be better tolerated due to their lower lipid-stripping effects. The moisturizers with the best efficacy are combinations of humectants (topical urea, glycerin) and occlusive emollients (dimethicone, petrolatum).11 When wet work is necessary, gloves should be worn; however, sweat and humidity from glove use can worsen ICD, and gloves should be changed regularly and applied only when hands are dry. Cotton gloves also can be worn underneath rubber gloves to prevent maceration from sweat.9

The mainstay of hand ACD management is allergen avoidance. The American Contact Dermatitis Society maintains the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP), a database that identifies products that do not contain patient allergens. The importance of reading ingredient labels of products should always be emphasized. For patients with rubber accelerator allergies, vinyl or accelerator-free gloves may be used. If the allergen is occupational, communication with the patient’s employer is necessary.5

When hand contact dermatitis does not improve with avoidance of irritants and allergens as well as gentle skin care, topical therapy, phototherapy, and in some cases systemic therapy may be required. High-potency topical corticosteroids or short courses of prednisone may be needed for quick relief. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole have shown some efficacy for hand dermatitis and can be used as steroid-sparing agents.36,37 Narrowband UVB and UVA have been used with moderate efficacy to treat resistant hand dermatitis.34,38 Oral immunosuppressant medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and cyclosporine can be used for more severe cases.34,39,40 Furthermore, oral retinoids have been used for chronic severe hand dermatitis with notable efficacy.41

Our Final Interpretation

The 2 major types of hand contact dermatitis are ICD and ACD. Hand ICD is more common than ACD in both occupational and nonoccupational settings. The hands are the most common sites in the setting of occupational dermatitis; in North American patch test populations, the hands were the primary site of involvement in just under 25% of patients.3 Many hand hygiene products contain irritants and allergens. The lipid-stripping effects of soaps, detergents, and hand sanitizers in conjunction with increased frequency of handwashing can trigger ICD. The most common allergens implicated in hand ACD include MI, nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrances. Patch testing is important for diagnosis, and supplemental series should be considered. Management includes avoidance of irritants and allergens; liberal use of moisturizers and barrier creams; and prescription topical therapy, phototherapy, or systemic therapy when indicated.

Hand dermatitis, also known as hand eczema, is common and affects a considerable number of individuals across all ages. The impact of hand dermatitis can be profound, as it can impair one’s ability to perform tasks at home and at work. As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been an increased focus on hand hygiene and subsequently hand dermatitis. There are many contributors to the severity of hand dermatitis, including genetic factors, immune reactions, and skin barrier disruption. In this column, we will explore irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) of the hands, including epidemiology, potential causes, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of hand dermatitis in the general population is 3% to 4%, with a 1‐year prevalence of 10% and a lifetime prevalence of 15%.1 In a Swedish study of patients self-reporting hand eczema, contact dermatitis comprised 57% of the total cases (N=1385); ICD accounted for 35% of cases followed by ACD in 22%.2 A recent study on hand dermatitis in North American specialty patch test clinics documented that the hands were the primary site of involvement in 24.2% of patients undergoing patch testing (N=37,113).3

The hands are particularly at risk for occupation-related contact dermatitis and are the primary site of involvement in 80% of cases, followed by the wrists and forearms.4 Occupations at greatest risk include cleaning, construction, metalworking, hairdressing, health care, housework, and mechanics.5 Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, occupational hand dermatitis was common; in a survey of inpatient nurses, the prevalence was 55% (N=167).6 More recently, a study from China demonstrated a 74.5% prevalence of hand dermatitis in frontline health care workers involved in COVID-19 patient care.7

Etiology of Hand ICD

The pathogenesis of ICD is multifactorial; although traditionally thought to be nonimmunologic, evidence has shown that it involves skin barrier disruption, infiltration by immunocompetent cells, and induction of inflammatory signal molecules. The degree of irritancy is related to the concentration, contact duration, and properties of the irritant. Irritant reactions can be acute, such as those following a single chemical exposure that results in a localized dermatitis, or chronic, such as after repetitive cumulative exposure to mild irritants such as soaps.

Hand hygiene products (eg, soaps, hand sanitizers) can be irritants and have recently gained notoriety given their increased use to prevent COVID-19 transmission.8,9 Specific irritants include iodophors, antimicrobial soaps (chlorhexidine gluconate, chloroxylenol, triclosan), surfactants, and detergents. Wolfe et al10 showed that detergent-based hand cleansing products had the highest association with ICD, which was thought to be due to their propensity to remove protective lipids and reduce moisture content in the stratum corneum. Although hand sanitizers are better tolerated than detergents, they can still contribute to ICD by stripping precious lipids and disrupting the skin barrier.11 Compared to ethanol, isopropanol and N-propanol cause more disruption of the stratum corneum.12 In addition, N-propanol has the same irritant potential as the detergent sodium lauryl sulfate.13 Thus, ethanol-based sanitizers may be better tolerated. Disinfectant surface wipes may include the irritant N-alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride. Conversely, hand and baby wipes are formulated specifically for the skin and may be less irritating.11

Occupational contributors to hand ICD include chemical exposures and frequent handwashing. Wet work, mechanical trauma, warm dry air, and prolonged use of occlusive gloves also are well-known irritants.4 Fine or coarse particles encountered in some occupations or hobbies (eg, sand, sawdust, metal filings, plastic) can cause mechanical irritation. Exposure to physical friction from repeated handling of metal components, paper, cardboard, fabric, or steering wheels also has been implicated in hand ICD. Other common categories of occupational irritants include hydrocarbons, such as oils and petroleum.5,14

In addition to environmental factors, atopic dermatitis is an important endogenous factor that increases the risk of ICD due to underlying deficiencies within the main lipid15 and structural16 barrier components. These deficiencies ultimately lead to a lower threshold for the activation of inflammation via water loss and a weakened barrier. Studies have demonstrated that atopic dermatitis increases the risk for developing hand ICD 2- to 4-fold.17

Etiology of Hand ACD

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immune-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported that the top 5 clinically relevant hand allergens were methylisothiazolinone (MI), nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrance mix I.3 Similarly, the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies demonstrated that the most common hand allergens were nickel, preservatives (quaternium-15 and formaldehyde), fragrances, and cobalt.18 In health care workers, rubber accelerators often are relevant in patients with hand ACD.5,19 Hand hygiene products are known to contain potential allergens; a recent study demonstrated that the top 5 allergens in common hand sanitizers were tocopherol, fragrance, propylene glycol, benzoates, and cetylstearyl alcohol,20 whereas the most common allergens in hand cleansers were fragrance, tocopherol, sodium benzoate, chloroxylenol, propylene glycol, and chlorhexidine gluconate.21

Preservatives

Preservatives can contribute to hand ACD. Methylisothiazolinone was the most commonly relevant allergen in a recent North American study of hand contact allergy,3 and a study of North American products confirmed its presence in dishwashing products (64%), shampoos (53%), household cleaners (47%), laundry softeners/additives (30%), soaps and cleansers (29%), and surface disinfectants (27%).22 In addition, in a study of 139 patients with refractory MI contact allergy, the hands were the most common site (69%) and had the highest rate of relapse.23 Because of the common presence of this preservative in liquid-based personal care products, patients with MI hand contact allergy need to be vigilant.

The same North American study highlighted formaldehyde and the formaldehyde releaser quaternium-15 as commonly relevant hand contact allergens.3 Formaldehyde is not commonly found in personal care products, but formaldehyde-releasing preservatives frequently are found in cosmetic products, topical medicaments, detergents, soaps, and metal working fluids. Another study noted that the most relevant contact allergen in health care workers was quaternium-15, possibly due to increased hand hygiene and exposure to medical products used for patient care.24,25

Metals

Nickel is used in metal objects and is found in many workplaces in the form of machines, office supplies, tools, electronics, uniforms, and jewelry. Occupationally related nickel ACD of the hands is most common in hairdressers/barbers/cosmetologists,26 which is not surprising, as hairdressing tools such as scissors and hair clips can release nickel.27,28

Although nickel contact allergy is more common than cobalt, these metals frequently co-react, with up to 25% of nickel-sensitive patients also having positive patch test reactions to cobalt.29 Because cobalt is contained in alloys, the occupations most at risk pertain to hard metal manufacturing. Furthermore, cobalt is used in dentistry for dental tools, fillings, crowns, bridges, and dentures.30 Cobalt also has been identified in leather, and leather gloves have been implicated in hand ACD.31

Fragrances

Fragrances can be added to products to infuse pleasing aromas or mask unpleasant chemical odors. In the North American study of hand ACD, fragrance mix I and balsam of Peru were the sixth and seventh most clinically relevant allergens, respectively.3 In another study, fragrances were found in 50% of waterless cleansers and 95% of rinse-off soaps and were the second most common allergens found in skin disinfectants.21 Fragrance is ubiquitous in personal care and cleansing products, which can make avoidance difficult.

Rubber Accelerators

Contact allergy to rubber additives in medical gloves is the most common cause of occupational hand ACD in health care workers.5,19 Importantly, it usually is rubber accelerators that act as allergens in hand ACD and not natural rubber latex. Rubber accelerators known to cause ACD include thiurams, carbamates, 1,3-diphenylguanidine (DPG), mixed dialkyl thioureas, and benzothiazoles.32 In the setting of hand ACD in North America, reactions to thiuram mix and carba mix were the most common.3 Notably, DPG is a component of carba mix and can be present in rubber gloves. It has been shown that 40.3% of DPG reactions are missed by testing with carba mix alone; therefore, DPG must be patch tested separately.33

Clinical Examination

It can be challenging to differentiate between hand ICD and ACD based on clinical appearance alone, and patch testing often is necessary for diagnosis. In the acute phase, both ICD and ACD can present as erythema, papules, vesicles, bullae, and/or crusting. In the chronic phase, scaling, lichenification, and/or fissures tend to prevail. Both acute and chronic ICD and ACD can be associated with pruritus and pain; however, ICD may be more likely associated with a burning or painful sensation, whereas ACD may be more associated with pruritus.

Other dermatoses may present as hand eruptions and should be kept in the differential diagnosis. Atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, dyshidrotic eczema, hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis, keratolysis exfoliativa, and palmoplantar pustulosis are other common causes of hand eruptions.5,34

Patch Testing for Hand ACD

Consider patch testing for hand dermatitis that is refractory to conservative treatment. Patients with new-onset hand dermatitis without history of atopy and patients with a new worsening of chronic hand dermatitis also may need patch testing.

In addition to a medically appropriate screening series, patients with hand dermatitis often need supplemental patch testing. In a series of 37,113 patients with hand ACD, just over 20% of patients had positive patch test reactions to at least 1 supplemental allergen not on the screening series.3 Supplemental series should be selected based on the patient’s history and exposures; for example, nail salon technicians may need supplemental testing with the nail acrylate series, and massage therapists may need additional testing with the fragrance or essential oil series. Some of the most common supplemental series used for evaluation of hand dermatitis are the rubber, cosmetic, textile and dyes, plant, fragrance, essential oil, oil and coolants, nail or printing acrylates, and hairdressing series. If there is a high suspicion of occupational contact with allergens, obtaining material safety data sheets from the patient’s employer can be helpful to identify relevant allergens for testing.5 The thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test may miss several common and relevant hand allergens, including benzalkonium chloride, lanolin, and iodopropynyl butylcarbamate.3

Management

Management of hand ICD requires avoidance of irritants and proper hand hygiene practices.10,34 The hands should be washed using lukewarm water and mild fragrance-free soaps or cleansers,35 keeping in mind that hand sanitizers may be better tolerated due to their lower lipid-stripping effects. The moisturizers with the best efficacy are combinations of humectants (topical urea, glycerin) and occlusive emollients (dimethicone, petrolatum).11 When wet work is necessary, gloves should be worn; however, sweat and humidity from glove use can worsen ICD, and gloves should be changed regularly and applied only when hands are dry. Cotton gloves also can be worn underneath rubber gloves to prevent maceration from sweat.9

The mainstay of hand ACD management is allergen avoidance. The American Contact Dermatitis Society maintains the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP), a database that identifies products that do not contain patient allergens. The importance of reading ingredient labels of products should always be emphasized. For patients with rubber accelerator allergies, vinyl or accelerator-free gloves may be used. If the allergen is occupational, communication with the patient’s employer is necessary.5

When hand contact dermatitis does not improve with avoidance of irritants and allergens as well as gentle skin care, topical therapy, phototherapy, and in some cases systemic therapy may be required. High-potency topical corticosteroids or short courses of prednisone may be needed for quick relief. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) and the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole have shown some efficacy for hand dermatitis and can be used as steroid-sparing agents.36,37 Narrowband UVB and UVA have been used with moderate efficacy to treat resistant hand dermatitis.34,38 Oral immunosuppressant medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and cyclosporine can be used for more severe cases.34,39,40 Furthermore, oral retinoids have been used for chronic severe hand dermatitis with notable efficacy.41

Our Final Interpretation

The 2 major types of hand contact dermatitis are ICD and ACD. Hand ICD is more common than ACD in both occupational and nonoccupational settings. The hands are the most common sites in the setting of occupational dermatitis; in North American patch test populations, the hands were the primary site of involvement in just under 25% of patients.3 Many hand hygiene products contain irritants and allergens. The lipid-stripping effects of soaps, detergents, and hand sanitizers in conjunction with increased frequency of handwashing can trigger ICD. The most common allergens implicated in hand ACD include MI, nickel, formaldehyde, quaternium-15, and fragrances. Patch testing is important for diagnosis, and supplemental series should be considered. Management includes avoidance of irritants and allergens; liberal use of moisturizers and barrier creams; and prescription topical therapy, phototherapy, or systemic therapy when indicated.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, et al. The epidemiology of hand eczema in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:75-87.

- Meding B, Swanbeck G. Epidemiology of different types of hand eczema in an industrial city. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:227-233.

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Atwater AR, et al. Hand dermatitis in adults referred for patch testing: analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2000–2016 [published online November 28, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.054

- Sasseville D. Occupational contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:59.

- Lampel HP, Powell HB. Occupational and hand dermatitis: a practical approach. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:60-71.

- Lampel HP, Patel N, Boyse K, et al. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in inpatient nurses at a United States hospital. Dermatitis. 2007;18:140-142.

- Lan J, Song Z, Miao X, et al. Skin damage among health care workers managing coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1215-1216.

- Wei Tan S, Chiat Oh C. Contact dermatitis from hand hygiene practices in the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020;49:674-676.

- Beiu C, Mihai M, Popa L, et al. Frequent hand washing for COVID-19 prevention can cause hand dermatitis: management tips. Cureus. 2020;12:E7506.

- Wolfe MK, Wells E, Mitro B, et al. Seeking clearer recommendations for hand hygiene in communities facing ebola: a randomized trial investigating the impact of six handwashing methods on skin irritation and dermatitis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167378.

- Rundle CW, Presley CL, Militello M, et al. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1730-1737.

- Cartner T, Brand N, Tian K, et al. Effect of different alcohols on stratum corneum kallikrein 5 and phospholipase A(2) together with epidermal keratinocytes and skin irritation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39:188-196.

- Clemmensen A, Andersen F, Petersen TK, et al. The irritant potential of n-propanol (nonanoic acid vehicle) in cumulative skin irritation: a validation study of two different human in vivo test models. Ski Res Technol. 2008;14:277-286.

- McMullen E, Gawkrodger DJ. Physical friction is under-recognized as an irritant that can cause or contribute to contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:154-156.

- Macheleidt O, Kaiser HW, Sandhoff K. Deficiency of epidermal protein-bound omega-hydroxyceramides in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:166-173.

- Visser MJ, Landeck L, Campbell LE, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis and loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene on the development of occupational irritant contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:326-332.

- Coenraads PJ, Diepgen TL. Risk for hand eczema in employees with past or present atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1998;71:7-13.

- Oosterhaven JAF, Uter W, Aberer W, et al. European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (ESSCA): contact allergies in relation to body sites in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:263-272.

- Goodier MC, Ronkainen SD, Hylwa SA. Rubber accelerators in medical examination and surgical gloves. Dermatitis. 2018;29:66-76.

- Voller LM, Schlarbaum JP, Hylwa SA. Allergenic ingredients in health care hand sanitizers in the United States [published online February 21, 2020]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000567

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Atwater AR. Allergens in medical hand skin cleansers. Dermatitis. 2019;30:336-341.

- Scheman A, Severson D. American Contact Dermatitis Society Contact Allergy Management Program: an epidemiologic tool to quantify ingredient usage. Dermatitis. 2016;27:11-13.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Kadivar S, Belsito DV. Occupational dermatitis in health care workers evaluated for suspected allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2015;26:177-183.

- Prodi A, Rui F, Fortina AB, et al. Healthcare workers and skin sensitization: north-eastern Italian database. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2016;66:72-74.

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Dekoven JG, et al. Occupationally related nickel reactions: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data 1998-2016. Dermatitis. 2019;30:306-313.

- Thyssen JP, Milting K, Bregnhøj A, et al. Nickel allergy in patch-tested female hairdressers and assessment of nickel release from hairdressers’ scissors and crochet hooks. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:281-286.

- Symanzik C, John SM, Strunk M. Nickel release from metal tools in the German hairdressing trade—a current analysis. 2019;80:382-385.

- Rystedt I, Fischer T. Relationship between nickel and cobalt sensitization in hard metal workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:195-200.

- Kettelarij JAB, Lidén C, Axén E, et al. Cobalt, nickel and chromium release from dental tools and alloys. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:3-10.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Jellesen MS, et al. Consumer leather exposure: an unrecognized cause of cobalt sensitization. 2013;69:276-279.

- Hamnerius N, Svedman C, Bergendorff O, et al. Hand eczema and occupational contact allergies in healthcare workers with a focus on rubber additives. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:149-156.

- Warshaw EM, Gupta R, Dekoven JG, et al. Patch testing to diphenylguanidine by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (2013-2016). Dermatitis. 2020;31:350-358.

- Perry AD, Trafeli JP. Hand dermatitis: review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:325-330.

- Abtahi-Naeini B. Frequent handwashing amidst the COVID-19 outbreak: prevention of hand irritant contact dermatitis and other considerations. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3:E163.

- Schliemann S, Kelterer D, Bauer A, et al. Tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of occupationally induced chronic hand dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:299-306. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01314.x

- Lynde CW, Bergman J, Fiorillo L, et al. Use of topical crisaborole for treating dermatitis in a variety of dermatology settings. Skin Therapy Lett. Published June 1, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.skintherapyletter.com/dermatology/topical-crisaborole-dermatitis-treatment/

- Rosén K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. Chronic eczematous dermatitis of the hands: a comparison of PUVA and UVB treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67:48-54.

- Kwon GP, Tan CZ, Chen JK. Hand dermatitis: utilizing subtype classification to direct intervention. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2016;3:322-332.

- Warshaw E, Lee G, Storrs FJ. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, therapeutic options, and long-term outcomes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:119-137.

- Song M, Lee H-J, Lee W-K, et al. Acitretin as a therapeutic option for chronic hand eczema. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:385-387.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, et al. The epidemiology of hand eczema in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:75-87.

- Meding B, Swanbeck G. Epidemiology of different types of hand eczema in an industrial city. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:227-233.

- Silverberg JI, Warshaw EM, Atwater AR, et al. Hand dermatitis in adults referred for patch testing: analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2000–2016 [published online November 28, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.054

- Sasseville D. Occupational contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:59.

- Lampel HP, Powell HB. Occupational and hand dermatitis: a practical approach. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:60-71.

- Lampel HP, Patel N, Boyse K, et al. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in inpatient nurses at a United States hospital. Dermatitis. 2007;18:140-142.

- Lan J, Song Z, Miao X, et al. Skin damage among health care workers managing coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1215-1216.

- Wei Tan S, Chiat Oh C. Contact dermatitis from hand hygiene practices in the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020;49:674-676.

- Beiu C, Mihai M, Popa L, et al. Frequent hand washing for COVID-19 prevention can cause hand dermatitis: management tips. Cureus. 2020;12:E7506.

- Wolfe MK, Wells E, Mitro B, et al. Seeking clearer recommendations for hand hygiene in communities facing ebola: a randomized trial investigating the impact of six handwashing methods on skin irritation and dermatitis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167378.

- Rundle CW, Presley CL, Militello M, et al. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1730-1737.

- Cartner T, Brand N, Tian K, et al. Effect of different alcohols on stratum corneum kallikrein 5 and phospholipase A(2) together with epidermal keratinocytes and skin irritation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39:188-196.

- Clemmensen A, Andersen F, Petersen TK, et al. The irritant potential of n-propanol (nonanoic acid vehicle) in cumulative skin irritation: a validation study of two different human in vivo test models. Ski Res Technol. 2008;14:277-286.

- McMullen E, Gawkrodger DJ. Physical friction is under-recognized as an irritant that can cause or contribute to contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:154-156.

- Macheleidt O, Kaiser HW, Sandhoff K. Deficiency of epidermal protein-bound omega-hydroxyceramides in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:166-173.

- Visser MJ, Landeck L, Campbell LE, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis and loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene on the development of occupational irritant contact dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:326-332.

- Coenraads PJ, Diepgen TL. Risk for hand eczema in employees with past or present atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1998;71:7-13.

- Oosterhaven JAF, Uter W, Aberer W, et al. European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (ESSCA): contact allergies in relation to body sites in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:263-272.

- Goodier MC, Ronkainen SD, Hylwa SA. Rubber accelerators in medical examination and surgical gloves. Dermatitis. 2018;29:66-76.

- Voller LM, Schlarbaum JP, Hylwa SA. Allergenic ingredients in health care hand sanitizers in the United States [published online February 21, 2020]. Dermatitis. doi:10.1097/der.0000000000000567

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Atwater AR. Allergens in medical hand skin cleansers. Dermatitis. 2019;30:336-341.

- Scheman A, Severson D. American Contact Dermatitis Society Contact Allergy Management Program: an epidemiologic tool to quantify ingredient usage. Dermatitis. 2016;27:11-13.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Kadivar S, Belsito DV. Occupational dermatitis in health care workers evaluated for suspected allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2015;26:177-183.

- Prodi A, Rui F, Fortina AB, et al. Healthcare workers and skin sensitization: north-eastern Italian database. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2016;66:72-74.

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Dekoven JG, et al. Occupationally related nickel reactions: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group data 1998-2016. Dermatitis. 2019;30:306-313.

- Thyssen JP, Milting K, Bregnhøj A, et al. Nickel allergy in patch-tested female hairdressers and assessment of nickel release from hairdressers’ scissors and crochet hooks. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:281-286.

- Symanzik C, John SM, Strunk M. Nickel release from metal tools in the German hairdressing trade—a current analysis. 2019;80:382-385.

- Rystedt I, Fischer T. Relationship between nickel and cobalt sensitization in hard metal workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:195-200.

- Kettelarij JAB, Lidén C, Axén E, et al. Cobalt, nickel and chromium release from dental tools and alloys. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:3-10.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Jellesen MS, et al. Consumer leather exposure: an unrecognized cause of cobalt sensitization. 2013;69:276-279.

- Hamnerius N, Svedman C, Bergendorff O, et al. Hand eczema and occupational contact allergies in healthcare workers with a focus on rubber additives. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:149-156.

- Warshaw EM, Gupta R, Dekoven JG, et al. Patch testing to diphenylguanidine by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (2013-2016). Dermatitis. 2020;31:350-358.

- Perry AD, Trafeli JP. Hand dermatitis: review of etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:325-330.

- Abtahi-Naeini B. Frequent handwashing amidst the COVID-19 outbreak: prevention of hand irritant contact dermatitis and other considerations. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3:E163.

- Schliemann S, Kelterer D, Bauer A, et al. Tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of occupationally induced chronic hand dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:299-306. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01314.x

- Lynde CW, Bergman J, Fiorillo L, et al. Use of topical crisaborole for treating dermatitis in a variety of dermatology settings. Skin Therapy Lett. Published June 1, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.skintherapyletter.com/dermatology/topical-crisaborole-dermatitis-treatment/

- Rosén K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. Chronic eczematous dermatitis of the hands: a comparison of PUVA and UVB treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 1987;67:48-54.

- Kwon GP, Tan CZ, Chen JK. Hand dermatitis: utilizing subtype classification to direct intervention. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2016;3:322-332.

- Warshaw E, Lee G, Storrs FJ. Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, therapeutic options, and long-term outcomes. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:119-137.

- Song M, Lee H-J, Lee W-K, et al. Acitretin as a therapeutic option for chronic hand eczema. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:385-387.

Practice Points

- For the hands, irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is more common than allergic contact dermatitis in both occupational and nonoccupational settings. Because of overlapping clinical features, it can be difficult to differentiate between these conditions.

- Use of hand hygiene products, frequent handwashing, wet work, mechanical trauma, and occlusion can contribute to ICD of the hands.

- Common hand contact allergens include preservatives, metals, fragrances, and rubber accelerators.

- Patch testing often is necessary for diagnosis of hand dermatitis, and both screening and supplemental allergen series may be required.

Exercise-Induced Vasculitis in a Patient With Negative Ultrasound Venous Reflux Study: A Mimic of Stasis Dermatitis

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

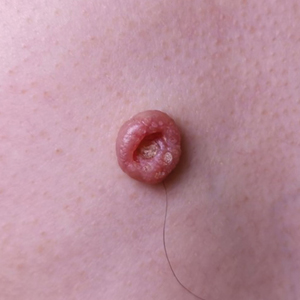

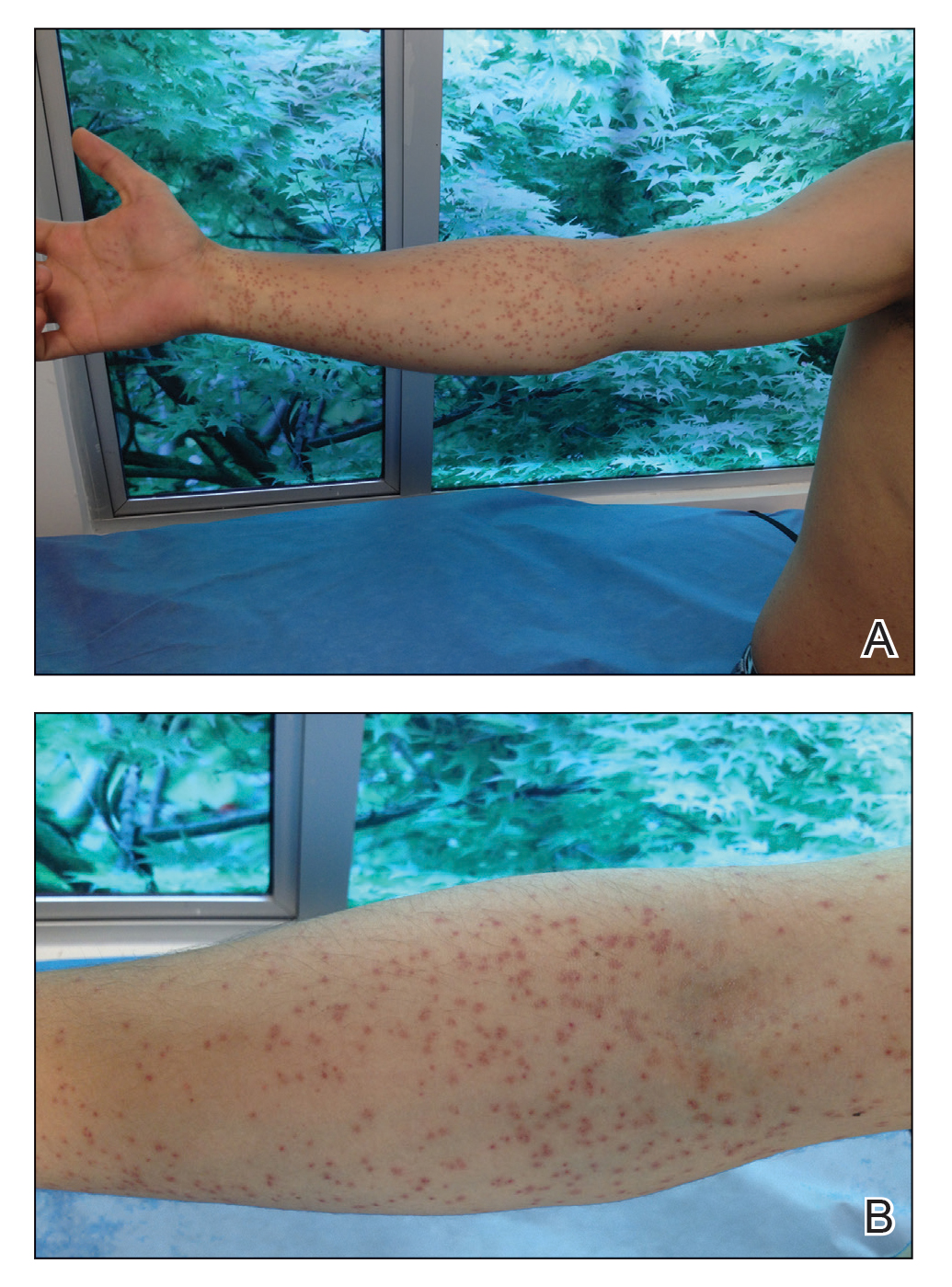

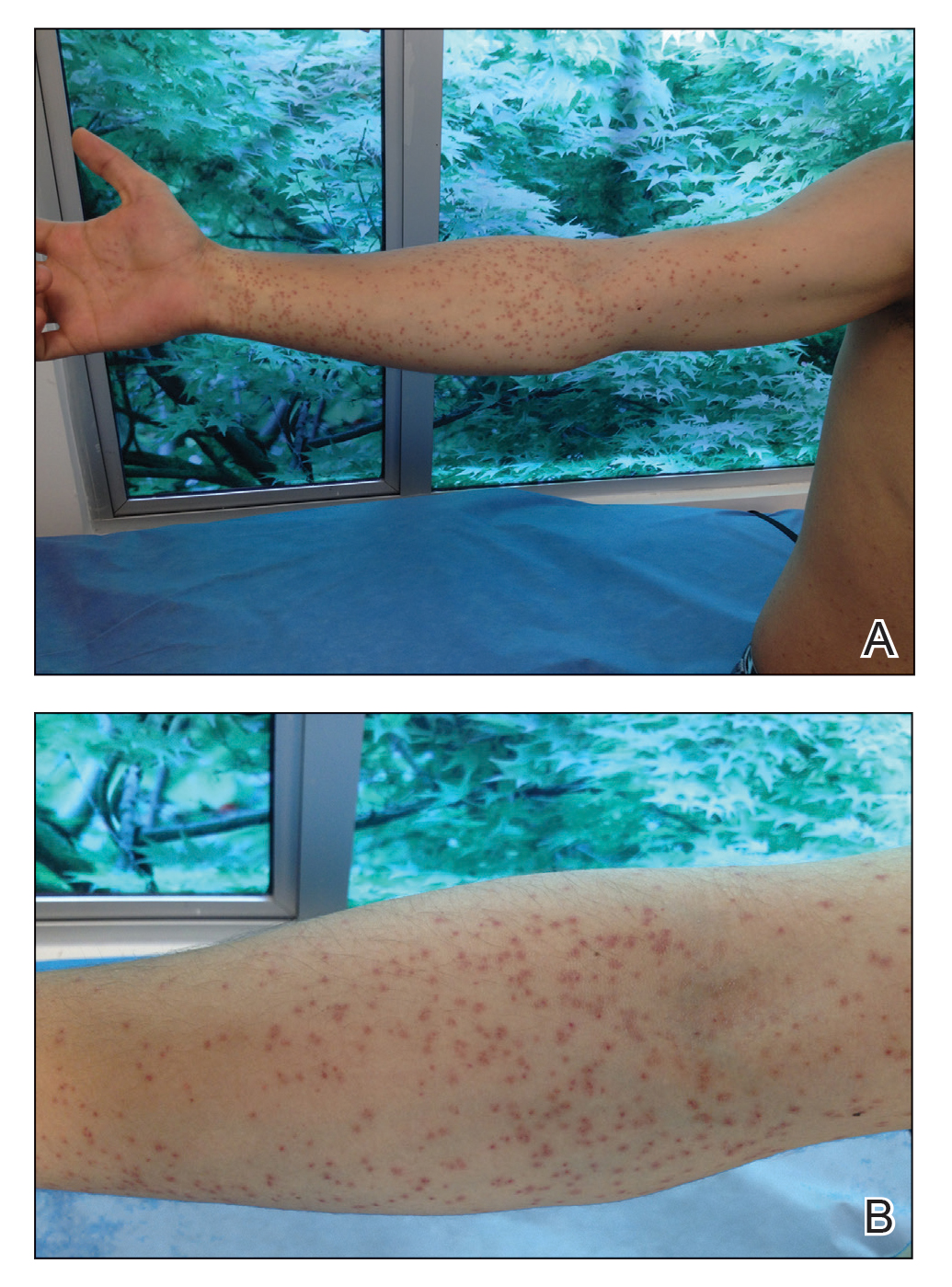

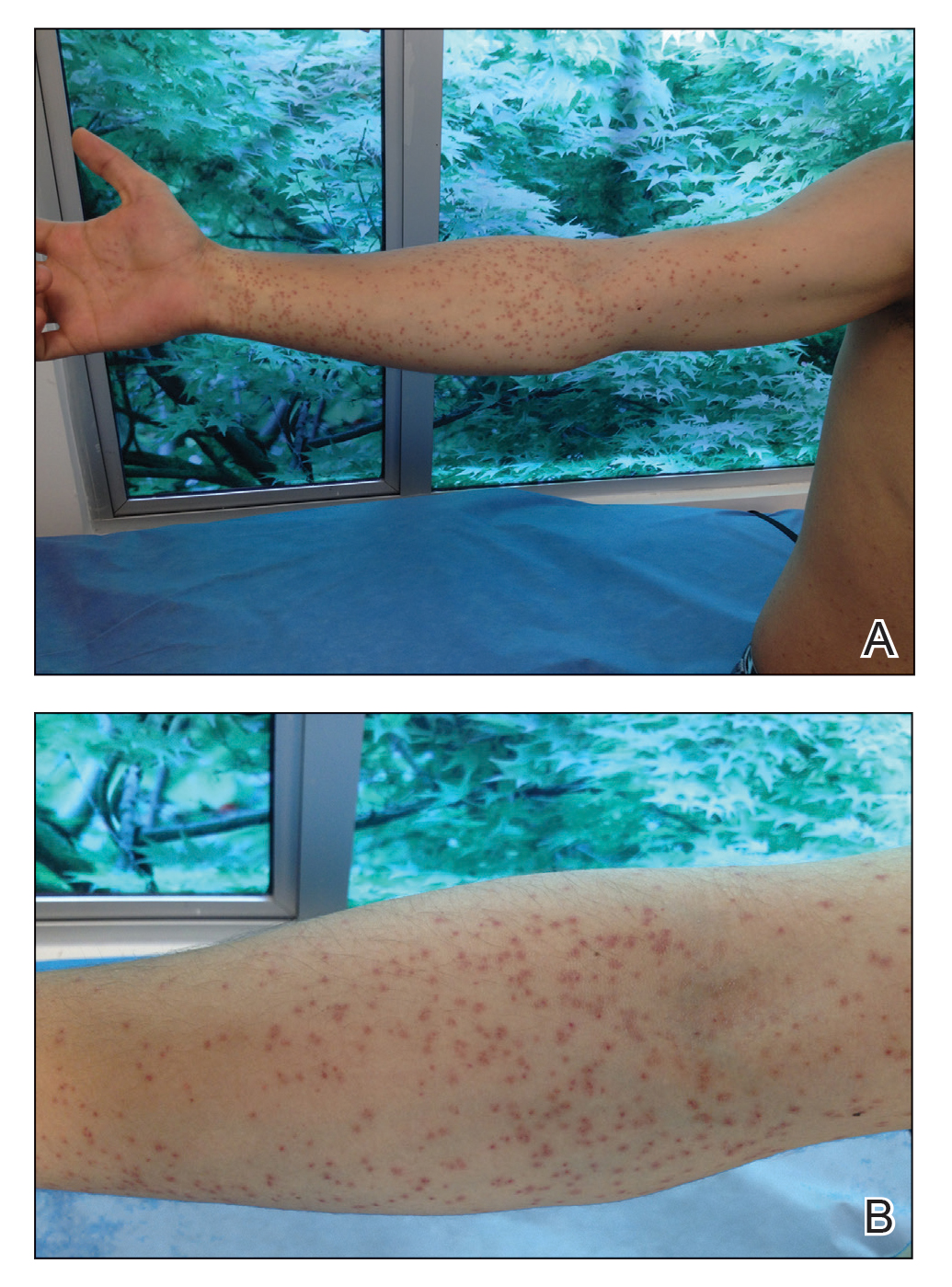

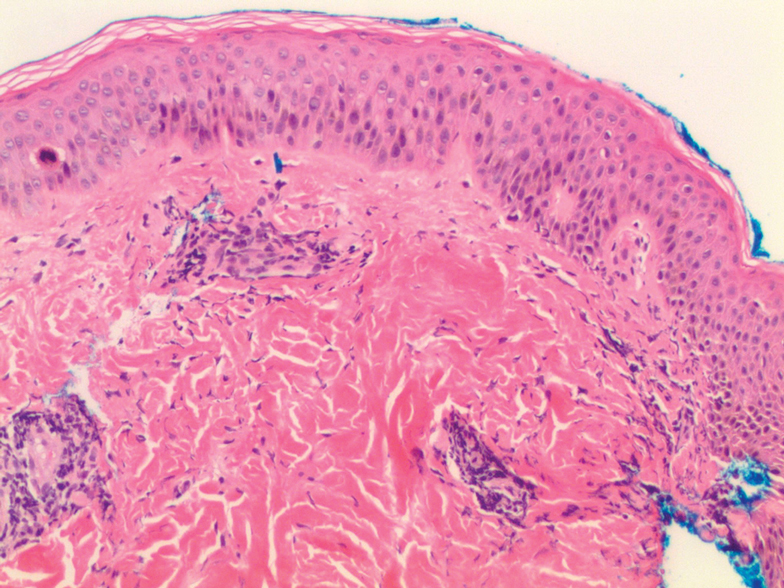

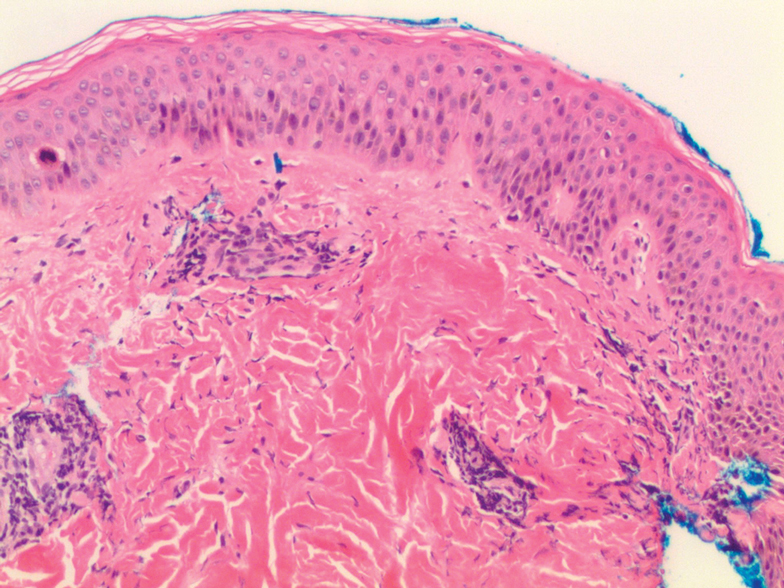

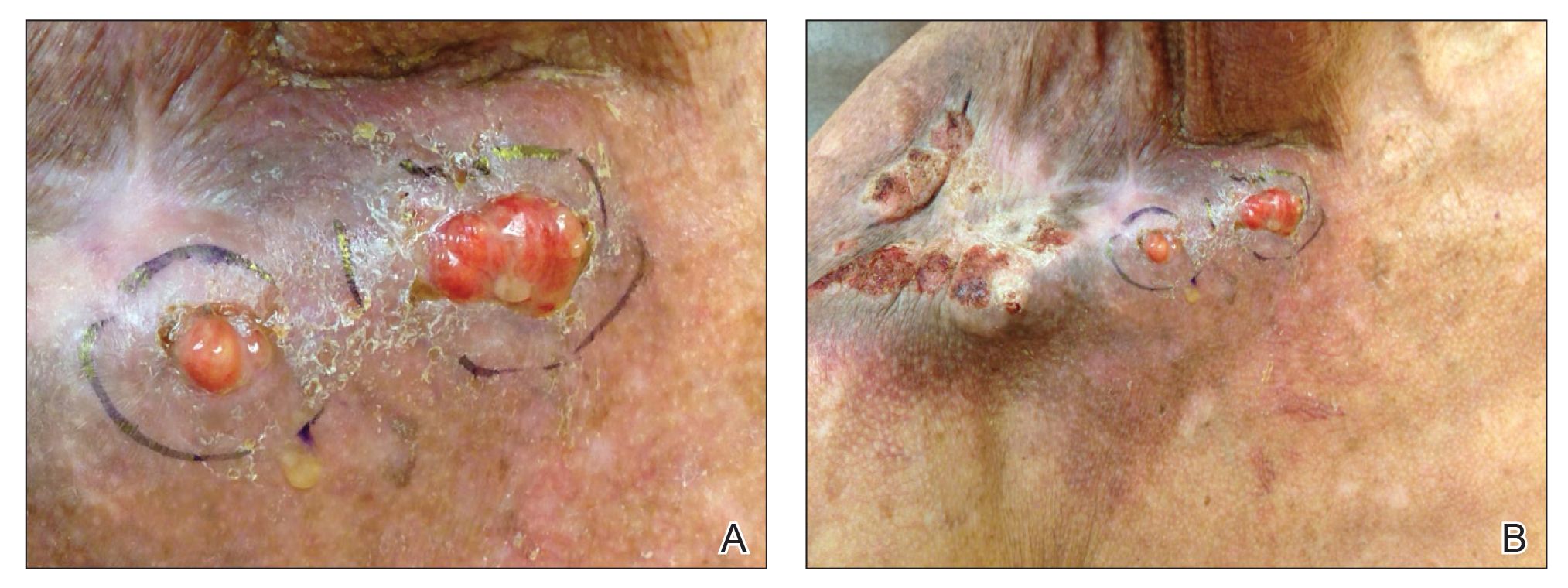

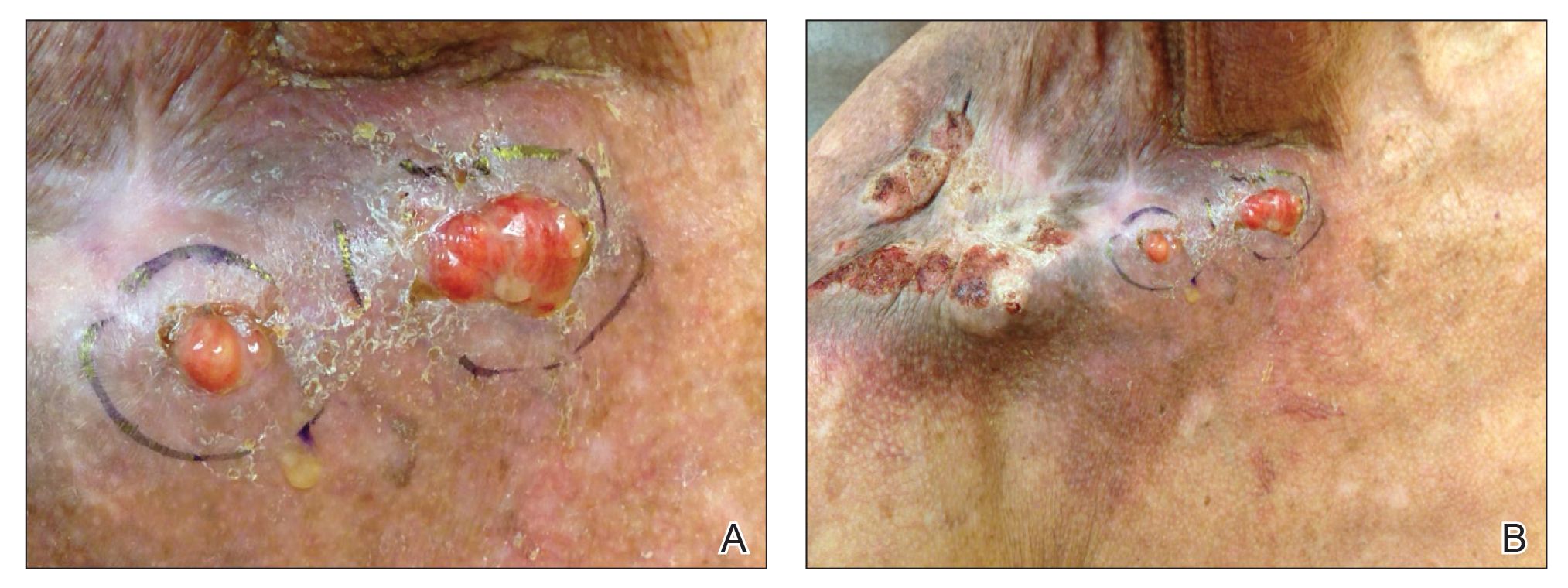

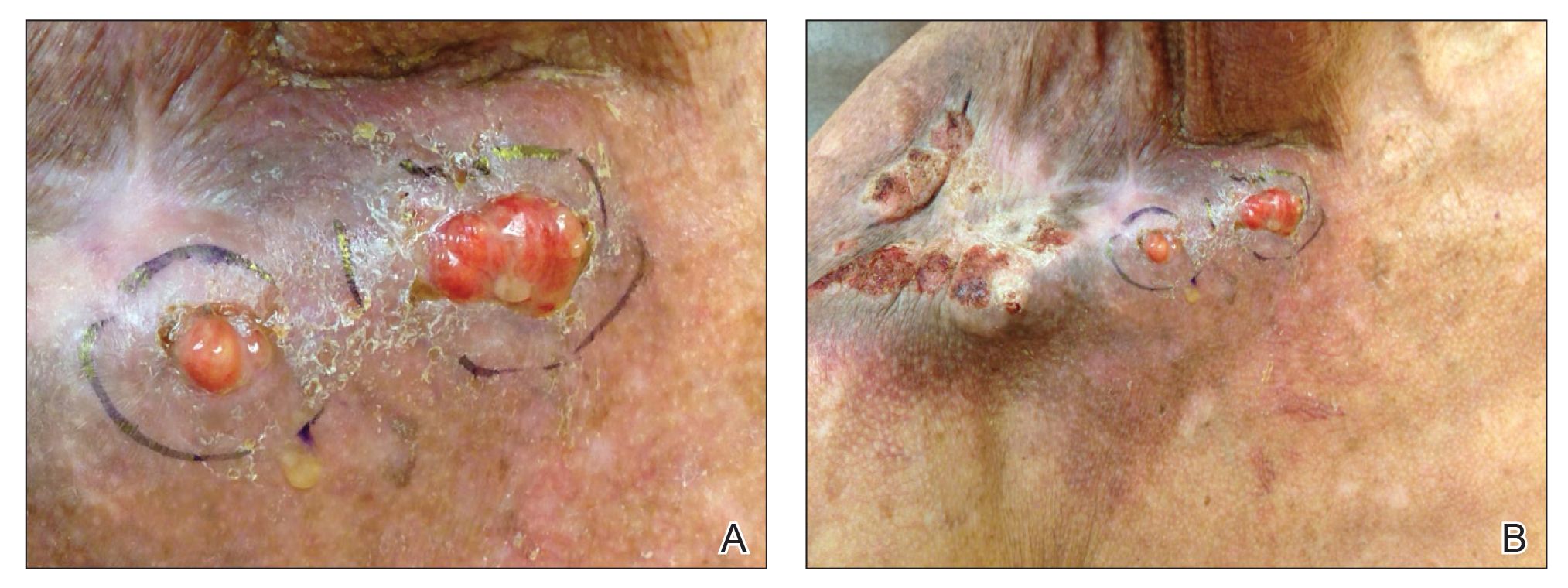

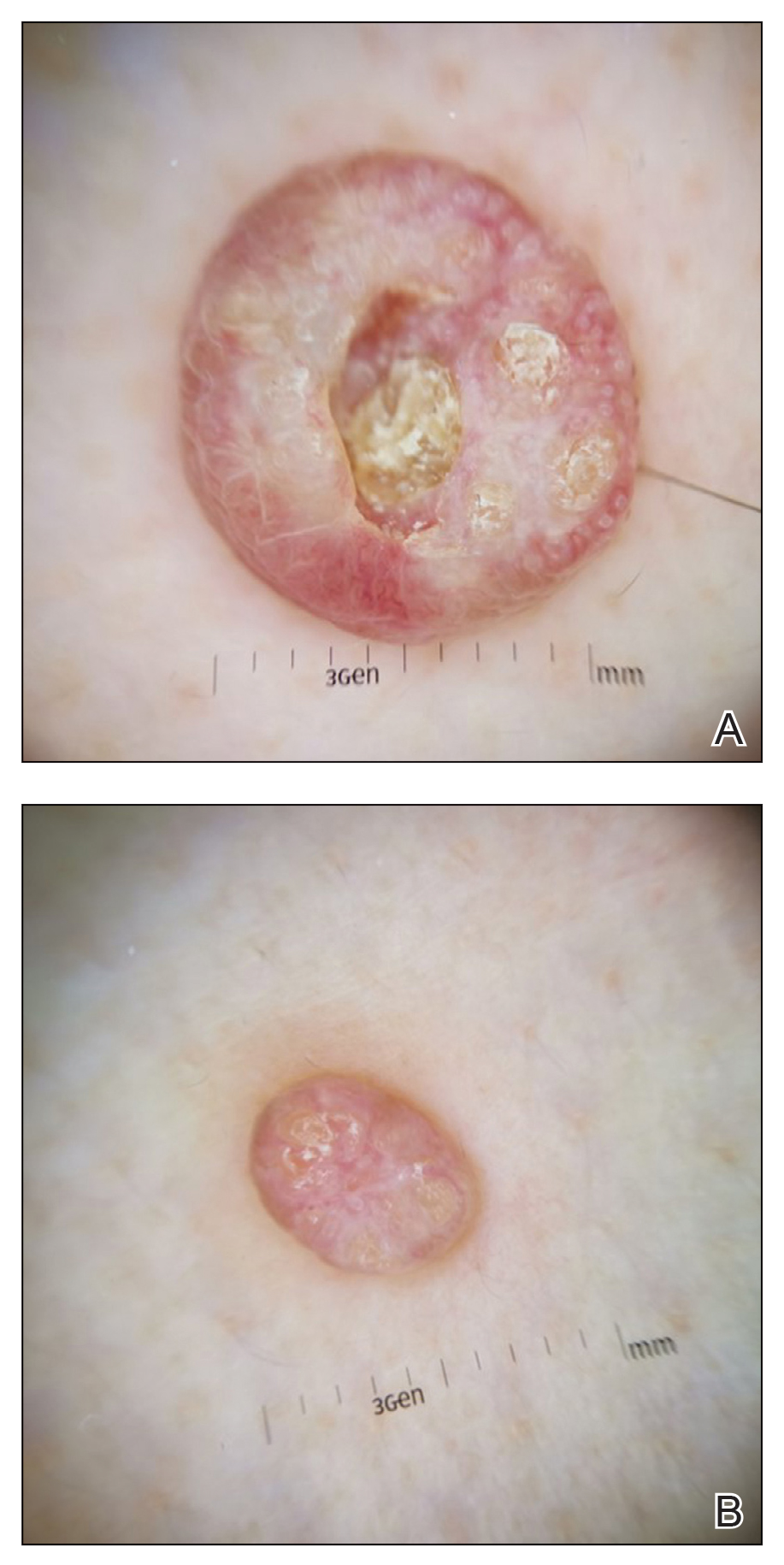

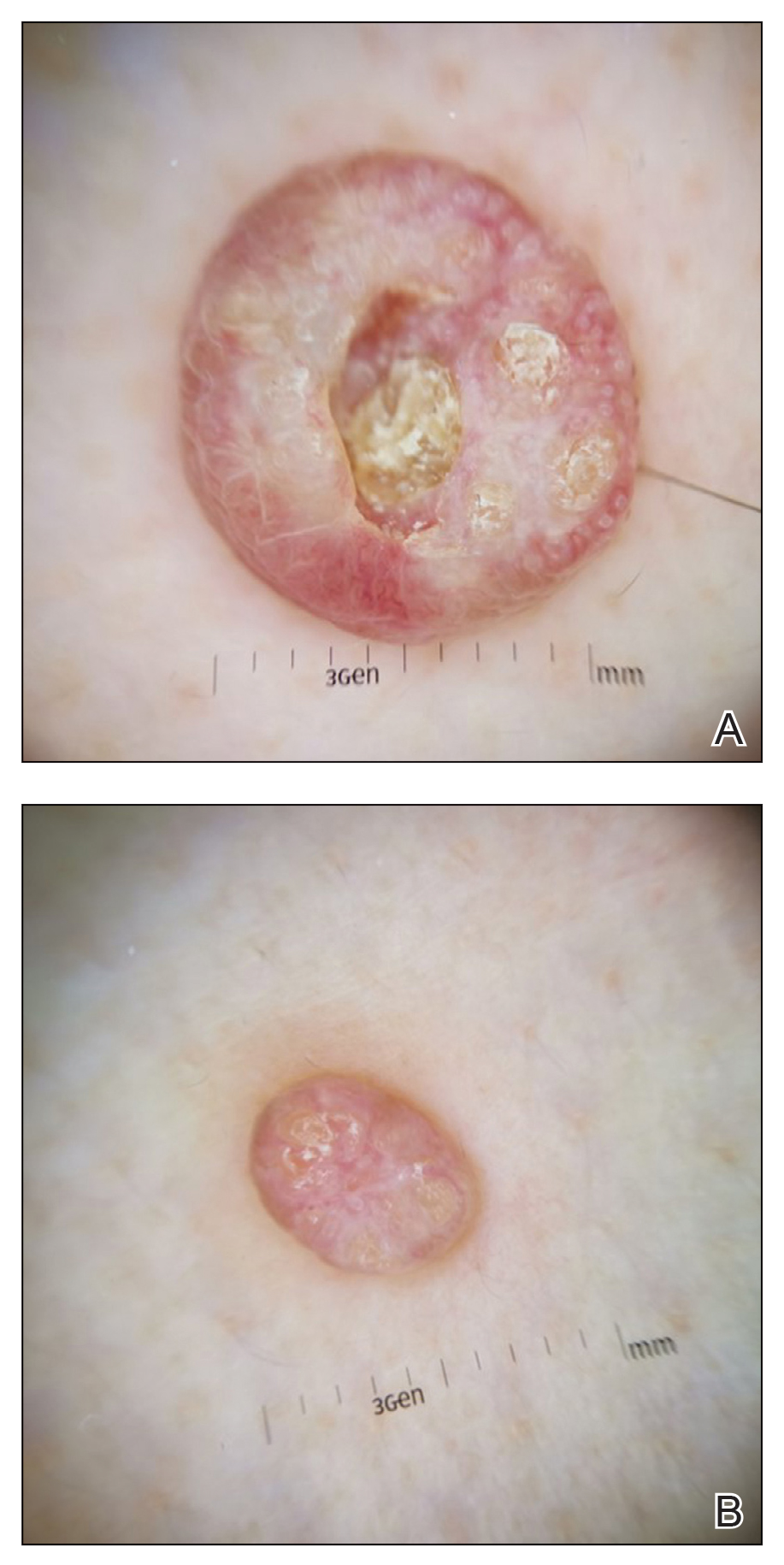

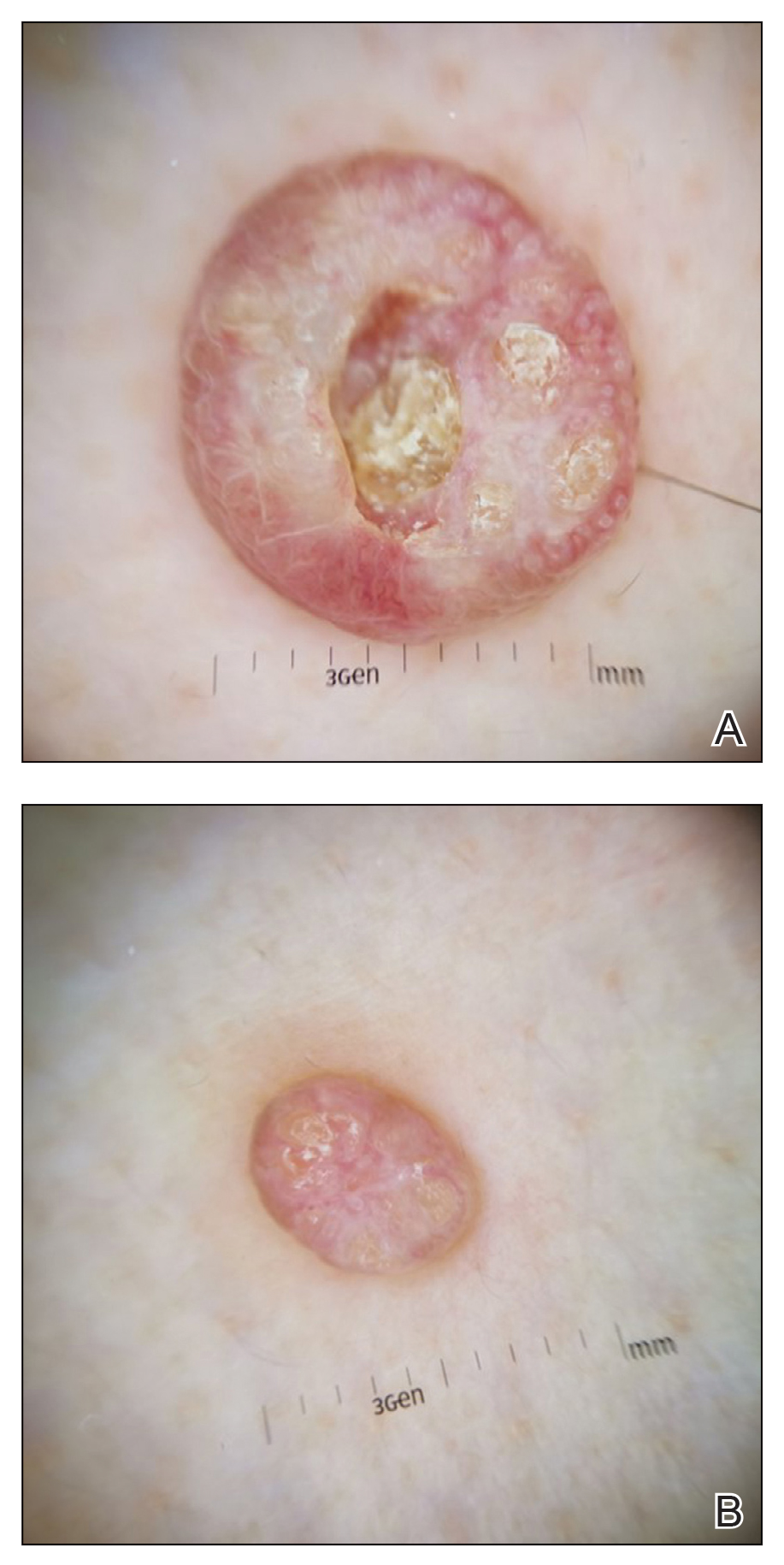

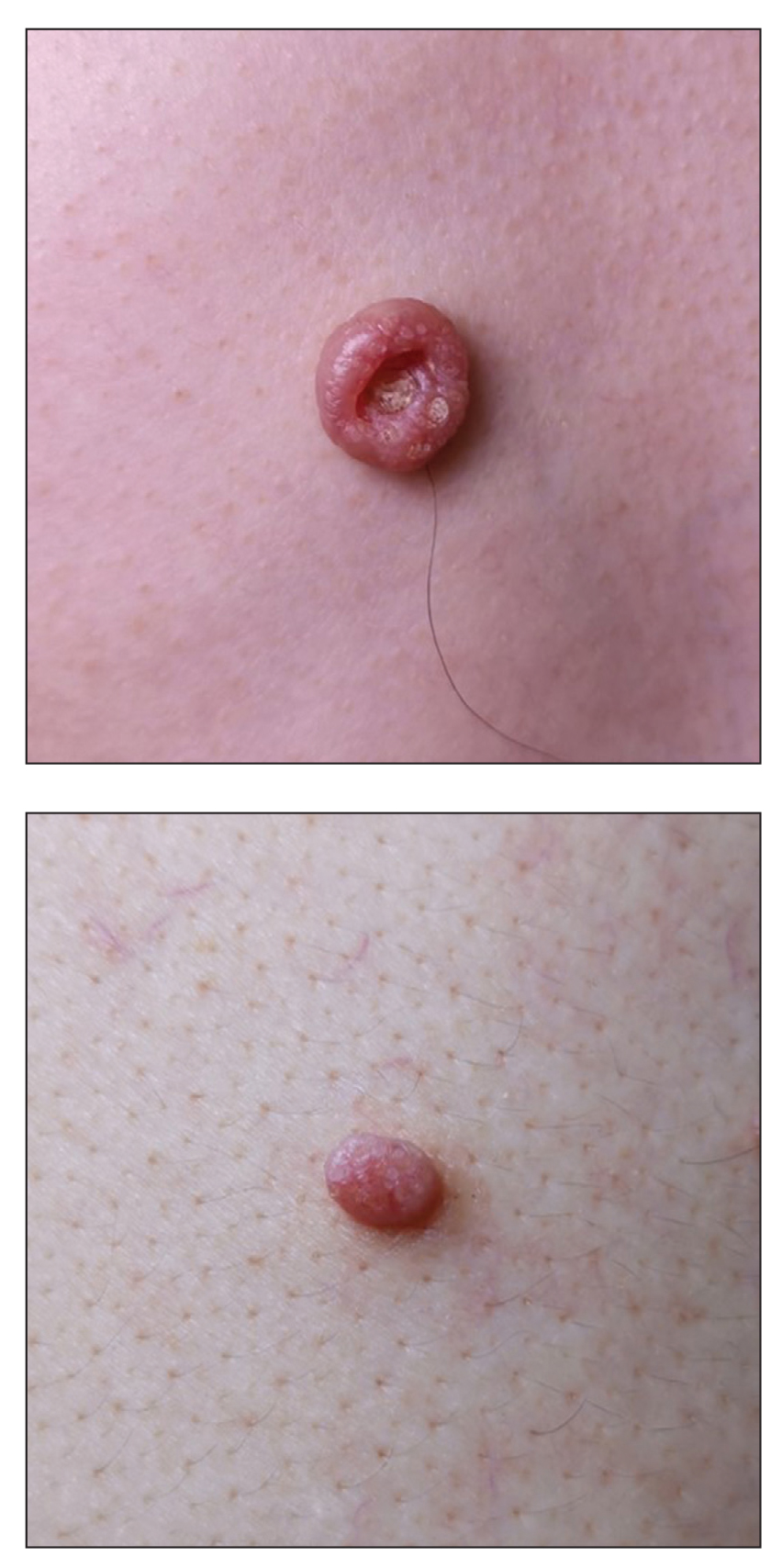

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.

The pathophysiology of EIV remains unknown, but the concept of exercise-altered microcirculation has been proposed. Heat generated from exercise is normally dissipated by thermoregulatory mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilation and sweat.1,6 When exercise is extended, done concomitantly in the heat, or performed in legs with preexisting edema or substantial adipose tissue that limit heat attenuation, the thermoregulatory capacity is overloaded and heat-induced muscle fiber breakdown occurs.1,7 Atrophy impairs the skeletal muscle’s ability to pump the increased venous return demanded by exercise to the heart, leading to backflow of venous return and eventual venous stasis.1 Reduction of venous return together with cutaneous vasodilation is thought to induce erythrocyte extravasation.

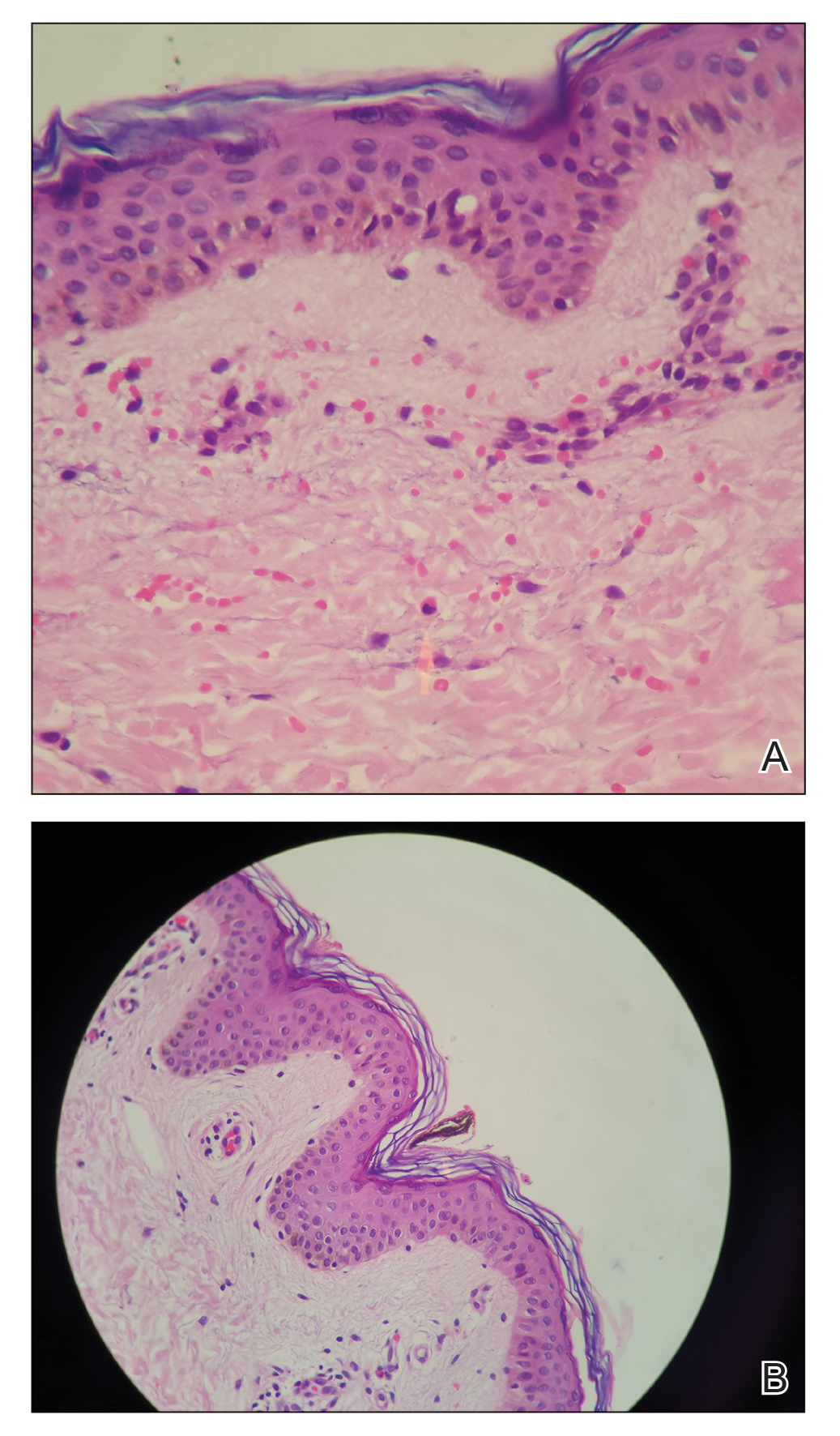

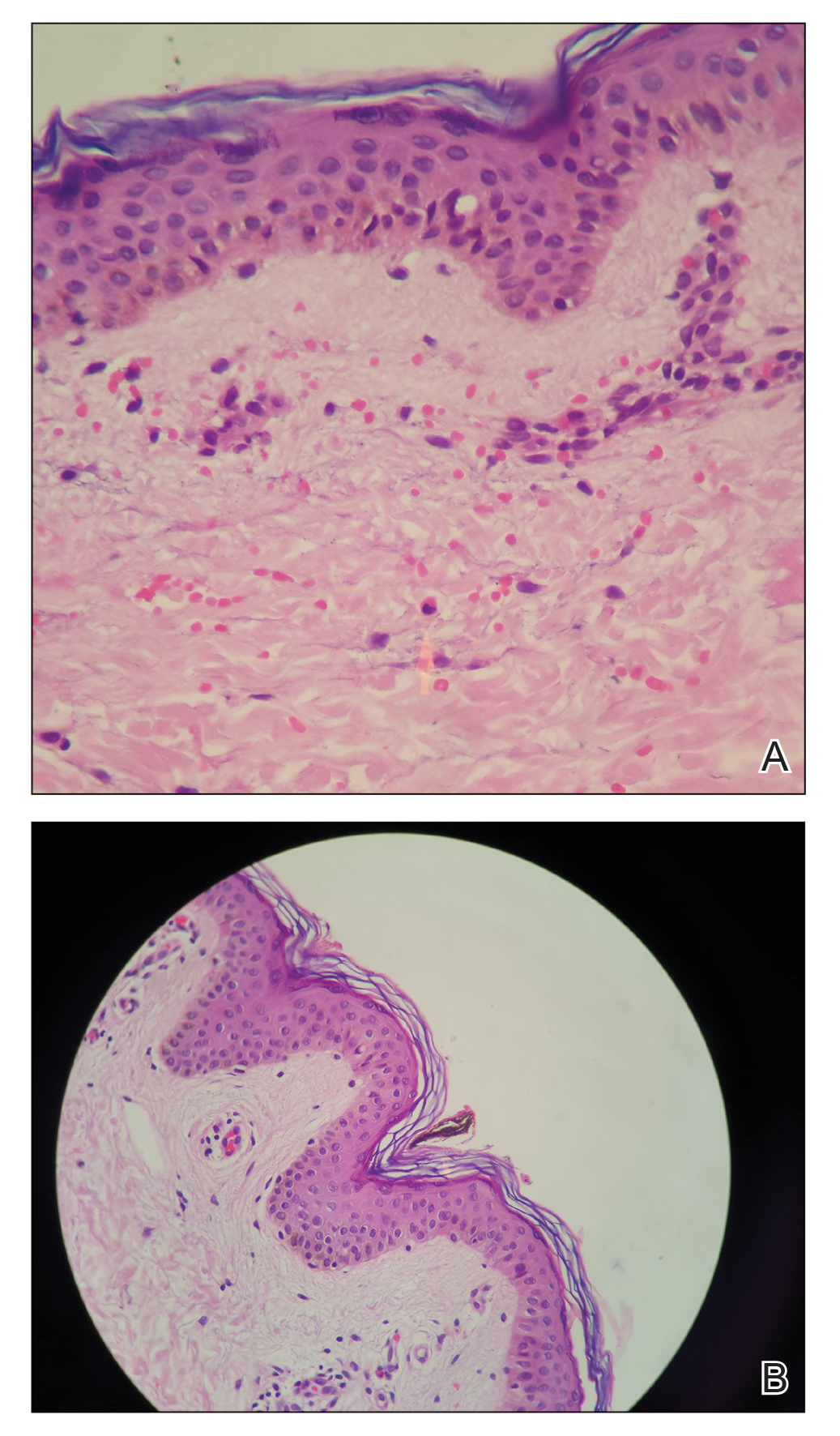

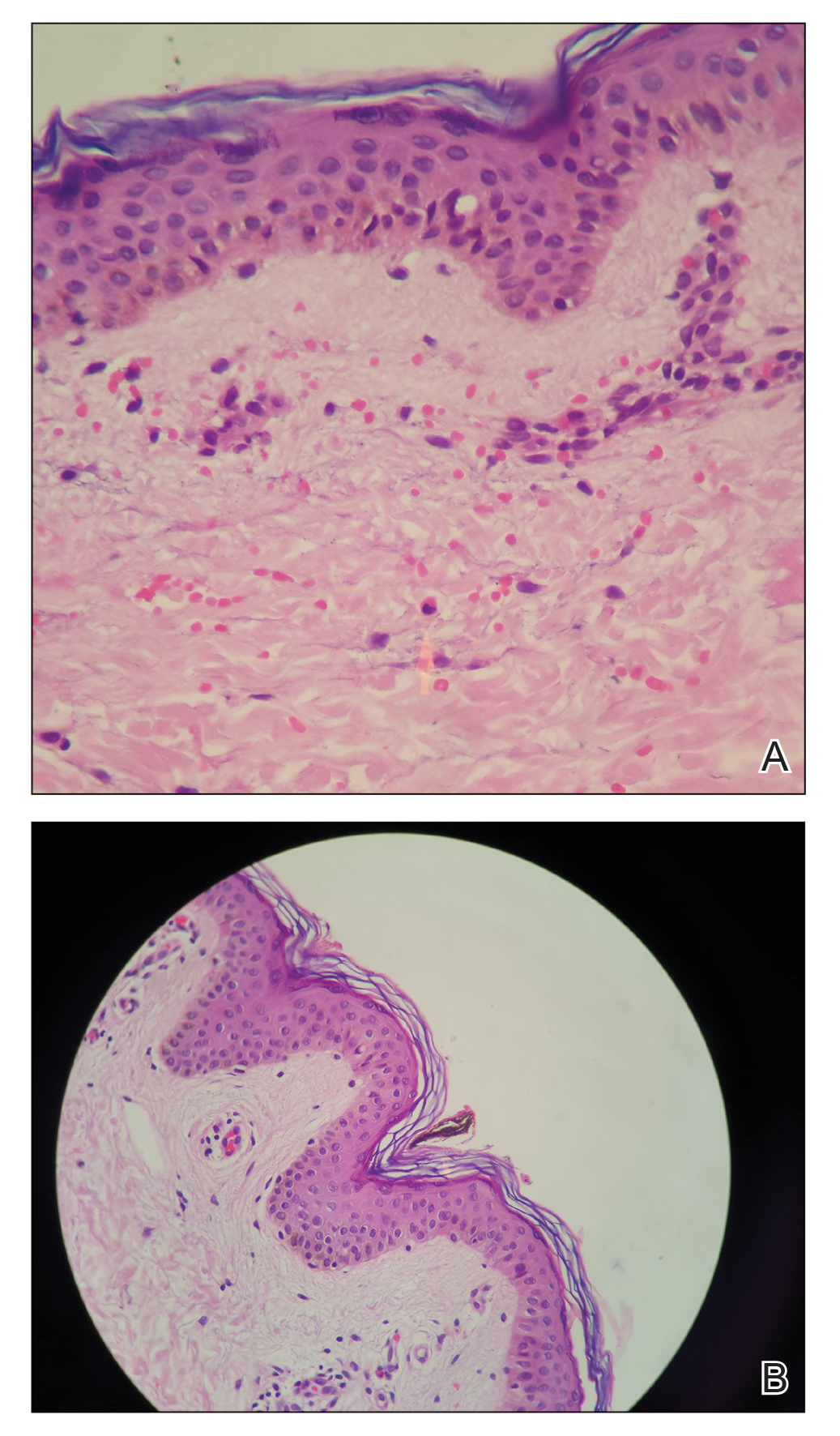

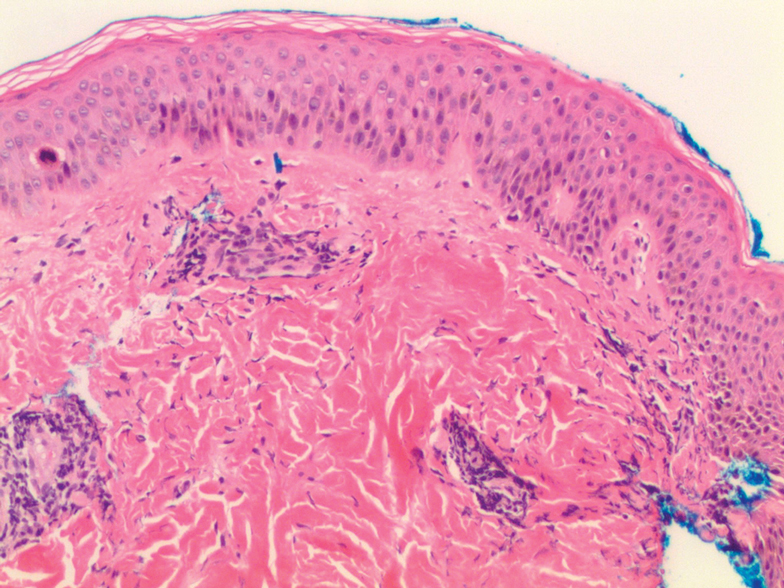

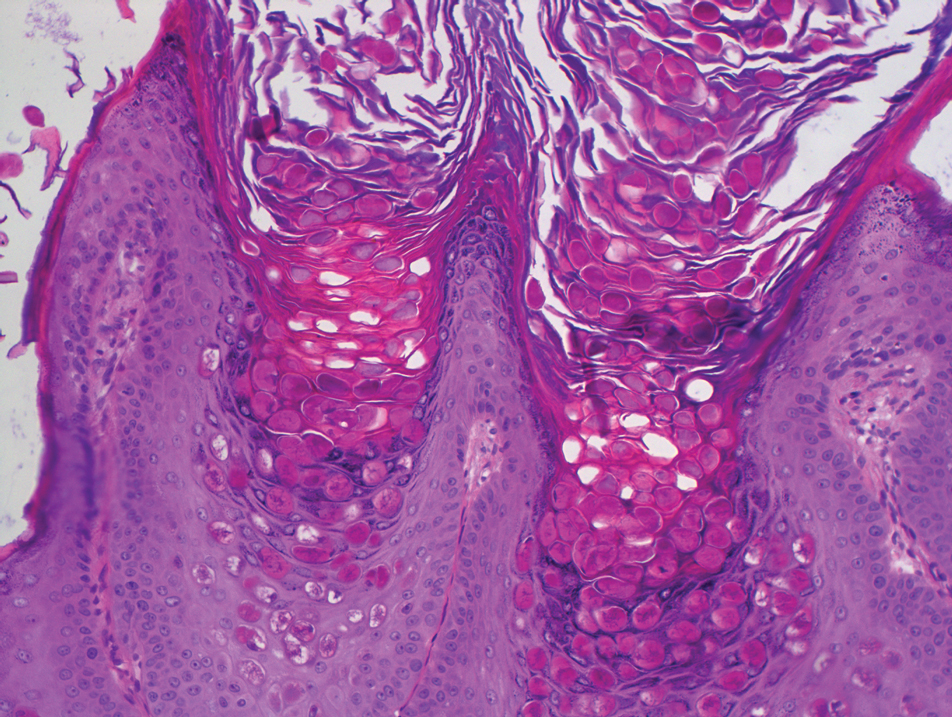

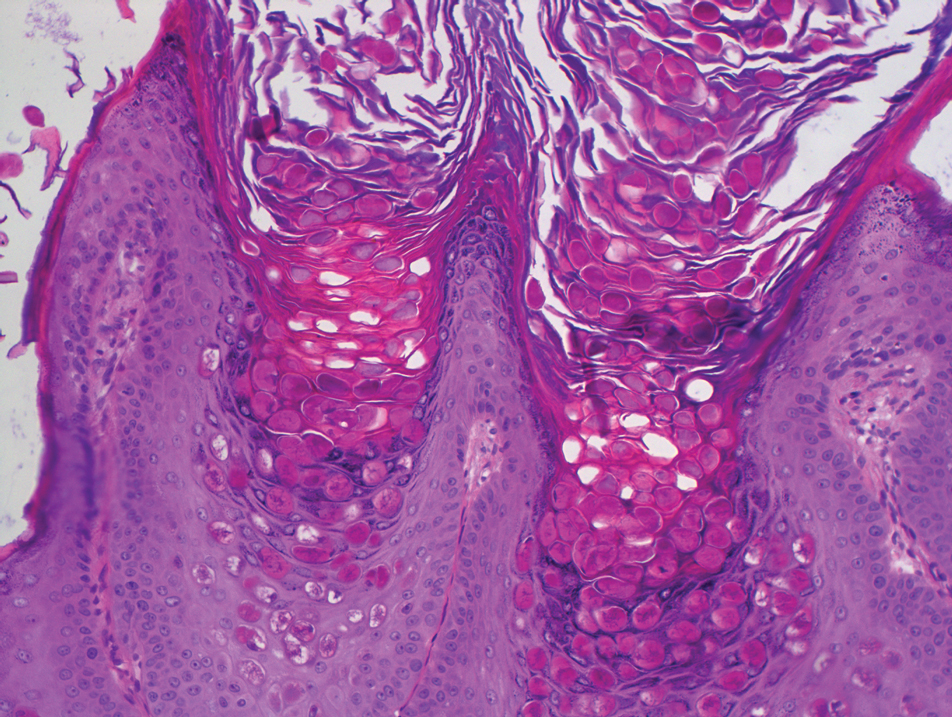

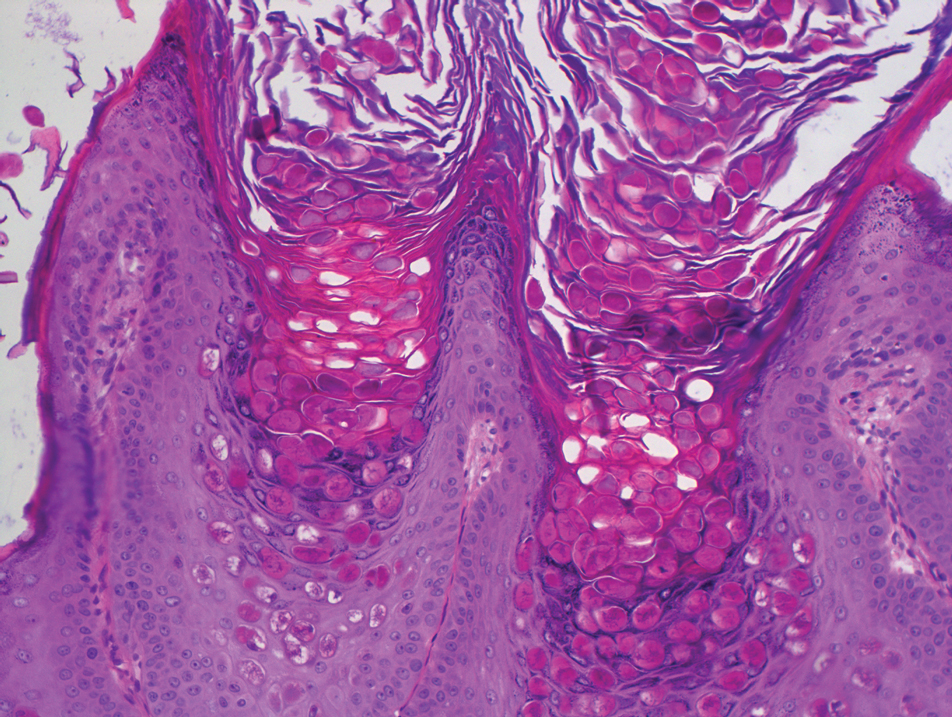

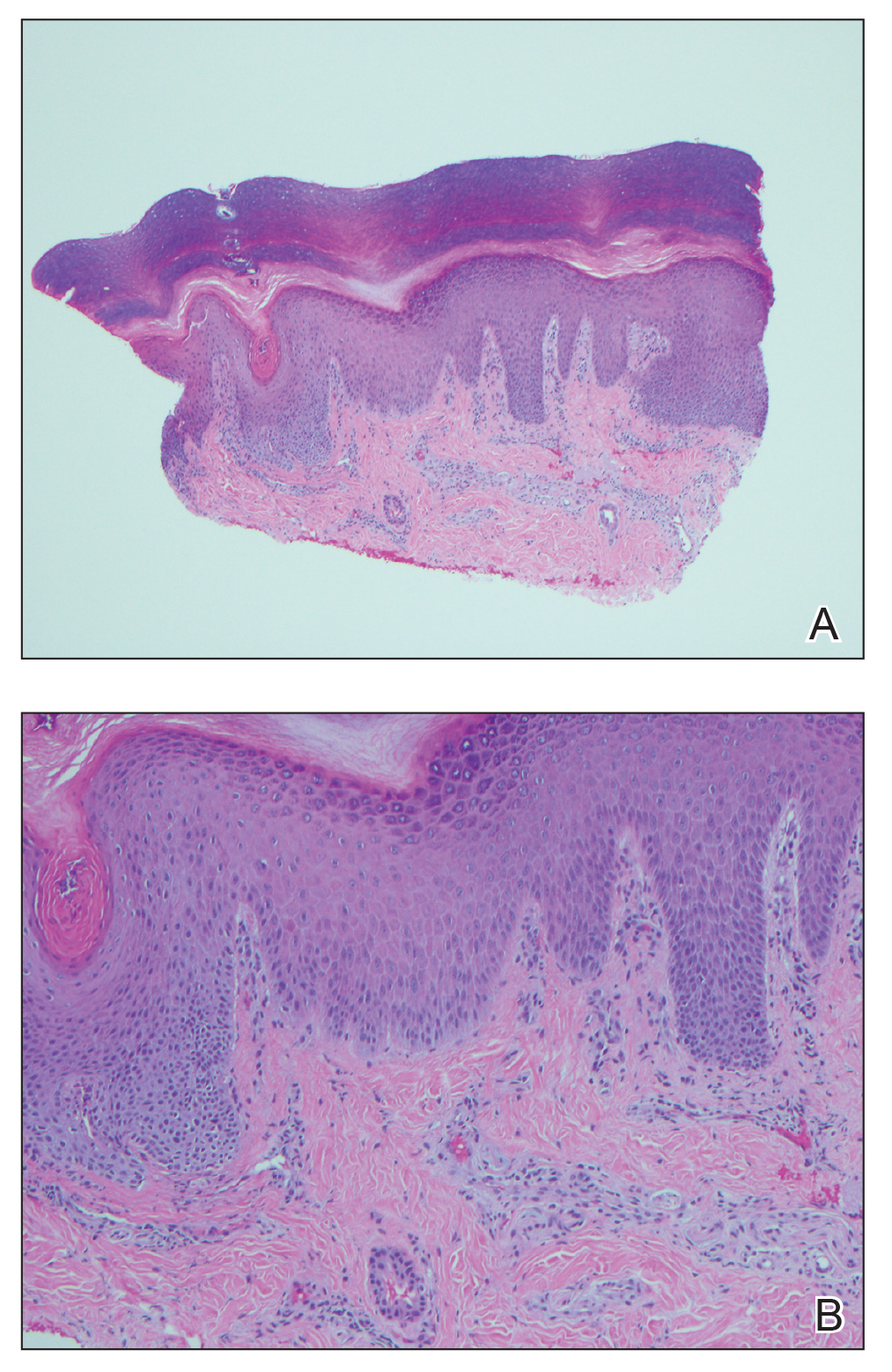

Histologic examination demonstrates features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates.2 Erythrocyte extravasation, IgM deposits, and identification of C3 also have been reported.8,9 The spontaneous resolution of EIV has led to treatment efforts being focused on preventative measures. Several cases have reported some degree of success in preventing EIV with compression therapy, venoactive drugs, systemic steroids, and application of topical steroids before exercise.3

The clinical morphology and lower leg location of EIV leads to a common misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of EIV, and ultrasound venous reflux study may be required in some cases. Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced vasculitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:423-427.

- Kelly RI, Opie J, Nixon R. Golfer’s vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:11-14.

- Ramelet AA. Exercise-induced purpura. Dermatology. 2004;208:293-296.

- Cushman D, Rydberg L. A general rehabilitation inpatient with exercise-induced vasculitis. PM R. 2013;5:900-902.

- Veraart JC, Prins M, Hulsmans RF, et al. Influence of endurance exercise on the venous refilling time of the leg. Phlebology. 1994;23:120-123.

- Noakes T. Fluid replacement during marathon running. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:309-318.

- Armstrong RB. Muscle damage and endurance events. Sports Med. 1986;3:370-381.

- Prins M, Veraart JC, Vermeulen AH, et al. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis induced by prolonged exercise. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:915-918.

- Sagdeo A, Gormley RH, Wanat KA, et al. Purpuric eruption on the feet of a healthy young woman. “flip-flop vasculitis” (exercise-induced vasculitis). JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:751-756.

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.

The pathophysiology of EIV remains unknown, but the concept of exercise-altered microcirculation has been proposed. Heat generated from exercise is normally dissipated by thermoregulatory mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilation and sweat.1,6 When exercise is extended, done concomitantly in the heat, or performed in legs with preexisting edema or substantial adipose tissue that limit heat attenuation, the thermoregulatory capacity is overloaded and heat-induced muscle fiber breakdown occurs.1,7 Atrophy impairs the skeletal muscle’s ability to pump the increased venous return demanded by exercise to the heart, leading to backflow of venous return and eventual venous stasis.1 Reduction of venous return together with cutaneous vasodilation is thought to induce erythrocyte extravasation.

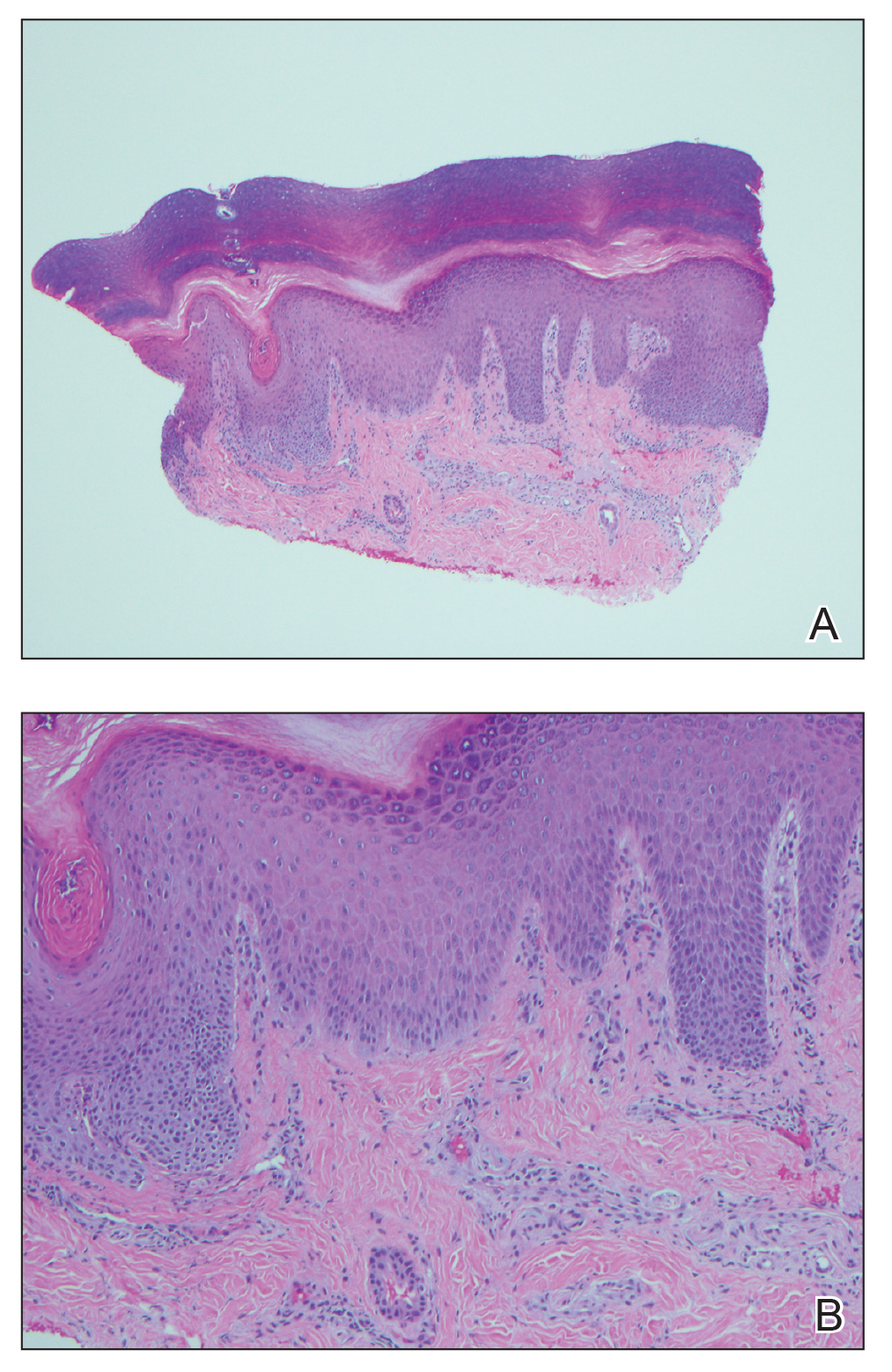

Histologic examination demonstrates features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates.2 Erythrocyte extravasation, IgM deposits, and identification of C3 also have been reported.8,9 The spontaneous resolution of EIV has led to treatment efforts being focused on preventative measures. Several cases have reported some degree of success in preventing EIV with compression therapy, venoactive drugs, systemic steroids, and application of topical steroids before exercise.3

The clinical morphology and lower leg location of EIV leads to a common misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. Clinical history of a transient nature is the mainstay in the diagnosis of EIV, and ultrasound venous reflux study may be required in some cases. Preventative measures are superior to treatment and mainly include compression therapy.

To the Editor:

The transient and generic appearance of exercise-induced vasculitis (EIV) makes it a commonly misdiagnosed condition. The lesion often is only encountered through photographs brought by the patient or by taking a thorough history. The lack of findings on clinical inspection and the generic appearance of EIV may lead to misdiagnosis as stasis dermatitis due to its presentation as erythematous lesions on the medial lower legs.

A 68-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our clinic for suspected stasis dermatitis. At presentation, no lesions were identified on the legs, but she brought photographs of an erythematous urticarial eruption on the medial lower legs, extending from just above the sock line to the mid-calves (Figure). The eruptions had occurred over the last 16 years, typically presenting suddenly after playing tennis or an extended period of walking and spontaneously resolving in 4 days. The lesions were painless, restricted to the calves, and were not pruritic, though the initial presentation 16 years prior included pruritic pigmented patches on the anterior thighs. Because the condition spontaneously improved within days, no treatment was attempted. An ultrasound venous reflux study ruled out venous reflux and stasis dermatitis.

Our patient stated that her 64-year-old sister had reported the same presentation over the last 8 years. Her physical activity was limited strictly to walking, and the lesions occurred after walking for many hours during the day in the heat, involving the medial aspects of the lower legs extending from the ankles to the full length of the calves. Her eruption was warm but was not painful or pruritic. It resolved spontaneously after 5 days with no therapy.

Our patient was advised to wear compression stockings as a preventative measure, but she did not adhere to these recommendations, stating it was impractical to wear compression garments while playing tennis.

Exercise-induced vasculitis most commonly is seen in the medial aspects of the lower extremities as an erythematous urticarial eruption or pigmented purpuric plaque rapidly occurring after a period of exercise.1,2 Lesions often are symmetric and can be pruritic and painful with a lack of systemic symptoms.3 These generic clinical manifestations may lead to a misdiagnosis of stasis dermatitis. One case report included initial treatment of presumptive cellulitis.4 Important clinical findings include a sparing of skin compressed by tight clothing such as socks, a lack of systemic symptoms, rapid appearance after exercise, and spontaneous resolution within a few days. No correlation with chronic venous disease has been demonstrated, as EIV can occur in patients with or without chronic venous insufficiency.5 Duplex ultrasound evaluation showed no venous reflux in our patient.