User login

Patch Testing: Working With Patients to Find a Relevant Allergen

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients with chronic dermatitis are frequently referred for patch testing. An in-depth conversation reviewing the patch test procedure and the many potential causes of dermatitis (eg, endogenous, allergic, irritant, seborrheic) is needed. Patients should understand the patch test process. The testing extends over a week, requiring 3 days of visits. The patches are applied at day 1 and must be kept dry and in place for 48 hours, then they are removed and evaluated. A second follow-up visit at 96 hours to 1 week after the patches are applied is done to perform a final read, interpret, and explain the final results. The patient needs to know that we are looking for an allergen that might be causing the eruption through contact exposure with the skin. The difference between patch testing and prick testing often needs to be discussed, as patients are not always aware of the difference. Explaining the need to avoid topical steroids at the patch test site, sunburn, or systemic steroids during the patch test period is also important to obtain optimal testing conditions.

Querying all exposures including work, home, personal care products, and hobbies is important to help determine which allergen series should be tested to obtain the best results. Patients need to understand that even small intermittent exposures can cause an ongoing dermatitis. If a causative allergen(s) is identified, strict avoidance can lead to clearance and resolution.

Setting expectations is important, and therefore you should discuss the possibility that no allergen will be identified while letting the patient know that this information is also useful. Also, let patients know there are other things that can be done if patch testing is negative to try and gain control of the dermatitis including laboratory tests and biopsies, which may be needed to help direct future management.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

The beauty of patch testing is that finding a relevant allergen and subsequent avoidance of that allergen often is sufficient to improve or clear the dermatitis. Detailed education regarding the allergen, where it is found, and how to avoid it are imperative in patient management. I provide the patient with information sheets or narratives found on the American Contact Dermatitis Society website (http://www.contactderm.org) as well as a list of safe products found on the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) area of the site. These tools help in patient compliance.

Go-to treatments for relevant patch test dermatitis involve topical steroids to calm the acute dermatitis while educating and instituting a personal environment free of the identified allergens. Occasionally, systemic steroids are used to provide relief and calm down an extensive dermatitis while educating, identifying, and eliminating known allergens from the patient’s environment. Identifying and eliminating an allergen can mitigate the need for chronic steroids, and the resultant side effects of hypertension, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, hyperglycemia, and gastrointestinal tract problems can be avoided. Likewise, avoidance of allergens can lead to the elimination of the need for chronic topical steroids and the resultant atrophy and striae.

Side effects of the patch test procedure itself include an allergic reaction to one of the chemicals tested (eg, gold), which is what you are looking for; persistent reactions; flaring of existing dermatitis; irritation; hyperpigmentation; and rarely anaphylaxis or infection at a patch test site. If no allergy is found, treatment of generalized dermatitis can include topical steroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors can be useful as well as narrowband UV light. Several oral medications can be used for recalcitrant patch test–negative dermatitis and the selection of the right medication is based on the patient’s comorbidities and extent of dermatitis, including systemic steroids, though long-term use is not recommended. Mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine all have side effects including liver and renal toxicity, immunosuppression, and risk for malignancy and therefore need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

How do you keep the patient compliant with treatment?

Treating allergic contact dermatitis once an allergen(s) has been identified can be challenging. Education is key so that the patient understands where the allergen is found in his/her environment and how to avoid it. Teaching the patient to read labels also is important. Providing a list of safe products simplifies compliance. Reinforcing the need for ongoing vigilance in allergen avoidance is critical to resolution of the dermatitis. Reinforcing the need for continuous avoidance is imperative, as patients sometimes become less vigilant once the dermatitis resolves and the allergen can sneak back into their environment.

What do I do if a patient refuses treatment?

Sometimes patients are so attached to a product that they do not want to stop using it even though they know it is the cause of their dermatitis. If I can help them identify a comparable product, I introduce them to it, but ultimately they get to decide if they prefer to use a product that they know is the cause of their rash or if they want to avoid it and be clear of the dermatitis. For those who do not have an allergen identified through patch testing, alternative treatments can be used. If they do not want systemic medication, I try and optimize their skin care regimen with mild soaps, bland moisturizing creams, and short lukewarm showers, which often is not enough and eventually due to ongoing itch patients decide to discuss and pursue treatment options.

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients with chronic dermatitis are frequently referred for patch testing. An in-depth conversation reviewing the patch test procedure and the many potential causes of dermatitis (eg, endogenous, allergic, irritant, seborrheic) is needed. Patients should understand the patch test process. The testing extends over a week, requiring 3 days of visits. The patches are applied at day 1 and must be kept dry and in place for 48 hours, then they are removed and evaluated. A second follow-up visit at 96 hours to 1 week after the patches are applied is done to perform a final read, interpret, and explain the final results. The patient needs to know that we are looking for an allergen that might be causing the eruption through contact exposure with the skin. The difference between patch testing and prick testing often needs to be discussed, as patients are not always aware of the difference. Explaining the need to avoid topical steroids at the patch test site, sunburn, or systemic steroids during the patch test period is also important to obtain optimal testing conditions.

Querying all exposures including work, home, personal care products, and hobbies is important to help determine which allergen series should be tested to obtain the best results. Patients need to understand that even small intermittent exposures can cause an ongoing dermatitis. If a causative allergen(s) is identified, strict avoidance can lead to clearance and resolution.

Setting expectations is important, and therefore you should discuss the possibility that no allergen will be identified while letting the patient know that this information is also useful. Also, let patients know there are other things that can be done if patch testing is negative to try and gain control of the dermatitis including laboratory tests and biopsies, which may be needed to help direct future management.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

The beauty of patch testing is that finding a relevant allergen and subsequent avoidance of that allergen often is sufficient to improve or clear the dermatitis. Detailed education regarding the allergen, where it is found, and how to avoid it are imperative in patient management. I provide the patient with information sheets or narratives found on the American Contact Dermatitis Society website (http://www.contactderm.org) as well as a list of safe products found on the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) area of the site. These tools help in patient compliance.

Go-to treatments for relevant patch test dermatitis involve topical steroids to calm the acute dermatitis while educating and instituting a personal environment free of the identified allergens. Occasionally, systemic steroids are used to provide relief and calm down an extensive dermatitis while educating, identifying, and eliminating known allergens from the patient’s environment. Identifying and eliminating an allergen can mitigate the need for chronic steroids, and the resultant side effects of hypertension, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, hyperglycemia, and gastrointestinal tract problems can be avoided. Likewise, avoidance of allergens can lead to the elimination of the need for chronic topical steroids and the resultant atrophy and striae.

Side effects of the patch test procedure itself include an allergic reaction to one of the chemicals tested (eg, gold), which is what you are looking for; persistent reactions; flaring of existing dermatitis; irritation; hyperpigmentation; and rarely anaphylaxis or infection at a patch test site. If no allergy is found, treatment of generalized dermatitis can include topical steroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors can be useful as well as narrowband UV light. Several oral medications can be used for recalcitrant patch test–negative dermatitis and the selection of the right medication is based on the patient’s comorbidities and extent of dermatitis, including systemic steroids, though long-term use is not recommended. Mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine all have side effects including liver and renal toxicity, immunosuppression, and risk for malignancy and therefore need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

How do you keep the patient compliant with treatment?

Treating allergic contact dermatitis once an allergen(s) has been identified can be challenging. Education is key so that the patient understands where the allergen is found in his/her environment and how to avoid it. Teaching the patient to read labels also is important. Providing a list of safe products simplifies compliance. Reinforcing the need for ongoing vigilance in allergen avoidance is critical to resolution of the dermatitis. Reinforcing the need for continuous avoidance is imperative, as patients sometimes become less vigilant once the dermatitis resolves and the allergen can sneak back into their environment.

What do I do if a patient refuses treatment?

Sometimes patients are so attached to a product that they do not want to stop using it even though they know it is the cause of their dermatitis. If I can help them identify a comparable product, I introduce them to it, but ultimately they get to decide if they prefer to use a product that they know is the cause of their rash or if they want to avoid it and be clear of the dermatitis. For those who do not have an allergen identified through patch testing, alternative treatments can be used. If they do not want systemic medication, I try and optimize their skin care regimen with mild soaps, bland moisturizing creams, and short lukewarm showers, which often is not enough and eventually due to ongoing itch patients decide to discuss and pursue treatment options.

What do your patients need to know at the first visit?

Patients with chronic dermatitis are frequently referred for patch testing. An in-depth conversation reviewing the patch test procedure and the many potential causes of dermatitis (eg, endogenous, allergic, irritant, seborrheic) is needed. Patients should understand the patch test process. The testing extends over a week, requiring 3 days of visits. The patches are applied at day 1 and must be kept dry and in place for 48 hours, then they are removed and evaluated. A second follow-up visit at 96 hours to 1 week after the patches are applied is done to perform a final read, interpret, and explain the final results. The patient needs to know that we are looking for an allergen that might be causing the eruption through contact exposure with the skin. The difference between patch testing and prick testing often needs to be discussed, as patients are not always aware of the difference. Explaining the need to avoid topical steroids at the patch test site, sunburn, or systemic steroids during the patch test period is also important to obtain optimal testing conditions.

Querying all exposures including work, home, personal care products, and hobbies is important to help determine which allergen series should be tested to obtain the best results. Patients need to understand that even small intermittent exposures can cause an ongoing dermatitis. If a causative allergen(s) is identified, strict avoidance can lead to clearance and resolution.

Setting expectations is important, and therefore you should discuss the possibility that no allergen will be identified while letting the patient know that this information is also useful. Also, let patients know there are other things that can be done if patch testing is negative to try and gain control of the dermatitis including laboratory tests and biopsies, which may be needed to help direct future management.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

The beauty of patch testing is that finding a relevant allergen and subsequent avoidance of that allergen often is sufficient to improve or clear the dermatitis. Detailed education regarding the allergen, where it is found, and how to avoid it are imperative in patient management. I provide the patient with information sheets or narratives found on the American Contact Dermatitis Society website (http://www.contactderm.org) as well as a list of safe products found on the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) area of the site. These tools help in patient compliance.

Go-to treatments for relevant patch test dermatitis involve topical steroids to calm the acute dermatitis while educating and instituting a personal environment free of the identified allergens. Occasionally, systemic steroids are used to provide relief and calm down an extensive dermatitis while educating, identifying, and eliminating known allergens from the patient’s environment. Identifying and eliminating an allergen can mitigate the need for chronic steroids, and the resultant side effects of hypertension, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, hyperglycemia, and gastrointestinal tract problems can be avoided. Likewise, avoidance of allergens can lead to the elimination of the need for chronic topical steroids and the resultant atrophy and striae.

Side effects of the patch test procedure itself include an allergic reaction to one of the chemicals tested (eg, gold), which is what you are looking for; persistent reactions; flaring of existing dermatitis; irritation; hyperpigmentation; and rarely anaphylaxis or infection at a patch test site. If no allergy is found, treatment of generalized dermatitis can include topical steroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors can be useful as well as narrowband UV light. Several oral medications can be used for recalcitrant patch test–negative dermatitis and the selection of the right medication is based on the patient’s comorbidities and extent of dermatitis, including systemic steroids, though long-term use is not recommended. Mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine all have side effects including liver and renal toxicity, immunosuppression, and risk for malignancy and therefore need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

How do you keep the patient compliant with treatment?

Treating allergic contact dermatitis once an allergen(s) has been identified can be challenging. Education is key so that the patient understands where the allergen is found in his/her environment and how to avoid it. Teaching the patient to read labels also is important. Providing a list of safe products simplifies compliance. Reinforcing the need for ongoing vigilance in allergen avoidance is critical to resolution of the dermatitis. Reinforcing the need for continuous avoidance is imperative, as patients sometimes become less vigilant once the dermatitis resolves and the allergen can sneak back into their environment.

What do I do if a patient refuses treatment?

Sometimes patients are so attached to a product that they do not want to stop using it even though they know it is the cause of their dermatitis. If I can help them identify a comparable product, I introduce them to it, but ultimately they get to decide if they prefer to use a product that they know is the cause of their rash or if they want to avoid it and be clear of the dermatitis. For those who do not have an allergen identified through patch testing, alternative treatments can be used. If they do not want systemic medication, I try and optimize their skin care regimen with mild soaps, bland moisturizing creams, and short lukewarm showers, which often is not enough and eventually due to ongoing itch patients decide to discuss and pursue treatment options.

Atopic Dermatitis Treatments Moving Forward: Report From the AAD Meeting

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Although psoriasis was once at the forefront of therapeutic advancements in dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) is now taking center stage with several new treatments in the pipeline. Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky provides an overview of the future of AD treatment, which includes new topical and systemic agents that currently are moving forward in advanced clinical trials or are close to registration. She also discusses strategies for improving disease management in AD patients, noting that prevention and education of both patients and their caregivers are key to effective treatment.

Night of the Living Thrips: An Unusual Outbreak of Thysanoptera Dermatitis

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

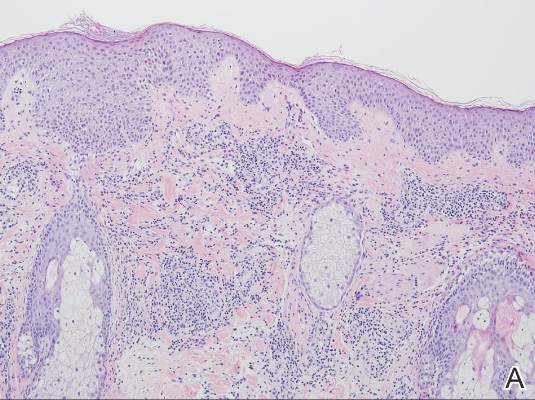

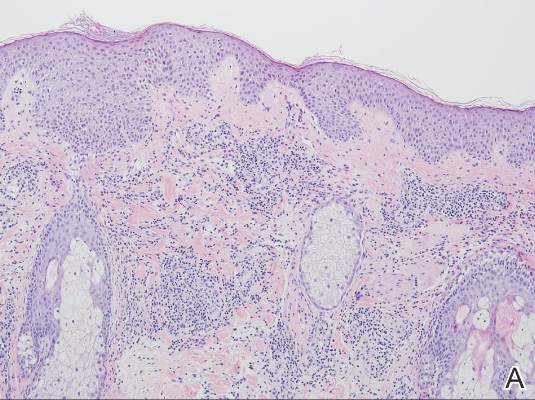

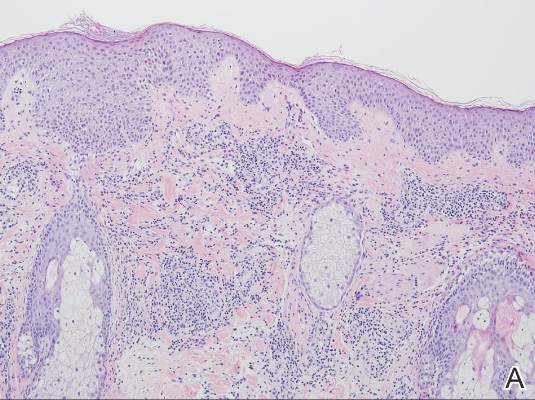

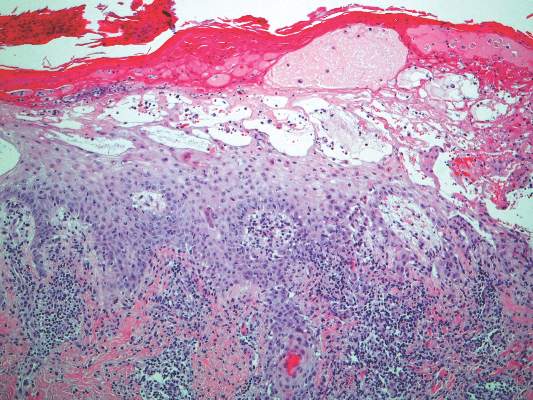

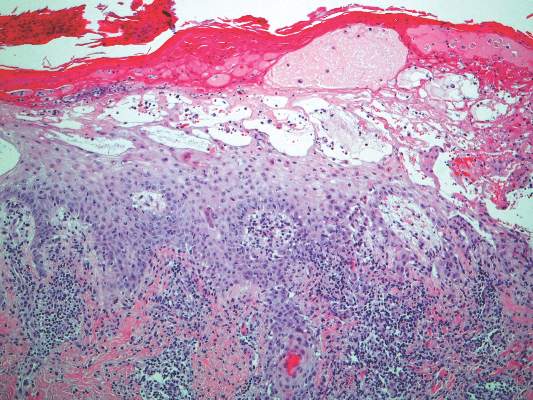

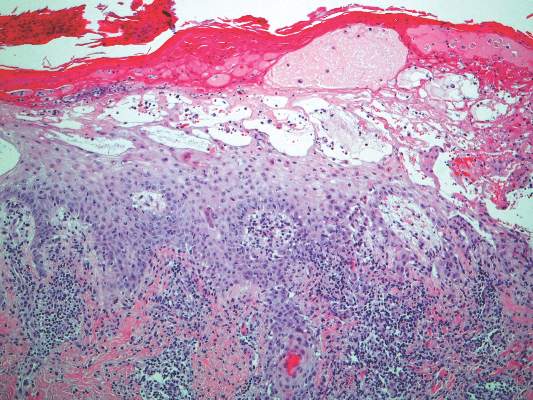

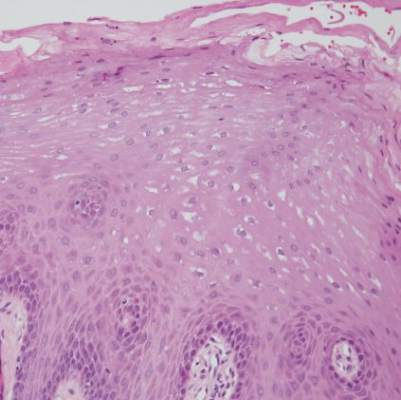

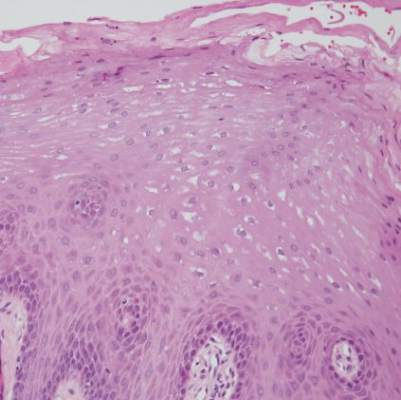

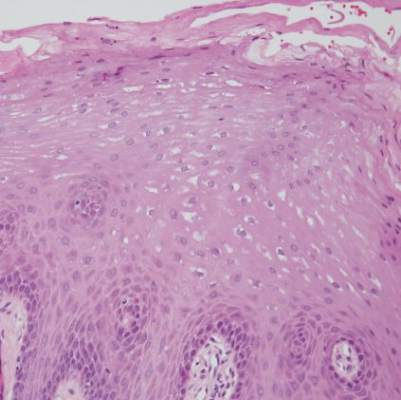

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

Practice Points

- Thysanoptera dermatitis presents as a diffuse cutaneous eruption consisting of scattered pruritic papules to exposed skin surfaces.

- The importance of considering the environmental component of a cutaneous eruption via a thorough understanding of local flora and fauna cannot be underestimated.

- The role of a dermatologist in the rapid identification of a cutaneous eruption in the setting of an acute cluster outbreak is of utmost importance to assist with eliminating infectious and environmental public health threats from the differential diagnosis.

Prolonged Pustular Eruption From Hydroxychloroquine: An Unusual Case of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon cutaneous eruption characterized by acute, extensive, nonfollicular, sterile pustules accompanied by widespread erythema, fever, and leukocytosis. The clinical hallmark is superficial, sterile, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, which typically starts on the face, axilla, and groin and then progresses to most of the body. Approximately 90% of AGEP cases are due to drug hypersensitivity to a newly initiated medication, while the other 10% are thought to be viral in origin.1 Discontinuation of the offending agent may allow for complete resolution within 15 days. Agents commonly implicated in causing AGEP are antibiotics such as aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins.2 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) also has been reported to cause AGEP,3-7 with resolution shortly after discontinuation of the drug,4,6 close to the characteristic 15 days of AGEP due to alternate medications.We report an unusual case of HCQ-induced AGEP that lasted far beyond the typical 15 days. We also review other cases of HCQ-induced AGEP and possible mechanisms to explain our patient’s symptoms.

|

|

| Figure 1. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis extending to the chest and upper extremities (A) as well as the shoulders and back (B). |

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman who was previously diagnosed with rheumatoid factor seronegative, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis, which was only moderately controlled with low-dose prednisone (5 mg once daily) after 2 months of treatment, was started on oral HCQ 200 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. Two weeks after starting HCQ treatment, she developed a pustular exanthem that gradually spread on the back over the next 24 to 48 hours. She described the eruption initially as pruritic, but she then developed painful stinging sensations as the eruption spread. She visited her primary care physician the next day and stopped the HCQ after 14 days following a discussion with the physician. Her prednisone dosage was increased to 50 mg daily for 5 days, but by the fifth day the lesions had spread to the face, full back, shoulders, and upper chest (Figure 1). Morphologically, she presented to the dermatology clinic with innumerable 1- to 2-mm pustules with confluent erythema on the back, extending to the forearms (Figure 2). She also had scattered erythematous macules and papules on the buttocks, legs, and plantar surfaces of the feet. A biopsy taken from the right forearm demonstrated subcorneal pustular dermatosis consistent with AGEP. Prednisone 50 mg once daily was continued. She was scheduled for a follow-up in 3 days but instead went to the emergency department 1 day later due to worsening of the eruption, fever, and malaise. On examination there were multiple discrete and confluent erythematous plaques on the face that extended to the lower extremities. Pustules and scales were noted on the back. New pustules had developed on the hands and feet with intense pruritus.

On admission, her vitals were stable with mild tachycardia. Aggressive intravenous hydration was administered. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 28.3×109/L (reference range, 4.5–10×109/L). She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg once daily; topical steroid wet wraps with triamcinolone 0.1% were applied to the trunk, arms, legs, and abdomen twice daily; and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% was applied to the face and intertriginous areas 3 times daily. Over the next 2 days, eruptions continued to persist and the patient reported worsening of pain despite treatment. On day 3, intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg was switched to oral prednisone 80 mg once daily.

Over the ensuing 5 days, recurrent episodes of erythema on the back had spread to the extremities. After 1 week in the hospital, the diffuse erythema had improved and she had widespread desquamation. She was discharged and prescribed oral prednisone 80 mg once daily and topical therapy twice daily. The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 4 days after discharge with a mildly pruritic eruption on the trunk and proximal lower extremities but otherwise was doing well. She was instructed to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every 4 days.

At a follow-up 3 weeks later, she had persistent stinging and tingling sensations, widespread xerosis, and diffuse patchy erythema primarily on the back and proximal extremities, which flared over the last week. The patient reported waxing and waning of the erythema and pruritus since being discharged from the hospital. Despite the recent flare, which was her fourth flare of cutaneous eruption, she showed marked improvement since her initial examination and 40 days after discontinuation of HCQ. She was taking prednisone 40 mg once daily and was advised to continue tapering the dose by 2 mg every 6 to 8 days as tolerated. At 81 days after AGEP onset, the eruption had resolved and the patient was back to her baseline prednisone dosage of 5 mg once daily.

Comment

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is characterized by the sudden appearance of erythema and hundreds of sterile nonfollicular pustules, fever, and leukocytosis. Histologically, AGEP is composed of subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules, edema of the papillary dermis, and perivascular infiltrates of neutrophils and possible eosinophils. The pathogenesis of AGEP is thought to be due to the release of increased amounts of IL-8 by T cells, which attract and activate polymorphonuclear neutrophils.1 Psoriasiform changes are uncommon. Clinically, AGEP is similar to pustular psoriasis but has shown to be its own distinct entity. Unlike patients with pustular psoriasis, patients with AGEP lack a personal or family history of psoriasis or arthritis, have a shorter duration of pustules and fever, and have a history of new medication administration. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustulosis, IgA pemphigus, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.

In AGEP, the average duration of medication exposure prior to onset varies depending on the causative agent. Antibiotics consistently have been shown to trigger symptoms after 1 day, whereas other medications, including HCQ, averaged closer to 11 days. Hydroxychloroquine is widely used to treat rheumatic and dermatologic diseases and has previously been reported to be a less common cause of AGEP3; however, a EuroSCAR study found that patients treated with HCQ were at a greater risk for AGEP.2 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually follows a benign self-limiting course. Within days the eruption gradually evolves into superficial desquamation. Characteristically, removal of the offending agent typically leads to spontaneous resolution in less than 15 days. Resolution is generally without complications and, therefore, treatment is not always necessary. Death has been reported in up to 2% of cases.8 There are no known therapies that prevent the spread of lesions or further decline of the patient’s condition. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to treat AGEP with variable results.1,5

Unique to our patient were recurring exacerbations of the cutaneous lesions beyond the typical 15 days for complete resolution. Even up to 40 days after discontinuation of medication, our patient continued to experience cutaneous symptoms. Other reported cases have not described patients with symptoms flaring or continuing for this extended period of time. A review of 7 external AGEP cases caused by HCQ (identified through a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis or eruption with hydroxychloroquine or plaquenil) showed resolution within 8 days to 3 weeks (Table).3-6,8 One case report documented disease exacerbation on day 18 after tapering the methylprednisolone dose. This patient was then treated with cyclosporine and had a prompt recovery.5 One case of AGEP due to terbinafine reported continual symptoms for approximately 4 weeks after terbinafine discontinuation.9 Our patient’s continual symptoms beyond the typical 15 days may be due to the long half-life of HCQ, which is approximately 40 to 50 days. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to control severe eruptions in AGEP and were administered to our patient; however, their utility in shortening the duration or reducing the severity of the eruption has not been proven.

Conclusion

Hydroxychloroquine is a commonly used agent for dermatologic and rheumatologic conditions. The rare but severe acute adverse event of AGEP warrants caution in HCQ use. Correct diagnosis of AGEP with HCQ cessation generally is effective as therapy. Our patient demonstrated that not all cases of AGEP show rapid resolution of cutaneous symptoms after cessation of the drug. Hydroxychloroquine’s extended half-life of 40 to 50 days surpasses that of other medications known to cause AGEP and may explain our patient’s symptoms beyond the usual course.

1. Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts [published online June 14, 2010]. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:425-433.

2. Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)-results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR) [published online September 13, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-996.

3. Park JJ, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. A case of hydroxy-chloroquine induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by accidental oral provocation [published online February 28, 2010]. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:102-105.

4. Lateef A, Tan KB, Lau TC. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by hydroxychloroquine [published online August 30, 2009]. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:1449-1452.

5. Di Lernia V, Grenzi L, Guareschi E, et al. Rapid clearing of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis after administration of ciclosporin [published online July 29, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e757-e759.

6. Paradisi A, Bugatti L, Sisto T, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hydroxychloroquine: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2008;30:930-940.

7. Choi MJ, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of 36 Korean patients with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a case series and review of the literature [published online May 17, 2010]. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:163-169.

8. Martins A, Lopes LC, Paiva Lopes MJ, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hydroxychloroquine. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:317-318.

9. Lombardo M, Cerati M, Pazzaglia A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:158-159.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon cutaneous eruption characterized by acute, extensive, nonfollicular, sterile pustules accompanied by widespread erythema, fever, and leukocytosis. The clinical hallmark is superficial, sterile, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, which typically starts on the face, axilla, and groin and then progresses to most of the body. Approximately 90% of AGEP cases are due to drug hypersensitivity to a newly initiated medication, while the other 10% are thought to be viral in origin.1 Discontinuation of the offending agent may allow for complete resolution within 15 days. Agents commonly implicated in causing AGEP are antibiotics such as aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins.2 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) also has been reported to cause AGEP,3-7 with resolution shortly after discontinuation of the drug,4,6 close to the characteristic 15 days of AGEP due to alternate medications.We report an unusual case of HCQ-induced AGEP that lasted far beyond the typical 15 days. We also review other cases of HCQ-induced AGEP and possible mechanisms to explain our patient’s symptoms.

|

|

| Figure 1. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis extending to the chest and upper extremities (A) as well as the shoulders and back (B). |

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman who was previously diagnosed with rheumatoid factor seronegative, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis, which was only moderately controlled with low-dose prednisone (5 mg once daily) after 2 months of treatment, was started on oral HCQ 200 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. Two weeks after starting HCQ treatment, she developed a pustular exanthem that gradually spread on the back over the next 24 to 48 hours. She described the eruption initially as pruritic, but she then developed painful stinging sensations as the eruption spread. She visited her primary care physician the next day and stopped the HCQ after 14 days following a discussion with the physician. Her prednisone dosage was increased to 50 mg daily for 5 days, but by the fifth day the lesions had spread to the face, full back, shoulders, and upper chest (Figure 1). Morphologically, she presented to the dermatology clinic with innumerable 1- to 2-mm pustules with confluent erythema on the back, extending to the forearms (Figure 2). She also had scattered erythematous macules and papules on the buttocks, legs, and plantar surfaces of the feet. A biopsy taken from the right forearm demonstrated subcorneal pustular dermatosis consistent with AGEP. Prednisone 50 mg once daily was continued. She was scheduled for a follow-up in 3 days but instead went to the emergency department 1 day later due to worsening of the eruption, fever, and malaise. On examination there were multiple discrete and confluent erythematous plaques on the face that extended to the lower extremities. Pustules and scales were noted on the back. New pustules had developed on the hands and feet with intense pruritus.

On admission, her vitals were stable with mild tachycardia. Aggressive intravenous hydration was administered. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 28.3×109/L (reference range, 4.5–10×109/L). She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg once daily; topical steroid wet wraps with triamcinolone 0.1% were applied to the trunk, arms, legs, and abdomen twice daily; and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% was applied to the face and intertriginous areas 3 times daily. Over the next 2 days, eruptions continued to persist and the patient reported worsening of pain despite treatment. On day 3, intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg was switched to oral prednisone 80 mg once daily.

Over the ensuing 5 days, recurrent episodes of erythema on the back had spread to the extremities. After 1 week in the hospital, the diffuse erythema had improved and she had widespread desquamation. She was discharged and prescribed oral prednisone 80 mg once daily and topical therapy twice daily. The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 4 days after discharge with a mildly pruritic eruption on the trunk and proximal lower extremities but otherwise was doing well. She was instructed to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every 4 days.

At a follow-up 3 weeks later, she had persistent stinging and tingling sensations, widespread xerosis, and diffuse patchy erythema primarily on the back and proximal extremities, which flared over the last week. The patient reported waxing and waning of the erythema and pruritus since being discharged from the hospital. Despite the recent flare, which was her fourth flare of cutaneous eruption, she showed marked improvement since her initial examination and 40 days after discontinuation of HCQ. She was taking prednisone 40 mg once daily and was advised to continue tapering the dose by 2 mg every 6 to 8 days as tolerated. At 81 days after AGEP onset, the eruption had resolved and the patient was back to her baseline prednisone dosage of 5 mg once daily.

Comment

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is characterized by the sudden appearance of erythema and hundreds of sterile nonfollicular pustules, fever, and leukocytosis. Histologically, AGEP is composed of subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules, edema of the papillary dermis, and perivascular infiltrates of neutrophils and possible eosinophils. The pathogenesis of AGEP is thought to be due to the release of increased amounts of IL-8 by T cells, which attract and activate polymorphonuclear neutrophils.1 Psoriasiform changes are uncommon. Clinically, AGEP is similar to pustular psoriasis but has shown to be its own distinct entity. Unlike patients with pustular psoriasis, patients with AGEP lack a personal or family history of psoriasis or arthritis, have a shorter duration of pustules and fever, and have a history of new medication administration. Other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustulosis, IgA pemphigus, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.

In AGEP, the average duration of medication exposure prior to onset varies depending on the causative agent. Antibiotics consistently have been shown to trigger symptoms after 1 day, whereas other medications, including HCQ, averaged closer to 11 days. Hydroxychloroquine is widely used to treat rheumatic and dermatologic diseases and has previously been reported to be a less common cause of AGEP3; however, a EuroSCAR study found that patients treated with HCQ were at a greater risk for AGEP.2 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually follows a benign self-limiting course. Within days the eruption gradually evolves into superficial desquamation. Characteristically, removal of the offending agent typically leads to spontaneous resolution in less than 15 days. Resolution is generally without complications and, therefore, treatment is not always necessary. Death has been reported in up to 2% of cases.8 There are no known therapies that prevent the spread of lesions or further decline of the patient’s condition. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to treat AGEP with variable results.1,5

Unique to our patient were recurring exacerbations of the cutaneous lesions beyond the typical 15 days for complete resolution. Even up to 40 days after discontinuation of medication, our patient continued to experience cutaneous symptoms. Other reported cases have not described patients with symptoms flaring or continuing for this extended period of time. A review of 7 external AGEP cases caused by HCQ (identified through a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis or eruption with hydroxychloroquine or plaquenil) showed resolution within 8 days to 3 weeks (Table).3-6,8 One case report documented disease exacerbation on day 18 after tapering the methylprednisolone dose. This patient was then treated with cyclosporine and had a prompt recovery.5 One case of AGEP due to terbinafine reported continual symptoms for approximately 4 weeks after terbinafine discontinuation.9 Our patient’s continual symptoms beyond the typical 15 days may be due to the long half-life of HCQ, which is approximately 40 to 50 days. Systemic corticosteroids often are used to control severe eruptions in AGEP and were administered to our patient; however, their utility in shortening the duration or reducing the severity of the eruption has not been proven.

Conclusion

Hydroxychloroquine is a commonly used agent for dermatologic and rheumatologic conditions. The rare but severe acute adverse event of AGEP warrants caution in HCQ use. Correct diagnosis of AGEP with HCQ cessation generally is effective as therapy. Our patient demonstrated that not all cases of AGEP show rapid resolution of cutaneous symptoms after cessation of the drug. Hydroxychloroquine’s extended half-life of 40 to 50 days surpasses that of other medications known to cause AGEP and may explain our patient’s symptoms beyond the usual course.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an uncommon cutaneous eruption characterized by acute, extensive, nonfollicular, sterile pustules accompanied by widespread erythema, fever, and leukocytosis. The clinical hallmark is superficial, sterile, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, which typically starts on the face, axilla, and groin and then progresses to most of the body. Approximately 90% of AGEP cases are due to drug hypersensitivity to a newly initiated medication, while the other 10% are thought to be viral in origin.1 Discontinuation of the offending agent may allow for complete resolution within 15 days. Agents commonly implicated in causing AGEP are antibiotics such as aminopenicillins, macrolides, and cephalosporins.2 Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) also has been reported to cause AGEP,3-7 with resolution shortly after discontinuation of the drug,4,6 close to the characteristic 15 days of AGEP due to alternate medications.We report an unusual case of HCQ-induced AGEP that lasted far beyond the typical 15 days. We also review other cases of HCQ-induced AGEP and possible mechanisms to explain our patient’s symptoms.

|

|

| Figure 1. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis extending to the chest and upper extremities (A) as well as the shoulders and back (B). |

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman who was previously diagnosed with rheumatoid factor seronegative, nonerosive rheumatoid arthritis, which was only moderately controlled with low-dose prednisone (5 mg once daily) after 2 months of treatment, was started on oral HCQ 200 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. Two weeks after starting HCQ treatment, she developed a pustular exanthem that gradually spread on the back over the next 24 to 48 hours. She described the eruption initially as pruritic, but she then developed painful stinging sensations as the eruption spread. She visited her primary care physician the next day and stopped the HCQ after 14 days following a discussion with the physician. Her prednisone dosage was increased to 50 mg daily for 5 days, but by the fifth day the lesions had spread to the face, full back, shoulders, and upper chest (Figure 1). Morphologically, she presented to the dermatology clinic with innumerable 1- to 2-mm pustules with confluent erythema on the back, extending to the forearms (Figure 2). She also had scattered erythematous macules and papules on the buttocks, legs, and plantar surfaces of the feet. A biopsy taken from the right forearm demonstrated subcorneal pustular dermatosis consistent with AGEP. Prednisone 50 mg once daily was continued. She was scheduled for a follow-up in 3 days but instead went to the emergency department 1 day later due to worsening of the eruption, fever, and malaise. On examination there were multiple discrete and confluent erythematous plaques on the face that extended to the lower extremities. Pustules and scales were noted on the back. New pustules had developed on the hands and feet with intense pruritus.

On admission, her vitals were stable with mild tachycardia. Aggressive intravenous hydration was administered. Her white blood cell count was elevated at 28.3×109/L (reference range, 4.5–10×109/L). She was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg once daily; topical steroid wet wraps with triamcinolone 0.1% were applied to the trunk, arms, legs, and abdomen twice daily; and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% was applied to the face and intertriginous areas 3 times daily. Over the next 2 days, eruptions continued to persist and the patient reported worsening of pain despite treatment. On day 3, intravenous methylprednisolone 100 mg was switched to oral prednisone 80 mg once daily.

Over the ensuing 5 days, recurrent episodes of erythema on the back had spread to the extremities. After 1 week in the hospital, the diffuse erythema had improved and she had widespread desquamation. She was discharged and prescribed oral prednisone 80 mg once daily and topical therapy twice daily. The patient followed up in the dermatology clinic 4 days after discharge with a mildly pruritic eruption on the trunk and proximal lower extremities but otherwise was doing well. She was instructed to taper the prednisone by 10 mg every 4 days.

At a follow-up 3 weeks later, she had persistent stinging and tingling sensations, widespread xerosis, and diffuse patchy erythema primarily on the back and proximal extremities, which flared over the last week. The patient reported waxing and waning of the erythema and pruritus since being discharged from the hospital. Despite the recent flare, which was her fourth flare of cutaneous eruption, she showed marked improvement since her initial examination and 40 days after discontinuation of HCQ. She was taking prednisone 40 mg once daily and was advised to continue tapering the dose by 2 mg every 6 to 8 days as tolerated. At 81 days after AGEP onset, the eruption had resolved and the patient was back to her baseline prednisone dosage of 5 mg once daily.

Comment