User login

Diffuse Rash With Associated Ulceration

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

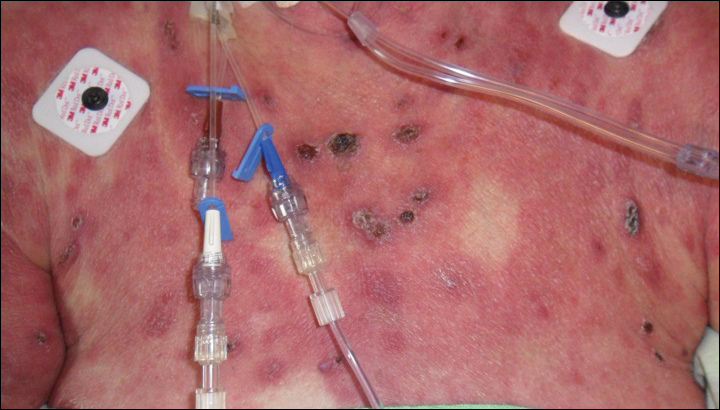

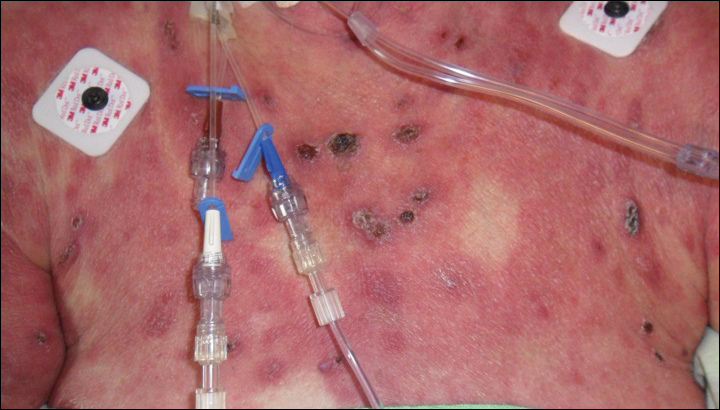

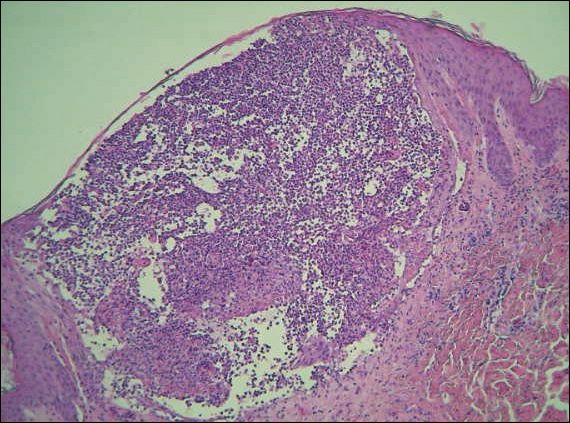

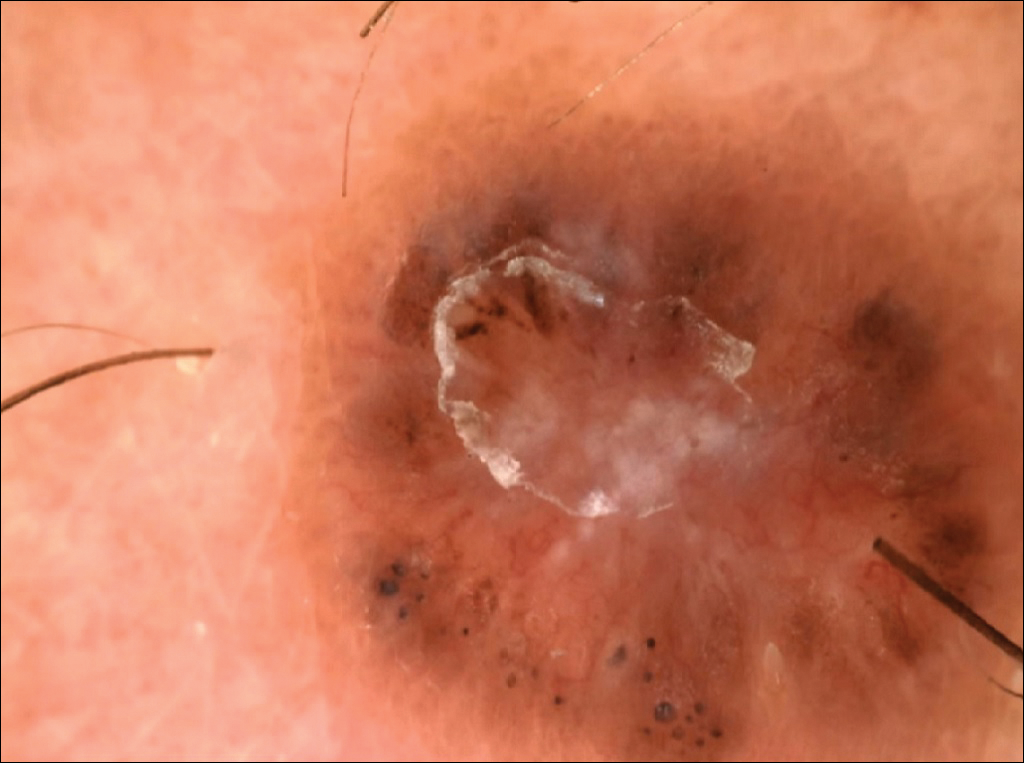

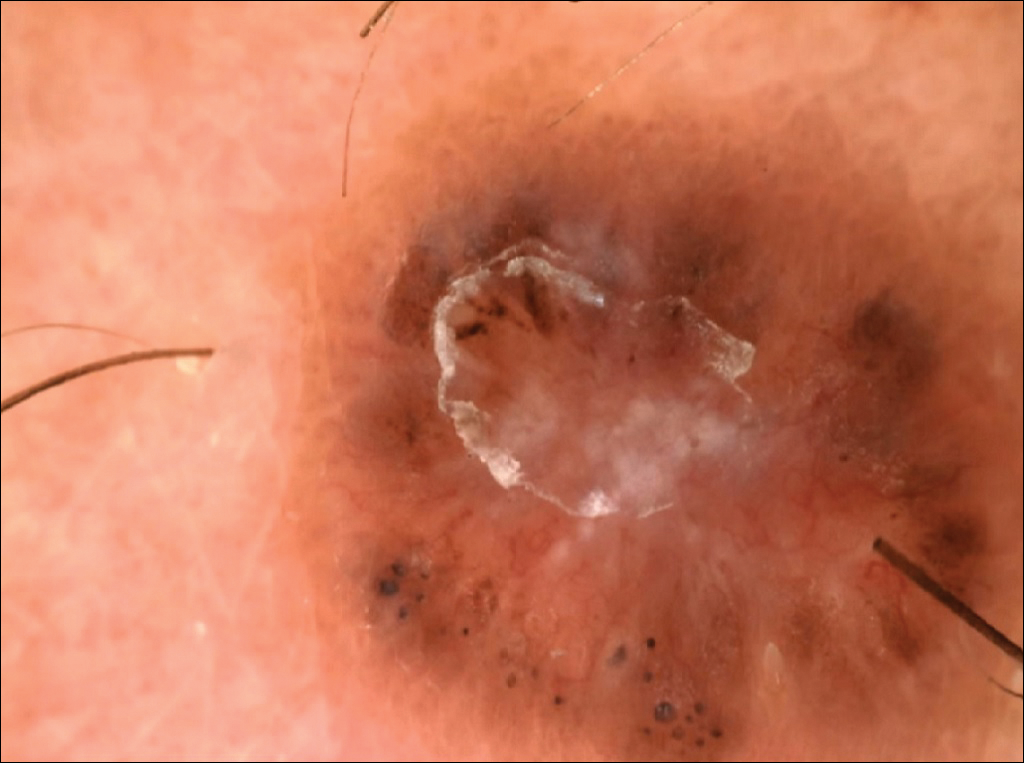

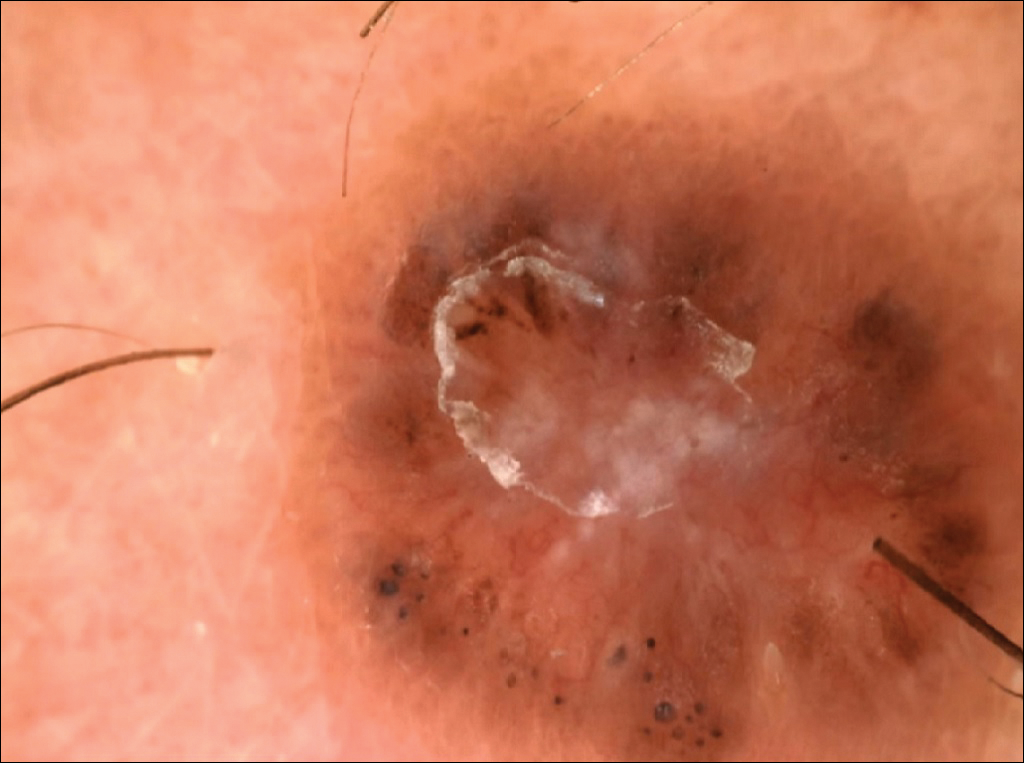

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

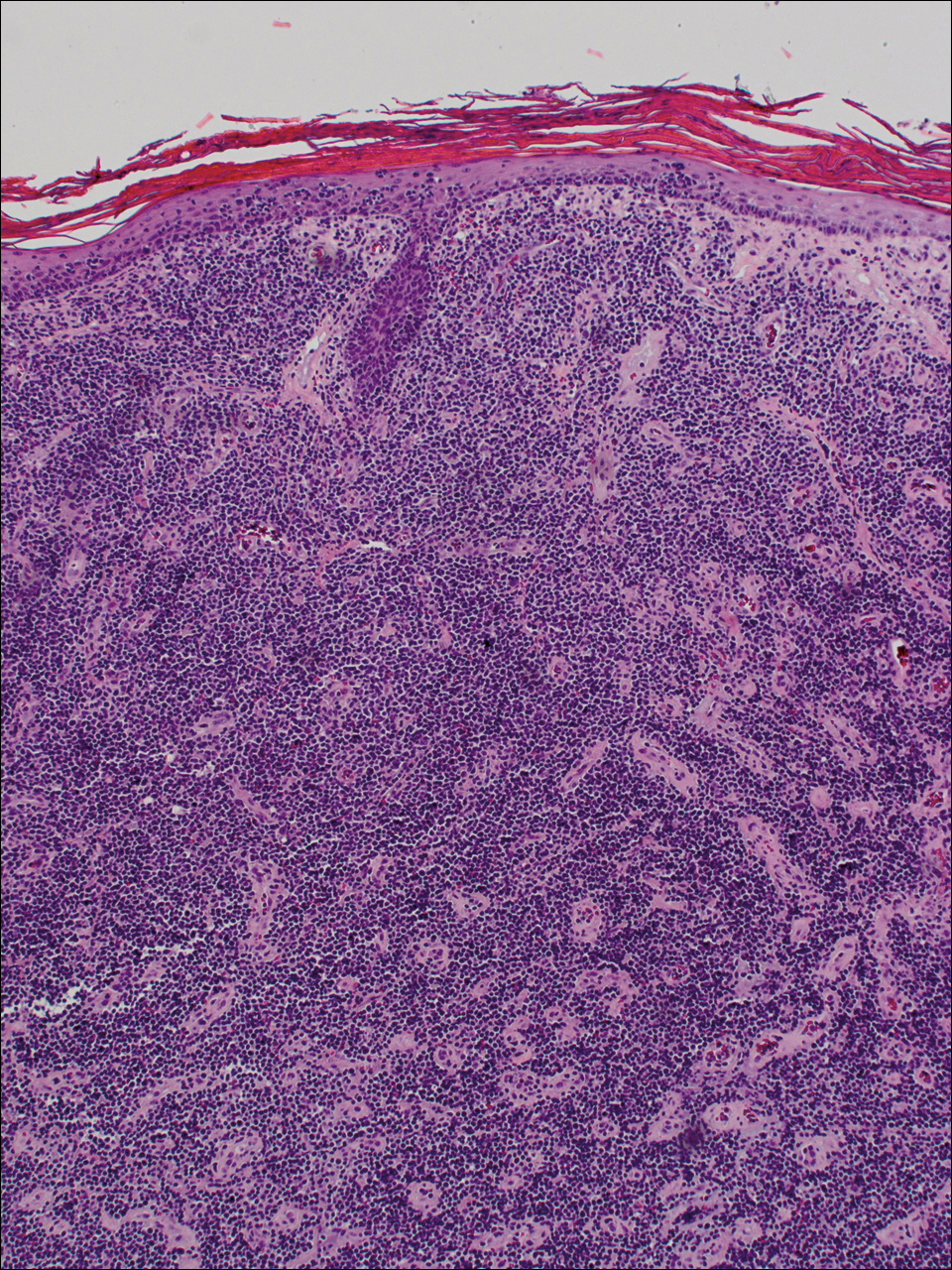

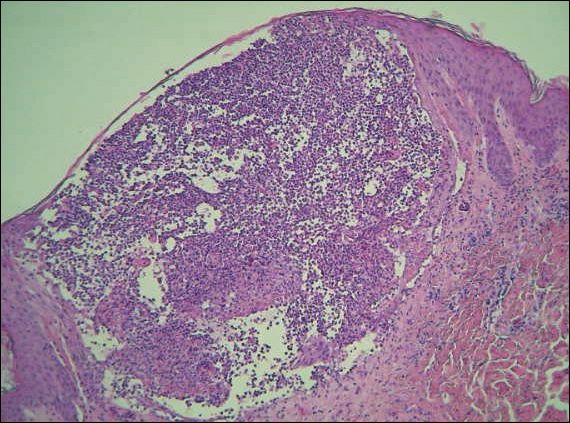

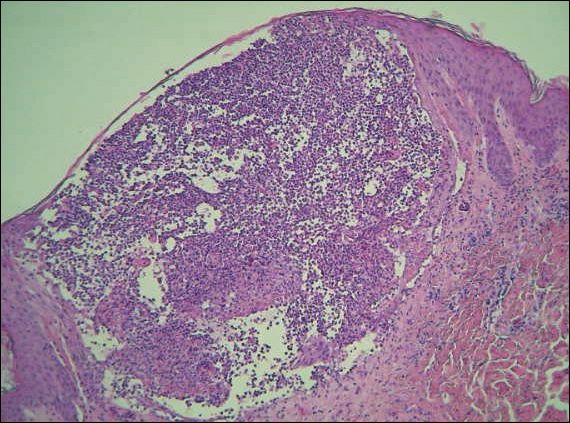

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

A 72-year-old woman who was admitted for pneumonia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure was seen for an inpatient consultation for a diffuse rash with associated ulceration. She reported a rash of 20 months' duration that began on the legs and then spread to the trunk, arms, head, and neck with minimal pruritus and no pain or photosensitivity. She had been treated with hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone without improvement. The patient noted recent ulceration on the rash. Physical examination revealed violaceous patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors with rare ulceration involving the face, trunk, and extremities. Biopsy showed a diffuse infiltration of the dermis with medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm and round to irregular hyperchromatic nuclei with clumped chromatin. Epidermotropism with small collections of atypical lymphocytes also was present within the epidermis.

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis Presenting With Purpura

To the Editor:

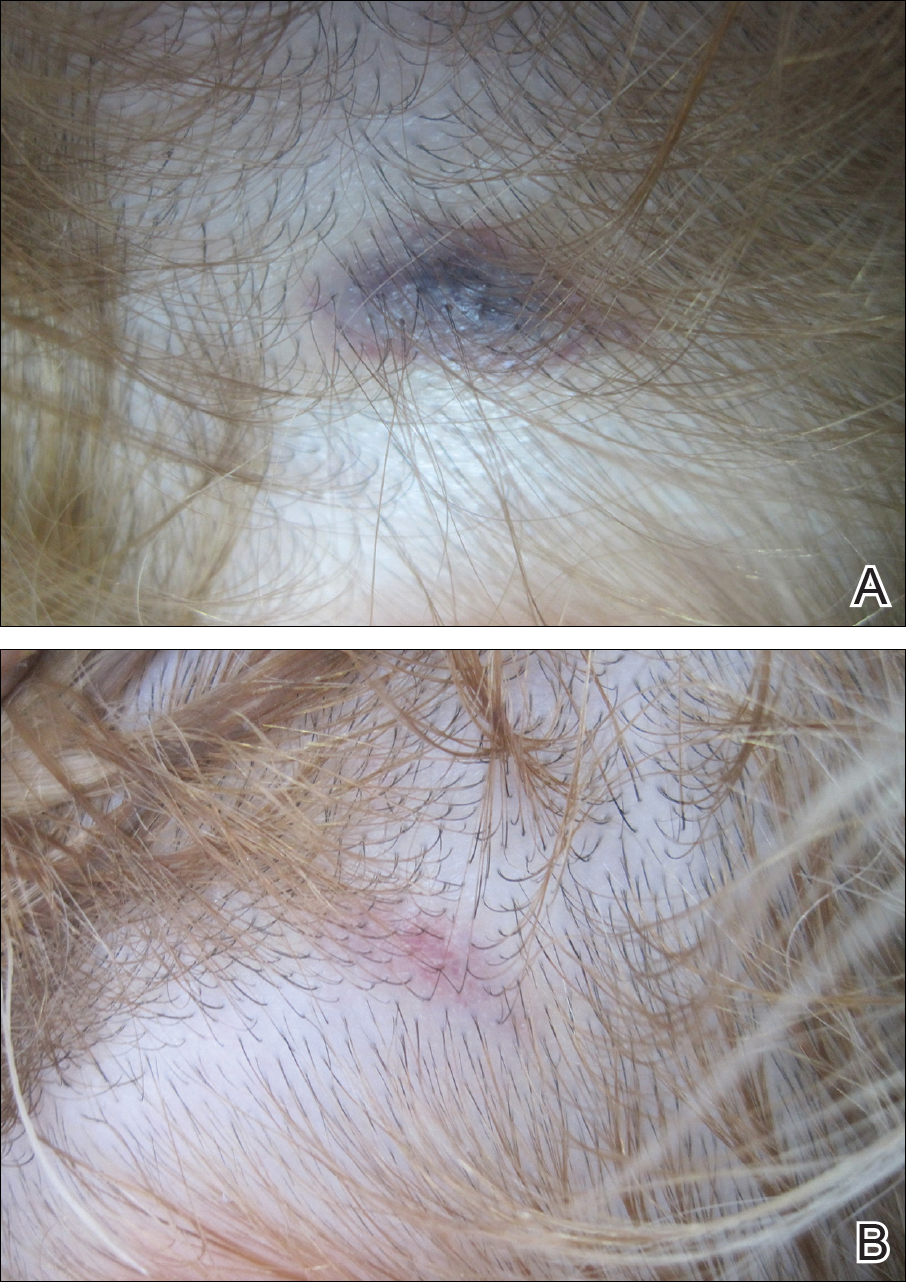

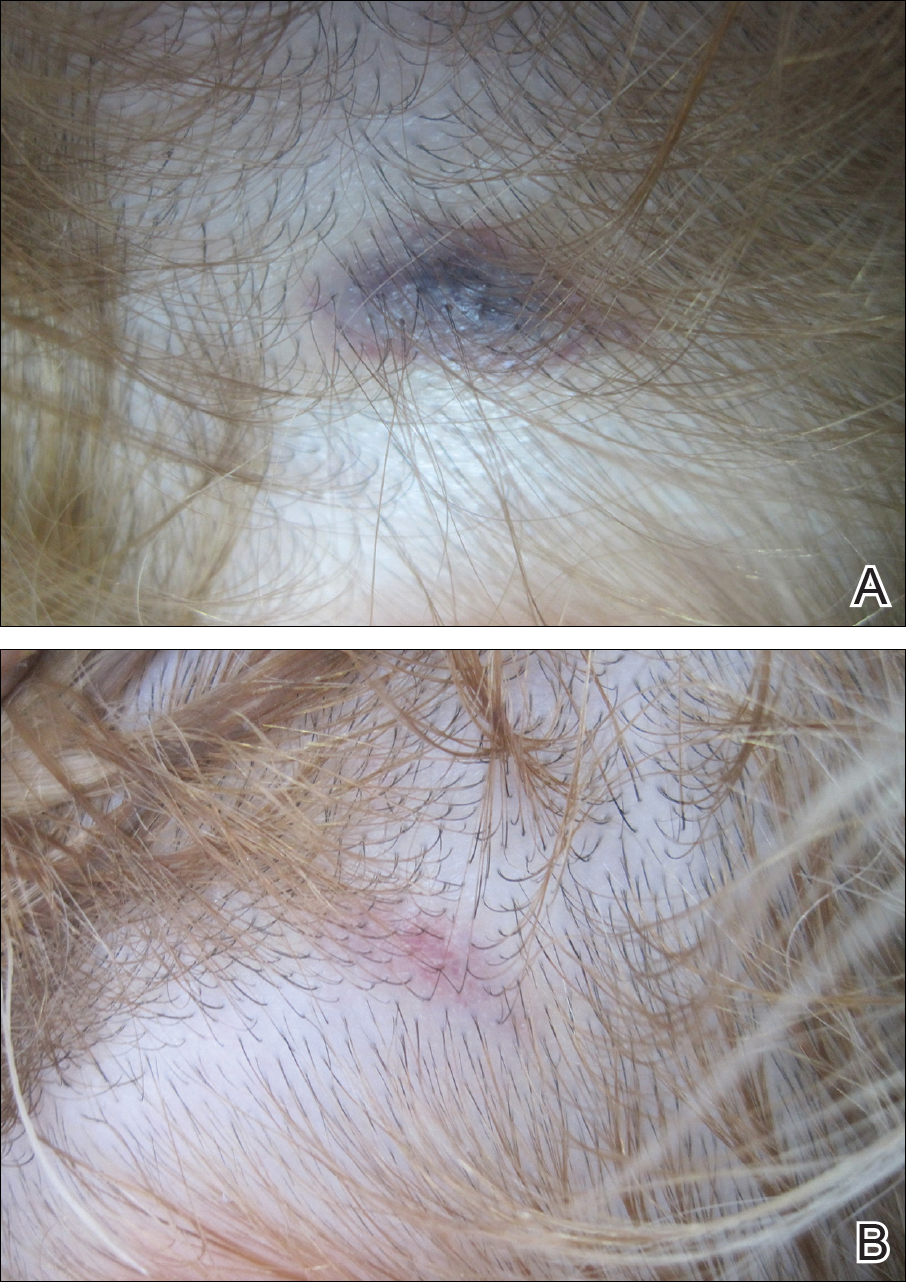

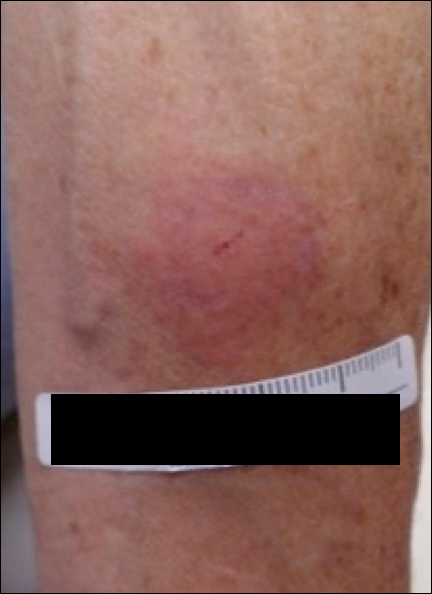

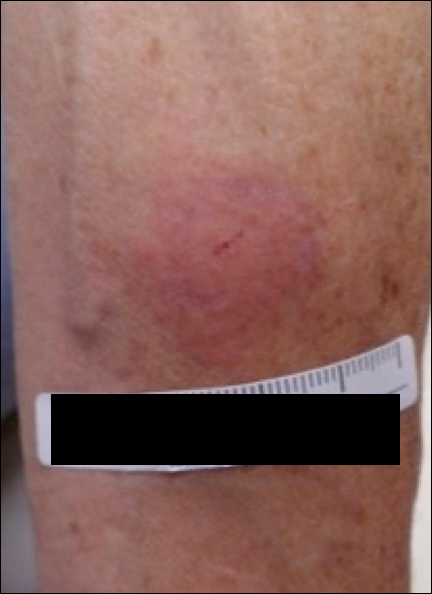

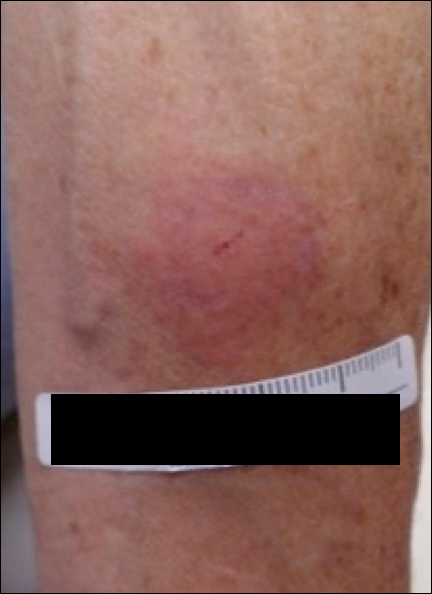

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

To the Editor:

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

To the Editor:

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the second half of the menstrual cycle.

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is thought to be an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.

- This condition should be considered in female patients with recurrent skin lesions related to their menstrual cycle.

Acute Localized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Flurbiprofen

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

Practice Points

- Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis but typically localized in a single area.

- The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative, could be a rare causative agent of this disease.

Contact Allergy to Poliglecaprone 25 Sutures

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman who had a tattoo on the right wrist surgically removed 2 days prior developed severe erythema and swelling at the incision site (Figure 1). Exposure at the incision site was limited to bacitracin, poliglecaprone 25 suture, and plain cotton gauze. Patch testing of bacitracin was performed, which was ++ (moderately positive reaction) at the 96-hour reading, indicating that part of the reaction was due to the topical antibiotic. Testing of the suture was performed by tying the suture to the skin of the forearm and removing it at 48 hours. There was a ++ reaction to the suture prior to removal at 48 hours, which increased to +++ (severely positive reaction) after suture removal at 96 hours (Figure 2). Therefore, it appears that allergy to the suture also was partially responsible for the postsurgical reaction.

Poliglecaprone 25 suture is a monofilament synthetic absorbable material that is a copolymer of glycolide and ε-caprolactone. One case report of oral contact allergy to this suture material resulted in failure of an oral graft; however, no testing was performed to verify the contact allergy.1 Caprolactam ([CH2]5C[O]NH) is a related chemical that can be synthesized by treating caprolactone ([CH2]5CO2) with ammonia at elevated temperatures.2 Contact allergy has been reported to polyamide 6 suture, which is obtained by polymerizing ε-caprolactam. This report stated that contact allergy to ε-caprolactam also has been reported occupationally during manufacture and from its use in fishing nets, socks, gloves, and stockings.3

The package insert for the poliglecaprone 25 suture states that the material is “nonantigenic, nonpyrogenic and elicits only a slight tissue reaction during absorption.”4 We present a case of contact allergy to poliglecaprone 25 suture that was confirmed by allergy testing.

- Mawardi H. Oral contact allergy to suture material results in connective tissue graft failure: a case report. J Periodontol Online. 2014;4:155-160.

- Buntara T, Noel S, Phua PH, et al. Caprolactam from renewable resources: catalytic conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into caprolactone. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:7083-7087.

- Hausen BM. Allergic contact dermatitis from colored surgical suture material: contact allergy to epsilon-caprolactam and acid blue 158. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:174-175.

- Monocryl [package insert]. Somerville, NJ: Ethicon, Inc; 1996.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman who had a tattoo on the right wrist surgically removed 2 days prior developed severe erythema and swelling at the incision site (Figure 1). Exposure at the incision site was limited to bacitracin, poliglecaprone 25 suture, and plain cotton gauze. Patch testing of bacitracin was performed, which was ++ (moderately positive reaction) at the 96-hour reading, indicating that part of the reaction was due to the topical antibiotic. Testing of the suture was performed by tying the suture to the skin of the forearm and removing it at 48 hours. There was a ++ reaction to the suture prior to removal at 48 hours, which increased to +++ (severely positive reaction) after suture removal at 96 hours (Figure 2). Therefore, it appears that allergy to the suture also was partially responsible for the postsurgical reaction.

Poliglecaprone 25 suture is a monofilament synthetic absorbable material that is a copolymer of glycolide and ε-caprolactone. One case report of oral contact allergy to this suture material resulted in failure of an oral graft; however, no testing was performed to verify the contact allergy.1 Caprolactam ([CH2]5C[O]NH) is a related chemical that can be synthesized by treating caprolactone ([CH2]5CO2) with ammonia at elevated temperatures.2 Contact allergy has been reported to polyamide 6 suture, which is obtained by polymerizing ε-caprolactam. This report stated that contact allergy to ε-caprolactam also has been reported occupationally during manufacture and from its use in fishing nets, socks, gloves, and stockings.3

The package insert for the poliglecaprone 25 suture states that the material is “nonantigenic, nonpyrogenic and elicits only a slight tissue reaction during absorption.”4 We present a case of contact allergy to poliglecaprone 25 suture that was confirmed by allergy testing.

To the Editor:

A 42-year-old woman who had a tattoo on the right wrist surgically removed 2 days prior developed severe erythema and swelling at the incision site (Figure 1). Exposure at the incision site was limited to bacitracin, poliglecaprone 25 suture, and plain cotton gauze. Patch testing of bacitracin was performed, which was ++ (moderately positive reaction) at the 96-hour reading, indicating that part of the reaction was due to the topical antibiotic. Testing of the suture was performed by tying the suture to the skin of the forearm and removing it at 48 hours. There was a ++ reaction to the suture prior to removal at 48 hours, which increased to +++ (severely positive reaction) after suture removal at 96 hours (Figure 2). Therefore, it appears that allergy to the suture also was partially responsible for the postsurgical reaction.

Poliglecaprone 25 suture is a monofilament synthetic absorbable material that is a copolymer of glycolide and ε-caprolactone. One case report of oral contact allergy to this suture material resulted in failure of an oral graft; however, no testing was performed to verify the contact allergy.1 Caprolactam ([CH2]5C[O]NH) is a related chemical that can be synthesized by treating caprolactone ([CH2]5CO2) with ammonia at elevated temperatures.2 Contact allergy has been reported to polyamide 6 suture, which is obtained by polymerizing ε-caprolactam. This report stated that contact allergy to ε-caprolactam also has been reported occupationally during manufacture and from its use in fishing nets, socks, gloves, and stockings.3

The package insert for the poliglecaprone 25 suture states that the material is “nonantigenic, nonpyrogenic and elicits only a slight tissue reaction during absorption.”4 We present a case of contact allergy to poliglecaprone 25 suture that was confirmed by allergy testing.

- Mawardi H. Oral contact allergy to suture material results in connective tissue graft failure: a case report. J Periodontol Online. 2014;4:155-160.

- Buntara T, Noel S, Phua PH, et al. Caprolactam from renewable resources: catalytic conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into caprolactone. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:7083-7087.

- Hausen BM. Allergic contact dermatitis from colored surgical suture material: contact allergy to epsilon-caprolactam and acid blue 158. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:174-175.

- Monocryl [package insert]. Somerville, NJ: Ethicon, Inc; 1996.

- Mawardi H. Oral contact allergy to suture material results in connective tissue graft failure: a case report. J Periodontol Online. 2014;4:155-160.

- Buntara T, Noel S, Phua PH, et al. Caprolactam from renewable resources: catalytic conversion of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into caprolactone. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:7083-7087.

- Hausen BM. Allergic contact dermatitis from colored surgical suture material: contact allergy to epsilon-caprolactam and acid blue 158. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:174-175.

- Monocryl [package insert]. Somerville, NJ: Ethicon, Inc; 1996.

Practice Point

- Physicians should be aware that rare contact reactions can occur with certain types of sutures.

Eruptive Seborrheic Keratoses Secondary to Telaprevir-Related Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

To the Editor:

Telaprevir is a hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease inhibitor used with ribavirin and interferon for the treatment of increased viral load clearance in specific HCV genotypes. We report a case of eruptive seborrheic keratoses (SKs) secondary to telaprevir-related dermatitis.

A 65-year-old woman with a history of depression, basal cell carcinoma, and HCV presented 5 months after initiation of antiviral treatment with interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir. Shortly after initiation of therapy, the patient developed a diffuse itch with a “pricking” sensation. The patient reported that approximately 2 months after starting treatment she developed an erythematous scaling rash that covered 75% of the body, which led to the discontinuation of telaprevir after 10 weeks of therapy; interferon and ribavirin were continued for a total of 6 months. In concert with the eczematous eruption, the patient noticed many new hyperpigmented lesions with enlargement of the few preexisting SKs. She presented to our clinic 6 weeks after the discontinuation of telaprevir for evaluation of these lesions.

On examination, several brown, hyperpigmented, stuck-on papules and plaques were noted diffusely on the body, most prominently along the frontal hairline (Figure 1). A biopsy of the right side of the forehead showed a reticulated epidermis, horn pseudocysts, and increased basilar pigment diagnostic of an SK (Figure 2).

[[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]][[{"attributes":{},"fields":{}}]]

Telaprevir is an HCV protease inhibitor that is given in combination with interferon and ribavirin for increased clearance of genotype 1 HCV infection. Cutaneous reactions to telaprevir are seen in 41% to 61% of treated patients and include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, sarcoidosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris–like drug eruption, and most commonly telaprevir-related dermatitis.1-3 Telaprevir-related dermatitis accounts for up to 95% of cutaneous reactions and presents at a median of 15 days (interquartile range, 4–41 days) after initiation of therapy. Nearly 25% of cases occur in the first 4 days and 46% of cases occur within 4 weeks. It presents as an erythematous eczematous dermatitis commonly associated with pruritus in contrast to the common morbilliform drug eruption. Secondary xerosis, excoriation, and lichenification can be appreciated. With appropriate treatment, resolution occurs in a median of 44 days.1 Treatment of the dermatitis can allow completion of the recommended 12-week course of telaprevir and involves oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and discontinuation of telaprevir. If the cutaneous eruption does not resolve, discontinuation of ribavirin also may be required, as it can cause a similar cutaneous eruption.4

Eruptive SKs may be appreciated in 2 clinical circumstances: associated with an internal malignancy (Leser-Trélat sign), or secondary to an erythrodermic eruption. Flugman et al5 reported 2 cases of eruptive SKs in association with erythroderma. Their first patient developed erythroderma after initiating UVB therapy for psoriasis. The second patient developed an erythrodermic drug hypersensitivity reaction after switching to generic forms of quinidine gluconate and ranitidine. The SKs spontaneously resolved within 6 months and 10 weeks of the resolution of erythroderma, respectively.5 Most of our patient’s eruptive SKs resolved within a few months of their presentation, consistent with the time frame reported in the literature.

Telaprevir-related dermatitis presumably served as the inciting factor for the development of SKs in our patient, as the lesions improved after discontinuation of telaprevir despite continued therapy with ribavirin. As noted by Flugman et al,5 SKs may be seen in erythroderma due to diverse etiologies such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or allergic contact dermatitis. We hypothesize that the eruption immunologically releases cytokines and/or growth factors that stimulate the production of the SKs. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 mutations have been associated with SKs.6 An erythrodermic milieu may incite such mutations in genetically predisposed patients.

We present a case of eruptive SKs related to telaprevir therapy. Our report expands the clinical scenarios in which the clinician can observe eruptive SKs. Although further research is necessary to ascertain the pathogenesis of these lesions, patients may be reassured that most lesions will spontaneously resolve.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

- Roujeau J, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan S, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- Stalling S, Vu J, English J. Telaprevir-induced pityriasis rubra pilaris-like drug eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1215-1217.

- Hinds B, Sonnier G, Waldman M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis triggered by immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB47.

- Lawitz E. Diagnosis and management of telaprevir-associated rash. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:469-471.

- Flugman SL, McClain SA, Clark RA. Transient eruptive seborrheic keratoses associated with erythrodermic psoriasis and erythrodermic drug eruption: report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(6 suppl):S212-S214.

- Hafner C, Hartman A, van Oers JM, et al. FGFR3 mutations in seborrheic keratoses are already present in flat lesions and associated with age and localization. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:895-903.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous reactions presenting as eczematous dermatitis are common (41%–61%) during telaprevir treatment.

- Telaprevir-related dermatitis can lead to eruptive seborrheic keratoses that may spontaneously resolve.

Zika Understanding Unfolds