User login

Nasal Tanning Sprays: Illuminating the Risks of a Popular TikTok Trend

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

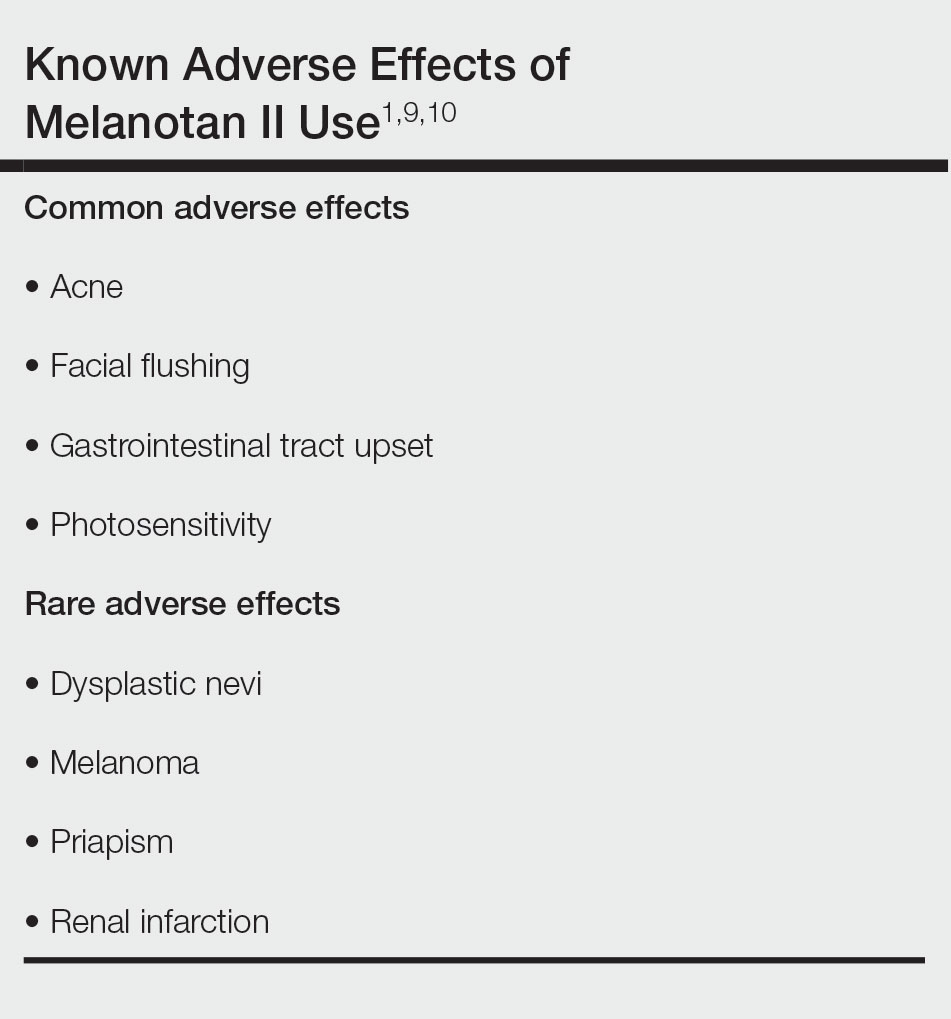

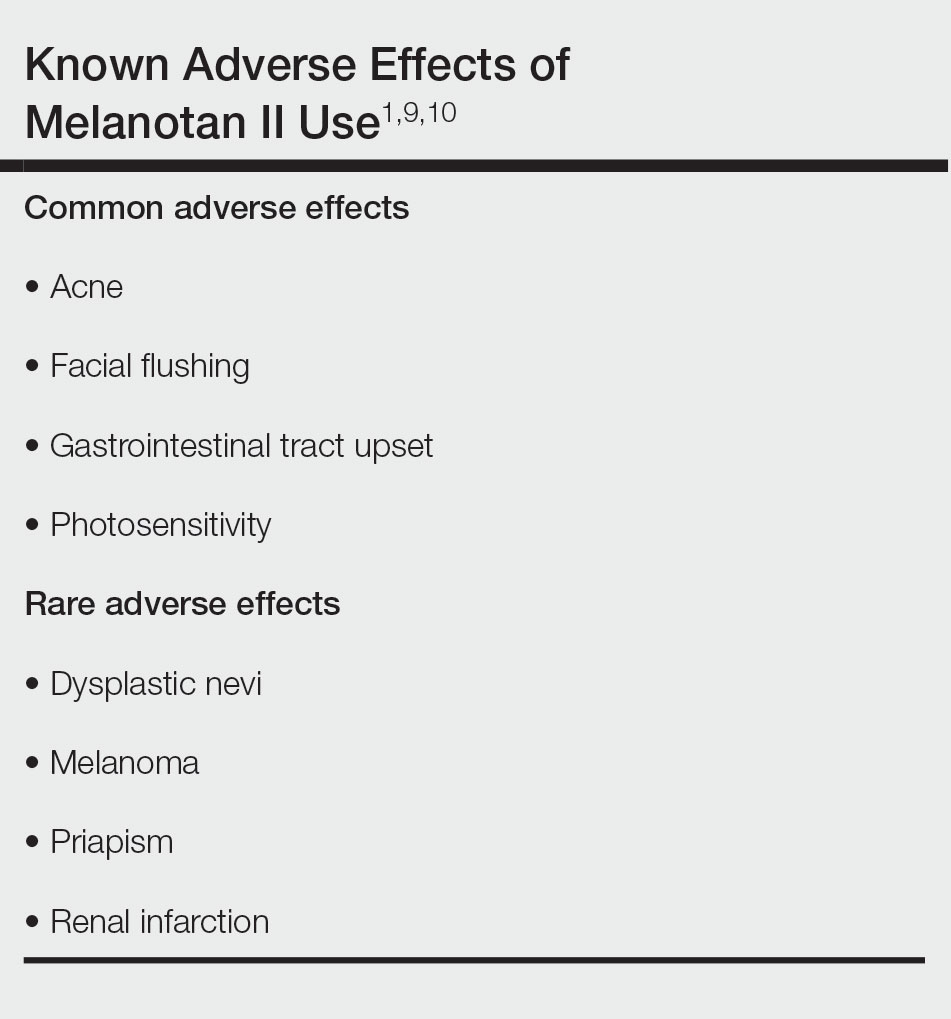

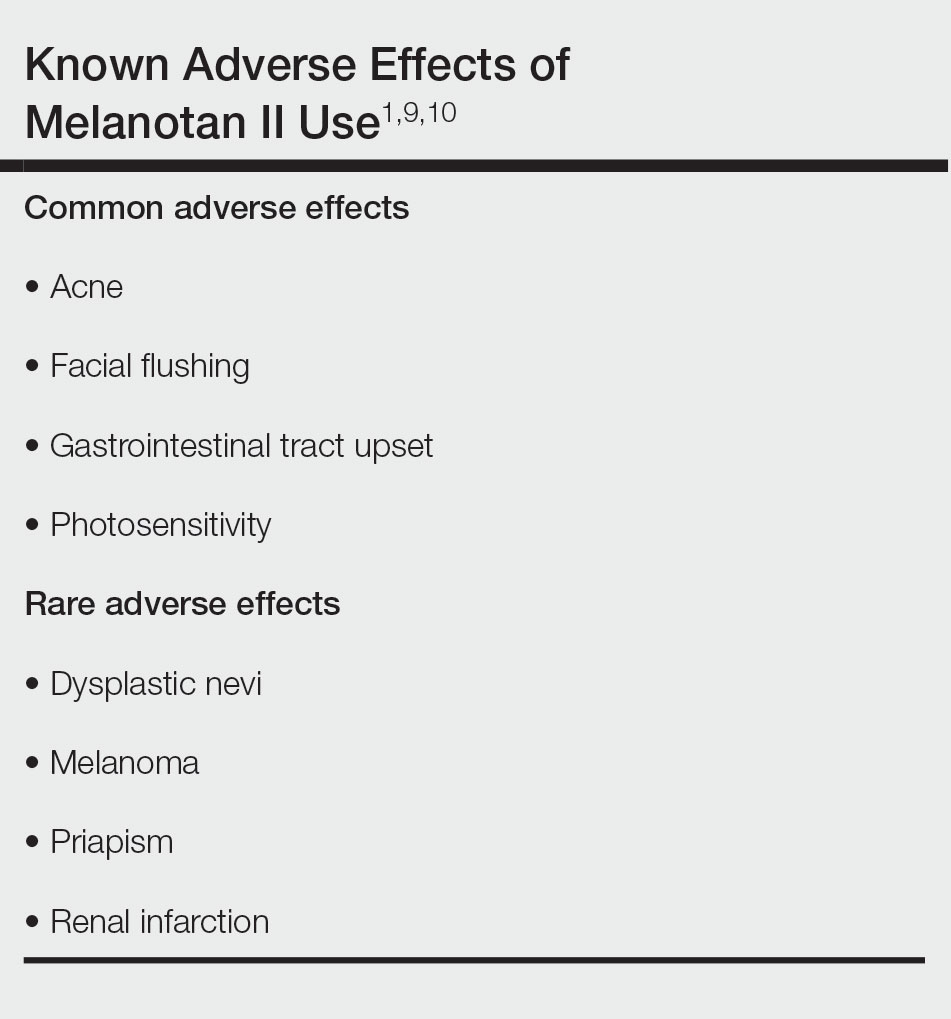

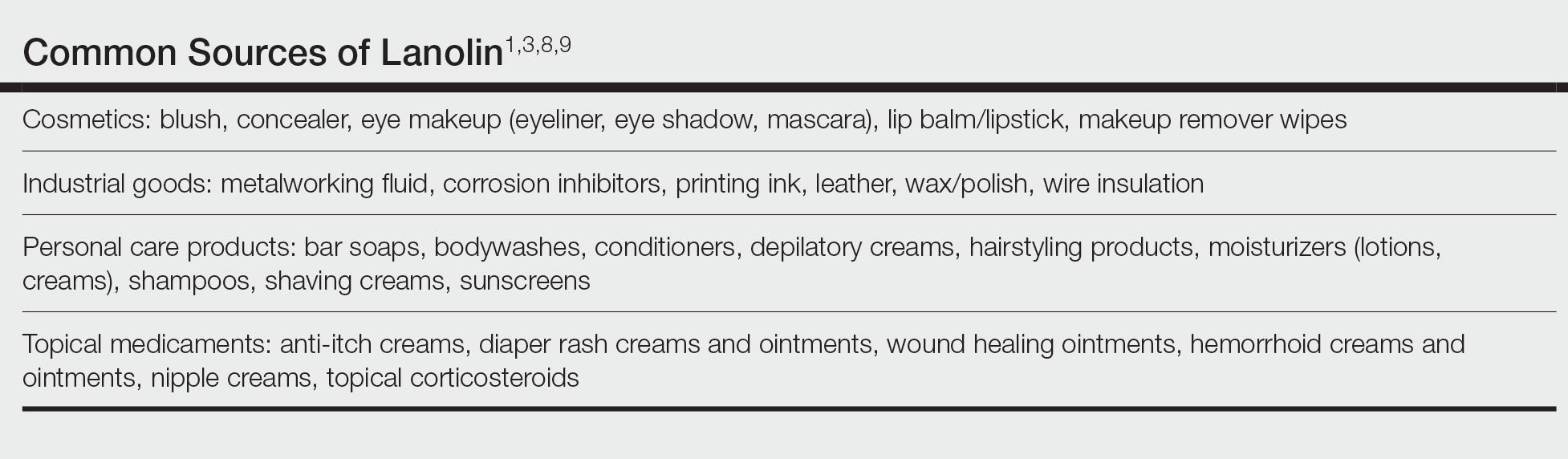

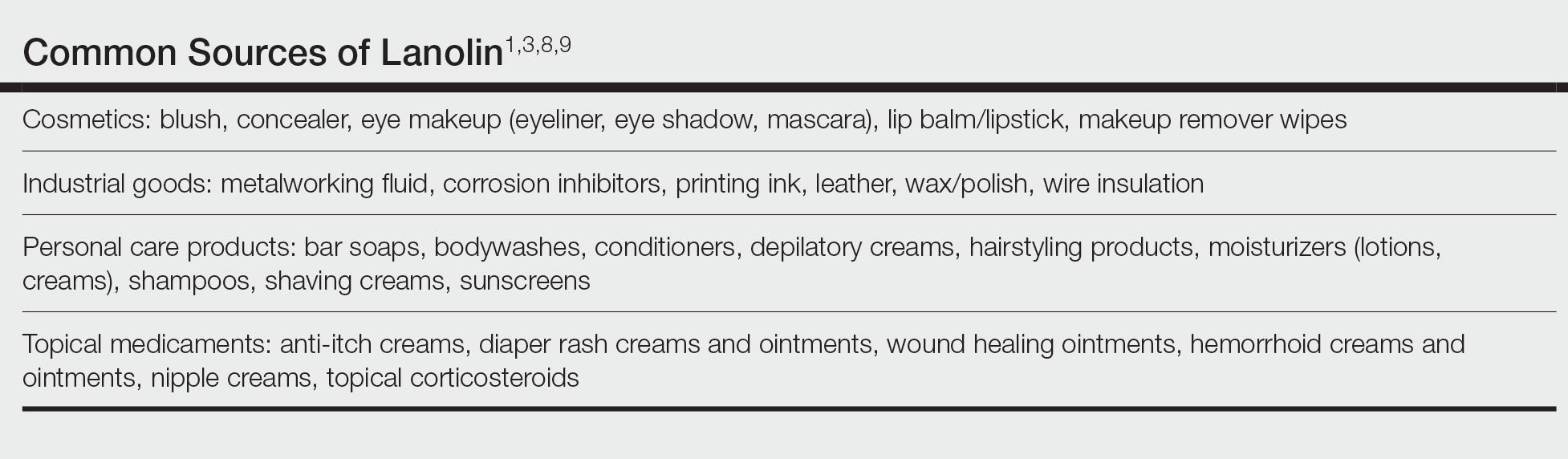

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

PRACTICE POINTS

- Although tanning beds are arguably the most common and dangerous method used by patients to tan their skin, dermatologists should be aware of the other means by which patients may artificially increase skin pigmentation and the risks imposed by undertaking such practices.

- We challenge dermatologists to note the influence of social media on tanning trends and consider creating a platform on these mediums to combat misinformation and promote sun safety and skin health.

- We encourage dermatologists to diligently stay informed about the popular societal trends related to the skin such as the use of nasal tanning products (eg, melanotan I and II) and be proactive in discussing their risks with patients as deemed appropriate.

Tackling Acrylate Allergy: The Sticky Truth

Acrylates are a ubiquitous family of synthetic thermoplastic resins that are employed in a wide array of products. Since the discovery of acrylic acid in 1843 and its industrialization in the early 20th century, acrylates have been used by many different sectors of industry.1 Today, acrylates can be found in diverse sources such as adhesives, coatings, electronics, nail cosmetics, dental materials, and medical devices. Although these versatile compounds have revolutionized numerous sectors, their potential to trigger allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) has garnered considerable attention in recent years. In 2012, acrylates as a group were named Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society,2 and one member—isobornyl acrylate—also was given the infamous award in 2020.3 In this article, we highlight the chemistry of acrylates, the growing prevalence of acrylate contact allergy, common sources of exposure, patch testing considerations, and management/prevention strategies.

Chemistry and Uses of Acrylates

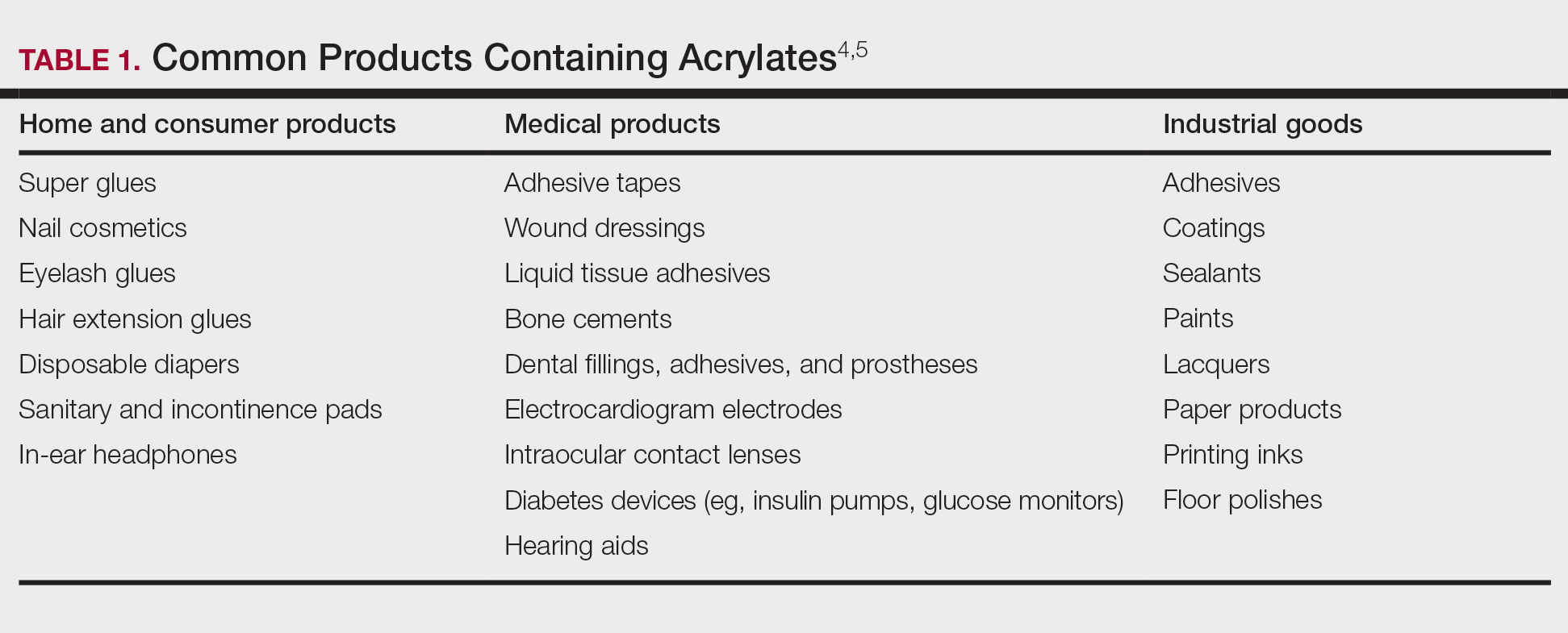

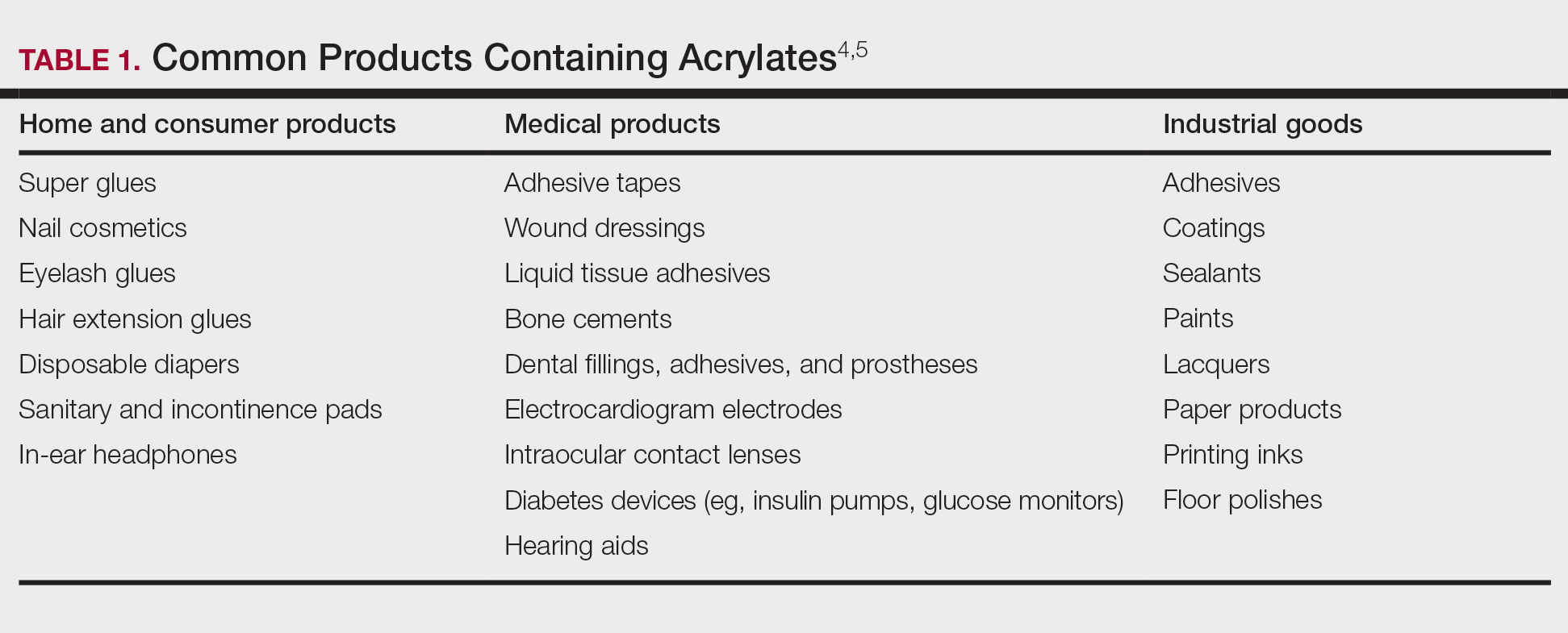

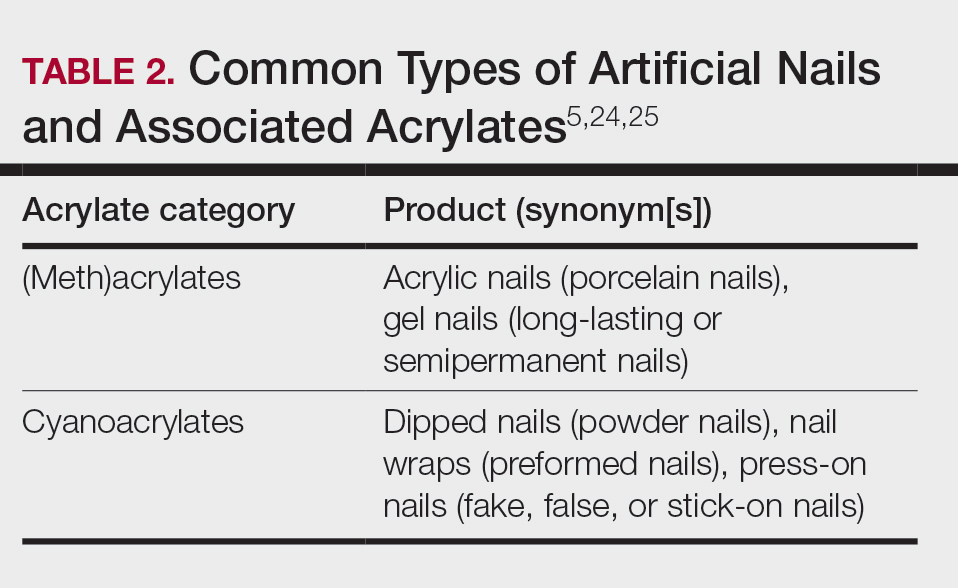

Acrylates are widely used due to their pliable and resilient properties.4 They begin as liquid monomers of (meth)acrylic acid or cyanoacrylic acid that are molded to the desired application before being cured or hardened by one of several means: spontaneously, using chemical catalysts, or with heat, UV light, or a light-emitting diode. Once cured, the final polymers (ie, [meth]acrylates, cyanoacrylates) serve a myriad of different purposes. Table 1 includes some of the more clinically relevant sources of acrylate exposure. Although this list is not comprehensive, it offers a glimpse into the vast array of uses for acrylates.

Acrylate Contact Allergy

Acrylic monomers are potent contact allergens, but the polymerized final products are not considered allergenic, assuming they are completely cured; however, ACD can occur with incomplete curing.6 It is of clinical importance that once an individual becomes sensitized to one type of acrylate, they may develop cross-reactions to others contained in different products. Notably, cyanoacrylates generally do not cross-react with (meth)acrylates; this has important implications for choosing safe alternative products in sensitized patients, though independent sensitization to cyanoacrylates is possible.7,8

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The prevalence of acrylate allergy in the general population is unknown; however, there is a trend of increased patch test positivity in studies of patients referred for patch testing. A 2018 study by the European Environmental Contact Dermatitis Research Group reported positive patch tests to acrylates in 1.1% of 18,228 patients tested from 2013 to 2015.9 More recently, a multicenter European study (2019-2020) reported a 2.3% patch test positivity to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) among 7675 tested individuals,10 and even higher HEMA positivity was reported in Spain (3.7% of 1884 patients in 2019-2020).11 In addition, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported positive patch test reactions to HEMA in 3.2% of 4111 patients tested from 2019 to 2020, a statistically significant increase compared with those tested in 2009 to 2018 (odds ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.03-1.51]; P=.02).12

Historically, acrylate sensitization primarily stemmed from occupational exposure. A retrospective analysis of occupational dermatitis performed by the NACDG (2001-2016) showed that HEMA was among the top 10 most common occupational allergens (3.4% positivity [83/2461]) and had the fifth highest percentage of occupationally relevant reactions (73.5% [83/113]).13 High-risk occupations include dental providers and nail technicians. Dentistry utilizes many materials containing acrylates, including uncured plastic resins used in dental prostheses, dentin bonding materials, and glass ionomers.14 A retrospective analysis of 585 dental personnel who were patch tested by the NACDG (2001-2018) found that more than 20% of occupational ACD cases were related to acrylates.15 Nail technicians are another group routinely exposed to acrylates through a variety of modern nail cosmetics. In a 7-year study from Portugal evaluating acrylate ACD, 68% (25/37) of cases were attributed to occupation, 80% (20/25) of which were in nail technicians.16 Likewise, among 28 nail technicians in Sweden who were referred for patch testing, 57% (16/28) tested positive for at least 1 acrylate.17

Modern Sources of Acrylate Exposure

Once thought to be a predominantly occupational exposure, acrylates have rapidly made their way into everyday consumer products. Clinicians should be aware of several sources of clinically relevant acrylate exposure, including nail cosmetics, consumer electronics, and medical/surgical adhesives.

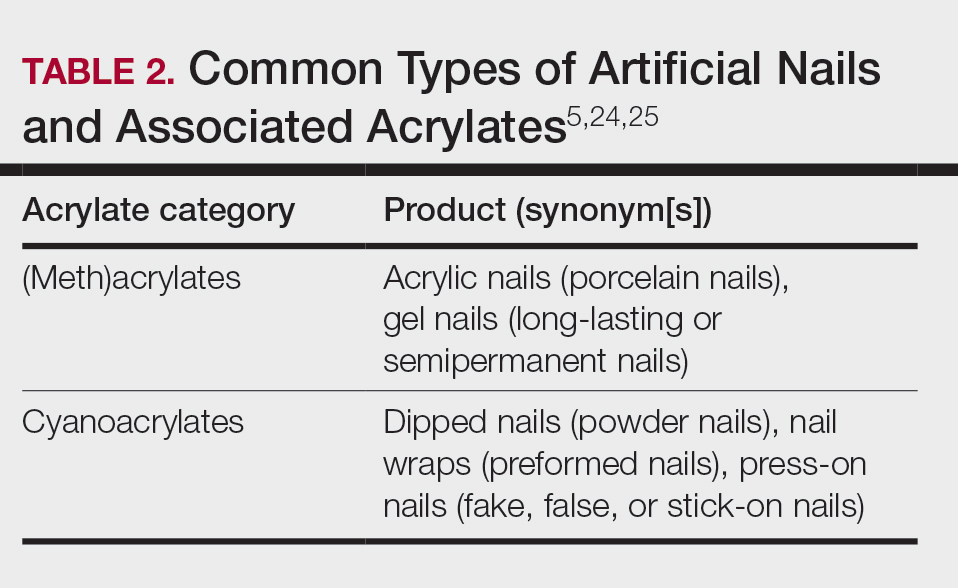

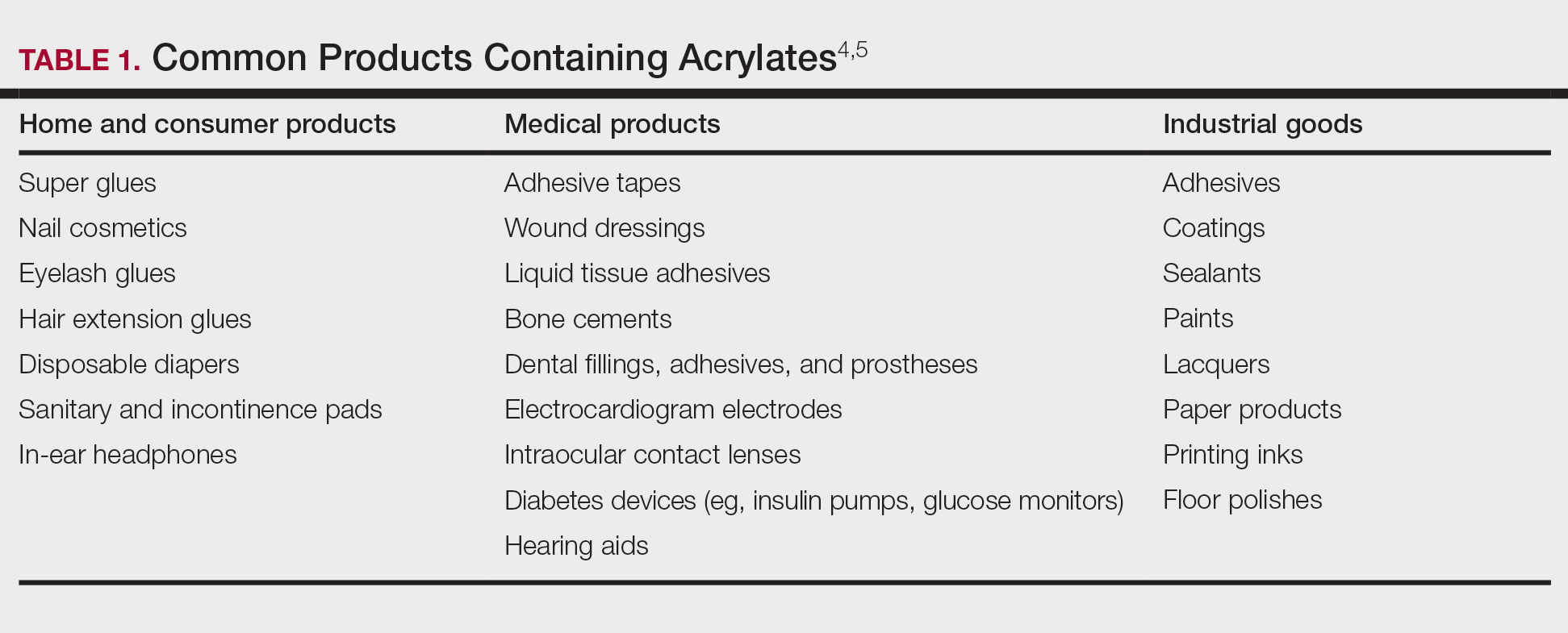

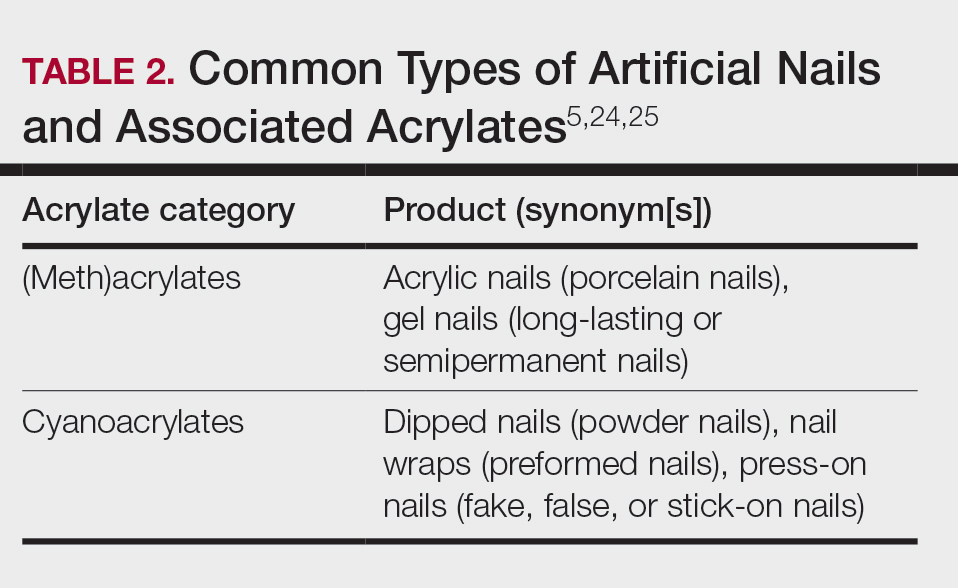

A 2016 study found a shift to nail cosmetics as the most common source of acrylate sensitization.18 Nail cosmetics that contain acrylates include traditional acrylic, gel (shellac), dipped, and press-on (false) nails.19 The NACDG found that the most common allergen in patients experiencing ACD associated with nail products (2001-2016) was HEMA (56.6% [273/482]), far ahead of the traditional nail polish allergen tosylamide (36.2% [273/755]). Over the study period, the frequency of positive patch tests statistically increased for HEMA (P=.0069) and decreased for tosylamide (P<.0001).20 There is concern that the use of home gel nail kits, which can be purchased online at the click of a button, may be associated with a risk for acrylate sensitization.21,22 A recent study surveyed a Facebook support group for individuals with self-reported reactions to nail cosmetics, finding that 78% of the 199 individuals had used at-home gel nail kits, and more than 80% of them first developed skin reactions after starting to use at-home kits.23 The risks for sensitization are thought to be greater when self-applying nail acrylates compared to having them done professionally because individuals are more likely to spill allergenic monomers onto the skin at home; it also is possible that home techniques could lead to incomplete curing. Table 2 reviews the different types of acrylic nail cosmetics.

Medical adhesives and equipment are other important areas where acrylates can be encountered in abundance. A review by Spencer et al18 cautioned wound dressings as an up-and-coming source of sensitization, and this has been demonstrated in the literature as coming to fruition.26 Another study identified acrylates in 15 of 16 (94%) tested medical adhesives; among 7 medical adhesives labeled as hypoallergenic, 100% still contained acrylates and/or abietic acid.27 Multiple case reports have described ACD to adhesives of electrocardiogram electrodes containing acrylates.28-31 Physicians providing care to patients with diabetes mellitus also must be aware of acrylates in glucose monitors and insulin pumps, either found in the adhesives or leaching from the inside of the device to reach the skin.32 Isobornyl acrylate in particular has made quite the name for itself in this sector, being crowned the 2020 Allergen of the Year owing to its key role in cases of ACD to diabetes devices.3

Cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives (eg, 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate) are now well documented to cause postoperative ACD.33,34 Although robust prospective data are limited, studies suggest that 2% to 14% of patients develop postoperative skin reactions following 2-octyl cyanoacrylate application.35-37 It has been shown that sensitization to tissue adhesives often occurs after the first application, followed by an eruption of ACD as long as a month later, which can create confusion about the nature of the rash for patients and health care providers alike, who may for instance attribute it to infection rather than allergy.38 In the orthopedic literature, a woman with a known history of acrylic nail ACD had knee arthroplasty failure attributed to acrylic bone cement with resolution of the joint symptoms after changing to a cementless device.39

Awareness of the common use of acrylates is important to identify the cause of reactions from products that would otherwise seem nonallergenic. A case of occupational ACD to isobornyl acrylate in UV-cured phone screen protectors has been reported40; several cases of ACD to acrylates in headphones41,42 as well as one related to a wearable fitness device also have been reported.43 Given all these possible sources of exposure, ACD to acrylates should be on your radar.

When to Consider Acrylate ACD

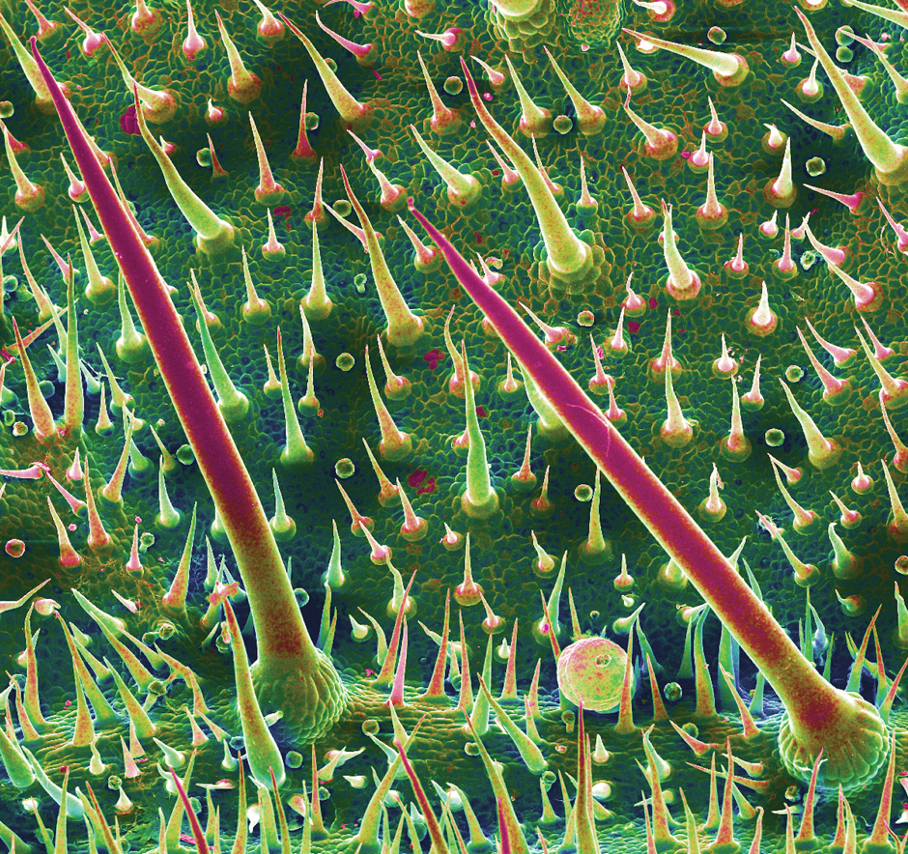

When working up a patient with dermatitis, it is essential to ask about occupational history and hobbies to get a sense of potential contact allergen exposures. The typical presentation of occupational acrylate-associated ACD is hand eczema, specifically involving the fingertips.5,24,25,44 Acrylate ACD should be considered in patients with nail dystrophy and a history of wearing acrylic nails.45 There can even be involvement of the face and eyelids secondary to airborne contact or ectopic spread from the hands.24 Spreading vesicular eruptions associated with adhesives also should raise concern. The Figure depicts several possible presentations of ACD to acrylates. In a time of abundant access to products containing acrylates, dermatologists should consider this allergy in their differential diagnosis and consider patch testing.

Patch Testing to Acrylates

The gold standard for ACD diagnosis is patch testing. It should be noted that no acrylates are included in the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test series. Several acrylates are tested in expanded patch test series including the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen series and North American 80 Comprehensive Series. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate is thought to be the most important screening allergen to test. Ramos et al16 reported a positive patch test to HEMA in 81% (30/37) of patients who had any type of acrylate allergy.

If initial testing to a limited number of acrylates is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, expanded acrylates/plastics and glue series also are available from commercial patch test suppliers. Testing to an expanded panel of acrylates is especially pertinent to consider in suspected occupational cases given the risk of workplace absenteeism and even disability that come with continued exposure to the allergen. Of note, isobornyl acrylate is not included in the baseline patch test series and must be tested separately, particularly because it usually does not cross-react with other acrylates, and therefore allergy could be missed if not tested on its own.

Acrylates are volatile substances that have been shown to degrade at room temperature and to a lesser degree when refrigerated. Ideally, they should be stored in a freezer and not used beyond their expiration date. Furthermore, it is advised that acrylate patch tests be prepared immediately prior to placement on the patient and to discard the initial extrusion from the syringe, as the concentration at the tip may be decreased.46,47

With regard to tissue adhesives, the actual product should be tested as-is because these are not commercially available patch test substances.48 Occasionally, patients who are sensitized to the tissue adhesive will not react when patch tested on intact skin. If clinical suspicion remains high, scratch patch testing may confirm contact allergy in cases of negative testing on intact skin.49

Management and Prevention

Once a diagnosis of ACD secondary to acrylates has been established, counseling patients on allergen avoidance strategies is essential. For (meth)acrylate-allergic patients who want to continue using modern nail products, cyanoacrylate-based options (eg, dipped, press-on nails) can be considered as an alternative, as they do not cross-react, though independent sensitization is still possible. However, traditional nail polish is the safest option to recommend.

The concern with acrylate sensitization extends beyond the immediate issue that brought the patient into your clinic. Dermatologists must counsel patients who are sensitized to acrylates on the possible sequelae of acrylate-containing dental or orthopedic procedures. Oral lichenoid lesions, denture stomatitis, burning mouth syndrome, or even acute facial swelling have been reported following dental work in patients with acrylate allergy.50-53 Dentists of patients with acrylate ACD should be informed of the diagnosis so acrylates can be avoided during dental work; if unavoidable, all possible steps should be taken to ensure complete curing of the monomers. In the surgical setting, patients sensitized to cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives should be offered wound closure alternatives such as sutures or staples.34

In patients with diabetes mellitus who develop ACD to their glucose monitor or insulin pump, ideally they should be switched to a device that does not contain acrylates. Problematically, these devices are constantly being reformulated, and manufacturers do not always divulge their components, which can make it challenging to determine safe alternative options.32,54 Various barrier products may help on a case-by-case basis.55Preventative measures should be implemented in workplaces that utilize acrylates, including dental practices and nail salons. Acrylic monomers have been shown to penetrate most gloves within minutes of exposure.56,57 Double gloving with nitrile gloves affords some protection for no longer than 60 minutes.6 4H gloves have been shown to provide true protection but result in a loss of dexterity.58 The fingerstall technique involves removing the fingers from a 4H glove, inserting them on the fingers, and applying a more flexible glove on top to hold them in place; this offers a hybrid between protection and finger dexterity.59

Final Interpretation

In a world characterized by technological advancements and increasing accessibility to acrylate-containing products, we hope this brief review serves as a resource and reminder to dermatologists to consider acrylates as a potential cause of ACD with diverse presentations and important future implications for affected individuals. The rising trend of acrylate allergy necessitates comprehensive assessment and shared decision-making between physicians and patients. As we navigate the ever-changing landscape of materials and technologies, clinicians must remain vigilant to avoid some potentially sticky situations for patients.

- Staehle HJ, Sekundo C. The origins of acrylates and adhesive technologies in dentistry. J Adhes Dent. 2021;23:397-406.

- Militello M, Hu S, Laughter M, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergens of the Year 2000 to 2020. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:309-320.

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Ajekwene KK. Properties and applications of acrylates. In: Serrano-Aroca A, Deb S, eds. Acrylate Polymers for Advanced Applications. IntechOpen; 2020:35-46. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89867

- Voller LM, Warshaw EM. Acrylates: new sources and new allergens. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:277-283.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2012;23:6-16.

- Gardeen S, Hylwa S. A review of acrylates: super glue, nail adhesives, and diabetic pump adhesives increasing sensitization risk in women and children. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:263-267.

- Chou M, Dhingra N, Strugar TL. Contact sensitization to allergens in nail cosmetics. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2017;28:231-240.

- Gonçalo M, Pinho A, Agner T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by nail acrylates in Europe. an EECDRG study. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:254-260.

- Uter W, Wilkinson SM, Aerts O, et al. Patch test results with the European baseline series, 2019/20-Joint European results of the ESSCA and the EBS working groups of the ESCD, and the GEIDAC. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:343-355.

- Hernández-Fernández CP, Mercader-García P, Silvestre Salvador JF, et al. Candidate allergens for inclusion in the Spanish standard series based on data from the Spanish Contact Dermatitis Registry. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:798-805.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2023;34:90-104.

- DeKoven JG, DeKoven BM, Warshaw EM, et al. Occupational contact dermatitis: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2001 to 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:782-790.

- Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Schubert S, et al. Contact sensitization in dental technicians with occupational contact dermatitis. data of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) 2001-2015. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:266-273.

- Warshaw EM, Ruggiero JL, Atwater AR, et al. Occupational contact dermatitis in dental personnel: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2001 to 2018. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2022;33:80-90.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Gonçalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates—a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Fisch A, Hamnerius N, Isaksson M. Dermatitis and occupational (meth)acrylate contact allergy in nail technicians—a 10-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:58-60.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

- DeKoven S, DeKoven J, Holness DL. (Meth)acrylate occupational contact dermatitis in nail salon workers: a case series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:340-344.

- Warshaw EM, Voller LM, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with nail care products: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2016. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:191-201.

- Le Q, Cahill J, Palmer-Le A, et al. The rising trend in allergic contact dermatitis to acrylic nail products. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:221-223.

- Gatica-Ortega ME, Pastor-Nieto M. The present and future burden of contact dermatitis from acrylates in manicure. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2020;7:1-21.

- Guenther J, Norman T, Wee C, et al. A survey of skin reactions associated with acrylic nail cosmetics, with a focus on home kits: is there a need for regulation [published online October 16, 2023]? Dermatitis. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0204

- Calado R, Gomes T, Matos A, et al. Contact dermatitis to nail cosmetics. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10:173-181.

- Draelos ZD. Nail cosmetics and adornment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:351-359.

- Mestach L, Huygens S, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylic-based medical dressings and adhesives. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:81-84.

- Tam I, Wang JX, Yu JD. Identifying acrylates in medical adhesives. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E40-E42.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Ozkaya E, Kavlak Bozkurt P. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by self-adhesive electrocardiography electrodes: a rare case with concomitant roles of nickel and acrylates. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:121-123.

- Lyons G, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to methacrylates in ECG electrode dots. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:39-40.

- Jelen G. Acrylate, a hidden allergen of electrocardiogram electrodes. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:315-316.

- Bembry R, Brys AK, Atwater AR. Medical device contact allergy: glucose monitors and insulin pumps. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2022;11:13-20.

- Liu T, Wan J, McKenna RA, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by Dermabond in a paediatric patient undergoing skin surgery. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:61-62.

- Ricciardo BM, Nixon RL, Tam MM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond Prineo after elective orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2020;43:E515-E522.

- Nigro LC, Parkerson J, Nunley J, et al. Should we stick with surgical glues? the incidence of dermatitis after 2-octyl cyanoacrylate exposure in 102 consecutive breast cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:32-37.

- Alotaibi NN, Ahmad T, Rabah SM, et al. Type IV hypersensitivity reaction to Dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) in plastic surgical patients: a retrospective study. Plast Surg Oakv Ont. 2022;30:222-226.

- Durando D, Porubsky C, Winter S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) after total knee arthroplasty. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2014;25:99-100.

- Asai C, Inomata N, Sato M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis due to the liquid skin adhesive Dermabond® predominantly occurs after the first exposure. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:103-108.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S123-S124.

- Amat-Samaranch V, Garcia-Melendo C, Tubau C, et al. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis to isobornyl acrylate present in cell phone screen protectors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:352-354.

- Chan J, Rabi S, Adler BL. Allergic contact dermatitis to (meth)acrylates in Apple AirPods headphones. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E111-E112.

- Shaver RL, Buonomo M, Scherman JA, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates in Apple AirPods Pro® headphones: a case series. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E459-E461.

- Winston FK, Yan AC. Wearable health device dermatitis: a case of acrylate-related contact allergy. Cutis. 2017;100:97-99.

- Kucharczyk M, Słowik-Rylska M, Cyran-Stemplewska S, et al. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:555-560.

- Nanda S. Nail salon safety: from nail dystrophy to acrylate contact allergies. Cutis. 2022;110:E32-E33.

- Joy NM, Rice KR, Atwater AR. Stability of patch test allergens. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2013;24:227-236.

- Jou PC, Siegel PD, Warshaw EM. Vapor pressure and predicted stability of American Contact Dermatitis Society core allergens. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2016;27:193-201.

- Cook KA, White AA, Shaw DW. Patch testing ingredients of Dermabond and other cyanoacrylate-containing adhesives. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2019;30:314-322.

- Patel K, Nixon R. Scratch patch testing to Dermabond in a patient with suspected allergic contact dermatitis. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2023;34:250-251.

- Ditrichova D, Kapralova S, Tichy M, et al. Oral lichenoid lesions and allergy to dental materials. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czechoslov. 2007;151:333-339.

- Chen AYY, Zirwas MJ. Denture stomatitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:92-94.

- Marino R, Capaccio P, Pignataro L, et al. Burning mouth syndrome: the role of contact hypersensitivity. Oral Dis. 2009;15:255-258.

- Obayashi N, Shintani T, Kamegashira A, et al. A case report of allergic reaction with acute facial swelling: a rare complication of dental acrylic resin. J Int Med Res. 2023;51:3000605231187819.

- Cameli N, Silvestri M, Mariano M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis, an important skin reaction in diabetes device users: a systematic review. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 20221;33:110-115.

- Ng KL, Nixon RL, Grills C, et al. Solution using Stomahesive® wafers for allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in glucose monitoring sensors. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:E56-E59.

- Lönnroth EC, Wellendorf H, Ruyter E. Permeability of different types of medical protective gloves to acrylic monomers. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:440-446.

- Sananez A, Sanchez A, Davis L, et al. Allergic reaction from dental bonding material through nitrile gloves: clinical case study and glove permeability testing. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020;32:371-379.

- Andersson T, Bruze M, Björkner B. In vivo testing of the protection of gloves against acrylates in dentin-bonding systems on patients with known contact allergy to acrylates. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:254-259.

- Roche E, Cuadra J, Alegre V. Sensitization to acrylates caused by artificial acrylic nails: review of 15 cases. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2009;99:788-794.

Acrylates are a ubiquitous family of synthetic thermoplastic resins that are employed in a wide array of products. Since the discovery of acrylic acid in 1843 and its industrialization in the early 20th century, acrylates have been used by many different sectors of industry.1 Today, acrylates can be found in diverse sources such as adhesives, coatings, electronics, nail cosmetics, dental materials, and medical devices. Although these versatile compounds have revolutionized numerous sectors, their potential to trigger allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) has garnered considerable attention in recent years. In 2012, acrylates as a group were named Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society,2 and one member—isobornyl acrylate—also was given the infamous award in 2020.3 In this article, we highlight the chemistry of acrylates, the growing prevalence of acrylate contact allergy, common sources of exposure, patch testing considerations, and management/prevention strategies.

Chemistry and Uses of Acrylates

Acrylates are widely used due to their pliable and resilient properties.4 They begin as liquid monomers of (meth)acrylic acid or cyanoacrylic acid that are molded to the desired application before being cured or hardened by one of several means: spontaneously, using chemical catalysts, or with heat, UV light, or a light-emitting diode. Once cured, the final polymers (ie, [meth]acrylates, cyanoacrylates) serve a myriad of different purposes. Table 1 includes some of the more clinically relevant sources of acrylate exposure. Although this list is not comprehensive, it offers a glimpse into the vast array of uses for acrylates.

Acrylate Contact Allergy

Acrylic monomers are potent contact allergens, but the polymerized final products are not considered allergenic, assuming they are completely cured; however, ACD can occur with incomplete curing.6 It is of clinical importance that once an individual becomes sensitized to one type of acrylate, they may develop cross-reactions to others contained in different products. Notably, cyanoacrylates generally do not cross-react with (meth)acrylates; this has important implications for choosing safe alternative products in sensitized patients, though independent sensitization to cyanoacrylates is possible.7,8

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The prevalence of acrylate allergy in the general population is unknown; however, there is a trend of increased patch test positivity in studies of patients referred for patch testing. A 2018 study by the European Environmental Contact Dermatitis Research Group reported positive patch tests to acrylates in 1.1% of 18,228 patients tested from 2013 to 2015.9 More recently, a multicenter European study (2019-2020) reported a 2.3% patch test positivity to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) among 7675 tested individuals,10 and even higher HEMA positivity was reported in Spain (3.7% of 1884 patients in 2019-2020).11 In addition, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported positive patch test reactions to HEMA in 3.2% of 4111 patients tested from 2019 to 2020, a statistically significant increase compared with those tested in 2009 to 2018 (odds ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.03-1.51]; P=.02).12

Historically, acrylate sensitization primarily stemmed from occupational exposure. A retrospective analysis of occupational dermatitis performed by the NACDG (2001-2016) showed that HEMA was among the top 10 most common occupational allergens (3.4% positivity [83/2461]) and had the fifth highest percentage of occupationally relevant reactions (73.5% [83/113]).13 High-risk occupations include dental providers and nail technicians. Dentistry utilizes many materials containing acrylates, including uncured plastic resins used in dental prostheses, dentin bonding materials, and glass ionomers.14 A retrospective analysis of 585 dental personnel who were patch tested by the NACDG (2001-2018) found that more than 20% of occupational ACD cases were related to acrylates.15 Nail technicians are another group routinely exposed to acrylates through a variety of modern nail cosmetics. In a 7-year study from Portugal evaluating acrylate ACD, 68% (25/37) of cases were attributed to occupation, 80% (20/25) of which were in nail technicians.16 Likewise, among 28 nail technicians in Sweden who were referred for patch testing, 57% (16/28) tested positive for at least 1 acrylate.17

Modern Sources of Acrylate Exposure

Once thought to be a predominantly occupational exposure, acrylates have rapidly made their way into everyday consumer products. Clinicians should be aware of several sources of clinically relevant acrylate exposure, including nail cosmetics, consumer electronics, and medical/surgical adhesives.

A 2016 study found a shift to nail cosmetics as the most common source of acrylate sensitization.18 Nail cosmetics that contain acrylates include traditional acrylic, gel (shellac), dipped, and press-on (false) nails.19 The NACDG found that the most common allergen in patients experiencing ACD associated with nail products (2001-2016) was HEMA (56.6% [273/482]), far ahead of the traditional nail polish allergen tosylamide (36.2% [273/755]). Over the study period, the frequency of positive patch tests statistically increased for HEMA (P=.0069) and decreased for tosylamide (P<.0001).20 There is concern that the use of home gel nail kits, which can be purchased online at the click of a button, may be associated with a risk for acrylate sensitization.21,22 A recent study surveyed a Facebook support group for individuals with self-reported reactions to nail cosmetics, finding that 78% of the 199 individuals had used at-home gel nail kits, and more than 80% of them first developed skin reactions after starting to use at-home kits.23 The risks for sensitization are thought to be greater when self-applying nail acrylates compared to having them done professionally because individuals are more likely to spill allergenic monomers onto the skin at home; it also is possible that home techniques could lead to incomplete curing. Table 2 reviews the different types of acrylic nail cosmetics.

Medical adhesives and equipment are other important areas where acrylates can be encountered in abundance. A review by Spencer et al18 cautioned wound dressings as an up-and-coming source of sensitization, and this has been demonstrated in the literature as coming to fruition.26 Another study identified acrylates in 15 of 16 (94%) tested medical adhesives; among 7 medical adhesives labeled as hypoallergenic, 100% still contained acrylates and/or abietic acid.27 Multiple case reports have described ACD to adhesives of electrocardiogram electrodes containing acrylates.28-31 Physicians providing care to patients with diabetes mellitus also must be aware of acrylates in glucose monitors and insulin pumps, either found in the adhesives or leaching from the inside of the device to reach the skin.32 Isobornyl acrylate in particular has made quite the name for itself in this sector, being crowned the 2020 Allergen of the Year owing to its key role in cases of ACD to diabetes devices.3

Cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives (eg, 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate) are now well documented to cause postoperative ACD.33,34 Although robust prospective data are limited, studies suggest that 2% to 14% of patients develop postoperative skin reactions following 2-octyl cyanoacrylate application.35-37 It has been shown that sensitization to tissue adhesives often occurs after the first application, followed by an eruption of ACD as long as a month later, which can create confusion about the nature of the rash for patients and health care providers alike, who may for instance attribute it to infection rather than allergy.38 In the orthopedic literature, a woman with a known history of acrylic nail ACD had knee arthroplasty failure attributed to acrylic bone cement with resolution of the joint symptoms after changing to a cementless device.39

Awareness of the common use of acrylates is important to identify the cause of reactions from products that would otherwise seem nonallergenic. A case of occupational ACD to isobornyl acrylate in UV-cured phone screen protectors has been reported40; several cases of ACD to acrylates in headphones41,42 as well as one related to a wearable fitness device also have been reported.43 Given all these possible sources of exposure, ACD to acrylates should be on your radar.

When to Consider Acrylate ACD

When working up a patient with dermatitis, it is essential to ask about occupational history and hobbies to get a sense of potential contact allergen exposures. The typical presentation of occupational acrylate-associated ACD is hand eczema, specifically involving the fingertips.5,24,25,44 Acrylate ACD should be considered in patients with nail dystrophy and a history of wearing acrylic nails.45 There can even be involvement of the face and eyelids secondary to airborne contact or ectopic spread from the hands.24 Spreading vesicular eruptions associated with adhesives also should raise concern. The Figure depicts several possible presentations of ACD to acrylates. In a time of abundant access to products containing acrylates, dermatologists should consider this allergy in their differential diagnosis and consider patch testing.

Patch Testing to Acrylates

The gold standard for ACD diagnosis is patch testing. It should be noted that no acrylates are included in the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test series. Several acrylates are tested in expanded patch test series including the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen series and North American 80 Comprehensive Series. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate is thought to be the most important screening allergen to test. Ramos et al16 reported a positive patch test to HEMA in 81% (30/37) of patients who had any type of acrylate allergy.

If initial testing to a limited number of acrylates is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, expanded acrylates/plastics and glue series also are available from commercial patch test suppliers. Testing to an expanded panel of acrylates is especially pertinent to consider in suspected occupational cases given the risk of workplace absenteeism and even disability that come with continued exposure to the allergen. Of note, isobornyl acrylate is not included in the baseline patch test series and must be tested separately, particularly because it usually does not cross-react with other acrylates, and therefore allergy could be missed if not tested on its own.

Acrylates are volatile substances that have been shown to degrade at room temperature and to a lesser degree when refrigerated. Ideally, they should be stored in a freezer and not used beyond their expiration date. Furthermore, it is advised that acrylate patch tests be prepared immediately prior to placement on the patient and to discard the initial extrusion from the syringe, as the concentration at the tip may be decreased.46,47

With regard to tissue adhesives, the actual product should be tested as-is because these are not commercially available patch test substances.48 Occasionally, patients who are sensitized to the tissue adhesive will not react when patch tested on intact skin. If clinical suspicion remains high, scratch patch testing may confirm contact allergy in cases of negative testing on intact skin.49

Management and Prevention

Once a diagnosis of ACD secondary to acrylates has been established, counseling patients on allergen avoidance strategies is essential. For (meth)acrylate-allergic patients who want to continue using modern nail products, cyanoacrylate-based options (eg, dipped, press-on nails) can be considered as an alternative, as they do not cross-react, though independent sensitization is still possible. However, traditional nail polish is the safest option to recommend.

The concern with acrylate sensitization extends beyond the immediate issue that brought the patient into your clinic. Dermatologists must counsel patients who are sensitized to acrylates on the possible sequelae of acrylate-containing dental or orthopedic procedures. Oral lichenoid lesions, denture stomatitis, burning mouth syndrome, or even acute facial swelling have been reported following dental work in patients with acrylate allergy.50-53 Dentists of patients with acrylate ACD should be informed of the diagnosis so acrylates can be avoided during dental work; if unavoidable, all possible steps should be taken to ensure complete curing of the monomers. In the surgical setting, patients sensitized to cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives should be offered wound closure alternatives such as sutures or staples.34

In patients with diabetes mellitus who develop ACD to their glucose monitor or insulin pump, ideally they should be switched to a device that does not contain acrylates. Problematically, these devices are constantly being reformulated, and manufacturers do not always divulge their components, which can make it challenging to determine safe alternative options.32,54 Various barrier products may help on a case-by-case basis.55Preventative measures should be implemented in workplaces that utilize acrylates, including dental practices and nail salons. Acrylic monomers have been shown to penetrate most gloves within minutes of exposure.56,57 Double gloving with nitrile gloves affords some protection for no longer than 60 minutes.6 4H gloves have been shown to provide true protection but result in a loss of dexterity.58 The fingerstall technique involves removing the fingers from a 4H glove, inserting them on the fingers, and applying a more flexible glove on top to hold them in place; this offers a hybrid between protection and finger dexterity.59

Final Interpretation

In a world characterized by technological advancements and increasing accessibility to acrylate-containing products, we hope this brief review serves as a resource and reminder to dermatologists to consider acrylates as a potential cause of ACD with diverse presentations and important future implications for affected individuals. The rising trend of acrylate allergy necessitates comprehensive assessment and shared decision-making between physicians and patients. As we navigate the ever-changing landscape of materials and technologies, clinicians must remain vigilant to avoid some potentially sticky situations for patients.

Acrylates are a ubiquitous family of synthetic thermoplastic resins that are employed in a wide array of products. Since the discovery of acrylic acid in 1843 and its industrialization in the early 20th century, acrylates have been used by many different sectors of industry.1 Today, acrylates can be found in diverse sources such as adhesives, coatings, electronics, nail cosmetics, dental materials, and medical devices. Although these versatile compounds have revolutionized numerous sectors, their potential to trigger allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) has garnered considerable attention in recent years. In 2012, acrylates as a group were named Allergen of the Year by the American Contact Dermatitis Society,2 and one member—isobornyl acrylate—also was given the infamous award in 2020.3 In this article, we highlight the chemistry of acrylates, the growing prevalence of acrylate contact allergy, common sources of exposure, patch testing considerations, and management/prevention strategies.

Chemistry and Uses of Acrylates

Acrylates are widely used due to their pliable and resilient properties.4 They begin as liquid monomers of (meth)acrylic acid or cyanoacrylic acid that are molded to the desired application before being cured or hardened by one of several means: spontaneously, using chemical catalysts, or with heat, UV light, or a light-emitting diode. Once cured, the final polymers (ie, [meth]acrylates, cyanoacrylates) serve a myriad of different purposes. Table 1 includes some of the more clinically relevant sources of acrylate exposure. Although this list is not comprehensive, it offers a glimpse into the vast array of uses for acrylates.

Acrylate Contact Allergy

Acrylic monomers are potent contact allergens, but the polymerized final products are not considered allergenic, assuming they are completely cured; however, ACD can occur with incomplete curing.6 It is of clinical importance that once an individual becomes sensitized to one type of acrylate, they may develop cross-reactions to others contained in different products. Notably, cyanoacrylates generally do not cross-react with (meth)acrylates; this has important implications for choosing safe alternative products in sensitized patients, though independent sensitization to cyanoacrylates is possible.7,8

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The prevalence of acrylate allergy in the general population is unknown; however, there is a trend of increased patch test positivity in studies of patients referred for patch testing. A 2018 study by the European Environmental Contact Dermatitis Research Group reported positive patch tests to acrylates in 1.1% of 18,228 patients tested from 2013 to 2015.9 More recently, a multicenter European study (2019-2020) reported a 2.3% patch test positivity to 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) among 7675 tested individuals,10 and even higher HEMA positivity was reported in Spain (3.7% of 1884 patients in 2019-2020).11 In addition, the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) reported positive patch test reactions to HEMA in 3.2% of 4111 patients tested from 2019 to 2020, a statistically significant increase compared with those tested in 2009 to 2018 (odds ratio, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.03-1.51]; P=.02).12

Historically, acrylate sensitization primarily stemmed from occupational exposure. A retrospective analysis of occupational dermatitis performed by the NACDG (2001-2016) showed that HEMA was among the top 10 most common occupational allergens (3.4% positivity [83/2461]) and had the fifth highest percentage of occupationally relevant reactions (73.5% [83/113]).13 High-risk occupations include dental providers and nail technicians. Dentistry utilizes many materials containing acrylates, including uncured plastic resins used in dental prostheses, dentin bonding materials, and glass ionomers.14 A retrospective analysis of 585 dental personnel who were patch tested by the NACDG (2001-2018) found that more than 20% of occupational ACD cases were related to acrylates.15 Nail technicians are another group routinely exposed to acrylates through a variety of modern nail cosmetics. In a 7-year study from Portugal evaluating acrylate ACD, 68% (25/37) of cases were attributed to occupation, 80% (20/25) of which were in nail technicians.16 Likewise, among 28 nail technicians in Sweden who were referred for patch testing, 57% (16/28) tested positive for at least 1 acrylate.17

Modern Sources of Acrylate Exposure

Once thought to be a predominantly occupational exposure, acrylates have rapidly made their way into everyday consumer products. Clinicians should be aware of several sources of clinically relevant acrylate exposure, including nail cosmetics, consumer electronics, and medical/surgical adhesives.

A 2016 study found a shift to nail cosmetics as the most common source of acrylate sensitization.18 Nail cosmetics that contain acrylates include traditional acrylic, gel (shellac), dipped, and press-on (false) nails.19 The NACDG found that the most common allergen in patients experiencing ACD associated with nail products (2001-2016) was HEMA (56.6% [273/482]), far ahead of the traditional nail polish allergen tosylamide (36.2% [273/755]). Over the study period, the frequency of positive patch tests statistically increased for HEMA (P=.0069) and decreased for tosylamide (P<.0001).20 There is concern that the use of home gel nail kits, which can be purchased online at the click of a button, may be associated with a risk for acrylate sensitization.21,22 A recent study surveyed a Facebook support group for individuals with self-reported reactions to nail cosmetics, finding that 78% of the 199 individuals had used at-home gel nail kits, and more than 80% of them first developed skin reactions after starting to use at-home kits.23 The risks for sensitization are thought to be greater when self-applying nail acrylates compared to having them done professionally because individuals are more likely to spill allergenic monomers onto the skin at home; it also is possible that home techniques could lead to incomplete curing. Table 2 reviews the different types of acrylic nail cosmetics.

Medical adhesives and equipment are other important areas where acrylates can be encountered in abundance. A review by Spencer et al18 cautioned wound dressings as an up-and-coming source of sensitization, and this has been demonstrated in the literature as coming to fruition.26 Another study identified acrylates in 15 of 16 (94%) tested medical adhesives; among 7 medical adhesives labeled as hypoallergenic, 100% still contained acrylates and/or abietic acid.27 Multiple case reports have described ACD to adhesives of electrocardiogram electrodes containing acrylates.28-31 Physicians providing care to patients with diabetes mellitus also must be aware of acrylates in glucose monitors and insulin pumps, either found in the adhesives or leaching from the inside of the device to reach the skin.32 Isobornyl acrylate in particular has made quite the name for itself in this sector, being crowned the 2020 Allergen of the Year owing to its key role in cases of ACD to diabetes devices.3

Cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives (eg, 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate) are now well documented to cause postoperative ACD.33,34 Although robust prospective data are limited, studies suggest that 2% to 14% of patients develop postoperative skin reactions following 2-octyl cyanoacrylate application.35-37 It has been shown that sensitization to tissue adhesives often occurs after the first application, followed by an eruption of ACD as long as a month later, which can create confusion about the nature of the rash for patients and health care providers alike, who may for instance attribute it to infection rather than allergy.38 In the orthopedic literature, a woman with a known history of acrylic nail ACD had knee arthroplasty failure attributed to acrylic bone cement with resolution of the joint symptoms after changing to a cementless device.39

Awareness of the common use of acrylates is important to identify the cause of reactions from products that would otherwise seem nonallergenic. A case of occupational ACD to isobornyl acrylate in UV-cured phone screen protectors has been reported40; several cases of ACD to acrylates in headphones41,42 as well as one related to a wearable fitness device also have been reported.43 Given all these possible sources of exposure, ACD to acrylates should be on your radar.

When to Consider Acrylate ACD

When working up a patient with dermatitis, it is essential to ask about occupational history and hobbies to get a sense of potential contact allergen exposures. The typical presentation of occupational acrylate-associated ACD is hand eczema, specifically involving the fingertips.5,24,25,44 Acrylate ACD should be considered in patients with nail dystrophy and a history of wearing acrylic nails.45 There can even be involvement of the face and eyelids secondary to airborne contact or ectopic spread from the hands.24 Spreading vesicular eruptions associated with adhesives also should raise concern. The Figure depicts several possible presentations of ACD to acrylates. In a time of abundant access to products containing acrylates, dermatologists should consider this allergy in their differential diagnosis and consider patch testing.

Patch Testing to Acrylates

The gold standard for ACD diagnosis is patch testing. It should be noted that no acrylates are included in the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test series. Several acrylates are tested in expanded patch test series including the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen series and North American 80 Comprehensive Series. 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate is thought to be the most important screening allergen to test. Ramos et al16 reported a positive patch test to HEMA in 81% (30/37) of patients who had any type of acrylate allergy.

If initial testing to a limited number of acrylates is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, expanded acrylates/plastics and glue series also are available from commercial patch test suppliers. Testing to an expanded panel of acrylates is especially pertinent to consider in suspected occupational cases given the risk of workplace absenteeism and even disability that come with continued exposure to the allergen. Of note, isobornyl acrylate is not included in the baseline patch test series and must be tested separately, particularly because it usually does not cross-react with other acrylates, and therefore allergy could be missed if not tested on its own.

Acrylates are volatile substances that have been shown to degrade at room temperature and to a lesser degree when refrigerated. Ideally, they should be stored in a freezer and not used beyond their expiration date. Furthermore, it is advised that acrylate patch tests be prepared immediately prior to placement on the patient and to discard the initial extrusion from the syringe, as the concentration at the tip may be decreased.46,47

With regard to tissue adhesives, the actual product should be tested as-is because these are not commercially available patch test substances.48 Occasionally, patients who are sensitized to the tissue adhesive will not react when patch tested on intact skin. If clinical suspicion remains high, scratch patch testing may confirm contact allergy in cases of negative testing on intact skin.49

Management and Prevention

Once a diagnosis of ACD secondary to acrylates has been established, counseling patients on allergen avoidance strategies is essential. For (meth)acrylate-allergic patients who want to continue using modern nail products, cyanoacrylate-based options (eg, dipped, press-on nails) can be considered as an alternative, as they do not cross-react, though independent sensitization is still possible. However, traditional nail polish is the safest option to recommend.

The concern with acrylate sensitization extends beyond the immediate issue that brought the patient into your clinic. Dermatologists must counsel patients who are sensitized to acrylates on the possible sequelae of acrylate-containing dental or orthopedic procedures. Oral lichenoid lesions, denture stomatitis, burning mouth syndrome, or even acute facial swelling have been reported following dental work in patients with acrylate allergy.50-53 Dentists of patients with acrylate ACD should be informed of the diagnosis so acrylates can be avoided during dental work; if unavoidable, all possible steps should be taken to ensure complete curing of the monomers. In the surgical setting, patients sensitized to cyanoacrylate-based tissue adhesives should be offered wound closure alternatives such as sutures or staples.34

In patients with diabetes mellitus who develop ACD to their glucose monitor or insulin pump, ideally they should be switched to a device that does not contain acrylates. Problematically, these devices are constantly being reformulated, and manufacturers do not always divulge their components, which can make it challenging to determine safe alternative options.32,54 Various barrier products may help on a case-by-case basis.55Preventative measures should be implemented in workplaces that utilize acrylates, including dental practices and nail salons. Acrylic monomers have been shown to penetrate most gloves within minutes of exposure.56,57 Double gloving with nitrile gloves affords some protection for no longer than 60 minutes.6 4H gloves have been shown to provide true protection but result in a loss of dexterity.58 The fingerstall technique involves removing the fingers from a 4H glove, inserting them on the fingers, and applying a more flexible glove on top to hold them in place; this offers a hybrid between protection and finger dexterity.59

Final Interpretation

In a world characterized by technological advancements and increasing accessibility to acrylate-containing products, we hope this brief review serves as a resource and reminder to dermatologists to consider acrylates as a potential cause of ACD with diverse presentations and important future implications for affected individuals. The rising trend of acrylate allergy necessitates comprehensive assessment and shared decision-making between physicians and patients. As we navigate the ever-changing landscape of materials and technologies, clinicians must remain vigilant to avoid some potentially sticky situations for patients.

- Staehle HJ, Sekundo C. The origins of acrylates and adhesive technologies in dentistry. J Adhes Dent. 2021;23:397-406.

- Militello M, Hu S, Laughter M, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergens of the Year 2000 to 2020. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:309-320.

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Ajekwene KK. Properties and applications of acrylates. In: Serrano-Aroca A, Deb S, eds. Acrylate Polymers for Advanced Applications. IntechOpen; 2020:35-46. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.89867

- Voller LM, Warshaw EM. Acrylates: new sources and new allergens. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:277-283.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2012;23:6-16.

- Gardeen S, Hylwa S. A review of acrylates: super glue, nail adhesives, and diabetic pump adhesives increasing sensitization risk in women and children. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:263-267.

- Chou M, Dhingra N, Strugar TL. Contact sensitization to allergens in nail cosmetics. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2017;28:231-240.

- Gonçalo M, Pinho A, Agner T, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by nail acrylates in Europe. an EECDRG study. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:254-260.

- Uter W, Wilkinson SM, Aerts O, et al. Patch test results with the European baseline series, 2019/20-Joint European results of the ESSCA and the EBS working groups of the ESCD, and the GEIDAC. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:343-355.

- Hernández-Fernández CP, Mercader-García P, Silvestre Salvador JF, et al. Candidate allergens for inclusion in the Spanish standard series based on data from the Spanish Contact Dermatitis Registry. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:798-805.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2023;34:90-104.

- DeKoven JG, DeKoven BM, Warshaw EM, et al. Occupational contact dermatitis: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2001 to 2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:782-790.

- Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Schubert S, et al. Contact sensitization in dental technicians with occupational contact dermatitis. data of the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) 2001-2015. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:266-273.

- Warshaw EM, Ruggiero JL, Atwater AR, et al. Occupational contact dermatitis in dental personnel: a retrospective analysis of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group Data, 2001 to 2018. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2022;33:80-90.

- Ramos L, Cabral R, Gonçalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates—a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:102-107.

- Fisch A, Hamnerius N, Isaksson M. Dermatitis and occupational (meth)acrylate contact allergy in nail technicians—a 10-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:58-60.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

- DeKoven S, DeKoven J, Holness DL. (Meth)acrylate occupational contact dermatitis in nail salon workers: a case series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:340-344.

- Warshaw EM, Voller LM, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with nail care products: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2016. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:191-201.

- Le Q, Cahill J, Palmer-Le A, et al. The rising trend in allergic contact dermatitis to acrylic nail products. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:221-223.

- Gatica-Ortega ME, Pastor-Nieto M. The present and future burden of contact dermatitis from acrylates in manicure. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2020;7:1-21.

- Guenther J, Norman T, Wee C, et al. A survey of skin reactions associated with acrylic nail cosmetics, with a focus on home kits: is there a need for regulation [published online October 16, 2023]? Dermatitis. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0204

- Calado R, Gomes T, Matos A, et al. Contact dermatitis to nail cosmetics. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2021;10:173-181.

- Draelos ZD. Nail cosmetics and adornment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:351-359.

- Mestach L, Huygens S, Goossens A, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylic-based medical dressings and adhesives. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:81-84.

- Tam I, Wang JX, Yu JD. Identifying acrylates in medical adhesives. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2020;31:E40-E42.

- Stingeni L, Cerulli E, Spalletti A, et al. The role of acrylic acid impurity as a sensitizing component in electrocardiogram electrodes. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:44-48.

- Ozkaya E, Kavlak Bozkurt P. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by self-adhesive electrocardiography electrodes: a rare case with concomitant roles of nickel and acrylates. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;70:121-123.

- Lyons G, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis to methacrylates in ECG electrode dots. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:39-40.

- Jelen G. Acrylate, a hidden allergen of electrocardiogram electrodes. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:315-316.

- Bembry R, Brys AK, Atwater AR. Medical device contact allergy: glucose monitors and insulin pumps. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2022;11:13-20.

- Liu T, Wan J, McKenna RA, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by Dermabond in a paediatric patient undergoing skin surgery. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:61-62.

- Ricciardo BM, Nixon RL, Tam MM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond Prineo after elective orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2020;43:E515-E522.

- Nigro LC, Parkerson J, Nunley J, et al. Should we stick with surgical glues? the incidence of dermatitis after 2-octyl cyanoacrylate exposure in 102 consecutive breast cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:32-37.

- Alotaibi NN, Ahmad T, Rabah SM, et al. Type IV hypersensitivity reaction to Dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) in plastic surgical patients: a retrospective study. Plast Surg Oakv Ont. 2022;30:222-226.

- Durando D, Porubsky C, Winter S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) after total knee arthroplasty. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2014;25:99-100.

- Asai C, Inomata N, Sato M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis due to the liquid skin adhesive Dermabond® predominantly occurs after the first exposure. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:103-108.

- Haughton AM, Belsito DV. Acrylate allergy induced by acrylic nails resulting in prosthesis failure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:S123-S124.

- Amat-Samaranch V, Garcia-Melendo C, Tubau C, et al. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis to isobornyl acrylate present in cell phone screen protectors. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;84:352-354.

- Chan J, Rabi S, Adler BL. Allergic contact dermatitis to (meth)acrylates in Apple AirPods headphones. Dermatitis. 2021;32:E111-E112.

- Shaver RL, Buonomo M, Scherman JA, et al. Contact allergy to acrylates in Apple AirPods Pro® headphones: a case series. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:E459-E461.

- Winston FK, Yan AC. Wearable health device dermatitis: a case of acrylate-related contact allergy. Cutis. 2017;100:97-99.

- Kucharczyk M, Słowik-Rylska M, Cyran-Stemplewska S, et al. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:555-560.

- Nanda S. Nail salon safety: from nail dystrophy to acrylate contact allergies. Cutis. 2022;110:E32-E33.

- Joy NM, Rice KR, Atwater AR. Stability of patch test allergens. Dermat Contact Atopic Occup Drug. 2013;24:227-236.