User login

Taking a new obesity drug and birth control pills? Be careful

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

For women who are obese, daily life is wrought with landmines. Whether it’s the challenges of air travel because plane seats are too small, the need to shield themselves from the world’s discriminating eyes, or the great lengths many will go to achieve better health and the promise of longevity, navigating life as an obese person requires a thick skin.

So, it’s no wonder so many are willing to pay more than $1,000 a month out of pocket to get their hands on drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro). The benefits of these drugs, which are part of a new class called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include significant and rapid weight loss, blood sugar control, and improved life quality; they are unprecedented in a setting where surgery has long been considered the most effective long-term option.

On the flip side, the desire for rapid weight loss and better blood sugar control also comes with an unexpected cost. , making an unintended pregnancy more likely.

Neel Shah, MD, an endocrinologist and associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, said he has had several patients become pregnant without intending to.

“It was when Mounjaro came out on the market when we started using it,” he said of the drug the Food and Drug Administration approved for type 2 diabetes in 2022. “It [the warning] was in the product insert, but clinically speaking, I don’t know if it was at the top of providers’ minds when they were prescribing Mounjaro.”

When asked if he believed that we were going to be seeing a significant increase in so-called Mounjaro babies, Dr. Shah was sure in his response.

“Absolutely. We will because the sheer volume [of patients] will increase,” he said.

It’s all in the gut

One of the ways that drugs like Mounjaro work is by delaying the time that it takes for food to move from the stomach to the small intestine. Although data are still evolving, it is believed that this process – delayed gastric emptying – may affect the absorption of birth control pills.

Dr. Shah said another theory is that vomiting, which is a common side effect of these types of drugs, also affects the pills’ ability to prevent pregnancy.

And “there’s a prolonged period of ramping up the dose because of the GI side effects,” said Pinar Kodaman, MD, PhD, a reproductive endocrinologist and assistant professor of gynecology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

“Initially, at the lowest dose, there may not be a lot of potential effect on absorption and gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes more common, and it can cause diarrhea, which is another condition that can affect the absorption of any medication,” she said.

Unanticipated outcomes, extra prevention

Roughly 42% of women in the United States are obese, 40% of whom are between the ages of 20 and 39. Although these new drugs can improve fertility outcomes for women who are obese (especially those with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS), only one – Mounjaro – currently carries a warning about birth control pill effectiveness on its label. Unfortunately, it appears that some doctors are unaware or not counseling patients about this risk, and the data are unclear about whether other drugs in this class, like Ozempic and Wegovy, have the same risks.

“To date, it hasn’t been a typical thing that we counsel about,” said Dr. Kodaman. “It’s all fairly new, but when we have patients on birth control pills, we do review other medications that they are on because some can affect efficacy, and it’s something to keep in mind.”

It’s also unclear if other forms of birth control – for example, birth control patches that deliver through the skin – might carry similar pregnancy risks. Dr. Shah said some of his patients who became pregnant without intending to were using these patches. This raises even more questions, since they deliver drugs through the skin directly into the bloodstream and not through the GI system.

What can women do to help ensure that they don’t become pregnant while using these drugs?

“I really think that if patients want to protect themselves from an unplanned pregnancy, that as soon as they start the GLP receptor agonists, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to use condoms, because the onset of action is pretty quick,” said Dr. Kodaman, noting also that “at the lowest dose there may not be a lot of potential effect on gastric emptying. But as the dose goes up, it becomes much more common or can cause diarrhea.”

Dr. Shah said that in his practice he’s “been telling patients to add barrier contraception” 4 weeks before they start their first dose “and at any dose adjustment.”

Zoobia Chaudhry, an obesity medicine doctor and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, recommends that “patients just make sure that the injection and medication that they take are at least 1 hour apart.”

“Most of the time, patients do take birth control before bedtime, so if the two are spaced, it should be OK,” she said.

Another option is for women to speak to their doctors about other contraceptive options like IUDs or implantable rods, where gastric absorption is not going to be an issue.

“There’s very little research on this class of drugs,” said Emily Goodstein, a 40-year-old small-business owner in Washington, who recently switched from Ozempic to Mounjaro. “Being a person who lives in a larger body is such a horrifying experience because of the way that the world discriminates against you.”

She appreciates the feeling of being proactive that these new drugs grant. It has “opened up a bunch of opportunities for me to be seen as a full individual by the medical establishment,” she said. “I was willing to take the risk, knowing that I would be on these drugs for the rest of my life.”

In addition to being what Dr. Goodstein refers to as a guinea pig, she said she made sure that her primary care doctor was aware that she was not trying or planning to become pregnant again. (She has a 3-year-old child.) Still, her doctor mentioned only the most common side effects linked to these drugs, like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, and did not mention the risk of pregnancy.

“Folks are really not talking about the reproductive implications,” she said, referring to members of a Facebook group on these drugs that she belongs to.

Like patients themselves, many doctors are just beginning to get their arms around these agents. “Awareness, education, provider involvement, and having a multidisciplinary team could help patients achieve the goals that they set out for themselves,” said Dr. Shah.

Clear conversations are key.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

2023 Update on contraception

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

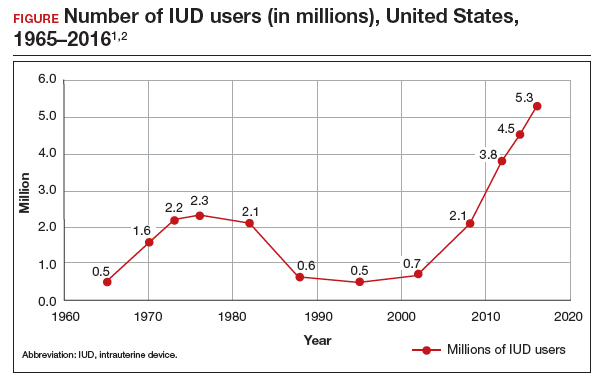

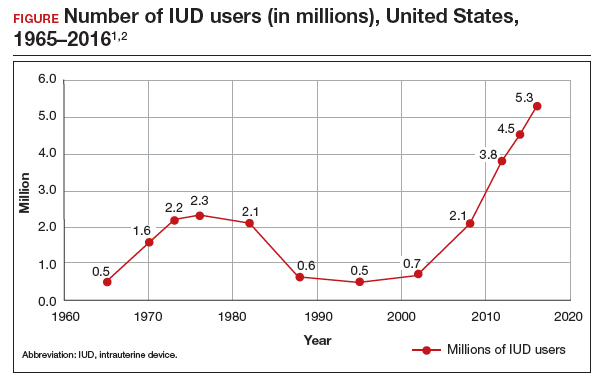

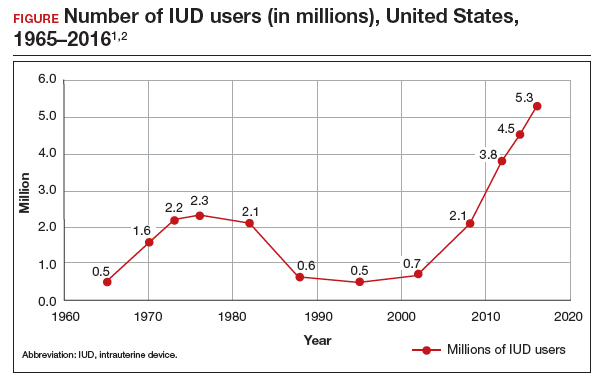

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

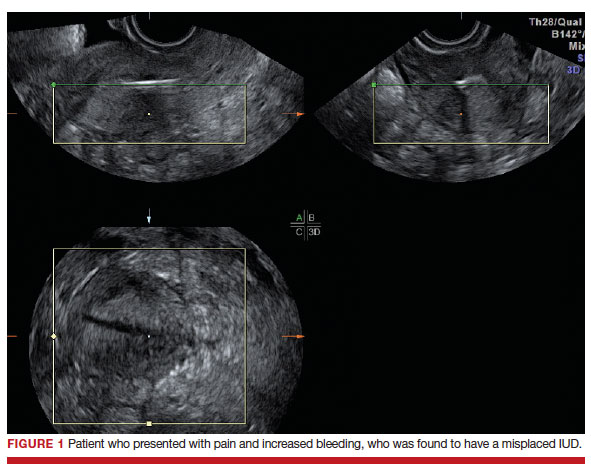

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

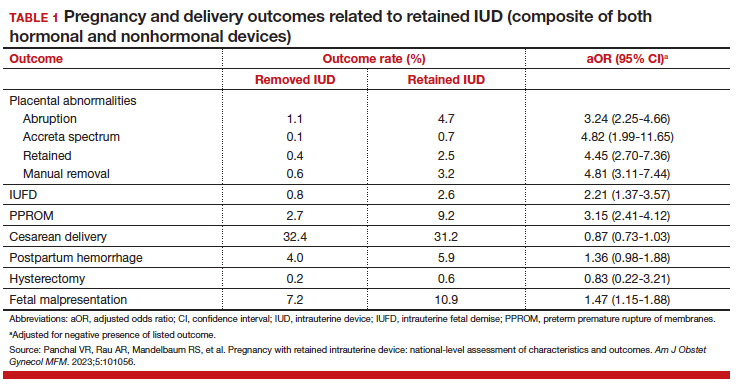

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

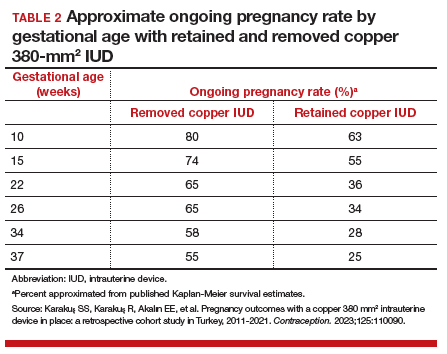

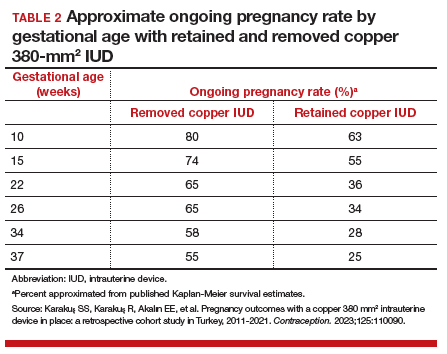

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

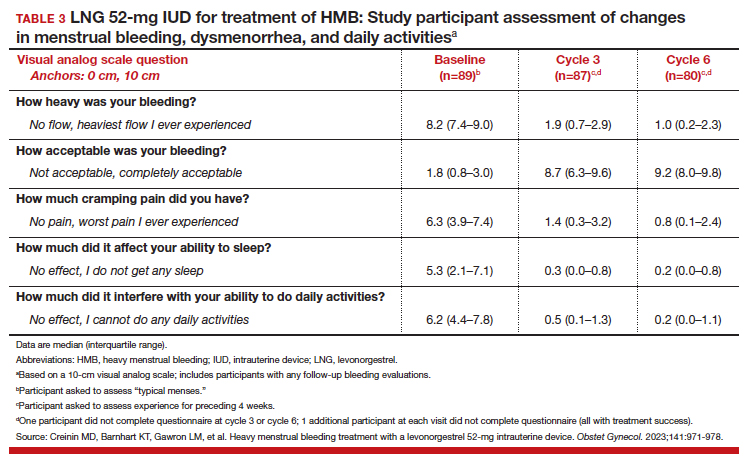

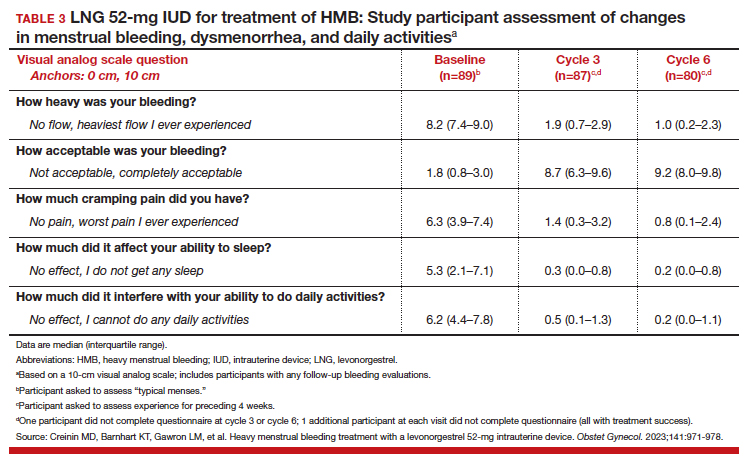

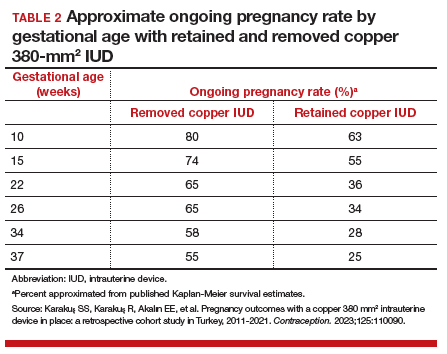

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

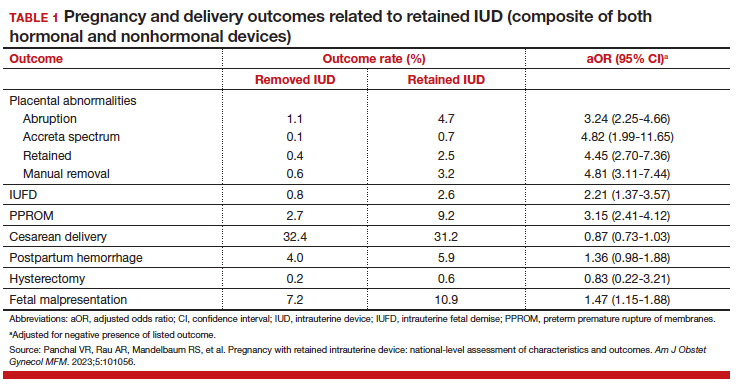

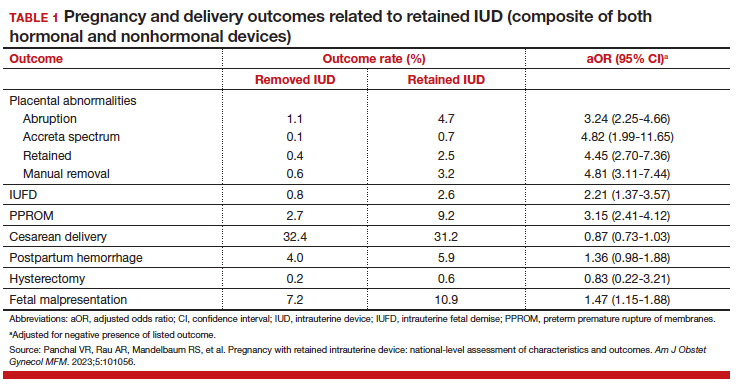

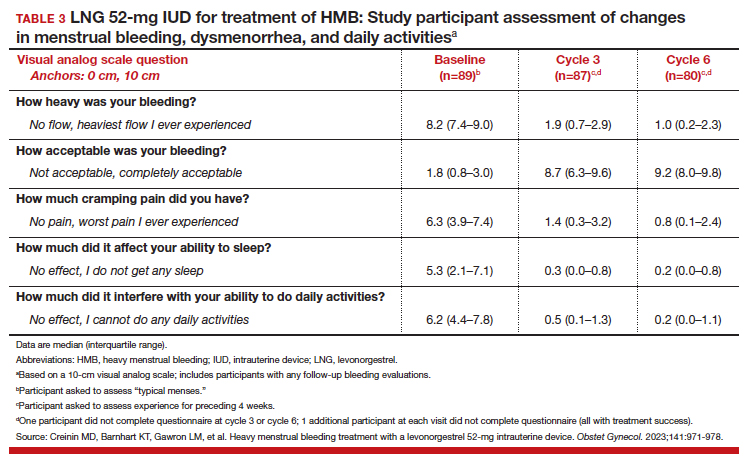

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

More US women are using IUDs than ever before. With more use comes the potential for complications and more requests related to non-contraceptive benefits. New information provides contemporary insight into rare IUD complications and the use of hormonal IUDs for treatment of HMB.

The first intrauterine device (IUD) to be approved in the United States, the Lippes Loop, became available in 1964. Sixty years later, more US women are using IUDs than ever before, and numbers are trending upward (FIGURE).1,2 Over the past year, contemporary information has become available to further inform IUD management when pregnancy occurs with an IUD in situ, as well as counseling about device breakage. Additionally, new data help clinicians expand which patients can use a levonorgestrel (LNG) 52-mg IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) treatment.

As the total absolute number of IUD users increases, so do the absolute numbers of rare outcomes, such as pregnancy among IUD users. These highly effective contraceptives have a failure rate within the first year after placement ranging from 0.1% for the LNG 52-mg IUD to 0.8% for the copper 380-mm2 IUD.3 Although the possibility for extrauterine gestation is higher when pregnancy occurs while a patient is using an IUD as compared with most other contraceptive methods, most pregnancies that occur with an IUD in situ are intrauterine.4

The high contraceptive efficacy of IUDs make pregnancy with a retained IUD rare; therefore, it is difficult to perform a study with a large enough population to evaluate management of pregnancy complicated by an IUD in situ. Clinical management recommendations for these situations are 20 years old and are supported by limited data from case reports and series with fewer than 200 patients.5,6

Intrauterine device breakage is another rare event that is poorly understood due to the low absolute number of cases. Information about breakage has similarly been limited to case reports and case series.7,8 This past year, contemporary data were published to provide more insight into both intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in situ and IUD breakage.

Beyond contraception, hormonal IUDs have become a popular and evidence-based treatment option for patients with HMB. The initial LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) regulatory approval studies for HMB treatment included data limited to parous patients and users with a body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2.9 Since that time, no studies have explored these populations. Although current practice has commonly extended use to include patients with these characteristics, we have lacked outcome data. New phase 3 data on the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) included a broader range of participants and provide evidence to support this practice.

Removing retained copper 380-mm2 IUDs improves pregnancy outcomes

Panchal VR, Rau AR, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Pregnancy with retained intrauterine device: national-level assessment of characteristics and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:101056. doi:10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101056

Karakuş SS, Karakuş R, Akalın EE, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with a copper 380 mm2 intrauterine device in place: a retrospective cohort study in Turkey, 2011-2021. Contraception. 2023;125:110090. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110090

To update our understanding of outcomes of pregnancy with an IUD in situ, Panchal and colleagues performed a cross-sectional study using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample. This data set represents 85% of US hospital discharges. The population investigated included hospital deliveries from 2016 to 2020 with an ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) code of retained IUD. Those without the code were assigned to the comparison non-retained IUD group.

The primary outcome studied was the incidence rate of retained IUD, patient and pregnancy characteristics, and delivery outcomes including but not limited to gestational age at delivery, placental abnormalities, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, and hysterectomy.

Outcomes were worse with retained IUD, regardless of IUD removal status

The authors found that an IUD in situ was reported in 1 out of 8,307 pregnancies and was associated with PPROM, fetal malpresentation, IUFD, placental abnormalities including abruption, accreta spectrum, retained placenta, and need for manual removal (TABLE 1). About three-quarters (76.3%) of patients had a term delivery (≥37 weeks).

Retained IUD was associated with previable loss, defined as less than 22 weeks’ gestation (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.30–9.15) and periviable delivery, defined as 22 to 25 weeks’ gestation (aOR, 2.81; 95% CI, 1.63–4.85). Retained IUD was not associated with preterm delivery beyond 26 weeks’ gestation, cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, or hysterectomy.

Important limitations of this study are the lack of information on IUD type (copper vs hormonal) and the timing of removal or attempted removal in relation to measured pregnancy outcomes.

Continue to: Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes...

Removal of copper IUD improves, but does not eliminate, poor pregnancy outcomes

Karakus and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 233 patients in Turkey with pregnancies that occurred during copper 380-mm2 IUD use from 2011 to 2021. The authors reported that, at the time of first contact with the health system and diagnosis of retained IUD, 18.9% of the pregnancies were ectopic, 13.2% were first trimester losses, and 67.5% were ongoing pregnancies.

The authors assessed outcomes in patients with ongoing pregnancies based on whether or not the IUD was removed or retained. Outcomes included gestational age at delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes, assessed as a composite of preterm delivery, PPROM, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Of those with ongoing pregnancies, 13.3% chose to have an abortion, leaving 137 (86.7%) with continuing pregnancy. The IUD was able to be removed in 39.4% of the sample, with an average gestational age of 7 weeks at the time of removal.

Compared with those with a retained IUD, patients in the removal group had a lower rate of pregnancy loss (33.3% vs 61.4%; P<.001) and a lower rate of the composite adverse pregnancy outcomes (53.1% vs 27.8%; P=.03). TABLE 2 shows the approximate rate of ongoing pregnancy by gestational age in patients with retained and removed copper 380-mm2 IUDs. Notably, the largest change occurred periviably, with the proportion of patients with an ongoing pregnancy after 26 weeks reducing to about half for patients with a retained IUD as compared with patients with a removed IUD; this proportion of ongoing pregnancies held through the remainder of gestation.

These studies confirm that a retained IUD is a rare outcome, occurring in about 1 in 8,000 pregnancies. Previous US national data from 2010 reported a similar incidence of 1 in 6,203 pregnancies (0.02%).10 Management and counseling depend on the patient’s desire to continue the pregnancy, gestational age, intrauterine IUD location, and ability to see the IUD strings. Contemporary data support management practices created from limited and outdated data, which include device removal (if able) and counseling those who desire to continue pregnancy about high-risk pregnancy complications. Those with a retained IUD should be counseled about increased risk of preterm or previable delivery, IUFD, and placental abnormalities (including accreta spectrum and retained placenta). Specifically, these contemporary data highlight that, beyond approximately 26 weeks’ gestation, the pregnancy loss rate is not different for those with a retained or removed IUD. Obstetric care providers should feel confident in using this more nuanced risk of extreme preterm delivery when counseling future patients. Implications for antepartum care and delivery timing with a retained IUD have not yet been defined.

Do national data reveal more breakage reports for copper 380-mm2 or LNG IUDs?

Latack KR, Nguyen BT. Trends in copper versus hormonal intrauterine device breakage reporting within the United States’ Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Contraception. 2023;118:109909. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.10.011

Latack and Nguyen reviewed postmarket surveillance data of IUD adverse events in the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) from 1998 to 2022. The FAERS is a voluntary, or passive, reporting system.

Study findings

Of the approximately 170,000 IUD-related adverse events reported to the agency during the 24-year timeframe, 25.4% were for copper IUDs and 74.6% were for hormonal IUDs. Slightly more than 4,000 reports were specific for device breakage, which the authors grouped into copper (copper 380-mm2)and hormonal (LNG 52 mg, 19.5 mg, and 13.5 mg) IUDs.

The copper 380-mm2 IUD was 6.19 times more likely to have a breakage report than hormonal IUDs (9.6% vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 5.87–6.53).

The overall proportion of IUD-related adverse events reported to the FDA was about 25% for copper and 75% for hormonal IUDs; this proportion is similar to sales figures, which show that about 15% of IUDs sold in the United States are copper and 85% are hormonal.11 However, the proportion of breakage events reported to the FDA is the inverse, with about 6 times more breakage reports with copper than with hormonal IUDs. Because these data come from a passive reporting system, the true incidence of IUD breakage cannot be assessed. However, these findings should remind clinicians to inform patients about this rare occurrence during counseling at the time of placement and, especially, when preparing for copper IUD removal. As the absolute number of IUD users increases, clinicians may be more likely to encounter this relatively rare event.

Management of IUD breakage is based on expert opinion, and recommendations are varied, ranging from observation to removal using an IUD hook, alligator forceps, manual vacuum aspiration, or hysteroscopy.7,10 Importantly, each individual patient situation will vary depending on the presence or absence of other symptoms and whether or not future pregnancy is desired.

Continue to: Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients...

Data support the LNG 52-mg IUD for HMB in nulliparous and obese patients

Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi:10.1097AOG.0000000000005137

Creinin and colleagues conducted a study for US regulatory product approval of the LNG 52-mg IUD (Liletta) for HMB. This multicenter phase 3 open-label clinical trial recruited nonpregnant participants aged 18 to 50 years with HMB at 29 clinical sites in the United States. No BMI cutoff was used.

Baseline menstrual flow data were obtained over 2 to 3 screening cycles by collection of menstrual products and quantification of blood loss using alkaline hematin measurement. Patients with 2 cycles with a blood loss exceeding 80 mL had an IUD placement, with similar flow evaluations during the third and sixth postplacement cycles.

Treatment success was defined as a reduction in blood loss by more than 50% as compared with baseline (during screening) and measured blood loss of less than 80 mL. The enrolled population (n=105) included 28% nulliparous users, with 49% and 28% of participants having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher and higher than 35 kg/m2, respectively.

Treatment highly successful in reducing blood loss

Participants in this trial had a 93% and a 98% reduction in blood loss at the third and sixth cycles of use, respectively. Additionally, during the sixth cycle of use, 19% of users had no bleeding. Treatment success occurred in about 80% of participants overall and occurred regardless of parity or BMI.

To assess a subjective measure of success, participants were asked to evaluate their menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea severity, acceptability, and overall impact on quality of life at 3 time points: during prior typical menses, cycle 3, and cycle 6. At cycle 6, all participants reported significantly improved acceptability of bleeding and uterine pain and, importantly, decreased overall menstrual interference with the ability to complete daily activities (TABLE 3).

IUD expulsion and replacement rates

Although bleeding greatly decreased in all participants, 13% (n=14) discontinued before cycle 6 due to expulsion or IUD-related symptoms, with the majority citing bleeding irregularities. Expulsion occurred in 9% (n=5) of users, with the majority (2/3) occurring in the first 3 months of use and more commonly in obese and/or parous users. About half of participants with expulsion had the IUD replaced during the study. ●

Interestingly, both LNG 52-mg IUDs have been approved in most countries throughout the world for HMB treatment, and only in the United States was one of the products (Liletta) not approved until this past year. The FDA required more stringent trials than had been previously performed for approval outside of the United States. However, a benefit for clinicians is that this phase 3 study provided data in a contemporary US population. Clinicians can feel confident in counseling and offering the LNG 52-mg IUD as a first-line treatment option for patients with HMB, including those who have never been pregnant or have a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.

Importantly, though, clinicians should be realistic with all patients that this treatment, although highly effective, is not successful for about 20% of patients by about 6 months of use. For those in whom the treatment is beneficial, the quality-of-life improvement is dramatic. Additionally, this study reminds us that expulsion risk in a population primarily using the IUD for HMB, especially if also obese and/or parous, is higher in the first 6 months of use than patients using the method for contraception. Expulsion occurs in 1.6% of contraception users through 6 months of use.12 These data highlight that IUD expulsion risk is not a fixed number, but instead is modified by patient characteristics. Patients should be counseled regarding the appropriate expulsion risk and that the IUD can be safely replaced should expulsion occur.

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

- Hubacher D, Kavanaugh M. Historical record-setting trends in IUD use in the United States. Contraception. 2018;98:467470. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.05.016

- Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. F S Rep. 2020;1:83-93. doi:10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:15.

- Jensen JT, Creinin MD. Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020:185.

- Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Tasdemir UG, Uygur D, et al. Outcome of intrauterine pregnancies with intrauterine device in place and effects of device location on prognosis. Contraception. 2014;89:426-430. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.002

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85:131-139. doi:10.1016/j.contraception . 2011.06.010

- Wilson S, Tan G, Baylson M, et al. Controversies in family planning: how to manage a fractured IUD. Contraception. 2013;88:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.07.007

- Fulkerson Schaeffer S, Gimovsky AC, Aly H, et al. Pregnancy and delivery with an intrauterine device in situ: outcomes in the National Inpatient Sample Database. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:798-803. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1 391783

- Mirena. Prescribing information. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www .mirena-us.com/pi

- Myo MG, Nguyen BT. Intrauterine device complications and their management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12:88-95. doi.org/10.1007/s13669-023-00357-8

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2017-2019 National Survey of Family Growth. Public-Use Data File Documentation. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data /nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-MainText-508.pdf

- Gilliam ML, Jensen JT, Eisenberg DL, et al. Relationship of parity and prior cesarean delivery to levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system expulsion over 6 years. Contraception. 2021;103:444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.013

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2023

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Piroxicam boosts success of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception

Adding oral piroxicam to oral levonorgestrel significantly improved the efficacy of emergency contraception, based on data from 860 women.

Oral hormonal emergency contraception (EC) is the most widely used EC method worldwide, but the two currently available drugs, levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate (UPA), are not effective when given after ovulation, wrote Raymond Hang Wun Li, MD, of the University of Hong Kong, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors may disrupt follicular rupture and prevent ovulation, but data on their use in combination with current oral ECs are lacking, the researchers said.

In a study published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 430 women to receive a single oral dose of 1.5 mg levonorgestrel plus 40 mg of the COX-2 inhibitor piroxicam or 1.5 mg levonorgestrel plus a placebo. The study participants were women aged 18 years and older who requested EC within 72 hours of unprotected sex and who had regular menstrual cycles between 24 and 42 days long. The median age of the participants was 30 years; 97% were Chinese. The median time from intercourse to treatment was 18 hours for both groups.

The primary outcome was the percentage of pregnancies prevented, based on pregnancy status 1-2 weeks after treatment.

One pregnancy occurred in the piroxicam group, compared with seven pregnancies in the placebo group, which translated to a significant difference in the percentage of pregnancies prevented (94.7% vs. 63.4%, P < .0001).

No trend toward increased failure rates appeared based on the time elapsed between intercourse and EC use in either group, and no differences appeared in the return or delay of subsequent menstrual periods between the groups.

The most common adverse events (reported by more than 5% of participants in both groups) included fatigue or weakness, nausea, lower abdominal pain, dizziness, and headache.

The choice of piroxicam as the COX inhibitor in conjunction with levonorgestrel for the current study had several potential advantages, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These advantages include the widespread availability and long-acting characteristics of piroxicam, which is also true of levonorgestrel, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the generalizability to other settings and populations, the researchers noted. The efficacy of the levonorgestrel/piroxicam combination in women with a body mass index greater than 26 kg/m2 may be lower, but the current study population did not have enough women in this category to measure the potential effect, they said. The study also did not examine the effect of piroxicam in combination with ulipristal acetate.

However, the results are the first known to demonstrate the improved effectiveness of oral piroxicam coadministered with oral levonorgestrel for EC, they said.

“The strength of this recommendation and changes in clinical guidelines may be determined upon demonstration of reproducible results in further studies,” they added.

Pill combination shows potential and practicality

Oral emergency contraception on demand is an unmet need on a global level, Erica P. Cahill, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and division of family planning services at Stanford (Calif.) University, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Cahill noted the longer half-life of piroxicam compared with other COX-2 inhibitors, which made it a practical choice. Although the study was not powered to evaluate secondary outcomes, bleeding patterns consistent with use of EC pills were observed. Documentation of these patterns is worthwhile, Dr. Cahill said, “because people using emergency contraceptive pills might also be using fertility awareness methods and need to know when they can be certain they are not pregnant.”

Overall, the study supports the addition of 40 mg piroxicam to 1.5 mg levonorgestrel as emergency contraception, said Dr. Cahill. Future studies can build on the current findings by evaluating repeat dosing of the piroxicam/levonorgestrel combination and by evaluating the combination of COX-2 inhibitors and ulipristal acetate to prevent pregnancy, she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Cahill had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Adding oral piroxicam to oral levonorgestrel significantly improved the efficacy of emergency contraception, based on data from 860 women.

Oral hormonal emergency contraception (EC) is the most widely used EC method worldwide, but the two currently available drugs, levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate (UPA), are not effective when given after ovulation, wrote Raymond Hang Wun Li, MD, of the University of Hong Kong, and colleagues. Previous studies suggest that cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors may disrupt follicular rupture and prevent ovulation, but data on their use in combination with current oral ECs are lacking, the researchers said.

In a study published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 430 women to receive a single oral dose of 1.5 mg levonorgestrel plus 40 mg of the COX-2 inhibitor piroxicam or 1.5 mg levonorgestrel plus a placebo. The study participants were women aged 18 years and older who requested EC within 72 hours of unprotected sex and who had regular menstrual cycles between 24 and 42 days long. The median age of the participants was 30 years; 97% were Chinese. The median time from intercourse to treatment was 18 hours for both groups.

The primary outcome was the percentage of pregnancies prevented, based on pregnancy status 1-2 weeks after treatment.

One pregnancy occurred in the piroxicam group, compared with seven pregnancies in the placebo group, which translated to a significant difference in the percentage of pregnancies prevented (94.7% vs. 63.4%, P < .0001).

No trend toward increased failure rates appeared based on the time elapsed between intercourse and EC use in either group, and no differences appeared in the return or delay of subsequent menstrual periods between the groups.

The most common adverse events (reported by more than 5% of participants in both groups) included fatigue or weakness, nausea, lower abdominal pain, dizziness, and headache.

The choice of piroxicam as the COX inhibitor in conjunction with levonorgestrel for the current study had several potential advantages, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These advantages include the widespread availability and long-acting characteristics of piroxicam, which is also true of levonorgestrel, they said.