User login

ACC/AHA issue clinical lexicon for complications of COVID-19

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have jointly issued a comprehensive set of data standards to help clarify definitions of the cardiovascular (CV) and non-CV complications of COVID-19.

It’s the work of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards and has been endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions.

There is increased importance to understanding the acute and long-term impact of COVID-19 on CV health, the writing group notes. Until now, however, there has not been “clarity or consensus” on definitions of CV conditions related to COVID-19, with different diagnostic terminologies being used for overlapping conditions, such as “myocardial injury,” “myocarditis,” “type Il myocardial infarction,” “stress cardiomyopathy,” and “inflammatory cardiomyopathy,” they point out.

“We, as a research community, did some things right and some things wrong surrounding the COVID pandemic,” Sandeep Das, MD, MPH, vice chair of the writing group, noted in an interview with this news organization.

“The things that we really did right is that everybody responded with enthusiasm, kind of all hands on deck with a massive crisis response, and that was fantastic,” Dr. Das said.

“However, because of the need to hurry, we didn’t structure and organize in the way that we typically would for something that was sort of a slow burn kind of problem rather than an emergency. One of the consequences of that was fragmentation of how things are collected, reported, et cetera, and that leads to confusion,” he added.

The report was published simultaneously June 23 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

A necessary but not glamorous project

The new data standards for COVID-19 will help standardize definitions and set the framework to capture and better understand how COVID-19 affects CV health.

“It wasn’t exactly a glamorous-type project but, at the same time, it’s super necessary to kind of get everybody on the same page and working together,” Dr. Das said.

Broad agreement on common vocabulary and definitions will help with efforts to pool or compare data from electronic health records, clinical registries, administrative datasets, and other databases, and determine whether these data apply to clinical practice and research endeavors, the writing group says.

They considered data elements relevant to the full range of care provided to COVID-19 patients in all care settings. Among the key items included in the document are:

- Case definitions for confirmed, probable, and suspected acute COVID-19, as well as postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

- Definitions for acute CV complications related to COVID-19, including acute myocardial injury, heart failure, shock, arrhythmia, thromboembolic complications, and .

- Data elements related to COVID-19 vaccination status, comorbidities, and preexisting CV conditions.

- Definitions for postacute CV sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long-term CV complications of COVID-19.

- Data elements for CV mortality during acute COVID-19.

- Data elements for non-CV complications to help document severity of illness and other competing diagnoses and complications that might affect CV outcomes.

- A list of symptoms and signs related to COVID-19 and CV complications.

- Data elements for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and CV conditions.

- A discussion of advanced therapies, including , extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and end-of-life management strategies.

These data standards will be useful for researchers, registry developers, and clinicians, and they are proposed as a framework for ICD-10 code development of COVID-19–related CV conditions, the writing group says.

The standards are also of “great importance” to patients, clinicians, investigators, scientists, administrators, public health officials, policymakers, and payers, the group says.

Dr. Das said that, although there is no formal plan in place to update the document, he could see sections that might be refined.

“For example, there’s a nice long list of all the various variants, and unfortunately, I suspect that that is going to change and evolve over time,” Dr. Das told this news organization.

“We tried very hard not to include things like specifying specific treatments so we didn’t get proscriptive. We wanted to make it descriptive, so hopefully it will stand the test of time pretty well,” he added.

This research had no commercial funding. The writing group has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have jointly issued a comprehensive set of data standards to help clarify definitions of the cardiovascular (CV) and non-CV complications of COVID-19.

It’s the work of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards and has been endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions.

There is increased importance to understanding the acute and long-term impact of COVID-19 on CV health, the writing group notes. Until now, however, there has not been “clarity or consensus” on definitions of CV conditions related to COVID-19, with different diagnostic terminologies being used for overlapping conditions, such as “myocardial injury,” “myocarditis,” “type Il myocardial infarction,” “stress cardiomyopathy,” and “inflammatory cardiomyopathy,” they point out.

“We, as a research community, did some things right and some things wrong surrounding the COVID pandemic,” Sandeep Das, MD, MPH, vice chair of the writing group, noted in an interview with this news organization.

“The things that we really did right is that everybody responded with enthusiasm, kind of all hands on deck with a massive crisis response, and that was fantastic,” Dr. Das said.

“However, because of the need to hurry, we didn’t structure and organize in the way that we typically would for something that was sort of a slow burn kind of problem rather than an emergency. One of the consequences of that was fragmentation of how things are collected, reported, et cetera, and that leads to confusion,” he added.

The report was published simultaneously June 23 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

A necessary but not glamorous project

The new data standards for COVID-19 will help standardize definitions and set the framework to capture and better understand how COVID-19 affects CV health.

“It wasn’t exactly a glamorous-type project but, at the same time, it’s super necessary to kind of get everybody on the same page and working together,” Dr. Das said.

Broad agreement on common vocabulary and definitions will help with efforts to pool or compare data from electronic health records, clinical registries, administrative datasets, and other databases, and determine whether these data apply to clinical practice and research endeavors, the writing group says.

They considered data elements relevant to the full range of care provided to COVID-19 patients in all care settings. Among the key items included in the document are:

- Case definitions for confirmed, probable, and suspected acute COVID-19, as well as postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

- Definitions for acute CV complications related to COVID-19, including acute myocardial injury, heart failure, shock, arrhythmia, thromboembolic complications, and .

- Data elements related to COVID-19 vaccination status, comorbidities, and preexisting CV conditions.

- Definitions for postacute CV sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long-term CV complications of COVID-19.

- Data elements for CV mortality during acute COVID-19.

- Data elements for non-CV complications to help document severity of illness and other competing diagnoses and complications that might affect CV outcomes.

- A list of symptoms and signs related to COVID-19 and CV complications.

- Data elements for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and CV conditions.

- A discussion of advanced therapies, including , extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and end-of-life management strategies.

These data standards will be useful for researchers, registry developers, and clinicians, and they are proposed as a framework for ICD-10 code development of COVID-19–related CV conditions, the writing group says.

The standards are also of “great importance” to patients, clinicians, investigators, scientists, administrators, public health officials, policymakers, and payers, the group says.

Dr. Das said that, although there is no formal plan in place to update the document, he could see sections that might be refined.

“For example, there’s a nice long list of all the various variants, and unfortunately, I suspect that that is going to change and evolve over time,” Dr. Das told this news organization.

“We tried very hard not to include things like specifying specific treatments so we didn’t get proscriptive. We wanted to make it descriptive, so hopefully it will stand the test of time pretty well,” he added.

This research had no commercial funding. The writing group has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have jointly issued a comprehensive set of data standards to help clarify definitions of the cardiovascular (CV) and non-CV complications of COVID-19.

It’s the work of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards and has been endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions.

There is increased importance to understanding the acute and long-term impact of COVID-19 on CV health, the writing group notes. Until now, however, there has not been “clarity or consensus” on definitions of CV conditions related to COVID-19, with different diagnostic terminologies being used for overlapping conditions, such as “myocardial injury,” “myocarditis,” “type Il myocardial infarction,” “stress cardiomyopathy,” and “inflammatory cardiomyopathy,” they point out.

“We, as a research community, did some things right and some things wrong surrounding the COVID pandemic,” Sandeep Das, MD, MPH, vice chair of the writing group, noted in an interview with this news organization.

“The things that we really did right is that everybody responded with enthusiasm, kind of all hands on deck with a massive crisis response, and that was fantastic,” Dr. Das said.

“However, because of the need to hurry, we didn’t structure and organize in the way that we typically would for something that was sort of a slow burn kind of problem rather than an emergency. One of the consequences of that was fragmentation of how things are collected, reported, et cetera, and that leads to confusion,” he added.

The report was published simultaneously June 23 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

A necessary but not glamorous project

The new data standards for COVID-19 will help standardize definitions and set the framework to capture and better understand how COVID-19 affects CV health.

“It wasn’t exactly a glamorous-type project but, at the same time, it’s super necessary to kind of get everybody on the same page and working together,” Dr. Das said.

Broad agreement on common vocabulary and definitions will help with efforts to pool or compare data from electronic health records, clinical registries, administrative datasets, and other databases, and determine whether these data apply to clinical practice and research endeavors, the writing group says.

They considered data elements relevant to the full range of care provided to COVID-19 patients in all care settings. Among the key items included in the document are:

- Case definitions for confirmed, probable, and suspected acute COVID-19, as well as postacute sequelae of COVID-19.

- Definitions for acute CV complications related to COVID-19, including acute myocardial injury, heart failure, shock, arrhythmia, thromboembolic complications, and .

- Data elements related to COVID-19 vaccination status, comorbidities, and preexisting CV conditions.

- Definitions for postacute CV sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long-term CV complications of COVID-19.

- Data elements for CV mortality during acute COVID-19.

- Data elements for non-CV complications to help document severity of illness and other competing diagnoses and complications that might affect CV outcomes.

- A list of symptoms and signs related to COVID-19 and CV complications.

- Data elements for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19 and CV conditions.

- A discussion of advanced therapies, including , extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and end-of-life management strategies.

These data standards will be useful for researchers, registry developers, and clinicians, and they are proposed as a framework for ICD-10 code development of COVID-19–related CV conditions, the writing group says.

The standards are also of “great importance” to patients, clinicians, investigators, scientists, administrators, public health officials, policymakers, and payers, the group says.

Dr. Das said that, although there is no formal plan in place to update the document, he could see sections that might be refined.

“For example, there’s a nice long list of all the various variants, and unfortunately, I suspect that that is going to change and evolve over time,” Dr. Das told this news organization.

“We tried very hard not to include things like specifying specific treatments so we didn’t get proscriptive. We wanted to make it descriptive, so hopefully it will stand the test of time pretty well,” he added.

This research had no commercial funding. The writing group has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 Pandemic stress affected ovulation, not menstruation

ATLANTA – Disturbances in ovulation that didn’t produce any actual changes in the menstrual cycle of women were extremely common during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and were linked to emotional stress, according to the findings of an “experiment of nature” that allowed for comparison with women a decade earlier.

Findings from two studies of reproductive-age women, one conducted in 2006-2008 and the other in 2020-2021, were presented by Jerilynn C. Prior, MD, at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The comparison of the two time periods yielded several novel findings. “I was taught in medical school that when women don’t eat enough they lose their period. But what we now understand is there’s a graded response to various stressors, acting through the hypothalamus in a common pathway. There is a gradation of disturbances, some of which are subclinical or not obvious,” said Dr. Prior, professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Moreover, women’s menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ across the two time periods, despite a dramatic 63% decrement in normal ovulatory function related to increased depression, anxiety, and outside stresses that the women reported in diaries.

“Assuming that regular cycles need normal ovulation is something we should just get out of our minds. It changes our concept about what’s normal if we only know about the cycle length,” she observed.

It will be critical going forward to see whether the ovulatory disturbances have resolved as the pandemic has shifted “because there’s strong evidence that ovulatory disturbances, even with normal cycle length, are related to bone loss and some evidence it’s related to early heart attacks, breast and endometrial cancers,” Dr. Prior said during a press conference.

Asked to comment, session moderator Genevieve Neal-Perry, MD, PhD, told this news organization: “I think what we can take away is that stress itself is a modifier of the way the brain and the gonads communicate with each other, and that then has an impact on ovulatory function.”

Dr. Neal-Perry noted that the association of stress and ovulatory disruption has been reported in various ways previously, but “clearly it doesn’t affect everyone. What we don’t know is who is most susceptible. There have been some studies showing a genetic predisposition and a genetic anomaly that actually makes them more susceptible to the impact of stress on the reproductive system.”

But the lack of data on weight change in the study cohorts is a limitation. “To me one of the more important questions was what was going on with weight. Just looking at a static number doesn’t tell you whether there were changes. We know that weight gain or weight loss can stress the reproductive axis,” noted Dr. Neal-Parry of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

‘Experiment of nature’ revealed invisible effect of pandemic stress

The women in both cohorts of the Menstruation Ovulation Study (MOS) were healthy volunteers aged 19-35 years recruited from the metropolitan Vancouver region. All were menstruating monthly and none were taking hormonal birth control. Recruitment for the second cohort had begun just prior to the March 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Interviewer-administered questionnaires (CaMos) covering demographics, socioeconomic status, and reproductive history, and daily diaries kept by the women (menstrual cycle diary) were identical for both cohorts.

Assessments of ovulation differed for the two studies but were cross-validated. For the earlier time period, ovulation was assessed by a threefold increase in follicular-to-luteal urinary progesterone (PdG). For the pandemic-era study, the validated quantitative basal temperature (QBT) method was used.

There were 301 women in the earlier cohort and 125 during the pandemic. Both were an average age of about 29 years and had a body mass index of about 24.3 kg/m2 (within the normal range). The pandemic cohort was more racially/ethnically diverse than the earlier one and more in-line with recent census data.

More of the women were nulliparous during the pandemic than earlier (92.7% vs. 80.4%; P = .002).

The distribution of menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ, with both cohorts averaging about 30 days (P = .893). However, while 90% of the women in the earlier cohort ovulated normally, only 37% did during the pandemic, a highly significant difference (P < .0001).

Thus, during the pandemic, 63% of women had “silent ovulatory disturbances,” either with short luteal phases after ovulation or no ovulation, compared with just 10% in the earlier cohort, “which is remarkable, unbelievable actually,” Dr. Prior remarked.

The difference wasn’t explained by any of the demographic information collected either, including socioeconomic status, lifestyle, or reproductive history variables.

And it wasn’t because of COVID-19 vaccination, as the vaccine wasn’t available when most of the women were recruited, and of the 79 who were recruited during vaccine availability, only two received a COVID-19 vaccine during the study (and both had normal ovulation).

Employment changes, caring responsibilities, and worry likely causes

The information from the diaries was more revealing. Several diary components were far more common during the pandemic, including negative mood (feeling depressed or anxious, sleep problems, and outside stresses), self-worth, interest in sex, energy level, and appetite. All were significantly different between the two cohorts (P < .001) and between those with and without ovulatory disturbances.

“So menstrual cycle lengths and long cycles didn’t differ, but there was a much higher prevalence of silent or subclinical ovulatory disturbances, and these were related to the increased stresses that women recorded in their diaries. This means that the estrogen levels were pretty close to normal but the progesterone levels were remarkably decreased,” Dr. Prior said.

Interestingly, reported menstrual cramps were also significantly more common during the pandemic and associated with ovulatory disruption.

“That is a new observation because previously we’ve always thought that you needed to ovulate in order to even have cramps,” she commented.

Asked whether COVID-19 itself might have played a role, Dr. Prior said no woman in the study tested positive for the virus or had long COVID.

“As far as I’m aware, it was the changes in employment … and caring for elders and worry about illness in somebody you loved that was related,” she said.

Asked what she thinks the result would be if the study were conducted now, she said: “I don’t know. We’re still in a stressful time with inflation and not complete recovery, so probably the issue is still very present.”

Dr. Prior and Dr. Neal-Perry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ATLANTA – Disturbances in ovulation that didn’t produce any actual changes in the menstrual cycle of women were extremely common during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and were linked to emotional stress, according to the findings of an “experiment of nature” that allowed for comparison with women a decade earlier.

Findings from two studies of reproductive-age women, one conducted in 2006-2008 and the other in 2020-2021, were presented by Jerilynn C. Prior, MD, at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The comparison of the two time periods yielded several novel findings. “I was taught in medical school that when women don’t eat enough they lose their period. But what we now understand is there’s a graded response to various stressors, acting through the hypothalamus in a common pathway. There is a gradation of disturbances, some of which are subclinical or not obvious,” said Dr. Prior, professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Moreover, women’s menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ across the two time periods, despite a dramatic 63% decrement in normal ovulatory function related to increased depression, anxiety, and outside stresses that the women reported in diaries.

“Assuming that regular cycles need normal ovulation is something we should just get out of our minds. It changes our concept about what’s normal if we only know about the cycle length,” she observed.

It will be critical going forward to see whether the ovulatory disturbances have resolved as the pandemic has shifted “because there’s strong evidence that ovulatory disturbances, even with normal cycle length, are related to bone loss and some evidence it’s related to early heart attacks, breast and endometrial cancers,” Dr. Prior said during a press conference.

Asked to comment, session moderator Genevieve Neal-Perry, MD, PhD, told this news organization: “I think what we can take away is that stress itself is a modifier of the way the brain and the gonads communicate with each other, and that then has an impact on ovulatory function.”

Dr. Neal-Perry noted that the association of stress and ovulatory disruption has been reported in various ways previously, but “clearly it doesn’t affect everyone. What we don’t know is who is most susceptible. There have been some studies showing a genetic predisposition and a genetic anomaly that actually makes them more susceptible to the impact of stress on the reproductive system.”

But the lack of data on weight change in the study cohorts is a limitation. “To me one of the more important questions was what was going on with weight. Just looking at a static number doesn’t tell you whether there were changes. We know that weight gain or weight loss can stress the reproductive axis,” noted Dr. Neal-Parry of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

‘Experiment of nature’ revealed invisible effect of pandemic stress

The women in both cohorts of the Menstruation Ovulation Study (MOS) were healthy volunteers aged 19-35 years recruited from the metropolitan Vancouver region. All were menstruating monthly and none were taking hormonal birth control. Recruitment for the second cohort had begun just prior to the March 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Interviewer-administered questionnaires (CaMos) covering demographics, socioeconomic status, and reproductive history, and daily diaries kept by the women (menstrual cycle diary) were identical for both cohorts.

Assessments of ovulation differed for the two studies but were cross-validated. For the earlier time period, ovulation was assessed by a threefold increase in follicular-to-luteal urinary progesterone (PdG). For the pandemic-era study, the validated quantitative basal temperature (QBT) method was used.

There were 301 women in the earlier cohort and 125 during the pandemic. Both were an average age of about 29 years and had a body mass index of about 24.3 kg/m2 (within the normal range). The pandemic cohort was more racially/ethnically diverse than the earlier one and more in-line with recent census data.

More of the women were nulliparous during the pandemic than earlier (92.7% vs. 80.4%; P = .002).

The distribution of menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ, with both cohorts averaging about 30 days (P = .893). However, while 90% of the women in the earlier cohort ovulated normally, only 37% did during the pandemic, a highly significant difference (P < .0001).

Thus, during the pandemic, 63% of women had “silent ovulatory disturbances,” either with short luteal phases after ovulation or no ovulation, compared with just 10% in the earlier cohort, “which is remarkable, unbelievable actually,” Dr. Prior remarked.

The difference wasn’t explained by any of the demographic information collected either, including socioeconomic status, lifestyle, or reproductive history variables.

And it wasn’t because of COVID-19 vaccination, as the vaccine wasn’t available when most of the women were recruited, and of the 79 who were recruited during vaccine availability, only two received a COVID-19 vaccine during the study (and both had normal ovulation).

Employment changes, caring responsibilities, and worry likely causes

The information from the diaries was more revealing. Several diary components were far more common during the pandemic, including negative mood (feeling depressed or anxious, sleep problems, and outside stresses), self-worth, interest in sex, energy level, and appetite. All were significantly different between the two cohorts (P < .001) and between those with and without ovulatory disturbances.

“So menstrual cycle lengths and long cycles didn’t differ, but there was a much higher prevalence of silent or subclinical ovulatory disturbances, and these were related to the increased stresses that women recorded in their diaries. This means that the estrogen levels were pretty close to normal but the progesterone levels were remarkably decreased,” Dr. Prior said.

Interestingly, reported menstrual cramps were also significantly more common during the pandemic and associated with ovulatory disruption.

“That is a new observation because previously we’ve always thought that you needed to ovulate in order to even have cramps,” she commented.

Asked whether COVID-19 itself might have played a role, Dr. Prior said no woman in the study tested positive for the virus or had long COVID.

“As far as I’m aware, it was the changes in employment … and caring for elders and worry about illness in somebody you loved that was related,” she said.

Asked what she thinks the result would be if the study were conducted now, she said: “I don’t know. We’re still in a stressful time with inflation and not complete recovery, so probably the issue is still very present.”

Dr. Prior and Dr. Neal-Perry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ATLANTA – Disturbances in ovulation that didn’t produce any actual changes in the menstrual cycle of women were extremely common during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and were linked to emotional stress, according to the findings of an “experiment of nature” that allowed for comparison with women a decade earlier.

Findings from two studies of reproductive-age women, one conducted in 2006-2008 and the other in 2020-2021, were presented by Jerilynn C. Prior, MD, at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

The comparison of the two time periods yielded several novel findings. “I was taught in medical school that when women don’t eat enough they lose their period. But what we now understand is there’s a graded response to various stressors, acting through the hypothalamus in a common pathway. There is a gradation of disturbances, some of which are subclinical or not obvious,” said Dr. Prior, professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Moreover, women’s menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ across the two time periods, despite a dramatic 63% decrement in normal ovulatory function related to increased depression, anxiety, and outside stresses that the women reported in diaries.

“Assuming that regular cycles need normal ovulation is something we should just get out of our minds. It changes our concept about what’s normal if we only know about the cycle length,” she observed.

It will be critical going forward to see whether the ovulatory disturbances have resolved as the pandemic has shifted “because there’s strong evidence that ovulatory disturbances, even with normal cycle length, are related to bone loss and some evidence it’s related to early heart attacks, breast and endometrial cancers,” Dr. Prior said during a press conference.

Asked to comment, session moderator Genevieve Neal-Perry, MD, PhD, told this news organization: “I think what we can take away is that stress itself is a modifier of the way the brain and the gonads communicate with each other, and that then has an impact on ovulatory function.”

Dr. Neal-Perry noted that the association of stress and ovulatory disruption has been reported in various ways previously, but “clearly it doesn’t affect everyone. What we don’t know is who is most susceptible. There have been some studies showing a genetic predisposition and a genetic anomaly that actually makes them more susceptible to the impact of stress on the reproductive system.”

But the lack of data on weight change in the study cohorts is a limitation. “To me one of the more important questions was what was going on with weight. Just looking at a static number doesn’t tell you whether there were changes. We know that weight gain or weight loss can stress the reproductive axis,” noted Dr. Neal-Parry of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

‘Experiment of nature’ revealed invisible effect of pandemic stress

The women in both cohorts of the Menstruation Ovulation Study (MOS) were healthy volunteers aged 19-35 years recruited from the metropolitan Vancouver region. All were menstruating monthly and none were taking hormonal birth control. Recruitment for the second cohort had begun just prior to the March 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Interviewer-administered questionnaires (CaMos) covering demographics, socioeconomic status, and reproductive history, and daily diaries kept by the women (menstrual cycle diary) were identical for both cohorts.

Assessments of ovulation differed for the two studies but were cross-validated. For the earlier time period, ovulation was assessed by a threefold increase in follicular-to-luteal urinary progesterone (PdG). For the pandemic-era study, the validated quantitative basal temperature (QBT) method was used.

There were 301 women in the earlier cohort and 125 during the pandemic. Both were an average age of about 29 years and had a body mass index of about 24.3 kg/m2 (within the normal range). The pandemic cohort was more racially/ethnically diverse than the earlier one and more in-line with recent census data.

More of the women were nulliparous during the pandemic than earlier (92.7% vs. 80.4%; P = .002).

The distribution of menstrual cycle lengths didn’t differ, with both cohorts averaging about 30 days (P = .893). However, while 90% of the women in the earlier cohort ovulated normally, only 37% did during the pandemic, a highly significant difference (P < .0001).

Thus, during the pandemic, 63% of women had “silent ovulatory disturbances,” either with short luteal phases after ovulation or no ovulation, compared with just 10% in the earlier cohort, “which is remarkable, unbelievable actually,” Dr. Prior remarked.

The difference wasn’t explained by any of the demographic information collected either, including socioeconomic status, lifestyle, or reproductive history variables.

And it wasn’t because of COVID-19 vaccination, as the vaccine wasn’t available when most of the women were recruited, and of the 79 who were recruited during vaccine availability, only two received a COVID-19 vaccine during the study (and both had normal ovulation).

Employment changes, caring responsibilities, and worry likely causes

The information from the diaries was more revealing. Several diary components were far more common during the pandemic, including negative mood (feeling depressed or anxious, sleep problems, and outside stresses), self-worth, interest in sex, energy level, and appetite. All were significantly different between the two cohorts (P < .001) and between those with and without ovulatory disturbances.

“So menstrual cycle lengths and long cycles didn’t differ, but there was a much higher prevalence of silent or subclinical ovulatory disturbances, and these were related to the increased stresses that women recorded in their diaries. This means that the estrogen levels were pretty close to normal but the progesterone levels were remarkably decreased,” Dr. Prior said.

Interestingly, reported menstrual cramps were also significantly more common during the pandemic and associated with ovulatory disruption.

“That is a new observation because previously we’ve always thought that you needed to ovulate in order to even have cramps,” she commented.

Asked whether COVID-19 itself might have played a role, Dr. Prior said no woman in the study tested positive for the virus or had long COVID.

“As far as I’m aware, it was the changes in employment … and caring for elders and worry about illness in somebody you loved that was related,” she said.

Asked what she thinks the result would be if the study were conducted now, she said: “I don’t know. We’re still in a stressful time with inflation and not complete recovery, so probably the issue is still very present.”

Dr. Prior and Dr. Neal-Perry have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ENDO 2022

How to communicate effectively with patients when tension is high

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

Who doesn’t text in 2022? Most state Medicaid programs

West Virginia will use the U.S. Postal Service and an online account in the summer of 2022 to connect with Medicaid enrollees about the expected end of the COVID public health emergency, which will put many recipients at risk of losing their coverage.

What West Virginia won’t do is use a form of communication that’s ubiquitous worldwide: text messaging.

“West Virginia isn’t set up to text its members,” Allison Adler, the state’s Medicaid spokesperson, wrote to KHN in an email.

Indeed, most states’ Medicaid programs won’t text enrollees despite the urgency to reach them about renewing their coverage. A KFF report published in March found just 11 states said they would use texting to alert Medicaid recipients about the end of the COVID public health emergency. In contrast, 33 states plan to use snail mail and at least 20 will reach out with individual or automated phone calls.

“It doesn’t make any sense when texting is how most people communicate today,” said Kinda Serafi, a partner with the consulting firm Manatt Health.

State Medicaid agencies for months have been preparing for the end of the public health emergency. As part of a COVID relief law approved in March 2020, Congress prohibited states from dropping anyone from Medicaid coverage unless they moved out of state during the public health emergency. When the emergency ends, state Medicaid officials must reevaluate each enrollee’s eligibility. Millions of people could lose their coverage if they earn too much or fail to provide the information needed to verify income or residency.

As of November, about 86 million people were enrolled in Medicaid, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. That’s up from 71 million in February 2020, before COVID began to ravage the nation.

West Virginia has more than 600,000 Medicaid enrollees. Adler said about 100,000 of them could lose their eligibility at the end of the public health emergency because either the state has determined they’re ineligible or they’ve failed to respond to requests that they update their income information.

“It’s frustrating that texting is a means to meet people where they are and that this has not been picked up more by states,” said Jennifer Wagner, director of Medicaid eligibility and enrollment for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based research group.

The problem with relying on the Postal Service is that a letter can get hidden in “junk” mail or can fail to reach people who have moved or are homeless, Ms. Serafi said. And email, if people have an account, can end up in spam folders.

In contrast, surveys show lower-income Americans are just as likely to have smartphones and cellphones as the general population. And most people regularly use texting.

In Michigan, Medicaid officials started using text messaging to communicate with enrollees in 2020 after building a system with the help of federal COVID relief funding. They said texting is an economical way to reach enrollees.

“It costs us 2 cents per text message, which is incredibly cheap,” said Steph White, an enrollment coordinator for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. “It’s a great return on investment.”

CMS officials have told states they should consider texting, along with other communication methods, when trying to reach enrollees when the public health emergency ends. But many states don’t have the technology or information about enrollees to do it.

Efforts to add texting also face legal barriers, including a federal law that bars texting people without their consent. The Federal Communications Commission ruled in 2021 that state agencies are exempt from the law, but whether counties that handle Medicaid duties for some states and Medicaid managed-care organizations that work in more than 40 states are exempt as well is unclear, said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

CMS spokesperson Beth Lynk said the agency is trying to figure out how Medicaid agencies, counties, and health plans can text enrollees within the constraints of federal law.

Several states told KHN that Medicaid health plans will be helping connect with enrollees and that they expect the plans to use text messaging. But the requirement to get consent from enrollees before texting could limit that effort.

That’s the situation in Virginia, where only about 30,000 Medicaid enrollees – out of more than a million – have agreed to receive text messages directly from the state, said spokesperson Christina Nuckols.

In an effort to boost that number, the state plans to ask enrollees if they want to opt out of receiving text messages, rather than ask them to opt in, she said. This way enrollees would contact the state only if they don’t want to be texted. The state is reviewing its legal options to make that happen.

Meanwhile, Ms. Nuckols added, the state expects Medicaid health plans to contact enrollees about updating their contact information. Four of Virginia’s six Medicaid plans, which serve the bulk of the state’s enrollees, have permission to text about 316,000.

Craig Kennedy, CEO of Medicaid Health Plans of America, a trade group, said that most plans are using texting and that Medicaid officials will use multiple strategies to connect with enrollees. “I do not see this as a detriment, that states are not texting information about reenrollment,” he said. “I know we will be helping with that.”

California officials in March directed Medicaid health plans to use a variety of communication methods, including texting, to ensure that members can retain coverage if they remain eligible. The officials told health plans they could ask for consent through an initial text.

California officials say they also plan to ask enrollees for consent to be texted on the enrollment application, although federal approval for the change is not expected until the fall.

A few state Medicaid programs have experimented in recent years with pilot programs that included texting enrollees.

In 2019, Louisiana worked with the nonprofit group Code for America to send text messages that reminded people about renewing coverage and providing income information for verification. Compared with traditional communication methods, the texts led to a 67% increase in enrollees being renewed for coverage and a 56% increase in enrollees verifying their income in response to inquiries, said Medicaid spokesperson Alyson Neel.

Nonetheless, the state isn’t planning to text Medicaid enrollees about the end of the public health emergency because it hasn’t set up a system for that. “Medicaid has not yet been able to implement a text messaging system of its own due to other agency priorities,” Ms. Neel said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

West Virginia will use the U.S. Postal Service and an online account in the summer of 2022 to connect with Medicaid enrollees about the expected end of the COVID public health emergency, which will put many recipients at risk of losing their coverage.

What West Virginia won’t do is use a form of communication that’s ubiquitous worldwide: text messaging.

“West Virginia isn’t set up to text its members,” Allison Adler, the state’s Medicaid spokesperson, wrote to KHN in an email.

Indeed, most states’ Medicaid programs won’t text enrollees despite the urgency to reach them about renewing their coverage. A KFF report published in March found just 11 states said they would use texting to alert Medicaid recipients about the end of the COVID public health emergency. In contrast, 33 states plan to use snail mail and at least 20 will reach out with individual or automated phone calls.

“It doesn’t make any sense when texting is how most people communicate today,” said Kinda Serafi, a partner with the consulting firm Manatt Health.

State Medicaid agencies for months have been preparing for the end of the public health emergency. As part of a COVID relief law approved in March 2020, Congress prohibited states from dropping anyone from Medicaid coverage unless they moved out of state during the public health emergency. When the emergency ends, state Medicaid officials must reevaluate each enrollee’s eligibility. Millions of people could lose their coverage if they earn too much or fail to provide the information needed to verify income or residency.

As of November, about 86 million people were enrolled in Medicaid, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. That’s up from 71 million in February 2020, before COVID began to ravage the nation.

West Virginia has more than 600,000 Medicaid enrollees. Adler said about 100,000 of them could lose their eligibility at the end of the public health emergency because either the state has determined they’re ineligible or they’ve failed to respond to requests that they update their income information.

“It’s frustrating that texting is a means to meet people where they are and that this has not been picked up more by states,” said Jennifer Wagner, director of Medicaid eligibility and enrollment for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based research group.

The problem with relying on the Postal Service is that a letter can get hidden in “junk” mail or can fail to reach people who have moved or are homeless, Ms. Serafi said. And email, if people have an account, can end up in spam folders.

In contrast, surveys show lower-income Americans are just as likely to have smartphones and cellphones as the general population. And most people regularly use texting.

In Michigan, Medicaid officials started using text messaging to communicate with enrollees in 2020 after building a system with the help of federal COVID relief funding. They said texting is an economical way to reach enrollees.

“It costs us 2 cents per text message, which is incredibly cheap,” said Steph White, an enrollment coordinator for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. “It’s a great return on investment.”

CMS officials have told states they should consider texting, along with other communication methods, when trying to reach enrollees when the public health emergency ends. But many states don’t have the technology or information about enrollees to do it.

Efforts to add texting also face legal barriers, including a federal law that bars texting people without their consent. The Federal Communications Commission ruled in 2021 that state agencies are exempt from the law, but whether counties that handle Medicaid duties for some states and Medicaid managed-care organizations that work in more than 40 states are exempt as well is unclear, said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

CMS spokesperson Beth Lynk said the agency is trying to figure out how Medicaid agencies, counties, and health plans can text enrollees within the constraints of federal law.

Several states told KHN that Medicaid health plans will be helping connect with enrollees and that they expect the plans to use text messaging. But the requirement to get consent from enrollees before texting could limit that effort.

That’s the situation in Virginia, where only about 30,000 Medicaid enrollees – out of more than a million – have agreed to receive text messages directly from the state, said spokesperson Christina Nuckols.

In an effort to boost that number, the state plans to ask enrollees if they want to opt out of receiving text messages, rather than ask them to opt in, she said. This way enrollees would contact the state only if they don’t want to be texted. The state is reviewing its legal options to make that happen.

Meanwhile, Ms. Nuckols added, the state expects Medicaid health plans to contact enrollees about updating their contact information. Four of Virginia’s six Medicaid plans, which serve the bulk of the state’s enrollees, have permission to text about 316,000.

Craig Kennedy, CEO of Medicaid Health Plans of America, a trade group, said that most plans are using texting and that Medicaid officials will use multiple strategies to connect with enrollees. “I do not see this as a detriment, that states are not texting information about reenrollment,” he said. “I know we will be helping with that.”

California officials in March directed Medicaid health plans to use a variety of communication methods, including texting, to ensure that members can retain coverage if they remain eligible. The officials told health plans they could ask for consent through an initial text.

California officials say they also plan to ask enrollees for consent to be texted on the enrollment application, although federal approval for the change is not expected until the fall.

A few state Medicaid programs have experimented in recent years with pilot programs that included texting enrollees.

In 2019, Louisiana worked with the nonprofit group Code for America to send text messages that reminded people about renewing coverage and providing income information for verification. Compared with traditional communication methods, the texts led to a 67% increase in enrollees being renewed for coverage and a 56% increase in enrollees verifying their income in response to inquiries, said Medicaid spokesperson Alyson Neel.

Nonetheless, the state isn’t planning to text Medicaid enrollees about the end of the public health emergency because it hasn’t set up a system for that. “Medicaid has not yet been able to implement a text messaging system of its own due to other agency priorities,” Ms. Neel said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

West Virginia will use the U.S. Postal Service and an online account in the summer of 2022 to connect with Medicaid enrollees about the expected end of the COVID public health emergency, which will put many recipients at risk of losing their coverage.

What West Virginia won’t do is use a form of communication that’s ubiquitous worldwide: text messaging.

“West Virginia isn’t set up to text its members,” Allison Adler, the state’s Medicaid spokesperson, wrote to KHN in an email.

Indeed, most states’ Medicaid programs won’t text enrollees despite the urgency to reach them about renewing their coverage. A KFF report published in March found just 11 states said they would use texting to alert Medicaid recipients about the end of the COVID public health emergency. In contrast, 33 states plan to use snail mail and at least 20 will reach out with individual or automated phone calls.

“It doesn’t make any sense when texting is how most people communicate today,” said Kinda Serafi, a partner with the consulting firm Manatt Health.

State Medicaid agencies for months have been preparing for the end of the public health emergency. As part of a COVID relief law approved in March 2020, Congress prohibited states from dropping anyone from Medicaid coverage unless they moved out of state during the public health emergency. When the emergency ends, state Medicaid officials must reevaluate each enrollee’s eligibility. Millions of people could lose their coverage if they earn too much or fail to provide the information needed to verify income or residency.

As of November, about 86 million people were enrolled in Medicaid, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. That’s up from 71 million in February 2020, before COVID began to ravage the nation.

West Virginia has more than 600,000 Medicaid enrollees. Adler said about 100,000 of them could lose their eligibility at the end of the public health emergency because either the state has determined they’re ineligible or they’ve failed to respond to requests that they update their income information.

“It’s frustrating that texting is a means to meet people where they are and that this has not been picked up more by states,” said Jennifer Wagner, director of Medicaid eligibility and enrollment for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington-based research group.

The problem with relying on the Postal Service is that a letter can get hidden in “junk” mail or can fail to reach people who have moved or are homeless, Ms. Serafi said. And email, if people have an account, can end up in spam folders.

In contrast, surveys show lower-income Americans are just as likely to have smartphones and cellphones as the general population. And most people regularly use texting.

In Michigan, Medicaid officials started using text messaging to communicate with enrollees in 2020 after building a system with the help of federal COVID relief funding. They said texting is an economical way to reach enrollees.

“It costs us 2 cents per text message, which is incredibly cheap,” said Steph White, an enrollment coordinator for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. “It’s a great return on investment.”

CMS officials have told states they should consider texting, along with other communication methods, when trying to reach enrollees when the public health emergency ends. But many states don’t have the technology or information about enrollees to do it.

Efforts to add texting also face legal barriers, including a federal law that bars texting people without their consent. The Federal Communications Commission ruled in 2021 that state agencies are exempt from the law, but whether counties that handle Medicaid duties for some states and Medicaid managed-care organizations that work in more than 40 states are exempt as well is unclear, said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

CMS spokesperson Beth Lynk said the agency is trying to figure out how Medicaid agencies, counties, and health plans can text enrollees within the constraints of federal law.

Several states told KHN that Medicaid health plans will be helping connect with enrollees and that they expect the plans to use text messaging. But the requirement to get consent from enrollees before texting could limit that effort.

That’s the situation in Virginia, where only about 30,000 Medicaid enrollees – out of more than a million – have agreed to receive text messages directly from the state, said spokesperson Christina Nuckols.

In an effort to boost that number, the state plans to ask enrollees if they want to opt out of receiving text messages, rather than ask them to opt in, she said. This way enrollees would contact the state only if they don’t want to be texted. The state is reviewing its legal options to make that happen.

Meanwhile, Ms. Nuckols added, the state expects Medicaid health plans to contact enrollees about updating their contact information. Four of Virginia’s six Medicaid plans, which serve the bulk of the state’s enrollees, have permission to text about 316,000.

Craig Kennedy, CEO of Medicaid Health Plans of America, a trade group, said that most plans are using texting and that Medicaid officials will use multiple strategies to connect with enrollees. “I do not see this as a detriment, that states are not texting information about reenrollment,” he said. “I know we will be helping with that.”

California officials in March directed Medicaid health plans to use a variety of communication methods, including texting, to ensure that members can retain coverage if they remain eligible. The officials told health plans they could ask for consent through an initial text.

California officials say they also plan to ask enrollees for consent to be texted on the enrollment application, although federal approval for the change is not expected until the fall.

A few state Medicaid programs have experimented in recent years with pilot programs that included texting enrollees.

In 2019, Louisiana worked with the nonprofit group Code for America to send text messages that reminded people about renewing coverage and providing income information for verification. Compared with traditional communication methods, the texts led to a 67% increase in enrollees being renewed for coverage and a 56% increase in enrollees verifying their income in response to inquiries, said Medicaid spokesperson Alyson Neel.

Nonetheless, the state isn’t planning to text Medicaid enrollees about the end of the public health emergency because it hasn’t set up a system for that. “Medicaid has not yet been able to implement a text messaging system of its own due to other agency priorities,” Ms. Neel said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Direct-to-Consumer Teledermatology Growth: A Review and Outlook for the Future

In recent years, direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms have gained popularity as telehealth business models, allowing patients to directly initiate visits with physicians and purchase medications from single platforms. A shortage of dermatologists, improved technology, drug patent expirations, and rising health care costs accelerated the growth of DTC dermatology.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, teledermatology adoption surged due to the need to provide care while social distancing and minimizing viral exposure. These needs prompted additional federal funding and loosened regulatory provisions.2 As the userbase of these companies has grown, so have their valuations.3 Although the DTC model has attracted the attention of patients and investors, its rise provokes many questions about patients acting as consumers in health care. Indeed, DTC telemedicine offers greater autonomy and convenience for patients, but it may impact the quality of care and the nature of physician-patient relationships, perhaps making them more transactional.

Evolution of DTC in Health Care

The DTC model emphasizes individual choice and accessible health care. Although the definition has evolved, the core idea is not new.4 Over decades, pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars on DTC advertising, circumventing physicians by directly reaching patients with campaigns on prescription drugs and laboratory tests and shaping public definitions of diseases.5

The DTC model of care is fundamentally different from traditional care models in that it changes the roles of the patient and physician. Whereas early telehealth models required a health care provider to initiate teleconsultations with specialists, DTC telemedicine bypasses this step (eg, the patient can consult a dermatologist without needing a primary care provider’s input first). This care can then be provided by dermatologists with whom patients may or may not have pre-established relationships.4,6

Dermatology was an early adopter of DTC telemedicine. The shortage of dermatologists in the United States created demand for increasing accessibility to dermatologic care. Additionally, the visual nature of diagnosing dermatologic disease was ideal for platforms supporting image sharing.7 Early DTC providers were primarily individual companies offering teledermatology. However, many dermatologists can now offer DTC capabilities via companies such as Amwell and Teladoc Health.8

Over the last 2 decades, start-ups such as Warby Parker (eyeglasses) and Casper (mattresses) defined the DTC industry using borrowed supply chains, cohesive branding, heavy social media marketing, and web-only retail. Scalability, lack of competition, and abundant venture capital created competition across numerous markets.9 Health care capitalized on this DTC model, creating a $700 billion market for products ranging from hearing aids to over-the-counter medications.10

Borrowing from this DTC playbook, platforms were created to offer delivery of generic prescription drugs to patients’ doorsteps. However, unlike with other products bought online, a consumer cannot simply add prescription drugs to their shopping cart and check out. In all models of American medical practice, physicians still serve as gatekeepers, providing a safeguard for patients to ensure appropriate prescription and avoid negative consequences of unnecessary drug use. This new model effectively streamlines diagnosis, prescription, and drug delivery without the patient ever having to leave home. Combining the prescribing and selling of medications (2 tasks that traditionally have been separated) potentially creates financial conflicts of interest (COIs). Additionally, high utilization of health care, including more prescriptions and visits, does not necessarily equal high quality of care. The companies stand to benefit from extra care regardless of need, and thus these models must be scrutinized for any incentives driving unnecessary care and prescriptions.

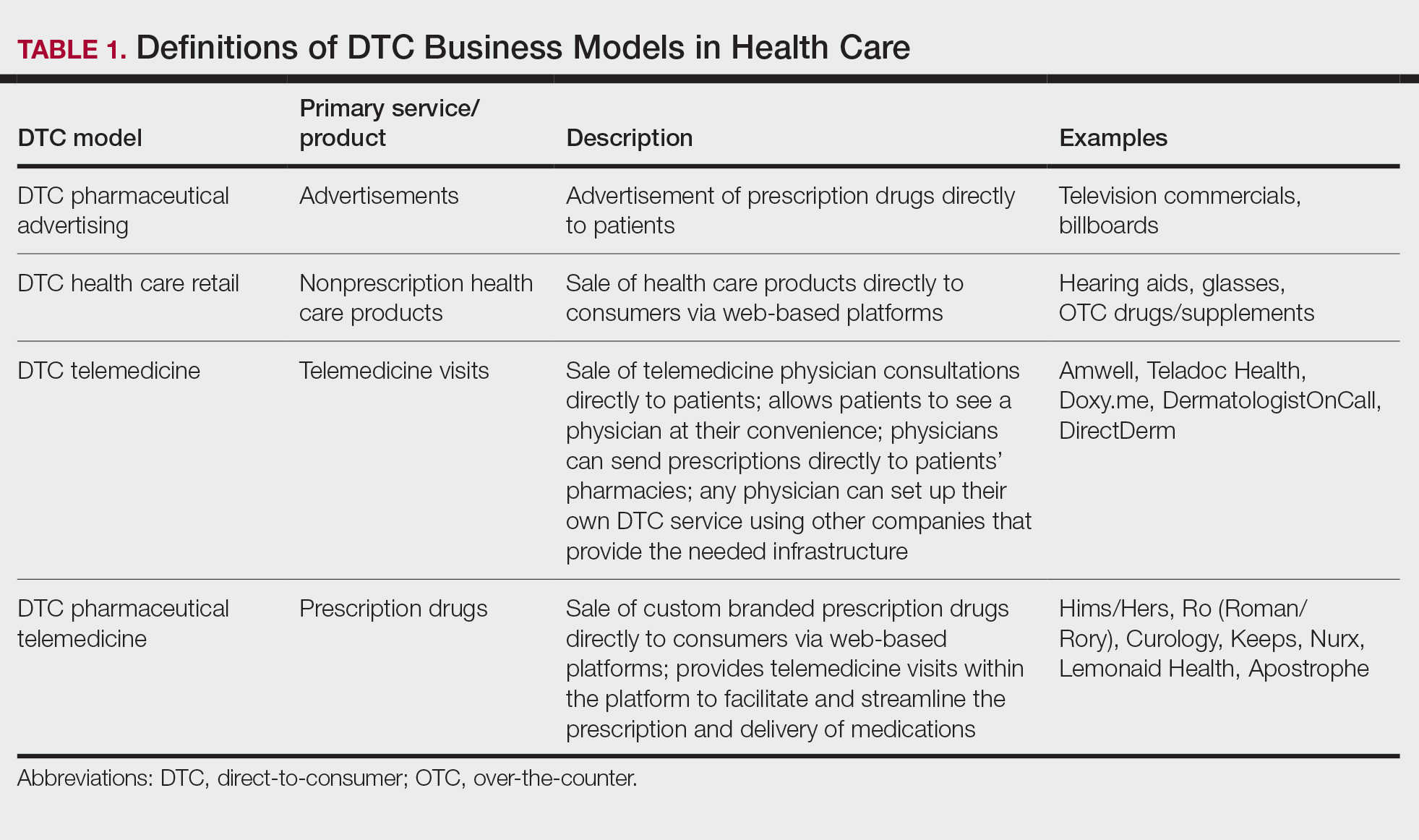

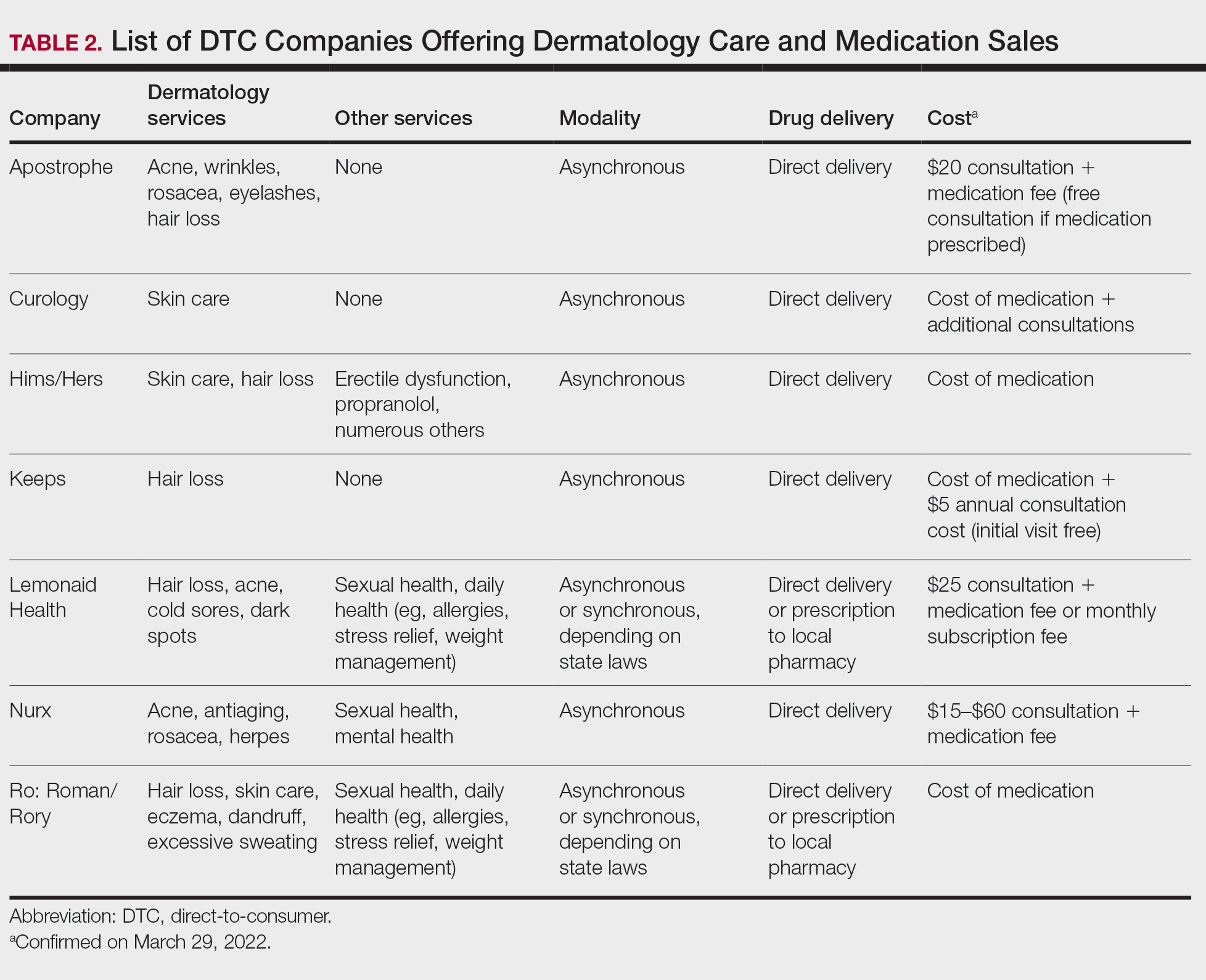

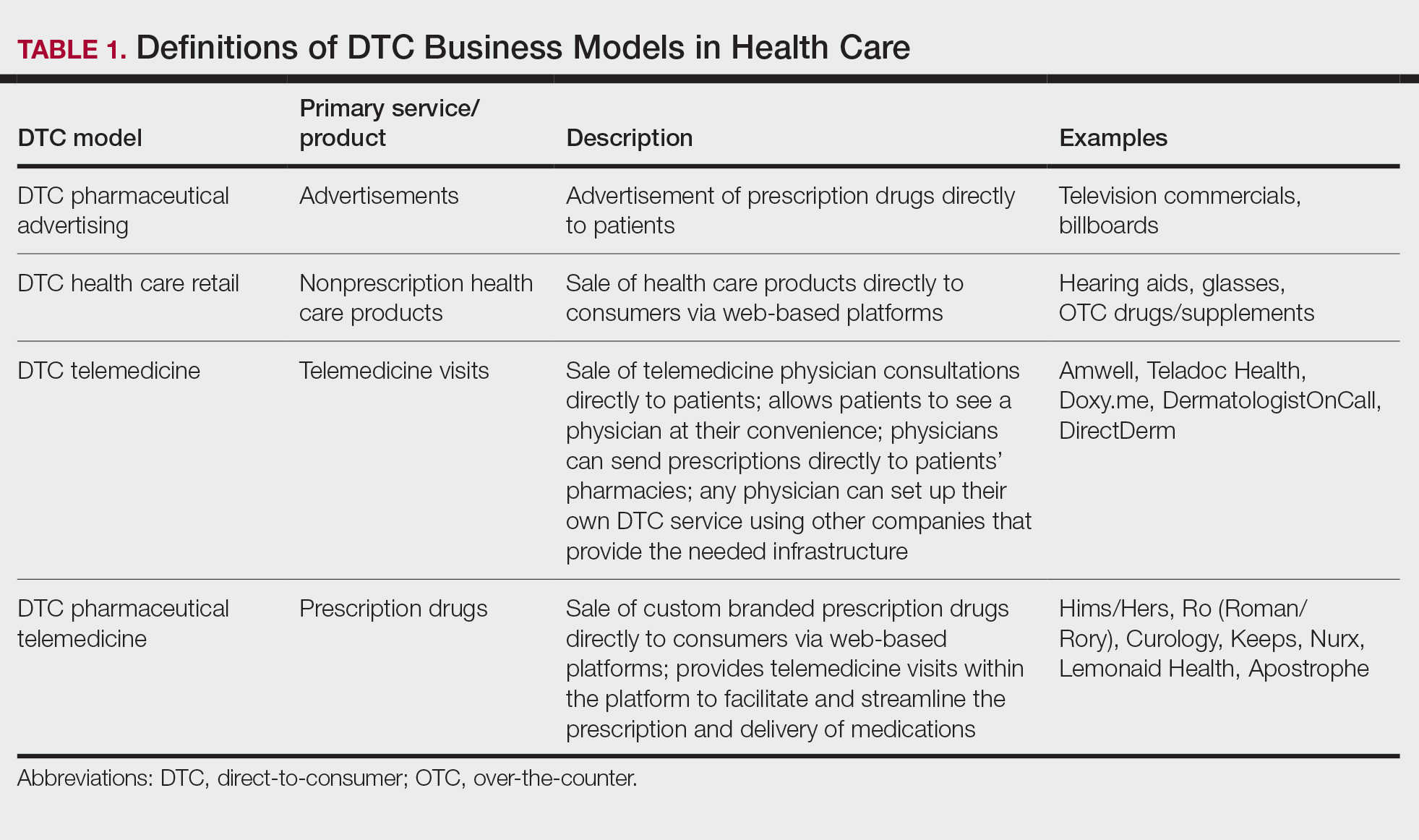

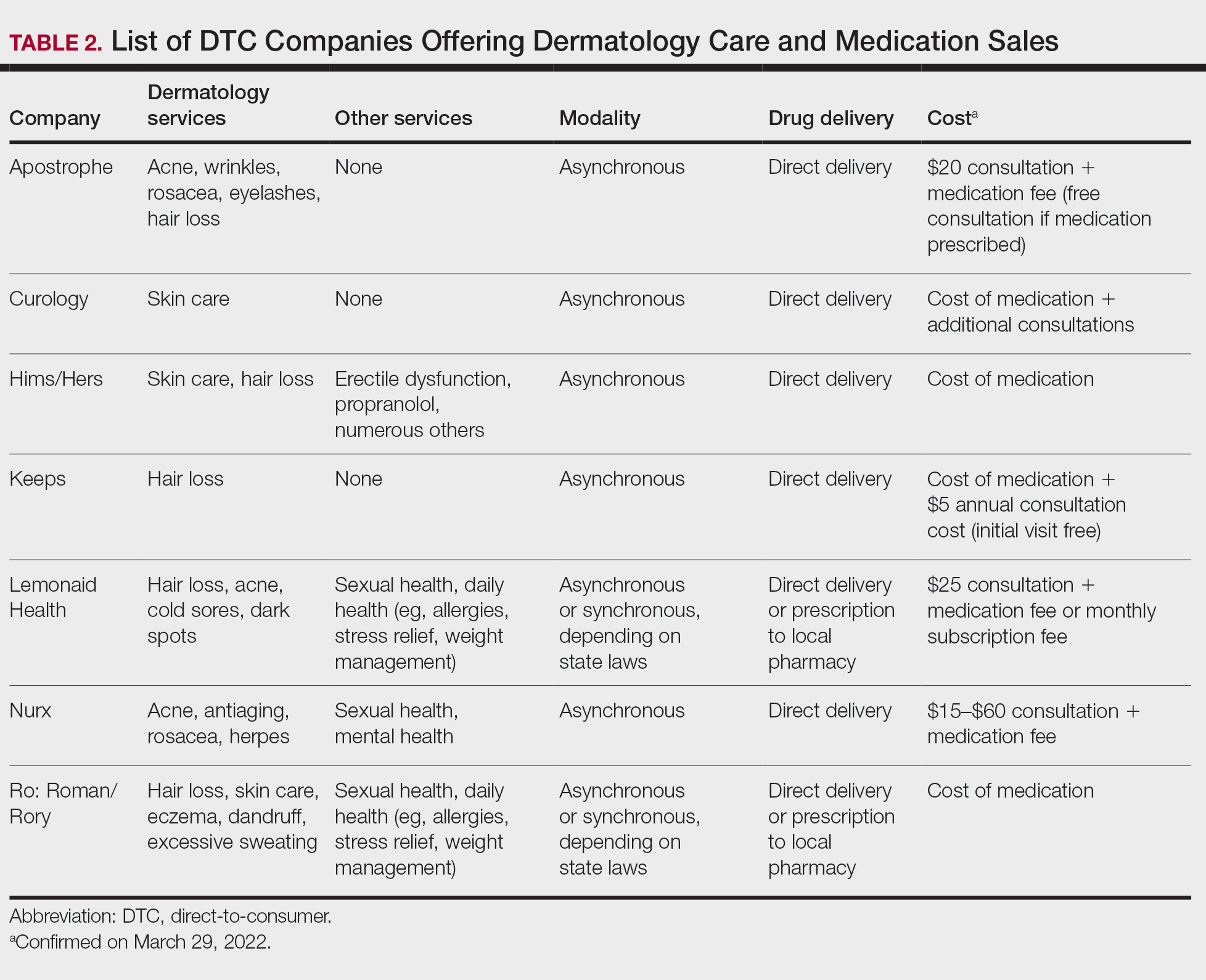

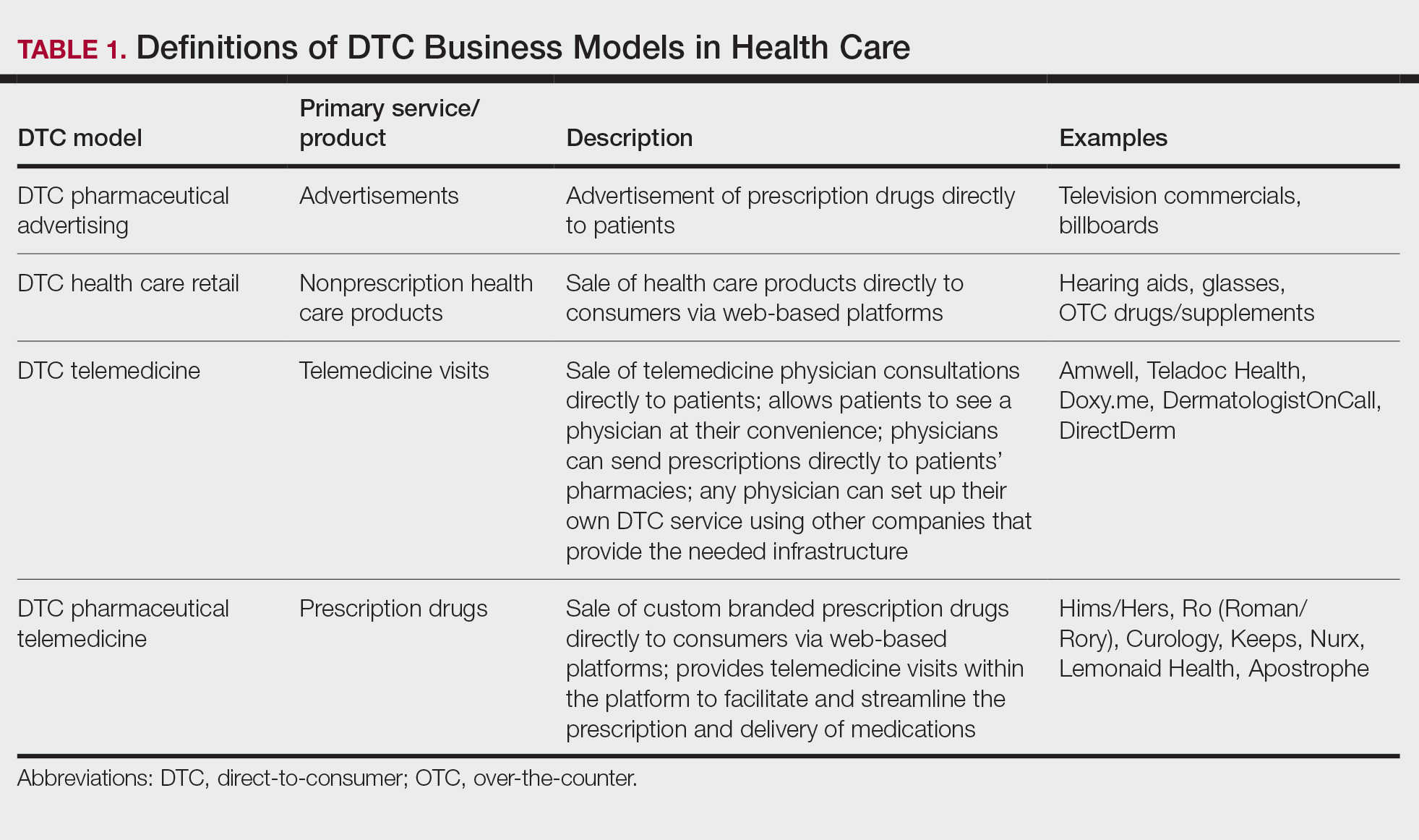

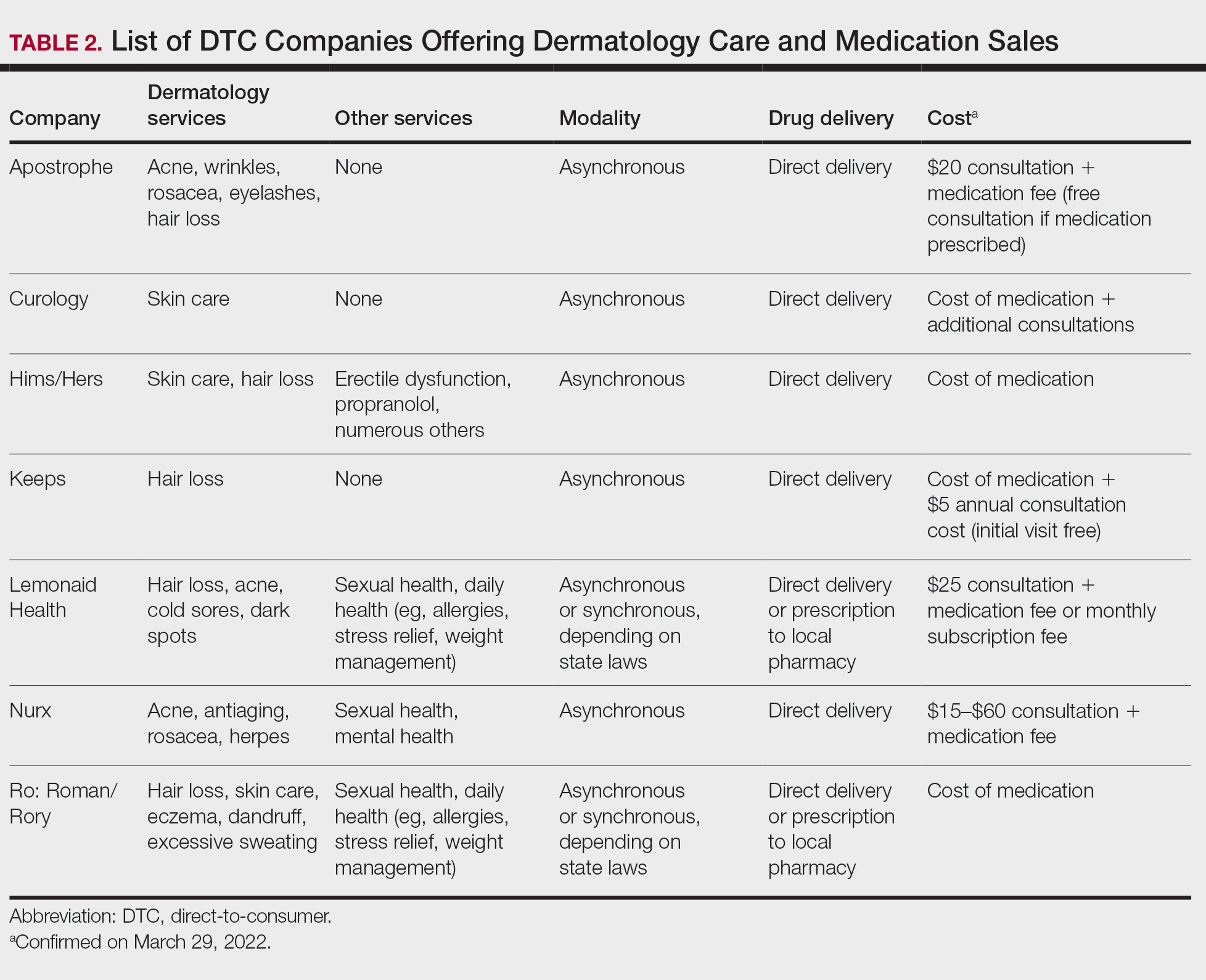

Ultimately, DTC has evolved to encompass multiple definitions in health care (Table 1). Although all models provide health care, each offers a different modality of delivery. The primary service may be the sale of prescription drugs or simply telemedicine visits. This review primarily discusses DTC pharmaceutical telemedicine platforms that sell private-label drugs and also offer telemedicine services to streamline care. However, the history, risks, and benefits discussed may apply to all models.

The DTC Landscape

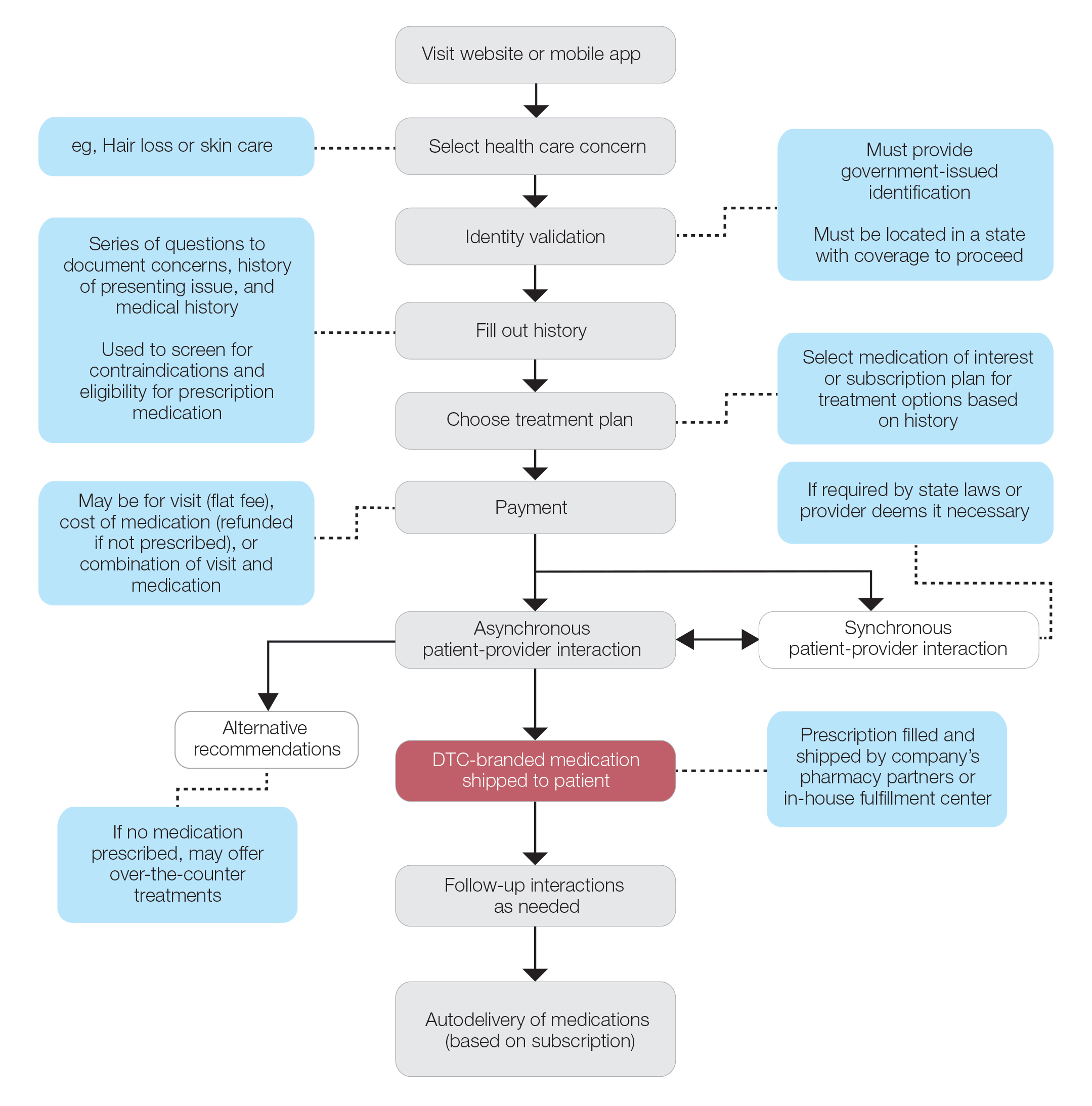

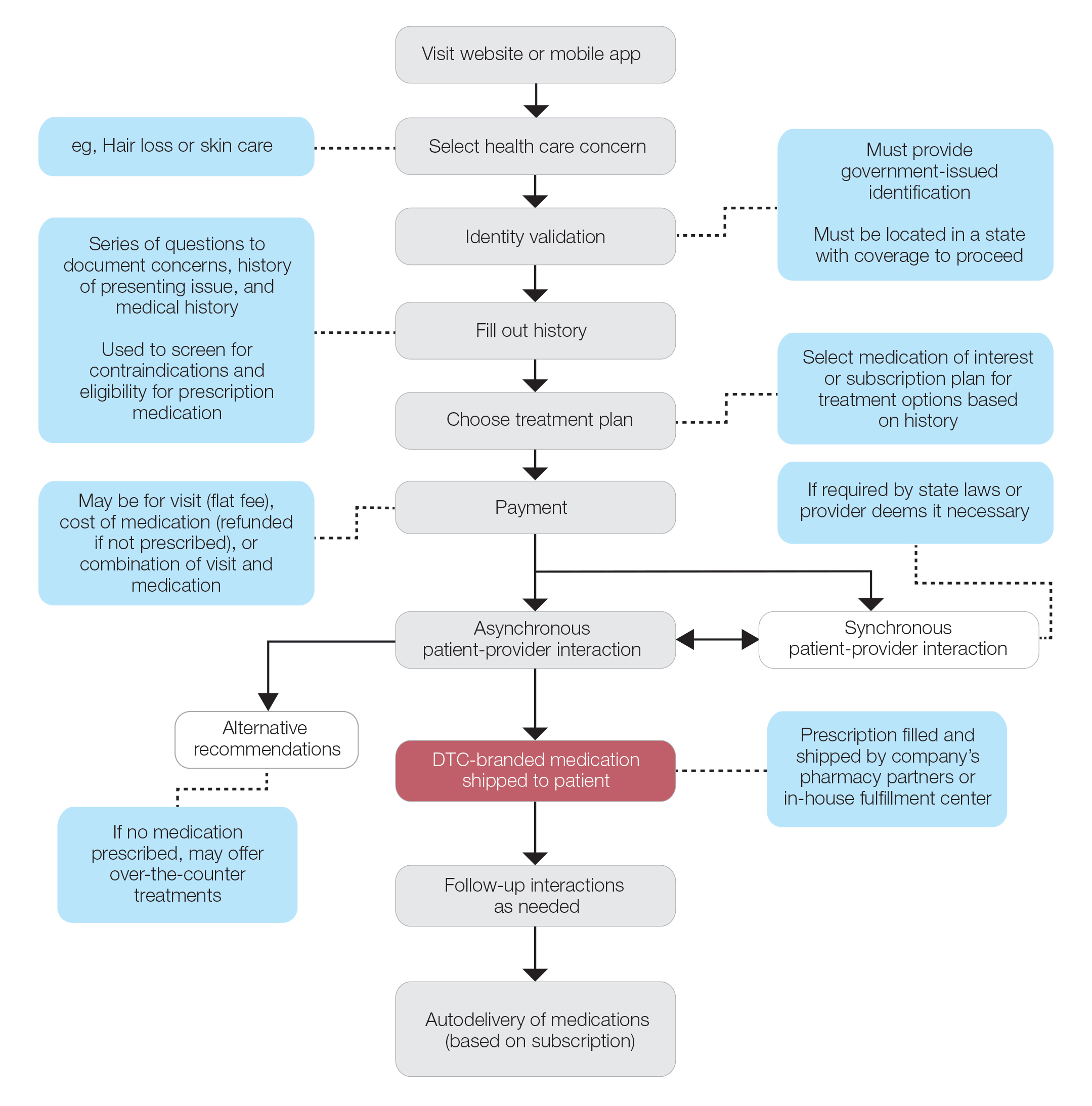

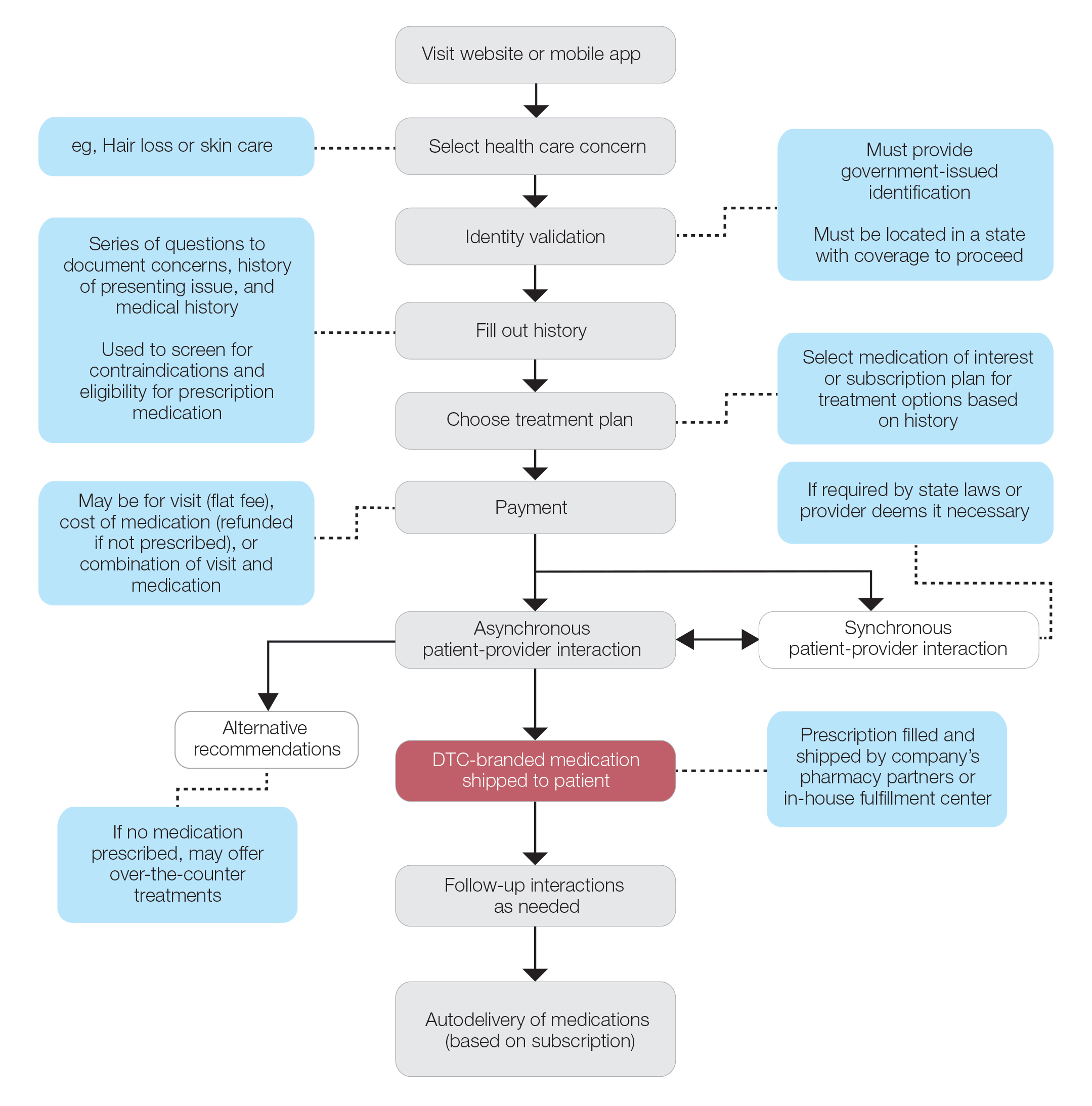

Most DTC companies employ variations on a model with the same 3 main components: a triage questionnaire, telehealth services, and prescription/drug delivery (Figure). The triage questionnaire elicits a history of the patient’s presentation and medical history. Some companies may use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to tailor questions to patient needs. There are 2 modalities for patient-provider communication: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous communication entails real-time patient-physician conversations via audio only or video call. Asynchronous (or store-and-forward) communication refers to consultations provided via messaging or text-based modality, where a provider may respond to a patient within 24 hours.6 Direct-to-consumer platforms primarily use asynchronous visits (Table 2). However, some also use synchronous modalities if the provider deems it necessary or if state laws require it.

Once a provider has consulted with the patient, they can prescribe medication as needed. In certain cases, with adequate history, a prescription may be issued without a full physician visit. Furthermore, DTC companies require purchase of their custom-branded generic drugs. Prescriptions are fulfilled by the company’s pharmacy network and directly shipped to patients; few will allow patients to transfer a prescription to a pharmacy of their choice. Some platforms also sell supplements and over-the-counter medications.

Payment models vary among these companies, and most do not accept insurance (Table 2). Select models may provide free consultations and only require payment for pharmaceuticals. Others charge for consultations but reallocate payment to the cost of medication if prescribed. Another model involves flat rates for consultations and additional charges for drugs but unlimited messaging with providers for the duration of the prescription. Moreover, patients can subscribe to monthly deliveries of their medications.

Foundation of DTC

Technological advances have enabled patients to receive remote treatment from a single platform offering video calls, AI, electronic medical record interoperability, and integration of drug supply chains. Even in its simplest form, AI is increasingly used, as it allows for programs and chatbots to screen and triage patients.11 Technology also has improved at targeted mass marketing through social media platforms and search engines (eg, companies can use age, interests, location, and other parameters to target individuals likely needing acne treatment).

Drug patent expirations are a key catalyst for the rise of DTC companies, creating an attractive business model with generic drugs as the core product. Since 2008, patents for medications treating chronic conditions, such as erectile dysfunction, have expired. These patent expirations are responsible for $198 billion in projected prescription sales between 2019 and 2024.1 Thus, it follows that DTC companies have seized this opportunity to act as middlemen, taking advantage of these generic medications’ lower costs to create platforms focused on personalization and accessibility.

Rising deductibles have led patients to consider cheaper out-of-pocket alternatives that are not covered by insurance.1 For example, insurers typically do not cover finasteride treatment for conditions deemed cosmetic, such as androgenetic alopecia.12 The low cost of generic drugs creates an attractive business model for patients and investors. According to GoodRx, the average retail price for a 30-day supply of brand-name finasteride (Propecia [Merck]) is $135.92, whereas generic finasteride is $75.24.13 Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical companies offer a 30-day supply of generic finasteride ranging from $8.33 to $30.14 The average wholesale cost for retailers is an estimated $2.31 for 30 days.15 Although profit margins on generic medications may be lower, more affordable drugs increase the size of the total market. These prescriptions are available as subscription plans, resulting in recurring revenue.