User login

Serotonergic antidepressants’ effects on bone health

Mrs. D, age 67, has a history of major depressive disorder. She has had adequate treatment trials with duloxetine, mirtazapine, and sertraline; each failed to produce remission. She is currently prescribed paroxetine, 40 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, with good efficacy. She also has a history of hypertension and seasonal allergies, for which she receives amlodipine, 10 mg/d, and loratadine, 10 mg/d, respectively.

Mrs. D’s depressive symptoms were well controlled until 2 months ago, when she fell and fractured her hip. With encouragement from her prescriber, she enrolled in a partial hospitalization program for more intensive psychotherapy. During a medication education session, she is surprised to learn that antidepressants may affect bone health.

During a medication management meeting with her prescriber, Mrs. D asks about the risk of osteoporosis, and whether her antidepressant could have contributed to her hip fracture.

Bone is a dynamic tissue that undergoes a continuous process of remodeling. Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation, whereas osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption. Osteocytes—the predominant cell type in bone—along with cytokines, hormones, and growth factors help to orchestrate these actions.1 Serotonin is increasingly recognized as a factor in bone homeostasis. Bone synthesizes serotonin, expresses serotonin transporters, and contains a variety of serotonin receptors.2

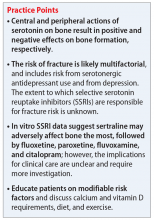

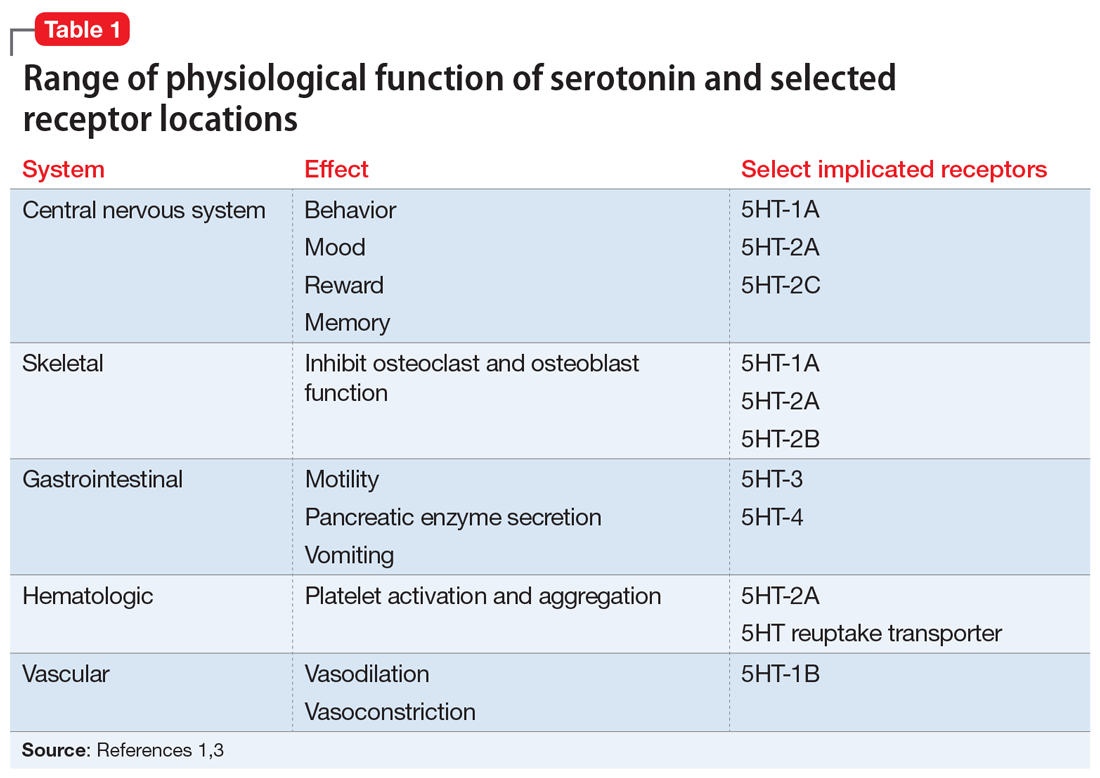

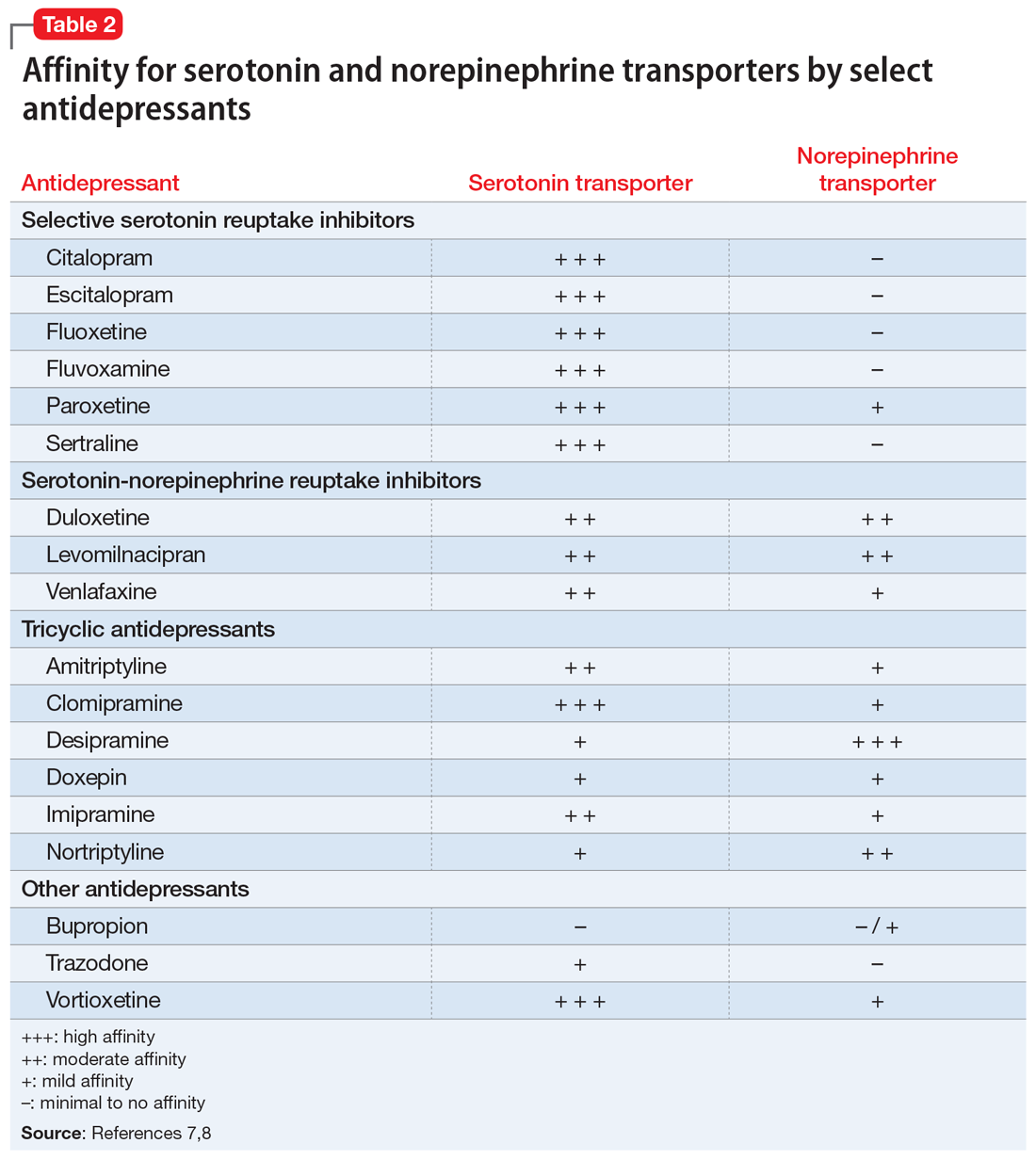

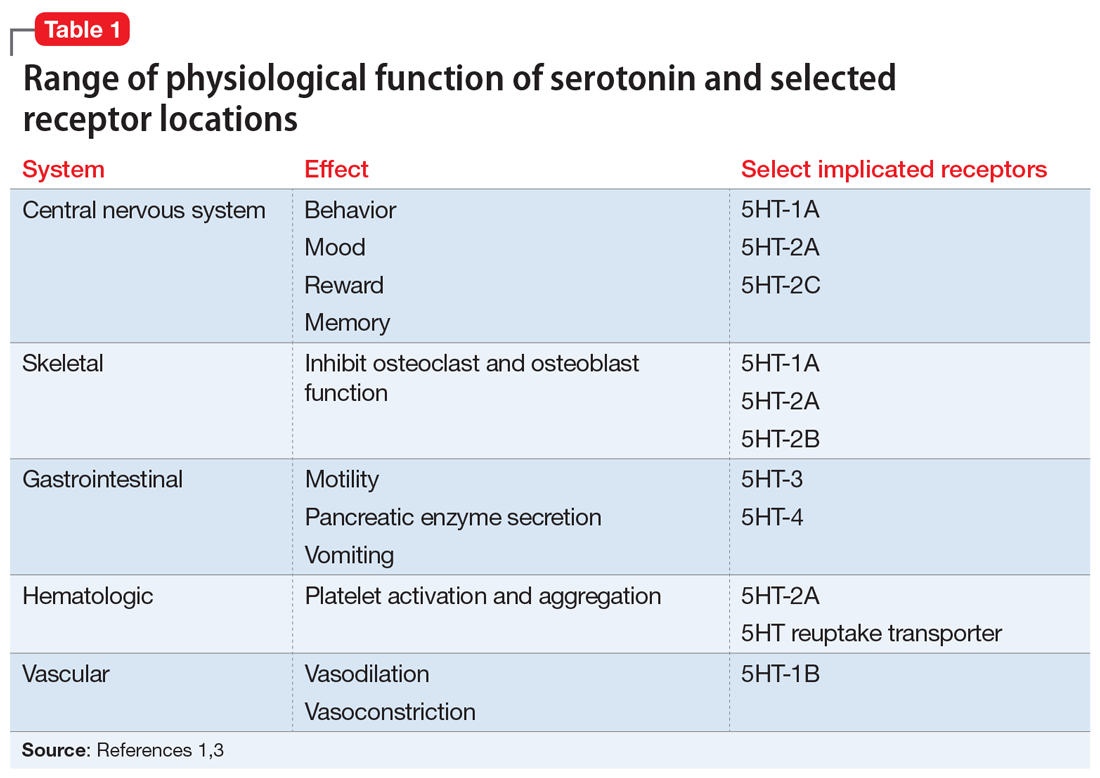

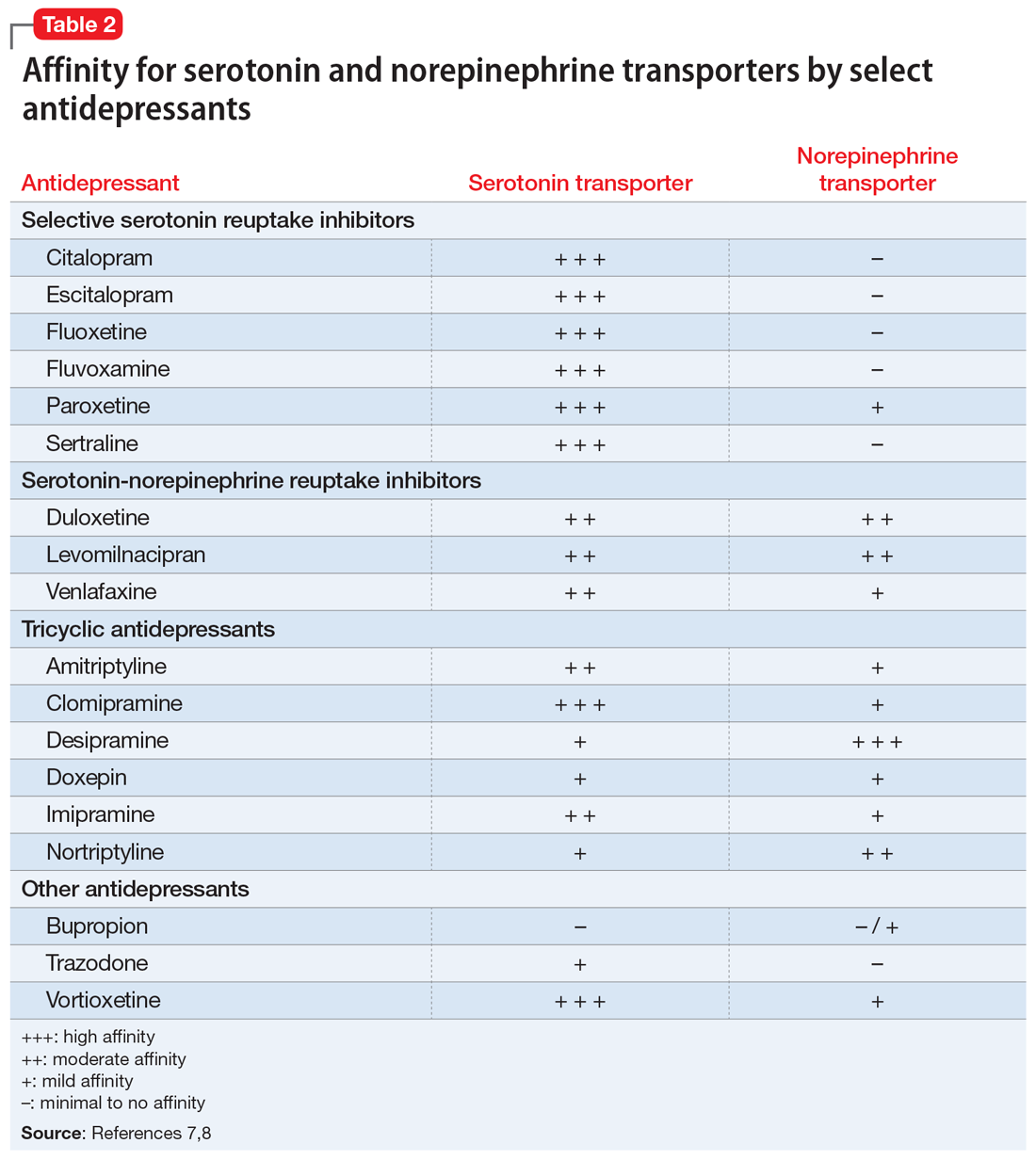

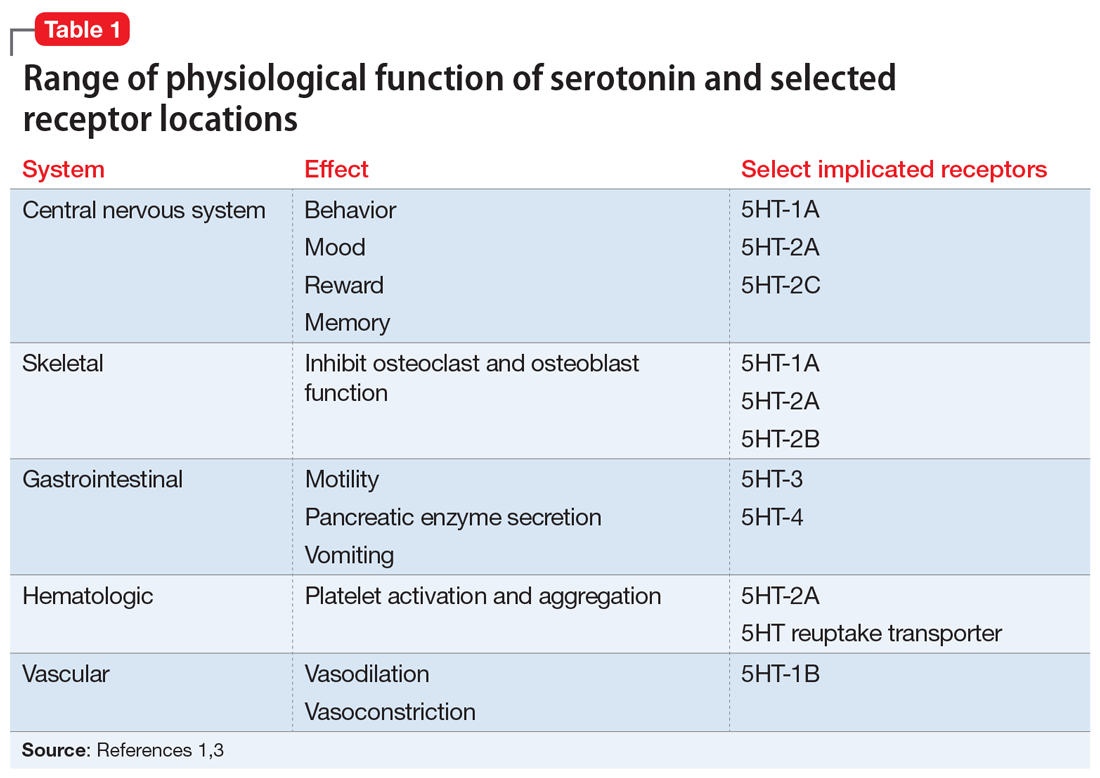

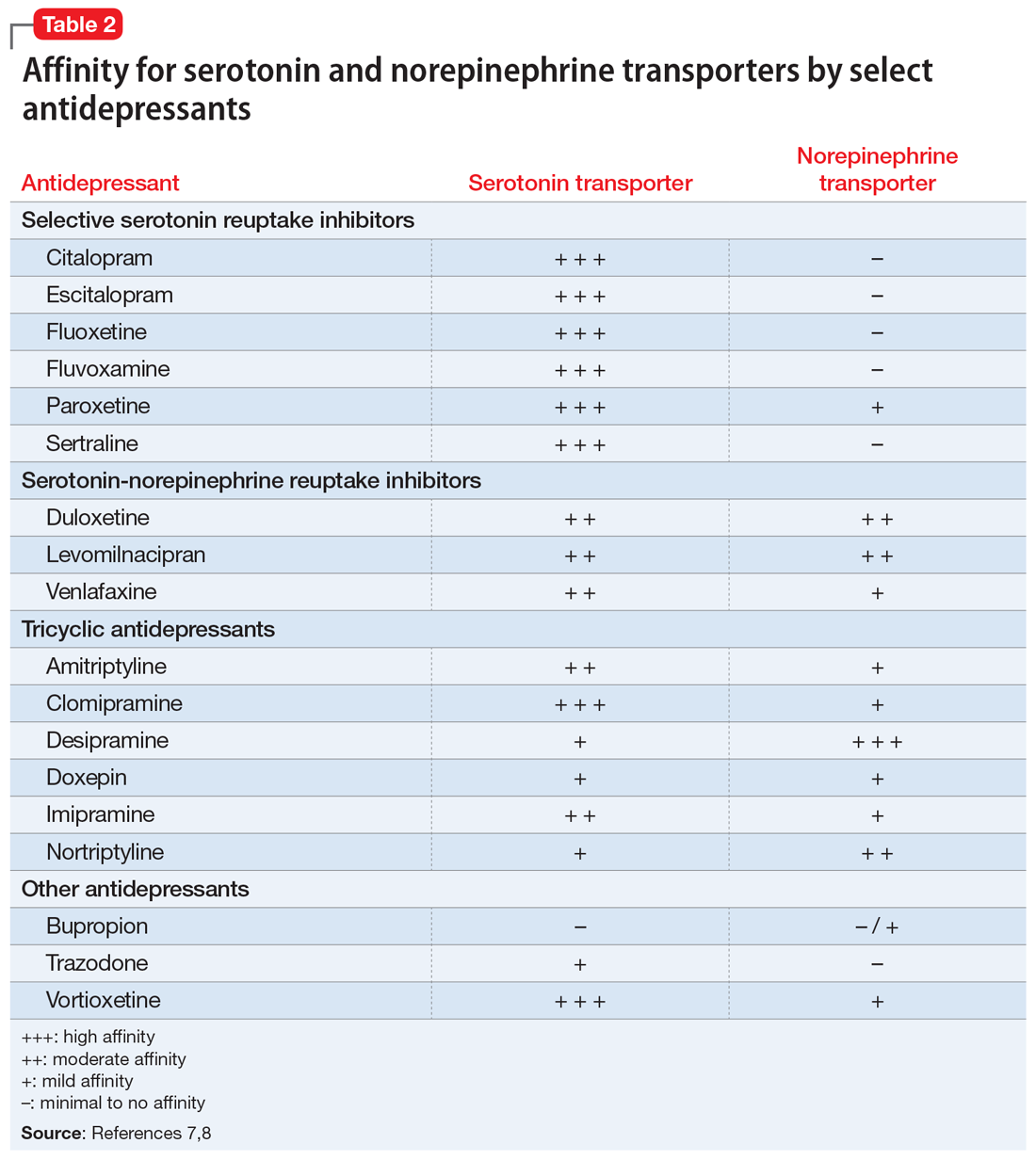

Serotonin serves many physiologic functions outside of the CNS, and it appears to have opposing actions on bone metabolism (Table 11,3). Peripheral (gut-derived) serotonin inhibits bone formation through its effects on osteoblasts, whereas the actions of serotonin in the CNS promote bone growth through inhibitory effects on sympathetic output.2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) enhancement of peripheral serotonin and its negative effect on bone may outweigh the benefits caused by SSRI enhancement of central serotonin neurotransmission.1 In vitro data suggest SSRIs inhibit osteoblast and osteoclast function, theoretically decreasing bone turnover and increasing fracture risk.4 Other data indicate SSRI treatment may decrease procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide, a peripheral marker of bone formation.5 Both SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been associated with lower cortical bone mineral density (BMD).6Table 27,8 details the relative affinity of select antidepressants for the serotonin transporter.

Both serotonergic antidepressants and depression have been associated with decreased BMD and increased fracture risk.1,9 Behavioral aspects of depression, such as inadequate nutrition or physical inactivity, overlap with risk factors for poor bone health. In addition, elevated levels of circulating cortisol and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with depressive symptoms may contribute to decreased bone mass.10,11 Modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis and fractures include low calcium and vitamin D intake, low body weight, and a sedentary lifestyle. Nonmodifiable risk factors include advancing age, female sex, Asian or White ethnicity, malabsorptive conditions, and chronic corticosteroid use.12

What the evidence says

Evidence for the correlation between fractures and serotonergic antidepressant use is mixed. One meta-analysis found a significant association between SSRIs and fractures, suggesting a 1.62-fold increased risk.13 Another meta-analysis investigated SSRIs and SNRIs and the risk of fracture.14 The SSRIs had a 1.67-fold increased risk; however, a lack of studies prohibited making conclusions about SNRIs. The number needed to harm was calculated at 85, 46, and 19 with 1, 2, and 5 years of SSRI exposure, respectively. A third meta-analysis found increased fracture risk related to depression and reported a hazard ratio of 1.26 after adjusting for confounders.9 This analysis suggests depression affects fracture risk and may limit the interpretation of causation from SSRI use. Studies included in these meta-analyses had significant heterogeneity.

Continue to: The effect of SSRIs...

The effect of SSRIs vs non-SSRIs on BMD also has been studied. The SSRIs were associated with significantly reduced BMD of the lumbar spine but not the total hip or femoral neck as compared to non-SSRIs; however, this BMD loss was not examined in relation to the presence of fractures. Older patients had more pronounced bone loss.15 Conversely, another meta-analysis examined BMD in women receiving SSRIs or tricyclic antidepressants.10 Neither medication class was associated with lower BMD at measured locations, including lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip. This analysis was limited by the lack of available trials; only 4 were included.

Other recent research has continued to explore the relationship between antidepressants and fracture in various patient populations. In a study of patients receiving maintenance dialysis treatment, short- and long-term SSRI use increased hip fracture risk. The authors speculated that short-term risk may be mediated by adverse effects that increase fall risk (eg, hyponatremia, orthostasis), whereas long-term risk may be influenced by changes in bone homeostasis.16 In two 6-month analyses of fluoxetine treatment in patients following an acute stroke, fluoxetine increased the risk of bone fractures.17,18 Finally, in women with osteoporosis receiving risedronate or teriparatide, in both groups a higher fracture risk was observed for patients who were also receiving an SSRI or SNRI.19

Monitor BMD and educate patients about bone health

Available literature has not identified any clear risk factors for fracture with SSRI use. Guidelines suggest monitoring BMD in patients with risk factors for osteoporosis, if clinically indicated, as well as monitoring BMD in those receiving long-term antidepressant treatment.20-22 Educate patients on strategies that promote optimal bone health, such as consuming a balanced diet that meets the recommended dietary allowance of calcium, vitamin D, and limits soda consumption. Teach patients to avoid tobacco and excessive alcohol use because both adversely impact BMD. Maintaining a healthy weight, physical activity, and adequate sleep also support bone health.11 Instruct patients receiving antidepressants to report unexplained bone pain, tenderness, swelling, or bruising because these symptoms may be indicative of fracture.

CASE CONTINUED

Mrs. D’s age, sex, and depression place her at higher risk of fracture. Paroxetine is the only SSRI that has bone fracture listed as a precaution in its labeling.23 In addition, it is the most anticholinergic SSRI and may have contributed to her fall. Switching to bupropion by cross titration may benefit Mrs. D because bupropion is not serotonergic. Little data exist regarding the effects of bupropion on bone. Her prescriber monitors Mrs. D’s BMD periodically, and educates her on dietary considerations. He also recommends calcium, 1,200 mg/d, and vitamin D, 800 IU/d, to help prevent fractures,24 and that she continue physical therapy exercises and increase physical activity as tolerated.

Related Resources

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

- Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

- Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

- US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Desipramine • Norpramin

Doxepin • Silenor, Sinequan

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Loratadine • Claritin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risedronate • Actonel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Teriparatide • Forteo

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

2. Lavoie B, Lian JB, Mawe GM. Regulation of bone metabolism by serotonin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1033:35-46.

3. Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:355-366.

4. Hodge JM, Wang Y, Berk M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors inhibit human osteoclast and osteoblast formation and function. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):32-39.

5. Kumar M, Jiloha RC, Kataria D, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on markers of bone loss. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:39-44.

6. Agarwal S, Germosen C, Kil N, et al. Current anti-depressant use is associated with cortical bone deficits and reduced physical function in elderly women. Bone. 2020;140:115552.

7. DeBattista C. Antidepressant agents. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and clinical pharmacology. 14th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2018.

8. Kasper S, Pail G. Milnacipran: a unique antidepressant? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6(Suppl 1):23-31.

9. Wu Q, Liu B, Tonmoy S. Depression and risk of fracture and bone loss: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1303-1312.

10. Schweiger JU, Schweiger U, Hüppe M, et al. The use of antidepressant agents and bone mineral density in women: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1373.

11. Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Reginster JY, et al. Antidepressant medications and osteoporosis. Bone. 2012;51(3):606-613.

12. Rice JN, Gillett CB, Malas NM. The impact of psychotropic medications on bone health in youth. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(11):104.

13. Kumar M, Bajpai R, Shaik AR, et al. Alliance between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fracture risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(10):1373-1392.

14. Khanassov V, Hu J, Reeves D, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor use and risk of fractures in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1688-1708.

15. Zhou C, Fang L, Chen Y, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1243-1251.

16. Vangala C, Niu J, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and hip fracture risk among patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):351-360.

17. Hankey GJ, Hackett ML, Almeida OP, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):651-660.

18. Lundström E, Isaksson E, Näsman P, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):661-669.

19. Kendler DL, Marin F, Geusens P, et al. Psychotropic medications and proton pump inhibitors and the risk of fractures in the teriparatide versus risedronate VERO clinical trial. Bone. 2020;130:115113.

20. Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Published October 2010. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf

22. Agacayak KS, Guler R, Ilyasov B. Evaluation of the effect of long-term use of antidepressants in the SSRI group on bone density with dental volumetric tomography. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3477-3484.

23. US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

24. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

Mrs. D, age 67, has a history of major depressive disorder. She has had adequate treatment trials with duloxetine, mirtazapine, and sertraline; each failed to produce remission. She is currently prescribed paroxetine, 40 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, with good efficacy. She also has a history of hypertension and seasonal allergies, for which she receives amlodipine, 10 mg/d, and loratadine, 10 mg/d, respectively.

Mrs. D’s depressive symptoms were well controlled until 2 months ago, when she fell and fractured her hip. With encouragement from her prescriber, she enrolled in a partial hospitalization program for more intensive psychotherapy. During a medication education session, she is surprised to learn that antidepressants may affect bone health.

During a medication management meeting with her prescriber, Mrs. D asks about the risk of osteoporosis, and whether her antidepressant could have contributed to her hip fracture.

Bone is a dynamic tissue that undergoes a continuous process of remodeling. Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation, whereas osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption. Osteocytes—the predominant cell type in bone—along with cytokines, hormones, and growth factors help to orchestrate these actions.1 Serotonin is increasingly recognized as a factor in bone homeostasis. Bone synthesizes serotonin, expresses serotonin transporters, and contains a variety of serotonin receptors.2

Serotonin serves many physiologic functions outside of the CNS, and it appears to have opposing actions on bone metabolism (Table 11,3). Peripheral (gut-derived) serotonin inhibits bone formation through its effects on osteoblasts, whereas the actions of serotonin in the CNS promote bone growth through inhibitory effects on sympathetic output.2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) enhancement of peripheral serotonin and its negative effect on bone may outweigh the benefits caused by SSRI enhancement of central serotonin neurotransmission.1 In vitro data suggest SSRIs inhibit osteoblast and osteoclast function, theoretically decreasing bone turnover and increasing fracture risk.4 Other data indicate SSRI treatment may decrease procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide, a peripheral marker of bone formation.5 Both SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been associated with lower cortical bone mineral density (BMD).6Table 27,8 details the relative affinity of select antidepressants for the serotonin transporter.

Both serotonergic antidepressants and depression have been associated with decreased BMD and increased fracture risk.1,9 Behavioral aspects of depression, such as inadequate nutrition or physical inactivity, overlap with risk factors for poor bone health. In addition, elevated levels of circulating cortisol and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with depressive symptoms may contribute to decreased bone mass.10,11 Modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis and fractures include low calcium and vitamin D intake, low body weight, and a sedentary lifestyle. Nonmodifiable risk factors include advancing age, female sex, Asian or White ethnicity, malabsorptive conditions, and chronic corticosteroid use.12

What the evidence says

Evidence for the correlation between fractures and serotonergic antidepressant use is mixed. One meta-analysis found a significant association between SSRIs and fractures, suggesting a 1.62-fold increased risk.13 Another meta-analysis investigated SSRIs and SNRIs and the risk of fracture.14 The SSRIs had a 1.67-fold increased risk; however, a lack of studies prohibited making conclusions about SNRIs. The number needed to harm was calculated at 85, 46, and 19 with 1, 2, and 5 years of SSRI exposure, respectively. A third meta-analysis found increased fracture risk related to depression and reported a hazard ratio of 1.26 after adjusting for confounders.9 This analysis suggests depression affects fracture risk and may limit the interpretation of causation from SSRI use. Studies included in these meta-analyses had significant heterogeneity.

Continue to: The effect of SSRIs...

The effect of SSRIs vs non-SSRIs on BMD also has been studied. The SSRIs were associated with significantly reduced BMD of the lumbar spine but not the total hip or femoral neck as compared to non-SSRIs; however, this BMD loss was not examined in relation to the presence of fractures. Older patients had more pronounced bone loss.15 Conversely, another meta-analysis examined BMD in women receiving SSRIs or tricyclic antidepressants.10 Neither medication class was associated with lower BMD at measured locations, including lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip. This analysis was limited by the lack of available trials; only 4 were included.

Other recent research has continued to explore the relationship between antidepressants and fracture in various patient populations. In a study of patients receiving maintenance dialysis treatment, short- and long-term SSRI use increased hip fracture risk. The authors speculated that short-term risk may be mediated by adverse effects that increase fall risk (eg, hyponatremia, orthostasis), whereas long-term risk may be influenced by changes in bone homeostasis.16 In two 6-month analyses of fluoxetine treatment in patients following an acute stroke, fluoxetine increased the risk of bone fractures.17,18 Finally, in women with osteoporosis receiving risedronate or teriparatide, in both groups a higher fracture risk was observed for patients who were also receiving an SSRI or SNRI.19

Monitor BMD and educate patients about bone health

Available literature has not identified any clear risk factors for fracture with SSRI use. Guidelines suggest monitoring BMD in patients with risk factors for osteoporosis, if clinically indicated, as well as monitoring BMD in those receiving long-term antidepressant treatment.20-22 Educate patients on strategies that promote optimal bone health, such as consuming a balanced diet that meets the recommended dietary allowance of calcium, vitamin D, and limits soda consumption. Teach patients to avoid tobacco and excessive alcohol use because both adversely impact BMD. Maintaining a healthy weight, physical activity, and adequate sleep also support bone health.11 Instruct patients receiving antidepressants to report unexplained bone pain, tenderness, swelling, or bruising because these symptoms may be indicative of fracture.

CASE CONTINUED

Mrs. D’s age, sex, and depression place her at higher risk of fracture. Paroxetine is the only SSRI that has bone fracture listed as a precaution in its labeling.23 In addition, it is the most anticholinergic SSRI and may have contributed to her fall. Switching to bupropion by cross titration may benefit Mrs. D because bupropion is not serotonergic. Little data exist regarding the effects of bupropion on bone. Her prescriber monitors Mrs. D’s BMD periodically, and educates her on dietary considerations. He also recommends calcium, 1,200 mg/d, and vitamin D, 800 IU/d, to help prevent fractures,24 and that she continue physical therapy exercises and increase physical activity as tolerated.

Related Resources

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

- Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

- Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

- US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Desipramine • Norpramin

Doxepin • Silenor, Sinequan

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Loratadine • Claritin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risedronate • Actonel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Teriparatide • Forteo

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Mrs. D, age 67, has a history of major depressive disorder. She has had adequate treatment trials with duloxetine, mirtazapine, and sertraline; each failed to produce remission. She is currently prescribed paroxetine, 40 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, with good efficacy. She also has a history of hypertension and seasonal allergies, for which she receives amlodipine, 10 mg/d, and loratadine, 10 mg/d, respectively.

Mrs. D’s depressive symptoms were well controlled until 2 months ago, when she fell and fractured her hip. With encouragement from her prescriber, she enrolled in a partial hospitalization program for more intensive psychotherapy. During a medication education session, she is surprised to learn that antidepressants may affect bone health.

During a medication management meeting with her prescriber, Mrs. D asks about the risk of osteoporosis, and whether her antidepressant could have contributed to her hip fracture.

Bone is a dynamic tissue that undergoes a continuous process of remodeling. Osteoblasts are responsible for bone formation, whereas osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption. Osteocytes—the predominant cell type in bone—along with cytokines, hormones, and growth factors help to orchestrate these actions.1 Serotonin is increasingly recognized as a factor in bone homeostasis. Bone synthesizes serotonin, expresses serotonin transporters, and contains a variety of serotonin receptors.2

Serotonin serves many physiologic functions outside of the CNS, and it appears to have opposing actions on bone metabolism (Table 11,3). Peripheral (gut-derived) serotonin inhibits bone formation through its effects on osteoblasts, whereas the actions of serotonin in the CNS promote bone growth through inhibitory effects on sympathetic output.2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) enhancement of peripheral serotonin and its negative effect on bone may outweigh the benefits caused by SSRI enhancement of central serotonin neurotransmission.1 In vitro data suggest SSRIs inhibit osteoblast and osteoclast function, theoretically decreasing bone turnover and increasing fracture risk.4 Other data indicate SSRI treatment may decrease procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide, a peripheral marker of bone formation.5 Both SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been associated with lower cortical bone mineral density (BMD).6Table 27,8 details the relative affinity of select antidepressants for the serotonin transporter.

Both serotonergic antidepressants and depression have been associated with decreased BMD and increased fracture risk.1,9 Behavioral aspects of depression, such as inadequate nutrition or physical inactivity, overlap with risk factors for poor bone health. In addition, elevated levels of circulating cortisol and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with depressive symptoms may contribute to decreased bone mass.10,11 Modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis and fractures include low calcium and vitamin D intake, low body weight, and a sedentary lifestyle. Nonmodifiable risk factors include advancing age, female sex, Asian or White ethnicity, malabsorptive conditions, and chronic corticosteroid use.12

What the evidence says

Evidence for the correlation between fractures and serotonergic antidepressant use is mixed. One meta-analysis found a significant association between SSRIs and fractures, suggesting a 1.62-fold increased risk.13 Another meta-analysis investigated SSRIs and SNRIs and the risk of fracture.14 The SSRIs had a 1.67-fold increased risk; however, a lack of studies prohibited making conclusions about SNRIs. The number needed to harm was calculated at 85, 46, and 19 with 1, 2, and 5 years of SSRI exposure, respectively. A third meta-analysis found increased fracture risk related to depression and reported a hazard ratio of 1.26 after adjusting for confounders.9 This analysis suggests depression affects fracture risk and may limit the interpretation of causation from SSRI use. Studies included in these meta-analyses had significant heterogeneity.

Continue to: The effect of SSRIs...

The effect of SSRIs vs non-SSRIs on BMD also has been studied. The SSRIs were associated with significantly reduced BMD of the lumbar spine but not the total hip or femoral neck as compared to non-SSRIs; however, this BMD loss was not examined in relation to the presence of fractures. Older patients had more pronounced bone loss.15 Conversely, another meta-analysis examined BMD in women receiving SSRIs or tricyclic antidepressants.10 Neither medication class was associated with lower BMD at measured locations, including lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip. This analysis was limited by the lack of available trials; only 4 were included.

Other recent research has continued to explore the relationship between antidepressants and fracture in various patient populations. In a study of patients receiving maintenance dialysis treatment, short- and long-term SSRI use increased hip fracture risk. The authors speculated that short-term risk may be mediated by adverse effects that increase fall risk (eg, hyponatremia, orthostasis), whereas long-term risk may be influenced by changes in bone homeostasis.16 In two 6-month analyses of fluoxetine treatment in patients following an acute stroke, fluoxetine increased the risk of bone fractures.17,18 Finally, in women with osteoporosis receiving risedronate or teriparatide, in both groups a higher fracture risk was observed for patients who were also receiving an SSRI or SNRI.19

Monitor BMD and educate patients about bone health

Available literature has not identified any clear risk factors for fracture with SSRI use. Guidelines suggest monitoring BMD in patients with risk factors for osteoporosis, if clinically indicated, as well as monitoring BMD in those receiving long-term antidepressant treatment.20-22 Educate patients on strategies that promote optimal bone health, such as consuming a balanced diet that meets the recommended dietary allowance of calcium, vitamin D, and limits soda consumption. Teach patients to avoid tobacco and excessive alcohol use because both adversely impact BMD. Maintaining a healthy weight, physical activity, and adequate sleep also support bone health.11 Instruct patients receiving antidepressants to report unexplained bone pain, tenderness, swelling, or bruising because these symptoms may be indicative of fracture.

CASE CONTINUED

Mrs. D’s age, sex, and depression place her at higher risk of fracture. Paroxetine is the only SSRI that has bone fracture listed as a precaution in its labeling.23 In addition, it is the most anticholinergic SSRI and may have contributed to her fall. Switching to bupropion by cross titration may benefit Mrs. D because bupropion is not serotonergic. Little data exist regarding the effects of bupropion on bone. Her prescriber monitors Mrs. D’s BMD periodically, and educates her on dietary considerations. He also recommends calcium, 1,200 mg/d, and vitamin D, 800 IU/d, to help prevent fractures,24 and that she continue physical therapy exercises and increase physical activity as tolerated.

Related Resources

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

- Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

- Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

- US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Desipramine • Norpramin

Doxepin • Silenor, Sinequan

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Loratadine • Claritin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risedronate • Actonel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Teriparatide • Forteo

Trazodone • Desyrel

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

2. Lavoie B, Lian JB, Mawe GM. Regulation of bone metabolism by serotonin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1033:35-46.

3. Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:355-366.

4. Hodge JM, Wang Y, Berk M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors inhibit human osteoclast and osteoblast formation and function. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):32-39.

5. Kumar M, Jiloha RC, Kataria D, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on markers of bone loss. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:39-44.

6. Agarwal S, Germosen C, Kil N, et al. Current anti-depressant use is associated with cortical bone deficits and reduced physical function in elderly women. Bone. 2020;140:115552.

7. DeBattista C. Antidepressant agents. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and clinical pharmacology. 14th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2018.

8. Kasper S, Pail G. Milnacipran: a unique antidepressant? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6(Suppl 1):23-31.

9. Wu Q, Liu B, Tonmoy S. Depression and risk of fracture and bone loss: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1303-1312.

10. Schweiger JU, Schweiger U, Hüppe M, et al. The use of antidepressant agents and bone mineral density in women: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1373.

11. Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Reginster JY, et al. Antidepressant medications and osteoporosis. Bone. 2012;51(3):606-613.

12. Rice JN, Gillett CB, Malas NM. The impact of psychotropic medications on bone health in youth. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(11):104.

13. Kumar M, Bajpai R, Shaik AR, et al. Alliance between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fracture risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(10):1373-1392.

14. Khanassov V, Hu J, Reeves D, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor use and risk of fractures in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1688-1708.

15. Zhou C, Fang L, Chen Y, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1243-1251.

16. Vangala C, Niu J, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and hip fracture risk among patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):351-360.

17. Hankey GJ, Hackett ML, Almeida OP, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):651-660.

18. Lundström E, Isaksson E, Näsman P, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):661-669.

19. Kendler DL, Marin F, Geusens P, et al. Psychotropic medications and proton pump inhibitors and the risk of fractures in the teriparatide versus risedronate VERO clinical trial. Bone. 2020;130:115113.

20. Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Published October 2010. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf

22. Agacayak KS, Guler R, Ilyasov B. Evaluation of the effect of long-term use of antidepressants in the SSRI group on bone density with dental volumetric tomography. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3477-3484.

23. US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

24. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

1. Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, et al. Effects of depression and serotonergic antidepressants on bone: mechanisms and implications for the treatment of depression. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):21-25.

2. Lavoie B, Lian JB, Mawe GM. Regulation of bone metabolism by serotonin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1033:35-46.

3. Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:355-366.

4. Hodge JM, Wang Y, Berk M, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors inhibit human osteoclast and osteoblast formation and function. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):32-39.

5. Kumar M, Jiloha RC, Kataria D, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on markers of bone loss. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:39-44.

6. Agarwal S, Germosen C, Kil N, et al. Current anti-depressant use is associated with cortical bone deficits and reduced physical function in elderly women. Bone. 2020;140:115552.

7. DeBattista C. Antidepressant agents. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and clinical pharmacology. 14th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2018.

8. Kasper S, Pail G. Milnacipran: a unique antidepressant? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6(Suppl 1):23-31.

9. Wu Q, Liu B, Tonmoy S. Depression and risk of fracture and bone loss: an updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1303-1312.

10. Schweiger JU, Schweiger U, Hüppe M, et al. The use of antidepressant agents and bone mineral density in women: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1373.

11. Rizzoli R, Cooper C, Reginster JY, et al. Antidepressant medications and osteoporosis. Bone. 2012;51(3):606-613.

12. Rice JN, Gillett CB, Malas NM. The impact of psychotropic medications on bone health in youth. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(11):104.

13. Kumar M, Bajpai R, Shaik AR, et al. Alliance between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fracture risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(10):1373-1392.

14. Khanassov V, Hu J, Reeves D, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor use and risk of fractures in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(12):1688-1708.

15. Zhou C, Fang L, Chen Y, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(6):1243-1251.

16. Vangala C, Niu J, Montez-Rath ME, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and hip fracture risk among patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):351-360.

17. Hankey GJ, Hackett ML, Almeida OP, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):651-660.

18. Lundström E, Isaksson E, Näsman P, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(8):661-669.

19. Kendler DL, Marin F, Geusens P, et al. Psychotropic medications and proton pump inhibitors and the risk of fractures in the teriparatide versus risedronate VERO clinical trial. Bone. 2020;130:115113.

20. Dodd S, Mitchell PB, Bauer M, et al. Monitoring for antidepressant-associated adverse events in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: an international consensus statement. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(5):330-348.

21. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Published October 2010. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf

22. Agacayak KS, Guler R, Ilyasov B. Evaluation of the effect of long-term use of antidepressants in the SSRI group on bone density with dental volumetric tomography. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3477-3484.

23. US National Library of Medicine. DailyMed. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed

24. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2581.

Administration of ketamine for depression should be limited to psychiatrists

In the modern-day practice of medicine, turf wars are more common than one may realize. Presently, an ongoing battle over who should be prescribing and administering ketamine for novel treatment uses is being waged among psychiatrists, anesthesiologists, family physicians, and emergency physicians. Whoever emerges victorious will determine whether psychiatric care is administered in a safe and cost-effective manner, or if it will merely benefit the bottom line of the prescriber. In this article, we discuss how ketamine may have a role for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), and why psychiatrists are uniquely qualified to prescribe and administer this medication for this purpose.

New approaches to treatment-resistant depression

Antidepressant medications, long the mainstay of depression treatment, have been shown to be safe and relatively equally effective, with varying tolerability. However, 33% percent of patients do not achieve remission after 4 trials of antidepressant therapy.1 Most antidepressant efficacy studies report remission rates of 35% to 40%,2 which means many patients require subsequent switching and/or augmentation of their treatment.3 The STAR*D trial demonstrated that after 2 adequate antidepressant trials, the likelihood of remission diminishes.4

After a patient’s depression is found to be treatment-resistant, the onus of guiding treatment shifts away from the patient’s primary care physician to the more specialized psychiatrist. Few would question the suitability of a psychiatrist’s expertise in handling complicated and nuanced mental illness. In order to manage TRD, psychiatrists enter a terrain of emerging novel therapies with rapid onset, different mechanisms of action, and parenteral routes of administration.

One such therapy is esketamine, the S-enantiomer of ketamine. The FDA approved the intranasal (IN) formulation of esketamine in March 2019 after the medication had been designated as a breakthrough therapy for TRD in 2013 and studied in 6 Phase III clinical trials.5 The S-enantiomer of ketamine is known to bind to the N-methyl-

Ketamine may be administered intranasally, intravenously, or orally. A meta-analysis aimed at assessing differences in ketamine efficacy for depression based on route of administration have shown that both IV and IN ketamine are effective, though it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding a direct comparison based on available data.9 Despite several landmark published studies, such as those by Zarate et al,10 IV ketamine is not FDA-approved for TRD.

Continue to: Why psychiatrists?

Why psychiatrists?

Psychiatrists have been prescribing IN esketamine, which is covered by most commercial insurances and administered in certified healthcare settings under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program.5 However, anesthesiologists and emergency physicians have opened a crop of boutique and concierge health clinics offering various “packages” of IV ketamine infusions for a slew of mental ailments, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.11 Minimal investigation reveals that these services are being prescribed mainly by practitioners in fields other than psychiatry. Intravenous ketamine has long been used off-label as a treatment for depression not by psychiatrists but by practitioners of anesthesiology or emergency medicine. Although these clinicians are likely familiar with ketamine as an anesthetic, they have no foundation or expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of complex mood disorders. The FDA-approved indication for esketamine falls firmly in the realm of psychiatric treatment. Physicians who have not completed a psychiatry residency have neither the training nor experience necessary to determine whether a patient is a candidate for this treatment.

One potential adverse effect of ketamine is an emergence phenomenon, colloquially named a “K-hole,” that can induce symptoms of psychosis such as disturbing hallucinations. Patients who have a history of psychosis need to be carefully evaluated for appropriateness to receive this treatment.

Furthermore, ketamine treatments administered by physicians who are not psychiatrists are billed not through insurance but mostly via private pay. A patient may therefore be charged $350 to $1,000 per infusion, to be paid out of pocket.11 Tally that up over the standard 6 to 12 initial treatment infusions, followed by maintenance infusions, and these patients with profound depression are potentially building up significant debt. Does this practice align with the ethical principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence that all physicians swore to uphold? Will psychiatrists take a stand against the financial exploitation of a vulnerable group that is desperate to find any potential relief from their depression?

1. Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1-21.

2. Fava M, Rush A, Trivedi M, et al. Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(2):457-494.

3. Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Primary versus specialty care outcomes for depressed outpatients managed with measurement-based care: results from STAR*D. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):551-560.

4. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1439-1445.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Esketamine clinical review. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211243Orig1s000MedR.pdf

6. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. Ketamine and ketamine metabolite pharmacology: insights into therapeutic mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(3):621-660.

7. Zanos P, Gould TD. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):801-811.

8. Kaur U, Pathak BK, Singh A, et al. Esketamine: a glimmer of hope in treatment-resistant depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(3):417-429.

9. McIntyre RS, Carvalho IP, Lui LMW, et al. The effect of intravenous, intranasal, and oral ketamine/esketamine in mood disorders: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:576-584.

10. Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856-864.

11. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT+. Published September 18, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/

In the modern-day practice of medicine, turf wars are more common than one may realize. Presently, an ongoing battle over who should be prescribing and administering ketamine for novel treatment uses is being waged among psychiatrists, anesthesiologists, family physicians, and emergency physicians. Whoever emerges victorious will determine whether psychiatric care is administered in a safe and cost-effective manner, or if it will merely benefit the bottom line of the prescriber. In this article, we discuss how ketamine may have a role for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), and why psychiatrists are uniquely qualified to prescribe and administer this medication for this purpose.

New approaches to treatment-resistant depression

Antidepressant medications, long the mainstay of depression treatment, have been shown to be safe and relatively equally effective, with varying tolerability. However, 33% percent of patients do not achieve remission after 4 trials of antidepressant therapy.1 Most antidepressant efficacy studies report remission rates of 35% to 40%,2 which means many patients require subsequent switching and/or augmentation of their treatment.3 The STAR*D trial demonstrated that after 2 adequate antidepressant trials, the likelihood of remission diminishes.4

After a patient’s depression is found to be treatment-resistant, the onus of guiding treatment shifts away from the patient’s primary care physician to the more specialized psychiatrist. Few would question the suitability of a psychiatrist’s expertise in handling complicated and nuanced mental illness. In order to manage TRD, psychiatrists enter a terrain of emerging novel therapies with rapid onset, different mechanisms of action, and parenteral routes of administration.

One such therapy is esketamine, the S-enantiomer of ketamine. The FDA approved the intranasal (IN) formulation of esketamine in March 2019 after the medication had been designated as a breakthrough therapy for TRD in 2013 and studied in 6 Phase III clinical trials.5 The S-enantiomer of ketamine is known to bind to the N-methyl-

Ketamine may be administered intranasally, intravenously, or orally. A meta-analysis aimed at assessing differences in ketamine efficacy for depression based on route of administration have shown that both IV and IN ketamine are effective, though it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding a direct comparison based on available data.9 Despite several landmark published studies, such as those by Zarate et al,10 IV ketamine is not FDA-approved for TRD.

Continue to: Why psychiatrists?

Why psychiatrists?

Psychiatrists have been prescribing IN esketamine, which is covered by most commercial insurances and administered in certified healthcare settings under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program.5 However, anesthesiologists and emergency physicians have opened a crop of boutique and concierge health clinics offering various “packages” of IV ketamine infusions for a slew of mental ailments, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.11 Minimal investigation reveals that these services are being prescribed mainly by practitioners in fields other than psychiatry. Intravenous ketamine has long been used off-label as a treatment for depression not by psychiatrists but by practitioners of anesthesiology or emergency medicine. Although these clinicians are likely familiar with ketamine as an anesthetic, they have no foundation or expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of complex mood disorders. The FDA-approved indication for esketamine falls firmly in the realm of psychiatric treatment. Physicians who have not completed a psychiatry residency have neither the training nor experience necessary to determine whether a patient is a candidate for this treatment.

One potential adverse effect of ketamine is an emergence phenomenon, colloquially named a “K-hole,” that can induce symptoms of psychosis such as disturbing hallucinations. Patients who have a history of psychosis need to be carefully evaluated for appropriateness to receive this treatment.

Furthermore, ketamine treatments administered by physicians who are not psychiatrists are billed not through insurance but mostly via private pay. A patient may therefore be charged $350 to $1,000 per infusion, to be paid out of pocket.11 Tally that up over the standard 6 to 12 initial treatment infusions, followed by maintenance infusions, and these patients with profound depression are potentially building up significant debt. Does this practice align with the ethical principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence that all physicians swore to uphold? Will psychiatrists take a stand against the financial exploitation of a vulnerable group that is desperate to find any potential relief from their depression?

In the modern-day practice of medicine, turf wars are more common than one may realize. Presently, an ongoing battle over who should be prescribing and administering ketamine for novel treatment uses is being waged among psychiatrists, anesthesiologists, family physicians, and emergency physicians. Whoever emerges victorious will determine whether psychiatric care is administered in a safe and cost-effective manner, or if it will merely benefit the bottom line of the prescriber. In this article, we discuss how ketamine may have a role for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), and why psychiatrists are uniquely qualified to prescribe and administer this medication for this purpose.

New approaches to treatment-resistant depression

Antidepressant medications, long the mainstay of depression treatment, have been shown to be safe and relatively equally effective, with varying tolerability. However, 33% percent of patients do not achieve remission after 4 trials of antidepressant therapy.1 Most antidepressant efficacy studies report remission rates of 35% to 40%,2 which means many patients require subsequent switching and/or augmentation of their treatment.3 The STAR*D trial demonstrated that after 2 adequate antidepressant trials, the likelihood of remission diminishes.4

After a patient’s depression is found to be treatment-resistant, the onus of guiding treatment shifts away from the patient’s primary care physician to the more specialized psychiatrist. Few would question the suitability of a psychiatrist’s expertise in handling complicated and nuanced mental illness. In order to manage TRD, psychiatrists enter a terrain of emerging novel therapies with rapid onset, different mechanisms of action, and parenteral routes of administration.

One such therapy is esketamine, the S-enantiomer of ketamine. The FDA approved the intranasal (IN) formulation of esketamine in March 2019 after the medication had been designated as a breakthrough therapy for TRD in 2013 and studied in 6 Phase III clinical trials.5 The S-enantiomer of ketamine is known to bind to the N-methyl-

Ketamine may be administered intranasally, intravenously, or orally. A meta-analysis aimed at assessing differences in ketamine efficacy for depression based on route of administration have shown that both IV and IN ketamine are effective, though it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding a direct comparison based on available data.9 Despite several landmark published studies, such as those by Zarate et al,10 IV ketamine is not FDA-approved for TRD.

Continue to: Why psychiatrists?

Why psychiatrists?

Psychiatrists have been prescribing IN esketamine, which is covered by most commercial insurances and administered in certified healthcare settings under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program.5 However, anesthesiologists and emergency physicians have opened a crop of boutique and concierge health clinics offering various “packages” of IV ketamine infusions for a slew of mental ailments, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.11 Minimal investigation reveals that these services are being prescribed mainly by practitioners in fields other than psychiatry. Intravenous ketamine has long been used off-label as a treatment for depression not by psychiatrists but by practitioners of anesthesiology or emergency medicine. Although these clinicians are likely familiar with ketamine as an anesthetic, they have no foundation or expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of complex mood disorders. The FDA-approved indication for esketamine falls firmly in the realm of psychiatric treatment. Physicians who have not completed a psychiatry residency have neither the training nor experience necessary to determine whether a patient is a candidate for this treatment.

One potential adverse effect of ketamine is an emergence phenomenon, colloquially named a “K-hole,” that can induce symptoms of psychosis such as disturbing hallucinations. Patients who have a history of psychosis need to be carefully evaluated for appropriateness to receive this treatment.

Furthermore, ketamine treatments administered by physicians who are not psychiatrists are billed not through insurance but mostly via private pay. A patient may therefore be charged $350 to $1,000 per infusion, to be paid out of pocket.11 Tally that up over the standard 6 to 12 initial treatment infusions, followed by maintenance infusions, and these patients with profound depression are potentially building up significant debt. Does this practice align with the ethical principles of autonomy, justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence that all physicians swore to uphold? Will psychiatrists take a stand against the financial exploitation of a vulnerable group that is desperate to find any potential relief from their depression?

1. Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1-21.

2. Fava M, Rush A, Trivedi M, et al. Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(2):457-494.

3. Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Primary versus specialty care outcomes for depressed outpatients managed with measurement-based care: results from STAR*D. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):551-560.

4. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1439-1445.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Esketamine clinical review. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211243Orig1s000MedR.pdf

6. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. Ketamine and ketamine metabolite pharmacology: insights into therapeutic mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(3):621-660.

7. Zanos P, Gould TD. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):801-811.

8. Kaur U, Pathak BK, Singh A, et al. Esketamine: a glimmer of hope in treatment-resistant depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(3):417-429.

9. McIntyre RS, Carvalho IP, Lui LMW, et al. The effect of intravenous, intranasal, and oral ketamine/esketamine in mood disorders: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:576-584.

10. Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856-864.

11. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT+. Published September 18, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/

1. Hillhouse TM, Porter JH. A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;23(1):1-21.

2. Fava M, Rush A, Trivedi M, et al. Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(2):457-494.

3. Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Primary versus specialty care outcomes for depressed outpatients managed with measurement-based care: results from STAR*D. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):551-560.

4. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1439-1445.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Esketamine clinical review. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211243Orig1s000MedR.pdf

6. Zanos P, Moaddel R, Morris PJ, et al. Ketamine and ketamine metabolite pharmacology: insights into therapeutic mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70(3):621-660.

7. Zanos P, Gould TD. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):801-811.

8. Kaur U, Pathak BK, Singh A, et al. Esketamine: a glimmer of hope in treatment-resistant depression. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(3):417-429.

9. McIntyre RS, Carvalho IP, Lui LMW, et al. The effect of intravenous, intranasal, and oral ketamine/esketamine in mood disorders: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:576-584.

10. Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856-864.

11. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT+. Published September 18, 2018. Accessed August 5, 2021. www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/

Number of global deaths by suicide increased over 30 years

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four police suicides in the aftermath of the Capitol siege: What can we learn?

Officer Scott Davis is a passionate man who thinks and talks quickly. As a member of the Special Events Team for Montgomery County, Maryland, he was already staging in Rockville, outside of Washington, D.C., when the call came in last Jan. 6 to move their unit to the U.S. Capitol.

“It was surreal,” said Mr. Davis. “There were people from all different groups at the Capitol that day. Many people were trying to get out, but others surrounded us. They called us ‘human race traitors.’ And then I heard someone say, ‘It’s good you brought your shields, we’ll carry your bodies out on them.’”

Mr. Davis described hours of mayhem during which he was hit with bear spray, a brick, a chair, and a metal rod. One of the members of Mr. Davis’ unit remains on leave with a head injury nearly 9 months after the siege.

“It went on for 3 hours, but it felt like 15 minutes. Then, all of a sudden, it was over.”

For the members of law enforcement at the Capitol that day, the repercussions are still being felt, perhaps most notably in the case of the four officers who subsequently died of suicide. Three of the officers were with the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia and one worked for the Capitol Police Department.

Police officers are subjected to traumas on a regular basis and often placed in circumstances where their lives are in danger. Yet four suicides within a short time – all connected to a single event – is particularly shocking and tragic, even more so for how little attention it has garnered to date.

What contributes to the high rate of suicide among officers?

Scott Silverii, PhD, a former police officer and author of Broken and Blue: A Policeman’s Guide to Health, Hope, and Healing, commented that he “wouldn’t be surprised if there are more suicides to come.” This stems not only from the experiences of that day but also the elevated risk for suicide that law enforcement officers already experienced prior to the Capitol riots. Suicide remains a rare event, with a national all-population average of 13.9 per 100,000 citizens. But as Dr. Silverii noted, more officers die by suicide each year than are killed in the line of duty.

“Suicide is a big part of police culture – officers are doers and fixers, and it is seen as being more honorable to take yourself out of the equation than it is to ask for help,” he said. “Most officers come in with past pain, and this is a situation where they are being overwhelmed and under-respected. At the same time, police culture is a closed culture, and it is not friendly to researchers.”

Another contributor is the frequency with which law enforcement officers are exposed to trauma, according to Vernon Herron, Director of Officer Safety and Wellness for the Baltimore City Police.