User login

Parent survey sheds light on suboptimal compliance with eczema medications

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

of children with AD.

Perceived effectiveness was the main driver of this variation, Alan Schwartz PhD, and Korey Capozza, MPH, wrote in the study, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

“Responses suggest parents may be willing to use therapies with concerning side effects if they can see a clear benefit for their child’s eczema, but when anticipated improvements fail to materialize, they may change their usage, usually in the direction of using less medication or stopping,” observed Dr. Schwartz, of the University of Illinois, Chicago, and Ms. Capozza, of Global Parents for Eczema Research.

“Addressing expectations related to effectiveness, rather than concerns about medication use, may thus be more likely to lead to taking medication as directed.”

The researchers posted a 15-question survey on the Facebook page of Global Parents for Eczema Research, an international coalition of parents of children with AD. During the month that the survey was posted, 86 parents completed it; questions pertained to adherence to medications and reasons for changing treatments. The mean age of their children was 6 years, most (about 83%) had moderate or severe eczema, and about half lived in the United States.

More than half (55%) reported using the AD medications as directed. But 30% said they took or applied less than prescribed, 13% had stopped the prescribed medication altogether, and 2% took or applied more (or more often) than prescribed.

There were several reasons stated for this variance. Concern over side effects was the most common (46%) reason for not using medications as directed. The next most common reasons were that the child’s symptoms went away (28%); or the “medication was not helping or was not helping as much,” in 23%.

A lack of physician trust or not agreeing with the physician’s recommendations accounted for 18% of the concerns. The remainder thought it wasn’t important to take the medication as prescribed, it was inconvenient or too time consuming, that they forgot, it was too expensive, or they were confused about the directions.

To the question asking “What would have made you more likely to use the medication as prescribed?” the most common answer was a clearer indication of effectiveness (56%). The next most common was “access to research or evidence about benefit and side effect profile” (14%).

A good relationship between the physician and patient was associated with taking medication as directed

“Improvement in adherence to topical treatments among children with AD could yield large gains in quality-of-life improvements and reduce exposure to costlier and potentially more toxic systemic agents,” the authors noted. “Given the large, documented gains in disease improvement, and even remission, achieved with interventions that address adherence among patients with other chronic diseases, strategies that address the underlying causes for poor adherence among parents of children with atopic dermatitis stand to provide a significant, untapped benefit.”

No financial disclosures were noted.

SOURCE: Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Does this patient have bacterial conjunctivitis?

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

A 54-year-old pharmacist with a history of gout, hypertension, and conjunctivitis presents for evaluation of pink eye in the summer. The morning before coming into the office, he noticed that his right eye was red and inflamed. He self-treated with saline washes and eye drops, but upon awakening the next day, he found his right eye to be crusted shut with surrounding yellow discharge. He has not had any changes to his vision but endorses a somewhat uncomfortable, “gritty” sensation. He reports no recent cough, nasal congestion, or allergies, and he has not been around any sick contacts. His blood pressure is 102/58 mm Hg, pulse is 76 bpm, and body mass index is 27.3 kg/m2. His eye exam reveals unilateral conjunctival injections but no hyperemia of the conjunctiva adjacent to the cornea. Mucopurulent discharge was neither found on the undersurface of the eyelid nor emerging from the eye. Which of the following is the best treatment for this patient’s condition?

A) Erythromycin 5 mg/gram ophthalmic ointment.

B) Ofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic drops.

C) Antihistamine drops.

D) Eye lubricant drops.

E) No treatment necessary.

This patient is an adult presenting with presumed conjunctivitis. Because he is presenting in the summer without observed purulent discharge, his condition is unlikely to be bacterial. This patient does not need treatment, although eye lubricant drops could reduce his discomfort.

After ruling out serious eye disease, clinicians need to determine which cases of suspected conjunctivitis are most likely to be bacterial to allow for judicious use of antibiotic eye drops. This is an important undertaking as most patients assume that antibiotics are needed.

How do we know which history and clinical exam findings to lean on when attempting to categorize conjunctivitis as bacterial or not? If a patient reports purulent discharge, doesn’t that mean it is bacterial? Surprisingly, a systematic review published in 2016 by Narayana and McGee found that a patient’s self-report of “purulent drainage” is diagnostically unhelpful, but if a clinician finds it on exam, the likelihood of a bacterial etiology increases.3

Narayana and McGee analyzed three studies that enrolled a total of 281 patients with presumed conjunctivitis who underwent bacterial cultures. They then determined which findings increased the probability of positive bacterial culture. From strongest to weakest, the best indicators of a bacterial cause were found to be: complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels (the vessels visible on the inside of everted upper or lower eyelids) (likelihood ratio, 4.6), observed purulent discharge (LR, 3.9), matting of both eyes in the morning (LR, 3.6), and presence during winter/spring months (LR, 1.9). On the other hand, failure to observe a red eye at 20 feet (LR, 0.2), absence of morning gluing of either eye (LR, 0.3), and presentation during summer months (LR, 0.4) all decreased the probability of a bacterial cause. This review and different study by Stenson et al. unfortunately have conflicting evidence regarding whether the following findings are diagnostically helpful: qualities of eye discomfort (such as burning or itching), preauricular adenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and conjunctival papillae.3,4 Rietveld and colleagues found that a history of conjunctivitis decreased the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.5

Ultimately, if the former indicators are kept in mind, primary care clinicians should be able to decrease the prescribing of topical antimicrobials to patients with non-bacterial conjunctivitis.

Pearl: The best indicators of a bacterial cause in patients with presumed conjunctivitis are complete redness of the conjunctival membrane obscuring tarsal vessels, observed purulent discharge, and matting of both eyes in the morning. Presentation during the summer months and having a history of conjunctivitis decreases the likelihood of bacterial conjunctivitis.

Ms. Momany is a fourth-year medical student at University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at that university. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Azari AA and Barney NP. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23; 310(16):1721-9.

2. Smith AF and Waycaster C. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13.

3) Narayana S and McGee S. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1220-4.e1.

4) Stenson S et al. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275-7.

5) Rietveld RP et al. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10.

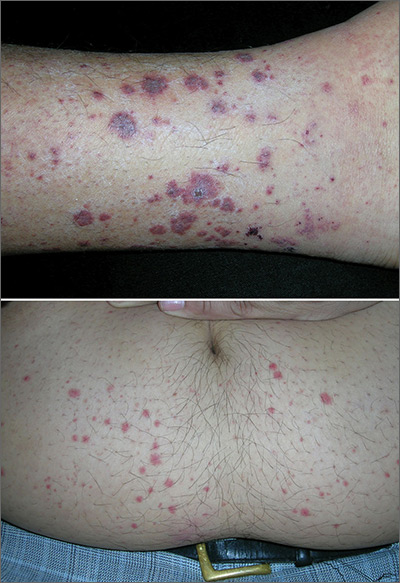

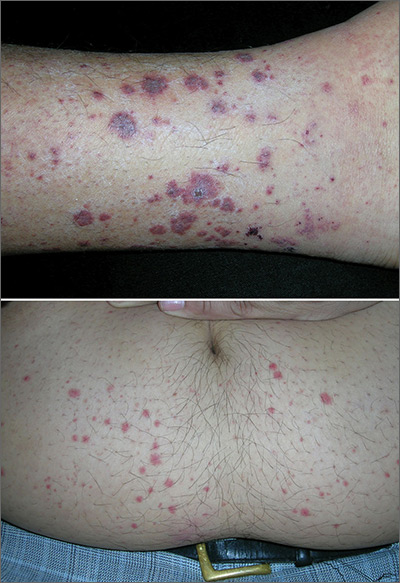

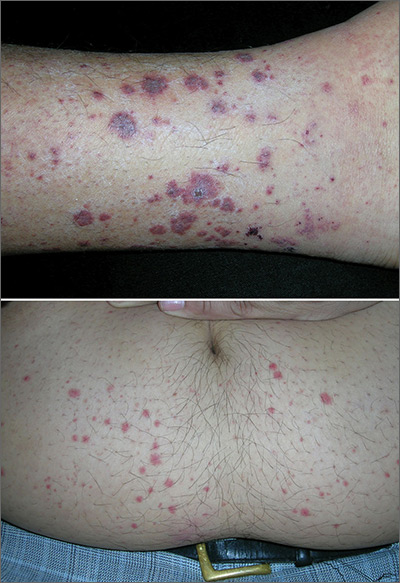

Rash on lower legs and abdomen

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) and, with the patient’s consent, performed a 4-mm punch biopsy on a well-developed lesion on the abdomen. Biopsies on the abdomen heal faster than the legs and may provide a better specimen to the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCV. This is the most commonly seen form of small vessel vasculitis. LCV causes acute inflammation and necrosis of venules in the dermis. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes break apart into fragments. The purpura begins as asymptomatic localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that become palpable.

Discrete lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities, but they may occur on any dependent area. Small lesions may itch and be painful, but nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be more painful. Lesions appear in crops, last for 1 to 4 weeks, and may heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience a single episode caused by a drug reaction or viral infection or have multiple episodes associated with rheumatologic diseases. LCV usually is self-limited and confined to the skin.

To make the diagnosis, look for the presence of 3 or more of the following:

- age > 16 years;

- use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms;

- palpable purpura;

- maculopapular rash; and

- neutrophils around an arteriole or venule in a biopsy of a skin lesion.

In this case, the use of ibuprofen was the most likely precipitating event. Blood and urine tests did not show any renal or other organ system involvement. The patient was warned to not use ibuprofen in the future and that acetaminophen is a safer option for him. He was given topical triamcinolone cream 0.1% to apply twice daily for symptomatic relief. In this case, oral prednisone was not prescribed because the numerous potential adverse effects of prednisone outweighed the benefits. The vasculitis resolved in 4 weeks without any sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R, Martin N, et al. Vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Juvenile dermatomyositis derails growth and pubertal development

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

Children with juvenile dermatomyositis showed significant growth failure and pubertal delay, based on data from a longitudinal cohort study.

“Both the inflammatory activity of this severe chronic rheumatic disease and the well-known side effects of corticosteroid treatment may interfere with normal growth and pubertal development of children,” wrote Ellen Nordal, MD, of the University Hospital of Northern Norway, Tromsø, and colleagues.

The goal in treating juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is to achieve inactive disease and prevent permanent damage, but long-term data on growth and puberty in JDM patients are limited, they wrote.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the investigators reviewed data from 196 children and followed them for 2 years. The patients were part of the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) observational cohort study.

Overall, the researchers identified growth failure, height deflection, and/or delayed puberty in 94 children (48%) at the last study visit.

Growth failure was present at baseline in 17% of girls and 10% of boys. Over the 2-year study period, height deflection increased to 25% of girls and 31% of boys, but this change was not significant. Height deflection was defined as a change in the height z score of less than –0.25 per year from baseline. However, body mass index increased significantly from baseline during the study.

Catch-up growth had occurred by the final study visit in some patients, based on parent-adjusted z scores over time. Girls with a disease duration of 12 months or more showed no catch-up growth at 2 years and had significantly lower parent-adjusted height z scores.

In addition, the researchers observed a delay in the onset of puberty (including pubertal tempo and menarche) in approximately 36% of both boys and girls. However, neither growth failure nor height deflection was significantly associated with delayed puberty in either sex.

“In follow-up, clinicians should therefore be aware of both the pubertal development and the growth of the child, assess the milestones of development, and ensure that the children reach as much as possible of their genetic potential,” the researchers wrote.

The study participants were younger than 18 years at study enrollment, and all were in an active disease phase, defined as needing to start or receive a major dose increase of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Patients were assessed at baseline, at 6 months and/or at 12 months, and during a final visit at approximately 26 months. During the study, approximately half of the participants (50.5%) received methotrexate, 30 (15.3%) received cyclosporine A, 10 (5.1%) received cyclophosphamide, and 27 (13.8%) received intravenous immunoglobulin.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the short follow-up period for assessing pubertal development and the inability to analyze any impact of corticosteroid use prior to the study, the researchers noted. However, “the overall frequency of growth failure was not significantly higher at the final study visit 2 years after baseline, indicating that the very high doses of corticosteroid treatment given during the study period is reasonably well tolerated with regards to growth,” they wrote. But monitoring remains essential, especially for children with previous growth failure or with disease onset early in pubertal development.

The study was supported by the European Union, Helse Nord Research grants, and by IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. Five authors of the study reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Nordal E et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Sep 10. doi: 10.1002/acr.24065.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Pneumonia with tender, dry, crusted lips

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Benefits of peanut desensitization may not last

based on data from a phase 2 randomized trial of individuals with confirmed peanut allergies.

Previous studies have shown that desensitization to peanuts can be successful, but sustained response to oral immunotherapy after treatment reduction or discontinuation has not been well studied, wrote R. Sharon Chinthrajah, MD, of Stanford (Calif.)University, and colleagues.

“We found that OIT with peanut was able to desensitise people with peanut allergy to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, but that discontinuation of peanut, or even a reduction to 300 mg daily, increased the likelihood of regaining clinical reactivity to peanut,” they wrote. “With peanut allergy therapies in varying stages of clinical development, and some nearing [Food and Drug Administration] approval, vital questions remain regarding the durability of treatment effects and the appropriate maintenance doses.”

In the Peanut Oral Immunotherapy Study: Safety Efficacy and Discovery (POISED), published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 120 participants to three groups:

• 60 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by total discontinuation (peanut-0).

• 35 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by a 300-mg maintenance dose of peanut protein in the form of peanut flour (peanut-300).

• 25 patients to an oat flour placebo.

All participants were trained on how and when to use epinephrine autoinjector devices to treat allergic symptoms such as respiratory problems (cough, shortness of breath, or change in voice), widespread hives or erythema, repetitive vomiting, persistent abdominal pain, angioedema of the face, or feeling faint.

The primary outcome was passing a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, which was measured at baseline and at weeks 104, 117, 130, 143, and 156.

Overall, 35% of the peanut-0 group passed the challenge at 104 and 117 weeks, compared with 4% of the placebo group. At week 156 after discontinuing OIT, 13% of the peanut-0 group met the DBPCFC challenge, compared with 4% of the placebo group. However, 37% of participants randomized to a reduced peanut protein dose of 300 mg passed the challenge at 156 weeks, suggesting that more data are needed on optimal maintenance dosing strategies.

Baseline demographics were similar across all groups. The median age at study enrollment was 11 years and the median allergy duration was 9 years. The most common adverse events were mild gastrointestinal and respiratory problems. Adverse events decreased over time in all three groups.

“Higher levels of peanut-specific IgE to total IgE ratio, peanut sIgE, Ara h 1, Ara h 2, and Ara h 1 IgE to peanut-specific IgE ratio at baseline in participants were associated with increased frequencies of adverse events during active peanut OIT,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the ability of participants to tolerate 4,000 mg of peanut protein after achieving a maintenance dose but conducting serial testing only for those who passed the challenge. In addition, the results may be limited to peanut and not generalizable to other food allergies, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that OIT remains a promising treatment for peanut allergies, and the association of biomarkers with clinical outcomes “might help the practitioner in identifying good candidates for OIT and those individuals who warrant increased vigilance against allergic reactions during OIT,” they said.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Chinthrajah RS et al. Lancet. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31793-3.

based on data from a phase 2 randomized trial of individuals with confirmed peanut allergies.

Previous studies have shown that desensitization to peanuts can be successful, but sustained response to oral immunotherapy after treatment reduction or discontinuation has not been well studied, wrote R. Sharon Chinthrajah, MD, of Stanford (Calif.)University, and colleagues.

“We found that OIT with peanut was able to desensitise people with peanut allergy to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, but that discontinuation of peanut, or even a reduction to 300 mg daily, increased the likelihood of regaining clinical reactivity to peanut,” they wrote. “With peanut allergy therapies in varying stages of clinical development, and some nearing [Food and Drug Administration] approval, vital questions remain regarding the durability of treatment effects and the appropriate maintenance doses.”

In the Peanut Oral Immunotherapy Study: Safety Efficacy and Discovery (POISED), published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 120 participants to three groups:

• 60 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by total discontinuation (peanut-0).

• 35 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by a 300-mg maintenance dose of peanut protein in the form of peanut flour (peanut-300).

• 25 patients to an oat flour placebo.

All participants were trained on how and when to use epinephrine autoinjector devices to treat allergic symptoms such as respiratory problems (cough, shortness of breath, or change in voice), widespread hives or erythema, repetitive vomiting, persistent abdominal pain, angioedema of the face, or feeling faint.

The primary outcome was passing a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, which was measured at baseline and at weeks 104, 117, 130, 143, and 156.

Overall, 35% of the peanut-0 group passed the challenge at 104 and 117 weeks, compared with 4% of the placebo group. At week 156 after discontinuing OIT, 13% of the peanut-0 group met the DBPCFC challenge, compared with 4% of the placebo group. However, 37% of participants randomized to a reduced peanut protein dose of 300 mg passed the challenge at 156 weeks, suggesting that more data are needed on optimal maintenance dosing strategies.

Baseline demographics were similar across all groups. The median age at study enrollment was 11 years and the median allergy duration was 9 years. The most common adverse events were mild gastrointestinal and respiratory problems. Adverse events decreased over time in all three groups.

“Higher levels of peanut-specific IgE to total IgE ratio, peanut sIgE, Ara h 1, Ara h 2, and Ara h 1 IgE to peanut-specific IgE ratio at baseline in participants were associated with increased frequencies of adverse events during active peanut OIT,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the ability of participants to tolerate 4,000 mg of peanut protein after achieving a maintenance dose but conducting serial testing only for those who passed the challenge. In addition, the results may be limited to peanut and not generalizable to other food allergies, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that OIT remains a promising treatment for peanut allergies, and the association of biomarkers with clinical outcomes “might help the practitioner in identifying good candidates for OIT and those individuals who warrant increased vigilance against allergic reactions during OIT,” they said.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Chinthrajah RS et al. Lancet. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31793-3.

based on data from a phase 2 randomized trial of individuals with confirmed peanut allergies.

Previous studies have shown that desensitization to peanuts can be successful, but sustained response to oral immunotherapy after treatment reduction or discontinuation has not been well studied, wrote R. Sharon Chinthrajah, MD, of Stanford (Calif.)University, and colleagues.

“We found that OIT with peanut was able to desensitise people with peanut allergy to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, but that discontinuation of peanut, or even a reduction to 300 mg daily, increased the likelihood of regaining clinical reactivity to peanut,” they wrote. “With peanut allergy therapies in varying stages of clinical development, and some nearing [Food and Drug Administration] approval, vital questions remain regarding the durability of treatment effects and the appropriate maintenance doses.”

In the Peanut Oral Immunotherapy Study: Safety Efficacy and Discovery (POISED), published in The Lancet, the researchers randomized 120 participants to three groups:

• 60 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by total discontinuation (peanut-0).

• 35 patients built up to a maintenance dose of 4,000 mg of peanut protein for 104 weeks followed by a 300-mg maintenance dose of peanut protein in the form of peanut flour (peanut-300).

• 25 patients to an oat flour placebo.

All participants were trained on how and when to use epinephrine autoinjector devices to treat allergic symptoms such as respiratory problems (cough, shortness of breath, or change in voice), widespread hives or erythema, repetitive vomiting, persistent abdominal pain, angioedema of the face, or feeling faint.

The primary outcome was passing a double-blind, placebo-controlled, food challenge (DBPCFC) to 4,000 mg of peanut protein, which was measured at baseline and at weeks 104, 117, 130, 143, and 156.

Overall, 35% of the peanut-0 group passed the challenge at 104 and 117 weeks, compared with 4% of the placebo group. At week 156 after discontinuing OIT, 13% of the peanut-0 group met the DBPCFC challenge, compared with 4% of the placebo group. However, 37% of participants randomized to a reduced peanut protein dose of 300 mg passed the challenge at 156 weeks, suggesting that more data are needed on optimal maintenance dosing strategies.

Baseline demographics were similar across all groups. The median age at study enrollment was 11 years and the median allergy duration was 9 years. The most common adverse events were mild gastrointestinal and respiratory problems. Adverse events decreased over time in all three groups.

“Higher levels of peanut-specific IgE to total IgE ratio, peanut sIgE, Ara h 1, Ara h 2, and Ara h 1 IgE to peanut-specific IgE ratio at baseline in participants were associated with increased frequencies of adverse events during active peanut OIT,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the ability of participants to tolerate 4,000 mg of peanut protein after achieving a maintenance dose but conducting serial testing only for those who passed the challenge. In addition, the results may be limited to peanut and not generalizable to other food allergies, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that OIT remains a promising treatment for peanut allergies, and the association of biomarkers with clinical outcomes “might help the practitioner in identifying good candidates for OIT and those individuals who warrant increased vigilance against allergic reactions during OIT,” they said.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Chinthrajah RS et al. Lancet. 2019 Sep 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31793-3.

FROM THE LANCET

When Life’s an Itch

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no acute distress. She is, however, quite upset with the widespread collections of vesicles on mildly erythematous bases, many in a linear configuration. In several areas, there is ecchymosis secondary to scratching.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Poison ivy, or Rhus dermatitis, is one of the most common dermatologic problems seen in medicine—and yet, its various presentations can, as this case illustrates, be quite confusing. Even when it is recognized, treatment is far from satisfactory (but more on that later). Furthermore, there is a lot of misinformation about everything from the appearance of the offending plant to the condition’s “contagious” nature.

From a broader perspective, poison ivy is becoming more prevalent and its effects more pronounced as cities expand into formerly open country. The Rhus plant family (Toxicodendron radicans and others) thrives on our increasing levels of CO2, effectively making the “poisonous” resin in the stems, leaves, and berries more potent.

With repeated exposure, the vast majority of the population will develop an allergy to this resin, known as urushiol, which can persist even on long-dead plants, vines, and leaves. (It does take repeated exposure to develop the requisite T-cell population, which is why many children are immune to it.) The urushiol does not serve as a protective substance for the plant; rather, it helps the plant retain water. In fact, many animals feed on the plant with impunity.

Virtually all members of the poison ivy family display “leaves of three” emerging from a single stem, with each triplet alternating first on one side of the branch and then on the other. Several varieties of the plant flourish over vast areas of the world, but in the United States, east of the Rockies, Toxicodendron radicans is the dominant member of the family. It can grow as a low vine, a shrub, or a climbing vine, each with a distinct appearance aside from the leaves, which are almond-shaped, smooth, and usually shiny with smooth surfaces. Most mature leaves will have a single notch, sometimes called a “thumb,” on otherwise smooth, nonserrated edges. In the summer, tiny white and yellow berries begin to grow.

The climbing vines of older plants can reach heights of 10 meters or more. These vines can reach a thickness of 3 inches and often appear “furry,” with tiny rootlets covering their surfaces. Plants this large can produce leaves 12 to 14 inches long.

Clinically, the appearance of linear pink to red pruritic vesicular streaks typify this contact dermatitis, which can immediately follow exposure or take days to appear. Said exposure can be direct or via pets, tools, or aerosols (eg, from neighbors mowing their lawns). Besides avoidance of the great outdoors, washing thoroughly immediately after exposure makes sense (but many are unaware that they’ve been exposed until it’s too late).

Poison ivy is not contagious, though the general public firmly believes otherwise. Left untreated, it clears within 2 weeks (except in unusual cases). For those who cannot bear to wait, treatment is problematic, to say the least. OTC products, such as calamine lotion, do nothing for the itching but may help with blistering. Topical or systemic steroids reduce itching somewhat. Antihistamines are useless, since this condition does not involve histamine release.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poison ivy (Rhus dermatitis) is quite common and becoming more so due to encroaching civilization and increasing CO2 levels.

- “Leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice, because the poison ivy plant Toxicodendron radicans manifests with three almond-shaped, shiny, green leaves grouped in threes.

- Urushiol is the name of the oily resin found in the plant’s stem, leaves, and berries, and is the trigger resulting in contact dermatitis.

- Poison ivy is not contagious and typically clears in 2 weeks.

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no acute distress. She is, however, quite upset with the widespread collections of vesicles on mildly erythematous bases, many in a linear configuration. In several areas, there is ecchymosis secondary to scratching.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Poison ivy, or Rhus dermatitis, is one of the most common dermatologic problems seen in medicine—and yet, its various presentations can, as this case illustrates, be quite confusing. Even when it is recognized, treatment is far from satisfactory (but more on that later). Furthermore, there is a lot of misinformation about everything from the appearance of the offending plant to the condition’s “contagious” nature.

From a broader perspective, poison ivy is becoming more prevalent and its effects more pronounced as cities expand into formerly open country. The Rhus plant family (Toxicodendron radicans and others) thrives on our increasing levels of CO2, effectively making the “poisonous” resin in the stems, leaves, and berries more potent.

With repeated exposure, the vast majority of the population will develop an allergy to this resin, known as urushiol, which can persist even on long-dead plants, vines, and leaves. (It does take repeated exposure to develop the requisite T-cell population, which is why many children are immune to it.) The urushiol does not serve as a protective substance for the plant; rather, it helps the plant retain water. In fact, many animals feed on the plant with impunity.

Virtually all members of the poison ivy family display “leaves of three” emerging from a single stem, with each triplet alternating first on one side of the branch and then on the other. Several varieties of the plant flourish over vast areas of the world, but in the United States, east of the Rockies, Toxicodendron radicans is the dominant member of the family. It can grow as a low vine, a shrub, or a climbing vine, each with a distinct appearance aside from the leaves, which are almond-shaped, smooth, and usually shiny with smooth surfaces. Most mature leaves will have a single notch, sometimes called a “thumb,” on otherwise smooth, nonserrated edges. In the summer, tiny white and yellow berries begin to grow.

The climbing vines of older plants can reach heights of 10 meters or more. These vines can reach a thickness of 3 inches and often appear “furry,” with tiny rootlets covering their surfaces. Plants this large can produce leaves 12 to 14 inches long.

Clinically, the appearance of linear pink to red pruritic vesicular streaks typify this contact dermatitis, which can immediately follow exposure or take days to appear. Said exposure can be direct or via pets, tools, or aerosols (eg, from neighbors mowing their lawns). Besides avoidance of the great outdoors, washing thoroughly immediately after exposure makes sense (but many are unaware that they’ve been exposed until it’s too late).

Poison ivy is not contagious, though the general public firmly believes otherwise. Left untreated, it clears within 2 weeks (except in unusual cases). For those who cannot bear to wait, treatment is problematic, to say the least. OTC products, such as calamine lotion, do nothing for the itching but may help with blistering. Topical or systemic steroids reduce itching somewhat. Antihistamines are useless, since this condition does not involve histamine release.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poison ivy (Rhus dermatitis) is quite common and becoming more so due to encroaching civilization and increasing CO2 levels.

- “Leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice, because the poison ivy plant Toxicodendron radicans manifests with three almond-shaped, shiny, green leaves grouped in threes.

- Urushiol is the name of the oily resin found in the plant’s stem, leaves, and berries, and is the trigger resulting in contact dermatitis.

- Poison ivy is not contagious and typically clears in 2 weeks.

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.