User login

New evidence supports immune system involvement in hidradenitis suppurativa

Immune dysregulation is a substantial feature of hidradenitis suppurativa in African American patients, according to data from 16 adults.

The etiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) remains unknown, but neutrophils are prominent in affected areas of skin, wrote Angel S. Byrd, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Among the several functions of neutrophils, these cells have the ability to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) after exposure to certain microbes or sterile stimuli,” the researchers noted. These NETs are weblike structures that have been shown to activate several types of immune responses and promote inflammation.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers analyzed biospecimens from African American HS patients. They determined that NET structures were present in the lesional skin of HS patients, but not in control skin. Additionally, serum from HS patients did not properly degrade healthy control NETs in an in vitro examination.

A significant correlation (P less than .0001) occurred between the amount of NETs released in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions and hidradenitis suppurativa severity.

“Together, these results indicate that NET formation is enhanced in HS, both systemically and in lesional skin, in association with disease severity and that NET degradation mechanisms may be impaired in this disease,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also found that total immunoglobulin G was significantly increased in the sera of HS patients, compared with that of healthy volunteers (P = .0011), and that enzymes involved in skin citrullination were elevated in the skin of HS patients, compared with controls’ skin.

Previous studies have shown that NETs can promote type I interferon (IFN) signatures in the blood of patients with autoimmune and chronic inflammatory conditions, and in this study, several type I IFN–regulated genes had increased expression in HS skin, including IFI44L, MX1, CXCL10, RSAD2, and IFI27.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and homogenous population, the researchers noted. Future research should include “the role that neutrophil/type I IFN dysregulation plays in the clinical manifestations of the disease, and how these abnormalities in immune responses regulate other innate and adaptive immune cell types in HS,” which could affect the development of new treatments, they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Physician Scientist Training Program, and the Danby Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. Dr. Byrd disclosed participating in the Johns Hopkins Ethnic Skin Fellowship, which was supported in part by Valeant. Dr. Byrd also disclosed serving as a former investigator for Eli Lilly.

SOURCE: Byrd AS et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5908.

Immune dysregulation is a substantial feature of hidradenitis suppurativa in African American patients, according to data from 16 adults.

The etiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) remains unknown, but neutrophils are prominent in affected areas of skin, wrote Angel S. Byrd, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Among the several functions of neutrophils, these cells have the ability to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) after exposure to certain microbes or sterile stimuli,” the researchers noted. These NETs are weblike structures that have been shown to activate several types of immune responses and promote inflammation.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers analyzed biospecimens from African American HS patients. They determined that NET structures were present in the lesional skin of HS patients, but not in control skin. Additionally, serum from HS patients did not properly degrade healthy control NETs in an in vitro examination.

A significant correlation (P less than .0001) occurred between the amount of NETs released in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions and hidradenitis suppurativa severity.

“Together, these results indicate that NET formation is enhanced in HS, both systemically and in lesional skin, in association with disease severity and that NET degradation mechanisms may be impaired in this disease,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also found that total immunoglobulin G was significantly increased in the sera of HS patients, compared with that of healthy volunteers (P = .0011), and that enzymes involved in skin citrullination were elevated in the skin of HS patients, compared with controls’ skin.

Previous studies have shown that NETs can promote type I interferon (IFN) signatures in the blood of patients with autoimmune and chronic inflammatory conditions, and in this study, several type I IFN–regulated genes had increased expression in HS skin, including IFI44L, MX1, CXCL10, RSAD2, and IFI27.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and homogenous population, the researchers noted. Future research should include “the role that neutrophil/type I IFN dysregulation plays in the clinical manifestations of the disease, and how these abnormalities in immune responses regulate other innate and adaptive immune cell types in HS,” which could affect the development of new treatments, they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Physician Scientist Training Program, and the Danby Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. Dr. Byrd disclosed participating in the Johns Hopkins Ethnic Skin Fellowship, which was supported in part by Valeant. Dr. Byrd also disclosed serving as a former investigator for Eli Lilly.

SOURCE: Byrd AS et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5908.

Immune dysregulation is a substantial feature of hidradenitis suppurativa in African American patients, according to data from 16 adults.

The etiology of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) remains unknown, but neutrophils are prominent in affected areas of skin, wrote Angel S. Byrd, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Among the several functions of neutrophils, these cells have the ability to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) after exposure to certain microbes or sterile stimuli,” the researchers noted. These NETs are weblike structures that have been shown to activate several types of immune responses and promote inflammation.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers analyzed biospecimens from African American HS patients. They determined that NET structures were present in the lesional skin of HS patients, but not in control skin. Additionally, serum from HS patients did not properly degrade healthy control NETs in an in vitro examination.

A significant correlation (P less than .0001) occurred between the amount of NETs released in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions and hidradenitis suppurativa severity.

“Together, these results indicate that NET formation is enhanced in HS, both systemically and in lesional skin, in association with disease severity and that NET degradation mechanisms may be impaired in this disease,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers also found that total immunoglobulin G was significantly increased in the sera of HS patients, compared with that of healthy volunteers (P = .0011), and that enzymes involved in skin citrullination were elevated in the skin of HS patients, compared with controls’ skin.

Previous studies have shown that NETs can promote type I interferon (IFN) signatures in the blood of patients with autoimmune and chronic inflammatory conditions, and in this study, several type I IFN–regulated genes had increased expression in HS skin, including IFI44L, MX1, CXCL10, RSAD2, and IFI27.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size and homogenous population, the researchers noted. Future research should include “the role that neutrophil/type I IFN dysregulation plays in the clinical manifestations of the disease, and how these abnormalities in immune responses regulate other innate and adaptive immune cell types in HS,” which could affect the development of new treatments, they wrote.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Physician Scientist Training Program, and the Danby Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. Dr. Byrd disclosed participating in the Johns Hopkins Ethnic Skin Fellowship, which was supported in part by Valeant. Dr. Byrd also disclosed serving as a former investigator for Eli Lilly.

SOURCE: Byrd AS et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Sep 4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5908.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Rash on the thigh

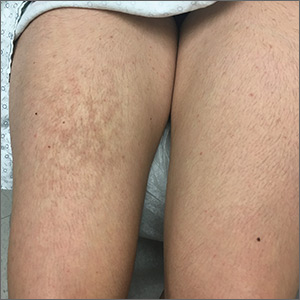

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

A 21-year-old woman presented with a rash on her right thigh of 3 to 4 months’ duration. She reported that the patch was asymptomatic. She was not taking any medications and otherwise was in good health. A review of systems was negative. The patient was a student who used her laptop frequently. On physical examination, a 10×5-cm reticulated, hyperpigmented patch was seen on her right thigh (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a common dermatosis caused by repeated exposure to infrared radiation, most commonly in the form of low-grade heat (43–47°C).1 Common heat sources include heating pads, heaters, fire, and battery-charged devices. The distribution of the rash is dependent on the location of the heat source and appears as a hyperpigmented, reticulated rash. The pathophysiology is not well understood, but likely involves changes in dermal elastic fibers as well as the dermal venous plexus.2 Though rare, chronic cases of EAI have been associated with cutaneous dysplasia.3

Diagnosis of EAI is made by a combination of medical history and clinical features. Laboratory tests are not required. Additionally, clinicians should inquire about possible heat sources. In this case, we asked the patient whether she rested anything on her thighs, and she acknowledged that this was where she typically placed her laptop computer.

Differential includes other reticulated conditions

The differential diagnosis of a reticulated patch includes other entities likely sharing vascular pathology. The age, sex, and medical history of the patient offer additional diagnostic clues.

Livedo reticularis presents with reticulated erythema. It is unrelated to heat exposure, but may be associated with cold exposure. It can be physiologic or can be associated with vasculitis or another obstruction of blood flow.

Erythema infectiosum is a parvovirus B19 infection that usually presents in young children. It often results in a lacy reticulated exanthem on the face that resembles a slapped cheek in children. Adolescent and adult contacts often present with a more petechial rash in an acral to periflexural distribution.4

Continue to: Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium arteries with an incidence of 4 to 16 cases per million.4 It usually is painful and can present with nodules, ulcers, or bullae and may be associated with livedo-like reticulated pigmentation.

Livedoid vasculitis is a hyalinization of blood vessels leading to the obstruction of vessels due to a hypercoagulable state. It can be acquired or congenital and usually manifests in middle-aged women.4

Management is straight-forward: Remove the heat source

EAI typically is asymptomatic, although there are reports of mild pruritus or a burning sensation. Management includes withdrawal of the heat source and patient education. Our patient’s rash went away when she stopped resting her laptop computer on her lap.

CORRESPONDENCE

Lorraine C. Young, MD, 200 UCLA, Medical Plaza Driveway, Suites 450 & 465, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected]

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

1. Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

2. Salgado F, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Erythema ab igne: new technology rebounding upon its users? Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:393-396.

3. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678.

4. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

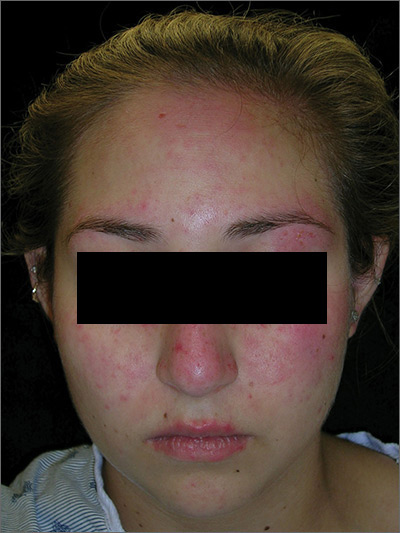

Rash on face, chest, upper arms, and thighs

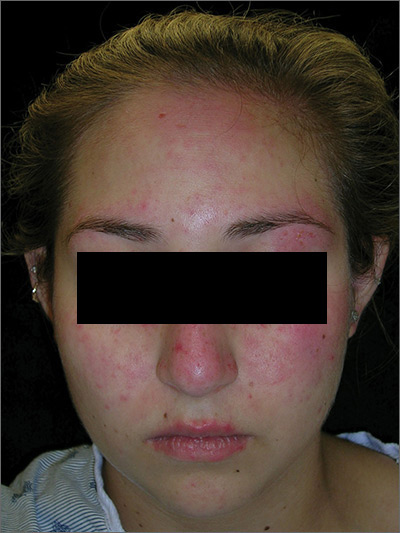

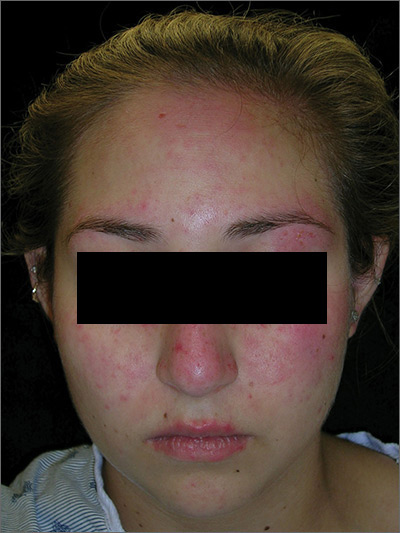

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The FP suspected acute systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with an acute cutaneous component. Laboratory testing showed a very high level of antinuclear antibodies. The patient was referred to Rheumatology and Dermatology. The dermatologist was available for a phone consult and suggested starting the patient on prednisone 60 mg/d as the Medrol Dosepak that the patient previously received had insufficient prednisolone for this severe flare of acute cutaneous lupus.

Although the classic description of acute SLE involves a butterfly rash, the rash of acute cutaneous lupus can include other areas of the face and body. As was seen in this case, the nasolabial fold tends to be spared and there are often skin erosions and crusting.

Based on the patient’s lab tests and symptoms, the dermatologist determined that the patient met the criteria for SLE. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. The plan was to taper the patient’s prednisone slowly. By the following week, her skin and fatigue were much improved.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Pye A, Mayeaux EJ, Mishra V, et al. Lupus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1183-1193.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

Diabetic dyslipidemia with eruptive xanthoma

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

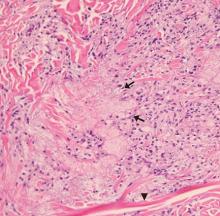

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

Cephalosporins remain empiric therapy for skin infections in pediatric AD

“Clindamycin, tetracyclines, or TMP‐SMX can be considered in patients suspected to have, or with a history of, MRSA [methicillin‐resistant S. aureus] infection,” wrote Cristopher C. Briscoe, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and his coauthors. The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology.

To determine the optimal empiric antibiotic for pediatric AD patients with skin infections, the researchers analyzed skin cultures from 106 patients seen at Saint Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH). The results were also compared to cultures from pediatric patients who presented at the SLCH emergency department (ED) with S. aureus skin abscesses.

Of the 170 cultures that grew S. aureus, 130 (77.8%) grew MSSA, and 37 (22.2%) grew MRSA. Three of the cultures grew both. The prevalence of MRSA in the cohort differed from the prevalence in the ED patients (44%). The prevalence of either infection did not differ significantly by age, sex or race, though the average number of cultures in African American patients topped the average for Caucasian patients (1.8 vs. 1.2, P less than .003).

All patients with MSSA – in both the cohort and the ED – proved 100% susceptible to cefazolin. Cohort patients with MSSA saw lower susceptibility to doxycycline compared to the ED patients (89.4% vs. 97%), as did MRSA cohort patients to trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole (92% vs. 98%).

“When a patient with AD walks into your office and looks like they have an infection of their eczema, your go-to antibiotic is going to be one that targets MSSA,” said coauthor Carrie Coughlin, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in an interview. “You’ll still do a culture to prove or disprove that assumption, but it gives you a guide to help make that patient better in the short term while you work things up.”

“Also, remember that MSSA is not ‘better’ to have than MRSA,” she added. “You can now see some of the virulence factors from MRSA strains in MSSA strains, so treating both of them is important.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the limited generalizability of a single-center design and a lack of information as to the body sites from which the cultures were obtained. They were also unable to reliably determine prior antibiotic exposure, noting that “future work could examine whether prior exposure differed significantly in the MRSA and MSSA groups.”

The study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Briscoe CC et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 May 24. doi: 10.1111/pde.13867.

“Clindamycin, tetracyclines, or TMP‐SMX can be considered in patients suspected to have, or with a history of, MRSA [methicillin‐resistant S. aureus] infection,” wrote Cristopher C. Briscoe, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and his coauthors. The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology.

To determine the optimal empiric antibiotic for pediatric AD patients with skin infections, the researchers analyzed skin cultures from 106 patients seen at Saint Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH). The results were also compared to cultures from pediatric patients who presented at the SLCH emergency department (ED) with S. aureus skin abscesses.

Of the 170 cultures that grew S. aureus, 130 (77.8%) grew MSSA, and 37 (22.2%) grew MRSA. Three of the cultures grew both. The prevalence of MRSA in the cohort differed from the prevalence in the ED patients (44%). The prevalence of either infection did not differ significantly by age, sex or race, though the average number of cultures in African American patients topped the average for Caucasian patients (1.8 vs. 1.2, P less than .003).

All patients with MSSA – in both the cohort and the ED – proved 100% susceptible to cefazolin. Cohort patients with MSSA saw lower susceptibility to doxycycline compared to the ED patients (89.4% vs. 97%), as did MRSA cohort patients to trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole (92% vs. 98%).

“When a patient with AD walks into your office and looks like they have an infection of their eczema, your go-to antibiotic is going to be one that targets MSSA,” said coauthor Carrie Coughlin, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in an interview. “You’ll still do a culture to prove or disprove that assumption, but it gives you a guide to help make that patient better in the short term while you work things up.”

“Also, remember that MSSA is not ‘better’ to have than MRSA,” she added. “You can now see some of the virulence factors from MRSA strains in MSSA strains, so treating both of them is important.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the limited generalizability of a single-center design and a lack of information as to the body sites from which the cultures were obtained. They were also unable to reliably determine prior antibiotic exposure, noting that “future work could examine whether prior exposure differed significantly in the MRSA and MSSA groups.”

The study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Briscoe CC et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 May 24. doi: 10.1111/pde.13867.

“Clindamycin, tetracyclines, or TMP‐SMX can be considered in patients suspected to have, or with a history of, MRSA [methicillin‐resistant S. aureus] infection,” wrote Cristopher C. Briscoe, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and his coauthors. The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology.

To determine the optimal empiric antibiotic for pediatric AD patients with skin infections, the researchers analyzed skin cultures from 106 patients seen at Saint Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH). The results were also compared to cultures from pediatric patients who presented at the SLCH emergency department (ED) with S. aureus skin abscesses.

Of the 170 cultures that grew S. aureus, 130 (77.8%) grew MSSA, and 37 (22.2%) grew MRSA. Three of the cultures grew both. The prevalence of MRSA in the cohort differed from the prevalence in the ED patients (44%). The prevalence of either infection did not differ significantly by age, sex or race, though the average number of cultures in African American patients topped the average for Caucasian patients (1.8 vs. 1.2, P less than .003).

All patients with MSSA – in both the cohort and the ED – proved 100% susceptible to cefazolin. Cohort patients with MSSA saw lower susceptibility to doxycycline compared to the ED patients (89.4% vs. 97%), as did MRSA cohort patients to trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole (92% vs. 98%).

“When a patient with AD walks into your office and looks like they have an infection of their eczema, your go-to antibiotic is going to be one that targets MSSA,” said coauthor Carrie Coughlin, MD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in an interview. “You’ll still do a culture to prove or disprove that assumption, but it gives you a guide to help make that patient better in the short term while you work things up.”

“Also, remember that MSSA is not ‘better’ to have than MRSA,” she added. “You can now see some of the virulence factors from MRSA strains in MSSA strains, so treating both of them is important.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the limited generalizability of a single-center design and a lack of information as to the body sites from which the cultures were obtained. They were also unable to reliably determine prior antibiotic exposure, noting that “future work could examine whether prior exposure differed significantly in the MRSA and MSSA groups.”

The study was funded by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Briscoe CC et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 May 24. doi: 10.1111/pde.13867.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Tender nodules after leprosy Tx

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

The treating physicians believed that the patient had developed erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), based on the tender nodules that are characteristic of this treatment reaction. The CDC was again consulted and representatives there agreed.

ENL is a known as a Type 2 reaction to the treatment for leprosy. Management involves the use of oral prednisone, which may be needed for a prolonged time. The antibiotics used to treat leprosy should not be stopped, as ENL is not an allergic reaction. It is due to the destruction of bacilli and the immune response to the release of bacterial antigens.

The patient was transferred to a leprosy hospital in Baton Rouge, Louisiana for further management. The prednisone was not sufficient, and he required further treatment with thalidomide. After 2 years of treatment, he appeared to be free of leprosy and no longer had the ENL.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Diaz L, Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1169-1173.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the third edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: https://usatinemedia.com/app/color-atlas-of-family-medicine/

An Atypical Problem for Atopical People

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

FDA approves Taltz for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis

(AS), according to a press release from Eli Lilly.

AS is the third indication for ixekizumab, along with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and active psoriatic arthritis in adults.

Approval of the humanized interleukin-17A antagonist was based on results from a pair of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies involving 657 adult patients with active AS: the COAST-V trial in those naive to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) and the COAST-W trial in those who were intolerant or had inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. The primary endpoint in both trials was achievement of 40% improvement in Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society criteria (ASAS40) at 16 weeks, compared with placebo.

In COAST-V, 48% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40, compared with 18% of controls (P less than .0001). In COAST-W, 25% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40 versus 13% of controls (P less than .05). The adverse events reported during both trials were consistent with the safety profile in patients who receive ixekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, including injection-site reactions, upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and tinea infections.

“Results from the phase 3 clinical trial program in ankylosing spondylitis show that Taltz helped reduce pain and inflammation and improve function in patients who had never been treated with a bDMARD as well as those who previously failed TNF inhibitors. This approval is an important milestone for patients and physicians who are looking for a much-needed alternative to address symptoms of AS,” said Philip Mease, MD, of Providence St. Joseph Health and the University of Washington, both in Seattle.

(AS), according to a press release from Eli Lilly.

AS is the third indication for ixekizumab, along with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and active psoriatic arthritis in adults.

Approval of the humanized interleukin-17A antagonist was based on results from a pair of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies involving 657 adult patients with active AS: the COAST-V trial in those naive to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) and the COAST-W trial in those who were intolerant or had inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. The primary endpoint in both trials was achievement of 40% improvement in Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society criteria (ASAS40) at 16 weeks, compared with placebo.

In COAST-V, 48% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40, compared with 18% of controls (P less than .0001). In COAST-W, 25% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40 versus 13% of controls (P less than .05). The adverse events reported during both trials were consistent with the safety profile in patients who receive ixekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, including injection-site reactions, upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and tinea infections.

“Results from the phase 3 clinical trial program in ankylosing spondylitis show that Taltz helped reduce pain and inflammation and improve function in patients who had never been treated with a bDMARD as well as those who previously failed TNF inhibitors. This approval is an important milestone for patients and physicians who are looking for a much-needed alternative to address symptoms of AS,” said Philip Mease, MD, of Providence St. Joseph Health and the University of Washington, both in Seattle.

(AS), according to a press release from Eli Lilly.

AS is the third indication for ixekizumab, along with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and active psoriatic arthritis in adults.

Approval of the humanized interleukin-17A antagonist was based on results from a pair of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies involving 657 adult patients with active AS: the COAST-V trial in those naive to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) and the COAST-W trial in those who were intolerant or had inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. The primary endpoint in both trials was achievement of 40% improvement in Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society criteria (ASAS40) at 16 weeks, compared with placebo.

In COAST-V, 48% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40, compared with 18% of controls (P less than .0001). In COAST-W, 25% of patients who received ixekizumab achieved ASAS40 versus 13% of controls (P less than .05). The adverse events reported during both trials were consistent with the safety profile in patients who receive ixekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, including injection-site reactions, upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and tinea infections.

“Results from the phase 3 clinical trial program in ankylosing spondylitis show that Taltz helped reduce pain and inflammation and improve function in patients who had never been treated with a bDMARD as well as those who previously failed TNF inhibitors. This approval is an important milestone for patients and physicians who are looking for a much-needed alternative to address symptoms of AS,” said Philip Mease, MD, of Providence St. Joseph Health and the University of Washington, both in Seattle.

Hidradenitis suppurativa linked to higher NAFLD risk

independent of other metabolic risk factors, a study has found.

The results of the case-control study of 70 individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and 150 age- and gender-matched controls were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Using hepatic ultrasonography and transient elastography, the investigators found that 51 (72.9%) the participants with HS also had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), compared with 37 (24.7%) of the controls (P less than .001).

Those with HS and NAFLD were more likely to be obese, have more central adiposity, and meet more of the criteria for metabolic syndrome than those with HS but without NAFLD. They also showed higher serum ALT levels, higher triglycerides, and higher controlled attenuation parameter scores, which is a surrogate marker of liver steatosis.

However, the HS plus NAFLD group had similar rates of active smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular events, compared with those who had HS only. They also showed no differences in hemoglobin A1c, serum insulin, insulin resistance, or liver stiffness, compared with the HS-only group.

When researchers compared the participants with HS plus NAFLD with controls with NAFLD, they found the HS group had significantly higher levels of liver stiffness measurement, which is a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis and severity, but there were no differences in the degree of hepatic steatosis.

The individuals with HS plus NAFLD had significantly lower serum albumin, but significantly higher serum gamma–glutamyl transpeptidase and ferritin, compared with controls who had NAFLD. They were also more likely to have metabolic risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.

The multivariate analysis also showed that male sex was a protective factor, because the prevalence of obesity was higher in women.

After adjusting for classic cardiovascular and steatosis risk factors, the researchers calculated that HS was a significant and independent risk factor for NAFLD, with an odds ratio of 7.75 (P less than .001). The results provide “the first evidence that patients with HS have a significant high prevalence of NAFLD, which is independent of classic metabolic risk factors and, according to our results, probably not related to the severity of the disease,” wrote Carlos Durán-Vian, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, and coauthors.

“We think that our findings might have potential clinical implications, and physicians involved in the care of patients with HS should be aware of the link between this entity and NAFLD, in order to improve the overall management of these patients,” they wrote, noting that HS is often associated with the same metabolic disorders that can promote fatty liver disease, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome. But the discovery that it is an independent risk factor demands other hypotheses to explain the association between the two conditions.

“In this sense, a possible explanation to deeper understanding the link between HS and NAFLD could be the presence of chronic inflammation due to persistent and abnormal secretion of adipokines (i.e. adiponectin, leptin, resistin) and several proinflammatory cytokines,” the authors wrote, pointing out that NAFLD is also common among people with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

The study had the limitation of being an observational, cross-sectional design, and the authors acknowledged that the cohort was relatively small. They also were unable to use liver biopsies to confirm the NAFLD diagnosis.

No funding or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Durán-Vian C et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15764.

independent of other metabolic risk factors, a study has found.

The results of the case-control study of 70 individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and 150 age- and gender-matched controls were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Using hepatic ultrasonography and transient elastography, the investigators found that 51 (72.9%) the participants with HS also had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), compared with 37 (24.7%) of the controls (P less than .001).

Those with HS and NAFLD were more likely to be obese, have more central adiposity, and meet more of the criteria for metabolic syndrome than those with HS but without NAFLD. They also showed higher serum ALT levels, higher triglycerides, and higher controlled attenuation parameter scores, which is a surrogate marker of liver steatosis.

However, the HS plus NAFLD group had similar rates of active smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular events, compared with those who had HS only. They also showed no differences in hemoglobin A1c, serum insulin, insulin resistance, or liver stiffness, compared with the HS-only group.

When researchers compared the participants with HS plus NAFLD with controls with NAFLD, they found the HS group had significantly higher levels of liver stiffness measurement, which is a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis and severity, but there were no differences in the degree of hepatic steatosis.

The individuals with HS plus NAFLD had significantly lower serum albumin, but significantly higher serum gamma–glutamyl transpeptidase and ferritin, compared with controls who had NAFLD. They were also more likely to have metabolic risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.

The multivariate analysis also showed that male sex was a protective factor, because the prevalence of obesity was higher in women.

After adjusting for classic cardiovascular and steatosis risk factors, the researchers calculated that HS was a significant and independent risk factor for NAFLD, with an odds ratio of 7.75 (P less than .001). The results provide “the first evidence that patients with HS have a significant high prevalence of NAFLD, which is independent of classic metabolic risk factors and, according to our results, probably not related to the severity of the disease,” wrote Carlos Durán-Vian, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, and coauthors.

“We think that our findings might have potential clinical implications, and physicians involved in the care of patients with HS should be aware of the link between this entity and NAFLD, in order to improve the overall management of these patients,” they wrote, noting that HS is often associated with the same metabolic disorders that can promote fatty liver disease, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome. But the discovery that it is an independent risk factor demands other hypotheses to explain the association between the two conditions.

“In this sense, a possible explanation to deeper understanding the link between HS and NAFLD could be the presence of chronic inflammation due to persistent and abnormal secretion of adipokines (i.e. adiponectin, leptin, resistin) and several proinflammatory cytokines,” the authors wrote, pointing out that NAFLD is also common among people with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

The study had the limitation of being an observational, cross-sectional design, and the authors acknowledged that the cohort was relatively small. They also were unable to use liver biopsies to confirm the NAFLD diagnosis.

No funding or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Durán-Vian C et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15764.

independent of other metabolic risk factors, a study has found.

The results of the case-control study of 70 individuals with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and 150 age- and gender-matched controls were published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Using hepatic ultrasonography and transient elastography, the investigators found that 51 (72.9%) the participants with HS also had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), compared with 37 (24.7%) of the controls (P less than .001).

Those with HS and NAFLD were more likely to be obese, have more central adiposity, and meet more of the criteria for metabolic syndrome than those with HS but without NAFLD. They also showed higher serum ALT levels, higher triglycerides, and higher controlled attenuation parameter scores, which is a surrogate marker of liver steatosis.

However, the HS plus NAFLD group had similar rates of active smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular events, compared with those who had HS only. They also showed no differences in hemoglobin A1c, serum insulin, insulin resistance, or liver stiffness, compared with the HS-only group.

When researchers compared the participants with HS plus NAFLD with controls with NAFLD, they found the HS group had significantly higher levels of liver stiffness measurement, which is a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis and severity, but there were no differences in the degree of hepatic steatosis.

The individuals with HS plus NAFLD had significantly lower serum albumin, but significantly higher serum gamma–glutamyl transpeptidase and ferritin, compared with controls who had NAFLD. They were also more likely to have metabolic risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.

The multivariate analysis also showed that male sex was a protective factor, because the prevalence of obesity was higher in women.

After adjusting for classic cardiovascular and steatosis risk factors, the researchers calculated that HS was a significant and independent risk factor for NAFLD, with an odds ratio of 7.75 (P less than .001). The results provide “the first evidence that patients with HS have a significant high prevalence of NAFLD, which is independent of classic metabolic risk factors and, according to our results, probably not related to the severity of the disease,” wrote Carlos Durán-Vian, MD, from the department of dermatology at the University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, and coauthors.

“We think that our findings might have potential clinical implications, and physicians involved in the care of patients with HS should be aware of the link between this entity and NAFLD, in order to improve the overall management of these patients,” they wrote, noting that HS is often associated with the same metabolic disorders that can promote fatty liver disease, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome. But the discovery that it is an independent risk factor demands other hypotheses to explain the association between the two conditions.

“In this sense, a possible explanation to deeper understanding the link between HS and NAFLD could be the presence of chronic inflammation due to persistent and abnormal secretion of adipokines (i.e. adiponectin, leptin, resistin) and several proinflammatory cytokines,” the authors wrote, pointing out that NAFLD is also common among people with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders.

The study had the limitation of being an observational, cross-sectional design, and the authors acknowledged that the cohort was relatively small. They also were unable to use liver biopsies to confirm the NAFLD diagnosis.

No funding or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Durán-Vian C et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jul 1. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15764.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY AND VENEREOLOGY

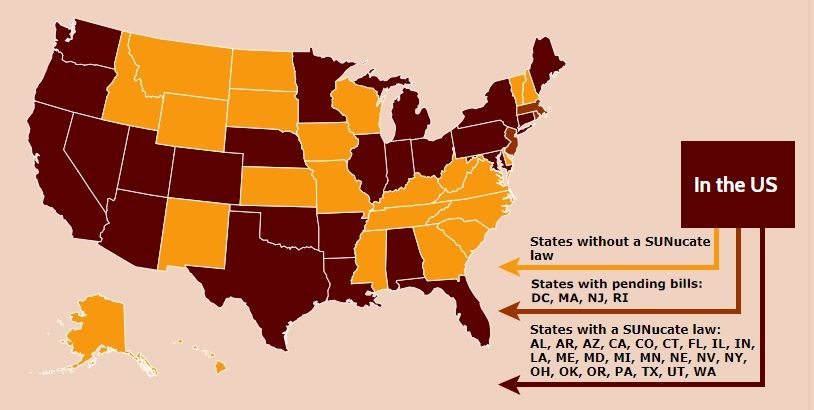

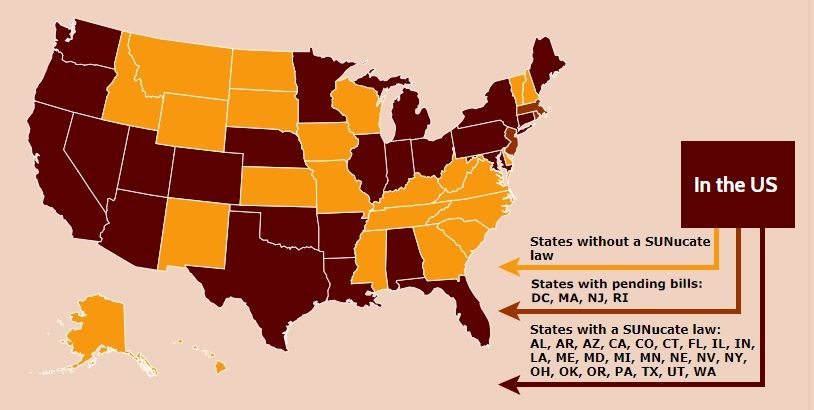

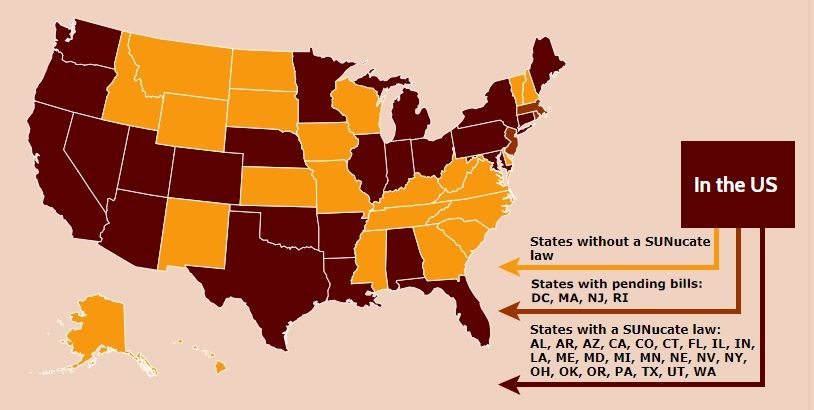

Nebraska issues SUNucate-based guidance for schools

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.