User login

Dark spots in multiple locations

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered whether this was a case of metastatic melanoma based on the appearance of the dark lesions, but thought that 22 years was a long time for a primary cancer to metastasize. After obtaining informed consent, the FP performed a 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the lesions on the patient’s trunk. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The FP sutured the area closed to minimize postoperative bleeding. The pathology report came back as metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, melanoma can return even decades after the primary tumor is excised. The FP referred the patient to a medical oncologist who specialized in melanoma treatment. Unfortunately, the patient passed away within a year of the recurrent melanoma diagnosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Rash with hair loss

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP had never seen a condition like this before, so he used some online resources to come up with a differential diagnosis that included sarcoidosis, leprosy, drug eruption, and mycosis fungoides. Aside from an occasional drug eruption, the other conditions were ones that he had seen in textbooks only.

Based on that differential diagnosis, the FP decided to do a punch biopsy of the largest nodule, which was near the patient’s mouth. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report came back as folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. The FP researched the diagnosis and determined that this was a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that involved hair follicles and tended to occur on the head and neck. This explained the patient’s hair loss in his beard and right eyebrow. While the prognosis for mycosis fungoides is quite good, the same cannot be said for the folliculotropic variant.

The FP referred the patient to Dermatology for further evaluation and treatment. In consultation with Hematology, the patient was treated with a potent topical steroid, chemotherapy, and narrowband ultraviolet B light therapy. His condition improved, but ongoing treatment and surveillance were needed.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Chacon G, Nayar A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1124-1131.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Was Declining Treatment a Bad Idea?

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

A 50-year-old African-American man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of colored stripes in most of his fingernails. These have been present, without change, for most of his adult life.

The patient has been told these changes probably represent fungal infection, but being dubious of that diagnosis, he declined recommended treatment. Nonetheless, he is interested in knowing exactly what is happening to his nails.

He denies personal or family history of skin cancer and of excessive sun exposure. He reports that several maternal family members have similar nail changes.

EXAMINATION

Seven of the patient’s 10 fingernails demonstrate linear brown streaks that uniformly average 1.5 to 2 mm in width. The streaks run the length of the nail, with no involvement of the adjacent cuticle. Some are darker than others.

The patient has type V skin with no evidence of excessive sun damage.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Fortunately, this patient’s problem is benign and likely to remain so. Termed longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM), these changes are seen in nearly all African-Americans older than 50 (although it is not uncommon for the condition to develop in the third decade of life). Other populations with dark skin are also at risk for LM, albeit at far lower rates. In white populations, the incidence is around 0.5% to 1%.

LM is caused by activation and proliferation of melanocytes in the nail matrix; they are focally incorporated into the nail plate as onychocytes that grow out with the nail. Typically 1 to 3 mm in uniform width, the streaks of LM range from tan to dark brown and can be solitary or multiple in a given nail.

As mentioned, LM is entirely benign, with almost no potential for malignant transformation. However, two notes of caution are in order: First, although African-American persons generally have very low risk for melanoma, the malignancy tends to manifest in this population in areas with the least pigment (eg, palms, soles, oral cavities, nail beds—unusual locations for most other racial groups). Second, the prognosis for these types of melanomas is poor; most patients and providers are unaware of them until an advanced stage that typically includes metastasis.

Therefore, in patients with skin of color, new or changing lesions in the nail bed must be evaluated by a knowledgeable dermatology provider, who may choose to biopsy the proximal aspect of the lesion to rule out cancer. Of course, any such lesion in a white person needs to be monitored carefully as well, since linear melanonychia is relatively uncommon in this group. Changes in the width, color, or border should cause concern, as should extension of the darker color onto the adjacent cuticle.

The differential for linear discoloration in nails or nail beds includes foreign body, warts, benign tumors (eg, nevi), glomus tumors (which are usually painful), and of course, fungal, mold, or yeast infections.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Longitudinal (or linear) melanonychia (LM) is quite common in African-Americans, approaching a prevalence of 100% in those older than 50.

- Having multiple LMs in more than one finger is common in this population.

- However, a new or changing subungual lesion bears close monitoring, or even biopsy, by an experienced dermatology provider.

- Although African-Americans rarely develop melanoma, when they do, it’s often in the least pigmented areas (eg, palms, soles, mouth, and nails).

- The prognosis for proven melanoma in African-American patients is poor, making close monitoring a necessity.

Survey finds psoriasis patients seek relief with alternative therapies

Treatment (CAMs), despite limited documentation supporting their efficacy, reported Emily C. Murphy and her associates, in the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

They performed a survey-based statistical analysis to identify specific types of commonly used CAMs, and to explore reasons patients increasingly turn to alternative therapies. The survey was distributed in the National Psoriasis Foundation’s (NPF) October 2018 newsletter to its 100,927 members. Their results were published in a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Of the 6,101 NPF members who opened the newsletter, 324 clicked on the survey link. Of the 219 who completed the survey, almost 70% were women. The majority were white (84.1%), compared with Hispanic (6.2%), Asian (3.1%), and black (2.6%) participants. Most of the survey respondents had a dermatologist diagnosis of psoriasis, as well as access to health insurance to cover any prescribed medicines needed.

Of the 41% of respondents who reported using alternative therapies, usage was especially high among those who considered their psoriasis as severe (50% vs. 33.6% of those with nonsevere disease). Among the respondents, women were more likely than were men to use CAMs (45.6% vs. 26.5%, P = .002).

Only 4% cited access to care as a reason for choosing alternative therapies; the majority said they used CAMs because “traditional medications did not help or had side effects.”

While men were more likely than were women to use vitamins (24% vs. 18.9%, respectively), Dead Sea bath salts (17% vs. 7.8%), and cupping (3% vs. 0.8%), women were more likely to use herbals/botanicals (17% vs. 14%) and yoga (9.6% vs. 2%).

Patients with moderate psoriasis were significantly more likely than were those with mild or severe cases of the disease to recommend CAMs, regardless of insurance status (52.4% vs. 35% among those with mild disease and 40.4% for those with severe disease).

For some of the commonly used treatments, such as vitamins D and B12, there is insufficient evidence documenting their efficacy, although Dead Sea treatments have been shown to have therapeutic effects. And while there is efficacy evidence for indigo naturalis and meditation, these were not mentioned or were not commonly reported by respondents, the authors pointed out.

Although just 43% of patients said they would recommend a CAM to other people with psoriasis, its use remains widespread. For this reason, “educational initiatives that enable physicians to discuss evidence-based CAMs may improve patient satisfaction and outcomes,” observed Ms. Murphy, a research fellow, and her associates.

Previous studies have cited rates of CAM usage among patients with psoriasis as high as 62%, but researchers have failed to examine the reasons motivating usage. Not surprisingly, patients often use but misunderstand the benefits of alternative therapies.

“The onus is on us as physicians to not only ask our patients if they are using nonallopathic therapies for their psoriasis, but also to create an accepting environment that enables further discussion regarding said treatments to ensure patient safety and ultimately good outcomes,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

The authors had no financial sources or conflicts of interest to disclose; there was no funding source.

SOURCE: Murphy E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar 29. pii: S0190-9622(19)30503-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.059.

Treatment (CAMs), despite limited documentation supporting their efficacy, reported Emily C. Murphy and her associates, in the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

They performed a survey-based statistical analysis to identify specific types of commonly used CAMs, and to explore reasons patients increasingly turn to alternative therapies. The survey was distributed in the National Psoriasis Foundation’s (NPF) October 2018 newsletter to its 100,927 members. Their results were published in a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Of the 6,101 NPF members who opened the newsletter, 324 clicked on the survey link. Of the 219 who completed the survey, almost 70% were women. The majority were white (84.1%), compared with Hispanic (6.2%), Asian (3.1%), and black (2.6%) participants. Most of the survey respondents had a dermatologist diagnosis of psoriasis, as well as access to health insurance to cover any prescribed medicines needed.

Of the 41% of respondents who reported using alternative therapies, usage was especially high among those who considered their psoriasis as severe (50% vs. 33.6% of those with nonsevere disease). Among the respondents, women were more likely than were men to use CAMs (45.6% vs. 26.5%, P = .002).

Only 4% cited access to care as a reason for choosing alternative therapies; the majority said they used CAMs because “traditional medications did not help or had side effects.”

While men were more likely than were women to use vitamins (24% vs. 18.9%, respectively), Dead Sea bath salts (17% vs. 7.8%), and cupping (3% vs. 0.8%), women were more likely to use herbals/botanicals (17% vs. 14%) and yoga (9.6% vs. 2%).

Patients with moderate psoriasis were significantly more likely than were those with mild or severe cases of the disease to recommend CAMs, regardless of insurance status (52.4% vs. 35% among those with mild disease and 40.4% for those with severe disease).

For some of the commonly used treatments, such as vitamins D and B12, there is insufficient evidence documenting their efficacy, although Dead Sea treatments have been shown to have therapeutic effects. And while there is efficacy evidence for indigo naturalis and meditation, these were not mentioned or were not commonly reported by respondents, the authors pointed out.

Although just 43% of patients said they would recommend a CAM to other people with psoriasis, its use remains widespread. For this reason, “educational initiatives that enable physicians to discuss evidence-based CAMs may improve patient satisfaction and outcomes,” observed Ms. Murphy, a research fellow, and her associates.

Previous studies have cited rates of CAM usage among patients with psoriasis as high as 62%, but researchers have failed to examine the reasons motivating usage. Not surprisingly, patients often use but misunderstand the benefits of alternative therapies.

“The onus is on us as physicians to not only ask our patients if they are using nonallopathic therapies for their psoriasis, but also to create an accepting environment that enables further discussion regarding said treatments to ensure patient safety and ultimately good outcomes,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

The authors had no financial sources or conflicts of interest to disclose; there was no funding source.

SOURCE: Murphy E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar 29. pii: S0190-9622(19)30503-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.059.

Treatment (CAMs), despite limited documentation supporting their efficacy, reported Emily C. Murphy and her associates, in the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

They performed a survey-based statistical analysis to identify specific types of commonly used CAMs, and to explore reasons patients increasingly turn to alternative therapies. The survey was distributed in the National Psoriasis Foundation’s (NPF) October 2018 newsletter to its 100,927 members. Their results were published in a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Of the 6,101 NPF members who opened the newsletter, 324 clicked on the survey link. Of the 219 who completed the survey, almost 70% were women. The majority were white (84.1%), compared with Hispanic (6.2%), Asian (3.1%), and black (2.6%) participants. Most of the survey respondents had a dermatologist diagnosis of psoriasis, as well as access to health insurance to cover any prescribed medicines needed.

Of the 41% of respondents who reported using alternative therapies, usage was especially high among those who considered their psoriasis as severe (50% vs. 33.6% of those with nonsevere disease). Among the respondents, women were more likely than were men to use CAMs (45.6% vs. 26.5%, P = .002).

Only 4% cited access to care as a reason for choosing alternative therapies; the majority said they used CAMs because “traditional medications did not help or had side effects.”

While men were more likely than were women to use vitamins (24% vs. 18.9%, respectively), Dead Sea bath salts (17% vs. 7.8%), and cupping (3% vs. 0.8%), women were more likely to use herbals/botanicals (17% vs. 14%) and yoga (9.6% vs. 2%).

Patients with moderate psoriasis were significantly more likely than were those with mild or severe cases of the disease to recommend CAMs, regardless of insurance status (52.4% vs. 35% among those with mild disease and 40.4% for those with severe disease).

For some of the commonly used treatments, such as vitamins D and B12, there is insufficient evidence documenting their efficacy, although Dead Sea treatments have been shown to have therapeutic effects. And while there is efficacy evidence for indigo naturalis and meditation, these were not mentioned or were not commonly reported by respondents, the authors pointed out.

Although just 43% of patients said they would recommend a CAM to other people with psoriasis, its use remains widespread. For this reason, “educational initiatives that enable physicians to discuss evidence-based CAMs may improve patient satisfaction and outcomes,” observed Ms. Murphy, a research fellow, and her associates.

Previous studies have cited rates of CAM usage among patients with psoriasis as high as 62%, but researchers have failed to examine the reasons motivating usage. Not surprisingly, patients often use but misunderstand the benefits of alternative therapies.

“The onus is on us as physicians to not only ask our patients if they are using nonallopathic therapies for their psoriasis, but also to create an accepting environment that enables further discussion regarding said treatments to ensure patient safety and ultimately good outcomes,” senior author Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

The authors had no financial sources or conflicts of interest to disclose; there was no funding source.

SOURCE: Murphy E et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Mar 29. pii: S0190-9622(19)30503-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.059.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Ligelizumab maintains urticaria control for up to 1 year

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

WASHINGTON – in an open-label extension study, Diane Baker, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

About 75% of the cohort experienced complete disease control at least once during the study. Novartis is developing ligelizumab (QGE031) as a treatment option for patients with spontaneous chronic urticaria (CSU) whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by H1-antihistamines. Like omalizumab (Xolair), which is approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of CSU, ligelizumab is a humanized anti-IgE monoclonal antibody. But the investigational agent binds to IgE with greater affinity than omalizumab, said Dr. Baker, a dermatologist who practices in Portland, Ore.

The extension study was a follow-up to a 12-week, phase 2, dose-finding trial of 382 CSU patients. In the study, which was not powered for efficacy endpoints, 51% of those who received 72 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks had a Hives Severity Score of 0 by week 12, compared with 42% of those who received 240 mg every 4 weeks and 26% of those taking the omalizumab comparator. Additionally, 47% of those in the 72-mg group and 46% of the 240-mg group achieved a score of 0 on another indicator, the Urticaria Activity Score, which measures symptoms over 7 days (UAS7).

The extension study, which evaluated the 240-mg dose, showed the durability of that response, with 52% of those in the 240-mg group maintained a UAS7 of 0 at 1 year, according to Dr. Baker. By the end of the year, most patients (75.8%) had experienced at least one period of complete symptom control, and 84.0% experienced a UAS of 6 or lower at least once.

Adverse events were common in the cohort, with 84% experiencing at least one. But most (78%) were mild or moderate, and there was no clear side effect pattern, Dr. Baker said. Eight patients discontinued treatment because of an adverse event, and another eight dropped out because of lack of efficacy. Other reasons for discontinuation were pregnancy, protocol deviation, and physician or patient decision.

Novartis has launched two 1-year, phase 3 trials randomizing patients to 72 mg or 240 mg of ligelizumab or 300 mg of omalizumab every 4 weeks in a similar patient population, Dr. Baker said. PEARL 1 and PEARL 2, the largest pivotal trials to date in CSU, will enroll more than 2,000 patients, according to a company press release.

Dr. Baker is a clinical trials investigator for Novartis.

SOURCE: Baker D et al. AAD 2019, Session S034.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

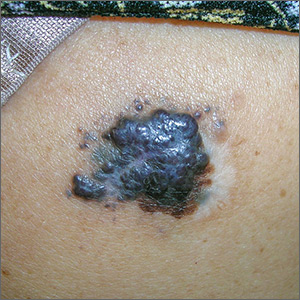

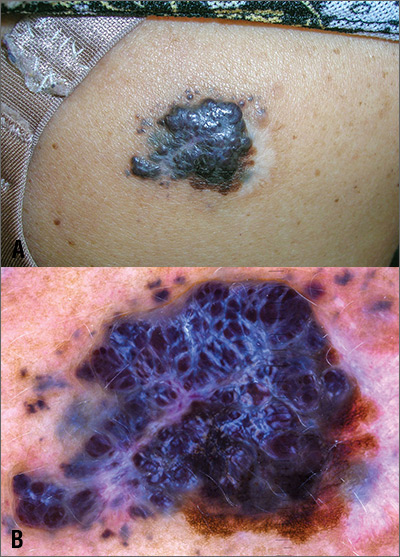

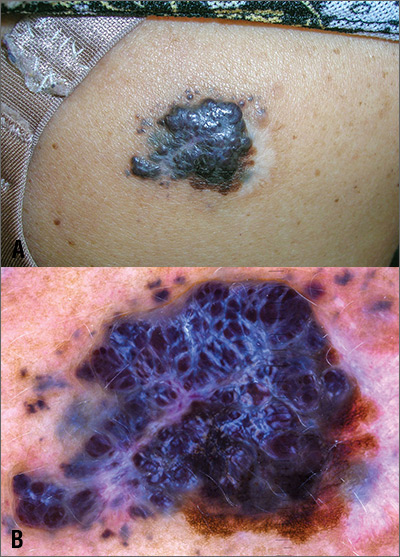

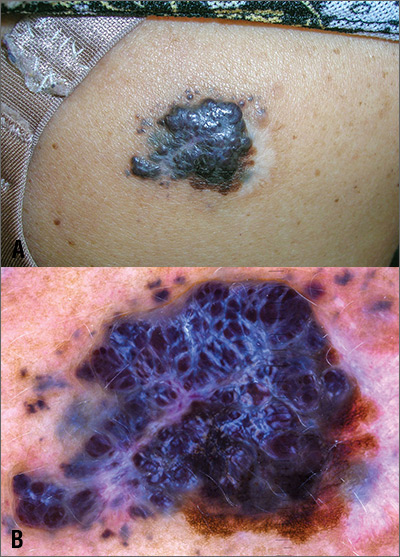

Large mass on shoulder

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP was extremely concerned that this was a large melanoma due the lesion’s chaotic appearance, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the lesion was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was > 6 mm, and it was Enlarging by history.

With his dermatoscope attached to his smart phone, the FP looked at the lesion and took a photograph (Figure B). The image revealed a pigment network of the original nevus at 5:00 to 6:00 o’clock and extensions of the tumor due to in-transit metastases. Satellites were visible, especially in the top right and left corners. The FP noted the shiny white lines caused by collagen deposition found in growing tumors. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”)

The FP knew that the mass needed to be biopsied, but because of its size, the best he could do would be to perform a partial biopsy. So on the day of presentation, the FP performed a 6-mm punch biopsy in the most raised area of the lesion to try and get sufficient depth and breadth for diagnosis and prognosis. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Punch biopsy.”)

The pathology report indicated that the lesion was a nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm. This melanoma arose in a nevus, which occurs in about 30% of melanomas. Most melanomas arise de novo.

The FP referred the patient to a surgical oncologist for an excision with 2 cm margins and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. The sentinel node was in the right axilla and was remarkably negative despite the local in-transit metastases/satellites. One year after the original diagnosis was made, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no new melanomas. The patient follows up with the dermatologist for skin and lymph node surveillance every 3 months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Newborn with desquamating rash

A 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergency department by his mother. The infant had been doing well until his most recent diaper change when his mother noticed a rash around the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus.

The infant was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpartum course, the infant underwent an elective circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval reports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomiting, or changes in urine or stool output.

The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, upon further questioning, the mother noted that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to untreated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

On physical examination, the infant was overall well-appearing and was breastfeeding vigorously without respiratory distress or cyanosis. He was afebrile with normal vital signs. The majority of the physical examination was normal; however, there was erythematous desquamation around the umbilical stump and genitalia with no vesicles noted. The umbilical stump had a small amount of purulent drainage and necrosis centrally. The infant had a 1-cm round, peeling lesion on the left temple (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried serosanguinous drainage and similar superficial peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctuance and only minimal surrounding erythema.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and suspected maternal MRSA infection (with possible transmission to the infant), we diagnosed staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in this patient. SSSS is rare, with annual incidence of 45 cases per million US infants under the age of 2.1 Newborns with a generalized form of SSSS commonly present with fever, poor feeding, irritability, and lethargy. This is followed by a generalized erythematous rash that initially may appear on the head and neck and spread to the rest of the body. Large, fragile blisters subsequently appear. These blisters rupture on gentle pressure, which is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Ultimately, large sheets of skin easily slough off, leaving raw, denuded skin.2

S aureus is not part of normal skin flora, yet it is found on the skin and mucous membranes of 19% to 55% of healthy adults and children.3S aureus can cause a wide range of infections ranging from abscesses to cellulitis; SSSS is caused by hematogenous spread of S aureus exfoliative toxin. Newborns and immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.

Neonatal patients with SSSS most commonly present at 3 to 16 days of age.2 The lack of antitoxin antibody in neonates allows the toxin to reach the epidermis where it acts locally to produce the characteristic fragile skin lesions that often rupture prior to clinical presentation.2,4 During progression of the disease, flaky skin desquamation will occur as the lesions heal.

A retrospective review of 39 cases of SSSS identified pneumonia as the most frequent complication, occurring in 74.4% of the cases.5 The mortality rate of SSSS is up to 5%, and is associated with sepsis, superinfection, electrolyte imbalances, and extensive skin involvement.2,6

If SSSS is suspected, obtain cultures from the blood, urine, eyes, nose, throat, and skin lesions to identify the primary focus of infection.7 However, the retrospective review of 39 cases (noted above) found a positive rate of S aureus isolation of only 23.5%.5 Physicians will often have to make a diagnosis based on clinical presentation and empirically initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics while considering alternative diagnoses.

Continue to: A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

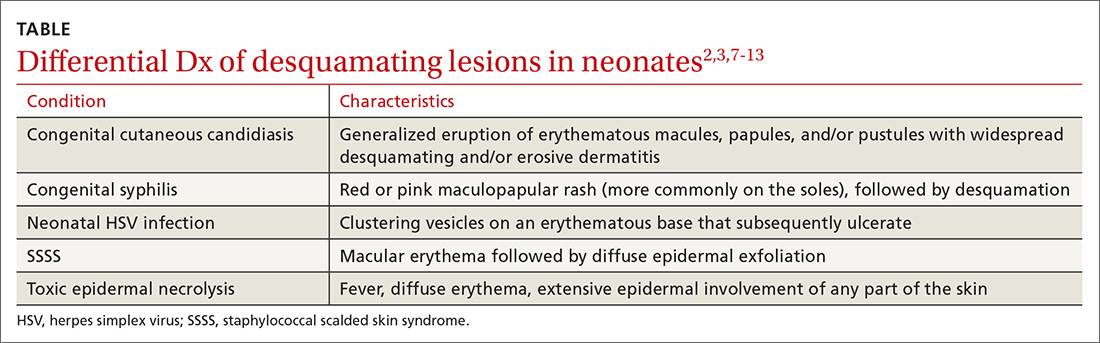

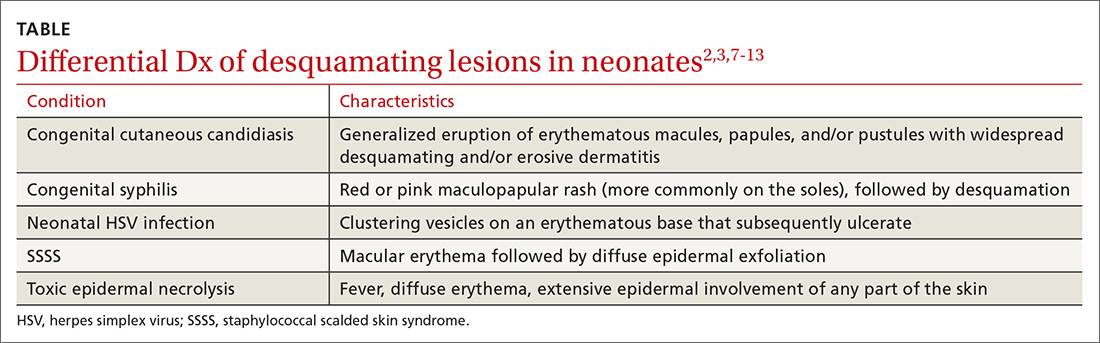

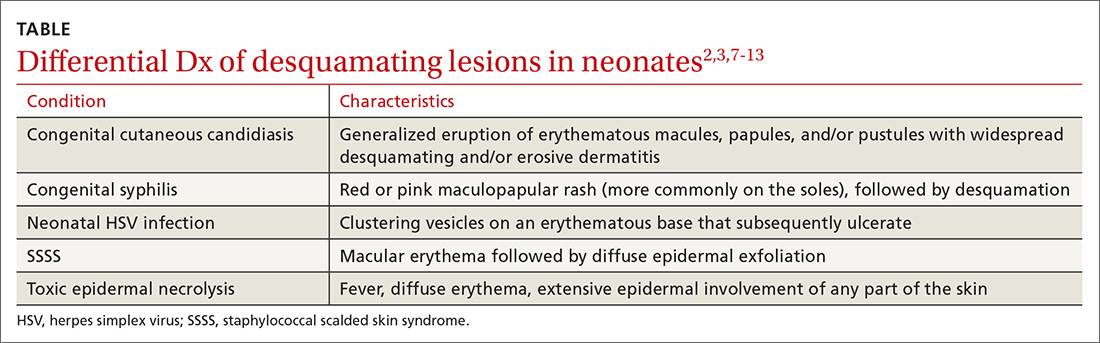

While biopsy rarely is required, it may be helpful to distinguish SSSS from other entities in the differential diagnosis (TABLE2,3,7-13).

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare and life-threatening desquamating disease nearly always caused by a reaction to medications, including antibiotics. TEN can occur at any age. Fever, diffuse erythema, and extensive epidermal involvement (>30% of skin) differentiate TEN from Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which affects less than 10% of the epidermis. It is worth mentioning that TEN and SJS are now considered to be a spectrum of one disease, and an overlap syndrome has been described with 10% to 30% of skin affected.8 Diagnosis is made clinically, although skin biopsy routinely is performed.7,9

Congenital syphilis features a red or pink maculopapular rash followed by desquamation. Lesions are more common on the soles.10 Desquamation or ulcerative skin lesions should be examined for spirochetes.11 A quantitative, nontreponemal test such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) will be positive in most infants if exposed through the placenta, but antibodies will disappear in uninfected infants by 6 months of age.8

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis presents with a generalized eruption of erythematous macules, papules, and/or pustules with widespread desquamating and/or erosive dermatitis. Premature neonates with extremely low birth weight are at higher risk.13 Diagnosis is confirmed on microscopy by the presence of Candida albicans spores in skin scrapings.13

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) symptoms typically appear between 1 and 3 weeks of life, with 60% to 70% of cases presenting with classic clustering vesicles on an erythematous base.14 Diagnosis is made with HSV viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Continue to: SSSS should be considered a pediatrics emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency due to potential complications. Core measures of SSSS treatment include immediate administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. US population studies suggest clindamycin and penicillinase-resistant penicillin as empiric therapy.15 However, local strains and resistance patterns, including the prevalence of MRSA, as well as age, comorbidities, and severity of illness should influence antibiotic selection.

IV nafcillin or oxacillin may be used with pediatric dosing of 150 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). For suspected MRSA, IV vancomycin should be considered, with an infant dose of 40 to 60 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours.16 Fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional management should be addressed immediately. Ongoing fluid losses due to exfoliated skin must be replaced, and skin care to desquamated areas also should be addressed urgently.

Our patient. Phone consultation with an infectious disease specialist at a local children’s hospital resulted in a recommendation to treat for sepsis empirically with IV vancomycin, cefotaxime, and acyclovir. Acyclovir was discontinued once the HSV PCR came back negative. The antibiotic coverage was narrowed to IV ampicillin 50 mg/kg every 8 hours when cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures returned negative at 48 hours, wound culture sensitivity grew MSSA, and the patient’s clinical condition stabilized. Our patient received 10 days of IV antibiotics and was discharged on oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg divided twice daily for a total of 14 days of treatment per recommendations by the infectious disease specialist. Our patient fully recovered without any residual skin findings after completion of the antibiotic course.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer J. Walker, MD, MPH, Hawaii Island Family Health Center at Hilo Medical Center, 1190 Waianuenue Ave, Hilo, HI 96720; [email protected]

1. Staiman A, Hsu D, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in US children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:704-708.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505-520.

4. Ladhani S. Understanding the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:181-189.

5. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:43-47.

6. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39:627-633.

7. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

8. Bastuji-Garin SB, Stern RS, Shear NH, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92.

9. Elias PM, Fritsch P, Epstein EH. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. clinical features, pathogenesis, and recent microbiological and biochemical developments. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:207-219.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin M, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I: common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

11. Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1-21.

12. Arnold SR, Ford-Jones EL. Congenital syphilis: a guide to diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2000;5:463-469.

13. Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG, Miller Z. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;105:438-444.

14. Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:1-13.

15. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

16. Gilbert DN, Chambers HF, Eliopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 48th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc; 2014:56.

A 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergency department by his mother. The infant had been doing well until his most recent diaper change when his mother noticed a rash around the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus.

The infant was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpartum course, the infant underwent an elective circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval reports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomiting, or changes in urine or stool output.

The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, upon further questioning, the mother noted that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to untreated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

On physical examination, the infant was overall well-appearing and was breastfeeding vigorously without respiratory distress or cyanosis. He was afebrile with normal vital signs. The majority of the physical examination was normal; however, there was erythematous desquamation around the umbilical stump and genitalia with no vesicles noted. The umbilical stump had a small amount of purulent drainage and necrosis centrally. The infant had a 1-cm round, peeling lesion on the left temple (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried serosanguinous drainage and similar superficial peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctuance and only minimal surrounding erythema.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and suspected maternal MRSA infection (with possible transmission to the infant), we diagnosed staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in this patient. SSSS is rare, with annual incidence of 45 cases per million US infants under the age of 2.1 Newborns with a generalized form of SSSS commonly present with fever, poor feeding, irritability, and lethargy. This is followed by a generalized erythematous rash that initially may appear on the head and neck and spread to the rest of the body. Large, fragile blisters subsequently appear. These blisters rupture on gentle pressure, which is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Ultimately, large sheets of skin easily slough off, leaving raw, denuded skin.2

S aureus is not part of normal skin flora, yet it is found on the skin and mucous membranes of 19% to 55% of healthy adults and children.3S aureus can cause a wide range of infections ranging from abscesses to cellulitis; SSSS is caused by hematogenous spread of S aureus exfoliative toxin. Newborns and immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.

Neonatal patients with SSSS most commonly present at 3 to 16 days of age.2 The lack of antitoxin antibody in neonates allows the toxin to reach the epidermis where it acts locally to produce the characteristic fragile skin lesions that often rupture prior to clinical presentation.2,4 During progression of the disease, flaky skin desquamation will occur as the lesions heal.

A retrospective review of 39 cases of SSSS identified pneumonia as the most frequent complication, occurring in 74.4% of the cases.5 The mortality rate of SSSS is up to 5%, and is associated with sepsis, superinfection, electrolyte imbalances, and extensive skin involvement.2,6

If SSSS is suspected, obtain cultures from the blood, urine, eyes, nose, throat, and skin lesions to identify the primary focus of infection.7 However, the retrospective review of 39 cases (noted above) found a positive rate of S aureus isolation of only 23.5%.5 Physicians will often have to make a diagnosis based on clinical presentation and empirically initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics while considering alternative diagnoses.

Continue to: A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

While biopsy rarely is required, it may be helpful to distinguish SSSS from other entities in the differential diagnosis (TABLE2,3,7-13).

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare and life-threatening desquamating disease nearly always caused by a reaction to medications, including antibiotics. TEN can occur at any age. Fever, diffuse erythema, and extensive epidermal involvement (>30% of skin) differentiate TEN from Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which affects less than 10% of the epidermis. It is worth mentioning that TEN and SJS are now considered to be a spectrum of one disease, and an overlap syndrome has been described with 10% to 30% of skin affected.8 Diagnosis is made clinically, although skin biopsy routinely is performed.7,9

Congenital syphilis features a red or pink maculopapular rash followed by desquamation. Lesions are more common on the soles.10 Desquamation or ulcerative skin lesions should be examined for spirochetes.11 A quantitative, nontreponemal test such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) will be positive in most infants if exposed through the placenta, but antibodies will disappear in uninfected infants by 6 months of age.8

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis presents with a generalized eruption of erythematous macules, papules, and/or pustules with widespread desquamating and/or erosive dermatitis. Premature neonates with extremely low birth weight are at higher risk.13 Diagnosis is confirmed on microscopy by the presence of Candida albicans spores in skin scrapings.13

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) symptoms typically appear between 1 and 3 weeks of life, with 60% to 70% of cases presenting with classic clustering vesicles on an erythematous base.14 Diagnosis is made with HSV viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Continue to: SSSS should be considered a pediatrics emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency due to potential complications. Core measures of SSSS treatment include immediate administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. US population studies suggest clindamycin and penicillinase-resistant penicillin as empiric therapy.15 However, local strains and resistance patterns, including the prevalence of MRSA, as well as age, comorbidities, and severity of illness should influence antibiotic selection.

IV nafcillin or oxacillin may be used with pediatric dosing of 150 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). For suspected MRSA, IV vancomycin should be considered, with an infant dose of 40 to 60 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours.16 Fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional management should be addressed immediately. Ongoing fluid losses due to exfoliated skin must be replaced, and skin care to desquamated areas also should be addressed urgently.

Our patient. Phone consultation with an infectious disease specialist at a local children’s hospital resulted in a recommendation to treat for sepsis empirically with IV vancomycin, cefotaxime, and acyclovir. Acyclovir was discontinued once the HSV PCR came back negative. The antibiotic coverage was narrowed to IV ampicillin 50 mg/kg every 8 hours when cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures returned negative at 48 hours, wound culture sensitivity grew MSSA, and the patient’s clinical condition stabilized. Our patient received 10 days of IV antibiotics and was discharged on oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg divided twice daily for a total of 14 days of treatment per recommendations by the infectious disease specialist. Our patient fully recovered without any residual skin findings after completion of the antibiotic course.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer J. Walker, MD, MPH, Hawaii Island Family Health Center at Hilo Medical Center, 1190 Waianuenue Ave, Hilo, HI 96720; [email protected]

A 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergency department by his mother. The infant had been doing well until his most recent diaper change when his mother noticed a rash around the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus.

The infant was born at term via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpartum course, the infant underwent an elective circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval reports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomiting, or changes in urine or stool output.

The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, upon further questioning, the mother noted that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to untreated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

On physical examination, the infant was overall well-appearing and was breastfeeding vigorously without respiratory distress or cyanosis. He was afebrile with normal vital signs. The majority of the physical examination was normal; however, there was erythematous desquamation around the umbilical stump and genitalia with no vesicles noted. The umbilical stump had a small amount of purulent drainage and necrosis centrally. The infant had a 1-cm round, peeling lesion on the left temple (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried serosanguinous drainage and similar superficial peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctuance and only minimal surrounding erythema.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Based on the age of the patient, clinical presentation, and suspected maternal MRSA infection (with possible transmission to the infant), we diagnosed staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in this patient. SSSS is rare, with annual incidence of 45 cases per million US infants under the age of 2.1 Newborns with a generalized form of SSSS commonly present with fever, poor feeding, irritability, and lethargy. This is followed by a generalized erythematous rash that initially may appear on the head and neck and spread to the rest of the body. Large, fragile blisters subsequently appear. These blisters rupture on gentle pressure, which is known as a positive Nikolsky sign. Ultimately, large sheets of skin easily slough off, leaving raw, denuded skin.2

S aureus is not part of normal skin flora, yet it is found on the skin and mucous membranes of 19% to 55% of healthy adults and children.3S aureus can cause a wide range of infections ranging from abscesses to cellulitis; SSSS is caused by hematogenous spread of S aureus exfoliative toxin. Newborns and immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible.

Neonatal patients with SSSS most commonly present at 3 to 16 days of age.2 The lack of antitoxin antibody in neonates allows the toxin to reach the epidermis where it acts locally to produce the characteristic fragile skin lesions that often rupture prior to clinical presentation.2,4 During progression of the disease, flaky skin desquamation will occur as the lesions heal.

A retrospective review of 39 cases of SSSS identified pneumonia as the most frequent complication, occurring in 74.4% of the cases.5 The mortality rate of SSSS is up to 5%, and is associated with sepsis, superinfection, electrolyte imbalances, and extensive skin involvement.2,6

If SSSS is suspected, obtain cultures from the blood, urine, eyes, nose, throat, and skin lesions to identify the primary focus of infection.7 However, the retrospective review of 39 cases (noted above) found a positive rate of S aureus isolation of only 23.5%.5 Physicians will often have to make a diagnosis based on clinical presentation and empirically initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics while considering alternative diagnoses.

Continue to: A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

A clinical diagnosis with a large differential

While biopsy rarely is required, it may be helpful to distinguish SSSS from other entities in the differential diagnosis (TABLE2,3,7-13).

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare and life-threatening desquamating disease nearly always caused by a reaction to medications, including antibiotics. TEN can occur at any age. Fever, diffuse erythema, and extensive epidermal involvement (>30% of skin) differentiate TEN from Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which affects less than 10% of the epidermis. It is worth mentioning that TEN and SJS are now considered to be a spectrum of one disease, and an overlap syndrome has been described with 10% to 30% of skin affected.8 Diagnosis is made clinically, although skin biopsy routinely is performed.7,9

Congenital syphilis features a red or pink maculopapular rash followed by desquamation. Lesions are more common on the soles.10 Desquamation or ulcerative skin lesions should be examined for spirochetes.11 A quantitative, nontreponemal test such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) will be positive in most infants if exposed through the placenta, but antibodies will disappear in uninfected infants by 6 months of age.8

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis presents with a generalized eruption of erythematous macules, papules, and/or pustules with widespread desquamating and/or erosive dermatitis. Premature neonates with extremely low birth weight are at higher risk.13 Diagnosis is confirmed on microscopy by the presence of Candida albicans spores in skin scrapings.13

Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) symptoms typically appear between 1 and 3 weeks of life, with 60% to 70% of cases presenting with classic clustering vesicles on an erythematous base.14 Diagnosis is made with HSV viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Continue to: SSSS should be considered a pediatrics emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency

SSSS should be considered a pediatric emergency due to potential complications. Core measures of SSSS treatment include immediate administration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. US population studies suggest clindamycin and penicillinase-resistant penicillin as empiric therapy.15 However, local strains and resistance patterns, including the prevalence of MRSA, as well as age, comorbidities, and severity of illness should influence antibiotic selection.

IV nafcillin or oxacillin may be used with pediatric dosing of 150 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). For suspected MRSA, IV vancomycin should be considered, with an infant dose of 40 to 60 mg/kg daily divided every 6 hours.16 Fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional management should be addressed immediately. Ongoing fluid losses due to exfoliated skin must be replaced, and skin care to desquamated areas also should be addressed urgently.

Our patient. Phone consultation with an infectious disease specialist at a local children’s hospital resulted in a recommendation to treat for sepsis empirically with IV vancomycin, cefotaxime, and acyclovir. Acyclovir was discontinued once the HSV PCR came back negative. The antibiotic coverage was narrowed to IV ampicillin 50 mg/kg every 8 hours when cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures returned negative at 48 hours, wound culture sensitivity grew MSSA, and the patient’s clinical condition stabilized. Our patient received 10 days of IV antibiotics and was discharged on oral amoxicillin 50 mg/kg divided twice daily for a total of 14 days of treatment per recommendations by the infectious disease specialist. Our patient fully recovered without any residual skin findings after completion of the antibiotic course.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer J. Walker, MD, MPH, Hawaii Island Family Health Center at Hilo Medical Center, 1190 Waianuenue Ave, Hilo, HI 96720; [email protected]

1. Staiman A, Hsu D, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in US children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:704-708.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505-520.

4. Ladhani S. Understanding the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:181-189.

5. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:43-47.

6. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39:627-633.

7. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

8. Bastuji-Garin SB, Stern RS, Shear NH, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92.

9. Elias PM, Fritsch P, Epstein EH. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. clinical features, pathogenesis, and recent microbiological and biochemical developments. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:207-219.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin M, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I: common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

11. Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1-21.

12. Arnold SR, Ford-Jones EL. Congenital syphilis: a guide to diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2000;5:463-469.

13. Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG, Miller Z. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;105:438-444.

14. Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:1-13.

15. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

16. Gilbert DN, Chambers HF, Eliopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 48th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc; 2014:56.

1. Staiman A, Hsu D, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in US children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:704-708.

2. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, et al. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224-242.

3. Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:505-520.

4. Ladhani S. Understanding the mechanism of action of the exfoliative toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:181-189.

5. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, et al. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:43-47.

6. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39:627-633.

7. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

8. Bastuji-Garin SB, Stern RS, Shear NH, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92.

9. Elias PM, Fritsch P, Epstein EH. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. clinical features, pathogenesis, and recent microbiological and biochemical developments. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:207-219.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin M, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I: common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:47-52.

11. Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1-21.

12. Arnold SR, Ford-Jones EL. Congenital syphilis: a guide to diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2000;5:463-469.

13. Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG, Miller Z. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;105:438-444.

14. Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:1-13.

15. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:305-308.

16. Gilbert DN, Chambers HF, Eliopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 48th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc; 2014:56.

Food allergy can be revealed in the epidermis of children with atopic dermatitis

according to a study of children with and without AD and FA.

The researchers included 62 children aged 4-17 years, who were divided into three groups: atopic dermatitis and food allergy (AD FA+, n = 21), atopic dermatitis and no food allergy (AD FA−, n = 19), and nonatopic controls (NA, n = 22).

“In this prospective clinical study with laboratory personnel blinded to minimize bias, we demonstrate that children with AD FA+ represent a unique endotype that can be distinguished from AD FA− or NA,” wrote Donald Y. M. Leung, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and his coauthors. Their work was published online in Science Translational Medicine.

According to three different scoring systems, the two AD groups were measured to have similar skin disease severity. Dr. Leung and colleagues then used skin tape stripping to measure the first layer of skin tissue for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and stratum corneum (SC) composition, along with other variables that would indicate a difference between AD FA+ and the other groups.

Upon analysis, children in the AD FA+ group were found to have “a constellation of SC attributes,” including increased TEWL and lower levels of filaggrin gene breakdown products (urocanic acid and pyroglutamic acid) at nonlesional layers. In addition, there was an increase of Staphylococcus aureus on the nonlesional skin of AD FA+, compared with NA.