User login

Rhymin’ pediatric dermatologist provides Demodex tips

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Pediatric dermatologist Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, has composed a whimsical couplet to help physicians broaden their differential diagnosis for acneiform rashes in children.

Pustules on noses: Think demodicosis!

The classic teaching has been that Demodex carriage and its pathologic clinical expression, demodicosis, are rare in children. Not so, Dr. Zaenglein asserted at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“One of the things that we never used to see in kids but now I see all the time, probably because I’m looking for it, is Demodex. You’re not born with Demodex. Your carriage rate will increase over the years and by the time you’re elderly, 95% of us will have it – but not me. I just decided I’m not having these. I’m not looking for them, and I don’t want to know if they’re there,” she quipped, referring to the creepiness factor surrounding these facial parasitic mites invisible to the naked eye.

The mites live in pilosebaceous units. In animals, the disease is called mange. In humans, demodicosis is caused by two species of mites: Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis. The diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of mineral oil skin scrapings.

Primary demodicosis can take the form of pityriasis folliculorum, also known as spinulate demodicosis, papulopustular perioral, periauricular, or periorbital demodicosis, or a nodulocystic/conglobate version.

More commonly, however, .

“Demodicosis can be associated with immunosuppression. Kids with Langerhans cell histiocytosis seem to be prone to it. But you can see it in kids who don’t have any underlying immunosuppression, and I think there are more and more cases of that as we go looking for it,” said Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Penn State University, Hershey, and immediate past president of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

Look for Demodex in children with somewhat atypical versions of common acneiform eruptions: for example, the ‘pustules on noses’ variant.

“Finding Demodex can alter your treatment and make it easier in these cases,” she said.

Metronidazole and ivermectin are the systemic treatment options for pediatric demodicosis.

“I tend to use topical permethrin, just because it’s easy to get. I’ll treat them once a week for 3 weeks in a row. But also make sure to treat the underlying primary inflammatory disorder,” the pediatric dermatologist advised.

Other topical options include ivermectin cream, crotamiton cream, metronidazole gel, and salicylic acid cream.

Dr. Zaenglein reported having financial relationships with Sun Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ortho Dermatologics.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

FDA: Safety signal emerged with higher dose of tofacitinib in RA study

the Food and Drug Administration reported.

The trial’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board identified the signal in patients taking a 10-mg dose of tofacitinib twice daily, the FDA said in a safety announcement.

Pfizer, the trial’s sponsor, took “immediate action” to transition patients in the ongoing trial from the 10-mg, twice-daily dose to 5 mg twice daily, which is the approved dose for adult patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, the agency said. The 10-mg, twice-daily dose is approved only in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis. Xeljanz is also approved to treat psoriatic arthritis. The 11-mg, once-daily dose of Xeljanz XR that is approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis was not tested in the trial.

The ongoing study was designed to assess risks of cardiovascular events, cancer, and opportunistic infections with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily or 5 mg twice daily versus the risks in a control group treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, according to the statement.

Patients had to be 50 years of age or older and have at least one cardiovascular risk factor to be eligible for the study, which was required by the agency in 2012 when it approved tofacitinib, the statement says.

The FDA is reviewing trial data and working with Pfizer to better understand the safety signal, its effect on patients, and how tofacitinib should be used, Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release. The trial will continue and is expected to be completed by the end of 2019.

“The agency will take appropriate action, as warranted, to ensure patients enrolled in this and other trials are protected and that health care professionals and clinical trial researchers understand the risks associated with this use,” she added.

Health care professionals should follow tofacitinib prescribing information, monitor patients for the signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism, and advise patients to seek medical attention immediately if they experience those signs and symptoms, according to the statement.

“We are communicating now, given the serious nature of the safety issue, to ensure that patients taking tofacitinib are aware that the FDA still believes the benefits of taking tofacitinib for its approved uses continue to outweigh the risks,” Dr. Woodcock said in the release.

While not approved in rheumatoid arthritis, the 10-mg, twice-daily dose of tofacitinib is approved in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis, the release says.

the Food and Drug Administration reported.

The trial’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board identified the signal in patients taking a 10-mg dose of tofacitinib twice daily, the FDA said in a safety announcement.

Pfizer, the trial’s sponsor, took “immediate action” to transition patients in the ongoing trial from the 10-mg, twice-daily dose to 5 mg twice daily, which is the approved dose for adult patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, the agency said. The 10-mg, twice-daily dose is approved only in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis. Xeljanz is also approved to treat psoriatic arthritis. The 11-mg, once-daily dose of Xeljanz XR that is approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis was not tested in the trial.

The ongoing study was designed to assess risks of cardiovascular events, cancer, and opportunistic infections with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily or 5 mg twice daily versus the risks in a control group treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, according to the statement.

Patients had to be 50 years of age or older and have at least one cardiovascular risk factor to be eligible for the study, which was required by the agency in 2012 when it approved tofacitinib, the statement says.

The FDA is reviewing trial data and working with Pfizer to better understand the safety signal, its effect on patients, and how tofacitinib should be used, Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release. The trial will continue and is expected to be completed by the end of 2019.

“The agency will take appropriate action, as warranted, to ensure patients enrolled in this and other trials are protected and that health care professionals and clinical trial researchers understand the risks associated with this use,” she added.

Health care professionals should follow tofacitinib prescribing information, monitor patients for the signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism, and advise patients to seek medical attention immediately if they experience those signs and symptoms, according to the statement.

“We are communicating now, given the serious nature of the safety issue, to ensure that patients taking tofacitinib are aware that the FDA still believes the benefits of taking tofacitinib for its approved uses continue to outweigh the risks,” Dr. Woodcock said in the release.

While not approved in rheumatoid arthritis, the 10-mg, twice-daily dose of tofacitinib is approved in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis, the release says.

the Food and Drug Administration reported.

The trial’s Data Safety and Monitoring Board identified the signal in patients taking a 10-mg dose of tofacitinib twice daily, the FDA said in a safety announcement.

Pfizer, the trial’s sponsor, took “immediate action” to transition patients in the ongoing trial from the 10-mg, twice-daily dose to 5 mg twice daily, which is the approved dose for adult patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, the agency said. The 10-mg, twice-daily dose is approved only in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis. Xeljanz is also approved to treat psoriatic arthritis. The 11-mg, once-daily dose of Xeljanz XR that is approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis was not tested in the trial.

The ongoing study was designed to assess risks of cardiovascular events, cancer, and opportunistic infections with tofacitinib 10 mg twice daily or 5 mg twice daily versus the risks in a control group treated with a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, according to the statement.

Patients had to be 50 years of age or older and have at least one cardiovascular risk factor to be eligible for the study, which was required by the agency in 2012 when it approved tofacitinib, the statement says.

The FDA is reviewing trial data and working with Pfizer to better understand the safety signal, its effect on patients, and how tofacitinib should be used, Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a news release. The trial will continue and is expected to be completed by the end of 2019.

“The agency will take appropriate action, as warranted, to ensure patients enrolled in this and other trials are protected and that health care professionals and clinical trial researchers understand the risks associated with this use,” she added.

Health care professionals should follow tofacitinib prescribing information, monitor patients for the signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism, and advise patients to seek medical attention immediately if they experience those signs and symptoms, according to the statement.

“We are communicating now, given the serious nature of the safety issue, to ensure that patients taking tofacitinib are aware that the FDA still believes the benefits of taking tofacitinib for its approved uses continue to outweigh the risks,” Dr. Woodcock said in the release.

While not approved in rheumatoid arthritis, the 10-mg, twice-daily dose of tofacitinib is approved in the dosing regimen for patients with ulcerative colitis, the release says.

FDA: More safety data needed for 12 sunscreen active ingredients

including some of those frequently used in over-the-counter products.

The ingredients requiring additional investigation are cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, sulisobenzone, oxybenzone, and avobenzone. The FDA actions were announced during a press briefing Feb. 21 held to discuss the proposed rule to update regulatory requirements for most sunscreen products marketed in the United States.

There are no urgent safety matters associated with these ingredients. The rule is part of FDA’s charge to construct an over-the-counter (OTC) monograph detailing all available data on sunscreen ingredients, as required by the Sunscreen Innovation Act.

OTC monographs establish conditions under which ingredients may be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) “and not misbranded,” according to the FDA. The proposed rule classifies active ingredients and other conditions as Category I (proposed to be GRASE and not misbranded), Category II (proposed to be not GRASE or to be misbranded), or Category III (additional data needed).

“We are proposing that these ingredients require additional data before a positive GRASE determination can be made,” FDA press officer Sandy Walsh said in an interview, referring to the 12 ingredients. “This proposed rule does not represent a conclusion by the FDA that the sunscreen active ingredients proposed as having insufficient data are unsafe for use in sunscreens. Rather, we are requesting additional information on these ingredients so that we can evaluate their GRASE status in light of changed conditions, including substantially increased sunscreen usage and evolving information about the potential risks associated with these products since they were originally evaluated.”

Among its provisions, the proposal addresses sunscreen active-ingredient safety, dosage forms, and sun protection factor (SPF) and broad-spectrum requirements. It also proposes updates to how products are labeled to make it easier for consumers to identify key product information

Thus far, the agency says that only two active ingredients – titanium dioxide and zinc oxide – can be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are GRASE.

However, two other ingredients – PABA and trolamine salicylate – are not GRASE for use in sunscreens because of safety issues, Theresa Michele, MD, director of the Division of Nonprescription Drug Products Division of Nonprescription Drug Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Products that combine sunscreen and insect repellent also not fit the criteria, she said

“There are 12 ingredients for which there are insufficient safety data to make a positive GRASE determination at this time. To address these 12 ingredients, the FDA is asking industry and other interested parties for additional data. The FDA is working closely with industry and has published several guidances to make sure companies understand what data the agency believes is necessary for the FDA to evaluate safety and effectiveness for sunscreen active ingredients, including the 12 ingredients for which the FDA is seeking more data,” she said.

In addition to seeking these additional data, the rule also proposes the following:

- Dosage forms that are GRASE for use as sunscreens should include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. While powders are proposed to be eligible for inclusion in the monograph, more data are being requested before powders are included. “Wipes, towelettes, body washes, shampoos, and other dosage forms are proposed to be categorized as new drugs because the FDA has not received data showing they are eligible for inclusion in the monograph,” according to the FDA statement outlining the proposed regulation.

- The maximum proposed SPF value on sunscreen labels should be raised from SPF 50 or higher to SPF 60 or higher. “There are not enough data to suggest that consumers get any extra benefit from products with an SPF of more than 60,” Dr. Michele said.

- Sunscreens with an SPF value of 15 or higher should be required to also provide broad-spectrum protection, and for broad-spectrum products, as SPF increases, the magnitude of protection against UVA radiation should also increase. “These proposals are designed to ensure that these products provide consumers with the protections that they expect,” the statement said.

- New sunscreen product labels should be required to make it easier for consumers to identify important information, “including the addition of the active ingredients on the front of the package to bring sunscreen in line with other OTC drugs; a notification on the front label for consumers to read the skin cancer/skin aging alert for sunscreens that have not been shown to help prevent skin cancer; and revised formats for SPF, broad spectrum, and water resistance statements,” the statement said.

- Products that combine sunscreens with insect repellents are not GRASE.

In the meantime, though, consumers should continue to use sunscreens regularly as part of a comprehensive sun protection program, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said during the briefing. “Broad spectrum sunscreens with SPF values of at least 15 are critical to the arsenal of tools for preventing skin cancer and protecting the skin from damage caused by the sun’s rays,” he continued. “Given the recognized public health benefits of sunscreen use, Americans should continue to use sunscreens in conjunction with other sun protective measures (such as protective clothing) as this important rule-making effort moves forward.”

To submit comments on this proposed rule, go to https://www.regulations.gov and follow instructions for submitting comments.

including some of those frequently used in over-the-counter products.

The ingredients requiring additional investigation are cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, sulisobenzone, oxybenzone, and avobenzone. The FDA actions were announced during a press briefing Feb. 21 held to discuss the proposed rule to update regulatory requirements for most sunscreen products marketed in the United States.

There are no urgent safety matters associated with these ingredients. The rule is part of FDA’s charge to construct an over-the-counter (OTC) monograph detailing all available data on sunscreen ingredients, as required by the Sunscreen Innovation Act.

OTC monographs establish conditions under which ingredients may be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) “and not misbranded,” according to the FDA. The proposed rule classifies active ingredients and other conditions as Category I (proposed to be GRASE and not misbranded), Category II (proposed to be not GRASE or to be misbranded), or Category III (additional data needed).

“We are proposing that these ingredients require additional data before a positive GRASE determination can be made,” FDA press officer Sandy Walsh said in an interview, referring to the 12 ingredients. “This proposed rule does not represent a conclusion by the FDA that the sunscreen active ingredients proposed as having insufficient data are unsafe for use in sunscreens. Rather, we are requesting additional information on these ingredients so that we can evaluate their GRASE status in light of changed conditions, including substantially increased sunscreen usage and evolving information about the potential risks associated with these products since they were originally evaluated.”

Among its provisions, the proposal addresses sunscreen active-ingredient safety, dosage forms, and sun protection factor (SPF) and broad-spectrum requirements. It also proposes updates to how products are labeled to make it easier for consumers to identify key product information

Thus far, the agency says that only two active ingredients – titanium dioxide and zinc oxide – can be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are GRASE.

However, two other ingredients – PABA and trolamine salicylate – are not GRASE for use in sunscreens because of safety issues, Theresa Michele, MD, director of the Division of Nonprescription Drug Products Division of Nonprescription Drug Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Products that combine sunscreen and insect repellent also not fit the criteria, she said

“There are 12 ingredients for which there are insufficient safety data to make a positive GRASE determination at this time. To address these 12 ingredients, the FDA is asking industry and other interested parties for additional data. The FDA is working closely with industry and has published several guidances to make sure companies understand what data the agency believes is necessary for the FDA to evaluate safety and effectiveness for sunscreen active ingredients, including the 12 ingredients for which the FDA is seeking more data,” she said.

In addition to seeking these additional data, the rule also proposes the following:

- Dosage forms that are GRASE for use as sunscreens should include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. While powders are proposed to be eligible for inclusion in the monograph, more data are being requested before powders are included. “Wipes, towelettes, body washes, shampoos, and other dosage forms are proposed to be categorized as new drugs because the FDA has not received data showing they are eligible for inclusion in the monograph,” according to the FDA statement outlining the proposed regulation.

- The maximum proposed SPF value on sunscreen labels should be raised from SPF 50 or higher to SPF 60 or higher. “There are not enough data to suggest that consumers get any extra benefit from products with an SPF of more than 60,” Dr. Michele said.

- Sunscreens with an SPF value of 15 or higher should be required to also provide broad-spectrum protection, and for broad-spectrum products, as SPF increases, the magnitude of protection against UVA radiation should also increase. “These proposals are designed to ensure that these products provide consumers with the protections that they expect,” the statement said.

- New sunscreen product labels should be required to make it easier for consumers to identify important information, “including the addition of the active ingredients on the front of the package to bring sunscreen in line with other OTC drugs; a notification on the front label for consumers to read the skin cancer/skin aging alert for sunscreens that have not been shown to help prevent skin cancer; and revised formats for SPF, broad spectrum, and water resistance statements,” the statement said.

- Products that combine sunscreens with insect repellents are not GRASE.

In the meantime, though, consumers should continue to use sunscreens regularly as part of a comprehensive sun protection program, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said during the briefing. “Broad spectrum sunscreens with SPF values of at least 15 are critical to the arsenal of tools for preventing skin cancer and protecting the skin from damage caused by the sun’s rays,” he continued. “Given the recognized public health benefits of sunscreen use, Americans should continue to use sunscreens in conjunction with other sun protective measures (such as protective clothing) as this important rule-making effort moves forward.”

To submit comments on this proposed rule, go to https://www.regulations.gov and follow instructions for submitting comments.

including some of those frequently used in over-the-counter products.

The ingredients requiring additional investigation are cinoxate, dioxybenzone, ensulizole, homosalate, meradimate, octinoxate, octisalate, octocrylene, padimate O, sulisobenzone, oxybenzone, and avobenzone. The FDA actions were announced during a press briefing Feb. 21 held to discuss the proposed rule to update regulatory requirements for most sunscreen products marketed in the United States.

There are no urgent safety matters associated with these ingredients. The rule is part of FDA’s charge to construct an over-the-counter (OTC) monograph detailing all available data on sunscreen ingredients, as required by the Sunscreen Innovation Act.

OTC monographs establish conditions under which ingredients may be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) “and not misbranded,” according to the FDA. The proposed rule classifies active ingredients and other conditions as Category I (proposed to be GRASE and not misbranded), Category II (proposed to be not GRASE or to be misbranded), or Category III (additional data needed).

“We are proposing that these ingredients require additional data before a positive GRASE determination can be made,” FDA press officer Sandy Walsh said in an interview, referring to the 12 ingredients. “This proposed rule does not represent a conclusion by the FDA that the sunscreen active ingredients proposed as having insufficient data are unsafe for use in sunscreens. Rather, we are requesting additional information on these ingredients so that we can evaluate their GRASE status in light of changed conditions, including substantially increased sunscreen usage and evolving information about the potential risks associated with these products since they were originally evaluated.”

Among its provisions, the proposal addresses sunscreen active-ingredient safety, dosage forms, and sun protection factor (SPF) and broad-spectrum requirements. It also proposes updates to how products are labeled to make it easier for consumers to identify key product information

Thus far, the agency says that only two active ingredients – titanium dioxide and zinc oxide – can be marketed without approved new drug applications because they are GRASE.

However, two other ingredients – PABA and trolamine salicylate – are not GRASE for use in sunscreens because of safety issues, Theresa Michele, MD, director of the Division of Nonprescription Drug Products Division of Nonprescription Drug Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Products that combine sunscreen and insect repellent also not fit the criteria, she said

“There are 12 ingredients for which there are insufficient safety data to make a positive GRASE determination at this time. To address these 12 ingredients, the FDA is asking industry and other interested parties for additional data. The FDA is working closely with industry and has published several guidances to make sure companies understand what data the agency believes is necessary for the FDA to evaluate safety and effectiveness for sunscreen active ingredients, including the 12 ingredients for which the FDA is seeking more data,” she said.

In addition to seeking these additional data, the rule also proposes the following:

- Dosage forms that are GRASE for use as sunscreens should include sprays, oils, lotions, creams, gels, butters, pastes, ointments, and sticks. While powders are proposed to be eligible for inclusion in the monograph, more data are being requested before powders are included. “Wipes, towelettes, body washes, shampoos, and other dosage forms are proposed to be categorized as new drugs because the FDA has not received data showing they are eligible for inclusion in the monograph,” according to the FDA statement outlining the proposed regulation.

- The maximum proposed SPF value on sunscreen labels should be raised from SPF 50 or higher to SPF 60 or higher. “There are not enough data to suggest that consumers get any extra benefit from products with an SPF of more than 60,” Dr. Michele said.

- Sunscreens with an SPF value of 15 or higher should be required to also provide broad-spectrum protection, and for broad-spectrum products, as SPF increases, the magnitude of protection against UVA radiation should also increase. “These proposals are designed to ensure that these products provide consumers with the protections that they expect,” the statement said.

- New sunscreen product labels should be required to make it easier for consumers to identify important information, “including the addition of the active ingredients on the front of the package to bring sunscreen in line with other OTC drugs; a notification on the front label for consumers to read the skin cancer/skin aging alert for sunscreens that have not been shown to help prevent skin cancer; and revised formats for SPF, broad spectrum, and water resistance statements,” the statement said.

- Products that combine sunscreens with insect repellents are not GRASE.

In the meantime, though, consumers should continue to use sunscreens regularly as part of a comprehensive sun protection program, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said during the briefing. “Broad spectrum sunscreens with SPF values of at least 15 are critical to the arsenal of tools for preventing skin cancer and protecting the skin from damage caused by the sun’s rays,” he continued. “Given the recognized public health benefits of sunscreen use, Americans should continue to use sunscreens in conjunction with other sun protective measures (such as protective clothing) as this important rule-making effort moves forward.”

To submit comments on this proposed rule, go to https://www.regulations.gov and follow instructions for submitting comments.

AAD, NPF release two joint guidelines on treatment, management of psoriasis

The .

These guidelines are the first of two papers to be published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD), with four more guidelines on psoriasis to be published later this year in JAAD on phototherapy, topical therapy, nonbiologic systemic medications, and treatment of pediatric patients.

The guideline on biologics updates the 2008 AAD guidelines on psoriasis. In an interview, Alan Menter, MD, cochair of the guidelines work group and lead author of the biologics paper, said the guidelines for biologics were needed because of major advances with the availability of new biologics over the last decade. For example, three tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors were available in 2008, but that number has increased to 10 biologics and now includes agents such as those targeting interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23, IL-17 and IL-23.

In addition, the new guidelines from AAD were developed to represent improvements in the management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as well as the relationship between psoriasis and related comorbidities.

“Major advances in new biologic drugs [are] now available to patients, plus [there have been] significant advances in our understanding of comorbid conditions,” such as cardiovascular comorbidities, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, and clinical professor of dermatology, University of Texas, both in Dallas.

The working group for each set of guidelines consisted of dermatologists, patient representatives, a cardiologist, and a rheumatologist. The biologic guidelines working group analyzed studies published between January 2008 and December 2018 and issued a series of recommendations based on published evidence for the effectiveness, adverse events, and switching for Food and Drug Administration–approved TNF-alpha inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and TNF-alpha biosimilars); IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors (ustekinumab); IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab); and IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab and tildrakizumab, and risankizumab, which is still under FDA review) for monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The biologic guidelines noted that, while FDA-approved biologics were deemed safe overall for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, dermatologists should recognize the adverse effects of these therapies, monitor for infections, and counsel their patients against modifying or discontinuing therapy without first consulting a dermatologist. In general, the working group noted that failure with one biologic does not necessarily mean that a patient will experience failure with a different biologic, even among TNF-alpha and IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors. However, reduced efficacy for a patient receiving a specific TNF-alpha inhibitor may predict reduced efficacy when switching to a different TNF-alpha inhibitor, they said.

In the psoriasis comorbidity guideline, the working group examined the therapeutic interventions for psoriasis-related comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease. They also provided recommendations on the effect of psoriasis on mental health, quality of life, and lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol use.

With respect to cardiovascular disease, the dermatologist should ensure that patients are aware of the association between risk factors for cardiovascular disease and psoriasis, and that they undergo screening for these risk factors, consider lifestyle changes to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, and consult with cardiologists and primary care providers based on individual risk, the guideline states. The working group recommended that patients with psoriasis undergo screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia based on national guidelines, with more frequent screening recommended for patients with psoriasis greater than 10% body surface area or who are eligible for systemic or phototherapy.

In both the biologic and the comorbidity guidelines, the working groups stressed the importance of patient education and the role of the dermatologist in educating patients so that shared decision-making can occur. They noted that education was related to improved quality of life for these patients.

“Both the comorbidities guidelines and the biologic guidelines will help educate the psoriasis population with input from dermatologists in clinical practices,” Dr. Menter said.

However, both working groups noted there are still significant gaps in research, such as the effects of treatment combinations for new biologics and the lack of biomarkers that would identify which biologics are best suited for individual psoriasis patients.

There is also little known about the complex relationship between psoriasis and its comorbidities, and how psoriasis treatment can potentially prevent future disease. To ensure treatment of psoriasis-related comorbidities, dermatologists should consider psoriasis as a systemic disease with multiple comorbidities and interact with primary care doctors, cardiologists, and other providers involved in the care of the patients, Dr. Menter said.

There were no specific funding sources reported for the guidelines. Several authors reported relationships with industry, including pharmaceutical companies with drugs and products involving psoriasis, during the development of the guidelines. If a potential conflict was noted, the working group member recused himself or herself from discussion and drafting of recommendations, according to the paper. Dr. Menter’s disclosure includes serving as a consultant, speaker, investigator, and adviser, and receiving honoraria, from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058.

The .

These guidelines are the first of two papers to be published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD), with four more guidelines on psoriasis to be published later this year in JAAD on phototherapy, topical therapy, nonbiologic systemic medications, and treatment of pediatric patients.

The guideline on biologics updates the 2008 AAD guidelines on psoriasis. In an interview, Alan Menter, MD, cochair of the guidelines work group and lead author of the biologics paper, said the guidelines for biologics were needed because of major advances with the availability of new biologics over the last decade. For example, three tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors were available in 2008, but that number has increased to 10 biologics and now includes agents such as those targeting interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23, IL-17 and IL-23.

In addition, the new guidelines from AAD were developed to represent improvements in the management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as well as the relationship between psoriasis and related comorbidities.

“Major advances in new biologic drugs [are] now available to patients, plus [there have been] significant advances in our understanding of comorbid conditions,” such as cardiovascular comorbidities, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, and clinical professor of dermatology, University of Texas, both in Dallas.

The working group for each set of guidelines consisted of dermatologists, patient representatives, a cardiologist, and a rheumatologist. The biologic guidelines working group analyzed studies published between January 2008 and December 2018 and issued a series of recommendations based on published evidence for the effectiveness, adverse events, and switching for Food and Drug Administration–approved TNF-alpha inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and TNF-alpha biosimilars); IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors (ustekinumab); IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab); and IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab and tildrakizumab, and risankizumab, which is still under FDA review) for monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The biologic guidelines noted that, while FDA-approved biologics were deemed safe overall for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, dermatologists should recognize the adverse effects of these therapies, monitor for infections, and counsel their patients against modifying or discontinuing therapy without first consulting a dermatologist. In general, the working group noted that failure with one biologic does not necessarily mean that a patient will experience failure with a different biologic, even among TNF-alpha and IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors. However, reduced efficacy for a patient receiving a specific TNF-alpha inhibitor may predict reduced efficacy when switching to a different TNF-alpha inhibitor, they said.

In the psoriasis comorbidity guideline, the working group examined the therapeutic interventions for psoriasis-related comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease. They also provided recommendations on the effect of psoriasis on mental health, quality of life, and lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol use.

With respect to cardiovascular disease, the dermatologist should ensure that patients are aware of the association between risk factors for cardiovascular disease and psoriasis, and that they undergo screening for these risk factors, consider lifestyle changes to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, and consult with cardiologists and primary care providers based on individual risk, the guideline states. The working group recommended that patients with psoriasis undergo screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia based on national guidelines, with more frequent screening recommended for patients with psoriasis greater than 10% body surface area or who are eligible for systemic or phototherapy.

In both the biologic and the comorbidity guidelines, the working groups stressed the importance of patient education and the role of the dermatologist in educating patients so that shared decision-making can occur. They noted that education was related to improved quality of life for these patients.

“Both the comorbidities guidelines and the biologic guidelines will help educate the psoriasis population with input from dermatologists in clinical practices,” Dr. Menter said.

However, both working groups noted there are still significant gaps in research, such as the effects of treatment combinations for new biologics and the lack of biomarkers that would identify which biologics are best suited for individual psoriasis patients.

There is also little known about the complex relationship between psoriasis and its comorbidities, and how psoriasis treatment can potentially prevent future disease. To ensure treatment of psoriasis-related comorbidities, dermatologists should consider psoriasis as a systemic disease with multiple comorbidities and interact with primary care doctors, cardiologists, and other providers involved in the care of the patients, Dr. Menter said.

There were no specific funding sources reported for the guidelines. Several authors reported relationships with industry, including pharmaceutical companies with drugs and products involving psoriasis, during the development of the guidelines. If a potential conflict was noted, the working group member recused himself or herself from discussion and drafting of recommendations, according to the paper. Dr. Menter’s disclosure includes serving as a consultant, speaker, investigator, and adviser, and receiving honoraria, from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058.

The .

These guidelines are the first of two papers to be published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (JAAD), with four more guidelines on psoriasis to be published later this year in JAAD on phototherapy, topical therapy, nonbiologic systemic medications, and treatment of pediatric patients.

The guideline on biologics updates the 2008 AAD guidelines on psoriasis. In an interview, Alan Menter, MD, cochair of the guidelines work group and lead author of the biologics paper, said the guidelines for biologics were needed because of major advances with the availability of new biologics over the last decade. For example, three tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors were available in 2008, but that number has increased to 10 biologics and now includes agents such as those targeting interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23, IL-17 and IL-23.

In addition, the new guidelines from AAD were developed to represent improvements in the management of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as well as the relationship between psoriasis and related comorbidities.

“Major advances in new biologic drugs [are] now available to patients, plus [there have been] significant advances in our understanding of comorbid conditions,” such as cardiovascular comorbidities, said Dr. Menter, chairman of the division of dermatology, Baylor University Medical Center, and clinical professor of dermatology, University of Texas, both in Dallas.

The working group for each set of guidelines consisted of dermatologists, patient representatives, a cardiologist, and a rheumatologist. The biologic guidelines working group analyzed studies published between January 2008 and December 2018 and issued a series of recommendations based on published evidence for the effectiveness, adverse events, and switching for Food and Drug Administration–approved TNF-alpha inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and TNF-alpha biosimilars); IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors (ustekinumab); IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab); and IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab and tildrakizumab, and risankizumab, which is still under FDA review) for monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The biologic guidelines noted that, while FDA-approved biologics were deemed safe overall for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, dermatologists should recognize the adverse effects of these therapies, monitor for infections, and counsel their patients against modifying or discontinuing therapy without first consulting a dermatologist. In general, the working group noted that failure with one biologic does not necessarily mean that a patient will experience failure with a different biologic, even among TNF-alpha and IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors. However, reduced efficacy for a patient receiving a specific TNF-alpha inhibitor may predict reduced efficacy when switching to a different TNF-alpha inhibitor, they said.

In the psoriasis comorbidity guideline, the working group examined the therapeutic interventions for psoriasis-related comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease. They also provided recommendations on the effect of psoriasis on mental health, quality of life, and lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol use.

With respect to cardiovascular disease, the dermatologist should ensure that patients are aware of the association between risk factors for cardiovascular disease and psoriasis, and that they undergo screening for these risk factors, consider lifestyle changes to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, and consult with cardiologists and primary care providers based on individual risk, the guideline states. The working group recommended that patients with psoriasis undergo screening for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia based on national guidelines, with more frequent screening recommended for patients with psoriasis greater than 10% body surface area or who are eligible for systemic or phototherapy.

In both the biologic and the comorbidity guidelines, the working groups stressed the importance of patient education and the role of the dermatologist in educating patients so that shared decision-making can occur. They noted that education was related to improved quality of life for these patients.

“Both the comorbidities guidelines and the biologic guidelines will help educate the psoriasis population with input from dermatologists in clinical practices,” Dr. Menter said.

However, both working groups noted there are still significant gaps in research, such as the effects of treatment combinations for new biologics and the lack of biomarkers that would identify which biologics are best suited for individual psoriasis patients.

There is also little known about the complex relationship between psoriasis and its comorbidities, and how psoriasis treatment can potentially prevent future disease. To ensure treatment of psoriasis-related comorbidities, dermatologists should consider psoriasis as a systemic disease with multiple comorbidities and interact with primary care doctors, cardiologists, and other providers involved in the care of the patients, Dr. Menter said.

There were no specific funding sources reported for the guidelines. Several authors reported relationships with industry, including pharmaceutical companies with drugs and products involving psoriasis, during the development of the guidelines. If a potential conflict was noted, the working group member recused himself or herself from discussion and drafting of recommendations, according to the paper. Dr. Menter’s disclosure includes serving as a consultant, speaker, investigator, and adviser, and receiving honoraria, from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Menter A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. Elmets CA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Feb 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Trametinib effectively treats case of giant congenital melanocytic nevus

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

FROM PEDIATRICS

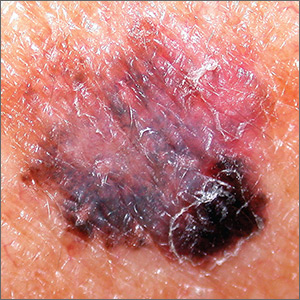

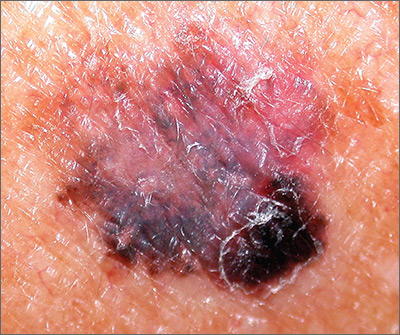

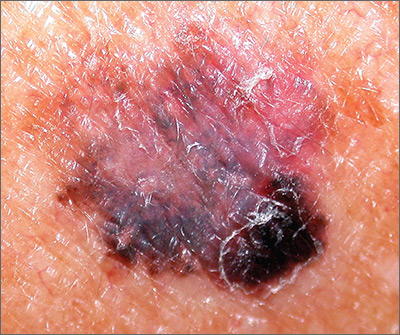

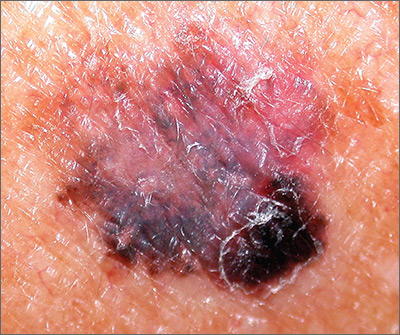

Dark spot on arm

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this was a melanoma or a pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Going through the ABCDE criteria, the FP noted that the spot was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, and the history was positive for an Enlarging lesion. With 5 out of the 5 criteria positive, it was likely that this was a melanoma. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 1- to 2-mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm (a dime is 1.4 mm in depth), which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report came back as invasive melanoma with a 0.25 mm Breslow depth.

The FP referred the patient to a local dermatologist, who agreed to see the patient within the next 2 weeks rather than the standard 3- to 4-month wait time for a new patient. The dermatologist performed a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin down to the fascia. While this melanoma was invasive, this depth did not require sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging. On a follow-up visit, the FP counseled the patient about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams. Note that while brown skin and regular sun exposure may be less risky for melanoma than fair skin with multiple sunburns, anyone can get a melanoma.

Photo courtesy of Eric Kraus, MD and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Onychomycosis that fails terbinafine probably isn’t T. rubrum

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The work up of a case of onychomycosis doesn’t end with the detection of fungal hyphae.

Trichophyton rubrum remains the most common cause of toenail fungus in the United States, but nondermatophyte molds – Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and others – are on the rise, so , according to Nathaniel Jellinek, MD, of the department of dermatology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Standard in-office potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing can’t distinguish one species of fungus from another, nor can pathology with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) or Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Both culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), however, do.

Since few hospitals are equipped to run those tests, Dr. Jellinek uses the Case Western Center for Medical Mycology, in Cleveland, for testing.

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Jellinek explained how to speciate, and the importance of doing so.

He also shared his tips on getting good nail clippings and good scrapings for debris for testing, and explained when KOH testing is enough – and when to opt for more advanced diagnostic methods, including PCR, which he said trumps all previous methods.

Terbinafine is still the best option for T. rubrum, but new topicals are better for nondermatophyte molds. There’s also a clever new dosing regimen for terbinafine, one that should put patients at ease about liver toxicity and other concerns. “If you tell them they’re getting 1 month off in the middle, it seems to go over a little easier,” Dr. Jellinek said.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Tropical travelers’ top dermatologic infestations

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the female sand flea, Tunga penetrans, which burrows into the skin, where it lays hundreds of eggs within a matter of a few days. The sand flea is harbored by dogs, cats, pigs, cows, and rats. It’s rare to encounter tungiasis in travelers who’ve spent their time in fancy resorts, ecolodges, or yoga retreats, even if they’ve been parading around with lots of exposed skin. This is a disease of impoverished neighborhoods; hence, affected Americans often have been doing mission work abroad. In tropical areas, tungiasis is a debilitating, mutilating disorder marked by repeated infections, persistent inflammation, fissures, and ulcers.

Treatment involves a topical antiparasitic agent such as ivermectin, metrifonate, or thiabendazole and removal of the flea with sterile forceps or needles. But there is a promising new treatment concept: topical dimethicone, or polydimethylsiloxane. Studies have shown that following application of dimethicone, roughly 80%-90% of sand fleas are dead within 7 days.

“It’s nontoxic and has a purely physical mechanism of action, so resistance is unlikely ... I think it’s going to change the way this condition gets controlled,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Myiasis

The differential diagnosis of myiasis includes impetigo, a furuncle, an infected cyst, or a retained foreign body. Myiasis is a cutaneous infestation of the larva of certain flies, among the most notorious of which are the botfly, blowfly, and screwfly. The female fly lays her eggs in hot, humid, shady areas in soil contaminated by feces or urine. The larva can invade unbroken skin instantaneously and painlessly. Then it begins burrowing in. An air hole is always present in the skin so the organism can breathe. Ophthalmomyiasis is common, as are nasal and aural infections, the latter often accompanied by complaints of a crawling sensation inside the ear along with a buzzing noise. To avoid infection, in endemic areas it’s important not to go barefoot or to dry clothes on bushes or on the ground. Treatment entails elimination of the larva. Covering the air hole with petroleum jelly will force it to the surface. There is just one larva per furuncle, so no need for further extensive exploration once that critter has been extracted.

Leishmaniasis

The vector for this protozoan infection is the sandfly, which feeds from dusk to dawn noiselessly and painlessly. Because cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are understudied orphan diseases for which current treatments are less than satisfactory, prevention is the watchword. In endemic areas it’s important to close the windows and make use of air conditioning and ceiling fans when available. When in doubt, it’s advisable to sleep using a bed net treated with permethrin.

Cutaneous larva migrans

This skin eruption is caused by parasitic hookworms, the most common of which in the Americas is Ancylostoma braziliense. The eggs are transmitted through dog and cat feces deposited on soil or sand.

“Avoid laying or sitting on dry sand, even on a towel. And wear shoes,” Dr. Mesinkovska advised.

Among the CDC’s treatment recommendations for cutaneous larva migrans are several agents with poor efficacy and/or considerable side effects. But there is one standout therapy.

“Really, I would say nowadays the easiest thing is one 12-mg oral dose of ivermectin. It’s almost 100% effective,” she said.

Dr. Mesinkovska reported having no financial interests relevant to her talk.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the female sand flea, Tunga penetrans, which burrows into the skin, where it lays hundreds of eggs within a matter of a few days. The sand flea is harbored by dogs, cats, pigs, cows, and rats. It’s rare to encounter tungiasis in travelers who’ve spent their time in fancy resorts, ecolodges, or yoga retreats, even if they’ve been parading around with lots of exposed skin. This is a disease of impoverished neighborhoods; hence, affected Americans often have been doing mission work abroad. In tropical areas, tungiasis is a debilitating, mutilating disorder marked by repeated infections, persistent inflammation, fissures, and ulcers.

Treatment involves a topical antiparasitic agent such as ivermectin, metrifonate, or thiabendazole and removal of the flea with sterile forceps or needles. But there is a promising new treatment concept: topical dimethicone, or polydimethylsiloxane. Studies have shown that following application of dimethicone, roughly 80%-90% of sand fleas are dead within 7 days.

“It’s nontoxic and has a purely physical mechanism of action, so resistance is unlikely ... I think it’s going to change the way this condition gets controlled,” Dr. Mesinkovska said.

Myiasis

The differential diagnosis of myiasis includes impetigo, a furuncle, an infected cyst, or a retained foreign body. Myiasis is a cutaneous infestation of the larva of certain flies, among the most notorious of which are the botfly, blowfly, and screwfly. The female fly lays her eggs in hot, humid, shady areas in soil contaminated by feces or urine. The larva can invade unbroken skin instantaneously and painlessly. Then it begins burrowing in. An air hole is always present in the skin so the organism can breathe. Ophthalmomyiasis is common, as are nasal and aural infections, the latter often accompanied by complaints of a crawling sensation inside the ear along with a buzzing noise. To avoid infection, in endemic areas it’s important not to go barefoot or to dry clothes on bushes or on the ground. Treatment entails elimination of the larva. Covering the air hole with petroleum jelly will force it to the surface. There is just one larva per furuncle, so no need for further extensive exploration once that critter has been extracted.

Leishmaniasis

The vector for this protozoan infection is the sandfly, which feeds from dusk to dawn noiselessly and painlessly. Because cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are understudied orphan diseases for which current treatments are less than satisfactory, prevention is the watchword. In endemic areas it’s important to close the windows and make use of air conditioning and ceiling fans when available. When in doubt, it’s advisable to sleep using a bed net treated with permethrin.

Cutaneous larva migrans

This skin eruption is caused by parasitic hookworms, the most common of which in the Americas is Ancylostoma braziliense. The eggs are transmitted through dog and cat feces deposited on soil or sand.

“Avoid laying or sitting on dry sand, even on a towel. And wear shoes,” Dr. Mesinkovska advised.

Among the CDC’s treatment recommendations for cutaneous larva migrans are several agents with poor efficacy and/or considerable side effects. But there is one standout therapy.

“Really, I would say nowadays the easiest thing is one 12-mg oral dose of ivermectin. It’s almost 100% effective,” she said.

Dr. Mesinkovska reported having no financial interests relevant to her talk.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The Caribbean islands and Central and South America are among the most popular travel destinations for Americans. And some of these visitors will come home harboring unwelcome guests: Infestations that will eventually bring them to a dermatologist’s attention.

“I always tell the residents that if a patient’s country of travel starts with a B – Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil – it’s going to be something fun,” Natasha A. Mesinkovska, MD, PhD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

According to surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Society for Travel Medicine,

Cutaneous larva migrans is the easiest to diagnosis because it’s a creeping eruption that often migrates at a rate of 1-2 cm per day. Patients with the other disorders often present with a complaint of a common skin condition – described as a pimple, a wart, a patch of sunburn – that just doesn’t go away, according to Dr. Mesinkovska, director of clinical research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, Irvine.

Tungiasis