User login

When to suspect a severe skin reaction to an AED

NEW ORLEANS – Most skin eruptions in patients taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are relatively benign. With close supervision, some patients with epilepsy may continue treatment despite having a benign drug rash, according to a lecture at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When do you know that you’re not dealing with that kind of eruption?” said Jeanne M. Young, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Signs and symptoms that raise concerns about severe cutaneous reactions include swelling of the face; lesions that are fluid-filled, dusky, or painful; mucus membrane involvement; and signs of systemic involvement.

Associations with anticonvulsants

Diffuse swelling of the face is a hallmark symptom of DRESS. Fluid-filled lesions such as pustules, vesicles, and bullae indicate a condition other than a benign drug eruption. Signs of systemic involvement may include fever, marked eosinophilia, transaminitis, and evidence of lymphocyte activation. “In general, I want to see systemic involvement that can’t be explained by the patient’s other systemic diseases,” Dr. Young said.

A 2018 study found that AEDs are associated with SJS and TEN, and the labels for lamotrigine and carbamazepine include black box warnings about the risk of severe cutaneous adverse events. Carbamazepine’s warning, which was added in 2007, notes that SJS and TEN are significantly more common in patients of Asian ancestry with the human leukocyte antigen allele HLA-B*1502 and that physicians should screen at-risk patients before starting treatment.

Benign drug rashes

Morbilliform drug eruptions, sometimes called benign exanthems, are “by far the most common drug rash that we see” and typically are “the rashes that people refer to as drug rashes,” Dr. Young said. The mechanisms appear to be primarily immune complex mediated and cell mediated. “When the drug is stopped, these rashes tend to go away quite predictably in 2-3 weeks.”

For any class of drug, about 1% of people taking that medication may have this type of reaction, Dr. Young said. “We expect to see erythematous papules and plaques that oftentimes become confluent on the skin.” These reactions generally occur 7-10 days after the first exposure to the medication, and most patients do not have other symptoms, although the rash may itch. In addition, patients may have erythroderma with desquamation. “I think it’s important to point out the difference between desquamation, which is loss of the stratum corneum, and epidermal sloughing, which is what you see in something like [SJS] or TEN, where you’re actually losing the entire epidermis,” Dr. Young said. Recovering from desquamation is “sort of like recovering from a sun burn, and it’s not particularly dangerous.” Management of morbilliform drug eruptions is largely symptomatic.

Treat through, taper, or rechallenge

In the case a benign drug rash, “if you feel like you … need to keep a patient on a drug, you do have that option with close supervision,” Dr. Young said. “Communicate that with the dermatologist. Say, ‘I have really struggled getting this patient stabilized. Can we keep them on this drug?’ ”

The dermatologist may not fully realize the implications of stopping an effective AED in a patient with seizures that have been difficult to control. If the drug rash is benign, treating through may be an option. Patients often resolve the rash while continuing the medication, which may be because of desensitization, Dr. Young said. If a patient’s symptoms are too great to continue the drug, neurologists have the option of slowly tapering the drug and reinitiating with a new drug, Dr. Young said. Neurologists also may choose to rechallenge.

If a patient is on several medications, making it difficult to elucidate a causative agent, after stopping those drugs and allowing the rash to resolve, “there is little danger in restarting a medication,” she said.

Benign rash or DRESS?

“When I see a morbilliform eruption, usually what’s on my mind is, ‘Is this just a drug rash or is this DRESS?’ ” Dr. Young said. DRESS often starts with a morbilliform eruption that is indistinguishable from a benign drug eruption.

“Timing is a major difference,” she said. “If a patient develops a morbilliform drug eruption much later than I would expect, then my suspicion [for DRESS] goes up.” Patients with DRESS often have fever and systemic symptoms. Proposed DRESS diagnostic criteria can be useful, but clinical judgment still plays a key role. If a patient does not satisfy diagnostic criteria but has some signs and is taking a drug that is associated with DRESS, “it is going to make me more suspicious and maybe make me recommend stopping that drug sooner,” she said. Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital are among the drugs most commonly associated with DRESS.

Toxic erythemas

Patients may present with toxic erythemas, such as fixed drug reactions, erythema multiforme, SJS, and TEN. These drug reactions appear similar on biopsy but have different courses.

A patient with a fixed drug reaction often has a single lesion, and the lesion will occur in the same location every time the patient is exposed to the drug. Patients may develop additional lesions with subsequent exposures. These lesions typically are large, erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with central duskiness. “They can be bullous in the center, and they typically will heal with pigmentation, which is unique to this particular drug reaction,” said Dr. Young. “When it gets more concerning and most important to differentiate is when you get generalized bullous fixed drug eruption.” Generalized bullous fixed drug eruptions mimic and are difficult to clinically distinguish from TEN, which has a much has a much poorer prognosis.

Patients with a fixed drug eruption are not as ill as patients with TEN and tend not to slough their skin to the extent seen with TEN. Interferon gamma, perforin, and Fas ligand have been implicated as mechanisms involved in fixed drug reactions. Unlike in TEN, regulatory T cells are abundant, which may explain why TEN and fixed drug reactions progress differently even though they appear to share pathologic mechanisms, Dr. Young said.

Erythema multiforme generally presents with classic target lesions and little mucosal involvement. Infections, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, may trigger erythema multiforme. Dr. Young recommends evaluating patients for HSV and checking serologies, even if patients have never had a herpes outbreak. “If you have no evidence for infection, you do have to consider discontinuing a medication,” she said.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN

SJS and TEN are “the rarest of the severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions” and have “the highest morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Young said. They appear to exist on a continuum where SJS may represent early TEN.

“This is a situation where you expect to see blistering of the skin [and] always mucosal involvement. You need to stop the drug immediately when you suspect this drug reaction,” Dr. Young said.

One reason to distinguish SJS or early TEN from later TEN is that high-dose steroids may play a role in the treatment of SJS or early TEN. “Once you get past about 10% total body surface area, there is good evidence that steroids actually increase morbidity and mortality,” she said.

If the eruption has occurred before, that factor suggests that a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or fixed drug reaction may be more likely than TEN.

An apparent lack of regulatory T cells in TEN could explain why patients with HIV infection are at much higher risk of developing SJS and TEN. Understanding the role that regulatory T cells play in severe drug eruptions may lead to new therapeutic options in the future, Dr. Young said.

Dr. Young had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Most skin eruptions in patients taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are relatively benign. With close supervision, some patients with epilepsy may continue treatment despite having a benign drug rash, according to a lecture at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When do you know that you’re not dealing with that kind of eruption?” said Jeanne M. Young, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Signs and symptoms that raise concerns about severe cutaneous reactions include swelling of the face; lesions that are fluid-filled, dusky, or painful; mucus membrane involvement; and signs of systemic involvement.

Associations with anticonvulsants

Diffuse swelling of the face is a hallmark symptom of DRESS. Fluid-filled lesions such as pustules, vesicles, and bullae indicate a condition other than a benign drug eruption. Signs of systemic involvement may include fever, marked eosinophilia, transaminitis, and evidence of lymphocyte activation. “In general, I want to see systemic involvement that can’t be explained by the patient’s other systemic diseases,” Dr. Young said.

A 2018 study found that AEDs are associated with SJS and TEN, and the labels for lamotrigine and carbamazepine include black box warnings about the risk of severe cutaneous adverse events. Carbamazepine’s warning, which was added in 2007, notes that SJS and TEN are significantly more common in patients of Asian ancestry with the human leukocyte antigen allele HLA-B*1502 and that physicians should screen at-risk patients before starting treatment.

Benign drug rashes

Morbilliform drug eruptions, sometimes called benign exanthems, are “by far the most common drug rash that we see” and typically are “the rashes that people refer to as drug rashes,” Dr. Young said. The mechanisms appear to be primarily immune complex mediated and cell mediated. “When the drug is stopped, these rashes tend to go away quite predictably in 2-3 weeks.”

For any class of drug, about 1% of people taking that medication may have this type of reaction, Dr. Young said. “We expect to see erythematous papules and plaques that oftentimes become confluent on the skin.” These reactions generally occur 7-10 days after the first exposure to the medication, and most patients do not have other symptoms, although the rash may itch. In addition, patients may have erythroderma with desquamation. “I think it’s important to point out the difference between desquamation, which is loss of the stratum corneum, and epidermal sloughing, which is what you see in something like [SJS] or TEN, where you’re actually losing the entire epidermis,” Dr. Young said. Recovering from desquamation is “sort of like recovering from a sun burn, and it’s not particularly dangerous.” Management of morbilliform drug eruptions is largely symptomatic.

Treat through, taper, or rechallenge

In the case a benign drug rash, “if you feel like you … need to keep a patient on a drug, you do have that option with close supervision,” Dr. Young said. “Communicate that with the dermatologist. Say, ‘I have really struggled getting this patient stabilized. Can we keep them on this drug?’ ”

The dermatologist may not fully realize the implications of stopping an effective AED in a patient with seizures that have been difficult to control. If the drug rash is benign, treating through may be an option. Patients often resolve the rash while continuing the medication, which may be because of desensitization, Dr. Young said. If a patient’s symptoms are too great to continue the drug, neurologists have the option of slowly tapering the drug and reinitiating with a new drug, Dr. Young said. Neurologists also may choose to rechallenge.

If a patient is on several medications, making it difficult to elucidate a causative agent, after stopping those drugs and allowing the rash to resolve, “there is little danger in restarting a medication,” she said.

Benign rash or DRESS?

“When I see a morbilliform eruption, usually what’s on my mind is, ‘Is this just a drug rash or is this DRESS?’ ” Dr. Young said. DRESS often starts with a morbilliform eruption that is indistinguishable from a benign drug eruption.

“Timing is a major difference,” she said. “If a patient develops a morbilliform drug eruption much later than I would expect, then my suspicion [for DRESS] goes up.” Patients with DRESS often have fever and systemic symptoms. Proposed DRESS diagnostic criteria can be useful, but clinical judgment still plays a key role. If a patient does not satisfy diagnostic criteria but has some signs and is taking a drug that is associated with DRESS, “it is going to make me more suspicious and maybe make me recommend stopping that drug sooner,” she said. Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital are among the drugs most commonly associated with DRESS.

Toxic erythemas

Patients may present with toxic erythemas, such as fixed drug reactions, erythema multiforme, SJS, and TEN. These drug reactions appear similar on biopsy but have different courses.

A patient with a fixed drug reaction often has a single lesion, and the lesion will occur in the same location every time the patient is exposed to the drug. Patients may develop additional lesions with subsequent exposures. These lesions typically are large, erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with central duskiness. “They can be bullous in the center, and they typically will heal with pigmentation, which is unique to this particular drug reaction,” said Dr. Young. “When it gets more concerning and most important to differentiate is when you get generalized bullous fixed drug eruption.” Generalized bullous fixed drug eruptions mimic and are difficult to clinically distinguish from TEN, which has a much has a much poorer prognosis.

Patients with a fixed drug eruption are not as ill as patients with TEN and tend not to slough their skin to the extent seen with TEN. Interferon gamma, perforin, and Fas ligand have been implicated as mechanisms involved in fixed drug reactions. Unlike in TEN, regulatory T cells are abundant, which may explain why TEN and fixed drug reactions progress differently even though they appear to share pathologic mechanisms, Dr. Young said.

Erythema multiforme generally presents with classic target lesions and little mucosal involvement. Infections, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, may trigger erythema multiforme. Dr. Young recommends evaluating patients for HSV and checking serologies, even if patients have never had a herpes outbreak. “If you have no evidence for infection, you do have to consider discontinuing a medication,” she said.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN

SJS and TEN are “the rarest of the severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions” and have “the highest morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Young said. They appear to exist on a continuum where SJS may represent early TEN.

“This is a situation where you expect to see blistering of the skin [and] always mucosal involvement. You need to stop the drug immediately when you suspect this drug reaction,” Dr. Young said.

One reason to distinguish SJS or early TEN from later TEN is that high-dose steroids may play a role in the treatment of SJS or early TEN. “Once you get past about 10% total body surface area, there is good evidence that steroids actually increase morbidity and mortality,” she said.

If the eruption has occurred before, that factor suggests that a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or fixed drug reaction may be more likely than TEN.

An apparent lack of regulatory T cells in TEN could explain why patients with HIV infection are at much higher risk of developing SJS and TEN. Understanding the role that regulatory T cells play in severe drug eruptions may lead to new therapeutic options in the future, Dr. Young said.

Dr. Young had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Most skin eruptions in patients taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are relatively benign. With close supervision, some patients with epilepsy may continue treatment despite having a benign drug rash, according to a lecture at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“When do you know that you’re not dealing with that kind of eruption?” said Jeanne M. Young, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Signs and symptoms that raise concerns about severe cutaneous reactions include swelling of the face; lesions that are fluid-filled, dusky, or painful; mucus membrane involvement; and signs of systemic involvement.

Associations with anticonvulsants

Diffuse swelling of the face is a hallmark symptom of DRESS. Fluid-filled lesions such as pustules, vesicles, and bullae indicate a condition other than a benign drug eruption. Signs of systemic involvement may include fever, marked eosinophilia, transaminitis, and evidence of lymphocyte activation. “In general, I want to see systemic involvement that can’t be explained by the patient’s other systemic diseases,” Dr. Young said.

A 2018 study found that AEDs are associated with SJS and TEN, and the labels for lamotrigine and carbamazepine include black box warnings about the risk of severe cutaneous adverse events. Carbamazepine’s warning, which was added in 2007, notes that SJS and TEN are significantly more common in patients of Asian ancestry with the human leukocyte antigen allele HLA-B*1502 and that physicians should screen at-risk patients before starting treatment.

Benign drug rashes

Morbilliform drug eruptions, sometimes called benign exanthems, are “by far the most common drug rash that we see” and typically are “the rashes that people refer to as drug rashes,” Dr. Young said. The mechanisms appear to be primarily immune complex mediated and cell mediated. “When the drug is stopped, these rashes tend to go away quite predictably in 2-3 weeks.”

For any class of drug, about 1% of people taking that medication may have this type of reaction, Dr. Young said. “We expect to see erythematous papules and plaques that oftentimes become confluent on the skin.” These reactions generally occur 7-10 days after the first exposure to the medication, and most patients do not have other symptoms, although the rash may itch. In addition, patients may have erythroderma with desquamation. “I think it’s important to point out the difference between desquamation, which is loss of the stratum corneum, and epidermal sloughing, which is what you see in something like [SJS] or TEN, where you’re actually losing the entire epidermis,” Dr. Young said. Recovering from desquamation is “sort of like recovering from a sun burn, and it’s not particularly dangerous.” Management of morbilliform drug eruptions is largely symptomatic.

Treat through, taper, or rechallenge

In the case a benign drug rash, “if you feel like you … need to keep a patient on a drug, you do have that option with close supervision,” Dr. Young said. “Communicate that with the dermatologist. Say, ‘I have really struggled getting this patient stabilized. Can we keep them on this drug?’ ”

The dermatologist may not fully realize the implications of stopping an effective AED in a patient with seizures that have been difficult to control. If the drug rash is benign, treating through may be an option. Patients often resolve the rash while continuing the medication, which may be because of desensitization, Dr. Young said. If a patient’s symptoms are too great to continue the drug, neurologists have the option of slowly tapering the drug and reinitiating with a new drug, Dr. Young said. Neurologists also may choose to rechallenge.

If a patient is on several medications, making it difficult to elucidate a causative agent, after stopping those drugs and allowing the rash to resolve, “there is little danger in restarting a medication,” she said.

Benign rash or DRESS?

“When I see a morbilliform eruption, usually what’s on my mind is, ‘Is this just a drug rash or is this DRESS?’ ” Dr. Young said. DRESS often starts with a morbilliform eruption that is indistinguishable from a benign drug eruption.

“Timing is a major difference,” she said. “If a patient develops a morbilliform drug eruption much later than I would expect, then my suspicion [for DRESS] goes up.” Patients with DRESS often have fever and systemic symptoms. Proposed DRESS diagnostic criteria can be useful, but clinical judgment still plays a key role. If a patient does not satisfy diagnostic criteria but has some signs and is taking a drug that is associated with DRESS, “it is going to make me more suspicious and maybe make me recommend stopping that drug sooner,” she said. Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital are among the drugs most commonly associated with DRESS.

Toxic erythemas

Patients may present with toxic erythemas, such as fixed drug reactions, erythema multiforme, SJS, and TEN. These drug reactions appear similar on biopsy but have different courses.

A patient with a fixed drug reaction often has a single lesion, and the lesion will occur in the same location every time the patient is exposed to the drug. Patients may develop additional lesions with subsequent exposures. These lesions typically are large, erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with central duskiness. “They can be bullous in the center, and they typically will heal with pigmentation, which is unique to this particular drug reaction,” said Dr. Young. “When it gets more concerning and most important to differentiate is when you get generalized bullous fixed drug eruption.” Generalized bullous fixed drug eruptions mimic and are difficult to clinically distinguish from TEN, which has a much has a much poorer prognosis.

Patients with a fixed drug eruption are not as ill as patients with TEN and tend not to slough their skin to the extent seen with TEN. Interferon gamma, perforin, and Fas ligand have been implicated as mechanisms involved in fixed drug reactions. Unlike in TEN, regulatory T cells are abundant, which may explain why TEN and fixed drug reactions progress differently even though they appear to share pathologic mechanisms, Dr. Young said.

Erythema multiforme generally presents with classic target lesions and little mucosal involvement. Infections, most commonly herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, may trigger erythema multiforme. Dr. Young recommends evaluating patients for HSV and checking serologies, even if patients have never had a herpes outbreak. “If you have no evidence for infection, you do have to consider discontinuing a medication,” she said.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and TEN

SJS and TEN are “the rarest of the severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions” and have “the highest morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Young said. They appear to exist on a continuum where SJS may represent early TEN.

“This is a situation where you expect to see blistering of the skin [and] always mucosal involvement. You need to stop the drug immediately when you suspect this drug reaction,” Dr. Young said.

One reason to distinguish SJS or early TEN from later TEN is that high-dose steroids may play a role in the treatment of SJS or early TEN. “Once you get past about 10% total body surface area, there is good evidence that steroids actually increase morbidity and mortality,” she said.

If the eruption has occurred before, that factor suggests that a diagnosis of erythema multiforme or fixed drug reaction may be more likely than TEN.

An apparent lack of regulatory T cells in TEN could explain why patients with HIV infection are at much higher risk of developing SJS and TEN. Understanding the role that regulatory T cells play in severe drug eruptions may lead to new therapeutic options in the future, Dr. Young said.

Dr. Young had no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AES 2018

A Faux Fungal Affliction

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

A 45-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for a “fungal infection” that has failed to respond to the following treatments: topical clotrimazole cream, topical miconazole cream, a 30-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), and a 2-month course of oral griseofulvin (unknown dose). The lesions are completely asymptomatic but quite worrisome to the patient since they manifested 6 months ago.

She has consulted at least 6 different providers—none of whom was a dermatologist but all of whom were certain of the diagnosis and thus felt no need to refer the patient. However, the passage of time and trail of ineffective treatments finally prompts the (albeit reluctant) decision to send the patient to dermatology.

On questioning, she denies any serious health problems, such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She has had no contact with any animals or children.

EXAMINATION

The lesions in question total 6; all are uniformly purplish brown, round, and macular, and they range from 5 mm to more than 3 cm. Most are located on the bilateral popliteal areas. The lesions have sharp, well-defined margins. Several have faintly raised papular margins that give the centers a slightly concave appearance.

Palpation reveals the complete absence of any surface disturbance, such as scaling or erosion. Thus, no KOH prep can be performed to check for fungal elements. Instead, a shave biopsy is performed, the results of which show a sawtooth-patterned lymphocytic infiltrate obliterating the normally smooth undulating dermoepidermal junction.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case effectively demonstrates the principle that, when confronted with round or annular lesions, some providers will rely on the diagnosis of “fungal” even when evidence (eg, failed treatment attempts) suggests otherwise. What that nonresponse should do is signal the need for an expanded differential—that is, a consideration of other diagnostic possibilities. This is a bedrock principle in every medical specialty, not just in dermatology.

In this case, the biopsy results clearly pointed to the correct diagnosis of lichen planus (LP), a common dermatosis well known to present in annular morphology. LP is a benign process, albeit one that is occasionally quite bothersome (eg, itching) and, rarely, widespread. LP’s more typical distribution is on volar wrists, in the sacral areas, and occasionally on genitals, so the inability to make a visual diagnosis in this case is forgivable.

Although LP’s etiology is unfortunately unknown, what is known is how to treat it: with topical steroids when necessary or “tincture of time,” as in this patient’s asymptomatic case. LP typically resolves on its own, and it has no worrisome import or connections to more serious disease.

But as always, the first step to correct diagnosis is to consider letting go of the old diagnosis—fungal infection—which was clearly incorrect given the lack of response to numerous antifungals. The second step is to consider other possibilities, which would include lichen planus, psoriasis, granuloma annulare, tinea versicolor, and necrobiosis. The third step is to perform a biopsy, which would establish the correct diagnosis with certainty and in turn, dictate correct treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- There is an extensive differential for round or annular skin lesions that includes many nonfungal causes.

- When antifungals fail to help, consider other diagnostic possibilities.

- Perform a biopsy when a visual diagnosis is not possible.

- Lichen planus (LP) is a common benign inflammatory skin condition that can present with annular lesions.

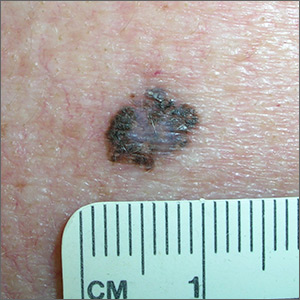

Irregular macule on back

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected that this could be a melanoma and took out his dermatoscope. (See “Dermoscopy in family medicine: A primer.”) The FP was initially concerned about melanoma because the lesion appeared chaotic, with multiple colors and an irregular border. Going through the ABCDE criteria, he noted that the macule was Asymmetric, the Border was irregular, the Colors were varied, the Diameter was >6 mm, but the history was insufficient to say whether it was Enlarging. Of course, 4 out of 5 positive criteria requires a tissue diagnosis.

Dermoscopy added evidence for regression in the center and an atypical network in the brown and black areas. The FP performed a deep shave biopsy (saucerization) with 2 mm margins to provide full sampling for the pathologist. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”) The depth of the tissue biopsy was approximately 1 to 1.5 mm, which was adequate for a lesion of this type. The pathology report confirmed melanoma in situ.

On a return visit, the FP performed a local wide excision with 5 mm margins down to the deep fat. The surgical specimen revealed only the scar at the biopsy site with no remaining cancer. This reassured the patient because it should provide a cure very near 100%. The FP provided counseling about sun protection and the need for regular skin exams.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Karnes J, Usatine R. Melanoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:1112-1123.

To learn more about the newest 3rd edition of the Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, see: https://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Synopsis-Family-Medicine/dp/1259862046/

You can get the Color Atlas of Family Medicine app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

New atopic dermatitis agents expand treatment options

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

GRAND CAYMAN, CAYMAN ISLANDS –

Moisturizers that confer skin barrier protection, lipid-replenishing topicals, and some biologics are available now or will soon be available for patients with AD, Joseph Fowler Jr., MD, said at the Caribbean Dermatology Symposium provided by Global Academy for Medical Education.

With the approval of dupilumab for moderate to severe disease in 2017, a biologic finally became available for treating AD, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.). While it’s not a cure and may take as long as 6 months to really kick in, “I think almost everyone gets some benefit from it. And although it’s not approved yet for anyone under 18, I’m sure it will be.”

He provided a brief rundown of dupilumab; crisaborole, another relatively new agent for AD; and some agents that are being investigated.

- Dupilumab. For AD, dupilumab, which inhibits interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, is usually started at 600 mg, then tapered to 300 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Its pivotal data showed a mean 70% decrease in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores over 16 weeks at that dose.*

“Again, I would say most patients do get benefit from this, but they might not see it for more than 3 months, and even up to 6 months. I’m not sure why, but some develop eye symptoms – I think these are more severe cases who also have respiratory atopy. I would also be interested to see if dupilumab might work on patients with chronic hand eczema,” he said.

- Crisaborole ointment 2%. A nonsteroidal topical phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor approved in 2016 for mild to moderate AD in people aged 2 and older, crisaborole (Eucrisa) blocks the release of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which is elevated in AD. Lower cAMP levels lead to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. In its pivotal phase 3 study, about 35% of patients achieved clinical success – an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 0 or 1, or at least a two-grade improvement over baseline.

“In my opinion, it’s similar or slightly better than topical corticosteroids, and safer as well, especially in our younger patients, or when the face or intertriginous areas are involved,” Dr. Fowler said. “There is often some application site stinging and burning. If you put it in the fridge and get it good and cold when it goes on, that seems to moderate the sensation. It’s a good steroid-sparing option.”

Crisaborole is now being investigated for use in infants aged 3-24 months with mild to moderate AD.

- Tofacitinib ointment. This topical form of tofacitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 and 3, is being evaluated in a placebo-controlled trial in adults with mild to moderate AD. There are also a few reports of oral tofacitinib improving AD, including a case report (Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Dec;42[8]:942-4). Dr. Fowler noted a small series of six adults with moderate to severe AD uncontrolled with methotrexate or azathioprine. The patients received oral tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day for 8-29 weeks; there was a mean 67% improvement in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index.

- Ustekinumab. The interleukin-12 and -23 antagonist indicated for moderate to severe psoriasis has also made an appearance in the AD literature, including an Austrian report of three patients with severe AD who received 45 mg of ustekinumab (Stelara) subcutaneously at 0, 4 and 12 weeks. By week 16, all of them experienced a 50% reduction in their EASI score, with a marked reduction in interleukin-22 markers (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jan;76[1]:91-7.e3).

But no matter which therapy is chosen, regular moisturizing is critically important, Dr. Fowler remarked. Expensive prescription moisturizers are available, but he questioned whether they offer any cost-worthy extra benefit over a good nonprescription moisturizer.

“Do these super-moisturizers protect the skin barrier any more than petrolatum? I can’t answer that. They promise better results, but each patient and doc have to make the decision. If your patient can afford it, maybe some will be better for their skin, but really, it’s not as important as some of the other medications. So, I tell them, if cost is an issue, don’t worry about the fancy moisturizers.”

Dr. Fowler disclosed relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Correction, 2/15/19: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized the chemical action of dupilumab.

REPORTING FROM THE CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Hidradenitis suppurativa linked to increased lymphoma risk

Lymphomas appear to be up to four times more likely in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than among the general population, Rachel Tannenbaum and her colleagues reported in a Research Letter in JAMA Dermatology.

The risks of Hodgkin (HL), non-Hodgkin (NHL), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) all were significantly higher among patients with HS, wrote Ms. Tannenbaum, Andrew Strunk, and Amit Garg, MD. Males and older patients carried higher risks than females and younger patients, they found.

The team members, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a health care database study comprising 55 million patients included in 27 integrated U.S. health care systems. All the subjects were at least 18 years old; records indicated active HS during the study period of 2013-2018. A regression analysis controlled for age and sex.

The database contained 62,690 patients with HS. The majority (74%) were female and were aged 44 years or younger (57%).

All three lymphomas were more common among HS patients than patients without HS, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (0.40% vs. 0.35%,) Hodgkin lymphoma (0.17% vs. 0.09%), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (0.06% vs. 0.02%).

The multivariate analysis determined that HS patients were twice as likely to develop both non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma (odds ratio, 2.0 and 2.21, respectively). They were four times more likely to develop cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (OR, 4.31).

All three lymphomas were more common among males than females: NHL, 0.62% vs. 0.32%; HL, 0.28% vs. 0.13%; and CTCL, 0.09% vs. 0.04%. This translated into significantly increased HS-associated risks, Ms. Tannenbaum and her coauthors noted. “For example, the [odds ratios] for the association between HS and HL were higher in males (OR, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-3.99) than in females (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.44-2.39) (P = .02),” they wrote.

Lymphomas were more common among HS patients in every age group. Patients with HS aged 45-64 years were 38% more likely to develop NHL, and those older than 65, about twice as likely (OR, 1.99).

“To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to systematically evaluate this association in a U.S. population of patients with HS,” the research team concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from AbbVie. Ms. Tannenbaum and Mr. Strunk reported no disclosures. Dr. Garg reported financial relationships with AbbVie and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tannenbaum R et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230.

Lymphomas appear to be up to four times more likely in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than among the general population, Rachel Tannenbaum and her colleagues reported in a Research Letter in JAMA Dermatology.

The risks of Hodgkin (HL), non-Hodgkin (NHL), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) all were significantly higher among patients with HS, wrote Ms. Tannenbaum, Andrew Strunk, and Amit Garg, MD. Males and older patients carried higher risks than females and younger patients, they found.

The team members, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a health care database study comprising 55 million patients included in 27 integrated U.S. health care systems. All the subjects were at least 18 years old; records indicated active HS during the study period of 2013-2018. A regression analysis controlled for age and sex.

The database contained 62,690 patients with HS. The majority (74%) were female and were aged 44 years or younger (57%).

All three lymphomas were more common among HS patients than patients without HS, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (0.40% vs. 0.35%,) Hodgkin lymphoma (0.17% vs. 0.09%), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (0.06% vs. 0.02%).

The multivariate analysis determined that HS patients were twice as likely to develop both non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma (odds ratio, 2.0 and 2.21, respectively). They were four times more likely to develop cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (OR, 4.31).

All three lymphomas were more common among males than females: NHL, 0.62% vs. 0.32%; HL, 0.28% vs. 0.13%; and CTCL, 0.09% vs. 0.04%. This translated into significantly increased HS-associated risks, Ms. Tannenbaum and her coauthors noted. “For example, the [odds ratios] for the association between HS and HL were higher in males (OR, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-3.99) than in females (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.44-2.39) (P = .02),” they wrote.

Lymphomas were more common among HS patients in every age group. Patients with HS aged 45-64 years were 38% more likely to develop NHL, and those older than 65, about twice as likely (OR, 1.99).

“To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to systematically evaluate this association in a U.S. population of patients with HS,” the research team concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from AbbVie. Ms. Tannenbaum and Mr. Strunk reported no disclosures. Dr. Garg reported financial relationships with AbbVie and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tannenbaum R et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230.

Lymphomas appear to be up to four times more likely in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than among the general population, Rachel Tannenbaum and her colleagues reported in a Research Letter in JAMA Dermatology.

The risks of Hodgkin (HL), non-Hodgkin (NHL), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) all were significantly higher among patients with HS, wrote Ms. Tannenbaum, Andrew Strunk, and Amit Garg, MD. Males and older patients carried higher risks than females and younger patients, they found.

The team members, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a health care database study comprising 55 million patients included in 27 integrated U.S. health care systems. All the subjects were at least 18 years old; records indicated active HS during the study period of 2013-2018. A regression analysis controlled for age and sex.

The database contained 62,690 patients with HS. The majority (74%) were female and were aged 44 years or younger (57%).

All three lymphomas were more common among HS patients than patients without HS, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (0.40% vs. 0.35%,) Hodgkin lymphoma (0.17% vs. 0.09%), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (0.06% vs. 0.02%).

The multivariate analysis determined that HS patients were twice as likely to develop both non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma (odds ratio, 2.0 and 2.21, respectively). They were four times more likely to develop cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (OR, 4.31).

All three lymphomas were more common among males than females: NHL, 0.62% vs. 0.32%; HL, 0.28% vs. 0.13%; and CTCL, 0.09% vs. 0.04%. This translated into significantly increased HS-associated risks, Ms. Tannenbaum and her coauthors noted. “For example, the [odds ratios] for the association between HS and HL were higher in males (OR, 2.97; 95% confidence interval, 2.22-3.99) than in females (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.44-2.39) (P = .02),” they wrote.

Lymphomas were more common among HS patients in every age group. Patients with HS aged 45-64 years were 38% more likely to develop NHL, and those older than 65, about twice as likely (OR, 1.99).

“To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to systematically evaluate this association in a U.S. population of patients with HS,” the research team concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from AbbVie. Ms. Tannenbaum and Mr. Strunk reported no disclosures. Dr. Garg reported financial relationships with AbbVie and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Tannenbaum R et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Hidradenitis suppurativa appears to increase the risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Major finding: Lymphomas are up to four times more common among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa than those without the chronic inflammatory disorder.

Study details: The database review comprised more than 55 million patients in 27 linked health care systems.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from AbbVie. Ms. Tannenbaum and Mr. Strunk reported no disclosures. Dr. Garg reported financial relationships with AbbVie and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Tannenbaum R et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5230.

What is your diagnosis?

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment

LAHS is self-limited and does not necessitate treatment. However, if patients or parents feel there is significant disease burden, perhaps with poor effects on quality of life or with psychosocial impairment, treatment with minoxidil 5% solution has been studied with some success reported in the literature.1,8,9

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Natsis and Dr. Eichenfield had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):501-6.

2. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):96-100.

3. Pediatric Dermatol. 2016:33(50):507-10.

4. Dermatol Clin. 1986;14:745-51.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(10):1123-8.

6. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-3.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):868-74.

8. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e286-e287.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:389-90.

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment

LAHS is self-limited and does not necessitate treatment. However, if patients or parents feel there is significant disease burden, perhaps with poor effects on quality of life or with psychosocial impairment, treatment with minoxidil 5% solution has been studied with some success reported in the literature.1,8,9

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Natsis and Dr. Eichenfield had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):501-6.

2. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):96-100.

3. Pediatric Dermatol. 2016:33(50):507-10.

4. Dermatol Clin. 1986;14:745-51.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(10):1123-8.

6. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-3.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):868-74.

8. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e286-e287.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:389-90.

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment