User login

Don’t discount sleep disturbance for children with atopic dermatitis

The itching associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) may interfere with children’s sleep, and sleep studies suggest that children with active disease are more restless at night, wrote Faustine D. Ramirez of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Acute and chronic sleep disturbances have been associated with a wide range of cognitive, mood, and behavioral impairments and have been linked to poor educational performance,” the researchers noted.

To determine the impact of active AD on children’s sleep, the researchers reviewed data from 13,988 children followed for a median of 11 years. Of these, 4,938 children met the definition for AD between age 2 and 16 years.

Overall, children with active AD were approximately 50% more likely to experience poor sleep quality than were those without AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.48). Sleep quality was even worse for children with severe active AD (aOR, 1.68), and active AD plus asthma or allergic rhinitis (aOR 2.15). Sleep quality was significantly worse in children reporting mild AD (aOR, 1.40) or inactive AD (aOR, 1.41), compared with children without AD. Nighttime sleep duration was similar throughout childhood for children with and without AD.

“In addition to increased nighttime awakenings and difficulty falling asleep, we found that children with active atopic dermatitis were more likely to report nightmares and early morning awakenings, which has not been previously studied,” Ms. Ramirez and her associates said.

Total sleep duration was statistically shorter overall for children with AD, compared with those without AD, but the difference was not clinically significant, they noted.

The participants were from a longitudinal study in the United Kingdom in which pregnant women were recruited between 1990 and 1992. For those with children alive at 1 year, their children were followed for approximately 16 years. Sleep quality was assessed at six time points with four standardized questionnaires between ages 2 and 10 years, and sleep duration was assessed at eight time points between ages 2 and 16 years with standardized questionnaires.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including some missing data and patient attrition, as well as possible misclassification bias because of the use of parent and patient self-reports, and a possible lack of generalizability to other populations, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the need for developing clinical outcome measures to address sleep quality in children with AD, they said. “Additional work should investigate interventions to improve sleep quality and examine the association between atopic dermatitis treatment and children’s sleep.”

The study was funded primarily by a grant from the National Eczema Association. Ms. Ramirez disclosed a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two other investigators received grants, one from NIH and the other Wellcome Senior Clinical Fellowship in Science. One coauthor reported receiving multiple grants, as well as paid consulting for TARGETPharma, a company developing a prospective atopic dermatitis registry.

SOURCE: Ramirez FD al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025.

The itching associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) may interfere with children’s sleep, and sleep studies suggest that children with active disease are more restless at night, wrote Faustine D. Ramirez of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Acute and chronic sleep disturbances have been associated with a wide range of cognitive, mood, and behavioral impairments and have been linked to poor educational performance,” the researchers noted.

To determine the impact of active AD on children’s sleep, the researchers reviewed data from 13,988 children followed for a median of 11 years. Of these, 4,938 children met the definition for AD between age 2 and 16 years.

Overall, children with active AD were approximately 50% more likely to experience poor sleep quality than were those without AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.48). Sleep quality was even worse for children with severe active AD (aOR, 1.68), and active AD plus asthma or allergic rhinitis (aOR 2.15). Sleep quality was significantly worse in children reporting mild AD (aOR, 1.40) or inactive AD (aOR, 1.41), compared with children without AD. Nighttime sleep duration was similar throughout childhood for children with and without AD.

“In addition to increased nighttime awakenings and difficulty falling asleep, we found that children with active atopic dermatitis were more likely to report nightmares and early morning awakenings, which has not been previously studied,” Ms. Ramirez and her associates said.

Total sleep duration was statistically shorter overall for children with AD, compared with those without AD, but the difference was not clinically significant, they noted.

The participants were from a longitudinal study in the United Kingdom in which pregnant women were recruited between 1990 and 1992. For those with children alive at 1 year, their children were followed for approximately 16 years. Sleep quality was assessed at six time points with four standardized questionnaires between ages 2 and 10 years, and sleep duration was assessed at eight time points between ages 2 and 16 years with standardized questionnaires.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including some missing data and patient attrition, as well as possible misclassification bias because of the use of parent and patient self-reports, and a possible lack of generalizability to other populations, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the need for developing clinical outcome measures to address sleep quality in children with AD, they said. “Additional work should investigate interventions to improve sleep quality and examine the association between atopic dermatitis treatment and children’s sleep.”

The study was funded primarily by a grant from the National Eczema Association. Ms. Ramirez disclosed a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two other investigators received grants, one from NIH and the other Wellcome Senior Clinical Fellowship in Science. One coauthor reported receiving multiple grants, as well as paid consulting for TARGETPharma, a company developing a prospective atopic dermatitis registry.

SOURCE: Ramirez FD al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025.

The itching associated with atopic dermatitis (AD) may interfere with children’s sleep, and sleep studies suggest that children with active disease are more restless at night, wrote Faustine D. Ramirez of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues. Their report is in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Acute and chronic sleep disturbances have been associated with a wide range of cognitive, mood, and behavioral impairments and have been linked to poor educational performance,” the researchers noted.

To determine the impact of active AD on children’s sleep, the researchers reviewed data from 13,988 children followed for a median of 11 years. Of these, 4,938 children met the definition for AD between age 2 and 16 years.

Overall, children with active AD were approximately 50% more likely to experience poor sleep quality than were those without AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.48). Sleep quality was even worse for children with severe active AD (aOR, 1.68), and active AD plus asthma or allergic rhinitis (aOR 2.15). Sleep quality was significantly worse in children reporting mild AD (aOR, 1.40) or inactive AD (aOR, 1.41), compared with children without AD. Nighttime sleep duration was similar throughout childhood for children with and without AD.

“In addition to increased nighttime awakenings and difficulty falling asleep, we found that children with active atopic dermatitis were more likely to report nightmares and early morning awakenings, which has not been previously studied,” Ms. Ramirez and her associates said.

Total sleep duration was statistically shorter overall for children with AD, compared with those without AD, but the difference was not clinically significant, they noted.

The participants were from a longitudinal study in the United Kingdom in which pregnant women were recruited between 1990 and 1992. For those with children alive at 1 year, their children were followed for approximately 16 years. Sleep quality was assessed at six time points with four standardized questionnaires between ages 2 and 10 years, and sleep duration was assessed at eight time points between ages 2 and 16 years with standardized questionnaires.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including some missing data and patient attrition, as well as possible misclassification bias because of the use of parent and patient self-reports, and a possible lack of generalizability to other populations, the researchers noted.

However, the results support the need for developing clinical outcome measures to address sleep quality in children with AD, they said. “Additional work should investigate interventions to improve sleep quality and examine the association between atopic dermatitis treatment and children’s sleep.”

The study was funded primarily by a grant from the National Eczema Association. Ms. Ramirez disclosed a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Two other investigators received grants, one from NIH and the other Wellcome Senior Clinical Fellowship in Science. One coauthor reported receiving multiple grants, as well as paid consulting for TARGETPharma, a company developing a prospective atopic dermatitis registry.

SOURCE: Ramirez FD al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Dermatologists name isobornyl acrylate contact allergen of the year

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – The American Contact Dermatitis Society has selected isobornyl acrylate the contact allergen of the year. It is an acrylic monomer used as an adhesive.

Among other applications, isobornyl acrylate is often used in medical devices. The selection was made based in part on multiple case reports of diabetes patients developing contact allergies to their diabetes devices, such as insulin pumps, explained Golara Honari, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, who presented the selection at the ACDS annual meeting.

The significance of this allergen is that testing through routine panels does not identify it, so clinician awareness is especially important, Dr. Honari noted in a video interview at the meeting.

Most of the reported contact allergen cases have been in patients with diabetes, but clinicians should think about other possible sources, such as acrylic nails, she said. As for treatment, clinicians and patients can consider alternative diabetes devices without isobornyl acrylate, she said.

In the future, close collaboration between clinicians and the medical device industry to develop appropriate labeling can help increase awareness of the potential for allergic reactions, she added.

Dr. Honari had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

AT ACDS 2019

Risk for Appendicitis, Cholecystitis, or Diverticulitis in Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

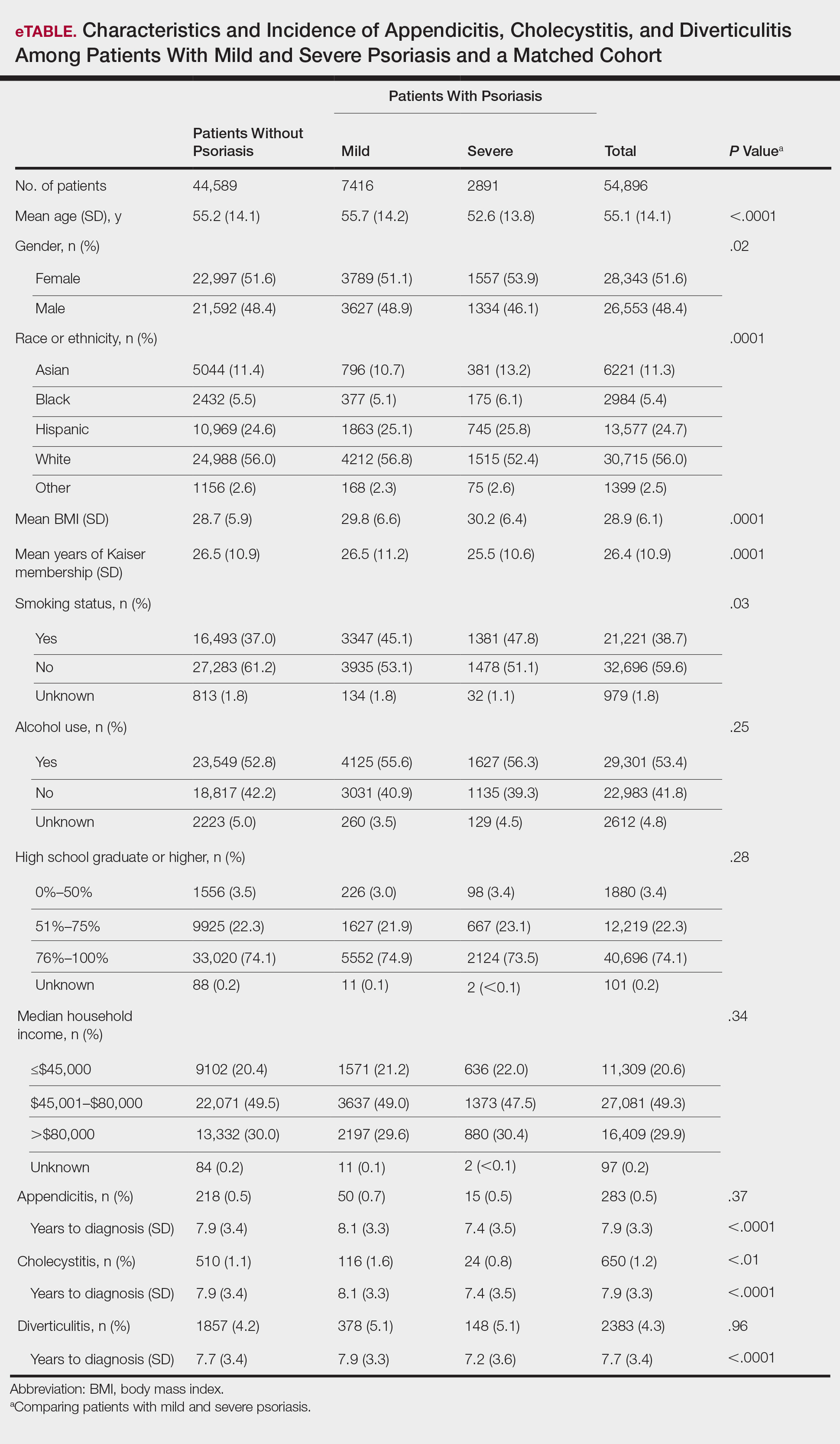

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

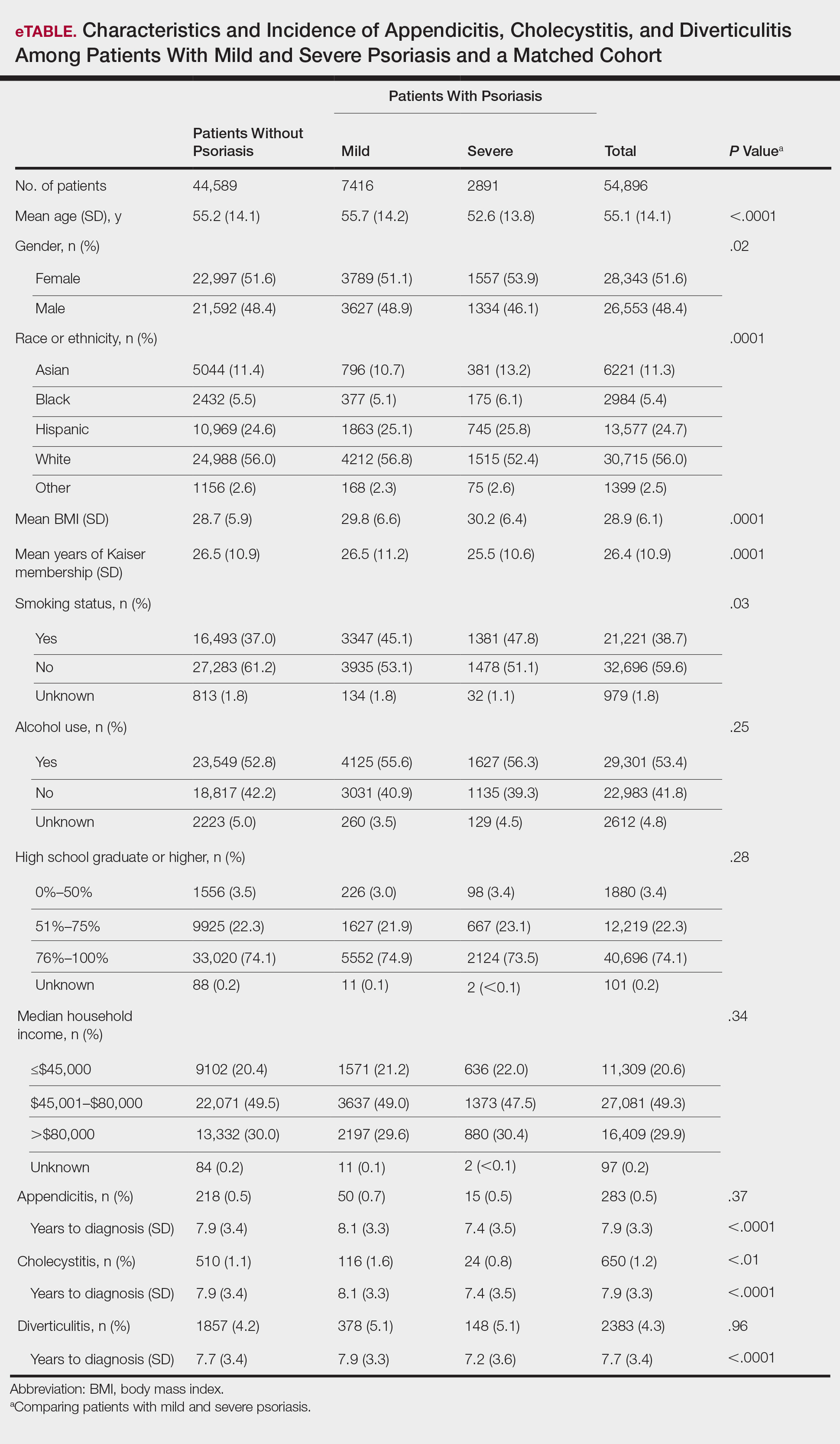

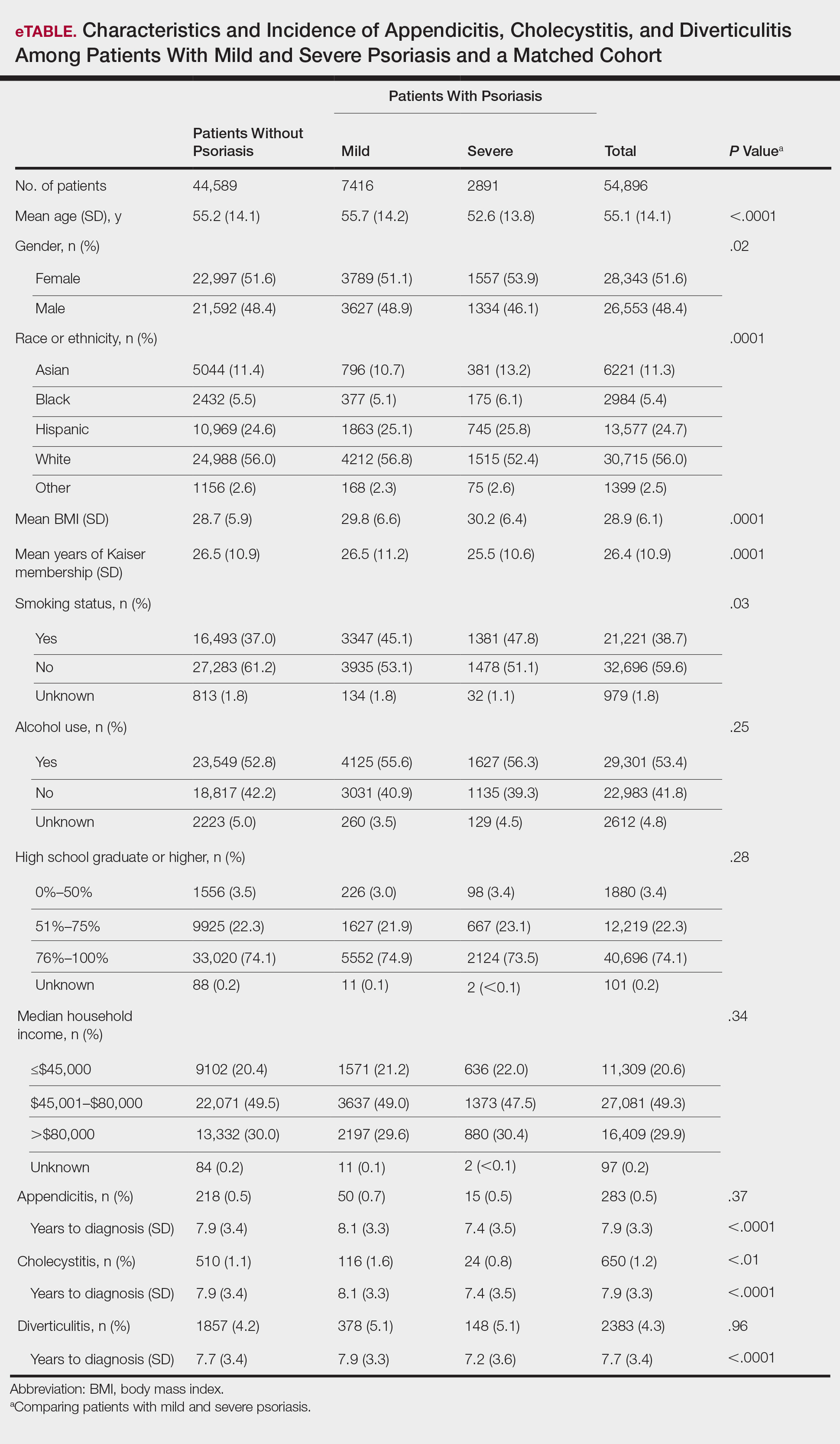

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

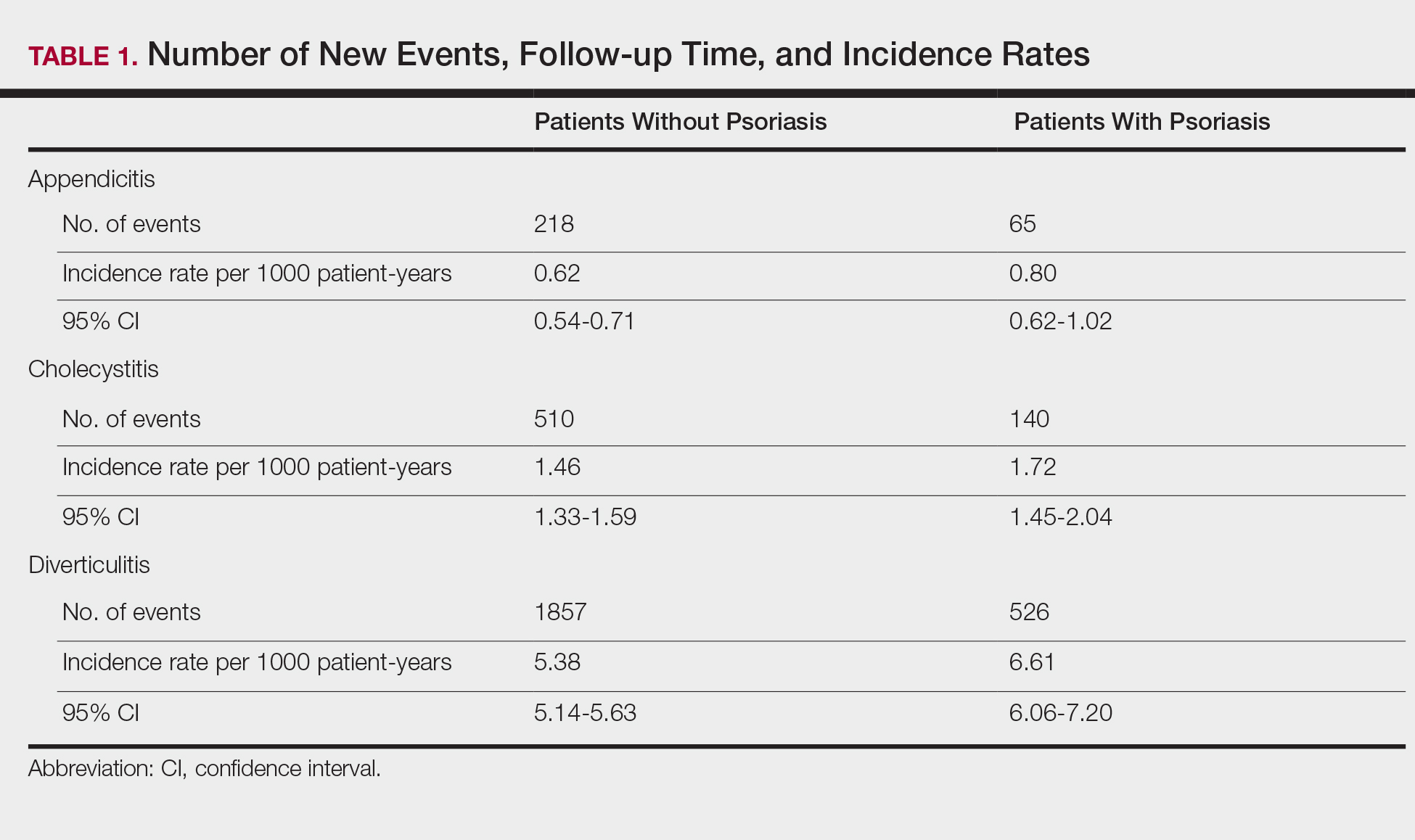

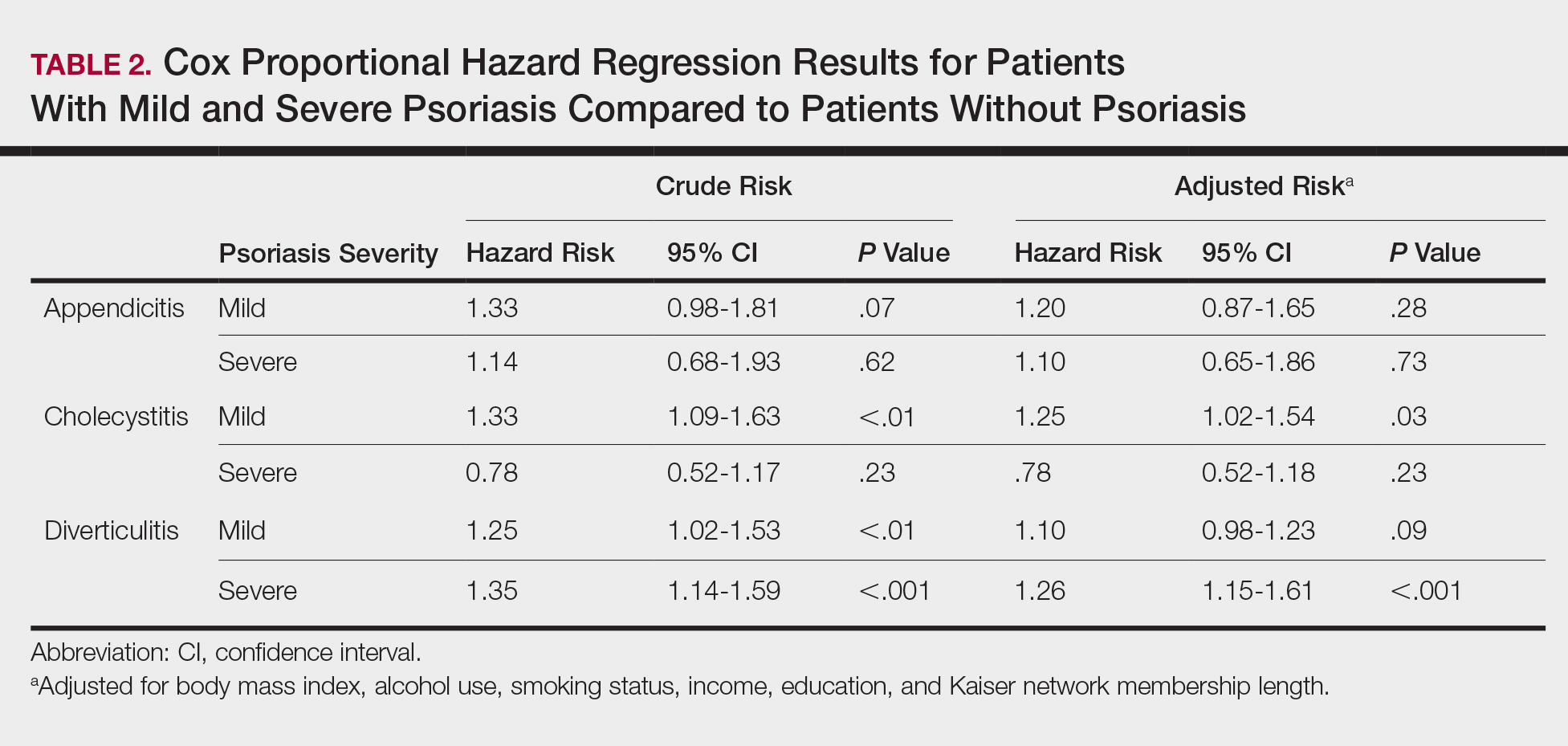

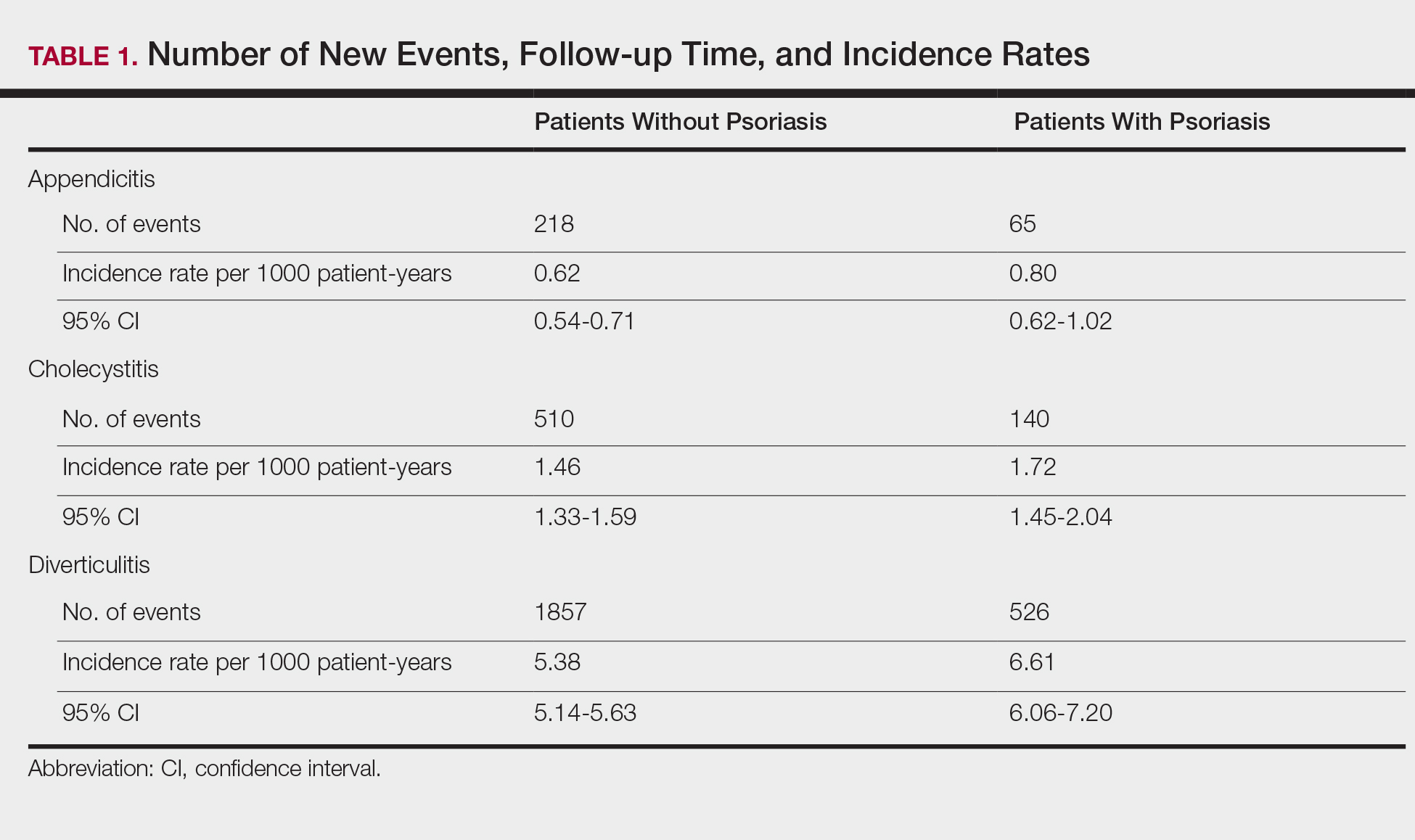

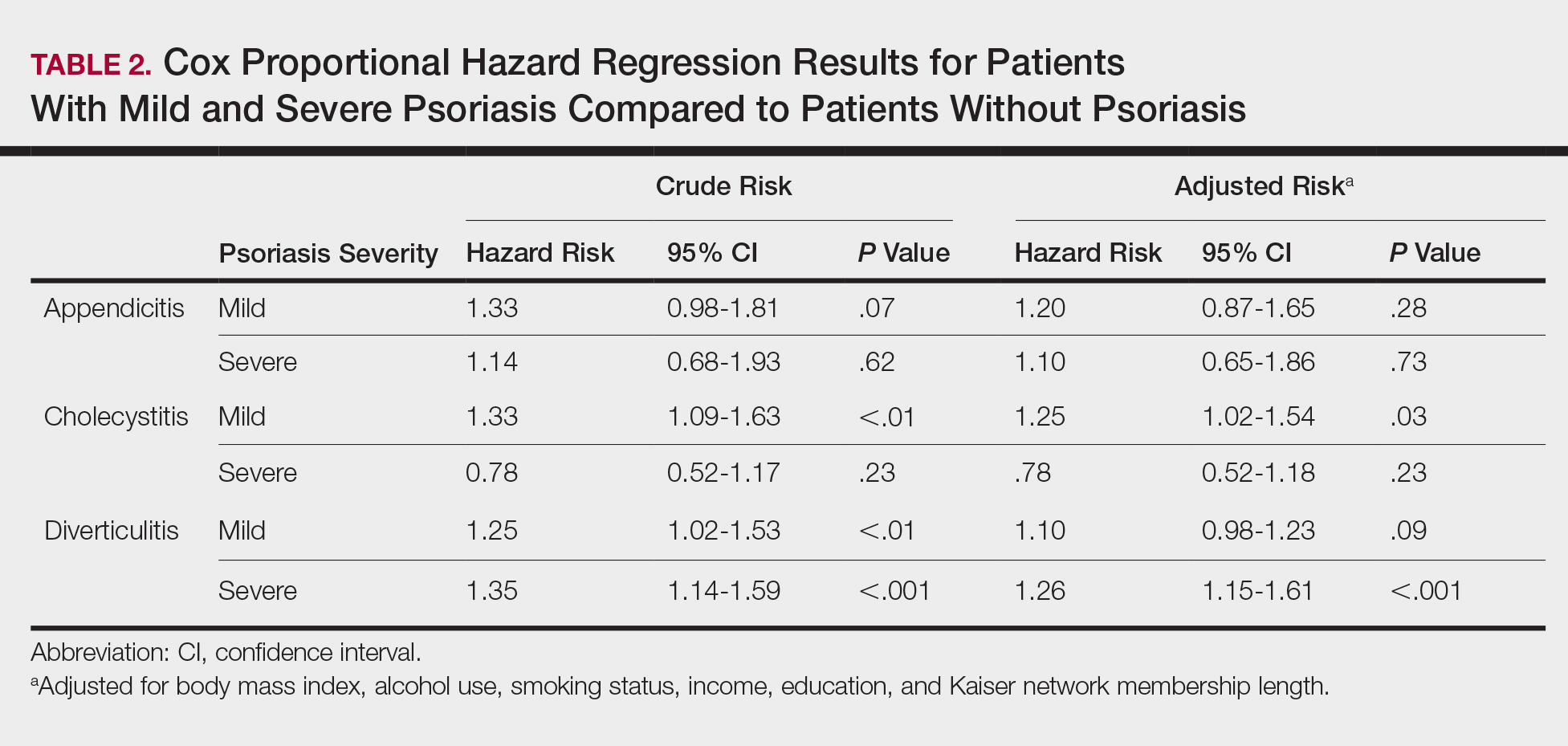

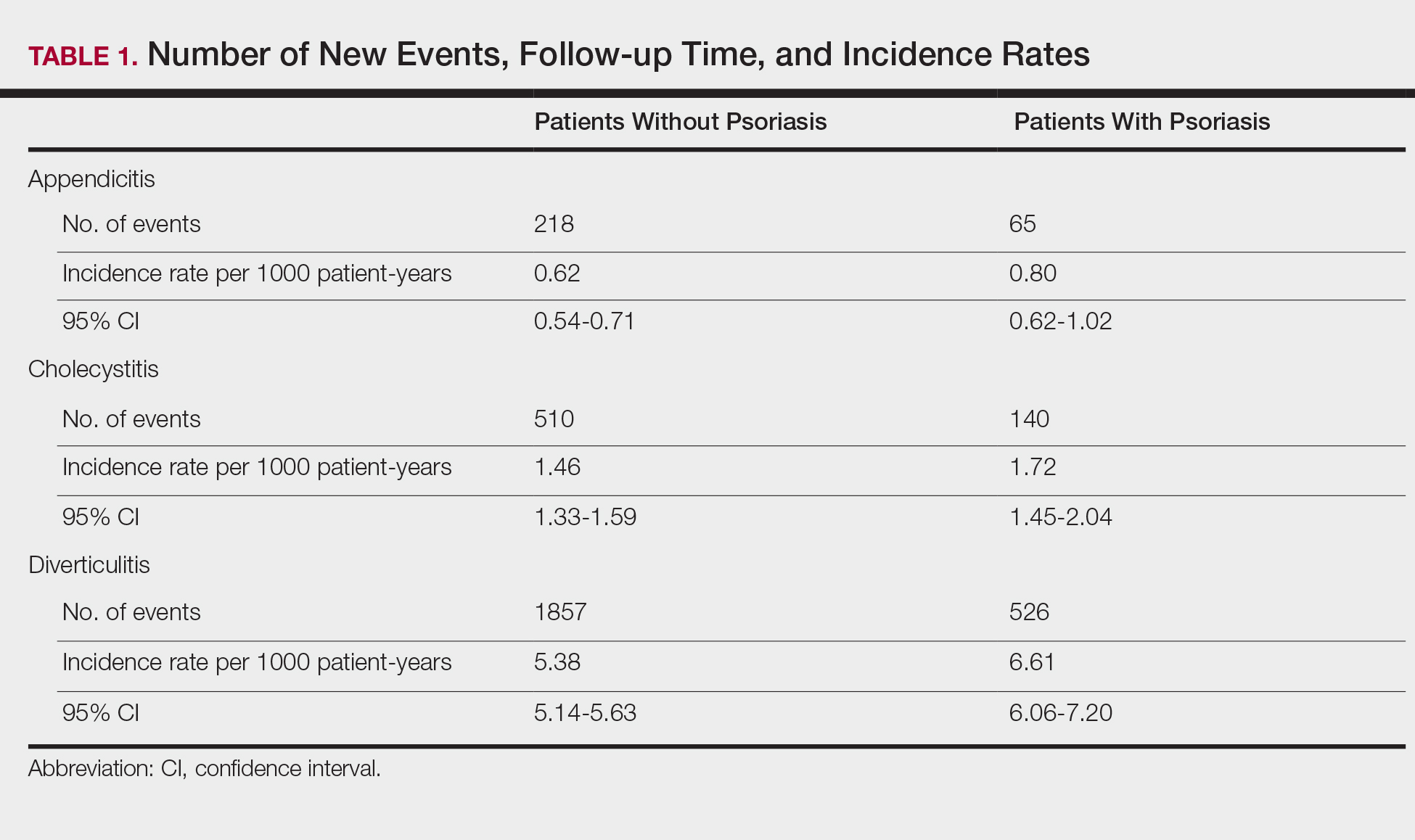

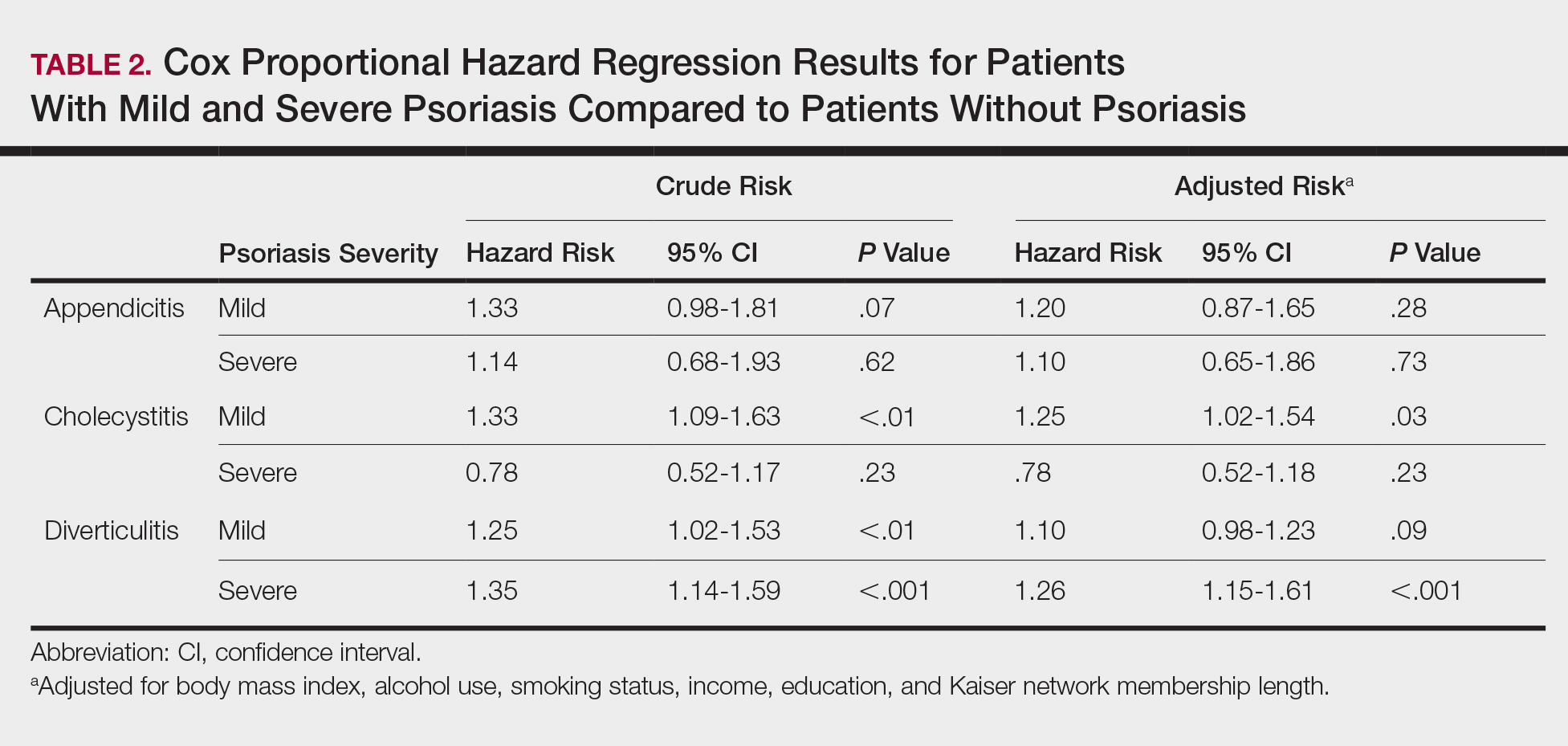

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

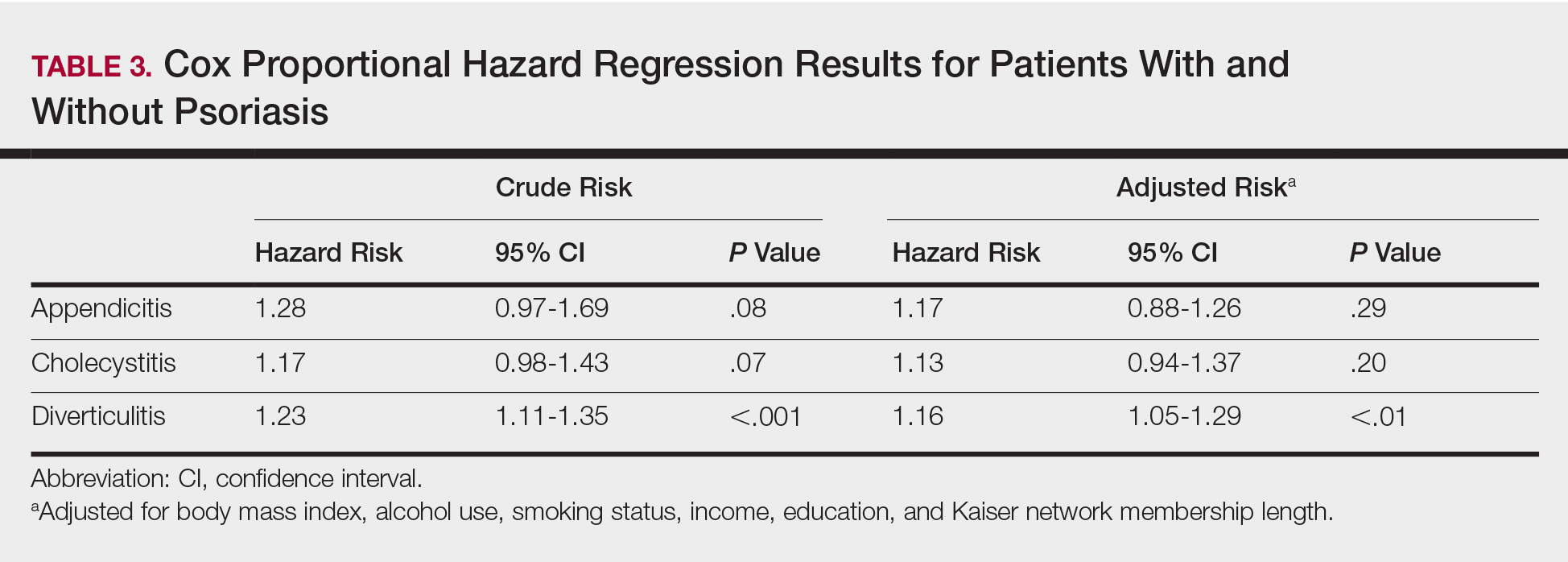

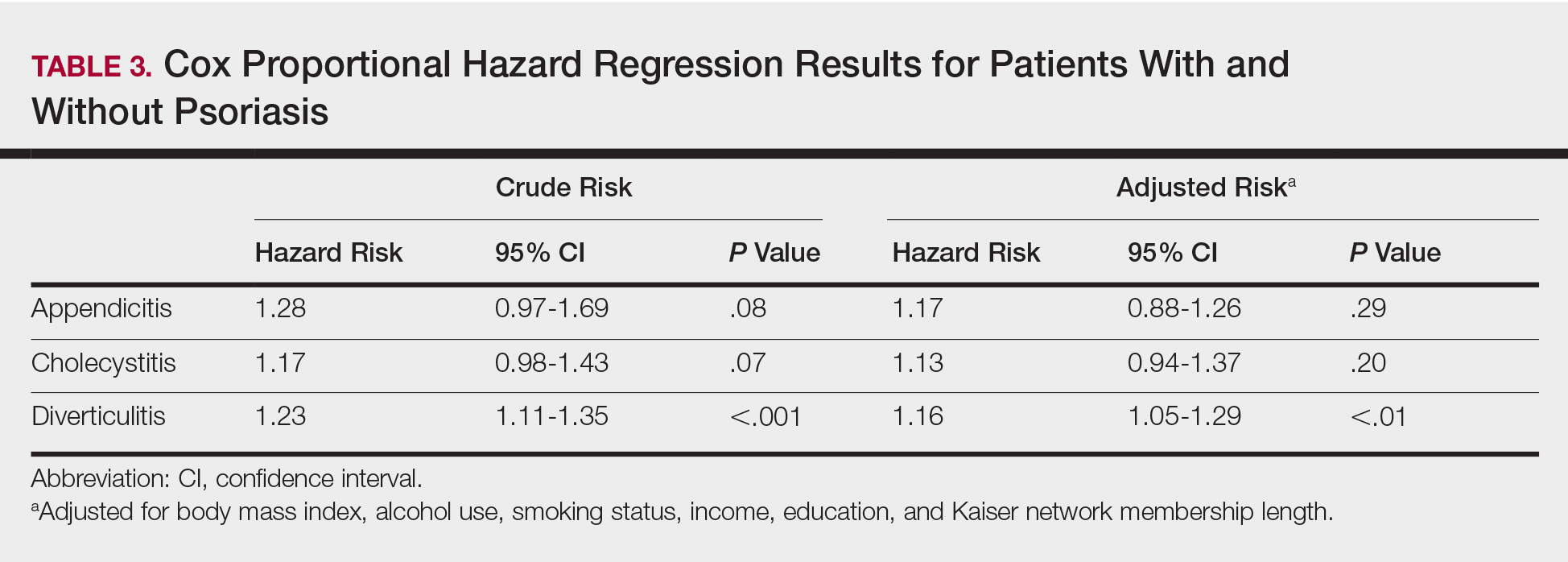

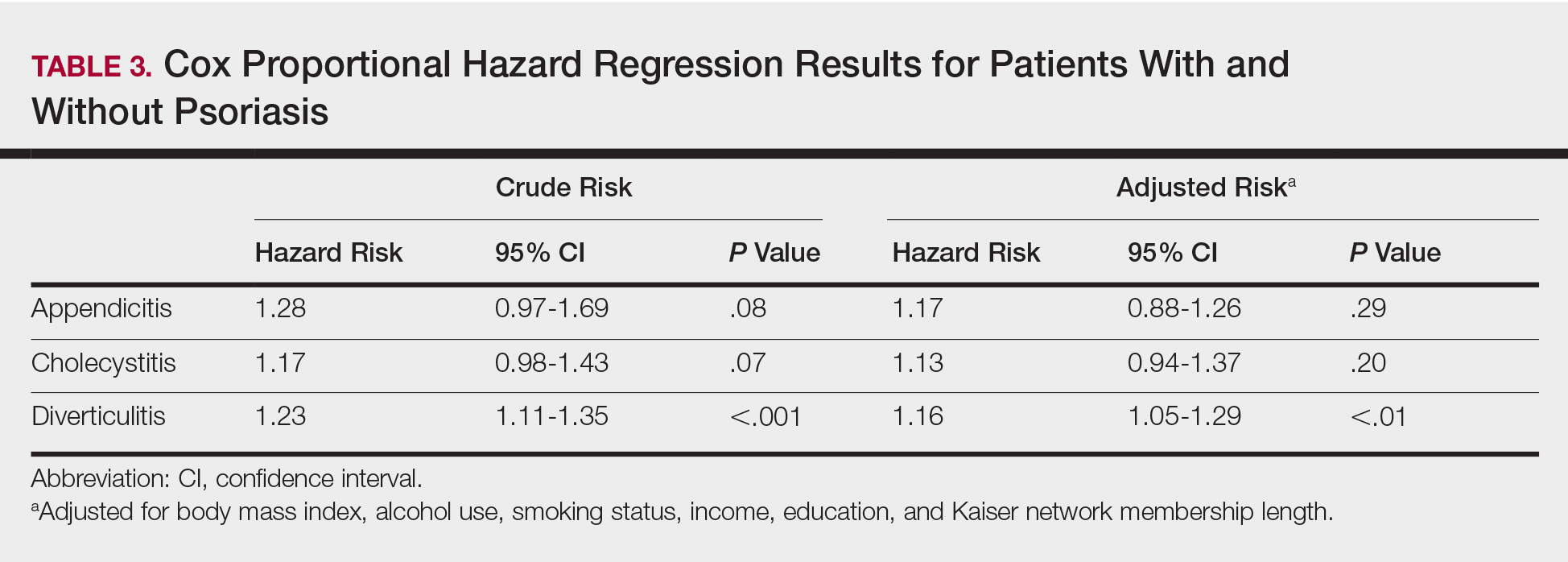

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Practice Points

- Patients with psoriasis may have elevated risk of diverticulitis compared to healthy patients. However, psoriasis patients do not appear to have increased risk of appendicitis or cholecystitis.

- Clinicians treating psoriasis patients should consider assessing for other risk factors of diverticulitis at regular intervals.

Click for Credit: Endometriosis surgery benefits; diabetes & aging; more

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Ez8mdu

Expires January 3, 2019

2. Cerebral small vessel disease progression linked to MCI in hypertensive patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ExDV7o

Expires January 4, 2019

3. Adult atopic dermatitis is fraught with dermatologic comorbidities

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vl7E9a

Expires January 11, 2019

4. Antidepressants tied to greater hip fracture incidence in older adults

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2GRfMeH

Expires January 4, 2019

5. Researchers exploring ways to mitigate aging’s impact on diabetes

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2tFxF7v

Expires January 8, 2019

Pediatric pruritus requires distinct approach to assessment and management

WASHINGTON – Suephy C. Chen, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Using special scales to measure itch in children and understanding that quality of life concerns may be different for children should also be kept in mind, said Dr. Chen, professor of dermatology at Emory University, Atlanta. Furthermore, several psychiatric comorbidities that have been associated with pediatric pruritus, such as ADHD and suicidal thoughts. Another consideration is that a child’s pruritus can have significant effects on his or her parents.

Measuring itch is challenging in children, who may have difficulty responding to visual analogue scales, verbal rating scales, and numerical rating scales. Dr. Chen and her colleagues developed the ItchyQuant scale as a self-report measure of itch severity (J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Jan;137[1]:57-61). It is a scale from 0 to 10 with cartoon illustrations depicting increasing itch severity, from no itch to the “worst itch imaginable.” Currently it is validated only in adults, but they are working towards getting it validated in children.

Another itch assessment scale for children, Itch Man, is available, but has only been studied in children who have survived burns.

The ItchyQOL scale measures the extent to which itch affects quality of life in adults. It examines the symptoms associated with itch, as well as its functional and emotional effects. But children’s concerns about quality of life are not the same as those of adults, so Dr. Chen and her colleagues used ItchyQOL as a basis for the “Tween ItchyQOL,” which is intended for children aged 8-17 years, and the “Kids ItchyQOL,” which is intended for children aged 6-7 years. The Tween ItchyQOL includes items (such as being made fun of) that are not in the ItchyQOL and eliminates items (such as working and spending money) that do not apply to children. The Kids ItchyQOL includes cartoons to help children understand the questions.

Dermatologists often use parents as proxies to measure their children’s itch, assuming that the latter’s responses might be unreliable. But when Dr. Chen and her colleagues administered the ItchyQuant to children with pruritus, parents, and their medical providers to evaluate the extent of agreement among assessors, they found that parents’ scores were higher than their children’s scores, although the difference was not significant.

Providers’ scores, however, were significantly lower than those of children and parents. All scores were in the moderate range. Dr. Chen and colleagues also found that, for each 1-point increase in the difference between children’s and parents’ responses, parents were 1.25 times less likely to have experience with chronic pruritus, outside of their children. This finding provides a gauge of how well a parent can serve as a proxy to characterize his or her child’s itch.