User login

Weekend Botox training: Shortcut to cash or risky business?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Patel: A friend recently joked with me and said, “I wish you were a dermatologist so you could hook me up with Botox and fillers.” Well, little does this friend know that I could be a certified cosmetic injector just after a weekend course. Botox parties, here I come?

I can’t blame any health care professional for having a side hustle. People are burned out, want to supplement their income, or scale back clinical hours. According to one Medscape survey, almost 40% of physicians do have some form of a side hustle, whether it is consulting, speaking engagements, being an expert witness, or moonlighting. I know plenty of doctors and nurses who have taken on Botox injecting as a way to make some extra cash.

Now, going back to me and smoothing out wrinkles. I’m a pediatric hospitalist. I’ve never injected an aesthetic product in anyone’s face. When it comes to sharp objects and faces, I’ve sewn lacerations and drained abscesses. In my world, when we talk about botulinum toxin, we’re usually talking about botulism or the therapeutic treatment of migraines and muscle spasms – pathology.

The National Laser Institute has a 2-day Botox and dermal filler training. “Our 2-day Botox and filler course will also teach you how to build a practice and capitalize on the enormous Botox and dermal filler market that exists in the United States.” That’s a lot to cover in 2 days. They even have lunch breaks.

Just from a quick search, I even found an online video course for $1,500. For an additional fee, you can have a live, hands-on component. There are so many trainings out there, including one that’s only 8 hours long, offered by Empire Medical. I also went and spoke with an employee at Empire Medical who told me that because I’m an MD, if I do the course, I can use my certificate and go directly to a manufacturer, buy Botox, and start injecting right away.

Now, is this training actually sufficient for me to go and get good results while minimizing adverse effects like brow ptosis, dry eyes, and asymmetry? I have no idea. According to a review from the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, it’s crucial to understand anatomic landmarks, muscle function, baseline asymmetry, potential migration of the toxin, and site-specific precautions.

Okay, that sounds really intimidating, but people still do it. I saw a Business Insider article about a hospitalist who took a 2-day Botox course and then, to her credit, she trained under supervision for an additional 6 months. She then started hosting Botox parties and each time was making $3,500 to upwards of $20,000.

Let’s do some quick mental math. If I were to go online and buy Botox for $3-$6 a unit and then charge patients $15 a unit, and then I consider that in areas like the forehead or in between the eyes – I read that could take 25-50 units – and I repeat this for multiple patients, I can make a few thousand dollars. Well, I may have to adjust my prices according to the market, obviously, because I did see some Groupons advertising $10 per unit.

Who can get in on some Botox cosmetic cash action? Well, physicians can right away. For other health care professionals, it depends on the state. For example, in California, dentists cannot get Botox solely for cosmetic purposes, whereas in Arizona, they can. Generally speaking, NPs and PAs require some type of physician oversight or supervision, but again, it depends on the state.

Oh, and fun fact: Connecticut outright banned Botox parties and said that Botox must be performed “in a medical spa or licensed health care facility and by a Connecticut-licensed health care provider within his or her scope of practice.”

It definitely worries me that someone could go online or go overseas, buy Botox, claim to be a health care professional, and literally commit fraud. I found stories out there such as a couple in San Jose who are giving out Botox from their home without a license. They got arrested. Also, a woman in Alabama who lied about being a licensed dermatologist and did the same, or another woman in Los Angeles who got arrested after selling counterfeit Botox to undercover law enforcement. Surely, there are plenty more cases out there like this.

I asked Dr. Jacqueline Watchmaker, a board-certified dermatologist at U.S. Dermatology Partners in Arizona who has an expertise in cosmetic procedures, what she thought about the booming med spa industry and what, if any, regulatory changes she wanted to see.

Jacqueline Watchmaker, MD: I do think the fact that people can just go to a 1- or 2-day injection course and inject filler and Botox is concerning. I think the lack of regulation surrounding this topic is also very concerning.

There’s so much that goes into being a skilled injector. It’s an intricate knowledge of facial anatomy, which takes weeks, if not months, to really master. There’s actually injection technique, which can be very complex depending on the part of the face that you’re injecting. Even more important, it’s how to prevent complications, but also how to deal with complications if they do occur. There’s no way that these weekend injection courses are able to cover those topics in a thorough and satisfactory manner.

I see complications from med spas all the time, and I think it’s people going to injectors who are not skilled. They don’t know their anatomy, they don’t know the appropriate filler to use, and then heaven forbid there is a complication, they don’t know how to manage the complication – and then those patients get sent to me.

I think patients sometimes forget that these cosmetic procedures are true medical procedures. You need sterile technique. Again, you need to know the anatomy. It can look easy on social media, but there’s a large amount of thought behind it. I think there needs to be more regulation around this topic.

Dr. Patel: In one study, out of 400 people who received a cosmetic procedure, 50 reported an adverse event, such as discoloration or burns, and these adverse events were more likely to occur if a nonphysician was doing the procedure. Granted, this was a small study. You can’t make a generalization out of it, but this does add to the argument that there needs to be more regulation and oversight.

Let’s be real. The cosmetic injection side hustle is alive and well, but I’m good. I’m not going there. Maybe there should be some more quality control. At Botox parties, do people even ask if their injectors are certified or where they bought their vials?

You might be thinking that this isn’t a big deal because it’s just Botox. Let me ask you all a question: If you or your family member were going to go get Botox or another cosmetic injection, would it still not be a big deal?

Dr. Patel is a pediatric hospitalist, television producer, media contributor, and digital health enthusiast. He splits his time between New York City and San Francisco, as he is on faculty at Columbia University/Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. He reported conflicts of interest with Medumo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Patel: A friend recently joked with me and said, “I wish you were a dermatologist so you could hook me up with Botox and fillers.” Well, little does this friend know that I could be a certified cosmetic injector just after a weekend course. Botox parties, here I come?

I can’t blame any health care professional for having a side hustle. People are burned out, want to supplement their income, or scale back clinical hours. According to one Medscape survey, almost 40% of physicians do have some form of a side hustle, whether it is consulting, speaking engagements, being an expert witness, or moonlighting. I know plenty of doctors and nurses who have taken on Botox injecting as a way to make some extra cash.

Now, going back to me and smoothing out wrinkles. I’m a pediatric hospitalist. I’ve never injected an aesthetic product in anyone’s face. When it comes to sharp objects and faces, I’ve sewn lacerations and drained abscesses. In my world, when we talk about botulinum toxin, we’re usually talking about botulism or the therapeutic treatment of migraines and muscle spasms – pathology.

The National Laser Institute has a 2-day Botox and dermal filler training. “Our 2-day Botox and filler course will also teach you how to build a practice and capitalize on the enormous Botox and dermal filler market that exists in the United States.” That’s a lot to cover in 2 days. They even have lunch breaks.

Just from a quick search, I even found an online video course for $1,500. For an additional fee, you can have a live, hands-on component. There are so many trainings out there, including one that’s only 8 hours long, offered by Empire Medical. I also went and spoke with an employee at Empire Medical who told me that because I’m an MD, if I do the course, I can use my certificate and go directly to a manufacturer, buy Botox, and start injecting right away.

Now, is this training actually sufficient for me to go and get good results while minimizing adverse effects like brow ptosis, dry eyes, and asymmetry? I have no idea. According to a review from the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, it’s crucial to understand anatomic landmarks, muscle function, baseline asymmetry, potential migration of the toxin, and site-specific precautions.

Okay, that sounds really intimidating, but people still do it. I saw a Business Insider article about a hospitalist who took a 2-day Botox course and then, to her credit, she trained under supervision for an additional 6 months. She then started hosting Botox parties and each time was making $3,500 to upwards of $20,000.

Let’s do some quick mental math. If I were to go online and buy Botox for $3-$6 a unit and then charge patients $15 a unit, and then I consider that in areas like the forehead or in between the eyes – I read that could take 25-50 units – and I repeat this for multiple patients, I can make a few thousand dollars. Well, I may have to adjust my prices according to the market, obviously, because I did see some Groupons advertising $10 per unit.

Who can get in on some Botox cosmetic cash action? Well, physicians can right away. For other health care professionals, it depends on the state. For example, in California, dentists cannot get Botox solely for cosmetic purposes, whereas in Arizona, they can. Generally speaking, NPs and PAs require some type of physician oversight or supervision, but again, it depends on the state.

Oh, and fun fact: Connecticut outright banned Botox parties and said that Botox must be performed “in a medical spa or licensed health care facility and by a Connecticut-licensed health care provider within his or her scope of practice.”

It definitely worries me that someone could go online or go overseas, buy Botox, claim to be a health care professional, and literally commit fraud. I found stories out there such as a couple in San Jose who are giving out Botox from their home without a license. They got arrested. Also, a woman in Alabama who lied about being a licensed dermatologist and did the same, or another woman in Los Angeles who got arrested after selling counterfeit Botox to undercover law enforcement. Surely, there are plenty more cases out there like this.

I asked Dr. Jacqueline Watchmaker, a board-certified dermatologist at U.S. Dermatology Partners in Arizona who has an expertise in cosmetic procedures, what she thought about the booming med spa industry and what, if any, regulatory changes she wanted to see.

Jacqueline Watchmaker, MD: I do think the fact that people can just go to a 1- or 2-day injection course and inject filler and Botox is concerning. I think the lack of regulation surrounding this topic is also very concerning.

There’s so much that goes into being a skilled injector. It’s an intricate knowledge of facial anatomy, which takes weeks, if not months, to really master. There’s actually injection technique, which can be very complex depending on the part of the face that you’re injecting. Even more important, it’s how to prevent complications, but also how to deal with complications if they do occur. There’s no way that these weekend injection courses are able to cover those topics in a thorough and satisfactory manner.

I see complications from med spas all the time, and I think it’s people going to injectors who are not skilled. They don’t know their anatomy, they don’t know the appropriate filler to use, and then heaven forbid there is a complication, they don’t know how to manage the complication – and then those patients get sent to me.

I think patients sometimes forget that these cosmetic procedures are true medical procedures. You need sterile technique. Again, you need to know the anatomy. It can look easy on social media, but there’s a large amount of thought behind it. I think there needs to be more regulation around this topic.

Dr. Patel: In one study, out of 400 people who received a cosmetic procedure, 50 reported an adverse event, such as discoloration or burns, and these adverse events were more likely to occur if a nonphysician was doing the procedure. Granted, this was a small study. You can’t make a generalization out of it, but this does add to the argument that there needs to be more regulation and oversight.

Let’s be real. The cosmetic injection side hustle is alive and well, but I’m good. I’m not going there. Maybe there should be some more quality control. At Botox parties, do people even ask if their injectors are certified or where they bought their vials?

You might be thinking that this isn’t a big deal because it’s just Botox. Let me ask you all a question: If you or your family member were going to go get Botox or another cosmetic injection, would it still not be a big deal?

Dr. Patel is a pediatric hospitalist, television producer, media contributor, and digital health enthusiast. He splits his time between New York City and San Francisco, as he is on faculty at Columbia University/Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. He reported conflicts of interest with Medumo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Patel: A friend recently joked with me and said, “I wish you were a dermatologist so you could hook me up with Botox and fillers.” Well, little does this friend know that I could be a certified cosmetic injector just after a weekend course. Botox parties, here I come?

I can’t blame any health care professional for having a side hustle. People are burned out, want to supplement their income, or scale back clinical hours. According to one Medscape survey, almost 40% of physicians do have some form of a side hustle, whether it is consulting, speaking engagements, being an expert witness, or moonlighting. I know plenty of doctors and nurses who have taken on Botox injecting as a way to make some extra cash.

Now, going back to me and smoothing out wrinkles. I’m a pediatric hospitalist. I’ve never injected an aesthetic product in anyone’s face. When it comes to sharp objects and faces, I’ve sewn lacerations and drained abscesses. In my world, when we talk about botulinum toxin, we’re usually talking about botulism or the therapeutic treatment of migraines and muscle spasms – pathology.

The National Laser Institute has a 2-day Botox and dermal filler training. “Our 2-day Botox and filler course will also teach you how to build a practice and capitalize on the enormous Botox and dermal filler market that exists in the United States.” That’s a lot to cover in 2 days. They even have lunch breaks.

Just from a quick search, I even found an online video course for $1,500. For an additional fee, you can have a live, hands-on component. There are so many trainings out there, including one that’s only 8 hours long, offered by Empire Medical. I also went and spoke with an employee at Empire Medical who told me that because I’m an MD, if I do the course, I can use my certificate and go directly to a manufacturer, buy Botox, and start injecting right away.

Now, is this training actually sufficient for me to go and get good results while minimizing adverse effects like brow ptosis, dry eyes, and asymmetry? I have no idea. According to a review from the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, it’s crucial to understand anatomic landmarks, muscle function, baseline asymmetry, potential migration of the toxin, and site-specific precautions.

Okay, that sounds really intimidating, but people still do it. I saw a Business Insider article about a hospitalist who took a 2-day Botox course and then, to her credit, she trained under supervision for an additional 6 months. She then started hosting Botox parties and each time was making $3,500 to upwards of $20,000.

Let’s do some quick mental math. If I were to go online and buy Botox for $3-$6 a unit and then charge patients $15 a unit, and then I consider that in areas like the forehead or in between the eyes – I read that could take 25-50 units – and I repeat this for multiple patients, I can make a few thousand dollars. Well, I may have to adjust my prices according to the market, obviously, because I did see some Groupons advertising $10 per unit.

Who can get in on some Botox cosmetic cash action? Well, physicians can right away. For other health care professionals, it depends on the state. For example, in California, dentists cannot get Botox solely for cosmetic purposes, whereas in Arizona, they can. Generally speaking, NPs and PAs require some type of physician oversight or supervision, but again, it depends on the state.

Oh, and fun fact: Connecticut outright banned Botox parties and said that Botox must be performed “in a medical spa or licensed health care facility and by a Connecticut-licensed health care provider within his or her scope of practice.”

It definitely worries me that someone could go online or go overseas, buy Botox, claim to be a health care professional, and literally commit fraud. I found stories out there such as a couple in San Jose who are giving out Botox from their home without a license. They got arrested. Also, a woman in Alabama who lied about being a licensed dermatologist and did the same, or another woman in Los Angeles who got arrested after selling counterfeit Botox to undercover law enforcement. Surely, there are plenty more cases out there like this.

I asked Dr. Jacqueline Watchmaker, a board-certified dermatologist at U.S. Dermatology Partners in Arizona who has an expertise in cosmetic procedures, what she thought about the booming med spa industry and what, if any, regulatory changes she wanted to see.

Jacqueline Watchmaker, MD: I do think the fact that people can just go to a 1- or 2-day injection course and inject filler and Botox is concerning. I think the lack of regulation surrounding this topic is also very concerning.

There’s so much that goes into being a skilled injector. It’s an intricate knowledge of facial anatomy, which takes weeks, if not months, to really master. There’s actually injection technique, which can be very complex depending on the part of the face that you’re injecting. Even more important, it’s how to prevent complications, but also how to deal with complications if they do occur. There’s no way that these weekend injection courses are able to cover those topics in a thorough and satisfactory manner.

I see complications from med spas all the time, and I think it’s people going to injectors who are not skilled. They don’t know their anatomy, they don’t know the appropriate filler to use, and then heaven forbid there is a complication, they don’t know how to manage the complication – and then those patients get sent to me.

I think patients sometimes forget that these cosmetic procedures are true medical procedures. You need sterile technique. Again, you need to know the anatomy. It can look easy on social media, but there’s a large amount of thought behind it. I think there needs to be more regulation around this topic.

Dr. Patel: In one study, out of 400 people who received a cosmetic procedure, 50 reported an adverse event, such as discoloration or burns, and these adverse events were more likely to occur if a nonphysician was doing the procedure. Granted, this was a small study. You can’t make a generalization out of it, but this does add to the argument that there needs to be more regulation and oversight.

Let’s be real. The cosmetic injection side hustle is alive and well, but I’m good. I’m not going there. Maybe there should be some more quality control. At Botox parties, do people even ask if their injectors are certified or where they bought their vials?

You might be thinking that this isn’t a big deal because it’s just Botox. Let me ask you all a question: If you or your family member were going to go get Botox or another cosmetic injection, would it still not be a big deal?

Dr. Patel is a pediatric hospitalist, television producer, media contributor, and digital health enthusiast. He splits his time between New York City and San Francisco, as he is on faculty at Columbia University/Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. He reported conflicts of interest with Medumo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Free teledermatology clinic helps underserved patients initiate AD care

A in other underserved areas in the United States.

Washington, D.C., has “staggering health disparities that are among the largest in the country,” and Ward 8 and surrounding areas in the southeastern part of the city are “dermatology deserts,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who started the program in 2021 with a pilot project. Dr. Friedman spoke about the project, which has since been expanded to include alopecia areata, at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis conference in April and in an interview after the meeting.

Patients who attend the clinics – held at the Temple of Praise Church in a residential area of Ward 8, a predominantly Black community with a 30% poverty rate – are entered into the GW Medical Faculty Associates medical records system and educated on telemedicine best practices (such as not having light behind them during a session) and how to use telemedicine with their own device.

Those with AD who participate learn about the condition through an image-rich poster showing how it appears in various skin tones, handouts, National Eczema Association films, and discussion with medical students who staff the clinics under Dr. Friedman’s on-site supervision. Participants with alopecia areata similarly can view a poster and converse about the condition.

Patients then have a free 20-minute telehealth visit with a GWU dermatology resident in a private room, and a medical student volunteer nearby to assist with the technology if needed. They leave with a treatment plan, which often includes prescriptions, and a follow-up telemedicine appointment.

The program “is meant to be a stepping point for initiating care ... to set someone up for success for recurrent telehealth visits in the future” and for treatment before symptoms become too severe, Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “We want to demystify telemedicine and educate on the disease state and dispel myths ... so the patient understands why it’s happening” and how it can be treated.

The pilot project, funded with a grant from Pfizer, involved five 2-hour clinics held on Mondays from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m., that together served almost 50 adult and pediatric patients. Grants from Pfizer and Eli Lilly enabled additional clinics in the spring of 2023 and into the summer. And in June, GWU and Pfizer announced a $1 million national grant program focused on broad implementation of what they’ve coined the “Teledermatology Help Desk Clinic” model.

Practices or organizations that secure grants will utilize GWU’s experience and meet with an advisory council of experts in dermatology telemedicine and community advocacy. Having a “long-term plan” and commitment to sustainability is an important element of the model, said Dr. Friedman, who is chairing the grant program.

Patients deem clinic ‘extremely’ helpful

As one of the most prevalent skin disorders – and one with a documented history of elevated risk for specific populations – AD was a good starting point for the teledermatology clinic program. Patients who identify as Black have a higher incidence and prevalence of AD than those who identify as White and Hispanic, and they tend to have more severe disease. Yet they account for fewer visits to dermatologists for AD.

One cross-sectional study of about 3,500 adults in the United States with AD documented that racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities reduce outpatient utilization of AD care and increase urgent care and hospital utilization. And in a longitudinal cohort study of children in the United States with AD, Black children with poorly controlled AD were significantly less likely than White children to see a dermatologist.

Like other programs, the GWU department of dermatology had pivoted to telehealth in 2020, and a published survey of patients who attended telehealth appointments during the early part of the pandemic showed that it was generally well liked – and not only for social distancing, but for time efficiency and because transportation was not needed. Only 10% of the 168 patients who completed the survey (out of 894 asked) reported they were unlikely to undertake another telehealth visit. For 10%, eczema was the reason for the visit.

However, only 1% of the survey respondents were from Ward 8, which “begged the question, did those who really need access know this was an option?” Dr. Friedman said at the RAD meeting. He wondered whether there was not only a dermatology desert in Ward 8, but a “technology desert” as well.

Findings from a patient satisfaction survey taken at the end of the pilot program are encouraging, Dr. Friedman said. While data on follow-up visits has not been collected yet, “what I do now have a sense of” is that “the entry point [afforded by the clinics] changed the course in terms of patients’ understanding of the disease and how they feel about its management.”

About 94% of survey respondents indicated the clinic was “extremely” helpful and the remainder said it was “very” helpful; 90% said telehealth significantly changed how they will manage their condition; and 97% said it is “extremely” important to continue the clinics. The majority of patients – 70% – indicated they did not have a dermatologist.

Education about AD at the clinics covers moisturizers/emollients, bathing habits, soaps and detergents, trigger avoidance, and the role of stress and environmental factors in disease exacerbation. Trade samples of moisturizers, mild cleansers, and other products have increasingly been available.

For prescriptions of topical steroids and other commonly prescribed medications, Dr. Friedman and associates combed GoodRx for coupons and surveyed local pharmacies for self-pay pricing to identify least expensive options. Patients with AD who were deemed likely candidates for more advanced therapies in the future were educated about these possibilities.

Alopecia areata

The addition of alopecia areata drew patients with other forms of hair loss as well, but “we weren’t going to turn anyone away who did not have that specific autoimmune form of hair loss,” Dr. Friedman said. Depending on the diagnosis, prescriptions were written for minoxidil and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

Important for follow-up is GWU’s acceptance of Medicaid and the availability of both a sliding scale for self-pay and services that assist patients in registering for Medicaid and, if eligible, other insurance plans.

Building partnerships, earning trust

Establishment of the teledermatology clinic program took legwork and relationship building. “You can’t just show up. That’s not enough,” said Dr. Friedman, who also directs the dermatology residency program at GWU. “You have to show through action and through investment of time and energy that you are legitimate, that you’re really there for the long haul.”

Dr. Friedman had assistance from the Rodham Institute, which was established at GWU (and until recently was housed there) and has a history of engagement with local stakeholders such as community centers, church leadership, politicians, and others in the Washington area. He was put in touch with Bishop Deborah Webb at the Temple of Praise Church, a community pillar in Ward 8, and from there “it was a courtship,” he said, with trust to be built and logistics to be worked out. (Budgets for the clinics, he noted, have included compensation to the church and gift cards for church volunteers who are present at the clinics.)

In the meantime, medical student volunteers from GWU, Howard University, and Georgetown University were trained in telemedicine and attended a “boot camp” on AD “so they’d be able to talk with anyone about it,” Dr. Friedman said.

Advertising “was a learning experience,” he said, and was ultimately multipronged, involving church service announcements, flyers, and, most importantly, Facebook and Instagram advertisements. (People were asked to call a dedicated phone line to schedule an appointment and were invited to register in the GW Medical Faculty Associates records system, though walk-ins to the clinics were still welcomed.)

In a comment, Misty Eleryan, MD, MS, a Mohs micrographic surgeon and dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif., said dermatology deserts are often found in rural areas and/or areas “with a higher population of marginalized communities, such as Black, Brown, or poorer individuals” – communities that tend to rely on care from urgent care or ED physicians who are unaware of how skin conditions present on darker skin tones.

Programs that educate patients about various presentations of skin conditions are helpful not only for the patients themselves, but could also enable them to help friends, family members, and colleagues, said Dr. Eleryan, who did her residency training at GWU.

“Access,” she noted, is more than just physical access to a person, place, or thing. Referring to a “five A’s” framework described several decades ago, Dr. Eleryan said access to care is characterized by affordability, availability (extent to which the physician has the requisite resources, such as personnel and technology, to meet the patient’s needs), accessibility (geographic), accommodation (extent to which the physician can meet the patient’s constraints and preferences – such as hours of operation, how communications are handled, ability to receive care without prior appointments), and acceptability (extent to which the patient is comfortable with the “more immutable characteristics” of the physician and vice versa).

The GWU program, she said, “is a great start.”

Dr. Friedman said he’s fully invested. There has long been a perception, “rightfully so, that underserved communities are overlooked especially by large institutions. One attendee told me she never expected in her lifetime to see something like this clinic and someone who looked like me caring about her community. ... It certainly says a great deal about the work we need to put in to repair longstanding injury.”

Dr. Friedman disclosed that, in addition to being a recipient of grants from Pfizer and Lilly, he is a speaker for Lilly. Dr. Eleryan said she has no relevant disclosures.

A in other underserved areas in the United States.

Washington, D.C., has “staggering health disparities that are among the largest in the country,” and Ward 8 and surrounding areas in the southeastern part of the city are “dermatology deserts,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who started the program in 2021 with a pilot project. Dr. Friedman spoke about the project, which has since been expanded to include alopecia areata, at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis conference in April and in an interview after the meeting.

Patients who attend the clinics – held at the Temple of Praise Church in a residential area of Ward 8, a predominantly Black community with a 30% poverty rate – are entered into the GW Medical Faculty Associates medical records system and educated on telemedicine best practices (such as not having light behind them during a session) and how to use telemedicine with their own device.

Those with AD who participate learn about the condition through an image-rich poster showing how it appears in various skin tones, handouts, National Eczema Association films, and discussion with medical students who staff the clinics under Dr. Friedman’s on-site supervision. Participants with alopecia areata similarly can view a poster and converse about the condition.

Patients then have a free 20-minute telehealth visit with a GWU dermatology resident in a private room, and a medical student volunteer nearby to assist with the technology if needed. They leave with a treatment plan, which often includes prescriptions, and a follow-up telemedicine appointment.

The program “is meant to be a stepping point for initiating care ... to set someone up for success for recurrent telehealth visits in the future” and for treatment before symptoms become too severe, Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “We want to demystify telemedicine and educate on the disease state and dispel myths ... so the patient understands why it’s happening” and how it can be treated.

The pilot project, funded with a grant from Pfizer, involved five 2-hour clinics held on Mondays from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m., that together served almost 50 adult and pediatric patients. Grants from Pfizer and Eli Lilly enabled additional clinics in the spring of 2023 and into the summer. And in June, GWU and Pfizer announced a $1 million national grant program focused on broad implementation of what they’ve coined the “Teledermatology Help Desk Clinic” model.

Practices or organizations that secure grants will utilize GWU’s experience and meet with an advisory council of experts in dermatology telemedicine and community advocacy. Having a “long-term plan” and commitment to sustainability is an important element of the model, said Dr. Friedman, who is chairing the grant program.

Patients deem clinic ‘extremely’ helpful

As one of the most prevalent skin disorders – and one with a documented history of elevated risk for specific populations – AD was a good starting point for the teledermatology clinic program. Patients who identify as Black have a higher incidence and prevalence of AD than those who identify as White and Hispanic, and they tend to have more severe disease. Yet they account for fewer visits to dermatologists for AD.

One cross-sectional study of about 3,500 adults in the United States with AD documented that racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities reduce outpatient utilization of AD care and increase urgent care and hospital utilization. And in a longitudinal cohort study of children in the United States with AD, Black children with poorly controlled AD were significantly less likely than White children to see a dermatologist.

Like other programs, the GWU department of dermatology had pivoted to telehealth in 2020, and a published survey of patients who attended telehealth appointments during the early part of the pandemic showed that it was generally well liked – and not only for social distancing, but for time efficiency and because transportation was not needed. Only 10% of the 168 patients who completed the survey (out of 894 asked) reported they were unlikely to undertake another telehealth visit. For 10%, eczema was the reason for the visit.

However, only 1% of the survey respondents were from Ward 8, which “begged the question, did those who really need access know this was an option?” Dr. Friedman said at the RAD meeting. He wondered whether there was not only a dermatology desert in Ward 8, but a “technology desert” as well.

Findings from a patient satisfaction survey taken at the end of the pilot program are encouraging, Dr. Friedman said. While data on follow-up visits has not been collected yet, “what I do now have a sense of” is that “the entry point [afforded by the clinics] changed the course in terms of patients’ understanding of the disease and how they feel about its management.”

About 94% of survey respondents indicated the clinic was “extremely” helpful and the remainder said it was “very” helpful; 90% said telehealth significantly changed how they will manage their condition; and 97% said it is “extremely” important to continue the clinics. The majority of patients – 70% – indicated they did not have a dermatologist.

Education about AD at the clinics covers moisturizers/emollients, bathing habits, soaps and detergents, trigger avoidance, and the role of stress and environmental factors in disease exacerbation. Trade samples of moisturizers, mild cleansers, and other products have increasingly been available.

For prescriptions of topical steroids and other commonly prescribed medications, Dr. Friedman and associates combed GoodRx for coupons and surveyed local pharmacies for self-pay pricing to identify least expensive options. Patients with AD who were deemed likely candidates for more advanced therapies in the future were educated about these possibilities.

Alopecia areata

The addition of alopecia areata drew patients with other forms of hair loss as well, but “we weren’t going to turn anyone away who did not have that specific autoimmune form of hair loss,” Dr. Friedman said. Depending on the diagnosis, prescriptions were written for minoxidil and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

Important for follow-up is GWU’s acceptance of Medicaid and the availability of both a sliding scale for self-pay and services that assist patients in registering for Medicaid and, if eligible, other insurance plans.

Building partnerships, earning trust

Establishment of the teledermatology clinic program took legwork and relationship building. “You can’t just show up. That’s not enough,” said Dr. Friedman, who also directs the dermatology residency program at GWU. “You have to show through action and through investment of time and energy that you are legitimate, that you’re really there for the long haul.”

Dr. Friedman had assistance from the Rodham Institute, which was established at GWU (and until recently was housed there) and has a history of engagement with local stakeholders such as community centers, church leadership, politicians, and others in the Washington area. He was put in touch with Bishop Deborah Webb at the Temple of Praise Church, a community pillar in Ward 8, and from there “it was a courtship,” he said, with trust to be built and logistics to be worked out. (Budgets for the clinics, he noted, have included compensation to the church and gift cards for church volunteers who are present at the clinics.)

In the meantime, medical student volunteers from GWU, Howard University, and Georgetown University were trained in telemedicine and attended a “boot camp” on AD “so they’d be able to talk with anyone about it,” Dr. Friedman said.

Advertising “was a learning experience,” he said, and was ultimately multipronged, involving church service announcements, flyers, and, most importantly, Facebook and Instagram advertisements. (People were asked to call a dedicated phone line to schedule an appointment and were invited to register in the GW Medical Faculty Associates records system, though walk-ins to the clinics were still welcomed.)

In a comment, Misty Eleryan, MD, MS, a Mohs micrographic surgeon and dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif., said dermatology deserts are often found in rural areas and/or areas “with a higher population of marginalized communities, such as Black, Brown, or poorer individuals” – communities that tend to rely on care from urgent care or ED physicians who are unaware of how skin conditions present on darker skin tones.

Programs that educate patients about various presentations of skin conditions are helpful not only for the patients themselves, but could also enable them to help friends, family members, and colleagues, said Dr. Eleryan, who did her residency training at GWU.

“Access,” she noted, is more than just physical access to a person, place, or thing. Referring to a “five A’s” framework described several decades ago, Dr. Eleryan said access to care is characterized by affordability, availability (extent to which the physician has the requisite resources, such as personnel and technology, to meet the patient’s needs), accessibility (geographic), accommodation (extent to which the physician can meet the patient’s constraints and preferences – such as hours of operation, how communications are handled, ability to receive care without prior appointments), and acceptability (extent to which the patient is comfortable with the “more immutable characteristics” of the physician and vice versa).

The GWU program, she said, “is a great start.”

Dr. Friedman said he’s fully invested. There has long been a perception, “rightfully so, that underserved communities are overlooked especially by large institutions. One attendee told me she never expected in her lifetime to see something like this clinic and someone who looked like me caring about her community. ... It certainly says a great deal about the work we need to put in to repair longstanding injury.”

Dr. Friedman disclosed that, in addition to being a recipient of grants from Pfizer and Lilly, he is a speaker for Lilly. Dr. Eleryan said she has no relevant disclosures.

A in other underserved areas in the United States.

Washington, D.C., has “staggering health disparities that are among the largest in the country,” and Ward 8 and surrounding areas in the southeastern part of the city are “dermatology deserts,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who started the program in 2021 with a pilot project. Dr. Friedman spoke about the project, which has since been expanded to include alopecia areata, at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis conference in April and in an interview after the meeting.

Patients who attend the clinics – held at the Temple of Praise Church in a residential area of Ward 8, a predominantly Black community with a 30% poverty rate – are entered into the GW Medical Faculty Associates medical records system and educated on telemedicine best practices (such as not having light behind them during a session) and how to use telemedicine with their own device.

Those with AD who participate learn about the condition through an image-rich poster showing how it appears in various skin tones, handouts, National Eczema Association films, and discussion with medical students who staff the clinics under Dr. Friedman’s on-site supervision. Participants with alopecia areata similarly can view a poster and converse about the condition.

Patients then have a free 20-minute telehealth visit with a GWU dermatology resident in a private room, and a medical student volunteer nearby to assist with the technology if needed. They leave with a treatment plan, which often includes prescriptions, and a follow-up telemedicine appointment.

The program “is meant to be a stepping point for initiating care ... to set someone up for success for recurrent telehealth visits in the future” and for treatment before symptoms become too severe, Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “We want to demystify telemedicine and educate on the disease state and dispel myths ... so the patient understands why it’s happening” and how it can be treated.

The pilot project, funded with a grant from Pfizer, involved five 2-hour clinics held on Mondays from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m., that together served almost 50 adult and pediatric patients. Grants from Pfizer and Eli Lilly enabled additional clinics in the spring of 2023 and into the summer. And in June, GWU and Pfizer announced a $1 million national grant program focused on broad implementation of what they’ve coined the “Teledermatology Help Desk Clinic” model.

Practices or organizations that secure grants will utilize GWU’s experience and meet with an advisory council of experts in dermatology telemedicine and community advocacy. Having a “long-term plan” and commitment to sustainability is an important element of the model, said Dr. Friedman, who is chairing the grant program.

Patients deem clinic ‘extremely’ helpful

As one of the most prevalent skin disorders – and one with a documented history of elevated risk for specific populations – AD was a good starting point for the teledermatology clinic program. Patients who identify as Black have a higher incidence and prevalence of AD than those who identify as White and Hispanic, and they tend to have more severe disease. Yet they account for fewer visits to dermatologists for AD.

One cross-sectional study of about 3,500 adults in the United States with AD documented that racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities reduce outpatient utilization of AD care and increase urgent care and hospital utilization. And in a longitudinal cohort study of children in the United States with AD, Black children with poorly controlled AD were significantly less likely than White children to see a dermatologist.

Like other programs, the GWU department of dermatology had pivoted to telehealth in 2020, and a published survey of patients who attended telehealth appointments during the early part of the pandemic showed that it was generally well liked – and not only for social distancing, but for time efficiency and because transportation was not needed. Only 10% of the 168 patients who completed the survey (out of 894 asked) reported they were unlikely to undertake another telehealth visit. For 10%, eczema was the reason for the visit.

However, only 1% of the survey respondents were from Ward 8, which “begged the question, did those who really need access know this was an option?” Dr. Friedman said at the RAD meeting. He wondered whether there was not only a dermatology desert in Ward 8, but a “technology desert” as well.

Findings from a patient satisfaction survey taken at the end of the pilot program are encouraging, Dr. Friedman said. While data on follow-up visits has not been collected yet, “what I do now have a sense of” is that “the entry point [afforded by the clinics] changed the course in terms of patients’ understanding of the disease and how they feel about its management.”

About 94% of survey respondents indicated the clinic was “extremely” helpful and the remainder said it was “very” helpful; 90% said telehealth significantly changed how they will manage their condition; and 97% said it is “extremely” important to continue the clinics. The majority of patients – 70% – indicated they did not have a dermatologist.

Education about AD at the clinics covers moisturizers/emollients, bathing habits, soaps and detergents, trigger avoidance, and the role of stress and environmental factors in disease exacerbation. Trade samples of moisturizers, mild cleansers, and other products have increasingly been available.

For prescriptions of topical steroids and other commonly prescribed medications, Dr. Friedman and associates combed GoodRx for coupons and surveyed local pharmacies for self-pay pricing to identify least expensive options. Patients with AD who were deemed likely candidates for more advanced therapies in the future were educated about these possibilities.

Alopecia areata

The addition of alopecia areata drew patients with other forms of hair loss as well, but “we weren’t going to turn anyone away who did not have that specific autoimmune form of hair loss,” Dr. Friedman said. Depending on the diagnosis, prescriptions were written for minoxidil and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

Important for follow-up is GWU’s acceptance of Medicaid and the availability of both a sliding scale for self-pay and services that assist patients in registering for Medicaid and, if eligible, other insurance plans.

Building partnerships, earning trust

Establishment of the teledermatology clinic program took legwork and relationship building. “You can’t just show up. That’s not enough,” said Dr. Friedman, who also directs the dermatology residency program at GWU. “You have to show through action and through investment of time and energy that you are legitimate, that you’re really there for the long haul.”

Dr. Friedman had assistance from the Rodham Institute, which was established at GWU (and until recently was housed there) and has a history of engagement with local stakeholders such as community centers, church leadership, politicians, and others in the Washington area. He was put in touch with Bishop Deborah Webb at the Temple of Praise Church, a community pillar in Ward 8, and from there “it was a courtship,” he said, with trust to be built and logistics to be worked out. (Budgets for the clinics, he noted, have included compensation to the church and gift cards for church volunteers who are present at the clinics.)

In the meantime, medical student volunteers from GWU, Howard University, and Georgetown University were trained in telemedicine and attended a “boot camp” on AD “so they’d be able to talk with anyone about it,” Dr. Friedman said.

Advertising “was a learning experience,” he said, and was ultimately multipronged, involving church service announcements, flyers, and, most importantly, Facebook and Instagram advertisements. (People were asked to call a dedicated phone line to schedule an appointment and were invited to register in the GW Medical Faculty Associates records system, though walk-ins to the clinics were still welcomed.)

In a comment, Misty Eleryan, MD, MS, a Mohs micrographic surgeon and dermatologist in Santa Monica, Calif., said dermatology deserts are often found in rural areas and/or areas “with a higher population of marginalized communities, such as Black, Brown, or poorer individuals” – communities that tend to rely on care from urgent care or ED physicians who are unaware of how skin conditions present on darker skin tones.

Programs that educate patients about various presentations of skin conditions are helpful not only for the patients themselves, but could also enable them to help friends, family members, and colleagues, said Dr. Eleryan, who did her residency training at GWU.

“Access,” she noted, is more than just physical access to a person, place, or thing. Referring to a “five A’s” framework described several decades ago, Dr. Eleryan said access to care is characterized by affordability, availability (extent to which the physician has the requisite resources, such as personnel and technology, to meet the patient’s needs), accessibility (geographic), accommodation (extent to which the physician can meet the patient’s constraints and preferences – such as hours of operation, how communications are handled, ability to receive care without prior appointments), and acceptability (extent to which the patient is comfortable with the “more immutable characteristics” of the physician and vice versa).

The GWU program, she said, “is a great start.”

Dr. Friedman said he’s fully invested. There has long been a perception, “rightfully so, that underserved communities are overlooked especially by large institutions. One attendee told me she never expected in her lifetime to see something like this clinic and someone who looked like me caring about her community. ... It certainly says a great deal about the work we need to put in to repair longstanding injury.”

Dr. Friedman disclosed that, in addition to being a recipient of grants from Pfizer and Lilly, he is a speaker for Lilly. Dr. Eleryan said she has no relevant disclosures.

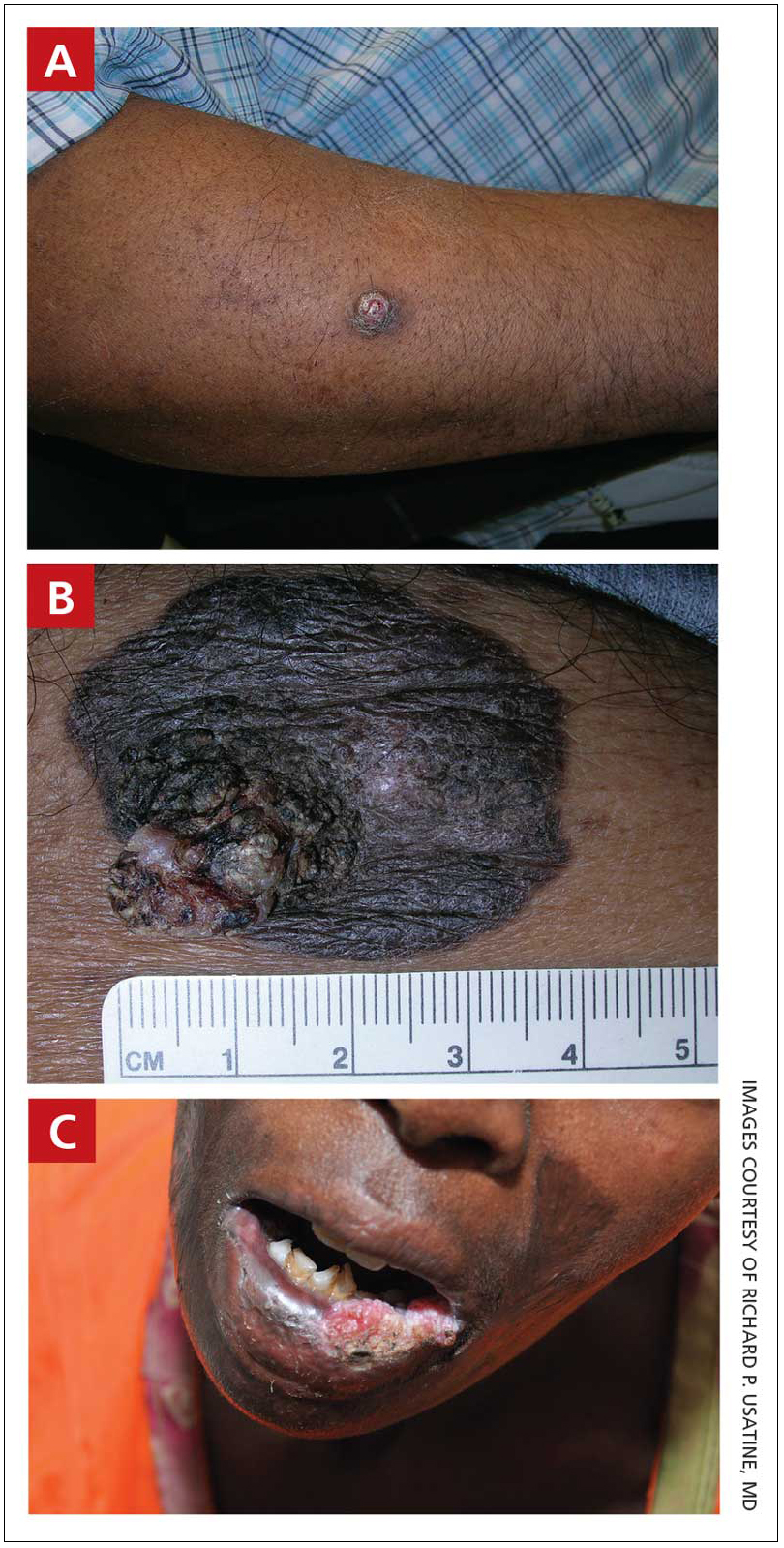

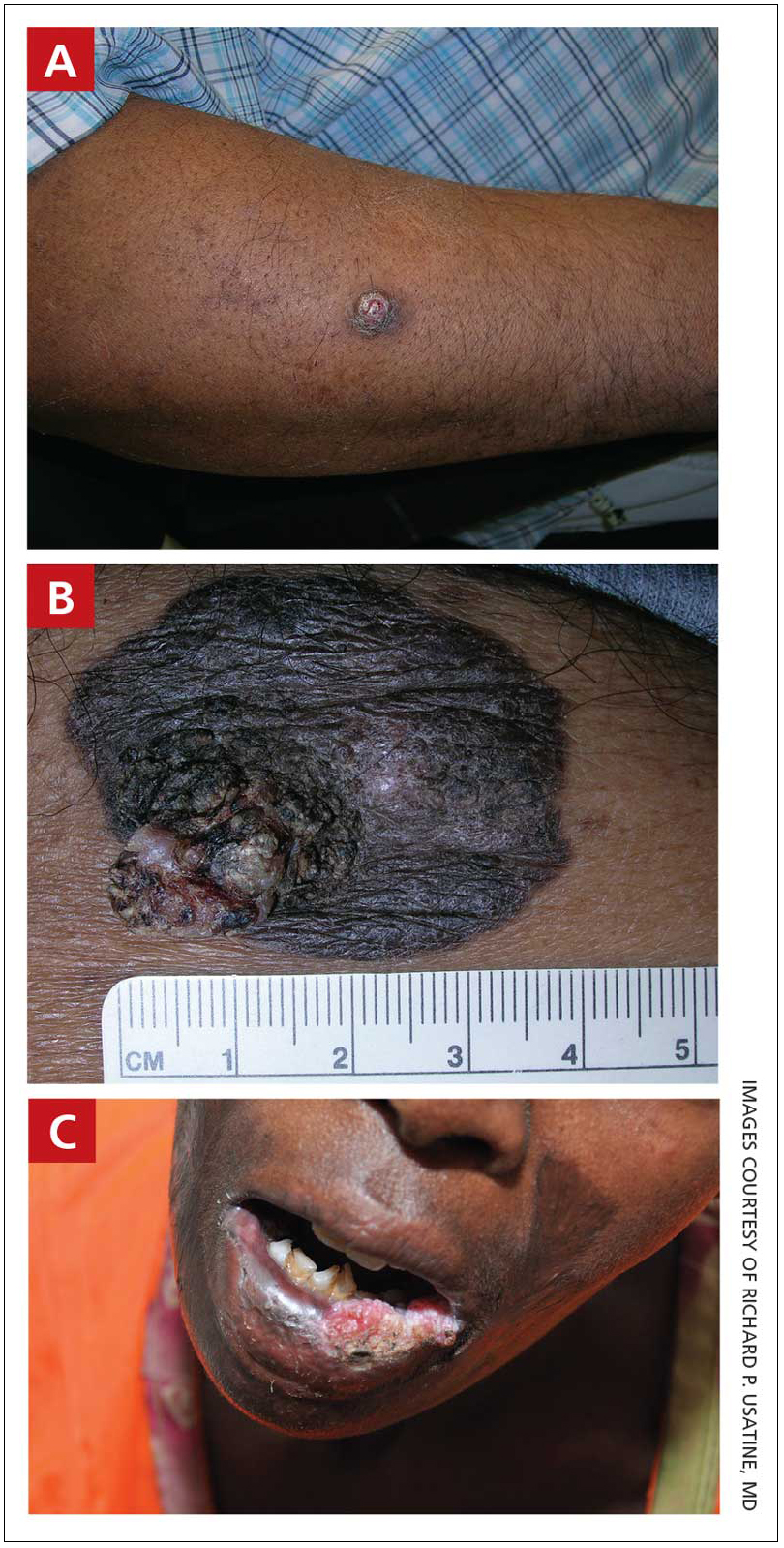

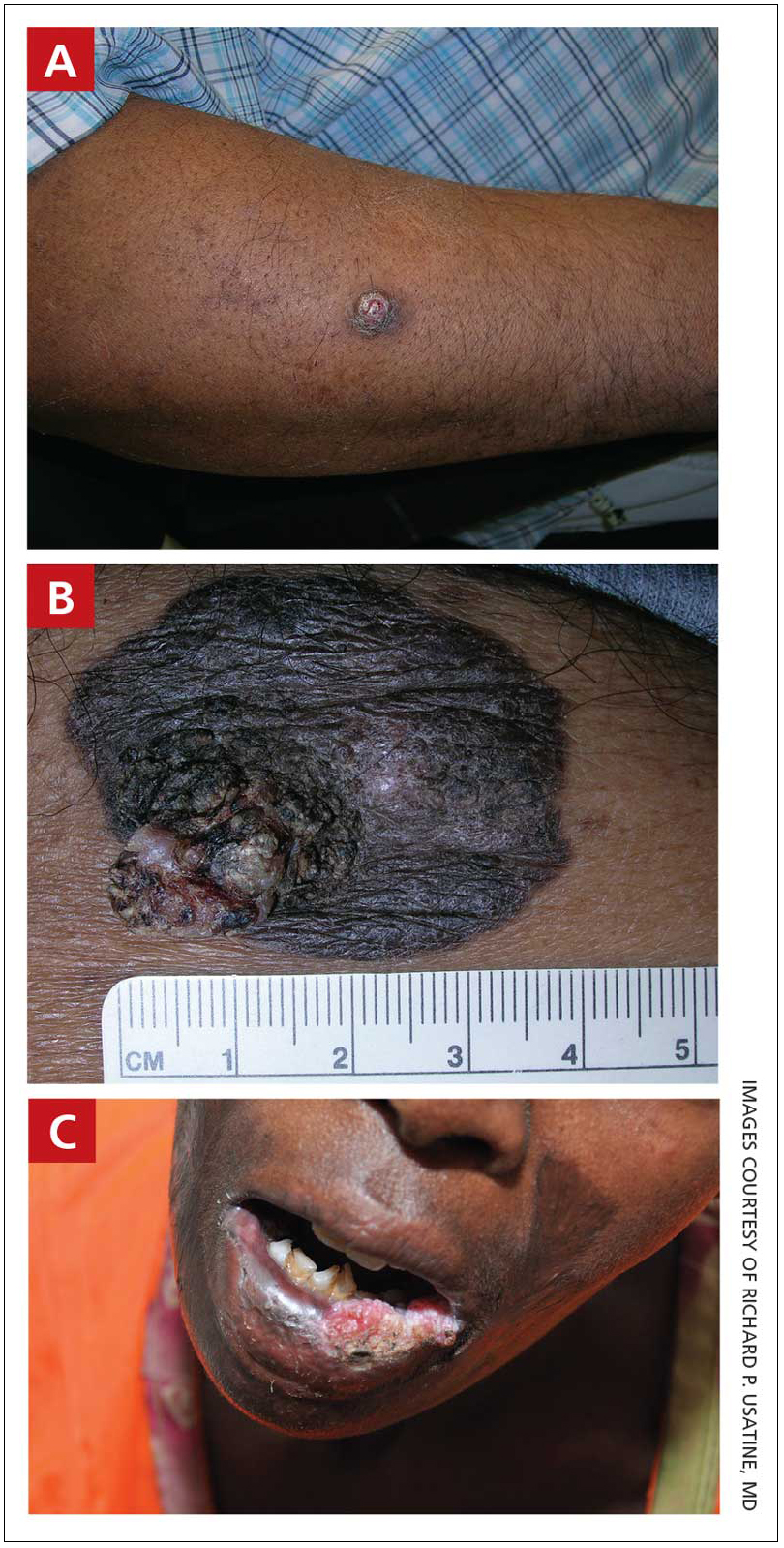

Foot rash during self-treatment

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

Case series supports targeted drugs in treatment of alopecia in children with AD

in children with AA and concomitant atopy.

It was only a little over a year ago that the JAK inhibitor baricitinib became the first systemic therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for AA in adults. In June 2023, the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib was approved for severe AA in patients as young as 12 years of age, but there is accumulating evidence that dupilumab, which binds to the interleukin-4 receptor, might be an option for even younger children with AA.

Of those who have worked with dupilumab for controlling AA in children, Brittany Craiglow, MD, an adjunct associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., updated a case series at the recent MedscapeLive! Annual Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar in Baltimore. A series of six children with AA treated with dupilumab was published 2 years ago in JAAD Case Reports.

Even in 2021, her case series was not the first report of benefit from dupilumab in children with AA, but instead contributed to a “growing body of literature” supporting the potential benefit in the setting of concomitant atopy, Dr. Craiglow, one of the authors of the series, said in an interview.

Of the six patients in that series, five had improvement and four had complete regrowth with dupilumab, whether as a monotherapy or in combination with other agents. The children ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. The age range at the time of AA onset was 3-11 years. All had atopic dermatitis (AD) and most had additional atopic conditions, such as food allergies or asthma.

Since publication, Dr. Craiglow has successfully treated many more patients with dupilumab, either as monotherapy or in combination with oral minoxidil, corticosteroids, and/or a topical JAK inhibitor. Dupilumab, which is approved for the treatment of AD in children as young as 6 months of age, has been well tolerated.

“Oral minoxidil is often a great adjuvant treatment in patients with AA and should be used unless there are contraindications,” based on the initial and subsequent experience treating AA with dupilumab, said Dr. Craiglow.

“Topical steroids can be used in combination with dupilumab and minoxidil, but in general dupilumab should not be combined with an oral JAK inhibitor,” she added.

Now, with the approval of ritlecitinib, Dr. Craiglow said this JAK inhibitor will become a first-line therapy in children 12 years or older with severe, persistent AA, but she considers a trial of dupilumab reasonable in younger children, given the controlled studies of safety for atopic diseases.

“I would say that dupilumab could be considered in the following clinical scenarios: children under 12 with AA and concomitant atopy, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergies, and/or elevated IgE; and children over the age of 12 with concomitant atopy who either have a contraindication to a JAK inhibitor or whose families have reservations about or are unwilling to take one,” Dr. Craiglow said.

In older children, she believes that dupilumab has “a much lower chance of being effective” than an oral JAK inhibitor like ritlecitinib, but it circumvents the potential safety issues of JAK inhibitors that have been observed in adults.

With ritlecitinib providing an on-label option for AA in older children, Dr. Craiglow suggested it might be easier to obtain third-party coverage for dupilumab as an alternative to a JAK inhibitor for AA in patients younger than 12, particularly when there is an indication for a concomitant atopic condition and a rationale, such as a concern about relative safety.

Two years ago, when Dr. Craiglow and her coinvestigator published their six-patient case series, a second case series was published about the same time by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. This series of 16 pediatric patients with AA on dupilumab was more heterogeneous, but four of six patients with active disease and more than 4 months of follow-up had improvement in AA, including total regrowth. The improvement was concentrated in patients with moderate to severe AD at the time of treatment.

Based on this series, the authors, led by Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, who is now an attending physician in the Dermatology Branch of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, Md., concluded that dupilumab “may be a therapeutic option for AA” when traditional therapies have failed, “especially in patients with concurrent AD or asthma, for which the benefits of dupilumab are clear.”

When contacted about where this therapy might fit on the basis of her case series and the update on Dr. Craiglow’s experience, Dr. Castelo-Soccio, like Dr. Craiglow, stressed the importance of employing this therapy selectively.

“I do think that dupilumab is a reasonable option for AA in children with atopy and IgE levels greater than 200 IU/mL, especially if treatment is for atopic dermatitis or asthma as well,” she said.

Many clinicians, including Dr. Craiglow, have experience with oral JAK inhibitors in children younger than 12. Indeed, a recently published case study associated oral abrocitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for moderate to severe AD in patients ages 12 and older, with hair regrowth in an 11-year-old child who had persistent AA for more than 6 years despite numerous conventional therapies.

However, the advantage of dupilumab in younger children is the greater evidence of safety, providing a level of reassurance for a treatment that is commonly used for severe atopic diseases but does not have a specific indication for AA, according to Dr. Craiglow.

Dr. Craiglow disclosed being a speaker for AbbVie and a speaker and consultant for Eli Lilly, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Castelo-Soccio had no disclosures.

in children with AA and concomitant atopy.

It was only a little over a year ago that the JAK inhibitor baricitinib became the first systemic therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for AA in adults. In June 2023, the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib was approved for severe AA in patients as young as 12 years of age, but there is accumulating evidence that dupilumab, which binds to the interleukin-4 receptor, might be an option for even younger children with AA.

Of those who have worked with dupilumab for controlling AA in children, Brittany Craiglow, MD, an adjunct associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., updated a case series at the recent MedscapeLive! Annual Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar in Baltimore. A series of six children with AA treated with dupilumab was published 2 years ago in JAAD Case Reports.

Even in 2021, her case series was not the first report of benefit from dupilumab in children with AA, but instead contributed to a “growing body of literature” supporting the potential benefit in the setting of concomitant atopy, Dr. Craiglow, one of the authors of the series, said in an interview.

Of the six patients in that series, five had improvement and four had complete regrowth with dupilumab, whether as a monotherapy or in combination with other agents. The children ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. The age range at the time of AA onset was 3-11 years. All had atopic dermatitis (AD) and most had additional atopic conditions, such as food allergies or asthma.

Since publication, Dr. Craiglow has successfully treated many more patients with dupilumab, either as monotherapy or in combination with oral minoxidil, corticosteroids, and/or a topical JAK inhibitor. Dupilumab, which is approved for the treatment of AD in children as young as 6 months of age, has been well tolerated.

“Oral minoxidil is often a great adjuvant treatment in patients with AA and should be used unless there are contraindications,” based on the initial and subsequent experience treating AA with dupilumab, said Dr. Craiglow.

“Topical steroids can be used in combination with dupilumab and minoxidil, but in general dupilumab should not be combined with an oral JAK inhibitor,” she added.

Now, with the approval of ritlecitinib, Dr. Craiglow said this JAK inhibitor will become a first-line therapy in children 12 years or older with severe, persistent AA, but she considers a trial of dupilumab reasonable in younger children, given the controlled studies of safety for atopic diseases.

“I would say that dupilumab could be considered in the following clinical scenarios: children under 12 with AA and concomitant atopy, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergies, and/or elevated IgE; and children over the age of 12 with concomitant atopy who either have a contraindication to a JAK inhibitor or whose families have reservations about or are unwilling to take one,” Dr. Craiglow said.

In older children, she believes that dupilumab has “a much lower chance of being effective” than an oral JAK inhibitor like ritlecitinib, but it circumvents the potential safety issues of JAK inhibitors that have been observed in adults.

With ritlecitinib providing an on-label option for AA in older children, Dr. Craiglow suggested it might be easier to obtain third-party coverage for dupilumab as an alternative to a JAK inhibitor for AA in patients younger than 12, particularly when there is an indication for a concomitant atopic condition and a rationale, such as a concern about relative safety.

Two years ago, when Dr. Craiglow and her coinvestigator published their six-patient case series, a second case series was published about the same time by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. This series of 16 pediatric patients with AA on dupilumab was more heterogeneous, but four of six patients with active disease and more than 4 months of follow-up had improvement in AA, including total regrowth. The improvement was concentrated in patients with moderate to severe AD at the time of treatment.

Based on this series, the authors, led by Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, who is now an attending physician in the Dermatology Branch of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, Md., concluded that dupilumab “may be a therapeutic option for AA” when traditional therapies have failed, “especially in patients with concurrent AD or asthma, for which the benefits of dupilumab are clear.”

When contacted about where this therapy might fit on the basis of her case series and the update on Dr. Craiglow’s experience, Dr. Castelo-Soccio, like Dr. Craiglow, stressed the importance of employing this therapy selectively.

“I do think that dupilumab is a reasonable option for AA in children with atopy and IgE levels greater than 200 IU/mL, especially if treatment is for atopic dermatitis or asthma as well,” she said.

Many clinicians, including Dr. Craiglow, have experience with oral JAK inhibitors in children younger than 12. Indeed, a recently published case study associated oral abrocitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for moderate to severe AD in patients ages 12 and older, with hair regrowth in an 11-year-old child who had persistent AA for more than 6 years despite numerous conventional therapies.

However, the advantage of dupilumab in younger children is the greater evidence of safety, providing a level of reassurance for a treatment that is commonly used for severe atopic diseases but does not have a specific indication for AA, according to Dr. Craiglow.

Dr. Craiglow disclosed being a speaker for AbbVie and a speaker and consultant for Eli Lilly, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Castelo-Soccio had no disclosures.

in children with AA and concomitant atopy.

It was only a little over a year ago that the JAK inhibitor baricitinib became the first systemic therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for AA in adults. In June 2023, the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib was approved for severe AA in patients as young as 12 years of age, but there is accumulating evidence that dupilumab, which binds to the interleukin-4 receptor, might be an option for even younger children with AA.

Of those who have worked with dupilumab for controlling AA in children, Brittany Craiglow, MD, an adjunct associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., updated a case series at the recent MedscapeLive! Annual Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar in Baltimore. A series of six children with AA treated with dupilumab was published 2 years ago in JAAD Case Reports.

Even in 2021, her case series was not the first report of benefit from dupilumab in children with AA, but instead contributed to a “growing body of literature” supporting the potential benefit in the setting of concomitant atopy, Dr. Craiglow, one of the authors of the series, said in an interview.

Of the six patients in that series, five had improvement and four had complete regrowth with dupilumab, whether as a monotherapy or in combination with other agents. The children ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. The age range at the time of AA onset was 3-11 years. All had atopic dermatitis (AD) and most had additional atopic conditions, such as food allergies or asthma.

Since publication, Dr. Craiglow has successfully treated many more patients with dupilumab, either as monotherapy or in combination with oral minoxidil, corticosteroids, and/or a topical JAK inhibitor. Dupilumab, which is approved for the treatment of AD in children as young as 6 months of age, has been well tolerated.

“Oral minoxidil is often a great adjuvant treatment in patients with AA and should be used unless there are contraindications,” based on the initial and subsequent experience treating AA with dupilumab, said Dr. Craiglow.

“Topical steroids can be used in combination with dupilumab and minoxidil, but in general dupilumab should not be combined with an oral JAK inhibitor,” she added.

Now, with the approval of ritlecitinib, Dr. Craiglow said this JAK inhibitor will become a first-line therapy in children 12 years or older with severe, persistent AA, but she considers a trial of dupilumab reasonable in younger children, given the controlled studies of safety for atopic diseases.

“I would say that dupilumab could be considered in the following clinical scenarios: children under 12 with AA and concomitant atopy, such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergies, and/or elevated IgE; and children over the age of 12 with concomitant atopy who either have a contraindication to a JAK inhibitor or whose families have reservations about or are unwilling to take one,” Dr. Craiglow said.

In older children, she believes that dupilumab has “a much lower chance of being effective” than an oral JAK inhibitor like ritlecitinib, but it circumvents the potential safety issues of JAK inhibitors that have been observed in adults.

With ritlecitinib providing an on-label option for AA in older children, Dr. Craiglow suggested it might be easier to obtain third-party coverage for dupilumab as an alternative to a JAK inhibitor for AA in patients younger than 12, particularly when there is an indication for a concomitant atopic condition and a rationale, such as a concern about relative safety.

Two years ago, when Dr. Craiglow and her coinvestigator published their six-patient case series, a second case series was published about the same time by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. This series of 16 pediatric patients with AA on dupilumab was more heterogeneous, but four of six patients with active disease and more than 4 months of follow-up had improvement in AA, including total regrowth. The improvement was concentrated in patients with moderate to severe AD at the time of treatment.

Based on this series, the authors, led by Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, who is now an attending physician in the Dermatology Branch of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, Md., concluded that dupilumab “may be a therapeutic option for AA” when traditional therapies have failed, “especially in patients with concurrent AD or asthma, for which the benefits of dupilumab are clear.”

When contacted about where this therapy might fit on the basis of her case series and the update on Dr. Craiglow’s experience, Dr. Castelo-Soccio, like Dr. Craiglow, stressed the importance of employing this therapy selectively.

“I do think that dupilumab is a reasonable option for AA in children with atopy and IgE levels greater than 200 IU/mL, especially if treatment is for atopic dermatitis or asthma as well,” she said.

Many clinicians, including Dr. Craiglow, have experience with oral JAK inhibitors in children younger than 12. Indeed, a recently published case study associated oral abrocitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for moderate to severe AD in patients ages 12 and older, with hair regrowth in an 11-year-old child who had persistent AA for more than 6 years despite numerous conventional therapies.

However, the advantage of dupilumab in younger children is the greater evidence of safety, providing a level of reassurance for a treatment that is commonly used for severe atopic diseases but does not have a specific indication for AA, according to Dr. Craiglow.

Dr. Craiglow disclosed being a speaker for AbbVie and a speaker and consultant for Eli Lilly, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. Dr. Castelo-Soccio had no disclosures.

New guidelines for laser treatment of cutaneous vascular anomalies

A new practice guideline is setting a standard for doctors who use lasers to treat cutaneous vascular anomalies.

Poor treatment has been an issue in this field because no uniform guidelines existed to inform practice, according to a press release from the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The laser treatment settings can vary based on the type and location of the birthmark and also the patient’s skin type, which has resulted in an inconsistent approach from clinicians, according to the release.

“For decades, I have observed adverse outcomes from the improper laser treatment of vascular birthmarks,” Linda Rozell-Shannon, PhD, president and founder of the Vascular Birthmarks Foundation said in a statement from ASLMS. “As a result of these guidelines, patient outcomes will be improved.”