User login

Study provides consensus on lab monitoring during isotretinoin therapy

For generally ideally within a month prior to the start of treatment, and a second time at peak dose.

Other tests such as complete blood cell counts and basic metabolic panels as well as specific laboratory tests such as LDL and HDL cholesterol should not be routinely monitored.

Those are key conclusions from a Delphi consensus study that included 22 acne experts from five continents and was published in JAMA Dermatology.

“Our results apply findings from recent literature and are in accordance with recent studies that have recommended against excessive laboratory monitoring,” senior corresponding author Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, and coauthors wrote. “For instance, several studies in both teenagers and adults have shown that routine complete blood cell count laboratory tests are unnecessary without suspicion of an underlying abnormality and that rare abnormalities, if present, either resolved or remained stable without clinical impact on treatment. Likewise, liver function tests and lipid panels ordered at baseline and after 2 months of therapy were deemed sufficient if the clinical context and results do not suggest potential abnormalities.”

The authors also noted that, while published acne management guidelines exist, such as the American Academy of Dermatology work group guidelines and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline, “the specific recommendations surrounding laboratory monitoring frequency are nonstandardized and often nonspecific.”

To establish a consensus for isotretinoin laboratory monitoring, Dr. Mostaghimi, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to administer four rounds of electronic surveys to 22 board-certified dermatologists between 2021 and 2022. The primary outcome measured was whether participants could reach consensus on key isotretinoin lab monitoring parameters. Responses that failed to reach a threshold of 70% indicated no consensus.

The surveyed dermatologists had been in practice for a mean of 23.7 years, 54.5% were female, 54.5% practiced in an academic setting, and 63.9% were based in North America. They reached consensus for checking ALT within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (89.5%), but not checking monthly (76.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%). They also reached consensus on checking triglycerides within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (78.9%) but not to check monthly (84.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%).

Meanwhile, consensus was achieved for not checking complete blood cell count or basic metabolic panel parameters at any point during isotretinoin treatment (all > 70%), as well as not checking gamma-glutamyl transferase (78.9%), bilirubin (81.0%), albumin (72.7%), total protein (72.7%), LDL cholesterol (73.7%), HDL cholesterol (73.7%), or C-reactive protein (77.3%).

“Additional research is required to determine best practices for laboratory measures that did not reach consensus,” the authors wrote. The study results “are intended to guide appropriate clinical decision-making,” they added. “Although our recommendations cannot replace clinical judgment based on the unique circumstances of individual patients, we believe they provide a framework for management of a typical, otherwise healthy patient being treated with isotretinoin for acne. More routine monitoring, or reduced monitoring, should be considered on a case-by-case basis accounting for the unique medical history, circumstances, and baseline abnormalities, if present, of each patient.”

“Practicing dermatologists, including myself, routinely check blood laboratory values during isotretinoin treatment,” said Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “Even though just a small number of U.S.-based and international acne researchers were involved in this Delphi consensus statement, this article still makes us practicing clinicians feel more comfortable in checking fewer lab chemistries and also less frequently checking labs when we use isotretinoin.

“That said, I don’t think most of us are ready, because of legal reasons, to do that infrequent monitoring” during isotretinoin therapy, Dr. Green added. “I think most dermatologists do not routinely perform CBCs anymore, but we still feel obligated to check triglycerides and liver function more frequently” than recommended in the new study.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported receiving grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees and licensing from Concert, personal fees from Bioniz, holds equity and advisory board membership from Hims & Hers and Figure 1, personal fees from Digital Diagnostics, and personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work. Other authors reported serving as an adviser, a speaker consultant, investigator, and/or board member, or having received honoraria from different pharmaceutical companies; several authors had no disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

For generally ideally within a month prior to the start of treatment, and a second time at peak dose.

Other tests such as complete blood cell counts and basic metabolic panels as well as specific laboratory tests such as LDL and HDL cholesterol should not be routinely monitored.

Those are key conclusions from a Delphi consensus study that included 22 acne experts from five continents and was published in JAMA Dermatology.

“Our results apply findings from recent literature and are in accordance with recent studies that have recommended against excessive laboratory monitoring,” senior corresponding author Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, and coauthors wrote. “For instance, several studies in both teenagers and adults have shown that routine complete blood cell count laboratory tests are unnecessary without suspicion of an underlying abnormality and that rare abnormalities, if present, either resolved or remained stable without clinical impact on treatment. Likewise, liver function tests and lipid panels ordered at baseline and after 2 months of therapy were deemed sufficient if the clinical context and results do not suggest potential abnormalities.”

The authors also noted that, while published acne management guidelines exist, such as the American Academy of Dermatology work group guidelines and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline, “the specific recommendations surrounding laboratory monitoring frequency are nonstandardized and often nonspecific.”

To establish a consensus for isotretinoin laboratory monitoring, Dr. Mostaghimi, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to administer four rounds of electronic surveys to 22 board-certified dermatologists between 2021 and 2022. The primary outcome measured was whether participants could reach consensus on key isotretinoin lab monitoring parameters. Responses that failed to reach a threshold of 70% indicated no consensus.

The surveyed dermatologists had been in practice for a mean of 23.7 years, 54.5% were female, 54.5% practiced in an academic setting, and 63.9% were based in North America. They reached consensus for checking ALT within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (89.5%), but not checking monthly (76.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%). They also reached consensus on checking triglycerides within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (78.9%) but not to check monthly (84.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%).

Meanwhile, consensus was achieved for not checking complete blood cell count or basic metabolic panel parameters at any point during isotretinoin treatment (all > 70%), as well as not checking gamma-glutamyl transferase (78.9%), bilirubin (81.0%), albumin (72.7%), total protein (72.7%), LDL cholesterol (73.7%), HDL cholesterol (73.7%), or C-reactive protein (77.3%).

“Additional research is required to determine best practices for laboratory measures that did not reach consensus,” the authors wrote. The study results “are intended to guide appropriate clinical decision-making,” they added. “Although our recommendations cannot replace clinical judgment based on the unique circumstances of individual patients, we believe they provide a framework for management of a typical, otherwise healthy patient being treated with isotretinoin for acne. More routine monitoring, or reduced monitoring, should be considered on a case-by-case basis accounting for the unique medical history, circumstances, and baseline abnormalities, if present, of each patient.”

“Practicing dermatologists, including myself, routinely check blood laboratory values during isotretinoin treatment,” said Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “Even though just a small number of U.S.-based and international acne researchers were involved in this Delphi consensus statement, this article still makes us practicing clinicians feel more comfortable in checking fewer lab chemistries and also less frequently checking labs when we use isotretinoin.

“That said, I don’t think most of us are ready, because of legal reasons, to do that infrequent monitoring” during isotretinoin therapy, Dr. Green added. “I think most dermatologists do not routinely perform CBCs anymore, but we still feel obligated to check triglycerides and liver function more frequently” than recommended in the new study.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported receiving grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees and licensing from Concert, personal fees from Bioniz, holds equity and advisory board membership from Hims & Hers and Figure 1, personal fees from Digital Diagnostics, and personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work. Other authors reported serving as an adviser, a speaker consultant, investigator, and/or board member, or having received honoraria from different pharmaceutical companies; several authors had no disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

For generally ideally within a month prior to the start of treatment, and a second time at peak dose.

Other tests such as complete blood cell counts and basic metabolic panels as well as specific laboratory tests such as LDL and HDL cholesterol should not be routinely monitored.

Those are key conclusions from a Delphi consensus study that included 22 acne experts from five continents and was published in JAMA Dermatology.

“Our results apply findings from recent literature and are in accordance with recent studies that have recommended against excessive laboratory monitoring,” senior corresponding author Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, and coauthors wrote. “For instance, several studies in both teenagers and adults have shown that routine complete blood cell count laboratory tests are unnecessary without suspicion of an underlying abnormality and that rare abnormalities, if present, either resolved or remained stable without clinical impact on treatment. Likewise, liver function tests and lipid panels ordered at baseline and after 2 months of therapy were deemed sufficient if the clinical context and results do not suggest potential abnormalities.”

The authors also noted that, while published acne management guidelines exist, such as the American Academy of Dermatology work group guidelines and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline, “the specific recommendations surrounding laboratory monitoring frequency are nonstandardized and often nonspecific.”

To establish a consensus for isotretinoin laboratory monitoring, Dr. Mostaghimi, of the department of dermatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues used a Delphi process to administer four rounds of electronic surveys to 22 board-certified dermatologists between 2021 and 2022. The primary outcome measured was whether participants could reach consensus on key isotretinoin lab monitoring parameters. Responses that failed to reach a threshold of 70% indicated no consensus.

The surveyed dermatologists had been in practice for a mean of 23.7 years, 54.5% were female, 54.5% practiced in an academic setting, and 63.9% were based in North America. They reached consensus for checking ALT within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (89.5%), but not checking monthly (76.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%). They also reached consensus on checking triglycerides within a month prior to initiation (89.5%) and at peak dose (78.9%) but not to check monthly (84.2%) or after completing treatment (73.7%).

Meanwhile, consensus was achieved for not checking complete blood cell count or basic metabolic panel parameters at any point during isotretinoin treatment (all > 70%), as well as not checking gamma-glutamyl transferase (78.9%), bilirubin (81.0%), albumin (72.7%), total protein (72.7%), LDL cholesterol (73.7%), HDL cholesterol (73.7%), or C-reactive protein (77.3%).

“Additional research is required to determine best practices for laboratory measures that did not reach consensus,” the authors wrote. The study results “are intended to guide appropriate clinical decision-making,” they added. “Although our recommendations cannot replace clinical judgment based on the unique circumstances of individual patients, we believe they provide a framework for management of a typical, otherwise healthy patient being treated with isotretinoin for acne. More routine monitoring, or reduced monitoring, should be considered on a case-by-case basis accounting for the unique medical history, circumstances, and baseline abnormalities, if present, of each patient.”

“Practicing dermatologists, including myself, routinely check blood laboratory values during isotretinoin treatment,” said Lawrence J. Green, MD, clinical professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “Even though just a small number of U.S.-based and international acne researchers were involved in this Delphi consensus statement, this article still makes us practicing clinicians feel more comfortable in checking fewer lab chemistries and also less frequently checking labs when we use isotretinoin.

“That said, I don’t think most of us are ready, because of legal reasons, to do that infrequent monitoring” during isotretinoin therapy, Dr. Green added. “I think most dermatologists do not routinely perform CBCs anymore, but we still feel obligated to check triglycerides and liver function more frequently” than recommended in the new study.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported receiving grants and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees and licensing from Concert, personal fees from Bioniz, holds equity and advisory board membership from Hims & Hers and Figure 1, personal fees from Digital Diagnostics, and personal fees from AbbVie outside the submitted work. Other authors reported serving as an adviser, a speaker consultant, investigator, and/or board member, or having received honoraria from different pharmaceutical companies; several authors had no disclosures. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

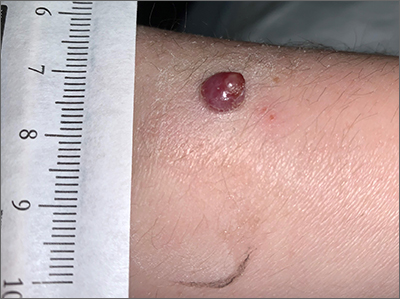

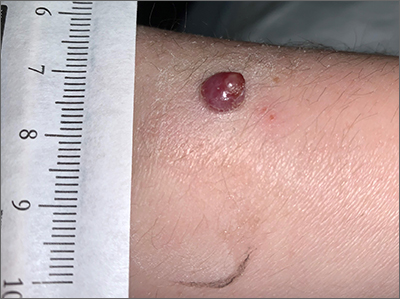

Bleeding arm lesion

Pyogenic granulomas (PGs), also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, manifest as friable, moist or glistening, papules. PGs are a benign vascular proliferation. They often have a collarette, which is subtle in this lesion, and they bleed with minimal trauma. They are commonly seen on the gingiva during pregnancy, the umbilical area in newborns, or at sites of trauma.

Since PGs often occur during pregnancy, it’s been suggested that their development is related to hormonal changes.1 It’s also been suggested that PGs are the result of an abnormal hypertrophic healing response, as they can occur in men, infants (at the umbilical stump), and even within blood vessels.1

Although benign and painless, PGs are usually hard to ignore due to their raised appearance, tendency to bleed, and the low likelihood that they will resolve on their own. There are multiple physical treatment options available, including excision with primary closure, curettage followed by electrodessication, laser treatment, and cryosurgery. Topical therapies include timolol (a beta-blocker that has been used successfully with congenital hemangiomas), imiquimod, and trichloroacetic acid.1 These topical medications do not require any anesthetic, which may make them an appealing option for children. Unfortunately, topical medications require multiple applications over a period of 2 or more weeks.

In this case, the lesion was shaved off and sent out to pathology to rule out amelanotic melanoma. The pathology for this patient confirmed PG. Immediately following the lesion’s removal, the physician performed 2 cycles of curettage and electrodessication. Thus, the patient’s treatment was completed on the same day as her evaluation.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Plachouri KM, Georgiou S. Therapeutic approaches to pyogenic granuloma: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:642-648. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14268

Pyogenic granulomas (PGs), also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, manifest as friable, moist or glistening, papules. PGs are a benign vascular proliferation. They often have a collarette, which is subtle in this lesion, and they bleed with minimal trauma. They are commonly seen on the gingiva during pregnancy, the umbilical area in newborns, or at sites of trauma.

Since PGs often occur during pregnancy, it’s been suggested that their development is related to hormonal changes.1 It’s also been suggested that PGs are the result of an abnormal hypertrophic healing response, as they can occur in men, infants (at the umbilical stump), and even within blood vessels.1

Although benign and painless, PGs are usually hard to ignore due to their raised appearance, tendency to bleed, and the low likelihood that they will resolve on their own. There are multiple physical treatment options available, including excision with primary closure, curettage followed by electrodessication, laser treatment, and cryosurgery. Topical therapies include timolol (a beta-blocker that has been used successfully with congenital hemangiomas), imiquimod, and trichloroacetic acid.1 These topical medications do not require any anesthetic, which may make them an appealing option for children. Unfortunately, topical medications require multiple applications over a period of 2 or more weeks.

In this case, the lesion was shaved off and sent out to pathology to rule out amelanotic melanoma. The pathology for this patient confirmed PG. Immediately following the lesion’s removal, the physician performed 2 cycles of curettage and electrodessication. Thus, the patient’s treatment was completed on the same day as her evaluation.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Pyogenic granulomas (PGs), also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, manifest as friable, moist or glistening, papules. PGs are a benign vascular proliferation. They often have a collarette, which is subtle in this lesion, and they bleed with minimal trauma. They are commonly seen on the gingiva during pregnancy, the umbilical area in newborns, or at sites of trauma.

Since PGs often occur during pregnancy, it’s been suggested that their development is related to hormonal changes.1 It’s also been suggested that PGs are the result of an abnormal hypertrophic healing response, as they can occur in men, infants (at the umbilical stump), and even within blood vessels.1

Although benign and painless, PGs are usually hard to ignore due to their raised appearance, tendency to bleed, and the low likelihood that they will resolve on their own. There are multiple physical treatment options available, including excision with primary closure, curettage followed by electrodessication, laser treatment, and cryosurgery. Topical therapies include timolol (a beta-blocker that has been used successfully with congenital hemangiomas), imiquimod, and trichloroacetic acid.1 These topical medications do not require any anesthetic, which may make them an appealing option for children. Unfortunately, topical medications require multiple applications over a period of 2 or more weeks.

In this case, the lesion was shaved off and sent out to pathology to rule out amelanotic melanoma. The pathology for this patient confirmed PG. Immediately following the lesion’s removal, the physician performed 2 cycles of curettage and electrodessication. Thus, the patient’s treatment was completed on the same day as her evaluation.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Plachouri KM, Georgiou S. Therapeutic approaches to pyogenic granuloma: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:642-648. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14268

1. Plachouri KM, Georgiou S. Therapeutic approaches to pyogenic granuloma: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:642-648. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14268

Adolescent female with rash on the arms and posterior legs

Erythema annulare centrifugum

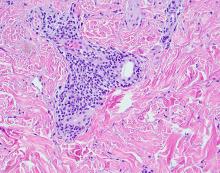

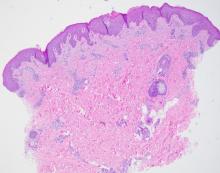

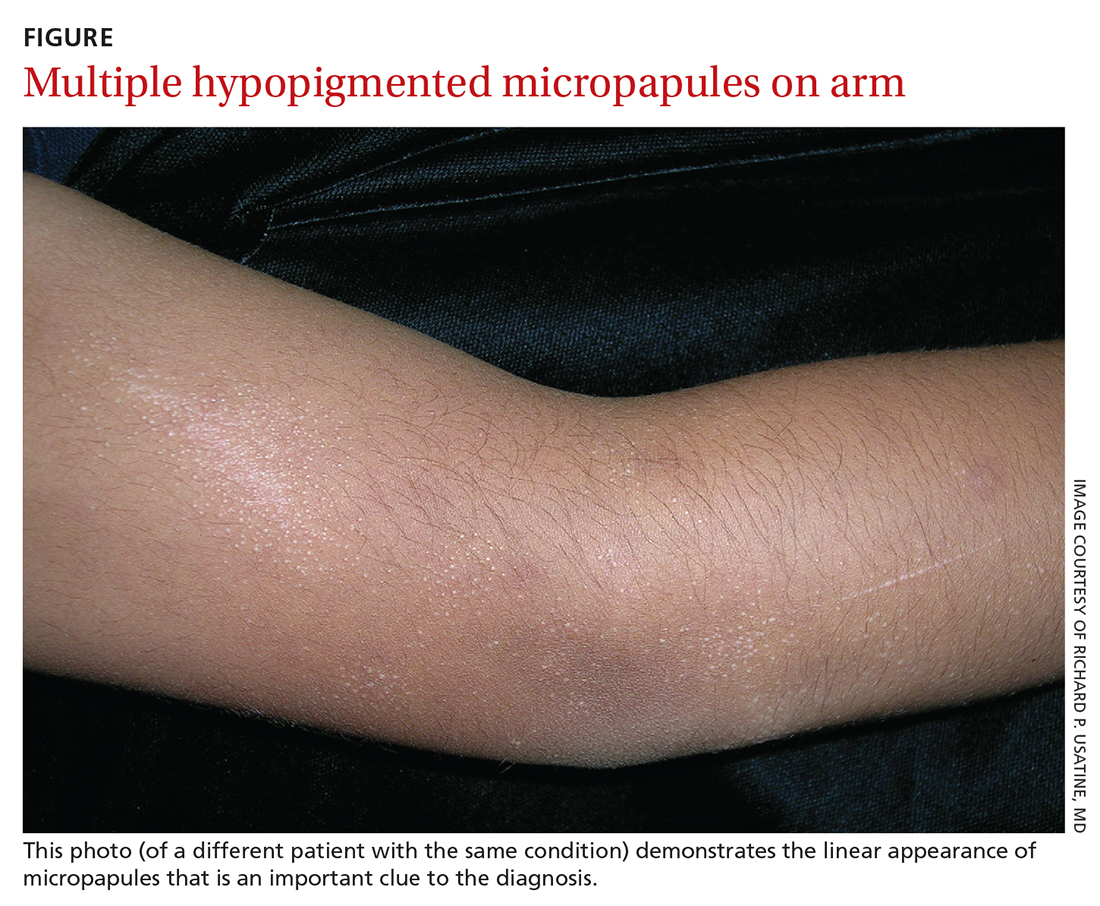

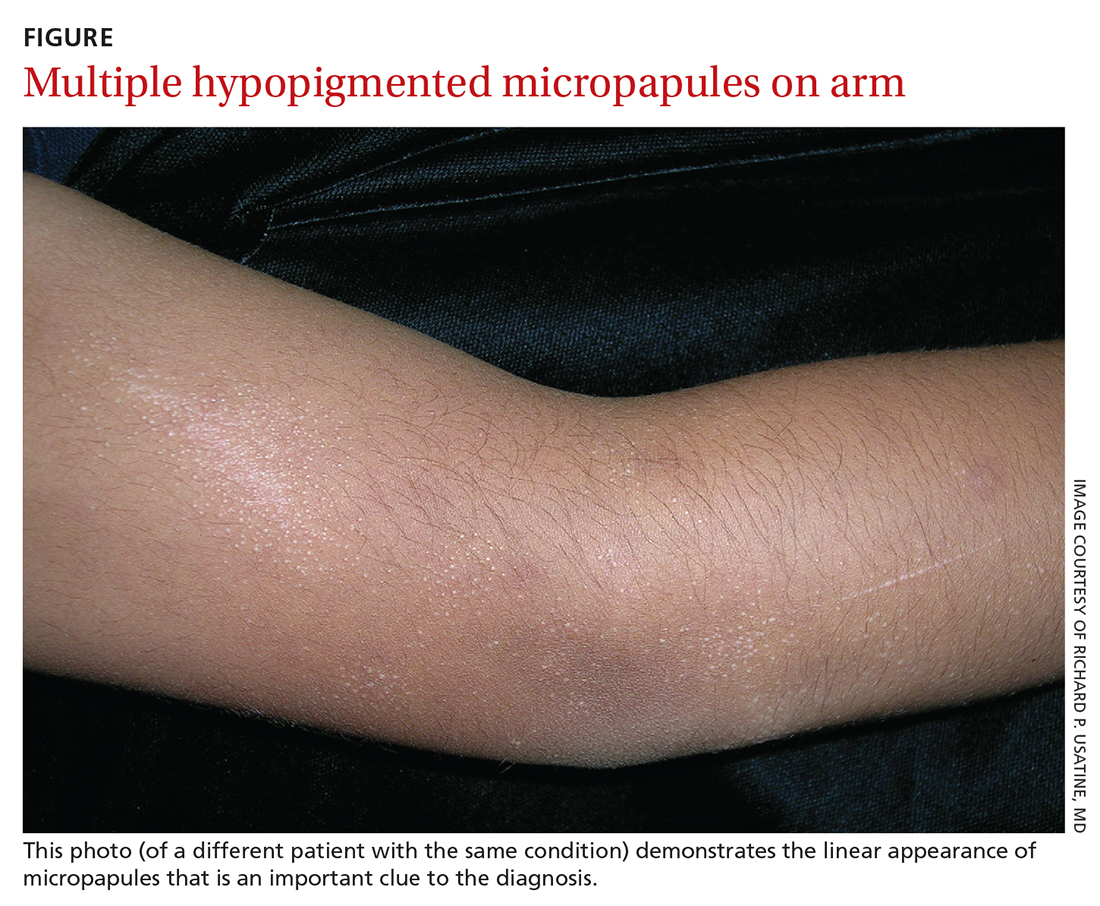

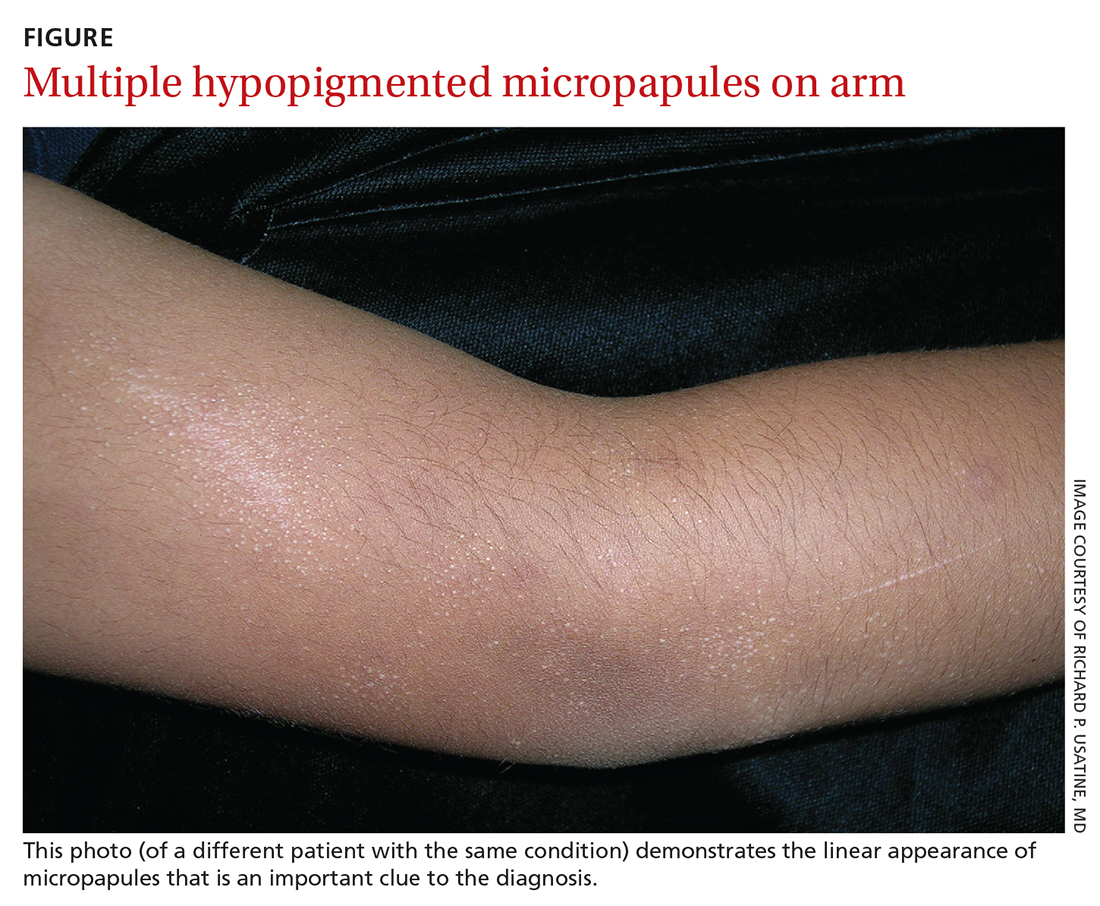

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A thorough body examination failed to reveal any other rashes or lesions suggestive of a fungal infection. A blood count and urinalysis were within normal limits. She had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A potassium hydroxide analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements. Punch biopsy of the skin on the left arm revealed focal intermittent parakeratosis, mildly acanthotic and spongiotic epidermis, and a tight superficial perivascular chronic dermatitis consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figures). Given these findings, a diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) was rendered.

EAC is a rare, reactive skin rash characterized by redness (erythema) and ring-shaped lesions (annulare) that slowly spread from the center (centrifugum). The lesions present with a characteristic trailing scale on the inner border of the erythematous ring. Lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and commonly involve the trunk, buttocks, hips, and upper legs. It is important to note that its duration is highly variable, ranging from weeks to decades, with most cases persisting for 9 months. EAC typically affects young or middle-aged adults but can occur at any age.

Although the etiology of EAC is unknown, it is believed to be a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign antigen. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly reported as triggers as well as other viral infections, medications, malignancy, underlying systemic disease, and certain foods. Treatment depends on the underlying condition and removing the implicated agent. However, most cases of EAC are idiopathic and self-limiting. It is possible that our patient’s prior history of tinea capitis could have triggered the skin lesions suggestive of EAC, but interestingly, these lesions did not go away after the fungal infection was cleared and have continued to recur. For patients with refractory lesions or treatment of patients without an identifiable cause, the use of oral antimicrobials has been proposed. Medications such as azithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, and metronidazole have been reported to be helpful in some patients with refractory EAC. Our patient wanted to continue topical treatment with betamethasone as needed and may consider antimicrobial therapy if the lesions continue to recur.

Tinea corporis refers to a superficial fungal infection of the skin. It may present as one or more asymmetrical, annular, pruritic plaques with a raised scaly leading edge rather than the trailing scale seen with EAC. Diagnosis is made by KOH examination of skin scrapings. Common risk factors include close contact with an infected person or animal, warm, moist environments, sharing personal items, and prolonged use of systemic corticosteroids. Our patient’s KOH analysis of skin scrapings was negative for fungal elements.

Erythema marginatum is a rare skin rash commonly seen with acute rheumatic fever secondary to streptococcal infection. It presents as annular erythematous lesions on the trunk and proximal extremities that are exacerbated by heat. It is often associated with active carditis related to rheumatic fever. This self-limited rash usually resolves in 2-3 days. Our patient was asymptomatic without involvement of other organs.

Like EAC, granuloma annulare is a benign chronic skin condition that presents with ring-shaped lesions. Its etiology is unknown, and lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Localized granuloma annulare typically presents as reddish-brown papules or plaques on the fingers, hands, elbows, dorsal feet, or ankles. The distinguishing feature of granuloma annulare from other annular lesions is its absence of scale.

Urticaria multiforme is an allergic hypersensitivity reaction commonly linked to viral infections, medications, and immunizations. Clinical features include blanchable annular/polycyclic lesions with a central purplish or dusky hue. Diagnostic pearls include the presence of pruritus, dermatographism, and individual lesions that resolve within 24 hours, all of which were not found in our patient’s case.

Ms. Laborada is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Ms. Laborada and Dr. Matiz have no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Paller A and Mancini AJ. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2011.

2. McDaniel B and Cook C. “Erythema annulare centrifugum” 2021 Aug 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan. PMID: 29494101.

3. Leung AK e al. Drugs Context. 2020 Jul 20;9:5-6.

4. Majmundar VD and Nagalli S. “Erythema marginatum” 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022 Jan.

5. Piette EW and Rosenbach M. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75(3):467-79.

6. Barros M et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Jan 28;14(1):e241011.

A review of systems was noncontributory. She was not taking any other medications or vitamin supplements. There were no pets at home and no other affected family members. Physical exam was notable for scattered, pink, annular plaques with central clearing, faint brownish pigmentation, and fine scale.

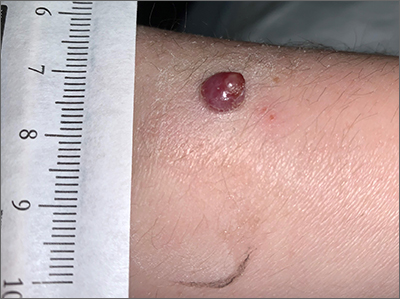

Basal cell carcinoma

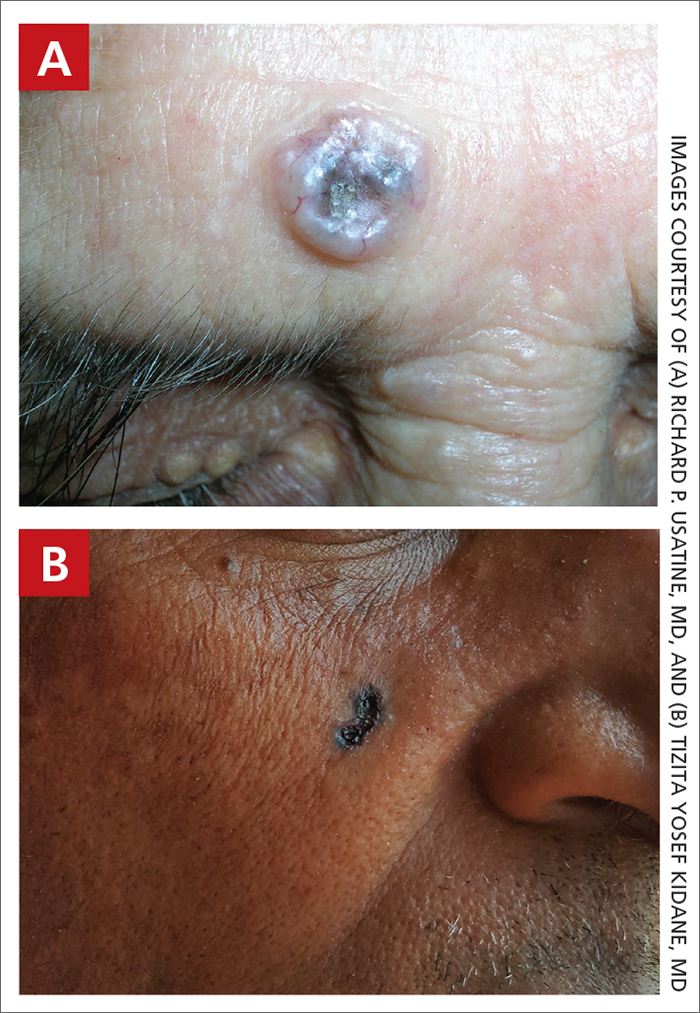

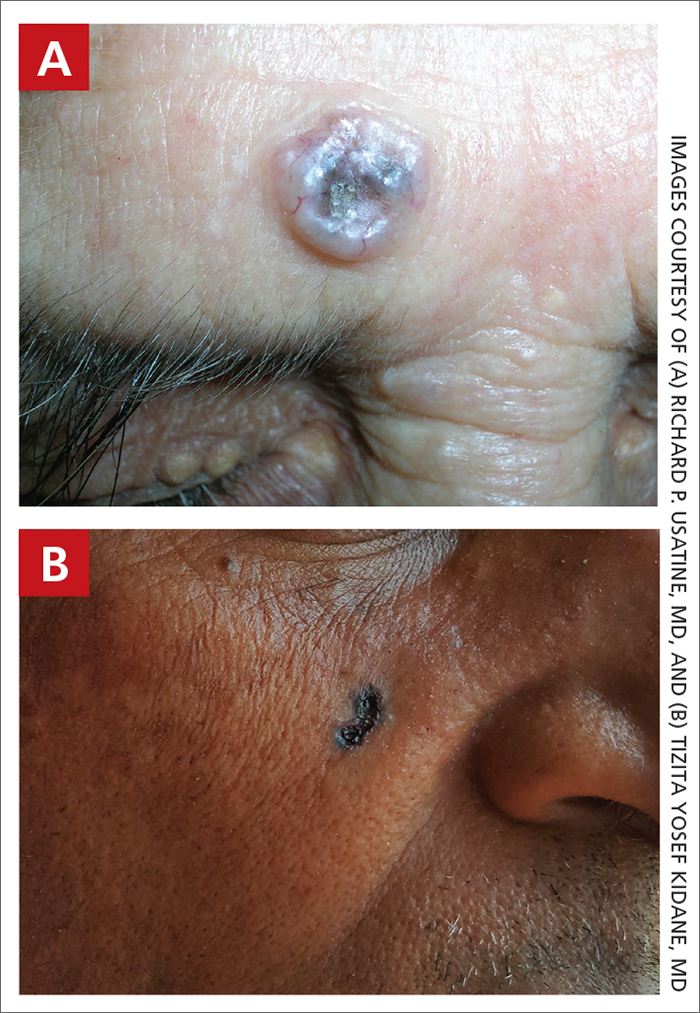

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

THE COMPARISON

A Nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) with a pearly rolled border, central pigmentation, and telangiectasia on the forehead of an 80-year-old Hispanic woman (light skin tone).

B Nodular BCC on the cheek of a 64-year-old Black man. The dark nonhealing ulcer had a subtle, pearly, rolled border and no visible telangiectasia.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is most prevalent in individuals with lighter skin tones and rarely affects those with darker skin tones. Unfortunately, the lower incidence and lack of surveillance frequently result in a delayed diagnosis and increased morbidity for the skin of color population.1

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in White, Asian, and Hispanic individuals and the second most common in Black individuals. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in Black individuals.2

Although BCCs are rare in individuals with darker skin tones, they most often develop in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region.1 In one study in an academic urban medical center, BCCs were more likely to occur in lightly pigmented vs darkly pigmented Black individuals.3

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The classic BCC manifestation of a pearly papule with rolled borders and telangiectasia may not be seen in the skin of color population, especially among those with darker skin tones.4 In patient A, a Hispanic woman, these features are present along with hyperpigmentation. More than 50% of BCCs are pigmented in patients with skin of color vs only 5% in White individuals. 5-7 The incidence of a pigmented BCC is twice as frequent in Hispanic individuals (FIGURE, A) as in non- Hispanic White individuals.7 Any skin cancer can present with ulcerations. So, while this is not specific to BCC, it is a reason to consider biopsy.

Worth noting

Pigmented BCC can mimic melanoma clinically and even when viewed with a dermatoscope, but such a suspicious lesion should prompt the clinician to perform a biopsy regardless of the type of suspected cancer. With experience and training, however, physicians can use dermoscopy to help make this distinction.

Note that skin of color is found in a heterogeneous population with a spectrum of skin tones and genetic/ethnic variability. In my practice in San Antonio (RPU), BCC is uncommon in Black patients and relatively common in Hispanic patients with lighter skin tones (FIGURE, A).

There is speculation that a lower incidence of BCC in the skin of color population leads to a low index of suspicion, which contributes to delayed diagnoses with poorer outcomes.1 There are no firm data to support this because the rare occurrence of BCC in darker skin tones makes this a challenge to study.

Health disparity highlight

In general, barriers to health care include poverty, lack of education, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism. One study on keratinocyte skin cancers including BCC and squamous cell carcinoma found that these cancers were more costly to treat and required more health care resources, such as ambulatory visits and medication costs, in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to achieve health equity through education of patients and health care providers about the appearance of BCC in skin of color with the goal of earlier diagnosis. Any nonhealing ulcer on the skin (FIGURE, B) should prompt consideration of skin cancer—regardless of skin color.

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

1. Ahluwalia J, Hadjicharalambous E, Mehregan D. Basal cell carcinoma in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:484-486.

2. Zakhem GA, Pulavarty AN, Lester JC, et al. Skin cancer in people of color: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23: 137-151. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00662-z

3. Halder RM, Bang KM. Skin cancer in blacks in the United States. Dermatol Clin. 1988;6:397-405.

4. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.009

5. Agbai ON, Buster K, Sanchez M, et al. Skin cancer and photoprotection in people of color: a review and recommendations for physicians and the public. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:748-762. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.038

6. Matsuoka LY, Schauer PK, Sordillo PP. Basal cell carcinoma in black patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:670-672. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(81)70067-7

7. Bigler C, Feldman J, Hall E, et al. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma in Hispanics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:751-752. doi:10.1016/ S0190-9622(96)90007-9

8. Sierro TJ, Blumenthal LY, Hekmatjah J, et al. Differences in health care resource utilization and costs for keratinocyte carcinoma among racioethnic groups: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:373-378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.07.005

A Hispanic male presented with a 3-month history of a spreading, itchy rash

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

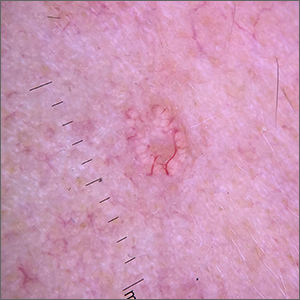

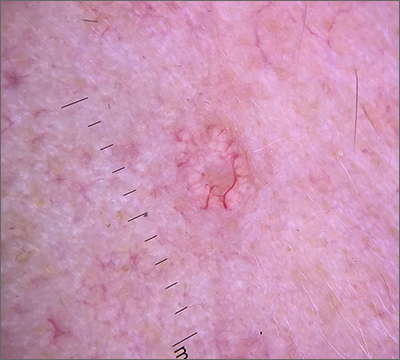

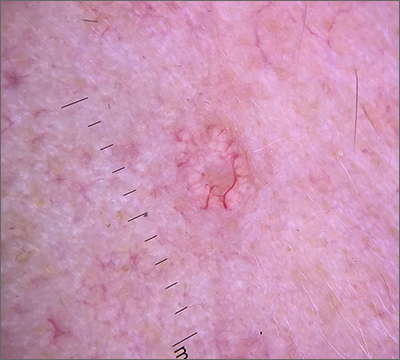

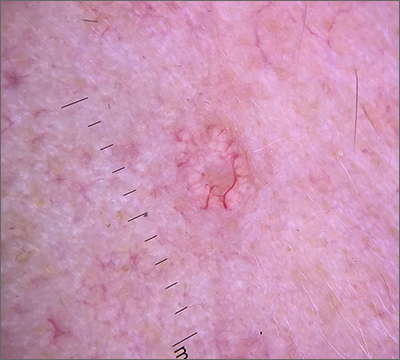

Umbilicated cheek lesion

Dermoscopy revealed multiple small white structures around a central pore and tortuous, but not arborizing, blood vessels around the periphery (frequently called a crown pattern). These features pointed to the diagnosis of sebaceous gland hyperplasia (SGH).

SGH is a common benign condition seen predominantly in middle- to older-age people and patients on immunosuppressant drugs (especially ciclosporin). SGH tends to manifest as multiple lesions on the face and forehead, although the lesions can appear elsewhere.1

As the name implies, SGH is hyperplasia of the sebocytes of the hair follicle, which results in white-to-yellow clusters around the dilated opening of the follicle.1 In contrast to BCCs, which have arborizing blood vessels that can occur throughout the lesion, the vessels in SGH have a lower propensity for branching and tend to follow the periphery instead of crossing into the central pore.2 This characteristic pattern, as well as the appearance of multiple similar lesions elsewhere on a patient’s body, suggests a diagnosis of SGH. If the lesion is atypical, solitary, or has other features that make the diagnosis uncertain, a biopsy is recommended.

SGH is not malignant and is asymptomatic, so treatment is not required. However, the cosmetic appearance can be distressing or undesirable for some patients.1 The most common cosmetic remedies are destructive and include electrodessication, cryosurgery, and treatments with laser and intense pulsed light. Unfortunately, if there is residual tissue after treatment, recurrence is common, and due to the destructive nature of treatment, scarring is possible. It is important to counsel the patient regarding both of these possibilities and to balance the extent of destruction.

In patients with multiple lesions, oral isotretinoin may be used, but SGH will recur if treatment is discontinued. Additionally, isotretinoin, which is also used for cystic acne, is a high-risk medication due its potential to cause fetal anomalies and death if used during pregnancy. Patients usually get cheilitis and dyshidrosis due to its drying effect, but those symptoms are manageable with topical emollients.

This patient declined treatment, as he already had scars from previous NMSCs and was not concerned about the appearance of SGH.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hussein L, Perrett CM. Treatment of sebaceous gland hyperplasia: a review of the literature. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:866-877. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1720582

2. Zaballos P, Ara M, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of sebaceous hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:808. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.808

Dermoscopy revealed multiple small white structures around a central pore and tortuous, but not arborizing, blood vessels around the periphery (frequently called a crown pattern). These features pointed to the diagnosis of sebaceous gland hyperplasia (SGH).

SGH is a common benign condition seen predominantly in middle- to older-age people and patients on immunosuppressant drugs (especially ciclosporin). SGH tends to manifest as multiple lesions on the face and forehead, although the lesions can appear elsewhere.1

As the name implies, SGH is hyperplasia of the sebocytes of the hair follicle, which results in white-to-yellow clusters around the dilated opening of the follicle.1 In contrast to BCCs, which have arborizing blood vessels that can occur throughout the lesion, the vessels in SGH have a lower propensity for branching and tend to follow the periphery instead of crossing into the central pore.2 This characteristic pattern, as well as the appearance of multiple similar lesions elsewhere on a patient’s body, suggests a diagnosis of SGH. If the lesion is atypical, solitary, or has other features that make the diagnosis uncertain, a biopsy is recommended.

SGH is not malignant and is asymptomatic, so treatment is not required. However, the cosmetic appearance can be distressing or undesirable for some patients.1 The most common cosmetic remedies are destructive and include electrodessication, cryosurgery, and treatments with laser and intense pulsed light. Unfortunately, if there is residual tissue after treatment, recurrence is common, and due to the destructive nature of treatment, scarring is possible. It is important to counsel the patient regarding both of these possibilities and to balance the extent of destruction.

In patients with multiple lesions, oral isotretinoin may be used, but SGH will recur if treatment is discontinued. Additionally, isotretinoin, which is also used for cystic acne, is a high-risk medication due its potential to cause fetal anomalies and death if used during pregnancy. Patients usually get cheilitis and dyshidrosis due to its drying effect, but those symptoms are manageable with topical emollients.

This patient declined treatment, as he already had scars from previous NMSCs and was not concerned about the appearance of SGH.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Dermoscopy revealed multiple small white structures around a central pore and tortuous, but not arborizing, blood vessels around the periphery (frequently called a crown pattern). These features pointed to the diagnosis of sebaceous gland hyperplasia (SGH).

SGH is a common benign condition seen predominantly in middle- to older-age people and patients on immunosuppressant drugs (especially ciclosporin). SGH tends to manifest as multiple lesions on the face and forehead, although the lesions can appear elsewhere.1

As the name implies, SGH is hyperplasia of the sebocytes of the hair follicle, which results in white-to-yellow clusters around the dilated opening of the follicle.1 In contrast to BCCs, which have arborizing blood vessels that can occur throughout the lesion, the vessels in SGH have a lower propensity for branching and tend to follow the periphery instead of crossing into the central pore.2 This characteristic pattern, as well as the appearance of multiple similar lesions elsewhere on a patient’s body, suggests a diagnosis of SGH. If the lesion is atypical, solitary, or has other features that make the diagnosis uncertain, a biopsy is recommended.

SGH is not malignant and is asymptomatic, so treatment is not required. However, the cosmetic appearance can be distressing or undesirable for some patients.1 The most common cosmetic remedies are destructive and include electrodessication, cryosurgery, and treatments with laser and intense pulsed light. Unfortunately, if there is residual tissue after treatment, recurrence is common, and due to the destructive nature of treatment, scarring is possible. It is important to counsel the patient regarding both of these possibilities and to balance the extent of destruction.

In patients with multiple lesions, oral isotretinoin may be used, but SGH will recur if treatment is discontinued. Additionally, isotretinoin, which is also used for cystic acne, is a high-risk medication due its potential to cause fetal anomalies and death if used during pregnancy. Patients usually get cheilitis and dyshidrosis due to its drying effect, but those symptoms are manageable with topical emollients.

This patient declined treatment, as he already had scars from previous NMSCs and was not concerned about the appearance of SGH.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hussein L, Perrett CM. Treatment of sebaceous gland hyperplasia: a review of the literature. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:866-877. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1720582

2. Zaballos P, Ara M, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of sebaceous hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:808. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.808

1. Hussein L, Perrett CM. Treatment of sebaceous gland hyperplasia: a review of the literature. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:866-877. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1720582

2. Zaballos P, Ara M, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of sebaceous hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:808. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.808

Hair disorder treatments are evolving

“No matter who the patient is, whether a child, adolescent, or adult, the key to figuring out hair disease is getting a good history,” Maria Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said at the Medscape Live Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

. She also urged physicians and other health care providers to use the electronic medical record and to be thorough in documenting information – noting nutrition, hair care habits, supplement use, and other details.

Lab tests should be selected based on that history, she said. For instance, low iron stores can be associated with hair shedding; and thyroid function studies might be needed.

Other highlights of her presentation included comments on different types of alopecia, and some new treatment approaches:

Androgenetic alopecia. In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2017, all treatments tested (2% and 5% minoxidil in men, 1 mg finasteride in men, 2% minoxidil in women, and low-level laser light therapy in men) were superior to placebo. Several photobiomodulation (PBM) devices (also known as low-level laser light) for home use have been cleared for androgenetic alopecia by the Food and Drug Administration; a clinician’s guide, published in 2018, provides information on these devices.

Hair and hormones. Combination therapy for female-pattern hair loss – low-dose minoxidil and spironolactone – is important to know about, she said, adding there are data from an observational pilot study supporting this treatment. Women should not become pregnant while on this treatment, Dr. Hordinsky cautioned.

PRP (platelet rich plasma). This treatment for hair loss can be costly, she cautioned, as it’s viewed as a cosmetic technique, “but it actually can work rather well.”

Hair regrowth measures. Traditionally, measures center on global assessment, the patient’s self-assessment, investigator assessment, and an independent photo review. Enter the dermatoscope. “We can now get pictures as a baseline. Patients can see, and also see the health of their scalp,” and if treatments make it look better or worse, she noted.

Alopecia areata (AA). Patients and families need to be made aware that this is an autoimmune disease that can recur, and if it does recur, the extent of hair loss is not predictable. According to Dr. Hordinsky, the most widely used tool to halt disease activity has been treatment with a corticosteroid (topical, intralesional, oral, or even intravenous corticosteroids).

Clinical trials and publications from 2018 to 2020 have triggered interest in off-label use and further studies of JAK inhibitors for treating AA, which include baricitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March 2022, results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial found that the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib (50 mg or 20 mg daily, with or without a 200-mg loading dose), was efficacious in adults and adolescents with AA, compared with placebo, with no safety concerns noted. “This looks to be very, very promising,” she said, “and also very safe.” Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib also presented at the same meeting found it was superior to placebo for hair regrowth in adults with severe AA at 36 weeks. (On June 13, shortly after Dr. Hordinsky spoke at the meeting, the FDA approved baricitinib for treating AA in adults, making this the first systemic treatment to be approved for AA).

Research on topical JAK inhibitors for AA has been disappointing, Dr. Hordinsky said.

Alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis. For patients with both AA and AD, dupilumab may provide relief, she said. She referred to a recently published phase 2a trial in patients with AA (including some with both AA and AD), which found that Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores improved after 48 weeks of treatment, with higher response rates among those with baseline IgE levels of 200 IU/mL or higher. “If your patient has both, and their immunoglobulin-E level is greater than 200, then they may be a good candidate for dupilumab and both diseases may respond,” she said.

Scalp symptoms. It can be challenging when patients complain of itch, pain, or burning on the scalp, but have no obvious skin disease, Dr. Hordinsky said. Her tips: Some of these patients may be experiencing scalp symptoms secondary to a neuropathy; others may have mast cell degranulation, but for others, the basis of the symptoms may be unclear. Special nerve studies may be needed. For relief, a trial of antihistamines or topical or oral gabapentin may be needed, she said.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA). This condition, first described in postmenopausal women, is now reported in men and in younger women. While sunscreen has been suspected, there are no good data that have proven that link, she said. Cosmetics are also considered a possible culprit. For treatment, “the first thing we try to do is treat the inflammation,” Dr. Hordinsky said. Treatment options include topical high-potency corticosteroids, intralesional steroids, and topical nonsteroid anti-inflammatory creams (tier 1); hydroxychloroquine, low-dose antibiotics, and acitretin (tier 2); and cyclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil (tier 3).

In an observational study of mostly women with FFA, she noted, treatment with dutasteride was more effective than commonly used systemic treatments.

“Don’t forget to address the psychosocial needs of the hair loss patient,” Dr. Hordinsky advised. “Hair loss patients are very distressed, and you have to learn how to be fast and nimble and address those needs.” Working with a behavioral health specialist or therapist can help, she said.

She also recommended directing patients to appropriate organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation, as well as conferences, such as the upcoming NAAF conference in Washington. “These organizations do give good information that should complement what you are doing.”

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Hordinsky reported no disclosures.

“No matter who the patient is, whether a child, adolescent, or adult, the key to figuring out hair disease is getting a good history,” Maria Hordinsky, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, said at the Medscape Live Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

. She also urged physicians and other health care providers to use the electronic medical record and to be thorough in documenting information – noting nutrition, hair care habits, supplement use, and other details.

Lab tests should be selected based on that history, she said. For instance, low iron stores can be associated with hair shedding; and thyroid function studies might be needed.

Other highlights of her presentation included comments on different types of alopecia, and some new treatment approaches:

Androgenetic alopecia. In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2017, all treatments tested (2% and 5% minoxidil in men, 1 mg finasteride in men, 2% minoxidil in women, and low-level laser light therapy in men) were superior to placebo. Several photobiomodulation (PBM) devices (also known as low-level laser light) for home use have been cleared for androgenetic alopecia by the Food and Drug Administration; a clinician’s guide, published in 2018, provides information on these devices.

Hair and hormones. Combination therapy for female-pattern hair loss – low-dose minoxidil and spironolactone – is important to know about, she said, adding there are data from an observational pilot study supporting this treatment. Women should not become pregnant while on this treatment, Dr. Hordinsky cautioned.

PRP (platelet rich plasma). This treatment for hair loss can be costly, she cautioned, as it’s viewed as a cosmetic technique, “but it actually can work rather well.”

Hair regrowth measures. Traditionally, measures center on global assessment, the patient’s self-assessment, investigator assessment, and an independent photo review. Enter the dermatoscope. “We can now get pictures as a baseline. Patients can see, and also see the health of their scalp,” and if treatments make it look better or worse, she noted.

Alopecia areata (AA). Patients and families need to be made aware that this is an autoimmune disease that can recur, and if it does recur, the extent of hair loss is not predictable. According to Dr. Hordinsky, the most widely used tool to halt disease activity has been treatment with a corticosteroid (topical, intralesional, oral, or even intravenous corticosteroids).

Clinical trials and publications from 2018 to 2020 have triggered interest in off-label use and further studies of JAK inhibitors for treating AA, which include baricitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib. At the American Academy of Dermatology meeting in March 2022, results of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial found that the JAK inhibitor ritlecitinib (50 mg or 20 mg daily, with or without a 200-mg loading dose), was efficacious in adults and adolescents with AA, compared with placebo, with no safety concerns noted. “This looks to be very, very promising,” she said, “and also very safe.” Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib also presented at the same meeting found it was superior to placebo for hair regrowth in adults with severe AA at 36 weeks. (On June 13, shortly after Dr. Hordinsky spoke at the meeting, the FDA approved baricitinib for treating AA in adults, making this the first systemic treatment to be approved for AA).

Research on topical JAK inhibitors for AA has been disappointing, Dr. Hordinsky said.

Alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis. For patients with both AA and AD, dupilumab may provide relief, she said. She referred to a recently published phase 2a trial in patients with AA (including some with both AA and AD), which found that Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores improved after 48 weeks of treatment, with higher response rates among those with baseline IgE levels of 200 IU/mL or higher. “If your patient has both, and their immunoglobulin-E level is greater than 200, then they may be a good candidate for dupilumab and both diseases may respond,” she said.

Scalp symptoms. It can be challenging when patients complain of itch, pain, or burning on the scalp, but have no obvious skin disease, Dr. Hordinsky said. Her tips: Some of these patients may be experiencing scalp symptoms secondary to a neuropathy; others may have mast cell degranulation, but for others, the basis of the symptoms may be unclear. Special nerve studies may be needed. For relief, a trial of antihistamines or topical or oral gabapentin may be needed, she said.