User login

Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma of the External Auditory Canal

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

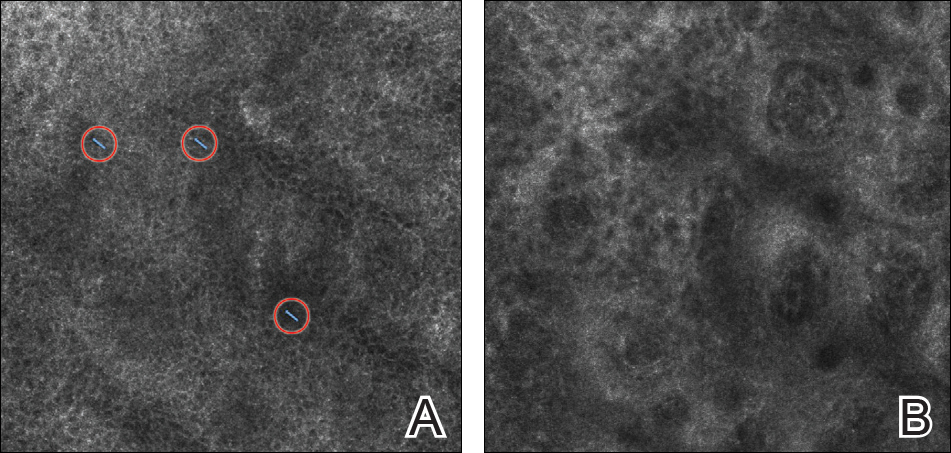

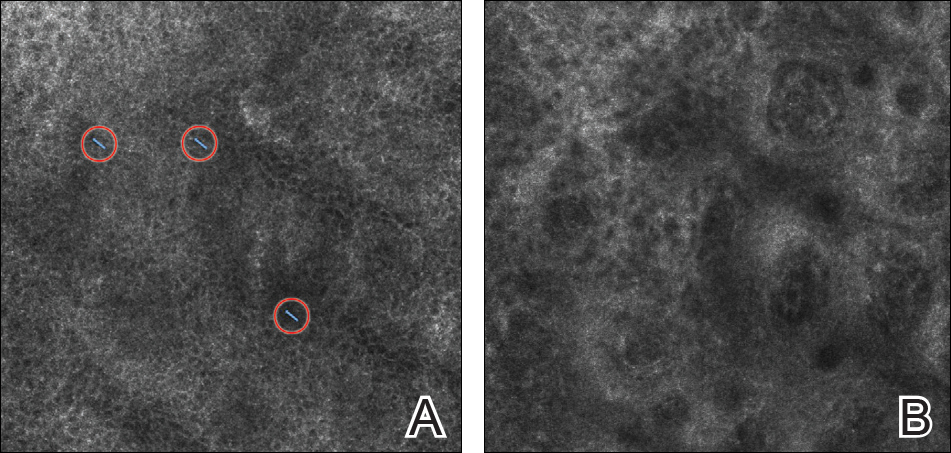

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

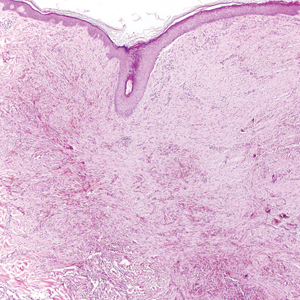

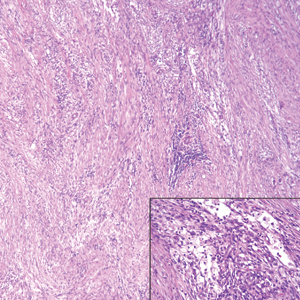

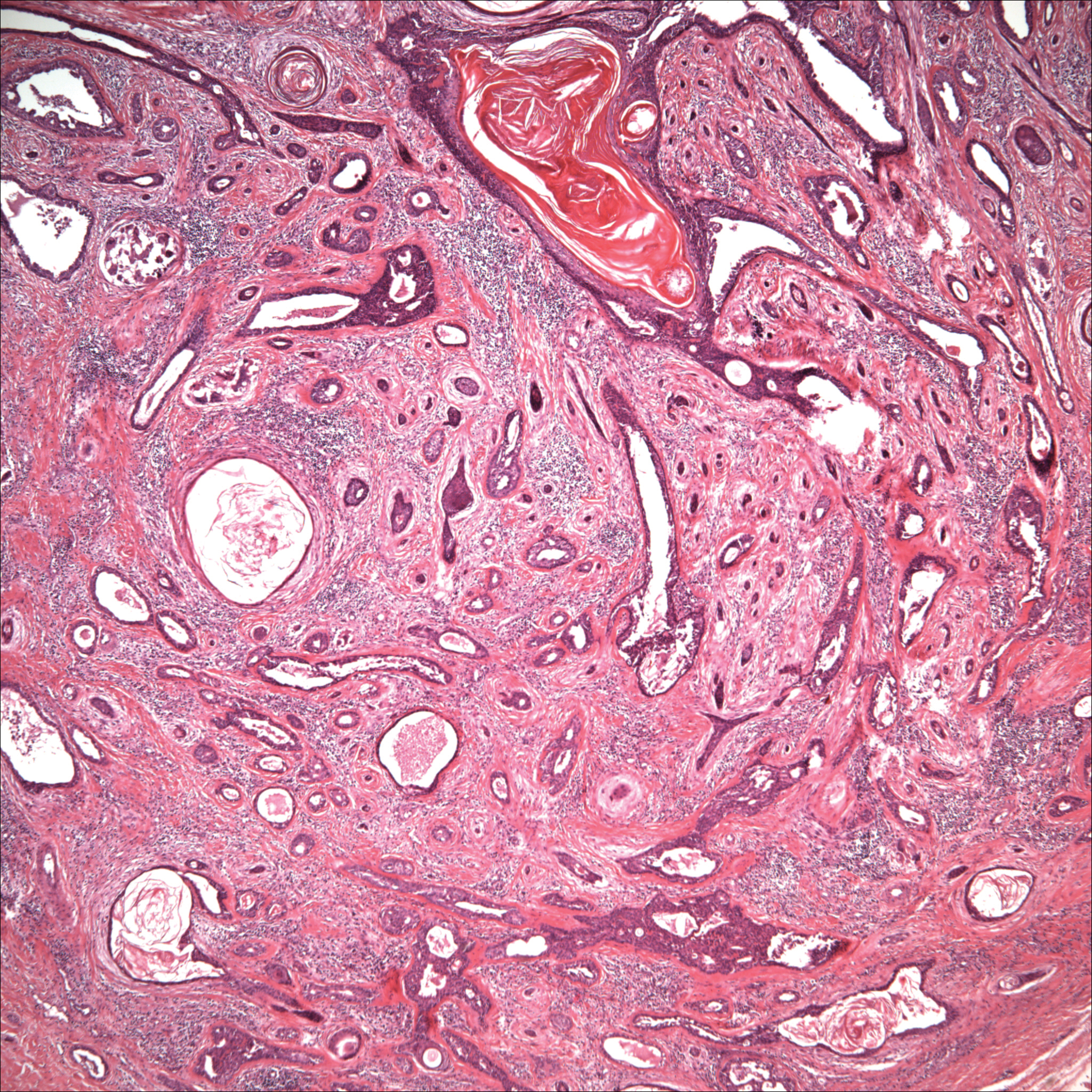

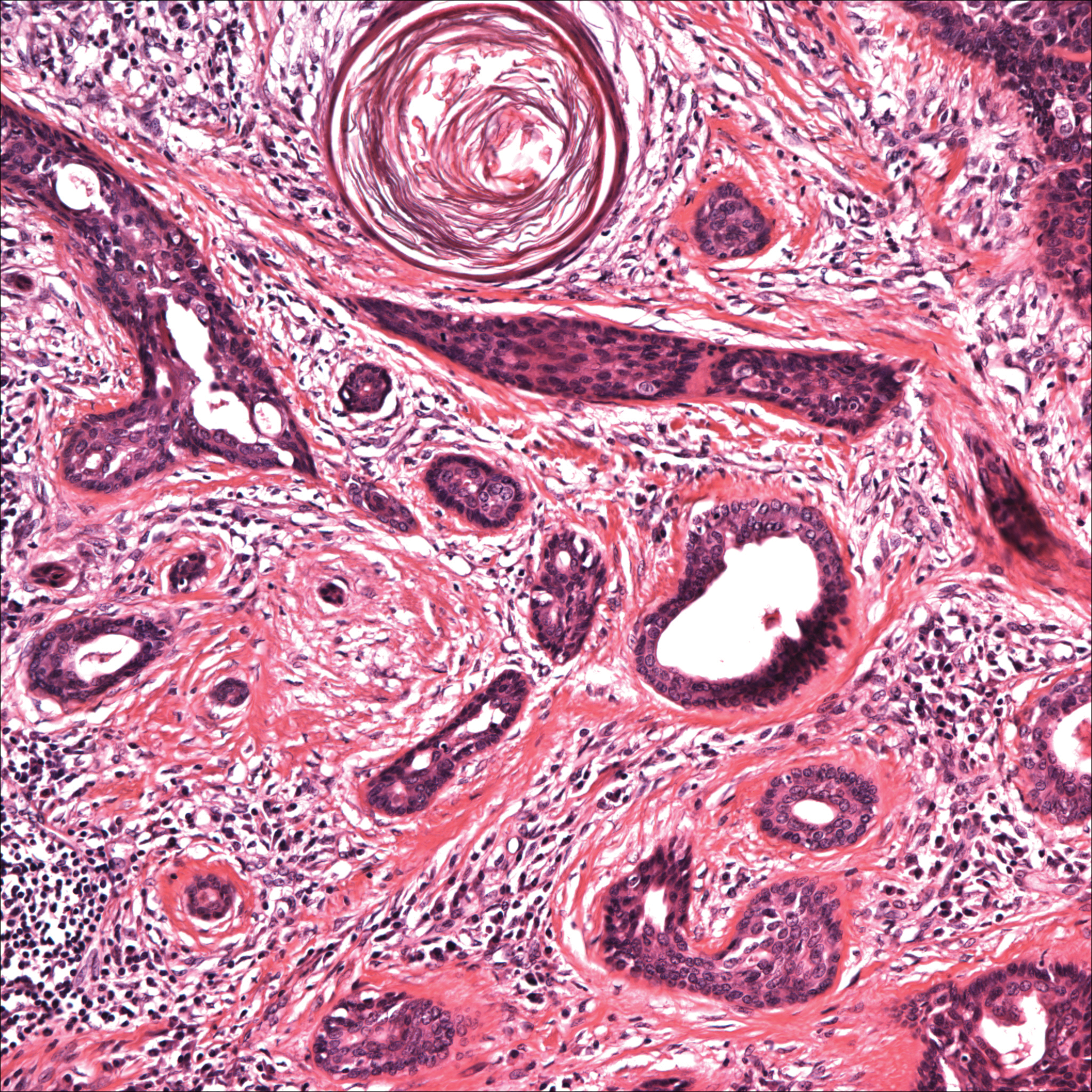

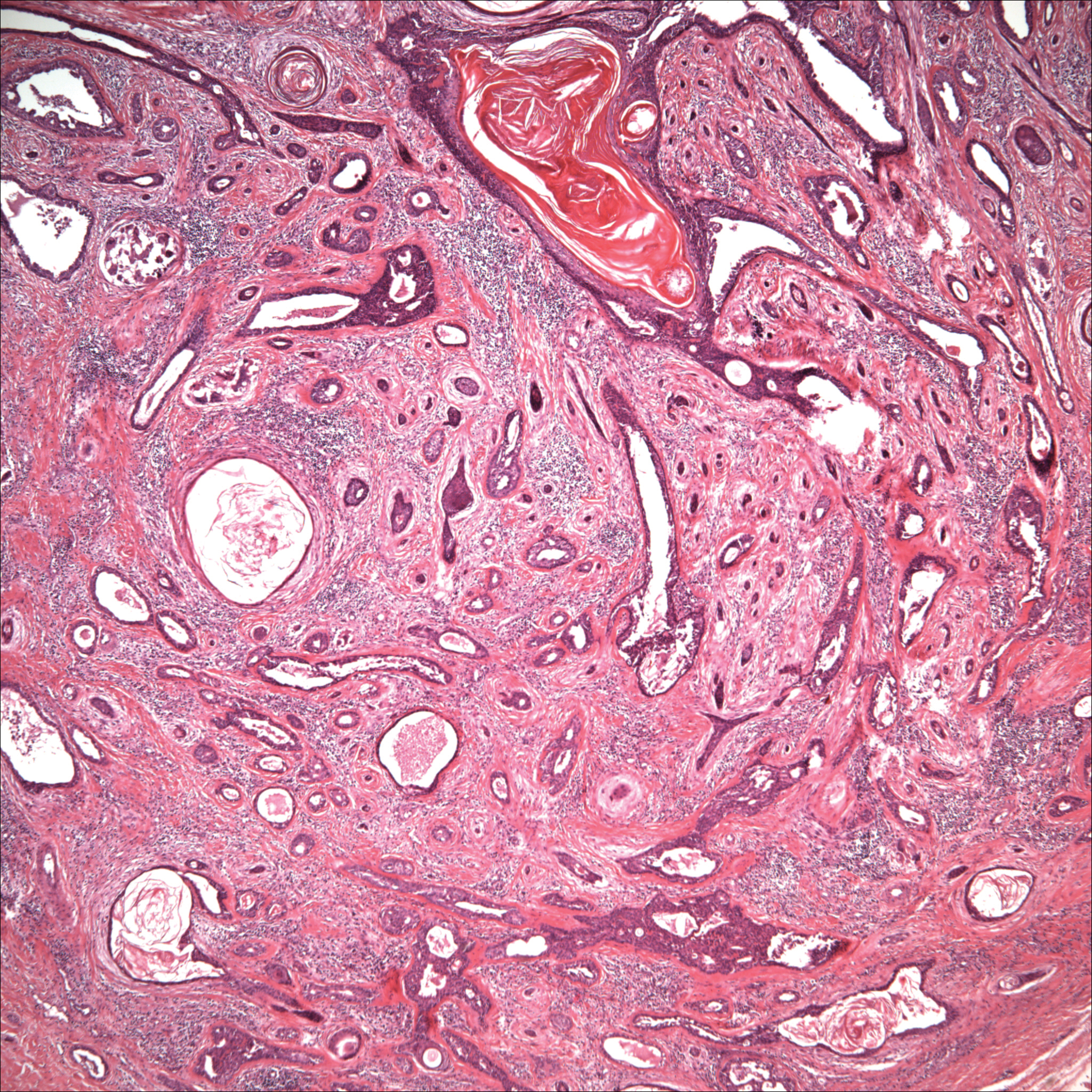

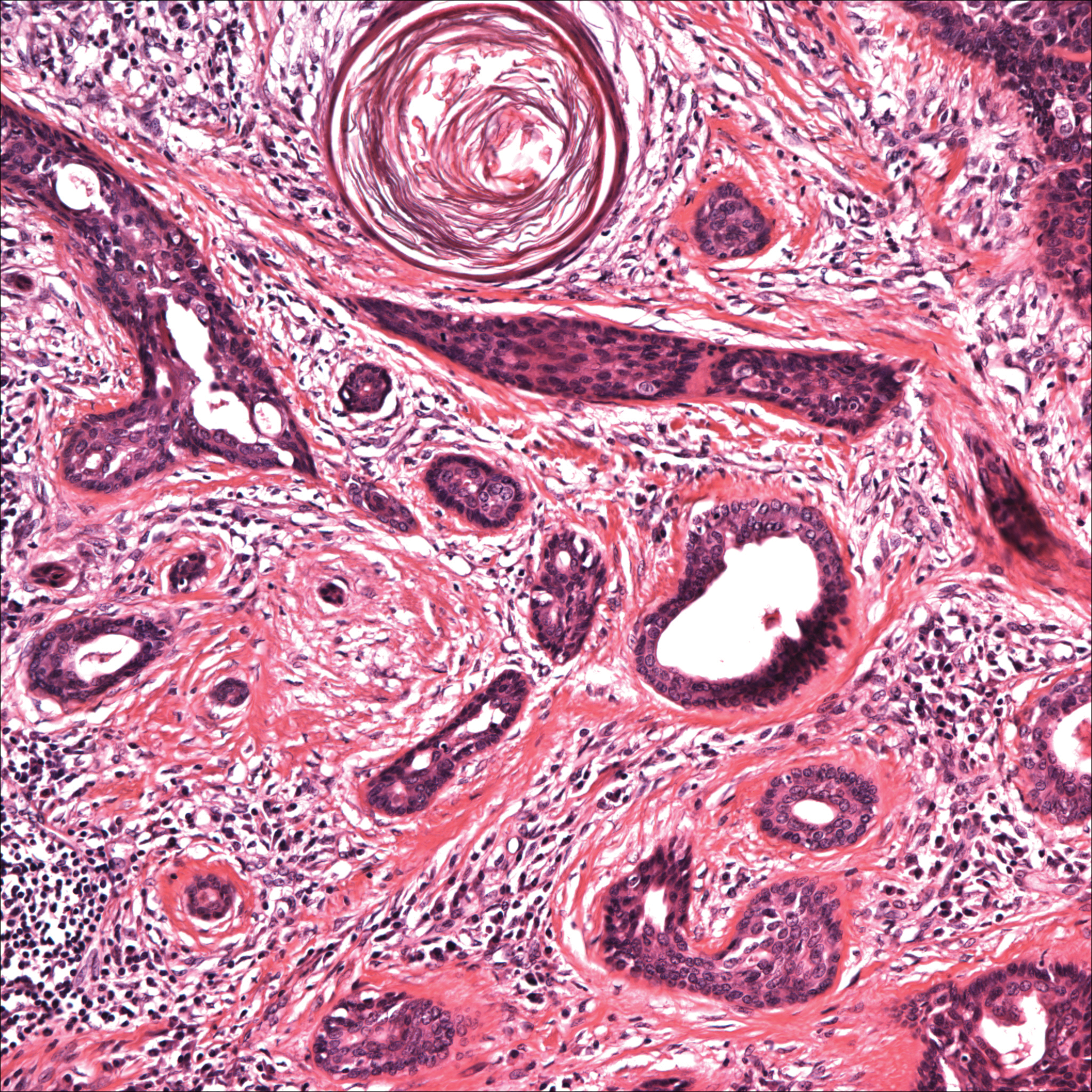

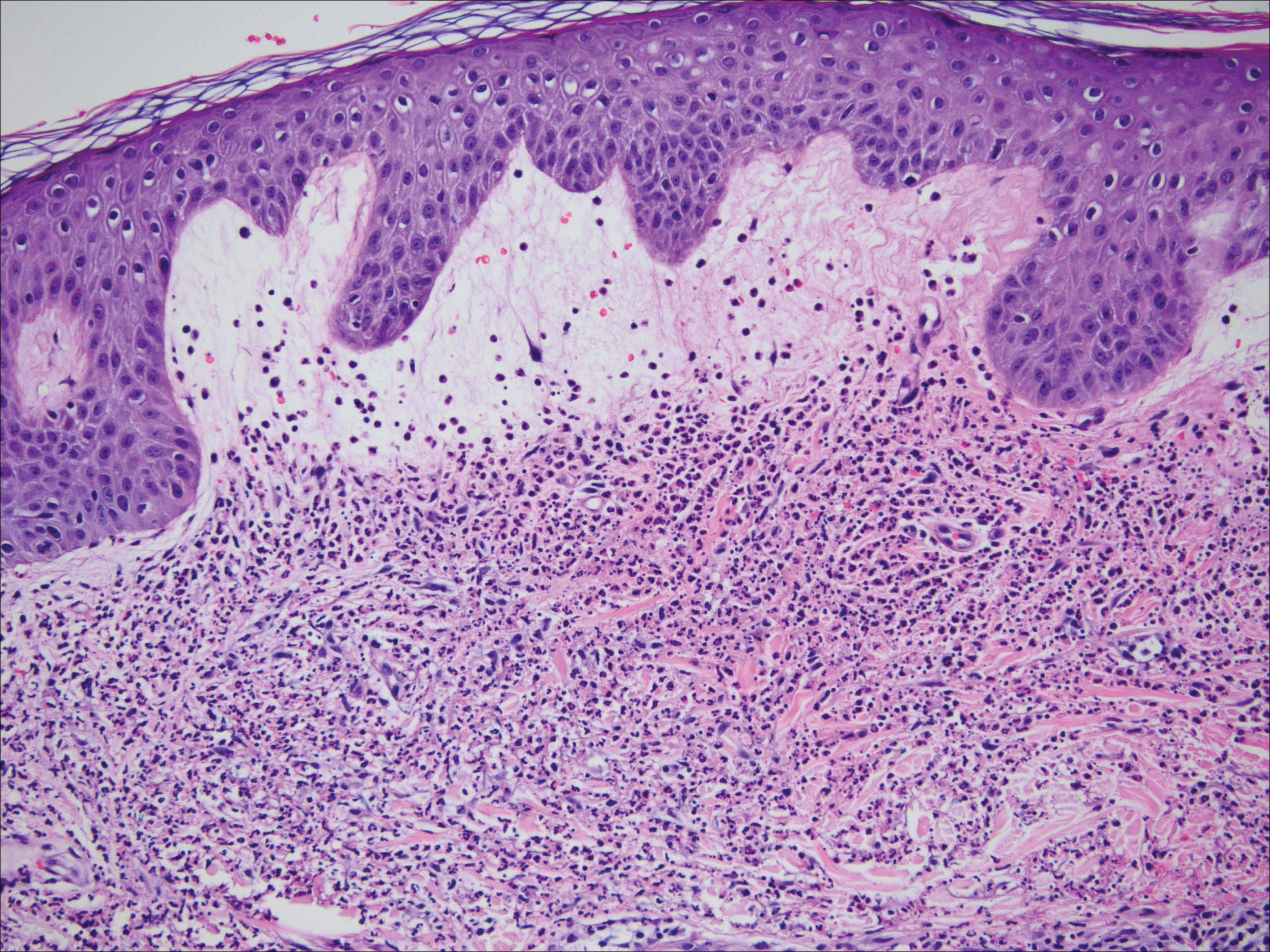

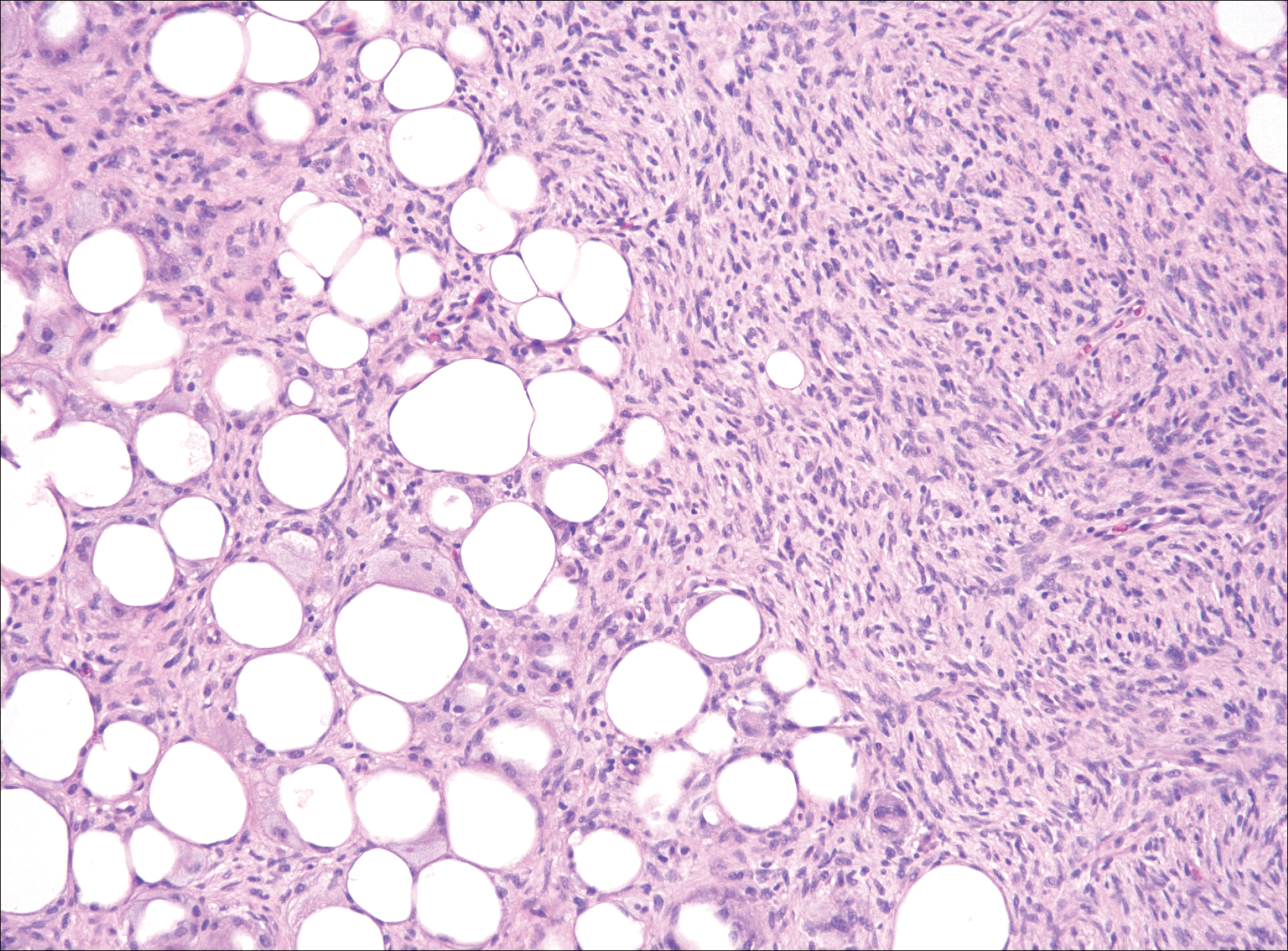

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

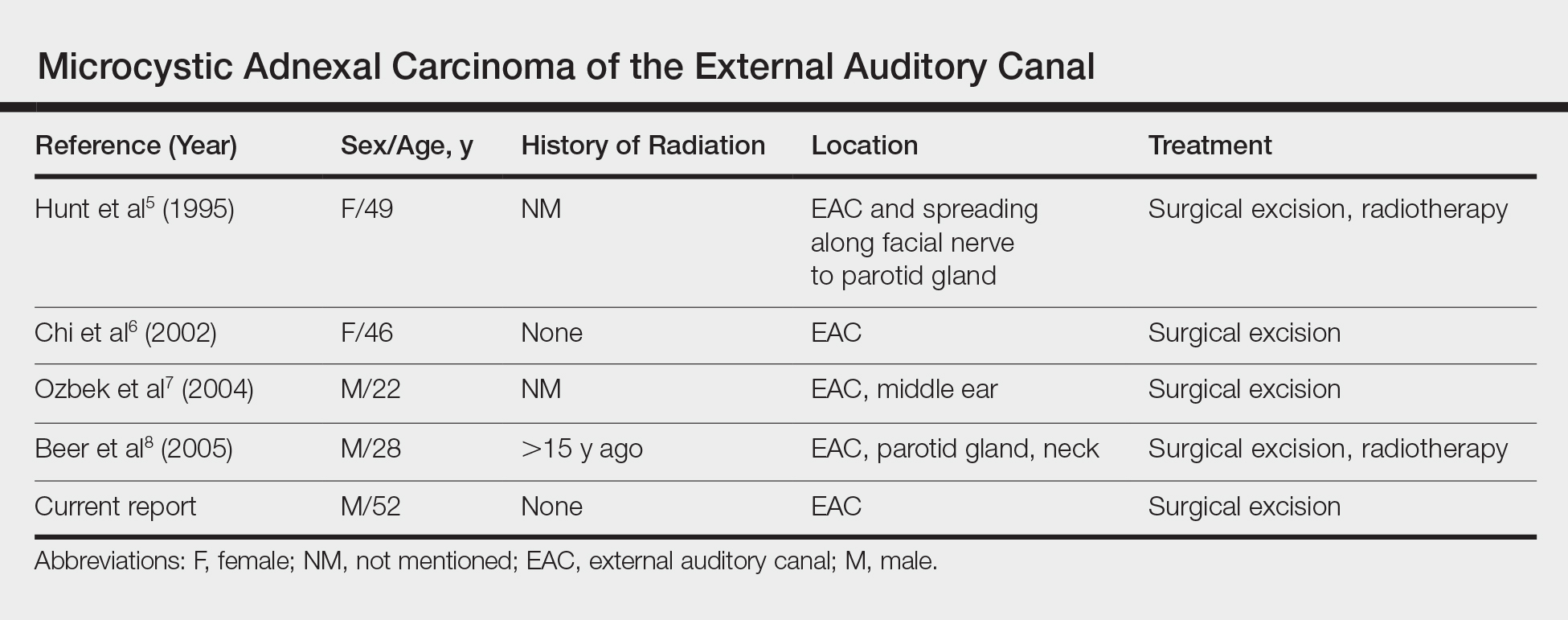

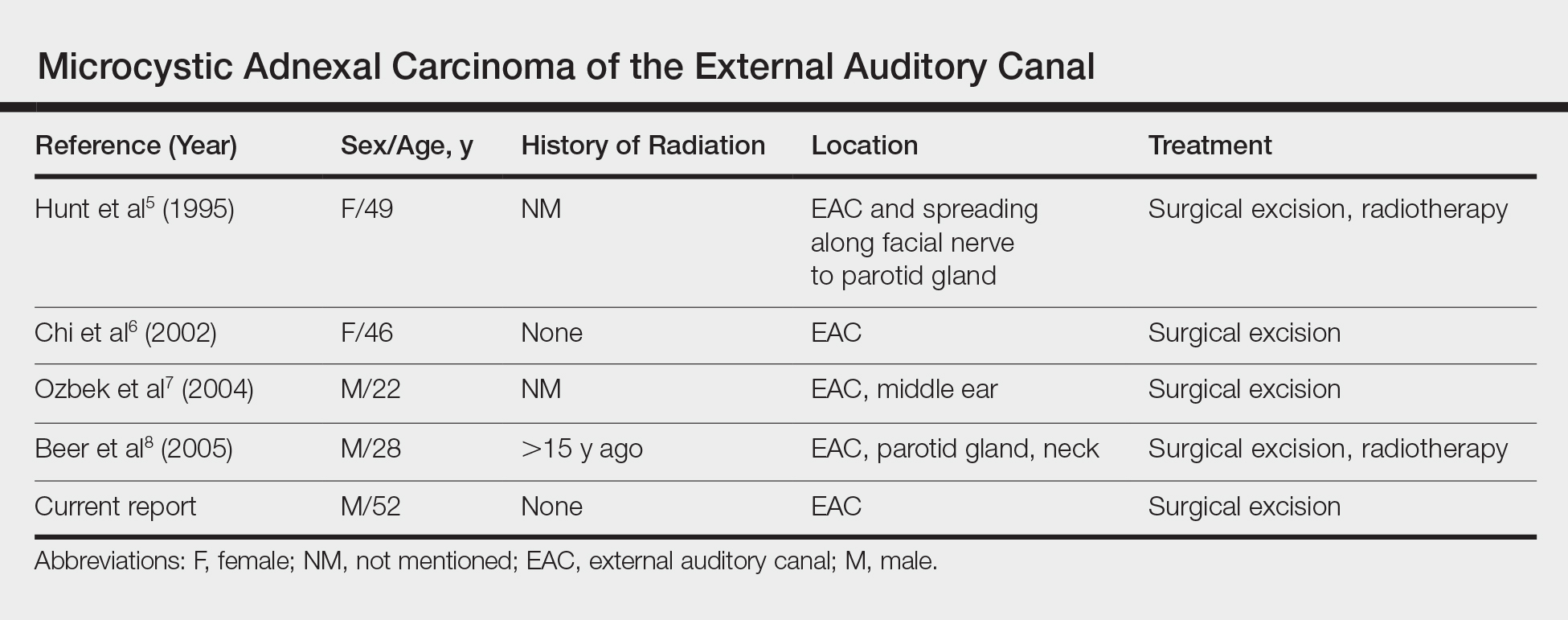

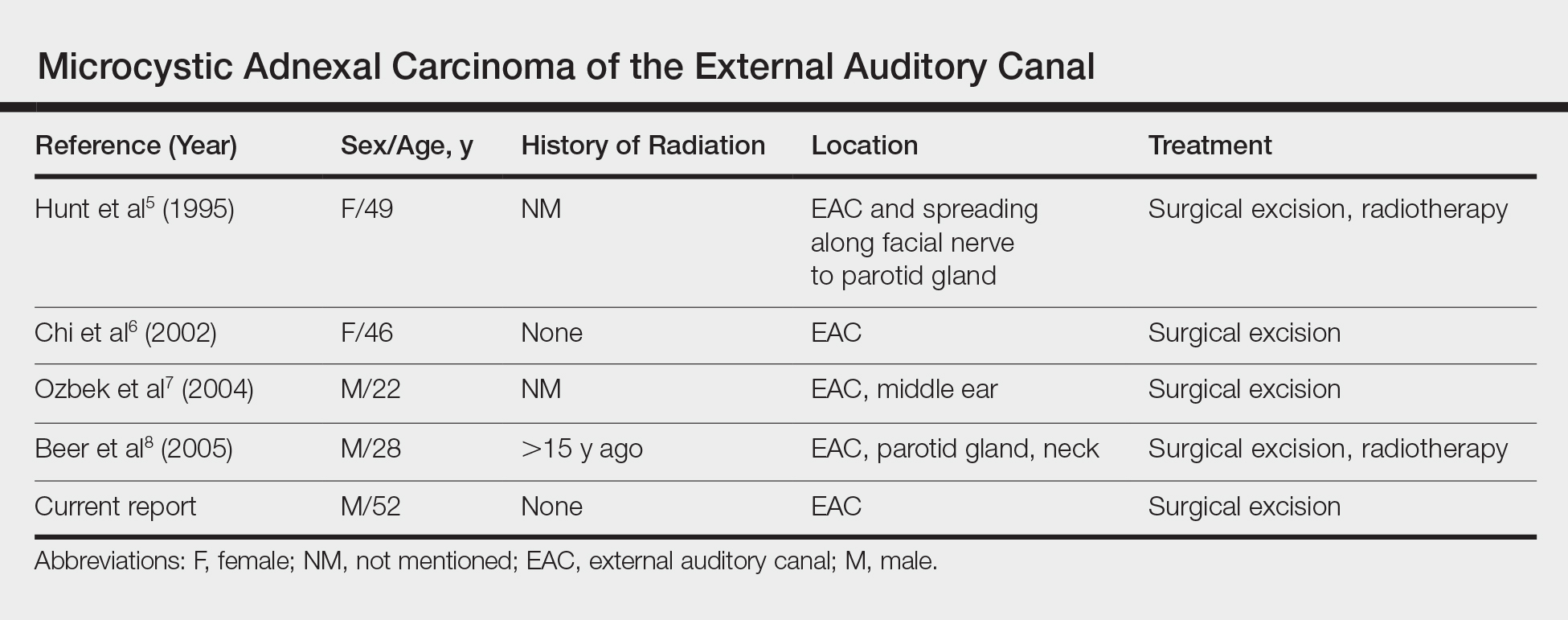

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

To the Editor:

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), described by Goldstein et al1 in 1982, is a relatively uncommon cutaneous neoplasm. This locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor has high potential for local recurrence. The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.2 Involvement of the external auditory canal (EAC) is relatively rare. We report a case of MAC of the EAC.

A 52-year-old man presented with 1 palpable nodule on the right EAC of approximately 1 year’s duration. The lesion was asymptomatic, and the patient had no history of radiation exposure. The patient was an airport employee required to wear an earplug in the right ear. Endoscopic examination identified a 1×1 cm2 erythematous nodule on the anterior inferior quadrant of the right external ear canal orifice (Figure 1). Axial and coronal computed tomography demonstrated a soft tissue mass in the right EAC without any bony erosion. No clinical signs of regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis were present. Excision was performed under microscopic visualization.

Histopathology of the nodule showed marked proliferation of multiple keratin-containing cysts, irregular ductal structures, and solid epithelial nests in the deep dermis (Figure 2). Irregular ductal structures with 2 cell layer walls and several epithelial strands or small nests of tumor cells within desmoplastic stroma were noted (Figure 3). No perineural infiltration or tumor infiltration existed at the margin. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the final diagnosis was MAC. Complete resolution was noted after the excision. The patient returned for regular follow-up and no signs of recurrence were noted for 7 years postoperatively.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma, also known as sclerosing sweat duct (syringomatous) carcinoma, malignant syringoma, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma, is characterized by slow and locally aggressive growth with high likelihood of perineural invasion and frequent recurrence.2 Regional lymph node metastasis is uncommon, and systemic metastasis is rare.2-4

Although the head most often is involved, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms microcystic adnexal carcinoma and external auditory canal revealed 4 cases (Table).5-8 Our report adds another case of MAC arising solely in the EAC. Although the etiology of MAC is unknown, prior studies indicated that radiotherapy is a risk factor for MAC. Other possible risk factors include UV light exposure and immunodeficiency.2 Our patient had no history of these factors and experienced chronic friction caused by use of an occupational unilateral earplug, which may be a notable factor. Locations of MAC arising outside the head region include the axilla, vulva, breast, palm, toe, perianal skin, buttock, chest, and an ovarian cystic teratoma.3,9 Friction commonly occurs in many of these areas. Therefore, we propose that friction may be a risk factor for MAC.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any slowly growing cutaneous tumor, even in the EAC. Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence signs is essential.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Brenn T, Mckee PH. Tumors of the sweat glands. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1647-1651.

- Ohtsuka H, Nagamatsu S. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of 51 Japanese patients. Dermatology. 2002;204:190-193.

- Yu JB, Blitzblau RC, Patel SC, et al. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma) of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:125-127.

- Hunt JT, Stack BC Jr, Futran ND, et al. Pathologic quiz case 1. microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:1430-1433.

- Chi J, Jung YG, Rho YS, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of external auditory canal: report of a case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:241-242.

- Ozbek C, Celikkanat S, Beriat K, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the external ear canal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:148-150.

- Beer KT, Bühler SS, Mullis P, et al. A microcystic adnexal carcinoma in the auditory canal 15 years after radiotherapy of a 12-year-old boy with nasopharynx carcinoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:405-410.

- Nadiminti H, Nadiminti U, Washington C. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma in African Americans. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1384-1387.

Practice Points

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive malignant adnexal tumor with a high potential for local recurrence.

- The skin of the head, particularly in the nasolabial and periorbital regions, most often is involved.

- Once diagnosed, the tumor should be surgically excised. Because local recurrence is common and may occur several decades after excision, lifetime follow-up for recurrence is essential.

Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus Responsive to 308-nm Excimer Laser Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

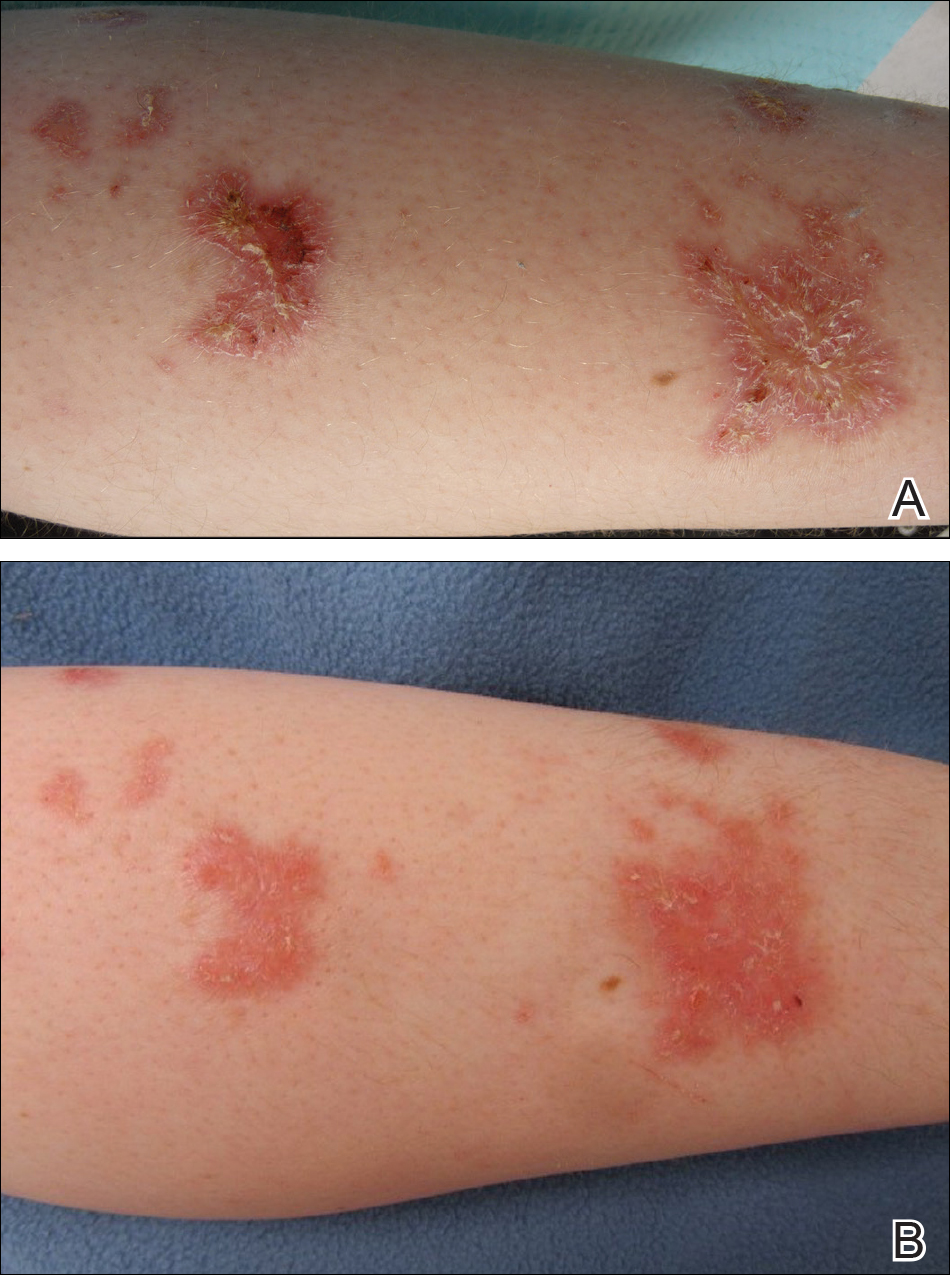

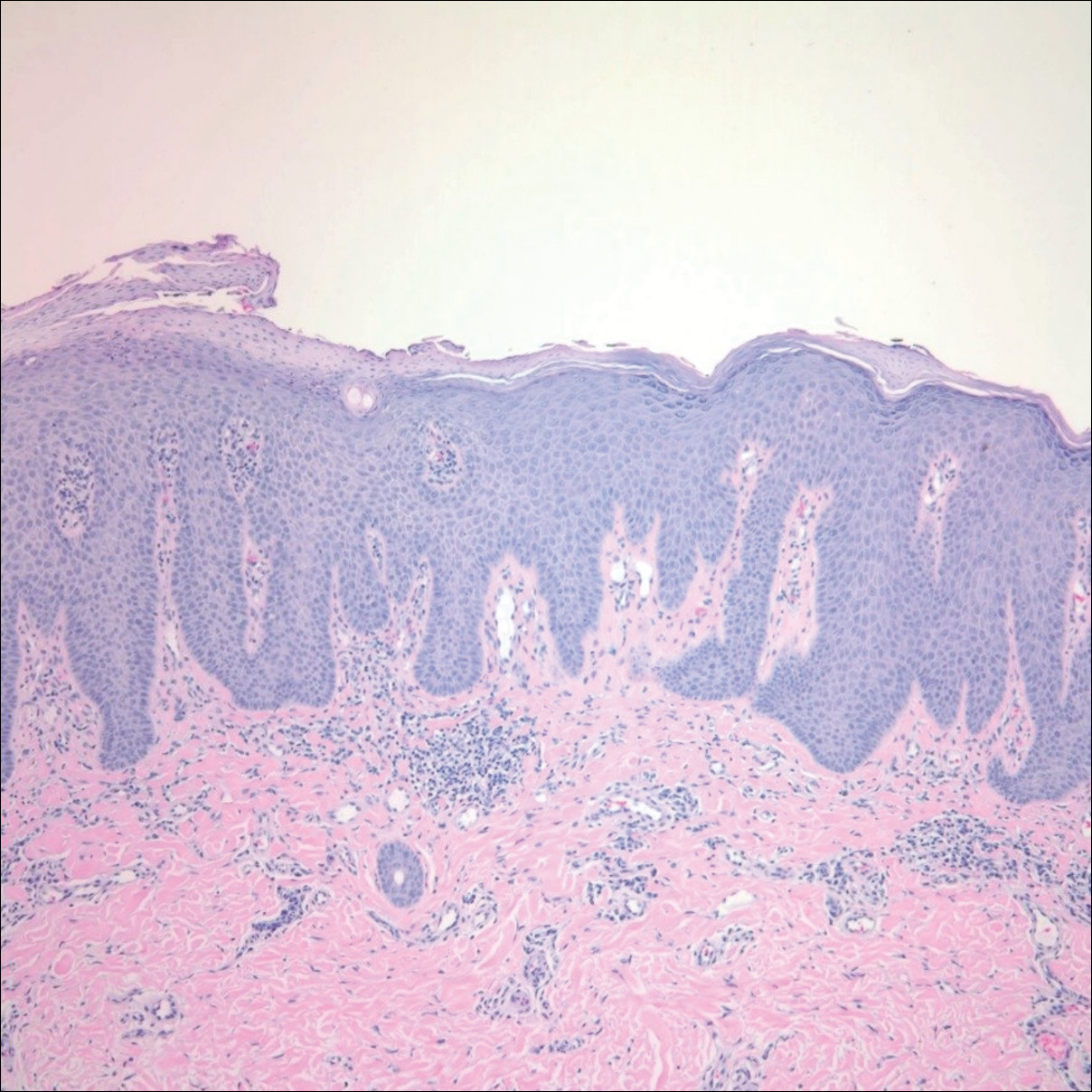

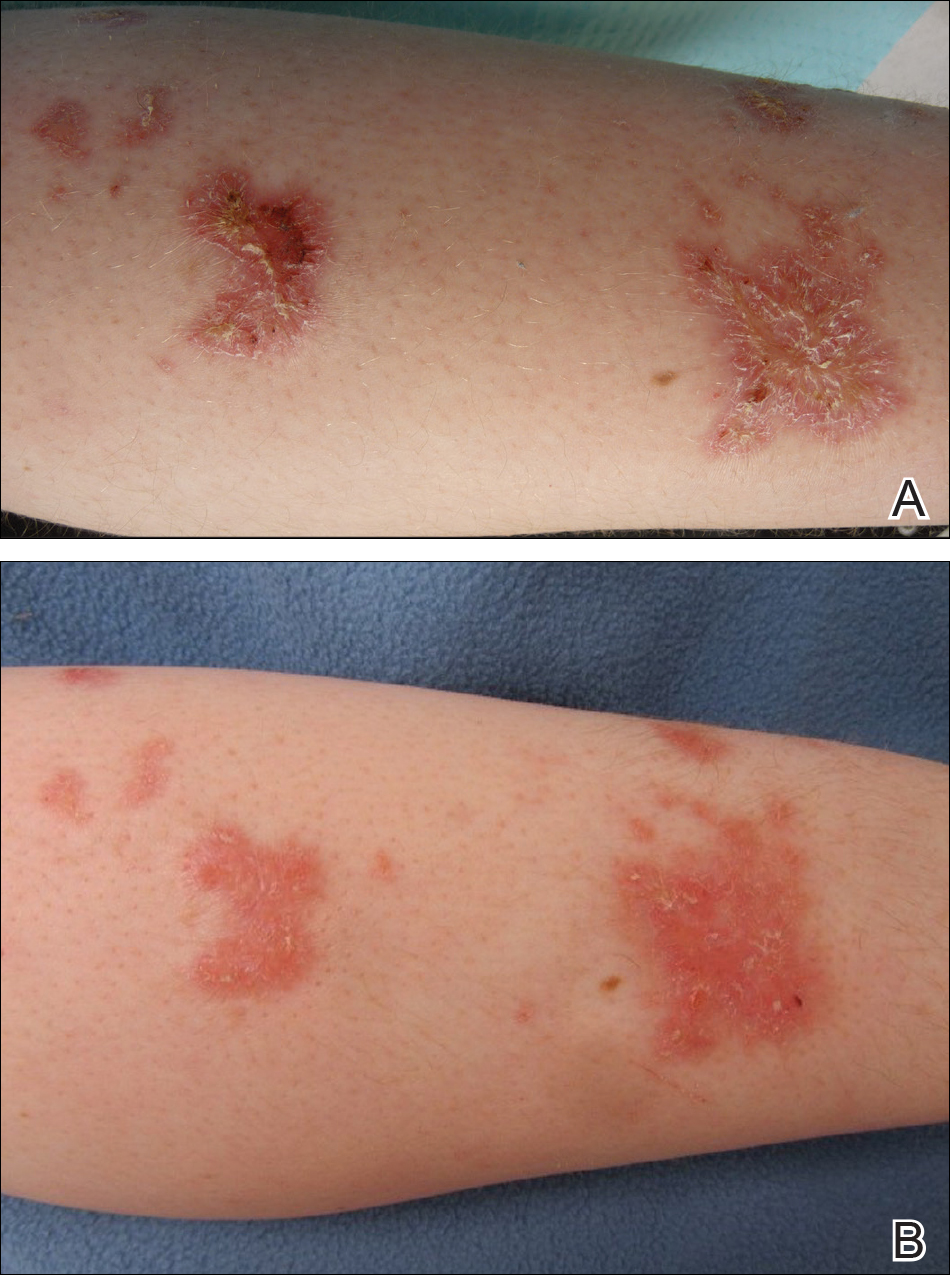

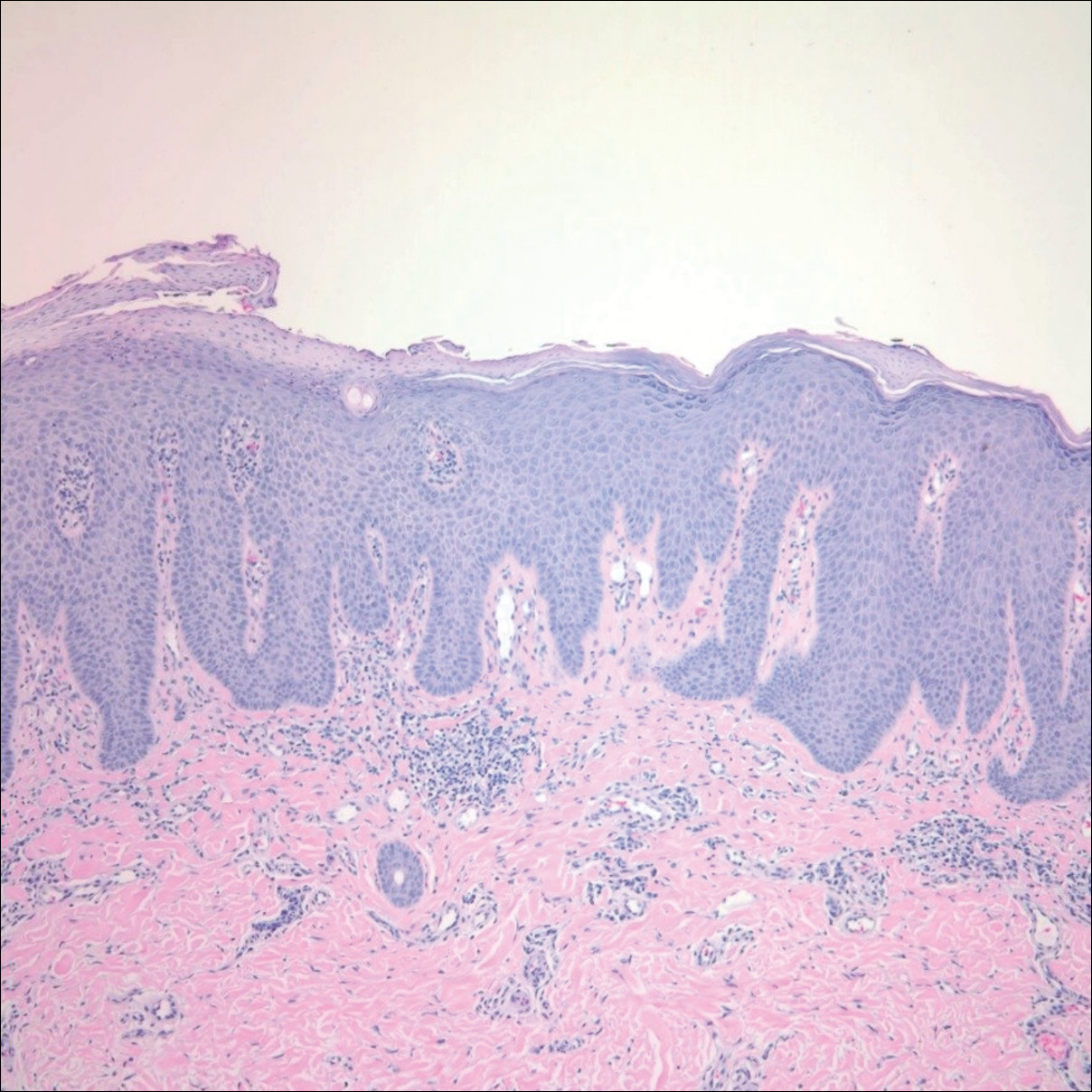

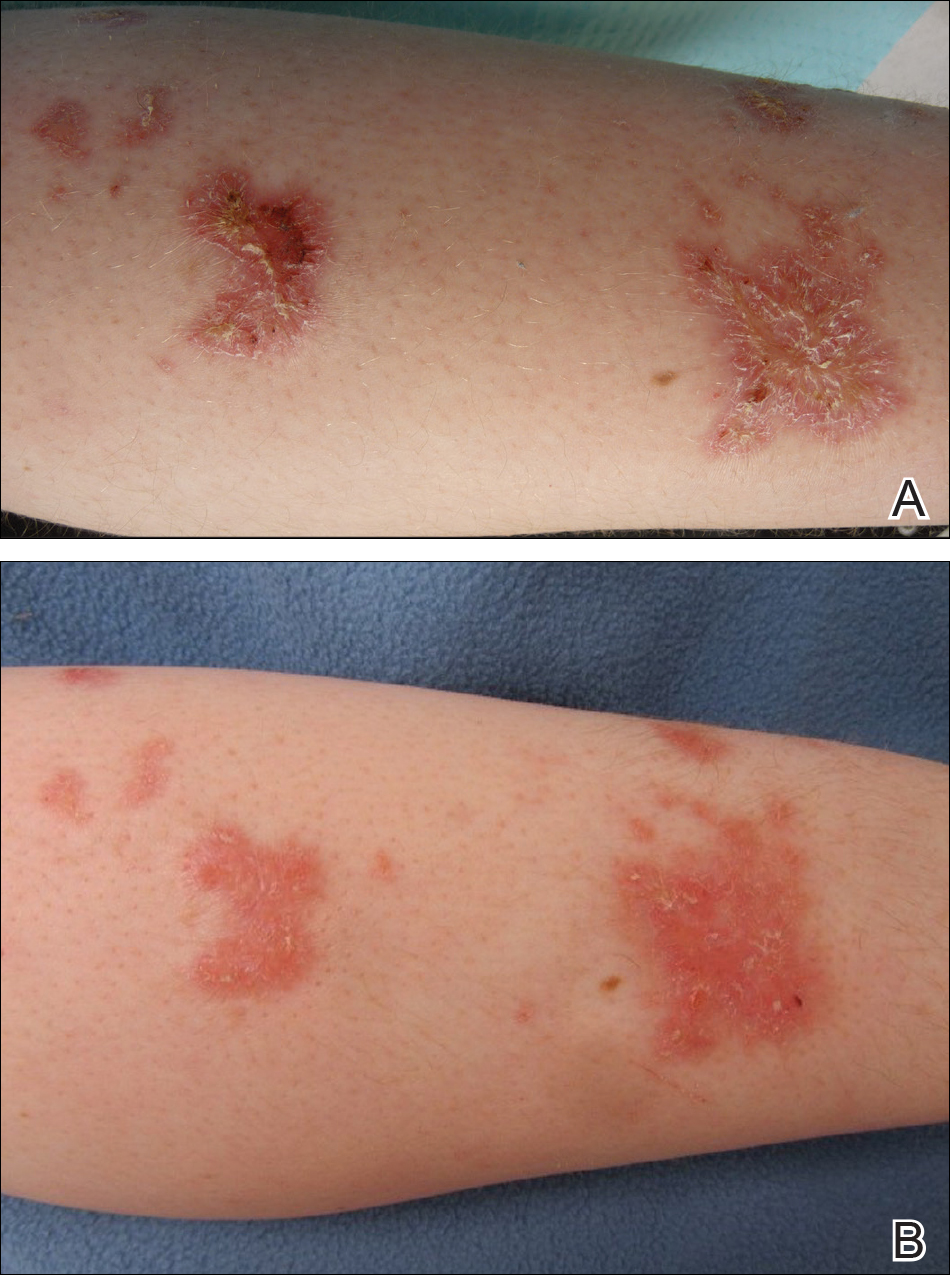

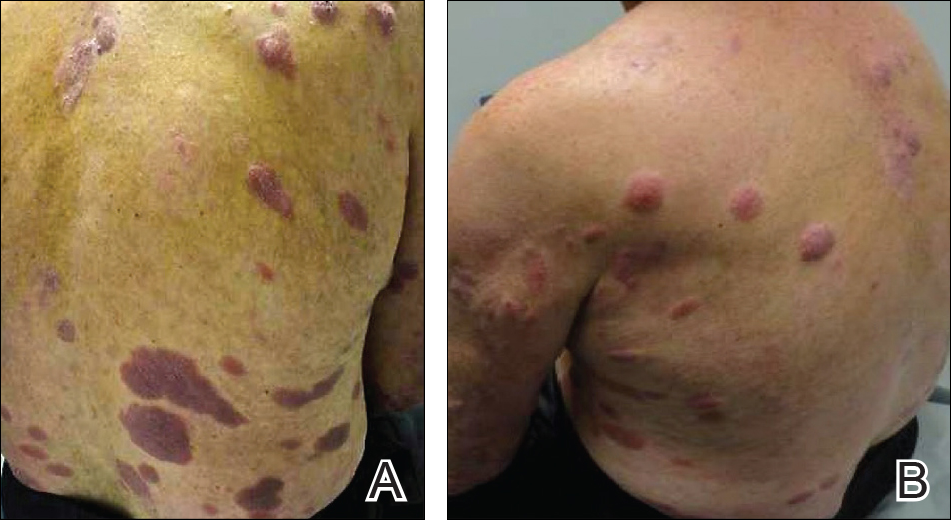

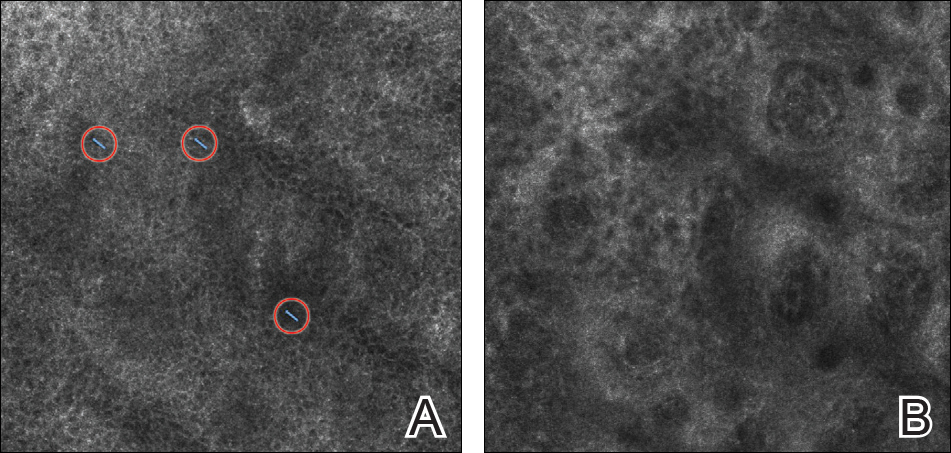

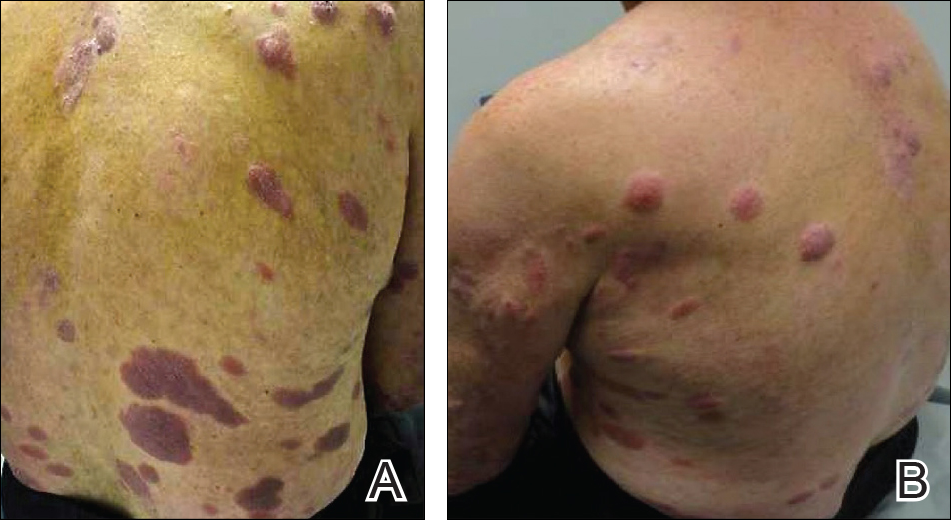

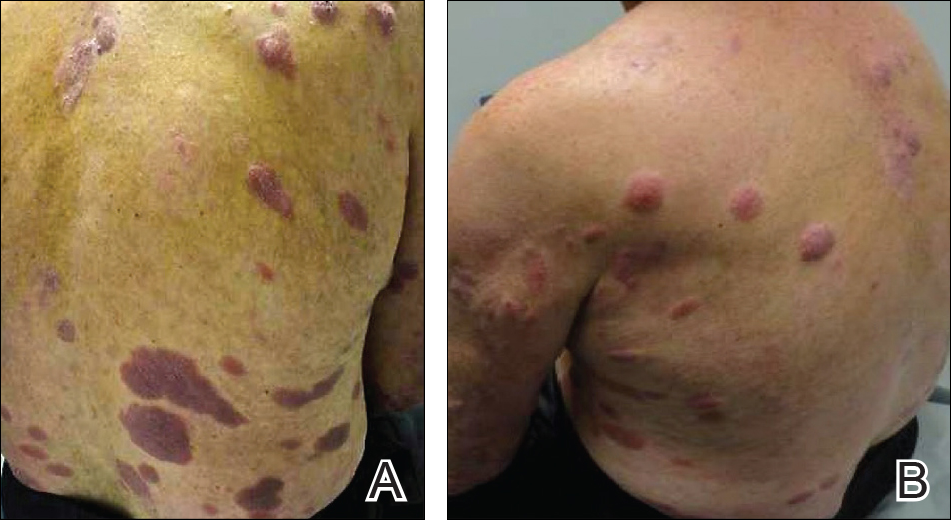

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26

The CO2 laser also has demonstrated success. One study showed considerable improvement of pruritus and partial resolution of lesions only 5 weeks following a single CO2 laser treatment.5 Another study showed promising results when combining CO2 pulsed laser therapy with fractional CO2 laser treatment.6 Other laser therapies including the argon27 and flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye lasers8 have been used with limited success. The use of light therapy and lasers in psoriasis have now increased the treatment options for ILVEN based on the rationale of their shared histopathologic characteristics. Photodynamic therapy also has been attempted because of its successful use in psoriasis patients. It has been found to be successful in diminishing ILVEN lesions and associated pruritus after a few weeks of therapy; however, treatment is limited by the associated pain and requirement for local anesthesia.28

The excimer laser is a form of targeted phototherapy that emits monochromatic light at 308 nm.29 It is ideal for inflammatory skin lesions because the UVB light induces apoptosis.30 Psoriasis lesions treated with the excimer laser show a decrease in keratinocyte proliferation, which in turn reverses epidermal acanthosis and causes T-cell depletion due to upregulation of p53.29,31 This mechanism of action addresses the overproliferation of keratinocytes mediated by T cells in psoriasis and contributes to the success of excimer laser treatment.31 A considerable advantage is its localized treatment, resulting in lower cumulative doses of UVB and reducing the possible carcinogenic and phototoxic risks of whole-body phototherapy.32

One study examined the antipruritic effects of the excimer laser following the treatment of epidermal hyperinnervation leading to intractable pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers suggested that a potential explanation for the antipruritic effect of the excimer laser may be secondary to nerve degeneration.33 Additionally, low doses of UVB light also may inhibit mast cell degranulation and prevent histamine release, further supporting the antipruritic properties of excimer laser.34

In our patient, failed treatment with other modalities led to trial of excimer laser therapy because of the overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with psoriasis. Excimer laser improved the clinical appearance and overall texture of the ILVEN lesions and decreased pruritus. The reasons for treatment success may be two-fold. By decreasing the number of keratinocytes and mast cells, the excimer laser may have improved the epidermal hyperplasia and pruritus in the ILVEN lesions. Alternatively, because the patient had ILVEN lesions since infancy, psoriasis may have developed in the location of the ILVEN lesions due to koebnerization, resulting in the clinical response to excimer therapy; however, she had no other clinical evidence of psoriasis.

Because of the recalcitrance of ILVEN lesions to conventional therapies, it is important to investigate therapies that may be of possible benefit. Our novel case documents successful use of the excimer laser in the treatment of ILVEN.

Conclusion

Our case of ILVEN in a woman that had been present since infancy highlights the disease pathology as well as a potential new treatment modality. The patient was refractory to first-line treatments and was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient was subsequently treated with a trial of a 308-nm excimer laser with clinical improvement of the lesions. It is possible that the similarity of ILVEN and psoriasis may have contributed to the clinical improvement in our patient, but the mechanism of action remains unknown. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding optimal treatment of ILVEN, the current case offers dermatologists an option for patients who are refractory to other treatments.

- Altman J, Mehregan AH. Inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:385-389.

- Hofer T. Does inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus represent a segmental type 1/type 2 mosaic of psoriasis? Dermatology. 2006;212:103-107.

- Rogers M, McCrossin I, Commens C. Epidermal nevi and the epidermal nevus syndrome: a review of 131 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:476-488.

- Khachemoune A, Janjua S, Guldbakke K. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report and short review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:261-267.

- Ulkur E, Celikoz B, Yuksel F, et al. Carbon dioxide laser therapy for an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:428-430.

- Conti R, Bruscino N, Campolmi P, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: why a combined laser therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:242-245.

- Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-918.

- Alster TS. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successful treatment with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:513-514.

- Kruse LL. Differential diagnosis of linear eruptions in children. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:194-198.

- Renner R, Colsman A, Sticherling M. ILVEN: is it psoriasis? debate based on successful treatment with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:631-632.

- Lee SH, Rogers M. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevi: a review of 23 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:252-256.

- Ito M, Shimizu N, Fujiwara H, et al. Histopathogenesis of inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus: histochemistry, immunohistochemistry and ultrastructure. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:491-499.

- Cerio R, Jones EW, Eady RA. ILVEN responding to occlusive potent topical steroid therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:279-281.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Vissers WH, Muys L, Erp PE, et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation between ILVEN and psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:216-220.

- Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Gupta R, et a. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with psoriasiform histology. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:211.

- Bennett RG, Burns L, Wood MG. Systematized epidermal nevus: a determinant for the localization of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:705-757.

- Tran K, Jao-Tan C, Ho N. ILVEN and psoriasis: a retrospective study among pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB163.

- Happle R. Superimposed linear psoriasis: a historical case revisited. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1027-1028; discussion 1029.

- Özdemir M, Balevi A, Esen H. An inflammatory verrucous epidermal nevus concomitant with psoriasis: treatment with adalimumab. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Zvulunov A, Grunwald MH, Halvy S. Topical calcipotriol for treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:567-568.

- Gatti S, Carrozzo AM, Orlandi A, et al. Treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus with calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:837-839.

- Fox BJ, Lapins NA. Comparison of treatment modalities for epidermal nevus: a case report and review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:879-885.

- Pilanci O, Tas B, Ceran F, et al. A novel technique used in the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: tangential excision. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1066-1067.

- Lee BJ, Mancini AJ, Renucci J, et al. Full-thickness surgical excision for the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:285-292.

- Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Laser therapy of verrucous epidermal naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:124-127.

- Parera E, Gallardo F, Toll A, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus successfully treated with methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:253-256.

- Situm M, Bulat V, Majcen K, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253.

- Beggs S, Short J, Rengifo-Pardo M, et al. Applications of the excimer laser: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1201-1211.

- Bianchi B, Campolmi P, Mavilia L, et al. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm): an immunohistochemical study of cutaneous T cells and apoptosis-related molecules in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:408-413.

- Mudigonda T, Dabade TS, Feldman SR. A review of targeted ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:664-672.

- Kamo A, Tominaga M, Kamata Y, et al. The excimer lamp induces cutaneous nerve degeneration and reduces scratching in a dry-skin mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2977-2984.

- Bulat V, Majcen K, Dzapo A, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26

The CO2 laser also has demonstrated success. One study showed considerable improvement of pruritus and partial resolution of lesions only 5 weeks following a single CO2 laser treatment.5 Another study showed promising results when combining CO2 pulsed laser therapy with fractional CO2 laser treatment.6 Other laser therapies including the argon27 and flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye lasers8 have been used with limited success. The use of light therapy and lasers in psoriasis have now increased the treatment options for ILVEN based on the rationale of their shared histopathologic characteristics. Photodynamic therapy also has been attempted because of its successful use in psoriasis patients. It has been found to be successful in diminishing ILVEN lesions and associated pruritus after a few weeks of therapy; however, treatment is limited by the associated pain and requirement for local anesthesia.28

The excimer laser is a form of targeted phototherapy that emits monochromatic light at 308 nm.29 It is ideal for inflammatory skin lesions because the UVB light induces apoptosis.30 Psoriasis lesions treated with the excimer laser show a decrease in keratinocyte proliferation, which in turn reverses epidermal acanthosis and causes T-cell depletion due to upregulation of p53.29,31 This mechanism of action addresses the overproliferation of keratinocytes mediated by T cells in psoriasis and contributes to the success of excimer laser treatment.31 A considerable advantage is its localized treatment, resulting in lower cumulative doses of UVB and reducing the possible carcinogenic and phototoxic risks of whole-body phototherapy.32

One study examined the antipruritic effects of the excimer laser following the treatment of epidermal hyperinnervation leading to intractable pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers suggested that a potential explanation for the antipruritic effect of the excimer laser may be secondary to nerve degeneration.33 Additionally, low doses of UVB light also may inhibit mast cell degranulation and prevent histamine release, further supporting the antipruritic properties of excimer laser.34

In our patient, failed treatment with other modalities led to trial of excimer laser therapy because of the overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with psoriasis. Excimer laser improved the clinical appearance and overall texture of the ILVEN lesions and decreased pruritus. The reasons for treatment success may be two-fold. By decreasing the number of keratinocytes and mast cells, the excimer laser may have improved the epidermal hyperplasia and pruritus in the ILVEN lesions. Alternatively, because the patient had ILVEN lesions since infancy, psoriasis may have developed in the location of the ILVEN lesions due to koebnerization, resulting in the clinical response to excimer therapy; however, she had no other clinical evidence of psoriasis.

Because of the recalcitrance of ILVEN lesions to conventional therapies, it is important to investigate therapies that may be of possible benefit. Our novel case documents successful use of the excimer laser in the treatment of ILVEN.

Conclusion

Our case of ILVEN in a woman that had been present since infancy highlights the disease pathology as well as a potential new treatment modality. The patient was refractory to first-line treatments and was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient was subsequently treated with a trial of a 308-nm excimer laser with clinical improvement of the lesions. It is possible that the similarity of ILVEN and psoriasis may have contributed to the clinical improvement in our patient, but the mechanism of action remains unknown. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding optimal treatment of ILVEN, the current case offers dermatologists an option for patients who are refractory to other treatments.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26

The CO2 laser also has demonstrated success. One study showed considerable improvement of pruritus and partial resolution of lesions only 5 weeks following a single CO2 laser treatment.5 Another study showed promising results when combining CO2 pulsed laser therapy with fractional CO2 laser treatment.6 Other laser therapies including the argon27 and flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye lasers8 have been used with limited success. The use of light therapy and lasers in psoriasis have now increased the treatment options for ILVEN based on the rationale of their shared histopathologic characteristics. Photodynamic therapy also has been attempted because of its successful use in psoriasis patients. It has been found to be successful in diminishing ILVEN lesions and associated pruritus after a few weeks of therapy; however, treatment is limited by the associated pain and requirement for local anesthesia.28

The excimer laser is a form of targeted phototherapy that emits monochromatic light at 308 nm.29 It is ideal for inflammatory skin lesions because the UVB light induces apoptosis.30 Psoriasis lesions treated with the excimer laser show a decrease in keratinocyte proliferation, which in turn reverses epidermal acanthosis and causes T-cell depletion due to upregulation of p53.29,31 This mechanism of action addresses the overproliferation of keratinocytes mediated by T cells in psoriasis and contributes to the success of excimer laser treatment.31 A considerable advantage is its localized treatment, resulting in lower cumulative doses of UVB and reducing the possible carcinogenic and phototoxic risks of whole-body phototherapy.32

One study examined the antipruritic effects of the excimer laser following the treatment of epidermal hyperinnervation leading to intractable pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers suggested that a potential explanation for the antipruritic effect of the excimer laser may be secondary to nerve degeneration.33 Additionally, low doses of UVB light also may inhibit mast cell degranulation and prevent histamine release, further supporting the antipruritic properties of excimer laser.34

In our patient, failed treatment with other modalities led to trial of excimer laser therapy because of the overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with psoriasis. Excimer laser improved the clinical appearance and overall texture of the ILVEN lesions and decreased pruritus. The reasons for treatment success may be two-fold. By decreasing the number of keratinocytes and mast cells, the excimer laser may have improved the epidermal hyperplasia and pruritus in the ILVEN lesions. Alternatively, because the patient had ILVEN lesions since infancy, psoriasis may have developed in the location of the ILVEN lesions due to koebnerization, resulting in the clinical response to excimer therapy; however, she had no other clinical evidence of psoriasis.

Because of the recalcitrance of ILVEN lesions to conventional therapies, it is important to investigate therapies that may be of possible benefit. Our novel case documents successful use of the excimer laser in the treatment of ILVEN.

Conclusion

Our case of ILVEN in a woman that had been present since infancy highlights the disease pathology as well as a potential new treatment modality. The patient was refractory to first-line treatments and was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient was subsequently treated with a trial of a 308-nm excimer laser with clinical improvement of the lesions. It is possible that the similarity of ILVEN and psoriasis may have contributed to the clinical improvement in our patient, but the mechanism of action remains unknown. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding optimal treatment of ILVEN, the current case offers dermatologists an option for patients who are refractory to other treatments.

- Altman J, Mehregan AH. Inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:385-389.

- Hofer T. Does inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus represent a segmental type 1/type 2 mosaic of psoriasis? Dermatology. 2006;212:103-107.

- Rogers M, McCrossin I, Commens C. Epidermal nevi and the epidermal nevus syndrome: a review of 131 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:476-488.

- Khachemoune A, Janjua S, Guldbakke K. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report and short review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:261-267.

- Ulkur E, Celikoz B, Yuksel F, et al. Carbon dioxide laser therapy for an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:428-430.

- Conti R, Bruscino N, Campolmi P, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: why a combined laser therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:242-245.

- Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-918.

- Alster TS. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successful treatment with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:513-514.

- Kruse LL. Differential diagnosis of linear eruptions in children. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:194-198.

- Renner R, Colsman A, Sticherling M. ILVEN: is it psoriasis? debate based on successful treatment with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:631-632.

- Lee SH, Rogers M. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevi: a review of 23 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:252-256.

- Ito M, Shimizu N, Fujiwara H, et al. Histopathogenesis of inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus: histochemistry, immunohistochemistry and ultrastructure. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:491-499.

- Cerio R, Jones EW, Eady RA. ILVEN responding to occlusive potent topical steroid therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:279-281.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Vissers WH, Muys L, Erp PE, et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation between ILVEN and psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:216-220.

- Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Gupta R, et a. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with psoriasiform histology. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:211.

- Bennett RG, Burns L, Wood MG. Systematized epidermal nevus: a determinant for the localization of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:705-757.

- Tran K, Jao-Tan C, Ho N. ILVEN and psoriasis: a retrospective study among pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB163.

- Happle R. Superimposed linear psoriasis: a historical case revisited. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1027-1028; discussion 1029.

- Özdemir M, Balevi A, Esen H. An inflammatory verrucous epidermal nevus concomitant with psoriasis: treatment with adalimumab. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Zvulunov A, Grunwald MH, Halvy S. Topical calcipotriol for treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:567-568.

- Gatti S, Carrozzo AM, Orlandi A, et al. Treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus with calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:837-839.

- Fox BJ, Lapins NA. Comparison of treatment modalities for epidermal nevus: a case report and review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:879-885.

- Pilanci O, Tas B, Ceran F, et al. A novel technique used in the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: tangential excision. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1066-1067.

- Lee BJ, Mancini AJ, Renucci J, et al. Full-thickness surgical excision for the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:285-292.

- Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Laser therapy of verrucous epidermal naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:124-127.

- Parera E, Gallardo F, Toll A, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus successfully treated with methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:253-256.

- Situm M, Bulat V, Majcen K, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253.

- Beggs S, Short J, Rengifo-Pardo M, et al. Applications of the excimer laser: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1201-1211.

- Bianchi B, Campolmi P, Mavilia L, et al. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm): an immunohistochemical study of cutaneous T cells and apoptosis-related molecules in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:408-413.

- Mudigonda T, Dabade TS, Feldman SR. A review of targeted ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:664-672.

- Kamo A, Tominaga M, Kamata Y, et al. The excimer lamp induces cutaneous nerve degeneration and reduces scratching in a dry-skin mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2977-2984.

- Bulat V, Majcen K, Dzapo A, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253

- Altman J, Mehregan AH. Inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:385-389.

- Hofer T. Does inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus represent a segmental type 1/type 2 mosaic of psoriasis? Dermatology. 2006;212:103-107.

- Rogers M, McCrossin I, Commens C. Epidermal nevi and the epidermal nevus syndrome: a review of 131 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:476-488.

- Khachemoune A, Janjua S, Guldbakke K. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report and short review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:261-267.

- Ulkur E, Celikoz B, Yuksel F, et al. Carbon dioxide laser therapy for an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:428-430.

- Conti R, Bruscino N, Campolmi P, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: why a combined laser therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:242-245.

- Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-918.

- Alster TS. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successful treatment with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:513-514.

- Kruse LL. Differential diagnosis of linear eruptions in children. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:194-198.

- Renner R, Colsman A, Sticherling M. ILVEN: is it psoriasis? debate based on successful treatment with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:631-632.

- Lee SH, Rogers M. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevi: a review of 23 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:252-256.

- Ito M, Shimizu N, Fujiwara H, et al. Histopathogenesis of inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus: histochemistry, immunohistochemistry and ultrastructure. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:491-499.

- Cerio R, Jones EW, Eady RA. ILVEN responding to occlusive potent topical steroid therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:279-281.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Vissers WH, Muys L, Erp PE, et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation between ILVEN and psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:216-220.

- Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Gupta R, et a. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with psoriasiform histology. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:211.

- Bennett RG, Burns L, Wood MG. Systematized epidermal nevus: a determinant for the localization of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:705-757.

- Tran K, Jao-Tan C, Ho N. ILVEN and psoriasis: a retrospective study among pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB163.

- Happle R. Superimposed linear psoriasis: a historical case revisited. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1027-1028; discussion 1029.

- Özdemir M, Balevi A, Esen H. An inflammatory verrucous epidermal nevus concomitant with psoriasis: treatment with adalimumab. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Zvulunov A, Grunwald MH, Halvy S. Topical calcipotriol for treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:567-568.

- Gatti S, Carrozzo AM, Orlandi A, et al. Treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus with calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:837-839.

- Fox BJ, Lapins NA. Comparison of treatment modalities for epidermal nevus: a case report and review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:879-885.

- Pilanci O, Tas B, Ceran F, et al. A novel technique used in the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: tangential excision. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1066-1067.

- Lee BJ, Mancini AJ, Renucci J, et al. Full-thickness surgical excision for the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:285-292.

- Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Laser therapy of verrucous epidermal naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:124-127.

- Parera E, Gallardo F, Toll A, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus successfully treated with methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:253-256.

- Situm M, Bulat V, Majcen K, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253.

- Beggs S, Short J, Rengifo-Pardo M, et al. Applications of the excimer laser: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1201-1211.

- Bianchi B, Campolmi P, Mavilia L, et al. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm): an immunohistochemical study of cutaneous T cells and apoptosis-related molecules in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:408-413.

- Mudigonda T, Dabade TS, Feldman SR. A review of targeted ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:664-672.

- Kamo A, Tominaga M, Kamata Y, et al. The excimer lamp induces cutaneous nerve degeneration and reduces scratching in a dry-skin mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2977-2984.

- Bulat V, Majcen K, Dzapo A, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253

Pigmented Lesion on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Monsel Solution Reaction

Exogenous substances can cause interesting incongruities in cutaneous biopsies of which pathologists and dermatologists should be cognizant. Exogenous lesions are caused by externally introduced foreign bodies, substances, or materials, such as sterile compressed sponges, aluminum chloride hexahydrate and anhydrous ethyl alcohol, silica, paraffin, and Monsel solution. Monsel solution reaction is a florid fibrohistiocytic proliferation stimulated by the application of Monsel solution. Monsel solution is a ferric subsulfate that often is used to achieve hemostasis after shave biopsies. Hemostasis is thought to result from the ability of ferric ions to denature and agglutinate proteins such as fibrinogen.1,2 Application of Monsel solution likely causes ferrugination of fibrin, dermal collagen, and striated muscle fibers. Some ferruginated collagen fibers are eliminated through the epidermis as the epidermis regenerates, while some fibers become calcified. Siderophages (iron-containing macrophages) are present in these areas. The ferrugination of collagen fibers becomes less pronounced as the biopsy sites heal and the iron pigment subsequently is absorbed by macrophages. Ferruginated skeletal muscles can act as foreign bodies and may elicit granulomatous reactions.2

It is currently unclear why fibrohistiocytic responses occur in some instances but not others. Iron stains (eg, Perls Prussian blue stain) make interpretation clear, provided the pathologist is familiar with Monsel solution. The primary differential diagnosis of these lesions centers on heavily pigmented melanocytic proliferations. It is critical to review prior biopsy sections or to have definite knowledge of the prior biopsy diagnosis. Histologically, the epidermis may demonstrate nonspecific reactive changes such as hyperkeratosis with foci of irregular acanthosis. The prominent features are present in the dermis where there is a proliferation of spindle- and polyhedral-shaped cells that may show cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. The cells contain refractile brown pigment scattered in the dermis and deposited on collagen fibers (quiz images). Occasional large black or brown encrustations may be identified. Monsel-containing cells may indiscernibly blend with foci of more blatantly fibrohistiocytic differentiation, in which case iron stains are strongly positive (Figure 1). If the clinician uses Monsel solution for hemostasis during the removal of a nevomelanocytic neoplasm, it might be necessary to use melanin stains or immunohistochemistry on the reexcision specimen to distinguish between residual nevomelanocytic and fibrohistiocytic cells.3

Common blue nevus is a benign, typically intradermal melanocytic lesion. It most frequently occurs in young adults and has a predilection for females. Clinically, it can be found anywhere on the body as a single, asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, blue-black, dome-shaped papule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, it is characterized by pigmented, dendritic, spindle-shaped melanocytes that typically are separated by thick collagen bundles (Figure 2). The melanocytes typically have small nuclei with occasional basophilic nucleolus. Melanocytes typically are diffusely positive for melanocytic markers including human melanoma black (HMB) 45, S-100, Melan-A, and microphthalmia transcription factor 1. In contrast to most other benign melanocytic nevi, HMB-45 strongly stains the entire lesion in blue nevi.4

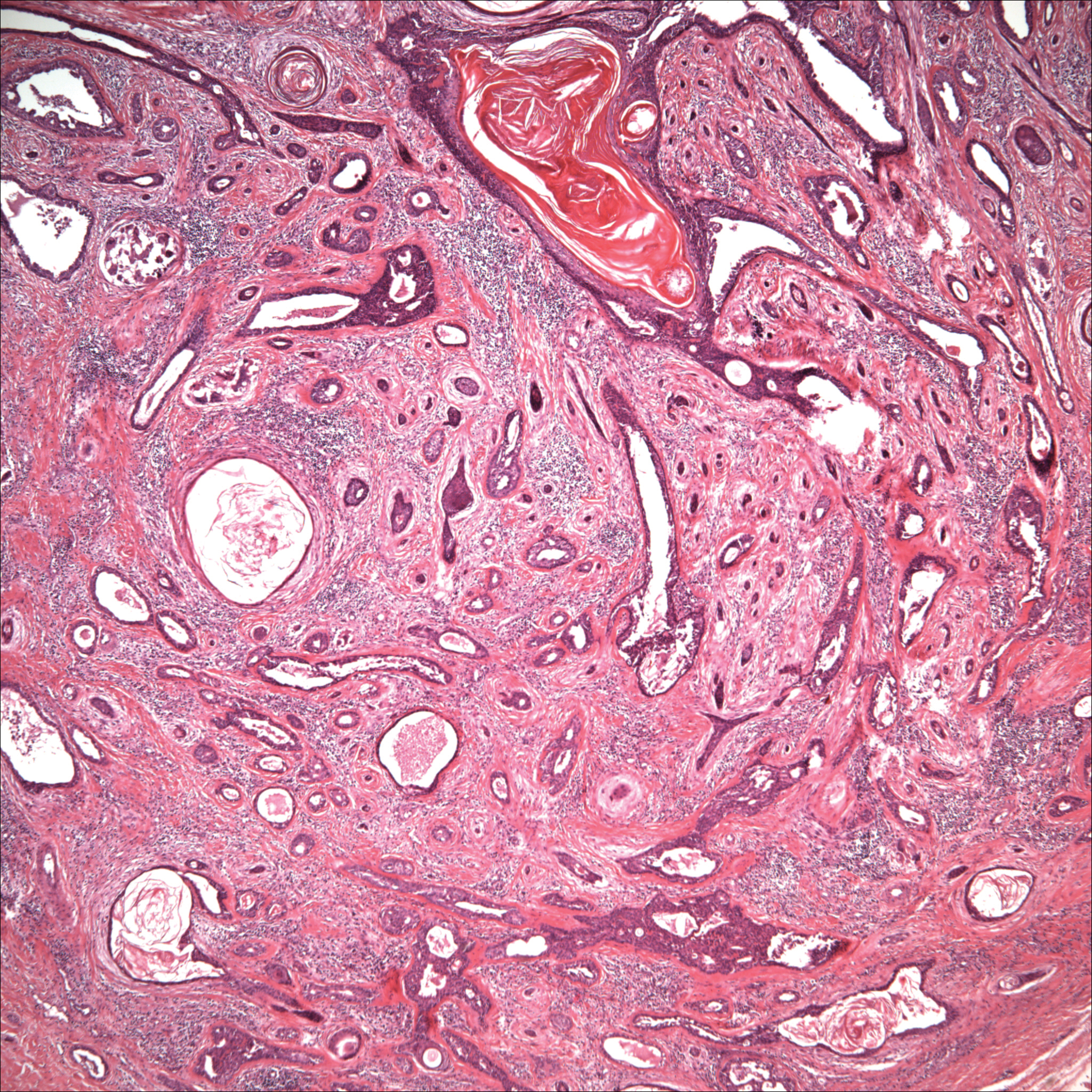

Desmoplastic melanoma accounts for 1% to 4% of all melanomas. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years and, as in other types of melanoma, men are more commonly affected.5 Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma typically presents on the head and neck as a painless indurated plaque, though it can present as a small papule or nodule. Nearly half of desmoplastic melanomas lack obvious pigmentation, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or a scar. Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are composed of spindled melanocytes separated by collagen fibers or fibrous stroma (Figure 3). Histology displays variable cytologic atypia and stromal fibrosis. Characteristically there are small islands of lymphocytes and plasma cells within or at the edge of the tumor. The spindle cells stain positive with S-100 and Sry-related HMg-box gene 10, SOX10. Type IV collagen and laminin often are expressed in desmoplastic melanoma. In contrast to many other subtypes of melanoma, HMB-45 and Melan-A usually are negative.6

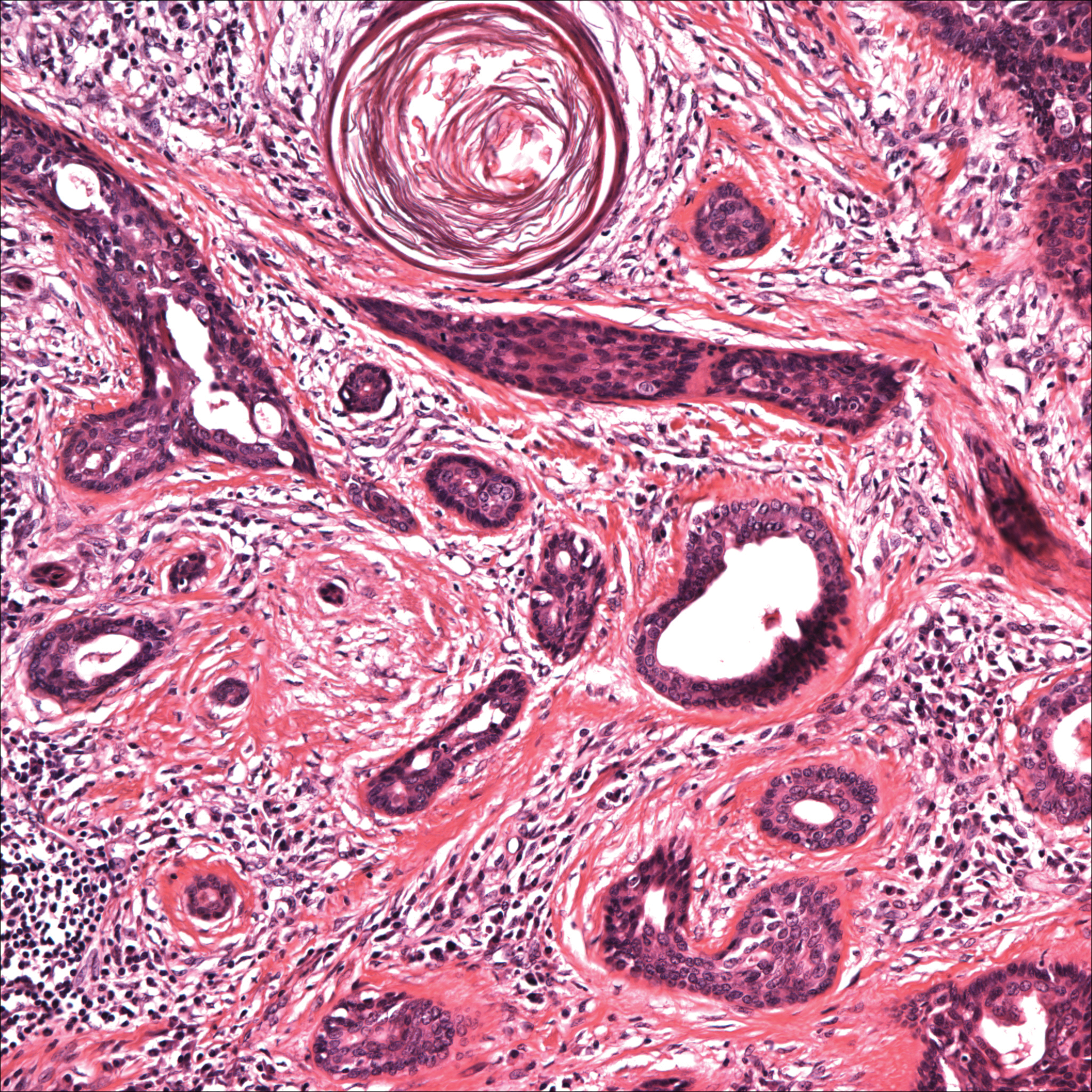

Animal-type melanoma is a rare neoplasm that differs from other subtypes of melanoma both clinically and histologically. Most frequently, animal-type melanoma affects younger adults (median age, 27 years) and arises on the arms and legs, head and neck, or trunk; men and women are affected equally.7 It most commonly presents with a blue or blue-black nodule with a blue-white veil or irregular white areas. Histologically, animal-type melanoma is a predominantly dermal-based melanocytic proliferation with heavily pigmented epithelioid and spindled melanocytes (Figure 4). The pigmentation pattern ranges widely from fine, granular, light brown deposits to coarse dark brown deposits with malignant cells often arranged in fascicles or sheets. Frequently, there is periadnexal and perieccrine spread. Often, there is epidermal hyperplasia above the dermis. As with conventional melanoma, the immunohistochemistry of animal-type melanoma is positive for S-100 protein, HMB-45, SOX10, and Melan-A.7

Recurrent nevi typically arise within 6 months of a previously biopsied melanocytic nevus. Most recurrent nevi originate from common banal nevi (most often a compound nevus). Recurrent nevi also may arise from congenital, atypical/dysplastic, and Spitz nevi. Most often they are found on the back of women aged 20 to 30 years.8 Clinically, they manifest as a macular area of scar with variegated hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation as well as linear streaking. They may demonstrate variable diffuse, stippled, and halo pigmentation patterns. Classically, recurrent nevi present with a trizonal histologic pattern. Within the epidermis there is a proliferation of melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction, which may show varying degrees of atypia and pagetoid migration. The melanocytes often are described as epithelioid with round nuclei and even chromatin (Figure 5). The atypical features should be confined to the epidermis overlying the prior biopsy site. Within the dermis there is dense dermal collagen and fibrosis with vertically oriented blood vessels. Finally, features of the original nevus may be seen at the base of the lesion. Although immunohistochemistry may be helpful in some cases, an appropriate clinical history and comparison to the prior biopsy can be invaluable.8

Host tissue reactions resulting in artefactual changes caused by foreign bodies or substances may confound the untrained eye. Monsel solution reaction may be confused for a blue nevus, desmoplastic melanoma, animal-type melanoma, and a residual/recurrent nevus. This confusion could lead to serious diagnostic errors that could cause an unfavorable outcome for the patient. It is critical to know the salient points in the patient's clinical history. Knowledge of the Monsel solution reaction and other exogenous lesions as well as the subsequent unique tissue reaction patterns can aid in facilitating an accurate and prompt pathologic diagnosis.

- Olmstead PM, Lund HZ, Leonard DD. Monsel's solution: a histologic nuisance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:492-498.

- Amazon K, Robinson MJ, Rywlin AM. Ferrugination caused by Monsel's solution. clinical observations and experimentations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:197-205.

- Del Rosario RN, Barr RJ, Graham BS, et al. Exogenous and endogenous cutaneous anomalies and curiosities. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:259-267.

- Calonje E, Blessing K, Glusac E, et al. Blue naevi. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:95-99.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- McCarthy SW, Crotty KA, Scolyer RA. Desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, et al, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006:76-78.

- Vyas R, Keller JJ, Honda K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal-type melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1031-1039.

- Fox JC, Reed JA, Shea CR. The recurrent nevus phenomenon: a history of challenge, controversy, and discovery. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:842-846.

The Diagnosis: Monsel Solution Reaction

Exogenous substances can cause interesting incongruities in cutaneous biopsies of which pathologists and dermatologists should be cognizant. Exogenous lesions are caused by externally introduced foreign bodies, substances, or materials, such as sterile compressed sponges, aluminum chloride hexahydrate and anhydrous ethyl alcohol, silica, paraffin, and Monsel solution. Monsel solution reaction is a florid fibrohistiocytic proliferation stimulated by the application of Monsel solution. Monsel solution is a ferric subsulfate that often is used to achieve hemostasis after shave biopsies. Hemostasis is thought to result from the ability of ferric ions to denature and agglutinate proteins such as fibrinogen.1,2 Application of Monsel solution likely causes ferrugination of fibrin, dermal collagen, and striated muscle fibers. Some ferruginated collagen fibers are eliminated through the epidermis as the epidermis regenerates, while some fibers become calcified. Siderophages (iron-containing macrophages) are present in these areas. The ferrugination of collagen fibers becomes less pronounced as the biopsy sites heal and the iron pigment subsequently is absorbed by macrophages. Ferruginated skeletal muscles can act as foreign bodies and may elicit granulomatous reactions.2

It is currently unclear why fibrohistiocytic responses occur in some instances but not others. Iron stains (eg, Perls Prussian blue stain) make interpretation clear, provided the pathologist is familiar with Monsel solution. The primary differential diagnosis of these lesions centers on heavily pigmented melanocytic proliferations. It is critical to review prior biopsy sections or to have definite knowledge of the prior biopsy diagnosis. Histologically, the epidermis may demonstrate nonspecific reactive changes such as hyperkeratosis with foci of irregular acanthosis. The prominent features are present in the dermis where there is a proliferation of spindle- and polyhedral-shaped cells that may show cytologic atypia and occasional mitotic figures. The cells contain refractile brown pigment scattered in the dermis and deposited on collagen fibers (quiz images). Occasional large black or brown encrustations may be identified. Monsel-containing cells may indiscernibly blend with foci of more blatantly fibrohistiocytic differentiation, in which case iron stains are strongly positive (Figure 1). If the clinician uses Monsel solution for hemostasis during the removal of a nevomelanocytic neoplasm, it might be necessary to use melanin stains or immunohistochemistry on the reexcision specimen to distinguish between residual nevomelanocytic and fibrohistiocytic cells.3

Common blue nevus is a benign, typically intradermal melanocytic lesion. It most frequently occurs in young adults and has a predilection for females. Clinically, it can be found anywhere on the body as a single, asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, blue-black, dome-shaped papule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, it is characterized by pigmented, dendritic, spindle-shaped melanocytes that typically are separated by thick collagen bundles (Figure 2). The melanocytes typically have small nuclei with occasional basophilic nucleolus. Melanocytes typically are diffusely positive for melanocytic markers including human melanoma black (HMB) 45, S-100, Melan-A, and microphthalmia transcription factor 1. In contrast to most other benign melanocytic nevi, HMB-45 strongly stains the entire lesion in blue nevi.4

Desmoplastic melanoma accounts for 1% to 4% of all melanomas. The median age at diagnosis is 62 years and, as in other types of melanoma, men are more commonly affected.5 Clinically, desmoplastic melanoma typically presents on the head and neck as a painless indurated plaque, though it can present as a small papule or nodule. Nearly half of desmoplastic melanomas lack obvious pigmentation, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or a scar. Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are composed of spindled melanocytes separated by collagen fibers or fibrous stroma (Figure 3). Histology displays variable cytologic atypia and stromal fibrosis. Characteristically there are small islands of lymphocytes and plasma cells within or at the edge of the tumor. The spindle cells stain positive with S-100 and Sry-related HMg-box gene 10, SOX10. Type IV collagen and laminin often are expressed in desmoplastic melanoma. In contrast to many other subtypes of melanoma, HMB-45 and Melan-A usually are negative.6

Animal-type melanoma is a rare neoplasm that differs from other subtypes of melanoma both clinically and histologically. Most frequently, animal-type melanoma affects younger adults (median age, 27 years) and arises on the arms and legs, head and neck, or trunk; men and women are affected equally.7 It most commonly presents with a blue or blue-black nodule with a blue-white veil or irregular white areas. Histologically, animal-type melanoma is a predominantly dermal-based melanocytic proliferation with heavily pigmented epithelioid and spindled melanocytes (Figure 4). The pigmentation pattern ranges widely from fine, granular, light brown deposits to coarse dark brown deposits with malignant cells often arranged in fascicles or sheets. Frequently, there is periadnexal and perieccrine spread. Often, there is epidermal hyperplasia above the dermis. As with conventional melanoma, the immunohistochemistry of animal-type melanoma is positive for S-100 protein, HMB-45, SOX10, and Melan-A.7