User login

Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita in Association With Mantle Cell Lymphoma

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

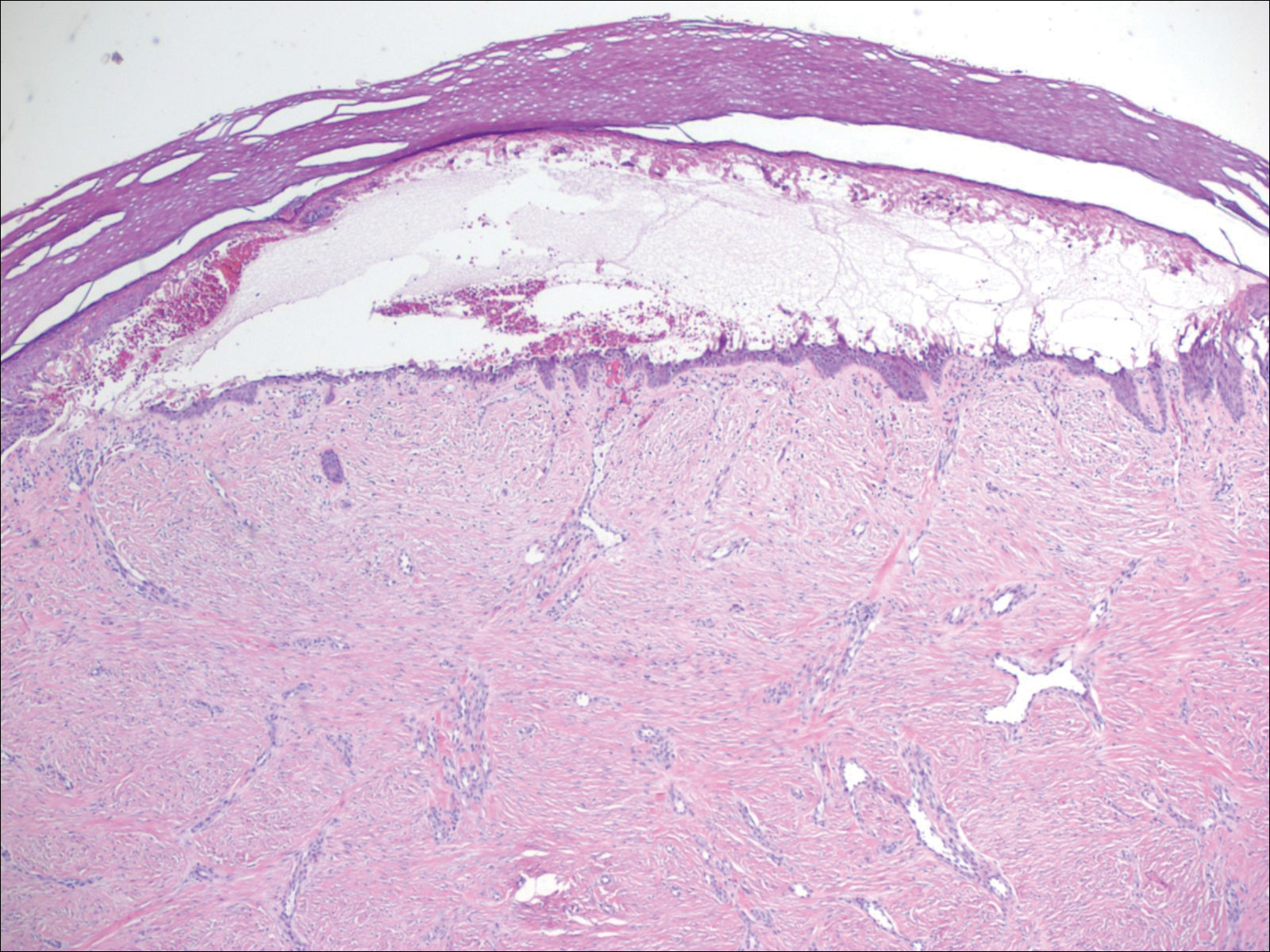

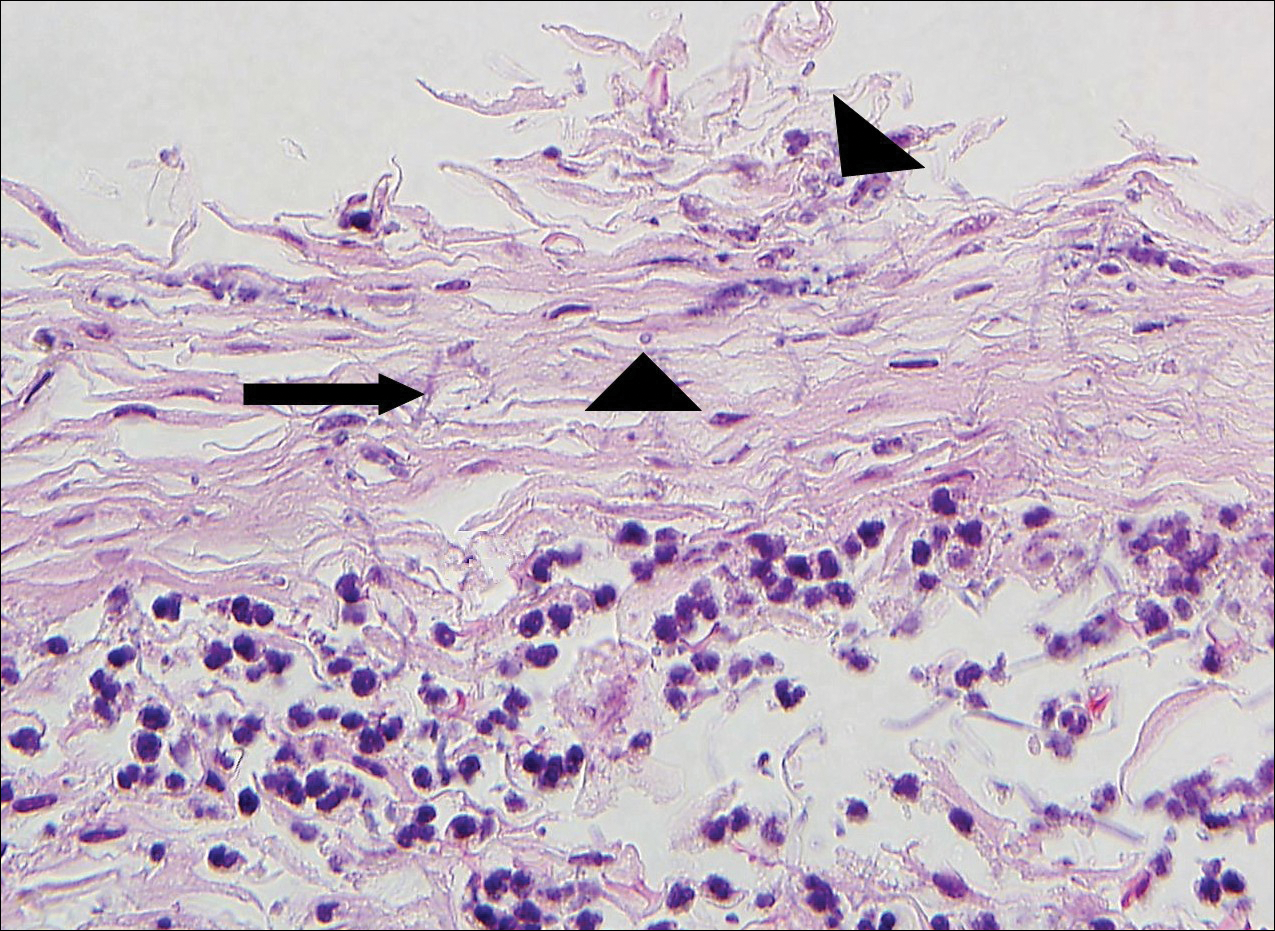

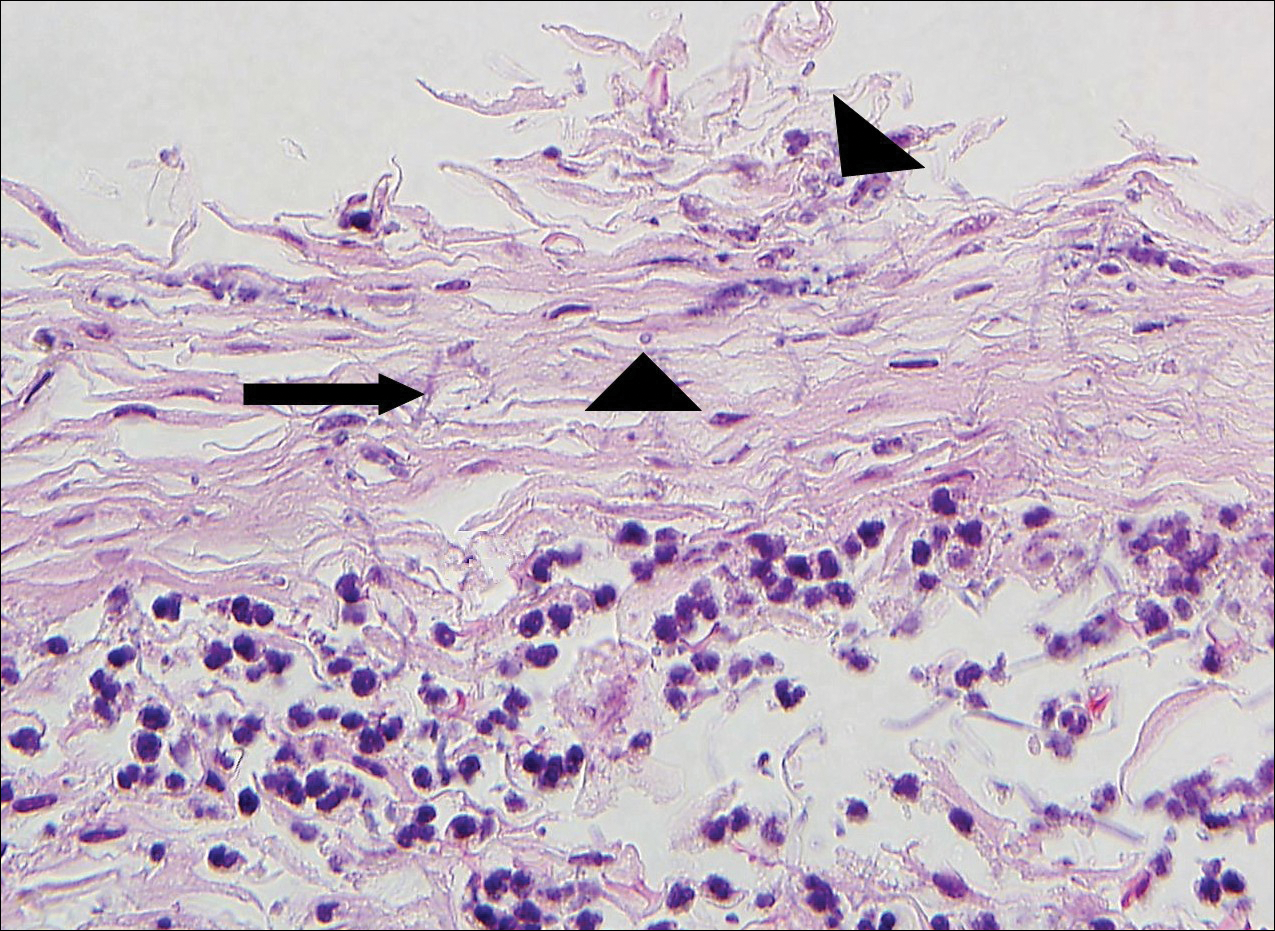

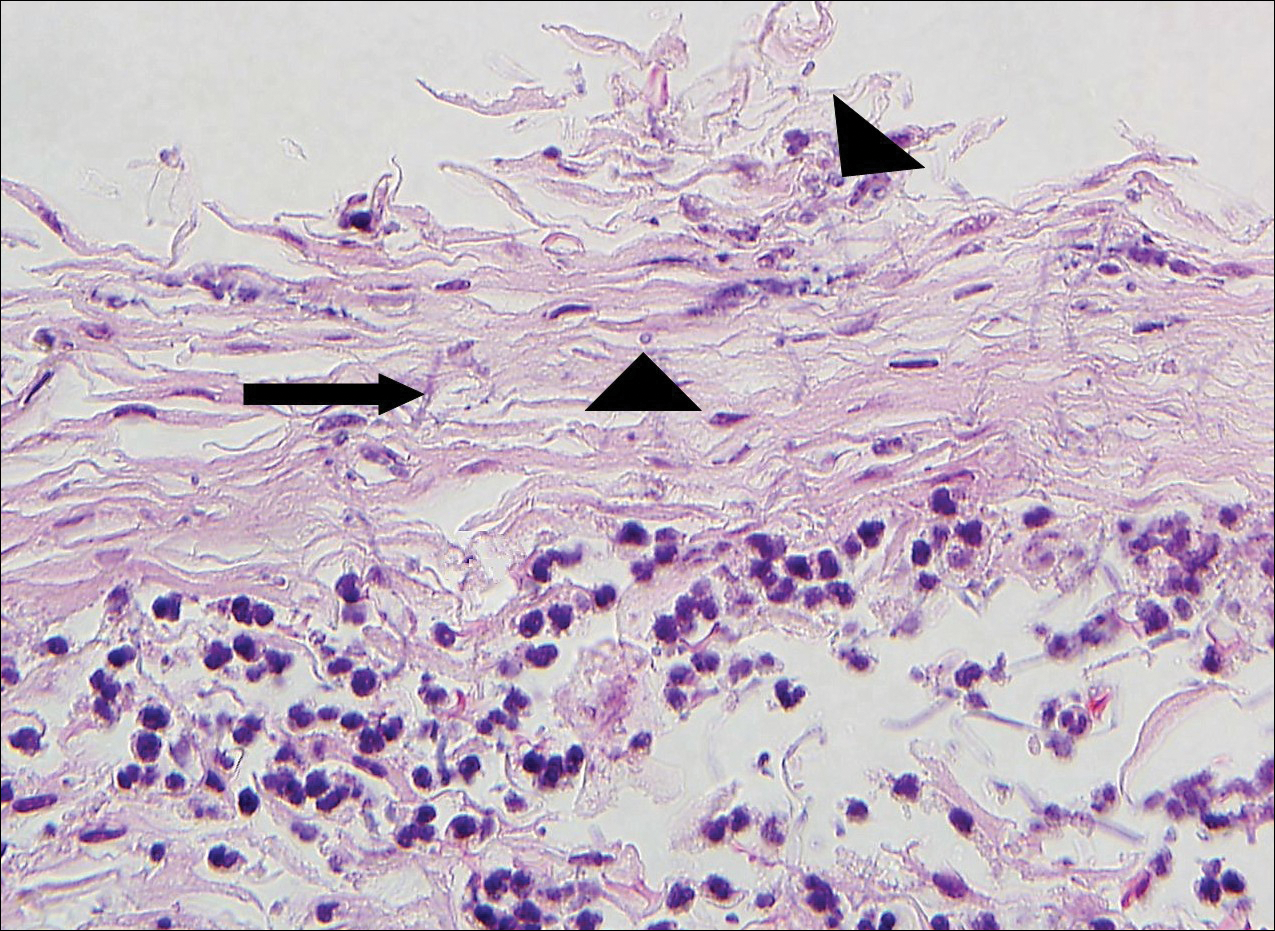

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

Practice Points

- Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is an uncommon blistering disorder and few cases have been associated with malignancy.

- Diagnosis of EBA is challenging and requires exclusion of other blistering diseases.

Slow-growing, Asymptomatic, Annular Plaques on the Bilateral Palms

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

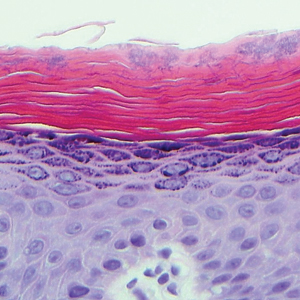

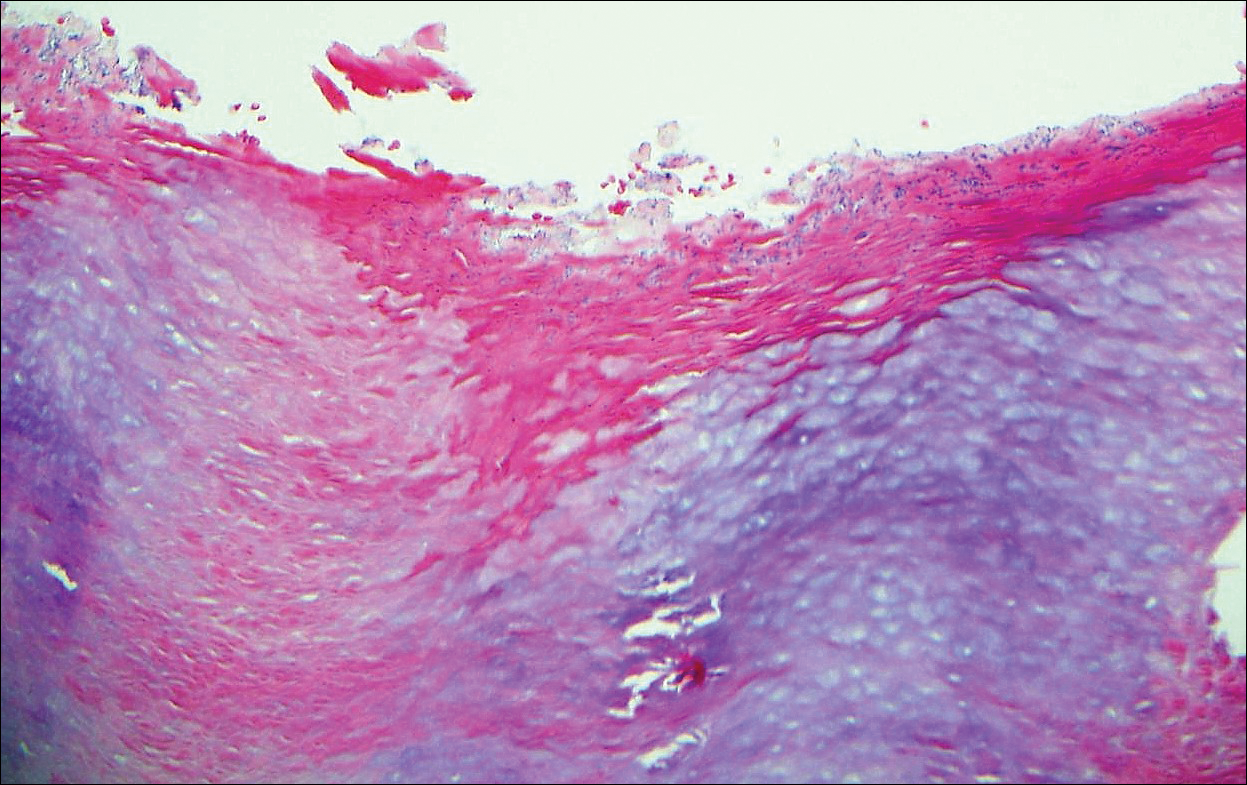

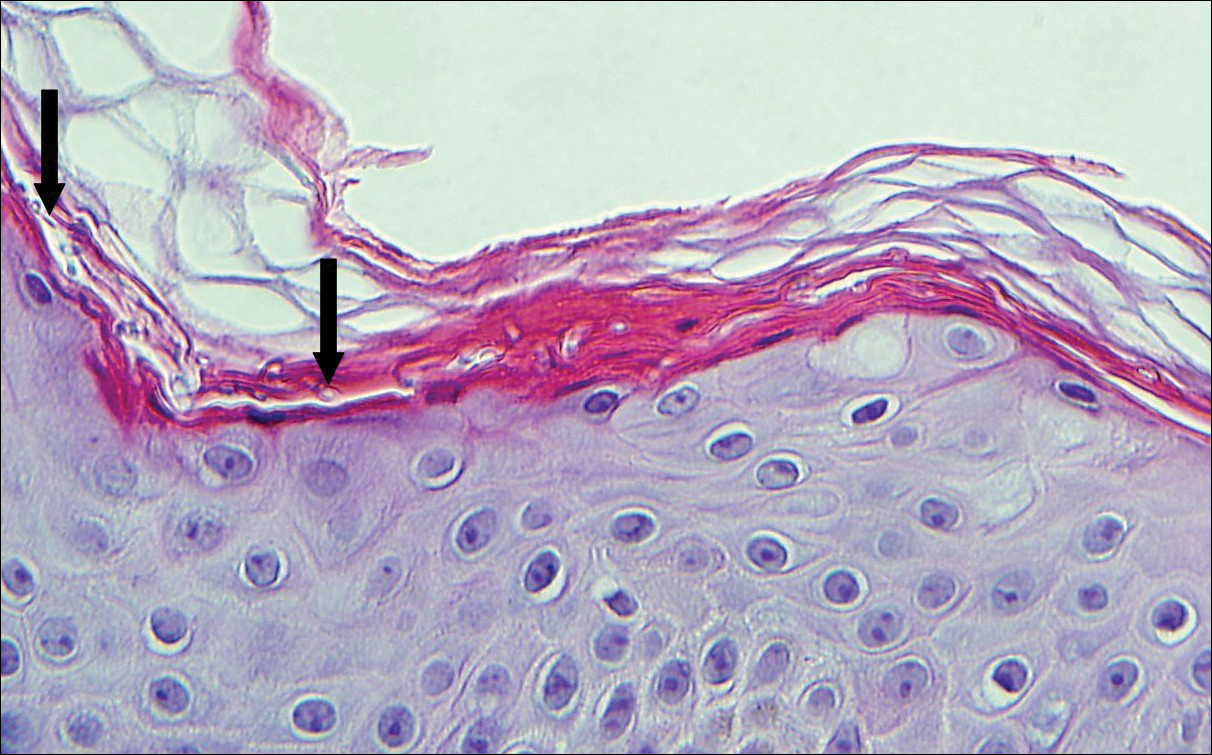

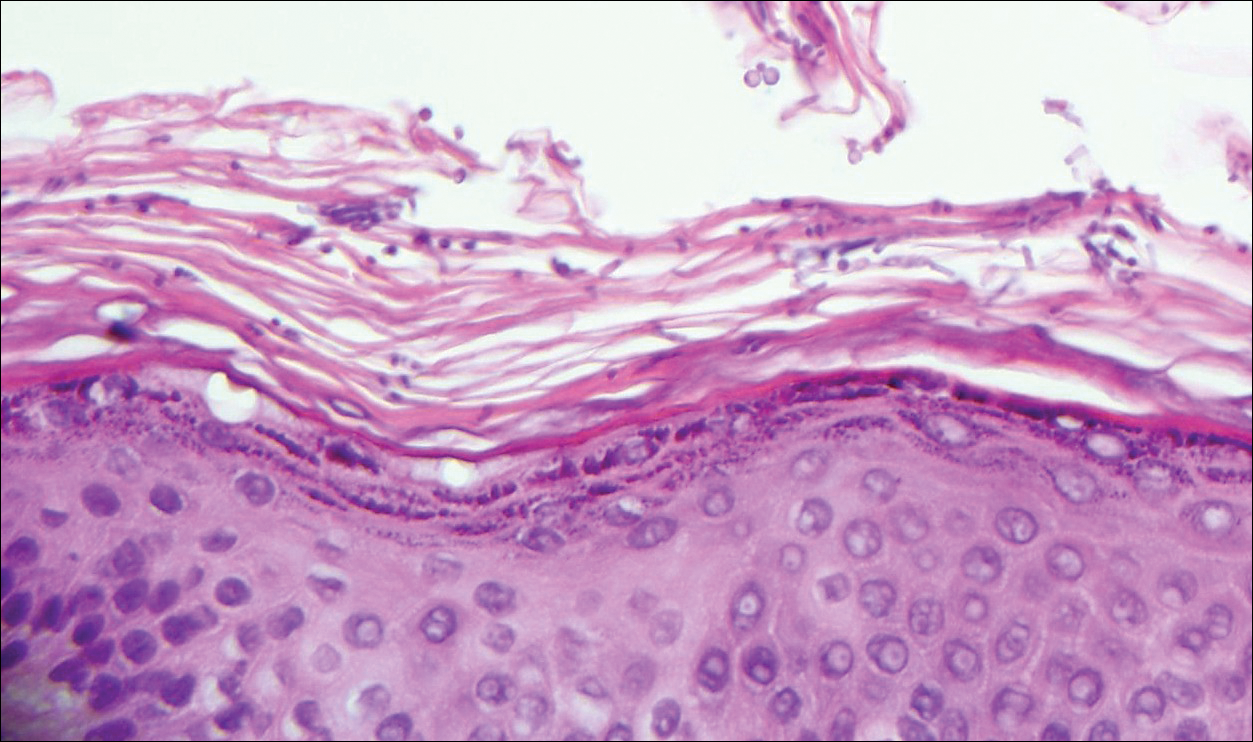

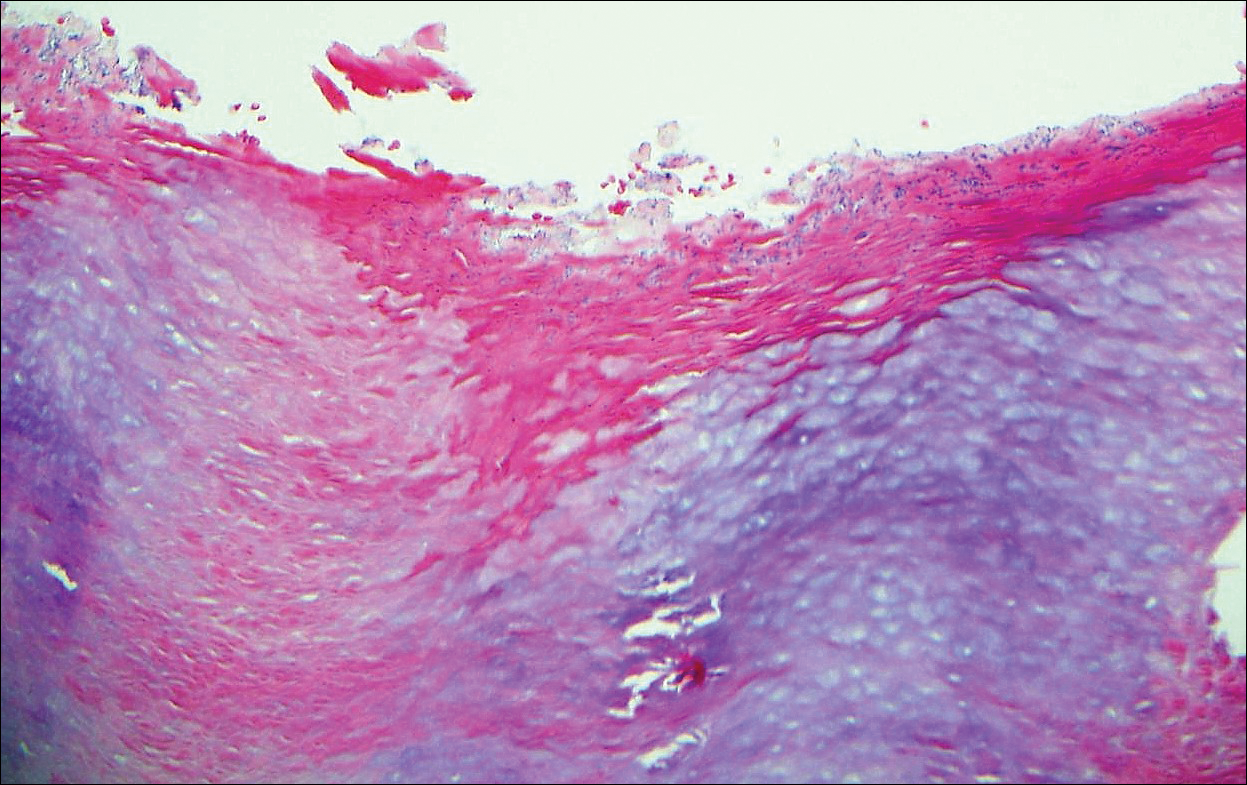

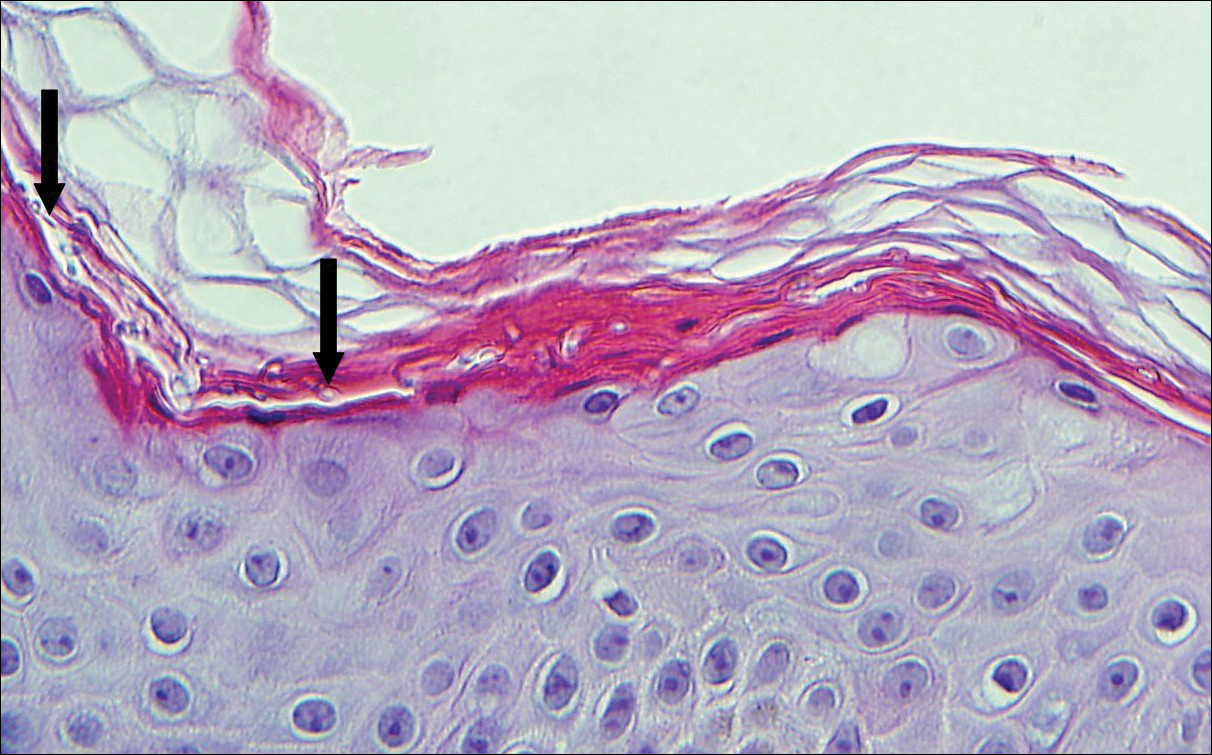

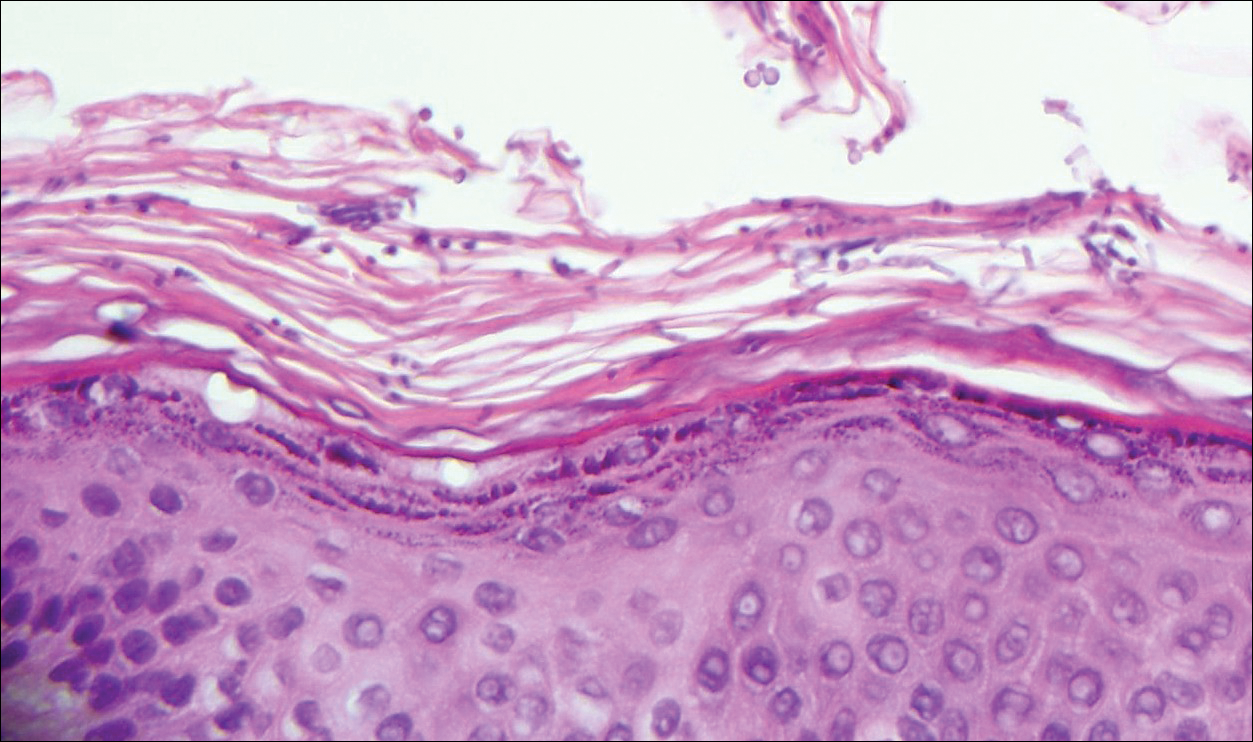

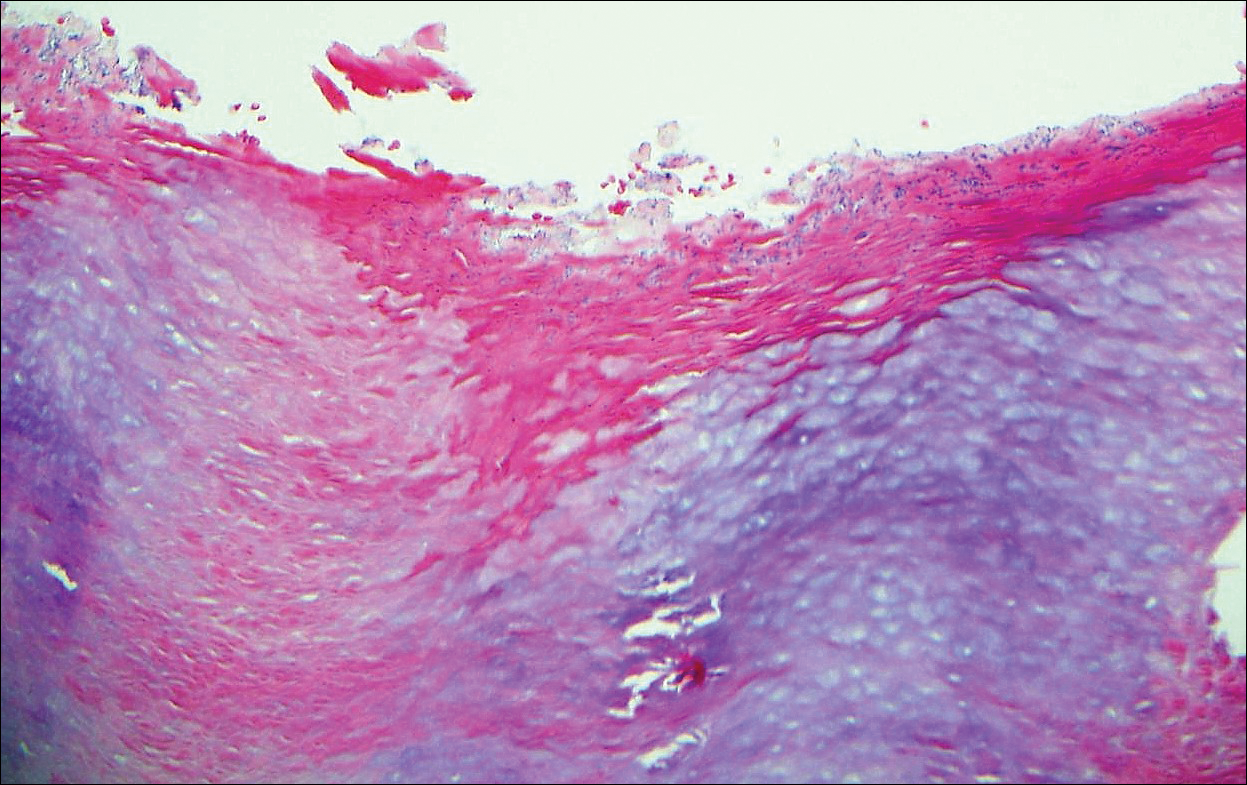

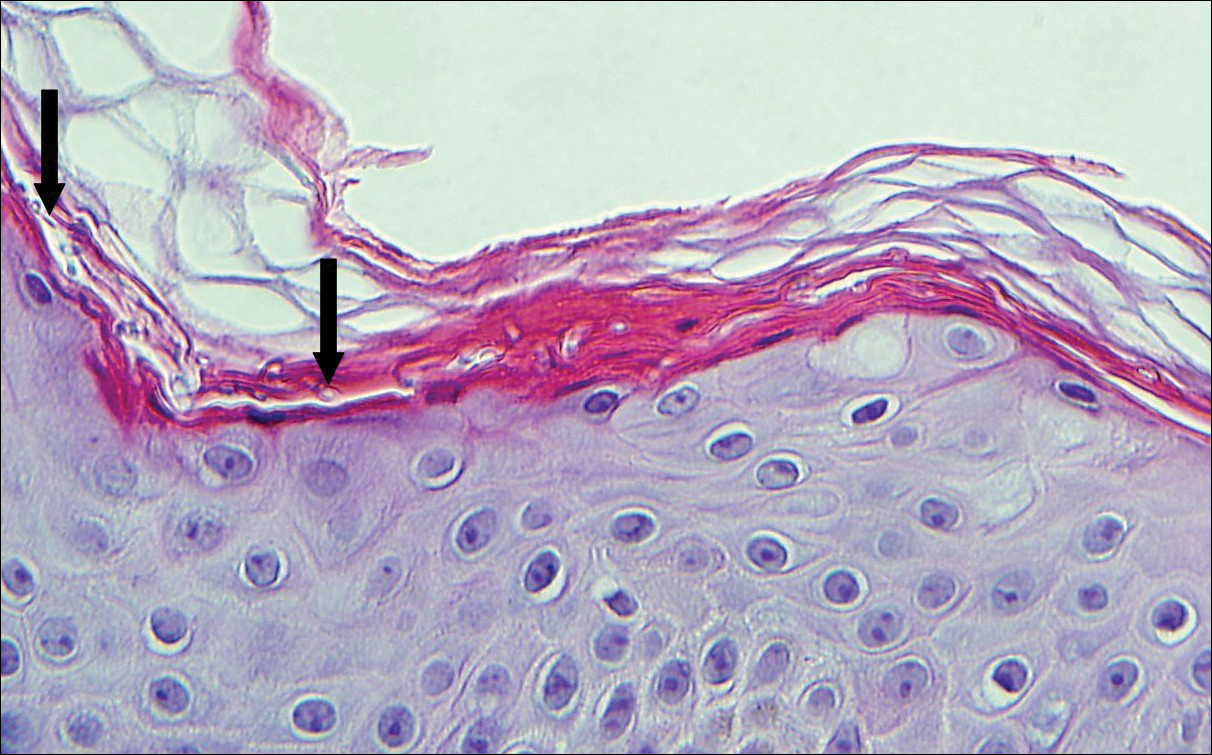

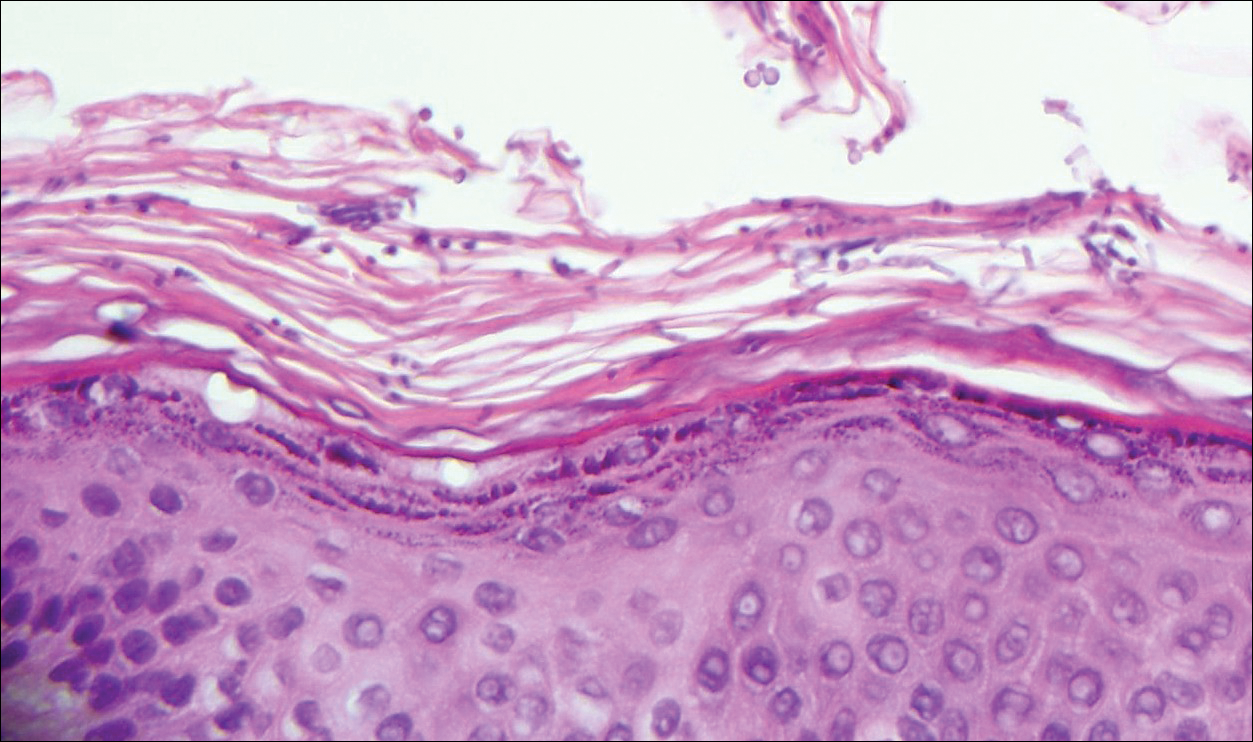

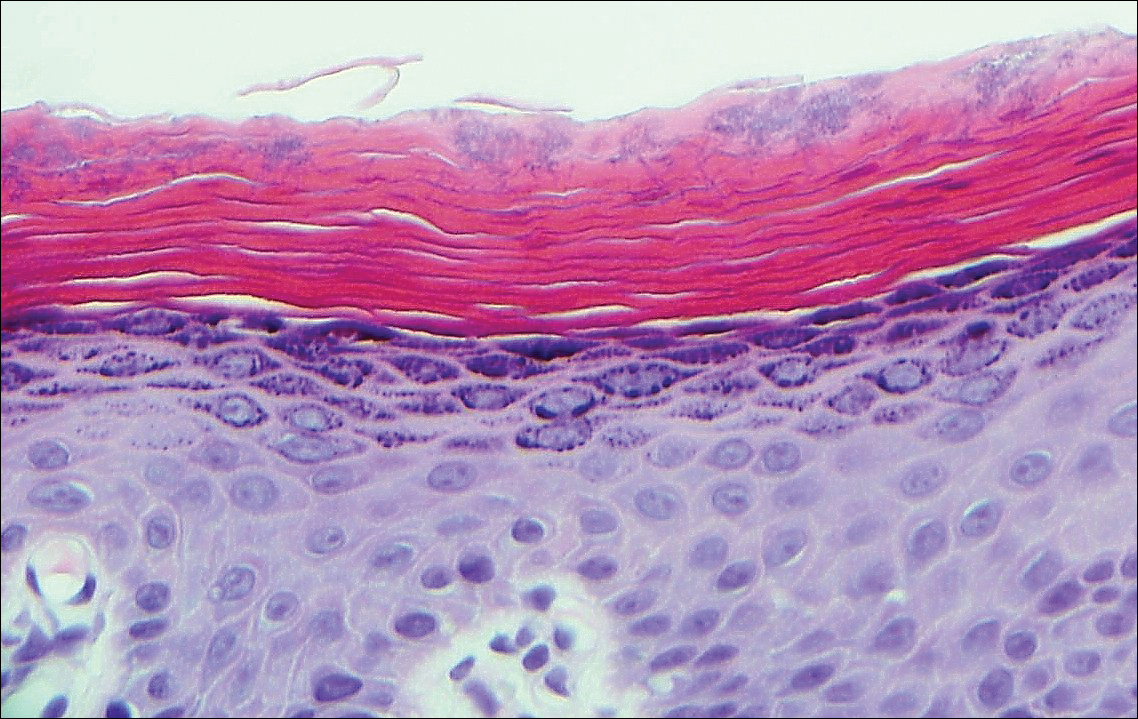

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

A 77-year-old woman presented with slow-growing, asymptomatic, annular plaques on the bilateral palms of many years' duration. There was no history of trauma or local infection. Prior treatment with over-the-counter creams was unsuccessful. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the lesion on the right palm was performed.

Painful Nonhealing Vulvar and Perianal Erosions

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

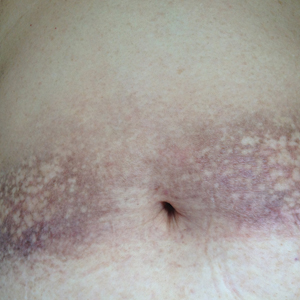

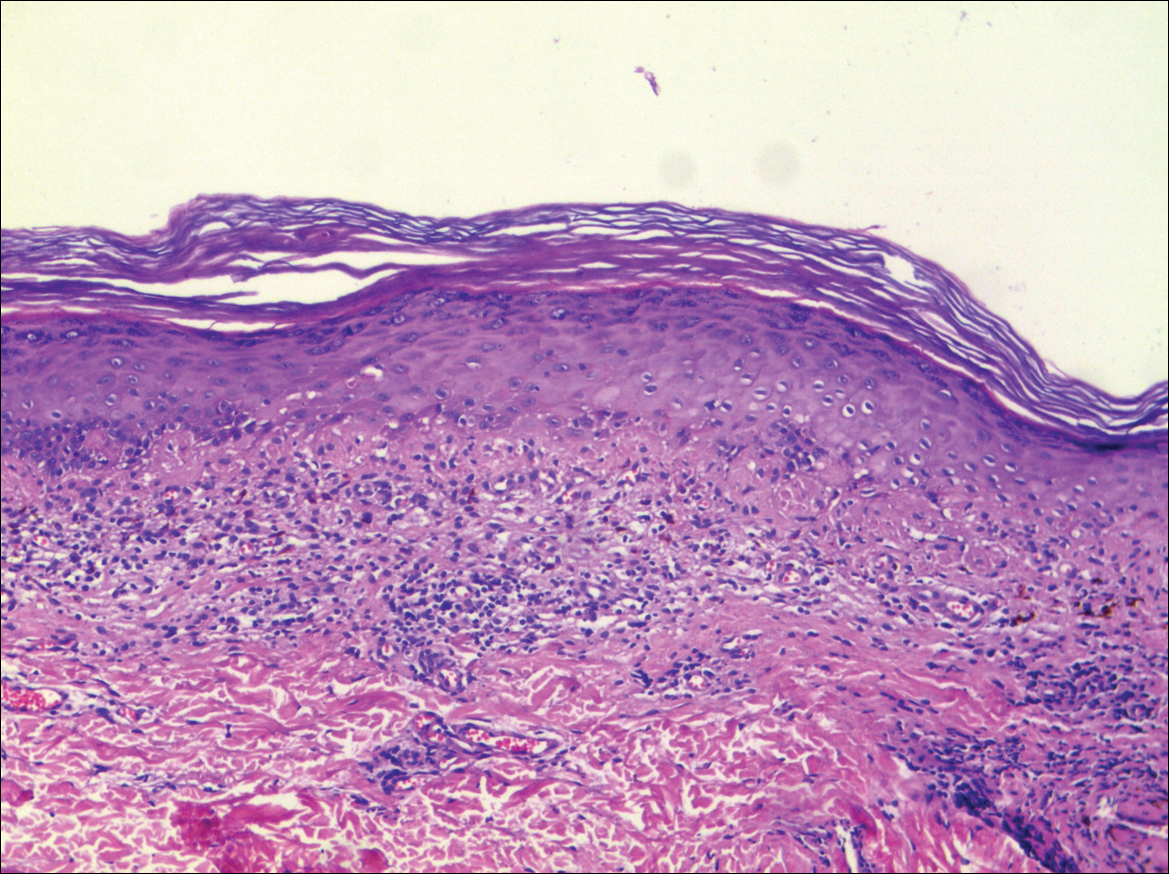

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn disease presented with painful nonhealing vulvar and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. The erosions developed 4 months after discontinuing adalimumab for a planned surgery. During this time, the patient also had an exacerbation of Crohn colitis and developed an anal fistula. Prior to this break in adalimumab, the patient's Crohn disease was well controlled on adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, azathioprine 100 mg daily, and mesalamine 4.8 g daily. Despite restarting adalimumab and therapy with multiple antibiotics (ie, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin), the erosions persisted. On physical examination erythematous plaques and nodules were present at the vulvar (top) and perianal (bottom) skin. In addition, well-demarcated erosions measuring 20 mm and 80 mm were present on the vulvar and perianal skin, respectively. Human immunodeficiency virus screening and rapid plasma reagin were negative.

Scaly Annular and Concentric Plaques

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

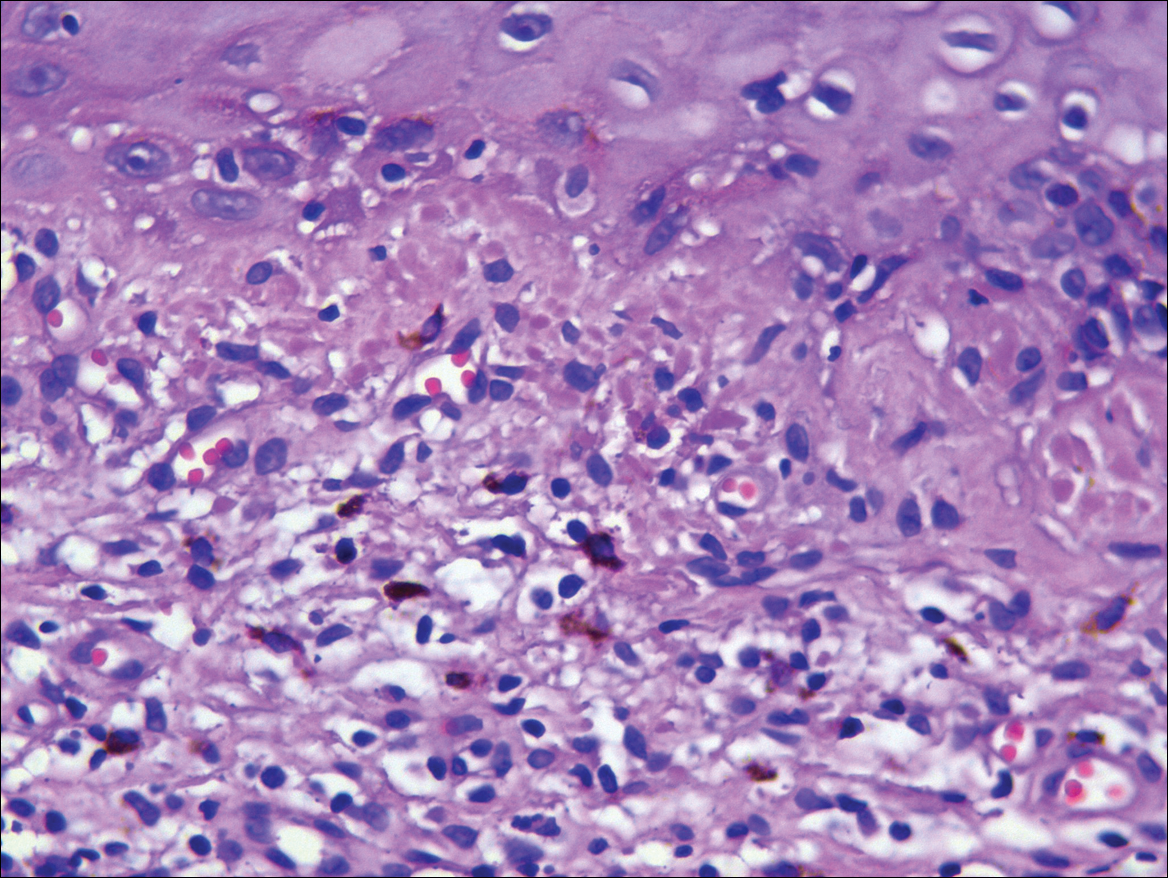

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

A healthy 23-year-old man presented for evaluation of an enlarging annular pruritic rash of 1.5 years' duration. Treatment with ciclopirox cream 0.77%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, fluticasone cream 0.05%, and halobetasol cream 0.05% prescribed by an outside physician provided only modest temporary improvement. The patient reported no history of travel outside of western New York, camping, tick bites, or medications. He denied any joint swelling or morning stiffness. Physical examination revealed multiple 4- to 6-cm pink, annular, scaly plaques with central clearing on the abdomen (top) and thighs. A few 1-cm pink scaly patches were present on the back (bottom), and few 2- to 3-mm pink scaly papules were noted on the extensor aspects of the elbows and forearms. A potassium hydroxide examination revealed no hyphal elements or yeast forms.

Idiopathic Eruptive Macular Pigmentation With Papillomatosis

To the Editor:

A 13-year-old white adolescent girl presented with asymptomatic discrete hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs of 7 months’ duration. The patient otherwise was in good health; her weight and height were on the 40th percentile on growth curves and she had no history of any medications. Treatments for the skin condition prescribed by outside dermatologists included minocycline 75 mg twice daily for 2 months, lactic acid lotion 12% daily, and ketoconazole 400 mg administered twice 1 week apart.

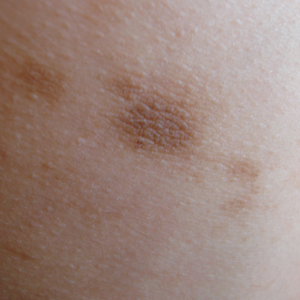

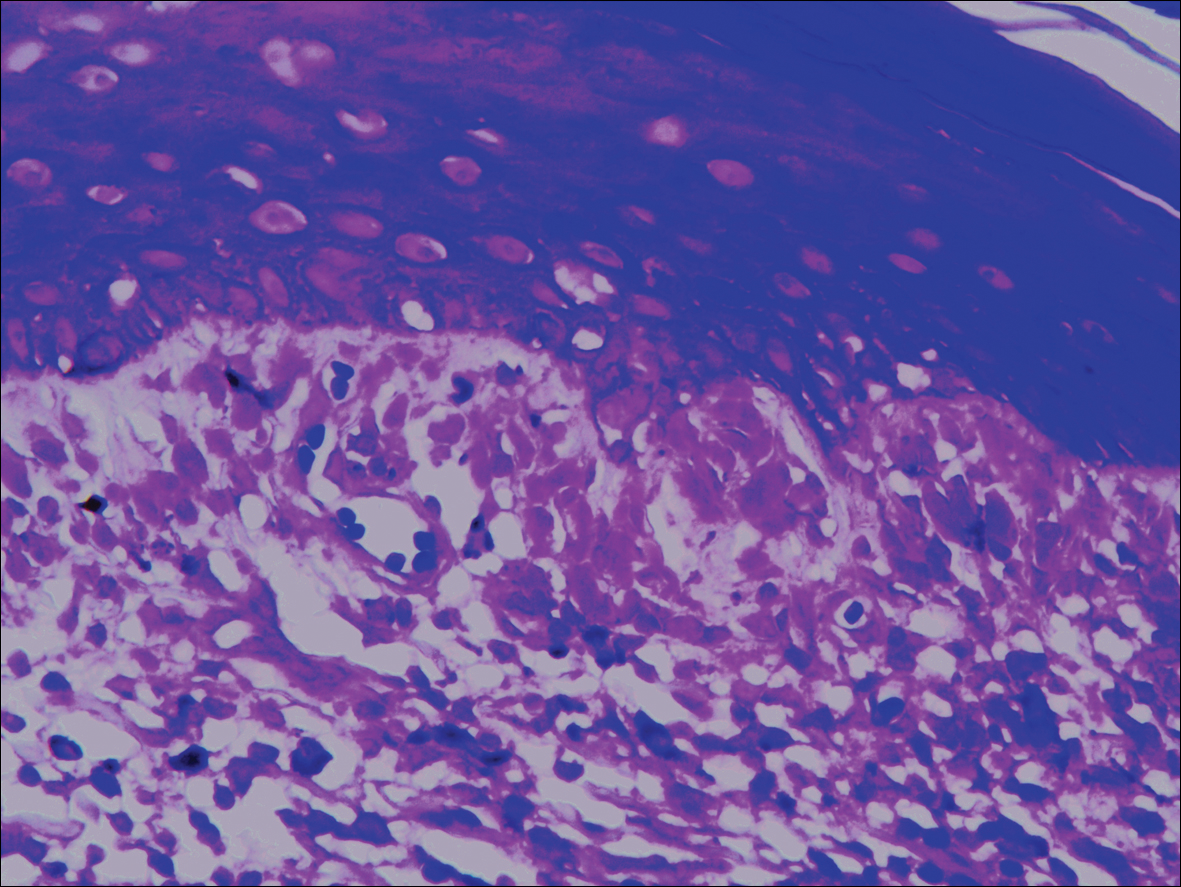

Physical examination revealed more than 50 scattered hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs ranging in size from 2 to 3.5 cm (Figure 1). Stroking of lesions failed to elicit Darier sign. A potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture were negative for pathogenic fungal organisms. The plasma insulin level was within reference range. A punch biopsy from the abdomen was obtained and sent for histopathologic examination. Histopathology showed mild hyperkeratosis, subtle papillomatosis, and interanastomosing acanthosis comprising squamoid cells with mild basilar hyperpigmentation (Figure 2). Sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased pigmentation was seen in the basal layer. The dermis showed a few scattered dermal melanophages. A periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative. Giemsa and Leder stains highlighted a normal number and distribution of mast cells. Based on the histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP).

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition that was described in 1978 by Degos et al.1 Sanz de Galdeano et al2 established the following diagnostic criteria: (1) eruption of brownish black, nonconfluent, asymptomatic macules involving the trunk, neck, and proximal arms and legs in children or adolescents; (2) absence of preceding inflammatory lesions; (3) no prior drug exposure; (4) basal cell layer hyperpigmentation of the epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages without visible basal layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate; and (5) normal mast cell count.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis (IEMPwP) is a variant of IEMP.3 It is undecided if IEMP and IEMPwP are variants of the same entity or distinct conditions. Until a clear etiology of these entities is established, we prefer to separate them on purely morphologic grounds. Marcoux et al4 labeled IEMPwP as a variant of acanthosis nigricans. Although morphologically the 2 conditions appear similar, our patient’s plasma insulin level essentially ruled out acanthosis nigricans.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition with the majority of cases reported in the Asian population with some reports in white, Hispanic, and black individuals.5 Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis was reported by Joshi3 in 2007 in 9 Indian children with the classic findings of IEMP along with a velvety rash that correlated with papillomatosis. Diagnosis of IEMPwP is important, as the disease generally is self-limited and resolves over the course of a few weeks to a few years.

- Degos R, Civatte J, Belaïch S. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (author’s transl)[in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1978;105:177-182.

- Sanz de Galdeano C, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of five patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:274-277.

- Joshi R. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis: report of nine cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:402-405.

- Marcoux DA, Durán-McKinster C, Baselga E. Pigmentary abnormalities. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:700-746.

- Torres-Romero LF, Lisle A, Waxman L. Asymptomatic hyperpigmented macules and patches on the trunk. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:546, 586.

To the Editor:

A 13-year-old white adolescent girl presented with asymptomatic discrete hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs of 7 months’ duration. The patient otherwise was in good health; her weight and height were on the 40th percentile on growth curves and she had no history of any medications. Treatments for the skin condition prescribed by outside dermatologists included minocycline 75 mg twice daily for 2 months, lactic acid lotion 12% daily, and ketoconazole 400 mg administered twice 1 week apart.

Physical examination revealed more than 50 scattered hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs ranging in size from 2 to 3.5 cm (Figure 1). Stroking of lesions failed to elicit Darier sign. A potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture were negative for pathogenic fungal organisms. The plasma insulin level was within reference range. A punch biopsy from the abdomen was obtained and sent for histopathologic examination. Histopathology showed mild hyperkeratosis, subtle papillomatosis, and interanastomosing acanthosis comprising squamoid cells with mild basilar hyperpigmentation (Figure 2). Sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased pigmentation was seen in the basal layer. The dermis showed a few scattered dermal melanophages. A periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative. Giemsa and Leder stains highlighted a normal number and distribution of mast cells. Based on the histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP).

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition that was described in 1978 by Degos et al.1 Sanz de Galdeano et al2 established the following diagnostic criteria: (1) eruption of brownish black, nonconfluent, asymptomatic macules involving the trunk, neck, and proximal arms and legs in children or adolescents; (2) absence of preceding inflammatory lesions; (3) no prior drug exposure; (4) basal cell layer hyperpigmentation of the epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages without visible basal layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate; and (5) normal mast cell count.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis (IEMPwP) is a variant of IEMP.3 It is undecided if IEMP and IEMPwP are variants of the same entity or distinct conditions. Until a clear etiology of these entities is established, we prefer to separate them on purely morphologic grounds. Marcoux et al4 labeled IEMPwP as a variant of acanthosis nigricans. Although morphologically the 2 conditions appear similar, our patient’s plasma insulin level essentially ruled out acanthosis nigricans.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition with the majority of cases reported in the Asian population with some reports in white, Hispanic, and black individuals.5 Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis was reported by Joshi3 in 2007 in 9 Indian children with the classic findings of IEMP along with a velvety rash that correlated with papillomatosis. Diagnosis of IEMPwP is important, as the disease generally is self-limited and resolves over the course of a few weeks to a few years.

To the Editor:

A 13-year-old white adolescent girl presented with asymptomatic discrete hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs of 7 months’ duration. The patient otherwise was in good health; her weight and height were on the 40th percentile on growth curves and she had no history of any medications. Treatments for the skin condition prescribed by outside dermatologists included minocycline 75 mg twice daily for 2 months, lactic acid lotion 12% daily, and ketoconazole 400 mg administered twice 1 week apart.

Physical examination revealed more than 50 scattered hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs ranging in size from 2 to 3.5 cm (Figure 1). Stroking of lesions failed to elicit Darier sign. A potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture were negative for pathogenic fungal organisms. The plasma insulin level was within reference range. A punch biopsy from the abdomen was obtained and sent for histopathologic examination. Histopathology showed mild hyperkeratosis, subtle papillomatosis, and interanastomosing acanthosis comprising squamoid cells with mild basilar hyperpigmentation (Figure 2). Sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased pigmentation was seen in the basal layer. The dermis showed a few scattered dermal melanophages. A periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative. Giemsa and Leder stains highlighted a normal number and distribution of mast cells. Based on the histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP).

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition that was described in 1978 by Degos et al.1 Sanz de Galdeano et al2 established the following diagnostic criteria: (1) eruption of brownish black, nonconfluent, asymptomatic macules involving the trunk, neck, and proximal arms and legs in children or adolescents; (2) absence of preceding inflammatory lesions; (3) no prior drug exposure; (4) basal cell layer hyperpigmentation of the epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages without visible basal layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate; and (5) normal mast cell count.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis (IEMPwP) is a variant of IEMP.3 It is undecided if IEMP and IEMPwP are variants of the same entity or distinct conditions. Until a clear etiology of these entities is established, we prefer to separate them on purely morphologic grounds. Marcoux et al4 labeled IEMPwP as a variant of acanthosis nigricans. Although morphologically the 2 conditions appear similar, our patient’s plasma insulin level essentially ruled out acanthosis nigricans.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation is a rare condition with the majority of cases reported in the Asian population with some reports in white, Hispanic, and black individuals.5 Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis was reported by Joshi3 in 2007 in 9 Indian children with the classic findings of IEMP along with a velvety rash that correlated with papillomatosis. Diagnosis of IEMPwP is important, as the disease generally is self-limited and resolves over the course of a few weeks to a few years.

- Degos R, Civatte J, Belaïch S. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (author’s transl)[in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1978;105:177-182.

- Sanz de Galdeano C, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of five patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:274-277.

- Joshi R. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis: report of nine cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:402-405.

- Marcoux DA, Durán-McKinster C, Baselga E. Pigmentary abnormalities. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:700-746.

- Torres-Romero LF, Lisle A, Waxman L. Asymptomatic hyperpigmented macules and patches on the trunk. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:546, 586.

- Degos R, Civatte J, Belaïch S. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (author’s transl)[in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1978;105:177-182.

- Sanz de Galdeano C, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation: report of five patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:274-277.

- Joshi R. Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis: report of nine cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:402-405.

- Marcoux DA, Durán-McKinster C, Baselga E. Pigmentary abnormalities. In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:700-746.

- Torres-Romero LF, Lisle A, Waxman L. Asymptomatic hyperpigmented macules and patches on the trunk. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:546, 586.

Practice Points

- Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis is a rare disorder that most frequently affects children and young adults.

- Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation with papillomatosis is characterized by asymptomatic, brownish, hyperpigmented macules involving the neck, trunk, arms, and legs.

- The disorder is important to consider in the differential diagnosis of asymptomatic pigmentary disorders to avoid unnecessary treatment because the disease is self-limiting and resolves over weeks to years.

Sweet Syndrome With Aseptic Splenic Abscesses and Multiple Myeloma

To the Editor:

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with 5 erythematous cutaneous nodules of several days’ duration on the legs ranging in size from 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Upon admission, the patient also had a chest radiograph suspicious for pneumonia. The patient had received sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection as an outpatient 5 days prior to presentation, but he stopped the medication due to the appearance of the cutaneous nodules. Of note, the patient also reported unintentional weight loss of 15 pounds over the last few months.

New nodules had developed at a rate of 1 to 2 lesions daily in the 3 days prior to presentation and continued to develop after admission to the hospital. The nodules appeared as tender, erythematous lesions that evolved to form pustules and developed overlying crusts in later stages (Figure 1). They were limited to the arms and legs, primarily involving the lower legs. There was no evidence of oral or ocular involvement. A hemoglobin count of 10.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), white blood cell count of 8.8×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 69 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) were noted on admission.

The patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for suspected pneumonia. The differential diagnosis for the cutaneous nodules included lymphoma, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) infection, deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome (SS), panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, and polyarteritis nodosa. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the left foot was performed. Histopathology demonstrated a neutrophilic panniculitis (Figure 2) with an epidermal abscess. No vasculitis was identified, and periodic acid–Schiff and AFB staining of the skin biopsy were negative. These findings were consistent with SS. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were completed early in the course of hospitalization due to concern for underlying malignancy, revealed pericardial and pleural effusions as well as cystic lesions in the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and prostate, with the largest lesion on the spleen measuring 5.6×4.8 cm (Figure 3). Computed tomography scanning was negative for areas of consolidation in the lungs. A splenic biopsy was performed by an interventional radiologist during the patient's hospitalization that identified an aseptic, neutrophilic process. Fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures of the splenic tissue and cystic contents were negative. Bilateral pleural effusions also were identified, and a thoracentesis was performed. The pleural fluid indicated rare mesothelial cells in the background of acute inflammation with no growth of the bacterial, fungal, or AFB cultures.

Due to the association of hematologic malignances with SS, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, which revealed multiple myeloma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated monoclonal gammopathy of κ light chains. During the course of his hospitalization, new skin lesions continued to develop on the hands, face, and trunk. The patient was discharged from the hospital shortly after diagnosis to receive outpatient treatment for multiple myeloma with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Upon follow-up with the patient’s family via telephone 3 weeks into treatment, his son confirmed that the nodules were resolving.

Our case could be consistent with either drug-induced or malignancy-associated SS. Sweet syndrome initially was described in 1964 in 8 female patients with leukocytosis and cutaneous plaques infiltrated by neutrophils.1 The skin lesions typically are red and painful, ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 12.0 cm, and can last weeks to years if not treated.2 Variations of skin lesions include bullous and pustular morphologies.3