User login

Purpuric Macule of the Right Axilla

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

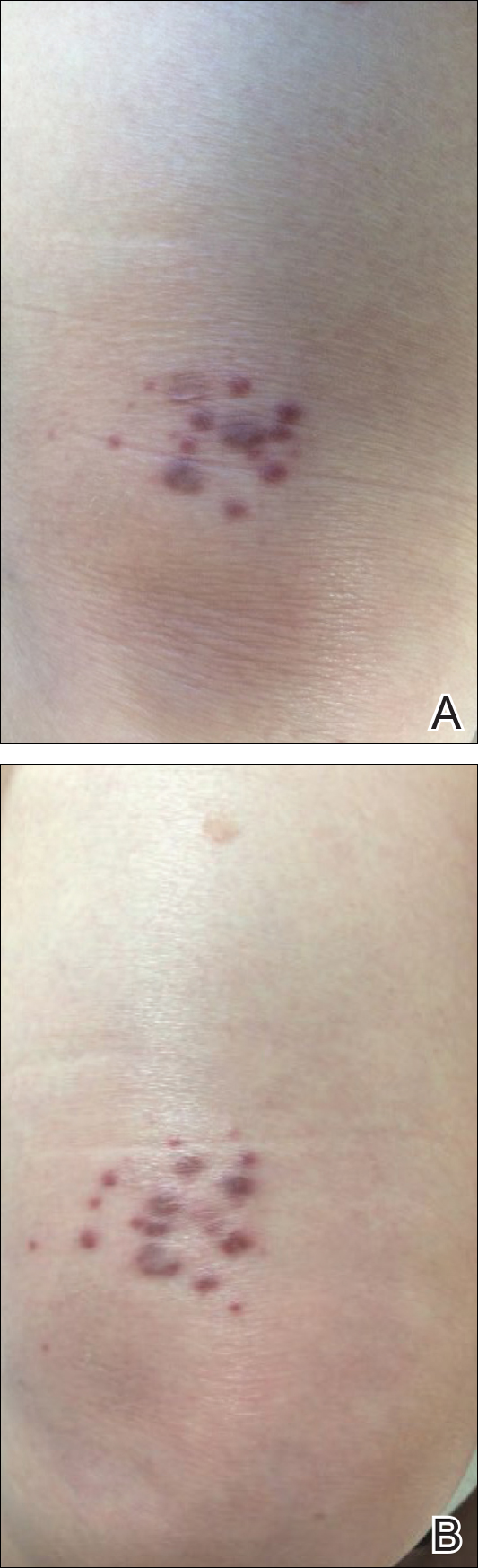

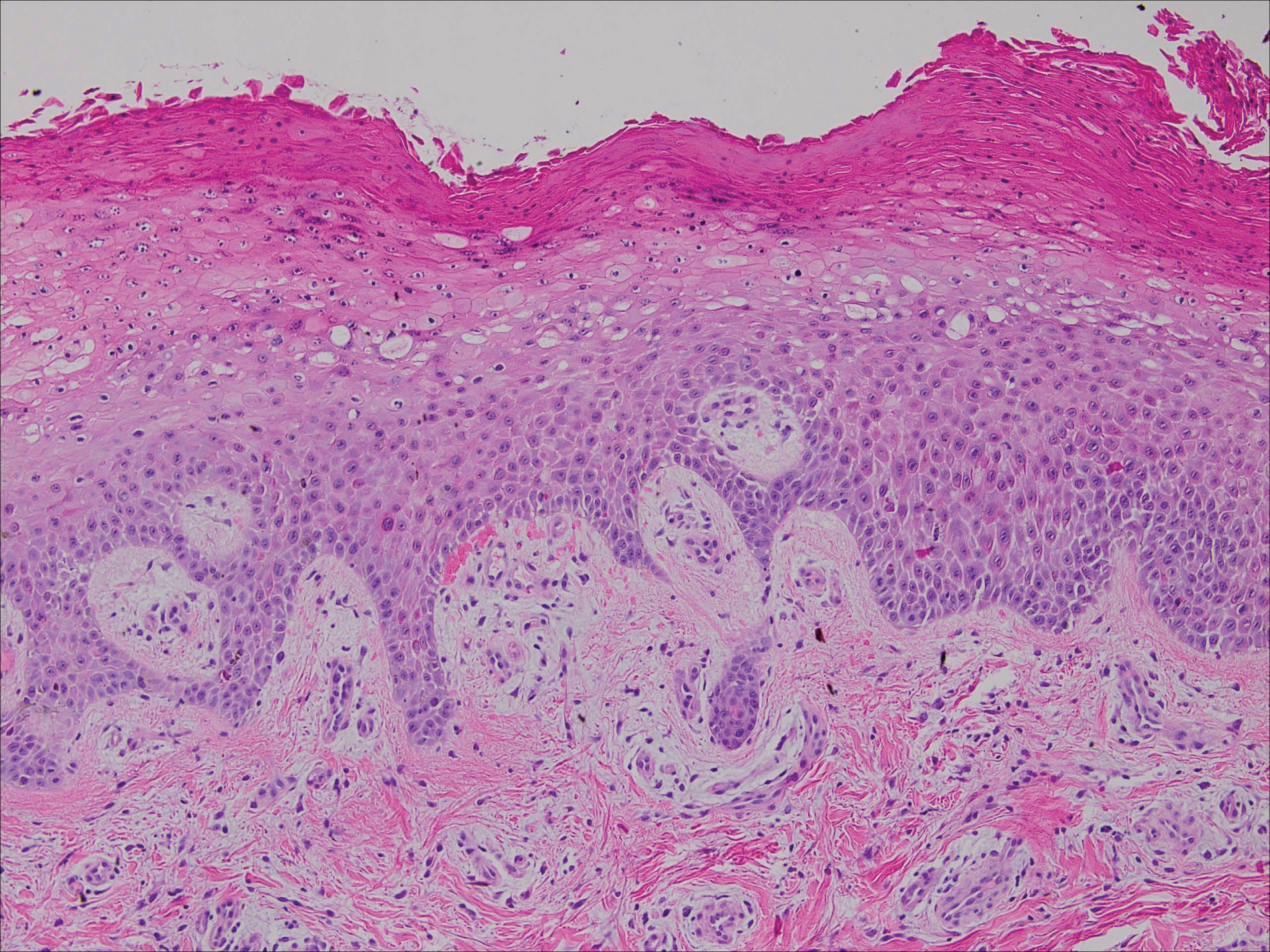

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

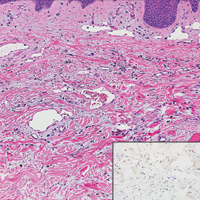

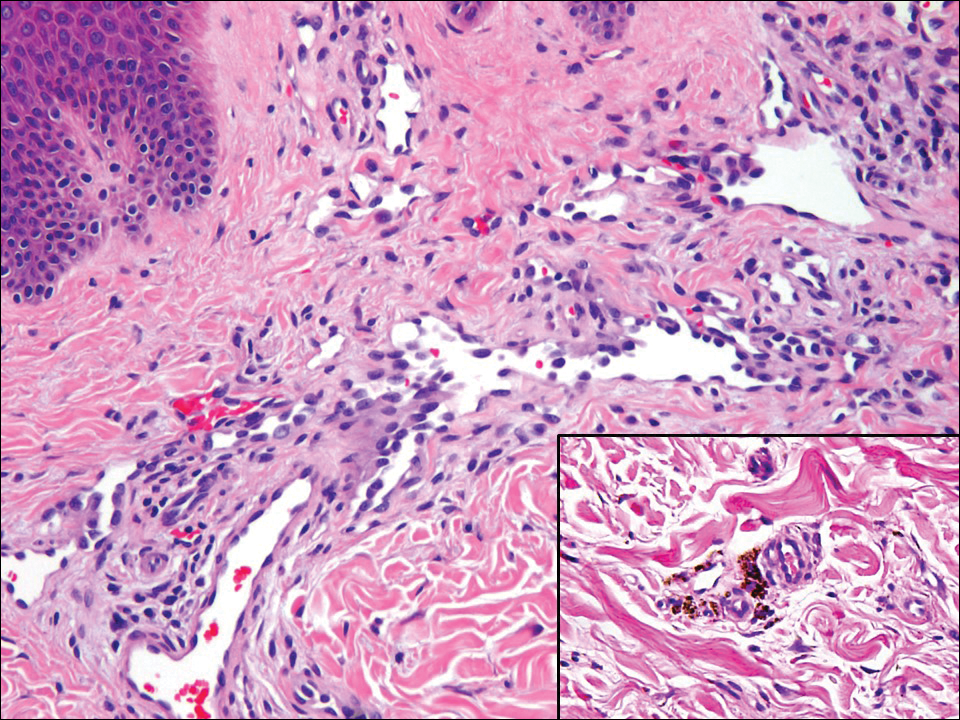

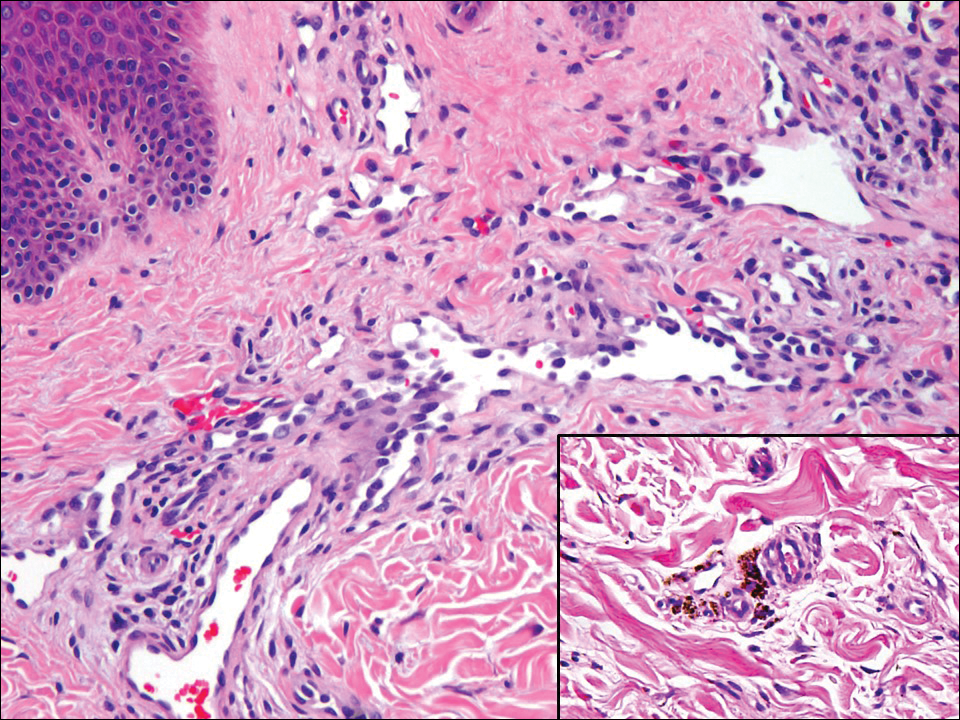

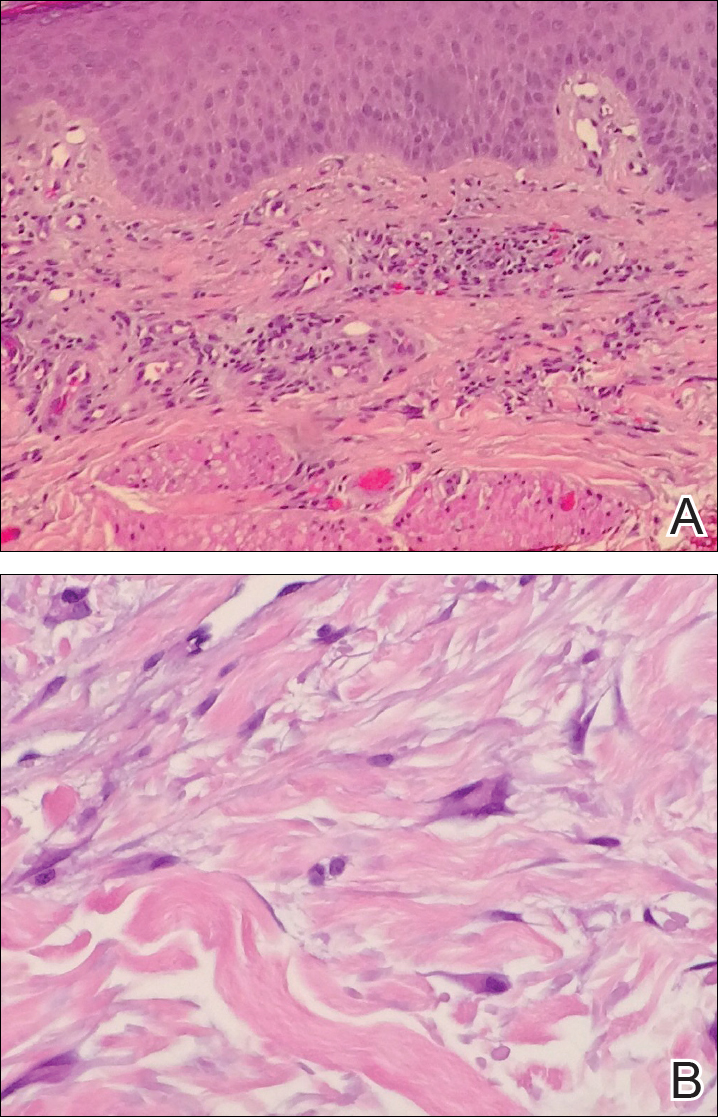

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

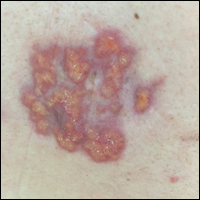

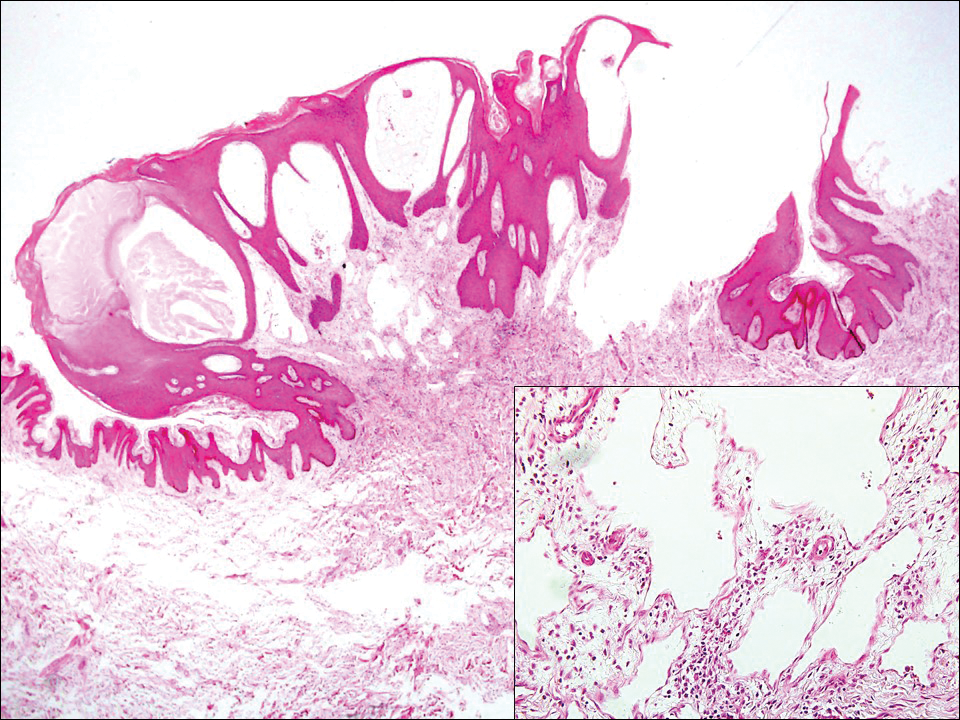

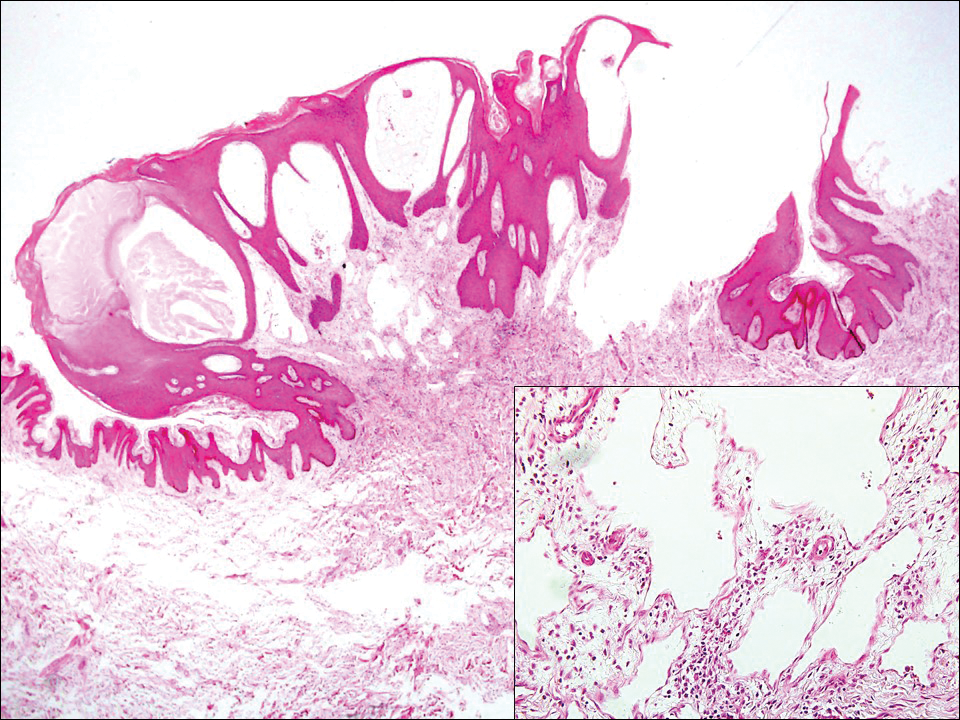

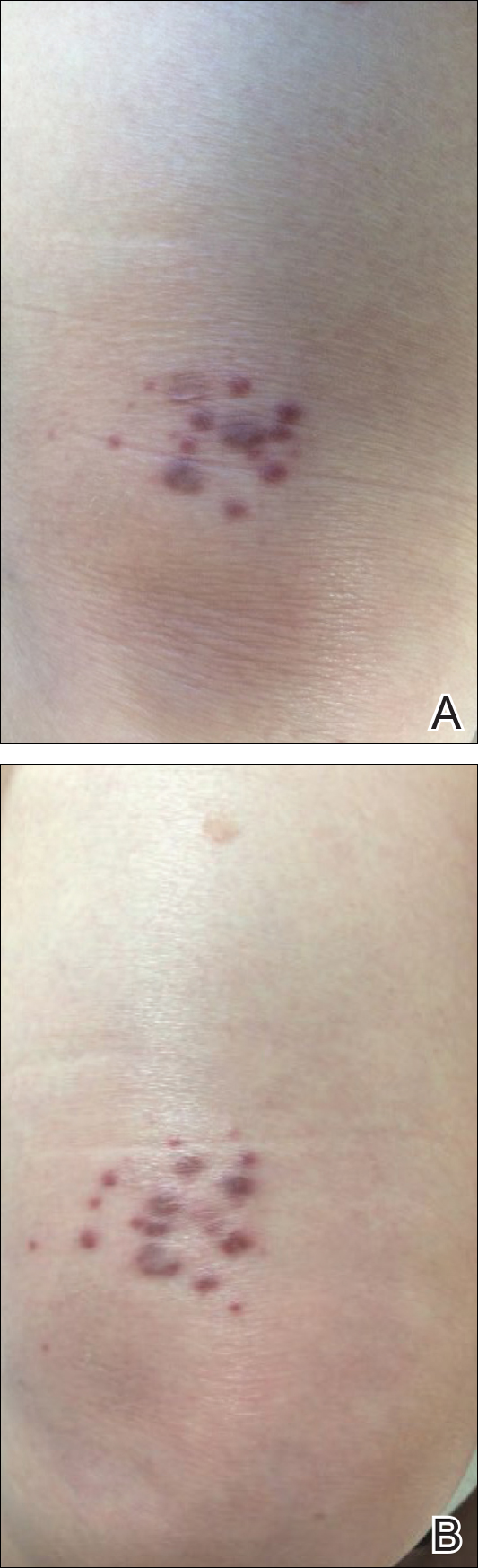

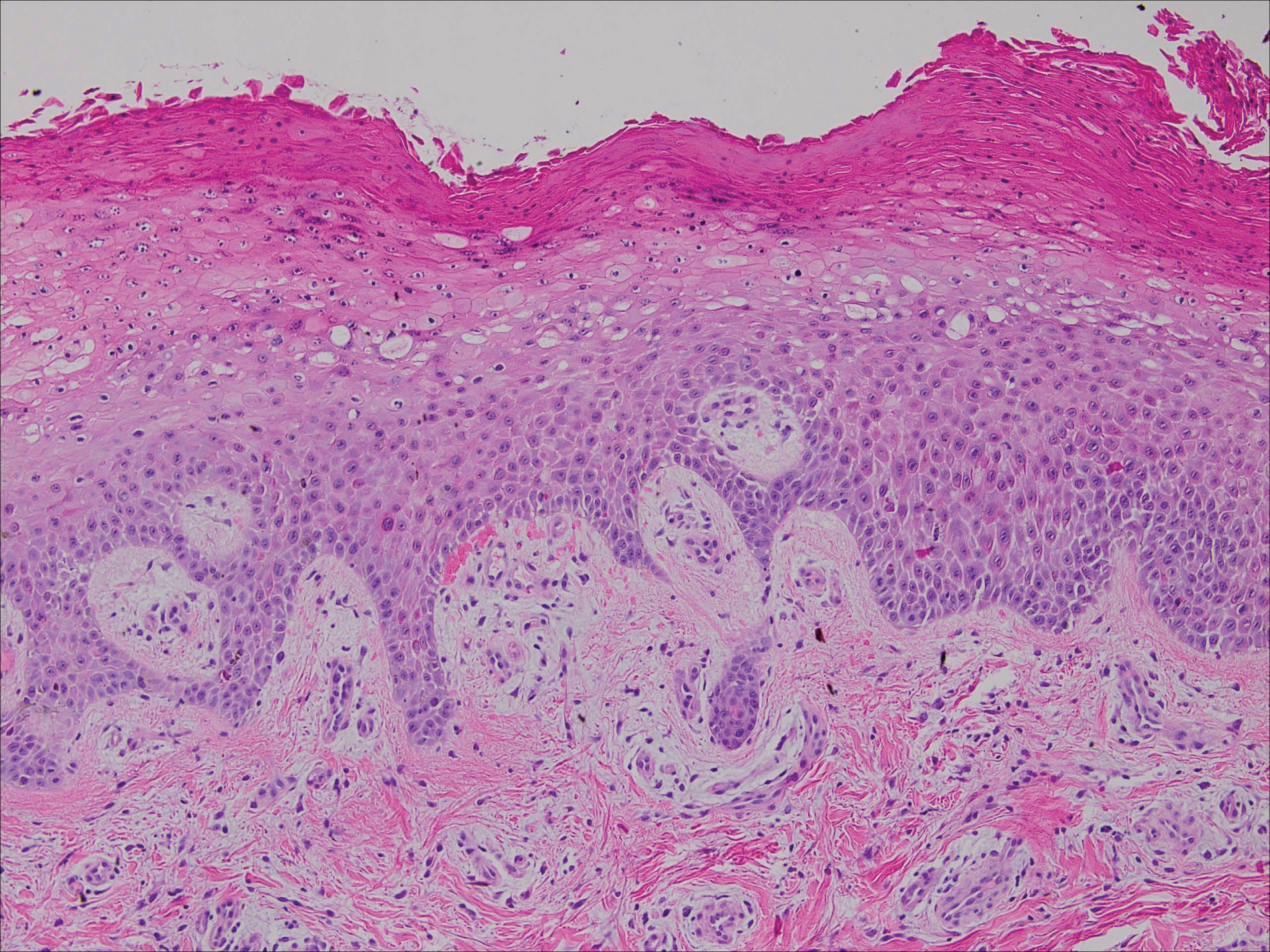

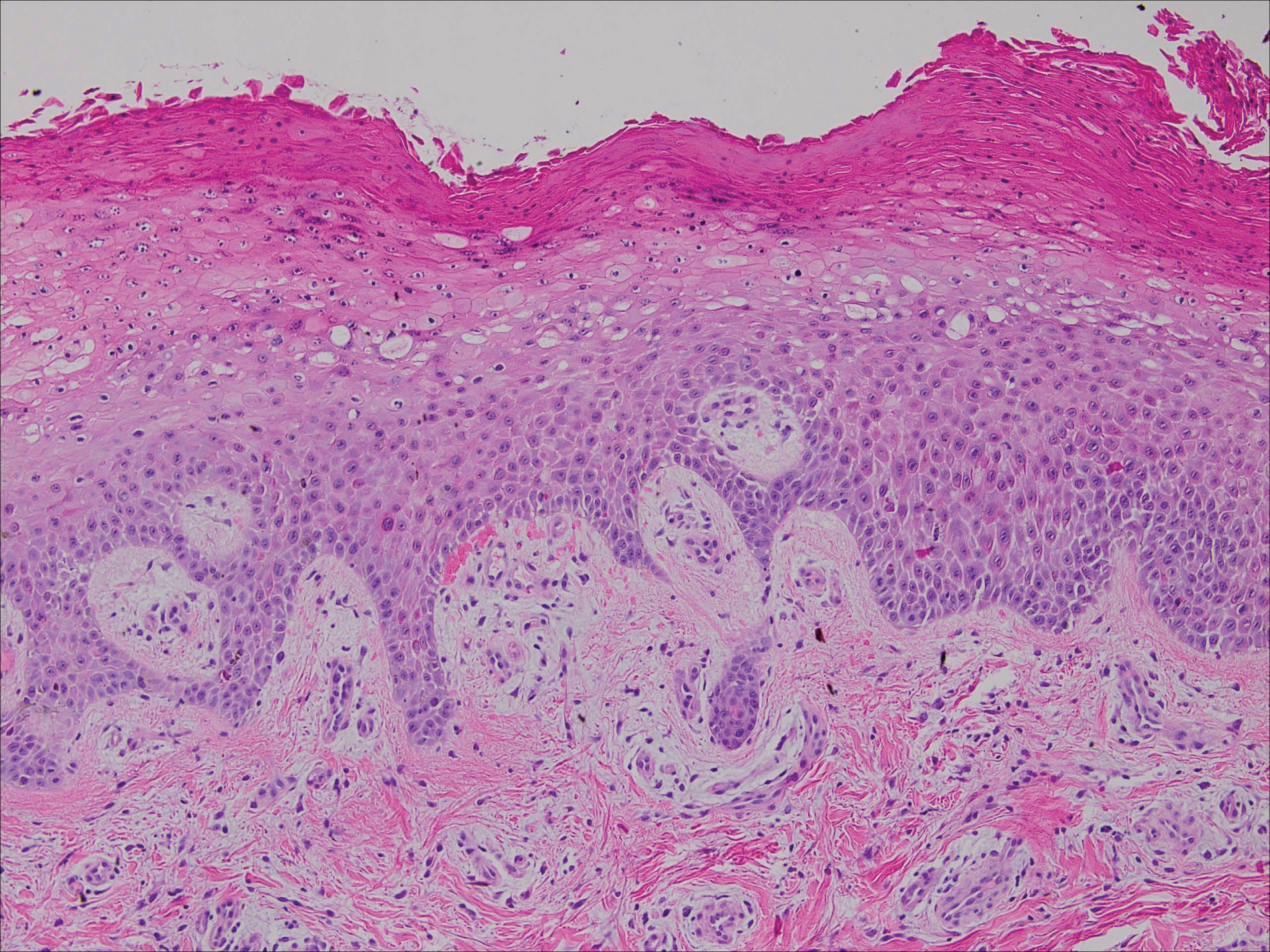

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

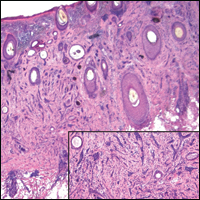

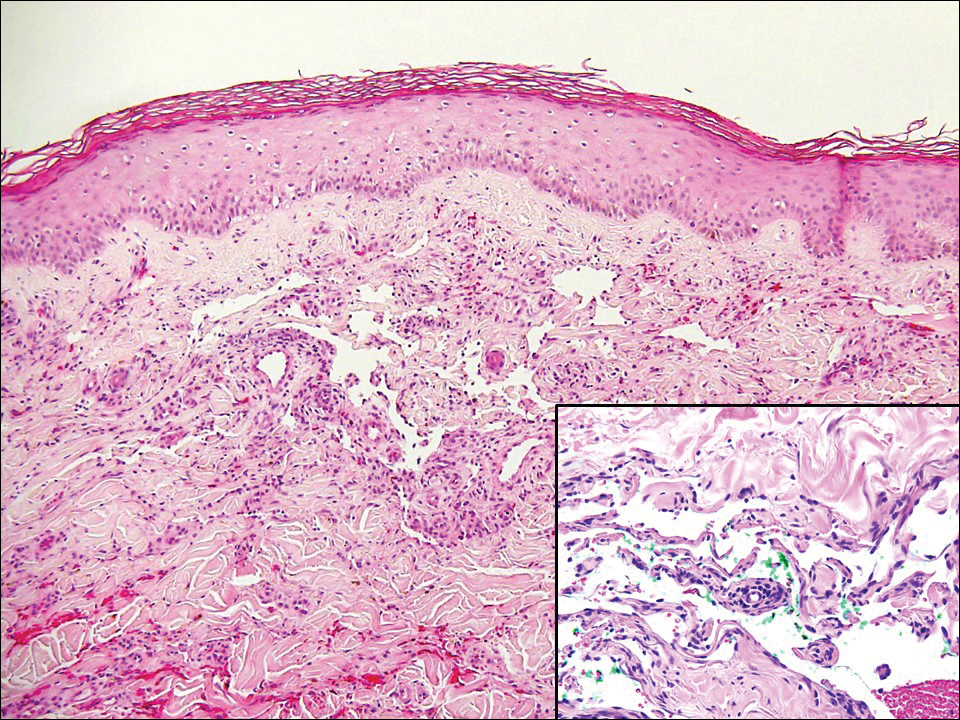

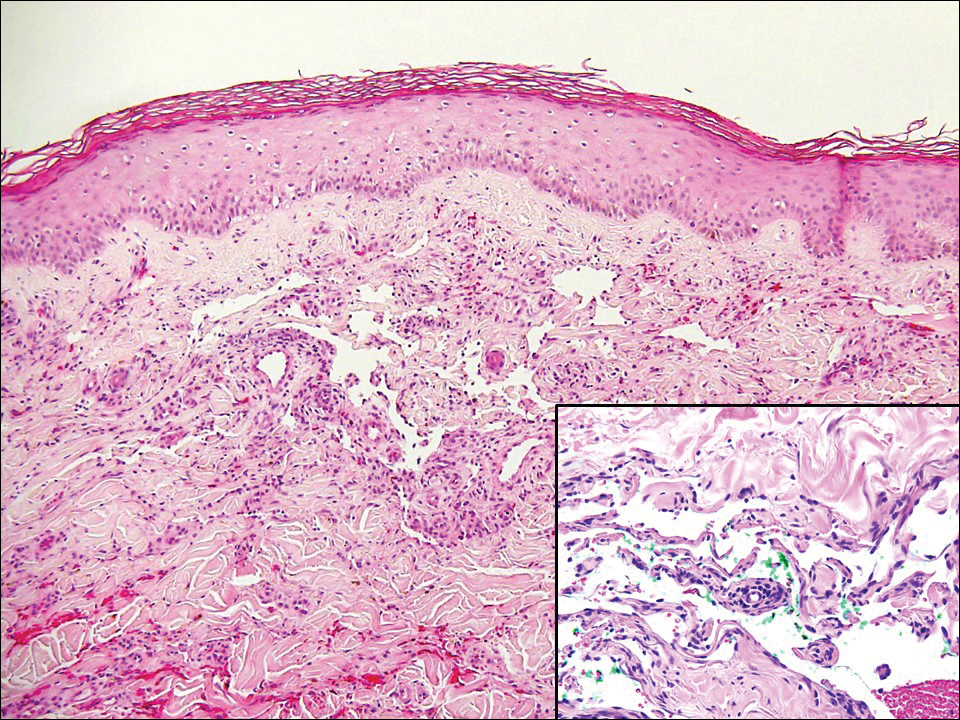

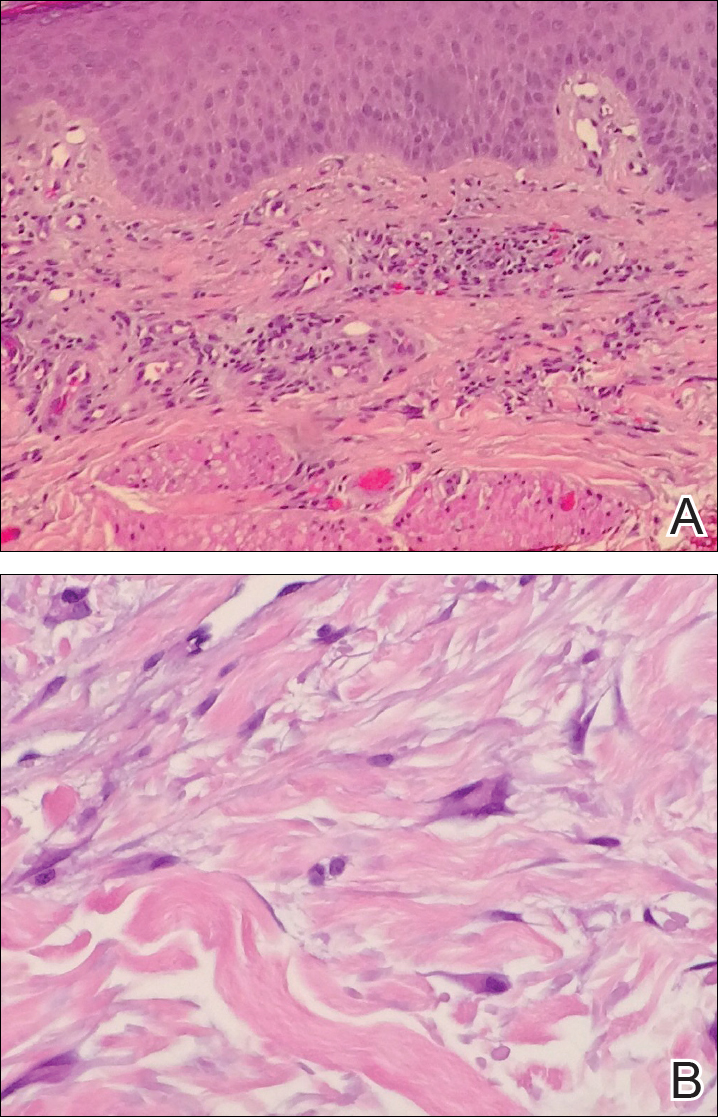

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

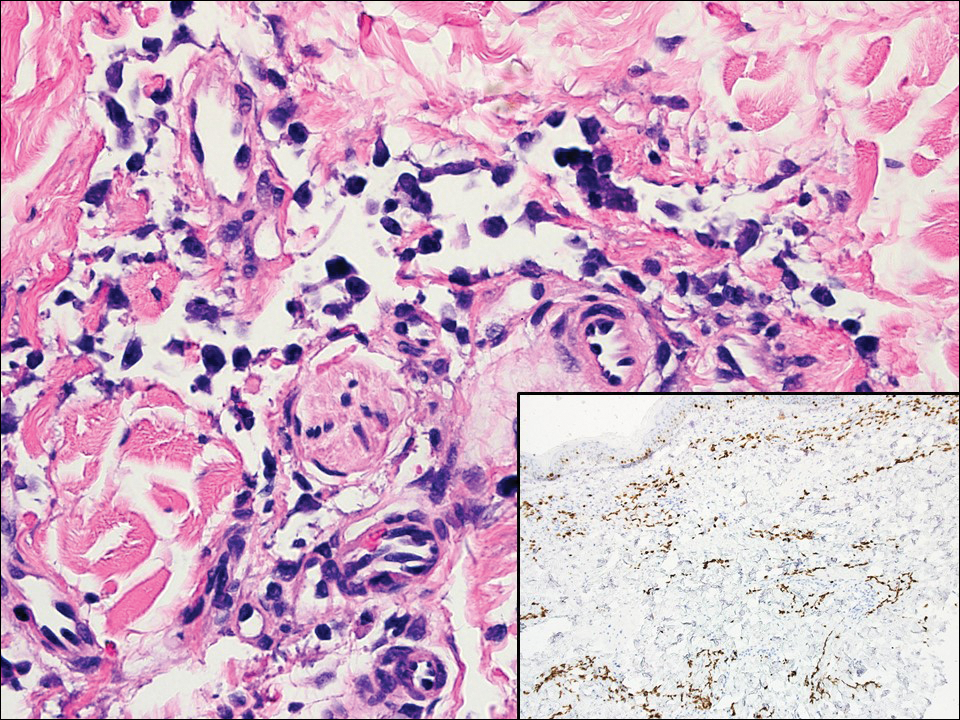

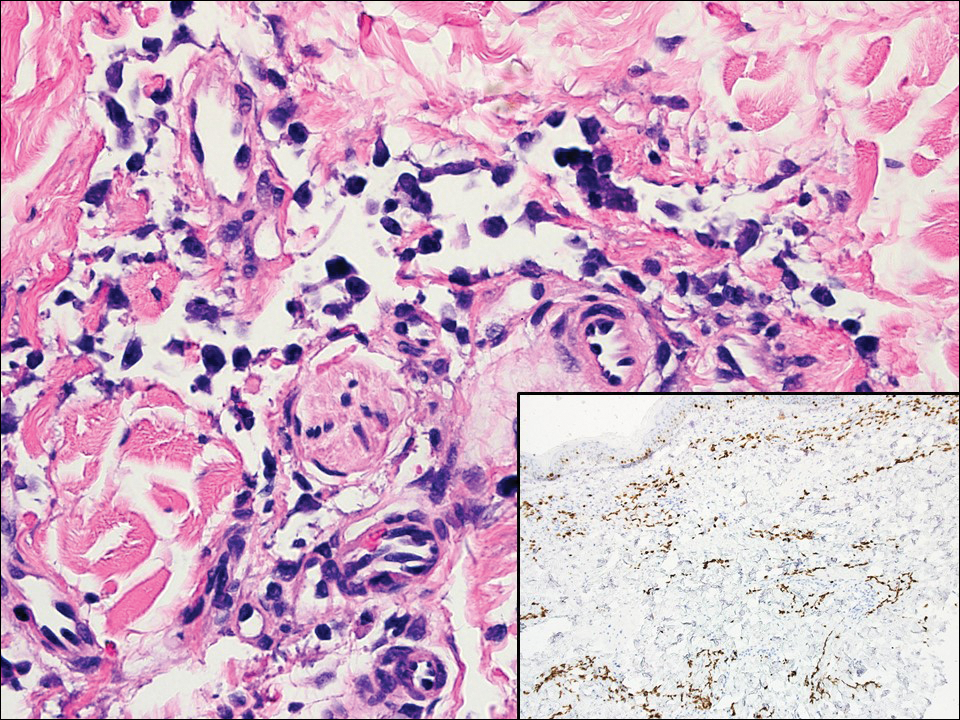

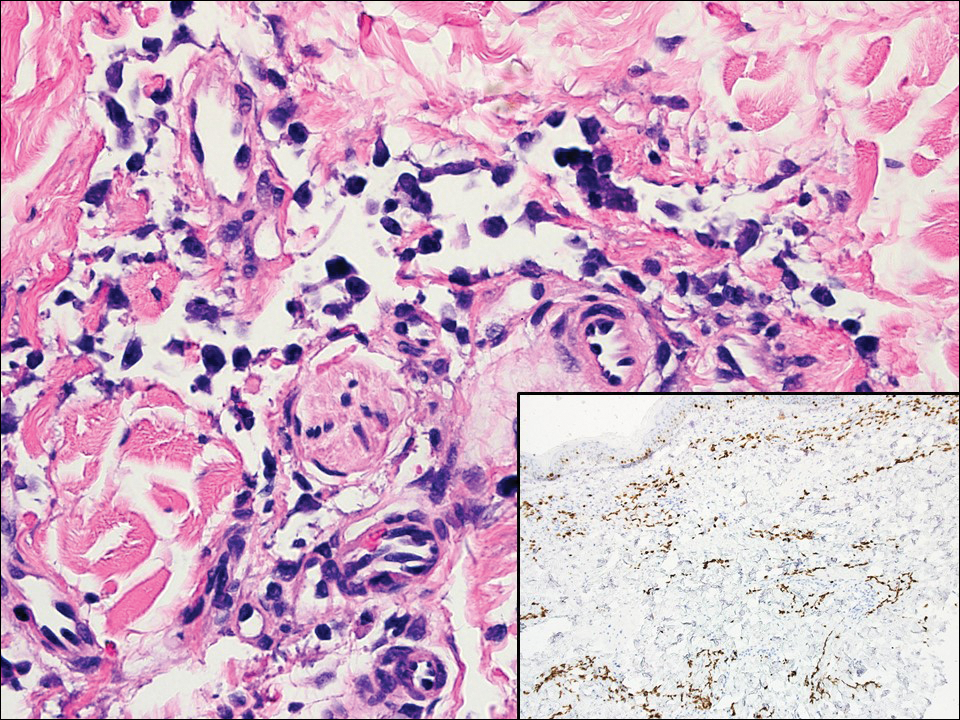

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

The Diagnosis: Atypical Vascular Lesion

Atypical vascular lesion (AVL)(quiz image), named by Fineberg and Rosen,1 is a vascular lesion that arises on mammary skin with a history of radiation exposure. Clinically, AVL can present as a papule or erythematous patch that manifests 3 to 7 years after radiation therapy.2,3 There are 2 histologic subtypes of AVL: lymphatic and vascular.2,4 Lymphatic-type AVL is comprised of a symmetric distribution of thin, dilated, and anastomosing vessels usually found in the superficial and mid dermis. The vessels are lined by flat or hobnail protuberant endothelial cells that lack nuclear irregularity or pleomorphism; however, hyperchromatism of endothelial cell nuclei is a common finding. Vascular-type AVL is morphologically similar to a capillary hemangioma, and histologic features include irregular growth of capillary-sized vessels that extend to the dermis and subcutis.2,4 Atypical vascular lesions are benign lesions but may be a precursor to angiosarcoma. Along with vascular markers, D2-40 typically is positive. Surgical excision with clear margins is recommended when the lesion is small.4,5 Observation is more appropriate for extensive lesions.

Angiosarcoma can arise spontaneously or in association with radiation or chronic lymphedema. Given the shared risk factors and presentation with AVL, it is essential to differentiate angiosarcoma from AVL. Primary cutaneous angiosarcoma usually presents on the head of elderly patients as an ecchymotic patch or plaque with ulceration.4 Secondary angiosarcoma may arise following radiation or chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, some authors now prefer to consider lymphangiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedematous limbs a distinct entity.6 Surgical excision with wide margins is the mainstay of therapy, but angiosarcoma has high recurrence rates, and the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be as low as 35%.7 Histologic overlap with AVL includes dissecting anastomosing vessels lined by hyperchromatic nuclei; however, angiosarcoma is distinguished by endothelial cell layering, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1).4,8 Increased positivity for Ki-67 immunostain, which indicates cell proliferation, may be used to distinguish angiosarcoma from an AVL (Figure 1 [inset]).9 Further, in contrast to AVL, radiation-induced angiosarcoma is characterized by amplification of C-MYC, a regulator gene, and FLT4 (FMS-related tyrosine kinase 4), a gene encoding vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3. Gene amplification may be detected through immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization.10 Ki-67 labeling showed less than 10% staining in endothelial cells in our case (quiz image [inset]), and fluorescence in situ hybridization was negative for C-MYC amplification, supporting the diagnosis of AVL.

Lymphangioma circumscriptum, the most common superficial lymphangioma, is a hamartomatous malformation that usually occurs at the axillary folds, neck, and trunk. It clinically presents as small agminated vesicles with a characteristic frog spawn appearance.11 Dermoscopic features include yellow lacunae that may alternate with a dark red color secondary to extravasation of erythrocytes.12 These clinical features often lead to a differential diagnosis of verrucae, angiokeratoma, and angiosarcoma. Lymphangioma circumscriptum histologically is characterized by an overgrowth of dilated lymphatic vessels that fill the papillary dermis. The vessels are composed of flat endothelial cells typically filled with acellular proteinaceous debris and occasional erythrocytes (Figure 2). As the lesion traverses deeper into the dermis, the caliber of the lymphatic channel becomes narrower. The presence of deep lymphatic cisterns with surrounding smooth muscle is helpful to differentiate lymphangioma circumscriptum from other lymphatic malformations such as acquired lymphangiectasia. Treatment options include surgical excision, sclerosing agents, and destructive modalities such as cryotherapy.

Hobnail hemangioma, originally termed targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma by Santa Cruz and Aronberg,13 presents as a violaceous papule or nodule surrounded by a characteristic brown halo on the leg. Trauma has been proposed as the inciting factor for the clinical appearance of hobnail hemangioma.14 Microscopically, the lesion shows vessels in a wedge shape. The superficial component has telangiectatic vessels with focal areas of papillary projections lined by endothelial cells. Although the endothelial nuclei typically project into the lumen, the nuclei are small, bland, and without mitotic activity.15 Deeper components show slit-shaped vasculature with dermal collagen dissection. Hemosiderin, extravasated red blood cells, and inflammation are found adjacent to the vessels (Figure 3). Given the benign nature, hobnail hemangiomas may be monitored.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8 that arises in multiple clinical settings, especially in immunosuppression secondary to human immunodeficiency virus. There are 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and tumor. The patch stage appears as red macules that blend into larger plaques; the tumor stage is defined as larger nodules developing from plaques. Histologic features differ by stage. Similar to angiosarcoma, KS is comprised of anastomosing vessels that dissect collagen bundles; endothelial cell atypia is minimal. A useful feature of KS is its propensity to involve adnexa and display the promontory sign, which involves the tumor growing into normal vasculature (Figure 4).16 Positive immunohistochemistry for human herpesvirus 8 aids in confirmation of the diagnosis. Treatment options for KS are numerous but include destructive modalities, chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin, or highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-related KS.17

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

- Fineberg S, Rosen PP. Cutaneous angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions of the skin and breast after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:757-763.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:781-788.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Udager AM, Ishikawa MK, Lucas DR, et al. MYC immunohistochemistry in angiosarcoma and atypical vascular lesions: practical considerations based on a single institutional experience. Pathology. 2016;48:697-704.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fraga-Guedes C, Gobbi H, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases of post-radiation atypical vascular lesion of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:347-354.

- Shin SJ, Lesser M, Rosen PP. Hemangiomas and angiosarcomas of the breast: diagnostic utility of cell cycle markers with emphasis on Ki-67. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:538-544.

- Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, et al. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatment of postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:868-875.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295.

- Massa AF, Menezes N, Baptista A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum--dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:262-264.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Aronberg J. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:550-558.

- Christenson LJ, Stone MS. Trauma-induced simulator of targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:221-223.

- Trindade F, Kutzner H, Tellechea O, et al. Hobnail hemangioma reclassified as superficial lymphatic malformation: a study of 52 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:112-115.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Di Lorenzo G, Di Trolio R, Montesarchio V, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as second-line therapy in the treatment of patients with advanced classic Kaposi sarcoma: a retrospective study. Cancer. 2008;112:1147-1152.

A 67-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the medial aspect of the right axilla of 2 weeks' duration. The patient had a history of cancer of the right breast treated with a mastectomy and adjuvant radiation. She denied pain, bleeding, pruritus, or rapid growth, as well as any changes in medication or recent trauma. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm purpuric macule of the right axilla. A punch biopsy was performed. Amplification for the C-MYC gene was negative by fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Irregular Yellow-Brown Plaques on the Trunk and Thighs

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

The Diagnosis: Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed for routine stain with hematoxylin and eosin. The differential diagnosis included sarcoidosis, necrobiosis lipoidica, xanthoma disseminatum, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure). There were surrounding areas of degenerated collagen containing numerous cholesterol clefts. After clinical pathologic correlation, a diagnosis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) was elucidated.

The patient was referred to general surgery for elective excision of 1 or more of the lesions. Excision of an abdominal lesion was performed without complication. After several months, a new lesion reformed within the excisional scar that also was consistent with NXG. At further dermatologic visits, a trial of intralesional corticosteroids was attempted to the largest lesions with modest improvement. In addition, follow-up with hematology and oncology was recommended for routine surveillance of the known blood dyscrasia.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a multisystem non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disease. Clinically, NXG is characterized by infiltrative plaques and ulcerative nodules. Lesions may appear red, brown, or yellow with associated atrophy and telangiectasia.1 Koch et al2 described a predilection for granuloma formation within preexisting scars. Periorbital location is the most common cutaneous site of involvement of NXG, seen in 80% of cases, but the trunk and extremities also may be involved.1,3 Approximately half of those with periocular involvement experience ocular symptoms including prop- tosis, blepharoptosis, and restricted eye movements.4 The onset of NXG most commonly is seen in middle age.

Characteristic systemic associations have been reported in the setting of NXG. More than 20% of patients may exhibit hepatomegaly. Hematologic abnormalities, hyperlipidemia, and cryoglobulinemia also may be seen.1 In addition, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance is found in more than 80% of NXG cases. The IgG κ light chain is most commonly identified.2 A foreign body reaction is incited by the immunoglobulin-lipid complex, which is thought to contribute to the formation of cutaneous lesions. There may be associated plasma cell dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma or B-cell lymphoma in approximately 13% of cases.2 Evaluation for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoproliferative disorder should be performed regularly with serum protein electrophoresis or immunofixation electrophoresis, and in some cases full-body imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted.1

Treatment of NXG often is unsuccessful. Surgical excision, systemic immunosuppressive agents, electron beam radiation, and destructive therapies such as cryotherapy may be trialed, often with little success.1 Cutaneous regression has been reported with combination treatment of high-dose dexamethasone and high-dose lenalidomide.5

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

- Efebera Y, Blanchard E, Allam C, et al. Complete response to thalidomide and dexamethasone in a patient with necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11:298-302.

- Koch PS, Goerdt S, Géraud C. Erythematous papules, plaques, and nodular lesions on the trunk and within preexisting scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1103-1104.

- Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: a review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:457-463.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Dholaria BR, Cappel M, Roy V. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with monoclonal gammopathy: successful treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone [published online Jan 27, 2016]. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:671-672.

A 40-year-old man presented with tender lesions on the back, abdomen, and thighs of 10 years' duration. His medical history was remarkable for follicular lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance diagnosed 5 years after the onset of skin symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous irregularly shaped, yellow plaques on the back, abdomen, and thighs with overlying telangiectasia. A single lesion was noted to extend from a scar.

Pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.